« Théories de l'économie politique internationale » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 163 : | Ligne 163 : | ||

Le libéralisme classique de l'économie mondiale d'avant 1914 était relativement libre des échanges et des flux de capitaux dans le cadre de l'étalon-or. Le stade actuel de la mondialisation, avec la progression du libre-échange et de la libre circulation des capitaux et l'idéologie associée du consensus de Washington, a été théorisé en 1990 par John Williamson. Selon cette théorie, la recette essentielle du développement économique consiste à libéraliser l'économie, à la privatiser et à la déréglementer. | Le libéralisme classique de l'économie mondiale d'avant 1914 était relativement libre des échanges et des flux de capitaux dans le cadre de l'étalon-or. Le stade actuel de la mondialisation, avec la progression du libre-échange et de la libre circulation des capitaux et l'idéologie associée du consensus de Washington, a été théorisé en 1990 par John Williamson. Selon cette théorie, la recette essentielle du développement économique consiste à libéraliser l'économie, à la privatiser et à la déréglementer. | ||

== | == Considération générale == | ||

Il existe un parallèle entre le débat entre le mercantilisme, le nationalisme et le libéralisme en économie politique classique et le débat entre le réalisme et le néolibéralisme en relations internationales et en EPI. | |||

Le mercantilisme, le nationalisme et le libéralisme sont tous deux des écoles de pensée qui fournissent des doctrines et des visions du monde puissantes qui forment encore la politique économique. Par exemple, en France aujourd'hui, lorsqu'il s'agit de discuter de politique industrielle, tout le monde parle de Colbert et s'inspire de la manière dont Colbert a promu l'industrie aux 17e et 18e siècles en France. | |||

Ces écoles de pensée sont moins utiles en tant que cadres analytiques. Elles ont une orientation beaucoup plus normative et positive. Elles cherchent à appréhender le monde à partir d'un certain nombre d'idées préconçues sur l'organisation et le fonctionnement des sociétés. En tant que cadres analytiques, ils ne sont pas très utiles. | |||

L'EPI moderne a tenté de développer une approche plus positive et plus analytique pour comprendre et analyser le fonctionnement de l'économie et du capitalisme mondiaux. Le principal avantage de cette approche est qu'elle permet une analyse qui comprend pourquoi il est possible d'avoir des éléments mercantiles et libéraux coexistant les uns à côté des autres dans le même système. | |||

Cela signifie que l'EPI moderne se base sur l'identification des blocs de construction ou variables politiques et économiques sur lesquels le capitalisme mondial est fondé et fonctionne. Elle tente également d'identifier la manière dont ces variables interagissent les unes avec les autres. Les trois principales catégories de variables utilisées par l'EPI sont : | |||

* | *les intérêts, à savoir les acteurs économiques qui composent le système et le type d'intérêts qu'ils ont. Elle rejette l'idée que ce que l'on appelle l'intérêt national est primordial, etc. Il rejette également l'idée que tous les individus ont les mêmes intérêts fondamentaux qui sont à la base de la notion libérale d'homo economicus était qui est à la base de nouvelles classifications. | ||

*institutions: institutions | *institutions : les institutions ont une influence indépendante sur la façon dont s'organise l'interaction économique entre les États dans le capitalisme mondial. | ||

* | *les idées qui ont une influence indépendante sur la manière dont les politiques économiques étrangères sont élaborées et dont les États interagissent entre eux dans l'économie politique internationale. | ||

= Theoretical evolution = | = Theoretical evolution = | ||

Version du 16 mars 2021 à 19:24

| Faculté | Global Studies Institute |

|---|---|

| Professeur(s) | Christakis Georgiou[1][2][3][4] |

| Cours | Économie politique internationale |

Lectures

- Qu'est-ce que l'économie politique internationale ?

- Une brève histoire du capitalisme international

- Théories de l'économie politique internationale

- Coopération commerciale internationale

- Politique commerciale intérieure

- Politique des accords commerciaux préférentiels

- Les sociétés multinationales et les chaînes de valeur mondiales

- Politique des entreprises multinationales

- Coopération monétaire internationale

- Politique monétaire et de change

- Politique des crises financières internationales

- Les démocraties dans les économies mondialisées

Ce cours porte sur les théories de l'économie politique internationale ou du capitalisme mondial. Nous passerons d'abord en revue les débats historiques sur le capitalisme mondial qui couvriront le mercantilisme et le libéralisme. Ce sont les deux principales visions du monde ou approches générales du capitalisme mondial et de la manière dont les économies individuelles s'y rattachent. Nous le ferons parce que ces deux approches de la mentalité sont toujours pertinentes aujourd'hui, non pas tant en tant que théories au sens analytique du terme, mais en tant qu'approches de la manière dont les politiques sont élaborées. Nous examinerons comment la PEI a émergé théoriquement à partir des débuts de la PEI. Lorsque l'EPI s'est développée en tant que discipline ou sous-discipline universitaire distincte dans les années 1970, elle l'a fait en grande partie à partir des débats sur les relations internationales. À cet égard, nous examinerons comment les débats en RI ont donné naissance à l'EPI. Nous examinerons plus en détail les perspectives de l'EPI américaine contemporaine. La discipline peut être divisée en deux grandes écoles : l'école américaine et l'école britannique. Ce cours se concentre principalement sur l'école américaine. Par conséquent, nous examinerons les perspectives théoriques de l'école américaine au cours des 30 dernières années et les appliquerons tout au long du cours.

Débats historiques sur le capitalisme mondial

Le mercantilisme

Pour Oatley, "le mercantilisme est une école traditionnelle d'économie politique datant (au moins) du XVIIe siècle. Elle affirme que le pouvoir et la richesse sont inextricablement liés. En conséquence, elle soutient que les gouvernements structurent leurs transactions économiques internationales de manière à renforcer leur pouvoir par rapport aux autres États et à la société nationale. Le mercantilisme dépeint donc l'économie politique internationale comme intrinsèquement conflictuelle."[5]

En termes purement économiques, le mercantilisme conçoit la manière dont la lutte entre les États se joue sur la scène économique internationale en examinant la balance commerciale. L'indicateur clé de la capacité d'un État à gagner ou si un État est en train de gagner le conflit économique avec d'autres États est s'il exporte plus qu'il n'importe. Par conséquent, c'est un État qui enregistre des excédents commerciaux au lieu de déficits commerciaux. L'aspect connexe est la capacité d'un État à maîtriser les technologies avancées du moment.

Le développement économique de l'humanité étant basé sur un processus continu de développement des capacités technologiques et techniques, le mercantilisme en est venu à supposer qu'un État était puissant s'il se trouvait à la frontière technologique et s'il possédait des industries basées sur les technologies les plus avancées du moment.

Ce point est important, car les premiers mercantilismes des 16e et 17e siècles visaient davantage à contrôler les marchés d'outre-mer par la force et à s'assurer que la richesse qui pouvait être extraite de ce contrôle profitait principalement à la mère patrie. Il ne s'agissait pas tant de maîtriser le processus de développement technologique.

Les origines du mercantilisme

Les origines du mercantilisme mais aussi du libéralisme remontent à l'Angleterre. Dans une large mesure, on peut associer le mercantilisme à la pratique de la Compagnie des Indes orientales qui fut la principale entreprise mercantiliste du XVIIe siècle en Angleterre. Néanmoins, il existait également des compagnies des Indes orientales aux Pays-Bas, en avant et en alcool.

Le mercantilisme est une doctrine développée d'abord en Angleterre, puis elle se diffuse en Europe. Les Pays-Bas, la France, l'Autriche, la Prusse, les principales puissances de l'époque mais surtout les amis et les Pays-Bas sont les principales puissances qui ont des activités maritimes. Cependant, la France était surtout une puissance terrestre, et les Pays-Bas étaient la puissance maritime typique. La France avait également des activités et des capacités maritimes, et elle a donc également développé une politique mercantiliste. L'Autriche et la Prusse étaient des puissances plus enclavées, elles étaient donc moins impliquées dans ce jeu au 17ème siècle. Cependant, plus tard, la Prusse et l'Allemagne au 19ème siècle ont adopté une politique mercantiliste modifiée ou du moins une philosophie pour organiser leur politique économique.

Thèmes

Pour le mercantilisme, il existe un lien apparent entre le pouvoir de l'État et le commerce extérieur.[6] Le mercantilisme et le libéralisme ont deux visions de la relation entre le pouvoir de l'État et l'accumulation privée. Pour le mercantilisme, les deux vont de pair, ils sont liés.

Les Compagnies des Indes orientales étaient les manifestations typiques de cette politique au 17ème siècle et au 18ème siècle. L'Angleterre, les Pays-Bas et la France en possédaient une. Ces compagnies dominaient l'outre-mer ainsi que le commerce à distance avec l'Inde. Il est important de se rappeler que ces compagnies exercent également un contrôle administratif sur des territoires, contrôle donné par les Etats avec lesquels elles étaient liées aux territoires dans lesquels elles ont développé leurs activités commerciales. Il existe un lien très étroit entre le pouvoir et l'abondance. L'organisation même chargée d'accumuler des richesses à l'étranger est aussi celle qui est chargée de l'administration publique de ces territoires.

Le contexte de l'émergence des Etats-nations centralisés

Le contexte est celui de l'émergence des États-nations centralisés. Le début du XVIIe siècle correspond à l'union entre l'Angleterre et l'Écosse et au développement d'un puissant appareil d'État centralisé au Royaume-Uni. La France est à l'apogée de son pouvoir absolu sous Louis XIV. Les Pays-Bas passent d'un ensemble de provinces vaguement liées à un État international, et ainsi de suite.

L'émergence d'États-nations centralisés s'accompagne d'un processus de concurrence des grandes puissances entre ces États. Parce que ce pouvoir se concentre, il y a une rivalité entre ces centres de pouvoir. Il y a une recherche de nouveaux marchés d'outre-mer et donc, la première vague d'expansion coloniale.

Les visions du monde philosophiques plus larges qui sous-tendent le mercantilisme dans la sphère économique sont la politique réelle machiavélienne et hobbesienne. Ce sont les traditions philosophiques qui informent la tradition du réalisme dans les relations internationales. Le mercantilisme a des liens intellectuels clairs avec l'école réaliste des relations internationales.

Vision du monde des mercantilistes

Dans cette vision du monde, la politique internationale et l'économie internationale sont considérées comme un jeu à somme nulle. Qu'est-ce que cela signifie ? Cela signifie que ce qui compte dans ce jeu, ce sont les gains relatifs et non les gains absolus.

Le calcul d'un État pour un événement ayant une transaction économique avec un autre État n'est pas tant de savoir si cela sera bénéfique pour moi. La question est de savoir si cela sera plus bénéfique pour moi que pour l'autre État. C'est la base sur laquelle les transactions économiques et les relations économiques entre les États sont organisées dans cette vision du monde.

Cela n'a de sens de participer à une transaction que si je vais en tirer plus de bénéfices que mon arrivée. Dans ce cas, on se demande pourquoi il y aurait une transaction économique en premier lieu, car s'il est évident que les gains relatifs sont d'un côté plutôt que de l'autre, il y aura toujours un État qui refusera de s'engager dans des transactions économiques. Il est donc évident que pour les mercantilistes, la politique économique étrangère est davantage l'affaire d'un seul État qui tente d'imposer sa politique à d'autres territoires qu'un processus dans lequel les grands s'engagent mutuellement dans des relations économiques.

Avec cela vient l'idée de l'intérêt national. L'intérêt des appareils d'État centralisés émergents de l'époque prévaut sur les intérêts individuels, d'accord. Il n'existe pas de société civile avec ses propres intérêts et droits distincts qui pourraient être contradictoires et conflictuels et distincts des intérêts de l'État. Il y a l'État, il a son propre intérêt qui est l'intérêt national, et les individus au sein de cet État doivent se comporter d'une manière qui sert l'intérêt national. C'est une vision du monde très libérale, libérale dans le sens où ce n'est pas une vision anti-individualiste.

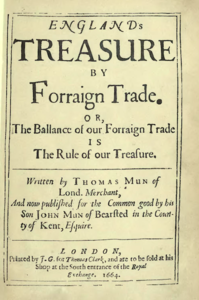

Principales figures du mercantilisme : Thomas Mun et Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Parmi les principales figures du mercantilisme figure Thomas Mun. Il était un marchand privé et, surtout, l'un des directeurs de la Compagnie des Indes orientales. Il était engagé dans sa pratique et était également l'un des théoriciens de la pratique du mercantilisme. Mun était membre du Standing Committee on trade, une commission royale créée au XVIIe siècle pour conseiller le royaume sur sa politique étrangère. Vers 1630, il a publié England's treasure by foreign trade qui est un traité sur la manière dont la pratique du commerce extérieur doit servir à l'accumulation de richesses au service du royaume.

Dans England's Treasure By Foreign Trade publié en 1664, Mun déclare : "Par conséquent, le moyen ordinaire d'augmenter la richesse et le trésor est le commerce extérieur. Dans lequel nous devons toujours observer cette règle : vendre plus aux étrangers par an que nous consommons de leur valeur."[7][8][9]

La règle d'or du mercantiliste est une balance commerciale positive, c'est-à-dire avoir un excédent commercial. Pour Mun, le moyen ordinaire d'accroître la richesse était le commerce extérieur et non le développement technologique.

La pensée mercantiliste primitive n'était pas associée à l'idée qu'un État soit à la frontière technologique et ait des industries basées sur les technologies les plus avancées du moment. Il s'agissait d'une vision du développement économique comme étant exogène à l'économie nationale. La richesse était apportée de l'étranger, et ce n'était pas un processus généré de manière endogène au sein de l'économie nationale.

Une autre grande figure est Jean-Baptiste Colbert, qui fut le ministre des finances de Louis XIV. Aujourd'hui en France, au lieu de parler de mercantilisme, on parle de colbertisme pour désigner des politiques économiques contemporaines qui ont une certaine filiation avec les doctrines de mon pays.

Colbert a promu la fabrication par l'État : la substitution des importations et la promotion des exportations. L'idée qu'il fallait des politiques pour empêcher les importations et encourager les exportations vers les marchés étrangers. Colbert a également développé l'idée que la France devait avoir une balance commerciale favorable. Il est également le fondateur de la Compagnie française des Indes orientales.

Il est intéressant de noter que, dans le cas de Colbert, il y a les prémices de quelque chose de différent dans la mesure où il a théorisé le processus de fabrication dirigé par l'État. L'État devait intervenir pour développer des capacités productives et technologiques au service de la nation et du royaume. Il y a là quelque chose de différent qui se développera plus tard dans les doctrines du nationalisme économique et du développementalisme national.

Doctrines apparentées ultérieures

Ce ne sont pas des doctrines purement mercantiles, mais qui ont une relation claire avec le mercantilisme et une affiliation claire avec le mercantilisme.

Nationalisme économique

Le nationalisme économique est lié à Alexander Hamilton chez Freidrich List. Le contexte du nationalisme économique est le 19ème siècle et la domination de l'Angleterre et donc la Pax Britannica. Il est associé à la pratique et à la théorie du libéralisme. Le nationalisme économique est responsable de l'hégémonie des États-Unis en Amérique, notamment après l'indépendance et après la victoire du Nord dans la guerre civile en 1864. En Allemagne, notamment après la création de l'union douanière allemande jusqu'à la fermeture du marché allemand aux apports étrangers en 1879.

Ces deux processus sont liés à la construction de l'indépendance de l'État. Dans le cas des États-Unis aussi, les colonies sont devenues des États souverains à part entière. La construction de l'État après la guerre de Sécession parce qu'après la guerre de Sécession, il y a un processus de centralisation du pouvoir de l'État au sein de la Fédération américaine. Les États-Unis passent donc d'une collection d'États souverains décentralisés à une fédération plutôt centralisée vers la fin du 19e siècle. Typiquement, au 19e siècle, les gens se référaient aux États-Unis au pluriel. À partir de la fin du 19e siècle, il est plus typique de parler des États-Unis au singulier.

Dans le cas de l'Allemagne, l'union douanière du début des années 1820 était considérée comme la prémisse de l'unification allemande, un processus inspiré par la Révolution française et les doctrines de la nation qui en sont issues et qui se sont diffusées en Allemagne au cours des guerres napoléoniennes. Après le processus d'unification allemande dans les années 1860, qui a culminé en 1870 avec la création de l'Empire allemand. Il y a quelque chose de plus qu'un processus de construction d'un État, il y a un État puissant qui émerge sur le continent européen et qui supplante la France comme principale puissance sur le continent.

Dans les deux cas, et c'est là la rupture avec le mercantilisme des débuts, aux États-Unis comme en Allemagne, le nationalisme économique est considéré comme un moyen de promouvoir une industrialisation et un développement économique pilotés par l'État grâce aux infrastructures publiques, aux investissements et au protectionnisme. En Allemagne et aux États-Unis, le développement des réseaux ferroviaires se fait à la fin du XIXe siècle sur la base du protectionnisme.

Il a été considéré comme un moyen de se réunir avec l'économie nationale pour permettre le développement économique national. Alexander Hamilton a été le premier secrétaire au Trésor américain. A ce titre, il a rédigé en 1791 un rapport sur le sujet des manufactures intitulé Report on the Subject of Manufactures qui a été présenté au Congrès et qui reprend toutes ces idées.[10][11]

Ils ont été mis en œuvre sans réserve tout de suite. Le Nord a dû gagner la guerre civile avant de pouvoir les mettre en œuvre sans réserve. Pourtant, ils ont coexisté avec le Sud et le libéralisme et le Sud et le libre-radicalisme pendant trois quarts de siècle.

Développementalisme national

Une doctrine apparentée au nationalisme économique du 20e siècle est le développementalisme national. Il s'agit de la réponse du 20e siècle à l'hégémonie américaine et aux idéologies qui ont accompagné l'hégémonie américaine après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, à savoir le libéralisme mondial et l'internationalisme libéral.

Il est important de noter qu'une certaine version du développementalisme national a été appliquée même par les alliés des États-Unis, notamment la France, le Japon et la Corée du Sud. Mais le développementalisme national a surtout été appliqué en Amérique latine et en Inde.

La principale pratique associée au développementalisme national est l'industrialisation par substitution d'intrants, c'est-à-dire l'idée que si vous voulez développer votre propre capacité industrielle et technologique, vous devez exclure, au moins pendant une période assez longue, les intrants industriels provenant d'autres pays qui ont déjà maîtrisé les technologies avancées. Sinon, vous ne serez pas en mesure de développer des industries qui maîtrisent ces technologies, et vous serez donc à jamais condamné à consommer les produits avancés des autres pays.

La théorie du développement national est une théorie de la dépendance principalement associée à la figure de l'économiste argentin Raul Prebisch. Prebisch a publié en 1950 The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems, qui a donné naissance à l'hypothèse Prebisch-Singer, selon laquelle le prix des produits primaires diminue par rapport au prix des produits manufacturés sur le long terme, ce qui entraîne une détérioration des termes de l'échange des économies basées sur les produits primaires.[12] Le travail de Prebisch a été rédigé sous la forme d'un rapport aux Nations unies, et pendant longtemps, entre les années 1950 et 1970, les Nations unies ont été poussées par le conflit entre le libéralisme américain et le développementalisme du monde en développement.

Libéralisme

Selon Oatley, le libéralisme est "une école traditionnelle d'économie politique qui a émergé en Grande-Bretagne au cours du 18ème siècle comme un défi au mercantilisme ; le libéralisme affirme que les activités économiques visent à enrichir les individus et que l'Etat devrait donc payer pour jouer peu de rôle dans le système économique. Le libéralisme a donné naissance à la théorie de l'avantage comparatif. Il suggère que les économies politiques internationales sont coopératives plutôt que conflictuelles."

Sur presque tous les points, les définitions du mercantilisme et du libéralisme s'opposent. La richesse et le pouvoir ne sont pas inextricablement liés. Le rôle de l'État n'est pas d'être un promoteur actif du développement économique mais un promoteur passif car il doit garantir les droits de propriété, les infrastructures de base, etc. Il doit se tenir à l'écart du commerce extérieur, de l'investissement industriel sur le territoire national, etc.

En clair, le libéralisme repose sur l'idée que la politique internationale n'est pas un jeu à somme nulle, mais un jeu à somme positive. Ce qui importe lorsque des États s'engagent dans des transactions économiques entre eux, c'est la quantité de gains qu'ils en retireront, indépendamment de la quantité de gains que l'autre État en retirera. C'est l'idée de gains absolus par opposition aux gains relatifs pour les théoriciens du mercantilisme. La coopération devient beaucoup plus plausible car, après tout, ce qui compte, c'est la quantité de bien-être économique supplémentaire que les États gagnent grâce aux interactions économiques internationales et non les gains relatifs qu'ils en retirent.

Origines

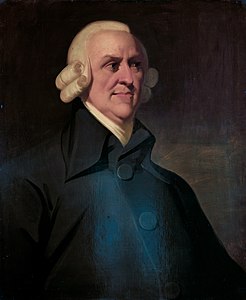

Cette théorie est apparue aux 18ème et 19ème siècles en Angleterre. La première figure marquante du libéralisme est Adam Smith, et l'autre figure majeure est David Ricardo. Ils développent une critique de ce qu'ils appellent le système mercantile à la recherche de rente. Dans le cas d'Adam Smith, il associe cette critique du mercantilisme à une critique du colonialisme en Amérique du Nord. Il est favorable à l'indépendance des colonies américaines.

Thèmes

Le cœur du libéralisme est l'idée d'intérêt et de droits individuels et le lien entre cela et le bien-être collectif. Le bien-être collectif est favorisé non pas parce qu'un État qui incarne le bien-être collectif s'en charge, mais parce que les individus égoïstes poursuivent leurs propres intérêts. Et ils ont le droit de le faire, et en interagissant les uns avec les autres en fonction de leurs propres intérêts, ils augmentent le bien-être collectif, qui est la voie vers l'accumulation de la richesse collective.

Ils ont théorisé l'idée qu'il doit y avoir une liberté des prix, donc une liberté d'importation. Les prix ne sont pas faussés artificiellement par des moyens artificiels pour écarter certains biens du marché au profit d'autres. Ils ont également théorisé la supériorité des marchés et de la concurrence pour organiser l'activité économique et le développement économique.

Chez Adam Smith, le gouvernement n'est pas absent. Il a un rôle essentiel à jouer. L'État est un organisateur des marchés et garantit les libertés économiques individuelles des droits de propriété. L'État est là pour s'assurer que les marchés fonctionnent correctement, il doit donc mettre fin aux comportements de recherche de rente, aux rentiers et aux monopoles, etc. L'État doit garantir les droits de propriété afin que les droits individuels soient protégés et qu'il n'y ait pas de comportement prédateur sur le marché, car sinon, les mécanismes du marché sont faussés. Il existe un lien évident entre ce type de libéralisme et la tradition antitrust qui s'est développée plus tard, à la fin du XIXe siècle, aux États-Unis d'Amérique. De manière controversée, aux États-Unis, la tradition antitrust est un mouvement populiste.

Contexte

Le contexte est celui des révolutions américaine et française avec la fin de l'absolutisme et les débuts de la démocratie de masse et de l'État de droit. Dans le cas de la Révolution française, il y a une contradiction car, en même temps que la Révolution française promeut l'idée de nation, l'idée d'intérêt national, l'idée d'une communauté nationale, elle promeut aussi les idéaux de la démocratie de masse et des libertés individuelles ainsi que l'État de droit.

Vision du monde

Les visions du monde des Lumières sont la liberté et la propriété associées au philosophe anglais Lockes dès le XVIIe siècle puis reprises par les philosophes français et francophones. Avec la révolution de la rationalité et Kant, l'idée s'oppose à la vision hobbesienne du monde basée sur des instincts destructeurs et agressifs logés dans chaque être humain. Pour les libéraux, les êtres humains sont des individus rationnels. Les êtres rationnels savent que leur bien-être individuel est lié au bien-être individuel des autres dans la société et ont donc tendance à coopérer.

Pour eux, la politique internationale est un jeu à somme positive qui est là pour favoriser la coopération interétatique.

Principaux protagonistes : Adam Smith, David Ricardo et Richard Cobden

Adam Smith est avant tout la principale figure du libéralisme. Il était également conseiller des hommes politiques nationaux et son œuvre majeure en matière d'économie politique est Une enquête sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations, publiée en 1776.

"Si un pays étranger peut nous fournir une marchandise à meilleur marché que nous ne pouvons la fabriquer nous-mêmes, mieux vaut la leur acheter avec une partie du produit de notre propre industrie, employée d'une manière où nous avons quelque avantage. L'industrie générale du pays n'en sera pas diminuée pour autant, mais devra seulement trouver comment l'employer avec le plus grand avantage."

Cela préfigure l'idée d'avantage comparatif, même si Adam Smith n'avait pas de théorie de l'avantage comparatif. Pour Adam Smith, le commerce international était fondé sur l'avantage absolu. Il était bon pour un pays de commercer s'il fabriquait quelque chose de mieux qu'un autre pays. Si un État pouvait produire un bien plus efficacement qu'un autre pays. Par conséquent, deux pays pouvaient se spécialiser dans ces biens.

La richesse nationale n'est pas associée à l'excédent commercial pour accumuler de la richesse, car la richesse est produite par le processus d'échange. Par conséquent, il suffit que la balance commerciale soit en équilibre avec les autres pays. C'est par le processus d'échange que la richesse est accumulée.

David Ricardo est l'autre personnalité et théoricien de premier plan. Ricardo était un banquier à Londres, un économiste et un membre du parlement. En 1817, il écrit Principles of political economy and taxation dans lequel il théorise explicitement l'avantage comparatif. Il est également un critique des Corn Laws qui ont été votées au début des années 1810 et qui sont des tarifs douaniers sur les entrées de céréales pour protéger les producteurs nationaux de céréales. Ricardo a également fait campagne pour le libre-échange en faveur de l'abolition des droits de douane.

L'avantage comparatif développé par Ricardo est différent de l'avantage absolu. L'idée clé est que les pays doivent se spécialiser dans ce qu'ils produisent le mieux au sein de leur propre économie, et non dans ce qu'ils produisent le mieux dans le monde entier. Même si un pays est moins efficace dans la production d'un bien qu'un autre pays produit, il devrait quand même le produire s'il est plus efficace et produit ce bien plutôt qu'un autre dans son économie nationale.

La troisième figure est Richard Cobden. Cobden était un fabricant de Manchester et un membre du parlement. Il est le chef de file de l'école libérale de Manchester et de la ligue anti-Corn law, qui réussit en 1846 à abroger les Corn laws et à abolir le tarif sur les importations de céréales. Avec lui a été inauguré le grand cycle du libre-échange.

L'idée est que le libre-échange favorise l'égalité, car dans ce contexte, le libre-échange se traduit par des prix alimentaires moins élevés pour les travailleurs des centres urbains qui se développent rapidement au Royaume-Uni à l'époque. Il a donc réduit les inégalités car les travailleurs ont vu leur pouvoir d'achat augmenter par la simple abolition des droits de douane, même si leur salaire est resté le même. Ils voyaient leur pouvoir d'achat augmenter au détriment des propriétaires terriens, car ces derniers ne pouvaient plus vendre leurs produits aux prix qu'ils vendaient auparavant ; soit ils étaient anéantis comme ils l'étaient, soit ils devaient vendre à un prix inférieur. Il y avait donc un transfert de bien-être de la valeur économique des propriétaires terriens vers les travailleurs. C'était donc l'idée sur laquelle les pactes de libre-échange promouvaient l'égalité dans le contexte du 19ème siècle en Angleterre.

Doctrine et manifestations connexes ultérieures

Le libéralisme classique de l'économie mondiale d'avant 1914 était relativement libre des échanges et des flux de capitaux dans le cadre de l'étalon-or. Le stade actuel de la mondialisation, avec la progression du libre-échange et de la libre circulation des capitaux et l'idéologie associée du consensus de Washington, a été théorisé en 1990 par John Williamson. Selon cette théorie, la recette essentielle du développement économique consiste à libéraliser l'économie, à la privatiser et à la déréglementer.

Considération générale

Il existe un parallèle entre le débat entre le mercantilisme, le nationalisme et le libéralisme en économie politique classique et le débat entre le réalisme et le néolibéralisme en relations internationales et en EPI.

Le mercantilisme, le nationalisme et le libéralisme sont tous deux des écoles de pensée qui fournissent des doctrines et des visions du monde puissantes qui forment encore la politique économique. Par exemple, en France aujourd'hui, lorsqu'il s'agit de discuter de politique industrielle, tout le monde parle de Colbert et s'inspire de la manière dont Colbert a promu l'industrie aux 17e et 18e siècles en France.

Ces écoles de pensée sont moins utiles en tant que cadres analytiques. Elles ont une orientation beaucoup plus normative et positive. Elles cherchent à appréhender le monde à partir d'un certain nombre d'idées préconçues sur l'organisation et le fonctionnement des sociétés. En tant que cadres analytiques, ils ne sont pas très utiles.

L'EPI moderne a tenté de développer une approche plus positive et plus analytique pour comprendre et analyser le fonctionnement de l'économie et du capitalisme mondiaux. Le principal avantage de cette approche est qu'elle permet une analyse qui comprend pourquoi il est possible d'avoir des éléments mercantiles et libéraux coexistant les uns à côté des autres dans le même système.

Cela signifie que l'EPI moderne se base sur l'identification des blocs de construction ou variables politiques et économiques sur lesquels le capitalisme mondial est fondé et fonctionne. Elle tente également d'identifier la manière dont ces variables interagissent les unes avec les autres. Les trois principales catégories de variables utilisées par l'EPI sont :

- les intérêts, à savoir les acteurs économiques qui composent le système et le type d'intérêts qu'ils ont. Elle rejette l'idée que ce que l'on appelle l'intérêt national est primordial, etc. Il rejette également l'idée que tous les individus ont les mêmes intérêts fondamentaux qui sont à la base de la notion libérale d'homo economicus était qui est à la base de nouvelles classifications.

- institutions : les institutions ont une influence indépendante sur la façon dont s'organise l'interaction économique entre les États dans le capitalisme mondial.

- les idées qui ont une influence indépendante sur la manière dont les politiques économiques étrangères sont élaborées et dont les États interagissent entre eux dans l'économie politique internationale.

Theoretical evolution

The first theory, mercantilism dates back to 1620s, liberalism to the 1770s, economic nationalism attributed to Alexander Hamilton to the end of the 1790s and beginning early 1800s. With Marxism and neoclassical economics, it leads up to the 1870s. In a way, Marxism sees itself as the continuation of classical political economy, whereas in neoclassical economics sees itself as a bifurcation inspired by the positive sciences.

Then there is a new version of all those theories coming up. From the early 1900s, IR liberalism and idealism spring up. The high point of IR liberalism and idealism is in the 1920s and the League of Nations. Since the 1930s realism and new realism began to develop and developed as a critique of idealism and a critique of the League of Nations' failure. The major work The Twenty Years' Crisis: 1919–1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations written by E. H. Carr. The critic is that with the League of Nations, the war did not stop between the main powers between 1919 and 1939. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace written by Hans Morgenthau published in 1948 is another major work which introduces the concept of political realism, presenting a realist view of power politics.

Since the 1970s and this is closely associated with IPE development, neoliberal institutionalism has developed. Neoliberal institutionalism to a large extent informs how IPE tries to analyse global capitalism and the functioning of the international community.

It is important to be able to locate in time when such a theory emerges and become dominant and declines.

Neorealism

From early IR to IPE, how did we move from a situation in which realism was the main way international relations were studied to the detailed IPE development in the 1970s and the 1990s?

Neorealism was the dominant IR paradigm of the 1930s and the 1970s. It is important to put that in perspective with real-world developments. Because that intellectual hegemony coincides with the interwar breakdown of global capitalism and the rise of economic nationalism, national developmentalism and the primacy given to domestic policy autonomy over external stability that characterised the period between the early 1930s and the early 1970s. Both one part of the interwar collapse and embedded liberalism. Although it was a compromise between domestic policy autonomy and external stability, it gave primacy to domestic policy.

What were the main theoretical aspects of realism and neorealism?

The basic premise is that being some national system is anarchic. What does that mean? It means that there is no world government, there is no world rule of law, and therefore there is no mechanism to impose cooperation among sovereign states. Interaction between sovereign states is not based on the rule of law. It is not based on norms on rules and whatever it is based on raw power. The way states interact with each other is extremely different from how individuals interact or groups of individuals interact within a given state. The basic concept here is external sovereignty.

Therefore the basic variable that determines how the international system and by extension of the international particular economy works is the distribution of power among states.

If the basic way in which state interacts, how they relate to each other in power returns, and how power is distributed among them is the main determinant of how they interact. There is also the theory about what is the distribution of power that is most likely to lead to stability: unipolar, bipolar, multipolar, etc. Realists don’t agree with each other, but the basic terms of the debate are the same.

Along with this external sovereignty is also the idea that states are unitary actors with national interest. That national interest determines their behaviour. This is an extension of the idea of sovereignty. There is one sovereign state, and the realists take that to mean that the state is a single actor with a single way of perceiving things of understanding things and defining its own interest. For most realists, the national interest is first and foremost the preservation of state sovereignty. Then hinges on the accumulation of power and so the national interest is about accumulating power within the international system. Here and this is not the case with neoliberalism, states are not driven by contradictions and different bureaucracies within the state apparatus. All work towards the same goal. There is no contradiction between state managers, they don’t pursue different goals, and civil society interests do not permeate the states. They are not amenable to be influenced by the interest group.

Relative gains and international relations are a zero-sum game. International relations are basically conflictual. Neorealism is in line with the basic tenets of mercantilism and economic nationalist stock. If economic power is the main variable, then it is important to master the day’s advanced technologies. What matters is having a share as big as possible of global production and global trade as a state can. Those are indicators of power for realists as they are former mercantilists and economic nationals. There is also a focus for realists on high versus low politics. High politics is anything it has to do with war, security and diplomacy, whereas low politics is politics has to do with economic aspects of international life.

Neoliberalism and its critics in the 1970s

The main dimensions of neoliberalism were criticised heavily in the 1960s and the 1970s. Notably, IR is basically conflictual in line with mercantilism and economic nationalism and focuses on high versus low politics.

The main breach in academia’s intellectual hegemony began in the 1950s and the 1960s with many cooperation cases and not rivalry in international relations. The main one was the détente which is the process of thawing of relations between the USSR and the USA and by extension between the USSR block and the American-dominated block. That included the SALT agreements inter alia. There were also many other instances of integration among states through trade cooperation within the GATT and the Comecon in the Soviet bloc. There is also the European integration which is very important because just a few years after Germany has occupied France, there was an agreement between those two states to begin to build a European federation. As the process of European integration developed after the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and throughout the 1960s successfully, there was this idea that international politics does not have to be conflictual and cases of deep cooperation amongst states can take place. This challenge the idea that international relations are basically conflictual.

The idea that neorealism is in line with the basic tenets of mercantilism and economic nationalism thoughts were challenged by the gradual opening of national economy throughout the 1960s and the 1970s. That provided the basis for the takeover of the fourth stage in the history of global capitalism, namely the second globalisation from the 1970s onwards.

It is the case that despite the fact that and better liberalism was to a large extent dominated by economic nationalism closure and so on, it also so very rapid rates of growth in international trade international investment and from the late 1960s onwards international capital flows.

These developments challenged the notion that the future of global capitalism’s future would be inextricably linked to the practice of economic nationalism that prevailed in the 1930s. That challenges the idea of the alignment between neorealism and economic nationalism.

High politics’ primacy over low politics came on the challenge because low politics became much more salient throughout the 1960s. First, because of the end of the Bretton Woods system. In the 1970s the group of 77 developing nations within the United Nations in the 1970s demanded the setup of a new international economic order which is the idea that international economic relations should be organised differently from the blueprint that was set down by the United States in the late 1940s. Finally, after the Bretton Woods system’s collapse, the high salience of European monetary cooperation and integration issues came to play a significant role.

The combination of these factors from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s showed that low politics issues could be very important in the way states interact with each other in the international system.

These three challenges created the first breach in the academic hegemony of realism within international relations. But neorealism was not dethroned overnight. The development of IPE in the 1970s was very much influenced by the debates over the pattern of neoliberalism. The first major questions and major theoretical perspectives that were thrown out by the development of IPE had clear links to the main questions asked by neorealists in their attempt to understand the international system.

The first one was the challenge to the idea that international relations were conflictual. One of the main debates was whether states cooperate. Still, in other cases, they do compete what determines when it is that states compete and when it is that states cooperate.

In the 1970s IPE focused on the interstate level. To typical IR questions such as how does the distribution of power affect international relations, there are the associated IPE questions that dominated the seventies in the eighties. To the question of how the distribution of power affects international relations, the associated question became what determines international economic stability or crises and what determines economic openness or closure. To the question is cooperation possible under anarchy, the modified IPE questions were just to external imbalances to ensure stability, who makes sure that there is a cooperative outcome that ensures there is stability in the system and who sets for an economic policy.

As neorealism hegemony was challenged, the challenge brought and in the 1980s other aspects of the neorealist paradigm came under attack. Another dimension was introduced to IPE in the 1980s. It is a fundamental dimension because this is the main focus of American IPE with foreign economic policy's domestic sources. That was based on the challenge to the idea of States as unitary actors and behave according to the national interest. That is not self-contradictory.

To typical IR questions such as what is the national interest, the modified IPE question would be who sets for an economic policy. The assumption being that different groups of actors may have different interests. So there may be a conflict over who sets for an economic policy whereas for their realists, and that is not even a question, state managers who are imbued with state rationality and whom all push in the same direction set for an economic policy. A second typical IR question is openness and closure in line with the national interest that became who benefits from openness and closure. Openness and closure do not necessarily align with the national interests with which all domestic groups align, but can be to the benefit some groups into the detriment of others. Therefore, there is a conflict over whether a state should open its economy up or barricade itself behind protective barriers.

This is how theoretically IPE emerged based on a challenge to the hegemony of realism and neorealism within international relations discipline.

Power and hegemonic stability

The theoretical perspectives

We are now going to look at these different theoretical perspectives within American IPE. We will look first at the theoretical perspectives that have to do with the systemic level, which is the level of interaction between states. The second part will be about the domestic sources of foreign economic policy. Finally, we will present an overview of the main theoretical perspectives in American IPE such as it has developed since the 1970s.

The link between power and hegemonic stability

The first debate that clearly had to do with the systemic level was the foundational debate on the international political economy. It was the debate about the link between power and hegemonic stability and what became known as a hegemonic stability theory with both its liberal and realist variants.

This debate was launched by the publication of Charles Kindleburger’s book World in Depression, 1929-1939 published in 1973. Kindleberger a liberal reading of economic stability theory. Kindleberger was very much a new dealer who was involved with the administration of the Marshall Plan in Europe in the late 1940s. He was imbued with the liberal internationalist spirit that informed American foreign policy from the 1940s onward.

Kindleberger studied why the Great Depression happened in the 1930s, and he attributed it to what IPE scholars refer to as a hegemonic transition. This is the idea that Pax Britannica was on the decline and had almost disappeared in the 1930s, but Pax Americana was not yet there. In the vacuum between the two conditions were created for the break-up of the fragmentation of global capitalism and that contributed to the Great Depression. For Kindleberger, it was a way of indicating what he did when he was in the Treasury Department in the 1940s because the policy he pursued as a US state official was liberal internationalism. He was in marked contrast to the isolationist policies of the 1930s.

Stephen Krasner published in 1976 State Power and the Structure of International Trade which is an article about the determinants of free trade openness.[13] Krasner attempts to find a correlation between the rise and decline of precision American hegemony and the trend towards open and closure in the world economy. Krasner being realist, he associates openness with the rise and stability over hegemonic power.

In both versions of the theory, the basic idea is that international economic stability and openness and an open international economy both require action by one hegemonic power: Pax Britannica before the First World War Pax Americana since the Second World War.

Theoretically, the assumption that there had to be one hegemonic power came under attack in the 1980s. Some people said that theoretically, it is possible to have a bipolar world that is still stable because both of these powers provide the public goods that underpin the global system’s stability. That’s very much a theoretical debate that doesn’t have a historical application. Therefore, it is not that important in the development of a demonic stability theory.

Very quickly the debate about the conditions of stability mutated into a debate about the conditions of stability of the contemporary international political economy because along with the dollar crisis of the 1970s a debate about the decline over American hegemony has emerged. In the 1970s 1980s, most scholars were convinced that American hegemony was on the decline. Some predicted the collapse of the dollar standard and so on, in particular realists. A major book by historian Paul Kennedy published in 1988 titled The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. Kennedy attempts to show how America was on the verge of a breakdown of hegemonic positions within the international system just as Britain, the Netherlands, France and so on before it had gone through the same process. It should be noted that this book was published two years before the collapse of the Soviet bloc. It is a major thesis rejected now. There is a debate about the state of American power today within IR, but the consensual position is an American hegemony is still very much alive.

The key thing about the development of American IPE is the debate on the decline of the US hegemony throughout the debate about the conditions that couldn’t ensure continued stability despite the fact that there was no longer one hegemonic power willing to provide that stability and to bear the cost of providing that stability.

That debate is best captured by the book by Robert Keohane titled After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. That is a key statement of neoliberal institutionalism. The basic argument is that the sets of relations and institutions established by hegemon to ensure stability will live on after the decline of that hegemon’s power because for the other states in the system the maintenance costs of that regime are lower than the costs that a breakup of that regime would entail. This is a kind of inertia that characterises the institutions set up by the hegemon. That will ensure that stability will prevail even though the hegemon is still not around to enforce those relations and those institutions.

International Institutions

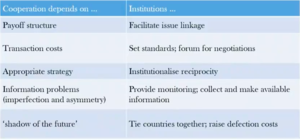

This table is a summary of how neoliberal institutionalism theoretically developed.

Neo-liberal institutionalism is about international institutions and how international institutions can be designed to advance cooperation between states. There are five ways in which institutions can be designed to ensure that those aspects of cooperative behaviour are guaranteed.

The first one is the payoff structure. The payoff structure basically is a fancy way of saying the list of preferences in descending order that states have about how international economic relations should be organised. The payoff structure has to match. This is very much based on game theory. A lot of neoliberal institutions are based on game theory.

The idea is that preferences among states have to match. If they don’t spontaneously match, there has to be a process through which they can be broad closer together with a way through which states can agree to forgo their first preferences in favour of other preferences but can enable the international system to work based on cooperation. Institutions do that by facilitating issue linkage. Linkage is a major feature of the theory of interstate bargaining. Institutions are meant to make sure that when states sit down at the bargaining table, they sit down to talk about both good exchanges and financial services, and so on. So states can make concessions to each other across a spectrum of items that make up the bargaining agenda.

The next issue on which cooperation depends is transaction costs. Transaction cost is a concept that comes from economics. It is the idea that for market transactions to be beneficial, there are costs associated with realising a market transaction, and the costs have to be lowered for the transaction to be worth it. A key transaction cost obviously is distance. There are other types of transaction costs that have to do with the information. International institutions are there to set standards and ensure that parties in international economic transactions can have confidence that the goods and services they exchange leave up to a minimum set of standards.

Institutions also provide a forum for negotiations. They make it easier for states to come to the bargaining table. In contrast, without international institutions and fora for negotiations, it might prove difficult for states to find their way to the bargaining table.

Appropriate strategies are the fact that states need to know that if they make a concession they will get a concession back and anticipate the reaction by another state to a decision that they will take. That is the issue of reciprocity. If we look at the feature the principles of the WTO, reciprocity is one of them. If you give something to a state, you expect the same thing back which facilitates the exchange of concessions.

Information problems, from economics, is mostly information imperfection. It is when parties to a transaction are not fully aware of the transaction’s different aspects. What institutions do is to monitor and gather information to make it available to all parties involved. They can bring down information asymmetries and information imperfections. So they are producers and distributors of information regarding international economic transactions.

Finally, what scholars in IR refer to as the shadow of the future is the idea that a state will interact with another party differently if it knows that down the road the sate will have to repeat the interaction and it will have to transact with that party again. Institutions do that by raising defection costs and tie countries together. Defection costs are the reputation costs that are associated with the WTO, for example, making known to the world that the American or Chinese government has broken the rules.

Unpacking the ‘National Interest’

We will open up the black box of the state and the national interest and understand and identify foreign domestic sources of foreign economic policy.

One aspect of that is identifying the actors that collectively act to influence the definition of foreign economic policy. One way of looking at that is by classes or production factors in some cases, capital labour and landowners. Another is by broad sectors of economic activity. That can be export-oriented sectors of the economy, input competing sectors of the economic sectors that compete with inputs from abroad, non-tradable sectors that do not engage in international trade, the financial sector, the capital intensive industrial sector and so on.

Sectors are a finer grain characterisation of the way economic actors grouped together than classes. Classes are the more macro level, sectors are the more massive level. There are also firms, which is the very individual level, the micro-level. There are distinctions between large transnational corporations, small-medium enterprises (SMEs). Cooperation is also operated through supply chains and others are. Within the same branch of activity, there may have conflicting interests.

Another aspect of this is how our preferences are aggregated. It is not because actress exists that they have the same capacity to come to an agreement about what their collective interest is and also to pursue that interest with state managers. That refers to collective action theory and the concept of organisational capacity. The idea is that the larger the group’s size, the more difficult it is to find a consensual position and pursue collective activity, advance that collective interest and the asymmetry between different groups, and so on.

Small groups of very large actors have greater organisation capacity than big groups of very small actors. Typically the distinction is between monopolistic corporations, on the one hand, and consumers that are each individual in the economy. Therefore they have very little collective organisational capacity.

Another aspect that determines how preferences are aggregated is domestic institutions. The basic distinctions are the distinction between democratic and authoritarian regimes but also within democratic regimes the distinction between majoritarian versus proportional electoral institutions, but also within democratic regimes the way in which bargaining institutions allow for coordination or competition in which setting systems.

Explaining US foreign economic policy

We will take a look at explaining the US foreign economic policy in the twenties, thirties and the seventies.

The first article illustrating this example is Sectoral Conflict and Foreign Economic Policy, 1914-1940 written by Frieden on the US interwar policy.[14] Frieden explained the conflict between isolationism and liberal internationalism in US foreign policy in general. Frieden says this is not about schools of thought within the American state apparatus or within the American party system. This was first and for most about a split within the US’s business community. In particular between the internationalised interests within the American capitalist class and the domestically oriented interests within the American capitalist class. He shows that throughout the twenties and the thirties there was a conflict between those two. Gradually the internationalised segment of the American capitalist class won the day because it gradually became more important in terms of the overall domestic economy. There was a crisis that crystallised the conflict between the two. Therefore throughout the second part of the thirties, the liberal internationalists gradually managed to take over the United States’ foreign policy.

Helen Milner published in 1988 Resisting protectionism: Global industries and the politics of international trade which is a study on protectionism versus free trade both in the interwar period and in the 1970s.[15] She shows that the conflict between protectionism and free trade had to do with the extent to which American cooperations in different sectors of the economy had become internationalised or not. Milner shows that first between the twenties and the seventies, the American economy's overall exposure to the international economy had gone up and explains why in the seventies protectionism did not prevail as opposed to the twenties overall. Then she shows that even within periods, the same distinction applies. Even in the twenties in that minority of sectors in which cooperation have already become transnational internationalised, free trade prevailed over protectionism. It is a very similar argument that Frieden puts forward that applied to trade policy, whereas Frieden has a broader scope.

Other aspects of domestic politics

Another aspect of domestic politics that obviously has been studied and affects how global capitalism functions is institutions. Scholars distinguish between authoritarian and democratic regimes and then within regimes between majoritarian and proportional systems. The basic idea is those authoritarian and majoritarian systems (majoritarian systems are for example the House of Representatives in the United States, the House of Commons in the United Kingdom, the National Assembly in France as opposed to proportional systems like the German federal parliament).

The main assumption and idea is that authoritarian majoritarian regime are more amenable to be captured by special interests and therefore they are more likely to pursue protectionism. Whereas proportional single constituency electoral systems like the American presidency for example, are most sensitive to pressure by non-concentrated groups like consumers, they are more likely to pursue openness because openness is the policy that benefits consumers the most it lowers prices.

Another aspect is so-called to level games. The idea that there is an interaction in the way the interstate system functions and the way the domestic system functions. Executives’ governments that find themselves between those two levels, the domestic and the interstate level, can both benefit. They can argue to their domestic constituents that the interest system constrains them in a way that means that they have to the policies that are not necessarily popular with domestic electors. Still, they can do the same at the interstate level where they can argue in bargaining processes that they are willing to make concessions. Still, they won’t have a majority to ratify those concessions domestically because they are not popular. Therefore they can use that as a bargaining chip in interstate negotiations.

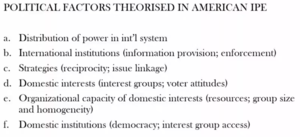

Political factors theorised in American IPE

That is a list of the main factors that have been theorised and continue to a large extent to be theorised in American IPE. We can see that there is a blend of ideas coming from realism and from and from neoliberalism, particularly neoliberal institutions. Clearly, the idea that the distribution of power within the international system affects the way the international political economy works is still very much around. Scholars still debate to a lesser extent than what they did in the 1970s, but they still debate that aspect of the problem.

B is the way international institutions affect the way the international political economy works. The basic question is how can international institutions be made to promote cooperation and therefore openness.

C is the way strategic behaviour between states can lead to cooperation or conflict.

D is how domestic interests influence the way foreign economic policies made and how states interact with each other.

E is a sub-theme of d, which is the organisational capacity of domestic interests and how it affects the way domestic interests can influence an economic policy and have domestic institutions.

Annexes

Références

- ↑ Profil de Christakis Georgiou sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Profil de Christakis Georgiou sur le site de Mediapart

- ↑ Publications de Christakis Georgiou sur Cairn.info

- ↑ Publications de Christakis Georgiou sur Academia.edu

- ↑ Oatley, T. (2018). International Political Economy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351034661

- ↑ Viner, J. (1948). Power versus Plenty as Objectives of Foreign Policy in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. World Politics, 1(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009156

- ↑ Thomas mun: England’s treasure by foreign trade (1664) from Thelatinlibrary.com website: http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/readings/mun.html

- ↑ Perrotta, C. (2014). Thomas Mun’sEngland’s Treasure by Foreign Trade: the 17th-Century Manifesto for Economic Development. History of Economics Review, 59(1), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/18386318.2014.11681258

- ↑ Muchmore, L. (1970). A Note on Thomas Mun’s “England’s Treasure by Foreign Trade.” The Economic History Review, 23(3), 498. https://doi.org/10.2307/2594618

- ↑ IRWIN, D. A. (2004). The Aftermath of Hamilton’s “Report on Manufactures.” The Journal of Economic History, 64(3), 800–821. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022050704002979

- ↑ Nelson, J. R., join(' ’. (1979). Alexander Hamilton and American Manufacturing: A Reexamination. The Journal of American History, 65(4), 971. https://doi.org/10.2307/1894556

- ↑ Prebisch, R. (1950). The economic development of Latin America and its principal problems. Economic Commission for Latin America. Retrieved from https://repositorio.cepal.org//handle/11362/29973

- ↑ Krasner, S. D. (1976). State Power and the Structure of International Trade. World Politics, 28(3), 317–347. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009974

- ↑ Frieden, Jeff. “Sectoral Conflict and Foreign Economic Policy, 1914-1940.” International Organization, vol. 42, no. 1, 1988, pp. 59–90. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2706770.

- ↑ Milner, Helen V. Resisting protectionism: global industries and the politics of international trade. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1988. Print.