The implementation of a law

Based on a course by Victor Monnier[1][2][3]

Introduction to the Law : Key Concepts and Definitions ● The State: Functions, Structures and Political Regimes ● The different branches of law ● The sources of law ● The great formative traditions of law ● The elements of the legal relationship ● The application of law ● The implementation of a law ● The evolution of Switzerland from its origins to the 20th century ● Switzerland's domestic legal framework ● Switzerland's state structure, political system and neutrality ● The evolution of international relations from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century ● The universal organizations ● European organisations and their relations with Switzerland ● Categories and generations of fundamental rights ● The origins of fundamental rights ● Declarations of rights at the end of the 18th century ● Towards the construction of a universal conception of fundamental rights in the 20th century

The action and jurisdiction

The effective application of the law in a society depends crucially on the interaction between legal action and the jurisdiction of the courts. Legal action is the process by which an individual or entity initiates legal proceedings to claim a right or remedy a wrong. Without this initiative, many rights would remain theoretical. For example, without legal action by environmental groups, important environmental protection laws might not be enforced.

Jurisdiction, on the other hand, refers to the power of a court to hear and decide a case. This authority is essential if legal action is to be effective. Take the example of a copyright dispute. If such a case is brought before a court that does not have the appropriate jurisdiction, copyright could not be effectively protected. When these two elements work together effectively, they form the basis of a strong legal system. The courts, by hearing actions and rendering decisions, play a central role in the application and interpretation of the law. These decisions, in turn, form the case law that guides the future application of the laws. For example, historical civil rights decisions in the United States have shaped the way in which equality laws are interpreted and applied today.

A critical aspect of this process is the enforcement of court decisions. A court decision loses its value if it is not effectively enforced. Take the case of a judgment for damages in favour of a victim of a road accident. If this decision is not enforced, the victim does not receive the compensation due, which calls into question the effectiveness of the law. Public perception of the fairness and effectiveness of the legal system also plays a major role in the application of the law. If citizens believe in the justice and fairness of the legal system, they are more inclined to respect the law and use the legal system to defend their rights. Conversely, a lack of confidence can lead to a reluctance to seek redress through legal channels, thereby weakening the application of the law.

Legal action plays a crucial role in the effective implementation of the law. This notion is based on the fundamental idea that the right really exists only when the holder of a right is able to enforce it with the help of the State or other authorities. In other words, a right, however formulated in the law, only has value if it can be actively asserted and defended by those to whom it is granted. In this context, the courts serve as essential mechanisms for sanctioning the right. When a person or entity is faced with a violation of their rights, they can turn to a court to obtain redress. For example, in a case of breach of contract, the right-holder may take the matter to a civil court to demand performance of contractual obligations or to obtain damages. This dynamic underlines the importance of access to justice. For rights to be truly effective, it is essential that individuals not only have knowledge of their rights, but also the practical ability to assert them before the relevant courts. This includes aspects such as the availability of courts, the affordability of legal costs, and an understanding of legal processes. The state plays a decisive role in this process. It is not just a question of legislating and creating rights, but also of putting in place an efficient and accessible judicial system capable of handling disputes and enforcing decisions. The existence of independent and fair judicial mechanisms is therefore a fundamental pillar of the rule of law.

The concept of jurisdiction is essential to the operation of the legal system. It represents the activity of the State which, through its judicial bodies, has the task of judging and dispensing justice by applying the law. This concept encompasses not only tribunals and courts, but also judges and other judicial actors who are mandated to resolve conflicts and enforce the law. Jurisdiction refers to the authority conferred on these judicial bodies to hear and decide cases. This authority may be determined by geographical criteria (the place where the dispute arose), by the nature of the dispute (such as civil, criminal or administrative cases), or by the level of jurisdiction (courts of first instance, appeal courts, etc.). The role of the judiciary in this process is crucial. As a pillar of democracy, the judiciary acts independently of other branches of government, such as the legislature and the executive. This independence is fundamental to ensuring fair and impartial justice. For example, in the event of a dispute between a citizen and the State, it is imperative that the court is able to judge the case without outside influence or pressure. The court, through its judging activity, contributes to the resolution of conflicts by applying laws and issuing decisions that are then implemented. This includes imposing penalties for criminal offences, resolving civil disputes by ruling on the rights and obligations of the parties, and reviewing administrative decisions.

The legal system offers a general right of action, a fundamental concept that ensures that any holder of a subjective right can take legal action to enforce that right or establish its existence. This right of action is a pillar of the rule of law and ensures that individual rights are not merely theoretical declarations, but real and enforceable prerogatives. In practice, this means that when a person or entity feels that their rights have been violated or disregarded, they can turn to the State's judicial bodies to seek redress or recognition. For example, in the case of a violation of property rights, the owner can take legal action to recover his or her property or obtain damages. Similarly, in matters of employment rights, an employee can go to an employment tribunal to assert his or her rights in the event of unfair dismissal or failure to comply with statutory working conditions. This general right of action is essential for several reasons. Firstly, it provides a concrete means for individuals to defend their rights and interests. Secondly, it helps to prevent abuses and illegal behaviour, given that such actions can be challenged in the courts. Finally, it strengthens confidence in the legal system and government, because it shows that rights can be enforced and that citizens have a remedy if those rights are violated. Thus, the right of action is an essential feature of any functional legal system, reflecting the state's ability and willingness to support and enforce the rights of its citizens.

In the legal field, the classification of legal actions into civil, criminal and administrative categories reflects the diversity and complexity of the conflicts and disputes that can arise in a society. Each type of action meets specific needs in terms of resolving disputes and maintaining social and legal order. Civil actions are those where individuals, businesses or other entities clash over issues such as contractual disputes, personal injury claims or property disputes. For example, if one person suffers loss as a result of the negligence of another, they may bring a civil action to recover damages. Similarly, in the event of a contractual dispute, the parties involved may resort to a civil court to resolve the dispute. The emphasis in civil actions is on redressing the harm suffered, often through financial compensation. Criminal actions, on the other hand, concern cases where the state takes action against an individual or entity for behaviour considered harmful to society. For example, in the case of theft or assault, it is the state, through the public prosecutor, that prosecutes the alleged offender. Criminal sanctions may include imprisonment, fines or community service, and are designed to punish and deter criminal behaviour, while protecting the community. Administrative actions often involve disputes between citizens or businesses and government authorities. These actions may be brought, for example, by individuals challenging decisions on building permits, environmental regulations or tax issues. Administrative actions are used to challenge the legality or correctness of decisions taken by government agencies and to ensure that these decisions respect the law and the rights of citizens. The existence of these different categories of legal action is a manifestation of the way in which the legal system adapts to the many facets of life in society. They offer a variety of ways of seeking justice, whether in the private sphere, in relations with the State, or in the context of protecting public order and social interests. This diversification of legal actions is crucial if we are to respond adequately and fairly to different types of conflict and ensure a balance between individual rights and collective needs.

Alternative dispute resolution

An important feature of the modern legal system is the possibility of having recourse to different jurisdictions other than those of the State. These alternative jurisdictions offer additional options for resolving disputes, without undermining the authority or legitimacy of the state judge. One notable example of an alternative jurisdiction is arbitration. In arbitration, the parties to a dispute agree to submit their dispute to one or more arbitrators, whose decision is generally binding. This mechanism is often used in international commercial disputes, where the parties prefer a more flexible and faster procedure than that offered by the traditional courts. Arbitration is particularly appreciated for its confidentiality, specialised expertise and ability to cross national jurisdictional boundaries. Another form of alternative jurisdiction is mediation. Unlike arbitration and court proceedings, mediation is a more collaborative method, where a mediator helps the parties reach a mutually satisfactory agreement. Mediation is often used in family disputes, such as divorce, where a less confrontational approach is desired.

These alternative jurisdictions do not seek to replace the state courts, but rather to offer complementary ways of resolving disputes. Indeed, they can lighten the load of traditional courts and provide more appropriate solutions to certain types of conflict. What's more, decisions reached through arbitration or mediation can often be enforced by state courts, demonstrating a certain harmony and complementarity between these systems. The existence of these alternative jurisdictions illustrates the diversity and adaptability of the legal system to meet the varied needs of society. They operate in tandem with the state courts, reinforcing the overall legal framework and offering litigants a wider range of options for resolving their disputes.

Although alternative jurisdictions such as arbitration and mediation offer complementary options for resolving disputes, their use is often conditional on the authorisation or legal framework established by the State. This regulation ensures coherent interaction between alternative jurisdictions and state courts, while guaranteeing the protection of fundamental rights and compliance with legal standards. In the field of private law, for example, the parties to a commercial contract may include an arbitration clause stipulating that any dispute arising from the contract will be submitted to arbitration rather than to the ordinary courts. However, this stipulation must comply with national laws governing arbitration, which define the criteria and conditions under which arbitration is authorised and recognised by the State.

In public law, particularly in disputes involving government entities, the use of arbitration or mediation can be more complex and is often limited by considerations of sovereignty and public interest. For example, certain disputes involving the State or its agencies may not be eligible for arbitration, due to the need to protect public interests and to comply with established administrative procedures. In international law, arbitration plays a significant role, particularly in resolving cross-border commercial disputes or disputes between investors and states. International conventions, such as the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, facilitate the use and enforcement of arbitration awards across national borders. However, even in this context, states retain control over the application of international arbitration through their national legislation. Thus, although alternative jurisdictions enrich the legal landscape and offer specific advantages, their implementation remains governed by state law. This regulation is crucial to ensure the fairness, legitimacy and effectiveness of these alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, while preserving the established legal order and the protection of fundamental rights.

Negotiations and talks

Negotiation plays a crucial role in public international law. It is a method of conflict resolution in which the parties involved engage in direct dialogue to resolve their differences. This approach is particularly relevant in international relations, where states and international organisations often seek to resolve their differences by diplomatic means rather than through litigation.

In negotiation, representatives of the conflicting parties meet to discuss the issues in dispute, explore possible compromises and reach a mutually acceptable agreement. This process can cover a wide range of subjects, from territorial disputes and trade agreements to environmental issues and peace treaties. The advantage of negotiation in international law lies in its flexibility and its ability to produce tailor-made solutions that take account of the specific interests of all the parties involved. Unlike arbitration or litigation, where a third party (such as a court or arbitrator) imposes a decision, negotiation allows the parties to control the process and the outcome.

A notable example of the successful use of negotiation is diplomacy leading to international agreements, such as arms control treaties or climate change agreements. In these cases, state representatives negotiate the terms of the agreement, seeking to balance their own national interests with those of other nations and the international community as a whole. However, negotiation requires the willingness of the parties to engage in dialogue and compromise, which is not always present. In addition, power imbalances between the parties can affect the negotiation process and outcome. Despite these challenges, negotiation remains an essential tool in the field of public international law for managing relations between states in a peaceful and constructive manner.

In international negotiations, the use of a third party to act as "good offices" is a common and often beneficial practice. This third party, usually a state, an international organisation or sometimes an individual with a reputation for experience and impartiality, acts as a facilitator to help the parties in conflict to engage in dialogue and find common ground. The role of this third party in good offices is distinct from that of a mediator or arbitrator. Rather than participating directly in negotiations or proposing solutions, the third party offering good offices focuses on creating an environment conducive to discussion. This may involve organising meetings between the parties, providing a neutral space for discussions, or offering logistical resources. The intervention of a third party through good offices is particularly useful in situations where relations between the parties are strained or where direct communication is difficult. By simply facilitating the negotiation process, without getting involved in the content of the discussions, the third party helps to re-establish or maintain open channels of communication, which is essential for reaching an agreement.

Historical examples of the use of good offices include situations where a neutral country or international organisation has helped to facilitate peace talks between nations in conflict. For example, a third country may offer its capital as a meeting place for peace talks, or an international organisation may provide technical assistance for the negotiation process. By providing a neutral framework and facilitating dialogue, good offices play an important role in the peaceful resolution of international conflicts. They enable the parties to overcome obstacles to communication and to work together more constructively to resolve their differences.

Good offices" represent a form of intermediation in which a third country, or sometimes an international organisation, plays a facilitating role to help two parties in conflict to negotiate under optimum conditions. The concept of good offices is distinct from mediation or arbitration, as the third party does not intervene directly in the content of the negotiations. Rather, their role is to create an environment conducive to dialogue and conflict resolution. In the context of good offices, the third country or organisation offering its services generally acts by providing a neutral venue for talks, helping to establish channels of communication between the parties, and offering logistical resources or technical assistance. The aim is to reduce tensions and facilitate a calmer and more constructive negotiation process. An important aspect of Good Offices is that the parties to the conflict retain full control over the negotiations. They are free to define the terms of the discussion, to choose the subjects to be addressed and to decide on the agreements to be reached. The role of the country or organisation providing the good offices is to support this process without directly influencing it. This approach is particularly useful in situations where the parties are unable or unwilling to engage in direct dialogue because of tensions or mistrust. Good offices can help overcome these obstacles by providing a neutral framework and logistical support, thereby encouraging more constructive engagement. Historically, the use of good offices has been crucial in many diplomatic contexts, particularly in peace negotiations or international agreements. For example, a neutral country can host peace talks between two conflicting nations, facilitating discussions without taking part in the content of the negotiations.

Switzerland is recognised for its traditional role in providing good offices, particularly in situations of international crisis. Its history of neutrality and its reputation as an impartial mediator have enabled it to play this facilitating role in several international conflicts. One notable example of Switzerland's use of good offices concerns its relations with Cuba. During the Cold War, Switzerland acted as an intermediary between Cuba and the United States. After diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba broke down in 1961, Switzerland agreed to represent American interests in Cuba, assuming the role of a protective power. In this capacity, Switzerland facilitated communication between the two countries, which was particularly crucial during periods of high tension, such as the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. As a protecting power, Switzerland was not involved in the content of discussions between the United States and Cuba, but it provided an essential channel of communication that enabled both sides to maintain a dialogue, even in the absence of formal diplomatic relations. This role was maintained for several decades, until the resumption of relations between the United States and Cuba in 2015. The case of Switzerland and Cuba is a good example of how a third country, through its neutral position and commitment to diplomacy, can make a significant contribution to easing international tensions and facilitating communication between countries in conflict. This Swiss tradition of providing good offices continues to play an important role in world diplomacy, offering a valuable avenue for the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

Mediation

Mediation is a conflict resolution process in which disputing parties rely on a mediator to facilitate discussions and propose solutions. The mediator, often chosen for his or her expertise, impartiality and prestige, plays a crucial role in helping the parties to explore options for resolution and to understand each other's points of view. Unlike a judge or arbitrator, the mediator does not have the power to impose a solution. Rather, their role is to guide the parties towards a mutually acceptable agreement. He helps to clarify the issues in dispute, identifies common interests, and encourages the parties to find common ground. The mediator may propose solutions, but it is up to the parties to decide whether to accept or reject these proposals.

The advantage of mediation lies in its flexibility and non-confrontational nature. As the parties have direct control over the outcome of the negotiations, they are often more inclined to adhere to the final agreement. In addition, mediation makes it possible to preserve or even improve relations between the parties, which is particularly important in contexts where they need to continue interacting after the dispute has been resolved, such as in family or commercial cases. Mediation is used in a variety of contexts, including commercial disputes, employment disputes, family disputes, and even in some cases of international diplomacy. For example, in the context of a divorce, a mediator can help a couple reach agreement on issues such as child custody or the division of property, without going through a potentially lengthy and costly trial.

Mediation is a dispute resolution tool that finds application in both private and international law, offering a flexible and often more collaborative approach to resolving disputes. In the context of private law, mediation is frequently used to resolve employment disputes, family disputes and other disputes between private parties. For example, in employment disputes, a mediator can help resolve disputes between employers and employees or between unions and management, often by finding common ground that avoids the costs and publicity of a trial. Similarly, in family disputes, such as divorces or child custody disputes, mediation helps parties reach agreements on sensitive issues in a less confrontational and more personalised way than litigation. In the field of international law, mediation is also a valuable tool, especially in resolving conflicts between states or disputes involving international actors. Mediators in these cases may be third-party states, international organisations or individuals with recognised expertise and authority. International mediation aims to find diplomatic and peaceful solutions to conflicts that could otherwise have serious consequences, ranging from political tensions to armed conflict.

The advantage of mediation in all these contexts lies in its ability to offer tailor-made solutions that take into account the specific interests and needs of the parties. It also fosters communication and mutual understanding, which can be crucial to maintaining ongoing relationships or ensuring lasting peace in the case of international conflicts. Mediation is therefore a versatile and effective method of conflict resolution, adaptable to a multitude of situations, whether they involve private or international law.

The conciliation

Conciliation is a dispute resolution process that aims to bring disputing parties together to find an amicable solution. The term "amicable" is derived from the Latin word "amicabilis", which means "capable of being resolved by friends" or "in a friendly manner". In the legal context, the word "amicable" emphasises the cooperative, non-confrontational aspect of dispute resolution. In a conciliation process, a conciliator, who is often neutral, helps the parties to discuss their differences and find a mutually acceptable solution on their own. Unlike a mediator, the conciliator's role can sometimes be more active in proposing solutions. However, as in mediation, the final decision always rests with the parties, and the conciliator has no power to impose an agreement.

Conciliation is particularly valued in situations where maintaining or restoring good relations between the parties is important. It is frequently used in contexts such as commercial disputes, labour disputes and family disputes. For example, in a business, a conciliator can help resolve a dispute between an employer and an employee, finding an agreement that meets the needs of both parties without resorting to a formal trial. The term "amicable" reflects the essence of conciliation: finding a resolution in a spirit of cooperation and mutual understanding, rather than through litigation. This often helps to preserve positive relationships and to find more creative and personalised solutions to problems.

Conciliation refers to a method of conflict resolution in which a solution is negotiated between the parties, with the help of a conciliator, often in a less formal setting and less strictly bound by precise legal rules. The main aim of conciliation is to reach an amicable agreement, rather than to determine who is 'right' or 'wrong' according to strict law. In this process, the conciliator (who may sometimes be a judge in some legal systems) plays the role of facilitator. Rather than deciding the dispute as a judge would in a trial, the conciliator helps the parties to explore the possibilities of agreement and to understand each other's perspectives and interests. The idea is to encourage the parties themselves to find a mutually acceptable solution.

This approach is particularly useful in situations where the parties need to maintain an ongoing relationship after the dispute has been resolved, such as in family or commercial cases. By enabling a more flexible and less confrontational resolution, conciliation helps to preserve relationships and often to find solutions that are better suited to the specific needs of the parties. One of the advantages of conciliation is that it allows aspects of a dispute that are not strictly legal to be addressed. For example, emotional, relational or practical considerations can be integrated into the negotiation, which would not be possible in a more formal legal framework.

Conciliation, as a preliminary measure in dispute resolution, is often encouraged, and sometimes even required, in certain legal systems, particularly in the area of family law. When a judge is seized of a dispute, particularly in sensitive cases such as divorce, child custody or inheritance disputes, he or she may first try to guide the parties towards an amicable solution before initiating formal legal proceedings. This approach reflects the recognition that, in many cases, a negotiated and consensual resolution may be more beneficial to all parties involved, especially where personal relationships are at stake. Conciliation not only resolves the current dispute, but also preserves and even improves future relationships between the parties, which is crucial in contexts such as family law. However, it is important to stress that acceptance of the solution proposed in conciliation depends entirely on the will of the parties. The judge or conciliator can facilitate discussion and encourage the parties to find common ground, but cannot force them to accept an agreement. The parties retain their autonomy and have the right to refuse the conciliation solution if they feel it does not meet their interests or needs. In some legal systems, conciliation may be a mandatory step before legal proceedings can be commenced. This obligation is intended to reduce the number of disputes that reach the courts and to encourage a quicker and less confrontational resolution of disputes. However, if the parties fail to reach an agreement through conciliation, they retain the right to have their dispute decided by a judge.

Arbitration

Arbitration is a method of dispute resolution in which one or more arbitrators, chosen by the disputing parties, are responsible for settling the dispute. This process differs from traditional legal proceedings in a number of respects, including the ability of the parties to choose their arbitrators, which is a major advantage of arbitration. In arbitration, the parties agree, often through an arbitration clause in a contract or through an arbitration agreement after the dispute has arisen, to submit their dispute to one or more specifically appointed arbitrators. These arbitrators may be experts in the field involved in the dispute, offering technical expertise that traditional judges may not possess. A crucial aspect of arbitration is that the decision made by the arbitrators, known as the award, is generally final and binding on the parties. This award has a legal force similar to that of a court decision and, in most jurisdictions, can be enforced in the same way as a court judgment.

Arbitration is particularly popular in international commercial disputes, as it offers several advantages over traditional state courts. These advantages include confidentiality, speed, flexibility of procedures, and the possibility for parties to choose arbitrators with specific expertise relevant to their dispute. In addition, due to international conventions such as the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, arbitral awards are more easily recognised and enforced internationally than judgments of national courts. However, it is important to note that, unlike judicial processes where the judge is assigned by the legal system, arbitration relies on the agreement of the parties for the selection of the arbitrators, which underlines the importance of mutual consent in this process. By allowing the parties to choose their "judge", arbitration offers a degree of personalisation and specialisation that is often not possible in ordinary court proceedings.

Arbitration, as a method of dispute resolution, can be established well in advance of the emergence of a specific dispute through the use of an arbitration clause in a contract. This clause is an anticipatory provision which stipulates that, in the event of a dispute arising out of the contract, the parties undertake to resolve it by arbitration rather than by the ordinary courts. This practice is common in many types of contracts, particularly international commercial agreements, where it is favoured for its ability to provide a more predictable and specialised dispute resolution.

The inclusion of an arbitration clause in a contract demonstrates careful planning on the part of the parties. By anticipating the possibility of future disagreements, the parties seek to ensure a method of resolution that is effective and tailored to their specific needs. This approach is particularly useful in complex areas such as international trade, where disputes may require specific expertise and the parties wish to avoid the uncertainties associated with different national legal systems. For example, in an international construction contract, an arbitration clause could stipulate that any dispute relating to the interpretation of the contract or the performance of the work will be resolved by arbitrators specialising in construction law and the relevant international standards. This specificity ensures that the arbitrators chosen will have the necessary expertise to understand and settle the dispute effectively. The existence of an arbitration clause also reflects the parties' mutual consent to alternative dispute resolution. This preference for arbitration shows a desire to maintain a degree of control over the dispute resolution process, while benefiting from a more personalised and potentially less confrontational approach.

Ad hoc arbitration is a form of arbitration that is applied specifically to a particular case, after a dispute has arisen. In this type of arbitration, unlike arbitration under an arbitration clause in a contract, the parties decide to opt for arbitration as a dispute resolution method only after the dispute has arisen. In such a situation, the disputing parties mutually agree to submit their dispute to ad hoc arbitration. They must then agree on a number of important aspects of the arbitration process, such as the choice of arbitrators, the rules of procedure to be followed, the place of arbitration and the language in which the arbitration will be conducted. This flexibility allows the parties to tailor the arbitration process to the specifics of their dispute, which can be a considerable advantage. For example, in a commercial dispute arising after the conclusion of an agreement without a prior arbitration clause, the companies involved may choose to use ad hoc arbitration to resolve the problem. They may decide to appoint a panel of arbitrators made up of experts in their specific business sector, thus establishing a tailor-made process that meets their particular needs. Ad hoc arbitration is often perceived as being more flexible than institutional arbitration, which follows the pre-established rules of a specific arbitration institution. However, this flexibility can also lead to additional complexities, particularly with regard to the organisation and management of the arbitration process. The parties must therefore be careful and clear when establishing the terms of the ad hoc arbitration to avoid complications later on.

An arbitration agreement is an agreement between the parties involved in a dispute that has already arisen, deciding to submit that specific dispute to arbitration. This type of agreement differs from an arbitration clause, which is drawn up before a dispute arises and included in a contract. An arbitration agreement, on the other hand, is an ad hoc agreement, drawn up specifically to settle an existing dispute. In an arbitration agreement, the parties define precisely the subject matter of the dispute to be submitted to arbitration and agree on the specific terms of the arbitration, such as the number of arbitrators, the procedure to be followed, the place of arbitration, and sometimes the law applicable to the dispute. This agreement is usually contractual and must be carefully drafted to ensure that all relevant aspects of the dispute and the arbitration process are clearly defined.

The advantage of an arbitration agreement lies in its ability to offer a tailor-made solution for a specific dispute, allowing the parties to choose a process that meets their particular needs. For example, if two companies are disputing the quality of goods delivered, they may decide to use an arbitration agreement to resolve the dispute, choosing arbitrators with expertise in international trade and product quality. Compromise arbitration is often chosen for its advantages such as confidentiality, speed and flexibility, as well as for the possibility of obtaining specific expertise through the arbitrators. In addition, as arbitration awards are generally final and enforceable, the parties can resolve their dispute efficiently and conclusively.

Arbitration has become an increasingly favoured means of resolving disputes, particularly in the field of international law and in the corporate sphere. Its growing popularity is attributable to a number of advantages it offers over traditional legal proceedings. In the international context, arbitration is particularly appreciated for its neutrality. Parties from different backgrounds can avoid submitting to the jurisdiction of the other party's national courts, which may be perceived as an advantage or an apprehension of bias. In addition, international arbitration overcomes language barriers and differences in legal systems, providing a more consistent and predictable framework for resolving disputes.

In the business world, and more particularly in international commercial contracts, arbitration is favoured for a number of reasons. Its procedure is generally simpler, faster and more discreet than that of the ordinary courts. Confidentiality is a major advantage of arbitration, enabling companies to resolve their disputes without attracting public attention or exposing sensitive business details. This discretion is essential to preserve commercial relations and the reputation of companies. Indeed, it is estimated that up to 80% of international commercial contracts include an arbitration clause, testifying to the strong preference for arbitration in international trade. These clauses enable the parties to agree in advance on arbitration as a means of resolving disputes, thereby guaranteeing a more controlled and predictable process.

As for the organisation of arbitration, many Chambers of Commerce throughout Europe and the world have set up their own arbitration institutions. These institutions provide frameworks and rules for arbitration, contributing to its standardisation and efficiency. Notable examples include the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), which are widely recognised and used in international commercial disputes. Arbitration has thus firmly established itself as a crucial tool in the resolution of disputes in international law and the business world, offering an efficient, flexible and discreet alternative to traditional court systems.

One of the distinctive and attractive features of arbitration, particularly in commercial disputes, is the possibility for the parties to choose arbitrators with specific expertise and experience in the field concerned. This contrasts with the traditional court system, where judges are assigned to cases without the parties having any direct control over their selection or specific expertise. In commercial arbitration, the parties enjoy the flexibility of selecting arbitrators who possess not only legal knowledge, but also an in-depth understanding of the specific industry or sector of activity related to the dispute. This practical expertise is particularly valuable in complex cases where technical knowledge or an in-depth understanding of business practices is essential to assess the issues in dispute and make informed decisions. For example, in a dispute involving technical issues relating to construction, the parties may choose to include individuals with engineering or construction experience on their panel of arbitrators. Similarly, in a dispute involving international financial transactions, the parties may prefer arbitrators with expertise in finance or international business law. This ability to choose arbitrators with relevant expertise offers several advantages. It ensures that decision-makers understand the nuances of the dispute and are better equipped to assess the technical or specialist arguments presented. In addition, it can lead to a more efficient resolution of the dispute, as competent arbitrators are likely to identify key issues more quickly and propose appropriate solutions.

The Alabama arbitration is a famous case in the history of international arbitration and played an important role in the development of international law. The case dates back to 15 September 1872, when Great Britain was ordered to pay substantial compensation to the United States for breaching its neutrality obligations during the American Civil War.

During this war, Great Britain, which had officially adopted a position of neutrality, had allowed warships, including the CSS Alabama, to be built and delivered to Confederate (Southern) forces from its shipyards. These ships were then used by the Confederates to attack the Union (Northern) merchant marine, causing considerable damage. The United States argued that these actions violated British neutrality and demanded reparations for the damage caused by these ships, particularly the Alabama. After the end of the war, to avoid an escalation of tensions and a possible military confrontation, the two nations agreed to submit the dispute to an international arbitration tribunal in Geneva, Switzerland. The arbitration tribunal, composed of representatives of several nations, concluded that Great Britain had been negligent in its duty of neutrality by allowing the construction and delivery of these ships to the Confederates. As a result, Great Britain was ordered to pay significant compensation to the United States. The importance of the Alabama arbitration lies in its impact on international law and the peaceful resolution of international disputes. Not only did the case contribute to the normalisation of arbitration as a means of resolving international disputes, it also strengthened Geneva's position as an important centre for diplomacy and international law. Moreover, this event marked a turning point in the recognition of the importance of the laws of neutrality and influenced the subsequent development of international conventions and treaties relating to the rights and duties of neutral nations.

The parties at the trial

In a civil lawsuit, the role and dynamics between the parties involved, i.e. the plaintiff and the defendant, are crucial to the progress and outcome of the case. The plaintiff is the party who initiates the legal proceedings. This initiative is generally motivated by a feeling of having suffered a loss or a violation of rights, thus prompting the plaintiff to seek some form of redress or justice from the legal system. For example, in a contractual dispute, the claimant might be a company suing a business partner for breach of contractual terms. On the other hand, the defendant is the party against whom the legal claim is made. This implies that he is supposed to have caused harm or violated the rights of the plaintiff. The defendant's role in a civil lawsuit is to respond to the accusations made against him. This response can take several forms, such as disputing the facts alleged by the plaintiff, presenting a different version of events, or advancing legal arguments to refute the plaintiff's claim. Take the example of a property dispute: the defendant could be a landlord accused by a tenant of failing to comply with the terms of the lease.

The court process provides a platform where these two parties can present their arguments, evidence and possibly testimony, either in writing or orally at hearings. This ensures that both sides of a dispute are heard and assessed fairly by a judge or panel of judges, depending on the legal system in place. After considering all the information and arguments presented, the judge makes a decision that settles the dispute. This structure of the civil trial, with clearly defined roles for the plaintiff and defendant, is designed to ensure that each case is dealt with fairly and impartially, thereby promoting justice and the proper resolution of disputes within society.

The task of repressing offences and maintaining public order is one of the fundamental responsibilities of the State, and is clearly manifested in criminal proceedings. Unlike civil litigation, where individuals or private entities seek redress for wrongs or disputes, criminal action focuses on society's response to behaviour that is considered to be in breach of its laws.

In the criminal justice system, it is the state that takes the initiative in prosecuting criminal offences. This action is often taken by the public prosecutor, who acts as the representative of society. The aim of criminal proceedings is not only to repair the harm caused to the victim, but also to prevent future crimes by punishing the offender and deterring others from committing similar offences. Criminal proceedings can be initiated in various ways. In many cases, it is initiated ex officio by the state, often following an investigation by the police or another law enforcement agency. For example, in a case of robbery or assault, the police investigate the crime and report their findings to the public prosecutor, who then decides whether there is sufficient evidence to prosecute.

In some legal systems, the victims of a crime or other parties can also play a role in initiating criminal proceedings. They can do this by lodging a complaint with the relevant authorities. However, even in these cases, it is the public prosecutor who ultimately decides whether or not to prosecute the case on behalf of society. The distinction between criminal proceedings and civil cases is therefore fundamental. Whereas civil cases involve disputes between private parties, criminal action involves society as a whole, represented by the state, which seeks to punish criminal behaviour and maintain public order. This approach reflects the understanding that certain behaviour harms not only specific individuals, but also society as a whole.

The public prosecutor is a key institution in the judicial system, playing a crucial role in representing the law and defending the interests of the State before the courts. Made up of magistrates, such as public prosecutors or state lawyers, the public prosecutor's office is responsible for criminal prosecutions and enforcing the law, focusing on maintaining public order and prosecuting offences. The structure of the public prosecutor's office varies between legal systems, and a concrete example of this variation can be seen in Switzerland, where the federal legal system affects the organisation of the public prosecutor's office. In each Swiss canton, the public prosecutor's office operates autonomously and is headed by a public prosecutor. The Attorney General, who is often directly elected by the people, reflects the Swiss democratic tradition and ensures that public interests are represented in a transparent and accountable manner. At cantonal level, the Attorney General is responsible for overseeing criminal investigations and prosecutions, ensuring that the laws are applied fairly and effectively. At federal level, the Public Prosecutor's Office takes a different form. It is headed by the Attorney General of the Confederation, a figure elected by the Federal Assembly. This position is of particular importance, as it deals with criminal cases that go beyond cantonal jurisdiction or involve federal crimes. For example, in large-scale cases such as terrorism, corruption at federal level, or crimes against state security, it is the Attorney General of the Confederation who takes the reins. This Swiss model illustrates how a legal system can be structured to meet the needs of a federal country, where regional autonomy is balanced with coordination at national level. It ensures that, whether for local cases or crimes of a wider scope, there is a competent and accountable institution to prosecute and represent the interests of society. This ensures a consistent application of justice, reflecting the principles of democracy and the rule of law.

In the criminal justice system, the public prosecutor plays a proactive and autonomous role in initiating criminal proceedings. Unlike in civil cases, where a party must initiate the process, in criminal cases the public prosecutor can initiate proceedings ex officio, i.e. without a prior request from a victim or another party. This ability to act ex officio is a fundamental element of the authority and responsibility of the public prosecutor. It reflects the notion that criminal offences are not just attacks on individuals, but transgressions against public order and society as a whole. As such, the public prosecutor, as the representative of the State and the interests of society, has the duty and power to prosecute these offences in order to maintain lawful order and protect public welfare. This autonomous action may be triggered by various means, including police reports, complaints from citizens, or investigations by the authorities themselves. For example, if a crime such as theft or homicide is discovered, the police investigate and pass on their findings to the public prosecutor. On the basis of this information, the public prosecutor can decide to prosecute, even if the victim does not wish to press charges or if no one has officially requested such action. This approach ensures that serious crimes or breaches of public order do not go unpunished, even in the absence of a private initiative to prosecute. It reinforces the principle that certain reprehensible acts require a response from the State in order to maintain justice and security in society.

The criminal procedure

Criminal procedure is governed by a set of mandatory rules of law, designed to ensure justice and the protection of the rights of all parties involved, in particular the person accused or charged. These strict rules serve to ensure that proceedings are conducted fairly and transparently, and that the rights of the accused are respected throughout the judicial process.

In the criminal justice system, every stage from investigation to trial is governed by precise legal standards that must be scrupulously respected by the authorities. These standards include, for example, rules on how evidence can be gathered, how suspects are questioned, and how trials are conducted. Failure to comply with these rules can result in the invalidation of evidence or even the annulment of the proceedings. Let's take the example of a search. For a search to be legal, it must generally be authorised by a warrant issued by a judge, based on sufficient evidence that a crime has been committed and that relevant evidence can be found at the location specified in the warrant. This warrant requirement is intended to protect the rights of the accused against arbitrary or abusive searches. In addition, there are strict rules regarding the manner in which the search must be conducted, in order to protect the individual's property and privacy.

These mandatory rules of criminal procedure reflect the fundamental principles of the rule of law, including respect for human rights and procedural safeguards. They aim to balance the need to investigate and prosecute criminal offences with the need to protect individual liberties and ensure fair and equitable treatment for the accused. By maintaining these high standards, the criminal justice system seeks to preserve public confidence in the integrity and fairness of the judicial process.

The adversarial procedure and the inquisitorial procedure

Criminal procedure, often referred to as criminal investigation, is an essential legal process centred on the search for and administration of evidence relating to a crime or offence. This phase of the judicial process is crucial for establishing the facts of a criminal case and determining the liability of the accused.

Criminal investigation generally begins after a crime or misdemeanour has been reported or discovered. The relevant authorities, such as the police, then undertake investigations to collect evidence, interview witnesses and gather all the information needed to establish what actually happened. This phase may involve various activities, such as searches, seizures, forensic analysis and other investigative methods. During the criminal investigation, the public prosecutor, representing the state and society, oversees the process and works closely with investigators to build a case against the accused. The aim is to gather sufficient evidence to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the accused is guilty of the crime or offence with which he or she is charged.

It is important to note that throughout the criminal investigation, the rights of the accused must be respected. This includes the right to a fair trial, the right to a lawyer, and the right not to incriminate oneself. In addition, all evidence must be collected and processed in accordance with the laws and procedures in force to ensure its admissibility in court. Once the criminal investigation is complete, if sufficient evidence is gathered to support a charge, the case can be brought before a court for trial. If the evidence is deemed insufficient, the case may be dismissed or the accused may be released.

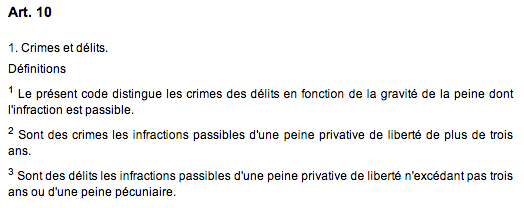

Under Swiss criminal law, the Criminal Code makes a fundamental distinction between crimes and misdemeanours, a classification based on the severity of the penalty associated with each offence. This distinction is crucial because it determines the nature of the penalties applicable and guides the corresponding judicial process.

Under the Swiss Penal Code, crimes are serious offences punishable by a custodial sentence of more than three years. These offences represent acts considered particularly harmful to society, such as homicide, serious sexual assault or acts of terrorism. For example, an individual convicted of murder in Switzerland would be charged with a felony under the Penal Code and could face a lengthy prison sentence, reflecting the seriousness of his or her act. Misdemeanours, on the other hand, are defined as less serious offences punishable either by a custodial sentence not exceeding three years or by a pecuniary penalty. These offences include acts such as petty theft, small-scale fraud or serious road traffic offences. For example, a person convicted of shoplifting could be charged with a misdemeanour and receive a lighter sentence, such as a fine or a short period of detention.

This classification between felonies and misdemeanours reflects a key principle of the Swiss justice system: the proportionality of the punishment in relation to the seriousness of the offence committed. It ensures that the heaviest penalties are reserved for the most serious offences, while providing an appropriate legal framework for dealing with less serious offences. By clearly defining these categories, the Swiss Criminal Code aims to balance the protection of society, crime prevention and respect for individual rights.

Accusatory

The historical origins of criminal procedure, particularly in societies where citizen participation in the governance and administration of justice was highly valued. This ancient approach to criminal procedure is characterised by a form of judicial 'combat', where the prosecution and the defence confront each other in a formal and solemn setting, overseen by a judge. In these systems, criminal proceedings were often initiated by a formal accusation. The plaintiff, or accuser, presented his or her accusations and evidence against the defendant, i.e. the person accused of the crime or offence. The defendant was then given the opportunity to defend himself against these accusations, often by presenting his own evidence and arguments. The role of the judge, or judges, was to referee this legal 'battle'. They ensured that the procedural rules were respected, listened to the arguments on both sides, and finally ruled in favour of one or other of the parties. This decision could result in the conviction or acquittal of the defendant.

This type of procedure reflects an era when justice was seen as a more direct and participatory form of conflict resolution. It is characteristic of political systems where the active participation of citizens in public affairs, including justice, was encouraged. A classic example of this system can be found in ancient Greece, particularly Athens, where citizens played an active role in the conduct of judicial affairs. Over time, as societies and legal systems evolved, criminal procedure became more complex and institutionalised, incorporating more modern principles of justice such as the presumption of innocence, legal representation and the rights of the defence. Nevertheless, the foundations of this procedure - an adversarial debate and the intervention of an impartial judge to decide the dispute - remain essential elements of criminal justice in many contemporary legal systems. In the context of criminal procedure, the concept of indictment is a key moment in the judicial process. When a prosecution is launched, the accused is formally charged, which means that he or she is formally informed of the charges against him or her and must answer for them in court.

In this context, the judge's role is often compared to that of an arbitrator. His main responsibility is to ensure that the 'fight' between the plaintiff, usually represented by the public prosecutor, and the defendant takes place fairly and in accordance with the law. The judge ensures that both parties have the opportunity to present their arguments, evidence and testimony, and that the trial is conducted with due respect for the rights of the defendant and the principles of justice. One of the judge's most important tasks during a criminal trial is to rule on the evidence presented. This involves assessing its relevance, reliability and admissibility according to the rules of evidence. The judge must also ensure that the evidence is presented and considered fairly, allowing both sides to challenge or support it. This approach reflects the fundamental principles of criminal justice in many legal systems: the right to a fair trial, the presumption of innocence and the right to a defence. The judge, as impartial arbiter, ensures that these principles are respected and that the final verdict, whether conviction or acquittal, is based on a fair and rigorous assessment of the evidence presented during the trial.

Criminal procedure, as it is conceived in many legal systems, is based on a structure that is at once oral, public and adversarial, each of these elements playing a crucial role in guaranteeing a fair and transparent trial. The oral nature of criminal proceedings means that most of the exchanges during the trial take place in person. The testimony of witnesses, the arguments of defence and prosecution lawyers, and the statements of the accused are presented orally before the judge and jury, if any. This form of communication allows for dynamic and direct interaction in court. It is essential for assessing the credibility of witnesses and the effectiveness of the arguments presented. For example, in a robbery trial, eyewitnesses will verbally recount what they saw, allowing the judge and jury to assess their reliability and consistency. The publicity of the trial is another fundamental pillar. It ensures that legal proceedings are open to the public, which promotes transparency and enables society to monitor the operation of the legal system. The public nature of trials serves to prevent injustice and maintain public confidence in the integrity of justice. However, there may be exceptions to protect specific interests, such as the privacy of victims in certain sensitive cases. The adversarial nature of the proceedings ensures that all parties have the opportunity to present their version of the facts, to challenge the other party's evidence and to respond to the charges. This approach ensures that the accused has a fair opportunity to defend himself. In a fraud trial, for example, the defence has the right to refute the evidence presented by the prosecution, to question the prosecution's witnesses and to present its own witnesses and evidence. These principles of criminal procedure - orality, publicity and adversarial proceedings - combine to form a balanced and fair judicial framework, essential for the fair administration of justice. They help to ensure that the trial is conducted in a transparent and fair manner, respecting the fundamental rights of the accused while seeking to establish the truth of the facts.

The essence of criminal procedure is to give fair consideration to the interests and arguments of both sides - the prosecution and the defence - without taking partisan initiatives. This principle of impartiality is essential to guarantee a fair and just trial. The judge, who plays the role of impartial arbiter in these proceedings, ensures that both parties have the opportunity to present their case, respond to the other party's arguments and submit their evidence. He also ensures that the proceedings are conducted in accordance with the rules of law and the principles of justice. The public nature of the proceedings is another crucial aspect that reinforces the transparency and impartiality of the judicial process. By being open to the public, criminal proceedings enable citizens to follow the progress of legal cases and check that justice is being done fairly. This transparency plays a key role in maintaining public confidence in the judicial system. It ensures that the trial is not only fair in theory, but also fair in practice, observable by any interested party. For example, during a trial for a serious offence, the possibility for citizens to attend hearings makes it possible to monitor whether the rights of the accused are respected and whether legal procedures are correctly followed. This serves as a democratic check on the operation of justice and helps prevent abuses or miscarriages of justice. Criminal procedure is designed to balance the interests of all parties involved and to ensure a transparent, fair and accountable administration of justice. The combination of an impartial judge and public proceedings makes a significant contribution to achieving these objectives.

The prosecution and investigation of offences are left to the initiative of private individuals, as the prosecution's resources are insufficient. The administration of evidence is deficient because the judge cannot intervene directly. As a result, the interests of the accused are somewhat prejudiced. In such a context, the judge's role is limited, which can affect the way in which evidence is administered and potentially harm the interests of the accused.

Where private parties, such as victims or their representatives, are responsible for conducting the investigation and gathering evidence, there may be a risk of bias or inadequacy in the gathering and presentation of evidence. If the prosecution does not have the resources or expertise to conduct a thorough investigation, some key evidence may be overlooked, which could lead to an incomplete representation of the facts at trial. Furthermore, if the judge does not have the power to intervene directly in the taking of evidence, it may be difficult to ensure that all relevant and necessary evidence is considered. This could put the accused at a disadvantage, particularly if the defence does not have the means or the ability to effectively challenge the evidence presented by the prosecution.

In a fair judicial system, it is essential that the interests of the accused are protected, in particular by guaranteeing the right to a fair trial, the right to be presumed innocent, and the right to an adequate defence. This means that evidence must be gathered and administered impartially and completely, and that the judge must be able to ensure that the rules of evidence are correctly applied. To remedy these shortcomings, some legal systems have strengthened the role of the public prosecution, such as the ministère public, by giving it responsibility for conducting criminal investigations. This allows for a more balanced and systematic approach to the gathering of evidence, reducing the risk of bias and ensuring better protection of the rights of the accused.

The absence of a formal pre-trial phase is a notable feature of certain legal systems, particularly that of the United States. In criminal procedure, the pre-trial phase is typically a phase preparatory to the trial, during which an investigating magistrate conducts a thorough investigation. The purpose of this investigation is to gather evidence, identify the offender, understand his or her personality, and establish the circumstances and consequences of the offence. On the basis of this information, the magistrate decides what action to take, in particular whether the case should be brought before a court for trial. In the US legal system, the investigation phase as it is known in other systems (such as France or Italy) does not exist in the same way. In the United States, the investigation is generally carried out by law enforcement agencies, such as the police, and supervised by prosecutors. Once the accused has been arrested and charged, the case is directly prepared for trial. Evidence is presented by the prosecution and defence during the trial itself, and there is no dedicated investigating magistrate to conduct an independent preliminary investigation.

This difference in procedure can have significant implications for the conduct and fairness of the trial. In systems with a formal investigation phase, the investigating magistrate plays a key role in establishing the facts before the trial, which can contribute to a more thorough understanding of the case. In contrast, in the American system, the burden of proof rests primarily with the prosecution and defence during the trial, with a more limited role for the judge in the preparatory phase. This absence of a formal pre-trial phase in the United States highlights the fundamental differences between the legal systems and underlines the importance of the methods of investigation and preparation of criminal cases in determining the truth and ensuring a fair trial.

Procedural law is essential in the resolution of disputes and offences that affect the community, particularly where crime is concerned. This branch of law defines the rules and methods by which disputes and offences are dealt with and resolved within the judicial system. The main aim of procedural law is to ensure that all trials are conducted in a fair and orderly manner, protecting the rights of the individuals involved while serving the public interest.

The history of procedural law dates back to ancient times and has evolved over the centuries. For example, in his work "Germania", the Roman historian Tacitus mentions the existence of courts among the Germanic peoples. According to Tacitus, these courts were responsible for settling disputes within the community. The principles, or leaders, were obliged to include members of the people in the judicial process. This practice bears witness to an ancient form of popular participation in justice, in which the leaders did not pass judgement alone, but were assisted or advised by members of the community. This method of dispute resolution, where judicial decisions were made with the involvement of the community, reflects an early understanding of the importance of fairness and representativeness in justice. Although modern justice systems are far more complex and formalised, the fundamental idea of participatory and representative justice remains a key principle. Today, this manifests itself through the presence of juries in certain legal systems, the election of certain judges, or the participation of the community through popular assemblies or public hearings.

In the time of the Salian Franks, around 500 AD, the judicial system involved a judge who oversaw the entire legal process. This judge was responsible for all stages of the process, from summoning the parties to enforcing the sentence. However, proposing the sentence itself was the responsibility of the "rachimbourgs", a group of seven men chosen from the community affected by the dispute. Their sentence then had to be approved by the Thing, an assembly of free men with the right to bear arms. This structure reflects a system of participatory justice, in which the community played an active role in the judicial process.

In the kingdom of the Alamanni, as stipulated in the Alamanni law (lex Alamannorum) around 720, the judge had to be appointed by the duke but also approved by the people. This requirement underlines the importance of community acceptance and legitimacy in the selection of judges. The Carolingian judicial reform, initiated around 770 under the reign of Charlemagne, made significant changes to this system. The power to pass judgement was entrusted to aldermen, who were permanent judges. This reform reduced the role of the Thing in approving sentences, thereby further centralising judicial power. The distinction between low justice (causae minores) and high justice or criminal justice (causae majores) established at this time is particularly noteworthy. It laid the foundations for the modern distinction between civil and criminal procedure. The lower courts dealt with minor cases, often of a civil nature, while the higher courts dealt with criminal cases, which were considered more serious and involved harsher penalties. These historical developments in the management of justice reflect a transition from a judicial system based on community participation to a more centralised and organised system, paving the way for contemporary judicial structures. They also show how fundamental principles of law, such as legitimacy, representativeness and the distinction between different types of dispute, have evolved and taken shape over time.

Inquisitory

The inquisitorial procedure has its origins in ecclesiastical jurisdictions and canon law, before spreading to secular legal systems, particularly from the 13th century onwards. In an inquisitorial procedure, the judge or magistrate plays an active role in the search for the truth. Unlike adversarial proceedings, where the emphasis is on an adversarial confrontation between the defence and the prosecution, in inquisitorial proceedings the judge conducts the investigation, questions the witnesses, examines the evidence and determines the facts of the case. The main objective is to discover the objective truth, rather than relying solely on the arguments and evidence presented by the opposing parties.

Historically, this method has been strongly influenced by the practices of Church tribunals, which sought to establish spiritual and moral truth through a thorough process of investigation by ecclesiastical authorities. In canon law, the search for truth was seen as a moral and spiritual duty, and this influenced the way investigations were conducted. In the 13th century, the inquisitorial procedure began to be adopted in the secular judicial systems of Europe. This adoption was stimulated by the desire for more systematic and centralised justice, in contrast to traditional judicial methods that often relied on oral evidence and direct confrontation between the parties. In modern systems that follow the inquisitorial procedure, such as those in many European countries, the judge retains a central role in investigating the facts and conducting the trial. However, it is important to note that contemporary judicial systems have evolved to incorporate procedural safeguards designed to protect the rights of the accused, while allowing for a thorough and objective investigation of the facts.

The perception that the inquisitorial procedure meets the needs of an authoritarian regime, by placing the interests of society above those of the individual, stems from the very nature of this procedure. Indeed, in an inquisitorial system, the judge or magistrate plays a central and active role in the investigation, the gathering of evidence and the establishment of facts, which can sometimes be seen as a concentration of power likely to favour the interests of the State or society more broadly. In authoritarian regimes, this type of judicial system can be used to reinforce state control, with an emphasis on preserving public order and security, sometimes to the detriment of individual rights. The significant power given to the judge in the conduct of the investigation and in decision-making can lead to an imbalance, where the rights of the accused to a fair trial and an adequate defence are compromised. However, it is important to stress that the inquisitorial procedure, in its modern form, is practised in many democratic countries, where it is governed by laws and regulations designed to protect the rights of individuals. In these contexts, mechanisms are in place to ensure that the rights of the accused, such as the right to a lawyer, the right to a fair trial and the right to be heard, are respected. The evolution of modern judicial systems shows that inquisitorial procedure can coexist with respect for individual rights, provided that it is balanced by appropriate procedural and judicial safeguards. It is therefore crucial to consider not only the structure of the inquisitorial procedure, but also the legal and institutional context in which it is implemented.

The inquisitorial procedure takes its name from the "inquisitio", an initial formality that defines the conduct of an investigation and, by extension, of the entire trial. In this type of procedure, the magistrate plays a predominant role from the outset of the investigation, which is often initiated ex officio, i.e. without a specific complaint being lodged by a private party. The investigation may be initiated by the magistrate himself or by a public official, such as a public prosecutor or police officer. The magistrate is responsible for collecting and examining evidence, interviewing witnesses and, in general, conducting the investigation to establish the facts of the case. This approach differs significantly from adversarial proceedings, where the investigation is often conducted by the parties (prosecution and defence), who then present their evidence and arguments before a judge or jury. In addition to conducting the investigation, in an inquisitorial procedure the magistrate also directs the proceedings during the trial. He or she asks questions of witnesses, examines the evidence and guides the discussion to ensure that all relevant aspects of the case are addressed. This active role of the magistrate is designed to ensure a full understanding of the facts and to help the court reach a judgment based on a complete analysis of the evidence. This system has its historical roots in canon law and ecclesiastical jurisdictions, where the search for truth was seen as a moral and spiritual imperative. In contemporary judicial systems that use the inquisitorial procedure, although the role of the magistrate is central, procedural safeguards are generally put in place to protect the rights of the accused and ensure the fairness of the trial.

In the inquisitorial procedure, the magistrate has considerable investigative powers, which are exercised in a manner distinct from the adversarial procedure more familiar in other legal systems. The investigation conducted by the magistrate is often characterised by its secrecy, its written nature and its lack of adversarial nature.

The secret nature of the inquisitorial investigation allows the magistrate to gather evidence without external intervention, which can be crucial in preventing the concealment or destruction of evidence, especially in complex or sensitive cases. For example, in a large-scale corruption case, the confidentiality of the initial investigation can prevent suspects from tampering with evidence or influencing witnesses. The predominance of written documentation in this system means that statements, investigation reports and evidence are recorded and stored primarily in written form. This method ensures an accurate and durable record of information, but can limit the dynamic interactions that occur in oral exchanges, such as those observed in hearings or interrogations. In addition, the lack of adversarial character during the investigation phase can raise questions about the fairness of the trial. In an inquisitorial procedure, the opposing parties, particularly the defence, do not always have the opportunity to challenge or respond directly to the evidence gathered by the magistrate during this phase. This situation can lead to imbalances, particularly if the defence does not have access to all the information gathered or cannot challenge it effectively. It is therefore essential that control mechanisms and procedural safeguards are in place to balance the magistrate-centred approach of the inquisitorial procedure. These mechanisms must ensure respect for the rights of the accused, including the right to a fair trial and the right to an adequate defence, while allowing for a thorough and objective investigation of the facts. The aim is to ensure that the judicial system achieves a balance between the effectiveness of the investigation and respect for fundamental rights.

The inquisitorial procedure, characterised by an investigation conducted mainly by judges, has significant advantages and disadvantages that influence its effectiveness and fairness. One of the major advantages of this system is that it reduces the risk of guilty parties escaping justice. Thanks to the judge's proactive and thorough approach to conducting the investigation, it is more likely that relevant evidence will be uncovered and those responsible for offences identified. This methodology can be particularly effective in complex or sensitive cases, where a thorough investigation is required to uncover the truth. However, the disadvantages of the inquisitorial procedure are not negligible. One of the most worrying risks is the possibility of convicting innocent people. Without a robust defence and the opportunity for adversarial debate during the investigation phase, defendants may find themselves at a disadvantage, unable to effectively challenge the evidence against them. This can lead to miscarriages of justice, where innocent people are convicted on the basis of one-sided investigations. On a technical level, the inquisitorial procedure is often criticised for its length. The thorough and written nature of the investigation can lead to considerable delays in the resolution of criminal cases, prolonging the time that defendants and victims wait for the case to be resolved. Furthermore, the emphasis on written documentation and the lack of direct interaction during the trial can lead to a dehumanisation of the judicial process. This approach can neglect the human and emotional aspects of a case, focusing strictly on written evidence and formal procedures. To mitigate these drawbacks, many judicial systems that use the inquisitorial procedure have introduced reforms to strengthen the rights of the defence, speed up proceedings and incorporate more interactive and humane elements into the judicial process. These reforms aim to balance the effective search for the truth with respect for the fundamental rights of defendants and victims.