« Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

|||

| (25 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 1 : | Ligne 1 : | ||

Agenda setting and | {{Translations | ||

| fr = Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise à l'agenda et formulation | |||

| es = Análisis de las Políticas Públicas: establecimiento y formulación de la agenda | |||

| de = Analyse der öffentlichen Politik: Agendasetzung und Formulierung | |||

| it = Analisi delle politiche pubbliche: definizione e formulazione dell'agenda | |||

| lt = Viešosios politikos analizė: darbotvarkės sudarymas ir formulavimas | |||

}} | |||

{{hidden | |||

|[[Introduction to Political Science]] | |||

|[[Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory]] ● [[The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic]] ● [[Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory]] ● [[The notion of "concept" in social sciences]] ● [[History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts]] ● [[Marxism and Structuralism]] ● [[Functionalism and Systemism]] ● [[Interactionism and Constructivism]] ● [[The theories of political anthropology]] ● [[The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas]] ● [[Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science]] ● [[An analytical approach to institutions in political science]] ● [[The study of ideas and ideologies in political science]] ● [[Theories of war in political science]] ● [[The War: Concepts and Evolutions]] ● [[The reason of State]] ● [[State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance]] ● [[Theories of violence in political science]] ● [[Welfare State and Biopower]] ● [[Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes]] ● [[Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences]] ● [[The system of government in democracies]] ● [[Morphology of contestations]] ● [[Action in Political Theory]] ● [[Introduction to Swiss politics]] ● [[Introduction to political behaviour]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation]] ● [[Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations]] ● [[Introduction to Political Theory]] | |||

|headerstyle=background:#ffffff | |||

|style=text-align:center; | |||

}} | |||

The development of public policy follows a process structured around four essential stages. A public policy comprises a series of actions and decisions taken by government authorities with the aim of responding to a specific problem. The first stage is to identify the problem and put it on the political agenda. This phase, known as setting the agenda, defines the problem that requires government intervention, and justifies why this intervention is necessary. The second stage of the process consists of formulating public policy. This formulation phase provides an answer to the question: what is the solution envisaged to respond to this problem? The aim here is to identify a solution that is both legitimate and acceptable in the current political context. Each of these stages plays a crucial role in the development of an effective policy, guiding the process from the initial identification of the problem to the establishment of a concrete action plan to resolve it. | |||

Agenda-setting analysis seeks to understand how and why certain problems are constructed and recognised as worthy of public attention and state intervention. It is in this phase that the process of 'social construction' of public problems takes place. This means that public problems are not simply objective facts that exist in themselves, but are shaped and defined by social and political actors who interpret and attribute importance to certain situations or conditions. This construction is a complex process, often involving debates and struggles between different actors with different interests and perspectives. Factors such as political power, cultural values, public opinion and the media can all play a role in defining what is considered a public problem. | |||

However, it is important to note that it is often difficult to initiate new public policy. Simply defining a problem as a public issue does not automatically guarantee that it will be put on the political agenda. Obstacles such as lack of resources, political resistance or lack of public interest can prevent a problem from gaining a place on the agenda. As a result, analysing agenda-setting also requires an understanding of the political processes and dynamics that influence which issues are recognised and prioritised, and which are ignored or marginalised. | |||

= The Construction of Public Problems and their Placing on the Political Agenda = | |||

== Definition and Recognition of a Public Problem == | |||

=== The Political Agenda Concept === | |||

The political agenda represents the issues that the political and administrative authorities consider to be priorities and on which they intend to take action. These issues may include various social, economic or environmental problems that require a political response. On the other hand, the media agenda is made up of the stories and issues that are presented as important by the media, whether in newspapers, television news bulletins, radio or on news websites. These topics are those that the media believe deserve the public's attention and may or may not overlap with the political agenda. | |||

These two agendas can interact and influence each other. For example, the media may highlight a particular issue, prompting politicians to pay attention to it and place it on their agenda. Conversely, political decisions can shape the media agenda, especially when they concern issues of public interest. However, there may also be divergences between these two agendas, depending on the priorities, values and constraints of each area. | |||

The political agenda, particularly that of Parliament, is reflected in the subjects and issues addressed by parliamentarians. These can cover a wide range of social, economic, environmental and security issues. Motions, parliamentary initiatives, postulates, questions and interpellations are all tools available to parliamentarians to highlight certain issues. They reflect the concerns of elected representatives and, by extension, their electors. Analysis of this parliamentary agenda can reveal what the priorities of the political authorities are at any given time, what issues are deemed important enough to require political intervention, and how these priorities may change over time. It should be stressed, however, that the political agenda is not limited to what is discussed in Parliament. Other actors, such as government, political parties, pressure groups or individual citizens, can also influence this agenda, through their own actions and initiatives. | |||

In the Swiss system, the government's agenda, i.e. that of the Federal Council, remains less transparent because of the secrecy of deliberations. This is a rule that ensures that discussions within the Federal Council remain confidential. The purpose of this rule is to preserve the collegiality of the government, by allowing its members to debate freely and take decisions in a collegial manner. Nevertheless, even if the details of the Federal Council's discussions are not accessible to the public, the government communicates its decisions through press releases. These press releases can give an indication of the government's priorities, although they only reflect the final decisions and not the debates that led to those decisions. The Federal Council's agenda may be influenced by other factors, such as parliamentary initiatives, popular votes, requests from the cantons or international developments. Analysis of these factors can therefore also give an indication of the government's political agenda, even if the internal decision-making process remains confidential. | |||

The term "agenda" in this context refers to the set of topics that are deemed important and worthy of attention by a specific group. These topics are usually public issues or problems that require action or intervention. When we talk about the media agenda, we are referring to the issues that the media decide to cover and highlight. This agenda can be influenced by various factors, such as current events, public interest, journalistic values, and sometimes even the commercial interests of media companies. Similarly, the agenda of political parties is determined by the issues they choose to focus on, often as part of their election campaigns. This agenda may reflect the values and priorities of the party, the concerns of their voters, as well as electoral strategies. In each case, the agenda is a way for actors to define what is important and to focus attention on these issues. It therefore plays a crucial role in shaping public debate and guiding public policy. | |||

=== The Agenda Setting Process === | |||

The number of issues and questions that can be addressed at any one time, whether in the media, in Parliament, or within government, is necessarily limited. This limitation is due to constraints of time, resources and attention span. Faced with these constraints, the players have to make choices about which issues to highlight and which to ignore. These choices can be influenced by a variety of factors, such as the perceived urgency of an issue, its importance to public opinion, its relevance to existing policy priorities, or its ability to generate support or interest. This means that launching a new public policy can be a difficult and competitive process. Drawing attention to an issue and putting it on the agenda may require effective communication strategies, mobilising support, or convincing key players of the importance of the issue. | |||

The media, like political parties, have a limited attention span and are forced to select the subjects they cover carefully. In the case of a newspaper, space is limited. Editors have to decide which stories deserve to be on the front page, which is the most visible and influential place. These decisions are made on the basis of the newspaper's editorial line, current events, presumed public interest and other factors. Similarly, when political parties launch an election campaign, they have to define their priorities and choose which issues to focus on. These choices are generally made on the basis of the party's values and objectives, the concerns of their electorate, and electoral strategy. This underlines the selective nature of agenda-setting, which is the process by which certain issues are chosen as important and others are ignored. This process can have a significant impact on public opinion, politics and society in general, as it shapes what people talk about and pay attention to. | |||

As part of an election campaign or even their regular communication, political parties tend to focus on a limited number of key themes. This concentration allows parties to create a clear and recognisable brand image, mobilise their electoral base and distinguish themselves from other parties. The themes chosen generally reflect the party's core values, the concerns of their voters and the issues on which they believe they can make a difference. They may also be influenced by current events and the general political climate. Government works in a similar way. Although it has a wider remit, it also has to define its priorities and focus on certain key policy areas. These priorities are usually set out in the government's programme and are guided by electoral commitments, the demands of society and practical constraints. | |||

The agenda of political decision-makers, such as the Federal Council in Switzerland, is limited due to time and resource constraints. These decision-makers are often called upon to take decisions on complex and varied issues, but they can only address a limited number of problems at their regular meetings. This means that they have to prioritise some issues and leave others aside, at least temporarily. This creates competition between the different topics. If one subject is added to the agenda, another may be left aside. This is a dynamic and often complex process, which can be influenced by many factors, such as the urgency of the issues, their relevance to public opinion, existing political priorities and external pressures. The same applies to the agendas of the media and parliamentary committees. All these agendas are limited and cannot be expanded indefinitely to accommodate an unlimited number of subjects. This makes access to the agenda difficult and often competitive, as different players seek to promote their own priorities and issues. This underlines the importance of getting on the agenda in the political process. Getting a place on the agenda is often a crucial step in obtaining political action on a given issue. This often requires advocacy, communication and mobilisation efforts to draw attention to an issue and convince decision-makers of its relevance. | |||

Putting an issue on the agenda is a strategic process that usually involves working to make the issue sufficiently interesting, relevant or urgent to attract the attention of key players, including policy-makers, the media and the public. This process can involve several stages. For example, it may start by identifying and defining the problem in a way that makes it understandable and relevant to a wider audience. This may involve gathering evidence, framing the issue in a certain way, and developing clear and convincing messages. Next, stakeholders can work to draw attention to the problem. This can be done through various communication and advocacy strategies, such as lobbying political decision-makers, mobilising the public, raising awareness in the media, taking part in public debates, and so on. Finally, once the issue has been placed on the agenda, stakeholders generally need to work to maintain attention on it and influence the way it is addressed and resolved. This may involve participating in policy development, lobbying for specific solutions, monitoring implementation and lobbying for changes where necessary. | |||

=== The Systematic Coding of Political Agendas === | |||

The agenda represents the set of public issues that are perceived as priorities by politicians, the media and, by extension, the public. The front page of a newspaper is often an accurate representation of what is considered important or urgent at any given time. Decisions about what appears on the front page are generally based on a variety of factors, including current events, public interest, and the newspaper's editorial line. The systematic codification of these agendas - media, political, governmental, parliamentary, or budgetary - makes it possible to track the evolution of public attention and political priorities over time. This can help identify trends, influences and dynamics within the political and media landscape. This method of codifying and analysing agendas is a common technique in the social sciences, particularly political science and communication. It enables us to analyse not only what we talk about, but also how we talk about it, by highlighting the frameworks and narratives used to define and understand public issues. In short, agenda analysis is a valuable tool for understanding the political process and how public issues are defined and addressed. | |||

By using a coding grid with 200 different public policy categories, we can gain a very precise insight into the specific priorities and concerns addressed in different agendas. This grid includes a wide range of areas, such as the economy, the environment, monetary policy, education, health, housing, security, human rights and so on. Each of these categories could be subdivided into more specific issues or topics. By applying this coding grid to different agendas, whether in the media, political parties, governments, parliaments or even budgets, we can obtain precise quantitative data on the relative attention given to each area. This makes it possible to compare priorities between different actors, track changes over time, and identify trends or patterns in public and political attention. Such an analysis helps to understand the processes of agenda-setting, showing which issues are successful in attracting attention and which are ignored. This provides valuable information about how the political process works and the factors that influence political decisions. | |||

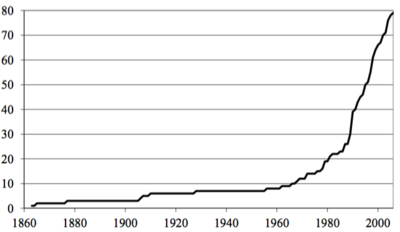

Analysis of multi-year data provides valuable insight into long-term trends and shifts in political and media priorities. This can reveal which issues have been perceived as most urgent or important over time. By coding over 22,000 parliamentary interventions in Switzerland, we gain a detailed insight into the issues that have been raised and the problems that have been prioritised by legislators. Questions, interpellations, postulates and parliamentary initiatives reveal the concerns of parliamentarians, their responses to public problems, and their commitment to taking action on specific issues. This analysis shows how political attention is divided between different areas, how priorities have changed over time, and which issues have managed to stay on the agenda or have been overshadowed by other concerns. This information is valuable for understanding not only current policy priorities, but also political dynamics and the factors that influence policy decisions. It also helps to inform discussions about the effectiveness of public policies, and to assess whether political efforts are aligned with the most pressing issues and concerns. | |||

Analysis of government press releases and coalition agreements can provide valuable information on government priorities and commitments. This is another facet of agenda analysis that can enrich our understanding of the political landscape. Government press releases often reflect the government's immediate priorities and the way it communicates its actions and policies. By analysing these press releases over a number of years, we can track changes in the government's agenda and observe how different issues and areas of public policy have been prioritised at different times. On the other hand, the coalition agreements that are negotiated at the beginning of the legislature can provide an insight into the government's long-term objectives and priorities. These agreements are often the result of complex negotiations between different parties, and they reflect the compromises and commitments that will guide government action over the coming years. These two types of documents - press releases and coalition agreements - can be coded using the same coding grid as that used for the media and parliament. This would allow a direct comparison of the priorities and attention given to different areas across the different institutions. | |||

In a Westminster-style parliamentary system such as that of the United Kingdom, the 'Speech from the Throne' (or 'Queen's Speech') is a key element to analyse. Traditionally, this is a speech made by the monarch (or his representative) at the opening of each new session of parliament. Although delivered by the monarch, it is drafted by the government of the day and sets out the main policies and legislative acts that the government intends to implement during the forthcoming parliamentary session. Analysis of this speech can provide valuable insight into the government's intentions and priorities. As it contains a list of the main legislative measures that the government plans to introduce, the Speech from the Throne can be seen as a "road map" for the parliamentary session. As part of an agenda analysis, we can code this speech to identify the main areas of public policy that are highlighted, and see how these compare with the attention given to the same areas in the media, parliament and other sources that can be analysed. It is also possible to track the evolution of these priorities over time by analysing successive years' Speeches from the Throne. | |||

Budget analysis is another very effective method of understanding a government's priorities. The budget is a clear statement of political intentions because it shows where the government chooses to allocate its resources. By analysing budget items, we can see which areas of public policy the government prioritises in terms of spending. By using the coding grid of 200 public policy categories, we can assign each budget item to a specific category. This makes it possible to see how much money is allocated to each area, to compare allocations between different categories, and to track changes in spending over time. It can also be useful for assessing whether budget spending matches priorities stated in other sources, such as speeches from the throne, coalition agreements or government press releases. For example, if a government states that education is a priority, but spending on education is only a small proportion of the budget, this could indicate a gap between rhetoric and action. | |||

The big question that arises once all these agendas have been coded over a long period of time in different countries is how to explain why certain themes are a priority in one agenda and another. This is a key area of research in political science and media studies. If the media and political actors focus on the same issues, it can be difficult to determine who is influencing whom. The media may highlight certain issues because they are important to public opinion, or because they are discussed by political actors. Similarly, political actors may focus on certain issues because they are highlighted by the media, or because they believe they are important to their constituents. To answer this question, it is necessary to carry out a detailed analysis of the relationship between the media and political actors, and to take into account many factors, such as the political and social context, voters' preferences, the influence of pressure groups, and many others. In terms of democracy, it is important that the media and political actors do not focus solely on the same issues, in order to ensure a plurality of voices and perspectives. If the media and political actors both focus on the same issues, this can limit public debate and prevent important issues from being discussed. Furthermore, if political actors focus primarily on issues that are popular in the media, this can lead to a form of media populism, where public policy is dictated by media preferences rather than the needs of society. It can also reduce the ability of political actors to tackle complex or controversial issues that may not be popular in the media. | |||

The question of who controls the agenda is central to understanding the power dynamics in a society and therefore has profound implications for democracy. By setting the agenda - that is, deciding which issues are worthy of attention and how they are framed - an actor can wield a great deal of power. This ability to set the agenda can influence public policy, public opinion and even the outcome of elections. Moreover, the question of who has the power to set the agenda can reveal who has power in a wider society, and can raise important questions about representation, equity and democracy. For example, if the agenda is predominantly controlled by a political or media elite, this may mean that some voices are marginalised or ignored, which can undermine democratic participation and equality. On the other hand, if the agenda is set in a more democratic way, for example by a combination of political actors, the media and ordinary citizens, this can facilitate a broader and more balanced debate. In short, analysing who controls the agenda is a complex task that requires an in-depth study of power dynamics, social and political structures, and the role of the media. | |||

=== Analysis and Understanding of Public Problems === | |||

Agendas can be analysed quantitatively, by measuring the relative importance that an agenda places on a specific public policy. This approach can reveal trends and patterns in the way issues are prioritised, and can help to understand how political priorities change over time. However, such a quantitative approach alone cannot explain why some issues make it onto the agenda and others do not. To understand these dynamics, a qualitative analysis is needed. This involves looking at how the actors who seek to put a problem on the agenda construct and present it in such a way as to attract the attention of political decision-makers. This construction of the issue may involve a number of strategies, such as framing the issue in such a way as to make it relevant to current political priorities, mobilising allies to support the cause, or finding ways of attracting media attention. Understanding how these strategies are employed and how successful they are can offer valuable insights into political processes and how decisions are made. | |||

Issues are not inherently political or newsworthy in themselves. They become political problems through the actors who highlight, define and present them as requiring the attention and intervention of government or public bodies. This idea is part of a framework of moderate constructivism, which recognises both the existence of objective events in the real world and the active role of social actors in interpreting, defining and constructing these events as political problems. This construction process is influenced by many factors, such as the interests of the actors, cultural values, political ideologies, institutional constraints and power relations. | |||

Let's take the example of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in agriculture. This complex subject is perceived and defined in different ways depending on the players involved and the context. For some, GMOs are primarily an agricultural issue: they wonder whether or not this technology will make it possible to increase agricultural productivity. Others see GMOs from an environmental angle. Some are concerned about the risk of genetic pollution caused by unintentional cross-breeding with non-modified plants. On the other hand, others highlight the potential benefits of GMOs for the environment, such as the reduction in the use of herbicides. There are also those who see GMOs through the prism of public health. For them, the debate is not about agricultural productivity or environmental issues, but about how our bodies react to GMOs. They wonder about the risk of developing allergies to certain GMOs once they have been incorporated into our diet, either directly or through livestock feed. Finally, some stakeholders define the problem of GMOs primarily in economic and power terms. For them, the crux of the debate concerns the major biotech companies, such as Monsanto. They believe that these companies, which are mainly North American, risk creating economic dependence by controlling the seed market, thereby creating an asymmetry between the North American market and those in other regions such as Latin America, India and Europe. | |||

In this case, GMOs (genetically modified organisms) can be perceived and constructed very differently depending on the players involved, their specific interests and their frames of reference. | |||

* For some, the debate on GMOs is primarily agricultural, focusing on the impact of the technology on agricultural productivity. | |||

* For others, it is an environmental issue, focusing on the risks of genetic pollution or the possibility of reducing the use of herbicides. | |||

* Some see it from a public health angle, focusing on the potential effects of GMOs on human health, particularly the risk of allergies. | |||

* Finally, there are those who approach the issue from an economic and political angle, focusing on the influence of large biotech companies and the risk of global economic imbalances. | |||

This multiplicity of perspectives illustrates the concept of constructivism in politics: the meaning and importance of a problem are socially constructed, not objectively given. It also demonstrates the extent to which the process of setting the agenda and defining a problem is complex and subject to constant struggle and negotiation between different players with different interests and perspectives. | |||

The way in which a problem is perceived and defined can greatly influence its presence on the political agenda. In the case of GM food, different dimensions of the issue are likely to capture the attention of policy-makers. However, the perception of the seriousness of the problem varies considerably depending on the dimensions considered. For example, if the issue of GMOs is considered primarily from an environmental perspective, it may gain in visibility, particularly because of the growing importance of environmental protection in public opinion and political priorities. On the other hand, if the debate focuses on the economic inequalities potentially caused by the domination of certain large companies, the issue may be perceived as more complex or conflictual and, as a result, may encounter more resistance to its entry onto the political agenda. | |||

The notion of framing is a key aspect of public policy analysis. This concept refers to the way in which a problem is presented or interpreted. The framing of an issue can strongly influence how it is perceived, understood and prioritised by policy-makers, the media and the public. In the context of public policy, framing can be a strategy used by various actors (e.g. interest groups, researchers, politicians, journalists) to highlight certain aspects of a problem, while downplaying or omitting others. By carefully choosing how to frame an issue, these actors can help determine whether and how an issue is addressed in policy-making. Therefore, understanding framing mechanisms and being able to use them effectively is an essential skill for those wishing to influence the policy agenda. | |||

=== Recognition and consideration of public issues === | |||

Getting an issue onto the political agenda is a complex and multifaceted process, and there is no guarantee that any given issue will go through all the necessary stages. For an issue to be recognised and addressed in policy development, it must overcome a number of hurdles. The first step is usually to bring the issue to the attention of the public and policy makers. This may involve raising awareness of the issue, mobilising the support of relevant stakeholders and presenting convincing arguments about the urgency and importance of the problem. The second stage often involves clearly defining the problem and proposing viable solutions. This may involve research, consultation and sometimes negotiation to overcome differing views and conflicting interests. Even once these steps have been taken, the problem still needs to be placed on the political agenda, which often requires the support of political decision-makers. Sometimes, despite the best efforts of advocates, an issue may be pushed off the political agenda because of political constraints, limited resources or other competing priorities. Finally, once an issue is on the political agenda, policies to address it must be developed, adopted and implemented. Each stage of this process presents its own challenges and potential obstacles. So even if a problem is identified and there is consensus on the need to address it, there is no guarantee that it will reach the public policy stage. That's why it's important to understand how the policy process works and to be actively engaged at every stage to maximise the chances of success. | |||

[[Fichier:Varone 2015 app mise à agenda et formulation 1.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | |||

This diagram represents the long road that the promoters of a public problem must follow in order to build it. | |||

==== Moving the Problem from the Private to the Public Sphere ==== | |||

The transition from the private to the public sphere is often the result of a collective awareness, a mobilisation of stakeholders or a triggering event. It is at this stage that a private or individual issue is transformed into a societal problem requiring a political or collective response. For example, a disease that affects a large number of individuals privately may be recognised as a public health problem requiring collective action, more intensive medical research or specific public policies. Similarly, a situation of social inequality may initially be perceived as an individual or private situation, but once it is recognised as being systemic or structural, it can then be transformed into a public problem requiring a political response. This transition from private to public is often facilitated by social actors, such as associations, pressure groups or activists, who work to make the problem visible, raise awareness among the public and political decision-makers, and mobilise the support needed for the problem to be recognised as a public issue requiring collective action. This is often referred to as 'putting the issue on the agenda'. | |||

The first stage in transforming a private problem into a public one is often the most difficult. The lack of social recognition of the problem is a major obstacle at this stage. Individual mobilisation is often difficult, as people may not realise that their problem is shared by others, or they may feel isolated or powerless. In addition, there may be a social stigma or lack of understanding that prevents people from talking openly about their problem. Several factors can contribute to the lack of social recognition of a problem. For example, a lack of visibility may prevent people from realising the extent of the problem. The problem may also be ignored or minimised, either because of a lack of information or because of prejudice or unfavourable attitudes towards the people affected. The lack of individual or collective mobilisation can also play a major role. Without a voice to articulate the problem and bring it to public attention, it can easily remain in the shadows. Non-governmental organisations, rights groups and activists often play a crucial role at this stage by giving visibility to the problem, mobilising support and advocating for the problem to be recognised as a public issue. The aim is to move the problem from the private to the public sphere, to have it recognised as a social problem that requires a collective or political response. | |||

The transformation of a private situation into a public problem often requires the intervention of one or more influential players for the problem to be recognised on a wider scale. In the case of domestic violence, incest or doping in sport, although these problems are statistically significant, they are often hidden in the private sphere, which makes it difficult to recognise them as social problems. However, the intervention of a public figure - for example, a politician who reveals that he or she has been a victim of domestic violence - can catalyse attention to the problem. This revelation can be the trigger that leads the media, political parties and public opinion to recognise the problem. The phenomenon of sudden and collective awareness of the scale of a problem is sometimes called the "revelation effect". This effect can be triggered by a major event, a revelation, a scandal, or a public figure speaking out. Once a problem has been brought to public attention in this way, it is more likely to be taken into account by political decision-makers and to become a subject for public action. This dynamic highlights the importance of the role of the media, political actors and activists in shaping public issues. | |||

==== Placing on the Agenda by the Political Authorities ==== | |||

Once an issue is recognised as a social or collective problem, it has to go a step further to be considered a public problem. This means that it is seen as requiring a government or political solution, rather than simply a response from civil society or non-governmental organisations. In this process, the issue must be sufficiently serious, urgent or widespread to justify intervention by the public authorities. It is essential to stress that not all social problems become public problems. This often requires the ongoing mobilisation of the players concerned, media coverage of the issue and the political will to respond. It is therefore a delicate stage in the problem-building process, as it involves convincing a wider public and political decision-makers of the importance and necessity of tackling the issue at a political and institutional level. The players involved in this phase can be diverse, ranging from interest groups, the media and experts to politicians themselves. | |||

It is important to understand that the fact that an issue is identified as a social or public problem does not automatically guarantee that it will become a political priority or appear on the political agenda. Setting the political agenda is a complex process that depends on many factors. It may include the current political environment, existing government priorities, available resources, public opinion, advocacy campaigns, recent events, among others. In some cases, although the issue is recognised as a problem requiring policy intervention, it may be overshadowed by other issues deemed more urgent or relevant. On the other hand, some issues may be politically sensitive and provoke resistance or controversy, which may also delay or prevent their inclusion on the political agenda. It is also important to note that the political agenda is dynamic and subject to change. Consequently, an issue that is not currently considered a political priority may become one at a later date due to changes in the political, social or economic context. | |||

Some sensitive issues, such as paedophile rings and child labour, although widely recognised as serious societal problems, may find it difficult to get onto the political agenda for a variety of reasons. This may be due to the sensitive nature of these issues, which can make dealing with them politically complex and potentially controversial. Politicians may be reluctant to tackle these issues head-on because of the potential consequences for their public image and electoral support. On the other hand, there may be a lack of political will to address these issues, especially if solving them requires significant resources or profound structural changes in society or the economy. | |||

The concept of 'non-agenda setting' or 'non-decision' is very important in public policy analysis. It refers to the situation where, although the seriousness of a problem is recognised, it is not treated as a priority or not addressed at all by the political authorities. | |||

There are several reasons why a problem may be omitted from the political agenda: | |||

* Possible solutions are controversial or politically risky: If solving a problem requires taking action that is likely to be unpopular or controversial, politicians may choose not to put it on the agenda to avoid political cost. | |||

* Lack of resources: Solving a problem may require a substantial investment of time, money and other resources. If these resources are not available or could be better used elsewhere, the problem may be omitted from the agenda. | |||

* Solutions are complex or uncertain: If a problem is particularly complex or the solutions are unclear, politicians may choose not to put it on the agenda until a clearer solution is found. | |||

* Lack of public support: For an issue to be placed on the agenda, there generally needs to be some level of public support. If the public does not perceive the issue as a priority, it can be difficult for politicians to justify putting it on the agenda. | |||

* Influence from lobby groups or vested interests: In some cases, lobby groups or vested interests can use their influence to prevent an issue from being placed on the agenda. | |||

These 'non-decisions' have important implications for democracy and governance, as they can allow serious problems to persist unresolved. | |||

One of the most cited articles in political science is Peter Bachrach and Morton Baratz's 1962 article "Two Faces of Power", which puts forward the idea that power manifests itself not only in the decisions that are made, but also in the art of controlling the political agenda.<ref><nowiki>http://www.columbia.edu/itc/sipa/U6800/readings-sm/bachrach.pdf</nowiki></ref> According to Bachrach and Baratz, there are two faces of power. The first is the ability to influence the decisions that are made, i.e. to ensure that certain actions are taken by political institutions. This is the most visible and most often analysed form of power. However, they argue that there is a second, perhaps even more important, side to power: the ability to control the agenda and determine which issues and topics will or will not be discussed in the public arena. This second face of power is much more subtle and difficult to detect, because it concerns "non-decisions", i.e. issues that are intentionally or systematically avoided or excluded from the political agenda. For example, a powerful interest group can exert its power not only by influencing political decisions in its favour, but also by ensuring that certain issues that could threaten its interests are not addressed or debated publicly. This approach has been extremely influential in the study of power and influence in political science and sociology, and remains central to contemporary public policy analysis. | |||

The act of 'non-decision', or the deliberate choice not to put a specific issue on the political agenda, is in itself a form of political action. It is what is often called a "politics of inaction". It is a passive decision that has consequences just as important as active decision-making. In other words, when politicians choose not to address a problem, they are making a default decision on how that problem will be dealt with: it will either remain unaddressed or be left to other actors, whether individuals, non-governmental organisations or the market. By failing to act, the political authorities are in effect deciding to maintain the status quo or to let the problem resolve itself, which can have very real consequences. For example, a 'non-decision' on regulating greenhouse gas emissions implicitly contributes to the problem of climate change. This is why the analysis of 'non-decisions' is an important aspect of the study of public policy and political power. It allows us to understand not only what governments do, but also what they do not do, and why. | |||

Even if a social problem manages to be thematised and reach the political agenda, this does not guarantee that concrete measures will be taken to resolve it. Moving on to the formulation phase of a public policy often involves a series of negotiations and compromises between different political players, and generally requires a certain level of consensus. If this consensus is lacking, or if opinions diverge too widely on the best way to deal with the problem, the process can stagnate. In this case, although the problem is recognised as a matter for public action, no specific policy is adopted to deal with it. This is a common scenario in many areas of public policy, where debate and controversy can prevent the advancement of potential solutions. The issue may remain on the political agenda for a long time, without any concrete action being taken. This can lead to frustration among stakeholders and the public, and contribute to a sense of political stasis. | |||

The example of maternity insurance is a perfect illustration of how long and complex the process of implementing public policy can be. Despite constitutional recognition, it took several decades for maternity to be recognised as a condition deserving of insurance cover. As for the Tobin tax on financial transactions, it is another example of the difficulty of transforming a concept into an implemented policy. First proposed in 1972 by economist James Tobin, the tax would aim to reduce speculation on financial markets by taxing international transactions. Despite the support of certain political figures and organisations, it has never been implemented on a global scale, demonstrating once again the complexity of political processes. | |||

Defining a public problem is a complex process that requires various stages to be overcome. Public policy researchers interested in how problems are constructed and put on the agenda seek to understand the dimensions that actors manipulate to construct a problem and how they succeed in putting a problem on the agenda. This involves identifying the key elements that determine how a problem is perceived and understood, and the factors that facilitate or hinder its inclusion on the political agenda. This could include factors such as the presence or absence of public or political consensus, the perceived seriousness of the problem, the availability of feasible solutions, and the political, economic or social interests at stake. These dimensions can vary considerably depending on the context and the specific problem, and understanding these dynamics is essential for those seeking to influence the policy agenda. | |||

== Strategy for Problem Construction == | |||

Empirical research suggests that issues that succeed in getting onto the political agenda often have certain characteristics. These are not necessarily objective characteristics, but characteristics that can be constructed. | |||

=== Labelling the problem === | |||

A common feature of problems that reach the political agenda is that they are often presented as being particularly severe. Those seeking to promote the problem try to persuade policy-makers of the seriousness of the situation and the potentially dramatic consequences of inaction. This serves to instil a sense of urgency and to encourage decision-makers to act to prevent or mitigate these negative consequences. | |||

The choice of terms used to describe a problem can greatly influence the perception of its seriousness. By using strong or alarming labels, those seeking to put a problem on the political agenda reinforce the idea of the severity of the situation and the potentially disastrous consequences of inaction. Using the right terminology is therefore crucial to attracting the attention of decision-makers and the public, and raising collective awareness of the problem. | |||

=== Defining the scope of the problem === | |||

The second dimension, that of scope, complements the first. It raises the question of the extent of the problem's impact: how many people are affected and to what extent? In theory, the more people a problem affects, the more likely it is to attract the attention of political decision-makers. However, the impact of a problem cannot be measured solely in terms of the number of people affected. The very nature of the people affected, i.e. their status, their role in society or their vulnerability, can also play a determining role in assigning political importance to the problem. | |||

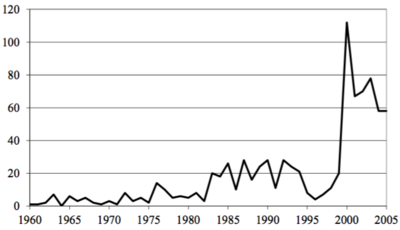

A particularly interesting analysis has been made of the attention given to AIDS by policy-makers in the US Congress. Today, although AIDS is not a dominant topic in our public debates, it is interesting to note that there is not always a direct correlation between the objective scale of a public health problem and the attention it receives from politicians. | |||

These researchers found that the attention paid to the AIDS problem by the US Congress and the budget allocated to combating it have varied significantly over time. They therefore asked what factors explain these variations. Their analysis revealed that these changes were largely influenced by the perception of who was affected by the AIDS problem. In other words, the way in which the problem was 'framed' or 'presented' politically, and the way in which interest groups and associations defined AIDS victims, played a crucial role in determining the attention given to the problem by politicians. | |||

At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, the problem was often perceived as affecting mainly certain marginalised groups, such as homosexual men or intravenous drug users. However, as the epidemic progressed, it became clear that the virus was affecting a much wider population. When AIDS began to be perceived as a problem affecting a wider public, including heterosexuals and children, the attention paid to the problem by politicians and the funding allocated to combating it increased. This example illustrates how the perception of an issue's audience - who is affected by it - can influence the political attention given to it. This perception of the audience can be influenced by the way in which the problem is 'framed' or 'presented' in political discourse and by interest groups. | |||

When AIDS was mainly associated with socially marginalised or stigmatised groups, such as homosexuals and intravenous drug users, there was less political will to tackle the problem seriously. Some of the rhetoric at the time was extremely prejudicial and suggested that AIDS could be a form of 'self-elimination' for these marginalised groups. These attitudes contributed to a lack of attention and resources devoted to the fight against AIDS. | |||

Magic Johnson's revelation in 1991 that he had been diagnosed as HIV-positive radically changed the perception of HIV/AIDS. Until then, HIV/AIDS had been widely regarded as a disease that mainly affected the gay community and drug users. But when Magic Johnson, a highly respected sportsman known for his heterosexual behaviour, revealed that he had HIV, it changed the way the disease was perceived and understood by the general public. This announcement helped to broaden the scope of the problem, showing that HIV/AIDS was not limited to certain marginalised groups, but could affect anyone, including world-famous athletes. This led to a significant increase in awareness and attention to HIV/AIDS, not just in the US but around the world. This has led to an increase in funding for research and the development of treatments, as well as for prevention and education programmes. This is a striking example of how perceptions of who is affected by a problem can influence the political attention and resources devoted to solving it. | |||

The revelation that the HIV/AIDS virus had infected the haemophilia community through transfusions of contaminated blood marked a new stage in the public and political perception of the disease. People with haemophilia are generally regarded as innocent patients who contract the disease through no fault of their own, in contrast to the prejudice often associated with homosexual communities and drug users. This new hearing has drawn attention to systemic problems in the healthcare system and blood safety issues. It has also highlighted the need for a more robust public health policy to prevent the spread of the virus, including better blood screening and safer treatment protocols. Thus, the widening of the HIV/AIDS audience to larger and more diverse groups in society has played a key role in increasing the political attention given to the disease and in formulating more effective policies to combat it. | |||

Identifying an audience concerned by a problem is a crucial step in drawing political attention to a given issue. The wider and more diverse the range of people affected, the more likely it is that the problem will be recognised as a matter of public interest requiring state intervention. The strategy for broadening the scope may include various social groups. The groups affected may be defined by common characteristics, such as disease, profession, sexual orientation, age or even place of residence. In addition, this perimeter may evolve over time, depending on new information available, societal developments, or the actions of different actors, whether they be victims, support groups, researchers, journalists, or politicians. These actors can use various means to raise awareness of a problem among public opinion and political decision-makers, such as awareness campaigns, testimonies, scientific studies, news reports, lobbying or demonstrations. As the scope of the problem widens and more attention is paid to it, the chances of it being placed on the political agenda and of measures being taken to resolve it increase. | |||

=== Characterisation of the Novelty of the Problem === | |||

The novelty of a problem can attract greater attention from policy-makers and the public. Interest in new problems can be linked to a number of factors. | |||

Firstly, new problems may seem more urgent or important because they are perceived as emerging threats that require a rapid response. In addition, they may be less fraught with past controversy or political debate, which can make decision-making easier. Secondly, politicians may be interested in new problems because they offer opportunities to stand out and show leadership. They can present solutions to these problems as political innovations and use them to bolster their public image. Finally, new issues can capture the attention of the media and the public, who are often attracted by new and topical subjects. This can create public pressure for political decision-makers to act. However, the fact that a problem is new does not guarantee that it will be addressed. Many other factors, such as the seriousness of the problem, the number of people affected and the availability of possible solutions, can also influence how issues are addressed on the political agenda. | |||

Environmental and pollution issues have followed this trajectory, constantly reinventing themselves to remain relevant on the public and political agenda. Air pollution was first seen as a localised problem (urban smog), but was later reconfigured as a threat to forests and finally as a contributor to global climate change. In a similar way, the current debate on fine particles and air pollution in urban areas represents a new iteration of this persistent problem. By reframing the problem of air pollution in terms of public health, environmental campaigners have succeeded in keeping the issue on the public and political agenda. This illustrates a key tactic used by those seeking to influence the political agenda: constantly reframing and redefining an issue to keep it on the agenda. This process can involve identifying new dimensions of the problem, connecting the problem to other problems perceived as more pressing, or highlighting the impacts of the problem on new groups of people. The ability to effectively reframe a problem is often crucial in attracting the attention of the media, the public and policy-makers. It is a key skill for campaigners, lobbyists and others seeking to influence the political agenda. | |||

The | === Representation of the problematic situation === | ||

The urgency of a problem is another critical dimension that can influence its prioritisation on the political agenda. By representing a situation as a crisis, stakeholders can create additional pressure for rapid political intervention. This can help overcome political inertia and encourage immediate action. The representation of a situation as a crisis can be fuelled by various factors, such as the apparent scale of the problem, the scale of its impact, the speed at which it is worsening, or the perception that significant adverse consequences may result from inaction. This perception may be reinforced by alarmist messages in the media, by public attention, by scientific evidence or studies, or by dramatic events linked to the problem. However, it should be noted that the use of crisis rhetoric can have harmful effects. If used excessively or unjustifiably, it can contribute to general cynicism and crisis fatigue among the public and politicians, which can ultimately undermine the effectiveness of the strategy. | |||

The | The nature of some problems lends itself more easily to the construction of urgency. Dramatic events such as terrorist attacks or epidemics generally provoke an immediate political response because of their sudden and potentially devastating impact. On the other hand, problems that develop more slowly or less visibly can be more difficult to represent as urgent. For example, the gradual degradation of the landscape may not seem immediately threatening to many citizens or politicians. However, if left untreated, it could have long-term consequences for the environment, human well-being and the economy. In such cases, stakeholders often have to resort to creative strategies to emphasise the urgency of the situation. This may involve using scientific evidence, highlighting the potentially serious long-term consequences of inaction, or linking the problem to other more visible or pressing issues. For example, the Swiss Foundation for Landscape Conservation might link landscape degradation to more immediate problems such as biodiversity loss, increased flooding due to soil erosion, or the impact on tourism and the local economy. | ||

In the complex world of public policy, competition for attention and resources is often fierce. There are many important issues that need to be addressed, but resources (be they time, money or political will) are limited. This is particularly true in times of crisis, or when other more urgent or visible issues arise. To avoid being overshadowed by other issues, advocates may have to fight continually to keep their issue on the public agenda. This may involve various strategies, such as building alliances with other groups, seeking popular or media support, or lobbying politicians. However, even with these efforts, it can be difficult for some issues to gain the attention and resources needed to be effectively addressed, particularly if they are perceived as less urgent or less directly linked to the immediate interests of the public or politicians. | |||

== | === Identifying the causes of the problem === | ||

When constructing a public problem, two essential aspects are defined: the causes of the problem and those who suffer its consequences. By specifying the causes, we identify and point the finger at the actors who may be seen, in the political discourse, as responsible or even guilty for the problem. The question is to determine which causes we are able to put forward to explain the nature of the problem we are seeking to resolve. | |||

The | Identifying the causes of a problem is a crucial step in developing public policy. The way in which these causes are defined has a direct impact on the type of solutions that will be proposed and the players who will be involved in implementing them. The responsibilities assigned at this stage can also have significant political implications. Take the example of the debate following the collapse of houses after an earthquake in Morocco. Interpretations of the cause of this event can vary considerably and lead to different proposed solutions. If the earthquake is seen as an unpredictable and irrepressible natural accident, this leads to a resilient approach to public policy. In this scenario, the emphasis would be on measures such as improving emergency preparedness, training residents in earthquake response, and developing post-disaster response plans. If, on the other hand, the collapse of houses is considered to be due to negligence on the part of the state or other local actors, this opens the way to a preventive and regulatory approach. The solutions envisaged could include the development of stricter anti-seismic building standards, the designation of no-build zones on particularly seismic land and the application of penalties to players who fail to comply with these regulations. In conclusion, the way in which the cause of a public problem is defined directly influences the types of solutions that will be proposed, as well as the players who will be involved in implementing these solutions. It is therefore essential to understand and analyse the causes of a problem before formulating public policies to deal with it. | ||

It is true that attributing the cause of a problem to an intentional action can greatly influence the nature of the public policies envisaged and the responsibility of the players involved. If, in the case of the collapse of houses after an earthquake, the State had demarcated seismic zones and adopted stricter building standards for these zones, but these measures were deliberately ignored or circumvented, this could give rise to punitive measures and stricter regulations. For example, if property developers or builders intentionally ignored these regulations to maximise their profits, they could be held responsible and face legal sanctions. In addition, the state could tighten up its regulations and building controls in seismic zones to prevent future house collapses. Similarly, if the state itself is found liable for failing to properly implement or enforce its own regulations, this could lead to changes in governance, such as the introduction of new accountability mechanisms or changes to construction approval processes. However, whatever the attributed cause of the problem, it is essential to approach the situation holistically, taking into account not only the causes, but also the effects and underlying factors. This will help to create more effective and sustainable solutions to the problem in the long term. | |||

Problems that can be attributed to an intentional cause are often more easily recognised and dealt with because they have clearly identified culprits. This gives policy-makers leverage to respond to the problem, whether through legal sanctions, increased regulation or incentives to change behaviour. The attribution of an intentional cause can also elicit a stronger emotional response from the public, which can increase the pressure on policy-makers to act. Anger, outrage and a desire for justice can be powerful drivers for putting an issue on the agenda and motivating action. However, it is important to note that intentional causation can also have negative consequences. For example, it can contribute to the stigmatisation of certain groups, create divisions within society and make it more difficult to find constructive solutions. It can also distract attention from more complex or structural causes that also need to be addressed. Finally, it is important to ensure that the attribution of an intentional cause is based on solid evidence. Falsely accusing individuals or groups can lead to injustice and distrust in the institutions that are supposed to be solving the problem. | |||

When reading the press and learning about public problems, it is important to analyse and understand the causes presented. This involves not only discerning whether the attributed cause is accidental, negligent or intentional, but also critically examining the evidence presented to support this attribution. Bearing in mind that problems attributed to an intentional cause may be more likely to attract attention, we need to be vigilant to ensure that this attribution is not used to sensationalise or unduly stigmatise certain groups. It is also essential to recognise that many public problems are complex and can be influenced by a combination of accidental, negligent and intentional causes. Ultimately, a critical reading of information is necessary to understand the nuances of public issues and to be an informed and engaged citizen. | |||

=== Problem Complexity Assessment === | |||

Problems that are simple and easy to understand tend to capture the public's attention more easily and make their way onto the political agenda. This may be due to a number of factors. Firstly, humans naturally tend to prefer simple, clear explanations. We are more inclined to understand and retain information that is presented in a concise and direct manner. This is why political messages or awareness campaigns based on simple, straightforward explanations tend to be more effective. Secondly, complex issues often involve many stakeholders, each with their own interests and perspectives. This can make it difficult to make decisions and develop a clear plan of action. Thirdly, complex problems may also require equally complex solutions, which may take significant time, resources and effort to implement. This can discourage policy makers from tackling these problems. However, it is important to note that oversimplifying problems can also be detrimental. It can lead to ineffective or inappropriate solutions, or to the neglect of important aspects of the problem. It is therefore crucial to balance simplicity and complexity when developing policies and informing the public. | |||

Identifying scapegoats or stigmatising certain groups can be a political strategy used to simplify more complex problems and capture the public's attention. It is a practice that can lead to polarisation, division and sometimes discrimination. Take, for example, the regulation of top managers' bonuses as a solution to the financial crisis. Admittedly, these bonuses can encourage risky behaviour and contribute to the creation of financial bubbles, but they are not the only cause of financial crises. Other factors such as inadequate financial supervision, lack of transparency in financial markets and structural problems in the financial system also play a role. In this case, simplifying the problem and focusing on executive bonuses can distract attention from these other important factors and therefore prevent the adoption of more comprehensive and effective solutions. This is why it is important for policymakers, the media and the general public to understand the complexity of political and economic problems and to resist the temptation to look for simple solutions or to blame specific groups for complex problems. A more nuanced and holistic approach is generally needed to address these issues effectively and fairly. | |||

=== Quantifying the problem === | |||

Quantification is an essential aspect of problem definition in policy. It provides an objective measure of the scale or importance of a problem, and can help to identify priority areas for intervention. For example, in public health, the number of deaths or illnesses can indicate the urgency of tackling a particular disease or condition. In the field of economics, indicators such as the unemployment rate, GDP or inflation are used to assess the state of the economy and determine the necessary policies. | |||

Quantification can also make a problem more concrete and understandable for the general public and decision-makers. It can also make it easier to monitor and evaluate the policies put in place to solve the problem. In some cases, the problem can be monetised, i.e. given a monetary value. This can help to assess the costs and benefits of different proposed solutions. For example, in the case of environmental problems, monetising the costs of environmental damage can help to justify environmental protection policies. However, it is important to note that not all problems can be easily quantified or monetised, and some important aspects may be overlooked in the process. Furthermore, quantification and monetisation can sometimes oversimplify a complex problem, which can lead to ineffective or unfair policies. | |||

Air pollution is a perfect example of how quantification can help put a problem on the political agenda. The harmful effects of air pollution on human health are well documented. Scientists have established direct links between exposure to certain fine particles or radioactive substances and various health problems, including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, and even certain types of cancer. However, these effects are generally only apparent when epidemiological studies have been carried out to quantify the impact of air pollution on human health. These studies make it possible to gather data on the number of people affected, the severity of the effects on health, and so on. They therefore make the problem more concrete and can serve as a basis for calls for action. Similarly, measuring air quality, for example in terms of concentrations of fine particles or levels of radioactivity, makes it possible to identify problem areas and can serve as a basis for developing environmental policies. However, it is also important to note that quantification only gives part of the picture. It does not necessarily capture all the impacts of air pollution, such as effects on the ecosystem or quality of life, and it can sometimes mask inequalities in the way air pollution affects different populations. | |||

The construction of | The construction of a problem requires a certain capacity on the part of the players involved. This is particularly the case when it is necessary to collect, analyse and present data to quantify a problem. Quantifying a problem may require specific skills, such as the ability to conduct scientific research or statistical analysis. In addition, resources may be needed to collect data or to call on experts to carry out this work. Highlighting the nature of the problem is another important skill. This may involve the ability to tell stories that draw attention to the problem, run awareness campaigns, mobilise support or exert political influence. Ultimately, the ability to gain recognition for a problem depends to a large extent on the actors' ability to navigate the political and social landscape, mobilise the necessary resources and effectively articulate the nature and importance of the problem. | ||

This | == The Key Players in Agenda Setting == | ||

Why does a problem follow this causal path to its conclusion? This may be due to certain intrinsic characteristics of the problem that reflect the way it is structured by the various stakeholders. This could include the seriousness of the problem, its scale, its quantification or objectification, or the identification of an intentional cause. In addition, it is essential to determine who are the actors involved in the construction of these problems. Who has the ability to influence decisions about problem definition? In short, we need to ask who is responsible for constructing the public problems on the agenda. | |||

Various approaches and theoretical hypotheses have been proposed in the literature. Five are fairly dominant, and there is very convincing empirical evidence for these hypotheses. | |||

=== Media coverage model === | |||

According to this model of mediatisation, the media play an essential role in shaping the political agenda. Their ability to focus public attention on specific issues can influence the priorities of political decision-makers as they seek to address the concerns of their constituents. This pattern can be seen in situations where politicians prioritise issues that are widely covered by the media, even if they are not necessarily the most urgent or strategically important. For example, an issue such as climate change may remain on the margins of the political agenda until it is widely covered by the media, raising public awareness and concern. This can spur politicians into action, either by drafting legislation to combat climate change or by committing to adopting greener practices. It is also important to note that the role of social media in shaping the political agenda is becoming increasingly significant. Social media platforms allow campaigns or movements to grow rapidly, sometimes leading to a political reaction. This is the case, for example, with the "Black Lives Matter" movement or campaigns to raise awareness of specific health problems. However, this model also presents risks. The media can sometimes accentuate or distort certain issues, which can lead to a distorted representation of their importance or urgency. In addition, the media news cycle is often much faster than the political process, which can lead to pressure for quick responses rather than thoughtful, sustainable solutions. In sum, the media literacy model suggests that the political agenda is heavily influenced by the media, but this influence needs to be balanced by critical and considered consideration of the issues that deserve political attention. | |||

The media play a crucial role in bringing to light issues that may not be immediately visible to the public or to politicians. Investigative journalism is a perfect example, where the rigorous and detailed work of journalists can uncover financial, political or environmental scandals. These revelations, once disseminated by the media, can provoke a strong reaction from public opinion and become a priority on the political agenda. An obvious example is the Watergate scandal in the United States in the 1970s. The Washington Post's investigative journalism exposed illegal practices at the highest level of government, leading to the resignation of President Nixon. This is a case where the media directly influenced the political agenda. The case of dangerous dogs is another interesting example. This issue, although perhaps considered minor by some, can suddenly gain visibility and urgency if the media start covering incidents involving dangerous dogs. This may lead to a call to action for stricter regulations on the ownership of certain breeds of dog. | |||

However, while recognising the crucial role of the media in shaping the political agenda, it is also important to remember that media coverage can sometimes be selective and influenced by various factors, such as the target audience, the media's political orientation or commercial interests. This means that some issues may be overexposed while others are ignored, which in turn can have an impact on the balance of the political agenda. | |||

=== Political Offer Hypothesis === | |||

The idea that the political offer (i.e. the themes and issues that politicians put forward during election campaigns) shapes the governmental and parliamentary agenda is a widely accepted assumption. The priority themes of an election campaign often reflect the promises made by candidates to the electorate, and once elected, these candidates are generally required to implement these promises. Thus, during the campaign, candidates highlight specific problems (such as the economy, education, health, security, etc.) and propose solutions or policies to resolve them. These problems and solutions then constitute the candidate's political offer. If the candidate is elected, these problems become a priority for the government and parliament. The newly elected politician is expected to address these issues head-on and is therefore likely to try to put them on the political agenda. | |||

This hypothesis is based on the idea that political parties actively shape the governmental and parliamentary agenda by highlighting certain issues during election campaigns. Once elected, they strive to keep their electoral promises, which leads to the integration of these issues into the political agenda. Take the example of radical right-wing parties and immigration issues. These parties often attach major importance to immigration during their campaigns, with strict policy proposals on the subject. Studies show a strong correspondence between the priority given to immigration by these parties during the election campaign, their parliamentary interventions on the subject once elected, and the importance of immigration in public and political debate. This suggests that the discourse of political parties during the election campaign may be a predictive indicator of the issues that will take priority in the next legislature. It is therefore important, according to this hypothesis, to carefully examine the electoral promises of the political parties in order to understand what issues will be on the agenda of the government and parliament once the election is over. | |||

These first two hypotheses - that of media coverage and that of the political offer - tend to play down the influence that private actors or associations can have in the construction of public problems. However, it is clear that these groups, including interest groups, lobbies and pressure groups, often play a crucial role in this process. One example of this influence is the model of silent corporatist action. According to this model, interest groups or lobbies can formulate specific demands that only concern their own field of activity, but which nevertheless manage to attract the attention of political decision-makers. These groups can quietly influence the political agenda by asserting their specific interests, proposing solutions to specific problems or highlighting issues that would otherwise have been overlooked. It is therefore essential to take account of the influence of these actors when analysing the construction of public problems. Although their influence may be more discreet or specific than that of the media or political parties, it is no less significant. | |||

It is common for specific professional groups, such as farmers or bankers, to use this agenda-setting strategy. Through their professional associations - for example, the Swiss Farmers' Union, the Swiss Bankers' Association or the Private Bankers' Association - they anticipate problems that may directly affect their field. By identifying a problem in advance, these groups can propose solutions even before the problem becomes a major public issue. This allows them to make direct requests to the political parties or government departments concerned, putting the issue on the political agenda. Generally, these groups will also want to ensure that it is their solution that is taken into account by the government. In this way, they will seek to obtain some sort of endorsement from the state for solving the problem. This strategy enables them not only to control the political agenda, but also to prevent other parties from taking control of the issue that concerns them. This shows just how decisive the influence of private players and associations can be in shaping public problems. | |||

Silent corporatist action is generally carried out through lobbying, a practice that is generally discreet and receives little media coverage. These activities, although sometimes politicised by certain parties, often remain out of the spotlight. However, their impact should not be overlooked. Indeed, these actions often lead to certain subjects or problems being placed on the agenda of the government or parliament. In this way, these private interest groups are able to have a considerable influence on public debate, even if their activity is not always visible to the general public. | |||

=== Influence of the New Social Movements === | |||