« The system of government in democracies » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| (7 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 9 : | Ligne 9 : | ||

{{hidden | {{hidden | ||

|[[Introduction to Political Science]] | |[[Introduction to Political Science]] | ||

|[[ | |[[Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory]] ● [[The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic]] ● [[Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory]] ● [[The notion of "concept" in social sciences]] ● [[History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts]] ● [[Marxism and Structuralism]] ● [[Functionalism and Systemism]] ● [[Interactionism and Constructivism]] ● [[The theories of political anthropology]] ● [[The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas]] ● [[Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science]] ● [[An analytical approach to institutions in political science]] ● [[The study of ideas and ideologies in political science]] ● [[Theories of war in political science]] ● [[The War: Concepts and Evolutions]] ● [[The reason of State]] ● [[State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance]] ● [[Theories of violence in political science]] ● [[Welfare State and Biopower]] ● [[Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes]] ● [[Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences]] ● [[The system of government in democracies]] ● [[Morphology of contestations]] ● [[Action in Political Theory]] ● [[Introduction to Swiss politics]] ● [[Introduction to political behaviour]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation]] ● [[Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations]] ● [[Introduction to Political Theory]] | ||

|headerstyle=background:#ffffff | |headerstyle=background:#ffffff | ||

|style=text-align:center; | |style=text-align:center; | ||

| Ligne 40 : | Ligne 40 : | ||

The term "government" can be used in a number of ways, depending on the context. Here are some common uses: | The term "government" can be used in a number of ways, depending on the context. Here are some common uses: | ||

* Government as an executive entity: In this sense, "government" often refers to | * Government as an executive entity: In this sense, "government" often refers to individuals with the power to make executive decisions in a state. This generally includes the head of state (e.g. a president or monarch), the head of government (e.g. a prime minister), and other members of the cabinet or council of ministers. | ||

* Government as an institution: In this sense, "government" | * Government as an institution: In this sense, "government" refers to the entire system a state runs. This includes not only the executive branch, but also the legislative branch (e.g. parliament) and the judicial branch (e.g. the courts). | ||

* Government as a specific administration: Sometimes the term "government" | * Government as a specific administration: Sometimes the term "government" refers to a specific set of people who run a state at a given time. For example, we might speak of the "Biden government" in the United States or the "Johnson government" in the United Kingdom to refer to the administration currently in power. | ||

The exact meaning of the term 'government' may vary depending on the context. When | The exact meaning of the term 'government' may vary depending on the context. When discussing politics, it is important to be clear about the term's meaning. | ||

== Legislative power | == Legislative power == | ||

In this system, parliament, as the elected legislative body, is at the heart of the political process. The | In this system, parliament, as the elected legislative body, is at the heart of the political process. The party or coalition usually forms the government with the greatest parliamentary support, and is accountable to parliament. | ||

Here's how it usually works: | Here's how it usually works: | ||

| Ligne 107 : | Ligne 107 : | ||

This role of the judiciary helps to maintain a balance between the different powers of the State and to ensure that the legislative and executive powers respect the Constitution and fundamental rights. | This role of the judiciary helps to maintain a balance between the different powers of the State and to ensure that the legislative and executive powers respect the Constitution and fundamental rights. | ||

The courts, | The courts, particularly the constitutional or supreme courts, are increasingly influential in many countries, including the United States. One example is the Affordable Care Act, commonly known as 'Obamacare', signed into law by President Obama in 2010. One of the key provisions of this law was the 'individual mandate', which required almost all Americans to take out health insurance or pay a fine. This provision was challenged before the US Supreme Court, which had to determine whether Congress had the constitutional power to impose it. In 2012, in NFIB v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court ruled that the individual mandate was constitutional but interpreted the penalty associated with the mandate as a tax, meaning that Congress had the power to impose it under its constitutional power to levy taxes. This decision had a major impact on US healthcare policy and illustrates the increasingly important role played by the courts in influencing public policy. However, it should be noted that this influence may vary according to the specific political context and the way in which the judiciary is structured and regulated in each country. | ||

== The role of the Head of State | == The role of the Head of State == | ||

The title of "head of state" is not reserved exclusively for elected presidents. The head of state is the person who officially represents a country in international affairs and state ceremonies, and the exact role and powers associated with this position can vary considerably depending on the country's specific political system. Here are some examples of the different types of Head of State that exist: | The title of "head of state" is not reserved exclusively for elected presidents. The head of state is the person who officially represents a country in international affairs and state ceremonies, and the exact role and powers associated with this position can vary considerably depending on the country's specific political system. Here are some examples of the different types of Head of State that exist: | ||

* Monarchs: In a monarchy, the head of state is usually a king or queen. In an absolute monarchy, the monarch has considerable political power, whereas in a constitutional monarchy, the monarch is usually | * Monarchs: In a monarchy, the head of state is usually a king or queen. In an absolute monarchy, the monarch has considerable political power, whereas in a constitutional monarchy, the monarch is usually other institutions, such as parliament and the prime minister hold a figurehead with limited powers and real political power. | ||

* Presidents: In a republic, the head of state is usually a president. However, the exact role and powers of the president can vary. In a presidential system, the president is usually both head of state and head of government, with considerable political power. In a parliamentary system, the President is often a figurehead with limited powers, and the real political power | * Presidents: In a republic, the head of state is usually a president. However, the exact role and powers of the president can vary. In a presidential system, the president is usually both head of state and head of government, with considerable political power. In a parliamentary system, the President is often a figurehead with limited powers, and the Prime Minister holds the real political power. | ||

* Governors General: In some Commonwealth countries, the Head of State is a Governor General who represents the British monarch. The Governor General generally has limited powers and performs mainly ceremonial functions. | * Governors General: In some Commonwealth countries, the Head of State is a Governor General who represents the British monarch. The Governor General generally has limited powers and performs mainly ceremonial functions. | ||

* Unelected leaders: In certain situations, the head of state may be a person who has not been elected, for example following a coup d'état or in an authoritarian regime. | * Unelected leaders: In certain situations, the head of state may be a person who has not been elected, for example following a coup d'état or in an authoritarian regime. | ||

| Ligne 202 : | Ligne 202 : | ||

Each member of the Federal Council heads a department of the Swiss government, and decisions are taken jointly. There is no hierarchy between the Federal Councillors. Each year, a different member of the Federal Council serves as President of the Confederation, but this role is largely ceremonial and involves no additional power. It is a system that aims to promote cooperation and consensus, rather than political rivalry. It is also a way of ensuring that Switzerland's different linguistic and cultural regions are represented at government level. | Each member of the Federal Council heads a department of the Swiss government, and decisions are taken jointly. There is no hierarchy between the Federal Councillors. Each year, a different member of the Federal Council serves as President of the Confederation, but this role is largely ceremonial and involves no additional power. It is a system that aims to promote cooperation and consensus, rather than political rivalry. It is also a way of ensuring that Switzerland's different linguistic and cultural regions are represented at government level. | ||

= | = Government formation = | ||

The study of government formation is essential to understanding how a political system works, how power is distributed and how political decisions are made. Here are some specific reasons why it is important: | |||

* | * Understanding the balance of power: The way a government is formed can show how power is distributed between different entities, such as the president, parliament, prime minister, etc. It can also help to understand how these entities interact with each other. | ||

* | * Study political stability: The mechanisms of government formation can influence political stability. For example, some systems may lead to unstable coalition governments, while others may allow one party or individual to hold excessive power. | ||

* | * Assessing representation: Government formation can affect the representation of different social groups, political parties or regions of the country within government. | ||

* | * Analysing government effectiveness: Some systems of government formation can promote effectiveness by avoiding political deadlocks, while others can hamper the decision-making process. | ||

* | * Comparing political systems: By studying how governments are formed in different countries, we can better understand and compare their political systems. This can help us to identify the strengths and weaknesses of different systems and to propose political reforms. | ||

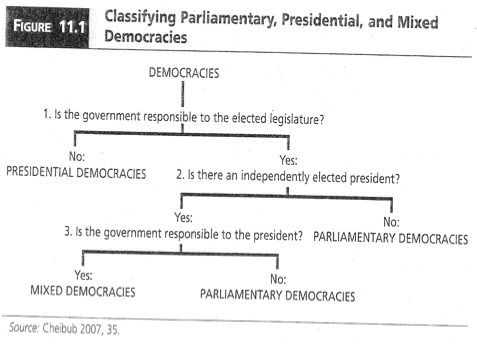

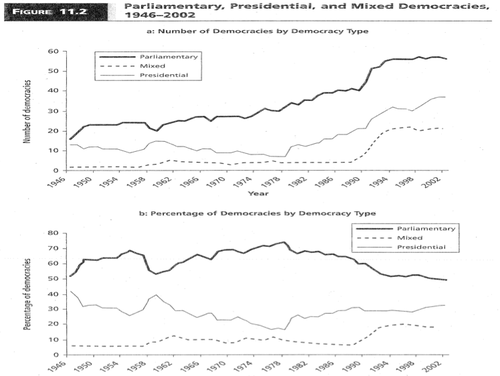

The study of government formation is crucial to understanding the nature and functioning of democracy in different contexts. Government formation varies according to the political system and the type of democracy in place in a country. | |||

* | * Parliamentary democracy: In general, after an election, the party that has won the majority of seats in parliament has the opportunity to form the government. If no party has won a majority, parties can join together to form a governing coalition. The leader of the majority party or coalition usually becomes Prime Minister. | ||

* | * Presidential democracy: The president is elected separately from parliament and has the authority to appoint members of the executive, who are often called ministers or secretaries in different countries. These appointments may sometimes require parliamentary approval. | ||

* | * Semi-presidential or mixed democracy: Here, power is shared between a president and a prime minister. The president is usually elected by the people, while the president appoints the prime minister but must have the confidence of parliament. | ||

Each of these systems has its own advantages and disadvantages in terms of the balance of power, stability of government, representation of minorities and so on. It should be noted that even within these systems, there are many variations and specific processes for forming government may vary from country to country. | |||

== | == Parliamentary democracies == | ||

In a parliamentary democracy, the main role in forming the government falls to the Prime Minister, who is usually the leader of the party or coalition that won the most seats in parliament at the elections. The Prime Minister is responsible for choosing the members of the cabinet. These members, who are usually parliamentarians from the same party as the Prime Minister, take on specific roles as ministers in different areas of public policy. | |||

However, the Prime Minister must also take into account a series of constraints when forming the government. He must strive to maintain unity and cohesion within his own party, especially if there are factions or internal disputes. In addition, if the Prime Minister heads a coalition government - which is common in parliamentary systems where no party has won an absolute majority in elections - he or she must also take into account the interests and demands of his or her coalition partners. | |||

Balancing these different constraints is a key element in the survival and success of a government in a parliamentary democracy. If the Prime Minister loses the confidence of parliament - for example, following a vote of no confidence - his government may be forced to resign. | |||

Understanding the terms is essential to understanding the formation and functioning of a government in a parliamentary system. | |||

* | * Ministerial responsibility" is the principle that a minister is responsible for the actions and decisions taken in his or her department. This means that a minister can be held accountable for his or her actions and can be asked to resign if his or her actions are deemed to be inappropriate or harmful. | ||

* | * Collective cabinet responsibility" is the principle that all members of the cabinet must publicly support and defend decisions taken by the cabinet, even if they disagree with them in private. This collective responsibility is essential to maintain the unity and cohesion of the government. | ||

* | * The "vote of investiture" is a vote that takes place in Parliament after a new government has been formed. In this vote, parliamentarians vote to approve or reject the new government. If the government wins the approval of the majority of parliamentarians, it is officially sworn in and can begin its duties. | ||

* | * The "formateur" is a person responsible for forming a government after an election, particularly when the result of the election is uncertain or when no party has obtained an absolute majority. The formateur is often the future Prime Minister, but in some constitutional monarchies, the monarch may appoint a formateur. This person has the task of negotiating between the different political parties to form a government that will be able to win an investiture vote in Parliament. | ||

The configuration of a government can take several forms depending on the election results and the political dynamics in a parliamentary system. Here is a brief explanation of each type mentioned: | |||

* ''' | * '''Single-party government''': In this configuration, a single party has won the majority of seats in parliament in the elections, allowing it to form a government without the need to ally itself with other parties. The party in power thus has total control of the government. | ||

* ''' | * '''Government coalitions''': If no party has won an absolute majority in the elections, several parties may decide to join forces to form a government coalition. This configuration requires negotiations and compromises between the parties in the coalition. | ||

* ''' | * '''Super-majority government''': This is a form of coalition government in which the majority is so large that it far exceeds the minimum needed to control the government. This super-majority can be used to pass constitutional reforms which generally require a qualified majority. | ||

* | * Minority government'': This is a situation in which the party or coalition leading the government does not control the majority of seats in parliament. In order to pass legislation, the minority government often has to negotiate with other parties. This is generally an unstable situation that can lead to new elections if the government fails to maintain parliamentary support. | ||

=== | === One-party government === | ||

In a one-party system of government, citizens do not directly elect the Prime Minister or cabinet members. In most parliamentary systems, citizens vote for a political party and the leader of that party usually becomes prime minister if he or she can form a government, usually by having a majority of seats in parliament. | |||

The single ruling party can choose cabinet members from its own ranks, without the need for a direct public vote for these positions. This means that the choice of cabinet members can be largely influenced by internal party dynamics and the will of the party leader. | |||

It is important to note that although the term 'single party' is used here to describe a situation where a single party dominates the government, in many contexts the term 'single party' is also used to describe undemocratic political systems where a single party is allowed to exist or exercise unchecked dominance over the political system. | |||

In a parliamentary system, when a single party wins a majority of seats in parliament at an election, it then has the ability to form a government on its own. The leader of this party is usually appointed Prime Minister. In these cases, there is no need to negotiate with other parties to form a coalition, which can facilitate the process of forming a government and make the government more stable once it is formed. This is what is often described as a one-party government. | |||

However, it is quite common for no single party to win a majority of seats. In these situations, the parties have to negotiate with each other to form a coalition government. These negotiations can be complex and time-consuming, as they often involve compromises on policies and the allocation of ministerial posts. | |||

The choice to form a coalition rather than a single-party government can be influenced by a variety of factors, such as the desire for a more representative government, the need to maintain political stability, or the preference for a certain configuration of power within the government. | |||

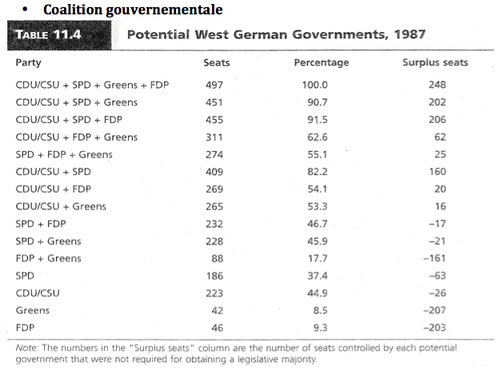

=== | === Government coalition === | ||

A coalition government is formed when two or more parties come together to form a government. This usually occurs in parliamentary systems when no single party receives a majority of seats in an election. | |||

The formation of a coalition government usually involves negotiations between the parties on policies and the allocation of ministerial posts. These negotiations can be complex and time-consuming, as they often involve compromises. Once formed, the governing coalition must work together to govern, despite any ideological or political differences that may exist between the parties in the coalition. | |||

There are different types of governing coalitions, including minority coalitions, where several minority parties come together to form a government; majority coalitions, where two or more parties have enough seats to form a majority in parliament; and grand coalition coalitions, where a country's two largest parties come together to form a government. | |||

It is important to note that the stability and effectiveness of a governing coalition can vary considerably depending on the specific dynamics between the parties in the coalition, as well as the wider political context. | |||

[[Fichier:Coalition gouvernementale 1.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | |||

In a parliamentary system such as Germany's, when no party wins an absolute majority of seats in parliament at an election, it is necessary to form a governing coalition. This generally involves the party that has won the most seats (the "majority party") inviting other parties to join them in forming a government. This table shows all the possible combinations of parties that could form a coalition government, based on the results of the 1987 election. These combinations are based on the number of seats each party won and the potential political compatibility of the parties. | |||

The office-seeking and policy-seeking model is commonly used to analyse the behaviour of political parties, particularly in the context of government coalitions. | |||

* Office-seeking: Office-seeking parties are primarily interested in executive power - that is, they seek to obtain ministerial posts, and therefore to control certain departments or sectors of the public administration. They may be prepared to make concessions on their political positions to achieve this objective. In terms of office-seeking, political parties seek to maximise their representation in government, which means obtaining as many ministerial posts as possible. The aim is therefore to be part of a coalition that has a sufficient majority to govern, but with no more parties than necessary. This is known as a "minimum winning coalition". The idea behind a minimum winning coalition is that it allows each party in the coalition to have a greater influence on government policy. The more parties there are in a coalition, the more the influence of each party is diluted, as they have to share power with more partners. In addition, the objective of "making the least collation", or forming a coalition with the lowest number of surplus seats, stems from the desire to avoid sharing power with more parties than necessary. The more surplus seats there are in a coalition, the more likely it is that a coalition party will be able to leave the coalition without bringing it down. This could give that party additional bargaining power and therefore dilute the influence of the other parties in the coalition. However, forming coalitions is often a complex process, where not only the distribution of seats has to be taken into account, but also the compatibility of policies and relations between the parties. | |||

* Policy-seeking parties: Policy-seeking parties, on the other hand, are primarily interested in implementing their preferred policies. From a policy-seeking perspective, parties seek ministerial posts not only to increase their representation, but also to have a direct influence on government policy. In this way, they can help to steer government policy in a direction that is consistent with their ideological goals and values. For example, a left-wing party may seek the post of Minister for Social Affairs in order to influence policy towards greater state intervention in the economy and social welfare. Similarly, a right-wing party may seek the post of Minister for the Economy in order to promote policies that favour the free market and minimise state intervention in the economy. However, as with office-seeking, the formation of coalitions from a policy-seeking perspective is a complex process, requiring account to be taken not only of the number of seats held by each party, but also of their ideological compatibility and mutual relations. | |||

In reality, most parties seek both executive power and the implementation of their policies, but their priority may vary according to various factors, such as the size of the party, its ideology, the nature of the electoral system, or the specific political context. To form a coalition government, it is often necessary to strike a balance between these two objectives: a party that seeks only power risks being seen as opportunistic and losing the confidence of its voters, while a party that seeks only to implement its policies may find itself excluded from power if it is not prepared to compromise. | |||

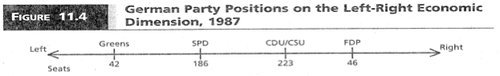

The table below shows the ideological position of various German political parties on a scale from left to right, according to their vision of state intervention in the economy. The political left generally advocates a more interventionist state in the economy. This can include policies such as redistribution of wealth, increased public spending on welfare and public services, regulation of business to protect workers and the environment, and sometimes public ownership of certain sectors of the economy. The political right, on the other hand, often advocates a more minimalist state in economic matters. This can include policies such as reducing taxes and public spending, liberalising markets and reducing business regulation, and promoting private ownership and individual enterprise. | |||

[[Fichier:Coalition gouvernementale 2.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Coalition gouvernementale 2.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | ||

It makes perfect sense to seek to form a "connected" or "contiguous" coalition in politics. Parties that sit close together on the political spectrum tend to have similar worldviews and policies. As a result, they are likely to work more effectively together and have fewer internal conflicts. These coalitions are often more stable than those that bring together parties from different parts of the political spectrum, as it is easier for ideologically close parties to agree on policies. They are also likely to have similar support bases, which can facilitate communication and engagement with the public. | |||

In the process of forming a coalition, political parties often negotiate with each other to gain the support they need to achieve a majority. These negotiations may involve concessions on various issues, such as the political programme, key government posts, or specific policies to be implemented. In this context, the large parties often have an advantage because of their greater number of seats in parliament. They have more leverage in negotiations and may be able to demand greater concessions from other parties. However, these negotiations are often complex and can involve a delicate balance between seeking the support needed to form a coalition and preserving the party's political integrity and priorities. For this reason, coalition building can be a complex and sometimes lengthy process. It requires skills in negotiation, diplomacy and compromise, as well as a good knowledge of the politics and priorities of each party involved. | |||

===Super-majority and minority governments=== | |||

A super-majority government is a government that is supported by a broad coalition of parties that together hold a large majority of seats in parliament. A super-majority is often required for certain important constitutional decisions. In this type of government, power is generally shared between several parties, which can lead to a policy of compromise. This is the case, for example, in Finland, where super-majority governments are common. | |||

On the other hand, a minority government is a government formed by a party or coalition of parties that does not have a majority of seats in parliament. This type of government generally has to rely on the support of parties outside the coalition to pass legislation. These governments are often unstable and may have difficulty implementing their political programme. However, they are sometimes the only option in the absence of a clear majority in parliament. Examples of such governments can be found in many countries, including Sweden, Denmark and Canada. | |||

The choice between these different types of government often depends on the specific constitutional rules of each country, as well as the political context and the composition of parliament after the elections. | |||

The formation of super-majority governments or minority governments that do not respect the "least minimum winning coalition" (LMWC) principle can be explained in several ways: | |||

* Stability imperatives: In certain situations, broader coalitions can be formed to guarantee political stability. A super-majority government can withstand the instability that can be caused by internal disagreements within a party or fluctuations in popular support. | |||

* Support for major reforms: Major constitutional or structural reforms may require wider majorities than those provided for in the LMWC. In such cases, a super-majority government may be necessary. | |||

* Ideological considerations: Sometimes political parties prefer to work with parties that share their values and objectives, even if they could form a government with fewer partners. | |||

* Default minority government: In some situations, it may be impossible to form a majority coalition, either because of ideological divisions or because no party wants to work with another. In such cases, a minority government may be the only viable option. | |||

* Non-coalition cooperation: A minority government can also sometimes receive "outside" support from parties outside the coalition, which may allow the government to survive even if it does not form a majority. | |||

* Political strategy: Sometimes, forming a minority government can be a strategic decision. For example, a party may prefer to run a minority government on its own rather than share power within a majority coalition. | |||

These factors show that while the LMWC principle is a useful tool for understanding how governments are formed, it cannot explain every situation. Politics is complex and is influenced by a multitude of factors that go beyond simple majority calculations. | |||

[[Fichier:Gouvernement de super-majorité et gouvernement de minorité1.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | |||

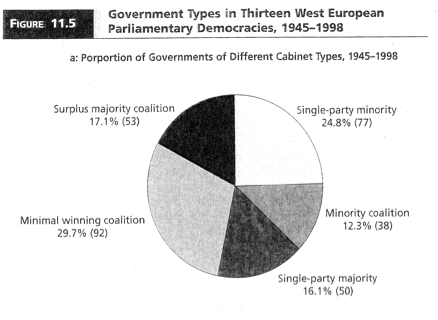

In the table analysing types of government in thirteen Western European parliamentary democracies from 1945 to 1998, minority governments accounted for 38% of cases. Significantly, in countries such as Denmark, Sweden and Norway, minority governments were the norm rather than the exception. Specifically, Denmark had a minority government for 88% of the period, Sweden for 81% and Norway for 66%. This underlines the fact that political dynamics in parliamentary democracies are complex and vary considerably from country to country. In some countries, such as Denmark, Sweden and Norway, minority governments appear to be more common. | |||

This can be explained by several factors. In these countries, there may be greater political and public acceptance of minority governments. This may be facilitated by a political culture that values consensus and cooperation between different political parties, even when they are not part of the same government. In addition, these countries may have a tradition of political parties that are prepared to support a minority government on key issues, even if they are not officially members of the government. This may allow a minority government to govern effectively without having a formal majority in parliament. Finally, political parties in these countries may be more willing to form a minority government for strategic reasons. For example, they may prefer to run a minority government rather than make significant concessions to form a majority coalition. | |||

However, it is important to note that despite the prevalence of minority governments, these countries are still considered to be stable and effective democracies. This suggests that the stability and effectiveness of a government depends not only on its formal majority in parliament, but also on other factors such as political culture, the quality of democratic institutions, and the willingness of political parties to work together for the common good. | |||

=== | === Explaining the super-majority phenomenon === | ||

Super-majority governments are coalitions in which the parties in government hold a share of seats well in excess of the simple majority required. They are generally formed in a context of political or economic uncertainty, when the parties in power wish to have a broader mandate to take important or controversial decisions. | |||

There are several reasons why a super-majority government might be formed: | |||

# | # Government stability: A super-majority government may be more stable and resilient in the face of opposition or internal dissent. It may be better able to push through policies without fear of a vote of no confidence or other forms of parliamentary gridlock. | ||

# | # Political consensus: A super-majority government can reflect a broad consensus on some important policy issues, especially where difficult or unpopular decisions need to be made. | ||

# | # Emergency or crisis context: In the event of a crisis, such as war or economic emergency, a super-majority government can be formed to demonstrate national unity and facilitate rapid and effective decision-making. | ||

# | # Electoral uncertainty: A super-majority government can be a strategy to guard against electoral uncertainty. In the event of early elections, a super-majority government would have a better chance of staying in power. | ||

# Influence | # Influence on policy: By including more parties in government, it is possible to achieve a broader consensus on policy, which can help to facilitate its implementation. | ||

However, it should be noted that forming a super-majority government can also have disadvantages, such as reduced political accountability and the potential for abuse of power. In addition, managing such a government can be difficult due to the diversity of interests and ideologies represented. | |||

A super-majority government, sometimes called a government of national unity, brings together more parties than are needed to control a parliamentary majority. It therefore exceeds the minimum threshold for a governing majority, thus incorporating a "super-majority" of members of parliament. | |||

This usually occurs in times of serious crisis, such as war, major natural disaster, severe economic crisis, or any other situation that requires a unified national response. The aim is to bring different parties and viewpoints together to work towards a common goal, putting aside, at least temporarily, partisan differences. This can lead to more stable and resilient governments, able to make decisions and act quickly in response to the crisis. | |||

Sometimes a government may seek to form a super-majority for strategic reasons, such as when it is necessary to pass constitutional amendments or other types of legislation requiring a super-majority (usually a two-thirds majority) in parliament. In such cases, it may be necessary to form alliances with additional parties to gain the necessary support. | |||

On the other hand, a super-majority government can help guard against blackmail from smaller parties. In a smaller coalition government, a small party may be able to exert a disproportionate influence if it is in a position to swing the majority. By forming a super-majority, the government can guard against this risk by ensuring that it has sufficient support to maintain a majority even if one or more small parties withdraw from the coalition. This can contribute to political stability and the government's ability to implement its programme. | |||

=== | === Understanding the existence of minority governments === | ||

There are several reasons why a minority government can form. Here are a few of them: | |||

# | # Failure to form a majority coalition: Sometimes, after an election, no single party or possible coalition of parties holds a majority of seats in parliament. If the parties cannot agree to form a majority coalition, a minority government may be formed. | ||

# | # Instability of coalitions : In some cases, a minority government may be preferable to an unstable coalition. For example, a majority party might decide to form a minority government rather than ally itself with an unreliable coalition partner. | ||

# | # Tacit support or "tolerance" from other parties: A minority government can also survive with the tacit support of parties that are not officially part of the governing coalition. These parties may choose to "tolerate" the minority government by abstaining from confidence votes, thus allowing the government to survive even without a formal majority. | ||

# | # Countries with a tradition of minority governments: In some countries, minority governments are relatively common and accepted as a normal form of governance. For example, in countries such as Denmark and Sweden, minority governments are quite common. | ||

# | # Emergency or crisis situations: Sometimes, in emergency or crisis situations, a minority government may be formed as a temporary solution before elections can be held or a more stable majority coalition formed. | ||

Minority governments can be formed in different ways. Here are more details on these two forms: | |||

# ''' | # '''Single-party government''': A single-party minority government occurs when the party forming the government does not have a majority in parliament. This can happen if no party has won enough seats to gain a majority in the elections, and no coalition has been formed. Despite their minority, this party can form a government and try to govern by relying on flexible and changing alliances with other parties to gain support on specific issues. | ||

# ''' | # '''Government formed on the basis of coalitions''': Sometimes a group of parties may decide to form a coalition to govern together, even if they do not together have a majority of seats in parliament. In this case, the minority coalition government will attempt to govern by seeking the support of other parties or independent MPs to pass legislation and make decisions. | ||

In both cases, the minority government usually has to work with other parties to gain the support it needs to pass legislation and take political decisions. This can involve political negotiations and compromises. Sometimes minority governments may also depend on the tacit support or 'tolerance' of other parties, who choose not to vote against the government in confidence votes. | |||

A minority government depends on the support, usually implicit, of other parties in order to function. This is sometimes called "tolerance" or "tacit support". In practice, this means that although these parties are not officially part of the government, they choose to support it in key votes, such as votes of confidence or votes on the budget. They may do so for a variety of reasons: for example, they may support the government because they agree with some of its policies, or because they want to avoid another election. | |||

In the case of a minority government, parties that choose to support the government without participating directly in it have significant influence. They have the opportunity to negotiate support for specific issues or policies in exchange for their continued support for the government. This can lead to situations where the government must constantly consult and compromise with these parties to ensure that it continues to have their support. However, this dynamic can also create challenges for the government. For example, if it is constantly negotiating with several different parties, this can make decision-making slower and more complicated. What's more, if one party decides to withdraw its support, this can lead to a government crisis and potentially to new elections. This is why, although a minority government can sometimes work effectively, many countries prefer to have a stable majority government, where a single party or coalition of parties has direct control of the majority of seats in parliament. | |||

Take the Netherlands, for example, where a minority government has been formed by two parties, the Liberal Party and the Christian Democratic Party. A far-right party, although it has not officially joined the coalition, has declared its support for these two parties. In other words, this far-right party gave tacit support to the coalition government, even though it was not officially part of the government. This is an excellent example of how a minority government can work. In this case, the two parties forming the government (the Liberals and the Christian Democrats) do not control a majority of seats in parliament. However, they were able to govern thanks to the support of the far-right party. The far-right party, although not officially part of the government, therefore has a significant influence on government policy. In exchange for their support, they are likely to have been able to negotiate certain concessions on policies or issues that are important to them. However, this kind of arrangement can be unstable. If the far-right party decides to withdraw its support, this could lead to a government crisis. In addition, constantly having to negotiate with an outside party can make government decision-making more complicated and slower. | |||

Minority governments play a crucial role in the dynamics of politics and the functioning of parliamentary systems. To understand why and how these governments form, several hypotheses have been proposed. These hypotheses aim to identify the conditions that make the emergence of minority governments more likely, and to explain the mechanisms underlying these processes. | |||

First, the opposition strength hypothesis suggests that the formation of minority governments depends on the strength of the opposition in parliament. Second, the corporatism hypothesis suggests that the existence of corporatist institutions may favour the formation of minority governments. Third, the investiture vote hypothesis postulates that the presence of a formal investiture vote in parliament can make minority governments less problematic. Finally, the fourth hypothesis highlights the role of strong parties, arguing that minority governments are more likely in a system where there is a dominant party. Each hypothesis will be examined in more detail to understand how they contribute to the formation of minority governments. | |||

*''' | *'''The strength of the opposition is a key factor in the formation of minority governments''': the stronger the opposition, the more likely it is that a minority government will be formed. The 'strength' of the opposition is determined by the level of participation of opposition parties in parliamentary committees. The greater the presence of these opposition parties on these committees, the greater their influence on government power. As a result, their interest in joining the government may be reduced, as they already have the opportunity to influence policy from the outside. | ||

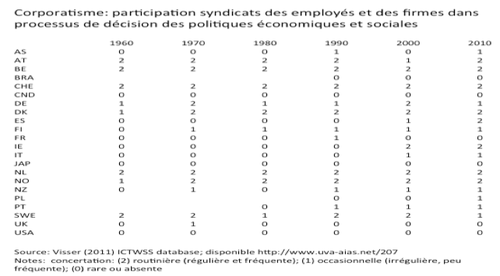

*''' | *'''Corporatism''': this hypothesis postulates that corporatism, a system in which social and economic actors can have a formal influence on the decision-making process, can affect the opposition's ability to influence. In other words, in a corporatist system, opposition parties could have a greater capacity to influence policy, which could, in turn, affect the formation of minority governments. This could mean that in systems with corporatist-type institutions, opposition parties might be better able to support a minority government without needing to be formally part of the government. | ||

[[Fichier:Gouvernement de super-majorité et gouvernement de minorité2.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Gouvernement de super-majorité et gouvernement de minorité2.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | ||

What is the causal mechanism behind this hypothesis? Corporatism enables social and economic players to participate actively in the decision-making process. In this context, power and influence are not concentrated solely within the ministerial cabinet. Opposition parties have the opportunity to exert significant influence through other institutional bodies. The causal mechanism behind this hypothesis is as follows: in a corporatist structure, opposition parties can influence the political decision-making process without necessarily being part of the government. This may reduce the need to be part of a majority government in order to have an impact. As a result, it could increase the likelihood of minority governments being formed, as opposition parties can still influence policy without being part of government. Thus, they may choose to support a minority government from the outside, rather than seeking to join a majority government. | |||

*''' | *'''Nomination vote''': this hypothesis suggests that minority governments are less problematic when there is a formal nomination vote in parliament. The underlying causal mechanism is the distinction between formal support for a government and tolerance of it. In a system where there is a formal nomination vote, a political party can formally vote against a government, while choosing to tolerate it in practice. This means that a party may not openly support a government in a public vote, but may choose not to obstruct its operation or overthrow it. This is a way for a party to express its disagreement with the government without provoking a political crisis. This situation can facilitate the formation of minority governments, as they do not need the formal support of a majority in parliament to survive. As long as they are tolerated by enough parties to avoid a successful no-confidence vote, they can continue to govern. Consequently, the existence of a formal nomination vote could increase the likelihood of minority governments being formed. | ||

*''' | *'''strong party''': this hypothesis suggests that minority governments are more likely in a political system where there is a dominant or strong political party. The causal mechanism behind this hypothesis is based on the balance of power between political parties in a given system. In a system where there is a strong party, it is possible that this party does not have enough seats to form a majority government on its own, but nevertheless remains the largest party in parliament. In this case, even if it forms a minority government, the other smaller parties may be unable to unite to overthrow that government and form an alternative majority. In essence, the presence of a strong party can create a situation where, although it is technically in a minority in parliament, it is still the most capable of forming and maintaining a stable government. Moreover, the other parties may choose to tolerate this minority government rather than risk the instability that could result from an attempt to form an alternative government. | ||

Does empirical analysis support these hypotheses? | |||

* | * Regarding the strength of the opposition, some research has shown that minority governments are more likely to form when the opposition is stronger, in line with the first hypothesis. | ||

* | * With regard to corporatism, the results are mixed. Some studies found a correlation between the presence of corporatist institutions and the formation of minority governments, while others found no significant link. | ||

* | * Nomination voting seems to play an important role in the formation of minority governments, as the third hypothesis suggests. Minority governments tend to be more stable in parliamentary systems where a nomination vote is required. | ||

* | * Finally, the presence of strong parties also seems to play a role in the formation of minority governments. Several studies have found that minority governments are more frequent in systems with one or two dominant parties. | ||

[[Fichier:Gouvernement de super-majorité et gouvernement de minorité3.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Gouvernement de super-majorité et gouvernement de minorité3.png|500px|vignette|centré]] | ||

This table is a statistical analysis that relates various independent variables (such as the strength of the opposition, corporatism, the nomination vote, the presence of strong parties) to a dependent variable (the formation of minority governments). The table shows that the stronger the opposition, the more minority governments there are. This suggests that hypothesis 1, concerning the strength of the opposition, has some degree of validity. In such an analysis, controlling for other variables allows us to control for their potential impact on the dependent variable. This helps to isolate the effect of the independent variable of interest (in this case, the strength of the opposition) on the dependent variable (the formation of minority governments). | |||

When is a minority government formed? | |||

When the dependent variable is binary (i.e. takes two possible values, such as "1" for the formation of a minority government and "0" otherwise), a logistic regression analysis is used. The regression coefficient in this model indicates how the probability of the event (i.e. the formation of a minority government) changes with a unit of change in the independent variable, which in this case is the strength of the opposition in the parliamentary committees. If the coefficient is positive, this means that an increase in the strength of the opposition in parliamentary committees increases the probability of the formation of a minority government, which supports hypothesis 1 mentioned earlier. The standard error, on the other hand, is a measure of the variability or uncertainty around the estimate of the regression coefficient. It is used to construct confidence intervals around the estimated coefficient and to test hypotheses about the value of this coefficient. | |||

The empirical analysis seems to corroborate the first three hypotheses: | |||

* | * The strength of the opposition is a determining factor in forming minority governments. The stronger the opposition, the more likely it is that minority governments will be formed. | ||

* | * Corporatism influences the opposition's ability to act. By guaranteeing access to the decision-making process, corporatist institutions dilute the cabinet's power and allow opposition players to influence other bodies. | ||

* | * Minority governments are less problematic when there is a formal vote of investiture in parliament. The vote of investiture makes it possible to differentiate between formal support for a government and tacit tolerance. | ||

However, the analysis does not support the fourth hypothesis, according to which minority governments are more likely in a political system with a strong party. In sum, while the first three hypotheses appear to provide a useful framework for understanding the formation of minority governments, the fourth hypothesis may require further revision or analysis. | |||

== | == Presidential democracies == | ||

Presidential democracies are political systems in which the head of state is also the head of government. This differs from parliamentary democracies, where the head of government is separate from the head of state. The United States is an example of a presidential democracy. | |||

In a presidential democracy, the president is elected directly by the people and is not accountable to parliament. This can lead to a situation of cohabitation, where the president and the parliamentary majority belong to different political parties. The president generally has the power to appoint and dismiss members of his cabinet at his discretion. | |||

Presidential democracies have advantages and disadvantages. The advantages include a degree of stability, as the president is generally in office for a fixed term and is not subject to overthrow by a motion of no confidence from parliament. The disadvantages include the risk of excessive concentration of power in the hands of one person and the possibility of tension between the president and parliament. | |||

In a presidential democracy, the government is generally made up of the president and his cabinet. The cabinet is made up of the secretaries or ministers who head the various agencies and departments of the government. The president, as head of government, generally has the power to appoint and dismiss members of his cabinet. These appointments may sometimes require the approval of the Senate or another chamber of parliament, depending on the country's specific system. In addition, the President is the Head of State and Head of Government, which means that he or she is responsible for executing laws, directing foreign policy and the military, and representing the country abroad. | |||

In presidential systems, the formation of government is quite different from that of parliamentary systems for several reasons: | |||

* | * Lack of accountability of the government to parliament: Unlike parliamentary systems, where the government must maintain the confidence of parliament, in presidential systems the president and his administration are not accountable to parliament. This means that even if members of his own party vote against him, this will not bring down the government, but it could hamper the implementation of his policies. | ||

* | * No need for a parliamentary majority: The President does not need a majority in parliament to form his government. This contrasts with parliamentary systems, where the head of government is usually the leader of the party with the most seats in parliament. | ||

* | * Clarity of government formation: In presidential systems, the elected president is automatically the government-former. He directly appoints his cabinet and senior civil servants. This contrasts with parliamentary systems, where the process of forming a government can be more complex and depends on negotiations between the parties. | ||

* | * Guaranteed presence of the President's party: The President's party is always represented in the cabinet, regardless of its parliamentary size. This is because the President has the power to appoint the members of his cabinet directly. | ||

These structural differences have significant implications for the way politics works in presidential versus parliamentary systems. For example, they can affect the type of policy that is adopted, the degree of political stability, and the nature of the relationship between the president and parliament. | |||

== | == Semi-parliamentary democracy == | ||

A semi-parliamentary democracy is a type of system of government that blends elements of parliamentary and presidential democracy. It is often used to describe systems in which both the head of state and the head of government have important but distinct roles in the political process. | |||

In a semi-parliamentary democracy, the head of state (sometimes called the president) is usually a largely symbolic figure who embodies the continuity of the state and may have important ceremonial functions. The head of state may be elected by the people, as in France, or be a monarch, as in Spain. On the other hand, the head of government (sometimes called the prime minister) is responsible for the day-to-day running of the government and the implementation of policies. He or she is usually the leader of the party with the majority in parliament and is responsible to that parliament. In this system, it is possible to have a president and a prime minister from different political parties, which can lead to a situation known as "cohabitation". Cohabitation occurs when the president and prime minister belong to opposing political parties and are therefore forced to work together to govern. | |||

In a semi-parliamentary democracy, the prime minister and the president are part of the government and are involved in the day-to-day management of the state's affairs. The division of labour between the President and Prime Minister may vary from country to country, but as a general rule, the President concentrates on foreign affairs, while the Prime Minister manages domestic affairs. This is the case in France, for example. In this context, the President is generally responsible for representing the country internationally, overseeing defence and security policy, and sometimes appointing the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister, on the other hand, is responsible for domestic policy, including areas such as the economy, health, education and the environment. He is also often responsible for leading the parliamentary majority and managing the government cabinet. Italy, Finland and Portugal are also examples of semi-parliamentary democracies. In these countries, the head of state (the president) and the head of government (the prime minister or equivalent) share executive responsibilities, but the distribution of these responsibilities may vary according to the specific constitutional features of each country. | |||

Cohabitation is a political phenomenon that occurs in a semi-presidential system when the President of the Republic and the parliamentary majority belong to different political parties. This leads to a situation where the President has to appoint a Prime Minister from the opposing majority, which can sometimes lead to political tension. Cohabitation has been particularly visible in France under the Fifth Republic. There have been three periods of cohabitation: the first between President François Mitterrand and Prime Minister Jacques Chirac (1986-1988), the second between President Mitterrand and Prime Minister Édouard Balladur (1993-1995), and the third between President Jacques Chirac and Prime Minister Lionel Jospin (1997-2002). During these periods of cohabitation, the President's role generally focused on foreign affairs and defence, while the Prime Minister played a more active role in the conduct of domestic policy. | |||

The term "divided government" is commonly used in the United States to describe a situation where the President is from one political party and at least one of the houses of Congress (the House of Representatives or the Senate) is controlled by the other party. This is a common situation in the American political system and can lead to political stalemates, where it is difficult for the President to advance his legislative agenda. One of the reasons why 'divided government' can occur is that elections for the House of Representatives are held every two years, while the President and Senators are elected for four- and six-year terms respectively. As a result, the composition of Congress can change midway through a presidential term, which can lead to a loss of majority for the president's party. | |||

= Annexes = | = Annexes = | ||

| Ligne 420 : | Ligne 424 : | ||

[[Category:science-politique]] | [[Category:science-politique]] | ||

[[Category:Damian Raess]] | [[Category:Damian Raess]] | ||

Version actuelle datée du 7 juillet 2023 à 10:47

Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory ● The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic ● Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory ● The notion of "concept" in social sciences ● History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts ● Marxism and Structuralism ● Functionalism and Systemism ● Interactionism and Constructivism ● The theories of political anthropology ● The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas ● Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science ● An analytical approach to institutions in political science ● The study of ideas and ideologies in political science ● Theories of war in political science ● The War: Concepts and Evolutions ● The reason of State ● State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance ● Theories of violence in political science ● Welfare State and Biopower ● Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes ● Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences ● The system of government in democracies ● Morphology of contestations ● Action in Political Theory ● Introduction to Swiss politics ● Introduction to political behaviour ● Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy ● Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation ● Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation ● Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations ● Introduction to Political Theory

There are three main recognised democratic systems in the world. These are political structures that allow citizens to participate in the governance of their country, usually through elections.

- Parliamentary democracy: In this system, executive power is held by a cabinet, usually headed by a prime minister. This cabinet is supported, or "backed", by the majority of members of parliament. The head of state (who may be a monarch or president) generally has a more symbolic or ceremonial role. The United Kingdom and Germany, for example, are examples of parliamentary democracies.

- Presidential democracy: In this system, the president is both head of state and head of government. The president is generally elected directly by the people and exercises both executive and, in some cases, legislative functions. The United States and Russia, for example, are examples of presidential democracies.

- Semi-presidential democracy (or mixed democracy): This system is a combination of the previous two. There is a president elected directly by the people, but there is also a prime minister and cabinet who are accountable to parliament. The president generally has significant powers and responsibilities, but the prime minister and cabinet also exercise executive functions. France and Portugal, for example, are examples of semi-presidential democracies.

The actual practice of democracy can vary considerably even among countries that share the same nominal system. Various factors, such as political culture, history, legal system and constitutional framework, can influence how these systems work in practice.

Constitutional elements of systems of government[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In a democratic system, there are usually three main branches of government: the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. However, some analyses and structures may divide or consider additional powers. Here is a brief description of each traditional power:

- Executive: Responsible for implementing and enforcing laws. It generally comprises the head of state (president or monarch), the head of government (prime minister in some systems), the cabinet and the bureaucracy.

- Legislative branch: Responsible for creating laws. It is generally made up of elected members of parliament or deputies, sometimes organised into two chambers (such as the House of Representatives and the Senate in the United States).

- Judiciary: Responsible for interpreting and applying laws in the event of disputes. It is generally made up of judges and courts.

In some political systems, the role of the Head of State can be seen as a "fourth estate", separate from the traditional executive, legislative and judicial branches.

- In a parliamentary democracy, the head of state (often a monarch or president) often has a symbolic or ceremonial role, but may have specific powers, such as the ability to dissolve parliament, appoint the prime minister, or give royal or presidential assent to legislation.

- In a presidential democracy, the President is both Head of State and Head of Government, combining executive power and the "fourth estate".

- In a semi-presidential democracy, the head of state (the president) and the head of government (the prime minister) share executive power. The president generally has significant powers, such as directing foreign and defence policy, appointing the prime minister and ministers, and sometimes dissolving parliament.

The precise nature of the powers of the head of state varies greatly from country to country, and depends on the constitution and political traditions of the country. In some cases, the head of state may have considerable powers, even in a parliamentary system. In other cases, the role of the head of state may be mainly symbolic or ceremonial.

The term "government" can be used in a number of ways, depending on the context. Here are some common uses:

- Government as an executive entity: In this sense, "government" often refers to individuals with the power to make executive decisions in a state. This generally includes the head of state (e.g. a president or monarch), the head of government (e.g. a prime minister), and other members of the cabinet or council of ministers.

- Government as an institution: In this sense, "government" refers to the entire system a state runs. This includes not only the executive branch, but also the legislative branch (e.g. parliament) and the judicial branch (e.g. the courts).

- Government as a specific administration: Sometimes the term "government" refers to a specific set of people who run a state at a given time. For example, we might speak of the "Biden government" in the United States or the "Johnson government" in the United Kingdom to refer to the administration currently in power.

The exact meaning of the term 'government' may vary depending on the context. When discussing politics, it is important to be clear about the term's meaning.

Legislative power[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In this system, parliament, as the elected legislative body, is at the heart of the political process. The party or coalition usually forms the government with the greatest parliamentary support, and is accountable to parliament.

Here's how it usually works:

- Parliament sets the broad policy direction: This is done through legislation. Members of parliament (MPs, senators, etc.) propose, debate and vote on laws. These laws establish the general rules and guiding principles of government policy.

- The government implements these policies: The government's role is to execute the laws and policies established by parliament. This includes setting regulations, managing public services, and making decisions within the framework of existing laws.

In practice, however, the separation of powers is not always so clear-cut. For example, in many parliamentary systems, the Prime Minister and other members of the government are themselves members of parliament, which can lead to a degree of fusion of legislative and executive powers. In addition, the government can often have a significant influence on the legislative agenda, for example by proposing bills.

Over time, and particularly since the second half of the twentieth century, many have noted a reversal of roles: it now seems that it is governments that drive decision-making, with parliament essentially content to ratify them. This reflects a trend noted by many political scientists, known as the 'presidentialisation' or 'executivisation' of political systems, even in parliamentary democracies. There are several reasons for this development. Here are a few of them:

- Increasing complexity of government policy: As society and the economy evolve, government policy has become increasingly complex, requiring technical expertise and rapid decision-making that the parliamentary legislative process can struggle to provide.

- Crises and emergencies: Economic crises, armed conflicts, pandemics and other emergencies can require swift and decisive action, giving the executive more power.

- Media coverage of politics: Media attention often focuses on the head of government (e.g. the prime minister or president), reinforcing his or her political importance and relative power compared to parliament.

However, although the relative power of government has increased, parliament remains a crucial institution in a democracy. It retains the power to legislate, to scrutinise the government (for example, through questions, debates, committees of enquiry, etc.) and, in many systems, to overthrow the government by a vote of no confidence. The balance between government and parliament varies from country to country and can change over time, depending on factors such as political traditions, the constitution, public opinion and the political context.

On the other hand, there is a general consensus about the decline of legislative power, particularly in parliamentary systems. The executive has become stronger and more independent of parliament, governing with a parliamentary majority that is generally in its favour. The notion of a decline in legislative power vis-à-vis the executive in parliamentary systems refers to several trends observed since the second half of the 20th century. These trends have contributed to strengthening the role of the executive (typically the Prime Minister and his cabinet) relative to parliament. Here are some of the key elements of this phenomenon:

- Concentration of power in the hands of the executive: In many countries, the government has acquired more power to set the political and legislative agenda. This means that the government often plays a decisive role in proposing legislation, while parliament plays a more reactive role.

- Favourable parliamentary majority: In many parliamentary systems, the government is formed by the party (or coalition of parties) that holds the majority of seats in parliament. This means that the government can generally count on the support of the parliamentary majority to approve its legislative proposals. This situation can reduce the role of parliament to that of a rubber-stamp body, rather than a forum for independent debate and decision-making.

- Empowerment of the executive: Over time, the executive has become more independent of parliament. For example, the head of government (often the prime minister) often has greater power to choose cabinet members, set government policy and represent the country abroad.

- Influence of the bureaucracy and experts: With the increasing complexity of public policy, the executive can rely more on the bureaucracy and experts to develop policy, thereby reducing the role of parliament.

However, despite these trends, parliament remains a central institution in a democracy. It has the power to legislate, to scrutinise government action and, in many systems, to overthrow the government by a vote of no confidence. In addition, mechanisms such as parliamentary committees can play an important role in scrutinising legislative proposals and overseeing the administration.

There are various responsibilities and functions generally assigned to a parliament in a democratic system. These "traditional roles" have been established over centuries of political and constitutional history, and although there may be variations depending on the country and the specific political system, they remain broadly similar. Parliaments in democratic systems fulfil a number of fundamental roles, including :

- Legislation: Parliaments have the power to propose, debate and vote on legislation. However, parliamentary room for manoeuvre can vary. In some systems, particularly where the government has a solid parliamentary majority, party voting discipline may limit the ability of parliamentarians to amend legislative proposals.

- Government oversight: Parliaments also have a role in overseeing and controlling government action. This can take several forms:

- Questions to government: Members of parliament can ask questions of the government, often during question time or oral or written questions.

- Interpellation: MPs may question the government on specific subjects, which may give rise to a debate in the assembly. In some systems, this can also include a vote of no confidence which, if passed, can bring down the government.

- Parliamentary committees: Parliaments usually have a number of specialised committees which examine legislative proposals in specific areas and oversee the government's activities in these areas.

These roles of parliament are essential to ensure the democratic accountability of government, and to ensure that laws and government policies respond to the needs and concerns of citizens.

Executive power[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The assertion that the executive branch holds the main political power in modern democracy may be debatable depending on the specific political context, but in many cases it is a fairly accurate observation. Here are some of the reasons why the executive can be considered to have a central role:

- Management of the affairs of state: The executive branch is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the state and the enforcement of laws. This means that it has considerable influence on how policies are implemented and on the daily lives of citizens.

- Political leadership: In many political systems, the leader of the executive (e.g. the President or Prime Minister) is often seen as the political leader of the country. This can reinforce their role and influence.

- Role in legislation: Although legislative power is traditionally associated with parliament, in many systems the executive also has an important role in the legislative process, for example by proposing draft legislation.

- Crisis response: In the event of a crisis (for example, war, natural disaster or pandemic), the executive is usually responsible for the immediate response, which may temporarily increase its power.

However, in a healthy democracy, the power of the executive is balanced by other institutions, notably parliament (which has the power to legislate and control the government) and the courts (which have the power to interpret the constitution and laws). This helps prevent abuses of power and ensures that the government acts in the interests of all citizens.

In a parliamentary system, the government is usually formed by the party (or coalition of parties) that holds the majority of seats in parliament. This means that, in most cases, the government can expect its proposals to be approved by parliament, as it enjoys the support of the parliamentary majority. However, it is important to note that even in a parliamentary system, the government can sometimes face opposition within its own party or coalition, or be forced to negotiate with other parties to gain the necessary support. In a presidential system, on the other hand, the president is usually elected separately from the legislature, and does not need a majority in parliament to remain in power. This can mean that the president has to negotiate with parliament to get his proposals through, and he may have to face a parliament controlled by an opposing party - a situation known as 'divided government'.

There are also differences in terms of accountability. In a parliamentary system, the government is accountable to parliament, and can be overthrown by a vote of no confidence. In a presidential system, the president generally remains in office for the full term, except in exceptional circumstances (such as impeachment proceedings), and is directly accountable to the electorate. However, the effectiveness of these systems can vary depending on many factors, including the specific political context, political culture, electoral system and constitution.

The judiciary[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The judiciary, and more specifically the Constitutional Court or equivalent in many countries, plays an essential role in reviewing the constitutionality of laws. This process is often referred to as "constitutionality review". Here's how it works:

- Interpretation of the Constitution: Constitutional Court judges are responsible for interpreting the Constitution and other fundamental texts to determine their meaning and application.

- Examination of laws: When a law is challenged as being potentially unconstitutional, it is up to the Constitutional Court to examine the law and determine whether it complies with the Constitution.

- Invalidation of unconstitutional laws: If the Constitutional Court determines that a law is unconstitutional, it may invalidate it. This means that the law can no longer be applied because it contradicts the Constitution.

- Protection of fundamental rights: By examining the constitutionality of laws, the Constitutional Court plays a crucial role in protecting fundamental rights. If a law is found to be unconstitutional because it violates these rights, its invalidation by the Court ensures that these rights are respected.

This role of the judiciary helps to maintain a balance between the different powers of the State and to ensure that the legislative and executive powers respect the Constitution and fundamental rights.

The courts, particularly the constitutional or supreme courts, are increasingly influential in many countries, including the United States. One example is the Affordable Care Act, commonly known as 'Obamacare', signed into law by President Obama in 2010. One of the key provisions of this law was the 'individual mandate', which required almost all Americans to take out health insurance or pay a fine. This provision was challenged before the US Supreme Court, which had to determine whether Congress had the constitutional power to impose it. In 2012, in NFIB v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court ruled that the individual mandate was constitutional but interpreted the penalty associated with the mandate as a tax, meaning that Congress had the power to impose it under its constitutional power to levy taxes. This decision had a major impact on US healthcare policy and illustrates the increasingly important role played by the courts in influencing public policy. However, it should be noted that this influence may vary according to the specific political context and the way in which the judiciary is structured and regulated in each country.

The role of the Head of State[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The title of "head of state" is not reserved exclusively for elected presidents. The head of state is the person who officially represents a country in international affairs and state ceremonies, and the exact role and powers associated with this position can vary considerably depending on the country's specific political system. Here are some examples of the different types of Head of State that exist: