« An analytical approach to institutions in political science » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

|||

| (11 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 9 : | Ligne 9 : | ||

{{hidden | {{hidden | ||

|[[Introduction to Political Science]] | |[[Introduction to Political Science]] | ||

|[[ | |[[Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory]] ● [[The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic]] ● [[Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory]] ● [[The notion of "concept" in social sciences]] ● [[History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts]] ● [[Marxism and Structuralism]] ● [[Functionalism and Systemism]] ● [[Interactionism and Constructivism]] ● [[The theories of political anthropology]] ● [[The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas]] ● [[Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science]] ● [[An analytical approach to institutions in political science]] ● [[The study of ideas and ideologies in political science]] ● [[Theories of war in political science]] ● [[The War: Concepts and Evolutions]] ● [[The reason of State]] ● [[State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance]] ● [[Theories of violence in political science]] ● [[Welfare State and Biopower]] ● [[Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes]] ● [[Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences]] ● [[The system of government in democracies]] ● [[Morphology of contestations]] ● [[Action in Political Theory]] ● [[Introduction to Swiss politics]] ● [[Introduction to political behaviour]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation]] ● [[Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations]] ● [[Introduction to Political Theory]] | ||

|headerstyle=background:#ffffff | |headerstyle=background:#ffffff | ||

|style=text-align:center; | |style=text-align:center; | ||

| Ligne 91 : | Ligne 91 : | ||

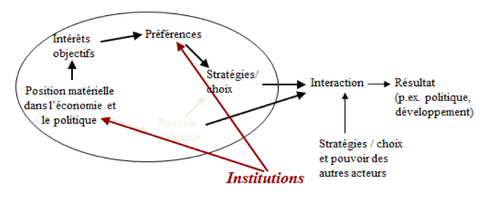

= How do institutions influence results? = | = How do institutions influence results? = | ||

Institutions have a key role in shaping policy and can influence policy in three main ways: | |||

# | # By '''influencing the capabilities of different actors''': Institutions can confer or restrict the power of different actors depending on the rules and procedures they establish. For example, a constitution may determine the government's responsibilities and powers granted to different bodies or individuals. This can affect the ability of these actors to implement policies or influence the political process. | ||

# | # By '''altering stakeholder preferences''': Institutions can also shape stakeholder preferences by defining what is considered acceptable or desirable in a given society. For example, social norms, which are a form of institution, can influence individuals' policy preferences by establishing what is considered good or bad behaviour. | ||

# | # By '''influencing the strategies of individuals or states''': Finally, institutions can affect the strategies that individuals or states choose to adopt in order to achieve their objectives. For example, electoral rules can influence a political party's strategy during an election campaign. Similarly, international treaties can influence a state's diplomatic or foreign policy strategy. | ||

Institutions are powerful forces that can shape the political landscape by influencing political actors' capabilities, preferences and strategies. | |||

== Influence | == Influence of institutions on political power == | ||

Institutions play a major role in determining and limiting political power in any society. Here's how they can influence political power: | |||

* '''Structure | * '''Structure of government''': Institutions can define the structure of government and distribute power between the different branches of government, such as the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. This can have an impact on the balance of power and prevent abuses of power. For example, a country's constitution is an institution that clearly establishes how the government is to be organised and how power is to be exercised. | ||

* ''' | * '''Regulation of political behaviour''': Institutions can regulate the behaviour of political actors through laws, standards and regulations. This may include rules on campaign finance, electoral conduct, lobbying and other aspects of the political process. | ||

* ''' | * '''Public opinion formation''': Certain institutions, such as the media or education, can influence public opinion, which in turn can influence political power. For example, the media can highlight certain issues, shape public debate and influence public opinion, which in turn can impact politics. | ||

* ''' | * '''Facilitating civic participation''': Institutions can also facilitate or hinder citizens' participation in political life. For example, voting laws, voting procedures and campaign finance rules can all influence who can participate in the political process and how. | ||

* ''' | * '''Monitoring the implementation of policies''': Institutions such as the judiciary or regulatory bodies can monitor the implementation of policies and ensure that political power is exercised in accordance with the laws and regulations in force. | ||

[[Fichier:Influence des institutions sur pouvoir politique.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Influence des institutions sur pouvoir politique.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | ||

In the context of political science, institutions can play a central role in structuring and modulating power relations, whether within a state or between different states. | |||

* '''NAFTA - North-American Free Trade Agreement''' | * '''NAFTA - North-American Free Trade Agreement''' | ||

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), now replaced by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), illustrates how an institution can influence the power of different actors in a political system. The aim of these agreements was to create a single market between the United States, Canada and Mexico, where goods could circulate without tariffs. This has undoubtedly strengthened the power of multinational companies, allowing them to move production to regions with lower labour costs, such as Mexico. This has opened up opportunities to maximise profits by taking advantage of geographical proximity to keep transport costs relatively low. This is a striking example of how institutions can reshape the political and economic landscape, redistributing power and creating new dynamics. | |||

Trade agreements such as NAFTA have given multinational companies greater power, mainly through their increased ability to relocate production. This power is largely due to the mobility of companies, while workers are generally more tied to a specific locality. The increased mobility of companies allows them to respond to costs and working conditions by relocating production to locations where these factors are more favourable. This creates a dynamic where companies can potentially threaten to relocate production if workers demand better working conditions, higher wages or other improvements. This can lead to downward pressure on wages and working conditions as workers are forced to compete internationally. | |||

*''' | *'''United Nations Security Council''' | ||

The United Nations Security Council is another body where institutions play a major role in the distribution of political power. The five permanent members of the Security Council - France, the United Kingdom, the United States, Russia and China - each have the right to veto any substantive resolution. This means that they can block any decision with which they disagree, regardless of the support that decision may receive from the other members of the Security Council. This institutional arrangement gives considerable power to the five permanent members, allowing them to exert a disproportionate influence on international policy. It also allows them to use their veto power to counter the potential emergence of new global or regional powers. For example, they can use their veto to block the admission of new permanent members, such as India or Brazil, or to counter the international ambitions of countries such as Iran. | |||

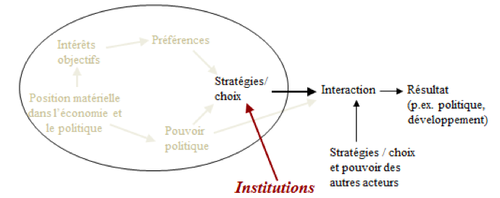

== | == The influence of institutions on preferences == | ||

Institutions play a key role in the formation and evolution of individual and collective preferences. On the one hand, they can influence preferences through the socialisation process. For example, education as an institution plays a crucial role in shaping people's values, attitudes and beliefs. Religious, cultural and family institutions also play a major role in shaping individual preferences. On the other hand, institutions also have an indirect effect on preferences by determining the material position of the individual or agent in the economy and politics. For example, economic institutions such as the labour market, social protection systems and tax policies can influence individuals' preferences in terms of resource allocation or public policy. Similarly, political institutions, such as the electoral system, can influence people's preferences in terms of political participation and support for different political ideologies. Institutions have a considerable influence on the way in which individuals perceive their options and make their choices, and therefore play a central role in the formation and evolution of preferences. | |||

The socialisation effect is a process by which individuals acquire attitudes, beliefs, norms and behaviours specific to a given group or society. In the institutional context, this socialisation effect is often intensified by strong institutional norms and regular interactions between members of the institution. For example, an institution such as a university or a company may have a very strong organisational culture which influences the beliefs, attitudes and behaviours of its members. Through regular and repeated interactions over time, individuals can internalise the institution's norms and values, which can influence the way they think and behave, both inside and outside the institution. Political institutions can also have a socialising effect. For example, a political party may have strong norms and ideologies that influence the beliefs and behaviours of its members. Similarly, government institutions may have norms and procedures that influence the way public servants think and act. This can be particularly important in shaping public policy and governance. | |||

[[Fichier:Influence des institutions sur les préférences.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | |||

A key phenomenon in global politics and economic development is the influence of global elites on the political and economic preferences of national elites, particularly in developing countries. Through repeated interactions, for example at international conferences or meetings in Washington, elites in developing countries can be exposed to ideas, norms and beliefs that are predominant among global elites, such as the belief in the benefits of free trade. Although they may initially be reluctant to embrace these ideas because of their own national or sectoral interests, these elites may end up being convinced by the dominant discourse, especially if they see evidence of its success elsewhere. These regular interactions can therefore lead to a kind of 'ideological convergence' or political socialisation, where elites in developing countries gradually adopt the beliefs and preferences of global elites. This in turn can influence the policies implemented in their home countries, and can potentially have significant impacts on the economic and political development of these countries. | |||

A common trend observed in many countries making the transition to democracy is that military elites, who have often played an important role in authoritarian regimes, may be reluctant to cede power to civilian authorities. They may fear the loss of their autonomy, privileged status and material advantages. The example of Spain in 1981 is a good illustration of this dynamic. Despite the transition to democracy initiated in 1975 after the death of the dictator Francisco Franco, certain elements of the armed forces tried to overthrow the democratically elected government in a coup d'état. However, the coup d'état failed, and Spain continued along the road to democracy. Egypt offers another example of this dynamic, where the military negotiated a privileged position in the post-revolutionary regime. After the 2011 revolution that toppled President Hosni Mubarak, the military played an important role in the new regime. This led to tensions and conflicts with civilian forces seeking to establish a more open and inclusive democracy. These examples show that the transition to democracy can be a complex and often contested process, with different groups struggling for power and trying to preserve their interests. Political institutions, notably the army and other structures inherited from previous regimes, play a key role in this process. | |||

The modernisation of the Spanish armed forces and their integration into NATO in the 1970s played an important role in the country's democratic transition. Through this integration and joint exercises with other NATO armed forces, Spain's military elites were exposed to new military norms and practices, in which the military is subordinate to political power. This socialisation may have influenced the preferences of Spain's military elites and helped them to understand their role in a democratic system. This is an excellent example of how international institutions and interactions between countries can influence internal political transformations. By participating in these joint exercises and engaging with their NATO counterparts, the Spanish military has been able to see how armies operate in established democracies. This experience has probably helped to shape their understanding of the appropriate role of the army in a democracy and to modify their preferences accordingly. Thus, this process of socialisation and interaction played a key role in redefining the preferences and attitudes of Spain's military elites, facilitating the country's transition to democracy. This is an excellent example of how institutions - in this case, NATO - can influence the political process at national level. | |||

A complex situation arose during the debt crisis in Greece, a member of the European Monetary Union. Normally, a country with a large budget deficit and high public debt faces higher interest rates from international investors. This happens because the risk associated with investing in that country increases, and investors demand a risk premium to compensate for this additional risk. However, in the case of Greece, membership of the European Monetary Union has changed this dynamic somewhat. As a member of the eurozone, Greece had access to relatively low interest rates thanks to the perception that the euro, backed by the European Central Bank and strong eurozone economies such as Germany and France, was a stable currency. This allowed Greece to continue borrowing at relatively low interest rates despite its large budget deficits. However, when the reality of Greece's budget problems became apparent and investor confidence began to falter, Greece was faced with a debt crisis, with interest rates on sovereign debt rising rapidly. The crisis eventually required an international rescue plan and draconian economic reforms imposed by the troika (the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund). This illustrates how institutions, in this case the European Monetary Union, can influence economic and political dynamics at national level, sometimes in unexpected ways. | |||

Greece's membership of the European Monetary Union has enabled the country to pursue an expansionary fiscal policy while benefiting from low interest rates on its debt. This is due to the perception that eurozone countries share a certain security and stability, which has been supported by the European Central Bank. However, in the long term, this led to an accumulation of unsustainable debt which eventually led to Greece's financial crisis. Once Greece's financial problems were exposed and investors began to doubt the country's ability to repay its debts, interest rates rose significantly, exacerbating the country's financial problems. What happened in Greece is an example of how institutions, in this case the European Monetary Union, can affect the behaviour of member countries and the political decisions they take. It is also an example of how these behaviours can have unforeseen and potentially devastating consequences. | |||

== The influence of institutions on strategies and interactions == | |||

From a work by Davis entitled ''International Institutions and Issue Linkage: Building Support for Agricultural Trade Liberalization'', we can understand how the institutional context of multilateral international trade negotiations influences state strategies and outcomes.<ref> CHRISTINA L. DAVIS - [https://www.princeton.edu/~cldavis/files/linkage.pdf International Institutions and Issue Linkage: Building Support for Agricultural Trade Liberalization]. American Political Science Review Vol. 98, No. 1 February 2004</ref> Davis's research demonstrates that international institutions, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), can influence the negotiating strategies of member states, as well as the outcomes of negotiations. The WTO is an institution that promotes the liberalisation of international trade by establishing rules for trade and providing a platform for trade negotiations. | |||

Davis | In trade negotiations, WTO member states can adopt different strategies to defend their interests. They may choose to focus on specific areas, such as agriculture, or adopt a broader approach, linking several issues together. For example, a country might be prepared to make concessions on agricultural market access in exchange for better market access for its industrial products. According to Davis, the WTO encourages 'issue linking', i.e. the inclusion of several negotiating subjects in a single set of discussions. This allows member states to build broader coalitions and reach more favourable agreements. For example, a country with a strong agricultural sector could ally itself with a country with a strong industrial sector to obtain mutually beneficial concessions. However, Davis notes that the link between issues can also make negotiations more complex and more difficult to conclude. This may partly explain why multilateral trade negotiations are often long and difficult. International institutions such as the WTO can influence the negotiating strategies of member states and the outcome of negotiations. They can encourage states to adopt more complex strategies and to link several issues together, but this can also make negotiations more complex and more difficult to conclude. | ||

[[Fichier:Influence des institutions sur les stratégies et les interactions.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | |||

Davis highlights that when trade negotiations are conducted on a sector-by-sector basis, developed countries often find it difficult to liberalise their agricultural sectors. This is due to the presence of powerful political and economic interests that resist liberalisation, as can be seen with the Swiss Farmers' Association in Switzerland, or the French farmers who manage to protect the European market from imported agricultural products. These interest groups can significantly influence agricultural policy and resist pressure to open up the market. | |||

When negotiations are conducted on a sectoral basis, it can be very difficult to achieve trade liberalisation, particularly in the agricultural sector. This is due to the powerful political and economic interests that can exist within this sector, which can strongly resist any attempt at liberalisation. In addition, issues relating to food security, rural employment and environmental protection can also make liberalisation of the agricultural sector particularly complex. | |||

When an institutional innovation is put in place through the concept of issue linkage, a more or less formal structure designed to bring together different issues, the negotiation framework is broadened. Instead of negotiating issue by issue and sector by sector, the liberalisation of one sector, such as services, can be linked to other issues. This approach can facilitate negotiations, as it allows the interests of different players to be considered and the gains and losses between different sectors to be balanced. For example, a state might be prepared to accept liberalisation in a sector with defensive interests if, in return, it obtains gains in another sector with offensive interests. | |||

The author shows that creating a link between agriculture and services can encourage and promote trade liberalisation. This is because a state may be prepared to accept liberalisation in a sector where it has defensive interests (e.g. agriculture), if in return it obtains gains in another sector where it has offensive interests (e.g. services). This approach makes it possible to balance gains and losses between different sectors, thereby facilitating trade negotiations. This is what is known as "issue linkage", a key mechanism in multilateral negotiations. | |||

The idea of creating links or "issue linkage" between different areas of negotiation makes it possible to rethink how interest groups mobilise. Instead of opposing each other on specific issues, different groups can collaborate and lobby together to achieve common goals. For example, an industrial sector that benefits from trade liberalisation could lobby jointly with an agricultural sector to support the liberalisation of agriculture. Industry would benefit from the opening up of agricultural markets and agriculture would benefit from the opening up of industrial markets. This can lead to stronger mobilisation for trade liberalisation in general. It can reconfigure the political landscape and create new alliances between players with common interests. It can also help overcome obstacles to liberalisation by making it easier to negotiate compromises. For example, if a sector is reluctant to liberalise, it may be more willing to do so if other sectors are also open to competition. However, it must also be borne in mind that this process can give rise to conflicts between interest groups who feel aggrieved by these arrangements and who may mobilise to oppose them. Managing these tensions is, therefore, a key factor in the success of linkage strategies. | |||

The state may have different preferences in different areas. For example, it may prefer not to liberalise the agricultural sector to protect farmers' interests. Still, it may be more willing to liberalise the services sector if it sees an economic advantage in doing so. The introduction of the "issue linkage" mechanism, or the creation of links between different areas of negotiation, can modify the State's strategy. Even if the state's preferences remain the same, it may be prepared to accept costs (such as the impact of liberalisation on the agricultural sector) if this enables it to obtain gains (such as opening up the services sector to international competition). This shows how institutions, even informal ones, can influence national strategies by reconfiguring the negotiating stakes. However, it is important to note that this process can also give rise to conflicts and tensions, particularly if certain stakeholders feel aggrieved by the changes. Managing these conflicts is crucial to the success of issue linkage strategies. | |||

Neo-institutionalism recognises the importance of conflicts of interest in politics and the economy but focuses on how institutions structure these conflicts and determine their outcomes. By their very nature, institutions create rules of the game that may favour some actors at the expense of others. This means that although interests and resources can influence political and economic dynamics, the institutional structure determines who has power and controls resources. Institutions can either reinforce existing power inequalities or help to mitigate them. The institutionalist perspective is, therefore, an important contribution to our understanding of politics and economics, as it highlights the central role of institutions in determining power relations and political and economic outcomes. This approach adds a further dimension to the analysis of conflicts of interest by showing how institutional structures can influence actors' strategies and the outcomes of their actions. | |||

= Institutionnalisme-historique = | = Institutionnalisme-historique = | ||

| Ligne 163 : | Ligne 167 : | ||

== Unanticipated - unintended consequences == | == Unanticipated - unintended consequences == | ||

Neo-institutionalism refers to a resurgence and new focus on institutions in the social sciences from the 1980s onwards, following a period when functionalism and behaviourism dominated. However, the concept of 'unintended' or 'unanticipated' consequences has a broader scope and is embedded in many theoretical approaches, including institutionalism. The concept of unintended consequences, originally formulated by the sociologist Robert K. Merton, refers to outcomes that are not those initially anticipated by an action or decision. These consequences may be positive, negative or simply unforeseen. For example, a government policy may have unanticipated social or economic consequences that were not foreseen when it was conceived. | |||

In the context of historical institutionalism, unintended consequences can be linked to the way in which institutions are constructed and evolve. For example, an institution created to solve a certain problem may have unanticipated side-effects that influence other aspects of society. The emphasis on unintended consequences highlights the complexity of social and political systems, and how decisions taken in one area can affect other areas in sometimes surprising ways. It also reflects that institutions are constantly evolving and their effects can change over time. | |||

* | Neo-institutionalism has brought a new perspective to the way institutions are studied: | ||

* | * '''Importance of institutions''': Neo-institutionalism considers that institutions play a crucial role in structuring social, political and economic life. They are not simply arenas in which social and political actors pursue their interests, but structures that shape and influence these interests. | ||

* | * '''Autonomy of institutions''': Neo-institutionalists argue that institutions have a degree of autonomy from social, economic and political forces. In other words, they can influence behaviour and outcomes independently of the interests of the actors within them. | ||

* | * '''Formal and informal institutions''': Neo-institutionalism has broadened the scope of research to include not only formal institutions (such as governments, laws and formal organisations) but also informal institutions (such as social norms, customs and unwritten practices). This reflects the recognition that behaviour is influenced by a wider range of structures than those formally codified. | ||

* The '''role of time and history''': Some neo-institutionalists, notably those of historical institutionalism, emphasise the role of time and history in the formation of institutions. They argue that decisions taken at one point in time can have lasting effects and can shape the future trajectory of an institution, a phenomenon often referred to as 'path dependence'. | |||

These features distinguish neo-institutionalism from previous institutionalist approaches and make it a key approach to understanding governance, politics and social behaviour in the contemporary world. | |||

Institutionalism, including neo-institutionalism, focuses more on the role of institutions as structures that determine the behaviour of actors and shape social and political outcomes. It is clearly distinct from behaviourism in several respects: | |||

* ''' | * The '''role of institutions''': In contrast to behaviourism, which focuses on individual behaviour and its influence on social and political systems, institutionalism emphasises the role of institutions. Institutions are seen as having an influence on the behaviour of individuals and groups, as well as on political and social outcomes. | ||

* '''Structure | * '''Structure and agency''': While behaviourism tends to focus on agency - the actions and decisions of individuals - institutionalism considers the structure of institutions to be paramount. Institutions are seen as defining the rules of the game and limiting the options available to actors. | ||

* ''' | * '''Stability versus change''': Behaviourism often focuses on change, seeking to explain how and why individual behaviour changes. Institutionalism, on the other hand, often focuses on stability, showing how institutions persist over time, even in the absence of popular support or economic performance. | ||

* ''' | * '''Individual versus contextual factors''': While behaviourism tends to focus on individual factors such as attitudes, beliefs and preferences, institutionalism focuses more on contextual factors, in particular the way in which institutions structure and influence behaviour. | ||

So while behaviourism and institutionalism are both important approaches to understanding politics and society, they focus on different aspects of these systems. | |||

Functionalism holds that institutions exist to perform certain functions or solve certain problems in a society. This perspective sees institutions as rational and effective solutions to problems facing society. Institutionalism, on the other hand, does not take this approach. It does not see institutions solely in terms of their functions or their effectiveness. It recognises that institutions have profound effects on society that go far beyond their intended functions or their effectiveness in solving specific problems. It focuses on how institutions shape the behaviour of individuals and groups, how they structure social and political interactions, and how they can produce outcomes that are neither intended nor necessarily desired. Furthermore, unlike functionalism, historical institutionalism recognises that institutions can often persist even when they are no longer effective or responsive to current problems. This is known as path dependency - the idea that past decisions or events have a lasting impact and shape future trajectories. In other words, once an institution is in place, it can be very difficult to change or remove it, even if it no longer fulfils its original function effectively. | |||

The functionalist perspective puts forward the idea that institutions are deliberately created and maintained because they have beneficial effects. For example, a legal system might be set up because it helps to resolve conflicts in an orderly fashion, or an education system might be set up because it promotes the development of the skills and knowledge needed in a society. Rational actors, seeking to solve these problems or achieve these goals, would therefore create these institutions because they recognise the functional benefits they bring. Historical institutionalism, however, emphasises that institutions are not always created in such a rational or far-sighted way. There may be historical factors, power relations, accidents or unforeseen events that play a major role in the creation and evolution of institutions. Institutions can also have effects that were not foreseen or intended, and these effects can in turn influence the way institutions develop and change over time. | |||

The general assumption in many economic and political models is that when institutions no longer adequately reflect the interests of actors, they are modified to return to an equilibrium. This is the idea of "rational choice" or "institutional equilibrium". However, historical institutionalism challenges this hypothesis. It points out that institutional change can be difficult and costly, and that there is often strong resistance to change. In addition, actors may not have a full understanding of their own interests or how institutions affect those interests, which can also hinder institutional change. Furthermore, even if institutions do change, they are not necessarily changed in a way that perfectly reflects the interests of stakeholders. On the contrary, institutional change may be the result of compromises, power struggles, complex historical processes, and so on. As a result, institutions may continue to have forms and functions that are not optimal from the point of view of efficiency or utility. Finally, historical institutionalism emphasises that institutions can have important effects on the interests and behaviour of actors. For example, they can influence the way actors perceive their interests, the way they interact with each other, the strategies they adopt, and so on. In this way, institutions and stakeholders are in constant interaction, each influencing the other in dynamic and often unpredictable ways. | |||

The idea of historical institutionalism is that institutions have their own 'inertia' and are often difficult to change. Even if they are no longer perfectly aligned with the interests of the actors, they can persist because of various factors, such as the costs of change, resistance from groups that benefit from the status quo, or simply the force of habit and tradition. Furthermore, historical institutionalism emphasises that institutions are not necessarily the result of a rational and deliberate process aimed at finding the best solution to a given problem. They may be the result of complex historical processes, interactions between different actors and interests, compromises, power struggles, accidents and so on. Institutions may therefore have forms and functions that are not necessarily optimal or even logical from the point of view of efficiency or utility. For example, a political or economic system may contain elements that seem irrational or inefficient, but which are the result of historical compromises between different social groups or the persistence of historical traditions. Institutions can also have unexpected or unintended effects that impact how they function and evolve. | |||

Historical institutionalism takes time into account when analysing institutions. It recognises that institutions are not static, but evolve over time, and that processes of institutional change can be long and complex. This long-term perspective makes it possible to take account of the unanticipated or unintended consequences of setting up an institution. For example, when actors set up an institution, they may not fully anticipate how it will affect their behaviour or interests in the future. They may also not anticipate how the institution will interact with other institutions or social, economic or political factors. Moreover, once an institution is in place, it may have 'institutional inertia', meaning that it may be difficult to change, even if actors realise that it is having unintended consequences. Therefore, historical institutionalism emphasises the importance of taking into account the long-term, unanticipated and unintended consequences of institutions. It also means that institutions may need to be reviewed and revised over time, as the interests of actors and social, economic and political conditions change. | |||

Bo Rothstein | Bo Rothstein in his 1992 work emphasises the influence of labour-market institutions on working-class strength, particularly in relation to union density.<ref>Rothstein, Bo. "Labor-market institutions and working-class strength." ''Structuring politics: Historical institutionalism in comparative analysis'' (1992): 33-56.</ref> The Ghent system, named after the Belgian town where it was first introduced, is a feature of some unemployment insurance systems. In the Ghent system, the trade unions play a central role in the administration of unemployment insurance benefits. In other words, it is the unions that administer the benefits for their members, rather than the state or a government agency. Ghent systems exist in several countries, including Sweden, Finland and Belgium. According to Rothstein, the Ghent system fosters a stronger working class because it encourages union membership. If the unions manage unemployment benefits, workers have an extra incentive to join a union. This can lead to higher rates of unionisation and, therefore, greater collective strength for the working class. This is a good example of how institutions - in this case, the unemployment insurance system - can influence behaviour and outcomes for specific groups of actors in society. | ||

It seems logical to assume that left-wing governments, generally favourable to workers' rights, would be more inclined to implement a Ghent system. However, it is important to note that the implementation of a Ghent system may depend on various factors, including the historical, political and social context, as well as the existing legal and economic system. Furthermore, adopting a de Ghent system may not be as straightforward as it seems. Firstly, it requires the trade unions to have the organisational capacity and financial resources to manage the unemployment insurance system effectively. Secondly, it requires the government to be prepared to hand over this responsibility to the unions. Finally, it should be noted that the introduction of a Ghent system may have unintended consequences. For example, it could potentially polarise the labour market between union and non-union workers, or it could give unions disproportionate power. In short, while the introduction of a Ghent system can theoretically strengthen the labour movement, its practical implementation can be more complex and dependent on many contextual factors. | |||

What emerges from Bo Rothstein's observation is that political and historical reality is often more complex than theoretical models might suggest. The motivations of governments to adopt certain policies can depend on many factors, including long-term strategic objectives, internal and external political pressures, and specific historical circumstances. In the case of France, the introduction of unemployment insurance by a liberal government could be explained by a desire to control the labour movement, rather than to strengthen it. Liberal governments may have seen the Ghent system as a way of channelling trade union activity into a more formal and controlled framework. It may also have been seen as a way of pacifying the labour movement by offering certain advantages, while retaining overall control over economic policy. The French unions, with their tradition of independence from the state, may have seen this manoeuvre as an attempt to co-opt them and so resisted. Consequently, the failure to introduce the Ghent system in France can be seen as a demonstration of how unanticipated consequences and the complex interplay of political interests can influence policy outcomes. | |||

In the long term, this was to be detrimental to working class power in France, where union density was one of the lowest in the private sector at less than 10%. The movement to create institutions in 1905 in France, for example, may have had short-term reasons for its decisions. Still, it was not an intentional act that accounted for long-term developments and institutions favourable to workers in the long term. The players are not always clear about what is advantageous for them. Political decisions are often taken in response to short-term considerations and do not always take account of the long-term consequences. This can be due to a multitude of factors, including immediate political pressures, strategic miscalculations, or simply a lack of understanding of the long-term implications of a given policy. | |||

In the case of France and the Ghent system, it seems that the decisions taken by the liberal governments and the reaction of the trade unions had unintended consequences which ultimately weakened the power of the working class. This is a perfect example of how unintended consequences and errors of judgement can have a major impact on a country's political and economic development. However, it is important to note that even if actors are not always clear about what is in their long-term interest, this does not necessarily mean that they are acting irrationally. On the contrary, they often do their best to navigate a complex and uncertain environment, relying on the information and resources available to them at any given time. This can sometimes lead to mistakes, but it is an inevitable part of the political process. | |||

The historical institutionalist approach emphasises that political and economic institutions have lasting and sometimes unforeseen effects that may not be immediately apparent when they are created. This is a major criticism of functionalist approaches, which generally consider that institutions are created to solve specific problems and evolve or disappear when they change or are solved. In contrast, historical institutionalism argues that institutions tend to persist over time, even when they no longer effectively address the problems for which they were originally created, due to power dynamics, transaction costs and other factors. Moreover, this perspective also emphasises that institutions are not always created rationally or with foresight. On the contrary, they may be the product of impulsive political decisions, complex trade-offs or even pure coincidence. These circumstances can lead to institutional outcomes that are very different from what the original actors would have intended or desired, thus underlining the importance of historical context and contingencies in forming institutions. | |||

== Path dependence == | == Path dependence == | ||

The idea of 'path dependence' is a central concept in historical institutionalism. It refers to the idea that past decisions and existing institutions can shape and constrain future choices. This is because, once an institution or policy has been put in place, it often creates expectations, norms and investments that make change costly and difficult. In the context of political and economic institutions, this means that even if an institution is no longer optimal, or no longer serves the interests it was originally intended to serve, it may persist simply because it is difficult to change the status quo. Political, economic and social actors can adapt to these institutions and build their strategies and expectations around them, making any change potentially disruptive and costly. | |||

The example of social security in the United States provides a good illustration of the concept of 'path dependence' in political science. | |||

In the United States, the social security system was introduced in the 1930s in response to the Great Depression. It was designed to provide a safety net for older workers by providing a basic retirement income. However, the system was designed in such a way that it relied heavily on contributions from current workers to fund the benefits of current retirees. Over time, the demographics of the United States have changed, with an increasing proportion of older people compared to younger workers. This has led to increasing financial pressures on the social security system. However, despite the challenges facing the system, it is extremely difficult to reform or change it significantly. This is due in part to the dependence of current and future beneficiaries on social security, but also to the complexity of the system itself. Attempts at reform have often met with considerable political and public opposition. So while the US social security system may no longer be the most efficient or equitable given current demographic and economic realities, it persists largely because of path dependence. Past decisions have created an institution that is now difficult to change, despite its obvious problems. | |||

=== William Sewell === | === William Sewell === | ||

In his article "Three Temporalities: Toward an Eventful Sociology", author William H. Sewell Jr. discusses the idea of path dependence.<ref>Sewell, "Three Temporalities," 262-263. For scholars who basically adopt this definition, see Barbara Geddes, "Paradigms and Sand Castles in Comparative Politics of Developing Areas," in William Crotty, editor. Politic~al Sc~ienc~e: Looking to the Future, vol. 2 (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press 1991). 59; Isaac. "Transforming Localities," 7: Terry Lynn Karl, Tl~eParadox of'Plentj~: Oil Booin.\ and Petro- state^ (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 11: Jill Quadagno and Stan J. Knapp. "Have Historical Sociologists Forsaken Theory?: Thoughts on the HistoryITheory Relationship." Sociologicirl Met11od.t irnd Rc~mrc,ll 20 (1992): 481--507; Somers. "We're No Angels." 768-769: Tilly. "Future History." 710.</ref> This notion suggests that past decisions, events or outcomes significantly impact future decisions, events or outcomes. | |||

According to Sewell, this path dependence is not simply a matter of past events limiting future options. He highlights the idea that these historical dependencies can also open up new possibilities and paths of action that were not previously considered. Moreover, these path dependencies are not simply linear or deterministic. Rather, they are multidimensional and complex, with multiple possible paths that can be followed at any given time. | |||

The key idea of path dependency is that historical structures and events matter. They shape future trajectories in significant ways. Decisions taken in the past continue to affect the options available in the present, and those past decisions can also impact the future unexpectedly. This is why it is important to consider historical processes when studying social phenomena. | |||

=== James Mahoney === | === James Mahoney === | ||

In the article "Path Dependence in Historical Sociology" published in 2000, James Mahoney defines path dependence as characterising specific historical sequences in which contingent events set in motion institutional patterns or event chains that have deterministic properties: "Path-dependence characterises specifically those historical sequences in which contingent events set in motion institutional patterns or event chains that have deterministic properties".<ref>http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3108585?uid=3737760&uid=2&uid=4&sid=21105163650823</ref> | |||

According to Mahoney, these contingent events, also known as critical or pivotal events, can have large-scale and lasting effects. These events trigger a sequence of chain reactions, leading to the establishment of new institutions or new patterns of behaviour which, once established, are difficult to change. | |||

The concept of 'path dependence' therefore suggests that it is often difficult to deviate from a path once it has been established, because the costs of doing so can be prohibitive. Moreover, even when circumstances change, the institutions and behaviours created by past events can remain in place. As a result, the history and specific sequence of events that occurred can have a profound and lasting impact on the future course of events. | |||

The concept of path dependence in historical sociology includes this idea of a pivotal moment, an initial event, sometimes called a 'tipping point' or 'critical point', which triggers a series of subsequent events. This pivotal moment may seem minor or insignificant at the time, but it can potentially trigger a cascade of mutually reinforcing events. Once this process has been triggered, it can become self-reinforcing and difficult to reverse, even if the original conditions that led to the initial event have changed. This is what is often referred to as "lock-in" in path dependency theory. Once established, it is a mechanism by which a certain structure remains in place and influences the future course of events, even if that structure is no longer optimal or efficient. The concept of path dependence therefore emphasises the importance of time and the sequence of events in determining institutional and social trajectories. | |||

=== Paul Pierson & Theda Skocpol === | === Paul Pierson & Theda Skocpol === | ||

The expression "dynamics of self-reinforcing or positive feedback processes in a political system" is used by Paul Pierson and Theda Skocpol in their article "Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science" published in 2002.<ref>Skocpol T, Pierson P. "Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science". In: Katznelson I, Milner HV Political Science: State of the Discipline. New York: W.W. Norton; 2002. pp. 693-721</ref> | |||

In this context, a self-reinforcing process refers to a situation where once an institution or policy is in place, it tends to reinforce itself through its effects and become increasingly resistant to change. This can happen for various reasons, such as the accumulation of resources, the learning and adaptation of actors, or the creation of new expectations and behavioural norms. | |||

Similarly, positive feedback is a process in which the effects of an action or decision increase the magnitude or probability of similar future events. In a political system, for example, a policy favouring a certain group may strengthen that group's power and increase the likelihood that it will support similar policies. | |||

These concepts are central to the historical neo-institutionalism approach to political science, which emphasises the role of institutions and historical processes in shaping political outcomes. | |||

== Lock-in effect == | == Lock-in effect == | ||

The lock-in effect is a concept derived from the path dependence approach in the social sciences. It refers to a situation in which, once a certain path or trajectory has been taken, it becomes increasingly difficult to go back or choose an alternative. This is due to the increasing costs associated with changing trajectory or abandoning the current path, such as the cost of abandoning previous investments, the cost of training in new practices or technologies, or the cost of resistance from players benefiting from the status quo. For example, in the field of technology, the concept of lock-in is often used to explain why a particular technology becomes dominant, even though other technologies may be technically superior. Once a technology has gained a certain market share, it can benefit from a network effect that strengthens its position and makes it difficult to switch to a competing technology. | |||

In the political or institutional context, lock-in can refer to the way in which previous decisions or policies make it difficult to change a certain status quo, even if that status quo is considered to be sub-optimal. This may be due to the accumulation of resources and power by the beneficiaries of the current situation, to the emergence of norms and behaviours that reinforce the status quo, or to the resistance of actors who fear losing out if change is made. | |||

Getting back on track with this choice, this chosen path, is also very difficult. This idea is central to the concept of path dependence in the social sciences. Once a certain path has been chosen in a social, political or economic system, it becomes increasingly difficult to modify or change it. Individuals and organisations adapt to the chosen path, investing time, money and resources to conform to it. They develop habits, skills and expectations that are aligned with this trajectory. This process reinforces the current trajectory and makes change increasingly costly and difficult. Individuals and organisations are increasingly reluctant to abandon the current trajectory because they have invested so many resources in conforming to it and because they anticipate the high costs of change. This is known as the lock-in effect. Moreover, the institutions themselves can reinforce the chosen path by putting in place rules and regulations that encourage compliance and discourage change. This creates a vicious circle that further reinforces the current trajectory and makes change even more difficult. This is why, in many cases, initial choices - even if they were contingent or based on imperfect information - can have long-term consequences that are difficult to reverse for the trajectory of a society, an economy or a political system. | |||

== Stickiness == | == Stickiness == | ||

In the historical institutionalist context, the term 'stickiness' refers to the way in which institutions tend to resist change, even in the face of new conditions or challenges. Institutions can be 'sticky' or 'persistent' in the sense that they tend to endure over time, and the structures and practices they put in place can have a lasting impact on society and continue to influence future developments. This does not necessarily mean that institutions are immutable or incapable of change. On the contrary, institutions can and often do change over time. However, this process of change can be slow, complex and non-linear, and institutions can often retain elements of their past form and function, even as they adapt to new conditions. This is what is meant by the term 'stickiness'. | |||

This is one of the central ideas of historical institutionalism. Institutions have an inertia of their own that enables them to resist change, even in the face of changes in the preferences of actors or in the balance of power between them. This can happen for several reasons: | |||

* | * Transition costs: Modifying an existing institution or creating a new one can entail significant costs, both in terms of material resources and time. These costs can dissuade stakeholders from seeking to change the institution, even if they would otherwise wish to do so. | ||

* | * Habits and expectations: Stakeholders have often become accustomed to an existing institution and have developed their strategies around it. Change can disrupt these strategies and create uncertainty, which can also dissuade stakeholders from seeking to change the institution. | ||

* | * Lock-in and path dependency effects: Once an institution is in place, it can create dynamics that make its existence more likely in the future. For example, an institution may create material interests that encourage certain actors to defend it, or it may shape beliefs and values in such a way that people regard it as legitimate or natural. | ||

It is for these reasons that institutions can resist change, even in the face of shifts in the interests of actors or in the balance of power. | |||

The concept of 'path dependence' in historical institutionalism supports the idea that even if the conditions that initially led to the establishment of an institution change, the institution itself can persist. | |||

The concept of 'path dependence' is crucial in historical institutionalism to explain why societies can follow stable historical trajectories over long periods of time, even in the absence of the original conditions that led to the establishment of these trajectories. There are several reasons why a society may find it difficult to change its trajectory: | |||

# Threshold effects: Once a certain institution or set of practices reaches a certain level of prevalence, it can become 'self-reinforcing' or 'self-stabilising'. For example, once a certain technology or social norm becomes widely adopted, it may become difficult to change simply because so many people use and depend on it. | |||

# Hysteresis: This is the phenomenon whereby the history of a system has an influence on its present state, even if the original conditions have changed. For example, past political or economic regimes can continue to influence political or economic culture long after they have disappeared. | |||

# Increasing returns: This is the phenomenon whereby the more an institution or practice is used, the more advantageous it becomes to use. This can create a "positive feedback loop" that reinforces and stabilises the institution or practice. | |||

Historical institutionalism, with its concept of 'path dependence', highlights the inertia inherent in political and social institutions. The choices made in the past have a decisive influence on the future trajectories of a society. Existing institutions create a structural framework for action, which guides individual and collective behaviour. These structures tend to be perpetuated over time, even in the face of new challenges or opportunities. This is partly because institutions are often built to be durable and resilient, and partly because they are embedded in wider systems of norms, values and practices that are mutually reinforcing. Furthermore, once a certain institutional path has been taken, it can be very costly, difficult or politically unacceptable to change course. This 'exit cost' can include not only financial costs, but also social costs, such as the disruption of established relationships, loss of legitimacy, or resistance from those who benefit from the status quo. This means that societies can face considerable difficulties in radically changing their trajectory. This is a reality that public policy and reform efforts must take into account. | |||

A clear example of how institutions structure socio-economic outcomes is between Sweden and the United States, which have very different institutional traditions when it comes to the labour market. In Sweden, the institutionalisation of the labour market is strongly influenced by the Nordic model, also known as the social democratic model. This model is characterised by a high level of social protection, strong trade union involvement, extensive regulation of the labour market and significant redistribution through the tax system and social benefits. These institutions help to limit inequality and provide a degree of economic security for workers. In the United States, on the other hand, the labour market is more liberal, with less regulation and a lower level of social protection. Trade unions have less influence and there is less redistribution through the tax system and social benefits. As a result, inequalities are higher and economic risk is borne more by individuals. These institutional differences are deeply rooted in the history and culture of each country, and they illustrate the idea of 'path dependence': past economic and social policy choices have created distinct trajectories that continue to influence current outcomes. | |||

Institutions cannot simply be transplanted from one country to another, as they are rooted in specific cultural, social, economic and historical contexts. Each country has its own path dependence, which is the result of past decisions and experiences. These experiences shape the expectations, norms and values that underpin its institutions. | |||

The United States and Sweden have very different values and social norms, as well as different political and economic histories, which have led to the adoption of very different institutional models. The citizens of each country have different expectations in terms of the role of the state, social solidarity, labour market regulation and so on. These expectations are rooted in their history and culture, and they influence which policies are politically viable and socially acceptable. | |||

Attempting to transplant institutions from one context to another without taking these differences into account could lead to unexpected or undesirable results. For example, the introduction of extensive Swedish-style social protection in the United States could meet with political and social resistance, given the traditional emphasis on individual autonomy, personal responsibility and the free market. To reduce inequalities, it is necessary to take into account the specificities of each country and to seek to adapt and improve existing institutions to reflect these specificities. This could involve, for example, strengthening worker protection, promoting lifelong learning, or reforming the tax system to make it more progressive. However, it is crucial to understand that institutional change is often a slow and complex process, requiring social and political consensus. | |||

Moments of institutional creation are often critical tipping points in the history of a country or organisation. These moments represent initial choices which, once made, can have lasting and profound effects, guiding future development along a specific path. The institutions established at these crucial moments can create what researchers call 'path dependency' - a phenomenon whereby initial choices strongly influence the options and opportunities available in the future. This path dependency can make it very difficult to change course or adopt new institutions or policies, even when circumstances have changed. This is why it is crucial to understand these moments of institution-building and how they shape future trajectories. This can help explain why certain countries or organisations take a particular direction, why it is so difficult to change direction, and how institutions can be designed or reformed to better respond to contemporary challenges. | |||

== Critical juncture == | == Critical juncture == | ||

"Critical junctures" in institutionalist theory are those key decision-making moments when significant choices are made that determine the direction of an institutional trajectory. These initial choices can have lasting and powerful effects on institutional development. In other words, a critical juncture is a period of significant change when the decisions taken have far-reaching and lasting consequences for the course of events. These are moments of great fluidity when institutional changes can be implemented that diverge from what existed previously. These 'critical junctures' can be triggered by a variety of factors, such as economic crises, wars, revolutions, significant political changes or other major events. Decisions taken during these periods often have a long-term impact, shaping the direction of politics, the economy and society for years or even decades to come. | |||

Critical junctures are often triggered by major crises or events that disrupt the existing order and create opportunities for significant institutional change. These crises can include events such as wars, revolutions, economic or political crises, natural disasters and so on. At such times, existing institutional structures may be challenged, modified or even dismantled. At the same time, new institutions can be created to meet the challenges posed by the crisis. In this way, critical junctures can mark the beginning of new trajectories of institutional development. It is also important to note that while these moments of crisis are often associated with significant change, the specific direction of these changes is often determined by a number of factors, including the interests and values of key actors, the nature of the crisis itself, and existing socio-economic and political conditions. | |||

The 2008 financial crisis led many researchers and political scientists to wonder whether it would mark a critical juncture in the global economy. The crisis revealed many flaws in the global financial system and highlighted the need for tighter regulation and better supervision of financial markets. In some cases, there have been significant changes. In the United States, for example, the financial crisis led to the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, which introduced major regulatory reforms in the financial sector. At international level, the crisis has also led to a strengthening of the role of the G20 as a forum for international economic cooperation. This has included efforts to improve global financial regulation and promote more stable and sustainable economic growth. However, many researchers and commentators have noted that, despite these changes, many fundamental aspects of the global financial system have remained largely unchanged. This may be due to the resistance of existing economic and political actors, the complexity of the global financial system and the lack of consensus on alternative solutions. Therefore, although the 2008 financial crisis has led to some changes, it remains to be seen whether it marks a true 'critical juncture' in the evolution of the global economy. | |||

Major events such as wars, revolutions or massive political changes can create 'critical junctures' or tipping points that radically transform the historical and institutional trajectories of countries. For example, after the Second World War, Germany underwent a major overhaul of its political and economic system, moving from a totalitarian regime to a liberal democracy with a market economy. This had a lasting impact on Germany's development in the decades that followed. Similarly, the Arab Spring, which began in 2010, led to significant political changes in many countries in the Middle East and North Africa. In some countries, such as Tunisia, this has led to a transition to a more open democracy, while in others, such as Syria and Libya, it has led to prolonged conflict and instability. These 'critical junctures' are often periods of intense change and uncertainty, but they can also offer opportunities for institutional reform and social change. However, as the historical institutionalist approach emphasises, the outcomes of these formative moments are strongly influenced by existing institutions and historical trajectories, and can often have unforeseen and long-lasting consequences. | |||

Historical institutionalism challenges approaches that seek to explain social and political phenomena on the basis of constant relationships between independent and dependent variables, often measured using regression analysis. In this type of approach, it is generally assumed that the relationship between two variables (for example, educational attainment and income, or the level of democracy and economic development) is constant across different contexts and time periods. However, historical institutionalists argue that these approaches often overlook the importance of the historical and institutional context in which these relationships occur. They argue that relationships between variables can be strongly influenced by contextual factors, such as existing institutions, cultural norms and historical trajectories. For example, the link between education and income can vary considerably depending on a country's education system, labour market and social policies. Similarly, the link between democracy and economic development can be influenced by many historical and institutional factors, such as colonial legacies, political regimes, natural resources and internal conflicts. By emphasising the role of historical and institutional context, historical institutionalism seeks to provide a more nuanced and richer analysis of social and political phenomena. | |||

Historical institutionalists argue that a country's institutional context - its rules, regulations, norms and structures - can strongly influence its historical course and socio-political outcomes. Institutions can define incentives, constraints and opportunities for actors, influencing their behaviour and choices. This is why historical institutionalists are often sceptical about attempts to generalise causal relationships between variables across different institutional contexts. They argue that what works in one institutional context may not work in another. Consequently, they advocate a more contextual and historically sensitive approach, which takes into account the institutional specificities of each country or group of countries. This can involve in-depth case studies, historical comparisons and analyses of how institutions and historical trajectories can influence social and political outcomes. From this perspective, the analysis of path dependence, critical junctures, lock-in effects and institutional stickiness are key concepts for understanding the dynamics of change and continuity in political and social life. | |||

In a country with strong labour market institutions that protect workers (such as some Western European countries), employers may find it more difficult to increase working hours in response to the pressure of international competition. Unions, collective agreements and labour regulations could limit their ability to do so. On the other hand, in a country with more flexible labour market institutions and less protection for workers (such as the United States), employers might have more scope to increase working hours in response to the same pressure from international competition. In both cases, labour market institutions influence the way in which local economic players respond to globalisation. It is not simply a question of economic costs and competitiveness, but also of standards, regulations and institutional structures. | |||

Trade unions, as institutions, can play a key role in determining the impact of globalisation on working conditions. In countries where unions are strong and influential, they may be able to resist increasing pressure for longer working hours, even in the face of increased international competition. They can negotiate better conditions for workers, including limits on working hours. Conversely, in countries where unions are weak or have limited influence, they may be less able to resist these pressures. As a result, workers in these countries may be more likely to see an increase in their working hours as economic globalisation intensifies. This demonstrates the importance of historical institutionalism, which focuses on the analysis of institutions such as trade unions, and how they influence responses to challenges such as economic globalisation. | |||

Economic relationships, such as that between foreign direct investment (FDI) and working time, are not uniform across time and space. They are strongly influenced by the specific institutional context of a country at a given time. For example, a country with a highly regulated system of labour relations and strong trade unions may be able to resist an increase in working hours despite an increase in FDI. In this context, institutions act as a moderator in the relationship between FDI and working time. On the other hand, in a country with weak trade unions and a less regulated labour market, an increase in FDI could lead to an increase in working hours. The institutions (or lack of them) in this context may not offer the same level of protection to workers. This is a perfect illustration of how a country's specific institutional context can influence economic and social outcomes. | |||

== | == Criticism of the explanatory principle of constant causes == | ||

The critique of the 'constant causes' approach by historical institutionalists is linked to the consideration of context. Historical institutionalist thinking argues that general explanations that apply uniformly to all contexts may miss important nuances. For historical institutionalism, context matters a great deal. Institutions are seen as shaped by history, and in turn shape individual and collective behaviours and development trajectories within a country or region. Consequently, the context in which an institution evolves is fundamental to understanding its role and impact. For example, in the field of public policy, a policy that works well in one country may not work in the same way in another, simply because of differences in the institutional context. This does not mean that the search for "constant causes" has no value. On the contrary, it can help us to identify general trends and develop theories. But historical institutionalists remind us that we also need to pay attention to the specific context and how this can influence outcomes. | |||

For Coser, social science, "on the basis of the substantive enlightenment... it is able to supply about the social structures in which we are enmeshed and which largely condition the course of our lives."<ref>Coser, Lewis A. "Presidential Address: Two Methods in Search of a Substance." ''American Sociological Review,'' vol. 40, no. 6, 1975, pp. 691-700. ''JSTOR'', <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.2307/2094174</nowiki>.</ref> Closer here emphasises the importance of sociology and the social sciences more generally as tools to help us understand the social structures that shape our lives. In other words, the value of the social sciences lies in their ability to shed light on the systems and structures in which we live and which greatly influence our daily lives. | |||

From this perspective, the social sciences should help us understand the institutions, relationships, power dynamics, ideologies, social norms and other key elements of our societies that influence our behaviour, opportunities and life experiences. Sociology, for example, can help us understand why some people or groups have more power than others, how social structures contribute to the reproduction of inequality, or how social norms influence our behaviour. Ultimately, Coser suggests that the measure of success for the social sciences should be the substantial insight they add to our understanding of the social world. This means paying constant attention to the analysis of our social structures and how they shape our lives. | |||

Historical institutionalism, which looks at how institutions and their histories shape political and economic trajectories, uses concepts such as 'institutional layering' and 'institutional conversion' to explain how institutions change and transform over time. | |||

* | * Institutional Layering: This term is used to describe the process by which new institutions or rules are added to existing institutions without necessarily eliminating or replacing old ones. It is a more gradual and cumulative process of institutional change. For example, in a health system, the introduction of a new public health insurance system does not necessarily eliminate existing private health care providers, but adds to them, creating an additional layer of institutions. | ||

* | * Institutional Conversion: This concept refers to a more radical process of change in which an existing institution is transformed into an institution of a very different nature. This can occur when institutional actors reinterpret or reallocate the resources, roles or rules of an institution to meet new demands or opportunities. For example, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) initially set up to provide emergency aid might be 'converted' into an institution focused on long-term development. | ||

Both concepts highlight the different ways in which institutions can evolve and change in response to new demands, opportunities or challenges. They recognise that institutional change is not always a process of complete replacement of one institution by another, but can often be a more gradual and complex process of adaptation and transformation. | |||

Historical Institutionalism distinguishes between institutional change and the role of institutions as an independent variable in explaining political and social outcomes. In this approach, institutions are not only independent variables that influence behaviour and outcomes, but also dependent variables that are themselves influenced by a number of social, political and economic factors. This means that Historical Institutionalism is concerned not only with how institutions shape behaviour and outcomes, but also with how institutions themselves change and evolve over time. | |||

For example, one might ask how a specific institution, such as a social security system, has evolved over time in response to changes in the economy or society. This would consider the institution as a dependent variable. On the other hand, we could ask how the same social security system has influenced individual behaviour or outcomes in terms of health and well-being. In this case, the institution would be considered as an independent variable. | |||

As for institutional layering and institutional conversion, these concepts are used to explain the different ways in which institutions can evolve and change. Institutional layering refers to the addition of new institutions or rules to existing institutions, while institutional conversion refers to the transformation of an existing institution into something radically different. Both concepts therefore recognise the possibility and reality of institutional change. | |||

Historical institutionalism recognises that institutions are not static but can evolve and change over time, often more gradually than radically. | |||

In institutional layering, new initiatives or procedures are added to the existing institution without completely replacing it. This can be seen as evolution rather than revolution, where changes are made gradually and in parallel with existing structures. In institutional conversion, existing institutions are reoriented towards new functions or objectives. Institutional structures remain, but their functions change, sometimes significantly. Interest group theory is also relevant to historical institutionalism. This theory highlights the role of conflicts between different social and economic groups in political dynamics. According to this theory, interest groups compete for limited resources, and political institutions are often the site of these struggles. | |||

Historical institutionalism, however, not only considers these conflicts, but also asks how they are structured and shaped by existing political institutions. Moreover, it is interested in how these institutional structures vary from country to country and over time. This reflects his attention both to the role of institutions as determinants of political behaviour and to the way in which they themselves are shaped and transformed. | |||

= Annexes = | = Annexes = | ||

Version actuelle datée du 7 juillet 2023 à 10:42