« From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 162 : | Ligne 162 : | ||

[[Fichier:McKinley Prosperity.jpg|thumb|Election poster from 1900 showing McKinley standing on the gold standard supported by soldiers, sailors, businessmen and workers.]] | [[Fichier:McKinley Prosperity.jpg|thumb|Election poster from 1900 showing McKinley standing on the gold standard supported by soldiers, sailors, businessmen and workers.]] | ||

The Spanish-American War was a crucial milestone, not only in the evolution of American foreign policy but also in the position of the United States on the world stage. The conflict, triggered primarily by the mysterious sinking of the USS Maine and fuelled by the impassioned appeals of the newspapers of the day - a phenomenon known as 'yellow journalism' - saw the United States fighting alongside Cubans, Filipinos and Puerto Ricans to liberate these territories from Spanish colonial rule. The swift and decisive victories of American forces in both Cuba and the Philippines highlighted the rise of American military power. In Cuba, the famous charge of the Light Brigade at San Juan Hill, in which future President Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders took part, has become an icon of American military valour. In the Philippines, the rapid destruction of the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay proved the power of the American navy. The Treaty of Paris, which concluded the war, transformed the United States into a colonial power. The US acquired Guam, Puerto Rico and paid $20 million for the Philippines, consolidating its presence in the Caribbean and Pacific. Although Cuba was freed from Spanish colonialism, it fell under American influence and became a de facto protectorate of the United States, marking the beginning of a complex and tumultuous relationship between the two nations. The Spanish-American War had far-reaching repercussions. Not only did it enhance the international stature of the United States, propelling it to the rank of world power, but it also gave rise to internal debates about America's role in the world. Overseas expansion and imperialism became issues of contention, underlining the tensions between the country's global aspirations and its founding principles of freedom and self-determination. | |||

The Spanish-American War occurred during the presidency of William McKinley, which represented an era of transformation in American politics, marking a marked shift from a domestic focus to a renewed involvement in global affairs. The conflict arose from both internal and external pressures, including the rise of the European powers, the rapid expansion of American industry and the economy, and the growing desire of the United States to protect and expand its interests overseas. The impetus for war was precipitated by the sinking of the USS Maine and exacerbated by yellow journalism, which helped inflame public opinion in favour of conflict. Although McKinley was reluctant to commit the country to war, he was forced to do so by pressure from Congress and public opinion. He oversaw an effective military campaign, using American naval power and ground troops to achieve decisive victories against Spain. Victory in the Spanish-American War had far-reaching implications. The United States acquired Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines, laying the foundations for an American colonial empire. Cuba also gained independence, but under American tutelage, signalling an era of increased American intervention in international affairs. The war propelled the United States onto the world stage, solidifying its status as a global power and ushering in an era of more assertive foreign policy. The conflict also underlined the importance of a strong, modern navy. Military modernisation became a priority, fuelled by the recognition of the need to protect American interests abroad. Politically, the war contributed to McKinley's re-election in 1900, although his second term was tragically cut short by his assassination in 1901. The legacy of the Spanish-American War and McKinley's presidency remains palpable. The issues raised by the conflict, particularly those relating to human rights, imperialist domination and the global role of the United States, continue to resonate in American foreign policy. Debates about the ethics and implications of imperialism, intensified by the war, marked the beginning of a century of confrontation and dialogue about the United States' position in the world. | |||

Before the Spanish-American War, Cuba's economy was strongly linked to that of the United States because of its crucial role in the sugar industry. American planters and investors had acquired vast tracts of land to grow sugar cane, capitalising on the intensive use of Afro-Cuban labour. This workforce was initially made up of slaves and, after the abolition of slavery, indentured labourers, often in conditions little better than slavery. The sugar trade not only enriched these investors, but also created mutual economic dependence between the two countries. For the United States, Cuba represented a reliable and profitable source of sugar, a product that was essential to the American economy at the time. This economic dependence shaped US-Cuban relations and had significant political implications. When the Spanish-American War broke out, the United States' deep-rooted economic interest in Cuba was a major factor underpinning the US military commitment. Although the motivations for the war were manifold, including humanitarian concerns and a desire to assert American power on a global scale, the protection of American economic interests was undeniably a key consideration. The US victory and the subsequent end of Spanish rule over Cuba marked the beginning of a new era for the island. Although Cuba won its independence, the US continued to exert considerable influence, encapsulated in documents such as the Platt Amendment, which granted the US the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and established the Guantanamo naval base, which the US maintains to this day. The wealth generated by the sugar industry and American investment continued to shape Cuban politics, economy and society well into the twentieth century. This dominant and sometimes controversial influence of the United States has helped shape the complex and tumultuous history of relations between the two countries, from the effects of the Spanish-American War to the embargo and beyond. | |||

The Spanish-American War, which broke out in 1898, was a concise but significant military conflict that took place in places as far apart as Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. The war arose from the tension resulting from the mysterious deaths of American sailors aboard the USS Maine, whose sinking in Havana harbour was attributed to Spain, although conclusive evidence was lacking. The main issue for the United States was Cuba. American military forces, benefiting from tactical and logistical superiority, quickly overcame Spanish resistance on the island. The war was characterised by fierce but brief battles, and Spain, faced with imminent defeat, agreed to a ceasefire. The impact of the war was not limited to a swift military victory. The peace agreements that followed significantly altered the geopolitical map. Spain, once a major colonial power, ceded control of key territories to the United States. Cuba, although technically independent, came under US influence, and Guam and Puerto Rico became US territories. The Philippines, a strategic archipelago, was sold to the United States for 20 million dollars. This conflict marked a profound transformation in American foreign policy. Before the war, the United States was widely perceived as a power in the making, concerned mainly with domestic and continental affairs. However, the stunning victory over Spain propelled the United States onto the world stage. The country became a colonial and imperialist power, its interests and influence extending far beyond its traditional borders. The repercussions of the Spanish-American War were felt for decades. It laid the foundations for American military and political engagement on a global scale and ushered in an era in which US power and influence would be a determining factor in world affairs. The victory not only redefined the international perception of the United States, but also sparked a lively national debate about the country's role in the world, a debate that continues to resonate in contemporary American foreign policy. | |||

The Haitian Revolution had a profound impact not only in the Caribbean, but throughout the Atlantic world, instilling fear among the slave-holding powers and inspiring movements for independence and the abolition of slavery. The success of the slave revolt in Haiti, which transformed France's richest colony into an independent republic governed by former slaves, was an alarming sight for the colonial powers that depended on slavery. In Cuba and Puerto Rico, the last Spanish colonial strongholds in America, the Creole elite watched the situation in Haiti with considerable trepidation. Much of their wealth and power was rooted in the agricultural plantations, and they relied heavily on slave labour. The possibility of a revolt similar to that in Haiti was an existential threat not only to their economic status, but also to their physical and social security. So, while aware of the shifting winds of freedom and independence blowing across Latin America, the elites of Cuba and Puerto Rico were also faced with a dilemma. Could a war for independence be contained and directed in such a way as to preserve their social and economic status, or would such a war unleash a social revolution that would overthrow them as well as the Spanish colonial yoke? It was against this backdrop that Spain, weakened and diminished by the loss of most of its American colonies, attempted to maintain its hold on Cuba and Puerto Rico. The severe repression of independence and reform movements, the restriction of civil and political rights, and the persistence of slavery (until its belated abolition) were all symptoms of the profound insecurity of Spain and the colonial elite in the face of the tumultuous waves of social and political change. | |||

Sugar production, fuelled by slave labour, was the mainstay of the Cuban economy, and the island was a major player on the world sugar market. The Creole elite, who benefited greatly from this economy, were reluctant to accept any disruption that might jeopardise their status and wealth. The Spanish-American War marked a radical change for Cuba. US intervention was motivated by a mixture of sympathy for the Cubans fighting for independence, strategic and economic concerns, and the influence of yellow journalism, which fanned the flames of interventionism among the American population. The American victory led to the 1898 Treaty of Paris, which put an end to Spanish sovereignty over Cuba. However, Cuba's independence was in reality limited. Although the island was technically independent, the Platt Amendment, incorporated into the Cuban constitution, gave the US the right to intervene in Cuban affairs to "preserve Cuban independence" and maintain "adequate government". In addition, Guantánamo Bay was ceded to the United States as a naval base, a presence that continues today. The impact of the Spanish-American War on Cuba was profound and long-lasting. It established a pattern of American influence and intervention on the island that persisted until the Cuban revolution of 1959 and beyond. American economic interests, particularly in the sugar sector, continued to play a significant role in the Cuban economy in the twentieth century, and relations between the two countries were marked by political, economic and military tensions that in many ways continue to this day. | |||

This war was a massive revolt against Spanish rule, marked by intense fighting and substantial destruction. Afro-Cubans, many of whom were former slaves or descendants of slaves, played a central role in this struggle, not only as fighters but also as leaders. The Pact of Zanjón, which ended the war, was a disappointment for many Cubans who aspired to complete independence. Although it put an end to slavery and granted certain political rights, Spain maintained its control over Cuba. Afro-Cubans were particularly disappointed, as although slavery had been abolished, equality and full integration into Cuban society were still a long way off. However, the Ten Years' War set a precedent for resistance to Spanish rule and helped shape the Cuban national identity. The resulting tensions and unfulfilled desire for independence helped trigger the Cuban War of Independence in 1895, which eventually led to American intervention and the Spanish-American War of 1898. These conflicts, along with unresolved issues of race, citizenship and equality, continued to influence Cuban politics and society until the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and beyond. The complexity of race relations, the struggle for equality and independence, and the influence of foreign powers are themes that persist in contemporary Cuban history and politics. | |||

The Cuban War of Independence, which began in 1895, was a pivotal moment in Cuban history. Revolutionary leaders such as José Martí, a poet, essayist and journalist, and Antonio Maceo, a high-ranking black general, were emblematic figures in this struggle. José Martí was a source of intellectual and moral inspiration for Cubans seeking independence. His dedication to the cause of freedom, his prolific writings on democracy and justice, and his opposition to American intervention in the island have become fundamental elements of Cuban national consciousness. The Cuban War of Independence was characterised by guerrilla tactics, fierce fighting and the exploitation of the Cuban mountains and countryside to resist Spanish domination. However, it was interrupted by the intervention of the United States, which became known as the Spanish-American War. The wreck of the USS Maine in Havana harbour in 1898 was the catalyst for the American intervention. Following the American victory, the 1898 Treaty of Paris ended the war and granted Cuba independence, although the island remained under considerable American influence and control for decades, as evidenced by the Platt Amendment which gave the US the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and establish a naval base at Guantánamo Bay. | |||

The situation in Cuba was attracting international attention, and in the United States the public, the media and politicians were keeping a close eye on developments. Tales of Spanish cruelty to the Cubans, amplified by the tabloid press, inflamed American public opinion and put pressure on the government to intervene. President William McKinley, initially reluctant to commit the United States to a foreign conflict, was forced to change course under pressure from public opinion and some of his advisers. The immediate trigger was the mysterious sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbour on 15 February 1898. Although the actual cause of the sinking remains debated, the American press was quick to blame Spain, further exacerbating tensions. On 25 April 1898, the United States declared war on Spain, marking the start of the Spanish-American War. American forces quickly demonstrated their superiority, winning victories in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris signed on 10 December 1898. Spain ceded Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines to the United States and relinquished its sovereignty over Cuba. Cuba became a de facto US protectorate, its nominal independence limited by the Platt Amendment, which granted the US the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and established the Guantánamo Bay naval base. So, although Cuba had been liberated from Spanish rule, its full independence was hampered by strong American influence. This situation lasted until the Cuban revolution of 1959, which established a socialist regime under the leadership of Fidel Castro and considerably reduced American influence on the island. | |||

It was against this backdrop that the yellow press, led by figures such as William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, played a leading role. The war was intense, and newspapers competed fiercely to increase their readership. They published exaggerated and sometimes fabricated accounts of Spanish cruelty to the Cubans to attract and hold the public's attention. The famous words attributed to Hearst, "You provide the pictures, I'll provide the war", although possibly apocryphal, embody the spirit of the press's role in creating a climate conducive to war. Public pressure on President McKinley intensified, exacerbated by the mysterious destruction of the USS Maine in Havana harbour. Although there was no conclusive evidence linking Spain to this tragedy, the press and public opinion were ready to accuse them. Faced with intense popular and political pressure, McKinley relented and asked Congress for authorisation to intervene militarily in Cuba. The Spanish-American War, sometimes called "the splendid little war" by the Americans, was brief. The American victory marked the country as a rising world power and extended its influence overseas. Cuba, freed from Spanish rule, fell under American influence. The Platt Amendment of 1901, incorporated into the Cuban constitution, allowed the United States to intervene in Cuban affairs and to lease or buy land for naval bases and coal, giving rise to the Guantánamo Bay naval base. This war, and the climate that preceded it, testify to the power of the media and public opinion in the formulation of foreign policy. It also illustrates the economic and strategic interest that drives military intervention, a reality that continues to inform the examination of contemporary conflicts.<gallery mode="packed" widths="200" heights="200"> | |||

Fichier:Wreck of the U.S.S. Maine, ca. 1898 - NARA - 512929.jpg| | Fichier:Wreck of the U.S.S. Maine, ca. 1898 - NARA - 512929.jpg|Wreck of the USS Maine in Havana harbour. | ||

Fichier:World98.jpg| | Fichier:World98.jpg|Cover of the New York World, 17 February 1898. | ||

Fichier:Platt amendment page 1.jpg|Page | Fichier:Platt amendment page 1.jpg|Page one of the Platt Amendment. | ||

Fichier:Platt amendment page 2.jpg|Page | Fichier:Platt amendment page 2.jpg|Page two. | ||

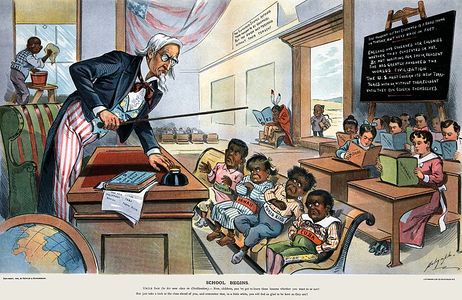

Fichier:School Begins (Puck Magazine 1-25-1899, cropped).jpg|Caricature showing Uncle Sam lecturing four children labelled Philippines, Hawaii, Porto Rico and Cuba in front of children holding books labelled with various U.S. states. The caption reads: "School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you’ve got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!". | Fichier:School Begins (Puck Magazine 1-25-1899, cropped).jpg|Caricature showing Uncle Sam lecturing four children labelled Philippines, Hawaii, Porto Rico and Cuba in front of children holding books labelled with various U.S. states. The caption reads: "School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you’ve got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!". | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Version du 7 novembre 2023 à 12:34

Based on a lecture by Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

The Americas on the eve of independence ● The independence of the United States ● The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society ● The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas ● The independence of Latin American nations ● Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies ● The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery ● The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877 ● The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900 ● Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910 ● The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940 ● American society in the 1920s ● The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940 ● From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy ● Coups d'état and Latin American populisms ● The United States and World War II ● Latin America during the Second World War ● US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty ● The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution ● The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

In the wake of the Spanish-American War of 1898, which saw the United States seize territories such as Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines, a new era of American imperial power was ushered in. This historic conflict, marked by significant territorial expansion, signalled the rise of the United States on the world stage.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the American presence was strongly felt in the Western Hemisphere. With growing wealth and military power, the United States adopted an interventionist policy, often justified by the need to protect American economic interests and preserve regional stability. Nations such as Mexico, Honduras and Nicaragua were theatres of US intervention, creating a power dynamic that reflected President Theodore Roosevelt's "Big Stick" doctrine.

However, the political and social landscape of the United States began to change in the 1920s. Faced with domestic economic and social challenges, a wave of isolationism swept the nation. Earlier interventionism had engendered widespread hostility and resentment throughout Latin America, and the American public voice was calling for a retreat and a reassessment of international commitments.

It was against this backdrop that the 'Good Neighbour' policy was born under President Herbert Hoover, and developed significantly under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Abandoning the interventionist approach, this new directive emphasised the importance of respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of neighbouring nations. The United States embarked on an era of diplomacy and cooperation, marking a radical departure from the aggression and interventionism that had characterised previous decades.

History of bick stick and good neighbour policies

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the territorial expansion of the United States was driven by a variety of factors, resulting in a period of rapid transformation and significant growth. This westward and southward expansion reflected not only economic growth but also the tangible realisation of the ideology of "Manifest Destiny". The insatiable economic need for fertile farmland, new trade routes and unexplored natural resources was a key driver of expansion. At the height of the Industrial Revolution, access to new resources and markets was imperative to sustain the nation's meteoric economic growth and prosperity. The exploration and annexation of new territories were not only economic imperatives, but also proof of the young nation's vigour and daring. At the same time, the political ambitions of America's leaders and the aspiration to achieve greater national and international stature played a central role in this expansion. Each new territory acquired helped to strengthen the United States' presence on the world stage, testifying to its growing power and influence. Ideologically, the notion of American exceptionalism and the belief in a "manifest destiny" strongly influenced this era of expansion. The belief that the United States had been chosen by Providence to extend its influence, democracy and civilisation across the continent animated the nation. This impetus was also reinforced by the pioneering spirit of the citizens, drawn by the promise of new opportunities, the prospect of land ownership and the adventure inherent in conquering the frontier. However, this rapid expansion was not without conflict and controversy. The conquest of the West and expansion southwards involved massive displacements of native populations and exacerbated tensions around the issue of slavery, ultimately culminating in the American Civil War. The Trail of Tears and other injustices suffered by indigenous peoples mark a dark chapter in this historical period.

War was a key instrument of the United States' territorial expansion in the 19th century, with the Mexican-American War a striking illustration of this phenomenon. This military confrontation, largely motivated by territorial claims and expansionist aspirations, reshaped the map of North America. Launched in 1846, the war was preceded by the annexation of Texas by the United States, an act that raised tensions with Mexico over border disputes. The disputed area, rich and strategically valuable, became the focus of American and Mexican ambitions. Attempts at negotiation proved fruitless, leading inevitably to armed conflict. This conflict was marked by a series of battles that saw US forces systematically advance through Mexican territory. The United States' military superiority and effective strategies led to decisive victories. In 1848, the war came to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, an agreement that not only sealed the American victory but also facilitated considerable territorial expansion. Through this treaty, Mexico ceded a vast territory to the United States, including modern states such as California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. This acquisition considerably expanded the American frontier, paving the way for a new wave of colonisation and exploration. The Mexican-American War thus reflects the complexity and intensity of the United States' expansion efforts. It demonstrates how territorial ambitions, exacerbated by ideologies such as Manifest Destiny and American Exceptionalism, led to significant territorial conflicts and realignments. This chapter in American history continues to influence bilateral relations and regional dynamics in contemporary North America.

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 represents a significant milestone in the expansionist trajectory of the United States, underlining the national strategy of acquiring territory not only through conflict, but also through diplomacy and trade. This historic event illustrates the complexity and multi-faceted nature of the methods used to extend the nation's borders. In the international context of the time, France, under the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, was facing considerable financial and military challenges. At the other end of the Atlantic, the United States, a young and rapidly growing nation, was eager to expand and secure access to the Mississippi River to promote trade and westward expansion. The Louisiana Purchase, negotiated by President Thomas Jefferson, was a $15 million deal that doubled the size of the United States overnight. Not only was it a diplomatic triumph, it also opened up vast tracts of land for exploration, colonisation and economic development. States such as Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma and others were carved out of this acquisition, radically transforming the political and geographical landscape of the United States. This decisive moment in American history demonstrates the power of diplomatic negotiations and commercial transactions in the realisation of a nation's territorial ambitions. It also embodies the opportunities and challenges associated with the rapid integration of new territories and diverse populations. Today, the Louisiana Purchase is often cited as an early and impactful example of American expansion, illustrating an era when opportunities and aspirations were as vast as the newly acquired territory itself.

Colonisation and population migration were crucial instruments in the expansion of the United States, complementing wars and territorial acquisitions. The movement along the Oregon Trail is an eloquent example of how citizen migration contributed directly to the country's territorial expansion. In the 1840s and 1850s, driven by the promise of economic opportunity and the lure of vast tracts of fertile land, thousands of American settlers embarked on the arduous but promising journey along the Oregon Trail. This mass migration to the Pacific Northwest was not simply a demographic phenomenon; it also represented a concrete manifestation of the belief in "manifest destiny", the idea that Americans were destined to occupy and dominate the North American continent. This migration to Oregon and other western territories was not without its challenges. The pioneers faced difficult terrain, unpredictable weather conditions and the dangers inherent in frontier life. Nevertheless, the desire for a better life and the prospect of economic prosperity fuelled the settlers' determination and commitment to western expansion. The increased presence of American settlers in the Pacific Northwest over time facilitated the annexation of these territories by the United States. This was not simply a political or military act, but a gradual integration facilitated by colonisation and the establishment of communities.

The Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny were the cornerstones of American foreign policy and territorial expansion in the 19th century. They embody the aspirations, convictions and strategies that guided the transformation of the United States into a powerful and expansive nation. The Monroe Doctrine, announced in 1823 by President James Monroe, was rooted in the goal of preserving the independence of newly independent nations in Latin America from any European attempts at recolonisation or intervention. It declared that any attempt by European powers to intervene in the Western Hemisphere would be considered an act of aggression requiring an American response. Although motivated by the desire to protect the nations of Latin America, it also symbolised the assertion of American influence and authority in the Western Hemisphere. Manifest Destiny, on the other hand, was an ideological conviction rather than an official policy. Emerging around the 1840s, it held that the United States was destined by Divine Providence to expand from sea to sea, spreading freedom, democracy and civilisation. This belief fuelled the enthusiasm and moral justification for westward expansion, leading to the colonisation of territories, conflicts with indigenous populations and wars to acquire new territories. Together, these doctrines shaped an era of vigorous expansion. The Monroe Doctrine laid the foundations for a foreign policy focused on regional hegemony, while Manifest Destiny provided the ideological fuel for domestic expansion and the transformation of the national landscape. The effects of these doctrines resonate to this day. They not only shaped the territorial contours of the United States, but also influenced the national psyche, instilling a belief in American exceptionalism and the country's special role in the world. They continue to be references for understanding the dynamics of American policy, both domestic and foreign, and the historical development of the nation.

The Monroe Doctrine was a pivotal element in the formulation of nineteenth-century American foreign policy. President James Monroe articulated it in response to the international environment of the time, characterised by the dynamism of independence movements in Latin America and the ambitions of European powers. The precise articulation of this doctrine coincided with a time when Latin America was in turmoil, shaken by movements to free itself from the yoke of European colonialism. The United States, aware of its position and strategic interests, issued this doctrine not only to support the newly independent nations but also to assert its sphere of influence on the continent. At the heart of the Monroe Doctrine was the implicit idea of excluding the European powers from the Western Hemisphere. Any attempt at recolonisation or intervention would be interpreted not only as a threat to the independent nations of Latin America, but also as direct aggression against the United States. It was a bold statement, underlining the ascendancy of the United States as a regional power and its intention to shape the political and geopolitical order of the New World. The Monroe Doctrine was also facilitated by the distance between Europe and the Americas, and by the British commitment to European non-intervention, a shared interest that stemmed from British commercial ambitions in the region. The Royal Navy, the most powerful naval force at the time, was an unstated asset underpinning the doctrine. Over time, the Monroe Doctrine became a fundamental principle of American foreign policy, evolving and adapting to changing circumstances. It not only reaffirmed the United States' position as the dominant force in the Western Hemisphere, but also laid the foundations for future interventions and relations with the nations of Latin America and the Caribbean. Thus, although it was formulated in a specific context, its impact and resonance have spanned the ages, influencing interactions and policies well beyond the nineteenth century.

Manifest Destiny was an ideological driving force, framing and justifying the impetuous expansion of the United States across North America in the nineteenth century. It was a belief rooted in the idea that the nation was chosen, with a divine mission to expand its borders, disseminate its democratic values and shape the continent in its image. The way in which Manifest Destiny influenced the specific policies and actions of the United States is illustrated by key events of the period. The annexation of Texas, for example, was partly justified by this belief in an exceptional mission. After gaining independence from Mexico in 1836, Texas became an independent republic. However, joining the United States was a hotly debated issue, and the Manifest Destiny provided moral and ideological justification for annexation in 1845. The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) is another example where Manifest Destiny was invoked. The United States, convinced of its divine right to expansion, saw the conflict as an opportunity to extend its territories to the west. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war, not only confirmed the annexation of Texas but also ceded significant territories from Mexico to the United States, including California and New Mexico. The colonisation of the American West was also inspired by this ideology. The pioneers who braved harsh conditions to venture into uncharted territory were often motivated by the belief that they were part of a greater mission, carving civilisation out of a savage landscape and fulfilling the nation's manifest destiny.

The Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny worked in complementary ways to sculpt the trajectory of the American nation, shaping not only its physical borders but also its identity and role on the world stage. The Monroe Doctrine acted as a bulwark, a defensive statement against European encroachment, asserting American sovereignty and influence in the Western Hemisphere. It was an assertion of power and control, establishing a doctrine of non-interference which, although initially limited in its effective application, laid the foundations for a more robust assertion of regional hegemony. The United States thus positioned itself not only as the guardian of its own security and sovereignty, but also as the implicit protector of the nations of Latin America against European colonialism. Manifest Destiny, on the other hand, was more expansionist and proactive in essence. It was not content to defend existing borders, but sought to extend them, driven by an almost mystical belief in the providential order. It injected a moral and ideological impetus into expansion efforts, transforming conquest and colonisation into an almost spiritual imperative. Each new territory conquered, each frontier pushed back, was seen not only as a material gain but also as a fulfilment of the nation's divine destiny. In synergy, these doctrines forged a political and ideological landscape that defined 19th-century America and sowed the seeds of its power and influence in the 20th century and beyond. They fuelled wars, acquisitions and policies that extended American borders from the Atlantic to the Pacific and elevated the United States to the status of undisputed world power. In their wake, they have left a legacy of complex and sometimes controversial issues, ranging from justice and the rights of indigenous peoples to the management of power and influence on a global scale. Each in its own way, the Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny illustrate the dynamic tension between protection and expansion, between defending what has been achieved and aspiring to more, that has continued to animate US foreign and domestic policy through the ages. They embody the blend of pragmatism and idealism, realism and romanticism, that has so often characterised American history and identity.

Through a combination of military, diplomatic and popular means, the United States has succeeded in shaping a territory that stretches from sea to sea, laying the foundations of a continental power. The Mexican-American War was a key event in this process. As a military conflict, it led to the substantial acquisition of territory to the south and west, bringing rich and diverse regions into the union. Every battle won and every treaty signed was not simply a military victory, but a step closer to realising a vision of an expanded and unified America. The Louisiana Purchase, although a peaceful transaction, was also tinged with geopolitical and military implications. The extension of territories beyond the Mississippi not only doubled the size of the country, but also positioned the United States as a force to be reckoned with, capable of bold negotiations and strategic expansion. The settlement of the American West, while less formal and structured than wars and diplomatic agreements, was perhaps the most organic and indomitable. It was fuelled by the will of individuals, the energy of families and communities seeking a better life, and a land where they could exercise their right to freedom and property. The 'westward rush' was both a physical migration and a spiritual quest, a movement into uncharted territory and a plunge into the unknown of American possibilities. The purchase of Alaska in 1867, although geographically disconnected from the American continent, was symbolic of the same expansionist impulse. It was a testament to the United States' ability to look beyond its immediate borders, to envisage a presence and influence that were not limited to its traditional frontiers.

Each treaty and agreement was crucial in delimiting the borders and defining the relationship between these two North American nations.

The Treaty of Paris (1783) was a major milestone, not only because it marked the end of the American War of Independence, but also because it defined the first territorial boundaries of the United States. It confirmed American independence and established the northern boundary along the Great Lakes, although ambiguities and uncertainties persisted, leading to ongoing tensions. The War of 1812, although less well known, was also significant. It reflected unresolved tensions and conflicting territorial claims. The Treaty of Ghent, which concluded this war, restored the status quo ante bellum, or "the state in which things were before the war". However, the war itself and the treaty that concluded it helped to shape the character and tone of future US-Canadian relations. The agreement of 1818 was another crucial development. The delineation of the 49th parallel as the boundary was an early example of the peaceful resolution of conflicting land claims. It not only demonstrated diplomatic maturity but also set a precedent for the management of future disputes. These agreements and treaties laid the foundations for a relatively peaceful and cooperative relationship between the United States and Canada, and shaped a border that is now often cited as one of the longest undefended borders in the world. By defining the geographical and political parameters of this relationship, they also laid the foundations for the economic, cultural and political dynamics that characterised bilateral interactions in the years that followed. Each agreement was a step towards clarifying, stabilising and pacifying US-Canadian relations. Together, they helped to create a tapestry of cooperation and mutual respect, which, though repeatedly tested, has largely weathered the storms of international politics and continues to define the bilateral relationship to this day.

The territorial growth of the United States, particularly in a northerly direction, was largely stabilised by the mid-nineteenth century. The agreement with Great Britain in 1818, not 1812, which established the 49th parallel as the boundary, was a defining moment in the consolidation of the northern borders of the United States. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 also played an important role. It extended the boundary from the 49th parallel to the Pacific coast, resolving the competing territorial claims between Great Britain and the United States in the Oregon Country region. This treaty, complementing earlier arrangements, helped to define the modern form of the boundary between the United States and Canada. The acquisition of Alaska in 1867 was a notable exception to the stabilisation of American borders. The purchase of this vast territory from Russia added a significant dimension to the United States, not only in terms of territory, but also in terms of natural resource wealth and strategic position.

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, an agreement that not only pacified relations between the two countries but also resulted in a significant transfer of territory from Mexico to the United States. This territorial acquisition, often referred to as the "Mexican Cession", marked a decisive step in American westward expansion. These new territories were characterised by their geographical, climatic and cultural diversity. The arid desert, majestic mountains, fertile valleys and picturesque coastline offered a range of opportunities and challenges for the new occupants. California, in particular, quickly became a major site of interest, not least because of the discovery of gold in 1848, which triggered the famous gold rush and attracted thousands of people in search of fortune and opportunity. The US government was faced with the challenge of integrating these vast and diverse territories. Issues of governance, property rights, relations with indigenous populations and residents of Mexican origin, and infrastructure were all pressing. The cultural and linguistic diversity of the region, enriched by the presence of communities of Mexican origin, added another layer of complexity to integration. The opportunities for expansion and colonisation were immense. Access to the Pacific coast opened up markets and business opportunities in Asia and the Pacific. The region's mineral wealth promised economic prosperity. Arable land offered opportunities for agriculture and rural development. At the same time, the government also had to navigate the challenges posed by ethnic and cultural diversity, the rights of indigenous peoples and environmental issues. The successful integration of these territories into the Union represented a major transformation of the United States, reinforcing its status as a continental power and ushering in an era of unprecedented growth and development that would shape the country for generations to come. Managing this expansion and the diversity inherent in these new territories is an essential chapter in American history, reflecting the tensions, compromises and innovations that characterised the nation in formation.

The question of slavery was a central issue that permeated every aspect of political, social and economic life in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. Each new territory acquired, each state admitted to the Union, brought this sensitive issue back to the centre of the national debate. The Mexican-American War and the resulting territories exacerbated these tensions. The slave-holding South and the abolitionist North had diametrically opposed visions of the direction the nation should take. The economic prosperity of the South was deeply rooted in the slave system, while the industrialising North took a different moral and economic view. The Compromise of 1850 was a delicate attempt to navigate these conflicting realities. By incorporating California as a free state, it granted a significant victory to abolitionist forces. However, by allowing popular sovereignty in the territories of New Mexico and Utah, it left the door open to the possibility of slavery in those regions, thereby allaying, at least temporarily, Southern fears of being marginalised and overtaken in national political power. One of the most controversial elements of the compromise was the Fugitive Slave Act, which required escaped slaves to be returned to their owners, even if they had fled to states where slavery was illegal. This exacerbated tensions between North and South and highlighted the moral and ethical divide that divided the nation. This compromise, though temporary and imperfect, reflects the intrinsic tensions and painful compromises that characterised the period leading up to the American Civil War. It was a time when the nation struggled to reconcile incompatible values, economies and worldviews, an effort that would ultimately fail, plunging the country into the most devastating conflict in its history to that point.

The Compromise of 1850 was a temporary and fragile solution to a deep and persistent crisis. Although it temporarily eased tensions, it did not solve the underlying problems that were eating away at the nation. The foundations of the Civil War were rooted in deep and irreconcilable disagreements over slavery and its implications for the nation's economy, society and politics. The delicate balance between slaveholding and abolitionist states was constantly tested by westward expansion. Each new territory acquired and each new state added to the Union forced a renegotiation of this precarious balance. Popular sovereignty, a principle introduced in the Compromise of 1850, which allowed residents of the new territories to decide by vote whether they would allow slavery, was an attempt to decentralise this burning issue. However, it often exacerbated tensions by making each new territory a battleground for the future of slavery in the United States. The decade leading up to the Civil War was marked by escalating tensions. Incidents such as the bloody confrontation in Kansas, often referred to as "Bleeding Kansas", highlighted the violence and division that flowed directly from the issue of slavery. The Supreme Court's decision in the Dred Scott case in 1857, which declared that blacks were not citizens and that Congress could not prohibit slavery in the territories, further inflamed passions. The Civil War was the inevitable conclusion of years of unsatisfactory compromises, unresolved tensions and growing divisions. It was the product of a nation deeply divided not only over the issue of slavery, but also over questions of state versus federal power, agrarian versus industrial economy, and two fundamentally irreconcilable visions of the world and of American identity. This conflict, while devastating, also paved the way for the end of slavery and the radical transformation of the American nation, ushering in an era of reconstruction and reinvention that would continue to shape the United States for generations to come.

Private attempts at annexation and expansion through counter-territories

Private attempts at expansion and annexation

Attempts at private expansion and annexation were common and were often the result of the ambitions of individuals and companies keen to capitalise on the economic opportunities offered by foreign territories. This dynamic was particularly evident in Central America and the Caribbean. Individuals such as William Walker exemplify this phenomenon. Walker, an American adventurer and mercenary, invaded and briefly took control of Nicaragua in the 1850s, with the intention of creating an English-speaking, slave-owning colony, an act directly linked to the wider issue of slavery and territorial expansion in the United States. Similarly, many companies, especially in the railway, mining and agricultural sectors, saw overseas expansion as a way of increasing their profits. The lure of abundant raw materials, untapped markets and opportunities to create new trade routes were important drivers for expansion. It should also be noted that these efforts were not isolated from government policies. Often, private and government interests were closely aligned. The US government might support, directly or indirectly, corporate expansion efforts in the hope that their success would strengthen the US economy and extend American influence abroad. Conversely, private companies could count on diplomatic, military and logistical support from the government to facilitate their expansion efforts. This complex interrelationship between private and public, economic and political interests has been a defining feature of American expansion. It underlines the diversity of factors and actors that have helped shape the trajectory of US growth and influence beyond its original borders.

Walker was a "filibuster", a term used to describe those who engaged in unauthorised military action in foreign countries with which the United States was officially at peace. In 1856, Walker succeeded in taking control of Nicaragua, a country strategically located for trade and shipping between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. He proclaimed himself president and tried to establish English as the official language, as well as introducing laws favouring Americans and their businesses. He also legalised slavery, hoping to win the support of the American slave states. However, his actions provoked a united regional reaction in Central America. Countries like Costa Rica, Honduras and others joined forces to expel Walker and his mercenaries. Moreover, although some sectors of the United States, particularly in the South, initially supported Walker in the hope that his successes might strengthen the slave cause, the US government as a whole was reluctant to openly support his actions because of the diplomatic and legal implications. Walker's failure underlines the complexities and challenges associated with private attempts at expansion. Although ambitious and bold, these efforts were often fragile, dependent on the domestic and international political context. Walker's story also highlights how issues of slavery and territorial expansion were closely intertwined in the run-up to the Civil War, and how personal ambitions, economic interests and political issues could converge and collide in the dynamic and often tumultuous context of nineteenth-century American expansion.

Private attempts at annexation, such as those led by groups of adventurers in Cuba and William Walker in Nicaragua, were fuelled by a combination of ambition and ideology. These individuals and groups were often motivated by the prospect of considerable economic gain. The territories of Central America and the Caribbean were seen as lands rich in natural resources, offering new market opportunities and strategic trade routes. For entrepreneurs and investors, the conquest and annexation of these regions represented an opportunity to increase their wealth and influence. At the same time, American exceptionalism and the belief in Manifest Destiny were powerful driving forces behind these expansionist ventures. The notion that the United States was exceptional and destined for a special role in world history was deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness. For many Americans at the time, extending American influence meant spreading values, a political system and a civilisation considered superior, and this expansion was often seen as morally justified. Politically, each new attempt at expansion was seen as a means of asserting and strengthening the United States' position on the international stage. The addition of new territories or the extension of American political and economic influence was seen as a step forward in the country's assertion as a rising international power. However, it is important to stress that these annexation attempts were controversial and often a source of conflict. The interventions were seen by many, both in the United States and abroad, as illegal or immoral. The complexity was exacerbated by the ever-present issue of slavery. Every potential new territory was a stake in the heated national debate over the issue. Regions targeted for annexation were often caught up in the tumult of debates over slavery, making every attempt at expansion a reflection of the internal tensions that defined the era.

The precarious balance between slave-holding and abolitionist states was a central feature of nineteenth-century American politics. Every new state or territory acquired raised the contentious issue of slavery, and initiatives such as attempts to privately annex territories like Cuba and Nicaragua were inextricably linked to this dynamic. Cuba and Nicaragua, rich in resources and strategically located, were attractive targets for expansion. However, their annexation would likely have resulted in their incorporation as slave states, due to their existing economic and social systems, and pressure from American slave interests. This prospect fuelled fears of a growing imbalance in favour of the slave states, with profound implications for national political power, social policy, and the wider question of national identity. In this context, figures like William Walker met with significant resistance. Although some factions in the United States supported expansionist ambitions, opposition was strong. Abolitionists, political leaders concerned about the balance of power, and those who feared the international implications of unsanctioned annexations, united to thwart these efforts. Diplomacy, legislation and, in some cases, military force were mobilised to counter attempts at expansion that risked exacerbating national divisions.

The international dimension of opposition to private annexation attempts was a key factor. The local populations and governments of the countries targeted by these expansion attempts resisted vigorously, rightly perceiving these actions as direct attacks on their sovereignty, autonomy and territorial integrity. The aspirations of American adventurers and entrepreneurs were often pitted against the determination of the target nations to preserve their independence. The complexity of the forces involved - which included not only American interests and local governments, but often other colonial and regional powers - made the situation extremely volatile. Local resistance was often fervent and determined, underpinned by a deep sense of nationalism and a desire to protect their territory and resources. The case of Nicaragua with William Walker is particularly illustrative. Walker and his men met with fierce resistance not only from the Nicaraguans, but also from neighbouring nations. Central America, well aware of the implications of foreign domination, united to repel the invasion. Resistance was fuelled by a combination of defending national sovereignty, ideological opposition and protecting regional economic and political interests. Thus, private attempts at annexation were far from unilateral affairs. They were the scene of complex, multidimensional conflicts involving a variety of players with divergent interests. They underline the entanglement of personal ambitions, national and international interests, and ideological and economic issues that characterised the era of American expansion in the nineteenth century.

William Walker's actions embody the complexity and ambiguity of nineteenth-century American expansion. Although some parts of American society were in favour of expansion, including through unconventional or unofficial means, the majority of citizens and government officials disapproved of actions such as those of Walker. Walker became a symbol of a form of unregulated and unsanctioned adventurism. His actions in Nicaragua were interpreted by many as an embodiment of haphazard and unauthorised expansionism. This created significant tension, not only within the United States but also in international relations, calling into question the coherence and legitimacy of US commitments in the region. The contrast between Walker's actions and the Monroe Doctrine is particularly striking. Whereas the Monroe Doctrine was a unilateral declaration of opposition to further European colonisation or interference in the Americas, Walker's actions appeared to violate the spirit of this policy. Although his aim was to extend American influence, his methods and motives were seen by many as incompatible with the principles of respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity that underpinned the Monroe Doctrine. Walker thus became a controversial figure, illustrating the limits and contradictions of American foreign policy at the time. His career highlights the conflicts between often noble ideals and the practical and moral realities of expansion, and raises enduring questions about the ethics, legality and consequences of American expansion in the nineteenth century. Its history remains a reminder of the tension between national ambition and ethical principles, an issue that has continued to resonate in subsequent decades.

The notion of American exceptionalism played a central role in justifying American expansionism, but it also raised major ethical and practical issues. This belief, rooted in the idea that the United States was unique and had a divine mission to spread its political, economic and cultural system, was a driving force behind territorial expansion and imperialism. However, this same belief has often led to a condescending, even imperialist attitude towards other nations and cultures. The belief in the superiority of American methods and values has sometimes led to contempt for the cultures, political systems and peoples of the territories the United States sought to acquire or influence. This attitude has not only been ethically and morally criticised, but has also generated considerable resistance to American expansion and influence. In many territories and countries targeted for American expansion or influence, local populations fiercely resisted what they perceived as foreign imposition and disregard for their sovereignty and culture. Resistance was fuelled by a sense of alienation and opposition to the imperialist attitude. American exceptionalism was therefore both a driving force for expansion and a source of tension and conflict.

The William Walker episode in Central America embodies a tumultuous chapter in the history of American expansionism. Despite the failure of his ambitions, the impact of his actions resonated far beyond his time, leaving an indelible mark on the historical and political memory of the region. Walker, armed with audacity and an unshakeable confidence in the manifest destiny of the United States, embodied the extreme manifestation of American expansionism. His attempts to establish puppet regimes and extend American influence through unofficial and often violent means highlighted the tensions inherent in the intersection of ambition, morality and international politics. In Central America, Walker's incursion was not simply an isolated event, but a symbol of imperialist intrusion, a metonymy for the wider expansionist aspirations of the United States and other powers. His controversial legacy lies in the scars left by his campaigns, scars that have fuelled a deep sense of mistrust and resistance to foreign interference in the region. Walker's actions have also fuelled debate in the US about the limits and implications of expansion. While one faction celebrated his daring as a living example of manifest destiny, others vilified him as a mercenary, a symbol of the excesses and moral dangers of unchecked imperialism. Ultimately, William Walker's adventure is a rich and complex tale of ambition, power and resistance. It is part of the larger picture of American expansionism, illuminating the tensions between the aspiration to national greatness and the ethical and practical challenges that such an aspiration imposes. It is a story of the often conflicting encounter between ideals and realities, a chapter in American and Central American history that continues to resonate in contemporary dialogues about the power, principles and place of nations on the world stage.

The execution of William Walker marked a sombre and controversial conclusion to a saga that has highlighted the moral, legal and political dilemmas of American expansionism. The consequences of his actions were not limited to himself; his supporters also suffered the fallout of his bold but unsanctioned attempts at annexation. Many shared his tragic fate or were forced into exile, becoming pariahs marked by failure and controversy. In America, the reaction to Walker's downfall was mixed but largely critical. His actions, once supported by segments of society who saw in his ambitions an echo of manifest destiny, were re-evaluated through the prism of political and moral realism. The nation, confronted with the international repercussions and ethics of his attempts at expansion, distanced itself from Walker. He became synonymous with misguided adventurism, an embodiment of the excesses and dangers of unregulated expansion. The Monroe Doctrine, a pillar of American foreign policy that reaffirmed the sovereignty and integrity of the nations of the New World, came to stand in stark contradiction to Walker's actions. He, an American, seeking to usurp the sovereignty of an independent nation, seemed to betray the very principles that the Monroe Doctrine sought to uphold. Walker thus became not only a pariah in the eyes of many contemporaries, but also a case study in the limits and contradictions of American expansionism. This chapter in history, marked by daring, failure and controversy, remains a reminder of the complexity of American expansionist ambitions in the nineteenth century. William Walker's actions, while marginal and unsanctioned, raised crucial questions about the nature of American expansion, the ethics of imperialism and the inherent tensions between national ideals and international realities - questions that continue to resonate in contemporary debates about American foreign policy.

William Walker's complex and ambivalent legacy in Central America is a source of lively debate and critical reflection. His actions in the region are characterised by a mixture of voluntarism, adventurism and imperialist ambitions, all imbued with the nuances of American exceptionalism and the geopolitical tensions of the nineteenth century. The local populations, faced with the intrusion of Walker and his forces, were not passive bystanders but active and resistant players. They opposed his attempts to dominate the region, a resistance rooted in the defence of their sovereignty, dignity and right to self-determination. Walker was, for many, the embodiment of foreign imperialism, a man whose personal and national ambitions threatened the integrity and independence of the Central American nations. However, Walker's legacy is nuanced and controversial. Some, with the benefit of hindsight, have sought to reassess his impact, highlighting the modernising ambitions and efforts to introduce reforms and structures which, although imposed, had the potential to bring positive change to a region beset by political, social and economic challenges. This perspective, though less widespread, highlights the complexity of judging historical actions through the prism of contemporary norms. The figure of William Walker, with his contradictions and ambivalences, serves as a window on the tensions of the nineteenth century in Central America and the United States. He is a figure who embodies the conflicts between imperialism and sovereignty, between American exceptionalism and the brutal realities of foreign domination, and between idealised visions of progress and the complex and often painful experiences of peoples affected by expansionism. Its history continues to provoke critical reflection on the lessons of the past and the implications for the future of international relations in the Americas.

The annexation of Hawaii

The annexation of Hawaii is a poignant example of the complex interplay of economic, political and social interests that characterised the era of American expansionism. The resource-rich Hawaiian Islands, strategically located in the Pacific, were an attractive target for American interests. Sugar growers, in particular, were attracted by the prospect of unfettered access to the US market, free from tariffs and trade constraints. However, the annexation of Hawaii was not a unilateral or uncontested process. It involved a mosaic of actors, each with their own aspirations, concerns and resistance. American planters and businessmen faced resistance from the Hawaiian monarchy, which was fighting to preserve the sovereignty and integrity of their kingdom. The locals, meanwhile, were caught up in a whirlwind of changes that threatened their way of life, their culture and their autonomy. American politicians, balancing economic and strategic imperatives with ethical and legal considerations, found themselves navigating a sea of conflicting interests. The debates over the annexation of Hawaii revealed fissures in American politics, exposing the tensions between imperialist aspirations and Republican principles, between economic interests and moral considerations. The final annexation of Hawaii in 1898 was the result of a convergence of factors, including the pressure of economic interests, the strategic imperatives of America's presence in the Pacific and internal American political dynamics. It marked the end of Hawaiian sovereignty and the incorporation of the islands into the American fold, an act that continues to resonate in contemporary debates about justice, redress and recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples.

The process of annexing Hawaii at the end of the nineteenth century was catalysed by an amalgam of economic and strategic interests that converged to make the islands a key issue in the projection of American power and influence in the Pacific. The economic dominance of American businessmen and planters in Hawaii was well established. Sugar, the white gold of the islands, had transformed Hawaii into a bastion of agricultural wealth, attracting significant investment and integrating the island economy deeply into the dynamics of the American market. Annexation offered a tantalising promise - the abolition of tariff barriers and unfettered access to the mainland market, boosting the prosperity of planters and protecting their economic hegemony from foreign incursion. Strategically, Hawaii was seen as a jewel of immeasurable importance. President Grover Cleveland, and those who shared his vision, recognised the islands' geostrategic importance. At the heart of the Pacific, Hawaii offered the United States an advanced platform for projecting naval power, a bastion that would secure crucial sea lanes and strengthen the American presence in an increasingly contested region. However, this convergence of economic and strategic interests was not uncontested. The Hawaiian monarchy, the natives and even some segments of American society were concerned about the implications of annexation. Questions of sovereignty, international law and the impact on Hawaiian culture and society were central to the heated debates surrounding the annexation process. Thus, Hawaii's incorporation into the Union was not simply a unilateral act of territorial acquisition, but rather a complex and multifactorial process. It was shaped by economic power dynamics, imperialist aspirations, strategic considerations and the forces of resistance that emerged to challenge and question the moral and legal implications of annexation. This chapter in American and Hawaiian history remains a fascinating study of the forces at play in the era of American expansionism and imperialism.

The annexation of Hawaii in 1898 marks a significant and controversial turning point in the history of relations between the United States and the Pacific Islands. The coup, orchestrated and executed with the implicit support of US interests on the island, overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy and paved the way for the incorporation of the islands into the American nation. The use of a joint resolution of Congress to annex Hawaii was unprecedented and sparked heated debate, not only on the legality of the act, but also on its ethical and moral implications. President McKinley, in signing the resolution, put his weight behind a decision that expanded the geographical and strategic reach of the United States but also raised profound questions about the balance between expansionism and fundamental democratic principles. For many Hawaiian nationalists, the annexation represented a brutal usurpation of their sovereignty, a dispossession of their land, culture and identity. They were forced into a union that had not been consented to, and the resilience of their opposition is still evident in contemporary movements for the recognition and restitution of the rights of indigenous peoples in Hawaii. Among Americans too, the annexation of Hawaii was not universally approved. A significant segment of public and political opinion perceived this action as an affront to republican and democratic ideals. There was concern that imperialism, by subjugating other peoples and extending governance beyond continental borders, would corrupt the fundamental values that defined American national identity.

The American Civil War marked an abrupt interruption in the process of American expansion, redirecting national attention to a deeply rooted internal conflict. It was not simply a military war, but a fight for the very soul of the nation, a bitter struggle to define the values, principles and identity of the new America. The industrial North and the agrarian South clashed in a conflict whose repercussions are felt to this day. At the heart of the conflict lay slavery and states' rights. On the one hand, there was a moral and ethical impulse to end the odious institution of slavery, embodied by the abolitionist movement and its sympathisers. On the other, there was fierce resistance from those who saw slavery as integral to the Southern economy and way of life, and who vigorously defended states' rights as a fundamental constitutional principle. The end of the Civil War in 1865, marked by General Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox, did more than simply end a military conflict. It paved the way for a profound social and political transformation. The adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, abolishing slavery, was a major victory for the ideals of freedom and equality. It was an affirmation that, in order to fully realise its fundamental promises, America had to root out institutions and practices that denied human dignity and equality. The country, though legally reunited, had to undertake the long and difficult process of reconstruction, not only to repair the physical destruction of the war, but also to rebuild the deep social, political and moral fissures that had divided the nation. It was a time of deep reflection, major reforms and persistent struggles to define the nature and direction of post-Civil War America. The suspension of expansion during the Civil War was a forced pause, a period when the nation was forced to look in the mirror and confront the contradictions and injustices that had been woven into its social and political fabric since its founding. In the years following the war, as America sought to heal its wounds and rebuild itself, the issues raised and lessons learned from this devastating conflict would profoundly influence its evolution, politics and national identity.

The expansionist drive of the United States after the Civil War

The resumption of expansionist policies in the post-Civil War United States embodies a nation in search of renewal and reconstitution. Scarred by the devastation and divisions of war, America looked to the West as a horizon of possibility, a land where dreams of prosperity, progress and national reconciliation could take shape. Westward expansion is not simply a geographical process; it is imbued with symbolic and pragmatic meanings. It is an outlet for the accumulated energies of a nation under reconstruction, a theatre where the aspirations of a unified, prosperous and powerful America can be articulated and realised. The government, in orchestrating and supporting this expansion, engages in a complex balancing act. It negotiated treaties with the indigenous nations, agreements which, although often marked by inequity and injustice, were instruments of the expansion strategy. The purchase of land in Mexico and other nations strengthened the southern frontier, while the annexation of Alaska in 1867, although geographically isolated from the westward movement, was a testament to the global reach and ambitions of the United States. However, each step westwards is also a step into the complexity of human interaction. Aboriginal peoples, new immigrants, pioneers and entrepreneurs meet, mix and clash in territories where the American dream takes many forms. Each treaty, each acquisition, each new settlement is an added layer to a national tapestry that is becoming richer and richer, but also more and more complex. This new phase of post-Civil War expansion is not simply a continuation of previous policies. It is coloured by the lessons, traumas and transformations of the war. A nation that has struggled to define its morality and identity is looking west with a renewed awareness of its potentials and contradictions. It is a time when faith in progress and prosperity is mixed with a growing recognition of the human and ethical costs of expansion. In this context, every step westward is also a step in America's ongoing quest to define itself, reinvent itself and fulfil its most fundamental promises.

The expansionist impulse of the United States in the aftermath of the Civil War was not confined to the vast expanses of the American West. It transcended continental boundaries, projecting into the turbulent seas of the Caribbean, traversing the tumultuous lands of Central America and stretching across the vast and complex geopolitical landscape of Asia and the Pacific. This period marks the emergence of the United States as a global force, a nation whose ambitions and interests know no borders, a power seeking global influence. The Big Stick Policy and the Good Neighbour Policy reflected the dualism of the American approach to expansion beyond its borders. Under President Theodore Roosevelt, the Big Stick Policy symbolised an assertive America, ready to wield its military and economic might to protect and promote its interests. It was a strategy of strength, in which power was used as an instrument of persuasion and assertion. In contrast to the vigour of the big stick, the Good Neighbour policy under Franklin D. Roosevelt embodies a more nuanced approach, where diplomacy, mutual respect and cooperation are the tools of international engagement. This policy reflects a recognition of the limits of force, an awareness that security, prosperity and influence are shaped as much by friendship and respect as by domination and coercion. Beyond the Western hemisphere, America's eyes are fixed on Asia and the Pacific. In these regions of diverse cultures and complex political dynamics, American expansion takes on a different dimension. It is influenced by the interplay of world powers, colonialism, national aspirations and regional conflicts. Post-Civil War America is a nation on the move, a power on the rise, continually defining and redefining its role on the world stage. Every policy, every action, every extension of influence is a chapter in the story of a nation searching for its identity and its place in a complex, interconnected world. It is a time of dynamism and determination, where the energy of domestic expansion merges with the aspiration for global influence, and where the lessons of the past and the challenges of the present meet in the relentless quest for the future.

Expansion through acquisition of trading territories

The acquisition of Alaska in 1867 embodies one of the most significant stages in American expansion, combining geopolitical and economic opportunism with a forward-looking and strategic vision. The exchange of 7.2 million dollars for a territory of substantial size and natural wealth was a bold move, testifying to the American desire to extend its footprint and consolidate its presence on the North American continent. At the heart of this transaction was the treaty of cession with Russia. At the time, Russia, ruled by Tsar Alexander II, was a nation contemplating its own economic and strategic needs. The sale of Alaska was seen not only as an opportunity to liquidate a distant and underdeveloped territory, but also as a means of injecting funds into the Russian treasury and strengthening ties with the United States. However, the reception of this acquisition in the United States is far from unanimous. The new American possession, with its vast wilderness, extreme climate and remoteness from the centres of American power, is provoking mixed reactions. For some, it is a "waste of money", an extravagant expense for a territory that seems to have little to offer in terms of immediate potential. For others, however, Alaska is seen in a different light. They look beyond the immediate challenges and envisage a territory rich in natural resources, a haven of precious minerals, dense forests and, later, abundant oil. For these visionaries, Alaska is not an expense, but an investment, a valuable addition that would enrich the nation and enhance its global stature. The debate surrounding the acquisition of Alaska reveals the tensions and contradictions inherent in a growing nation. It is a microcosm of wider debates about the nature and direction of American expansion, an echo of the heated conversations about how to balance prudence, opportunism and strategic vision. In this context, Alaska is transformed from a remote territory into a mirror reflecting the aspirations, uncertainties and ambitions of a nation in the throes of change.