« The independence of the United States » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 101 : | Ligne 101 : | ||

[[Fichier:Declaration independence.jpg|thumb|center|400px|The presentation of the final text of the declaration to Congress.<br />Table by John Trumbull.]] | [[Fichier:Declaration independence.jpg|thumb|center|400px|The presentation of the final text of the declaration to Congress.<br />Table by John Trumbull.]] | ||

= | =The Declaration of Independence= | ||

Washington's task is not going to be easy. Many of these American settlers are not prepared to enlist to risk their lives in a war. Here comes a man who will allow a decisive step in this movement. He is an Englishman who is radical, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Paine Thomas Paine], which exposes England's predatory nature towards her colonies, describing her as ready to devour her colonies, breaking the taboo of the link with the king and his ministers. He asserts that there is nothing more England can put right, there is nothing left to negotiate, because the English monarchy has gone too far, it is necessary to focus on the American and consider its own future: "the last link is now broken". | |||

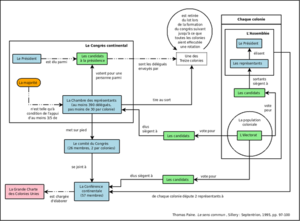

[[Image:Constitution-etats-unis-thomas-paine.png|thumbnail|300px|left|Constitution | [[Image:Constitution-etats-unis-thomas-paine.png|thumbnail|300px|left|Constitution of the United States as proposed by Thomas Paine in "Common Sense", 1776]] | ||

In "Common Sense", he projects the idea that America is the only bastion of freedom on earth. The book sells 120,000 copies for a population of 300,000 including slaves. This shows the high literacy rate and the extraordinary resonance of this pamphlet. | |||

It will sustain the enthusiasm of the Second Congress of Philadelphia at the same time as English troops begin to retreat and abandon the city of Boston. | |||

Delegates from North Carolina, Virginia and Massachusetts put forward a motion to support colonial independence. On July 4, 1776, all the delegates from the Thirteen Colonies adopted a declaration of independence. | |||

According to the declaration, all men were created equal and endowed by their creator with inalienable rights, including life, liberties and the pursuit of happiness. To guarantee these rights, governments must be just and have the consent of the governed. When a government destroys its rights, it is the duty of the governed to form another government and if necessary by revolt. | |||

There follows a long list of 23 attacks and violations of the rights of settlers by the King of England. All these accusations establish that he is basically a Tiran. It goes on to state that the Americans tried everything before responding to England by war to liberate themselves, and that is why "we, the representatives of the United States of America assembled in assembly taking as our witness the supreme judge of the universe, and on behalf of the people and their colonies, publish that the United Colonies are entitled to be free and independent states free from all allegiance to England. The colonies may make peace, enter into alliances, display commerce, and do all that an independent state can do; and in support of this declaration we affirm our allegiance to divine providence.<ref>Déclaration unanime des treize États unis d’Amérique réunis en Congrès le 4 juillet 1776</ref> ». | |||

This is the first time that men have used these ideas to justify the birth of a political entity. | |||

First of all, it is a "men's affair"; women are totally absent, Indians are mentioned among the accusations against the king as "merciless savages" while slaves and slavery are never mentioned. The equality of men declared in the opening is reserved for adult white men. | |||

=Poursuite de la guerre= | =Poursuite de la guerre= | ||

Version du 28 avril 2020 à 11:18

Fac-similé de la Déclaration d'indépendance américaine avec les portraits des signataires.

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

First of all, we will see that the causes of great and small historical events are multiple. We are going to study long-term structural elements that force change and force us to think differently. These interfering events are also called "conjunctural events" appearing at the end of the Seven Years' War (1756 - 1763) that lead to an increased exploitation of the governed while new ideas make their way into the enlightenment with individuals in conditions of power that are not up to the task.

Causes of Independence

First of all, there is the demographic growth which is a long-lasting cause throughout the 18th century due to the high birth rate and the decrease in mortality, but also to immigration, the territory of the United States goes from 300,000 inhabitants in 1700 to 2.5 million in 1770.

This meant greater pressure on the hitherto narrow territory. As with most profound changes, there are several external factors that make it possible to think about the present differently, including England's victory over France in the Seven Years' War (1756 - 1763), which ended with the Treaty of Paris. In the United States, this war is called the war against the French and the Indians. It was a war on the fringe of the West against French forts and territories occupied by Indian nations.

In 1763, the French ceded most of their territories. In addition, England forced Spain, which had been an ally of France, to cede Florida, which then extended to the Mississippi River, to England; it also forced France to cede Louisiana to England. All these changes in colonization were made at the expense of the Amerindian nations, which came out of it very weakened. On the other hand, since the border was little occupied, it was easier to change the dominant without major problems on the territory.

At the end of the Seven Years' War, there is an increase in tensions between the colony and the metropolis. First of all, the government of London impeded settlers' access to Indian territories by signing treaties with Indian chiefs. In spite of everything, the settlers will continue to advance on the Indian territories in part by buying territories in particular from the Cherokees and the Apaches.

England comes out of the war heavily in debt, for the monarch it is the settlers who have benefited the most from the war, that is why it is the settlers who must pay part of this debt through a new tax and stronger customs regulations. This is very badly received in America because these settlers were used to decentralization, to the fact that in each colony it was a legislative assembly made up of locally elected representatives who decided on taxes and their allocations.

London was constantly imposing new taxes and trying to counter American smuggling from New England to Surinam.

It is mainly the expansion of the Stamp Act that will arouse the wrath of the colonists. It's a mail tax that's going to make this literate culture furious. This new tax not decided by the colonial assemblies is an attack on the system of representation that exists, against economic progress and the freedom of the colonies; some shout conspiracy against the welfare of the colonies.

Some of the educated men echoed Locke's ideas that the role of the state is to bring welfare and security to individuals with inalienable rights to life, liberty and property.

Response of the colonies

The settlers petitioned and refused to obey; on the other hand, they launched boycotts of taxed products and even used violence against British officers. The first major episode in this rise of violence was the "Boston Massacre" which takes place in 1770 in which English soldiers kill five demonstrators.

The other big event is the "Tea Party" which also took place in December 1773 in Boston, where Bostonians very curiously disguised as Indians boarded an English ship carrying tea from the East India Company and threw the cargo of tea into the sea because it was competing unfairly with American importers.

British reaction

London's reaction will be to punish Boston by imposing the Coercive Acts in 1774. The Coercive Acts blockaded and closed the port of Boston to all trade, imposed the King's authority over the colony of Massachusetts so that the Legislative Assembly no longer had any power, and transferred to England trials that could lead to the death penalty, while all of the Thirteen Colonies were obliged to house British troops in their own homes. The entire colonial administration was affected.

Decisive steps towards independence

Little by little, all the colonies will show their solidarity with Boston. It is the beginning of mutual aid and nationalism, which is done by defending besieged Bostonians.

In September 1774, delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies met in the first continental congress held in Philadelphia. During this congress, the delegates declare Coercive Acts illegal, inviting the colonists to form defense militias.

This does not mean that all American settlers follow the movement, many continue to support England, they are called "Loyalists", while others protest and sign petitions, but are not prepared to take up arms that would threaten their economic interests.

In Philadelphia, some went from activism against the king to rejection by the British parliament; however, at that point they continued to be loyal to the king. Loyalty to the king is still very much alive. However, the King of England Georges III is not up to the task, proving unable to cope with events.

The other thing to note is that most delegates and members, whether moderate or radical, come from the wealthiest families in the territory. They are mostly merchants, lawyers, a few craftsmen and others, but at heart they are mostly merchants, planters, the aristocracy of these 13 colonies.

In order to obtain the support of the population, they mobilized the merchants of the time, lawyers, skilled workers, craftsmen and taverns. However, these leaders are not revolutionaries, they want to overthrow the local hierarchy in order to regain their local power which collapses with the Coercive Acts.

It is only in 1775 that the settlers take up arms at Lexington, making Massachusetts the cradle of independence; this occurred following incidents with British troops and American militiamen that resulted in further deaths.

At that time, a Second Continental Congress is meeting in Philadelphia. It is there that the decision is made to form an army to defend the colonies against the British, which will be entrusted to George Washington.

The delegates choose Washington because he's patriotic, committed, rich with slaves and plantations. In the minds of the delegates, if one is rich, one is incorruptible because one will not want to get richer, especially since he is a man from Virginia, therefore from the South, with the idea of expanding the movement that has taken place until now, especially in the North.

With the election of a man from Virginia, the idea is that the union of the Thirteen Colonies will really be manifested.

The Declaration of Independence

Washington's task is not going to be easy. Many of these American settlers are not prepared to enlist to risk their lives in a war. Here comes a man who will allow a decisive step in this movement. He is an Englishman who is radical, Thomas Paine, which exposes England's predatory nature towards her colonies, describing her as ready to devour her colonies, breaking the taboo of the link with the king and his ministers. He asserts that there is nothing more England can put right, there is nothing left to negotiate, because the English monarchy has gone too far, it is necessary to focus on the American and consider its own future: "the last link is now broken".

In "Common Sense", he projects the idea that America is the only bastion of freedom on earth. The book sells 120,000 copies for a population of 300,000 including slaves. This shows the high literacy rate and the extraordinary resonance of this pamphlet.

It will sustain the enthusiasm of the Second Congress of Philadelphia at the same time as English troops begin to retreat and abandon the city of Boston.

Delegates from North Carolina, Virginia and Massachusetts put forward a motion to support colonial independence. On July 4, 1776, all the delegates from the Thirteen Colonies adopted a declaration of independence.

According to the declaration, all men were created equal and endowed by their creator with inalienable rights, including life, liberties and the pursuit of happiness. To guarantee these rights, governments must be just and have the consent of the governed. When a government destroys its rights, it is the duty of the governed to form another government and if necessary by revolt.

There follows a long list of 23 attacks and violations of the rights of settlers by the King of England. All these accusations establish that he is basically a Tiran. It goes on to state that the Americans tried everything before responding to England by war to liberate themselves, and that is why "we, the representatives of the United States of America assembled in assembly taking as our witness the supreme judge of the universe, and on behalf of the people and their colonies, publish that the United Colonies are entitled to be free and independent states free from all allegiance to England. The colonies may make peace, enter into alliances, display commerce, and do all that an independent state can do; and in support of this declaration we affirm our allegiance to divine providence.[1] ».

This is the first time that men have used these ideas to justify the birth of a political entity.

First of all, it is a "men's affair"; women are totally absent, Indians are mentioned among the accusations against the king as "merciless savages" while slaves and slavery are never mentioned. The equality of men declared in the opening is reserved for adult white men.

Poursuite de la guerre

La guerre va continuer jusqu’en 1781, souvent ce sera des combats de guérilla. Les troupes américaines, dirigées par Washington, compteront entre 4000 et 7000 hommes. Par contre, l’Angleterre aura jusqu’à 35 000 hommes, dont un certain nombre venant de Russie.

Les Anglais lancent deux appels aux esclaves pour qu’ils fuient leurs maitres et se joignent aux troupes anglaises contre une promesse de liberté. Ils vont servir dans l’armée, mais le plus souvent comme main d’œuvre, peu gagneront leur liberté à fin de la guerre.

La fin de la guerre est accélérée par l’entrée de la France du côté des indépendantistes. C’est une aide en provenance de la France loyaliste de Louis XVI pour une revanche sur l’Angleterre. L’aide arrivera en 1780 avec 6000 hommes sous les ordres du comte de Rochambeau. De nombreux de ces hommes viendront d’Haïti et de Saint-Domingue.

L’aide française sera décisive, car elle contribue à la capitulation de la Grande-Bretagne après la bataille de Yorktown qui signifie la capitulation de l’Angleterre menant à la reconnaissance de l’indépendance des États-Unis en septembre 1783 par un traité de paix à Paris.

Dès lors, les frontières ne vont pas cesser de s’élargir.

En fait, la guerre commence en 1776 et se finit en 1781 et l’Angleterre ne reconnait l’indépendance qu’en 1783. En comparaison aux autres indépendances, c’est un processus rapide.

Révolution ou réaction ?

Aux États-Unis, l’indépendance est appelée « the American Revolution ». Tous les historiens ne sont pas d’accord avec cela, c’est un débat qui continue depuis deux siècles.

Pour les tenants de la thèse de la révolution, cette indépendance représente une coupure radicale des Américains dans le contexte monarchique de l’époque parce que ce n’était pas seulement une réaction contre l’Empire britannique, mais cela détruit tous liens avec la monarchie traditionnelle. La relation entre État et société est complètement bouleversée et projette les « États-Unis ».

Pour ceux qui soutiennent une réaction conservatrice, ce qui est l’origine de tout cela est une tentative des Américains de rétablir les libertés qu’ils avaient avant et notamment les libertés de commerce ; ce serait un mouvement qui aurait cherché à reprendre ce qui existait.

Les deux interprétations ont du vrai.

Pour avoir une révolution, il faut :

- mobilisation massive de la population ;

- luttes entre différentes idéologies ;

- lutte concrète pour le pouvoir ;

- transformation profonde des structures sociales et économiques.

En ce qui concerne les Treize colonies des États-Unis, on a les trois premiers points, mais pas vraiment le quatrième alors qu’en ce qui concerne Saint-Domingue et Haïti on constate l’ensemble de ces éléments.

Dans le cadre des États-Unis, la mobilisation est faible, d’autre part, à la fin de la guerre il n’y a pas véritablement de bouleversement de la société et des structures ; ce sont les mêmes qui continuent à gouverner, tandis que le servage demeure et explose.

Il n’en demeure pas moins que la nouvelle nation innove sur bien des plans :

- c’est le premier pays indépendant des Amériques ;

- les États-Unis adoptent un système républicain et fédéraliste ;

- l’idée de noblesse héréditaire est rejetée.

Cependant, on est loin d’une démocratie, car pour les politiciens, le peuple est le bas peuple, et la démocratie renvoie au désordre et la violence.

Les délégués, lors de la convention constitutionnelle, vont s’affronter dans la conception d’un gouvernement légitime qui doit représenter la volonté des gouvernés avec notamment la question clef de qui pourra voter.

Ce nouveau pays en s’appelant les États-Unis d’Amérique s’approprie le nom d’Amérique et devient très vite, pour les habitants de ces anciennes colonies, « The America ». C’est une appropriation qui se fait au grand damne des Américains lorsqu’ils vont obtenir leur indépendance.

Annexes

- Photographie interactive de la déclaration

- Site des Archives nationales américaines

- Bibliothèque Jeanne Hersche

- Hérodote.net

- Transatlantica, revue d'études américaines. Dossier spécial sur la Révolution, dirigé par Naomi Wulf.

- Nova Atlantis in Bibliotheca Augustana (Latin version of New Atlantis)

- Barnes, Ian, and Charles Royster. The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution (2000), maps and commentary excerpt and text search

- Blanco, Richard L.; Sanborn, Paul J. (1993). The American Revolution, 1775–1783: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-0824056230.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo III (1974). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (2 ed.). New York: Charles Scribners and Sons. ISBN 978-0684315133.

- Cappon, Lester J. Atlas of Early American History: The Revolutionary Era, 1760–1790 (1976)

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Richard A. Ryerson, eds. The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History (5 vol. 2006) 1000 entries by 150 experts, covering all topics

- Gray, Edward G., and Jane Kamensky, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution (2013) 672 pp; 33 essays by scholars

- Greene, Jack P. and J. R. Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2004), 777 pp – an expanded edition of Greene and Pole, eds. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (1994); comprehensive coverage of political and social themes and international dimension; thin on military

- Herrera, Ricardo A. "American War of Independence" Oxford Bibliographies (2017) annotated guide to major scholarly books and articles online

- Kennedy, Frances H. The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook (2014) A guide to 150 famous historical sites.

- Purcell, L. Edward. Who Was Who in the American Revolution (1993); 1500 short biographies

- Resch, John P., ed. Americans at War: Society, Culture and the Homefront vol 1 (2005), articles by scholars

- Symonds, Craig L. and William J. Clipson. A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution (1986) new diagrams of each battle

- Works by Thomas Paine

- Common Sense - Thomas Paine (ouvrage complet en anglais)

- Deistic and Religious Works of Thomas Paine

- The theological works of Thomas Paine

- The theological works of Thomas Paine to which are appended the profession of faith of a savoyard vicar by J.J. Rousseau

- Common Sense by Thomas Paine; HTML format, indexed by section

- Rights of Man

References

- ↑ Déclaration unanime des treize États unis d’Amérique réunis en Congrès le 4 juillet 1776