Empires and States in the Middle East

Based on a course by Yilmaz Özcan.[1][2]

The Middle East, cradle of ancient civilisations and crossroads of cultural and commercial exchange, has played a central role in world history, particularly during the Middle Ages. This dynamic and diverse period saw the rise and fall of numerous empires and states, each leaving an indelible mark on the region's political, cultural and social landscape. From the expansion of the Islamic caliphates, with their cultural and scientific apogee, to the prolonged influence of the Byzantine Empire, via the incursions of the Crusaders and the Mongol conquests, the Medieval Middle East was a constantly evolving mosaic of powers. This period not only shaped the region's identity but also had a profound impact on the development of world history, building bridges between East and West. The study of Middle Eastern empires and states in the Middle Ages therefore offers a fascinating window onto a crucial period in human history, revealing stories of conquest, resilience, innovation and cultural interaction.

The Ottoman Empire

Foundation and expansion of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, founded at the end of the 13th century, is a fascinating example of an imperial power that had a profound effect on the history of three continents: Asia, Africa and Europe. Its foundation is generally attributed to Osman I, the leader of a Turkish tribe in the Anatolia region. The success of this empire lay in its ability to expand rapidly and establish an efficient administration over an immense territory. From the middle of the 14th century, the Ottomans began to expand their territory in Europe, gradually conquering parts of the Balkans. This expansion marked a major turning point in the balance of power in the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe. However, contrary to popular belief, the Ottoman Empire did not destroy Rome. In fact, the Ottomans laid siege to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, and conquered it in 1453, putting an end to that empire. This conquest was a major historical event, marking the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern era in Europe.

The Ottoman Empire is known for its complex administrative structure and religious tolerance, notably with the millet system, which allowed a degree of autonomy for non-Muslim communities. Its heyday extended from the 15th to the 17th century, during which time it exerted a considerable influence on trade, culture, science, art and architecture. The Ottomans introduced many innovations and were important mediators between East and West. However, from the 18th century onwards, the Ottoman Empire began to decline in the face of rising European powers and internal problems. This decline accelerated in the 19th century, eventually leading to the dissolution of the empire after the First World War. The legacy of the Ottoman Empire remains deeply rooted in the regions it ruled, influencing the cultural, political and social aspects of those societies to this day.

The Ottoman Empire, a remarkable political and military entity founded at the end of the 13th century by Osman I, has had a profound impact on the history of Eurasia. Emerging against a backdrop of political fragmentation and rivalries between the beylicats in Anatolia, this empire quickly demonstrated an exceptional ability to extend its influence, positioning itself as a dominant power in the region. The middle of the 14th century was a decisive turning point for the Ottoman Empire, notably with the conquest of Gallipoli in 1354. This victory, far from being a mere feat of arms, marked the first permanent Ottoman settlement in Europe and paved the way for a series of conquests in the Balkans. These military successes, combined with skilful diplomacy, enabled the Ottomans to consolidate their hold on strategic territories and to interfere in European affairs.

Under the leadership of rulers such as Mehmed II, famous for his conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottoman Empire not only reshaped the political landscape of the eastern Mediterranean but also initiated a period of profound cultural and economic transformation. The capture of Constantinople, which put an end to the Byzantine Empire, was a pivotal moment in world history, marking the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern era. The empire excelled in the art of warfare, often thanks to its disciplined and innovative army, but also through its pragmatic approach to governance, integrating diverse ethnic and religious groups under a centralised administrative system. This cultural diversity, coupled with political stability, encouraged a flourishing of the arts, science and commerce.

Conflicts and Military Challenges of the Ottoman Empire

Throughout its history, the Ottoman Empire experienced a series of spectacular conquests and significant setbacks that shaped its destiny and that of the regions it dominated. Their expansion, marked by major victories, was also punctuated by strategic failures. The Ottoman incursion into the Balkans was one of the first steps in their European expansion. This conquest not only extended their territory but also strengthened their position as the dominant power in the region. The capture of Istanbul in 1453 by Mehmed II, known as Mehmed the Conqueror, was a major historical event. This victory not only marked the end of the Byzantine Empire but also symbolised the indisputable rise of the Ottoman Empire as a superpower. Their expansion continued with the capture of Cairo in 1517, a crucial event that marked the integration of Egypt into the empire and the end of the Abbasid caliphate. Under Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottomans also conquered Baghdad in 1533, extending their influence over the rich and strategic lands of Mesopotamia.

However, Ottoman expansion was not without obstacles. The siege of Vienna in 1529, an ambitious attempt to further extend their influence in Europe, ended in failure. A further attempt in 1623 also failed, marking the limits of Ottoman expansion in Central Europe. These failures were key moments, illustrating the limits of the Ottoman Empire's military and logistical power in the face of organised European defences. Another major setback was the defeat at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. This naval battle, in which the Ottoman fleet was defeated by a coalition of European Christian forces, marked a turning point in Ottoman control of the Mediterranean. Although the Ottoman Empire managed to recover from this defeat and maintain a strong presence in the region, Lepanto symbolised the end of their uncontested expansion and marked the beginning of a period of more balanced maritime rivalries in the Mediterranean. Taken together, these events illustrate the dynamics of Ottoman expansion: a series of impressive conquests, interspersed with significant challenges and setbacks. They highlight the complexity of managing such a vast empire and the difficulty of maintaining constant expansion in the face of increasingly organised and resistant adversaries.

Reforms and Internal Transformations of the Ottoman Empire

The Russo-Ottoman War of 1768-1774 was a crucial episode in the history of the Ottoman Empire, marking not only the beginning of its significant territorial losses but also a change in its structure of political and religious legitimacy. The end of this war was marked by the signing of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (or Kutchuk-Kaïnardji) in 1774. This treaty had far-reaching consequences for the Ottoman Empire. Firstly, it resulted in the cession of significant territories to the Russian Empire, notably parts of the Black Sea and the Balkans. This loss not only reduced the size of the Empire but also weakened its strategic position in Eastern Europe and the Black Sea region. Secondly, the treaty marked a turning point in international relations at the time, by weakening the position of the Ottoman Empire on the European stage. The Empire, which had been a major and often dominant player in regional affairs, began to be perceived as a declining state, vulnerable to pressure and intervention from European powers.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the end of this war and the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca also had a significant impact on the internal structure of the Ottoman Empire. In the face of these defeats, the Empire began to place greater emphasis on the religious aspect of the Caliphate as a source of legitimacy. The Ottoman Sultan, already recognised as the political leader of the empire, began to be valued more as the Caliph, the religious leader of the Muslim community. This development was a response to the need to strengthen the authority and legitimacy of the Sultanate in the face of internal and external challenges, relying on religion as a unifying force and source of power. Thus, the Russo-Ottoman War and the resulting treaty marked a turning point in Ottoman history, symbolising both a territorial decline and a change in the nature of imperial legitimacy.

Foreign Influences and International Relations

The intervention in Egypt in 1801, where British and Ottoman forces joined forces to drive out the French, marked an important turning point in the history of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire. The appointment of Mehmet Ali, an Albanian officer, as pasha of Egypt by the Ottomans ushered in an era of profound transformation and semi-independence of Egypt from the Ottoman Empire. Mehmet Ali, often regarded as the founder of modern Egypt, initiated a series of radical reforms aimed at modernising Egypt. These reforms affected various aspects, including the army, the administration and the economy, and were inspired in part by European models. Under his leadership, Egypt underwent significant development, and Mehmet Ali sought to extend his influence beyond Egypt. Against this backdrop, the Nahda, or Arab Renaissance, gained considerable momentum. This cultural and intellectual movement, which sought to revitalise Arab culture and adapt it to modern challenges, benefited from the climate of reform and openness initiated by Mehmet Ali.

Mehmet Ali's son, Ibrahim Pasha, played a key role in Egypt's expansionist ambitions. In 1836, he launched an offensive against the Ottoman Empire, which was then weakened and in decline. This confrontation culminated in 1839, when Ibrahim's forces inflicted a major defeat on the Ottomans. However, the intervention of the European powers, notably Great Britain, Austria and Russia, prevented a total Egyptian victory. Under international pressure, a peace treaty was signed, recognising Egypt's de facto autonomy under the rule of Mehmet Ali and his descendants. This recognition marked an important step in Egypt's separation from the Ottoman Empire, although Egypt remained nominally under Ottoman suzerainty. The British position was particularly interesting. Initially allied with the Ottomans to contain French influence in Egypt, they eventually opted to support Egyptian autonomy under Mehmet Ali, recognising the changing political and strategic realities of the region. This decision reflected the British desire to stabilise the region while controlling vital trade routes, particularly those leading to India. The Egyptian episode in the early decades of the 19th century illustrates not only the complex power dynamics between the Ottoman Empire, Egypt and the European powers, but also the profound changes that were taking place in the political and social order of the Middle East at the time.

Modernisation and reform movements

Napoleon Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt in 1798 was a revelatory event for the Ottoman Empire, highlighting the fact that it was lagging behind the European powers in terms of modernisation and military capacity. This realisation was an important driving force behind a series of reforms known as the Tanzimat, launched in 1839 to modernise the empire and halt its decline. The Tanzimat, meaning "reorganisation" in Turkish, marked a period of profound transformation in the Ottoman Empire. One of the key aspects of these reforms was the modernisation of the organisation of the Dhimmis, the non-Muslim citizens of the empire. This included the creation of the Millet systems, which offered various religious communities a degree of cultural and administrative autonomy. The aim was to integrate these communities more effectively into the structure of the Ottoman state while preserving their distinct identities.

A second wave of reforms was initiated in an attempt to create a form of Ottoman citizenship, transcending religious and ethnic divisions. However, this attempt was often hampered by inter-communal violence, reflecting the deep tensions within the multi-ethnic and multi-faith empire. At the same time, these reforms met with significant resistance within certain factions of the army, who were hostile to changes perceived to threaten their traditional status and privileges. This resistance led to revolts and internal instability, exacerbating the challenges facing the empire.

Against this tumultuous backdrop, a political and intellectual movement known as the "Young Ottomans" emerged in the mid-19th century. This group sought to reconcile the ideals of modernisation and reform with the principles of Islam and Ottoman traditions. They advocated a constitution, national sovereignty, and more inclusive political and social reforms. The efforts of the Tanzimat and the ideals of the Young Ottomans were significant attempts to respond to the challenges facing the Ottoman Empire in a rapidly changing world. While these efforts brought about some positive changes, they also revealed the deep fissures and tensions within the empire, foreshadowing the even greater challenges that would arise in the final decades of its existence.

In 1876, a crucial stage in the Tanzimat process was reached with the accession to power of Sultan Abdülhamid II, who introduced the Ottoman Empire's first monarchical constitution. This period marked a significant turning point, attempting to reconcile the principles of modernisation with the traditional structure of the empire. The 1876 constitution represented an effort to modernise the administration of the empire and to establish a legislative system and parliament, reflecting the liberal and constitutional ideals in vogue in Europe at the time. However, Abdülhamid II's reign was also marked by a strong rise in pan-Islamism, an ideology aimed at strengthening ties between Muslims within the empire and beyond, against a backdrop of growing rivalry with Western powers.

Abdülhamid II used pan-Islamism as a tool to consolidate his power and counter external influences. He invited Muslim leaders and dignitaries to Istanbul and offered to educate their children in the Ottoman capital, an initiative designed to strengthen cultural and political ties within the Muslim world. However, in 1878, in a surprising U-turn, Abdülhamid II suspended the constitution and closed parliament, marking a return to autocratic rule. This decision was motivated in part by fears of insufficient control over the political process and the rise of nationalist movements within the empire. The Sultan thus strengthened his direct control over the government, while continuing to promote pan-Islamism as a means of legitimisation.

In this context, Salafism, a movement aimed at returning to the practices of first-generation Islam, was influenced by the ideals of pan-Islamism and the Nahda (Arab Renaissance). Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, often regarded as the precursor of the modern Salafist movement, played a key role in spreading these ideas. Al-Afghani advocated a return to the original principles of Islam while encouraging the adoption of certain forms of technological and scientific modernisation. The Tanzimat period and the reign of Abdülhamid II thus illustrate the complexity of attempts at reform in the Ottoman Empire, torn between the demands of modernisation and the maintenance of traditional structures and ideologies. The impact of this period was felt well beyond the fall of the Empire, influencing political and religious movements throughout the modern Muslim world.

Decline and fall of the Ottoman Empire

The "Eastern Question", a term used mainly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, refers to a complex and multi-dimensional debate concerning the future of the gradually declining Ottoman Empire. This issue emerged as a result of the Empire's successive territorial losses, the emergence of Turkish nationalism, and the growing separation from non-Muslim territories, particularly in the Balkans. As early as 1830, with the independence of Greece, the Ottoman Empire began to lose its European territories. This trend continued with the Balkan Wars and accelerated during the First World War, culminating in the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920 and the founding of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. These losses profoundly altered the political geography of the region.

Against this backdrop, Turkish nationalism gained momentum. This movement sought to redefine the empire's identity around the Turkish element, in contrast to the multi-ethnic and multi-religious model that had prevailed until then. This rise in nationalism was a direct response to the gradual dismantling of the empire and the need to forge a new national identity. At the same time, the idea of forming a kind of "international of Islam" emerged, notably under the impetus of Sultan Abdülhamid II with his pan-Islamism. This idea envisaged the creation of a union or cooperation between Muslim nations, inspired by certain similar ideas in Europe, where internationalism sought to unite peoples beyond national borders. The aim was to create a united front of Muslim peoples to resist the influence and intervention of Western powers, while preserving the interests and independence of Muslim territories.

However, the implementation of such an idea proved difficult due to diverse national interests, regional rivalries and the growing influence of nationalist ideas. Moreover, political developments, notably the First World War and the rise of nationalist movements in various parts of the Ottoman Empire, made the vision of an "international of Islam" increasingly unattainable. The Question of the East as a whole therefore reflects the profound geopolitical and ideological transformations that took place in the region during this period, marking the end of a multi-ethnic empire and the birth of new nation-states with their own national identities and aspirations.

The 'Weltpolitik' or world policy adopted by Germany in the late 19th and early 20th centuries played a crucial role in the geopolitical dynamics involving the Ottoman Empire. This policy, initiated under the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II, aimed to extend Germany's influence and prestige on the international stage, notably through colonial expansion and strategic alliances. The Ottoman Empire, seeking to escape pressure from Russia and Great Britain, found in Germany a potentially useful ally. This alliance was symbolised in particular by the project to build the Berlin-Baghdad Railway (BBB). This railway, designed to link Berlin to Baghdad via Byzantium (Istanbul), was of considerable strategic and economic importance. It was intended not only to facilitate trade and communications, but also to strengthen German influence in the region and provide a counterweight to British and Russian interests in the Middle East.

For the Panturquists and supporters of the Ottoman Empire, the alliance with Germany was viewed favourably. The Panturquists, who advocated the unity and solidarity of the Turkish-speaking peoples, saw in this alliance an opportunity to strengthen the position of the Ottoman Empire and counter external threats. The alliance with Germany offered an alternative to pressure from traditional powers such as Russia and Britain, which had long influenced Ottoman politics and affairs. This relationship between the Ottoman Empire and Germany reached its peak during the First World War, when the two nations found themselves allied in the Central Powers. This alliance had important consequences for the Ottoman Empire, both militarily and politically, and played a role in the events that eventually led to the dissolution of the Empire after the war. German Weltpolitik and the Berlin-Baghdad railway project were key elements in the Ottoman Empire's strategy to preserve its integrity and independence in the face of pressure from the Great Powers. This period marked a significant moment in the history of the Empire, illustrating the complexity of alliances and geopolitical interests at the beginning of the 20th century.

The year 1908 marked a decisive turning point in the history of the Ottoman Empire with the start of the second constitutional period, triggered by the Young Turks movement, represented mainly by the Union and Progress Committee (CUP). This movement, initially formed by reformist Ottoman officers and intellectuals, sought to modernise the Empire and save it from collapse.

Under pressure from the CUP, Sultan Abdülhamid II was forced to reinstate the 1876 constitution, which had been suspended since 1878, marking the start of the second constitutional period. This restoration of the constitution was seen as a step towards the modernisation and democratisation of the Empire, with the promise of more extensive civil and political rights and the establishment of parliamentary government. However, this period of reform soon came up against major challenges. In 1909, traditional conservative and religious circles, dissatisfied with the reforms and the growing influence of the Unionists, attempted a coup to overthrow the constitutional government and re-establish the absolute authority of the Sultan. This attempt was motivated by opposition to the rapid modernisation and secular policies promoted by the Young Turks, as well as fears of a loss of privileges and influence. However, the Young Turks, using this episode of counter-revolution as a pretext, succeeded in crushing the resistance and consolidating their power. This period was marked by increased repression against opponents and the centralisation of power in the hands of the CUP.

In 1913, the situation culminated in the seizure of parliament by CUP leaders, an event often described as a coup d'état. This marked the end of the Empire's brief constitutional and parliamentary experiment and the establishment of an increasingly authoritarian regime led by the Young Turks. Under their rule, the Ottoman Empire saw substantial reforms but also more centralising and nationalist policies, laying the foundations for the events that would unfold during and after the First World War. This tumultuous period reflects the tensions and internal struggles within the Ottoman Empire, torn between the forces of change and tradition, and laying the groundwork for the radical transformations that would follow in the empire's later years.

In 1915, during the First World War, the Ottoman Empire undertook what is now widely recognised as the Armenian genocide, a tragic and dark episode in history. This policy involved the systematic deportation, mass murder and death of the Armenian population living in the Empire. The campaign against the Armenians began with arrests, executions and mass deportations. Armenian men, women, children and the elderly were forced from their homes and sent on death marches through the Syrian desert, where many died of hunger, thirst, disease or violence. Many Armenian communities, which had a long and rich history in the region, were destroyed.

Estimates of the number of victims vary, but it is generally believed that between 800,000 and 1.5 million Armenians perished during this period. The genocide has had a lasting impact on the global Armenian community and remains a subject of great sensitivity and controversy, not least because of the denial or downplaying of these events by some groups. The Armenian genocide is often considered to be one of the first modern genocides and served as a dark precursor to other mass atrocities during the 20th century. It has also played a key role in the formation of modern Armenian identity, with the memory of the genocide continuing to be central to Armenian consciousness. The recognition and commemoration of these events continues to be an important issue in international relations, particularly in discussions on human rights and the prevention of genocide.

The Persian Empire

The Origins and Completion of the Persian Empire

The history of the Persian Empire, now known as Iran, is characterised by impressive cultural and political continuity, despite dynastic changes and foreign invasions. This continuity is a key element in understanding the historical and cultural evolution of the region.

The Medes Empire, established in the early 7th century BC, was one of the first great powers in the history of Iran. This empire played a crucial role in laying the foundations of Iranian civilisation. However, it was overthrown by Cyrus II of Persia, also known as Cyrus the Great, around 550 BC. Cyrus' conquest of Media marked the beginning of the Achaemenid Empire, a period of great expansion and cultural influence. The Achaemenids created a vast empire stretching from the Indus to Greece, and their reign was characterised by efficient administration and a policy of tolerance towards the different cultures and religions within the empire. The fall of this empire was brought about by Alexander the Great in 330 BC, but this did not put an end to Persian cultural continuity.

After a period of Hellenistic domination and political fragmentation, the Sassanid dynasty emerged in 224 AD. Founded by Ardashir I, it marked the beginning of a new era for the region, lasting until 624 AD. Under the Sassanids, Greater Iran experienced a period of cultural and political renaissance. The capital, Ctesiphon, became a centre of power and culture, reflecting the grandeur and influence of the empire. The Sassanids played an important role in the development of art, architecture, literature and religion in the region. They championed Zoroastrianism, which had a profound influence on Persian culture and identity. Their empire was marked by constant conflict with the Roman Empire and later the Byzantine Empire, culminating in costly wars that weakened both empires. The fall of the Sassanid dynasty came in the wake of the Muslim conquests of the 7th century, but Persian culture and traditions continued to influence the region, even in later Islamic periods. This resilience and ability to integrate new elements while preserving a distinct cultural core is at the heart of the notion of continuity in Persian history.

Iran under Islam: Conquests and Transformations

From 642 onwards, Iran entered a new era in its history with the start of the Islamic period, following the Muslim conquests. This period marked a significant turning point not only in the political history of the region, but also in its social, cultural and religious structure. The conquest of Iran by Muslim armies began shortly after the death of the prophet Mohammed in 632. In 642, with the capture of the Sassanid capital Ctesiphon, Iran came under the control of the nascent Islamic Empire. This transition was a complex process, involving both military conflict and negotiation. Under Muslim rule, Iran underwent profound changes. Islam gradually became the dominant religion, replacing Zoroastrianism, which had been the state religion under previous empires. However, this transition did not happen overnight, and there was a period of coexistence and interaction between the different religious traditions.

Iranian culture and society were profoundly influenced by Islam, but they also exerted a significant influence on the Islamic world. Iran became an important centre of Islamic culture and knowledge, with remarkable contributions in fields such as philosophy, poetry, medicine and astronomy. Iconic Iranian figures such as the poet Rumi and the philosopher Avicenna (Ibn Sina) played a major role in Islamic cultural and intellectual heritage. This period was also marked by successive dynasties, such as the Umayyads, the Abbasids, the Saffarids, the Samanids, the Bouyids and later the Seljuks, each of which contributed to the richness and diversity of Iranian history. Each of these dynasties brought its own nuances to the region's governance, culture and society.

Emergence and influence of the Sefevids

In 1501, a major event in the history of Iran and the Middle East took place when Shah Ismail I established the Sefevid Empire in Azerbaijan. This marked the beginning of a new era not only for Iran but for the region as a whole, with the introduction of Duodeciman Shiism as the state religion, a change that profoundly influenced Iran's religious and cultural identity. The Sefevid Empire, which reigned until 1736, played a crucial role in consolidating Iran as a distinct political and cultural entity. Shah Ismail I, a charismatic leader and talented poet, succeeded in unifying various regions under his control, creating a centralised and powerful state. One of his most significant decisions was to impose Duodecimal Shiism as the official religion of the empire, an act that had profound implications for the future of Iran and the Middle East.

This 'Shiitisation' of Iran, which involved the forced conversion of Sunni populations and other religious groups to Shiism, was a deliberate strategy to differentiate Iran from its Sunni neighbours, notably the Ottoman Empire, and to consolidate Sefevid power. This policy also had the effect of reinforcing Iran's Shiite identity, which has become a distinctive feature of the Iranian nation to this day. Under the Sefevids, Iran experienced a period of cultural and artistic renaissance. The capital, Isfahan, became one of the most important centres of art, architecture and culture in the Islamic world. The Sefevids encouraged the development of the arts, including painting, calligraphy, poetry and architecture, creating a rich and lasting cultural legacy. However, the empire was also marked by internal and external conflicts, including wars against the Ottoman Empire and the Uzbeks. These conflicts, along with internal challenges, ultimately contributed to the empire's decline in the 18th century.

The Battle of Chaldiran, which took place in 1514, is a significant event in the history of the Sephardic Empire and the Ottoman Empire, marking not only a military turning point but also the formation of an important political dividing line between the two empires. In this battle, Sefevid forces, led by Shah Ismail I, clashed with the Ottoman army under the command of Sultan Selim I. The Sefevids, although valiant in battle, were defeated by the Ottomans, largely because of the latter's technological superiority, in particular their effective use of artillery. This defeat had major consequences for the Sephardic Empire. One of the immediate results of the Battle of Chaldiran was the loss of significant territory for the Sefevids. The Ottomans succeeded in seizing the eastern half of Anatolia, considerably reducing Sefevid influence in the region. This defeat also established a lasting political boundary between the two empires, which has become an important geopolitical marker in the region. The defeat of the Sefevids also had repercussions for the Alevis, a religious community that supported Shah Ismail I and his policy of Shiitisation. Following the battle, many Alevis were persecuted and massacred in the decade that followed, due to their allegiance to the Sefevid Shah and their distinct religious beliefs, which were at odds with the dominant Sunni practices of the Ottoman Empire.

After his victory at Chaldiran, Sultan Selim I continued his expansion, and in 1517 he conquered Cairo, putting an end to the Abbasid Caliphate. This conquest not only extended the Ottoman Empire as far as Egypt, but also strengthened the Sultan's position as an influential Muslim leader, as he assumed the title of Caliph, symbolising religious and political authority over the Sunni Muslim world. The Battle of Chaldiran and its aftermath therefore illustrate the intense rivalry between the two great Muslim powers of the time, significantly shaping the political, religious and territorial history of the Middle East.

The Qajar Dynasty and the Modernisation of Iran

In 1796, Iran saw the emergence of a new ruling dynasty, the Qajar (or Kadjar) dynasty, founded by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar. Of Turkmen origin, this dynasty replaced the Zand dynasty and ruled Iran until the early 20th century. Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, after unifying various factions and territories in Iran, proclaimed himself Shah in 1796, marking the official start of Qajar rule. This period was significant for several reasons in Iranian history. Under the Qajars, Iran experienced a period of centralisation of power and territorial consolidation after years of turmoil and internal divisions. The capital was transferred from Shiraz to Tehran, which became the political and cultural centre of the country. This period was also marked by complex international relations, particularly with the imperialist powers of the time, Russia and Great Britain. The Qajars had to navigate a difficult international environment, with Iran often caught up in the geopolitical rivalries of the great powers, particularly in the 'Great Game' between Russia and Great Britain. These interactions often led to the loss of territory and major economic and political concessions for Iran.

Culturally, the Qajar period is known for its distinctive art, particularly painting, architecture and decorative arts. The Qajar court was a centre of artistic patronage, and this period saw a unique blend of traditional Iranian styles with modern European influences. However, the Qajar dynasty was also criticised for its inability to effectively modernise the country and meet the needs of its population. This failure led to internal discontent and laid the foundations for the reform movements and constitutional revolutions that occurred in the early 20th century. The Qajar dynasty represents an important period in Iranian history, marked by efforts to centralise power, diplomatic challenges and significant cultural contributions, but also by internal struggles and external pressures that shaped the country's subsequent development.

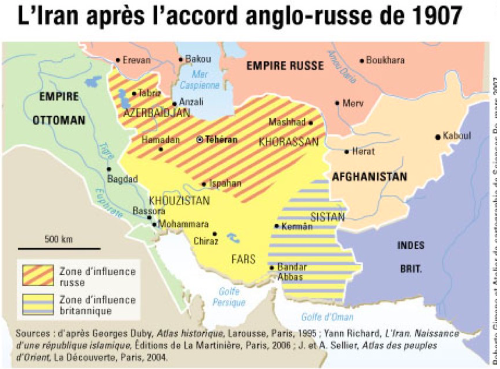

Iran in the 20th Century: Towards a Constitutional Monarchy

In 1906, Iran experienced a historic moment with the start of its constitutional period, a major step in the country's political modernisation and the struggle for democracy. This development was largely influenced by social and political movements demanding a limitation of the absolute power of the monarch and more representative and constitutional governance. The Iranian Constitutional Revolution led to the adoption of the country's first constitution in 1906, marking Iran's transition to a constitutional monarchy. This constitution provided for the creation of a parliament, or Majlis, and put in place laws and structures to modernise and reform Iranian society and government. However, this period was also marked by foreign interference and the division of the country into spheres of influence. Iran was caught up in rivalries between Great Britain and Russia, each seeking to extend its influence in the region. These powers established different "international orders" or zones of influence, limiting Iran's sovereignty.

The discovery of oil in 1908-1909 added a new dimension to the situation in Iran. The discovery, made in the Masjed Soleyman region, quickly attracted the attention of foreign powers, particularly Great Britain, which sought to control Iran's oil resources. This discovery considerably increased Iran's strategic importance on the international stage and also complicated the country's internal dynamics. Despite these external pressures and the stakes associated with natural resources, Iran maintained a policy of neutrality, particularly during global conflicts such as the First World War. This neutrality was in part an attempt to preserve its autonomy and resist foreign influences that sought to exploit its resources and control its politics. The early 20th century was a period of change and challenge for Iran, characterised by efforts at political modernisation, the emergence of new economic challenges with the discovery of oil, and navigation in a complex international environment.

The Ottoman Empire in the First World War

Diplomatic manoeuvres and the formation of alliances

The Ottoman Empire's entry into the First World War in 1914 was preceded by a period of complex diplomatic and military manoeuvring, involving several major powers, including Britain, France and Germany. After exploring potential alliances with Britain and France, the Ottoman Empire finally opted for an alliance with Germany. This decision was influenced by several factors, including pre-existing military and economic ties between the Ottomans and Germany, as well as perceptions of the intentions of the other major European powers.

Despite this alliance, the Ottomans were reluctant to enter the conflict directly, aware of their internal difficulties and military limitations. However, the situation changed with the Dardanelles incident. The Ottomans used warships (some of which had been acquired from Germany) to bombard Russian ports on the Black Sea. This action drew the Ottoman Empire into the war alongside the Central Powers and against the Allies, notably Russia, France and Great Britain.

In response to the Ottoman Empire's entry into the war, the British launched the Dardanelles Campaign in 1915. The aim was to take control of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, opening up a sea route to Russia. However, the campaign ended in failure for the Allied forces and resulted in heavy casualties on both sides. At the same time, Britain formalised its control over Egypt, proclaiming the British Protectorate of Egypt in 1914. This decision was strategically motivated, largely to secure the Suez Canal, a vital crossing point for British shipping routes, particularly for access to the colonies in Asia. These events illustrate the complexity of the geopolitical situation in the Middle East during the First World War. The decisions taken by the Ottoman Empire had important implications, not only for their own empire but also for the configuration of the Middle East in the post-war period.

The Arab Revolt and Changing Dynamics in the Middle East

During the First World War, the Allies sought to weaken the Ottoman Empire by opening a new front in the south, leading to the famous Arab Revolt of 1916. This revolt was a key moment in the history of the Middle East and marked the beginning of the Arab nationalist movement. Hussein ben Ali, the Sherif of Mecca, played a central role in this revolt. Under his leadership, and with the encouragement and support of figures such as T.E. Lawrence, known as Lawrence of Arabia, the Arabs rose up against Ottoman domination in the hope of creating a unified Arab state. This aspiration for independence and unification was motivated by a desire for national liberation and by the promise of autonomy made by the British, in particular by General Henry MacMahon.

The Arab Revolt had several significant successes. In June 1917, Faisal, son of Hussein ben Ali, won the Battle of Aqaba, a strategic turning point in the revolt. This victory opened up a crucial front against the Ottomans and boosted the morale of the Arab forces. With the help of Lawrence of Arabia and other British officers, Faisal succeeded in uniting several Arab tribes in the Hijaz, leading to the liberation of Damascus in 1917. In 1920, Faisal proclaimed himself King of Syria, affirming the Arab aspiration for self-determination and independence. However, his ambitions came up against the reality of international politics. The Sykes-Picot Accords of 1916, a secret arrangement between Britain and France, had already divided large parts of the Middle East into zones of influence, undermining hopes of a great unified Arab kingdom. The Arab Revolt was a decisive factor in weakening the Ottoman Empire during the war and laid the foundations for modern Arab nationalism. However, the post-war period saw the division of the Middle East into a number of nation-states under European mandate, putting the realisation of a unified Arab state, as envisaged by Hussein ben Ali and his supporters, a long way off.

Internal challenges and the Armenian Genocide

The First World War was marked by complex developments and changing dynamics, including Russia's withdrawal from the conflict as a result of the Russian Revolution in 1917. This withdrawal had significant implications for the course of the war and for the other belligerent powers. Russia's withdrawal eased the pressure on the Central Powers, particularly Germany, which could now concentrate its forces on the Western Front against France and its allies. This change worried Great Britain and her allies, who were looking for ways to maintain the balance of power.

With regard to the Bolshevik Jews, it is important to note that the Russian revolutions of 1917 and the rise of Bolshevism were complex phenomena influenced by various factors within Russia. Although there were Jews among the Bolsheviks, as in many political movements of the time, their presence should not be over-interpreted or used to promote simplistic or anti-Semitic narratives. As far as the Ottoman Empire is concerned, Enver Pasha, one of the leaders of the Young Turk movement and Minister of War, played a key role in the conduct of the war. In 1914, he launched a disastrous offensive against the Russians in the Caucasus, which resulted in a major defeat for the Ottomans at the Battle of Sarikamish.

Enver Pasha's defeat had tragic consequences, including the outbreak of the Armenian genocide. Looking for a scapegoat to explain the defeat, Enver Pasha and other Ottoman leaders accused the empire's Armenian minority of collusion with the Russians. These accusations fuelled a campaign of systematic deportations, massacres and exterminations against the Armenians, culminating in what is now recognised as the Armenian genocide. This genocide represents one of the darkest episodes of the First World War and the history of the Ottoman Empire, highlighting the horrors and tragic consequences of large-scale conflict and policies of ethnic hatred.

Post-war settlement and redefinition of the Middle East

The Paris Peace Conference, which began in January 1919, was a crucial moment in the redefinition of world order after the First World War. The conference brought together the leaders of the major Allied powers to discuss the terms of peace and the geopolitical future, including the territories of the failing Ottoman Empire. One of the major issues discussed at the conference concerned the future of the Ottoman territories in the Middle East. The Allies were considering redrawing the borders of the region, influenced by various political, strategic and economic considerations, including control of oil resources. Although the conference theoretically allowed the nations concerned to present their points of view, in practice several delegations were marginalised or their demands ignored. For example, the Egyptian delegation, which sought to discuss Egyptian independence, faced obstacles, illustrated by the exile of some of its members to Malta. This situation reflects the unequal power dynamics at the conference, where the interests of the predominant European powers often prevailed.

Faisal, son of Hussein bin Ali and leader of the Arab Revolt, played an important role at the conference. He represented Arab interests and argued for the recognition of Arab independence and autonomy. Despite his efforts, the decisions taken at the conference did not fully meet Arab aspirations for an independent and unified state. Faisal went on to create a state in Syria, proclaiming himself King of Syria in 1920. However, his ambitions were short-lived, as Syria was placed under French mandate after the San Remo Conference in 1920, a decision that formed part of the division of the Middle East between the European powers in accordance with the Sykes-Picot agreements of 1916. The Paris Conference and its outcomes therefore had profound implications for the Middle East, laying the foundations for many of the regional tensions and conflicts that continue to this day. The decisions taken reflected the interests of the victorious powers of the First World War, often to the detriment of the national aspirations of the peoples of the region.

The agreement between Georges Clemenceau, representing France, and Faisal, leader of the Arab Revolt, as well as the discussions around the creation of new states in the Middle East, are key elements of the post-First World War period that have shaped the geopolitical order of the region. The Clemenceau-Fayçal agreement was seen as highly favourable to France. Fayçal, seeking to secure a form of autonomy for the Arab territories, had to make significant concessions. France, which had colonial and strategic interests in the region, used its position at the Paris Conference to assert its control, particularly over territories such as Syria and Lebanon. The Lebanese delegation won the right to create a separate state, Greater Lebanon, under French mandate. This decision was influenced by the aspirations of Lebanon's Maronite Christian communities, who sought to establish a state with extended borders and a degree of autonomy under French tutelage. On the Kurdish question, promises were made to create a Kurdistan. These promises were in part a recognition of Kurdish nationalist aspirations and a means of weakening the Ottoman Empire. However, the implementation of this promise proved complex and was largely ignored in the post-war treaties.

All these elements converged in the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, which formalised the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire. This treaty redrew the borders of the Middle East, creating new states under French and British mandates. The treaty also provided for the creation of an autonomous Kurdish entity, although this provision was never implemented. The Treaty of Sèvres, although never fully ratified and later replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, was a decisive moment in the history of the region. It laid the foundations for the modern political structure of the Middle East, but also sowed the seeds of many future conflicts, due to ignorance of the ethnic, cultural and historical realities of the region.

The Transition to the Republic and the Rise of Atatürk

After the end of the First World War, the Ottoman Empire, weakened and under pressure, agreed to sign the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. This treaty, which dismantled the Ottoman Empire and redistributed its territories, seemed to mark the conclusion of the long-running "Eastern Question" concerning the fate of the empire. However, far from ending tensions in the region, the Treaty of Sevres exacerbated nationalist feelings and led to new conflicts.

In Turkey, a strong nationalist resistance, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, formed in opposition to the Treaty of Sèvres. This nationalist movement opposed the treaty's provisions, which imposed severe territorial losses and increased foreign influence on Ottoman territory. The resistance fought against various groups, including the Armenians, the Greeks in Anatolia and the Kurds, with the aim of forging a new, homogenous Turkish nation-state. The ensuing War of Turkish Independence was a period of intense conflict and territorial recomposition. The Turkish nationalist forces succeeded in pushing back the Greek armies in Anatolia and countering the other rebel groups. This military victory was a key element in the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923.

As a result of these events, the Treaty of Sèvres was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. This new treaty recognised the borders of the new Republic of Turkey and cancelled the most punitive provisions of the Treaty of Sevres. The Treaty of Lausanne marked an important stage in the establishment of modern Turkey as a sovereign and independent state, redefining its role in the region and in international affairs. Not only did these events redraw the political map of the Middle East, they also marked the end of the Ottoman Empire and opened a new chapter in Turkey's history, with repercussions that continue to influence the region and the world to this day.

Abolition of the Caliphate and its repercussions

The abolition of the Caliphate in 1924 was a major event in the modern history of the Middle East, marking the end of an Islamic institution that had lasted for centuries. The decision was taken by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, as part of his reforms to secularise and modernise the new Turkish state. The abolition of the Caliphate was a blow to the traditional structure of Islamic authority. The Caliph had been considered the spiritual and temporal head of the Muslim community (ummah) since the time of the Prophet Mohammed. With the abolition of the Caliphate, this central institution of Sunni Islam disappeared, leaving a vacuum in Muslim leadership.

In response to Turkey's abolition of the Caliphate, Hussein ben Ali, who had become King of the Hijaz after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, proclaimed himself Caliph. Hussein, a member of the Hashemite family and a direct descendant of the Prophet Mohammed, sought to claim this position in order to maintain a form of spiritual and political continuity in the Muslim world. However, Hussein's claim to the Caliphate was not widely recognised and was short-lived. His position was weakened by internal and external challenges, including opposition from the Saud family, which controlled much of the Arabian Peninsula. The rise of the Sauds, under the leadership of Abdelaziz Ibn Saud, eventually led to the conquest of Hijaz and the establishment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The ousting of Hussein bin Ali by the Sauds symbolised the radical shift in power in the Arabian Peninsula and marked the end of his ambitions for a caliphate. This event also highlighted the political and religious transformations underway in the Muslim world, marking the beginning of a new era in which politics and religion would begin to follow more distinct paths in many Muslim countries.

The period following the First World War was crucial for the political redefinition of the Middle East, with significant interventions by European powers, notably France and Great Britain. In 1920, a major event took place in Syria, marking a turning point in the history of the region. Faisal, the son of Hussein ben Ali and a central figure in the Arab Revolt, had established an Arab kingdom in Syria after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, aspiring to realise the dream of a unified Arab state. However, his ambitions came up against the reality of French colonial interests. After the Battle of Maysaloun in July 1920, the French, acting under their League of Nations mandate, took control of Damascus and dismantled Faisal's Arab state, ending his reign in Syria. This French intervention reflected the complex dynamics of the post-war period, in which the national aspirations of the peoples of the Middle East were often overshadowed by the strategic interests of the European powers. Fayçal, deposed from his Syrian throne, nevertheless found a new destiny in Iraq. In 1921, under British auspices, he was installed as the first king of the Hashemite monarchy of Iraq, a strategic move on the part of the British to ensure favourable leadership and stability in this oil-rich region.

At the same time, in Transjordan, another political manoeuvre was implemented by the British. To thwart Zionist aspirations in Palestine and maintain a balance in their mandate, they created the Kingdom of Transjordan in 1921 and installed Abdallah, another son of Hussein ben Ali, there. This decision was intended to provide Abdallah with a territory over which to rule, while keeping Palestine under direct British control. The creation of Transjordan was an important step in the formation of the modern state of Jordan and illustrated how colonial interests shaped the borders and political structures of the modern Middle East. These developments in the region after the First World War demonstrate the complexity of Middle Eastern politics in the inter-war period. The decisions taken by the European proxy powers, influenced by their own strategic and geopolitical interests, had lasting consequences, laying the foundations for the state structures and conflicts that continue to affect the Middle East. These events also highlight the struggle between the national aspirations of the peoples of the region and the realities of European colonial rule, a recurring theme in the history of the Middle East in the twentieth century.

The repercussions of the San Remo Conference

The San Remo Conference, held in April 1920, was a defining moment in post-First World War history, particularly for the Middle East. It focused on the allocation of mandates over the former provinces of the Ottoman Empire, following its defeat and break-up. At this conference, the victorious Allied Powers decided on the distribution of the mandates. France obtained the mandate over Syria and Lebanon, thereby taking control of two strategically important and culturally rich regions. For their part, the British were given mandates over Transjordan, Palestine and Mesopotamia, the latter being renamed Iraq. These decisions reflected the geopolitical and economic interests of the colonial powers, particularly in terms of access to resources and strategic control.

In parallel with these developments, Turkey, under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was engaged in a process of national redefinition. After the war, Turkey sought to establish new national borders. This period was marked by tragic conflicts, notably the crushing of the Armenians, which followed the Armenian genocide perpetrated during the war. In 1923, after several years of struggle and diplomatic negotiations, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk succeeded in renegotiating the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres, which had been imposed on Turkey in 1920 and was widely regarded as humiliating and unacceptable by Turkish nationalists. The Treaty of Lausanne, signed in July 1923, replaced the Treaty of Sevres and recognised the sovereignty and borders of the new Republic of Turkey. This treaty marked the official end of the Ottoman Empire and laid the foundations of the modern Turkish state.

The Treaty of Lausanne is considered a major success for Mustafa Kemal and the Turkish nationalist movement. Not only did it redefine Turkey's borders, but it also enabled the new republic to make a fresh start on the international stage, freed from the restrictions of the Treaty of Sèvres. These events, from the San Remo Conference to the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, had a profound impact on the Middle East, shaping national borders, international relations and political dynamics in the region for decades to come.

Allied promises and Arab demands

During the First World War, the dismantling and partition of the Ottoman Empire was at the heart of the concerns of the Allied powers, mainly Great Britain, France and Russia. These powers, anticipating a victory over the Ottoman Empire, an ally of the Central Powers, began planning the partition of its vast territories.

In 1915, as the First World War raged, crucial negotiations took place in Constantinople, involving representatives of Great Britain, France and Russia. These discussions centred on the future of the territories of the Ottoman Empire, which was then allied to the Central Powers. The Ottoman Empire, weakened and in decline, was seen by the Allies as a territory to be divided in the event of victory. These negotiations in Constantinople were strongly motivated by strategic and colonial interests. Each power sought to extend its influence in the region, which was strategically important because of its geographical position and resources. Russia was particularly interested in controlling the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits, which were essential for its access to the Mediterranean. France and Britain, meanwhile, were looking to expand their colonial empires and secure their access to the region's resources, particularly oil. However, it is important to note that, although these discussions had a significant impact on the future of the Ottoman territories, the most significant and detailed agreements concerning their division were formalised later, notably in the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, concluded by British diplomat Mark Sykes and French diplomat François Georges-Picot, represents a key moment in the history of the Middle East, profoundly influencing the geopolitical configuration of the region after the First World War. This agreement was designed to define the division of the territories of the Ottoman Empire between Great Britain, France and, to a certain extent, Russia, although Russian participation was rendered null and void by the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Sykes-Picot Agreement established zones of influence and control for France and Britain in the Middle East. Under this agreement, France was to gain direct control or influence over Syria and Lebanon, while Britain was to have similar control over Iraq, Jordan and an area around Palestine. However, this agreement did not precisely define the borders of the future states, leaving that to later negotiations and agreements.

The importance of the Sykes-Picot agreement lies in its role as the "genesis" of collective memories concerning the geographical space in the Middle East. It symbolises the imperialist intervention and manipulations of the European powers in the region, often in defiance of local ethnic, religious and cultural identities. Although the agreement influenced the creation of states in the Middle East, the actual borders of these states were determined by subsequent balances of power, diplomatic negotiations and geopolitical realities that evolved after the First World War. The consequences of the Sykes-Picot agreement were reflected in the League of Nations mandates given to France and Great Britain after the war, leading to the formation of several modern Middle Eastern states. However, the borders drawn and decisions taken often ignored the ethnic and religious realities on the ground, sowing the seeds of future conflict and tension in the region. The legacy of the agreement remains a subject of debate and discontent in the contemporary Middle East, symbolising the interventions and divisions imposed by foreign powers.

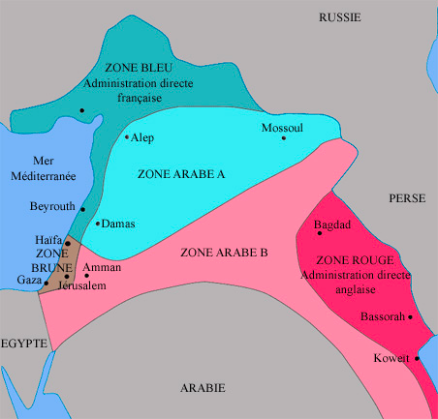

This map illustrates the division of the territories of the Ottoman Empire as laid down in the Sykes-Picot agreements of 1916 between France and Great Britain, with zones of direct administration and zones of influence.

The "Blue Zone", representing direct French administration, covered the regions that would later become Syria and Lebanon. This shows that France intended to exercise direct control over strategic urban centres and coastal regions. The "Red Zone", under direct British administration, encompassed the future Iraq with key cities such as Baghdad and Basra, as well as Kuwait, which was represented in a detached manner. This zone reflected the British interest in the oil-producing regions and their strategic importance as a gateway to the Persian Gulf. The "Brown Zone", representing Palestine (including places such as Haifa, Jerusalem and Gaza), is not explicitly defined in the Sykes-Picot Agreement in terms of direct control, but is generally associated with British influence. It later became a British mandate and the focus of political tension and conflict as a result of the Balfour Declaration and the Zionist movement.

Arab Areas A and B" were regions where Arab autonomy was to be recognised under French and British supervision respectively. This was interpreted as a concession to Arab aspirations for some form of autonomy or independence, which had been encouraged by the Allies during the war to win Arab support against the Ottoman Empire. What this map does not show is the complexity and multiple promises made by the Allies during the war, which were often contradictory and led to feelings of betrayal among local populations after the agreement was revealed. The map represents a simplification of the Sykes-Picot agreements, which in reality were much more complex and underwent changes over time as a result of political developments, conflicts and international pressure.

The revelation of the Sykes-Picot agreements by the Russian Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution of 1917 had a resounding impact, not only in the Middle East region, but also on the international scene. By exposing these secret agreements, the Bolsheviks sought to criticise the imperialism of the Western powers, particularly France and Britain, and to demonstrate their own commitment to the principles of self-determination and transparency. The Sykes-Picot agreements were not the beginning, but rather a culmination of the long process of the "Oriental Question", a complex diplomatic issue that had preoccupied European powers throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. This process concerned the management and sharing of influence over the territories of the declining Ottoman Empire, and the Sykes-Picot agreements were a decisive step in this process.

Under these agreements, a French zone of influence was established in Syria and Lebanon, while Britain gained control or influence over Iraq, Jordan and a region around Palestine. The intention was to create buffer zones between the spheres of influence of the great powers, including between the British and the Russians, who had competing interests in the region. This configuration was partly a response to the difficulty of cohabitation between these powers, as demonstrated by their competition in India and elsewhere. The publication of the Sykes-Picot agreements provoked a strong reaction in the Arab world, where they were seen as a betrayal of the promises made to Arab leaders during the war. This revelation exacerbated feelings of mistrust towards the Western powers and fuelled nationalist and anti-imperialist aspirations in the region. The impact of these agreements is still felt today, as they laid the foundations for the modern borders of the Middle East and the political dynamics that continue to influence the region.

The Armenian Genocide

Historical Background and the Beginning of the Genocide (1915-1917)

The First World War was a period of intense conflict and political upheaval, but it was also marked by one of the most tragic events of the early 20th century: the Armenian genocide. This genocide was perpetrated by the Young Turk government of the Ottoman Empire between 1915 and 1917, although acts of violence and deportation began before and continued after these dates.

During this tragic period, Ottoman Armenians, a minority Christian ethnic group in the Ottoman Empire, were systematically targeted by campaigns of forced deportations, mass executions, death marches and planned famines. The Ottoman authorities, using the war as a cover and pretext to resolve what they considered to be an "Armenian problem", orchestrated these actions with the aim of eliminating the Armenian population from Anatolia and other regions of the Empire. Estimates of the number of victims vary, but it is widely accepted that up to 1.5 million Armenians perished. The Armenian genocide has left a profound mark on the Armenian collective memory and has had a lasting impact on the global Armenian community. It is considered one of the first modern genocides and cast a shadow over Turkish-Armenian relations for more than a century.

Recognition of the Armenian genocide remains a sensitive and controversial issue. Many countries and international organisations have formally recognised the genocide, but certain debates and diplomatic tensions persist, particularly with Turkey, which disputes the characterisation of the events as genocide. The Armenian genocide has also had implications for international law, influencing the development of the notion of genocide and motivating efforts to prevent such atrocities in the future. This sombre event underlines the importance of historical memory and recognition of past injustices in building a common future based on understanding and reconciliation.

Armenia's historical roots

The Armenian people have a rich and ancient history, dating back to well before the Christian era. According to Armenian nationalist tradition and mythology, their roots go back as far as 200 BC, and even earlier. This is supported by archaeological and historical evidence showing that Armenians have occupied the Armenian plateau for millennia. Historic Armenia, often referred to as Upper Armenia or Greater Armenia, was located in an area that included parts of eastern modern Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, modern Iran and Iraq. This region was the birthplace of the kingdom of Urartu, considered to be a precursor of ancient Armenia, which flourished from the 9th to the 6th century BC. The kingdom of Armenia was formally established and recognised at the beginning of the 6th century BC, after the fall of Urartu and through integration into the Achaemenid Empire. It reached its apogee under the reign of Tigran the Great in the 1st century BC, when it briefly expanded to form an empire stretching from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean.

The historical depth of the Armenian presence in the region is also illustrated by the early adoption of Christianity as the state religion in 301 AD, making Armenia the first country to do so officially. Armenians have maintained a distinct cultural and religious identity throughout the centuries, despite invasions and the domination of various foreign empires. This long history has forged a strong national identity that has survived through the ages, even in the face of severe hardship such as the Armenian genocide in the early 20th century. Armenian mythological and historical accounts, although sometimes embellished in a nationalist spirit, are based on a real and significant history that has contributed to the cultural richness and resilience of the Armenian people.

Armenia, the first Christian state

Armenia holds the historic title of being the first kingdom to officially adopt Christianity as its state religion. This monumental event took place in 301 AD, during the reign of King Tiridates III, and was largely influenced by the missionary activity of Saint Gregory the Illuminator, who became the first head of the Armenian Church. The conversion of the Kingdom of Armenia to Christianity preceded that of the Roman Empire, which, under Emperor Constantine, began to adopt Christianity as its dominant religion after the Edict of Milan in 313 AD. The Armenian conversion was a significant process that profoundly influenced the cultural and national identity of the Armenian people. The adoption of Christianity led to the development of Armenian culture and religious art, including the unique architecture of Armenian churches and monasteries, as well as the creation of the Armenian alphabet by Saint Mesrop Mashtots in the early 5th century. This alphabet enabled Armenian literature to flourish, including the translation of the Bible and other important religious texts, thus helping to strengthen the Armenian Christian identity. Armenia's position as the first Christian state also had political and geopolitical implications, as it was often placed on the border of major competing empires and surrounded by non-Christian neighbours. This distinction has helped to shape Armenia's role and history over the centuries, making it an important player in the history of Christianity and in the regional history of the Middle East and the Caucasus.

Armenia's history after the adoption of Christianity as the state religion was complex and often tumultuous. After several centuries of conflict with neighbouring empires and periods of relative autonomy, the Armenians experienced a major change with the Arab conquests in the 7th century.

With the rapid spread of Islam following the death of the prophet Mohammed, Arab forces conquered vast swathes of the Middle East, including much of Armenia, around 640 AD. This period saw Armenia divided between Byzantine influence and the Arab caliphate, resulting in a cultural and political division of the Armenian region. During the period of Arab rule, and later under the Ottoman Empire, Armenians, as Christians, were generally classified as "dhimmis" - a protected but inferior category of non-Muslims under Islamic law. This status gave them a degree of protection and allowed them to practise their religion, but they were also subject to specific taxes and social and legal restrictions. The largest part of historic Armenia found itself caught between the Ottoman and Russian empires in the 19th and early 20th centuries. During this period, Armenians sought to preserve their cultural and religious identity, while facing increasing political challenges.

Under the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II (late 19th century), the Ottoman Empire adopted a pan-Islamist policy, seeking to unite the diverse Muslim peoples of the empire in response to the decline of Ottoman power and internal and external pressures. This policy often exacerbated ethnic and religious tensions within the Empire, leading to violence against Armenians and other non-Muslim groups. The Hamidian massacres of the late 19th century, in which tens of thousands of Armenians were killed, are a tragic example of the violence that preceded and foreshadowed the Armenian genocide of 1915. These events highlighted the difficulties faced by Armenians and other minorities in an empire seeking political and religious unity in the face of emerging nationalism and imperial decline.

The Treaty of San Stefano and the Congress of Berlin

The Treaty of San Stefano, signed in 1878, was a pivotal moment for the Armenian question, which became a matter of international concern. The treaty was concluded at the end of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, which saw a significant defeat for the Ottoman Empire at the hands of the Russian Empire. One of the most remarkable aspects of the Treaty of San Stefano was the clause requiring the Ottoman Empire to implement reforms in favour of the Christian populations, particularly the Armenians, and to improve their living conditions. This implicitly recognised the mistreatment that the Armenians had suffered and the need for international protection. However, implementation of the reforms promised in the treaty was largely ineffective. The Ottoman Empire, weakened by the war and internal pressures, was reluctant to grant concessions that might have been perceived as foreign interference in its internal affairs. In addition, the provisions of the Treaty of San Stefano were reworked later that year by the Congress of Berlin, which adjusted the terms of the treaty to accommodate the concerns of other major powers, notably Great Britain and Austria-Hungary.

The Congress of Berlin nevertheless kept up the pressure on the Ottoman Empire to reform, but in practice little was done to actually improve the situation of the Armenians. This lack of action, combined with political instability and growing ethnic tensions within the Empire, created an environment that eventually led to the Hamidian massacres of the 1890s and, later, the Armenian genocide of 1915. The internationalisation of the Armenian question by the Treaty of San Stefano thus marked the beginning of a period in which the European powers began to exert more direct influence over the affairs of the Ottoman Empire, often under the guise of protecting Christian minorities. However, the gap between promises of reform and their implementation left a legacy of unfulfilled commitments with tragic consequences for the Armenian people.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a period of great violence for the Armenian and Assyrian communities of the Ottoman Empire. In particular, the years 1895 and 1896 were marked by large-scale massacres, often referred to as the Hamidian massacres, named after Sultan Abdülhamid II. These massacres were carried out in response to Armenian protests against oppressive taxes, persecution and the lack of reforms promised by the Treaty of San Stefano. The Young Turks, a reformist nationalist movement that came to power after a coup in 1908, were initially seen as a source of hope for minorities in the Ottoman Empire. However, a radical faction of this movement ended up adopting an even more aggressive and nationalist policy than their predecessors. Convinced of the need to create a homogenous Turkish state, they saw Armenians and other non-Turkish minorities as obstacles to their national vision. Systematic discrimination against Armenians increased, fuelled by accusations of treason and collusion with the enemies of the Empire, notably Russia. This atmosphere of suspicion and hatred created the breeding ground for the genocide that began in 1915. One of the first acts of this genocidal campaign was the arrest and murder of Armenian intellectuals and leaders in Constantinople on 24 April 1915, a date that is now commemorated as the start of the Armenian genocide.

Mass deportations, death marches to the Syrian desert and massacres followed, with estimates of up to 1.5 million Armenians killed. In addition to the death marches, there are reports of Armenians being forced to board ships that were intentionally sunk in the Black Sea. In the face of these horrors, some Armenians converted to Islam to survive, while others went into hiding or were protected by sympathetic neighbours, including Kurds. At the same time, the Assyrian population also suffered similar atrocities between 1914 and 1920. As a millet, or autonomous community recognised by the Ottoman Empire, the Assyrians should have enjoyed some protection. However, in the context of the First World War and Turkish nationalism, they were the target of systematic extermination campaigns. These tragic events show how discrimination, dehumanisation and extremism can lead to acts of mass violence. The Armenian genocide and the massacres of the Assyrians are dark chapters in history that underline the importance of remembrance, recognition and prevention of genocide to ensure that such atrocities never happen again.

Towards the Republic of Turkey and the Denial of Genocide

The occupation of Istanbul by the Allies in 1919 and the establishment of a court martial to try those Ottoman officials responsible for the atrocities committed during the war marked an attempt to bring justice for the crimes committed, in particular the Armenian genocide. However, the situation in Anatolia remained unstable and complex. The nationalist movement in Turkey, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, grew rapidly in response to the terms of the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, which dismembered the Ottoman Empire and imposed severe sanctions on Turkey. The Kemalists rejected the treaty as a humiliation and a threat to Turkey's sovereignty and territorial integrity.

One of the sticking points was the question of the Greek Orthodox populations in Turkey, which were protected by the provisions of the treaty but were at stake in the Greek-Turkish conflict. Tensions between the Greek and Turkish communities led to large-scale violence and population exchanges, exacerbated by the war between Greece and Turkey from 1919 to 1922. Mustafa Kemal, who had been a prominent member of the Young Turks and gained fame as the defender of the Dardanelles during the First World War, is sometimes quoted as having described the Armenian genocide as a "shameful act". However, these claims are subject to controversy and historical debate. The official position of Kemal and the nascent Republic of Turkey on the genocide was to deny it and attribute it to wartime circumstances and civil unrest rather than to a deliberate policy of extermination.

During the resistance for Anatolia and the struggle to establish the Republic of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal and his supporters focused on building a unified Turkish nation-state, and any acknowledgement of past events that might have divided or weakened this national project was avoided. The period following the First World War was therefore marked by major political changes, attempts at post-conflict justice, and the emergence of new nation-states in the region, with the nascent Republic of Turkey seeking to define its own identity and politics independently of the Ottoman legacy.

The founding of Turkey

The Treaty of Lausanne and the New Political Reality (1923)

The Treaty of Lausanne, signed on 24 July 1923, marked a decisive turning point in the contemporary history of Turkey and the Middle East. After the failure of the Treaty of Sevres, mainly due to Turkish national resistance led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Allies were forced to renegotiate. Exhausted by the war and faced with the reality of a Turkey determined to defend its territorial integrity, the Allied powers had to recognise the new political reality established by the Turkish nationalists. The Treaty of Lausanne established the internationally recognised borders of the modern Republic of Turkey and cancelled the provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres, which had provided for the creation of a Kurdish state and recognised a certain degree of protection for the Armenians. By not including a provision for the creation of a Kurdistan or any measures for the Armenians, the Treaty of Lausanne closed the door on the "Kurdish question" and the "Armenian question" at international level, leaving these issues unresolved.

At the same time, the treaty formalised the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, which led to the "expulsion of Greeks from Turkish territories", a painful episode marked by the forced displacement of populations and the end of historic communities in Anatolia and Thrace. After the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, the Union and Progress Committee (CUP), better known as the Young Turks, which had been in power during the First World War, was officially dissolved. Several of its leaders went into exile, and some were assassinated in retaliation for their role in the Armenian genocide and the destructive policies of the war.