« Teorías de la Economía Política Internacional » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 163 : | Ligne 163 : | ||

El liberalismo clásico de la economía mundial anterior a 1914 era el de los flujos de capital de comercio relativamente libre en el patrón oro. La etapa actual de la globalización, con el avance del libre comercio y los flujos de capital libres y la ideología asociada del consenso de Washington teorizado en 1990 por John Williamson. Él teorizó que la receta esencial para la evolución económica es liberalizar la economía propia, privatizarla y desregularla. | El liberalismo clásico de la economía mundial anterior a 1914 era el de los flujos de capital de comercio relativamente libre en el patrón oro. La etapa actual de la globalización, con el avance del libre comercio y los flujos de capital libres y la ideología asociada del consenso de Washington teorizado en 1990 por John Williamson. Él teorizó que la receta esencial para la evolución económica es liberalizar la economía propia, privatizarla y desregularla. | ||

== | == Consideración general == | ||

Existe un paralelismo entre el debate sobre el mercantilismo, el nacionalismo y el liberalismo en la economía política clásica y el debate entre el realismo y el neoliberalismo en las relaciones internacionales y la EPI. | |||

Tanto el mercantilismo como el nacionalismo y el liberalismo son escuelas de pensamiento que aportan poderosas doctrinas y visiones del mundo que siguen formando la política económica. Por ejemplo, en Francia, hoy en día, cuando se trata de discutir la política industrial, todo el mundo habla de Colbert y piensa en la inspiración en la forma en que Colbert promovió la industria en los siglos XVII y XVIII en Francia. | |||

Estas escuelas de pensamiento son menos útiles como marcos analíticos. Tienen una orientación mucho más normativa y positiva. Pretenden comprender el mundo a partir de una serie de preconceptos sobre la organización y el funcionamiento de las sociedades. Como marcos analíticos, no son muy útiles. | |||

La EPI moderna ha intentado desarrollar un enfoque más positivo y de orientación analítica para comprender y analizar el funcionamiento de la economía global y el capitalismo global. El principal beneficio de esto es que permite un análisis que entiende por qué es posible que coexistan elementos mercantilistas y liberales uno al lado del otro en el mismo sistema. | |||

Esto significa que la EPI moderna se basa en la identificación de los bloques o variables políticas y económicas en las que se basa y funciona el capitalismo global. También intenta identificar la forma en que esas variables interactúan entre sí. Las tres categorías principales son variables que utiliza la IPE son: | |||

* | *intereses, es decir, los actores económicos que componen el sistema y el tipo de intereses que tienen. Rechaza la idea de que algo llamado interés nacional sea primordial, etc. También rechaza la idea de que todos los individuos tienen los mismos intereses básicos que están en la base de la noción liberal de homo economicus fue la base de las nuevas clasificaciones. | ||

* | *instituciones: las instituciones tienen una influencia independiente en la forma de organizar la interacción económica entre los estados en el capitalismo global. | ||

*Ideas | *Ideas que tienen una influencia independiente en la forma en que se elaboran las políticas económicas exteriores y en cómo interactúan los Estados entre sí en la economía política internacional. | ||

= Theoretical evolution = | = Theoretical evolution = | ||

Version du 22 mars 2021 à 13:50

| Faculté | Global Studies Institute |

|---|---|

| Professeur(s) | Christakis Georgiou[1][2][3][4] |

| Cours | Economía Política Internacional |

Lectures

- ¿Qué es la Economía Política Internacional?

- Una breve historia del capitalismo internacional

- Teorías de la Economía Política Internacional

- Cooperación comercial internacional

- Política de comercio interior

- Política de acuerdos de comercio preferencial

- Empresas multinacionales y cadenas de valor mundiales

- Política de las corporaciones multinacionales

- International monetary cooperation

- Política monetaria y cambiaria

- Política de las crisis financieras internacionales

- Democracias en economías globalizadas

Esta conferencia trata de las teorías de la economía política internacional o del capitalismo global. En primer lugar, repasaremos los debates históricos sobre el capitalismo global que abarcan el mercantilismo y el liberalismo. Estas dos son las visiones del mundo más destacadas o los enfoques generales del capitalismo global y de cómo las economías individuales se relacionan con él. Lo haremos porque esos dos enfoques de mentalidad siguen siendo relevantes hoy en día, no tanto como teorías en el término analítico, sino como enfoques de la forma en que se hacen las políticas. Examinaremos cómo surgió teóricamente la EPI desde sus inicios. Cuando la EPI se desarrolló como una disciplina o subdisciplina académica distinta en la década de 1970, lo hizo en gran medida a partir del debate sobre las relaciones internacionales. En este sentido, examinaremos cómo los debates en las relaciones internacionales dieron lugar a la EPI. Examinaremos con más detalle las perspectivas de la EPI estadounidense contemporánea. La disciplina puede dividirse en dos grandes escuelas: la estadounidense y la británica. Este curso se centra principalmente en la escuela estadounidense. Por lo tanto, examinaremos las perspectivas teóricas de la escuela americana en los últimos 30 años y las aplicaremos a lo largo del curso.

Debates históricos sobre el capitalismo mundial

Mercantilismo

Para Oatley, "el mercantilismo es una escuela tradicional de economía política que data (al menos) del siglo XVII. Afirma que el poder y la riqueza están inextricablemente conectados. En consecuencia, sostiene que los gobiernos estructuran sus transacciones económicas internacionales para aumentar su poder en relación con otros Estados y la sociedad nacional. El mercantilismo describe así la economía política internacional como intrínsecamente conflictiva".[5]

En términos puramente económicos, el mercantilismo concibe cómo se desarrolla la lucha entre los estados en el ámbito económico internacional, observando la balanza comercial. El indicador clave de la capacidad de un Estado para ganar o si un Estado está ganando el conflicto económico con otros Estados es si exporta más de lo que importa. Por lo tanto, es un estado que registra superávit comercial en lugar de déficit comercial. El aspecto relacionado es la capacidad de un Estado para dominar las tecnologías avanzadas del momento.

Como el desarrollo económico de la humanidad se basa en un proceso continuo de desarrollo de las capacidades tecnológicas y técnicas, el mercantilismo llegó a suponer que un Estado era poderoso si estaba en la frontera tecnológica y si tenía industrias basadas en las tecnologías más avanzadas del momento.

Esto es importante porque el primer mercantilismo de los siglos XVI y XVII consistía más bien en controlar los mercados de ultramar mediante la fuerza y asegurarse de que la riqueza que se podía extraer mediante ese control beneficiaba sobre todo a la madre patria. No se trataba tanto de dominar el proceso de desarrollo tecnológico.

Los orígenes del mercantilismo

Los orígenes del mercantilismo, pero también del liberalismo, se remontan a Inglaterra. En gran medida, se puede asociar el mercantilismo con la práctica de la Compañía de las Indias Orientales, que fue la principal empresa mercantilista del siglo XVII en Inglaterra. Sin embargo, también hubo compañías de las Indias Orientales en los Países Bajos en el frente y el alcohol.

El mercantilismo es una doctrina desarrollada primero en Inglaterra, y luego se difunde por toda Europa. Los Países Bajos, Francia, Austria, Prusia, las principales potencias de la época, pero sobre todo los amigos y los Países Bajos fueron las principales potencias que tenían actividades marítimas. Sin embargo, Francia era sobre todo una potencia terrestre, y los Países Bajos eran la típica potencia marítima. Francia también tenía actividades y capacidades marítimas, por lo que también desarrolló una política de mercantilismo. Austria y Prusia eran potencias más terrestres, por lo que participaron menos en este juego en el siglo XVII. Sin embargo, más tarde, Prusia y Alemania adoptaron en el siglo XIX una política mercantilista modificada o al menos una filosofía para organizar su política económica.

Temas

Para el mercantilismo, existe un vínculo aparente entre el poder del Estado y el comercio exterior.[6] Mercantilism and liberalism have two views about how state power and private accumulation relate. For mercantilism the two go together, they are interlinked.

Las Compañías de las Indias Orientales fueron las manifestaciones típicas de la política del siglo XVII y del siglo XVIII. Inglaterra, los Países Bajos y Francia tenían una. Esas compañías dominaban el comercio de ultramar y a distancia con la India. Es importante recordar que esas compañías también ejercían un control administrativo sobre los territorios, dado por los estados con los que se relacionaban con los territorios en los que desarrollaban sus actividades comerciales. Existe un vínculo muy estrecho entre el poder y la abundancia. La misma organización encargada de acumular riqueza en el exterior era también la misma encargada de la administración pública de esos territorios.

El contexto de la aparición de los Estados-nación centralizados

El contexto es el de la aparición de los estados-nación centralizados. A principios del siglo XVII se produce la unión entre Inglaterra y Escocia y el desarrollo de un poderoso aparato estatal centralizado en el Reino Unido. Francia está en el apogeo de su poder absoluto bajo Luis XIV. Los Países Bajos pasan de ser un conjunto de provincias poco relacionadas a un Estado internacional, y así sucesivamente.

Junto con la aparición de los Estados-nación centralizados se produce un proceso de competencia por el gran poder entre esos Estados. Porque este poder se convierte en una rivalidad concentrada entre esos centros de poder. Hay una búsqueda de nuevos mercados de ultramar y, por tanto, la primera ola de expansión colonial.

Las visiones del mundo filosófico más amplio que sustenta el mercantilismo en el ámbito económico son la política real maquiavélica y la hobbesiana. Estas son las tradiciones filosóficas que informan la tradición del realismo en las relaciones internacionales. El mercantilismo tiene claros vínculos intelectuales con la escuela realista de relaciones internacionales.

Visión del mundo de los mercantilistas

En esta visión del mundo, la política internacional y la economía internacional se consideran un juego de suma cero. ¿Qué significa esto? Significa que lo que importa son las ganancias relativas en este juego y no las ganancias absolutas.

El cálculo que hace un Estado al realizar una transacción económica con otro Estado no es tanto lo beneficioso que será para mí. La pregunta es si será más beneficioso para mí que para el otro estado. Esa es la base sobre la que se organizan las transacciones económicas y las relaciones económicas entre estados en esta cosmovisión.

Sólo tiene sentido acudir a una transacción si me voy a beneficiar más que mi llegada. En cuyo caso, uno se pregunta por qué habría una transacción económica en primer lugar, porque si es evidente que las ganancias relativas están de un lado y no del otro, entonces siempre habrá un estado que se negará a participar en transacciones económicas. Por lo tanto, es obvio que para los mercantilistas, la política económica exterior es más bien el asunto de un solo Estado que trata de imponer su política a otros territorios que un proceso en el que los grandes se comprometen en relaciones económicas.

Junto a ello, aparece la idea del interés nacional. El interés de los aparatos estatales centralizados emergentes de la época prevalece sobre los intereses individuales, de acuerdo. No existe una sociedad civil con intereses y derechos propios y diferenciados que puedan ser contradictorios y conflictivos y distintos de los intereses del Estado. Está el Estado, tiene su propio interés, que es el interés nacional, y los individuos dentro de ese Estado tienen que comportarse de una manera que sirva al interés nacional. Es una visión del mundo muy liberal, liberal en el sentido de que no es una visión del mundo antiindividualista.

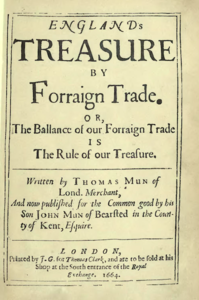

Principales figuras del mercantilismo: Thomas Mun y Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Entre las principales figuras del mercantilismo se encuentra Thomas Mun. Fue un comerciante privado y, sobre todo, uno de los directores de la Compañía de las Indias Orientales. Se dedicó a su práctica y fue también uno de los teóricos de la práctica del mercantilismo. Mun fue miembro del Comité Permanente de Comercio, una comisión real creada en el siglo XVII para asesorar al reino sobre su política exterior. Hacia 1630 publicó El tesoro de Inglaterra por el comercio exterior, que es un tratado sobre cómo la práctica del comercio exterior ha de servir para la acumulación de riqueza al servicio del reino.

En El tesoro de Inglaterra por el comercio exterior, publicado en 1664, Mun afirmó "Por lo tanto, el medio ordinario para aumentar la riqueza y el tesoro es el comercio exterior. En el que debemos observar siempre esta regla: vender más a los extranjeros anualmente de lo que consumimos de ellos en valor".[7][8][9]

La regla de oro del mercantilista es una balanza comercial positiva, es decir, tener un superávit comercial. Para Mun, el medio ordinario para aumentar la riqueza era el comercio exterior y no el desarrollo tecnológico.

El primer pensamiento mercantilista no estaba asociado a la idea de que un Estado estuviera en la frontera tecnológica y tuviera industrias basadas en las tecnologías más avanzadas del momento. Era una visión del desarrollo económico como algo exógeno a la economía nacional. La riqueza se traía del exterior y no era un proceso que se generara endógenamente dentro de la economía nacional.

Otra figura principal es Jean-Baptiste Colbert, que fue ministro de finanzas de Luis XIV. Hoy en día en Francia en lugar de hablar de mercantilismo se habla de colbertismo por las políticas económicas contemporáneas que tienen cierta filiación con las doctrinas de mi país.

Colbert promovió la fabricación dirigida por el Estado: La sustitución de importaciones y la promoción de las exportaciones. La idea de que debía haber políticas para mantener fuera las importaciones y fomentar las exportaciones a los mercados extranjeros. Colbert también desarrolló la idea de que Francia debía tener una balanza comercial favorable. También fue el fundador de la Compañía Francesa de las Indias Orientales.

Curiosamente, en el caso de Colbert, hay un principio de algo diferente, ya que teorizó el proceso de fabricación dirigido por el Estado. El Estado debía intervenir para crear capacidades productivas y tecnológicas al servicio de la nación y del reino. Ahí hay algo diferente de lo que se desarrollará más tarde en las doctrinas del nacionalismo económico y del desarrollismo nacional.

Doctrinas posteriores relacionadas

No son puramente mercantilistas, pero que tienen una clara relación con el mercantilismo y una clara filiación con el mercantilismo.

Nacionalismo económico

El nacionalismo económico está relacionado con Alexander Hamilton en Freidrich List. El contexto del nacionalismo económico es el siglo XIX y el dominio de Inglaterra y, por tanto, la Pax Britannica. Se asocia con la práctica y la teoría del liberalismo. El nacionalismo económico es responsable de la hegemonía de los Estados Unidos en América, en particular después de la independencia y después de la victoria del Norte en la Guerra Civil en 1864. En Alemania, sobre todo después de la creación de la unión aduanera alemana hasta el cierre del mercado alemán a las aportaciones extranjeras en 1879.

Ambos procesos están relacionados con la construcción de la independencia del Estado. En el caso de los Estados Unidos porque también, las colonias se convirtieron en estados de su propia soberanía. La construcción del Estado después de la Guerra de Secesión porque después de la Guerra de Secesión hay un proceso de centralización del poder estatal dentro de la Federación Americana. Por lo tanto, los Estados Unidos pasan de ser un conjunto de una colección descentralizada de estados soberanos a una federación más bien centralizada hacia finales del siglo XIX. Normalmente, en el siglo XIX la gente se refería a los Estados Unidos en plural. A partir de finales del siglo XIX, es más típico hablar de Estados Unidos en singular.

En el caso de Alemania, la unión aduanera de principios de la década de 1820 se consideró la premisa hacia la unificación alemana, un proceso que se inspiró en la Revolución Francesa y en las doctrinas de nación que surgieron de ella y que se difundieron en Alemania a través de las guerras napoleónicas. Tras el proceso de unificación alemana en la década de 1860 que culminó en 1870 con la creación del Imperio Alemán. Hay algo más que un proceso de construcción del Estado, hay un Estado poderoso que emerge en el continente europeo y desplaza a Francia tiene el poder principal en el continente.

En ambos casos, y esta es la ruptura con el mercantilismo primitivo, tanto en Estados Unidos como en Alemania, el nacionalismo económico es visto como un medio para promover la industrialización y el desarrollo económico dirigido por el Estado a través de la infraestructura pública, la inversión y el proteccionismo. Tanto en Alemania como en Estados Unidos, el desarrollo de las redes ferroviarias se produce a finales del siglo XIX sobre la base del proteccionismo.

Se ha visto como una forma de reunirse con la economía nacional para permitir el desarrollo económico nacional. Alexander Hamilton fue el primer Secretario del Tesoro estadounidense. En calidad de tal, escribió un informe sobre el tema de los fabricantes en 1791, titulado Informe sobre el tema de las manufacturas, que fue presentado al Congreso y que incluía todas estas ideas.[10][11]

Se implementaron de inmediato con todo el corazón. El Norte tuvo que ganar la Guerra de Secesión antes de que pudieran aplicarse de manera incondicional. Aun así, coexistieron con el Sur y el liberalismo y con el Sur y el librearadismo durante tres cuartos de siglo.

El desarrollismo nacional

Una doctrina relacionada con el nacionalismo económico del siglo XX es el desarrollismo nacional. Se trata de la respuesta del siglo XX a la hegemonía estadounidense y a las ideologías que la acompañaron después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, a saber, el liberalismo global y el internacionalismo liberal.

Es importante señalar que alguna versión del desarrollismo nacional fue aplicada incluso por los aliados de Estados Unidos, especialmente Francia, Japón y Corea del Sur. Pero el desarrollismo nacional que se aplicó sobre todo en América Latina e India.

La principal práctica asociada al desarrollismo nacional es la industrialización por sustitución de insumos, que consiste en la idea de que si quieres desarrollar tu propia capacidad industrial y tecnológica tienes que mantener fuera, al menos durante un plazo bastante largo, los insumos industriales de otros países que ya dominan las tecnologías avanzadas. De lo contrario, no podrás desarrollar industrias que dominen esas tecnologías y, por tanto, estarás condenado para siempre a consumir los productos avanzados de otros países.

Una teoría asociada es la teoría del desarrollismo nacional es la teoría de la dependencia asociada principalmente a la figura del economista argentino Raúl Prebisch. Prebisch publicó en 1950 El desarrollo económico de América Latina y sus principales problemas que dio origen a la que la hipótesis Prebisch-Singer que sostiene que el precio de los productos primarios disminuye en relación con el precio de los productos manufacturados a largo plazo, lo que hace que los términos de intercambio de las economías basadas en productos primarios se deterioren.[12] El trabajo de Prebisch fue escrito como un informe para las Naciones Unidas, y durante mucho tiempo, entre los años 50 y 70, las Naciones Unidas se vieron impulsadas por el conflicto entre el liberalismo estadounidense y el desarrollismo del mundo en desarrollo.

Liberalismo

Según Oatley, el liberalismo es "una escuela tradicional de una economía política que surgió en Gran Bretaña durante el siglo XVIII como un desafío al mercantilismo el liberalismo afirma que las actividades económicas tienen como objetivo enriquecer a los individuos y que el estado debe por lo tanto pagar para jugar poco papel en el sistema económico. El liberalismo dio lugar a la teoría de la ventaja comparativa. Sugiere que las economías políticas internacionales son cooperativas y no conflictivas".

En casi todos los puntos, las definiciones de mercantilismo y liberalismo son opuestas. La riqueza y el poder no están inextricablemente relacionados. El papel del Estado no es ser un promotor activo del desarrollo económico, sino un promotor pasivo porque tiene que garantizar los derechos de propiedad, las infraestructuras básicas, etc. Tiene que mantenerse al margen del comercio exterior, de la inversión industrial en casa, etc.

Evidentemente, el liberalismo se basa en la idea de que la política internacional no es un juego de suma cero, sino que es un juego de suma positiva. Lo que importa cuando los Estados realizan transacciones económicas entre sí es cuánto ganarán con ello, independientemente de cuánto ganará el otro Estado con ello. Esa es la idea de las ganancias absolutas en contraposición a las ganancias relativas para los teóricos del mercantilismo. La cooperación se vuelve mucho más plausible porque, al fin y al cabo, lo que importa es cuánto bienestar económico adicional obtienen los Estados de las interacciones económicas internacionales y no cuántas ganancias relativas obtienen de ellas.

Orígenes

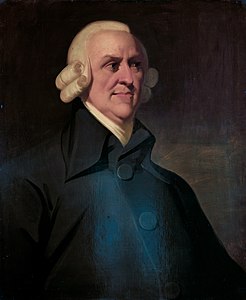

Esta teoría surgió en los siglos XVIII y XIX en Inglaterra. La primera figura destacada del liberalismo es Adam Smith, y la otra figura importante es David Ricardo. Desarrollan una crítica a lo que llamaron el sistema mercantil rentista. En el caso de Adam Smith, asocia esta crítica al mercantilismo con una crítica al colonialismo en América del Norte. Estuvo a favor de la independencia de las colonias americanas.

Temas

El núcleo del liberalismo es la idea del interés y los derechos individuales y el vínculo entre éstos y el bienestar colectivo. El bienestar colectivo se promueve no porque un Estado que encarna el bienestar colectivo se ocupe de ello, sino porque los individuos egoístas persiguen sus propios intereses. Y tienen derecho a hacerlo, y al interactuar entre sí en las personas de sus propios intereses, aumentan el bienestar colectivo, que es el camino hacia la acumulación de la riqueza colectiva.

Teorizaron la idea de que tiene que haber libertad de precios, por lo que la libertad de importación. Los precios no se distorsionan artificialmente para mantener fuera del mercado algunas mercancías en beneficio de otras. También teorizó la superioridad de los mercados y la competencia para organizar la actividad económica y el desarrollo económico.

El gobierno en Adam Smith no está ausente. Tiene un papel fundamental. El Estado es un organizador de los mercados y garantiza las libertades económicas individuales de los derechos de propiedad. El Estado está ahí para asegurarse de que los mercados funcionen correctamente, por lo que el Estado tiene que acabar con los comportamientos de búsqueda de rentas, los buscadores de rentas y los monopolios, etc. El Estado tiene que garantizar los derechos de propiedad para que los derechos individuales estén protegidos y no haya comportamientos depredadores en el mercado porque, de lo contrario, se distorsionan los mecanismos del mercado. Hay una clara conexión entre ese tipo de liberalismo y la tradición antimonopolio que se desarrolla más tarde, a finales del siglo XIX, en los Estados Unidos de América. En Estados Unidos, la tradición antimonopolio es un movimiento populista.

Contexto

El contexto es el de las revoluciones americana y francesa con el fin del absolutismo y el inicio de la democracia de masas y el estado de derecho. En el caso de la Revolución Francesa, hay una contradicción porque, al mismo tiempo, la Revolución Francesa promovió la idea de nación, la idea de interés nacional, la idea de una comunidad nacional, también promueve los ideales de la democracia de masas y las libertades individuales, así como el estado de derecho.

Visiones del mundo

Las cosmovisiones de la Ilustración son la libertad y la propiedad, asociadas al filósofo inglés Lockes del siglo XVII y luego retomadas por los filósofos franceses y los francófonos. Con la revolución racional y Kant, la idea se opone a la visión hobbesiana del mundo basada en los instintos destructivos y agresivos que se alojan en todo ser humano. Para los liberales, los seres humanos son individuos racionales. Los seres racionales saben que su bienestar individual está ligado al bienestar individual de los demás en la sociedad y, por tanto, tienden a cooperar.

Para ellos, la política internacional es un juego de suma positiva que está al alcance de la cooperación interestatal.

Principales figuras: Adam Smith, David Ricardo y Richard Cobden

Adam Smith fue ante todo la principal figura del liberalismo. También fue asesor de los políticos nacionales y su principal obra en relación con la economía política la Investigación sobre la naturaleza y las causas de la riqueza de las naciones publicada en 1776.

"Si un país extranjero puede suministrarnos una mercancía más barata de lo que nosotros mismos podemos fabricar, mejor comprársela con alguna parte del producto de nuestra propia industria, empleada de una manera en la que tengamos alguna ventaja. La industria general del país no se verá así disminuida, sino que sólo se le dejará averiguar cómo puede emplearse con la mayor ventaja".

Esto prefigura la idea de la ventaja comparativa, aunque Adam Smith no tenía una teoría de la ventaja comparativa. Para Adam Smith, el comercio internacional se basaba en la ventaja absoluta. Era bueno para un país comerciar si fabricaba algo mejor que otro país. Si un Estado podía producir un bien de forma más eficiente que otro país. Por lo tanto, dos países podían especializarse en esos bienes.

La riqueza nacional no está asociada al superávit comercial para acumular riqueza porque la riqueza se produce a través del proceso de intercambio. Por lo tanto, basta con que la balanza comercial esté en equilibrio con otros países. Es a través del proceso de intercambio como se acumula la riqueza.

David Ricardo es la otra figura destacada y teórica. Ricardo fue banquero en la ciudad de Londres, economista y diputado. En 1817 escribió Principios de economía política y fiscalidad, en el que teoriza explícitamente la ventaja comparativa. También es un crítico de las Leyes del Maíz que se aprobaron a principios de la década de 1810 y que son aranceles sobre las entradas de grano para proteger a los productores nacionales de cereales. Riccardo también hizo campaña a favor del libre comercio en la abolición de los aranceles.

La ventaja comparativa que desarrolló Ricardo es diferente de la ventaja absoluta. La idea clave es que los países deben especializarse en lo que producen mejor dentro de su propia economía, no en lo que producen mejor en todo el mundo. Incluso si un país es menos eficiente en la producción de algo que produce otro país, debería producirlo si es más eficiente y produce ese bien en lugar de otro dentro de la economía nacional.

La tercera figura es Richard Cobden. Cobden fue un fabricante de Manchester y miembro del Parlamento. Fue el líder de la Escuela de Liberalismo de Manchester y de la liga contra la Ley del Maíz, que logró en 1846 la derogación de las Leyes del Maíz y la abolición del arancel a las importaciones de grano. Con él se inauguró el gran ciclo del libre comercio.

La idea es que el libre comercio promueve la igualdad porque el libre comercio en ese contexto supuso un abaratamiento de los precios de los alimentos para los trabajadores de los centros urbanos que se desarrollaban rápidamente en el Reino Unido en esa época. Por lo tanto, redujo la desigualdad porque los trabajadores verían por la simple abolición de los aranceles que su poder adquisitivo sube, aunque sus salarios se mantuvieran igual. Verían aumentar su poder adquisitivo en detrimento de los terratenientes porque éstos ya no podrían vender sus productos a los precios que vendían antes; o bien se verían aniquilados como estaban o tendrían que vender a un precio más bajo. Por lo tanto, había una transferencia de bienestar del valor económico de los terratenientes a los trabajadores. Así que esa era la idea sobre la que los pactos en ese libre comercio promovían la igualdad en el contexto del siglo XIX en Inglaterra.

Doctrina y manifestaciones posteriores relacionadas

El liberalismo clásico de la economía mundial anterior a 1914 era el de los flujos de capital de comercio relativamente libre en el patrón oro. La etapa actual de la globalización, con el avance del libre comercio y los flujos de capital libres y la ideología asociada del consenso de Washington teorizado en 1990 por John Williamson. Él teorizó que la receta esencial para la evolución económica es liberalizar la economía propia, privatizarla y desregularla.

Consideración general

Existe un paralelismo entre el debate sobre el mercantilismo, el nacionalismo y el liberalismo en la economía política clásica y el debate entre el realismo y el neoliberalismo en las relaciones internacionales y la EPI.

Tanto el mercantilismo como el nacionalismo y el liberalismo son escuelas de pensamiento que aportan poderosas doctrinas y visiones del mundo que siguen formando la política económica. Por ejemplo, en Francia, hoy en día, cuando se trata de discutir la política industrial, todo el mundo habla de Colbert y piensa en la inspiración en la forma en que Colbert promovió la industria en los siglos XVII y XVIII en Francia.

Estas escuelas de pensamiento son menos útiles como marcos analíticos. Tienen una orientación mucho más normativa y positiva. Pretenden comprender el mundo a partir de una serie de preconceptos sobre la organización y el funcionamiento de las sociedades. Como marcos analíticos, no son muy útiles.

La EPI moderna ha intentado desarrollar un enfoque más positivo y de orientación analítica para comprender y analizar el funcionamiento de la economía global y el capitalismo global. El principal beneficio de esto es que permite un análisis que entiende por qué es posible que coexistan elementos mercantilistas y liberales uno al lado del otro en el mismo sistema.

Esto significa que la EPI moderna se basa en la identificación de los bloques o variables políticas y económicas en las que se basa y funciona el capitalismo global. También intenta identificar la forma en que esas variables interactúan entre sí. Las tres categorías principales son variables que utiliza la IPE son:

- intereses, es decir, los actores económicos que componen el sistema y el tipo de intereses que tienen. Rechaza la idea de que algo llamado interés nacional sea primordial, etc. También rechaza la idea de que todos los individuos tienen los mismos intereses básicos que están en la base de la noción liberal de homo economicus fue la base de las nuevas clasificaciones.

- instituciones: las instituciones tienen una influencia independiente en la forma de organizar la interacción económica entre los estados en el capitalismo global.

- Ideas que tienen una influencia independiente en la forma en que se elaboran las políticas económicas exteriores y en cómo interactúan los Estados entre sí en la economía política internacional.

Theoretical evolution

The first theory, mercantilism dates back to 1620s, liberalism to the 1770s, economic nationalism attributed to Alexander Hamilton to the end of the 1790s and beginning early 1800s. With Marxism and neoclassical economics, it leads up to the 1870s. In a way, Marxism sees itself as the continuation of classical political economy, whereas in neoclassical economics sees itself as a bifurcation inspired by the positive sciences.

Then there is a new version of all those theories coming up. From the early 1900s, IR liberalism and idealism spring up. The high point of IR liberalism and idealism is in the 1920s and the League of Nations. Since the 1930s realism and new realism began to develop and developed as a critique of idealism and a critique of the League of Nations' failure. The major work The Twenty Years' Crisis: 1919–1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations written by E. H. Carr. The critic is that with the League of Nations, the war did not stop between the main powers between 1919 and 1939. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace written by Hans Morgenthau published in 1948 is another major work which introduces the concept of political realism, presenting a realist view of power politics.

Since the 1970s and this is closely associated with IPE development, neoliberal institutionalism has developed. Neoliberal institutionalism to a large extent informs how IPE tries to analyse global capitalism and the functioning of the international community.

It is important to be able to locate in time when such a theory emerges and become dominant and declines.

Neorealism

From early IR to IPE, how did we move from a situation in which realism was the main way international relations were studied to the detailed IPE development in the 1970s and the 1990s?

Neorealism was the dominant IR paradigm of the 1930s and the 1970s. It is important to put that in perspective with real-world developments. Because that intellectual hegemony coincides with the interwar breakdown of global capitalism and the rise of economic nationalism, national developmentalism and the primacy given to domestic policy autonomy over external stability that characterised the period between the early 1930s and the early 1970s. Both one part of the interwar collapse and embedded liberalism. Although it was a compromise between domestic policy autonomy and external stability, it gave primacy to domestic policy.

What were the main theoretical aspects of realism and neorealism?

The basic premise is that being some national system is anarchic. What does that mean? It means that there is no world government, there is no world rule of law, and therefore there is no mechanism to impose cooperation among sovereign states. Interaction between sovereign states is not based on the rule of law. It is not based on norms on rules and whatever it is based on raw power. The way states interact with each other is extremely different from how individuals interact or groups of individuals interact within a given state. The basic concept here is external sovereignty.

Therefore the basic variable that determines how the international system and by extension of the international particular economy works is the distribution of power among states.

If the basic way in which state interacts, how they relate to each other in power returns, and how power is distributed among them is the main determinant of how they interact. There is also the theory about what is the distribution of power that is most likely to lead to stability: unipolar, bipolar, multipolar, etc. Realists don’t agree with each other, but the basic terms of the debate are the same.

Along with this external sovereignty is also the idea that states are unitary actors with national interest. That national interest determines their behaviour. This is an extension of the idea of sovereignty. There is one sovereign state, and the realists take that to mean that the state is a single actor with a single way of perceiving things of understanding things and defining its own interest. For most realists, the national interest is first and foremost the preservation of state sovereignty. Then hinges on the accumulation of power and so the national interest is about accumulating power within the international system. Here and this is not the case with neoliberalism, states are not driven by contradictions and different bureaucracies within the state apparatus. All work towards the same goal. There is no contradiction between state managers, they don’t pursue different goals, and civil society interests do not permeate the states. They are not amenable to be influenced by the interest group.

Relative gains and international relations are a zero-sum game. International relations are basically conflictual. Neorealism is in line with the basic tenets of mercantilism and economic nationalist stock. If economic power is the main variable, then it is important to master the day’s advanced technologies. What matters is having a share as big as possible of global production and global trade as a state can. Those are indicators of power for realists as they are former mercantilists and economic nationals. There is also a focus for realists on high versus low politics. High politics is anything it has to do with war, security and diplomacy, whereas low politics is politics has to do with economic aspects of international life.

Neoliberalism and its critics in the 1970s

The main dimensions of neoliberalism were criticised heavily in the 1960s and the 1970s. Notably, IR is basically conflictual in line with mercantilism and economic nationalism and focuses on high versus low politics.

The main breach in academia’s intellectual hegemony began in the 1950s and the 1960s with many cooperation cases and not rivalry in international relations. The main one was the détente which is the process of thawing of relations between the USSR and the USA and by extension between the USSR block and the American-dominated block. That included the SALT agreements inter alia. There were also many other instances of integration among states through trade cooperation within the GATT and the Comecon in the Soviet bloc. There is also the European integration which is very important because just a few years after Germany has occupied France, there was an agreement between those two states to begin to build a European federation. As the process of European integration developed after the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and throughout the 1960s successfully, there was this idea that international politics does not have to be conflictual and cases of deep cooperation amongst states can take place. This challenge the idea that international relations are basically conflictual.

The idea that neorealism is in line with the basic tenets of mercantilism and economic nationalism thoughts were challenged by the gradual opening of national economy throughout the 1960s and the 1970s. That provided the basis for the takeover of the fourth stage in the history of global capitalism, namely the second globalisation from the 1970s onwards.

It is the case that despite the fact that and better liberalism was to a large extent dominated by economic nationalism closure and so on, it also so very rapid rates of growth in international trade international investment and from the late 1960s onwards international capital flows.

These developments challenged the notion that the future of global capitalism’s future would be inextricably linked to the practice of economic nationalism that prevailed in the 1930s. That challenges the idea of the alignment between neorealism and economic nationalism.

High politics’ primacy over low politics came on the challenge because low politics became much more salient throughout the 1960s. First, because of the end of the Bretton Woods system. In the 1970s the group of 77 developing nations within the United Nations in the 1970s demanded the setup of a new international economic order which is the idea that international economic relations should be organised differently from the blueprint that was set down by the United States in the late 1940s. Finally, after the Bretton Woods system’s collapse, the high salience of European monetary cooperation and integration issues came to play a significant role.

The combination of these factors from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s showed that low politics issues could be very important in the way states interact with each other in the international system.

These three challenges created the first breach in the academic hegemony of realism within international relations. But neorealism was not dethroned overnight. The development of IPE in the 1970s was very much influenced by the debates over the pattern of neoliberalism. The first major questions and major theoretical perspectives that were thrown out by the development of IPE had clear links to the main questions asked by neorealists in their attempt to understand the international system.

The first one was the challenge to the idea that international relations were conflictual. One of the main debates was whether states cooperate. Still, in other cases, they do compete what determines when it is that states compete and when it is that states cooperate.

In the 1970s IPE focused on the interstate level. To typical IR questions such as how does the distribution of power affect international relations, there are the associated IPE questions that dominated the seventies in the eighties. To the question of how the distribution of power affects international relations, the associated question became what determines international economic stability or crises and what determines economic openness or closure. To the question is cooperation possible under anarchy, the modified IPE questions were just to external imbalances to ensure stability, who makes sure that there is a cooperative outcome that ensures there is stability in the system and who sets for an economic policy.

As neorealism hegemony was challenged, the challenge brought and in the 1980s other aspects of the neorealist paradigm came under attack. Another dimension was introduced to IPE in the 1980s. It is a fundamental dimension because this is the main focus of American IPE with foreign economic policy's domestic sources. That was based on the challenge to the idea of States as unitary actors and behave according to the national interest. That is not self-contradictory.

To typical IR questions such as what is the national interest, the modified IPE question would be who sets for an economic policy. The assumption being that different groups of actors may have different interests. So there may be a conflict over who sets for an economic policy whereas for their realists, and that is not even a question, state managers who are imbued with state rationality and whom all push in the same direction set for an economic policy. A second typical IR question is openness and closure in line with the national interest that became who benefits from openness and closure. Openness and closure do not necessarily align with the national interests with which all domestic groups align, but can be to the benefit some groups into the detriment of others. Therefore, there is a conflict over whether a state should open its economy up or barricade itself behind protective barriers.

This is how theoretically IPE emerged based on a challenge to the hegemony of realism and neorealism within international relations discipline.

Power and hegemonic stability

The theoretical perspectives

We are now going to look at these different theoretical perspectives within American IPE. We will look first at the theoretical perspectives that have to do with the systemic level, which is the level of interaction between states. The second part will be about the domestic sources of foreign economic policy. Finally, we will present an overview of the main theoretical perspectives in American IPE such as it has developed since the 1970s.

The link between power and hegemonic stability

The first debate that clearly had to do with the systemic level was the foundational debate on the international political economy. It was the debate about the link between power and hegemonic stability and what became known as a hegemonic stability theory with both its liberal and realist variants.

This debate was launched by the publication of Charles Kindleburger’s book World in Depression, 1929-1939 published in 1973. Kindleberger a liberal reading of economic stability theory. Kindleberger was very much a new dealer who was involved with the administration of the Marshall Plan in Europe in the late 1940s. He was imbued with the liberal internationalist spirit that informed American foreign policy from the 1940s onward.

Kindleberger studied why the Great Depression happened in the 1930s, and he attributed it to what IPE scholars refer to as a hegemonic transition. This is the idea that Pax Britannica was on the decline and had almost disappeared in the 1930s, but Pax Americana was not yet there. In the vacuum between the two conditions were created for the break-up of the fragmentation of global capitalism and that contributed to the Great Depression. For Kindleberger, it was a way of indicating what he did when he was in the Treasury Department in the 1940s because the policy he pursued as a US state official was liberal internationalism. He was in marked contrast to the isolationist policies of the 1930s.

Stephen Krasner published in 1976 State Power and the Structure of International Trade which is an article about the determinants of free trade openness.[13] Krasner attempts to find a correlation between the rise and decline of precision American hegemony and the trend towards open and closure in the world economy. Krasner being realist, he associates openness with the rise and stability over hegemonic power.

In both versions of the theory, the basic idea is that international economic stability and openness and an open international economy both require action by one hegemonic power: Pax Britannica before the First World War Pax Americana since the Second World War.

Theoretically, the assumption that there had to be one hegemonic power came under attack in the 1980s. Some people said that theoretically, it is possible to have a bipolar world that is still stable because both of these powers provide the public goods that underpin the global system’s stability. That’s very much a theoretical debate that doesn’t have a historical application. Therefore, it is not that important in the development of a demonic stability theory.

Very quickly the debate about the conditions of stability mutated into a debate about the conditions of stability of the contemporary international political economy because along with the dollar crisis of the 1970s a debate about the decline over American hegemony has emerged. In the 1970s 1980s, most scholars were convinced that American hegemony was on the decline. Some predicted the collapse of the dollar standard and so on, in particular realists. A major book by historian Paul Kennedy published in 1988 titled The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. Kennedy attempts to show how America was on the verge of a breakdown of hegemonic positions within the international system just as Britain, the Netherlands, France and so on before it had gone through the same process. It should be noted that this book was published two years before the collapse of the Soviet bloc. It is a major thesis rejected now. There is a debate about the state of American power today within IR, but the consensual position is an American hegemony is still very much alive.

The key thing about the development of American IPE is the debate on the decline of the US hegemony throughout the debate about the conditions that couldn’t ensure continued stability despite the fact that there was no longer one hegemonic power willing to provide that stability and to bear the cost of providing that stability.

That debate is best captured by the book by Robert Keohane titled After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. That is a key statement of neoliberal institutionalism. The basic argument is that the sets of relations and institutions established by hegemon to ensure stability will live on after the decline of that hegemon’s power because for the other states in the system the maintenance costs of that regime are lower than the costs that a breakup of that regime would entail. This is a kind of inertia that characterises the institutions set up by the hegemon. That will ensure that stability will prevail even though the hegemon is still not around to enforce those relations and those institutions.

International Institutions

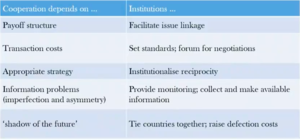

This table is a summary of how neoliberal institutionalism theoretically developed.

Neo-liberal institutionalism is about international institutions and how international institutions can be designed to advance cooperation between states. There are five ways in which institutions can be designed to ensure that those aspects of cooperative behaviour are guaranteed.

The first one is the payoff structure. The payoff structure basically is a fancy way of saying the list of preferences in descending order that states have about how international economic relations should be organised. The payoff structure has to match. This is very much based on game theory. A lot of neoliberal institutions are based on game theory.

The idea is that preferences among states have to match. If they don’t spontaneously match, there has to be a process through which they can be broad closer together with a way through which states can agree to forgo their first preferences in favour of other preferences but can enable the international system to work based on cooperation. Institutions do that by facilitating issue linkage. Linkage is a major feature of the theory of interstate bargaining. Institutions are meant to make sure that when states sit down at the bargaining table, they sit down to talk about both good exchanges and financial services, and so on. So states can make concessions to each other across a spectrum of items that make up the bargaining agenda.

The next issue on which cooperation depends is transaction costs. Transaction cost is a concept that comes from economics. It is the idea that for market transactions to be beneficial, there are costs associated with realising a market transaction, and the costs have to be lowered for the transaction to be worth it. A key transaction cost obviously is distance. There are other types of transaction costs that have to do with the information. International institutions are there to set standards and ensure that parties in international economic transactions can have confidence that the goods and services they exchange leave up to a minimum set of standards.

Institutions also provide a forum for negotiations. They make it easier for states to come to the bargaining table. In contrast, without international institutions and fora for negotiations, it might prove difficult for states to find their way to the bargaining table.

Appropriate strategies are the fact that states need to know that if they make a concession they will get a concession back and anticipate the reaction by another state to a decision that they will take. That is the issue of reciprocity. If we look at the feature the principles of the WTO, reciprocity is one of them. If you give something to a state, you expect the same thing back which facilitates the exchange of concessions.

Information problems, from economics, is mostly information imperfection. It is when parties to a transaction are not fully aware of the transaction’s different aspects. What institutions do is to monitor and gather information to make it available to all parties involved. They can bring down information asymmetries and information imperfections. So they are producers and distributors of information regarding international economic transactions.

Finally, what scholars in IR refer to as the shadow of the future is the idea that a state will interact with another party differently if it knows that down the road the sate will have to repeat the interaction and it will have to transact with that party again. Institutions do that by raising defection costs and tie countries together. Defection costs are the reputation costs that are associated with the WTO, for example, making known to the world that the American or Chinese government has broken the rules.

Unpacking the ‘National Interest’

We will open up the black box of the state and the national interest and understand and identify foreign domestic sources of foreign economic policy.

One aspect of that is identifying the actors that collectively act to influence the definition of foreign economic policy. One way of looking at that is by classes or production factors in some cases, capital labour and landowners. Another is by broad sectors of economic activity. That can be export-oriented sectors of the economy, input competing sectors of the economic sectors that compete with inputs from abroad, non-tradable sectors that do not engage in international trade, the financial sector, the capital intensive industrial sector and so on.

Sectors are a finer grain characterisation of the way economic actors grouped together than classes. Classes are the more macro level, sectors are the more massive level. There are also firms, which is the very individual level, the micro-level. There are distinctions between large transnational corporations, small-medium enterprises (SMEs). Cooperation is also operated through supply chains and others are. Within the same branch of activity, there may have conflicting interests.

Another aspect of this is how our preferences are aggregated. It is not because actress exists that they have the same capacity to come to an agreement about what their collective interest is and also to pursue that interest with state managers. That refers to collective action theory and the concept of organisational capacity. The idea is that the larger the group’s size, the more difficult it is to find a consensual position and pursue collective activity, advance that collective interest and the asymmetry between different groups, and so on.

Small groups of very large actors have greater organisation capacity than big groups of very small actors. Typically the distinction is between monopolistic corporations, on the one hand, and consumers that are each individual in the economy. Therefore they have very little collective organisational capacity.

Another aspect that determines how preferences are aggregated is domestic institutions. The basic distinctions are the distinction between democratic and authoritarian regimes but also within democratic regimes the distinction between majoritarian versus proportional electoral institutions, but also within democratic regimes the way in which bargaining institutions allow for coordination or competition in which setting systems.

Explaining US foreign economic policy

We will take a look at explaining the US foreign economic policy in the twenties, thirties and the seventies.

The first article illustrating this example is Sectoral Conflict and Foreign Economic Policy, 1914-1940 written by Frieden on the US interwar policy.[14] Frieden explained the conflict between isolationism and liberal internationalism in US foreign policy in general. Frieden says this is not about schools of thought within the American state apparatus or within the American party system. This was first and for most about a split within the US’s business community. In particular between the internationalised interests within the American capitalist class and the domestically oriented interests within the American capitalist class. He shows that throughout the twenties and the thirties there was a conflict between those two. Gradually the internationalised segment of the American capitalist class won the day because it gradually became more important in terms of the overall domestic economy. There was a crisis that crystallised the conflict between the two. Therefore throughout the second part of the thirties, the liberal internationalists gradually managed to take over the United States’ foreign policy.

Helen Milner published in 1988 Resisting protectionism: Global industries and the politics of international trade which is a study on protectionism versus free trade both in the interwar period and in the 1970s.[15] She shows that the conflict between protectionism and free trade had to do with the extent to which American cooperations in different sectors of the economy had become internationalised or not. Milner shows that first between the twenties and the seventies, the American economy's overall exposure to the international economy had gone up and explains why in the seventies protectionism did not prevail as opposed to the twenties overall. Then she shows that even within periods, the same distinction applies. Even in the twenties in that minority of sectors in which cooperation have already become transnational internationalised, free trade prevailed over protectionism. It is a very similar argument that Frieden puts forward that applied to trade policy, whereas Frieden has a broader scope.

Other aspects of domestic politics

Another aspect of domestic politics that obviously has been studied and affects how global capitalism functions is institutions. Scholars distinguish between authoritarian and democratic regimes and then within regimes between majoritarian and proportional systems. The basic idea is those authoritarian and majoritarian systems (majoritarian systems are for example the House of Representatives in the United States, the House of Commons in the United Kingdom, the National Assembly in France as opposed to proportional systems like the German federal parliament).

The main assumption and idea is that authoritarian majoritarian regime are more amenable to be captured by special interests and therefore they are more likely to pursue protectionism. Whereas proportional single constituency electoral systems like the American presidency for example, are most sensitive to pressure by non-concentrated groups like consumers, they are more likely to pursue openness because openness is the policy that benefits consumers the most it lowers prices.

Another aspect is so-called to level games. The idea that there is an interaction in the way the interstate system functions and the way the domestic system functions. Executives’ governments that find themselves between those two levels, the domestic and the interstate level, can both benefit. They can argue to their domestic constituents that the interest system constrains them in a way that means that they have to the policies that are not necessarily popular with domestic electors. Still, they can do the same at the interstate level where they can argue in bargaining processes that they are willing to make concessions. Still, they won’t have a majority to ratify those concessions domestically because they are not popular. Therefore they can use that as a bargaining chip in interstate negotiations.

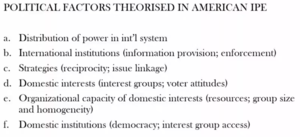

Political factors theorised in American IPE

That is a list of the main factors that have been theorised and continue to a large extent to be theorised in American IPE. We can see that there is a blend of ideas coming from realism and from and from neoliberalism, particularly neoliberal institutions. Clearly, the idea that the distribution of power within the international system affects the way the international political economy works is still very much around. Scholars still debate to a lesser extent than what they did in the 1970s, but they still debate that aspect of the problem.

B is the way international institutions affect the way the international political economy works. The basic question is how can international institutions be made to promote cooperation and therefore openness.

C is the way strategic behaviour between states can lead to cooperation or conflict.

D is how domestic interests influence the way foreign economic policies made and how states interact with each other.

E is a sub-theme of d, which is the organisational capacity of domestic interests and how it affects the way domestic interests can influence an economic policy and have domestic institutions.

Anexos

Referencias

- ↑ Profil de Christakis Georgiou sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Profil de Christakis Georgiou sur le site de Mediapart

- ↑ Publications de Christakis Georgiou sur Cairn.info

- ↑ Publications de Christakis Georgiou sur Academia.edu

- ↑ Oatley, T. (2018). International Political Economy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351034661

- ↑ Viner, J. (1948). Power versus Plenty as Objectives of Foreign Policy in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. World Politics, 1(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009156

- ↑ Thomas mun: England’s treasure by foreign trade (1664) from Thelatinlibrary.com website: http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/readings/mun.html

- ↑ Perrotta, C. (2014). Thomas Mun’sEngland’s Treasure by Foreign Trade: the 17th-Century Manifesto for Economic Development. History of Economics Review, 59(1), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/18386318.2014.11681258

- ↑ Muchmore, L. (1970). A Note on Thomas Mun’s “England’s Treasure by Foreign Trade.” The Economic History Review, 23(3), 498. https://doi.org/10.2307/2594618

- ↑ IRWIN, D. A. (2004). The Aftermath of Hamilton’s “Report on Manufactures.” The Journal of Economic History, 64(3), 800–821. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022050704002979

- ↑ Nelson, J. R., join(' ’. (1979). Alexander Hamilton and American Manufacturing: A Reexamination. The Journal of American History, 65(4), 971. https://doi.org/10.2307/1894556

- ↑ Prebisch, R. (1950). The economic development of Latin America and its principal problems. Economic Commission for Latin America. Retrieved from https://repositorio.cepal.org//handle/11362/29973

- ↑ Krasner, S. D. (1976). State Power and the Structure of International Trade. World Politics, 28(3), 317–347. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009974

- ↑ Frieden, Jeff. “Sectoral Conflict and Foreign Economic Policy, 1914-1940.” International Organization, vol. 42, no. 1, 1988, pp. 59–90. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2706770.

- ↑ Milner, Helen V. Resisting protectionism: global industries and the politics of international trade. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1988. Print.