« The independence of the United States » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 119 : | Ligne 119 : | ||

The pamphlet also resonated with the population because of high literacy rate and it helped to rally support for the cause of independence. The ideas of Paine, along with the Continental Army's military successes, helped sustain the enthusiasm of the Second Continental Congress, who were meeting in Philadelphia as the British troops began to retreat and abandon the city of Boston. | The pamphlet also resonated with the population because of high literacy rate and it helped to rally support for the cause of independence. The ideas of Paine, along with the Continental Army's military successes, helped sustain the enthusiasm of the Second Continental Congress, who were meeting in Philadelphia as the British troops began to retreat and abandon the city of Boston. | ||

on July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution for independence, which was largely written by Thomas Jefferson. As it is known, the Declaration of Independence was adopted by all thirteen colonies, and it formally declared the colonies' separation from British rule. | |||

The Declaration states that "all men are created equal" and that they have certain inalienable rights, including "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." It asserts that governments are established to protect these rights and that when a government fails to do so, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it and to establish a new government. | |||

The Declaration's emphasis on individual rights, equality, and the consent of the governed was a radical departure from traditional notions of government and society. It would have a profound impact on the world. The ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independence would inspire political movements and revolutions around the world, and it would become one of the most important documents in history. | |||

There follows a long list of 23 attacks and violations of the rights of settlers by the King of England. All these accusations establish that he is basically a Tiran. It goes on to state that the Americans tried everything before responding to England by war to liberate themselves, and that is why "we, the representatives of the United States of America assembled in assembly taking as our witness the supreme judge of the universe, and on behalf of the people and their colonies, publish that the United Colonies are entitled to be free and independent states free from all allegiance to England. The colonies may make peace, enter into alliances, display commerce, and do all that an independent state can do; and in support of this declaration we affirm our allegiance to divine providence.<ref>Déclaration unanime des treize États unis d’Amérique réunis en Congrès le 4 juillet 1776</ref> ». | There follows a long list of 23 attacks and violations of the rights of settlers by the King of England. All these accusations establish that he is basically a Tiran. It goes on to state that the Americans tried everything before responding to England by war to liberate themselves, and that is why "we, the representatives of the United States of America assembled in assembly taking as our witness the supreme judge of the universe, and on behalf of the people and their colonies, publish that the United Colonies are entitled to be free and independent states free from all allegiance to England. The colonies may make peace, enter into alliances, display commerce, and do all that an independent state can do; and in support of this declaration we affirm our allegiance to divine providence.<ref>Déclaration unanime des treize États unis d’Amérique réunis en Congrès le 4 juillet 1776</ref> ». | ||

Version du 13 janvier 2023 à 14:18

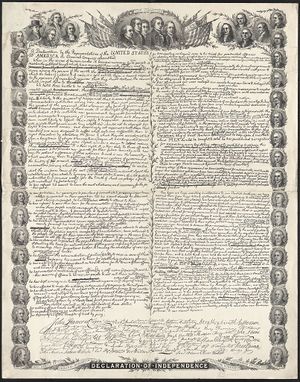

Fac-similé de la Déclaration d'indépendance américaine avec les portraits des signataires.

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The independence of the United States refers to the process by which the thirteen British colonies in North America declared their independence from the British Empire and became the United States of America. The Declaration of Independence, adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, proclaimed that the thirteen colonies were no longer subject to British rule and were now an independent nation.

It is important to understand that historical events result from complex interactions between multiple factors, both long-term structural elements and short-term conjunctural events. The Seven Years' War and the Enlightenment were both significant factors that contributed to the eventual independence of the United States. The Seven Years' War, also known as the French and Indian War, left Great Britain heavily in debt and led to increased taxes on the American colonies. This, combined with the ideas of the Enlightenment, which emphasized individual rights and freedoms, led to growing discontent among the colonists and ultimately to the American Revolution. Additionally, the British government's attempts to exert more control over the colonies, such as the Quartering Acts and the Proclamation of 1763, further contributed to the desire for independence.

Causes of Independence

The demographic growth and the expansion of the American colonies in the 18th century played a significant role in the eventual independence of the United States. The increased population, as a result of both high birth rates and immigration (the territory of the United States goes from 300,000 inhabitants in 1700 to 2.5 million in 1770), put pressure on the limited resources of the colonies and led to the development of distinct regional identities.

The Seven Years' War (1756 - 1763), also known as the French and Indian War in the United States, was another important factor that contributed to the independence of the United States. The British victory in the war led to the Treaty of Paris, which resulted in the transfer of French territory to the British, including the territories west of the Mississippi River. This change in colonization was made at the expense of the indigenous nations, which were weakened by the war. In addition, the newly acquired territory led to increased competition for land, resources and power between the colonies, the British Empire and the Indigenous Nations.

Additionally, the Treaty of Paris also led to the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade the colonies from settling beyond the Appalachian Mountains, further contributing to the colonists' resentment and anger towards the British Government. The Proclamation of 1763 was seen as a violation of the colonists’ rights to expand and expand their economic activities. All these factors contributed to the growing desire for independence among the colonists, ultimately leading to the American Revolution.

The end of the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), tensions between the colonies and the British government increased. The British government sought to control the colonists' access to Indian territories by signing treaties with Indian chiefs. Still, the settlers continued to encroach on Indian land by buying territories from the Cherokees and the Apaches.

The British government's attempts to raise revenue to pay off its war debt by imposing new taxes and stronger customs regulations were met with resistance from the colonists, who were used to a high degree of autonomy and decentralization. The imposition of the Stamp Act, a mail tax that was not decided by the colonial assemblies, was particularly contentious as it was seen as an attack on the colonists' system of representation, economic progress, and freedom.

The ideas of the Enlightenment, which emphasized individual rights and freedoms, also played a role in the resistance to British rule. Many of the educated men in the colonies echoed the ideas of Locke, who believed that the state's role was to bring welfare and security to individuals with inalienable rights to life, liberty and property. These ideas, along with the growing resentment towards British rule and the desire for greater autonomy, ultimately led to the American Revolution and the independence of the United States.

Response of the colonies

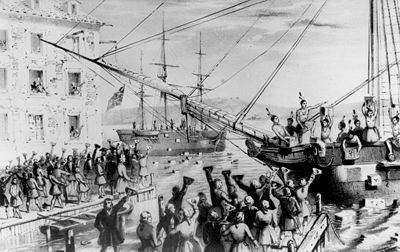

The colonies' response to the new taxes and regulations imposed by the British government was one of resistance and disobedience. The colonists petitioned against the taxes and refused to pay them, and launched boycotts of taxed products. They also used violence against British officers, such as in the "Boston Massacre" in 1770, where English soldiers killed five demonstrators. The "Boston Tea Party" in December 1773, where Bostonians disguised as Indians boarded an English ship carrying tea from the East India Company and threw the cargo of tea into the sea as a protest against the tea tax and the monopoly of the British East India Company over the American tea trade. These events were significant in escalating tensions between the colonies and the British government and ultimately contributed to the outbreak of the American Revolution.

The Boston Massacre was a confrontation on March 5, 1770, between a group of American colonists and British soldiers in Boston. The incident began as a street brawl between a small group of soldiers and a crowd of colonists who were taunting and throwing objects at the soldiers. The situation escalated and resulted in five colonists' deaths at the soldiers' hands. The event inflamed tensions between the colonists and the British government, and it was widely publicized in the colonies as an example of British tyranny. The Boston Tea Party was a political protest in Boston on December 16, 1773. A group of colonists, disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded three British ships anchored in Boston Harbor and threw 342 chests of tea into the harbour to protest against the Tea Act of 1773. The act had granted the British East India Company a monopoly on the tea trade in the colonies, and the colonists saw it as a violation of their rights as British citizens to be taxed without representation in the British Parliament. The Boston Tea Party was a significant event in the buildup to the American Revolution, as it united colonists across the colonies in resistance against British rule.

British reaction

London's reaction to the Boston Tea Party was to punish the colony of Massachusetts by imposing the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, in 1774. These acts were a series of laws passed by the British government in response to the Boston Tea Party. The Coercive Acts included:

- The Boston Port Act, blockaded and closed the port of Boston to all trade, cutting off the city's main source of income and livelihood.

- The Massachusetts Government Act, which imposed the King's authority over the Massachusetts colony, dissolved the colonial assembly so that the colonists no longer had any power to govern themselves.

- The Administration of Justice Act, which transferred to England trials that could lead to the death penalty, so that the colonists could not receive a fair trial.

- The Quartering Act, required the colonists to house and feed British troops in their own homes without compensation.

These acts were seen as a violation of the colonists' rights as British citizens and were deeply unpopular in the colonies. Nevertheless, they sparked widespread anger and resistance among the colonists, ultimately leading to the formation of the Continental Army, the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and the outbreak of the American Revolution.

Decisive steps towards independence

The Coercive Acts led to increased solidarity among the colonies, as they saw the punishment of Massachusetts as a threat to their own rights and freedoms. The colonies began to support each other through mutual aid and a growing sense of nationalism.

In September 1774, delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies met in the first Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where they declared the Coercive Acts to be illegal and invited the colonists to form defence militias. This congress marks a decisive step towards independence, as it was the first time that the colonies came together to take a unified stance against British rule.

However, it's important to note that not all American settlers favoured independence; many, known as Loyalists, continued to support the British government. While others protested and signed petitions but were not prepared to take up arms that would threaten their economic interests.

The actions of King George III, who was seen as unable to cope with the events, also contributed to the colonists' desire for independence. In addition, his inability to find a solution to the crisis and his support of the Coercive Acts and the Quartering Act further fueled the colonists' anger and desire to break free from British rule.

Most of the delegates and members of the Continental Congress were from the wealthiest families in the colonies and were primarily made up of merchants, lawyers, and a few craftsmen. These leaders were not necessarily revolutionaries but sought to overthrow the local hierarchy to regain their local power, which the Coercive Acts had threatened.

To gain the support of the broader population, they mobilized merchants, lawyers, skilled workers, artisans and taverns. They used these groups to spread their message and rally support for their cause. They also used various forms of propaganda, such as pamphlets and newspapers, to disseminate their ideas and gain public support for their cause.

It's important to note that the American Revolution was not a revolution of the lower classes, but rather a rebellion of the colonial elite, who sought to gain more power and autonomy from the British government. They were able to mobilize the broader population and gain support for their cause. Still, it was ultimately the actions and decisions of this colonial elite that led to the independence of the United States.

It was in 1775 that the settlers took up arms against the British, starting with the Battle of Lexington. This event, which saw British troops and American militiamen clash resulting in deaths, marked the beginning of the armed conflict between the colonies and the British government, and Massachusetts became known as the "cradle of independence."

In response to this, a Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, where the decision was made to form an army to defend the colonies against the British. This army, known as the Continental Army, was entrusted to George Washington, who would become the army's commander-in-chief and a key figure in the American Revolution. This marked a crucial step towards the colonies' independence, marking the beginning of organized military resistance against the British.

George Washington was chosen by the delegates of the Second Continental Congress to lead the Continental Army because he was seen as patriotic, committed, and a wealthy landowner from Virginia. His status as a wealthy plantation owner, including enslaving people, was seen as a sign of his financial independence and that he would not be swayed by personal gain. Additionally, his leadership experience from his military service during the French and Indian War also played a role in his selection as commander-in-chief.

The fact that he was from Virginia, and therefore from the South, also played a role in his selection as it was thought that this would help to expand the independence movement, which until that point had been primarily centred in the North. The idea was that by selecting a leader from the South, the union of the Thirteen Colonies would be more firmly established and more representative of the entire colonies.

The Declaration of Independence

Washington's task as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army was challenging, as many American settlers were not initially willing to enlist and risk their lives in a war against the British. One influential figure who helped to rally support for the cause was Thomas Paine, an Englishman who was a radical and a strong advocate for American independence.

Paine's influential pamphlet "Common Sense," published in 1776, argued that England's treatment of its colonies was predatory and that there was nothing left to negotiate with the British monarchy. Instead, he encouraged the colonists to focus on their own future as Americans and asserted that "the last link is now broken" between the colonies and Britain. Paine's pamphlet sold an estimated 120,000 copies, which was a large number given the population of the colonies at that time. It helped sustain the enthusiasm of the Second Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia.

The pamphlet also resonated with the population because of high literacy rate and it helped to rally support for the cause of independence. The ideas of Paine, along with the Continental Army's military successes, helped sustain the enthusiasm of the Second Continental Congress, who were meeting in Philadelphia as the British troops began to retreat and abandon the city of Boston.

on July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution for independence, which was largely written by Thomas Jefferson. As it is known, the Declaration of Independence was adopted by all thirteen colonies, and it formally declared the colonies' separation from British rule.

The Declaration states that "all men are created equal" and that they have certain inalienable rights, including "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." It asserts that governments are established to protect these rights and that when a government fails to do so, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it and to establish a new government.

The Declaration's emphasis on individual rights, equality, and the consent of the governed was a radical departure from traditional notions of government and society. It would have a profound impact on the world. The ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independence would inspire political movements and revolutions around the world, and it would become one of the most important documents in history.

There follows a long list of 23 attacks and violations of the rights of settlers by the King of England. All these accusations establish that he is basically a Tiran. It goes on to state that the Americans tried everything before responding to England by war to liberate themselves, and that is why "we, the representatives of the United States of America assembled in assembly taking as our witness the supreme judge of the universe, and on behalf of the people and their colonies, publish that the United Colonies are entitled to be free and independent states free from all allegiance to England. The colonies may make peace, enter into alliances, display commerce, and do all that an independent state can do; and in support of this declaration we affirm our allegiance to divine providence.[8] ».

This is the first time that men have used these ideas to justify the birth of a political entity.

First of all, it is a "men's affair"; women are totally absent, Indians are mentioned among the accusations against the king as "merciless savages" while slaves and slavery are never mentioned. The equality of men declared in the opening is reserved for adult white men.

Continuation of the war

The war will continue until 1781, often it will be guerrilla warfare. The American troops, led by Washington, will count between 4,000 and 7,000 men. England, on the other hand, would have up to 35,000 men, including a number from Russia.

The English make two appeals to the slaves to flee their masters and join the English troops against a promise of freedom. They will serve in the army, but mostly as labour, few will win their freedom at the end of the war.

The end of the war is accelerated by the entry of France on the side of the independentists. It is a help from the loyalist France of Louis XVI for a revenge on England. The aid arrived in 1780 with 6,000 men under the command of the Count de Rochambeau. Many of these men will come from Haiti and Santo Domingo.

French aid will be decisive in contributing to Britain's surrender after the Siege of Yorktown which meant England's capitulation leading to the recognition of American independence in September 1783 by a peace treaty in Paris.

From then on, the frontiers will continue to widen.

In fact, the war began in 1776 and ended in 1781 and England did not recognize independence until 1783. Compared to other independences, this is a rapid process.

Revolution or reaction?

In the United States, independence is called "the American Revolution". Not all historians agree with this, it's a debate that has been going on for two centuries.

For the proponents of the revolution thesis, this independence represents a radical break from the Americans in the monarchical context of the time because it was not only a reaction against the British Empire, but it destroys all ties with the traditional monarchy. The relationship between state and society is completely upset and projects the "United States".

For those who support a conservative reaction, what is at the root of all this is an attempt by Americans to restore the freedoms they had before, particularly the freedoms of trade; it would be a movement that would have sought to take back what existed.

Both interpretations are true.

In order to have a revolution, you have to:

- mass mobilization of the population;

- Fighting between different ideologies;

- Concrete struggle for power.

- a profound transformation of social and economic structures.

As far as the Thirteen Colonies of the United States are concerned, we have the first three points, but not really the fourth, whereas as far as Santo Domingo and Haiti are concerned, we have all these elements.

In the framework of the United States, mobilization is weak, on the other hand, at the end of the war there is no real upheaval in society and structures; it is the same people who continue to govern, while serfdom remains and explodes.

The fact remains that the new nation innovates in many ways:

- it is the first independent country in the Americas;

- the United States adopts a republican and federalist system;

- the idea of hereditary nobility is rejected.

However, this is far from a democracy, because for politicians, the people are the lower people, and democracy refers to disorder and violence.

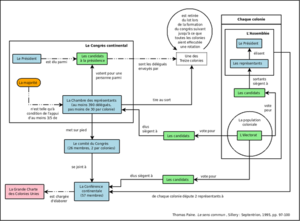

The delegates at the constitutional convention will face each other in the design of a legitimate government that must represent the will of the governed, including the key question of who will be able to vote.

This new country, calling itself the United States of America, appropriates the name America and soon becomes, for the inhabitants of these former colonies, "The America". It is an appropriation that is being made to the great displeasure of the Americans when they gain their independence.

Annexes

- Photographie interactive de la déclaration

- Site des Archives nationales américaines

- Bibliothèque Jeanne Hersche

- Hérodote.net

- Transatlantica, revue d'études américaines. Dossier spécial sur la Révolution, dirigé par Naomi Wulf.

- Nova Atlantis in Bibliotheca Augustana (Latin version of New Atlantis)

- Barnes, Ian, and Charles Royster. The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution (2000), maps and commentary excerpt and text search

- Blanco, Richard L.; Sanborn, Paul J. (1993). The American Revolution, 1775–1783: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-0824056230.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo III (1974). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (2 ed.). New York: Charles Scribners and Sons. ISBN 978-0684315133.

- Cappon, Lester J. Atlas of Early American History: The Revolutionary Era, 1760–1790 (1976)

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Richard A. Ryerson, eds. The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History (5 vol. 2006) 1000 entries by 150 experts, covering all topics

- Gray, Edward G., and Jane Kamensky, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution (2013) 672 pp; 33 essays by scholars

- Greene, Jack P. and J. R. Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2004), 777 pp – an expanded edition of Greene and Pole, eds. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (1994); comprehensive coverage of political and social themes and international dimension; thin on military

- Herrera, Ricardo A. "American War of Independence" Oxford Bibliographies (2017) annotated guide to major scholarly books and articles online

- Kennedy, Frances H. The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook (2014) A guide to 150 famous historical sites.

- Purcell, L. Edward. Who Was Who in the American Revolution (1993); 1500 short biographies

- Resch, John P., ed. Americans at War: Society, Culture and the Homefront vol 1 (2005), articles by scholars

- Symonds, Craig L. and William J. Clipson. A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution (1986) new diagrams of each battle

- Works by Thomas Paine

- Common Sense - Thomas Paine (ouvrage complet en anglais)

- Deistic and Religious Works of Thomas Paine

- The theological works of Thomas Paine

- The theological works of Thomas Paine to which are appended the profession of faith of a savoyard vicar by J.J. Rousseau

- Common Sense by Thomas Paine; HTML format, indexed by section

- Rights of Man

References

- ↑ Aline Helg - UNIGE

- ↑ Aline Helg - Academia.edu

- ↑ Aline Helg - Wikipedia

- ↑ Aline Helg - Afrocubaweb.com

- ↑ Aline Helg - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Aline Helg - Cairn.info

- ↑ Aline Helg - Google Scholar

- ↑ Déclaration unanime des treize États unis d’Amérique réunis en Congrès le 4 juillet 1776