« The application of law » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 72 : | Ligne 72 : | ||

== Transitional provisions == | == Transitional provisions == | ||

Transitional law, often embodied in transitional provisions in legislation, plays a crucial role in the process of legislative change. These provisions are special rules of law, designed to be temporary and to facilitate the transition from old to new legislation. They take account of the need for individuals, businesses and government institutions to adjust and adapt to changes in legislation. These transitional provisions serve several essential purposes. Firstly, they provide a period for adaptation, allowing the parties concerned to gradually comply with the new requirements without major disruption. For example, if a new law imposes stricter environmental standards, transitional provisions could give companies time to comply with the new regulations, thus avoiding abrupt or destabilising economic consequences. | |||

Secondly, transitional provisions help to avoid or mitigate retroactive legal effects. They may, for example, specify that certain parts of the new law will not apply to situations already in progress on the date it comes into force. This can be crucial in areas such as tax or contract law, where parties need clarity about how new laws affect existing agreements or past tax obligations. In addition, transitional law can also be used to clarify situations where the provisions of old and new legislation might conflict, by establishing guidelines as to which law applies in specific circumstances. In this way, transitional law is an important tool for ensuring a smooth legislative transition. It helps to preserve legal stability and to ensure that legislative changes are implemented fairly and effectively, without unforeseen or disproportionate consequences. | |||

= | = The application of law in space = | ||

The application of law in space, often referred to as private international law or conflict of laws, is a complex area that deals with how laws are applied in situations involving foreign or cross-border elements. This area of law is becoming particularly relevant in an increasingly globalised world, where individuals, goods, services and capital easily cross national borders. The fundamental principle of private international law is to determine which jurisdiction has jurisdiction and which national law is applicable in cases involving several legal systems. For example, if a contract is signed in one country but is to be performed in another, private international law helps to resolve questions such as: which country has jurisdiction to hear the dispute? Which national law should be applied to govern the contract? | |||

To resolve these questions, lawyers rely on rules and principles to determine the applicable law. These rules include, but are not limited to, the law of the place where the contract was signed (lex loci contractus), the law of the place where the obligation is to be performed (lex loci solutionis) or the law of the place with which the case has the closest connection. In addition to national legislation, international conventions and treaties also play an important role in the application of the law in space. For example, the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction establishes procedures for the return of children abducted abroad. Applying the law across borders therefore requires a thorough understanding not only of national laws but also of international rules and conflict-of-law principles, thus ensuring that cross-border cases are handled fairly and consistently. | |||

=== | === Principle of the territoriality of law === | ||

The principle of the territoriality of law is a cornerstone of international law, affirming that a state's legislation is applicable only within its territorial borders. This concept underlines the sovereignty of each State to establish and enforce its own laws, thus recognising the autonomy and independence of nations in the management of their internal affairs. According to this principle, an individual or entity is subject to the laws of the country in which it is located. For example, an Italian citizen, when in Italy, is governed by Italian laws, but when travelling to Spain, becomes subject to Spanish laws. This rule is essential for legal coherence and predictability, ensuring that individuals know the laws to which they are subject and that states maintain their legislative authority within their territory. | |||

However, the territoriality of the law is not without its complexities and exceptions. In the field of international criminal law, for example, certain serious crimes such as war crimes and genocide can be prosecuted under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows a State to try such crimes regardless of where they were committed. This exception reflects an international recognition that certain acts are so damaging to world order that they cannot be limited by territorial borders. In addition, with the advent of digital technology and economic globalisation, certain laws, particularly those relating to cyber security, intellectual property and financial regulations, may have extraterritorial implications. For example, data protection laws, such as the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), can affect companies located outside the EU if they process data from EU citizens. | |||

The principle of territoriality of law, which states that any person or thing located in a country is governed by the law of that country, is a fundamental concept in international law. This principle reinforces the idea that each State has sovereignty over its territory, enabling it to exercise legislative authority over the persons, goods and activities located there. This implies that national laws are the primary norms governing conduct and relationships within a state's borders. However, there are notable exceptions to this principle, especially in the area of public law, where the exercise of public power is concerned. One of the most significant exceptions is that relating to diplomats. Foreign diplomats and the staff of diplomatic missions enjoy a special status under international public law, in particular in accordance with the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. | |||

Under this convention, diplomats are granted immunity from the criminal, civil and administrative jurisdiction of the host country. This means that they are not subject to the same laws as ordinary citizens or residents of the host country. For example, a diplomat accredited in France is exempt from French jurisdiction for most acts performed in the exercise of his or her official duties. This immunity is intended to ensure that diplomats can carry out their duties without fear of interference or persecution from the host country, thereby facilitating international relations and communication between states. This exception for diplomats illustrates how the principles of public international law can prevail over the principle of territoriality of law. It underlines the need to balance national sovereignty with the requirements of the harmonious functioning of international relations. | |||

=== | === Principle of the extraterritoriality of foreign diplomats === | ||

Le principe de l'exterritorialité des diplomates étrangers est une notion clé en droit international, jouant un rôle vital dans le maintien de relations diplomatiques efficaces et harmonieuses entre les nations. Selon ce principe, bien que les diplomates et les ambassades soient physiquement situés dans un pays hôte, ils ne sont pas soumis à la juridiction de ce pays, mais plutôt à celle de leur propre État. Cette règle est fondamentale pour assurer l'indépendance et la sécurité des missions diplomatiques. L'immunité diplomatique, qui est une application de ce principe, offre aux diplomates une protection contre les poursuites judiciaires dans le pays hôte. Cette immunité s'étend à la fois aux procédures pénales et civiles, garantissant ainsi que les diplomates peuvent exercer leurs fonctions sans crainte d'ingérence. Par exemple, si un diplomate commet une infraction routière dans le pays hôte, il ne peut être soumis aux mêmes procédures judiciaires que les citoyens locaux. | Le principe de l'exterritorialité des diplomates étrangers est une notion clé en droit international, jouant un rôle vital dans le maintien de relations diplomatiques efficaces et harmonieuses entre les nations. Selon ce principe, bien que les diplomates et les ambassades soient physiquement situés dans un pays hôte, ils ne sont pas soumis à la juridiction de ce pays, mais plutôt à celle de leur propre État. Cette règle est fondamentale pour assurer l'indépendance et la sécurité des missions diplomatiques. L'immunité diplomatique, qui est une application de ce principe, offre aux diplomates une protection contre les poursuites judiciaires dans le pays hôte. Cette immunité s'étend à la fois aux procédures pénales et civiles, garantissant ainsi que les diplomates peuvent exercer leurs fonctions sans crainte d'ingérence. Par exemple, si un diplomate commet une infraction routière dans le pays hôte, il ne peut être soumis aux mêmes procédures judiciaires que les citoyens locaux. | ||

Version du 13 décembre 2023 à 08:42

Based on a course by Victor Monnier[1][2][3]

Introduction to the Law : Key Concepts and Definitions ● The State: Functions, Structures and Political Regimes ● The different branches of law ● The sources of law ● The great formative traditions of law ● The elements of the legal relationship ● The application of law ● The implementation of a law ● The evolution of Switzerland from its origins to the 20th century ● Switzerland's domestic legal framework ● Switzerland's state structure, political system and neutrality ● The evolution of international relations from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century ● The universal organizations ● European organisations and their relations with Switzerland ● Categories and generations of fundamental rights ● The origins of fundamental rights ● Declarations of rights at the end of the 18th century ● Towards the construction of a universal conception of fundamental rights in the 20th century

The law is made up of legal rules, but reality is made up of factual situations. The rules of law include the laws, regulations and legal principles that form the legal framework. These rules are designed to guide and regulate the behaviour of individuals and organisations in society. On the other hand, "factual situations" refer to the real, concrete and practical circumstances that arise in everyday life. These situations can vary greatly and do not always lend themselves to a simple or straightforward interpretation of existing laws.

Applying the law therefore involves interpreting and adapting the rules of law to apply them to specific factual situations. This often requires legal judgement to balance legal texts with the practical, social and human realities of each case. Judges, lawyers and other legal professionals play a crucial role in this process, ensuring that justice is done fairly and in accordance with established legal principles.

The syllogism

The legal syllogism, or subsumption syllogism, is an essential method in legal reasoning, enabling a rule of law to be applied to a factual situation. There are several stages to this intellectual process. First, it involves identifying the relevant rule of law. This rule, often derived from a statute, regulation, legal principle or case law, establishes a general proposition applicable to various situations. Next, the process requires a careful analysis of the specific facts of the situation concerned. This stage is crucial because it involves a detailed and precise understanding of the actual circumstances involved. For example, in a contractual dispute, the facts may include the terms of the contract, the actions of the parties involved and the context in which the agreement was made. The final stage is subsumption, where the facts are subsumed under the rule of law. This stage determines how the general rule applies to the particular circumstances of the case. For example, if the law states that a contract is not valid without the consent of all the parties involved, and it is established in the facts that one of the parties did not give informed consent, the judge could conclude that the contract is invalid.

The legal syllogism is therefore more than just an intellectual exercise; it is a vital tool that ensures that legal decisions are taken logically, consistently and in accordance with legal standards. This methodology not only ensures that the rules of law are applied correctly, but also helps to maintain predictability and fairness in the administration of justice.

Application of the law over time

The applicability of a law depends on its entry into force and its continuing validity. Once a law has been passed through the legislative process, it is not immediately applicable. It comes into force on a date specified in the text of the law itself or on a date determined by another regulation. This period allows individuals and institutions to prepare to comply with the new law. On the other hand, the question of repeal is also essential in determining the applicability of a law. A law remains in force until it is explicitly repealed or replaced by new legislation. Repeal may be total, where the entire law is rendered inapplicable, or partial, where only certain segments of the law are annulled. In some legal systems, there is also the concept of obsolescence, where a law may become inapplicable if it is not used or is deemed obsolete. Even after a law has been repealed, certain transitional provisions may apply. These provisions are designed to manage the transition from the old to the new regulations and to deal with legal situations that existed under the old law. Thus, entry into force and repeal are key processes that determine how and when a law applies, ensuring the stability and predictability of the legal framework.

The adoption of a law in a bicameral legislative system, where there are two separate chambers (usually a lower and an upper house), requires the approval of both chambers. The process of passing legislation involves several key stages. Initially, a bill is proposed, often by a member of the government or parliament. This bill is then debated and examined in one of the chambers, where it may be amended. After this first stage of debate and approval, the bill moves on to the other chamber. Again, it is subject to debate, and further amendments may be made. For a law to be passed, it must be accepted in its final form by both houses. This often means a back-and-forth process between the chambers, especially if changes are made in one chamber that require further approval by the other. This process ensures a careful review and balanced consideration of the bill. Once both chambers have approved the text in the same version, the bill is considered adopted. Depending on the specific political system, the next step may be sanction or approval by the head of state (such as a president or monarch), after which the bill becomes law and is ready to enter into force on a specified date or according to the provisions of the law itself. This bicameral adoption process aims to ensure thorough scrutiny and diverse representation in the creation of legislation, reflecting the different interests and perspectives within society.

In the context of the Swiss legislative system, the enactment of a law is an essential process that follows its adoption. This stage marks the transition from a bill to an officially recognised and applicable law. The enactment process in Switzerland is distinguished by its incorporation of direct democracy and reflects the country's fundamental democratic principles. On the one hand, when important laws, such as constitutional amendments or those subject to mandatory referendum, are at stake, promulgation follows a particular procedure. After a proposed law has been approved by the Swiss people in a referendum, the Federal Council, acting as the executive body, officially validates the result of the referendum. This happens, for example, in the case of constitutional amendments where the Swiss people play a direct role in decision-making. Validation by the Federal Council marks the promulgation of the law, indicating that it is ready for implementation. On the other hand, for ordinary laws that do not require a referendum, promulgation occurs after the expiry of a referendum deadline. During this period, citizens have the opportunity to challenge the law by collecting enough signatures to request a referendum. If no referendum is requested by the end of the deadline, the Federal Chancellery, acting as the central administrative body, officially promulgates the law. This stage confirms that the law has been adopted in accordance with democratic processes and that there are no major legal obstacles to its coming into force. Promulgation in Switzerland therefore illustrates a unique blend of representative and direct democracy, ensuring that laws are not only passed by elected representatives but also, in some cases, directly approved by the people. This approach enhances the legitimacy and acceptance of laws, ensuring that the Swiss legal framework is in harmony with the will of its citizens.

The publication of a law in the Official Compendium is an essential step in the legislative process, particularly in the context of the Swiss legal system. The main purpose of publication is to make the law accessible and known to everyone, which is a fundamental principle of law: for a law to be applicable, it must be publicly accessible and known to the people it affects. The Official Compendium, as a chronological publication, contains legislative texts in the order in which they were enacted. This publication not only disseminates legislative information to the general public, but also serves as an official reference for legal professionals, government institutions and citizens. Publication in the Official Compendium guarantees the transparency of the legislative process and enables all players in society to follow developments in the legal framework. By making laws easily accessible, the Official Compendium helps to ensure that citizens and legal entities are informed of their rights and obligations. This is crucial to the principle of legality, which stipulates that no one is supposed to ignore the law. The official publication of laws therefore plays a fundamental role in maintaining legal order and promoting justice and predictability in society.

The Swiss legal system has two official publications that play a crucial role in the dissemination and organisation of federal law: the Official Compendium (OR) and the Systematic Compendium (SC). These two collections have distinct characteristics and objectives, reflecting the different ways in which the law can be consulted and analysed. The Official Compendium, abbreviated RO, is a chronological publication. It brings together legal texts in the order in which they were promulgated. This means that laws, ordinances and other legal texts are published in the order in which they came into force. This chronological approach is particularly useful for tracking legislative developments and understanding the historical context in which a law was passed. The RO is therefore essential for legal professionals and researchers interested in legislative history and the sequence of legislative changes. The Recueil systématique, known by the acronym RS, is organised by subject. Instead of following chronological order, the RS groups legal texts by subject area or theme, such as family law, commercial law or criminal law. This thematic organisation makes it easier to find and access legal texts for people seeking specific information on a particular subject. The RS is therefore a valuable tool for legal practitioners, students and anyone who needs to consult the relevant laws in a specific field quickly and efficiently. These two collections offer a comprehensive view of Swiss federal law, each from a different angle. The RO provides a historical and sequential overview, while the RS offers an organised and thematic perspective. Together, they ensure that Swiss federal law is accessible, comprehensible and usable for a wide range of users, from legal professionals to ordinary citizens.

The Swiss Federal Gazette plays a distinct and complementary role in the legislative publication system. As a weekly publication available in the country's three official languages (German, French and Italian), its main objective is to provide up-to-date information on legislative and government activities. Unlike the Official Compendium, which focuses on the publication of enacted laws, the Federal Gazette concentrates on the initial and intermediate phases of the legislative process. It provides information on new laws passed by Parliament, with an emphasis on the referendum deadline. This is crucial in the Swiss democratic system, where citizens have the opportunity to request a referendum on recently adopted laws. Publication in the Federal Gazette triggers the start of this referendum deadline. In addition to notifying the public and stakeholders about referendum deadlines, the Federal Gazette also serves as a means of communication to inform parliamentarians and the public about current bills and legislative debates. It may include reports, press releases, government announcements and other information relevant to the legislative process. The Federal Gazette is therefore an essential tool for government transparency and democratic participation in Switzerland. It enables citizens and parliamentarians to keep abreast of legislative developments and facilitates the exercise of democratic rights, such as referendums, by ensuring that the necessary information is widely available and accessible.

Coming into force of the law and its repeal

The law comes into force

The entry into force of a law is the point at which it becomes binding and applicable. In the Swiss legal system, the process by which a law comes into force is generally defined either by the legislative text itself or by a decision of the Federal Council. When a law is passed by Parliament, it may specify directly in its text the date on which it will come into force. This is common practice for laws whose application requires advance preparation, allowing individuals, businesses and government bodies to adapt to new legal requirements. In cases where the law does not explicitly state when it will come into force, the Federal Council, the executive body of the Swiss federal government, is responsible for setting the date. The Federal Council takes this decision taking into account various factors, such as the need to allow sufficient time for implementation, the practical implications of the law, and coordination with other legislation or policies in force. The entry into force of a law is an important milestone, as it is at this point that the legal provisions become binding and the legal consequences of non-compliance apply. This underlines the importance of communicating and publishing laws, such as through the Federal Gazette and the Official Compendium, to ensure that all stakeholders are informed and ready to comply with new regulations. By setting the date of entry into force, the Federal Council plays a key role in ensuring a smooth transition to the application of the new legal standards.

The process of creating and applying a law in legal systems such as Switzerland's is a structured and meticulous one, beginning with the adoption of the law by Parliament. This first phase sees a bill debated and amended by elected representatives in a bicameral context, where two chambers scrutinise the content and relevance of the proposed legislation. A concrete example might be the adoption of a new environmental law, where Parliament discusses its implications and adjusts its provisions to address environmental and economic concerns. Once Parliament has adopted the law, it is promulgated. This formal step, often carried out by the Federal Council in Switzerland, is an official recognition of the law. Promulgation is a signal that the law has met all the necessary criteria and is ready to be communicated to the public. For example, a law enacted on road safety would be officially announced, indicating its importance and imminent validity. Publication follows enactment. The law is made available in an official compendium, enabling all citizens and interested parties to become acquainted with it. Publication ensures that the law is transparent and accessible, as in the case of new tax regulations, where the precise details and implications for citizens and businesses must be clearly communicated. Finally, entry into force is the stage at which the law becomes applicable. The date of application may be specified in the text of the law or determined by the Federal Council. This stage marks the point at which the provisions of the law must be respected and followed. Take the example of a new data protection law: once it has come into force, companies and organisations must comply with the new standards for managing personal data. This process, from adoption to entry into force, ensures that each law is carefully examined, validated and communicated, reflecting democratic and legal principles, while guaranteeing that citizens are well informed and prepared for future legislative changes.

Repeal of the law

Repeal, in the legal context, is a process by which a legislative act is annulled or suppressed by a new act of the same or higher rank. The act may be repealed in its entirety or only in part. Once repealed, the legislative act ceases to produce legal effects, which means that it is no longer applicable and can no longer be invoked in judicial decisions or legal transactions.

This concept of repeal is fundamental in law and is encapsulated in the Latin adage "Lex posterior derogat priori", which translates as "the later law derogates from the earlier law". This means that in the event of a conflict between two laws, the more recent law generally prevails over the earlier law. This adage is a key principle of the hierarchy of norms in law, ensuring that the legal system remains coherent and up to date. A concrete example of repeal might be the introduction of new privacy legislation that replaces and overrides an earlier law on the same subject. The new law, once enacted and in force, would render the previous law obsolete and inapplicable.

Repeal is an important tool for legislators, ensuring that the body of law remains adapted to changes in society, technological change and new ethical and moral standards. It also makes it possible to repeal laws that have become redundant or have been deemed inappropriate or ineffective. In short, repeal is essential to maintain a dynamic and responsive legal system, capable of responding to the changing needs of society.

The principle of non-retroactivity of the law

The principle you describe is closely linked to the notion of non-retroactivity of laws, a fundamental concept in law. According to this principle, a new legal norm must not retroactively affect situations that arose under the aegis of a previous rule. This means that a law cannot be applied to situations, acts or facts that occurred before it came into force.

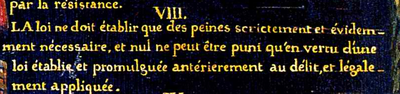

This principle of non-retroactivity is rooted in the declarations of fundamental rights dating back to the 18th century. An emblematic example is Article 9 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 12 June 1776, as well as Article 8 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 26 August 1789. These fundamental texts, which stemmed from the beginnings of the modern era of human rights, laid the foundations for legal protection against the retroactivity of laws, particularly in the criminal field. Article 8 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted at the time of the French Revolution, clearly states that only necessary penalties can be established and that a person can only be punished under a law that was in force at the time the act was committed. This provision is intended to ensure fair justice and protect citizens against the arbitrary application of the law. Similarly, Article 9 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, a precursor to the American Constitution, reflects these same values of justice and legal predictability. These principles were revolutionary at the time and have greatly influenced the development of modern legal systems. The principle of non-retroactivity, as formulated in these historic documents, is a pillar of the rule of law. It ensures that individuals are not subject to laws that did not exist at the time of their actions, thereby providing protection against ex post facto legal changes that could alter the legal consequences of their actions. This principle strengthens confidence in the legal system, as it assures citizens that laws will not be applied arbitrarily or unfairly.

This principle is essential to guarantee legal certainty and the predictability of the law. It protects individuals against the retroactive application of legislative changes, particularly in cases where such application could be prejudicial or unfair. In practice, this ensures that individuals cannot be held liable under a law that did not exist at the time the action or event occurred. The non-retroactivity of laws is a pillar of justice and fairness, ensuring that individuals are not penalised by unpredictable and sudden legislative changes. This principle helps to maintain confidence in the legal system and to protect the fundamental rights of individuals.

Article 2 of the Swiss Criminal Code is a perfect example of how to implement the principle of non-retroactivity of laws, while incorporating an important exception in favour of the accused. This article sets out the rules for applying the Code in terms of temporality and jurisdiction.

The first part of the article stipulates that anyone who commits a felony or misdemeanour after the entry into force of the Penal Code shall be judged in accordance with its provisions. This directly reflects the principle of non-retroactivity, stating that actions are assessed according to the law in force at the time they were committed. This ensures that individuals will not be judged according to laws that did not exist at the time of their actions, thus ensuring a fair and predictable application of the law. The second part of the article introduces a notable exception to the principle of non-retroactivity, known as "milder criminal law". Under this provision, if a crime or misdemeanour was committed before the entry into force of the Criminal Code but the perpetrator is not brought to trial until after that date, and the provisions of the new Code are more favourable to the accused than the previous law, then the new Code applies. This exception is an example of the tendency of legal systems to favour interpretations and laws that benefit the accused, an approach that reflects the principle of the presumption of innocence and the desire to avoid unjustly harsh penalties. Article 2 of the Swiss Criminal Code illustrates the complexity and nuance of the principle of non-retroactivity, balancing the need for predictable justice with the principles of fairness and equity for the accused.

There is an important nuance in the application of the principle of non-retroactivity in criminal law, particularly in relation to the doctrine of 'milder criminal law'. This doctrine constitutes a notable exception to the general rule of non-retroactivity, as you mentioned in the context of Article 2 of the Swiss Criminal Code. According to this doctrine, if a new criminal law is more lenient or more favourable to the accused than the old law in force at the time the offence was committed, the new law can be applied retroactively. This exception is based on the principle of fair justice and aims to ensure that the accused benefits from the most lenient legislation possible. This approach reflects an orientation towards protecting the rights of the accused in the legal system. It is based on the idea that justice must not only be fair and predictable, but also adapted to avoid excessively harsh punishments. In practice, this means that if a law is changed between the time of the offence and the time of sentencing, and this change is advantageous to the accused, the change must be applied. This derogation from non-retroactivity demonstrates the adaptability and sensitivity of criminal law to the fundamental principles of human rights. It is essential to maintain a balance between the strict application of the law and the need for justice to take account of changing circumstances and evolving social and legal norms.

Article 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights embodies a key principle in criminal law, that of the legality of offences and penalties. This principle states that no one shall be held guilty of any criminal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offence under national or international law at the time when it was committed. This provision plays a crucial role in protecting individual rights and preserving fair justice. This principle ensures that laws are formulated in a clear and accessible way, enabling citizens to understand the legal consequences of their actions. For example, if an individual commits an act that is not defined as a crime at the time of its commission, they cannot be retroactively prosecuted if that act is subsequently criminalised. This approach protects citizens from arbitrary or unpredictable changes in the law, ensuring that no one is penalised for acts that were not illegal at the time they were carried out.

Article 7 also reflects the commitment of democratic systems to the non-retroactivity of criminal laws. It prevents governments from applying new criminal laws to past actions, a practice that would not only be unjust but also contrary to fundamental principles of justice. This protection against the retroactive application of criminal laws is essential for public confidence in the legal system and for the foreseeability of the law. Finally, this provision of the European Convention on Human Rights serves as a safeguard against the abuse of legislative power. It prevents states from punishing individuals for behaviour that was not considered criminal at the time it was committed, thereby protecting citizens against arbitrariness and abuse of power. Article 7 not only guarantees the clarity and precision of criminal laws; it is also a pillar of the protection of fundamental rights, ensuring that justice is administered in a fair and predictable manner.

Transitional provisions

Transitional law, often embodied in transitional provisions in legislation, plays a crucial role in the process of legislative change. These provisions are special rules of law, designed to be temporary and to facilitate the transition from old to new legislation. They take account of the need for individuals, businesses and government institutions to adjust and adapt to changes in legislation. These transitional provisions serve several essential purposes. Firstly, they provide a period for adaptation, allowing the parties concerned to gradually comply with the new requirements without major disruption. For example, if a new law imposes stricter environmental standards, transitional provisions could give companies time to comply with the new regulations, thus avoiding abrupt or destabilising economic consequences.

Secondly, transitional provisions help to avoid or mitigate retroactive legal effects. They may, for example, specify that certain parts of the new law will not apply to situations already in progress on the date it comes into force. This can be crucial in areas such as tax or contract law, where parties need clarity about how new laws affect existing agreements or past tax obligations. In addition, transitional law can also be used to clarify situations where the provisions of old and new legislation might conflict, by establishing guidelines as to which law applies in specific circumstances. In this way, transitional law is an important tool for ensuring a smooth legislative transition. It helps to preserve legal stability and to ensure that legislative changes are implemented fairly and effectively, without unforeseen or disproportionate consequences.

The application of law in space

The application of law in space, often referred to as private international law or conflict of laws, is a complex area that deals with how laws are applied in situations involving foreign or cross-border elements. This area of law is becoming particularly relevant in an increasingly globalised world, where individuals, goods, services and capital easily cross national borders. The fundamental principle of private international law is to determine which jurisdiction has jurisdiction and which national law is applicable in cases involving several legal systems. For example, if a contract is signed in one country but is to be performed in another, private international law helps to resolve questions such as: which country has jurisdiction to hear the dispute? Which national law should be applied to govern the contract?

To resolve these questions, lawyers rely on rules and principles to determine the applicable law. These rules include, but are not limited to, the law of the place where the contract was signed (lex loci contractus), the law of the place where the obligation is to be performed (lex loci solutionis) or the law of the place with which the case has the closest connection. In addition to national legislation, international conventions and treaties also play an important role in the application of the law in space. For example, the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction establishes procedures for the return of children abducted abroad. Applying the law across borders therefore requires a thorough understanding not only of national laws but also of international rules and conflict-of-law principles, thus ensuring that cross-border cases are handled fairly and consistently.

Principle of the territoriality of law

The principle of the territoriality of law is a cornerstone of international law, affirming that a state's legislation is applicable only within its territorial borders. This concept underlines the sovereignty of each State to establish and enforce its own laws, thus recognising the autonomy and independence of nations in the management of their internal affairs. According to this principle, an individual or entity is subject to the laws of the country in which it is located. For example, an Italian citizen, when in Italy, is governed by Italian laws, but when travelling to Spain, becomes subject to Spanish laws. This rule is essential for legal coherence and predictability, ensuring that individuals know the laws to which they are subject and that states maintain their legislative authority within their territory.

However, the territoriality of the law is not without its complexities and exceptions. In the field of international criminal law, for example, certain serious crimes such as war crimes and genocide can be prosecuted under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows a State to try such crimes regardless of where they were committed. This exception reflects an international recognition that certain acts are so damaging to world order that they cannot be limited by territorial borders. In addition, with the advent of digital technology and economic globalisation, certain laws, particularly those relating to cyber security, intellectual property and financial regulations, may have extraterritorial implications. For example, data protection laws, such as the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), can affect companies located outside the EU if they process data from EU citizens.

The principle of territoriality of law, which states that any person or thing located in a country is governed by the law of that country, is a fundamental concept in international law. This principle reinforces the idea that each State has sovereignty over its territory, enabling it to exercise legislative authority over the persons, goods and activities located there. This implies that national laws are the primary norms governing conduct and relationships within a state's borders. However, there are notable exceptions to this principle, especially in the area of public law, where the exercise of public power is concerned. One of the most significant exceptions is that relating to diplomats. Foreign diplomats and the staff of diplomatic missions enjoy a special status under international public law, in particular in accordance with the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations.

Under this convention, diplomats are granted immunity from the criminal, civil and administrative jurisdiction of the host country. This means that they are not subject to the same laws as ordinary citizens or residents of the host country. For example, a diplomat accredited in France is exempt from French jurisdiction for most acts performed in the exercise of his or her official duties. This immunity is intended to ensure that diplomats can carry out their duties without fear of interference or persecution from the host country, thereby facilitating international relations and communication between states. This exception for diplomats illustrates how the principles of public international law can prevail over the principle of territoriality of law. It underlines the need to balance national sovereignty with the requirements of the harmonious functioning of international relations.

Principle of the extraterritoriality of foreign diplomats

Le principe de l'exterritorialité des diplomates étrangers est une notion clé en droit international, jouant un rôle vital dans le maintien de relations diplomatiques efficaces et harmonieuses entre les nations. Selon ce principe, bien que les diplomates et les ambassades soient physiquement situés dans un pays hôte, ils ne sont pas soumis à la juridiction de ce pays, mais plutôt à celle de leur propre État. Cette règle est fondamentale pour assurer l'indépendance et la sécurité des missions diplomatiques. L'immunité diplomatique, qui est une application de ce principe, offre aux diplomates une protection contre les poursuites judiciaires dans le pays hôte. Cette immunité s'étend à la fois aux procédures pénales et civiles, garantissant ainsi que les diplomates peuvent exercer leurs fonctions sans crainte d'ingérence. Par exemple, si un diplomate commet une infraction routière dans le pays hôte, il ne peut être soumis aux mêmes procédures judiciaires que les citoyens locaux.

En outre, l'exterritorialité confère aux locaux des ambassades une sorte de "territoire souverain" de l'État qu'ils représentent. Cela signifie que les locaux de l'ambassade ne peuvent être fouillés ou saisis par les autorités du pays hôte sans le consentement de l'ambassade, offrant ainsi un refuge sûr pour les diplomates et leur permettant de mener des affaires sensibles sans ingérence extérieure. Il est important de noter que, bien que bénéficiant de l'exterritorialité, les diplomates sont toujours tenus de respecter les lois de leur propre pays. Ils sont également encouragés à respecter les lois et règlements du pays hôte, conformément aux principes de la Convention de Vienne sur les relations diplomatiques de 1961. Cette convention établit les normes internationales régissant les activités diplomatiques et vise à promouvoir la coopération internationale dans un cadre respectueux et sécurisé. Cette approche de l'exterritorialité est cruciale pour le fonctionnement des relations internationales. Elle garantit que les diplomates peuvent effectuer leurs tâches officielles efficacement, tout en maintenant le respect mutuel et la souveraineté entre les pays. En équilibrant les besoins de la souveraineté nationale et de la coopération internationale, le principe de l'exterritorialité contribue de manière significative à la stabilité et à l'efficacité des relations diplomatiques à travers le monde.

Le principe de l'exterritorialité s'applique effectivement dans le contexte de l'aviation, où un avion est considéré comme une extension du territoire de l'État dont il porte le pavillon. Cela signifie que, même lorsqu'un avion est en vol international ou se trouve sur le territoire d'un autre pays, il est soumis aux lois et à la juridiction de l'État sous lequel il est enregistré. Ce concept est une extension de la souveraineté nationale dans l'espace aérien et est essentiel pour la régulation et la gestion du trafic aérien international. Lorsqu'un avion enregistré dans un pays particulier traverse l'espace aérien international ou atterrit dans un autre pays, les lois du pays d'origine de l'avion continuent de s'appliquer à bord. Par exemple, si un incident se produit à bord d'un avion enregistré en France, que ce soit dans l'espace aérien international ou sur le sol d'un autre pays, il est généralement traité selon le droit français. Ce principe assure une certaine cohérence et uniformité dans l'application des lois à bord des aéronefs, ce qui est crucial étant donné la nature internationale du transport aérien. Cette règle est cependant soumise à certaines limitations et exceptions. Dans des circonstances particulières, comme les crimes graves commis à bord ou les situations qui menacent la sécurité du pays où l'avion atterrit, les autorités locales peuvent intervenir et appliquer leur propre législation. De plus, des accords internationaux tels que la Convention de Tokyo de 1963 et la Convention de Montréal de 1971 établissent des règles spécifiques concernant les juridictions et les lois applicables à bord des aéronefs.

L’interprétation du droit

L'interprétation des règles de droit est un processus intellectuel complexe et nuancé, essentiel pour déterminer et préciser le sens véritable des textes législatifs et réglementaires. Cette pratique est indispensable dans le domaine juridique, car les lois ne sont pas toujours explicites ou exhaustives dans leur formulation, laissant place à des interprétations diverses.

Dans le cadre de l'interprétation juridique, plusieurs approches peuvent être adoptées. Une méthode courante est l'interprétation littérale, où l'accent est mis sur le sens ordinaire des mots utilisés dans la loi. Par exemple, si une loi interdit de "conduire à grande vitesse", l'interprétation littérale cherchera à définir ce que signifie exactement "grande vitesse" en se basant sur le langage ordinaire. Cependant, l'interprétation littérale peut ne pas toujours suffire ou être appropriée. Par conséquent, les juristes se tournent souvent vers une interprétation téléologique, qui cherche à comprendre l'objectif ou l'intention derrière la loi. Par exemple, dans le cas de législations environnementales, l'interprétation téléologique considère l'objectif global de protection de l'environnement pour guider l'application de la loi.

L'interprétation systématique est une autre méthode importante, qui examine la loi dans le contexte du système juridique global. Cela implique de considérer la manière dont une loi spécifique s'intègre avec d'autres lois ou avec des principes juridiques établis. En outre, l'interprétation historique peut être utilisée, en particulier dans des cas complexes. Cette approche prend en compte les circonstances historiques et les débats législatifs qui ont précédé l'adoption de la loi, offrant ainsi un aperçu des intentions des législateurs. Les juges jouent un rôle crucial dans l'interprétation des lois, en particulier lorsqu'ils sont confrontés à des affaires où la législation doit être appliquée à des situations spécifiques et parfois inédites. Leur interprétation a un impact direct sur l'application de la justice, illustrant ainsi l'importance vitale de cette pratique dans le maintien de l'ordre juridique et dans la réalisation de la justice équitable dans la société.

La réalité de l'application du droit dans la vie en société souligne effectivement la rareté des situations où la loi coïncide parfaitement avec les faits. Cette observation met en lumière le besoin constant d'interpréter les règles de droit. Les textes législatifs, malgré leur formulation soignée, ne peuvent pas prévoir toutes les nuances et complexités des situations réelles. En effet, les faits de la vie en société sont extrêmement diversifiés, et chaque cas peut présenter des particularités uniques qui ne sont pas explicitement couvertes par les lois existantes. Cette diversité des situations rend l'interprétation non seulement inévitable, mais aussi essentielle pour assurer une application juste et efficace de la loi. Par exemple, dans le cadre d'un litige contractuel, les termes d'un contrat peuvent sembler clairs, mais leur application à un cas spécifique peut nécessiter une interprétation approfondie pour comprendre les intentions des parties et le contexte dans lequel l'accord a été conclu. L'interprétation devient également cruciale lorsqu'une loi est vague ou générale dans sa formulation. Les juges, en interprétant la loi, cherchent à lui donner un sens qui est à la fois fidèle à l'intention du législateur et adapté aux circonstances particulières du cas en question. Cette tâche d'interprétation exige une compréhension approfondie non seulement de la loi elle-même, mais aussi des principes juridiques plus larges et du contexte social et historique. En définitive, l'interprétation est une composante indispensable du système juridique, permettant de combler l'écart entre la lettre de la loi et la réalité complexe et changeante de la vie en société. Elle permet d'assurer que la loi reste pertinente, équitable et adaptée aux besoins et aux défis divers de la société.

L'interprétation du droit est une tâche complexe qui implique divers acteurs, chacun apportant une perspective et une expertise spécifiques. Au cœur de ce processus se trouvent les juges, qui jouent un rôle essentiel en tant qu'interprètes principaux du droit. Dans leurs fonctions judiciaires, ils analysent et appliquent les lois aux cas qui leur sont soumis. Leurs décisions ne se limitent pas à résoudre des litiges individuels ; elles établissent souvent des précédents qui guident l'interprétation future des lois. Par exemple, les décisions de la Cour suprême dans de nombreux pays ont un impact durable sur la compréhension et l'application du droit. Parallèlement, la doctrine, qui englobe les travaux des universitaires, des avocats et des juristes, joue un rôle consultatif mais influent dans l'interprétation du droit. Bien que leurs analyses et commentaires ne soient pas juridiquement contraignants, ils offrent des perspectives approfondies qui peuvent éclairer et influencer le raisonnement juridique. Les articles universitaires ou les commentaires d'experts sur une législation spécifique, par exemple, peuvent fournir des arguments et des interprétations qui sont ensuite utilisés par les juges dans leurs décisions. Enfin, le législateur, l'entité responsable de la création des lois, détient le pouvoir d'interprétation authentique. Lorsque le législateur intervient pour clarifier ou modifier une loi, cette intervention est considérée comme définitive, car elle provient de l'autorité qui a créé la loi. Cette forme d'interprétation peut être nécessaire lorsque les lois sont ambiguës ou incomplètes. Par exemple, un parlement peut adopter une nouvelle législation ou un amendement pour clarifier une disposition légale précédemment vague ou sujette à diverses interprétations. Chacun de ces acteurs - juges, doctrine et législateur - contribue de manière unique à l'interprétation et à l'application du droit. Leur interaction et leur influence mutuelle assurent que le droit reste dynamique, adaptatif et pertinent face aux défis changeants et aux complexités de la société moderne.

Les lacunes de la loi

Les lacunes de la loi sont un phénomène inévitable dans tout système juridique, résultant de la difficulté, voire de l'impossibilité, pour le législateur de prévoir toutes les situations possibles au moment de la rédaction des lois. Ces lacunes se manifestent lorsque des situations réelles se présentent qui ne sont pas explicitement couvertes par la législation existante, créant ainsi des zones d'incertitude juridique. Il y a deux types de lacunes dans le droit positif : les lacunes volontaires et les lacunes involontaires. Les lacunes volontaires surviennent lorsque le législateur choisit délibérément de ne pas réglementer une certaine matière ou situation, laissant cette question à la discrétion des juges ou à d'autres mécanismes de résolution. Par exemple, dans certains domaines du droit, le législateur peut intentionnellement laisser des termes vagues ou des concepts ouverts à interprétation pour permettre une certaine souplesse dans l'application de la loi.

En revanche, les lacunes involontaires se produisent lorsque le législateur omet, sans intention particulière, de traiter une question ou une situation qui n'a pas été envisagée lors de la rédaction de la loi. Ces lacunes peuvent devenir apparentes avec l'évolution de la société, l'émergence de nouvelles technologies ou des situations inédites. Par exemple, l'avènement d'Internet et des médias sociaux a créé de nombreux défis juridiques qui n'étaient pas anticipés par les lois traditionnelles sur la communication et la vie privée. Lorsque de telles lacunes se manifestent, il revient souvent aux juges de les combler en interprétant la loi existante de manière à l'appliquer à la situation inédite. Ce processus peut impliquer l'extension des principes existants à de nouvelles circonstances ou l'application d'analogies avec des situations juridiquement réglementées. Dans certains cas, la reconnaissance d'une lacune peut conduire le législateur à intervenir pour combler cette lacune par de nouvelles lois ou amendements.Au moment de la création d‘une loi, le législateur ne peut pas prévoir tous les cas réels qui peuvent survenir. Dans le cas où la situation n'est pas mentionnée par celui-ci, on parle d’une lacune dans le droit positif. Cette lacune peut être volontaire ou non.

L'interprétation du droit en présence de lacunes, c'est-à-dire lorsque les règles existantes ne couvrent pas une situation donnée, requiert l'emploi de méthodes d'interprétation spécifiques. Ces méthodes visent à combler les vides juridiques et à fournir des solutions adaptées aux cas qui ne sont pas explicitement traités par la législation existante. Une des méthodes couramment utilisées est l'interprétation par analogie. Cette approche consiste à appliquer à la situation non couverte une règle existante qui régit des cas similaires ou qui partage des principes fondamentaux avec la situation en question. Par exemple, si une nouvelle forme de contrat commercial émerge qui n'est pas explicitement couverte par le droit des contrats existant, un juge peut chercher des règles applicables à des formes de contrats similaires et les appliquer par analogie. Une autre méthode est l'interprétation téléologique, qui se concentre sur l'intention ou l'objectif du législateur. Cette méthode cherche à déterminer le but sous-jacent des lois existantes et à étendre leur application de manière à réaliser cet objectif dans le cas non couvert. Par exemple, si une loi vise à protéger la vie privée en ligne, cette intention peut être utilisée pour interpréter la loi de manière à couvrir les nouveaux scénarios technologiques non prévus explicitement dans le texte de loi.

Dans certains systèmes juridiques, les principes généraux du droit jouent également un rôle important dans le comblement des lacunes. Ces principes, qui représentent les fondements conceptuels du système juridique, peuvent servir de guide pour l'interprétation et la prise de décision dans des situations non réglementées explicitement par la loi. Enfin, dans certains cas, les lacunes peuvent inciter le législateur à intervenir et à créer de nouvelles lois ou à modifier les lois existantes pour traiter explicitement la situation non couverte. Cela est souvent le cas dans des domaines en rapide évolution, comme la technologie ou l'environnement, où de nouveaux défis émergent régulièrement. Dans l'ensemble, l'interprétation du droit en présence de lacunes exige une combinaison de créativité, de rigueur analytique et d'une compréhension approfondie des principes juridiques, afin d'assurer que les décisions prises sont justes, raisonnables et conformes à l'esprit du système juridique.

La lacune intra legem (dans la loi)

La notion de lacune intra legem fait référence à une situation particulière où une loi, intentionnellement ou non, laisse un espace de discrétion au juge, souvent en raison de l'utilisation de termes vagues, inconnus ou indéterminés. Cette forme de lacune se distingue par le fait que le législateur, reconnaissant la complexité et la diversité des situations réelles, laisse délibérément certains aspects de la loi ouverts à interprétation. Dans ces cas, le législateur s'en remet au pouvoir d'appréciation du juge pour déterminer la manière dont la loi devrait être appliquée dans des situations spécifiques. Par exemple, une loi peut utiliser des termes comme "raisonnable", "équitable" ou "dans l'intérêt public", qui ne sont pas strictement définis. Ces termes confèrent au juge une certaine latitude pour interpréter la loi en fonction des circonstances particulières de chaque affaire.

Cette approche reconnaît que le législateur ne peut pas prévoir toutes les situations particulières et les nuances qui peuvent survenir. En laissant certains termes ouverts à interprétation, le législateur permet aux juges, qui sont confrontés directement aux faits spécifiques de chaque cas, d'utiliser leur expertise et leur jugement pour appliquer la loi de la manière la plus juste et appropriée. La lacune intra legem est donc un élément important du droit qui reflète la flexibilité nécessaire dans l'application des lois. Elle permet au système juridique de s'adapter aux cas individuels tout en restant fidèle aux intentions et aux objectifs généraux du législateur. Cette flexibilité est cruciale pour garantir que la justice est non seulement rendue conformément à la lettre de la loi, mais aussi selon son esprit.

L'article 44 du Code des obligations suisse est un exemple illustratif du renvoi au juge par le législateur, où certaines formules sont utilisées pour conférer au juge un pouvoir discrétionnaire dans l'application de la loi. Cet article montre comment le législateur peut intentionnellement laisser une marge de manœuvre au juge pour tenir compte des circonstances particulières de chaque cas.

Dans le premier paragraphe de l'article 44, le juge se voit octroyer le pouvoir de réduire les dommages-intérêts, ou même de ne pas en accorder, selon des critères spécifiques. Ceux-ci incluent la situation où la partie lésée a consenti à la lésion ou lorsque des faits dont elle est responsable ont contribué au dommage. Cette disposition permet au juge de tenir compte des nuances et des responsabilités partagées dans les situations de dommages. Le deuxième paragraphe va plus loin en permettant au juge de réduire équitablement les dommages-intérêts dans les cas où le préjudice n'a pas été causé intentionnellement ou par grave négligence, et où la réparation complète exposerait le débiteur à des difficultés. Cette clause donne au juge la latitude nécessaire pour évaluer les conséquences économiques de la réparation sur le débiteur et ajuster les dommages-intérêts en conséquence.

Ces dispositions illustrent la reconnaissance par le législateur de la complexité des situations juridiques et de la nécessité de permettre une certaine flexibilité dans leur résolution. En confiant au juge le soin d'interpréter et d'appliquer la loi de manière adaptée à chaque situation, le Code des obligations suisse témoigne d'une approche du droit qui valorise l'équité et la prise en compte des circonstances individuelles. Cela démontre la confiance placée dans le pouvoir judiciaire pour faire preuve de discernement et d'adaptabilité dans l'application des principes légaux.

L'article 4 du Code civil suisse met en évidence le concept de pouvoir d'appréciation du juge, un élément crucial dans l'application du droit. Cette disposition illustre comment le législateur reconnaît et encadre le rôle du juge dans l'interprétation et l'application des lois, en tenant compte de la nature unique de chaque affaire. Selon cet article, le juge n'est pas seulement tenu d'appliquer strictement les règles de droit, mais aussi d'exercer son jugement en fonction de l'équité lorsque la loi le permet ou le nécessite. Cela se produit dans des cas où la loi elle-même accorde expressément au juge le pouvoir de tenir compte des circonstances particulières d'une affaire ou de "justes motifs". Par exemple, dans des affaires familiales ou de garde d'enfants, le juge peut être amené à prendre des décisions qui s'écartent de l'application stricte de la loi pour protéger au mieux l'intérêt de l'enfant, en se basant sur les circonstances spécifiques de l'affaire.

Ce pouvoir d'appréciation est fondamental pour permettre une justice adaptative et personnalisée. Il reconnaît que les situations juridiques ne sont pas toujours noires ou blanches et que l'application rigide de la loi peut parfois aboutir à des résultats inéquitables ou inappropriés. En confiant au juge le pouvoir d'appliquer le droit de manière flexible, le Code civil suisse permet une interprétation et une application des lois qui sont à la fois justes et adaptées aux réalités complexes et diversifiées de la vie en société. Cet article reflète la confiance du système juridique suisse dans le discernement et la compétence de ses juges, leur permettant d'utiliser leur expertise pour atteindre les résultats les plus équitables et appropriés dans chaque cas. En définitive, le pouvoir d'appréciation du juge est un outil essentiel pour garantir que la justice ne soit pas seulement une application mécanique des lois, mais aussi une réflexion approfondie sur l'équité et la justice dans chaque situation particulière.

La lacune praeter legem (outre la loi)

La lacune praeter legem, ou lacune au-delà de la loi, représente une situation où le législateur, souvent involontairement, laisse un vide juridique en ne fournissant aucune disposition légale pour une situation spécifique. Cette forme de lacune se produit lorsque des cas surviennent qui n'ont pas été envisagés ou pris en compte par le législateur au moment de la rédaction de la loi, conduisant à l'absence de règles ou de directives sur la manière de les traiter. Contrairement à la lacune intra legem, où le législateur laisse intentionnellement un certain degré d'interprétation ouverte, la lacune praeter legem est typiquement non anticipée et résulte d'un manque de prévoyance ou de la reconnaissance des développements futurs. Ces lacunes peuvent être particulièrement fréquentes dans des domaines en rapide évolution, tels que la technologie, où de nouvelles situations peuvent surgir plus rapidement que le processus législatif n'est capable de les réglementer.

Par exemple, les questions juridiques liées à l'intelligence artificielle, à la confidentialité des données en ligne ou aux implications de l'édition génomique sont des domaines où des lacunes praeter legem peuvent être présentes. Dans ces cas, il n'existe pas de cadre légal spécifique pour guider l'application ou l'interprétation du droit. Lorsqu'une lacune praeter legem est identifiée, les juges peuvent avoir recours à diverses méthodes pour combler ce vide. Ils peuvent s'appuyer sur des principes généraux du droit, sur des analogies avec des situations similaires réglementées par la loi ou sur des considérations d'équité et de justice. Dans certains cas, la reconnaissance d'une telle lacune peut stimuler le processus législatif, incitant le législateur à élaborer de nouvelles lois ou à modifier les lois existantes pour traiter explicitement la situation en question.

L'article 1 du Code civil suisse offre une illustration claire de la manière dont le système juridique aborde les situations où la loi existante ne couvre pas une situation spécifique. Cette disposition légale souligne la méthodologie et la flexibilité requises pour interpréter et appliquer la loi. Selon le premier paragraphe de cet article, la loi est censée régir toutes les matières qui entrent dans le cadre de ses dispositions, soit explicitement par leur lettre, soit implicitement par leur esprit. Cela signifie que le juge doit d'abord rechercher une solution dans le cadre de la législation existante, en interprétant la loi non seulement selon son texte mais aussi selon l'intention et l'objectif du législateur. Par exemple, dans un cas de litige contractuel, le juge chercherait à appliquer les principes de droit des contrats tels qu'énoncés dans le Code, tout en tenant compte de l'intention générale du législateur concernant les accords contractuels.

Lorsqu'aucune disposition légale spécifique n'est applicable, le deuxième paragraphe du Code civil suisse habilite le juge à se tourner vers le droit coutumier. Dans le cas où même le droit coutumier serait inapplicable, le juge est alors invité à agir comme s'il était législateur, en établissant des règles pour la situation donnée. Cette approche donne au juge une grande latitude pour développer des solutions juridiques en s'appuyant sur les principes fondamentaux de justice et d'équité. Cela pourrait se produire, par exemple, dans des cas impliquant des technologies nouvelles ou émergentes où ni la loi ni la coutume ne fournissent de directives claires. Enfin, le troisième paragraphe guide le juge vers les solutions déjà établies dans la doctrine et la jurisprudence. En l'absence de lois ou de coutumes applicables, le juge doit considérer les analyses et les interprétations juridiques académiques, ainsi que les précédents judiciaires. Cela peut inclure l'examen des commentaires d'experts sur des cas similaires ou l'analyse des décisions judiciaires passées dans des situations comparables. L'article 1 du Code civil suisse montre ainsi l'importance d'une interprétation juridique souple et réfléchie, permettant aux juges de répondre efficacement aux lacunes juridiques et de s'adapter aux circonstances changeantes de la société. Cette disposition assure que le droit reste dynamique et capable de répondre aux besoins en constante évolution des individus et de la société.

Annexes

- Code civil suisse

- Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen de 1789

- Convention européenne des droits de l’Homme

- Déclaration de Virginie : étude de texte