Qu'est-ce que l'économie politique internationale ?

Qu'est-ce que l'économie politique internationale ?

Qu'est-ce que l'économie politique internationale ? L'économie politique internationale se concentre sur la politique des phénomènes économiques qui transcendent les frontières des États, qu'il s'agisse de transactions commerciales, d'exportations, d'importations, de protectionnisme, de tarifs douaniers, de barrières non typologiques, de production, de la manière dont les multinationales opèrent au-delà des frontières des États et de la finance ; avec la finance, la manière dont l'argent et le capital peuvent traverser les frontières des États et aussi ; mais aussi le travail et la migration. Ces deux derniers aspects n'ont pas vraiment été couverts en détail par l'économie politique internationale.

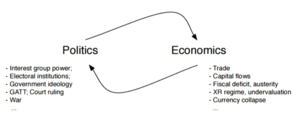

Ainsi, l'économie politique internationale examine l'interaction entre l'économie et la politique dans les différents États et le système international.[1] Elle examine les sources intérieures de la politique économique étrangère : pourquoi un État donné dans un système international donné poursuit l'ouverture, la fermeture, le protectionnisme, la libéralisation, etc. et qui sont les gagnants et les perdants de cette transaction de ces politiques. Ce sont les sources intérieures de la politique économique étrangère. Il y a aussi le système international des économies politiques intérieures. Donc, si depuis 2018, la tendance dominante est l'ouverture, a été à la suppression des obstacles à la libre circulation des investissements commerciaux et de l'argent, quelles sont les conséquences sur l'économie politique intérieure ? C'est le genre de questions qui se rapportent au terme international ou mondial dans l'économie politique internationale.

Politique. Pourquoi ? Parce qu'il ne s'agit pas seulement d'économie internationale et que c'est la principale spécificité de l'économie politique internationale. Parce que l'économie politique internationale introduit des variables politiques nationales et internationales pour comprendre les phénomènes économiques, elle le fait notamment en termes de politique de l'économie politique internationale. L'accent principal est mis sur la lutte entre les gagnants et les perdants de la mondialisation, ou les gagnants et les perdants d'une économie ou d'une politique étrangère particulière, ou d'une structure particulière de l'international du capitalisme mondial.

En outre, l'économie politique internationale étudie la dimension économique de la politique mondiale. Au début de la discipline, les chercheurs s'intéressaient surtout aux rivalités mondiales, aux rivalités entre les grandes puissances et à l'importance de l'économie dans la politique des grandes puissances. C'est toujours un problème, mais aujourd'hui il est beaucoup moins central qu'il ne l'était dans les années 1970.

"Économie" évidemment parce que l'économie politique internationale concerne surtout l'économie internationale, mais aussi parce que l'économie politique internationale s'inspire de théories économiques ou d'autres théories, car il existe diverses tendances dans l'économie politique internationale. Il y a des tendances basées sur les théories économiques néoclassiques ou dominantes. Il existe également des théories d'économie politique internationale qui sont marxistes, institutionnalistes, et qui se fondent donc sur l'économie institutionnalisée, et non sur l'économie néoclassique. L'idée est que les spécialistes internationaux de l'économie politique essaient de s'inspirer de la théorie économique pour construire des modèles utilisés pour prédire la manière dont les acteurs politiques se comportent, leurs préférences, leurs stratégies, etc. L'économie politique internationale s'appuie également sur l'histoire économique. L'économie politique internationale s'appuie également sur l'histoire économique. Beaucoup d'entre eux s'appuient sur les connaissances produites par les historiens de l'économie, principalement en ce qui concerne la période précédant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Par conséquent, l'"économie", en raison de ses principaux sujets, est constituée des résultats des processus et des politiques économiques.

La politique peut être à la fois nationale et internationale, en ce sens que pour déterminer la politique économique extérieure d'un État donné, il y a une lutte au sein de l'économie politique intérieure entre différents acteurs socio-économiques, entre différentes idéologies. Il existe également des institutions internationales telles que Accord général sur les tarifs douaniers et le commerce (GATT) ou l'Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC) qui influencent le fonctionnement de l'économie politique internationale et les processus d'interaction économique internationale ; mais aussi le Fonds monétaire international (FMI), la Banque mondiale (BM), les traités bilatéraux d'investissement ou les traités commerciaux bilatéraux, etc. Au début de la discipline des années 1970, on a également beaucoup parlé de la manière dont la politique de la guerre interagissait avec la politique de l'économie internationale.

Ce graphique montre les flux commerciaux, la manière dont les capitaux circulent, le volume des actifs détenus par les acteurs étrangers dans un pays donné et leur impact sur la politique internationale. Il montre également la façon dont les politiques nationales ont un impact sur le système politique international et sur des éléments tels que les régime des taux de change, la sous-évaluation ou la surévaluation des devises et les crises. Aucun de ces deux termes n'a de primauté politique ou économique. Il s'agit d'une interaction constante entre les deux. En économie politique internationale, on cherche donc à comprendre la direction générale dans laquelle les processus se développent et les résultats sont produits.

Objet

Si l'on considère le commerce, par exemple, pourquoi les États se lancent dans des guerres commerciales ou dans une coopération commerciale entre eux ? Et, lorsqu'ils le font, qui en profite et qui en perd les résultats ? Par exemple, pourquoi Trump s'est-il lancé dans une guerre commerciale avec la Chine et menace-t-il de le faire avec l'Union européenne ? Au cours de l'année dernière, l'administration Trump a augmenté les droits de douane sur les exportations chinoises vers les États-Unis. Certains experts ont été très critiques à l'égard de l'excédent commercial chinois avec les États-Unis et de l'excédent commercial allemand ou de la zone euro avec les États-Unis. Par extension, ils ont été très critiques à l'égard des politiques économiques intérieures que ces États, la zone euro et la Chine mènent, et de la manière dont ces politiques interagissent avec la politique intérieure américaine pour produire des déficits commerciaux pour les États-Unis.

Qui pousse donc Trump à faire cela ? Y a-t-il quelqu'un qui pousse Trump à faire cela ? Qui sera gagnant avec les droits de douane de Trump, qui sera perdant avec les droits de douane de Trump et dans quelles conditions Trump inverserait la guerre commerciale dans laquelle il s'est engagé avec la Chine et l'Union européenne et poursuivrait la coopération en matière commerciale avec ces États ?

Une question similaire est de savoir ce qui explique le nationalisme économique intérieur des années 20 et 30, le fait que dans les années 20 et plus encore dans les années 30, les États ont augmenté les droits de douane et levé des barrières commerciales les uns avec les autres, se sont repliés sur eux-mêmes, ce qui a entraîné un effondrement des volumes commerciaux. Ce qui explique cela et encore une fois qui a gagné et qui a perdu, qui s'est opposé et qui a favorisé. Et pourquoi, à ce moment précis, cette politique a-t-elle été menée par un bon nombre d'États. Et pourquoi est-ce qu'après 1945, après la guerre, c'est l'inverse qui s'est produit ? La même question se pose à nouveau : qui profite, quels groupes internes dans quels États profitent de la mise en place de ces institutions et de cette coopération ?

Si nous examinons maintenant les investissements ou les sociétés multinationales, la question est de savoir comment les activités des sociétés multinationales affectent les relations entre les États. Alors, qu'est-ce qui explique le conflit entre la Chine et les investissements directs étrangers (IDE) aux États-Unis ? Par exemple, il y a le cas de Huawei, un fournisseur mondial d'infrastructures et d'appareils intelligents dans le domaine des technologies de l'information et de la communication (TIC), qui participe au développement de la technologie 5G.[2][3] Les États-Unis ont bloqué les investissements de Huawei aux États-Unis et font pression sur l'Union européenne pour qu'elle bloque les investissements de Huawei, et pas seulement les investissements, mais aussi la participation de Huawei à des projets menés dans l'Union européenne.[4][5][6][7] Ce qui explique le fait que President Macron maintenant, et l'Allemagne aussi, poussent à l'idée que l'Union européenne devrait mettre en place un organisme pour filtrer les investissements chinois dans l'Union européenne et dire quels investissements seront autorisés et quels investissements ne le seront pas.[8][9] C'est un cas nouveau en termes d'investissements internationaux car les États-Unis et l'Union européenne étaient jusqu'à présent les sources des investissements internationaux.[10][11][12][13][14]

Une question typique portait sur la relation des investissements internationaux avant la Seconde Guerre mondiale dans le cadre du colonialisme, et sur le schéma des relations d'investissement à cette époque. Les deux tiers du globe étaient directement administrés par l'Empire britannique, l'Empire français, l'Empire portugais. Ce qui explique le fait que les États-Unis n'étaient pas, à l'exception des Philippines, une puissance coloniale et n'ont pas tenté de le devenir après les années 1930.

Et quelle est la différence entre ce colonialisme et la chaîne de valeur globale (CVG) aujourd'hui dans un monde ? Quelle est la relation entre les chaînes de valeur mondiales, donc la façon dont les multinationales opèrent aujourd'hui, et les investissements commerciaux régionaux accords et blocs ? Y a-t-il un rapport entre la façon dont les investissements internationaux ont lieu aujourd'hui et la mise en place de Mercosur, Accord de libre-échange nord-américain (ALENA), Association des nations de l'Asie du Sud-Est (ANASE) dans la région de l'Asie du Sud-Est, les traités bilatéraux d'investissement conclus par le Japon ; y a-t-il un rapport entre les investissements de la Russie dans le cadre de l'Union européenne ? L'économie politique internationale traite ce genre de questions.

Nous nous intéressons davantage aux pays qui sont une destination pour les investissements directs étrangers, au type de relations que les pays en développement développent en vue de ces investissements. Il y a eu une période, par exemple, entre les années 20 et les années 70, où les États en développement ont essayé d'empêcher les investissements directs étrangers, les sociétés multinationales. Et, depuis la fin et le milieu des années 1970, il y a une compétition pour attirer les capitaux, pour attirer les sociétés internationales.[15] So what explains that change in policy?

Une question typique en termes de système monétaire international et de régime des taux de change est de savoir pourquoi c'est la Chine et l'Union européenne qui veulent aujourd'hui réformer le système monétaire international.[16][17]Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England stated in August 2019 that there should be a new international monetary system that is not dependent on the dollar, while the Chinese central bank has asked the same for the last 15 years.[18][19] Pourquoi les systèmes monétaires internationaux précédents, tels que l'étalon-or et le système de Bretton Woods, se sont effondrés et qui en a profité et qui en a perdu. Aussi, pourquoi President Trump a-t-il attaqué la Banque centrale européenne en septembre 2019 ?[20][21][22]

Si nous examinons toutes ces choses, la production du commerce international, la finance, quel est leur impact sur les systèmes de protection sociale et la politique intérieure ? Si vous regardez l'histoire de cette question dans les années 1920 et 1930, il y a eu des affrontements entre la montée du syndicalisme et du socialisme dans les pays avancés et l'étalon-or. Qu'est-ce qui explique cela et comment ce conflit s'est déroulé historiquement ; pourquoi le populisme de droite comme Trump aujourd'hui ou comme Marine Le Pen en France ou d'autres forces attaquent la mondialisation et parlent de nationalisme économique ?

Une autre question typique est la suivante : le capital de la libéralisation financière conduit-il à une course vers le bas en termes de politiques fiscales, de sorte que les États se font concurrence pour attirer les investissements en abaissant leurs impôts, ou bien stimule-t-il une plus grande demande de protection sociale pour protéger les segments de la population nationale qui sont perdants dans le processus de libéralisation.

Quelques observations sur l'économie politique internationale

Les spécialistes de la politique internationale ont fait trois distinctions thématiques : le commerce international, la production internationale et la finance internationale. Néanmoins, il en existe une quatrième, qui est celle du travail et de la migration car, bien sûr, la façon dont le travail est organisé et la façon dont il se déplace à travers les frontières des États sont les principaux enjeux de la politique internationale. Cette question a été encore plus déterminante dans le passé qu'elle ne l'est aujourd'hui. L'accent thématique est inégal.

Il y a aussi une approche historique inégale en termes de la façon dont l'économie politique internationale étudie le capitalisme mondial. C'est probablement parce que l'économie politique internationale est aujourd'hui menée par les sciences politiques et est considérée comme un sous-domaine des sciences politiques, du moins dans l'école américaine. Les politologues se concentrent principalement sur la période qui a suivi la première guerre mondiale et en particulier sur l'étape contemporaine de la seconde mondialisation qui a commencé dans les années 1970. Ainsi, ils s'intéressent surtout au développement contemporain alors que la période précédant la Seconde Guerre mondiale est surtout étudiée par les historiens, bien que certains des plus grands spécialistes de l'économie politique internationale aient également produit des études sur la période précédant la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Brève histoire de l'économie politique internationale

Préhistoire

Origine et signification de l'économie politique internationale

La discipline est née dans les années 1970, mais bien sûr, les chercheurs en sciences sociales qui étudient le fonctionnement du capitalisme mondial n'ont pas attendu les années 1970. Des études sur le fonctionnement de l'économie politique internationale du capitalisme mondial ont été réalisées dès le début du capitalisme mondial lui-même.

L'expression "économie politique" est apparue pour la première fois en France en 1615 avec le célèbre livre de Antoine de Montchrétien, "Traicté de l'Œconomie Politique". Bien qu'Antoine de Montchrétien soit traditionnellement considéré comme l'un des premiers à utiliser ce terme dans le sens précité[23][24], Grégoire King, historien de l'économie, indique pour sa part que le premier à utiliser l'expression "économie politique" serait Louis Turquet de Mayerne en 1616 dans son livre La monarchie aristodémocratique, ou Le gouvernement composé et meslé des trois formes de légitimes républiques.[25][26] Plus tard, dans le "Discours sur l'oeconomie politique" publié en 1755, Jean-Jacques Rousseau donne la définition suivante de l'économie politique : "le mot vient de oeconomie (οἰκονομία) et signifie à l'origine uniquement le gouvernement sage et légitime de la maison, pour le bien commun de toute la famille. La signification de ce terme a été étendue par la suite au gouvernement de la grande famille qu'est l'État. Pour distinguer ces deux sens, on l'appelle dans ce dernier cas, économie générale ou politique ; et dans l'autre cas, économie domestique ou particulière. Seul le premier cas est traité dans le présent article".[27] Au XIXe siècle, le terme "économie politique" a été défini par Charles Gide dans son livre Principes d'économie politique comme "l'étude de la production économique, de l'offre et de la demande de biens et de services et de leur relation avec les lois et les coutumes ; le gouvernement, la distribution des richesses et la richesse des nations, y compris le budget".[28] Le terme est resté et puis, à la fin du XIXe siècle, les écrivains classiques et les économistes politiques sont arrivés.

Pourquoi l'économie politique ? À l'origine, l'économie politique signifiait l'étude des conditions dans lesquelles la production ou la consommation dans des paramètres limités était organisée dans les États-nations. Ainsi, l'économie politique a élargi le champ de l'économie, qui vient du grec oikos (signifiant "maison") et nomos (signifiant "loi" ou "ordre"). L'économie politique était donc censée exprimer les lois de la production de richesses au niveau de l'État, tout comme l'économie était l'ordre du foyer. Cela renvoie à l'aspect économique des choses et au politique.[29]

Il est essentiel de comprendre que pour les auteurs, jusqu'à la fin du XIXe siècle, il n'y avait pas de distinction claire, du moins entre la politique et l'économie. Il fallait comprendre deux dimensions d'une même question, à savoir la façon dont l'ordre social évoluait, sa dynamique interne et les enjeux qu'il traversait.

L'économie politique classique

Les principaux auteurs de l'économie politique classique, du moins aujourd'hui, sont Adam Smith qui a écrit Recherches sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations publié en 1776.[30][31] Il y a aussi David Ricardo, qui était un banquier anglais à Londres et qui a développé le théorie de l'avantage comparatif dans son livre Des principes de l'économie politique et de l'impôt publié en 1817 qui est devenu le concept clé de la théorie du commerce international et de l'économie internationale.[32] John Stuart Mill était un philosophe libéral anglais plus tard dans les années 1840, 1850, 1860 et a publié en 1848 son livre Principles of Political Economy, un des plus importants manuels d'économie et d'économie politique du milieu du XIXe siècle.[33] Friedrich List était un économiste historique prussien germanophone dans les années 1840 et 1850. Il a écrit un livre intitulé Système national d'économie politique) (Das Nationale System der Politischen Ökonomie) publié en 1841, dans lequel il a développé le "système national" d'économie politique.[34][35][36][37] Alexander Hamilton, le premier secrétaire au Trésor des États-Unis, était un homme politique et a produit quelques rapports pour la première république américaine qui comprenaient certaines des déclarations les plus célèbres sur la politique mercantiliste et qui est assez proche de Frederic List. Hamilton a été dépeint comme le "saint patron" de l'école américaine de philosophie économique qui, selon un historien, a dominé la politique économique après 1861.[38] Il s'oppose aux idées britanniques de libre-échange, qui, selon lui, faussent les bénéfices des puissances coloniales et impériales, en faveur du protectionnisme, qui, selon lui, contribuerait à développer l'économie émergente de la nation en plein essor.

L'économie politique classique était pré-disciplinaire. Qu'est-ce que cela signifie ? C'était une science sociale totale qui n'était pas divisée en disciplines distinctes, des disciplines de sciences sociales, ce qui est la façon dont l'académie et la recherche contemporaines sont organisées. Ces auteurs s'occupaient de tout : le mouvement des prix, le droit, l'éthique ; ils essayaient de fusionner toutes ces questions en un seul système de philosophie politique. Pour Cohen, dans le manuel International Political Economy : An Intellectual History", publié en 2008, "tous ont compris que leur sujet était ce qu'on appelle l'économie politique, une science sociale unifiée étroitement liée à l'étude de la philosophie morale".[39]

The Marginalist Revolution and Neoclassical economics

Why has this stopped in the 19th century? It happened in the 1870s with the so-called Marginalist Revolution that has given rise to classic neoclassical economics.[40] Neoclassical economics is today the dominant approach to the study of economic.

The neoclassicals and the marginalists are, obviously, liberals. So there is a continuity between the liberal classical political economists and the marginalists. But, in terms of method and approach to the subject matter, there is a break, following a fundamental revolution taking place in the 1870s.

In terms of what is of interest to us, it has to do with the way the marginalists claimed that political economy should be broken up into politics on the one hand, and economics on the other hand. They postulate that political economy should be replaced by economics and the study of the way the economy works. They attempt to determine the laws that govern economic activity, and it should be modeled on the physical sciences, and the link to political considerations should be severed.

Marginalism as a formal theory can be attributed to the work of three economists, Jevons in England, Menger in Austria, and Walras in Switzerland. William Stanley Jevons first proposed the theory in articles in 1863 and 1871.[41] Similarly, Carl Menger presented the theory in 1871.[42] Menger explained why individuals use marginal utility to decide amongst trade-offs. Still, while his illustrative examples present utility as quantified, his essential assumptions do not. Léon Walras introduced the theory in Éléments d'économie politique pure, the first part of which was published in 1874.[43]

Of course, the discipline became much more normative in the sense that if an economist were to study the way the economy works, the primary issued would be what the best policy to follow according to the way the economy works is?

In 1890 Alfred Marshall, one of the most influential English liberal economist in Cambridge and the late 19th century early 20th published a key textbook in 1980 called Principles of Economics while the main textbook so far was Principles of Political Economy written by Mill.[44] From that point onwards, the disciplinary separation of the social sciences in academia ensued. There was sociology which is an empirical discipline developed by authors who went on workplaces, who went to look at the way family work, how the family structures worked and developed an empirically based discipline. There were the political scientists who looked mostly at the way political institutions and constitutional issues worked, and they were closer to constitutional law than political economy. And then, there were the economists, who started from axiomatic postulates and attempted to understand based on theoretical hypothesis.

Marxism, Leninism and dependency theory

There was also the discipline of international relations that developed sometime in the early 20th century. The field of international relations was preoccupied with high politics. It was in close relation to the study of geopolitics from the 19th century, and it mostly dealt with diplomacy, war and security. International relations did not look at the way economic relations between states took place because it was considered a low politics. With international relations, there was something related to high contexts.

From the late 19th century, the idea that political economy does not distinguish between the political and the economic disappeared. Of course, it does not entirely disappear because some counter-tendencies and exceptions remained influential even after the Marginalist Revolution.

The first obvious exception is the Marxists with the project to continue the work of Karl Marx on the capital. Marxists authors produced a theory on the way capitalism works as a total social reality and not just as an economic system but as a social order in and of itself. Marx's critical theories about society, economics and politics – collectively understood as Marxism – hold that human societies develop through class struggle. In capitalism, this manifests itself in the conflict between the ruling classes (known as the bourgeoisie) that control the means of production and the working classes (known as the proletariat) that enable these means by selling their labour-power in return for wages.[45][46] Marxism has had a profound impact on global academia and has influenced many fields.[47][48][49][50] The term political economy initially referred to the study of the material conditions of economic production in the capitalist system. In Marxism, political economy is the study of the means of production, specifically of capital and how that manifests as economic activity.[46]

In the Marxist tradition, we can notably cite two key authors. There is Rudolf Hilferding who wrote Finance Capital in 1910[51][52], and Rosa Luxemburg, who wrote The Accumulation of Capital, first published in 1913, a book about imperialism within which she argues that capitalism needs to constantly expand into noncapitalist areas to access new supply sources, markets for surplus-value, and reservoirs of labor.[53][54]

There is also Lenin who published in September 1917 his book Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. Drawing on the economic literature available to him in Zurich and drawing on the works of John Atkinson Hobson and Rudolf Hilferding on imperialism, Lenin sets out his views on the recent transformations of capitalism and their political consequences in the context of the First World War.[55] He argues that imperialism was a product of monopoly capitalism, as capitalists sought to increase their profits by extending into new territories where wages were lower and raw materials cheaper[56][57] with imperialism, the highest (advanced) stage of capitalism, requiring monopolies (of labour and natural-resource exploitation) and the exportation of finance capital (rather than goods) to sustain colonialism, which is an integral function of said economic model.[58][59] Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism became a standard textbook and propelled Lenin has a central figure in the debate about imperialism. Therefore, for the Marxists, imperialism is a structural feature of capitalism.

After the war, Marxist theory, to some extent, became subsumed under anti-colonial preoccupations and gave rise to the dependency theory. Dependency theory was derived from Listian and Hamiltonian approaches to political economy. This theory was officially developed in the late 1960s following World War II, as scholars searched for the root issue in the lack of development in Latin America.[60] Dependency theory is, therefore, a Latin American phenomenon mostly because Latin America was the first segment of the old colonial world that became independent in the 19th century and so, theoretically, also was in the vanguard of the anti-colonial struggle.[61] For the dependency theory, these countries are integrated but are structurally placed in a state of continuous dependency by applying, for example, a ban on domestic production of products to be purchased from colonial companies. For André Gunder Frank, the dependence of the countries of the South can be explained historically by colonization (Asia, Africa, Latin America for example) and by unequal trade (by companies such as the Dutch East India Company or the English East India Company). For the Argentinean economist Raúl Prebisch, the wealth of rich countries is inversely proportional to that of poor countries. For dependency theorists, it is currently impossible for the countries of the South to develop without freeing themselves from the ties of dependency maintained with the North since the development of the countries of the North is based on the underdevelopment of those of the South. [62]

So Marxism and dependency theory were one major exception to the way the study of economics and politics was organized in academia after the marginalist revolution.

Institutional economics

There is also the institutional economics tendency in the United States focusing on understanding the role of the evolutionary process and the role of institutions in shaping economic behavior.[63] Institutional economics emphasizes a broader study of institutions and views markets as a result of the complex interaction of these various institutions (e.g. individuals, firms, states, social norms).[64]

The foundations of this approach were laid by Thorstein Veblen who wrote strings of books in the early 20th century (The Theory of the Leisure Class, 1899, The Theory of Business Enterprise, 1904), and gave rise to what is today institutional economics whose most recent notorious exponent was Douglass North. Veblen was a radical figure and is referred to as belonging to as the Progressive Era, while the late 19th century were the years of populism. As much as Veblen was an economist, he was also a sociologist who rejected his contemporaries who looked at the economy as an autonomous, stable, and static entity. Veblen disagreed with his peers, as he strongly believed that the economy was significantly embedded in social institutions.[65][66]

Veblen was very much at the theoretical exponent of those developments. His most famous book is The Theory of the Leisure Class published in 1899 wherein he developed a social critique of conspicuous consumption, as a function of social class and of consumerism, derived from the social stratification of people and the division of labour, which are social institutions of the feudal period (9th–15th c.) that have continued to the modern era.[67]

Karl Polanyi develops an institutionalist conception of the institution. Because the market economy has failed to deliver on its promise of social harmony, because it has led to the social question, it has been necessary to regulate it and promote institutions that can counteract its destructive effects.[68][69] Karl Polanyi was an anthropologist who wrote a major work published in 1944 titled The Great Transformation which has a canonical status today in the discipline. It is a major work about how the classical liberal era of the late 19th century-early 20th century broke down in the interwar years. In this book, Polanyi deals with the social and political upheavals that took place in England during the rise of the market economy. He contends that the modern market economy and the modern nation-state should be understood not as discrete elements but as the single human invention he calls the "Market Society".[70] Polanyi being an anthropologist, did not share the premises of neoclassical economics and so produced works that were distinct from the work produced by the economists.[71]

Albert Hirschmann wrote canonical books in political science about how change happens in organizations published in 1970 titled Exit, Voice, and Loyalty.[72][73] By understanding the relationship between exit and voice, and the interplay that loyalty has with these choices, organizations can craft the means to better address their members' concerns and issues, and thereby effect improvement. Failure to understand these competing pressures can lead to organizational decline and possible failure.[74] He is very much an essential figure in institutional economics, in organization theory, in the international political economy today.[75][76][77]

Ernst Hass was a political scientist who wrote an early major work on European integration in the 1950s and then developed regional integration theory. He looked at the processes of economic integration notably in his book The Uniting of Europe published in 1958[78][79][80][81][82] and article International Integration: The European and the Universal Process published in 1961.[83] Ernst Haas has therefore made important contributions to theoretical discussions related to international relations and European integration. In this regard, he is the founder of neo-functionalism as an approach to the study of integration.[84]

Karl Deutsch wrote a significant study of the way political integration takes place in the 1950s.[85] Karl Deutsch studies integration processes with the broader context of international relations. He argues that international integration is a process implying the concomitant convergence of states and societies resulting in a process of intensive communication giving birth to the emergence of ‘community feeling' and therefore to the set up of institutions and regulated practices to ensure long-term peaceful interactions.[63] This analytical framework is first developed in Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience published in 1957[86][87][88][89] and later in The Analysis of International Relations published in 1978.[90]

Karl Deutsch and Ernst Hass are neo-functionalist theorists of the European integration and will later inspire notably Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye who will found the international relations theory of neoliberalism, developed in their book Power and Interdependence published in 1977.[91][92][93][94]

Then there is one major exception with John Maynard Keynes, who was an economist, and a policymaker. Keynes developed the premises of what later became Keynesianism, which is a revised version of neoclassical economics in particular about the way the macroeconomy works. His ideas will fundamentally change the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. For Keynesians, markets left to their own do not necessarily lead to the economic optimum. Therefore, the state has a role to play in the economic field, particularly in a framework of recovery policy.

Keynes spent a lot of his energy in the 1920s writing political tracts attacking the policies that were pursued by the major powers in Versailles and then their domestic and foreign economic policies. He will notably publish A Revision of the Treaty in 1922 to advocate a reduction of German reparations and in A Tract on Monetary Reform published in 1823 he denounces the post-World War I deflation policies.[95] He was the first in the 1920s to say that the structures of the classical era should not be reproduced because there were shifts in domestic political economies notably arguing against a return to the gold standard at parity as it ran counter to the need for domestic policy autonomy.

Alongside Keynes, there is Jacob Viner who was a Canadian economist in the US Treasury Department during the administration of Franklin Roosevelt, and Charles Kindleberger, an economic historian known for the hegemonic stability theory and who started his career as an advisor to the US Treasury in the 1940s. Viner is one of the pioneers of theory of the firm, and was the first to distinguish between short-term and long-term cost curves in the article Cost curves and supply curves published in 1932.[96] He was also a notorious opponent of John Maynard Keynes during the Great Depression. For him, Keynes's analysis was containing omissions and would not stand in the long run. As to Kindleberger, is one of the major administrators of the Marshall Plan, the plan that the United States came up with to reconstruct Western Europe after the Second World War. He served as the Acting Director of the Office of Economic Security Policy at the Department of State between 1945 and 1947. Kindleberger is a significant figure in early international political because he wrote the classical analysis of why global capitalism broke down in the 1930s in The World in Depression 1929–1939[97] and Manias, Panics, and Crashes which is the account of the way money and credit mismanagement has contributed to financial crises over centuries.[98][99][100] He is also known as the father to the hegemonic stability theory which is the first major global theory in international political theory that structured the debate. The key idea is that in order for a global economic and political system to work well, there must be a hegemonic power capable of making the necessary decisions to regulate the economy. Therefore, the collapse of an existing hegemon or the state of no hegemon destabilize the international system.[101][102]

Birth of the discipline of International Political Economy

Why was international political economy born in the early 1970s? The first thing is the historical context of the early seventies and how international politics influenced international economy of that time. The economic life of the 1970s was greatly affected by continuously unstable dynamics which resulted in structural changes of the capitalist world economy and notably a change in the dominant policy stance from Keynesianism to neo-conservative monetarism.[103]

The dollar crisis of 1968-1971 and the decision of President Richard Nixon to terminate the convertibility of gold on 15 August 1971 that had been established under the IMF caused the end of the Bretton Woods system.[104][105] A dollar standard was then created in December 1971 with the Smithsonian Agreement whereby the currencies of a number of Western countries were fasten to the US dollar.[106][107][108][109] The oil crises of 1973 and 1979 resulted in the West to more restrictive monetary policy to better fight inflation. In the 1970s, the so-called Japanese economic miracle took place making Japan a major trading nation and industrial competitors for Western countries. Between 1946 and 1976, Japan sustained economic growth by 55 fold while its exportation known a truly phenomenal growth.[110][111] The movement of exchange rates also increased considerably in the early part of the post-Bretton Woods era.[112][113][114] For smaller or more outward-looking economies, the floating exchange rate is disruptive. The same is true for developing countries that are concerned about the floating exchange rate for the stability of their economies. With the transition to the floating exchange rate, some countries of the world and especially countries that claim to compete for the dominance of the international financial market are liberalizing their international capital transactions. The most important changes are taking place in the United States, which is trying to regain ground following the abolition of capital controls and is committed to the liberalisation of the financial sector. For other countries, we see a "back and forth" during the 1970s even with regard to capital flow controls, not to mention the liberalization of their financial sector.[115]

That context led scholars in the fields of economic, political science and economic history to attempt to bridge the gap between international politics and international economics. They saw themselves as intellectual entrepreneurs who wanted to create something new.

The discipline was born independently at the same time both in the United Kingdom and the United States. Of course, the developments in the United States are more relevant and also the course here at the University of Geneva is much more aligned on development in the American trends of international political economy.

In the United States, two scholars played a central role in the development of the discipline. Those were Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, the author who notably coined the term soft power in the late 1980s. They were political scientists who were influenced by the functionalists and co-founded the international relations theory of neoliberalism, developed in their 1977 book Power and Interdependence.[116] In the early 1970s, they took over the journal peer-reviewed academic journal International Organization and shifted away its focus from the study of international organizations to the study of international political economy.[117][118] They organized two key conferences, and specifically, that dealt with world politics and the concept of interdependence. After 1975, International Organization becomes the main outlet for international political economy in the United States.[119] From then onward, international political economy is more or less identified with the journal to the extent that some people refer to as the American School as the International Organization School.[120]

Pretty much at the same time, Susan Strange, who was a professor of international relations in the London School of Economics, played a central role in developing international political economy as a field of study in Britain.[121] She notably published in 1970 the article International Economics and International Relations: A Case of Mutual Neglec which was a kind of manifesto calling for international economists and international political scientists to work together and to try and bridge the gap between international economics (IE) and international relations (IR).[122] According to her, scholars from both traditions were neglecting fundamental changes in the world economy arguing that a more modern approach to the study of the global economy was needed. Therefore, for Strange, international political economic was 'middle ground' between economic and political analysis of international affairs.[123]

Evolution: American school vs British school

How those two schools developed? In International political economy: a tale of two heterodoxies published in 2001, Murphy and Nelson refer to the development of the international political economy as a tale of two heterodoxies divided into American and British schools.[124] Why heterodoxy? Because international was heterodox in relation, both to mainstream economic and to mainstream political science.[125]

In reccent years, the American international political economy has tried to mimic the methods of mainstream economics. This comes most of the time in form of using quantitative or statistical methods in order to allow for law-like generalizations. There are very broad divergences in the sense that American international political economy is very much state-centric, privileging sovereign governments above all other units of interest and conceiving of itself as a branch of international relations while British School by contrast, treats the state as just one agent among many.[126] Actors are not driven by norms or ideas but essentially by material interests. As a consequence, different actors pursue different goals. To summarize, the American school analyze actors as rational and goal-oriented, adopting a utility-maximizing behavior and thus self-interested individuals. Therefore, international political economy is considered as the political economy of international relations in the United States. It is state-centric with the main preoccupation to determine how states behave in terms of international economics. American international political economy is suspicious of normative judgements. It is more preoccupied with explaining how the system works rather than with criticizing the way the system works and prescribing alternative ways in which the system should work. It has tried since the mid-1980s more or less to mimic the positivist and quantitative bias that is a methodological hallmark of mainstream political science in particular mainstream economics, and neoclassical economics.

In The Transatlantic Divide: Why Are American and British IPE so Different? and The transatlantic divide: a rejoinder Benjamin Cohen who was one of the major characters in developments of international political economy from the early 1970s, he explained this by saying that it is because, from the mid-1980s, international political economy authors wanted to enjoy the same kind of prestige.[127][128] So they try to mimic their methods their methodologies in order to advance their careers.

British international political economy is the opposite on pretty much every score.[129] British international political economy refers to itself as the global political economy, to begin with, and not the international political economy most of the time. Again because global and not international because it is not state-centre. It is very much preoccupied with the erosion, the place that the state occupies within the international system and the rise of importance of non-state actors in the international system works.

British international political economy is also the home for contemporaries. British international political economy is a broad church in terms of methods and terms of schools of thoughts. It is methodologically and thematically eclectic, and it looks at all kinds of issues with our drawing limits. For British School, the approach is more interpretative and critical. The different trends reject the positivist assumption that the purpose of social science is to identify causal relationships in an objective world. They seek in the wider range of approaches in the field of social science for alternative theories and explanations (e.g., historical sociology structuralism and poststructuralism, feminism, cultural studies, etc).[130] British School approaches have produced a more profound toolkit to analyze international political economy.[131] If in the United States, international political economy has been mostly seen as a sub-specialty of the study of the field of International Relations, British international political economy does not consider itself as a branch of international relations. Thus, in many places in the United Kingdom, international political economy is stored into departments that do not teach international relations. Moreover, the British international political economy has a much more ambitious agenda in the sense that it introduced the concept of globalization but also approaches such environmental culture and feminist political economy.

Old vs New International Political Economy

American international political economy can be split up into the old and the new international political economy.[132][133] The old international political economy based itself on methodologically loose attempts and holistic understandings of the international political economy. From that, the old international political economy of the 1970s gradually moved towards a more positivist and behavioralist direction. From the mid-1980s, international political economy became mainly concerned with positivist explorations of the individual dimensions of the system or with what some authors refer to as Mertonian middle-range theory.[134] There is also a shift from qualitative to quantitative methodologies.

The primary debate in the old international political economy was the debate about complex interdependence, hegemonic stability theory and hegemonic decline. There was a major debate about whether the United States was in hegemonic decline in the late 1970s and 1980s, and another one about international organizations and the governance of the global system. The main focus of the discipline was the international level.

The main aspects of the new international political economy focus on the domestic sources of foreign economic policy. In contrast, the new international political economy attempts to determine the relationships between key individuals, political, and economic variables in the system. It is a more-integrated type of analysis, which explicitly sought to trace the connections between political and economic factors.[135]

Keohane, who was the founder of the old international political economy, in the article The old IPE and the new. Review of International Political Economy published in 2019, sustained attention to issues of structural power and the synthetic interpretation of change.[136] There are debates within the American international political economy itself about which direction the discipline should take.

Open economy politics is the name given by contemporary practitioners of American international political economy to their approach.[137] It adopts the assumptions of neoclassical economics and international trade theory.[138] The main idea is that today international political economy tries to determine the relationships between three distinct variables, namely domestic interests, domestic and international institutions, and international bargaining between states. For contemporaries, the combination of those three variables determined the way the international political economy functions.

The key protagonist in the old international political economy was Robert Keohane, a political scientist and neoliberal institutionalist. There is also Stephen Krasner a neorealist academic who focused on international regimes, and he is a leading figure in the study of Regime theory. Peter Katzenstein was credited with introducing the issues of domestic variables and ideational variables into the study of international political economy in the early 1980s.[139] For him, until the end of the 1970s, the litterature on foreign economic policy has discounted the influence of domestic forces.[140][141] For Katzenstein, international and domestic factors have been closely intertwined in the historical evolution of the international political economy since the middle of the XIXth century. He argues that the domestic structure of the national state is an essential explanatory variable of the interrelation between international interdependence and political structure.[142] There is Charles Kindleberger and also Robert Gilpin who wrote a string of books that became classic.

Americans are almost exclusively in international relations, and most come from Ivy League universities. Furthermore, it is mainly a group of people associated with a legit university in the United States. Those academics are close to policymaking circles as well, whereas actors in the British international political economy come from different horizons. Two institutions are particularly important in the field of international political economy: one is the London School of Economics of course, and the other one is the University of Warwick. It should be highlighted that there are also the Canadians who try to bridge the gap between the Americans the British.[143] International political economy in Canada is defined by its pluralism with several Canadian academics keeping a foot in each camp drawing from the American school's emphasise on scientific positivism and empiricism, and the British school-style historicism.[144] The Canadian approach is based on eclecticism combining rigorous observational studies and theoretically informed analyzes with a keen appreciation of the positions of history, institutions and ideas.

Annexes

- “International Monetary Fund.” International Organization, vol. 1, no. 1, 1947, pp. 124–125. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2703527.

Références

- ↑ Veseth, Michael. "What is international political economy." (2002).

- ↑ Kerstein, R. (2019). 5G is here… Hip, hip, Huawei! The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 101(6), 236–237. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsbull.2019.236

- ↑ Balding, Christopher and Clarke, Donald C., Who Owns Huawei? (April 17, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3372669 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3372669

- ↑ Walker, Tony. “Why the Global Battle over Huawei Could Prove More Disruptive than Trump's Trade War with China.” The Conversation, 21 Feb. 2020

- ↑ Lyu, Mengting, and Chia-yi Lee. "RSIS-WTO Parliamentary Workshop–US Blacklist on Huawei: Leverage for the US-China Trade Talks?." (2019).

- ↑ “The Trade War, Huawei and Chinese Strategy.” EIAS.

- ↑ Harrell, Peter E. “The U.S.-Chinese Trade War Just Entered Phase 2.” Foreign Policy, 27 Dec. 2019.

- ↑ Rose, Michel. “In China, Macron Presses EU for United Front on Foreign Takeovers.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 10 Jan. 2018.

- ↑ Brattberg, Erik, and Philippe Le Corre. “The EU and China in 2020: More Competition Ahead.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ↑ Sauvant, K. P., & Nolan, M. D. (2015). China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment and International Investment Law. Journal of International Economic Law, jgv045. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgv045

- ↑ Bailliu, J., Kruger, M., Toktamyssov, A., & Welbourn, W. (2017). How fast can China grow? The Middle Kingdom’s prospects to 2030. Pacific Economic Review, 24(2), 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0106.12240

- ↑ Buckley, P. (2019), "China goes global: provenance, projection, performance and policy", International Journal of Emerging Markets, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 6-23. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-01-2017-0006

- ↑ Schnabl, G. (2019). China’s Overinvestment and International Trade Conflicts. China & World Economy, 27(5), 37–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12293

- ↑ Baláž, Peter, Stanislav Zábojník, and Lukáš Harvánek. "The Growing Importance of China in the Global Trade." China's Expansion in International Business. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020. 97-160.

- ↑ Vukšić, G. (2013). Developing countries in competition for foreign investment. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 22(3), 351–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2011.578751

- ↑ Otero-Iglesias, M., & Zhang, M. (2013). EU-China Collaboration in the Reform of the International Monetary System: Much Ado About Nothing? The World Economy, 37(1), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12131

- ↑ Otero‐Iglesias, Miguel, and Ming Zhang. "EU‐China collaboration in the reform of the international monetary system: much ado about nothing?." The World Economy 37.1 (2014): 151-168.

- ↑ “The Growing Challenges for Monetary Policy in the Current International Monetary and Financial System - Speech by Mark Carney.” Bank of England, 13 August 2019.

- ↑ Giles, Chris. “Mark Carney Calls for Global Monetary System to Replace the Dollar.” Financial Times, 23 Aug. 2019.

- ↑ Arnold, Martin. “ECB Cuts Rates and Tells Governments to Act.” Subscribe to Read | Financial Times, Financial Times, 12 Sept. 2019.

- ↑ Trump, Donald J. “European Central Bank, Acting Quickly, Cuts Rates 10 Basis Points. They Are Trying, and Succeeding, in Depreciating the Euro against the VERY Strong Dollar, Hurting U.S. Exports.... And the Fed Sits, and Sits, and Sits. They Get Paid to Borrow Money, While We Are Paying Interest!” Twitter, Twitter, 12 Sept. 2019.

- ↑ “ECB Action, Hit by Trump as 'Hurting U.S. Exports,' Ups Pressure on Fed.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 12 Sept. 2019.

- ↑ Henri Denis, Histoire de la pensée économique, Thémis 1966, p. 92 §4

- ↑ Histoire des pensées économiques, T1 les fondateurs, p. 16, Sirey 1993, (ISBN 2-247-01666-9)

- ↑ Béraud, Alain, and Philippe Steiner. "France, Economics in, before 1870." The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (2008): 3-475.

- ↑ Mayerne, Louis Turquet de (1550?-1618). La monarchie aristodémocratique, ou Le gouvernement composé et meslé des trois formes de légitimes républiques. (1611)

- ↑ Tremblay, Jean-Marie. “Jean-Jacques Rousseau, [Discours Sur L'économie Politique] (1755).” Les Classiques Des Sciences Sociales.

- ↑ Charles Gide, Principes d’économie politique, 1930

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. Political economy. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Smith, Adam. “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith.” Project Gutenberg, 1 June 2002.

- ↑ Heilbroner, Robert L. “The Wealth of Nations.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ↑ On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, by David Ricardo. Complete, fully searchable text at the Library of Economics and Liberty.

- ↑ Principles Of Political Economy by John Stuart Mill, (illustrated 1884 edition) on Project Gutenberg (online version and in PDF format.); attractively formatted, easily searchable version of the work.

- ↑ The “National System of Innovation” in historical perspective. (1995). Cambridge Journal of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035309

- ↑ Senghaas, D. Friedrich List, Das nationale System der politischen Ökonomie, Stuttgart/Tübingen 1841. In Schlüsselwerke der Politikwissenschaft (pp. 255–258). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90400-9_69

- ↑ List, Friedrich, and Eugen Wendler. Friedrich List : Das nationale System der politischen Ökonomie. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2008. Print.

- ↑ List, Friedrich, and Pedro Schwartz. “The National System of Political Economy.” Econlib.

- ↑ Lind, Michael, Hamilton's Republic, 1997, pp. xiv-xv, 229–30.

- ↑ Cohen, Benjamin J. International political economy : an intellectual history". Page 17. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- ↑ Clarke, S. (1991). The Marginalist Revolution in Economics. In Marx, Marginalism and Modern Sociology (pp. 182–206). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-21808-0_6

- ↑ “A General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy” (PDF), The Theory of Political Economy (1871).

- ↑ Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre (translated as Principles of Economics PDF)

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2019, December 13). Marginalism. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Marginalism

- ↑ Principles of Economics By Alfred Marshall | The Library of Economics and Liberty

- ↑ Marx, K. and Engels, F. (1848).The Communist Manifesto

- ↑ 46,0 et 46,1 Wikipedia contributors. (2020, March 4). Karl Marx. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17:26, March 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Karl_Marx

- ↑ O’Laughlin, B. (1975). Marxist Approaches in Anthropology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 4(1), 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.04.100175.002013

- ↑ Roseberry, W. (1997). MARX AND ANTHROPOLOGY. Annual Review of Anthropology, 26(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.25

- ↑ Becker, S. L. (1984). Marxist approaches to media studies: The British experience. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 1(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295038409360014

- ↑ Sheehan, H. (2007). Marxism and Science Studies: A Sweep through the Decades. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 21(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/02698590701498126

- ↑ Rudolf Hilferding, Finance Capital. A Study of the Latest Phase of Capitalist Development. Ed. Tom Bottomore (Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1981)

- ↑ Kowalik, T. (2014). Rudolf Hilferding’s Theory of Finance Capital. In Rosa Luxemburg (pp. 131–142). https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137428349_10

- ↑ Scott, Helen (2008). "Introduction to Rosa Luxemburg". The Essential Rosa Luxemburg: Reform or Revolution and The Mass Strike. By Luxemburg, Rosa. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books. p. 18.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2019, December 18). The Accumulation of Capital. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17:47, March 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Accumulation_of_Capital

- ↑ Géraldine Vaughan, Clarisse Berthezene, Pierre Purseigle, Julien Vincent, Le Monde britannique 1815-1931, Historiographie, Bibliographie, Enjeux, Belin, 2010, p. 11

- ↑ Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism by Vladimir Lenin at the Marxists Internet Archive

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2020, February 24). Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20:56, March 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Imperialism,_the_Highest_Stage_of_Capitalism

- ↑ Paul Bowles (2007) Capitalism, Pearson: London. pp. 91–93

- ↑ Imperialism the Highest Stage of Capitalism III. Finance Capital and the Financial Oligarchy

- ↑ Erreur Lua : impossible de créer le processus : proc_open n’est pas disponible. Vérifiez la directive de configuration PHP « disable_functions ».

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2020, March 6). Dependency theory. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:22, March 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Dependency_theory

- ↑ Théorie de la dépendance. (2019, September 3). Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Page consultée le 01:30, September 3, 2019 à partir de http://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Th%C3%A9orie_de_la_d%C3%A9pendance

- ↑ 63,0 et 63,1 Alekseenko, Oleg, and Ilya Ilyin. "The Grand Theories of Integration Process and the Development of Global Communication Networks." Globalistics and Globalization Studies: Global Transformations and Global Future.: 226.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2020, February 18). Institutional economics. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:40, March 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Institutional_economics

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2020, March 8). Thorstein Veblen. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:56, March 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thorstein_Veblen

- ↑ Diggins, John P. (1978). The Bard of Savagery: Thorstein Veblen and Modern Social Theory. New York: Seabury Press.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2019, December 19). The Theory of the Leisure Class. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:52, March 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Theory_of_the_Leisure_Class

- ↑ Jérôme Maucourant. Polanyi on institutions and money: An interpretation suggested by a reading of Commons, Mitchell and Veblen. Adaman, Fikret; Devine, Pat. Economy and society: money, capitalism and transition, Black Rose Books, pp.150-171, 2001, Critical Perspectives on Historic Issues.

- ↑ Institut Polanyi. “Pourquoi Polanyi.” Institut Polanyi: France, institutpolanyi.fr/site/karl-polanyi/.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2020, January 20). The Great Transformation (book). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22:05, March 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Great_Transformation_(book)

- ↑ Stanfield, J. Ron. “The Institutional Economics of Karl Polanyi.” Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 14, no. 3, 1980, pp. 593–614. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4224945.

- ↑ Albert O. Hirschman. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN: 0-674-27660-4 (paper).

- ↑ Dowding, K. (2016). Albert O. Hirschman. In M. Lodge, E. C. Page, & S. J. Balla (Eds.), Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199646135.013.30

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2020, March 9). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 09:27, March 10, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Exit,_Voice,_and_Loyalty

- ↑ Adelman, Jeremy. Worldly philosopher: the odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman. Princeton University Press, 2014.

- ↑ “Albert O. Hirschman (1915 - 2012): School of Social Science.” Albert O. Hirschman (1915 - 2012) | School of Social Science, https://www.sss.ias.edu/faculty/hirschman

- ↑ “The Albert O. Hirschman Prize.” Social Science Research Council, https://www.ssrc.org/fellowships/view/the-albert-o-hirschman-prize/about-albert-o-hirschman/.

- ↑ Haas, Ernst B. The uniting of Europe : political, social, and economic forces, 1950-1957. Notre Dame, Ind: University of Notre Dame Press, 2004. Print

- ↑ Knorr, K. (1959). ERNST B. HAAS. The Uniting of Europe: Political, Social, and Economic Forces 1950-1957. Pp. xx, 552. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1958. $8.00. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 324(1), 181–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271625932400163

- ↑ Rosamond, B. (2005). The uniting of Europe and the foundation of EU studies: Revisiting the neofunctionalism of Ernst B. Haas. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(2), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500043928

- ↑ The Uniting of Europe: Political, Social, and Economic Forces, 1950–1957. By <italic>Ernst B. Haas</italic>. (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. 1958. Pp. xx, 552. $8.00.). (1959). The American Historical Review. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/64.3.629

- ↑ Haas, E. B. (1967). THE UNITING OF EUROPE AND THE UNITING OF LATIN AMERICA. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 5(4), 315–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1967.tb01153.x

- ↑ Haas, Ernst B. “International Integration: The European and the Universal Process.” International Organization, vol. 15, no. 3, 1961, pp. 366–392. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2705338.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2016, April 1). Ernst B. Haas. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 10:57, March 10, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ernst_B._Haas

- ↑ Fisher, W. E. (1969). An Analysis of the Deutsch Sociocausal Paradigm of Political Integration. International Organization, 23(2), 254–290. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818300031593

- ↑ Deutsch, К. 1957. Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience. By <italic>Karl W. Deutsch</italic>, <italic>et al.</italic> [Publications of the Center for Research on World Political Institutions, Princeton University.] (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press. 1957. Pp. xiii, 228. $4.75.). (1958). The American Historical Review. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/63.2.375

- ↑ Thompson, K. W. (1958). Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience. By Karl W. Deutsch, Sidney A. Burrell, Robert A. Kann, Maurice LeeJr.,, Martin Lichterman, Raymond E. Lindgren, Francis L. Loewenheim, and Richard W. Van Wagenen. (Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1957. Pp. xiii, 228. $4.75.). American Political Science Review, 52(2), 531–533. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952332

- ↑ Rosecrance, R. N. (1958). Book Reviews : Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience. By KARL W. DEUTSCH, SIDNEY A. BURRELL, ROBERT A. KANN, MAURICE LEE, JR., MARTIN LICHTERMAN, RAYMOND E. LINDGREN, FRANCIS L. LOEWENHEIM, and RICHARD W. VAN WAGENEN. (Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1957. Pp. xiii, 228. $4.75.). Political Research Quarterly, 11(4), 902–903. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591295801100419

- ↑ Deutsch, Karl Wolfgang. The analysis of international relations. Vol. 12. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1968.

- ↑ Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph S. Nye. Power and interdependence. Boston: Longman, 2012. Print.

- ↑ Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S., Jr. (1973). Power and interdependence. Survival, 15(4), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396337308441409

- ↑ Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S., Jr. (1987). Power and Interdependence revisited. International Organization, 41(4), 725–753. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818300027661

- ↑ Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph S. Nye Jr. "Power and interdependence in the information age." Foreign Aff. 77 (1998): 81.

- ↑ Skidelsky, Robert Jacob Alexander. "John Maynard Keynes, 1883-1946: economist, philosopher, statesman." (2003).

- ↑ Viner, J. (1932). Cost curves and supply curves. Zeitschrift Für Nationalökonomie, 3(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01316299

- ↑ Lewis, W. Arthur. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 6, no. 1, 1975, pp. 172–174. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/202837.

- ↑ Kindleberger, Charles P., and Robert Z. Aliber. Manias, panics, and crashes : a history of financial crises. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons, 2005. Print.

- ↑ “Of Manias, Panics and Crashes.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper, 17 July 2003.

- ↑ Yuen, Raymond Wai Pong, Book Review – Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises 5th Edition (Author of the Book: Charles P. Kindleberger and Robert Aliber) (September 21, 2012). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2127952 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2127952

- ↑ Vincent Ferraro. "The Theory of Hegemonic Stability." http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pol116/hegemony.htm

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2020, January 11). Hegemonic stability theory. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19:32, March 10, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hegemonic_stability_theory

- ↑ Itoh, Makoto. The World Economic Crisis and Japanese Capitalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan Limited, 1990. Print.

- ↑ Strange, Susan. “The Dollar Crisis 1971.” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), vol. 48, no. 2, 1972, pp. 191–216. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2613437.

- ↑ Diebold, W., & Gowa, J. (1984). Closing the Gold Window: Domestic Politics and the End of Bretton Woods. Foreign Affairs, 63(1), 190. https://doi.org/10.2307/20042113

- ↑ International Monetary Fund, . (1996). "Chapter 26: Road to the Smithsonian Agreement (August 16–December 18, 1971)". In The International Monetary Fund 1966-1971 : The System Under Stress Volume I: Narrative. USA: INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. doi: https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451971477.071

- ↑ Chen, James. “Smithsonian Agreement.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 26 Feb. 2020, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/smithsonian-agreement.asp.

- ↑ Pierce, Francis S., and Roy Forbes Harrod. “The Smithsonian Agreement and After.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 14 Mar. 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/international-payment/The-OECD#ref125864.

- ↑ Humpage, Owen. “The Smithsonian Agreement.” Federal Reserve History, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/smithsonian_agreement.

- ↑ Forsberg, Aaron. America and the Japanese miracle: the Cold War context of Japan's postwar economic revival, 1950-1960. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000. Print.

- ↑ Monroe, Wilbur F. “Japan's Economy in the 1970s: Implications for the World.” Pacific Affairs, vol. 45, no. 4, 1972, pp. 508–520. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2755656.

- ↑ Makin, John H., and John H. Makin. Capital flows and exchange-rate flexibility in the post-Bretton Woods era. No. 103. International Finance Section, Princeton University, 1974.

- ↑ Frankel, Jeffrey A., et al. "International capital flows and domestic economic policies." The United States in the world economy. University of Chicago Press, 1988. 559-658.

- ↑ Yang, D. (2008). Coping with Disaster: The Impact of Hurricanes on International Financial Flows, 1970-2002. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.1903

- ↑ Baripedia. Money, Finance and the World Economy: 1974 - 2000. from https://baripedia.org/w/index.php?title=Money,_Finance_and_the_World_Economy:_1974_-_2000

- ↑ Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph S. Nye. Power and interdependence. New York: Longman, 2001. Print.

- ↑ “International Organization.” Cambridge Core, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-organization.

- ↑ International Organization.” JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/journal/inteorga

- ↑ Jackson, Robert H., Jørgen Møller, and Georg Sørensen. Introduction to international relations : theories and approaches. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019. Print. page 202

- ↑ Maliniak, D., & Tierney, M. J. (2009). The American school of IPE. Review of International Political Economy, 16(1), 6–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290802524042

- ↑ BROWN, C. (1999). Susan Strange—a critical appreciation. Review of International Studies, 25(3), 531–535. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0260210599005318

- ↑ Susan Strange. “International Economics and International Relations: A Case of Mutual Neglect.” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), vol. 46, no. 2, 1970, pp. 304–315. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2613829.

- ↑ Cohen, B. J. (2015). A concluding note. Contexto Internacional, 37(3), 1069–1080. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-85292015000300010

- ↑ Murphy, C. N., & Nelson, D. R. (2001). International Political Economy: A Tale of Two Heterodoxies. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 3(3), 393–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856x.00065

- ↑ Leiteritz, R. J. (2005). International Political Economy: the state of the art. Colombia Internacional, (62), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint62.2005.03

- ↑ Weber, H. (2015). Is IPE just “boring”,1 or committed to problematic meta-theoretic|al assumptions? A critical engagement with the politics of method. Contexto Internacional, 37(3), 913–944. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-85292015000300005

- ↑ Cohen, Benjamin J. “The Transatlantic Divide: Why Are American and British IPE so Different?” Review of International Political Economy, vol. 14, no. 2, 2007, pp. 197–219. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25261908.

- ↑ Cohen, B. J. (2007). The transatlantic divide: A rejoinder. Review of International Political Economy, 15(1), 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290701751266

- ↑ Wullweber, J. (2018). Monism vs. pluralism, the global financial crisis, and the methodological struggle in the field of International Political Economy. Competition & Change, 23(3), 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418813830

- ↑ Reflections on the “British School” of International Political Economy. (2009). New Political Economy, 14(3), 313–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563460903087425

- ↑ Marchiano, Aldo. “International Political Economy Research: American School vs. British School.” Sui Genesis, 2014, https://www.sett.com/suigeneris/international-political-economy-research-american-school-vs-british-school.

- ↑ Lee, Donna, and David Hudson. “The Old and New Significance of Political Economy in Diplomacy.” Review of International Studies, vol. 30, no. 3, 2004, pp. 343–360. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20097922.

- ↑ Dickins, Amanda. “The Evolution of International Political Economy.” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), vol. 82, no. 3, 2006, pp. 479–492. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3874263.

- ↑ Bluedorn, A. C., & Evered, R. (1980). Middle Range Theory and the Strategies of Theory Construction. In Middle Range Theory and the Study of Organizations (pp. 19–32). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-8733-3_2

- ↑ Veseth, Michael A., and David N. Balaam. “International Political Economy.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 3 Mar. 2014, https://www.britannica.com/topic/political-economy/International-political-economy.

- ↑ Keohane, R. O. (2009). The old IPE and the new. Review of International Political Economy, 16(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290802524059

- ↑ Robert H. Bates, 1998. "Introduction to Open-Economy Politics: The Political Economy of the World Coffee Trade," Introductory Chapters, in: Open-Economy Politics: The Political Economy of the World Coffee Trade, Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Lake, David A. "Open economy politics: A critical review." The Review of International Organizations 4.3 (2009): 219-244.

- ↑ Gourevitch, P. A., Keohane, R. O., Krasner, S. D., Laitin, D., Pempel, T. J., Streeck, W., & Tarrow, S. (2008). The Political Science of Peter J. Katzenstein. PS: Political Science & Politics, 41(4), 893–899. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049096508211273

- ↑ Peter J. Katzenstein, ed. Between Power and Plenty: Foreign Economic Policies of Advanced Industrial States. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978. (1980). Politics & Society, 10(1), 115–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/003232928001000112

- ↑ Cohen, Benjamin J. International political economy : an intellectual history. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008. Print. page 125

- ↑ Talani, Leila Simona. European political economy: issues and theories. Routledge, 2016. page 45-46

- ↑ Clement, Wallace, and Glen Williams. The New Canadian political economy. Kingston Montreal London: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1989. Print.

- ↑ Cohen, Benjamin J. Advanced introduction to international political economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019. Print.