« The Civil Rights Movement in the United States » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 87 : | Ligne 87 : | ||

== The Cold War and decolonisation == | == The Cold War and decolonisation == | ||

The civil rights movement in the United States took place at a time of significant global upheaval, including decolonisation and independence movements in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. The contradictions between American democratic ideals and racial segregation were increasingly scrutinised by a rapidly changing international community. The period was marked by a global call for greater equality and national sovereignty, and the United States' commitment to freedom and democracy was judged by its treatment of racial minorities on its own soil. In the context of the Cold War, US efforts to spread its influence and ideology were often contrasted with domestic social realities. Images of violence against civil rights demonstrators and gross inequality travelled around the world, casting doubt on the sincerity of American claims to be the leader of the free world. As a result, the civil rights struggle in the United States became an integral part of the global political scene, symbolising the fight for equality and justice around the world. The influence of the civil rights movement extended far beyond American borders, inspiring and energising other social movements across the globe. As the colonies won their independence, African-Americans fought for their civil rights, creating a synergy for global change. The legislative and social advances made in the United States, such as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, became emblematic examples of the progress possible towards a more inclusive and equitable society, resonating with the aspirations of those under the yoke of oppressive systems around the world. | |||

Gunnar Myrdal's An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy marked a turning point in the understanding and recognition of the deep racial dissonance within American society. Published in 1944, this text offered an exhaustive analysis of racial discrimination and segregation as phenomena contrary to the fundamental principles of American democracy. It highlighted the way in which the marginalisation of African-Americans hindered the country's quest for true liberal democracy. Myrdal's book came at a crucial time, during the Second World War, when the United States was engaged in a struggle against the forces of oppression and totalitarianism, while at the same time having to confront its own internal contradictions when it came to human rights. This work challenged intellectuals, legislators and the general public, prompting many to re-examine and question the persistence of racial inequality and segregation in a nation that held itself up as a model of freedom and democracy. The resonance of "An American Dilemma" in the United States and abroad helped build a moral and political consensus for change. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, which developed in response to this climate of heightened awareness, saw the emergence of leading figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and organisations like the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Their relentless struggle, often at the risk of their lives, led to major legislative advances, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which dismantled legal segregation and extended equal civil rights. It was against this backdrop that activism flourished, not only as a political and social movement, but also as a powerful force for cultural transformation, ushering in a new era of recognition and inclusion for African-Americans and serving as an example to civil rights movements around the world.[[File:Nimitz and miller.jpg|thumb|right|150px|Admiral Chester W. Nimitz pins Navy Cross on Doris Miller, at ceremony on board warship in Pearl Harbor, 27 May 1942.]] | |||

The Soldier Voting Act of 1942 was an important milestone in the evolution of civil rights in the United States, mainly because it recognised the injustice of denying soldiers, who risked their lives to defend democratic ideals abroad, the right to vote at home. This was all the more significant for African-American soldiers who were fighting for freedom abroad while facing segregation and discrimination at home. Indeed, the propaganda of the Axis powers highlighted the internal contradictions of American society with regard to race and democracy, and the introduction of the Soldier Voting Act was a step towards alleviating these contradictions. However, although the Act made it easier for soldiers serving overseas to vote, it did not remove the barriers to voting that existed for African-Americans in the United States, particularly in the South, where segregation and discrimination were institutionalised. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s built on these foundations, continuing the fight for equal rights for all citizens. Activists organised boycotts, sit-ins, marches and campaigns of civil disobedience to draw national and international attention to racial injustice. Under pressure from these actions and the geopolitical context of the Cold War, which required the United States to reinforce its image as a defender of freedom and democracy, significant legislative changes were made. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 are two of the most significant achievements of this era. The Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex or national origin, and ended segregation in schools, workplaces and public facilities. The Voting Rights Act eliminated voter testing and poll taxes that were used to prevent African Americans from voting, guaranteeing federal protection for minority voting rights. These laws marked a decisive turning point in guaranteeing the rights and freedoms of African-Americans, legally dismantling structures of segregation and paving the way for a more inclusive and egalitarian society.r freedom and democracy, and many hoped that the sacrifices they had made would be recognised by the granting of equal civil rights and freedoms at home. The reality, however, was very different. Despite the existence of legislation such as the Soldier Voting Act, which in theory was supposed to give soldiers the right to vote in elections, the reality was very different. | |||

The end of the Second World War marked a crucial moment for the civil rights movement in the United States. African-American soldiers were returning from a war in which they had fought to protect the soldiers' right to vote, but African-Americans still faced heavy barriers when they tried to register to vote, particularly in the Southern states. Tactics used to deter them included literacy tests and poll taxes, which were legal methods, but also threats, violence and even murder, which were illegal and brutal means. White supremacist violence was a terrifying and pervasive tool to maintain the status quo of segregation and white supremacy. Despite this, the African-American community mobilised with growing determination. Leaders such as A. Philip Randolph and others had already organised resistance efforts, and the movement began to take shape around figures such as Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks and organisations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The civil rights movement engaged in a series of non-violent campaigns, including the famous Montgomery bus boycotts, sit-ins in segregationist restaurants, Freedom Rides, and the March on Washington. These events, often broadcast on national television, raised awareness of the civil rights cause among the American and international public and put considerable pressure on politicians to act. The courageous activism of African-Americans, political pressure and international moral outrage eventually led to major legislative advances. The involvement of African-American war veterans in this movement was a key factor, showing a stark contrast between the ideals they had fought for abroad and the reality at home. It also served as a poignant reminder that democracy at home requires active vigilance and participation to be fully realised.[[Image:Chicago Defender July 31 1948.jpg|thumb|150px|left|The ''Chicago Defender'' announces Executive Order 9981.]] | |||

The period of McCarthyism in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s was marked by an anti-Communist witch-hunt that affected all strata of society. Led by figures such as Senator Joseph McCarthy and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, the US government launched a series of investigations and prosecutions against people suspected of communist activities or considered threats to national security. J. Edgar Hoover, in particular, was notorious for his ruthless approach to those he considered subversive. Under his leadership, the FBI investigated individuals and groups linked to the civil rights movement. The suspicion was that communism sought to exploit racial inequalities in the United States to cause unrest and undermine the American government. As a result, many leaders and supporters of the civil rights movement found themselves under surveillance, their actions scrutinised for links to communism. Accusations of communism were often used to discredit the claims of civil rights activists, painting them as anti-American and subversive. This put a damper on some aspects of the movement, as leaders had to act with caution to avoid being accused of communist links, which could have led to serious legal and social consequences. Passport confiscation was another method used to limit the civil rights activist movement, preventing activists from travelling abroad where they could gather international support or embarrass the US government by revealing the extent of racial discrimination and segregation. However, despite the pressure and intimidation, the civil rights movement persevered. Leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr, who were initially suspected by the FBI of having communist links, continued to campaign for equality and justice. Their hard work and determination eventually contributed to major legislative changes in the 1960s, including the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, although activists continued to face surveillance and charges for many years. | |||

The establishment of the United Nations (UN) headquarters in New York in 1949 came at a time of profound transformation in international relations. The post-Second World War era saw the emergence of the United States as a decisive superpower and self-proclaimed defender of the values of freedom and democracy. However, the persistence of racial segregation and discrimination in the United States represented a glaring contradiction between these ideals and the reality experienced by African-Americans. The UN quickly became a stage where the decolonised countries of Africa and Asia could voice their concerns and seek support for their causes. For the United States, this meant increasing pressure to bring its domestic policies into line with its international human rights commitments. African and Asian delegates to the UN and leaders of newly independent nations used this platform to criticise segregation policies and encourage the US to adopt measures to end racial discrimination. In the context of the Cold War, the Soviet Union also exploited the American race issue to criticise the United States and attempt to gain influence among non-aligned nations. The irony of a nation preaching freedom and democracy while tolerating segregation and discrimination in its midst could not be ignored. This put the United States in a position where it not only had to fight Communist influence but also prove its commitment to human rights. Faced with this international pressure and ongoing struggles at home, the United States was forced to take concrete action. Under the administrations of presidents such as Harry S. Truman, who initiated the desegregation of the army in 1948, and later with Lyndon B. Johnson, who enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the country began to align its practices with its proclaimed principles. | |||

The international image of the United States was severely tarnished by the realities of the segregation and racial discrimination that persisted, particularly in the southern states. This contrasted starkly with the image the country sought to project as a world leader in freedom and democracy. | |||

Segregation in the Southern States was not confined to its citizens; it also extended to foreign visitors, including dignitaries and diplomats from newly decolonised African and Asian countries. The latter, often from countries that had fought for independence from the European colonial powers, were particularly sensitive to issues of sovereignty and human rights. Their direct experience of racial discrimination in the United States not only affected them personally but also had diplomatic repercussions, as it provided ammunition for the Soviet Union in its propaganda efforts. At the height of the Cold War, the Soviets were quick to point out these contradictions, using segregation and racial discrimination as examples of American hypocrisy. They used these facts to discredit the United States and reduce its influence, particularly among non-aligned nations seeking their own way between the capitalist Western bloc and the communist Eastern bloc. Although international pressure on human rights issues began to mount, it was not yet sufficient to compel the US government to make immediate and radical changes in the South. However, these international tensions increased sensitivity to racial issues and ultimately contributed to a heightened awareness among political elites and the American public at large. This dynamic played a role in creating a climate more conducive to the civil rights reforms of the 1960s. Even so, it took a relentless struggle by civil rights activists, mass demonstrations and a series of legal and legislative acts for the US government to formally end segregation and take significant steps to protect the rights of African-American citizens. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 are key examples, ending legal segregation and ensuring the protection of voting rights. These changes marked a crucial evolution not only in American society but also in the way the United States was perceived on the world stage. | |||

= | = The first stages of the struggle: from 1955 to 1960 = | ||

[[File:Warren Court 1953.jpg|thumb|right|On May 17, 1954, these men, members of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.]] | [[File:Warren Court 1953.jpg|thumb|right|On May 17, 1954, these men, members of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.]] | ||

The year 1954 represented a decisive turning point in the history of civil rights in the United States, marked by the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Under Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Court took a progressive turn and began to attack the institution of racial segregation, which had until then been supported by the legal precedent of "separate but equal" established in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson. In the unanimous decision of Brown v. Board of Education, the Court declared that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional because it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution, enshrined in the 14th Amendment. This decision marked the official end of the "separate but equal" doctrine and was the first major step towards desegregation in all areas of public life. The verdict was a major blow to the system of segregation in the South and had a signalling effect on the civil rights movement, spurring action and inspiring a generation of activists. However, the decision also provoked strong resistance in parts of the South, where politicians such as Alabama Governor George Wallace pledged to maintain segregation. The Brown decision also reinforced the role of the Supreme Court as an arbiter of constitutional rights, demonstrating that the judiciary could be an agent of social change. This precedent led to numerous other Court decisions that progressively eroded the legal structure of racial discrimination and strengthened civil rights in the United States. | |||

The Supreme Court's landmark decision in Brown v Board of Education was handed down in 1954, not 1955. This decision marked the beginning of deliberations about how to implement desegregation in schools, leading to a second decision in 1955, often referred to as Brown II, where the Court ordered that desegregation of public schools be done "with all deliberate speed". The NAACP, led by Thurgood Marshall, who would later become the first African-American Supreme Court Justice, played a central role in orchestrating and arguing the Brown case. They challenged the validity of the "separate but equal" doctrine that had been established by Plessy v Ferguson in 1896, which held that laws establishing separate schools for black and white students were constitutional as long as the schools were equivalent. Brown v. Board of Education was actually a collection of five cases under one umbrella because they all challenged racial segregation in public schools. The Supreme Court concluded that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional because it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, stating that segregation by its nature created inequality and had a detrimental effect on African-American children. This decision had a profound impact not only on the education system but on American society as a whole. It gave considerable impetus to the civil rights movement and set a legal precedent for other challenges to discriminatory laws and practices.[[File:President & First Lady Kennedy with Chief Justice Earl Warren & Mrs. Warren, circa 1962.jpg|thumb|left|200px|President and First Lady Kennedy with Chief Justice and Mrs. Warren, November 1963.]] | |||

Earl Warren | Earl Warren was appointed Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court in 1953, and it was under his leadership that the Court delivered its groundbreaking verdict in Brown v. Board of Education on 17 May 1954. Warren played a key role in this decision by persuading all the Supreme Court Justices to reach a unanimous consensus in order to present a united front against segregation in public education. Brown v. Board of Education was a landmark decision in the civil rights movement because it declared that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, overturning the "separate but equal" doctrine established by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. This decision marked an important milestone in the fight against Jim Crow laws and paved the way for further advances in civil rights. Earl Warren, as Chief Justice, continued to advocate progressive civil rights rulings, and his court is often credited with decisions that profoundly altered social and legal norms in the United States, particularly in the areas of civil rights, criminal justice, and the power of state and federal governments. | ||

Brown v. Board of Education established that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. However, the original 1954 decision did not include specific guidelines for implementing school integration. This led to the 1955 companion decision, known as Brown II, in which the Court ordered that desegregation be done "with all deliberate speed". NAACP lawyers, including Thurgood Marshall, presented compelling evidence that segregation by law produced inherent inequalities and harmed African-American children, both emotionally and educationally. The argument focused on the psychological damage that segregation inflicted on black children, drawing in part on the research of social psychologists such as Kenneth and Mamie Clark and their doll study, which demonstrated the effect of segregation on the self-esteem of African-American children. The Court's decision served as a catalyst for further change and encouraged civil rights activists to continue the fight against other forms of institutionalised segregation and discrimination. Despite this, many schools, particularly in the Southern states, resisted integration, leading to further legal and social conflict in the decades that followed. | |||

The US Supreme Court, under Chief Justice Earl Warren, issued a series of groundbreaking decisions that had a lasting impact on American society, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s. The landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 was a watershed, declaring racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional and overturning the "separate but equal" doctrine that had been in place since Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. Beyond Brown, the Court also strengthened the rights of the defence through landmark decisions such as Mapp v Ohio in 1961, which barred the use in court of evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment. In 1963, in Gideon v. Wainwright, the Court affirmed the right of defendants to a lawyer, even if they did not have the means to pay for one, thus guaranteeing a fair defence for all in the American legal system. In addition, Miranda v Arizona in 1966 introduced what are now known as "Miranda rights", requiring suspects to be informed of their rights, including the right to remain silent and the right to legal assistance. And in Loving v. Virginia in 1967, the Court struck down laws against interracial marriage, holding that such prohibitions violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Another area where the Warren Court has exerted considerable influence has been electoral reapportionment, most notably with the 1964 Reynolds v. Sims decision, which helped establish the principle of "one person, one vote", asserting that all citizens should have equal weight in electoral processes. These decisions collectively strengthened civil rights and individual liberties and encouraged a more inclusive vision of the US Constitution. The Warren Court's jurisprudence not only transformed the laws but also reflected and catalysed the social changes of the time, placing the Court at the heart of debates on equality and justice in the United States. | |||

Earl Warren, as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1953 to 1969, presided over an unprecedented period of judicial reform that extended civil rights and liberties to diverse and previously marginalised groups. His Court worked to dismantle legal systems and social practices that perpetuated discrimination and inequality. Under his leadership, the Court has made bold interpretations of the Constitution, extending the protections of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment far beyond issues of race and segregation. On women's rights, for example, the Warren Court laid the groundwork for future decisions that would recognise gender equality as an essential constitutional principle. Native Americans also benefited from this period of progressive jurisprudence. In several cases, the Court recognised and reinforced the sovereignty of indigenous nations, and required the federal government to respect treaties and agreements made with indigenous peoples. For Latin Americans, the Court has addressed issues of discrimination, particularly in employment and education, and has recognised the importance of protecting the civil rights of all ethnic groups. The rights of people living in poverty have also been strengthened by rulings that have challenged discrimination based on wealth, particularly in relation to access to criminal justice, such as the requirement for indigent defendants to have a lawyer. Finally, although the vast majority of legal advances concerning disability rights occurred after Warren's tenure, the Court's decisions during that time created a legal context conducive to the emergence of more inclusive legislation. The Warren Court is often celebrated for expanding the reach of the Constitution to include those who had been neglected or excluded by previous policies and practices, laying the groundwork for the civil rights, women's rights and other social justice movements that gained momentum in the 1970s and beyond. | |||

The decisions of the US Supreme Court in the years following the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 marked decisive turning points in the fight against segregation and discrimination. This ruling declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, thereby challenging the doctrine of "separate but equal" established by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. However, while these court decisions were fundamental, it is important to note that the end of legal segregation did not materialise immediately after Brown. There was significant resistance, particularly in the southern states, where segregation was deeply rooted in society. School integration was often accompanied by violence and opposition, requiring federal intervention, including the use of national guards to protect African-American students trying to enter schools previously reserved for whites. In addition, the Warren Court continued its work, issuing rulings that extended civil rights beyond the classroom. In areas such as the right to vote, access to public spaces, and the rights of those accused of crimes, the Court gradually removed legal barriers to equality. This included decisions such as Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, which upheld the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination in public places on the basis of race, colour, religion or national origin. At the same time, legislative advances such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which were adopted largely in response to the civil rights movement, were also decisive in ending institutionalised segregation and guaranteeing voting rights. | |||

The Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education was indeed a watershed moment in the history of civil rights in the United States. The official end to segregated schools sent a powerful message across the country that institutionalised inequality was unacceptable and unconstitutional. However, the implementation of this decision met with considerable resistance, particularly in the southern states. State and local governments often tried to circumvent or delay the implementation of desegregation. In the face of this resistance, the federal government had to intervene on several occasions to ensure that the constitutional rights of African-American citizens were respected. An emblematic example of this federal intervention is the Little Rock incident in 1957, when President Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne Division of the US Army to escort and protect nine African-American students, known as the "Little Rock Nine", who were entering Little Rock Central High School from the hostile crowd that was trying to prevent them from entering. In addition, the FBI and other federal agencies were mobilised to monitor civil rights violations and protect activists. The period following Brown's decision was marked by a series of legislation and government measures aimed at ensuring equal rights for all Americans, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. These measures were essential to eliminate discriminatory laws and practices in education, employment, housing, voting and access to public services. The impact of Brown's decision and subsequent federal actions extended far beyond the classroom, galvanising the civil rights movement and inspiring a generation of activists to fight for a more just and equal society. It also set a precedent for the use of federal power to protect civil rights, a principle that remains central to debates about social justice and equality to this day. | |||

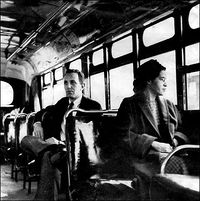

The virulent opposition to desegregation and civil rights led to a period of tumult and violence in American history. White supremacists and supporters of segregation often resorted to acts of domestic terrorism, such as the bombing of homes and schools attended or supported by African-Americans, in an attempt to roll back advances in social justice. Intimidation and violence against African-Americans were strategies used to maintain fear and discourage efforts at integration. Leading figures such as civil rights activist Medgar Evers were murdered, and tragic events such as the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, where four African-American girls were killed, became symbols of the struggle for equality and the brutality of resistance. The federal government, after initially hesitating, was pushed to act more firmly, especially after the violent events attracted national and international attention. Legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed to guarantee the rights of African-Americans, and President Johnson used the National Guard and other branches of the armed forces to protect citizens and enforce the laws. Nevertheless, even with the presence of federal troops and new laws, the transition to full and equal integration has been slow and fraught with challenges. Many African-Americans and their allies continued to face discrimination and violence, even when exercising such fundamental activities as voting, education and access to public services. The courage it took to confront this resistance and persevere in demanding equality was a testament to the resilience and determination of the civil rights movement.[[File:Rosaparks bus.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Parks on a Montgomery bus on December 21, 1956, the day Montgomery’s public transportation system was legally integrated. Behind Parks is Nicholas C. Chriss, a UPI reporter covering the event.]] | |||

Rosa Parks' act of civil disobedience became a powerful symbol of the fight against racial segregation and of the entire civil rights movement in the United States. By refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger on the bus that day in Montgomery, she not only challenged segregation but inspired an entire community to stand up for their rights. Her arrest for breaking segregation laws catalysed the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which demanded that African-Americans be treated fairly on the public transport system. The boycott, which lasted 381 days, not only highlighted the economic strength and unity of the African-American community, but also demonstrated the effectiveness of non-violent protest, a tactic that would become a cornerstone of the strategies of Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders. The decision by Rosa Parks, who was an experienced NAACP activist, was a deliberate choice to oppose injustice. She was already well aware of the struggles for civil rights and had been involved in many efforts to improve the condition of African-Americans in the segregated South. The impact of her action was immense. The boycott led to a federal court case, Browder v. Gayle, which eventually resulted in a Supreme Court decision declaring segregation on public buses unconstitutional. This was a major victory for the civil rights movement and highlighted the possibility of legal and social success through solidarity and non-violence. Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. became emblematic figures of resistance against discriminatory laws and for equal rights. Their courage and determination galvanised the movement, leading to profound legislative and social changes that would continue to unfold throughout the 1960s and beyond. | |||

Rosa Parks was much more than a seamstress; she was a seasoned activist, aware of racial injustices and determined to do something about them. Her role in the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) had prepared her to become a key player in the fight against segregation. On 1 December 1955, when she refused to give up her seat on the bus, she acted with full awareness of defying a discriminatory system and its potential consequences. The Montgomery bus boycott that followed her arrest was not simply a spontaneous movement; it was an action organised and supported by the black community, with the active participation of thousands of people. African-Americans in Montgomery chose to walk or find alternative means of transport rather than submit to a segregated public transport system. This collective determination exerted significant economic pressure on the city of Montgomery, which depended heavily on revenue from African-American passengers. The boycott was a resounding success, culminating in the Supreme Court's decision in Browder v Gayle, which declared segregated public buses unconstitutional. The integration of public transport in Montgomery became an example of a significant victory in the wider civil rights movement and demonstrated the power of non-violence and peaceful protest as tools for social change. Rosa Parks thus went down in history as "the mother of the civil rights movement", honoured and celebrated for her courage and essential role in the fight for equality.[[Image:Little Rock Nine protest.jpg|200px|thumb|right|Demonstrations by supporters of racial segregation in Little Rock in 1959, listening to a speech by Governor Orval Faubus protesting, in front of the Capitol, against the integration of 9 black pupils into the city's central high school.]] | |||

The incident at Little Rock Central High School in 1957 is one of the most dramatic and emblematic confrontations of the civil rights era. The "Little Rock Nine" were a group of nine African-American students who enrolled at Little Rock Central High School, a school hitherto reserved exclusively for whites. Their attempt to enter the school was fiercely resisted not only by some local white residents but also by the then Governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus. Faubus, an advocate of segregation, ordered the Arkansas National Guard to block the entry of African-American students, citing public safety concerns but clearly intending to support segregationist policies. This has led to disturbing scenes of young black students being harassed and threatened by angry mobs as they simply try to get to school. Faced with such a violation of civil rights and the international outrage it provoked, President Dwight D. Eisenhower felt compelled to intervene. He federalized the Arkansas National Guard and sent members of the army's 101st Airborne Division to protect the Little Rock Nine and enforce the federal integration order. The images of the American soldiers escorting the African-American students into the school through a hostile crowd were broadcast around the world, becoming a powerful symbol of the struggle for civil rights in the United States. This event highlighted the deep-rooted racial tensions in American society and highlighted the gap between the democratic values advocated by the United States and the reality of discrimination and segregation. In addition, the incident provided the Soviet Union with a propaganda opportunity during the Cold War, allowing it to criticise the United States for its racial inequality while diverting attention from its own repressive actions in Eastern Europe. For Soviet leaders, the troubles in Little Rock served as an example of the weaknesses and contradictions within American society, which they were eager to exploit in their ideological and geopolitical rivalry with the West. | |||

The Civil Rights Movement in the United States, which gained momentum in the 1950s and 1960s, was a defining period in the country's history. The movement was characterised by a series of non-violent protests and demonstrations aimed at challenging institutionalised racial segregation and promoting equal rights for African Americans. The Greensboro sit-ins of 1960 have become emblematic of this era of non-violent protest. During these sit-ins, four African-American students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University sat down at the whites-only counter at Woolworth's in Greensboro, North Carolina, and demanded to be served. When they were refused service because of segregation laws, they refused to leave their seats. Over the next few days, dozens and then hundreds of other students, black and white, joined the sit-ins, which quickly spread to other institutions across the South. Participants in the sit-ins often faced hostile reactions, ranging from verbal intimidation to physical violence, and many were arrested. However, the determination of the demonstrators and their commitment to non-violence drew national and international attention to the injustices of segregation. The courageous actions of these demonstrators have put pressure on business owners, legislators and public officials to change discriminatory laws and policies. The sit-ins also inspired other forms of non-violent protest, such as Freedom Rides, voting rights marches, and other peaceful demonstrations that were key tactics of the Civil Rights Movement. The combined efforts of protesters, civil leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and many others led to major legislative changes, including the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned racial discrimination in public places and jobs, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which aimed to remove barriers to voting for African Americans. The actions of the activists of the Civil Rights Movement therefore not only led to important legislative changes, but also raised public awareness and debate on racial issues in the United States, which have had repercussions on American society to this day. | |||

= | = The presidency of John F. Kennedy from January 1961 = | ||

John F. Kennedy, en tant que président, a porté une grande attention à la politique étrangère, en particulier à la suite de la montée des tensions de la Guerre froide avec l'Union soviétique. Des événements tels que la crise des missiles de Cuba en 1962, la construction du mur de Berlin, et l'escalade de l'engagement américain au Vietnam ont marqué sa présidence. Cependant, la pression du mouvement des droits civiques a progressivement forcé Kennedy à s'engager davantage sur les questions de ségrégation raciale. Au début de sa présidence, il a pris des mesures prudentes, telles que la nomination de juges progressistes et l'usage de son pouvoir exécutif pour soutenir des droits civils limités via des décrets, en partie parce qu'il devait ménager les politiciens démocrates des États du Sud, dont il avait besoin pour faire passer son agenda législatif. Malgré une approche initialement timide, les événements l'ont poussé à agir plus résolument. La confrontation avec le gouverneur de l'Alabama George Wallace sur la question de l'intégration de l'Université de l'Alabama, et les manifestations violentes à Birmingham, où la police a utilisé des chiens et des canons à eau contre les manifestants, ont capté l'attention du public et ont accru les appels à une action présidentielle. En réponse, Kennedy a présenté une législation complète sur les droits civiques en 1963, qui est devenue l'ébauche de ce qui sera plus tard le Civil Rights Act de 1964, adopté après son assassinat. Le 11 juin 1963, dans un discours télévisé à la nation, Kennedy a appelé à une nouvelle législation qui garantirait l'égalité pour tous les Américains, indépendamment de leur race, et a déclaré que la question des droits civiques était aussi vieille que la Constitution elle-même et qu'elle était maintenant « aussi pressante que jamais ». | John F. Kennedy, en tant que président, a porté une grande attention à la politique étrangère, en particulier à la suite de la montée des tensions de la Guerre froide avec l'Union soviétique. Des événements tels que la crise des missiles de Cuba en 1962, la construction du mur de Berlin, et l'escalade de l'engagement américain au Vietnam ont marqué sa présidence. Cependant, la pression du mouvement des droits civiques a progressivement forcé Kennedy à s'engager davantage sur les questions de ségrégation raciale. Au début de sa présidence, il a pris des mesures prudentes, telles que la nomination de juges progressistes et l'usage de son pouvoir exécutif pour soutenir des droits civils limités via des décrets, en partie parce qu'il devait ménager les politiciens démocrates des États du Sud, dont il avait besoin pour faire passer son agenda législatif. Malgré une approche initialement timide, les événements l'ont poussé à agir plus résolument. La confrontation avec le gouverneur de l'Alabama George Wallace sur la question de l'intégration de l'Université de l'Alabama, et les manifestations violentes à Birmingham, où la police a utilisé des chiens et des canons à eau contre les manifestants, ont capté l'attention du public et ont accru les appels à une action présidentielle. En réponse, Kennedy a présenté une législation complète sur les droits civiques en 1963, qui est devenue l'ébauche de ce qui sera plus tard le Civil Rights Act de 1964, adopté après son assassinat. Le 11 juin 1963, dans un discours télévisé à la nation, Kennedy a appelé à une nouvelle législation qui garantirait l'égalité pour tous les Américains, indépendamment de leur race, et a déclaré que la question des droits civiques était aussi vieille que la Constitution elle-même et qu'elle était maintenant « aussi pressante que jamais ». | ||

Version du 17 novembre 2023 à 11:47

Based on a lecture by Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

The Americas on the eve of independence ● The independence of the United States ● The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society ● The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas ● The independence of Latin American nations ● Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies ● The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery ● The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877 ● The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900 ● Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910 ● The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940 ● American society in the 1920s ● The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940 ● From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy ● Coups d'état and Latin American populisms ● The United States and World War II ● Latin America during the Second World War ● US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty ● The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution ● The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The civil rights movement in the United States marked an era of profound transformation in the American social and political fabric, fighting hard to dismantle racial segregation and abolish systematic discrimination against African-Americans. At the heart of this mid-20th century social revolution were determined young people, particularly daring students, who played a pivotal role in orchestrating and joining peaceful sit-ins, Freedom Rides and other forms of non-violent resistance. Their unwavering commitment not only captured the nation's attention but also ignited a wave of solidarity, inspiring people from all walks of life to get involved in the quest for equity.

Iconic figures such as the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr, who was himself young when he first became involved, embodied the spirit and resilience of the movement. Under their inspirational leadership, historic legislative advances were made, including the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, marking essential milestones towards a more just society.

The memory of Martin Luther King Jr, whose birth is commemorated every 15 January, lives on beyond his achievements. Federal Martin Luther King Jr. Day, established by President Ronald Reagan in 1983 and celebrated for the first time in January 1986, not only honours the legacy of this visionary leader but also embodies a call to action. Observed on the third Monday in January, the day encourages citizens to embrace community spirit and perpetuate King's legacy through civic service and acts of kindness, reaffirming the collective commitment to the ideals of peace and equality for which he fought so passionately.

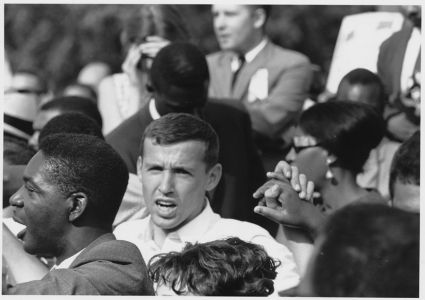

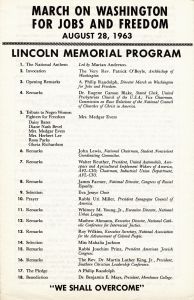

Speech delivered on 28 August 1963 before the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential speeches of the 20th century.[8] According to US Congressman John Lewis, who also spoke that day on behalf of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. "By speaking as he did, he educated, he inspired, he guided not just the people who were there, but people all over America and generations to come.[9]

During the annual commemorations of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the echoes of King's vibrant words ring out with particular resonance, particularly when his historic "I Have a Dream" speech is recalled. Delivered to a crowd of people at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, this speech has become emblematic of the fight for social justice. On this day of reflection and recognition, King's oratorical legacy is celebrated not only for its rhetorical power but also for its call to action in favour of equality and human dignity. King's words continue to galvanise communities around the values of diversity and respect for minority rights, while commemorating significant advances in the struggle for civil rights. However, beyond the tribute, his speeches are a poignant reminder of the need for continued commitment. They encourage introspection about the challenges of today in the quest to realise King's vision of a society without barriers of race, class or creed. The lessons of his speeches are universal and timeless, advocating a world where hope overcomes hatred, love triumphs over fear, and reconciliation breaks the chains of oppression. Martin Luther King's speeches remain etched in America's cultural heritage, inspiring new generations to continue the march towards a more inclusive and loving society. Today, as we strive to build bridges of understanding and equity, King's voice still resonates, urging us to remain steadfast in our commitment to justice and social harmony.

The "I Have a Dream" speech delivered by Martin Luther King Jr. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on 28 August 1963, during the March on Washington, remains one of the most powerful calls for social justice in modern history. In this eloquent message, King highlighted the deep scars of America - the abuses of segregation, the insidious obstacles to equal rights at work and at the ballot box, and the heavy burden of racial inequality weighing on the lives of African-Americans. King painted a stark picture of the America of his time, a nation riddled with glaring contradictions between its ideals of freedom and the reality of racial oppression. But instead of sinking into despair, King raised his voice in a vibrant symphony of optimism, weaving a prophetic vision of a transformed America. He not only spoke of dreams, he summoned the collective imagination to envision a renewed brotherhood where every man, woman and child would be measured by their shared humanity rather than arbitrary criteria of race or colour. The moral force of this speech lay in the audacity of a dream that transcended the boundaries established by history and unjust laws. King issued a resounding call to build a future where black and white children could hold hands as brothers and sisters, where the bells of freedom would ring in every corner of the land, and where justice would flow like waters and righteousness like an endless stream. It was not just the clarity of his message that captivated, but the passion with which he delivered it, a passion that continues to resonate just as strongly today. The 'I Have a Dream' speech encapsulated the dualism of the black American experience - the pain of the past and the hope of the future.

The resonance of Martin Luther King Jr's "I Have a Dream" speech undoubtedly served as a catalyst for the civil rights movement, galvanising public opinion and strengthening the resolve of activists. King's eloquence and the strength of the movement accelerated legislative change, pushing the federal government to act with greater urgency against institutionalised racial injustice. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 represented a crucial milestone in this struggle, embodying a radical shift in national policy towards segregation and discrimination. With its wide-ranging provisions, the Act dismantled the legal basis for segregation in public places and imposed equal access to employment, setting a new standard for civil rights in America. It also gave the federal government the power and authority to counter segregationist systems, particularly in the South. Complementing this legislation, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a decisive step forward in the democratisation of America. By ending discriminatory tactics such as literacy tests and other barriers that prevented African-Americans from voting, the Act fundamentally transformed the political landscape, opening the door to more equitable representation and participation. These two laws, the result of the relentless and often dangerous activism of civil rights campaigners, brought many of the movement's aspirations to fruition. They embodied the courage, perseverance and faith in humanity that were expressed in the streets, on the courthouse steps and in prison cells. The legacy of these laws, along with the efforts of figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and many others, marks a turning point in American history. Not only did they pave the way for formal equality before the law for African Americans, but they also laid the foundations for an ongoing national dialogue on justice, fairness and human rights.

The 14th and 15th Amendments were essential constitutional milestones in the long struggle for racial equality in the United States. Adopted during the Reconstruction era, they sought to redefine citizenship and civil rights at a time when America was recovering from the deep divisions of the Civil War. The 14th Amendment established a fundamental principle of equality before the law, designed to protect the rights of citizens, including freed former slaves. It introduced key citizenship clauses, the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause, which formed the basis of important legal decisions over the following centuries. The 15th Amendment followed, explicitly prohibiting racial discrimination in the exercise of the right to vote. This was a significant effort to include African Americans in American political life and to secure their right to participate in the governance of the country. Despite these constitutional protections, the reality was far from reflecting the proclaimed principles of equality. Practices such as Jim Crow laws, literacy tests, head taxes and grandfather clauses were designed to circumvent these amendments, de facto perpetuating the discrimination and exclusion of African-Americans from political and social life. The civil rights movement of the mid-20th century was a direct response to the failure of the states to live up to the promises of the 14th and 15th amendments. The legislation of the 1960s, specifically the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, were passed to systematically address the shortcomings and to force the enforcement of these constitutional rights. These laws not only strengthened legal protections for African Americans but also created mechanisms for federal enforcement, ensuring that the promises of the 14th and 15th Amendments could become a reality for all citizens. So while the amendments laid the theoretical groundwork for racial equality, it was the efforts of the civil rights movement and the resulting legislation that ultimately translated these principles into concrete action and real change.

It is true that the history of the United States is marked by profound contradictions between the ideals of freedom and equality set out in its founding documents and the realities of slavery, segregation and racial discrimination. The abolition of slavery with the 13th Amendment in 1865 marked a crucial step, but the end of slavery did not put an end to the inequality and oppression of African-Americans. Indeed, after the Civil War, systems of discrimination, such as Jim Crow laws in the South, were established to maintain strict separation and inequality between the races, going against the spirit of the 14th and 15th amendments. Redlining, mass incarceration and other policies also had a disproportionate impact on African-American communities, leading to long-term disparities in wealth, education, health and access to housing. However, it is important to note that racial segregation and discrimination were and are far from unique to the United States. Other countries in the Americas, such as Brazil and the Caribbean nations, also have a long history of racial discrimination and struggles for equality, although these systems did not always take the form of codified segregation laws as they did in the United States. Apartheid in South Africa is another example of an institutionalised system of racial discrimination and legal segregation that lasted until the mid-1990s.

Actors for change

The civil rights movement in the United States has a long history, dating back well before the iconic events of the 1950s and 1960s. Its roots lie in earlier struggles against slavery, post-Civil War reconstruction efforts, and ongoing resistance to Jim Crow laws and other institutionalised forms of racism. After the Civil War and the passage of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, African Americans continued to fight for their rights and status as full citizens. During the early 20th century, leaders such as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois took different approaches to promoting the advancement of black Americans. Du Bois' organisation, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, played a central role in the struggle for civil rights by using the legal system to challenge discriminatory laws and by conducting public awareness campaigns. The civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s saw a series of non-violent direct actions, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, initiated by Rosa Parks and led by the young Martin Luther King Jr, who emerged as one of the movement's leading figures. Lunch counter sit-ins, protest marches, Freedom Rides and numerous other acts of civil disobedience put pressure on the federal government and brought international attention to the cause of civil rights. Organisations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) played an important role in organising young activists and implementing mass protest strategies. Their efforts, and those of many others, led to the passage of key legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which marked a turning point in the struggle for equal civil rights for African Americans.

The struggle for black freedom in the United States was waged through a series of strategic and peaceful actions, guided by the principles of non-violence and civil disobedience. Inspired by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and led by figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, civil rights activists adopted a variety of tactics to challenge segregation and injustice. The Montgomery Bus Boycott was one of the first large-scale actions in which the black community stopped using public transport to protest against segregation laws. This prolonged boycott succeeded in exerting economic pressure that eventually led to the integration of buses in this city. At the same time, courageous sit-ins were organised in places traditionally reserved for whites, where African-Americans, often joined by white allies, sat down and refused to leave until they were either served or arrested, drawing national attention to the daily injustice of segregation. Peace marches also played a central role, with landmark moments such as the March on Washington, which saw King's iconic "I Have a Dream" speech become a symbol of the struggle for equality. Similarly, the Freedom Rides, where activists of different races travelled together through the South to challenge segregation laws on interstate transport, showed the strength of interracial solidarity and the determination to defy segregationist norms. In addition to these public protests, the struggle was also taken to court. Lawyers like Thurgood Marshall fought segregation through the court system, leading to landmark decisions like Brown v. Board of Education, which declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. In addition, voter registration work and political education were essential, particularly in the Deep South where discriminatory laws and practices hindered the right of African-Americans to vote. All of these efforts helped create a powerful national movement that not only raised public awareness of inequalities, but also put irresistible pressure on the federal government to act, ultimately leading to the passage of key civil rights legislation. The recognition of the rights of African Americans in the 1960s was no accident, but the result of decades of resistance, determination and commitment to the struggle for equality and justice.

The political landscape of the United States in the 1960s underwent significant transformations that were crucial to the advancement of civil rights. Initially, President John F. Kennedy was reluctant to commit fully to civil rights reform, concerned about the reactions of the deeply segregated South and the political calculations involved in retaining Southern support for the Democratic Party. However, the changing dynamics of the civil rights movement, accentuated by high-profile events such as the unrest in Birmingham, Alabama, where non-violent demonstrators, including children, were violently confronted by police, captured national and international attention. These shocking images, broadcast on television stations across the country, helped to raise public awareness and generate growing support for the cause of civil rights. Faced with this pressure and the calls for justice and equality, Kennedy was forced to act. In a landmark speech in June 1963, he called for new civil rights legislation that would establish equal protection under the law for all Americans, regardless of the colour of their skin. He presented Congress with a series of legislative proposals that laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. After Kennedy's assassination in November 1963, his successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson, made civil rights a priority of his administration. Johnson, using his experience and influence in Congress, skilfully manoeuvred the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex or national origin, and ended segregation in public places, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited discriminatory practices in voting procedures. These laws marked a significant break with the United States' discriminatory past and constituted official recognition of the civil rights of African-Americans, achieved through a combination of popular protest and political action at the highest level of government. These legislative changes were the culmination of a long and difficult struggle and marked a turning point in the history of civil rights in the United States.

The mid-1960s in the United States was a period of unprecedented change and social ferment, characterised by a wave of questioning of established norms and a collective struggle for a more inclusive and equitable society. At the heart of this transformation was the counterculture, a movement largely driven by young people who rejected the traditional values of American society. The counterculture advocated individual freedom, self-expression and experimentation, often in opposition to the Vietnam War, social inequality and racial discrimination. The feminist movement, gaining in visibility and influence, was also a crucial element of this period. With the publication of iconic works such as Betty Friedan's "The Mystified Woman", women began to openly challenge traditional gender roles, demanding equal rights and personal autonomy, goals that paralleled those of the civil rights movement. At the same time, the anti-war movement intensified, fuelled by growing opposition to US military involvement in Vietnam. Millions of people, particularly students, took part in demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience, creating a united front of dissent against government policies. These social movements were interconnected, with participants often engaged in several causes simultaneously, creating a network of solidarity that crossed the boundaries of individual movements. The civil rights movement benefited from this solidarity, as it shared a common goal with other movements: the transformation of society into a fairer place for all its members. Thus, in this climate of widespread activism, the civil rights movement was able to find fertile ground in which to flourish and pursue its goals of ending segregation and achieving racial equality. The various social struggles of the time were mutually reinforcing, each victory providing impetus for the others, and together they helped to redefine the political, social and cultural landscape of the United States.

The impact of the Civil Rights Movement went beyond the borders of the United States, drawing international attention to issues of social justice and racial inequality. In the context of the Cold War, the image of the United States was closely scrutinised and the struggle for civil rights became a critical point in the international discourse on human rights. America presented itself as the leader of the free world, a model of democracy and freedom, but images of police brutality and severe racial discrimination against African-Americans were in flagrant contradiction with this image. This put pressure on successive US governments to address these issues not only for domestic moral and legal reasons, but also to maintain their credibility on the world stage. In addition, the civil rights movement has served as a source of inspiration and example for other liberation and social justice movements around the world. The non-violent civil disobedience tactics and eloquent speeches of leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. have resonated with those fighting oppression and discrimination in other countries. For example, the strategies and ideals of the Civil Rights Movement have influenced anti-apartheid movements in South Africa and civil rights struggles in Europe and elsewhere. In this way, the recognition of the rights of African-Americans and the progress made in the 1960s were not simply the result of an internal movement, but also reflected a global dialogue on human rights and dignity. The progress made in the United States strengthened the global civil rights movement and helped promote an international consciousness around equality and justice for all.

African-Americans in the South

The return of the African-American veterans of the Second World War marked a decisive turning point in the civil rights movement in the United States. These men and women had fought for freedom and justice abroad, often demonstrating bravery and skill in very difficult circumstances, only to return to a country where they were treated as second-class citizens, denied civil rights and subjected to racial segregation and discrimination. This stark contrast between the ideals they had fought for and the reality they faced on their return fuelled a strong resolve and commitment to change. Many of these veterans became key leaders and activists in the civil rights movement, building on the leadership and organisational skills they had acquired in the military. They were less willing to tolerate injustice and more willing to organise and demand their rights. In addition, their service provided a powerful refutation of racist stereotypes. Their courage and sacrifice proved that they deserved respect and full citizenship, highlighting the contradictions of American society. The situation of African-American veterans was often cited in arguments against segregation and for equal rights, adding a moral urgency to the struggle for social change. Their influence was felt in mass demonstrations, actions of civil disobedience and legal challenges to Jim Crow laws. Their determination helped inspire a movement that eventually led to major legislative changes, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, marking a significant step forward in the quest for racial equality in the United States.

African Americans have drawn inspiration and strength from struggles for freedom and equality around the world. In the mid-twentieth century, the rise of the decolonisation movements in Africa and Asia offered striking parallels with their own struggles for civil and social rights. Victories against colonial and imperial oppression reinforced the belief that change was possible, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Back in the United States, African-Americans organised themselves in a more structured way to oppose segregation and discrimination. Organisations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) played central roles in coordinating resistance efforts. Figures such as Rosa Parks, whose refusal to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, sparked the famous Montgomery Bus Boycott, and young activists who initiated the Greensboro sit-ins, demonstrated the effectiveness of non-violent civil disobedience. These actions were often orchestrated to draw national and international attention to injustices. Sit-ins, protest marches, Freedom Rides and other forms of peaceful protest and demonstration have shown impressive solidarity and determination to achieve equality. They have also often provoked a violent reaction from the authorities and from white citizens' groups, which has drawn even more public attention and increased the pressure for change. The success of these efforts was marked not only by the passage of legislation such as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, but also by a gradual shift in the public perception of racial justice and civil rights. These changes were a testament to the power of collective organisation and non-violent protest, and continue to inspire social movements to this day.

The individual and collective courage of African Americans in the South was an undeniable force for change in the civil rights movement. Often risking their lives, they confronted an institutionally racist system. Their persistence in demanding dignity and equality served as a catalyst for legislative reform and considerable social change. The struggle for civil rights in the South was characterised by heroic acts of ordinary people who took part in boycotts, marches, sit-ins and other forms of peaceful protest. Images of peaceful demonstrators facing police violence, mass arrests, and even acts of terrorism perpetrated by citizens and local authorities have outraged many people in the United States and around the world. Events such as the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, where four young African-American girls were killed, highlighted the cruelty and injustice of systemic racism. The actions of African-American activists have highlighted the gap between the ideals of freedom and equality advocated by the United States and the reality experienced by a large part of its population. Increased media and international attention put pressure on politicians to act, ultimately leading to the passage of important legislation to guarantee civil rights. This activism also inspired other marginalised groups, both in the US and abroad, to fight for their rights, showing that change was possible through determination and solidarity. The legacy of these efforts lies in the continuing struggles for equality and justice for all, a quest that continues to shape today's dialogues and policies around race, justice and equality.

The bravery and commitment of African Americans in the South was fundamental to the success of the Civil Rights Movement. It was their refusal to give in to systemic oppression, their determination to fight for equality and their willingness to sacrifice that fuelled the progress made. Despite the constant danger, these men and women marched, spoke, resisted and sometimes even gave their lives for the cause of justice. Their struggle has had a ripple effect, not only in the communities directly affected by segregation and discrimination, but across the country and around the world. They inspired a generation of civil rights activists and laid the foundations for the struggles for equality that continue today. The impact of their struggle goes far beyond legislative advances. It helped shape the national consciousness, educate the public about the realities of discrimination and profoundly transform American culture and values. Their legacy lives on not only in the laws and policies they helped to change, but also in the spirit of resistance and the quest for justice that continues to guide contemporary social movements.

The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States has had a profound and lasting impact on the development of civil rights and equality in the country. Its jurisprudence has spanned several eras, marking significant turning points in American history. For example, the landmark 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education overturned the doctrine of "separate but equal" and declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. This laid the groundwork for a series of civil rights reforms. Later, in 1967, the Court issued another landmark decision in Loving v. Virginia, ending laws that prohibited interracial marriage. The Court has continued to shape the civil rights landscape with decisions such as Roe v. Wade in 1973, which established the right to abortion, although this decision was subsequently overturned in 2022. In a more contemporary context, the Court affirmed gay rights in 2015 with Obergefell v. Hodges, guaranteeing the right to marry for same-sex couples, a decision that marked a major step forward for LGBTQ+ equal rights. However, it is important to note that the Supreme Court has not always followed a linear progressive trajectory. While some decisions have clearly pushed society in a more inclusive direction, others have reflected a more cautious or conservative approach, particularly in the years leading up to the civil rights era and, more recently, with the rollback of certain protections. Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, for example, eroded certain provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, reflecting a shift in the Court's policy. The Court's trajectory often reflects the deep ideological divisions that characterise American society. Thus, while it has sometimes acted as a catalyst for progressive reform, the Court has also acted as a mirror for conservative forces, highlighting the complexity of its role in the history of civil rights in the United States.

In the mid-twentieth century, the United States was at a critical juncture in terms of civil rights. The Supreme Court played an essential role in this area, making decisions that reshaped American society. Among the most important decisions was Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, in which the Court ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, contradicting the doctrine of "separate but equal" established in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. This Supreme Court decision marked a decisive moment, triggering resistance but also inspiring a movement towards greater and fairer integration in educational establishments. It meant that segregating pupils on the basis of race deprived black children of equal opportunities, which was in conflict with the US Constitution, in particular the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equal protection of the laws to all citizens. By declaring school segregation unconstitutional, the Supreme Court sent a clear message against the Jim Crow laws that maintained segregation in other spheres of public life. It also motivated civil rights activists and was followed by other court rulings and legislation that continued to fight racial discrimination and promote equal rights for all Americans, laying the groundwork for future social change.

The 1960s was a pivotal time for the United States in terms of civil justice and equality. The US Supreme Court, acting as the guardian of constitutional rights, took decisive steps to eliminate discrimination and promote equality. Among the notable cases, Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States was particularly significant. In this case, the Court ruled that Congress had the power under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution to prohibit racial discrimination in private establishments such as hotels and restaurants, which affected interstate commerce. This meant that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was not just a moral ideal but a legal obligation that businesses had to abide by or face prosecution and punishment. In upholding this law, the Court held that racial discrimination in public spaces was not only a matter of social justice but also an impediment to commerce and the national economy. The decision therefore had a profound impact, extending civil rights protections beyond education and into commerce and public services. It affirmed the role of the federal government in protecting the rights of citizens and helped to dismantle the vestiges of legal segregation. Along with other similar rulings, the Court set a precedent for strengthening civil rights and paved the way for a more inclusive and just America.

The decisions of the US Supreme Court during the 1950s and 1960s laid the foundations for a lasting legal framework for civil rights. The rulings made during this period dismantled many discriminatory laws and practices, and redefined the understanding of constitutional rights in the United States. These rulings were not limited to racial issues, but also addressed other areas of discrimination and inequality. For example, after Brown v. Board of Education, other decisions followed, reinforcing the nation's commitment to equal treatment in various sectors of society. Loving v. Virginia in 1967 put an end to laws prohibiting interracial marriage, underlining the importance of protecting equality in the personal and private spheres. Over the years, the Court has continued to play a crucial role in interpreting the Constitution, often in response to social movements and evolving standards of justice. Whether by refining the rights of the accused, extending protections against discrimination, or addressing new legal issues related to technology and privacy, the Supreme Court has demonstrated its ability and willingness to adapt constitutional law to contemporary realities. The Supreme Court's power to determine the constitutionality of laws and practices has made it a central arena for civil rights debates. Its decisions, while they cannot by themselves eliminate all forms of discrimination or prejudice, set legal standards that shape public policy and influence culture and attitudes. The precedents it sets continue to resonate, illustrating how the law can be used as a tool for social change and progress.

Domestic and international context

Internal structural changes

The Great Migration is a key element in the history of America and the civil rights movement. This mass migration of African Americans, which took place in two major waves between 1916 and 1970, transformed the demography, culture and politics of cities in the North and West of the United States. Fleeing the institutionalised discrimination and limited economic opportunities of the South, African Americans settled in new areas where they hoped to find greater equality of rights and better living conditions. However, discrimination and segregation often followed them into these new urban environments, although in different forms to those in the South. In the cities of the North and West, African-Americans were often confined to overcrowded and run-down neighbourhoods, subjected to discriminatory employment practices and confronted with new forms of racial segregation. Despite these challenges, the Great Migration had profoundly positive effects for the civil rights movement. By moving a significant portion of the African-American population out of the South, where the majority of Jim Crow laws were in force, it enabled African-Americans to make their voices heard in areas where they could exercise their right to vote with fewer obstacles. This migration also led to the creation of robust urban black communities with their own institutions, businesses and political organisations, which provided a basis for activism and change. Moreover, the concentration of African-Americans in major urban centres has changed the political dynamic, giving black voters a new electoral clout and pushing civil rights issues up the national political agenda. The race riots that broke out in several cities in the mid-20th century also drew attention to racial inequalities and spurred political leaders to action. The experience of African-Americans during the Second World War, where they served their country in the hope of proving their equal citizenship, also fuelled the desire for social justice and equality after the war. The contrast between the struggle for freedom abroad and discrimination at home was too stark to ignore, and many began to clamour for the rights they had fought for.