The beginnings of the contemporary international system: 1870 - 1939

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Ludovic Tournès[1][2][3] |

| Cours | Introduction to the history of international relations |

Lectures

- Perspectives on the studies, issues and problems of international history

- Europe at the centre of the world: from the end of the 19th century to 1918

- The era of the superpowers: 1918 - 1989

- A multipolar world: 1989 - 2011

- The International System in Historical Context: Perspectives and Interpretations

- The beginnings of the contemporary international system: 1870 - 1939

- World War II and the remaking of the world order: 1939 - 1947

- The international system in the test of bipolarisation: 1947 - 1989

- The post-Cold War system: 1989 - 2012

The period from 1870 to 1939 saw the emergence of the contemporary international system, characterised by the rise of the nation state and the development of multilateral diplomacy. This period was also marked by growing tensions between the great powers and major conflicts such as the First World War. The Congress of Vienna in 1815 had established a European system of multilateral diplomacy that had succeeded in keeping the peace in Europe for over half a century. However, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the rise of Germany marked the end of this system. The international system that emerged after 1870 was dominated by the great European powers, notably Germany, France, Britain and Russia. These states sought to establish alliances and maintain a balance of power to avoid war. However, the emergence of Germany as a great power led to an arms race that eventually resulted in the First World War. After the war, the League of Nations was created to preserve international peace. However, the weakness of the League of Nations, combined with the rise of totalitarian regimes in Europe, led to the Second World War.

The order of nation-states

The nation-state order is an international system in which states are considered the main actors in the international arena and are organised as distinct and sovereign political communities. This system emerged in the 19th century as a result of liberal and nationalist revolutions in Europe and was consolidated by the Treaties of Westphalia in 1648, which established the principle of state sovereignty. In the nation-state order, each state is considered equal in law and sovereign over its territory. This means that each state has the power to make independent decisions about its internal and external affairs, and that these decisions cannot be challenged by other states. The nation-state order has been characterised by strong competition between states for power, security and resources, as well as the search for international recognition and legitimacy. This competition has often led to conflicts and wars between states. However, the nation-state order has also fostered international cooperation, especially in the economic sphere. States have created international organisations to regulate trade and economic relations between nations, such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The nation-state order is an international system in which states are the main actors, organised into distinct and sovereign political communities. Although it has fostered competition between states, it has also allowed for international cooperation, particularly in the economic sphere.

The Westphalian system

The Westphalian system refers to the Treaties of Westphalia signed in 1648 at the end of the Thirty Years' War in Europe. These treaties established a new political order in Europe, characterised by the recognition of state sovereignty and the establishment of a system of international relations between states. Before the Westphalian system, Europe was a patchwork of kingdoms, empires and principalities, each with shifting borders and often in conflict with each other. The Treaty of Westphalia enshrined the principle of state sovereignty, recognising each state as an independent entity with a territory, a population and a sovereign government. The Westphalian system also established a system of international relations based on diplomacy and negotiation between sovereign states. States began to establish diplomatic relations and sign treaties to regulate their mutual relations, such as trade treaties, peace treaties and military alliances. This system was consolidated by the birth of nation-states in the 19th century, which reinforced the sovereignty and national identity of states. Thus, the Westphalian system is seen as the foundation of modern international relations, with the assertion of nation-states as the main actors on the international scene.

The Thirty Years' War was a period of decline for the Holy Roman Empire, which was then the dominant empire in Central Europe. The war considerably weakened the Holy Roman Empire, which lost much of its territory and population, and saw its political and military power diminish. The Holy Roman Empire was established in 962 AD by Emperor Otto I, who sought to restore the power of the Roman Empire in Western Europe. The empire's ambition was to become a universal monarchy, uniting all the peoples of Europe under a single ruler. However, this ambition came up against the political reality of medieval Europe, characterised by a high degree of political fragmentation and the existence of numerous independent kingdoms and principalities. The Holy Roman Empire therefore had to deal with this reality and developed into a confederation of sovereign territories, headed by an elected emperor. The Thirty Years' War was a turning point in the history of the Holy Roman Empire, as it revealed the limits of its power and influence. At the end of the war, Emperor Ferdinand II was forced to recognise the independence of Switzerland and the United Provinces, and had to grant greater autonomy to the German princes. This marked the end of the idea of a universal monarchy in Europe, and paved the way for the emergence of nation-states, which became the main players on the international scene from the 19th century onwards. Thus, the Thirty Years' War helped to shape the history of Europe and to lay the foundations of the contemporary international system.

The Holy Roman Empire continued to exist until 1806, when it was dissolved by Napoleon Bonaparte. However, by the 17th century, the empire had already lost much of its power and political influence. During this period, the empire faced many challenges, including religious conflicts between Catholics and Protestants, rivalries between German princes and the rise of France under Louis XIV. The Holy Roman Emperor also lost much of his power and authority, and was often reduced to a symbolic role. The German states began to assert themselves as independent political entities, strengthening their sovereignty and autonomy from the empire. This led to a political fragmentation of Germany, with many sovereign states, each with its own government and politics. This fragmentation made it difficult to establish a coherent foreign policy for Germany, and favoured the emergence of foreign powers such as France and Britain. Although the Holy Roman Empire continued to exist until the 19th century, it lost much of its political influence in the 17th century, leaving room for the emergence of new political entities in Europe.

The end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648 and the signing of the Treaties of Westphalia marked the beginning of a period of decline in the temporal power of the Catholic Church. In the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church had considerable influence on the political and social life of Europe, and was considered the second universal power after the Roman Empire. The Church was a key player in international relations, and played an important role in resolving conflicts between states. However, the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century had challenged the authority of the Catholic Church, putting forward the idea of a religion based on the Bible alone and rejecting the Catholic hierarchy. The Reformation led to a division of Europe into Catholic and Protestant countries and weakened the Catholic Church. The end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648 marked the beginning of a period of decline for the Catholic Church. The Treaties of Westphalia confirmed the separation of church and state and ended the religious war in Europe. This separation limited the temporal power of the Church, confining it to a primarily religious role. In addition, the Enlightenment period in the 18th century challenged the authority of the Church, emphasising reason and science rather than religion. Enlightenment ideas led to a gradual secularisation of society, and further weakened the political influence of the Church. Thus, from the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648, the political role of the Catholic Church gradually diminished and it refocused on its religious role. This development contributed to the emergence of the modern nation-state, in which religion no longer plays a central role in political and social life.

The principles of the Westphalian system are based on several foundations that have ensured the stability of the international system for several centuries.

- The first of these principles is that of the balance of the great powers. The aim is to maintain a balance of power in Europe, so that one power does not seek to dominate the others. This implies that the European powers must balance each other out in terms of military, economic and political power.

- The second principle is that of the inviolability of national sovereignty. This principle is symbolised by the formula "cuius regio, eius religio" ("like prince, like religion"). According to this principle, each prince is free to decide on the religion of his state, and the population adopts the religion of its prince. This principle also implies that each state is sovereign over its own territory, and that other states have no right to interfere in its internal affairs.

- The third principle is that of non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. States are sovereign on their own territory, and have no right to interfere in the internal affairs of other states. This principle underpins the idea of national sovereignty, which is one of the fundamental principles of the Westphalian system.

The principles of the Westphalian system are based on the balance of great powers, the inviolability of national sovereignty, and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. These principles have ensured the stability of the international system for several centuries, and are still widely respected today.

The Treaty of Westphalia marked a turning point in European history by ending the Thirty Years' War and laying the foundations for the modern international system. The treaty recognised states as the main actors on the international scene, putting an end to the idea of a universal monarchy embodied by the Holy Roman Empire. In addition, the political role of the Roman Catholic Church was considerably reduced, with the emphasis on national sovereignty and the inviolability of state borders. Thus, the Treaty of Westphalia marked the end of the supremacy of the Church in political affairs and strengthened the role of states in international relations. The Treaty of Westphalia was a key moment in European history, marking the birth of the state system and the decline of the ambitions of the Church and the Holy Roman Empire. The treaty laid the foundations for an international system based on respect for national sovereignty and the balance of power, which has endured to the present day.

The Treaty of Westphalia marked a turning point in European history by ending the Thirty Years' War and laying the foundations of the modern international system. The treaty recognised states as the main actors on the international scene, putting an end to the idea of a universal monarchy embodied by the Holy Roman Empire. In addition, the political role of the Roman Catholic Church was considerably reduced, with the emphasis on national sovereignty and the inviolability of state borders. Thus, the Treaty of Westphalia marked the end of the supremacy of the Church in political affairs and strengthened the role of states in international relations. The Treaty of Westphalia was a key moment in European history, marking the birth of the state system and the decline of the ambitions of the Church and the Holy Roman Empire. The treaty laid the foundations for an international system based on respect for national sovereignty and the balance of power, which has endured to the present day.

From the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 onwards, the raison d'Etat became a founding principle of international relations. Reason of State is the idea that states should make decisions according to their own national interests, rather than according to moral or religious principles. This principle implies that states can act selfishly and seek to maximise their own power and wealth, even if this may have negative consequences for other states. This logic of the nation-state has prevailed for centuries and has influenced the foreign policy of many countries, including the major European powers.

Wars and conflicts have been a feature of European history. However, from the 19th century onwards, this system experienced significant limitations and challenges, particularly with the rise of nationalism and rivalries between the great European powers. The First World War was a major turning point in the history of international relations, as it challenged the very foundations of the Westphalian system. States mobilised their entire populations and resources for the war, resulting in considerable human and material losses. After the war, states tried to rebuild a system of international relations based on new principles, such as cooperation, disarmament and international law. This led to the creation of the League of Nations, which however failed in its mission to maintain world peace.

The end of the Westphalian system at the end of the First World War did not mean that states disappeared from the international scene. On the contrary, states remained structural actors in the international community and even strengthened their prerogatives, especially in terms of sovereignty and control over their territory. With the creation of the League of Nations, states sought greater international cooperation and the peaceful resolution of conflicts. However, rising nationalism and tensions between the great powers eventually led to the Second World War, which profoundly changed the international order. After the war, the international community sought to establish a new world order, based on principles such as international cooperation, respect for human rights and economic development. This led to the creation of the United Nations (UN) in 1945, which has become the central institution of the contemporary international system. States thus remain major players in the international community, although their role and influence have changed over time.

States remain major and fundamental actors in the contemporary international system. As sovereign political entities, states are the main holders of power and authority over their territory, which gives them a central place in international relations. States are able to negotiate treaties and agreements with other states, take military or diplomatic action, and participate in international organisations. They can also exercise sovereignty by regulating internal affairs, such as security, justice, public health and the economy. States can be divided into different categories according to their size, wealth, military power, cultural influence and geopolitical position. However, regardless of their relative position, all states are important players on the international scene and have a role to play in shaping the world order.

Strengthening national diplomacy

With the decline of the Westphalian system, states have strengthened their prerogatives and their diplomatic action has increased. National diplomacy became central to the management of international relations, representing the interests of their state abroad and negotiating agreements and treaties with other states. Diplomats are experts in international relations, with an in-depth knowledge of the culture, politics and interests of their country and those of other states. They are often involved in complex diplomatic negotiations, which can cover issues such as security, trade, the environment, human rights and conflict resolution. National diplomats have also developed networks of contacts and influence around the world to defend their state's interests and promote its foreign policy. This may include participation in international organisations, the establishment of bilateral relations with other states or the mobilisation of public opinion abroad.

In the mid-19th century, the diplomatic apparatus of European powers consisted mainly of delegations that were responsible for representing their country to other states. These delegations usually consisted of an ambassador, one or more diplomatic counsellors, secretaries and attachés. They are responsible for negotiating treaties, providing information on foreign affairs and representing their country at international conferences. However, despite their relatively small numbers, these diplomats play a crucial role in strengthening the national prerogatives of their states. Indeed, their presence allows states to better understand the intentions and policies of other states and to defend their interests in international negotiations. National diplomacy is thus a way for states to project their power and influence abroad and to reinforce their status as full members of the international community.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the foreign policy of states was mainly directed by small diplomatic elites, consisting of a few dozen people. Ambassadors and other diplomats in foreign capitals were the main actors in the foreign policy of states, and they had a central role in negotiating treaties, agreements and alliances. This strengthens national prerogatives, as national diplomacy has a great influence on decisions in international relations. Diplomacy is a means for states to defend and promote their interests on the international scene. By strengthening their diplomatic apparatus, states have consolidated their power and influence in international relations. Ambassadors and diplomats have played a key role in negotiating international treaties and agreements, managing crises and conflicts, and representing their countries abroad. This reinforced national sovereignty and the autonomy of states in the conduct of their foreign policy.

Nowadays, states' diplomatic apparatuses have become real bureaucracies, with increasingly complex and large structures. Diplomatic missions abroad, for example, often have large budgets and staff, with specialised sections in areas such as economic, cultural, scientific, environmental affairs, etc. State foreign ministries are also important institutions, playing a crucial role in the formulation and implementation of foreign policy. Diplomatic institutions and foreign ministries are increasingly active and professionalized. They are responsible for implementing the foreign policy of states, negotiating international agreements, maintaining relations with other states and international organisations, promoting national interests and protecting the citizens and economic interests of states abroad. These institutions have also developed capacities to analyse international developments, assess risks and opportunities, and provide advice to policy makers.

Until the mid-19th century, European diplomacy was largely monopolised by aristocrats. Ambassadors and special envoys were often chosen on the basis of their social standing rather than their competence. However, over time, the professionalisation of diplomacy has led to a diversification of the social background of diplomats, as well as a greater emphasis on training and expertise. Today, most countries have diplomatic academies or training programmes for diplomats. Over time, the diplomatic apparatus has moved towards increasing professionalisation, with the adoption of competitive recruitment and the promotion of social inclusion. This has led to a diversification of profiles and greater technical expertise in the fields of diplomacy, foreign policy and international cooperation. In addition, globalisation and the growing complexity of international issues have led to an increase in the number of staff in diplomatic services to meet these challenges. With the professionalisation of diplomacy, the sociology of the diplomatic community has undergone a significant change. Whereas in the past, diplomatic posts were often attributed to members of the nobility or the upper middle class, today recruitment is open to all and is often based on competitive examination. Moreover, diplomacy has become a profession in its own right, with specific training in political science schools or diplomatic schools. This has led to a social opening and a diversification of diplomats' profiles, who are now recruited on the basis of their competence and merit rather than their social origin.

In recent decades, the fields of action of diplomacy have expanded considerably. Diplomats are increasingly involved in security, trade, development, human rights, migration, environment, health and many other areas. For example, in security, diplomats play an important role in negotiating disarmament treaties, counter-terrorism, conflict prevention and peacekeeping. In trade, they are involved in negotiating trade agreements and international trade regulations. In development, they work on humanitarian aid, post-conflict reconstruction and economic development projects. Diplomacy has become a crucial tool for solving complex international problems and promoting cooperation between states.

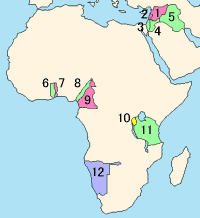

Since the end of the Second World War, the practice of diplomacy has become increasingly intense, with more and more states entering the international arena. Following decolonisation, many new states have been created in Asia, Africa and Latin America. This has led to an increase in the complexity of international relations and a multiplication of diplomatic actors. International organisations, such as the United Nations (UN), also played an important role in expanding the scope of diplomacy.

Diplomacy until the 19th century was effectively seen as a power politics, a defence of interests and a struggle for influence that could sometimes lead to armed conflict. States sought to protect their economic, territorial, political, cultural and religious interests abroad and to extend their influence through alliances, treaties, negotiations and diplomatic manoeuvres. Wars were often started to settle border disputes, trade rivalries, dynastic feuds, territorial ambitions or nationalistic aspirations. However, with the rise of political ideologies and awareness of global issues, diplomacy has evolved to include concerns such as human rights, the environment, international security, economic cooperation, regulation of world trade, public health, culture, etc. Until the 19th century, diplomacy was primarily a tool of power politics to defend national interests and influence international decisions. This practice could go as far as war, which was often seen as an extension of diplomacy. After this period, diplomacy continues to be an important foreign policy tool, but it is evolving towards a more multilateral approach, where states seek to cooperate and resolve conflicts through negotiation rather than military force. Diplomacy is also becoming more complex, with the emergence of non-state actors such as international organisations and civil society increasingly involved in international affairs. Modern diplomacy therefore involves a range of skills such as communication, mediation, negotiation, conflict resolution and multilateral cooperation.

Looking at long-term developments, one can observe an expansion of the fields of action of diplomacy, notably with the emergence of cultural diplomacy and economic diplomacy. Cultural diplomacy is the use of cultural and artistic exchanges between countries to promote understanding and relations between them. This form of diplomacy emerged in the 20th century in response to the rise of globalisation and international communication. It has become an important part of contemporary diplomacy, with organisations such as UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation) and many cultural cooperation programmes between countries. Economic diplomacy, on the other hand, became an important prerogative of states from the late 19th century onwards, when countries began to seek ways to promote their economic interests abroad. Economic diplomacy aims to promote trade, foreign investment and economic cooperation between countries. It is often carried out by embassies and specialised government agencies such as trade and foreign ministries.

At the end of the 19th century, economic globalisation grew rapidly, fuelled in particular by the expansion of international trade and investment. National economies were increasingly integrated into an evolving global economic system. In this context, the conquest of new foreign markets became a major challenge for states seeking to strengthen their economic power. From the end of the 19th century onwards, multilateral trade negotiations emerged with the aim of regulating economic exchanges between states. This was particularly the case with the signing of the Free Trade Treaty between France and Great Britain in 1890, which marked the beginning of a period of international trade negotiations aimed at reducing tariff barriers and promoting free trade. This movement was reinforced after the First World War with the creation of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 1919 and the International Trade Organisation (ICO) in 1948, which became the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995. These multilateral organisations aim to regulate international economic trade by promoting free trade and reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers between member states. Economic diplomacy has gained in importance since the end of the 19th century. States began to realise the importance of international economic exchanges for their prosperity and power. This led to increased diplomatic efforts to promote exports, attract foreign investment and negotiate bilateral and multilateral trade agreements. Over time, economic diplomacy has become an integral part of each country's foreign policy. States created specific ministries to deal with international economic issues and deployed networks of diplomats specialised in promoting national economic interests.

Cultural diplomacy appeared at the end of the 19th century, mainly under the influence of European countries. It consists of promoting a country's culture abroad to strengthen its image and influence in the world. This can be done through the creation of cultural institutes, the organisation of cultural events, the promotion of language, the dissemination of works of art, etc. Cultural diplomacy can thus be used as a soft power tool to strengthen relations between countries and improve their cooperation. Cultural diplomacy is often used as a means to compensate for a decline in a country's geopolitical power. It promotes a country's values, language and culture abroad, thus strengthening its image and influence in the world. France was one of the pioneers in this field with the creation of the Alliance Française in 1883, followed by other countries that also developed cultural diplomacy institutions and programmes.

In many countries of the 19th and 20th centuries, institutions aimed at cultural outreach were created. For example, in addition to the Alliance française in France, we can mention the British Council in Great Britain, the Goethe Institute in Germany, the Cervantes Institute in Spain, the Confucius Institute in China or the Japan Foundation in Japan. The aim of these institutions is to promote the language and culture of their country abroad, but also to encourage cultural exchanges and artistic collaboration between different countries. These institutions are often funded by governments but have a certain amount of autonomy and work in collaboration with other cultural actors in the foreign countries where they are located.

The expansion of the fields of intervention of diplomacy has led to the creation of new institutions and structures to meet these new needs. Economic diplomacy, cultural diplomacy, environmental diplomacy, and social and humanitarian affairs each have their own field of action and require specific skills. Governments have therefore created specialised organisations and agencies to deal with these different areas, while working with foreign ministries to coordinate their action abroad.

Nationalism and imperialism in the late 19th century

The process of nationalisation of international relations has been a key feature of diplomatic developments since the 19th century. The emergence of nation-states and their assertion on the international scene led to a strengthening of national sovereignty and an affirmation of foreign policy as an instrument for the defence and promotion of national interests. This was also facilitated by the conquest of colonial empires and the rivalry between the great powers for access to resources and markets in these regions. Diplomacy was therefore used to defend national interests in the international arena and to negotiate agreements to strengthen national power. Colonial conquest is an example of the manifestation of nationalisation in international relations. Nation-states seek to extend their influence and territory by conquering colonies on different continents, which can be seen as a competition between colonial powers for territorial dominance. This process also led to the creation of colonial empires and the establishment of colonial regimes that have shaped international relations for centuries.

At the end of the nineteenth century, new types of states emerged as empire states. These are characterised by their domination over territories outside their own national territory. They can take different forms, such as the colonial empires that developed in Europe, Asia and Africa, or the multinational empires, such as the Austro-Hungarian Empire or the Russian Empire, which grouped different nations under a single authority. This territorial expansion was often linked to the search for power and wealth, as well as strategic and geopolitical considerations. There is a strong relationship between the assertion of nation states and colonial expansion. Nation-states sought to extend their influence and power over external territories by establishing colonies. Imperialism was a way for nation-states to strengthen their position and to position themselves in a global hierarchy of powers. An ideology of the cultural and racial superiority of the colonising nations has also accompanied it. Nationalism and imperialism were thus driving forces behind the colonial expansion of the late 19th century.

Nationalism is a phenomenon that has manifested itself all over the world, not just in Europe. In the context of the period we are talking about, namely the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, we can observe the emergence of nationalist movements in many Asian and African countries. These movements were often triggered by colonisation and the political, economic and cultural domination of the European powers, leading to demands for independence and national self-determination. This dynamic contributed to the complexity of international relations at the time, creating new players and new demands that had to be taken into account by the major powers. There are several reasons why the colonies were never completely pacified. First of all, as you pointed out, nationalism is a global phenomenon that also manifested itself in the colonies. Nationalist movements in the colonies began to demand their independence and their political, economic and cultural autonomy, which led to conflicts with the colonial powers. The colonial powers then used violent methods to impose their domination, which often led to violent reactions from the colonised populations. The methods of colonial domination included economic exploitation, political repression and physical violence. Finally, colonial powers often used policies of division and conquest to maintain their dominance over the colonies. These policies created tensions between the different ethnic and religious communities within the colonies, which often degenerated into violence.

The emergence of new international actors

The first international organisations

International organisations appeared at the end of the 19th century, with the creation of the International Telegraph Union in 1865 and the Universal Postal Union in 1874. However, it was mainly after the First World War that the creation of international organisations intensified, with the foundation of the League of Nations in 1919 and many other specialised organisations in areas such as health, education, trade and international security. Since then, many other international organisations have emerged, such as the United Nations in 1945, and they have played an important role in cooperation and coordination between member countries.

From the 1850s-1860s, there was an accelerated process of economic globalisation, with the expansion of international trade and the growth of capital exchange. This led to the need to standardise trade rules between different countries. States began to negotiate bilateral trade agreements to regulate their trade. However, these agreements were often limited to specific sectors or products and it was difficult to harmonise the rules between different countries. Therefore, in the late 19th century, initiatives were launched to establish common international standards and regulate trade on a global scale. The need for international standardisation became apparent in the late 19th century as international trade grew. Countries began to realise that it was difficult to trade with countries that did not apply the same standards, whether in terms of customs, taxes or trade rules. This led to the creation of the first international organisations, such as the Universal Postal Union in 1874 and the International Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law relating to Bills of Lading in 1924. The aim of these organisations was to facilitate trade between countries by establishing common standards.

This first phenomenon of international organisations emerged in the 1860s with the International Unions:

- The International Telegraph Union (ITU) was created in 1865 with the aim of facilitating telegraphic exchanges between countries. It was the first international body to be established to regulate international telecommunications. The UTI played an important role in expanding the use of the telegraph worldwide, facilitating exchanges between different national telegraph networks and harmonising tariffs and billing procedures. It was replaced in 1932 by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

- The Universal Postal Union (UPU) is an international organisation founded in 1874 in Berne, Switzerland, with the aim of coordinating postal services between member countries. Its mission is to promote the development of postal communication and to facilitate the international exchange of mail by establishing international standards and tariffs for sending mail between countries. Today, the UPU has 192 member States and is based in Berne.

- The International Union of Weights and Measures (UIPM) was founded in 1875 with the aim of establishing international cooperation in metrology and ensuring the uniformity of measurements and weights used in international trade. It established the International System of Units (SI) in 1960, which is now used in most countries of the world.

- The International Union for the Protection of Industrial Property was founded in 1883 in Paris. It later became the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), with its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland. WIPO is a specialised agency of the United Nations whose mission is to promote the protection of intellectual property throughout the world by providing a legal framework for the protection of patents, trademarks, industrial designs, copyright and geographical indications.

- The International Union for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (UIPLA) was founded in 1886 in Berne, Switzerland. It was created in response to the need to protect the intellectual property rights of artists and authors on an international scale. Today, UIPLA is known as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and is a specialized agency of the United Nations.

- The International Union of Agriculture was established in 1905 to promote international cooperation in the field of agriculture and the improvement of agricultural methods. It was replaced by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) in 1945.

- The International Office of Public Health was established in 1907. It is an international organisation responsible for monitoring and promoting public health throughout the world. It was created in response to a series of global pandemics, including plague and cholera, which affected many countries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The International Office of Public Health was replaced in 1948 by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The aim of international unions was to establish common standards and regulations to facilitate trade between member countries. This has led to the harmonisation of communication systems, measurements, industrial and intellectual property protection, as well as health and food safety. These unions have thus contributed to the growth of international trade and cooperation between nations.

International organisations require specific skills that may differ from those of traditional diplomats. They are often made up of technical experts in specific fields, such as trade, health, environment, human rights, etc. Diplomats work with these organisations in a collaborative manner. Diplomats work with these experts to develop international policies and standards in their area of specialisation. The problems that emerged in the 20th century, such as armed conflicts, economic crises, environmental and public health challenges, required the creation of new international organisations with greater involvement of experts in their functioning. One such organisation was the League of Nations, created in 1919 following the end of the First World War, with the mission of maintaining international peace and security. Despite its efforts, the League of Nations failed to prevent the outbreak of the Second World War and was replaced by the United Nations (UN) in 1945. The UN has become one of the most important international organisations, with missions ranging from international peace and security to the promotion of economic and social development, the protection of human rights, the prevention of natural disasters and the management of health crises. The composition of the UN also reflects the emergence of new international actors, such as developing countries and civil society organisations.

Experts played an increasingly important role in international negotiations during the 19th century. States realised the importance of having experts in specific fields to negotiate with other states and to find common agreements. The harmonisation of measurement systems is an example of this collaboration between international experts. The metre became a recognised international unit of measurement in 1875 thanks to the efforts of scientists and engineers from several countries. This international recognition facilitated trade and scientific exchange between countries.

Administrative unions have played a key role in the development of multilateral negotiation between states. By meeting regularly, states have had the opportunity to discuss and negotiate common standards, regulations and public policies, thus facilitating international cooperation and promoting global policy harmonisation. This experience also provided the basis for the subsequent creation of broader international organisations, such as the League of Nations and the United Nations, which strengthened the role of multilateral negotiation in international relations.

The establishment of an international system with universal aims may conflict with the interests of some nation states. This can lead to tensions and conflicts in international relations. For example, the idea of international human rights protection may be perceived as an infringement on the sovereignty of states that prefer to stick to national norms and values. This is why there may be resistance to the implementation of certain international standards, even if they are considered universal and legitimate by the international community.

Non-governmental actors

Under public international law, only states and international organisations have international legal personality. Non-governmental actors such as individuals, companies, NGOs and social movements do not have international legal personality, although they may participate in negotiation and consultation processes as observers or consultants. However, these actors can have a significant influence on international policy and decision-making. Non-governmental actors are not recognised under international law as legal entities in their own right, but their role is increasingly important in international relations. This can pose problems of regulation and participation in international decision-making. Some non-governmental organisations have managed to gain recognition by international organisations and have been granted consultative status. This allows them to participate in meetings and contribute to debates, but their decision-making power remains limited.

Defining non-governmental organisations is not straightforward as there is no universal or official definition. However, it can be said that they are private, non-profit organisations that have a public service or general interest mission, and operate outside the government apparatus and on a non-profit basis. NGOs can operate at different levels, from the local community to the international level, and can work on a wide range of issues such as environmental protection, human rights promotion, humanitarian aid, etc. The status of non-governmental organisations is complex and their definition varies according to the context and the country. They can have very diverse missions and be involved in areas such as environmental protection, the defence of human rights, humanitarian aid, public health, etc. Some organisations are very small, while others are large. Some organisations are very small, while others are major players in civil society. In addition, some organisations have close relations with governments, while others are completely independent. This makes it difficult to define them clearly and to determine their place in international law. With the emergence of peace movements and the idea of international regulation of problems, non-governmental actors began to play an important role in international relations. However, their legal status was not clear at the time, and it took several decades before their role was recognised in international law. Today, non-governmental organisations have an important place in international life and are recognised as actors in their own right.

From the end of the 19th century onwards, new actors came into play in the field of international relations. These include peace movements, civil society organisations and intellectuals who are interested in the issue of peace and the regulation of international conflicts. These new actors are often non-professionals in diplomacy, but they bring a different perspective and new proposals for resolving disputes between states. The incursion of non-governmental actors into international relations has profoundly changed the nature of the way international relations work. It has led to an increase in the complexity of actors and issues, as well as a multiplication of channels of communication, negotiation and cooperation. NGOs, associations, social movements, transnational companies, individuals, etc. have thus been able to participate in the definition and implementation of international policies and standards, often in collaboration with states and international organisations. This dynamic has also favoured the emergence of global issues such as the environment, human rights, health, global governance, etc., which have given rise to new debates and new forms of cooperation between the actors concerned.

Non-governmental organisations have various fields of action:

- Humanitarian organisations: the Red Cross is one of the best known and oldest humanitarian organisations in the world. It was founded by the Swiss Henri Dunant in 1863, after he witnessed the suffering of wounded soldiers at the Battle of Solferino in Italy in 1859. Dunant gathered volunteers to help the wounded on both sides, regardless of their nationality. This experience led him to propose the creation of an international movement that would provide relief in the event of war and be protected by an international convention.

- Pacifism: Pacifism is a movement that emerged at the end of the 19th century in response to rising tensions between nations and the wars that ensued. There are several forms of pacifism, including legal pacifism and parliamentary and political pacifism, which aim to promote peace through law and diplomacy rather than war. There is also religious pacifism, which is based on the belief that war is contrary to the teachings of certain religions, and militant pacifism, which advocates conscientious objection and non-violent direct action as a means of fighting war.

- Legal pacifism is a school of thought that aims to promote peace through international law. Legal pacifists seek to theorise a legal regime of peace and to establish rules for resolving international conflicts in a peaceful manner. They advocate international arbitration, mediation and negotiation to resolve conflicts between states. In 1899 and 1907, international peace conferences were held in The Hague, Netherlands, which codified rules of international humanitarian law. These conferences were followed by the creation of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, which is an international institution for resolving disputes between states through arbitration.

- Pacifism' of parliamentary and political circles: The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) was founded in 1889. It is the oldest international intergovernmental organisation. It was founded to promote cooperation and dialogue between the parliaments of different countries, and to contribute to international peace and cooperation. The IPU works in particular to promote democracy and human rights, the peaceful resolution of conflicts, economic cooperation and sustainable development.

- Industrial pacifism: Industrial pacifism is a movement that aims to promote peace by addressing the economic and social causes of conflict. It emerged in the early 20th century and has had some success in the United States and Europe. Industrial pacifists advocate an economy based on cooperation rather than competition, and seek to promote fair and environmentally friendly trade practices. They also oppose the arms race and wars that are often motivated by economic interests. Some industrial pacifists have been involved in social movements such as the civil rights movement and the labour movement.

Pacifism is an international movement that developed in Europe, but also in North America in the late 19th century. In the United States, the pacifist movement gained momentum with the Spanish-American War of 1898, which saw the United States become involved in an armed conflict outside its own territory. American pacifists created organisations such as the Anti-War League in 1898 and the Friends of Peace Society in 1905. These organisations worked to raise awareness of the human and economic costs of war, and sought to promote diplomacy and negotiation as a means of resolving international conflicts. Pacifism is an international movement that developed in Europe, but also in North America in the late 19th century. In the United States, the pacifist movement gained momentum with the Spanish-American War of 1898, which saw the United States become involved in an armed conflict outside its own territory. American pacifists created organisations such as the Anti-Imperialist League in 1898. The European idea was also spread by the Anglo-American pacifist movement, which encouraged the creation of peace on the European continent. Organisations such as the Peace and Freedom Society were created in Paris and Geneva to promote international peace and cooperation. In addition, some proponents of free trade, such as Frederic Bastiat, also advocated peace in Europe. Bastiat founded the Society of Friends of Peace in France to promote economic cooperation and understanding between nations. These organisations worked to raise public awareness of the human and economic costs of war, and sought to promote diplomacy and negotiation as a means of resolving international conflicts.

- Scientific and technical cooperation: Scientific and technical cooperation organisations are often created by wealthy patrons who wish to fund research and development projects in various scientific and technical fields, such as medicine, agriculture, energy or information technology. These organisations aim to promote innovation and technical progress through international collaboration and the exchange of knowledge and technology between different countries and institutions. The Rockefeller Foundation was established in 1913 by John D. Rockefeller, a wealthy American industrialist. The foundation has supported many initiatives in the fields of public health, education, scientific research and agriculture around the world. For example, it has contributed to the eradication of yellow fever in Latin America, the fight against sleeping sickness in Africa and the development of agriculture in Asia. The Rockefeller Foundation is an example of how private organisations can have a significant positive impact on the lives of people around the world.

- Religious organisations: the distinction between religious and non-governmental organisations can sometimes be blurred. Some religious organisations may act outside their primary mission to engage in humanitarian, social or environmental activities, for example. In this case, they can be considered to be acting as non-governmental organisations. However, it is important to note that religious organisations often have a specific purpose and focus related to their belief or doctrine, which differentiates them from other types of non-governmental organisations. The YMCA (Young Men's Christian Association) is a non-profit Protestant religious organisation founded in 1844 in England. Although their primary mission is to promote Christian values, YMCAs are also involved in a variety of social, cultural and educational activities aimed at helping young people develop in a positive way. For example, they have developed vocational training and personal development programmes, as well as sports activities such as basketball, volleyball and swimming. Today, YMCAs are present in over 119 countries and have over 64 million members.

- Feminist organisations: Feminist organisations emerged at the end of the 19th century, when women began to fight for their rights and organise themselves into political communities. The International Council of Women was founded in 1888 by women's rights activists from different countries, and has since worked to promote gender equality and fight discrimination and violence against women around the world. There are now many other feminist organisations around the world working on issues such as political representation, reproductive health, equal pay and combating gender-based violence.

- Cultural and intellectual exchange organisations: Cultural and intellectual exchange organisations have played an important role in promoting intercultural dialogue and international cooperation. The Esperanto clubs, as you mentioned, were organisations that advocated the use of a universal language, Esperanto, to facilitate communication and exchange between people of different cultures. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) is a non-governmental organisation established in 1894, with its headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland. The IOC is responsible for the organisation of the Olympic Games, which are an international sporting and cultural event. The IOC member states are represented by National Olympic Committees, which are themselves non-governmental organisations. The Olympic Games are therefore an example of international cooperation between non-governmental organisations and states. At the end of the 20th century, numerous scientific congresses were set up, particularly in the fields of medical research, physics and chemistry. These congresses allow scientists from all over the world to meet, exchange ideas, present their work and collaborate on joint research projects. They are often organised by scientific associations or academic institutions and can have a significant impact on the development of science and technology worldwide.

Non-governmental organisations have a wide variety of structures and objectives, which makes them difficult to characterise definitively. For example, some NGOs are funded by governments or companies, which raises questions about their independence and impartiality. Similarly, some NGOs are heavily involved in politics, while others focus mainly on humanitarian aid. There are also debates about the role and impact of NGOs in society, including their effectiveness in solving the problems they aim to address.

- Public/private boundary: the boundary between public and private can be blurred in the case of non-governmental organisations. The Red Cross, for example, is an organisation that operates internationally as a private entity, but it is mandated by the signatory states of the Geneva Convention. Thus, it has a public mission in the humanitarian field, but it is funded mainly by private donations and voluntary contributions. In this sense, the Red Cross is an organisation that operates in a grey area between the public and the private. National Red Cross Societies are often closely linked to the governments of their respective countries, and this is even more true when there is a conflict or a major humanitarian disaster. In these situations, governments can provide significant financial support and logistical assistance to Red Cross societies to enable them to carry out their humanitarian mission. However, Red Cross Societies are independent organisations with their own structure and leadership, and they must respect the fundamental principles of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, such as humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, voluntary service, unity and universality.

- Networking: Networking is an important characteristic of non-governmental organisations. Networks enable organisations to work together to achieve common goals, share information, resources and expertise, coordinate efforts and build capacity. Networks can be formal or informal, regional or global, focused on specific problems or broader issues. They can include civil society organisations, intergovernmental organisations, governments, businesses, universities and individuals. Networking allows non-governmental organisations to maximise their impact and increase their influence on policy makers at the global level.

- Rival organisations: Non-governmental organisations are often very committed to noble causes, but this does not prevent them from having a turbulent history, with internal conflicts and tensions with other organisations. These struggles for symbolic recognition and influence in the public sphere can sometimes obscure the underlying issues of the causes they are defending. It can also have negative consequences for the effectiveness of their work and their ability to mobilise resources. The International Council of Women was created in 1888 in response to the dissatisfaction of feminist activists who, although very numerous in the labour and peace movements, were not recognised as such within these movements. The Council gained recognition and established contacts with other organisations. However, tensions arose within the movement as some members felt that the leadership did not give sufficient importance to political concerns, especially for the extension of public rights to women. As a result, in 1904, the movement created the International Suffrage Alliance, and in 1915, the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom was formed. In addition, some of the members felt that rising international tensions were creating nationalist tensions within the movement, leading to a further split.

The end of the 19th century saw the emergence of a number of international actors who helped shape the international system as we know it today. These actors include non-governmental organisations, social movements, multinational companies, the international media, etc. These actors have gradually gained in importance and have become more and more important. These actors have gradually gained in importance and have begun to play a major role in international relations, alongside states and intergovernmental organisations. This development has profoundly transformed the nature of international issues and contributed to the emergence of an increasingly complex and interconnected international system.

Early regionalism: the Pan-American Union

The Pan American Union is an early example of regionalism, which emerged at the end of the 19th century in Latin America at the instigation of the United States. The organisation aimed to promote cooperation and integration among the countries of the American continent, as well as to strengthen their economic, political and cultural ties. The Pan American Union is considered a forerunner of the Organisation of American States (OAS), which was founded in 1948.

Regionalism is a political and cultural movement that seeks to strengthen identity and solidarity between countries in the same region, often in reaction to external forces or universalism. In the early 20th century, the tension between nationalism and universalism led to the emergence of regionalist movements, which sought to balance national interests with the needs of regional cooperation. Regionalism has often been seen as a response to nationalism, which emphasises the identity and sovereignty of a particular country. However, regionalism can also be seen as a complement to nationalism, as it seeks to preserve and promote the common interests of countries within a region.

The Pan American Union was an important step towards the creation of regional institutions in Latin America, which have contributed to the political and economic stability of the region. The OAS, which succeeded the Pan American Union, continues to play an important role in promoting democracy, human rights and economic development in the Americas. Regionalism has also inspired the creation of other regional organisations and initiatives around the world, such as the European Union, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). These organisations aim to strengthen cooperation among member countries and foster regional integration, while respecting the sovereignty and identity of each country.

The first Pan-American Conference was actually held in 1889-1890 in Washington, D.C. The Pan-American Union was formally created in 1910, following the ratification of the 1910 Buenos Aires Convention by the participating countries. The main objective of the first Pan-American Conference was to establish a system of cooperation and dialogue between the countries of North, Central and South America. One of the main topics discussed at the conference was the promotion of economic integration and trade between the countries of the region. Among the proposals discussed at the conference were the adoption of common standards for trade and shipping, arbitration to resolve disputes between countries and the creation of a customs union. Although not all of these proposals were implemented immediately, the conference laid the groundwork for increased cooperation and economic integration initiatives in the following decades. The Pan American Union, which succeeded the Pan American Conference, continued efforts to promote economic integration and trade among the countries of the Americas. The organisation has played a role in coordinating and facilitating economic relations among its members, organising conferences and meetings to discuss issues of common interest and promoting economic and technical cooperation projects.

One of the objectives of the Pan American Union was to resolve border disputes between member countries in a peaceful and non-violent manner. As you mentioned, many Latin American countries inherited unclear and ill-defined borders as a result of the break-up of the Spanish empire. These uncertain borders often led to tensions and conflicts between neighbouring states. The Pan American Union has encouraged the peaceful resolution of border disputes by promoting dialogue, negotiation and arbitration between the parties involved. The organisation has also acted as a mediator by providing legal and technical advice and facilitating discussions between countries in conflict. Over the years, the Pan American Union and its successor, the Organisation of American States (OAS), have helped to resolve several border conflicts in the region. For example, the OAS played a key role in mediating the dispute between Belize and Guatemala over their common border. Promoting the peaceful resolution of border disputes has been essential to prevent armed conflict and to strengthen political and economic stability in the region. By encouraging cooperation and dialogue among member countries, the Pan American Union and the OAS have helped create an environment conducive to development and regional integration.

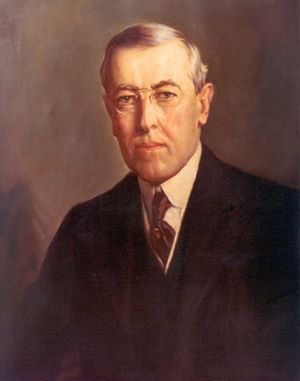

Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the United States, took office in 1913, three years after the creation of the Pan American Union. Although the Pan American Union was founded before his presidency, Wilson supported and encouraged deeper economic and political integration among the countries of the region. Wilson was a strong advocate of international cooperation and diplomacy as a means of preventing conflict and promoting peace. His approach to foreign policy, known as 'Wilsonism', emphasised democracy, the free determination of peoples and multilateralism. Wilson's Fourteen Points, presented in 1918, were a set of principles intended as a basis for peace after the First World War. Although these points were not directly related to the Pan American Union, they reflect Wilson's commitment to international cooperation and the self-determination of nations. Among the Fourteen Points, several were relevant to Latin America and the objectives of the Pan American Union. For example, the principle of free navigation of the seas, the lowering of economic barriers and the creation of a general association of nations to guarantee political security and the independence of states. Although Wilson's Fourteen Points were not directly related to the Pan American Union, they shared similar goals and reflected Wilson's vision for a more peaceful and cooperative world. During Wilson's presidency, the US continued to support the Pan American Union and sought to deepen economic and political integration in the region. However, it should be noted that Wilson's foreign policy in Latin America was also criticised for its interventionism and paternalism, particularly through the Monroe Doctrine, which aimed to protect US interests in the region.[4]

Woodrow Wilson's proposal for collective security was an important aspect of his vision for the Pan American Union and for international cooperation in general. Wilson believed that peace and stability could be maintained by encouraging nations to work together to resolve conflicts and by guaranteeing collective security. The Pan-American Union was designed not only to promote economic and political integration, but also to address other issues of security, development and regional cooperation. Over the years, the organisation has broadened its scope to include various prerogatives, such as the peaceful resolution of conflicts, the promotion of human rights, development cooperation and environmental protection. The idea of collective security also influenced the creation of the Organisation of American States (OAS) in 1948, which succeeded the Pan-American Union. The OAS adopted a Charter enshrining principles such as non-intervention, the peaceful resolution of conflicts, democracy, human rights and economic and social solidarity. Today, the OAS continues to play a central role in promoting collective security and regional cooperation in the Americas. The organisation strives to prevent and resolve conflicts, promote democracy and human rights, and foster economic and social development in the region. Ultimately, the Pan American Union and the OAS illustrate how regional organisations can evolve to address an increasingly broad and interconnected range of issues. These organisations were influenced by visions such as that of Woodrow Wilson, who believed in the need for international cooperation and collective security to ensure peace and prosperity.

The Pan American Union expanded its prerogatives and areas of action in the early 20th century to address a range of regional issues, including health, science, law and defence. In 1902, the Pan American Sanitary Bureau, now known as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), was established to promote cooperation in public health and to combat epidemics in the region. PAHO has worked to improve disease surveillance, epidemic control and public health standards in the Americas. The Inter-American Juridical Committee, created in 1928, aims to promote legal cooperation and harmonisation of legislation among member countries. This initiative led to the creation of the Inter-American Court of Justice in 1948, which is responsible for resolving legal disputes between member states and ensuring respect for human rights. Scientific and academic associations were also created to encourage collaboration and the exchange of ideas among scholars and researchers in the Americas. These organisations have helped to promote innovation and scientific development in various fields, such as technology, the environment and the social sciences. Finally, collective security was addressed with the creation of the Pan American Defence Organisation in 1942, during the Second World War. The purpose of this organisation was to promote defence coordination and cooperation among the countries of the region to address common threats and ensure regional security. This initiative laid the foundation for security cooperation within the framework of the Organisation of American States (OAS), which was established in 1948. These developments show how the Pan American Union has evolved over time to address a wide range of regional issues and challenges. The resulting initiatives and institutions continue to play an important role in promoting regional cooperation and integration in the Americas.

The regionalist construct, which began in the late 19th century with the Pan American Union, has similarities with the League of Nations (League) and, by extension, the United Nations (UN). These organisations share common principles, such as the promotion of international cooperation, the peaceful resolution of conflicts, the protection of human rights and the promotion of economic and social development. The Pan-American Union can be considered a blueprint for the UN model, as it introduced mechanisms for regional and multilateral cooperation that were later adopted and developed by the League of Nations and the UN. However, it should be noted that the Pan-American Union focused mainly on regional issues in the Americas, while the UN and the League of Nations have a global scope. It is also important to note that the Pan American Union was not necessarily a competitor to the League of Nations, as both organisations pursued similar objectives but operated at different levels. The Pan American Union focused on promoting regional cooperation and integration in the Americas, while the League of Nations had the mission of maintaining international peace and security and promoting cooperation among nations around the world. With the creation of the United Nations in 1945, the principles and mechanisms of the Pan American Union and the League of Nations were incorporated into the UN system. The Organization of American States (OAS), which succeeded the Pan American Union in 1948, became a regional partner of the UN and works closely with the world body to promote peace, security, human rights and development in the Americas.

During the interwar period, the Pan American Union and the League of Nations (League) did cooperate on some issues, but also maintained a certain distance due to the tensions between nationalism and universalism. The Pan American Union, as a regional organisation, aimed to promote cooperation and integration among the countries of the Americas. The League of Nations, on the other hand, was global in scope and aimed to maintain international peace and security by encouraging cooperation among all nations. Although the two organisations shared common goals, their approaches and areas of action differed, reflecting the tensions between nationalist and universalist aspirations at the time. Latin American nations, in particular, were often torn between the desire to preserve their sovereignty and national identity, and the aspiration to participate in an international system based on cooperation and multilateralism. This tension sometimes led to friction between the Pan American Union and the League of Nations, as each sought to assert its role and influence on the international scene. Despite these tensions, the Pan American Union played a crucial role in the beginnings of regionalism and laid the foundations for regional cooperation and integration in the Americas. The principles and mechanisms developed by the Pan American Union influenced the creation of other regional organisations and helped shape the international system that emerged after World War II, notably with the creation of the United Nations (UN) and the Organisation of American States (OAS).

The League of Nations: the birth of a universal system

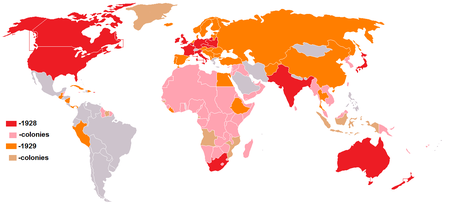

The League of Nations was the first universal international organisation created after the First World War, in 1919, with the aim of maintaining international peace and security by promoting cooperation between member states. It included most of the world's states at the time, but some countries such as the United States did not join the League, and others such as Germany and the Soviet Union joined later.

The origins

The idea of creating an international organisation to settle conflicts between states was supported by pacifist and humanitarian movements from the end of the 19th century. Personalities such as the writer Victor Hugo or the philosopher Bertrand Russell defended this idea in their writings and speeches. The pacifist movements of the end of the 19th century contributed to the formation of the idea of an international regulation of problems. They expressed an aspiration for peace and international cooperation in response to the ravages of the wars that shook Europe in the 19th century. Personalities such as the British philanthropist Alfred Nobel, the French journalist Henri Dunant, founder of the Red Cross, and the Swiss jurist Gustave Moynier, in particular, worked in favour of this idea. Their reflections contributed to the awareness of the need to set up international institutions to settle disputes between states peacefully. However, it was only after the First World War, which saw unprecedented violence and a horrific death toll, that the creation of an international organisation became a priority for many states. The League of Nations was created in 1919 with the aim of preserving international peace and security. The origin of this is the multitude of peace movements that were born and that formulated the first ways of structuring the idea of an international regulation of problems, which was a new idea.

In a period marked by nationalism and rivalry between states, the idea of a supranational authority to regulate conflicts and guarantee peace was new and daring. It was the subject of intense debate and discussion among the peace movements and intellectuals of the time. This idea was finally realised with the creation of the League of Nations after the First World War, although it failed to prevent the rise of tensions and the outbreak of the Second World War.

The Hague Congresses are considered founding events of modern multilateral diplomacy, with the aim of preventing armed conflict and developing peaceful means of settling disputes between states. The first Hague Congress, in 1899, resulted in the signing of several international conventions, including the Hague Convention Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Second Congress, in 1907, expanded the scope of international humanitarian law and also led to the signing of several conventions, including the Hague Convention on International Pacification. These congresses thus laid the foundations of multilateral diplomacy and contributed to the formation of the idea of international conflict regulation. The idea of arbitration was formalised at the Hague Peace Congresses in 1899 and 1907, where states discussed the possibility of resolving international conflicts by peaceful means rather than by war. This idea was promoted by the peace movements and in particular by the organisations of legal pacifism, which considered that disputes between states should be settled by international tribunals rather than by armed force. Arbitration was therefore seen as a means of preventing war and settling international disputes peacefully.

The first Hague Congress in 1899 was convened by the Russian Tsar Nicholas II and brought together 26 European and American states. The aim was to discuss arms control and war prevention. The delegates adopted several resolutions, the most important of which was the adoption of the Hague Convention for the Peaceful Settlement of International Disputes, which provided for compulsory arbitration for disputes that could not be settled by negotiation. A Permanent Court of Arbitration, composed of judges chosen by the member states, was also established to resolve such disputes. The resolutions of the First Congress were revised and expanded at the Second Congress in The Hague in 1907.

The Court of Arbitration set up by the First Hague Congress in 1899 was not permanent and had to be specially created for each dispute. Furthermore, the Court's jurisdiction was subject to the will of the states, which had to agree to submit their dispute to arbitration and to abide by the decision rendered. Finally, the states themselves had to designate the arbitrators who would sit on each case.

In 1907, the Second Hague Congress strengthened the principle of arbitration by creating a permanent court of arbitration to sit in The Hague. This court would be composed of judges from the signatory states of the Hague Convention and would be responsible for settling international disputes through arbitration. The Permanent Court of Arbitration was open to all states that accepted the convention and was intended to promote international peace and justice. The establishment of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1907 in The Hague was a major step forward in the peaceful resolution of international disputes. However, despite the adoption of this measure by the Hague Conference, it is true that not all states immediately ratified this initiative. That said, the Permanent Court of Arbitration began to operate from its inception, with a permanent secretariat to facilitate the appointment of arbitrators. It has contributed to the peaceful resolution of many international disputes in the decades since.

Léon Bourgeois, as President of the French Council, played an important role in the adoption of the principle of arbitration at the Hague Conference in 1899. He advocated the idea of peaceful settlement of international disputes through arbitration and was instrumental in the creation of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1907. Léon Bourgeois was a French politician who played an important role in the promotion of peace and international law in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In particular, he chaired the French delegation to the Hague Peace Conference in 1899 and 1907, where he promoted the idea of a permanent court of international arbitration. He was also one of the founders of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, an international organisation to promote parliamentary cooperation and the peaceful resolution of conflicts. Bourgeois was a strong advocate of international arbitration and was instrumental in advancing the idea of an international organisation to settle disputes between nations, which eventually led to the creation of the League of Nations.

In 1907, despite the reaffirmation of the principle of arbitration and the creation of a permanent court of arbitration in The Hague, tensions between the European powers began to rise, and the decisions taken by the Hague conference were little followed. Indeed, nationalist movements and the rise of rivalries between the great powers made it difficult to set up effective international regulation. The two Hague congresses laid the foundations for certain ideas that were later taken up and developed by the League of Nations, such as the principle of arbitration to settle international disputes or the creation of a permanent court of arbitration. These ideas were promoted by peace movements and non-governmental organisations, but were also adopted by the great powers at the Hague conferences.