Switzerland's state structure, political system and neutrality

Based on a course by Victor Monnier[1][2][3]

Introduction to the Law : Key Concepts and Definitions ● The State: Functions, Structures and Political Regimes ● The different branches of law ● The sources of law ● The great formative traditions of law ● The elements of the legal relationship ● The application of law ● The implementation of a law ● The evolution of Switzerland from its origins to the 20th century ● Switzerland's domestic legal framework ● Switzerland's state structure, political system and neutrality ● The evolution of international relations from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century ● The universal organizations ● European organisations and their relations with Switzerland ● Categories and generations of fundamental rights ● The origins of fundamental rights ● Declarations of rights at the end of the 18th century ● Towards the construction of a universal conception of fundamental rights in the 20th century

The Federal State and the main bodies of the Confederation and the Cantons

The history of the Swiss federal state is one of compromise and balance, reflecting the need to reconcile a variety of interests in a country marked by great cultural and linguistic diversity. The competence of the federal state, while substantial, is not total, as the cantons retain a degree of sovereignty. This tension between federalism and cantonalism has been a constant feature of Swiss political history.

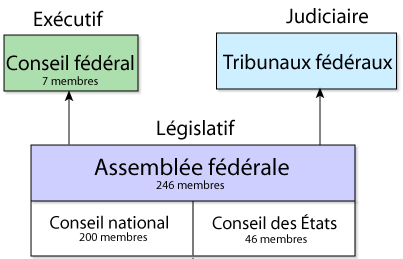

Bicameralism has proved to be the least worst solution for reconciling these divergent interests. The Federal Assembly, made up of the National Council and the Council of States, embodies this compromise. The National Council represents the people and is directly elected by them, reflecting representative democracy. The Council of States, on the other hand, represents the cantons, ensuring that their interests are also taken into account at federal level. Another key element of this system is the need for a double majority to make changes to the Constitution. This mechanism requires not only the approval of the majority of voters at national level, but also that of the majority of cantons. This requirement ensures that constitutional changes receive broad support, both from the general population and from the various regions of the country.

Prior to 1848, the year in which modern Switzerland was formed, the country did not have a centralised executive. The creation of the Federal Council was a response to this shortcoming, providing Switzerland with a stable and effective executive body. The Federal Council, made up of members elected by the Federal Assembly, became an essential element of Swiss governance, helping the country to navigate through the challenges of the 19th century. The progressives of the time, who wanted to abolish cantonal sovereignty, had to make compromises. Although the National Council strengthened democratic representation at federal level, the cantons retained significant influence through the Council of States and their legislative autonomy. This system has enabled Switzerland to maintain a balance between national unification and respect for regional particularities, a balance that continues to define the country's political structure.

At federal level

The Federal Assembly

The Federal Assembly, or Federal Parliament, is at the heart of the Swiss political system and represents the supreme legislative authority of the Confederation. This bicameral institution reflects the compromise between the principles of democratic representation and the equality of the cantons, which are essential to Switzerland's political balance.

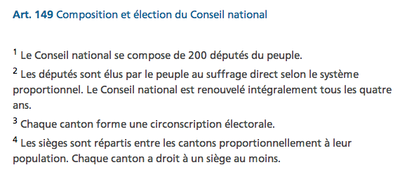

The National Council, the first chamber of the Federal Assembly, is made up of 200 deputies elected by the people. The members of this chamber are elected according to a proportional system, which means that the number of seats allocated to each canton is proportional to its population. This method of distribution ensures that the interests of the citizens of all the cantons, whether densely populated or not, are fairly represented at national level. Elections to the National Council are held every four years, and all Swiss citizens aged 18 and over are eligible to vote. The Council of States, the second chamber, is made up of 46 deputies. Each Swiss canton is represented in the Council of States by two deputies, with the exception of the so-called half-cantons, which each send a single representative. This structure ensures that each canton, regardless of its size or population, has an equal voice in this chamber. The Council of States therefore represents the interests of the cantons at federal level, ensuring a balance between popular representation and the equality of the cantons.

The interaction between these two chambers is essential to the Swiss legislative process. Bills must be approved by both chambers to become law. This requirement ensures that federal laws reflect both the will of the Swiss people (represented by the National Council) and the interests of the cantons (represented by the Council of States), thereby strengthening consensus and political stability within the Confederation.

The Swiss parliamentary system is a classic example of perfect bicameralism, in which the two chambers of parliament, the National Council and the Council of States, have equal powers and competences. This equality between the two chambers is fundamental to the functioning of Swiss democracy. In a perfect bicameralism, neither chamber has pre-eminence over the other. Thus, for a bill to become a federal law, it must be approved separately by both chambers. This need for mutual agreement ensures that the legislation passed has the support of both the representatives of the people (the National Council) and the representatives of the cantons (the Council of States). This guarantees a balanced legislative process that takes account of the different perspectives and interests within the country. The chambers sit separately in different rooms in the Federal Palace in Berne. This physical separation underlines their independence and functional equality. The National Council, representing the people, and the Council of States, representing the cantons, operate according to their own procedures and rules, but with equivalent legislative powers. This system of perfect bicameralism is a key element of the Swiss political structure, contributing to its stability and effectiveness by allowing a balanced representation of the various regional and national interests in the legislative process.

In the Swiss political system, members of the National Council and the Council of States serve on a militia basis. This means that their role as MPs is not regarded as a full-time profession, but rather as a function exercised alongside their usual professional career. This approach reflects the Swiss tradition of civic participation and the desire to keep politics close to the day-to-day concerns of citizens. Swiss MPs are not subject to an "imperative mandate", which means that they are not legally bound to vote according to the instructions of their party or constituents. They enjoy freedom of vote, allowing for more flexible and independent decision-making. This independence is essential to ensure that decisions taken in Parliament reflect a balance of different opinions and are not strictly dictated by party lines. To support their ability to represent their constituents effectively and exercise their mandate independently, Swiss MPs enjoy a form of parliamentary immunity. This immunity protects them from prosecution for opinions expressed or votes cast in the performance of their duties. However, it is important to note that this immunity is not absolute and does not cover illegal acts committed outside their official functions. This framework of the militia function and the absence of an imperative mandate, combined with parliamentary immunity, is designed to encourage political participation by ordinary citizens and ensure that MPs can act in the public interest without fear of undue repercussions.

Parliamentary immunity in Switzerland is an essential legal concept that ensures the protection of members of parliament and the smooth running of the legislative process. This immunity is divided into two main categories: non-accountability and inviolability, each of which plays a specific role in maintaining democratic integrity. Parliamentary non-accountability offers MPs protection against prosecution for opinions expressed or votes cast in the course of their official duties. This form of immunity is crucial to guaranteeing freedom of expression within Parliament, allowing MPs to debate and vote freely without fear of legal reprisal. A relevant historical example might be the heated debates surrounding controversial reforms, where MPs were able to express differing opinions without fear of legal consequences. Inviolability, on the other hand, protects the physical and intellectual freedom of parliamentarians by shielding them from prosecution during their term of office, unless otherwise authorised by the chamber to which they belong. This rule is designed to prevent intimidation or disruption of Members of Parliament by legal action, guaranteeing their full participation in legislative activities. A historical case of application of this rule could be envisaged during periods of political tension, when Members of Parliament could have been targeted for their political activity.

It is important to note that these immunities are not shields against all illegal actions. They are specifically designed to protect legislative functions and do not cover acts committed outside parliamentarians' official responsibilities. These protections are framed by strict rules to prevent abuse and maintain confidence in democratic institutions. The introduction of parliamentary immunity in Switzerland reflects the delicate balance between the necessary protection of legislators and accountability before the law. By ensuring that parliamentarians can carry out their duties without fear of inappropriate outside interference, while holding them accountable for their actions outside their official capacity, the Swiss system contributes to the stability and integrity of its democratic process.

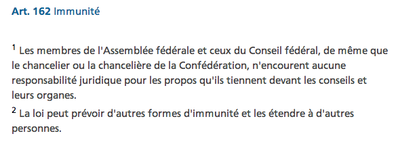

Article 162 of the Swiss Constitution establishes the fundamental principles of parliamentary immunity, covering members of the Federal Assembly, the Federal Council and the Chancellor of the Confederation. The purpose of this provision is to protect these figures from any legal liability for remarks made in the exercise of their official duties, in particular when speaking before the Councils and their bodies. The first paragraph of this article guarantees that these senior representatives cannot be held legally responsible for opinions or statements they make in the course of their official duties. This form of immunity, often referred to as non-liability, is essential to ensure freedom of expression within government institutions. It allows members of parliament and government to debate and express their opinions freely and openly, without fear of prosecution. This protection is fundamental to the functioning of democracy, as it encourages frank and uncensored discussion of matters of national interest. The second paragraph offers the possibility of extending this protection to include other forms of immunity. It allows legislation to extend immunity to other persons or in other circumstances, according to the needs identified for the proper functioning of the State. This flexibility ensures that the framework of parliamentary immunity can be adapted to meet the changing requirements of governance and political representation. Article 162 reflects Switzerland's commitment to protecting its legislators and senior officials, thereby facilitating an environment where political dialogue can take place without unnecessary impediments. This approach is crucial to maintaining the integrity and effectiveness of the Swiss legislative process.

National Council

The National Council, which is one of the two chambers of the Swiss Parliament, operates according to a unique electoral system that reflects both the principle of proportional representation and respect for regional diversity. Each Swiss canton is entitled to at least one seat on the National Council, ensuring that even the smallest cantons are represented in the national legislature. The proportional representation system used for National Council elections ensures that the distribution of seats accurately reflects the distribution of votes among the different political parties within each canton. This contrasts with a majority system, where the winning party in a region can win all the seats, which can lead to a disproportionate representation of political views.

In practice, the number of seats allocated to each canton is determined by its population. More populous cantons, such as Zurich, have a greater number of seats, while less populous cantons have a minimum of one seat. This method ensures that the interests of the citizens of all the cantons, large and small, are taken into account in the legislative process. Elections to the National Council are held every four years, and all Swiss citizens aged 18 and over are eligible to vote. This system of proportional representation contributes to the political diversity of the National Council, allowing a wide range of political voices and perspectives to be heard and represented at national level. This reinforces the democratic and inclusive nature of the Swiss political system.

Article 149 of the Swiss Constitution sets out in detail the composition and electoral process of the National Council, ensuring democratic and proportional representation of Swiss citizens at federal level. According to this article, the National Council is made up of 200 deputies, elected directly by the Swiss people. These elections take place every four years, reflecting the principle of renewal and democratic accountability. The use of direct suffrage enables all Swiss citizens aged 18 and over to play an active part in choosing their representatives, thereby strengthening civic commitment and the legitimacy of the legislative process. The proportional system, as the article states, is crucial to ensuring that the distribution of seats on the National Council is in line with the distribution of votes among the various political parties. This system favours a balanced representation of the various political currents and opinions within the population, allowing smaller parties to have a voice in parliament, unlike majority systems where the larger parties often have an advantage.

Each Swiss canton forms a separate electoral constituency for National Council elections. This ensures that the interests and particularities of each region are taken into account within the federal framework. The distribution of seats among the cantons is based on their population, ensuring that the more populous cantons have representation commensurate with their size. Nevertheless, even the smallest cantons are guaranteed at least one representative, which maintains a balance between the different regions of the country, regardless of their size or demographic weight. In this way, Article 149 of the Swiss Constitution provides a solid framework for democratic and fair representation on the National Council, reflecting the diversity and plurality of Swiss society. This structure contributes to political stability and inclusive representation, key elements of Swiss democracy.

Council of States

The Council of States, the second chamber of the Swiss Parliament, has distinct characteristics from the National Council, particularly in terms of how its members are elected and its role within the Federal Assembly. Unlike the National Council, where members are elected according to a proportional system, the method of electing members of the Council of States is left to the discretion of the cantons. In most cases, the cantons opt for a two-round majority system. This means that if no candidate obtains an absolute majority of votes in the first round, a second round is held between the candidates with the most votes. This method of election tends to favour the most popular candidates within each canton, thus directly reflecting local political preferences.

The Council of States plays a crucial role in Switzerland's political balance. Each canton, regardless of its size or population, is equally represented in this chamber, with two members for most cantons and one member for the half-cantons. This equality of representation ensures that the interests of smaller regions are not overwhelmed by those of larger, more populous cantons. In certain circumstances, the Federal Assembly, which comprises both the National Council and the Council of States, sits and deliberates as a single body. These joint sessions are called for important decisions, such as the election of members of the Federal Council, the Federal Supreme Court and other senior officials, as well as for decisions on relations between the Confederation and the cantons. This practice of sitting together allows for dialogue and integrated decision-making between the two chambers, reflecting the consensual approach to Swiss politics. The Council of States, with its unique method of election and its egalitarian role within the Federal Assembly, therefore plays an essential role in maintaining balance and representativeness within the Swiss political system, contributing to the stability and effectiveness of federal governance.

It is important not to confuse the Council of States, which is a component of the Swiss Federal Parliament, with the Council of State, the term used to designate the governments of the French-speaking Swiss cantons. The Council of States, as we have seen, is the upper chamber of the Swiss Parliament, where the cantons are equally represented. This chamber plays a key role in the legislative process at federal level and ensures a balanced representation of the cantons' interests in national governance. On the other hand, the Conseil d'Etat in the French-speaking cantons of Switzerland refers to the executive body at cantonal level. Each Swiss canton, whether French-speaking or not, has its own government, generally known as the Conseil d'État in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. These cantonal governments are responsible for local administration and for implementing laws and policies at cantonal level. They play an essential role in the management of cantonal affairs, including education, public health, police and transport, reflecting the autonomy and sovereignty of the cantons within the Swiss Confederation. This distinction between the Council of States (at federal level) and the Council of State (at cantonal level) is an example of the complexity and specificity of the Swiss political system, where federal and cantonal structures co-exist and interact in an integrated manner.

Article 168 of the Swiss Constitution clearly sets out the role of the Federal Assembly in the election of certain key government and judicial posts. This article underlines the importance of the Federal Assembly as the central decision-making body in the appointment of the country's senior officials.

According to the first paragraph of Article 168, it is the Federal Assembly that is responsible for electing the members of the Federal Council, which is Switzerland's supreme executive body. This election procedure ensures that the members of the federal government are chosen by the elected representatives of the people and the cantons, thereby strengthening the democratic legitimacy of the Federal Council. The Federal Assembly also elects the Federal Chancellor, who plays a key role in the administration of the federal government. In addition to the Federal Council and the Chancellor, the Federal Assembly is also responsible for electing judges to the Federal Supreme Court, Switzerland's highest judicial authority. This process of election by the representatives of the people and the cantons ensures that the judges of the Federal Supreme Court are selected in a transparent and democratic manner.

Article 168 also mentions the role of the Federal Assembly in the election of the General, a special position in Switzerland, usually activated only in times of crisis or war. The second paragraph of this article allows the law to give the Federal Assembly the power to elect or confirm the election of other officials. This provision offers a degree of flexibility, enabling the Swiss political system to adapt to the changing needs of governance. Article 168 highlights the centrality of the Federal Assembly in the governance of Switzerland, giving this institution significant power in appointing the key figures who run the country, and thus ensuring that these appointments are rooted in the democratic process.

The aims and tasks of the Federal Assembly

The Swiss Federal Assembly, as the supreme legislative body of the Confederation, plays a central and multifaceted role in the governance of the country. Its aims and tasks are varied and cover essential aspects of the functioning of the State. One of the primary roles of the Federal Assembly is to manage constitutional amendments. It is responsible for initiating and examining amendments to the Swiss Constitution, a process that requires careful attention to ensure that changes reflect the needs and aspirations of Swiss society while preserving the nation's fundamental principles.

In matters of foreign policy, the Federal Assembly plays a decisive role, in accordance with Article 166 of the Constitution. It is involved in formulating the main thrusts of Switzerland's foreign policy and in ratifying international treaties. This involvement ensures that foreign policy decisions enjoy democratic support and are taken with national interests in mind. The Federal Assembly is also responsible for drawing up the State budget and approving the accounts. This crucial financial task involves responsible management of public finances, ensuring that the State's resources are used efficiently and transparently.

In addition, the Federal Assembly ensures that relations between the federal state and the cantons are maintained, as stipulated in Article 172 of the Constitution. This role is essential to ensure cohesion and collaboration between the different levels of government in Switzerland, a country characterised by a high degree of federalism and regional autonomy. Finally, the Federal Assembly supervises the Federal Council, the Federal Supreme Court and the Federal Administration. It ensures that these bodies operate in accordance with the law and democratic principles, and has the power to investigate and intervene if necessary. These multiple responsibilities give the Federal Assembly a central role in Switzerland's political structure, ensuring that the federal government remains accountable to its citizens and operates in the interests of the nation as a whole.

Article 166 of the Swiss Constitution defines the role of the Federal Assembly in the management of international relations and the ratification of international treaties, while Article 177 sets out the operating principles of the Federal Council. According to Article 166, the Federal Assembly plays an active role in defining Switzerland's foreign policy and in overseeing its foreign relations. This means that it participates in the formulation of the broad outlines of foreign policy and ensures that the country's international actions are consistent with its interests and values. The Federal Assembly is also responsible for approving international treaties. This competence is crucial in ensuring that Switzerland's international commitments receive the democratic endorsement of its elected representatives. However, certain treaties may be concluded exclusively by the Federal Council, without requiring the approval of the Assembly, under conditions defined by law or by the international treaties themselves. Article 177 deals with the internal workings of the Federal Council, Switzerland's executive body. The Council operates on the principle of collegiate authority, meaning that decisions are taken collectively by all its members. This collegiate approach encourages consensual decision-making and reflects the pluralist and democratic nature of the Swiss political system. The article also specifies that the business of the Federal Council is divided among its members by department, each responsible for different areas of public administration. In addition, the right of appeal, which must be guaranteed, allows a certain delegation of responsibilities to departments or administrative units, while ensuring supervision and accountability. These articles illustrate how democratic structures and processes are integrated into the management of Switzerland's internal and external affairs, reflecting the country's commitment to transparent, accountable and participatory governance.

One of the main roles of the Swiss Federal Assembly is to legislate in all areas within the Confederation's remit. As the country's supreme legislative body, the Federal Assembly is responsible for creating, amending and repealing laws at federal level. This legislative task covers a wide range of areas, including but not limited to economic policy, public health, education, national defence, transport, the environment and foreign policy. The Federal Assembly's ability to legislate in these areas is essential to ensure that Swiss laws meet society's changing needs and contemporary challenges. In addition to its legislative role, the Federal Assembly has other important functions, such as overseeing the government (the Federal Council), managing relations between the Confederation and the cantons, and ratifying international treaties. These multiple responsibilities enable the Federal Assembly to play a central role in the governance and stability of Switzerland, ensuring that the country is run according to the principles of democracy, federalism and legality.

Article 163 of the Swiss Constitution sets out the forms in which the Federal Assembly may enact legislation, distinguishing between federal laws, ordinances and federal decrees. According to the first paragraph of this article, when the Federal Assembly establishes provisions that lay down rules of law, these provisions take the form of either a federal law or an ordinance. Federal laws are major legislative acts that require the approval of both chambers of the Federal Assembly (the National Council and the Council of States) and, in certain cases, may be put to the vote of the people by referendum. Ordinances, on the other hand, are generally more detailed regulations that specify how federal laws are to be applied. The second paragraph deals with federal decrees, which are another form of legislative act. A federal decree may be used for decisions that do not require the creation of a new law or ordinance. Federal decrees are divided into two categories: those subject to referendum and those not subject to referendum. Federal decrees subject to referendum may be challenged by the people, while simple federal decrees are not subject to this procedure. This distinction between different forms of legislation enables the Federal Assembly to adapt its legislative process to the specific requirements of each situation. It also ensures that laws and regulations are adopted in an appropriate manner, with a degree of flexibility to meet the changing needs of Swiss society and the State.

The Swiss Federal Assembly organises its activities into different sessions, which are defined periods during which members meet to deliberate and take decisions. These sessions may be ordinary or extraordinary. Ordinary sessions are scheduled and take place according to an established timetable, while extraordinary sessions may be convened to deal with urgent or specific matters that require immediate attention. During these sessions, the members of the Federal Assembly have the opportunity to speak, express their opinions and participate actively in the decision-making process. This interaction is crucial to the democratic functioning of the Assembly, as it enables elected representatives to discuss, debate and shape the Confederation's legislation and policies.

The term "referral" refers to the means or instruments available to parliamentarians to influence the legislative and constitutional process. These tools enable members of the Federal Assembly to launch legislative initiatives, propose amendments, put questions to the Federal Council and take part in other parliamentary activities. Referral is an essential part of the role of parliamentarians, giving them the ability to represent the interests of their constituents effectively and to make a significant contribution to the governance of the country. In the field of legislation, referral enables parliamentarians to propose new laws or amend existing ones. In the constitutional field, it offers the possibility of initiating or amending constitutional provisions, a process which may involve a popular referendum depending on the nature and extent of the proposed change. This combination of regular sessions, the ability to hold extraordinary sessions and the right of referral ensures that the Swiss Federal Assembly remains a dynamic legislative body, capable of responding effectively to the needs of the Swiss people.

Under the Swiss parliamentary system, members of the Federal Assembly have a number of legislative and procedural tools at their disposal to influence governance and policy. These tools, collectively known as referrals, play an essential role in the democratic functioning of Switzerland. The parliamentary initiative is a powerful tool that allows members of parliament to directly propose bills or general recommendations for new legislation. A relevant historical example might be the introduction of a parliamentary initiative to reform a specific social or economic policy, reflecting the urgent concerns of citizens. A motion, on the other hand, is a means by which parliamentarians can propose bills or suggest specific measures. For these motions to become effective, they must be approved by the other chamber of parliament, thus ensuring a balance and verification of legislative proposals. A concrete example might be a motion to improve national infrastructure, requiring the agreement of both houses for its implementation. The postulate is an instrument that allows parliamentarians to ask the Federal Council to examine the advisability of proposing a bill or taking a specific measure. It can also involve requesting the submission of a report on a given subject. A postulate could be used to request an assessment of the environmental impact of a new policy. An interpellation is a way for members of parliament to request information or clarification from the Federal Council on specific issues. This process enhances transparency and allows effective parliamentary control over the executive. For example, an interpellation could be used to question the government on its response to an international crisis. The question is similar to the interpellation, but focuses on obtaining information relating to specific affairs of the Confederation. This mechanism provides a direct means for parliamentarians to clarify issues of policy or governance. Finally, Question Time is a period during which members of the Federal Council respond directly and orally to questions from parliamentarians. This direct dialogue allows for a dynamic exchange and often sheds light on the government's positions and intentions on various issues. These various instruments of referral, used historically and currently by Swiss parliamentarians, illustrate the dynamic and interactive nature of Swiss democracy, enabling responsible and responsive governance in response to the needs and concerns of the population.

Between 2008 and 2012, parliamentary activity in Switzerland was marked by a high volume of interventions by members of the Federal Assembly, reflecting their active involvement in governance and legislation. In total, more than 6,000 interventions were tabled, covering a wide range of areas and subjects, demonstrating the vitality of Swiss democracy and the involvement of parliamentarians in the country's affairs. Of these, 400 were parliamentary initiatives. By enabling parliamentarians to propose bills directly, these initiatives demonstrate their proactive role in creating and amending legislation. Around 1,300 motions were tabled. Motions, which require the approval of the other chamber of parliament to become effective, indicate a willingness on the part of parliamentarians to suggest changes to legislation or to push for specific measures. Members of parliament also submitted 700 postulates, asking the Federal Council to examine the advisability of proposing legislation or taking action on various subjects. These postulates are indicative of the search for information and evaluation that underpins legislative decision-making. With 1700 interpellations, the members of Parliament actively sought information and clarification from the Federal Council, demonstrating their role in monitoring and controlling the executive. Around 850 questions were put, underlining the constant need of parliamentarians to obtain specific information on various affairs of the Confederation, thus contributing to an enlightened debate and well-founded decision-making. Finally, between 200 and 300 written questions were submitted. These questions, which are often more detailed, enable parliamentarians to obtain information on specific aspects of policy or administration. The scale and diversity of these parliamentary interventions between 2008 and 2012 illustrate the commitment of the members of the Swiss Federal Assembly to represent their constituents effectively and to make a significant contribution to the governance of the country. This period has been marked by the active involvement of parliamentarians in all aspects of the legislative process and government oversight, reflecting the dynamic and responsive nature of Swiss parliamentary democracy.

Referral is not an exclusive privilege of members of the Federal Assembly in Switzerland; the Federal Council, which is the country's executive body, also holds the right of referral. This means that the Federal Council can take the initiative in submitting draft legislation to Parliament. This process is a fundamental aspect of the interaction between the legislative and executive branches of the Swiss government. When the Federal Council submits a bill to Parliament, it initiates the legislative process by presenting a text drawn up by the government. These bills may concern a wide variety of areas, such as economic reforms, social policies, environmental issues, or changes in legislation. Once a bill has been introduced, it is examined, debated and possibly amended by the members of the Federal Assembly before being voted on. This right of referral to the Federal Council plays a crucial role in the Swiss legislative process. It enables the government to actively propose legislative changes and respond to the needs and challenges identified in the country's administration. At the same time, the parliamentary process ensures that these proposals are subject to democratic scrutiny and thorough debate, ensuring that any new legislation reflects a wide range of perspectives and interests. The ability of the Federal Council to refer draft legislation to Parliament illustrates the balance between the executive and legislative powers in Switzerland, a balance that is essential to maintaining effective and democratic governance.

Article 181 of the Swiss Constitution clearly sets out the Federal Council's right of initiative, underlining its active role in the legislative process. Under this article, the Federal Council has the power to submit draft legislation to the Federal Assembly. This constitutional provision ensures that the country's executive body, the Federal Council, can play a significant role in shaping national policy and law. This right of initiative is an essential element of governance in Switzerland, as it allows the Federal Council to propose new laws or changes to legislation in response to the needs and challenges facing the country. These proposals can cover a wide range of areas, from economic policy to social legislation, from the environment to national security. Once a bill is presented by the Federal Council, it is examined by the two chambers of the Federal Assembly - the National Council and the Council of States. This process includes debates, committee discussions and possible amendments to the original text. The bill must be approved by both chambers before it becomes law. Article 181 reflects the collaborative nature of the Swiss political system, where the executive and legislative branches work together to formulate policy and legislation. This interaction between the branches of government ensures that Swiss laws are the result of a full democratic process, taking into account the views of the executive as well as the elected representatives of the people.

The Federal Council

Article 174 of the Swiss Constitution clearly defines the role of the Federal Council, affirming its position as the supreme directorial and executive authority of the Confederation. This provision underlines the Federal Council's status as the principal organ of government in Switzerland, responsible for directing and executing the affairs of state.

As the executive authority, the Federal Council is responsible for formulating government policy and directing the Confederation's administrative activities. This includes implementing laws passed by the Federal Assembly, managing relations with the cantons and foreign entities, and supervising the various federal departments and agencies. As the executive authority, the Federal Council is also responsible for the day-to-day administration of the government. This involves implementing and enforcing federal laws, managing the day-to-day business of the Confederation, and representing Switzerland internationally.

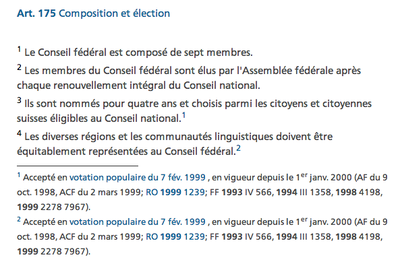

The Federal Council is made up of seven members elected by the Federal Assembly, reflecting Switzerland's collegiate system of governance. This collegiate structure guarantees consensual decision-making and a balanced representation of the country's different regions and language groups. The members of the Federal Council are responsible for different government departments, but decisions are taken collectively, in accordance with the principle of collegiality. Article 174 emphasises the central role of the Federal Council in the functioning of the Swiss state, ensuring that the country is run efficiently, responsibly and democratically.

The Swiss government, formally known as the Federal Council, is a unique executive body, characterised by its collegiate structure and election system. Composed of seven members, the Federal Council is elected for a four-year term by the Federal Assembly, which comprises the two chambers of the Swiss parliament (the National Council and the Council of States).

The President of the Confederation, who is elected for a one-year term, does not have greater executive power than his colleagues in the Federal Council, but rather serves as a "prima inter pares", or first among equals. The President's role is primarily ceremonial and symbolic, involving chairing meetings of the Federal Council and representing Switzerland in certain official functions. This approach reflects the principle of collegiality and equality within the Federal Council, a distinctive aspect of Swiss governance.

The Federal Chancellor, on the other hand, acts as a kind of principal secretary to the government, supporting the Federal Council in its administrative and organisational functions. Although the Chancellor is not a member of the Federal Council, this role is essential to the smooth running of the executive. As the supreme executive authority, the Federal Council is responsible for directing and implementing government policy. It also plays a role in the legislative process, notably by submitting draft legislation to the Federal Assembly for consideration and adoption. The election of the Federal Council every four years, following the complete renewal of the National Council, ensures regular alignment with the elected representatives of the Swiss people. This ensures that the executive remains in step with the priorities and perspectives of the legislature, thereby enhancing the coherence and effectiveness of governance across the Confederation.

Article 175 of the Swiss Constitution precisely defines the composition and election procedures of the Federal Council, the Confederation's executive body. This legislative framework guarantees balanced and democratic representation within the Swiss government. The first paragraph confirms that the Federal Council is composed of seven members. This structure is designed to promote collegial decision-making and ensure diverse representation within the executive. According to the second paragraph, the members of the Federal Council are elected by the Federal Assembly after each complete renewal of the National Council. This provision ensures that the election of the Federal Council is synchronised with the electoral cycle of the National Council, thereby strengthening coherence between the legislative and executive branches. The third paragraph stipulates that the members of the Federal Council are appointed for a term of four years and must be chosen from among Swiss citizens eligible to stand for election to the National Council. This ensures that the members of the Federal Council have the necessary qualifications and experience to take on high-level government responsibilities. Finally, the fourth paragraph emphasises the importance of equitable representation of Switzerland's different regions and linguistic communities within the Federal Council. This provision reflects Switzerland's cultural and linguistic diversity and aims to ensure that all parts of the country are represented in the decision-making process at the highest level of government. Together, these elements of Article 175 contribute to the formation of a federal government that is not only democratically elected, but also representative of the rich mosaic of Swiss society.

Comparing the members of the Swiss Federal Council with the executive of the French government can be instructive in understanding the differences in government structures and the roles of executive officials in the two countries. However, it is important to note that although both systems have executive responsibilities, they operate according to different principles. In France, the government is headed by the President, assisted by the Prime Minister and ministers. The President has considerable powers and plays a leading role in the affairs of state, while the Prime Minister and ministers manage specific departments or ministerial portfolios. This system is more hierarchical and centralised, with a clearly defined role for each member of the executive. In Switzerland, the members of the Federal Council operate on a collegiate model, where no one member has supremacy over the others. Each Federal Councillor heads a government department, but important decisions are taken collectively. This structure reflects the principle of "prima inter pares" (first among equals) for the President of the Confederation, which is a primarily representative role and confers no additional executive power. In this sense, Swiss federal councillors can be seen as "more than ministers", as they do not simply head individual departments; they are collectively responsible for the government as a whole. This contrasts with the French model, where ministers are primarily responsible for their own ministries, under the direction of the President and Prime Minister. This difference illustrates the varying approaches to governance in democratic systems. Whereas France opts for a more centralised system with clearly hierarchical executive roles, Switzerland favours a collegiate and egalitarian model, reflecting its commitment to federalism and balanced representation.

The Swiss Federal Council is indeed a remarkable example of coalition government, reflecting the country's political diversity. In Switzerland, the Federal Council is not formed by a single political party, but rather by a representation of several of the country's main political formations. This structure is rooted in the Swiss political tradition of concordance, which aims to ensure a balanced representation of the different political forces in government. This coalition approach within the Federal Council allows for more inclusive and consensual governance. By integrating various political parties, the Swiss government seeks to represent a wide range of perspectives and interests within Swiss society. This balanced representation is crucial in a country characterised by linguistic, cultural and political diversity. The composition of the Federal Council generally reflects the distribution of political forces in parliament. Seats are allocated to parties according to their electoral strength, which ensures that the country's main political parties are represented in government. However, it is important to note that the exact composition of the Federal Council and the distribution of seats between parties can vary depending on elections and political negotiations. This form of coalition government is one of the unique features of Swiss democracy, contributing to its political stability and its ability to manage internal diversity effectively. By encouraging collaboration and consensus between the different parties, the Swiss Federal Council system facilitates balanced and considered governance that takes account of the plurality of opinions and interests within society.

The constitutional revision process in Switzerland is a striking example of direct democracy in action, involving both the parliamentary chambers and the Swiss people. When a revision of the Constitution is proposed, it must first be approved by the Federal Assembly, made up of the National Council and the Council of States. However, this is only the first stage of the process. If the two chambers cannot reach a consensus on the revision, or if the nature of the revision requires a more direct democratic decision, the matter is then put to the Swiss people in a referendum. This is where the uniqueness of Swiss democracy comes into its own. Citizens have the power to make direct decisions on important issues, including constitutional amendments. A notable example of this might be the 2009 constitutional revision concerning the ban on building new minarets, a decision that was taken directly by the Swiss people through a referendum. In the Swiss system, unlike in other democracies, the practice of dissolving parliamentary chambers following a referendum decision is not common. Parliamentary elections in Switzerland are held on a fixed four-year cycle, irrespective of the outcome of referendums or constitutional revisions. This approach promotes political stability and ensures that the people's decisions are incorporated into the existing institutional framework, without causing major disruption to the legislative or administrative process. This system has proved its worth in terms of governance, enabling Switzerland to effectively combine direct citizen participation with institutional stability. It illustrates how Switzerland integrates the principles of direct democracy into a stable parliamentary framework, allowing citizens to directly influence policy while maintaining continuous and effective government.

In accordance with Article 177 of the Constitution, the Swiss Federal Council operates as a collegiate body. This characteristic is fundamental to understanding the nature of the Swiss government and the way in which it takes decisions. In a collegiate body such as the Federal Council, no single member, including the President of the Confederation, has superior executive power over the others. Each member of the Council has an equal voice in decision-making, and decisions are taken collectively by vote or consensus among all members. This favours an approach to governance based on consensus and collaboration, reflecting Switzerland's democratic values.

The President of the Confederation, elected for a one-year term from among the members of the Council, is not a head of state or head of government in the traditional sense. Rather, his role is that of a "prima inter pares" or first among equals. The President chairs the meetings of the Federal Council and performs representative functions for Switzerland, both nationally and internationally. However, this position does not confer additional executive powers or superior authority over government affairs. More symbolically, the President represents the unity and continuity of the Federal Council. This collegiate structure of the Federal Council is a key element of Swiss democracy. It ensures that government decisions are the result of collective and balanced deliberation, reflecting a diversity of opinions and interests. This contrasts with other systems of government where a president or prime minister has considerable executive powers. In Switzerland, the emphasis is on collaboration and equality within the executive, in line with its traditions of consensual democracy and federalism.

Article 177 of the Swiss Constitution lays the foundations for the operation of the Federal Council, emphasising the principle of collegial authority and the way in which responsibilities are distributed among its members. The first paragraph of this article stipulates that the Federal Council takes its decisions as a collegial authority. This means that decisions are not taken by a single member acting autonomously, but rather through a process of deliberation and consensus within the Council as a whole. This method of collective decision-making is a central feature of Swiss governance, reflecting the country's commitment to participatory democracy and consensus. According to the second paragraph, although decisions are taken collectively, the preparation and execution of these decisions are divided among the members of the Federal Council by department. Each Federal Councillor heads a specific department and is responsible for its administration and policy implementation. This division of tasks ensures that each area of governance is managed by an expert, while maintaining the collegiate approach to final decision-making. The third paragraph states that the management of day-to-day affairs may be delegated to departments or subordinate administrative units, while guaranteeing the right of appeal. This means that although day-to-day tasks are managed by individual departments, there are mechanisms to ensure supervision and accountability, as well as to allow appeals against administrative decisions.

The seven members of the Federal Council are considered equal, with each having one vote in collective decisions, reflecting the principle of collegiality. However, the statement that the President's vote counts double in the event of a tie requires clarification. In the usual practice of the Swiss Federal Council, the President of the Confederation does not have a casting vote or superior executive power. The President's role is primarily ceremonial and representational, acting as "prima inter pares" or first among equals. Decisions within the Federal Council are taken on the basis of consensus or a majority of the votes of the members present. If there is a tie, the President's vote does not generally count double. In the Swiss system, the emphasis is on seeking consensus rather than a decisive vote by a single member, even in situations where votes are tied. This approach favours a collective and balanced decision-making process, in keeping with the spirit of participative democracy and collegiality that characterises the Swiss government. It is important to note that the specific rules governing voting and decision-making procedures within the Federal Council may vary and are defined in internal regulations. However, the principle of equal membership and collective decision-making remains a key element of Swiss governance.

In the Swiss political system, decisions taken by the Federal Council are taken collectively and bear the name of the Council as a whole. This is in line with the principle of collegial authority, which is at the heart of the way the Federal Council operates. Every decision, whether it concerns domestic policy, foreign policy or any other sphere of government activity, is the result of deliberation and consensus among the seven members of the Council. This process ensures that all decisions are taken taking into account the perspectives and expertise of all members, reflecting a balanced and considered approach. Once a decision is taken by the Federal Council, it is presented and implemented as a decision of the Council as a whole, not as that of an individual member. This underlines the unity and solidarity of the Federal Council as an executive body, and ensures that the government's actions are seen to represent the executive as a whole, not the views or interests of a single person or department. This system of collective decision-making is a fundamental element of the Swiss political structure, designed to promote transparency, accountability and efficiency in the management of state affairs.

In the Swiss system of government, each member of the Federal Council plays a dual role. On the one hand, he or she is head of a specific government department, and on the other, he or she is a member of the Federal Council as a collegiate body. As head of department, each Federal Councillor is responsible for the management and administration of his or her particular area. The departments cover various sectors such as foreign affairs, defence, finance, education, health, the environment, transport, etc. Each federal councillor oversees the activities of his or her department, including policy implementation and day-to-day management. However, beyond managing their individual departments, each Federal Councillor is also an equal member of the Federal Council as a collective entity. This means that, in addition to their departmental responsibilities, they participate in collegial decision-making on issues that affect the government and the state as a whole. Important decisions, including those that do not directly concern their department, are taken collectively by all members of the Federal Council, often after deliberation and consensus-building. This duality of roles reflects the Swiss system of governance, which values both specialist expertise in particular areas and collective decision-making to ensure the balanced and efficient management of the state's affairs. This ensures that, although each Federal Councillor has his or her own sphere of responsibility, overall government decisions are the result of collaboration and joint reflection.

The Swiss Federal Council is effectively representative of the country's main political parties, a feature that stems from the Swiss tradition of coalition government and concordance. This practice ensures that Switzerland's various major political currents are represented within the executive, reflecting the country's multi-party structure. This representation is the result of an unwritten agreement known as the "magic formula" (Zauberformel in German). Introduced in 1959 and adjusted since then, this formula determines the distribution of seats on the Federal Council between the main political parties, according to their electoral strength and representation in parliament. The aim is to ensure a stable and balanced government, in which the various political parties can work together in the national interest, while representing a broad spectrum of opinions and interests within Swiss society. The concordance system and the magic formula have fostered a stable and consensual political climate in Switzerland. By integrating various parties into the government, it encourages collaboration and compromise rather than confrontation. This also avoids excessive polarisation and ensures that government decisions reflect a variety of perspectives. However, it is important to note that, although the main parties are represented, the Swiss system does not guarantee each party a seat on the Federal Council. The distribution of seats is influenced by political negotiations and election results, and can vary according to political dynamics and elections.

Article 175 of the Swiss Constitution details the composition and election procedures of the Federal Council, underlining the importance of balanced representation and diversity in the Swiss government. Firstly, the Federal Council is made up of seven members. This relatively small size facilitates a collegial and efficient decision-making process, where each member has a significant influence. Secondly, these members are elected by the Federal Assembly after each complete renewal of the National Council. This means that Federal Council elections are synchronised with National Council electoral cycles, ensuring that the government reflects current political configurations and the sentiments of the Swiss people. Thirdly, the members of the Federal Council are appointed for a four-year term and must be chosen from among Swiss citizens eligible to stand for election to the National Council. This ensures that members of the Federal Council have the necessary political experience and qualifications to take on government responsibilities. Finally, the fourth point underlines the importance of equitable representation of Switzerland's different regions and linguistic communities within the Federal Council. This provision aims to ensure that all parts of the country are represented in the decision-making process, reflecting Switzerland's cultural and linguistic diversity and strengthening national unity. Article 175 therefore reflects the fundamental principles of Swiss democracy: balance, representativeness and diversity in government. These principles ensure that the Federal Council functions effectively and democratically, making decisions that take account of the plurality of perspectives and interests in Swiss society.

The practice of electing the President of the Swiss Confederation is based on the principle of seniority in the Federal Council. According to this custom, the role of President of the Confederation is generally assigned to a member of the Federal Council who has already served under the presidency of all his or her colleagues. This method is intended to ensure a fair rotation of the presidency and to recognise the experience and service of the most senior members of the Council. The President of the Confederation is elected for a one-year term and, in accordance with the principle of collegiality, holds no more power than the other members of the Council. The President's role is mainly ceremonial and representational, leading meetings of the Federal Council and representing Switzerland at official events. However, he does not enjoy any executive authority over and above that of his colleagues on the Council. The practice of electing the President on the basis of seniority reflects the values of consensual democracy and equality that lie at the heart of the Swiss political system. It also ensures that every member of the Council has the opportunity to serve as President, thus contributing to fair rotation and a balanced representation of different perspectives within the government.

The Presidency of the Swiss Confederation is primarily a function of representation of the government college, both inside and outside the country. The President of the Confederation is not a head of state or head of government in the traditional sense, but rather a member of the Federal Council who assumes a representative role for a period of one year. Within the country, the President of the Confederation represents the Federal Council at various official events, ceremonies and functions. He or she may speak on behalf of the Federal Council and represents the unity and continuity of the Swiss federal government. Abroad, the President assumes a diplomatic role, representing Switzerland on state visits, at international meetings, and in other contexts where high-level representation is required. Although Swiss foreign policy is primarily the responsibility of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, the President plays an important role in presenting a unified and coherent image of Switzerland on the international stage. It is important to emphasise that, despite this representative role, the President of the Confederation has no additional executive powers compared with the other members of the Federal Council. The Presidency is above all a representative and coordinating role within Switzerland's collegiate system of governance. This unique structure reflects Switzerland's commitment to participatory democracy and federalism, ensuring that even the Presidency remains aligned with the principles of equality and collaboration within government.

The Swiss Federal Council, as the supreme executive authority, has a number of crucial roles that are fundamental to the functioning and stability of the state. Its primary responsibility is the management of foreign relations, a task that encompasses the direction of Swiss diplomacy. In this role, the Federal Council has historically navigated Switzerland's neutrality on the international stage, as evidenced by its efforts during both World Wars and during the Cold War, when Switzerland maintained a neutral position while being a centre for international negotiations. The Federal Council also plays a key role in formulating and proposing international treaties. These treaties, after being negotiated by the Federal Council, must be approved by the Federal Assembly, thus ensuring democratic control over international agreements. A notable example is Switzerland's accession to the United Nations in 2002, a move that was carefully considered and finally approved both by the government and by popular referendum.

The management of affairs between the Confederation and the cantons is another key responsibility of the Federal Council, reflecting Switzerland's federalist system. This function ensures effective collaboration and coordination between the different levels of government, which is vital for a country with pronounced linguistic and cultural diversity. With regard to the country's security, the Federal Council takes measures for internal and external protection. This includes not only military defence, but also emergency preparedness and civil protection management. Swiss defence policy, characterised by neutrality and a strong tradition of military service, is directed and supervised by the Federal Council. In the legislative sphere, the Federal Council is involved in the preliminary phase of the legislative process, playing a crucial role in preparing draft legislation before it is presented to the Federal Assembly. This stage of the legislative process is essential to ensure that new laws are well conceived and respond effectively to the country's needs. Finally, managing the Confederation's finances is a complex task that requires careful planning and supervision. The Federal Council is responsible for preparing the federal budget and overseeing public spending, ensuring that the State's financial resources are used responsibly. Through these various functions, the Swiss Federal Council demonstrates its vital role in maintaining law and order, promoting economic prosperity, and preserving political stability in Switzerland. Its actions and decisions have shaped the country's course through crucial historical moments and continue to influence its development and place in the world.

The Federal Chancellery

Article 179 of the Swiss Constitution defines the Federal Chancellery as the staff of the Federal Council, placing it at the heart of the Swiss government administration. Headed by the Federal Chancellor, the Federal Chancellery plays a crucial role in supporting and coordinating the activities of the Federal Council. The Federal Chancellery acts as a central administrative and organisational support body for the Swiss government. Its responsibilities include preparing Federal Council meetings, managing documentation and official communications, and supporting interdepartmental coordination. By facilitating the efficient and orderly running of the Federal Council, the Chancellery ensures that government decisions are taken in an informed and organised manner. The Chancellor, as head of the Federal Chancellery, plays an essential role in this process. Although the Chancellor is not a member of the Federal Council and has no decision-making power in government affairs, he or she is responsible for the smooth running of administrative operations and logistical support. This position is crucial to ensuring that the Federal Council functions smoothly and efficiently, allowing Council members to concentrate on their political and decision-making responsibilities.

The Swiss Federal Chancellery, established in 1803, plays a crucial role in Switzerland's system of government. As the staff of the Federal Council, it provides essential administrative and organisational support, contributing to the efficiency and coordination of government activities. A notable aspect of the Federal Chancellery is its participation in the deliberations of the Federal Assembly. Although the Chancellery does not have the power to vote, it does have an advisory vote. This means that the Chancellor and Chancellery staff can provide advice, information and clarification during parliamentary discussions. This contribution is particularly important when it comes to technical or administrative issues relating to the implementation of policies and laws.

The presence of the Federal Chancellery in parliamentary deliberations ensures close liaison between the Federal Council and the Federal Assembly, fostering mutual understanding and effective cooperation between the executive and legislative branches of government. The Chancellery plays a facilitating role, helping to translate political decisions into concrete administrative action and ensuring that government processes run smoothly. Since its creation in the early 19th century, the Federal Chancellery has evolved to meet the changing needs of the Swiss government, but its fundamental role as the nerve centre of the Federal Council and a key partner of the Federal Assembly has remained constant. It is an important pillar in the smooth and efficient functioning of the Swiss political system.

The Chancellor of the Swiss Confederation is appointed by the Federal Assembly. This appointment reflects the importance of this role in the Swiss political system, although the Chancellor does not have the same status or the same powers as a member of the Federal Council. The Chancellor is chosen to work closely with the Federal Council, acting as its administrative staff and providing essential organisational and logistical support. Although the Chancellor is not a full member of the Federal Council and does not participate in the decision-making process with voting rights, his role is nonetheless crucial.

As a participant in Federal Council meetings, the Chancellor has an advisory vote. This means that he or she can offer advice, administrative perspectives and relevant information during discussions, but without participating in the final vote. This contribution is particularly important in ensuring that the Federal Council's decisions and policies are well-informed and administratively feasible. The Chancellor's position, by facilitating communication between the Federal Council and the Federal Assembly and helping to coordinate government activities, is essential to the smooth running of the Swiss executive. Although the Chancellor has no decision-making powers, his role as adviser and organiser within the Swiss government is of great importance for the effective implementation of policies and the management of state affairs.

Swiss Federal Supreme Court

The Swiss Federal Supreme Court occupies a key position in the country's legal system, as the supreme judicial authority of the Confederation. Its creation and development reflect the constitutional and political changes that have shaped modern Switzerland. Originally, the Federal Supreme Court was not a permanent court, its role and structure having evolved over time. It was not until 1874, with the revision of the Federal Constitution, that the Federal Supreme Court was established as a permanent court. This marked an important moment in Swiss judicial history, signifying a strengthening of judicial power at federal level.

The rise of the Federal Supreme Court is closely linked to the increase in the powers of the Swiss Confederation. As powers previously held by the cantons were transferred to the federal level, the need for a supreme judicial authority capable of deciding disputes relating to federal legislation became increasingly apparent. The Federal Supreme Court was given the task of ensuring the uniform interpretation and application of federal law throughout the country.

As the highest judicial body, the Federal Supreme Court deals with civil law, criminal law, public law and disputes between the cantons and the Confederation. It also plays a crucial role in protecting the constitutional rights of Swiss citizens. The creation of a permanent court in 1874 therefore symbolised a turning point in the consolidation of the Swiss federal state and the development of its legal system. This development contributed to the unification of the legal framework in Switzerland and strengthened the rule of law and national cohesion.

Switzerland's federal judicial system is remarkably structured to ensure maximum specialisation and efficiency in the handling of legal cases. At the heart of this system is the Federal Supreme Court, located in Lausanne, which acts as the supreme judicial authority of the Confederation. This supreme court, founded as part of the modernisation of the Swiss state in the 19th century, is the final court of appeal in civil law, criminal law, public law and disputes between the cantons and the Confederation. Its role is crucial to the uniform interpretation of federal legislation and the protection of constitutional rights. In Lucerne, the Federal Insurance Court specialises in social law issues, dealing with cases relating to social security. This court plays an essential role in dealing with legal issues relating to health, accident, disability and old-age insurance, areas that are crucial to the well-being of Swiss citizens. The Federal Criminal Court, located in Bellinzona, specialises in criminal cases under federal criminal law. Inaugurated in the early 2000s, it reflects the need for a centralised and specialised approach to dealing with complex crimes such as terrorism, money laundering and crimes against the state, contemporary challenges that Switzerland, like other nations, must face. Finally, the Federal Patent Court in St. Gallen, established to strengthen the protection of intellectual property in Switzerland, is a key player in the field of patent litigation. This court, which specialises in intellectual property issues, ensures that Switzerland remains a centre of innovation and research by providing a solid legal framework for patent protection.

Each of these courts, with its unique specialisation, contributes to Switzerland's overall judicial structure, ensuring a coherent, fair and efficient approach to justice. This organisation reflects Switzerland's commitment to a robust judicial system that is adapted to the various aspects of modern governance and legal challenges.

Within the Swiss judicial system, the Federal Supreme Court plays a crucial role as the highest judicial authority of the Confederation, particularly in dealing with appeals from cantonal courts. This structure guarantees the highest level of legal scrutiny and control, ensuring uniformity and fairness in the application of Swiss law. When a case is decided in a cantonal court and a party is dissatisfied with the decision, it has the option of appealing to the Federal Supreme Court, subject to certain conditions. Such appeals may concern matters of civil law, criminal law or public law. The Federal Supreme Court then examines the case to ensure that the law has been correctly applied and interpreted by the cantonal courts.

This judicial hierarchy, in which cases can be taken from a cantonal court to the highest federal court, is essential to maintaining the integrity of the Swiss legal system. It not only makes it possible to correct any errors made by the lower courts, but also ensures that the interpretation and application of the law are consistent across the country. By providing this avenue of appeal, the Federal Supreme Court serves as the ultimate guardian of the Swiss law and Constitution, playing a key role in protecting individual rights and maintaining the legal order. This structure reflects Switzerland's deep commitment to the rule of law and fair justice, fundamental values in Swiss society.

Article 147 of the Swiss Constitution highlights a distinctive feature of the Swiss legislative process, known as the consultation procedure. This procedure is a key element of participatory democracy in Switzerland, allowing broad participation by the various players in society in the development of policies and laws. Under this article, the cantons, political parties and interest groups concerned are invited to give their opinion on important legislative acts, on other significant projects during their preparatory phases, and on major international treaties. This consultation practice ensures that these bodies have the opportunity to express their views and contribute to the shaping of policies before they are finalised and adopted. This consultation procedure reflects Switzerland's commitment to inclusive and transparent governance. By seeking the views of the cantons, which play an important role in the Swiss federal system, as well as those of political parties and interest groups, the federal government ensures that regional and sectoral perspectives and concerns are taken into account. This contributes to better policy-making, greater acceptance of legislation and more effective implementation. In the case of international treaties, the consultation procedure is particularly important, as these agreements can have a considerable impact on different aspects of Swiss society. By involving various stakeholders in the review process, Switzerland ensures that its international commitments best reflect national interests and enjoy broad support. In this way, Article 147 of the Swiss Constitution illustrates Switzerland's collaborative and deliberative approach to formulating its policies and laws, an essential pillar of its democracy and system of governance.

At cantonal level

Article 51 of the Swiss Constitution addresses the issue of cantonal constitutions and emphasises the importance of democracy and autonomy at cantonal level, while ensuring their conformity with federal law. According to the first paragraph of this article, each Swiss canton must have a democratic constitution. This requirement reflects the principle of cantonal sovereignty and respect for direct democracy, which are pillars of the Swiss political structure. These cantonal constitutions must be accepted by the people of the canton concerned, which guarantees that the cantonal laws and government structures reflect the will of their citizens. In addition, each cantonal constitution must be capable of being revised if a majority of the canton's electorate so requests, thus ensuring that cantonal laws are flexible and adaptable to the changing needs and wishes of the population. The second paragraph stipulates that the cantonal constitutions must be guaranteed by the Confederation. This guarantee is granted on condition that the cantonal constitutions do not conflict with federal law. This means that, although the cantons enjoy a high degree of autonomy, their constitutions and laws must respect the principles and regulations established at federal level. This provision ensures national cohesion and unity, while respecting cantonal diversity and autonomy.

Article 51 of the Swiss Constitution strikes a balance between cantonal autonomy and respect for the federal legal framework, reflecting the federalist nature of the Swiss state. It guarantees that political and legal structures at cantonal level operate democratically and are in harmony with federal laws and principles.

In Switzerland's federalist system, the interaction between federal law and the cantons is defined by a rigorous framework that ensures that federal laws are applied uniformly and effectively across the country, while respecting the autonomy of the cantons. The cantons cannot apply federal law at their own discretion. They are obliged to follow the guidelines and standards established by federal legislation. This ensures that the laws are implemented consistently across all the Swiss cantons, thereby ensuring the uniformity of the legal and judicial framework at national level.

As part of this responsibility, each canton must designate specific bodies to carry out federal tasks. This means that the cantons are responsible for setting up the authorities and institutions needed to apply federal legislation at local level. These bodies may include cantonal courts, public administrations and other regulatory entities. In addition, the cantons are obliged to create these institutions and bodies in accordance with the requirements and standards defined by federal legislation. This means that cantonal structures must be in line with the fundamental principles and technical specifications of federal legislation, thereby ensuring their effectiveness and legitimacy. This structure reflects the federalist nature of Switzerland, where the cantons enjoy significant autonomy, but within the framework of respect for federal law and order. It allows for effective decentralisation and local governance while maintaining national cohesion and unity within the Confederation.