« The costs of production » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 80 : | Ligne 80 : | ||

Implicit costs, often referred to as unrecorded costs or opportunity costs, are essential elements in assessing a company's real profitability. The following examples perfectly illustrate the nature of implicit costs: | Implicit costs, often referred to as unrecorded costs or opportunity costs, are essential elements in assessing a company's real profitability. The following examples perfectly illustrate the nature of implicit costs: | ||

# The cost of equity capital invested in the business: When an entrepreneur invests equity capital in his business, he forgoes the interest or return he could have obtained by investing this money elsewhere, such as in a savings account, bonds, shares, or any other investment opportunity. The implicit cost here is the lost financial return. For a complete economic analysis, this opportunity cost must be considered as a real expense, because it represents the real cost of capital that is not available for other uses. # The salary that the entrepreneur would receive as an employee in another activity: If the entrepreneur devotes his time and effort to his business, he or she cannot allocate them to paid employment elsewhere. The implicit cost is therefore the salary that the entrepreneur could have earned by working for someone else or by engaging in another professional activity. This cost must be taken into account when assessing the profitability of the business, as it represents potential income that has not been realised. | # The cost of equity capital invested in the business: When an entrepreneur invests equity capital in his business, he forgoes the interest or return he could have obtained by investing this money elsewhere, such as in a savings account, bonds, shares, or any other investment opportunity. The implicit cost here is the lost financial return. For a complete economic analysis, this opportunity cost must be considered as a real expense, because it represents the real cost of capital that is not available for other uses. | ||

# The salary that the entrepreneur would receive as an employee in another activity: If the entrepreneur devotes his time and effort to his business, he or she cannot allocate them to paid employment elsewhere. The implicit cost is therefore the salary that the entrepreneur could have earned by working for someone else or by engaging in another professional activity. This cost must be taken into account when assessing the profitability of the business, as it represents potential income that has not been realised. | |||

These implicit costs are often difficult to quantify precisely, as they involve estimates of what a 'better' alternative might be. Nevertheless, they are crucial to economic decisions because they provide a more realistic measure of a company's economic performance. Ignoring implicit costs could lead to an overstated assessment of the company's financial health and success, as the accounting profit might appear higher than the actual economic profit after taking these costs into account. In short, implicit costs play a vital role in making informed economic decisions. They help to assess whether the company's resources are being used in the most advantageous way possible and whether the company is generating a sufficient return to justify these opportunity costs. | These implicit costs are often difficult to quantify precisely, as they involve estimates of what a 'better' alternative might be. Nevertheless, they are crucial to economic decisions because they provide a more realistic measure of a company's economic performance. Ignoring implicit costs could lead to an overstated assessment of the company's financial health and success, as the accounting profit might appear higher than the actual economic profit after taking these costs into account. In short, implicit costs play a vital role in making informed economic decisions. They help to assess whether the company's resources are being used in the most advantageous way possible and whether the company is generating a sufficient return to justify these opportunity costs. | ||

Version du 12 janvier 2024 à 12:52

Based on a course by Federica Sbergami[1][2][3]

Microeconomics Principles and Concept ● Supply and demand: How markets work ● Elasticity and its application ● Supply, demand and government policies ● Consumer and producer surplus ● Externalities and the role of government ● Principles and Dilemmas of Public Goods in the Market Economy ● The costs of production ● Firms in competitive markets ● Monopoly ● Oligopoly ● Monopolisitc competition

The analysis of production costs is a fundamental aspect of industrial organisation in microeconomics. This analysis is crucial because the main objective of any economic agent, particularly firms, is to maximise profits. The study of production costs helps to understand the behaviour of firms in different market contexts, including perfect competition and various forms of imperfect competition.

Production costs are key factors influencing production decisions and prices. In other words, a company's strategies and programmes depend heavily on its choices regarding production factors. The ultimate objective of companies is to maximise their profits, and production costs, which directly affect the supply function, play a significant role in determining profits.

This analysis enables companies to make informed decisions about how much to produce, what technologies to use, and what prices to charge in order to remain competitive while maximising their profits. Costs can include items such as raw materials, labour, energy and equipment depreciation. By understanding these costs and managing them effectively, companies can optimise their production and strengthen their market position.

Analysis of production costs

The formula for company profit is quite simple in theory. Profit (π) is calculated by subtracting total cost (TC) from total revenue (TR). In mathematical terms, this is written :

π = RT - CT

Here, π represents profit, RT total revenue and TC total cost.

Total revenue (RT) is calculated by multiplying the unit price of a good or service by the quantity sold. In other words :

RT= Price × Quantity sold

This formula highlights the importance of price and sales volume in generating revenue for a business. A high price or a large quantity sold can both increase total revenue, while effective cost management can reduce total cost, thereby increasing profit. However, it is important to note that this simplified formula does not take into account other factors that can influence profit, such as fixed and variable costs, economies of scale, market conditions, and pricing strategy. In practice, maximising profit is often more complex and requires a detailed analysis of all these factors.

The analysis of production costs is central to understanding the market supply function in microeconomics. This supply function is traditionally seen as an increasing relationship between price and quantity offered. This relationship is explained by the fact that, when prices rise, companies have an incentive to produce more in order to make higher profits. Production costs play a crucial role in this dynamic. They include both variable costs, which change with the level of production, and fixed costs, which remain constant regardless of the quantity produced. Understanding these costs enables companies to determine the quantity of production that maximises their profits at different price levels.

In parallel, consumer theory examines the factors influencing the demand function, which indicates the quantity of a good or service that consumers are prepared to buy at different prices. This demand is shaped by factors such as consumers' incomes, their preferences, the prices of substitute and complementary goods, and their future expectations. Analysis of these factors is essential to understanding how consumer choices influence overall market demand.

Thus, production cost analysis and consumption theory are two pillars of microeconomics that complement each other in explaining market dynamics. On the one hand, companies evaluate their production costs to define their supply, and on the other, consumers make their purchasing decisions based on various factors that influence their demand. The meeting of supply and demand determines market equilibrium, influencing price formation and the quantity of goods traded. This integrated understanding of supply and demand is crucial for analysing market economics, consumer trends and corporate strategies.

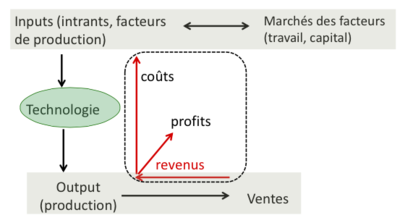

This chart provides a visual representation of the basic structure of a company's production and economy. In this model, inputs or factors of production such as labour and capital are acquired on the relevant markets and form the basis of any production process. These inputs are then transformed into finished products or services (outputs) using technology, which can include production methods, equipment and specialised knowledge.

Once the technology has been used to transform the inputs into outputs, the latter are sold on the market, generating revenue for the company. This revenue is a function of the price at which the goods or services are sold and the quantity of them purchased by consumers. The diagram suggests that revenues and costs are intrinsically linked, with costs being a necessary consequence of production. These costs include everything required to produce the output, including but not limited to wages, material costs, and depreciation of capital.

Profits are represented to illustrate their derived nature, being the residual result once costs have been subtracted from revenues. This is the figure that companies are most interested in, as it measures the efficiency with which they have transformed their inputs into profitable outputs. Profits are essential not only for the survival and growth of the business, but also for strategic decisions about investing in new technologies or expanding into new markets.

This schematic model also highlights the importance of input markets, which are key elements of a company's external environment. These markets determine the availability and cost of essential inputs, thereby influencing production costs. Companies therefore need to monitor these markets closely to optimise their cost decisions.

However, it is important to note that this diagram is a simplification of the real economic process. In reality, companies are faced with much more complex decisions, involving a variety of external factors such as changes in regulation, fluctuations in market demand, and rapidly evolving technology. In addition, companies must also manage fixed and variable costs, economies of scale, and differentiated pricing strategies to remain competitive. In summary, although the diagram captures the essence of the business process, it does not capture all the nuances and complexities of the real business world.

Production function and total costs

What is the cost of production

Opportunity cost

The second economic principle deals with a fundamental concept in microeconomics: opportunity cost. This principle highlights the fact that the real cost of any action, investment or acquisition is not measured solely by the amount of money spent to obtain it. In addition to financial transactions, the opportunity cost also includes the value of the best alternative given up in order to make the choice. To illustrate, let's consider an individual who decides to spend an hour studying instead of working, where he could earn 20 euros. The opportunity cost of this hour's study is not just the effort or energy spent on learning, but also the 20 euros he did not earn by working. In this way, opportunity cost provides a more complete and accurate view of economic choices.

In economics, this concept is crucial because it highlights the fact that every choice involves a potential hidden cost associated with the non-selection of an alternative. Companies and individuals use the notion of opportunity cost to make informed and rational decisions, by comparing the expected benefits of an option with those of the best alternative not chosen. Taking opportunity cost into account is therefore essential for understanding incentives and behaviour in economics. It forces decision-makers to consider not only the immediate benefits but also the potential benefits that must be abandoned. This ensures that scarce resources are allocated in the most efficient way to maximise value and welfare.

Explicit vs implicit costs

In the context of a company producing a good, costs are often classified into two categories: explicit and implicit, reflecting different aspects of the economic sacrifices involved in the production process.

Explicit costs are the direct monetary payments that the firm must make to acquire the necessary factors of production. These payments can include salaries paid to employees, purchase prices for raw materials, rents for plant or equipment, interest on loans, and any other cash expenditure that can be recorded and accounted for. They are often easily quantifiable and are recorded in the company's accounting books, playing a key role in the calculation of net profit in the financial statements.

On the other hand, implicit costs represent the value of resources that the company has chosen not to use for another potentially profitable opportunity. These costs are often non-monetary and may not be evident in a company's traditional balance sheet. For example, if a business owner uses a building they own for their business rather than renting it out to a third party, the implicit cost is the potential rent lost, or the income it could have generated. Similarly, if the owner devotes his own time to the business, the implicit cost may be the salary he could have earned by working elsewhere.

The economic approach recognises that implicit costs, like explicit costs, are real and affect the economic profit of the business. By taking into account implicit costs, it is possible to calculate economic profit, which is often lower than accounting profit because of the inclusion of these non-monetary costs. Economic profit is a more complete measure of profitability, as it reflects the total cost of the opportunities sacrificed to produce a good or service.

To maximise its economic profit, a company must therefore consider both explicit and implicit costs, ensuring that it uses its resources in the most efficient way in relation to all available options. It is this overall analysis that informs strategic decisions and contributes to the judicious management of the company's resources.

Illustration by Examples of Implicit Costs

Implicit costs, often referred to as unrecorded costs or opportunity costs, are essential elements in assessing a company's real profitability. The following examples perfectly illustrate the nature of implicit costs:

- The cost of equity capital invested in the business: When an entrepreneur invests equity capital in his business, he forgoes the interest or return he could have obtained by investing this money elsewhere, such as in a savings account, bonds, shares, or any other investment opportunity. The implicit cost here is the lost financial return. For a complete economic analysis, this opportunity cost must be considered as a real expense, because it represents the real cost of capital that is not available for other uses.

- The salary that the entrepreneur would receive as an employee in another activity: If the entrepreneur devotes his time and effort to his business, he or she cannot allocate them to paid employment elsewhere. The implicit cost is therefore the salary that the entrepreneur could have earned by working for someone else or by engaging in another professional activity. This cost must be taken into account when assessing the profitability of the business, as it represents potential income that has not been realised.

These implicit costs are often difficult to quantify precisely, as they involve estimates of what a 'better' alternative might be. Nevertheless, they are crucial to economic decisions because they provide a more realistic measure of a company's economic performance. Ignoring implicit costs could lead to an overstated assessment of the company's financial health and success, as the accounting profit might appear higher than the actual economic profit after taking these costs into account. In short, implicit costs play a vital role in making informed economic decisions. They help to assess whether the company's resources are being used in the most advantageous way possible and whether the company is generating a sufficient return to justify these opportunity costs.

Accountant vs. economist analysis in assessing a company's costs and profits

The role of the accountant and the economist in assessing the costs and profits of a business differs significantly because of their respective approaches to implicit costs.

The accountant focuses on concrete financial transactions and cash flows. He calculates the accounting profit by subtracting explicit costs, which are the monetary payments made for the company's operations, from the income generated by the sale of goods or services. Explicit costs are therefore all costs that come directly out of the company's cash flow and are recorded in the accounting books: salaries paid, rents, cost of raw materials, interest on loans, etc. Implicit costs, being non-monetary, are recorded in the profit and loss account. Implicit costs, being non-monetary and not representing a real cash flow, are not taken into account in traditional financial statements.

Economists, on the other hand, include both explicit and implicit costs in their calculations to obtain what is known as economic profit. This approach is broader because it recognises that resources have a value beyond their direct monetary cost. By incorporating opportunity costs, the economist measures the real cost of production and the financial success of the business in terms of maximising value rather than simply maximising cash flow. Economic profit is thus defined as revenues minus the sum of explicit costs and implicit costs.

This distinction is crucial because it can lead to very different interpretations of a company's financial performance. A positive accounting profit does not necessarily mean that the company is economically viable if, once the implicit costs have been taken into account, the economic profit turns out to be zero or negative. Consequently, decisions based solely on accounting data can sometimes be misleading if the opportunity costs of the resources employed are not also taken into account.

Economic profit and accounting profit =

The distinction between economic profit and accounting profit is fundamental to the analysis of a company's performance.

Accounting profit is the financial result that remains after subtracting explicit costs from total revenues. It is the figure that is usually reported in a company's financial statements and the one on which business decisions are often based. It is an indicator of the company's immediate operating profitability.

Economic profit, on the other hand, takes into account both explicit and implicit costs. Economic profit is calculated by subtracting from total revenue not only explicit costs, but also the value of the opportunity costs of the resources used in the production process. This includes elements such as the cost of own capital and the alternative wage that the entrepreneur could earn elsewhere. Economic profit is therefore a measure of profitability that reflects the overall efficiency with which a company uses all its resources, including those for which it makes no direct monetary payment.

Given that economic profit includes additional costs that accounting profit does not (opportunity costs), it is logical that economic profit can never exceed accounting profit. If all opportunity costs were zero, then economic profit and accounting profit would be equal. However, in reality, there are almost always opportunity costs, so the economic profit is often lower than the book profit.

It is quite possible for a company to show a positive accounting profit while having an economic profit of zero. This can happen when the opportunity costs consumed by the company are exactly equivalent to the book profit. In such a situation, although the company appears profitable from an accounting point of view, economically it is merely covering all its costs, including its opportunity costs, without generating any real return on its resources. This is a state of "normal profit", where the company just covers its implicit and explicit costs, but does not obtain any surplus or real economic gain.

Cette comparaison visuelle met en contraste deux méthodes d'évaluation de la performance financière d'une entreprise : l'une selon le point de vue économique et l'autre selon le point de vue comptable.

On the one hand, the economic point of view takes a broader view of profitability. This model breaks down total revenue into three segments. Starting from the bottom, explicit costs are direct payments for resources such as labour, materials and rent. Above these are the implicit costs, which represent the value of what the business has given up by using its resources in the current way rather than the best available alternative. This could include, for example, the potential income from an investment that the company's own capital could have earned elsewhere, or the salary that an owner could earn by working in another business. The top section, coloured green, shows economic profit, also known as 'overprofit'. This is the amount left after all costs, explicit and implicit, have been subtracted from the total revenue. This economic profit is often much smaller than the accounting profit, because it takes into account a wider range of costs.

On the other hand, the accounting view focuses solely on tangible transactions and cash flows. The explicit costs are subtracted from the total revenue to determine the accounting profit, represented in the upper part of the graph. This profit ignores opportunity costs and therefore tends to present a more optimistic picture of the company's financial health.

The graph highlights an important concept: a positive book profit does not necessarily mean that the company is economically profitable. It is possible that, even if a company shows an accounting profit, it may have an economic profit of zero or even negative once opportunity costs are taken into account. This can lead to a misunderstanding of the company's true performance, because the book profit overstates its profitability by ignoring opportunity costs.

This image illustrates the need for companies to take into account not only their immediate costs and revenues but also the opportunity costs associated with their economic decisions. This enables a more accurate assessment of financial performance and helps to ensure that resources are allocated in the most efficient way. For decision-makers and analysts, this distinction is essential for making informed choices that take into account the total value that the business creates or could create.

The production function and total costs

The production function and the total cost function are two closely related concepts in the economic analysis of a company's production. The production function establishes a technical link between the quantities of inputs used and the quantity of outputs produced. It reflects the efficiency with which a company transforms inputs, such as labour, raw materials and capital, into finished products or services. This relationship is often represented graphically and can take different forms depending on the technologies and production processes used by the company.

The total cost function, on the other hand, relates the quantity produced to the corresponding production costs. Production costs include all the explicit and implicit costs associated with the manufacture of goods or services. Total costs generally increase with the quantity produced, but not always in a linear fashion due to the existence of fixed costs that do not change with production and variable costs that do.

The interaction between the production function and the total cost function is fundamental. The technical constraints of the production function, such as the laws of diminishing returns, have a direct influence on total costs. For example, if a company increases the quantity of an input, output may initially increase at an increasing rate. However, after a certain point, adding more inputs may lead to a less than proportional increase in output due to saturation of the efficiency of the additional inputs.

Economists use the total cost function to understand how costs vary with changes in the level of output and to identify the level of output where average costs are minimised. This is crucial for pricing and production decisions. By identifying the marginal cost of production - the cost of producing an additional unit - companies can determine the optimal selling price and quantity of output to maximise profits.

The production and total cost functions therefore provide an overview of a company's production efficiency and cost structure. Understanding their interdependence is essential for economic analysis and for the strategic planning of a company.

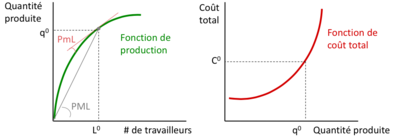

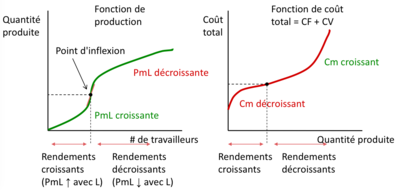

These two separate graphs represent a different concept in production economics.

The graph on the left describes a production function with the quantity produced on the vertical axis and the number of workers (which is a production input) on the horizontal axis. The green curve represents the production function and shows how the quantity produced increases with the number of workers. The slope of the curve at a specific point is represented by PmL, which stands for marginal labour productivity. This is the additional contribution to output from the addition of an extra unit of labour. Initially, the curve shows that marginal productivity is increasing, which is indicated by the upward slope of the production curve. However, as the number of workers continues to increase, the curve flattens, indicating a decrease in the marginal productivity of labour. This may be due to diminishing returns, where the addition of extra workers leads to a less than proportional increase in output as other factors (such as machinery or capital) become limiting.

The graph on the right represents the total cost function with total cost on the vertical axis and quantity produced on the horizontal axis. The red curve indicates that total costs increase with the quantity produced. Initially, the curve rises slowly, reflecting fixed costs that do not change with production. As production increases, the curve becomes steeper, reflecting the increase in variable costs. Total cost comprises fixed costs plus variable costs multiplied by the quantity produced. As the curve is in the shape of an inverted J, this suggests that the company is experiencing increasing returns to scale up to a certain point, after which it experiences decreasing returns to scale.

Analysing these graphs is crucial for business management. The production function shows how labour efficiency affects the quantity of goods or services that can be produced, while the total cost function shows how these production levels translate into costs. Understanding these relationships helps companies optimise their production levels to maximise profits. For example, a company might seek to produce at a level where marginal productivity is high before diminishing returns begin to manifest themselves, while monitoring total costs to ensure that variable costs do not begin to rise disproportionately to output.

Marginal and average product of labour

The marginal product of labour (MPL) is a fundamental concept in economics that describes the additional impact on total output of adding an extra worker, assuming that all other factors of production remain constant. It is a measure of the marginal efficiency of labour in the production process.

Mathematically, for small increases, the marginal product of labour can be expressed as the ratio of the change in quantity produced () to the change in labour (), giving the formula:

This formula represents the rate of change in output relative to the change in the amount of labour used, i.e. the slope of the production function on the graph. In a more detailed and precise analysis, especially when we are interested in infinitesimally small changes, the marginal product of labour is represented by the partial derivative of the quantity produced with respect to labour, noted as :

This partial derivative gives the exact slope of the production function at a given point and reflects the increase in output resulting from the addition of an infinitesimal unit of labour.

The concept of marginal product is crucial to understanding how companies make decisions about the amount of labour to employ. Theoretically, a firm increases the quantity of labour up to the point where the marginal product of labour equals the real wage, i.e. the cost of this additional unit of labour. At this point, the firm maximises its profit, because hiring an extra worker would not produce enough extra output to cover the cost of his wage.

In practice, the firm seeks the level of output where the marginal cost of production (which includes the marginal product of labour) equals the marginal revenue in order to maximise profits. However, various factors such as technological changes, labour market adjustments and regulations can influence the marginal product of labour and, consequently, the firm's optimal labour strategy.

The production function illustrated suggests that the marginal product of labour (MPL) is decreasing, implying that the addition of extra workers increases output but in ever smaller proportions. This is a manifestation of the principle of diminishing returns, where the efficiency of each additional worker decreases as the quantity of labour increases, keeping the other factors of production constant.

In mathematical terms, this means that the first derivative of the production function with respect to labour, , decreases as L increases. Graphically, the slope of the production curve, which represents the AMP, decreases as you move along the curve to the right, indicating that each additional worker contributes less to total output than the previous worker.

Average labour product (ALP), on the other hand, is a different measure that indicates the average output per worker. It is calculated by dividing total output (q) by the total number of workers (L), given by the formula . On a graph of the production function, the PML is represented by the slope of a ray starting from the origin and going to a specific point on the production curve. This radius indicates the average output for all levels of labour employed up to that point.

When the number of workers is low, the LMP can increase as additional workers are hired, as they contribute significantly to the increase in output. However, under diminishing returns, there will come a point where the addition of new workers will start to decrease the LMP, because the total increase in output will be less than the increase in the number of workers. This happens when the PML is lower than the PML.

Understanding these indicators is crucial for companies when making decisions about employing additional workers. Companies will seek to balance the cost of adding workers with the benefits of additional output to maximise efficiency and profitability.

Diminishing returns

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns is a fundamental principle in economics that describes how, after a certain point, each additional unit of a factor of production (in this case, labour) contributes less to total output than the previous one, when all other factors of production are held constant. It's a law that has important implications for productivity and production decision-making.

The intuition behind this law can be understood by a simple example: imagine a kitchen with a single oven and several cooks. Initially, adding more cooks may increase meal production because there is enough work for everyone and the oven is used optimally. However, once you have reached the optimum number of cooks in the kitchen, adding more staff will not cook the meals any faster because the oven becomes a bottleneck. The extra cooks may even get in each other's way, which can lead to a reduction in overall efficiency.

Applied to the wider context of economic production, this means that if a company continues to add labour to a fixed quantity of other resources (such as machinery, buildings or technology), the additional contribution of each new worker will decrease. The first workers can make efficient use of the machines and space available, but subsequent workers will have fewer machines to use and less space to work in, reducing their marginal productivity.

This law explains why companies cannot simply increase their production indefinitely by adding more workers. Instead, they have to find a balance between the number of workers and the amount of other resources at their disposal. To increase production beyond a certain point, a company will need to invest in other factors of production, such as purchasing additional machinery or expanding facilities, rather than relying solely on adding labour.

When workers find themselves having to share limited resources such as computers or photocopiers, individual efficiency begins to decline. This decline initially manifests itself in small inefficiencies, such as waiting to use equipment, but can quickly escalate into more significant coordination and communication problems as more workers are added. Delays pile up, workers spend more time waiting than producing, and frustration can lead to low morale, further affecting productivity.

Graphically, this translates into a production function which, after a certain point, flattens out as the quantity of work increases, reflecting a decrease in marginal productivity. Each additional worker adds less to total output than the worker who preceded him. The graph of the total cost function reveals the financial impact of this law: as output increases, marginal costs - the cost of producing an additional unit - also begin to rise. This is because, if production requires more labour for each additional unit due to resource congestion, then the cost of producing that additional unit will inevitably rise.

In reality, companies can encounter this problem when their size reaches a point where resources start to become scarce in relation to the number of employees. The solution to avoiding this pitfall is not always to add more resources, but may also involve better management of existing resources, improving work processes or investing in technologies that improve efficiency.

The intuition behind the law of diminishing marginal returns and its impact on costs is that efficiency and profitability can suffer if a company fails to properly balance its use of labour with the other resources at its disposal. This highlights the importance of strategic resource management to optimise production and control costs in a given production environment.

Case Study: Production Function and Total Cost

The example below shows the production function and cost structure of a pizza producer as a function of the number of workers employed. When the pizza shop employs no workers, there is naturally no production, and the total cost is made up purely of the fixed cost of the shop, which amounts to 30. This sum is probably representative of costs such as rent, utilities and equipment depreciation, which are invariable whatever the level of activity.

By introducing the first worker, production starts at 50 pizzas, indicating a significant contribution to the business from this single worker. The total cost rises modestly to 40, incorporating the fixed cost of the workshop plus an additional variable cost of 10 for the labour. This additional cost represents the wage or salary of the worker.

With each additional worker added, the production of pizzas increases, but it is interesting to note that the increase in production decreases each time, from 40 extra pizzas with the first worker to only 10 extra pizzas with the fourth worker. This illustrates the law of diminishing marginal returns, where each additional worker makes a smaller and smaller contribution to overall production, probably due to the limitation of shared resources such as workspace or kitchen equipment.

At the same time, although the fixed cost of the workshop remains constant, the total cost of labour increases linearly with the addition of each new worker. This linear increase is the result of adding the cost of labour for each new worker, assuming that each worker costs the same amount, regardless of the output produced.

Finally, the total cost of production, which is the sum of fixed and variable costs, rises with each addition of workers, reflecting the increase in production costs. However, given the fall in marginal productivity, the cost of producing an additional unit also rises, meaning that the company has to spend more for each additional pizza produced beyond a certain point. This suggests that, although adding labour may increase output, it does so at an increasing marginal cost, a factor that businesses need to manage carefully to maintain profitability.

This analysis highlights the importance of optimising the number of workers in production. A pizza producer, or any business, needs to identify the optimal number of workers to maximise production without incurring disproportionate costs due to diminishing marginal returns. This requires a careful understanding of fixed and variable costs and their impact on the total cost and profitability of the business.

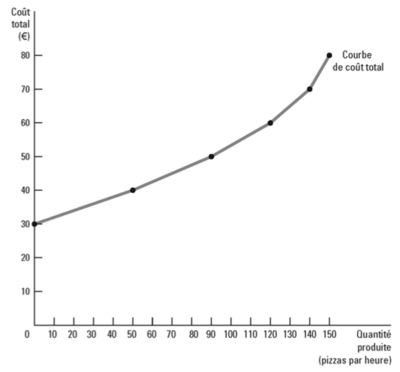

This graph represents the production function that shows the relationship between the number of workers hired and the quantity of pizzas produced per hour by a pizza producer. The graph shows a typical production curve that initially rises rapidly as workers are added, but begins to flatten out after a certain number of workers have been hired, indicating a decrease in marginal productivity.

Initially, with the addition of the first workers, the increase in output is substantial for each additional worker, illustrating high marginal productivity. This may be due to a more efficient use of equipment and a specialisation of work that allows a significant increase in output.

However, the graph also shows that, after the addition of a few workers, output continues to grow but at a slower rate. This happens because each additional worker contributes less to overall output than the previous one, a phenomenon that reflects the Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns. This law suggests that there is an optimal point of work beyond which the efficiency of each additional worker begins to decline, often due to the sharing of limited resources or congestion.

The graph shows that hiring the fourth and fifth workers, for example, increases output but at a decreasing rate relative to the first workers. This can be interpreted as a sign that workspace, pizza ovens or other equipment are becoming a constraint, and that the addition of extra workers cannot be fully exploited.

For the pizza producer, this graph is essential in determining the optimal number of workers to hire in order to maximise production without incurring unnecessary costs for marginal production gains. By analysing where the curve starts to flatten, the producer can identify the point of diminishing returns and make informed decisions about the size of the workforce to maintain for optimum efficiency.

The total cost curve shown in the image represents the relationship between the quantity produced (pizzas per hour) and the total cost in euros. The curve shows an upward progression that intensifies as output increases, which is typical of total cost functions where costs vary with output.

The initial part of the curve rises relatively slowly, suggesting that fixed costs dominate when output is low. Fixed costs are expenses that do not change with the level of production, such as shop rent, the cost of equipment, and perhaps a basic salary for employees. Therefore, when the number of pizzas produced is low, the increase in total cost is moderate because variable costs (such as pizza ingredients and marginal labour costs) are still minimal.

As production increases, the curve rises more steeply. This indicates that variable costs are beginning to have a significant impact on total costs. Variable costs can include extra spending on ingredients, energy used to bake more pizzas, and extra wages for workers hired to increase production. This aspect of the curve is consistent with the law of diminishing marginal returns; as output increases, the marginal costs of producing each additional pizza increase due to the less efficient use of resources as the shop approaches or exceeds its optimal production capacity.

The shape of the curve suggests that each additional pizza costs more to produce than the previous one, indicating diminishing returns to scale in this production range. This is an important consideration for the pizza producer when planning production expansion. If he continues to increase production, the cost per unit will continue to rise, which could ultimately reduce profits.

To maximise profitability, the producer needs to find the level of production where the total cost per unit produced is lowest. This involves achieving a balance between fixed and variable costs and avoiding production beyond the point where marginal costs begin to exceed marginal revenues. The total cost curve is an essential tool for identifying this point and making informed decisions about how much to produce.

Différentes mesures de coût

Différentes mesures de coût

Coûts fixes

Les coûts fixes (CF) représentent les dépenses qu'une entreprise doit couvrir indépendamment de sa production. Ces coûts restent constants sur une période donnée même si la quantité de biens ou de services produits varie. Les coûts fixes sont souvent associés à des investissements en capital physique, tels que l'achat ou la location d'équipements et de bâtiments, qui ne changent pas en fonction de la production ou des ventes de l'entreprise.

Dans le cas d'un producteur de pizzas, les coûts fixes pourraient inclure la location de l'espace commercial, l'achat ou la dépréciation des fours à pizza et du matériel de cuisine, les salaires des employés qui sont garantis indépendamment du nombre de pizzas vendues, l'assurance, et peut-être certains services publics comme l'eau ou l'abonnement internet. Par exemple, que le producteur de pizzas fabrique 10 pizzas ou 100 pizzas, le loyer du local restera le même pour la période concernée. De même, l'achat d'un four à pizza est un coût initial qui ne change pas, que le four soit utilisé pour cuire une pizza ou utilisé continuellement.

Il est crucial pour les entreprises de comprendre et de gérer leurs coûts fixes, car ceux-ci constituent une partie importante de la structure des coûts totaux et peuvent influencer les décisions relatives aux prix, à la stratégie de production et à la viabilité à long terme. Un niveau élevé de coûts fixes peut également augmenter le risque financier de l'entreprise, car ces coûts doivent être couverts indépendamment des revenus. Les entreprises doivent donc générer suffisamment de revenus pour couvrir non seulement les coûts variables mais aussi ces coûts fixes afin d'éviter des pertes.

Coûts variables

Les coûts variables (CV) dans le cadre de la production d'une entreprise sont ceux qui fluctuent en fonction du volume d'activité ou de production. Contrairement aux coûts fixes, qui restent constants quel que soit le niveau de production, les coûts variables changent directement avec la quantité de biens ou de services produits.

Dans l'exemple d'un producteur de pizzas, les coûts variables comprennent les ingrédients nécessaires pour faire les pizzas, tels que la farine, la sauce tomate, le fromage, les garnitures, et aussi les coûts de l'énergie consommée pour faire fonctionner les fours et autres équipements de cuisine. En outre, si les travailleurs sont payés à l'heure ou à la pièce, alors leurs salaires sont également des coûts variables, car la main-d'œuvre totale requise variera en fonction du nombre de pizzas produites.

Si le producteur fabrique plus de pizzas, il aura besoin de plus d'ingrédients et peut-être d'heures de travail supplémentaires, ce qui augmentera ses coûts variables. Inversement, s'il décide de réduire la production, ses coûts variables diminueront car il utilisera moins d'ingrédients et moins de main-d'œuvre.

Les coûts variables sont essentiels à la gestion de l'entreprise car ils affectent directement la marge bénéficiaire par unité vendue. Une compréhension claire des coûts variables est nécessaire pour établir des stratégies de tarification efficaces et pour prendre des décisions concernant les niveaux de production optimaux. En contrôlant et en réduisant les coûts variables, une entreprise peut augmenter sa marge sur chaque produit vendu, ce qui est crucial pour la rentabilité globale. De même, lors de l'évaluation de la rentabilité d'un nouveau produit ou service, une analyse approfondie des coûts variables associés est fondamentale pour s'assurer que le prix de vente couvre ces coûts et contribue positivement au profit global.

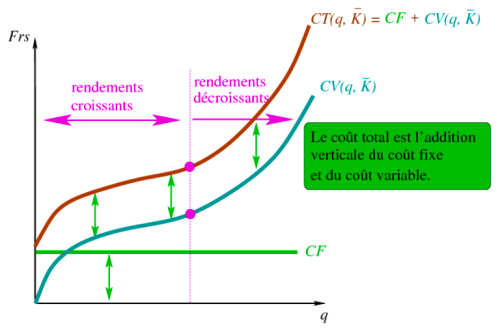

Coût total

Le coût total (CT) est la somme du coût fixe (CF) et du coût variable (CV). Cette relation est fondamentale pour comprendre la structure des coûts d'une entreprise et est exprimée mathématiquement comme suit :

CT = CF + CV

Cette équation illustre que pour chaque niveau de production, le coût total est composé d'une partie qui ne change pas, représentée par les coûts fixes, et d'une partie qui fluctue avec le niveau de production, représentée par les coûts variables. Les coûts fixes sont des dépenses qui doivent être payées indépendamment du volume de production, comme le loyer, les salaires des employés permanents, les paiements de prêts, et l'amortissement des équipements. Les coûts variables varient en fonction de la production, tels que les matières premières, les fournitures, et les heures de travail payées à la production.

Par exemple, si un producteur de pizzas a des coûts fixes mensuels de 2000 euros pour le loyer, les équipements et les salaires fixes, et des coûts variables de 2 euros par pizza pour les ingrédients et l'énergie, le coût total pour produire 1000 pizzas sera calculé en ajoutant le coût fixe au coût variable total pour cette production :

CT = CF + (CV par pizza × nombre de pizzas)

CT = 2000 + (2 × 1000)

CT= 2000 + 2000

CT=4000 euros

La compréhension du coût total est cruciale pour la prise de décision en matière de tarification et de niveau de production. En connaissant le coût total, une entreprise peut déterminer le prix de vente minimum nécessaire pour couvrir tous ses coûts et pour générer un profit. De plus, en analysant comment le coût total varie avec les changements dans le niveau de production, les entreprises peuvent identifier le point de production le plus efficace et maximiser leur rentabilité.

Coût moyen

Le coût moyen (CM), également connu sous le nom de coût unitaire, est une mesure qui permet de comprendre le coût de production par unité de bien ou de service produit. Il est dérivé en divisant le coût total (CT) par la quantité totale produite (q). Cette relation est représentée par la formule suivante :

Étant donné que le coût total est la somme des coûts fixes et des coûts variables, le coût moyen peut également être exprimé en tant que somme du coût fixe moyen (CFM) et du coût variable moyen (CVM), où le coût fixe moyen est le coût fixe par unité produite et le coût variable moyen est le coût variable par unité produite. Ainsi, le coût moyen est également représenté par la formule :

Cela signifie que pour chaque unité produite, une portion du coût fixe et une portion du coût variable sont attribuées. Le coût moyen permet aux entreprises de déterminer le coût de fabrication de chaque unité de produit, ce qui est crucial pour fixer des prix de vente appropriés et pour évaluer l'efficacité de la production.

Par exemple, si un producteur de pizzas a un coût fixe de 2000 euros et produit 1000 pizzas, le coût fixe moyen par pizza est de 2 euros (2000 euros / 1000 pizzas). Si les coûts variables totaux pour ces 1000 pizzas sont de 2000 euros, le coût variable moyen par pizza est également de 2 euros (2000 euros / 1000 pizzas). Le coût moyen pour chaque pizza serait donc de 4 euros (2 euros de CFM + 2 euros de CVM), avant de prendre en compte la marge bénéficiaire.

Comprendre le coût moyen est particulièrement important pour la stratégie de tarification. Si le coût moyen est inférieur au prix de vente par unité, l'entreprise réalise un profit sur chaque unité vendue. Si le coût moyen est supérieur au prix de vente, l'entreprise subit une perte sur chaque unité. Ainsi, l'objectif est souvent de réduire le coût moyen, soit en réduisant les coûts, soit en augmentant la production pour mieux répartir les coûts fixes sur un plus grand nombre d'unités, ce qui réduit le coût fixe moyen.

Coût marginal

Le coût marginal (Cm) joue un rôle crucial dans l'analyse économique de la production, car il mesure l'impact sur le coût total d'une entreprise résultant de la production d'une unité supplémentaire d'un bien ou d'un service. C'est essentiellement la pente de la fonction de coût total à un point donné, représentant l'augmentation du coût total pour chaque augmentation unitaire de la production.

Mathématiquement, le coût marginal est défini comme le rapport entre la variation du coût total () et la variation de la quantité produite (). La formule est la suivante :

Lorsqu'on examine de très petits changements dans la quantité produite, le coût marginal peut être exprimé comme la dérivée du coût total par rapport à la quantité. Pour des changements infinitésimaux, la formule est :

Le coût marginal est particulièrement important dans la prise de décision en matière de production et de tarification. Les entreprises chercheront à produire jusqu'au point où le coût marginal est égal au revenu marginal, qui est le revenu additionnel obtenu de la vente d'une unité supplémentaire. Ce point est crucial car il correspond au niveau de production où les profits sont maximisés. Si le coût marginal est inférieur au prix de vente de l'unité supplémentaire, il est bénéfique pour l'entreprise d'augmenter la production. Inversement, si le coût marginal dépasse le prix de vente, produire davantage réduirait le profit de l'entreprise.

En pratique, l'analyse du coût marginal aide les entreprises à ajuster leur niveau de production pour répondre aux changements de la demande du marché, aux variations des coûts des inputs ou à l'introduction de nouvelles technologies, tout en visant à optimiser l'efficacité et la rentabilité.

Exemple

Ce tableau dresse le profil des coûts de production d'un producteur de limonade. Il montre la relation entre le nombre de verres de limonade produits par heure et différents types de coûts : coût total, coût fixe, coût variable, ainsi que les coûts moyens et marginaux associés.

Le coût fixe reste constant à 3,00 euros, ce qui suggère qu'il s'agit de coûts qui ne dépendent pas du volume de production, comme le loyer ou l'amortissement des équipements. Le coût total commence à 3,00 euros lorsque aucun verre n'est produit et augmente avec la production. La différence entre le coût total à chaque étape et le coût fixe donne le coût variable, qui augmente avec le nombre de verres produits.

Les coûts fixes moyens (CFM) sont calculés en divisant le coût fixe par le nombre de verres produits. Étant donné que le coût fixe est constant, le CFM diminue à mesure que le volume de production augmente. Inversement, le coût variable moyen (CVM) est obtenu en divisant le coût variable total par le nombre de verres produits. Le coût moyen total (CM) représente la somme du CFM et du CVM et diminue d'abord avant d'augmenter légèrement, ce qui suggère qu'il pourrait y avoir une plage de production optimale où les coûts moyens sont minimisés.

Le coût marginal (Cm) représente le coût d'un verre supplémentaire et est obtenu en examinant la variation du coût total divisée par la variation de la quantité produite. Il commence à 0,30 euros et augmente progressivement, indiquant que chaque verre supplémentaire coûte plus cher à produire que le précédent. Cela reflète les rendements marginaux décroissants, où les coûts supplémentaires de production augmentent après un certain point à cause, par exemple, de la surutilisation des équipements ou de la nécessité d'embaucher plus de main-d'œuvre à un tarif plus élevé pour maintenir la production.

Cet ensemble de données permet au producteur de limonade de comprendre ses structures de coûts et de prendre des décisions éclairées sur la tarification et le niveau de production. Par exemple, en identifiant le point où le coût moyen total commence à augmenter, le producteur peut déterminer la quantité de production la plus efficace pour maximiser les profits. De plus, en comprenant le coût marginal, le producteur peut décider jusqu'à quel point il est rentable de continuer à augmenter la production.

Exemple : coût total

Ce graphique montre une courbe de coût total tracée en fonction de la quantité de pizzas produites par heure. La courbe montre une relation positive entre le coût total et le nombre de pizzas produites, indiquant que le coût total augmente avec la production.

Au début, la courbe semble augmenter à un rythme relativement constant, ce qui pourrait indiquer que les coûts variables dominent les coûts totaux après que les coûts fixes ont été couverts. Cela est cohérent avec le comportement typique des coûts variables qui augmentent proportionnellement avec la quantité produite. À mesure que la production augmente, nous pouvons observer que la pente de la courbe devient plus raide. Cela suggère que le coût de production de chaque pizza supplémentaire augmente, ce qui peut être dû à plusieurs facteurs, comme les rendements marginaux décroissants où l'ajout de plus de travail ou d'autres ressources ne se traduit pas par une augmentation proportionnelle de la production.

La pente croissante de la courbe de coût total peut également refléter le fait que l'entreprise a atteint sa capacité de production optimale et que produire des pizzas supplémentaires nécessite des investissements disproportionnés dans les intrants. Par exemple, si la capacité du four est maximisée, la production de pizzas supplémentaires pourrait nécessiter l'utilisation d'un four supplémentaire ou le passage à des heures supplémentaires pour le personnel, ce qui augmenterait le coût par unité.

L'analyse de cette courbe est essentielle pour la prise de décision en matière de gestion de production. Elle peut aider le producteur à identifier le niveau de production le plus rentable et à évaluer si les coûts actuels sont soutenables à long terme. Si la tendance de la courbe se maintient, le producteur pourrait avoir besoin de reconsidérer son processus de production, d'investir dans des équipements plus efficaces, ou de réajuster sa stratégie de tarification pour s'assurer que les coûts croissants ne grèvent pas les bénéfices.

Exemple : coût marginal

Le coût marginal reflète l'augmentation du coût total due à la production d'une unité supplémentaire d'un bien ou service. Dans un contexte de productivité décroissante, caractéristique de la loi des rendements marginaux décroissants, le coût marginal tend à augmenter à mesure que la quantité produite s'accroît. Cela se produit parce que chaque unité supplémentaire nécessite plus d'inputs ou d'efforts pour être produite, en raison des contraintes de capacité ou de l'inefficacité accrue des facteurs de production supplémentaires.

Étant donné que le coût fixe (CF) reste constant quel que soit le niveau de production, toute augmentation du coût total lorsqu'une unité supplémentaire est produite est due à une augmentation du coût variable (CV). Ainsi, le coût marginal est une mesure directe de la variation du coût variable. Mathématiquement, cela peut être exprimé comme suit:

Cela implique que le coût marginal est égal à la pente de la courbe des coûts variables par rapport à la quantité produite. Dans la pratique, cela signifie que si le coût de production de la prochaine pizza (par exemple) est plus élevé que celui de la pizza précédente, cela est dû aux coûts variables qui augmentent, comme la main-d'œuvre supplémentaire nécessaire ou les coûts de matériaux supplémentaires qui sont engagés pour maintenir la production.

Pour les entreprises, comprendre le coût marginal est essentiel pour prendre des décisions optimales en matière de production et de tarification. Produire au-delà du point où le coût marginal commence à dépasser le prix de vente peut réduire la profitabilité. Par conséquent, les entreprises visent généralement à ajuster leur niveau de production pour maintenir le coût marginal aussi bas que possible tout en satisfaisant la demande du marché.

Le graphique présenté affiche une courbe linéaire ascendante qui représente le coût marginal (Cm) en fonction de la quantité produite. L'axe vertical représente les coûts en CHF (franc suisse), tandis que l'axe horizontal représente la quantité de biens produits.

La ligne droite indique que le coût marginal reste constant avec chaque unité supplémentaire produite. Cela suggère que pour chaque unité additionnelle fabriquée, le coût supplémentaire encouru par l'entreprise reste le même. Ce type de relation linéaire est typique d'une situation où les coûts variables n'augmentent pas avec la production, ce qui pourrait être le cas si l'entreprise opère dans une zone de production avec des rendements constants.

Cependant, cette situation est assez idéale et n'est pas souvent observée dans la réalité sur de longues périodes de production ou à grande échelle, car la plupart des entreprises feront face à des rendements marginaux décroissants à un certain point. En termes simples, cela signifie que la courbe de coût marginal est généralement en forme de U, commençant par une pente négative, atteignant un minimum, puis devenant positive à mesure que la production augmente.

La situation représentée par ce graphique pourrait se produire dans un contexte où l'entreprise a une capacité de production suffisante et des ressources telles que les matières premières et la main-d'œuvre, qui peuvent être facilement et uniformément augmentées pour augmenter la production sans entraîner de coûts supplémentaires significatifs.

Pour l'entreprise, un coût marginal constant implique que la planification de la production peut être réalisée avec une certaine prévisibilité en termes de coûts. Cela facilite la prise de décision en matière de tarification et d'expansion, car la structure des coûts ne varie pas avec des augmentations ou des diminutions de la production. Toutefois, l'entreprise doit toujours surveiller la situation pour détecter tout signe de changement dans la tendance des coûts marginaux, car des augmentations pourraient indiquer des inefficacités croissantes ou des contraintes de capacité imminentes.

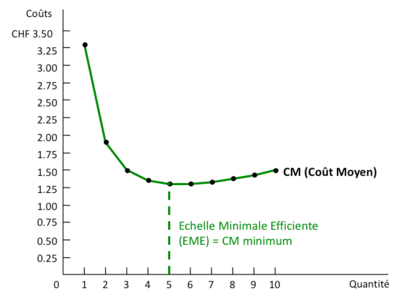

Exemple : Coût moyen

Le comportement du coût moyen est caractéristique de nombreuses structures de production et est un concept essentiel en économie. La courbe en forme de U du coût moyen reflète différentes phases de la production et de l'efficacité des coûts.

Dans la phase initiale de production, les coûts moyens tendent à diminuer à mesure que la quantité produite augmente. Cela est dû à la répartition des coûts fixes sur un nombre croissant d'unités produites. Lorsque la production est faible, chaque unité produite doit supporter une grande partie des coûts fixes, ce qui rend le coût moyen par unité relativement élevé. Cependant, à mesure que la production augmente, ces coûts fixes sont répartis sur plus d'unités, réduisant ainsi le coût moyen par unité. Cette diminution continue jusqu'à ce que l'entreprise atteigne ce qu'on appelle les économies d'échelle.

À mesure que la production continue d'augmenter au-delà de ce point, l'entreprise peut rencontrer des rendements d'échelle décroissants. Cela signifie que les coûts variables commencent à avoir un impact plus significatif sur le coût total. Les coûts variables moyens peuvent augmenter en raison de la productivité marginale décroissante des inputs supplémentaires. Par exemple, l'entreprise peut devoir payer des heures supplémentaires aux travailleurs ou faire face à des coûts d'inputs plus élevés en raison de la demande accrue. En conséquence, le coût moyen commence à augmenter, ce qui donne à la courbe du coût moyen son aspect caractéristique en U.

Cette forme en U implique qu'il existe un niveau de production optimal où le coût moyen est minimisé. Pour une entreprise, identifier ce niveau est crucial car il permet de maximiser l'efficacité et la rentabilité. Produire moins que ce niveau implique que l'entreprise n'exploite pas pleinement ses capacités de production et ses économies d'échelle, tandis que produire plus signifie que l'entreprise fait face à des inefficacités croissantes et à des coûts marginaux en hausse. Ainsi, comprendre où leur propre production se situe par rapport à cette courbe en U est essentiel pour les entreprises lorsqu'elles prennent des décisions stratégiques concernant les niveaux de production et de prix.

Le graphique illustre la courbe du coût moyen (CM) en fonction de la quantité produite, en francs suisses (CHF). Comme prévu, la courbe a une forme en U, indiquant que le coût moyen par unité diminue initialement avec l'augmentation de la production, atteint un point minimum, puis commence à augmenter à mesure que la production continue de s'accroître.

Au départ, lorsque la production est très faible, le coût moyen est élevé en raison de la distribution des coûts fixes sur un petit nombre d'unités. À mesure que la production augmente, ces coûts fixes sont répartis sur un plus grand nombre d'unités, ce qui diminue le coût moyen par unité. La partie descendante de la courbe représente les économies d'échelle réalisées à mesure que la production augmente. C'est pendant cette phase que l'entreprise devient plus efficace, réduisant les coûts moyens.

Le point le plus bas de la courbe correspond à l'Échelle Minimale Efficace (EME), qui est le niveau de production où le coût moyen est au minimum. À ce stade, l'entreprise fonctionne de manière optimale, ne pouvant pas produire une unité supplémentaire à un coût moyen inférieur. C'est le niveau de production le plus efficace pour l'entreprise.

Au-delà de l'EME, le coût moyen commence à augmenter, ce qui suggère que l'entreprise fait face à des rendements marginaux décroissants. À mesure que la production s'accroît au-delà de ce point, chaque unité supplémentaire coûte plus cher à produire, en partie à cause de l'augmentation du coût variable moyen qui pourrait être due à l'épuisement des capacités de production, à la nécessité d'investir dans des équipements supplémentaires ou plus coûteux, ou à l'embauche de main-d'œuvre supplémentaire à des tarifs plus élevés.

Pour une entreprise, il est crucial de reconnaître où se situe son EME et de chercher à maximiser la production autour de ce point pour minimiser les coûts moyens et maximiser les bénéfices. Si une entreprise produit moins que l'EME, elle n'est pas aussi efficace qu'elle pourrait l'être. Si elle produit plus, elle risque d'augmenter inutilement ses coûts, ce qui pourrait nuire à sa compétitivité sur le marché.

Coût marginal et coût moyen

La relation entre le coût marginal (Cm) et le coût moyen (CM) est un aspect clé de la théorie économique de la production. Le coût marginal est le coût de production d'une unité supplémentaire, et le coût moyen est le coût total divisé par le nombre d'unités produites. Leur interaction détermine la dynamique de la production et des coûts d'une entreprise.

Le coût marginal joue un rôle déterminant dans le comportement du coût moyen :

- Lorsque le coût marginal est inférieur au coût moyen, chaque unité supplémentaire produite coûte moins cher que le coût moyen actuel, ce qui a pour effet de tirer le coût moyen vers le bas. Cela se produit typiquement lorsque l'entreprise augmente sa production à partir d'un faible niveau de production, bénéficiant d'économies d'échelle et de l'amortissement des coûts fixes sur un plus grand nombre d'unités.

- Lorsque le coût marginal est supérieur au coût moyen, cela signifie que le coût de production de chaque unité supplémentaire est plus élevé que le coût moyen jusqu'à présent, ce qui entraîne une augmentation du coût moyen. Cela peut se produire lorsque l'entreprise a dépassé son point de rendement maximal et fait face à des rendements marginaux décroissants, où des augmentations de production entraînent des augmentations proportionnellement plus élevées des coûts.

Le point où le coût marginal coupe le coût moyen est particulièrement significatif. Cela se produit au minimum du coût moyen, qui est aussi l'Échelle Minimale Efficace (EME). À l'EME, l'entreprise produit à un niveau où le coût moyen par unité est le plus bas possible. Si la production augmente au-delà de ce point, le coût marginal, étant supérieur au coût moyen, fera augmenter le coût moyen.

En pratique, une entreprise cherchera à produire à un niveau où le coût marginal est égal au coût moyen, c'est-à-dire à l'EME, car c'est là que la production est la plus efficace en termes de coûts. Produire moins que l'EME signifie que l'entreprise n'est pas aussi efficace qu'elle pourrait l'être, tandis que produire plus signifie que l'entreprise rencontre des inefficacités et des coûts croissants.

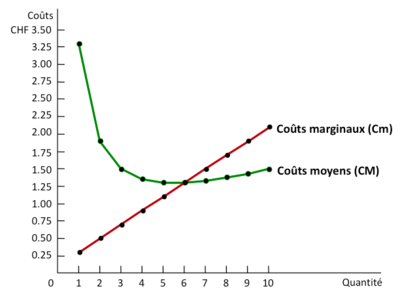

Le graphique affiche deux courbes distinctes : la courbe des coûts marginaux (Cm) en rouge et la courbe des coûts moyens (CM) en vert, tracées en fonction de la quantité produite, avec le coût exprimé en francs suisses (CHF).

La courbe des coûts moyens a la forme en U caractéristique dont nous avons discuté : elle décline rapidement au début, ce qui reflète les économies d'échelle et l'amortissement des coûts fixes sur un nombre croissant d'unités. Le point le plus bas de la courbe des coûts moyens représente l'Échelle Minimale Efficace (EME), où le coût moyen par unité est au minimum. Après ce point, la courbe commence à remonter, suggérant que les coûts moyens augmentent à mesure que la quantité produite continue d'augmenter, ce qui est probablement dû aux rendements marginaux décroissants et à l'augmentation des coûts variables moyens.

La courbe des coûts marginaux, quant à elle, commence au-dessus de la courbe des coûts moyens et croise cette dernière précisément au niveau de l'EME. Avant ce point de croisement, le coût marginal est inférieur au coût moyen, ce qui signifie que l'ajout d'unités supplémentaires de production réduit le coût moyen. Après le point de croisement, le coût marginal devient supérieur au coût moyen, indiquant que chaque unité supplémentaire coûte plus cher à produire que le coût moyen, entraînant ainsi une augmentation du coût moyen.

Ce graphique illustre l'important principe économique selon lequel le coût marginal coupe le coût moyen au niveau de son point minimum. Cela signifie que l'entreprise produit à l'EME, le niveau le plus efficace de production en termes de coûts. Si la production devait augmenter au-delà de ce point, elle deviendrait moins efficiente, comme le montre l'augmentation du coût moyen.

Pour une entreprise, comprendre la relation entre le coût marginal et le coût moyen est vital pour optimiser la production et maximiser les profits. La gestion de la production afin de maintenir les coûts aussi proches que possible du niveau de l'EME peut aider à assurer que l'entreprise fonctionne de manière efficiente et profitable.

Coût moyens (fixe et variable)

Le coût moyen fixe (CMF) et le coût moyen variable (CMV) sont deux composantes du coût moyen total (CMT). Chacun mesure une partie différente des coûts totaux par unité produite.

Coût Moyen Fixe (CMF): Le coût moyen fixe est calculé en divisant le coût fixe total (CF) par la quantité de biens produits (q). Les coûts fixes sont les coûts qui ne changent pas avec la quantité produite, tels que le loyer, les salaires des employés non directement impliqués dans la production, l'amortissement des machines, et les assurances. La formule du coût moyen fixe est :

À mesure que la production augmente, le CMF diminue parce que les coûts fixes sont répartis sur un plus grand nombre d'unités. Par exemple, si le loyer d'un atelier est de 1000 euros par mois, et que l'atelier produit 100 unités, le CMF est de 10 euros par unité. Si la production double pour atteindre 200 unités, le CMF tombe à 5 euros par unité.

Coût Moyen Variable (CMV): Le coût moyen variable est obtenu en divisant le coût variable total (CV) par la quantité produite. Les coûts variables varient directement avec la quantité produite et comprennent des éléments tels que les matières premières, l'énergie consommée pour la production, et les salaires des travailleurs de production payés à l'heure. La formule du coût moyen variable est :

Le CMV peut rester constant si les coûts par unité d'input restent les mêmes à mesure que la production augmente, mais il peut également varier en fonction de divers facteurs, tels que les économies sur les achats en gros ou l'épuisement des ressources nécessitant des inputs plus coûteux.

En somme, le coût moyen total, qui est la somme du CMF et du CMV, offre un aperçu du coût par unité pour l'ensemble de la production. Comprendre ces coûts moyens permet aux entreprises de déterminer le prix de vente de leurs produits, de planifier les niveaux de production, et d'effectuer des analyses de rentabilité.

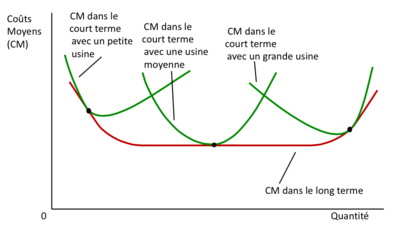

Plus en général

La productivité marginale est initialement croissante (spécialisation des travailleurs dans leurs tâches) et décroissante ensuite (car les facteurs fixes doivent être partagés par un nombre croissant de travailleurs)

Le graphique montre quatre courbes qui illustrent la relation entre les coûts de production et la quantité produite en unités.

- Coûts fixes moyens (CFM): Cette courbe grise montre que le coût fixe moyen diminue constamment avec l'augmentation de la quantité produite. Cela est dû au fait que les coûts fixes (tels que le loyer, les salaires des employés permanents, etc.) sont répartis sur un plus grand nombre d'unités, diminuant ainsi le coût attribué à chaque unité supplémentaire.

- Coûts variables moyens (CVM): La courbe marron représente les coûts variables moyens qui, dans ce cas, semblent initialement baisser avec l'augmentation de la production, atteignant un point minimum, puis augmentent à nouveau. Le point le plus bas représente le point où l'entreprise bénéficie pleinement des économies d'échelle sur les coûts variables. La remontée de la courbe suggère que, après un certain point, l'entreprise commence à subir des rendements marginaux décroissants, ce qui entraîne une augmentation des coûts variables par unité.

- Coût moyen (CM): La courbe verte indique le coût moyen total, qui est la somme du CFM et du CVM. Elle suit la forme classique en U, baissant initialement avec les économies d'échelle puis remontant en raison des rendements marginaux décroissants. Le point le plus bas de cette courbe indique l'efficience productive optimale de l'entreprise, où le coût moyen total par unité est le plus bas.

- Coûts marginaux (Cm): La courbe rouge trace le coût marginal, qui est le coût de production d'une unité supplémentaire. Cette courbe commence sous la courbe des coûts moyens, les croise au point le plus bas de la courbe des coûts moyens (qui est aussi l'Échelle Minimale Efficace ou EME), et continue ensuite à augmenter. Cela confirme la règle que lorsque le coût marginal est inférieur au coût moyen, le coût moyen est décroissant, et lorsque le coût marginal est supérieur au coût moyen, le coût moyen est croissant.

Les observations faites dans le graphique soutiennent les principes économiques standard selon lesquels le coût moyen atteint un minimum lorsque le coût marginal est égal au coût moyen. Le graphique illustre également clairement que le coût variable moyen est toujours inférieur au coût marginal après le point où les coûts moyens commencent à augmenter, ce qui est cohérent avec l'idée que le coût de production d'une unité supplémentaire est plus élevé à mesure que la production augmente. Cela indique également que le coût marginal rencontre le coût moyen au niveau de l'EME, où le coût moyen est au plus bas, ce qui est un point de référence important pour les décisions de production et de tarification.

Propriétés

Les trois propriétés suivantes sont des principes fondamentaux dans la théorie économique des fonctions de coûts, et elles ont des implications directes sur la gestion de la production et la stratégie de tarification des entreprises.

- Augmentation du coût marginal : La propriété selon laquelle le coût marginal finira par augmenter avec la quantité produite est liée à la loi des rendements marginaux décroissants. Cela signifie que, dans la plupart des processus de production, ajouter des unités supplémentaires de facteurs de production (comme le travail ou le capital) à un certain point entraînera une augmentation moins que proportionnelle de la production. Cela peut être dû à des contraintes de capacité, à des inefficacités croissantes ou à des coûts de ressources supplémentaires. Cette augmentation du coût marginal reflète le coût supplémentaire de production d'une unité additionnelle qui augmente au fur et à mesure que la quantité de production s'élève.

- Forme en U du coût moyen : La forme en U du coût moyen découle de la façon dont les coûts fixes et variables se comportent avec les changements dans la production. Lorsque la production commence, les coûts moyens diminuent car les coûts fixes sont répartis sur un nombre croissant d'unités. Cependant, une fois que la production atteint et dépasse l'EME, les coûts variables moyens commencent à peser plus lourdement dans le coût total, entraînant une augmentation du coût moyen. Si le coût marginal était toujours décroissant, cela signifierait que l'entreprise continuerait indéfiniment à gagner en efficacité avec chaque unité supplémentaire produite, ce qui n'est pas réaliste dans la plupart des cas à cause des contraintes physiques et pratiques.

- Intersection du coût marginal et du coût moyen : Le point où le coût marginal croise le coût moyen est critique car il représente le niveau de production où le coût moyen est au plus bas - l'Échelle Minimale Efficace (EME). À ce point, l'ajout d'unités supplémentaires commence à augmenter le coût moyen, ce qui signifie que l'entreprise perd en efficacité au-delà de ce point. Ce croisement est donc un indicateur pour l'entreprise qu'elle a atteint sa capacité de production la plus efficiente.

Ces propriétés ont des conséquences pratiques pour les entreprises. Pour maximiser la rentabilité, une entreprise doit chercher à opérer au niveau de l'EME, où elle peut minimiser les coûts moyens et ainsi maximiser les profits. Cela exige une compréhension approfondie de la structure des coûts et des capacités de production. En outre, les entreprises doivent être attentives à la gestion de la production pour ne pas dépasser le point où les coûts marginaux commencent à augmenter, ce qui pourrait entraîner une production inefficace et des pertes.

Résumé graphique

L'image ci-dessous est un résumé graphique représentant les relations entre le coût marginal (Cm), le coût moyen variable (CVM), le coût moyen total (CTM), et le coût variable (CV(q)), dans deux contextes différents : lorsque les coûts fixes (CF) sont nuls et lorsque les coûts fixes sont positifs.

L'image affichée est un résumé graphique représentant les relations entre le coût marginal (Cm), le coût moyen variable (CVM), le coût moyen total (CTM), et le coût variable (CV(q)), dans deux contextes différents : lorsque les coûts fixes (CF) sont nuls et lorsque les coûts fixes sont positifs.

Dans les deux graphiques, les courbes du coût marginal (ligne pointillée orange), du coût moyen variable (ligne marron) et du coût moyen total (ligne verte) présentent les caractéristiques typiques :

- Lorsque CF=0 :

- La courbe du coût moyen variable (CVM) et la courbe du coût moyen total (CTM) commencent au même point sur l'axe des ordonnées car il n'y a pas de coûts fixes à amortir sur les unités produites.

- Les courbes CVM et CTM diminuent initialement, atteignent un point minimum, puis commencent à augmenter, formant la classique courbe en U qui représente les économies, puis les déséconomies d'échelle.

- Le coût marginal (Cm) coupe les courbes CVM et CTM à leur point minimum, ce qui est le point d'inflexion où le coût marginal commence à être supérieur au coût moyen variable et total, indiquant que produire une unité supplémentaire devient plus coûteux que la moyenne.

- Lorsque CF>0 :

- La courbe CVM commence à partir de l'origine car les coûts variables sont nuls lorsque la production est nulle.

- La courbe CTM commence au-dessus de l'origine à la hauteur des coûts fixes positifs, car même sans production, l'entreprise doit couvrir ses coûts fixes.

- Comme précédemment, les courbes CVM et CTM montrent une diminution des coûts moyens avec l'augmentation initiale de la production, suivie d'une augmentation après avoir atteint un minimum.

- Le coût marginal suit la même trajectoire que dans le premier graphique, mais il est important de noter que le point où le Cm coupe le CTM est plus élevé sur l'axe des coûts à cause de la présence des coûts fixes.

Dans les deux cas, la position où le Cm coupe le CVM et le CTM est cruciale pour la prise de décision en matière de production. C'est là que l'entreprise ne bénéficie plus d'économies d'échelle et doit réévaluer l'augmentation de la production pour éviter des augmentations coûteuses des coûts moyens.