Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences

Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory ● The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic ● Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory ● The notion of "concept" in social sciences ● History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts ● Marxism and Structuralism ● Functionalism and Systemism ● Interactionism and Constructivism ● The theories of political anthropology ● The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas ● Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science ● An analytical approach to institutions in political science ● The study of ideas and ideologies in political science ● Theories of war in political science ● The War: Concepts and Evolutions ● The reason of State ● State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance ● Theories of violence in political science ● Welfare State and Biopower ● Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes ● Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences ● The system of government in democracies ● Morphology of contestations ● Action in Political Theory ● Introduction to Swiss politics ● Introduction to political behaviour ● Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy ● Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation ● Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation ● Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations ● Introduction to Political Theory

The electoral system is an essential element of representative democracy and can have a significant impact on the political, social and economic landscape of a country. There are several types of electoral system, each with its advantages and disadvantages.

To fully understand electoral systems, it is essential to first understand the concept of representative democracy and the role that free elections play in it. Representative democracy is a type of democracy in which citizens elect representatives to govern them and make political decisions on their behalf. These representatives are usually elected in free and fair elections, where every citizen has the right to vote. Free elections are a key element of representative democracy. They allow citizens to choose their political representatives and have their voices heard in the political process.

Free elections generally involve:

- The right to vote: every citizen has the right to vote without discrimination on the basis of race, gender, religion, etc.

- Secrecy of the vote: citizens must be able to vote without fear of reprisal or pressure.

- Equality of the vote: each vote has the same value.

- Fair competition: all political parties and candidates have the right to compete in elections and have fair access to the media and the campaign.

- Transparency and integrity of the process: the electoral process must be transparent and free from fraud.

The selection of candidates or parties by the citizens' vote is at the heart of representative democracy. However, the electoral system used for this selection may vary from one country to another. Each of these systems has its own implications for political representation, the stability of government and other aspects of political, social and economic life.

Elections are a fundamental feature of democracy and perform a number of key functions, both practical and symbolic.

- Practical (Selection of political elites) Elections are the mechanism by which the citizens of a democracy choose their leaders. This means that they play a crucial role in selecting the political elites who govern the country. Through elections, citizens have the opportunity to choose the individuals and political parties that best reflect their interests and values. Elections also make it possible to hold political leaders accountable for their actions: if they fail to meet citizens' expectations, they can be replaced at the next election.

- Symbolic (legitimisation of the political system): In addition to their practical role, elections also have major symbolic importance. They are an affirmation of the will of the people and a means for citizens to express their support for or opposition to the current direction of the country. Elections confer legitimacy on political leaders and the political system as a whole, because they demonstrate that these leaders have been chosen by the people and not imposed from outside. In addition, participating in elections can reinforce a sense of belonging to a political community and a commitment to democratic values.

Elections are both an essential tool for the practical functioning of democracy and a symbolic ritual that reinforces the legitimacy of the political system.

Understanding electoral systems[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

For most citizens in a democracy, voting in elections is their main channel for political participation. By voting, citizens express their preferences for certain candidates, parties and policies. It is a powerful and direct method of influencing the government and direction of the country.

This table shows average voter turnout over several decades.

In general, voter turnout varies considerably from one country to another and from one election to another. Many factors can influence voter turnout, including the age of the population, the level of education, the electoral system, voter registration laws, the competitiveness of elections, and more.

In addition, in many countries there has been a downward trend in voter turnout in recent decades. This has led to concerns about civic engagement and the legitimacy of the political system. However, this trend is not universal and voter turnout has increased in some countries and in some elections.

Voter turnout varies greatly from one country to another, and several factors may explain these variations:

- Compulsory voting: In some countries, such as Belgium, Austria and Cyprus, voting is compulsory, which leads to higher voter turnout rates. In these countries, citizens are legally obliged to take part in elections and can be penalised if they fail to do so.

- Direct democracy: In other countries, such as Switzerland, the existence of direct-democratic mechanisms can also increase voter turnout. In Switzerland, for example, citizens can take part in referendums that can directly influence the country's legislation and policies. This gives citizens a sense of direct control over policy, which can encourage them to participate more actively.

These two factors, among others, can have a significant impact on voter turnout. It is important to note that each country has a unique political context and a combination of factors that influence voter turnout.

A country's electoral system determines how votes are converted into parliamentary seats. There are several types of electoral system and each has different implications for parliamentary representation. Here are some examples:

- Majority system: In this system, often used for parliamentary elections in two-party systems of government, the candidate who wins the majority of votes in a constituency wins the seat for that constituency. There are variants, including first-past-the-post (as in the US and UK) and second-past-the-post (as in France).

- Proportional system: In this system, seats are distributed in proportion to the number of votes received by each party. For example, if a party gets 30% of the votes, it should get around 30% of the seats. This allows better representation of minority parties, but can also lead to a fragmented parliament with several small parties. Examples of countries using this system are Germany and Spain.

- Mixed system: Some countries use a combination of the two previous systems. For example, in Germany, half the seats in the Bundestag are allocated according to the majority system, while the other half are allocated according to the proportional system.

- Multi-round voting: In some countries, if no candidate obtains an absolute majority in the first round of voting, a second round is organised between the leading candidates. This is the case in France for its presidential elections.

Each electoral system has its advantages and disadvantages, and the choice of system can have a major impact on the political landscape and the stability of government.

Classification of electoral systems[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The electoral system has a significant influence on several aspects of a country's political life:

- Accuracy of representation: The electoral system determines how voters' preferences are translated into parliamentary seats. For example, in a proportional system, parliament is likely to more accurately reflect the diversity of voters' opinions, whereas a plurality system may distort representation in favour of the major parties.

- Number of parties: The electoral system can influence the number of parties in a political system. Majority systems tend to favour two-party systems, while proportional systems can allow more small parties to win seats.

- Type of government : The electoral system can also have an impact on the type of government formed. Majority systems tend to favour single-party governments, while proportional systems can lead to coalition governments.

- Political stability: The electoral system can influence political stability. Majority systems, which tend to produce strong single-party governments, can be more stable. On the other hand, proportional systems, which can produce coalition governments, may be less stable, but may also facilitate greater consensus and inclusiveness.

- Political results (output): Finally, the electoral system can influence the policies that are implemented. For example, coalition governments formed under proportional systems may require political compromises, while single-party governments formed under majoritarian systems may have more latitude to implement their agenda.

It is therefore crucial to understand the electoral system when analysing a country's politics.

Electoral systems can vary greatly from one country to another, but they can generally be divided into two broad categories: majoritarian systems and proportional systems.

- Majority (or plurality) systems: In these systems, the candidate or party with the most votes in a given constituency wins the seat. This system generally favours the major parties and can lead to one-party governments. It is generally simpler, but can lead to a less proportional representation of votes in parliament. Examples of countries using this system include the United Kingdom and the United States.

- Proportional systems: These systems aim to distribute seats in proportion to the number of votes received by each party. Thus, if a party receives 30% of the votes, it receives approximately 30% of the seats. This system tends to allow better representation of minority parties, but it can also lead to a fragmented parliament with several small parties, and often to coalition governments. Examples of countries using this system include Germany, Spain and Sweden.

There are also mixed systems that combine elements of majority and proportional systems. For example, Germany uses a mixed system where one part of the seats is allocated on a majority basis, while the other part is allocated on a proportional basis. Each system has its own advantages and disadvantages, and the choice of system can have major consequences for a country's political landscape.

In many countries, we have seen a tendency to move from a majoritarian to a proportional system over time. This shift may be due to a number of factors:

- Fair representation: proportional systems are often seen as fairer because they ensure a more accurate match between the percentage of votes a party receives and the number of seats it gets in parliament. This can make voters feel that their vote has more impact and can help to increase the diversity of voices and opinions represented in parliament.

- Governmental stability: Although majoritarian systems can promote stability by allowing the formation of single-party governments, they can also lead to political domination by one or two major parties. Proportional systems, while they can lead to coalition governments and greater political fragmentation, can also foster greater collaboration and political consensus.

- Representation of minorities: Proportional systems can provide better representation for minority groups and smaller parties, which can be particularly important in ethnically or culturally diverse societies.

- Response to socio-political problems: Sometimes changes in electoral systems can be a response to specific political problems, such as ethnic conflict, political polarisation or general dissatisfaction with the existing political system.

However, it is important to note that moving from a majoritarian to a proportional system is not a universal solution to all political problems. Each system has its own advantages and disadvantages, and the choice of electoral system must be adapted to the specific political, cultural and social context of a country.

The table below provides information on the electoral systems in place in the various European countries. The right-hand column lists the changes made to the electoral systems in these countries, highlighting a certain stability in these changes.

In Europe, many countries use proportional electoral systems for their parliamentary elections. For example, Germany, Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands all use proportional systems. A few countries, such as the UK and France, use majoritarian or semi-majoritarian systems. France, for example, uses a two-round plurality system for its parliamentary elections, while the UK uses a first-past-the-post system. Some countries use mixed systems, such as Germany, which combines a proportional system with a majority system.

However, these systems may vary according to the level of government (national, regional, local) and the type of election (legislative, presidential, municipal, etc.). In addition, some countries have made adjustments to their electoral systems over time in response to specific concerns, such as increasing representativeness or reducing political fragmentation. As far as the stability of electoral systems is concerned, it is true that most countries tend to keep the same electoral system for long periods, as any change generally requires a broad political consensus and can have significant implications for the country's political landscape.

Most countries tend to maintain the same structure of their electoral system over long periods of time. Changes in electoral systems can be difficult to implement, as they often require political consensus and can have significant implications for the political landscape. The stability of electoral systems can also be seen as an indicator of a country's political stability. A stable electoral system can provide a predictable framework for political competition and contribute to citizens' confidence in the electoral process. However, some countries may choose to change their electoral system in response to specific political problems or in order to promote fairer representation. For example, a country might move from a majoritarian to a proportional system to improve the representation of minority parties in parliament. Finally, it is also important to note that even within the same electoral system, there can be significant variations in specific rules, such as the number of seats to be contested, the threshold for winning a seat, or the way in which votes are counted. These details can also have a significant impact on electoral results.

Several countries have significantly modified their electoral systems over the course of their history to adapt to new political and societal realities. After the Second World War, Greece went through a series of major political changes, including several coups d'état and civil war. In 1974, after the fall of the military dictatorship, Greece adopted a new proportional electoral system for parliamentary elections. Since the 1990s, Italy has undergone several reforms to its electoral system. The pure proportional system, in place since the end of the Second World War, was replaced in 1993 by a mixed majority-proportional system. However, this system was subsequently changed several times, reflecting the country's political instability. After the end of the communist regime in 1989, Poland adopted a proportional electoral system for parliamentary elections. This change was part of the major political reforms that accompanied the country's transition to democracy. After the fall of the communist regime in 1989, Romania also introduced major political reforms, including the switch to a proportional electoral system. These examples show that electoral systems are not set in stone, but can evolve according to political and societal circumstances.electoral reforms are generally adjustments within the same type of system rather than radical changes from one type of system to another. There are several reasons for this:

- Institutional stability: Electoral systems are fundamental elements of a country's institutional architecture. Radical changes can be disruptive and may require substantial changes to laws and institutions.

- Political consensus: Major changes in electoral systems generally require a broad consensus among political actors. This can be difficult to achieve, especially in divided or polarised political systems.

- Voter preferences: Voters may be used to a certain type of electoral system and may resist radical changes.

- Predictability of outcomes: Political parties may prefer an electoral system that is predictable and allows them to maximise their chances of success.

However, it is important to note that even relatively minor reforms can have significant impacts on electoral outcomes and the composition of government. For example, changes to the electoral threshold or vote counting rules can influence the number and type of parties that gain representation in parliament.

Systèmes majoritaires[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Le système majoritaire est un type de système électoral où le candidat ou le parti qui remporte le plus de voix dans une circonscription gagne le ou les sièges correspondants. Il existe deux formes principales de systèmes majoritaires : le scrutin uninominal majoritaire à un tour, également connu sous le nom de "first-past-the-post", et le scrutin uninominal majoritaire à deux tours.

- Scrutin uninominal majoritaire à un tour : C'est le système le plus simple, où le candidat qui obtient le plus de voix dans une circonscription est élu, même s'il n'a pas obtenu une majorité absolue des voix (plus de 50 %). Ce système est utilisé, par exemple, au Royaume-Uni et au Canada.

- Scrutin uninominal majoritaire à deux tours : Dans ce système, si aucun candidat n'obtient une majorité absolue au premier tour, un second tour est organisé entre les deux candidats qui ont obtenu le plus de voix. Le candidat qui obtient le plus de voix au second tour est élu. Ce système est utilisé, par exemple, en France.

Les systèmes majoritaires ont tendance à favoriser les grands partis et à produire des gouvernements stables, mais ils peuvent aussi entraîner une sous-représentation des petits partis. En outre, ils peuvent aboutir à une distorsion entre la proportion des voix obtenues par un parti et la proportion des sièges qu'il obtient au parlement.

Scrutin uninominal majoritaire à un tour[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Le scrutin uninominal majoritaire à un tour, souvent appelé "first-past-the-post" (FPTP) en anglais, est un système électoral simple où l'électeur vote pour un seul candidat dans sa circonscription. Le candidat qui obtient le plus grand nombre de voix est élu, même s'il n'obtient pas la majorité absolue (plus de 50% des voix).

Il s'agit d'un système couramment utilisé dans les pays anglo-saxons comme le Royaume-Uni, les États-Unis, le Canada et l'Inde.

Voici quelques-unes de ses caractéristiques principales :

Avantages :

- Simplicité : C'est un système facile à comprendre pour les électeurs et facile à mettre en œuvre pour les organisateurs des élections.

- Gouvernements stables : Il favorise généralement les grands partis et tend à produire des gouvernements stables car un seul parti obtient souvent une majorité de sièges.

- Liens forts entre élus et électeurs : Comme chaque député représente une circonscription spécifique, il peut y avoir un lien fort entre l'élu et ses électeurs.

Inconvénients :

- Représentativité : Il peut y avoir une distorsion importante entre la proportion des voix obtenues par un parti au niveau national et la proportion de sièges qu'il obtient au parlement.

- Marginalisation des petits partis : Les petits partis, même s'ils obtiennent un pourcentage significatif des voix au niveau national, peuvent se retrouver avec très peu de sièges ou aucun siège du tout.

- Gaspillage de voix : Les votes pour les candidats qui ne sont pas élus sont essentiellement "gaspillés", c'est-à-dire qu'ils n'ont pas d'impact sur le résultat final. Cela peut décourager la participation électorale.

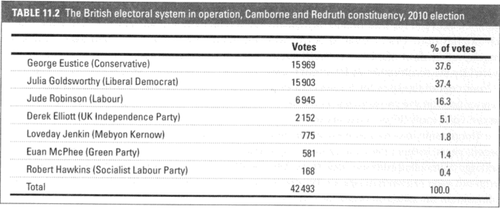

Le candidat conservateur a gagné l'élection dans la circonscription de Camborne et Redruth en 2010, même si moins de 40% des électeurs ont voté pour lui. Le candidat libéral-démocrate, malgré un score presque équivalent, n'a obtenu aucun siège, laissant les électeurs qui ont voté pour lui sans représentation directe au parlement. Ce résultat illustre une critique fréquemment formulée à l'encontre du système uninominal majoritaire à un tour : il peut entraîner une distorsion significative entre le pourcentage de voix qu'un parti reçoit et le nombre de sièges qu'il obtient au parlement. Cela peut aboutir à une représentation politique asymétrique et à une sous-représentation des petits partis.

Le scrutin uninominal majoritaire à un tour (ou "first-past-the-post") a tendance à favoriser les grands partis et à marginaliser les plus petits. Voici quelques raisons pour cela :

- Le seuil de victoire est élevé : Pour gagner un siège dans ce système, un candidat doit obtenir plus de voix que tout autre candidat dans sa circonscription. Pour les petits partis, atteindre ce seuil dans une ou plusieurs circonscriptions peut être très difficile.

- La dispersion des voix : Les petits partis, qui ont souvent un soutien réparti uniformément à travers le pays, peuvent obtenir un pourcentage de voix respectable au niveau national, mais ne pas avoir assez de soutien concentré dans des circonscriptions individuelles pour gagner des sièges.

- L'effet de "vote utile" : Les électeurs peuvent être réticents à "gaspiller" leur vote sur un petit parti qu'ils pensent avoir peu de chances de gagner, et peuvent donc choisir de voter pour un grand parti à la place. Cela peut renforcer encore davantage la position des grands partis.

Le "troisième parti", ou tout parti autre que les deux plus grands, peut être désavantagé dans ce système. Même s'ils obtiennent une part importante du vote national, ils peuvent se retrouver avec un nombre de sièges disproportionnellement faible au parlement. C'est l'une des principales critiques de ce type de système électoral : il peut ne pas refléter fidèlement la diversité des préférences politiques de l'électorat dans la composition du parlement.

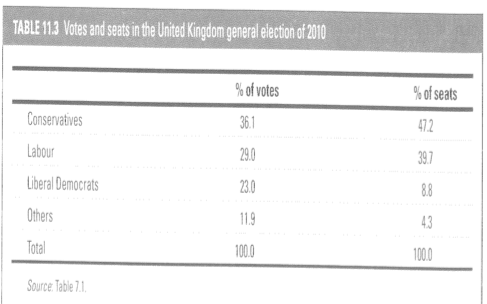

Dans ce système, le candidat avec le plus grand nombre de voix dans chaque circonscription est élu, indépendamment du pourcentage de voix qu'il obtient. En conséquence, un parti qui a un soutien significatif mais dispersé sur l'ensemble du territoire peut se retrouver avec beaucoup moins de sièges que ce que sa part des voix au niveau national suggérerait. Les libéraux démocrates ont obtenu 23% des voix aux élections générales britanniques de 2010, ce qui est un score significatif. Cependant, comme ce soutien était dispersé et que le parti est souvent arrivé en troisième position dans les circonscriptions, il n'a remporté qu'un petit nombre de sièges. Cela soulève des questions de représentativité et d'équité. Malgré le soutien d'un quart des électeurs, les libéraux démocrates ont été sous-représentés au Parlement par rapport aux deux principaux partis, les conservateurs et les travaillistes. C'est une critique fréquente de ce système électoral : il peut ne pas refléter de manière équitable la diversité des préférences politiques des électeurs dans la composition du Parlement.

L'un des phénomènes courants dans les systèmes de scrutin uninominal majoritaire à un tour, comme le "first-past-the-post", est le vote stratégique ou le "vote utile". Face à la perspective que leur candidat ou parti préféré ne gagne pas dans leur circonscription, les électeurs peuvent choisir de voter pour un candidat ou un parti qu'ils estiment avoir une meilleure chance de battre un candidat ou un parti qu'ils apprécient moins. Autrement dit, ils ne votent pas nécessairement pour leur premier choix, mais contre leur dernier choix. Par exemple, si un électeur préfère le Parti A, mais pense que seul le Parti B a une chance de battre le Parti C qu'il n'aime pas, il peut choisir de voter pour le Parti B même s'il préfère le Parti A. Ce phénomène peut biaiser les résultats de l'élection et contribuer à la sous-représentation des petits partis. Il est à noter que le vote stratégique est souvent le produit de l'incertitude et de la complexité de prévoir les résultats électoraux. Il peut conduire à une représentation parlementaire qui ne reflète pas fidèlement les préférences réelles des électeurs.

Scrutin uninominal majoritaire à deux tours[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The two-round first-past-the-post system is an electoral system in which a candidate must obtain an absolute majority of votes to be elected. If no candidate obtains an absolute majority in the first round, a second round of voting is held between the two candidates who obtained the highest number of votes in the first round. The candidate who obtains the highest number of votes in the second round is elected.

The two-round first-past-the-post system offers a degree of flexibility that may enable voters to cast a more honest ballot. In the first round, voters can vote for their preferred candidate without worrying about the strategic consequences. Even if that candidate has little chance of winning, voting for him or her is not a "wasted vote", because there is still a second round. If their preferred candidate does not reach the second round, voters can then choose between the two remaining candidates. At this point, they can choose to vote strategically, by voting for the "lesser evil", or they can choose to abstain if neither of the two candidates suits them. This possibility of "honest voting" in the first round is an advantage of the two-round system over the first-past-the-post system, where voters may feel obliged to vote strategically from the outset. However, this also depends on the specific preferences of voters and the dynamics of the specific election.

This system is used in many countries, including France for presidential and legislative elections.

Advantages :

- Representativeness: It guarantees that the elected candidate is supported by a majority of voters, at least in the second round.

- Possibility of conviction vote in the first round: Voters can vote for the candidate of their choice in the first round, even if they think he or she has little chance of winning, and then vote strategically in the second round if necessary.

- Balance between stability and representativeness: It generally favours the major parties, but also allows candidates from smaller parties to stand and possibly be elected.

Disadvantages :

- Cost: Organising two rounds of voting can be costly and time-consuming.

- Turnout: Turnout may fall during the second round, especially if the result seems to have already been decided.

- Lack of proportionality: Like first-past-the-post, this system can lead to a distortion between the percentage of votes a party receives at national level and the number of seats it obtains in parliament.

Although the two-round first-past-the-post system allows voters to cast a more honest vote in the first round, it does not always guarantee proportional representation in parliament. This is particularly true for parties whose support is scattered across the country rather than concentrated in specific constituencies. The Front National (now Rassemblement National) received significant support at national level in the 2012 French presidential elections, with around 18% of the vote in the first round. However, because this support was scattered and the party often finished third or lower in constituencies in subsequent legislative elections, it struggled to convert this support into seats in the National Assembly. This is one of the drawbacks of majority electoral systems: they can lead to parliamentary representation that does not accurately reflect voter support for the various parties. This can raise questions of representativeness and fairness, especially when the party concerned receives a significant share of the national vote.

The two-round first-past-the-post system can sometimes lead to situations where the candidate with the third highest number of votes in the first round is eliminated, despite significant support. This can happen because the votes are split between several similar candidates. The French presidential election of 2002 is a striking example. In the first round, incumbent President Jacques Chirac and Front National leader Jean-Marie Le Pen came out on top, although neither received a majority of the vote. Socialist candidate Lionel Jospin, who had received almost as many votes as Le Pen, was eliminated because he came third. One of the reasons why Jospin failed to reach the second round was the division of the vote on the left. A number of left-wing candidates ran, and "scattered" the votes of left-wing voters between them. This reduced the total number of votes that Jospin was able to receive, and allowed Le Pen to move into second place with a slight advantage. This came as a big surprise in France and sparked a debate about the potential flaws in the two-round plurality system. It is a reminder that, although this system can often offer a good balance between stability and representativeness, it is not without its problems and can sometimes produce unexpected or controversial results.

In this electoral system, voters rank candidates in order of preference rather than voting for a single candidate. If a candidate receives more than 50% of the first preferences, he or she is elected. If no candidate reaches this threshold, the candidate with the fewest first preferences is eliminated, and his or her votes are redistributed to the remaining candidates according to the second preferences indicated by the voters. This process continues until a candidate obtains over 50% of the votes. This system better accounts for popular support for each candidate and avoids the early elimination of a candidate who could be the second choice of many voters. It can also encourage voters to vote more sincerely, as they can express their true preference without fear that their vote will be "wasted". Alternative voting is used in some countries and elections, such as the Australian general and London mayoral elections.

Instant-runoff voting is a voting method used in single-round elections where voters rank candidates in order of preference. Suppose no candidate obtains more than 50% of the votes at the first count. In that case, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and his or her votes are redistributed according to the second choices indicated on the ballot papers. This process is repeated until a candidate has more than 50% of the votes. However, it is important to note that this system is not used in the two-round first-past-the-post system used in France for legislative and presidential elections. In this system, if no candidate obtains more than 50% of the votes in the first round, the two candidates with the most votes face off in a second round. Voters do not rank their choices by preference, and no vote redistribution exists. In the context of a preferential voting system this could allow a Robert Hawkins supporter to express a second choice for Jude Robinson. If Robert Hawkins is eliminated, that supporter's vote would then be allocated to Jude Robinson. In the two-round majority system, however, the supporter would have the opportunity to choose again between the two remaining candidates in the second round.

Proportional systems[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In a proportional electoral system, the aim is to allocate seats in a way that reflects the percentage of votes each party receives. This system is designed to give fair representation to all groups of voters.

There are several variations of proportional electoral systems, including :

- List proportional representation: In this system, voters vote for a list of candidates proposed by each party. Seats are then allocated to the parties in proportion to the number of votes they receive. It can be a closed list, where the party determines the order of candidates, or an open list, where voters can influence the order of candidates on the list.

- Single Transferable Vote (STV): In this system, used for some elections in Ireland and Australia, voters rank candidates in order of preference. Votes are first allocated to each voter's first choice, then, if a candidate has more votes than necessary to be elected, or if a candidate has the fewest votes and is eliminated, the votes are transferred to the other candidates according to the other preferences expressed.

- Mixed Member Proportional Representation: In this system, which is a combination of the proportional and majority systems, some of the seats are allocated based on a majority vote in individual constituencies, while the other part is allocated based on a proportional vote at national or regional level. This system is used in Germany, New Zealand and Mexico, among others.

In all cases, the idea behind proportional representation is to reduce the "waste" of votes in majority systems and ensure that political minorities are adequately represented.

A multi-mandate or multi-seat proportional representation electoral system is one in which several candidates are elected in each constituency or district. Multi-seat proportional representation is used in many countries, particularly in Europe. Voters generally vote for political parties rather than individual candidates, and parties receive a number of seats proportional to the number of votes they receive. The more seats there are to be filled in a district, the more proportional the result is likely to be. This is because with more seats to be filled, there is a greater chance that a variety of parties or candidates will obtain representation.

For example, if a district elects ten representatives, then a party that receives around 10% of the vote should, in theory, win a seat. But if the same district only chose one representative (as is the case in a first-past-the-post system), then a party receiving 10% of the vote would probably not win that seat, unless it received more votes than any other party. This system allows for better representation of minorities and smaller parties, and can therefore result in a greater diversity of voices and perspectives in the political process. However, it can also make the political system more fragmented and complicate the formation of stable governments.

The most widespread variant of this voting system is the list proportional representation system. In this system, each political party presents a list of candidates equivalent to the number of seats to be filled. After the vote, the seats are distributed according to the number of votes received by each party, following a predefined method.

The proportional list system is the most commonly used form of proportional representation. Here's how it works:

- Creation of candidate lists: Each party draws up a list of candidates. The number of candidates on the list is generally equal to the total number of seats available in the constituency. The order of candidates on the list may be determined by the party itself (closed list) or may be influenced by voters (open list).

- Voting: Voters vote for a party list rather than for an individual candidate.

- Seat allocation: Seats are allocated to parties in proportion to the total number of votes they receive. There are various methods of doing this, such as the d'Hondt method or the Sainte-Laguë method, which use mathematical formulae to distribute seats as proportionally as possible. For example, if a party gets 30% of the vote in a 10-seat constituency, it would get around 3 seats (30% of 10). The candidates occupying the first three places on that party's list would then be elected.

- Distribution strategy: The distribution strategy depends on the type of proportional list system. In a closed list, the order of candidates is set by the party and voters cannot change this order. Seats are allocated in the order of the list until the party has no more seats to allocate. In an open list, voters can influence the order of candidates on the list, and seats are allocated according to the changed order.

This system is designed to ensure fair representation of all political parties in a legislature, based on the support they receive from voters. It tends to favour minority parties and encourage a multi-party political system.

An electoral system can be analysed along several dimensions. These five dimensions are explained below:

- Electoral formula: This is the method used to convert votes into seats. For example, in a majority system, the candidate or party with the most votes wins. In a proportional system, seats are distributed according to the percentage of votes obtained by each party.

- District size: This dimension concerns the number of seats available in each constituency or district. The larger the size of the district, the more proportional the system is likely to be. The size of the district, i.e. the number of seats to be filled in each constituency or district, can influence the proportionality of an electoral system. In Ireland, for example, the Single Transferable Vote (STV) system is used. Each constituency elects between three and five members, allowing proportionality while retaining local representation. In the Netherlands, on the other hand, the system of representation is totally proportional. The country is considered a single electoral district for parliamentary elections, with 150 seats to fill. This means that political parties have the opportunity to be represented in the Tweede Kamer (the lower house of the Dutch parliament) even if they only have a small fraction of the national vote. As a result, Dutch politics tends to be extremely diverse and representative of the different opinions of the population. As a general rule, the more seats there are to be filled in a district, the more proportional the result will be. This allows for better representation of political minorities, but can also lead to political fragmentation and difficulties in forming a stable government.

- Level of electoral system: This is whether the system is national, regional or local. Some countries use different electoral systems at different levels of government. The level of the electoral system refers to the structure in which the election takes place. This can refer to the level of government (local, regional, national), but also to the structure of the electoral system itself. Some electoral system structures have several "levels" of seat distribution. For example, in some mixed or compensatory proportional representation systems, a first set of seats is allocated at district level, usually using a majoritarian or semi-proportional system. Additional seats are then allocated to a "second tier" in order to compensate for proportionality distortions that have arisen at the first tier. This is the case, for example, in Germany, where half the seats in the Bundestag are allocated in single-member constituencies using the first-past-the-post system, while the other half are allocated on the basis of party lists at Land level to ensure overall proportional representation. In some Nordic countries, a proportion of seats is reserved for candidates who were not elected at district level, thus ensuring more proportional representation. These seats, often referred to as compensatory or levelling seats, can help correct distortions produced by distributing seats at district level. The percentage of these seats varies from country to country, but can range from 11% to 20%.

- Representation threshold: This is the minimum percentage of votes a party must obtain to be eligible for seats. This threshold is often used in proportional representation systems to avoid excessive fragmentation of the political system. This threshold is an important feature of many proportional representation systems. It is a minimum percentage of votes that a party must obtain in order to be eligible for seats. These thresholds aim to avoid excessive fragmentation of the political system, which could make it difficult to form stable governments. They also prevent the entry into parliament of extremist parties that have only obtained a very small percentage of the vote. The example of Germany is particularly instructive. Following the problems caused by political fragmentation under the Weimar Republic, post-war Germany introduced a 5% threshold for the allocation of seats in the Bundestag. However, an exception to this threshold exists for parties that win at least three constituency seats. Some countries also use a "bonus seats" system, whereby the party that comes first in an election receives additional seats. This is generally done to facilitate the formation of a stable government and to reward the party that has received the most support from voters. It is important to note that while thresholds and bonus seat systems can help promote political stability, they can also distort proportional representation and exclude certain voices from the political process.

- Ability to choose candidates from within a list: Some PR systems allow voters to choose specific candidates from within a party list. In an open list, voters can influence the order of candidates on the list. In a closed list, the party's order of candidates is fixed. Mixing" allows voters to vote for candidates from different parties. Once the seats have been allocated to each party, it is necessary to determine which specific candidates will occupy those seats. This process varies depending on whether the system uses open lists, closed lists, or allows "panachage". Here's what each term means:

- Open ballot: In this system, voters are able to vote for specific candidates within a party's list. They can also add candidates from other parties. This allows voters to influence the order of candidates on the list, which determines which candidates will be elected if the party wins enough seats.

- Closed lists: In this system, the order of candidates on each party's list is predetermined by the party itself. Voters vote for a party list rather than for individual candidates. The seats the party wins are allocated to the candidates in the order in which they appear on the list.

- Panachage: This method allows voters to vote for candidates from different lists, or even for people who are not candidates. This gives voters maximum flexibility to personalise their vote. Panachage is used in some electoral systems, notably in Switzerland and Luxembourg. These different methods have implications for the degree of control voters have over which specific candidates are elected, and can therefore influence the type of representation the electoral system produces.

Each of these dimensions can have a significant impact on the outcome of an election and on the nature of the political system as a whole.

Analysing the implications of electoral systems[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The choice of electoral system has significant consequences for the nature of a country's political system and can influence a variety of outcomes, including:

- Political representativeness: Proportional electoral systems tend to give a fairer representation of the different political currents that exist within the electorate, whereas majoritarian systems can favour large parties and marginalise small parties and minorities.

- Government stability: Majority systems tend to produce stable governments based on a clear majority. Proportional systems, on the other hand, can lead to the formation of governing coalitions, which can sometimes be unstable if no party succeeds in obtaining a clear majority.

- Accountability and the link between the voter and the elected representative: In first-past-the-post or two-round systems, each MP represents a specific constituency, which can strengthen the link between the voter and his or her representative. In proportional list systems, on the other hand, MPs are elected on party lists, which can weaken the link between the voter and their representative.

- Diversity of representatives: Some electoral systems may encourage greater diversity among elected representatives, for example by favouring the representation of women or minorities. For example, some countries use closed lists with gender parity rules.

- Voting behaviour and political parties: The electoral system can influence the behaviour of voters and political parties. For example, in majoritarian systems, voters may be encouraged to vote strategically to avoid "wasting" their vote on a candidate who has little chance of winning.

There is no "best" universal electoral system that would be optimal for all countries in all contexts. The choice of the appropriate electoral system depends very much on the specific context of a country, its societal values, its history, and the objectives it seeks to achieve through its electoral system.

- Number of votes obtained: Proportional systems are generally considered to be fairer in terms of the representation of votes obtained, as they allocate seats according to the percentage of votes obtained by each party. However, this can lead to fragmentation of the political system and difficulties in forming a stable government.

- Representation of women and minorities: Closed list systems, where the order of candidates is predetermined by the party, can be used to improve the representation of women and minorities. For example, some countries impose quotas or gender parity rules on party lists. However, much also depends on political will and commitment to diversity.

- Effectiveness - Government stability: Majority systems tend to favour the formation of stable governments by giving a premium to the majority. However, they can also lead to under-representation of smaller parties and minorities. Proportional systems, on the other hand, can lead to the formation of coalitions, which can sometimes be unstable.

- Performance (economic, social indicators, etc.): It is difficult to establish a direct and universal link between the electoral system and economic or social performance. This depends on many other factors, such as the quality of leadership, the policies in place, the overall economic context, and many others.

It is therefore important to weigh up these different factors and adapt the electoral system to the specific political, social and cultural context of each country.

Does the proportional system ensure greater representativeness? The proportional system is often considered to offer better representativeness in terms of the correspondence between the number of votes obtained by each party and the number of seats it receives in parliament or the assembly. In a proportional system, the number of seats a party obtains is generally proportional to the percentage of votes it received. In other words, if a party gets 30% of the votes, it should also get around 30% of the seats. This can give a fairer representation of the different political tendencies within the population. On the other hand, in a majority system, a party can win a majority of seats with less than 50% of the vote. For example, if a party wins 40% of the votes in each constituency, it can win all the seats even if it does not have a majority of the votes nationwide.

Majority systems such as the first-past-the-post system used in the UK, or the two-round first-past-the-post system used in France, can sometimes produce results that do not perfectly reflect the distribution of votes at national level. In a majoritarian system, it is possible for a party that obtains the majority of votes in a large number of constituencies, but not necessarily the majority of votes at national level, to win a large majority of seats. This can lead to a distortion between the percentage of votes obtained by a party and the percentage of seats it receives. For example, in the UK at the 2015 general election, the Conservative Party won 51% of the seats with just 37% of the vote. At the same time, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) received 13% of the vote but only won one seat (0.2% of the total).

Even among non-proportional (or majority) systems, there is a wide variety of methods and rules that can affect the degree of representativeness. The size of the district, i.e. the number of seats to be filled in each constituency, can have a significant impact. In systems with large constituencies, such as the Netherlands, where the whole country is treated as a single district for parliamentary elections, the result tends to be more proportional as smaller parties have a better chance of winning a seat. However, other factors can also play a role. For example, the existence of an electoral threshold, as in Czechoslovakia, can introduce a degree of non-representativeness. An electoral threshold is a rule which stipulates that a party must obtain a certain percentage of the vote (for example, 5%) in order to be eligible to win seats. This rule can prevent small parties from obtaining representation, even if they have managed to obtain a significant proportion of the vote.

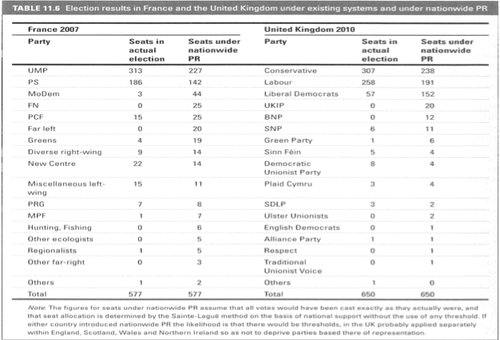

This table illustrates a hypothetical simulation of the electoral results for the 2007 and 2010 elections in France and the United Kingdom, if an alternative system had replaced the majority electoral system in place. The table shows a decrease in the share of seats held by the major parties and an increase in the share held by the smaller parties. A similar trend can be observed in England, where such a change in the electoral system could potentially alter the composition of the government coalition resulting from the elections.

This is a major potential consequence of the switch from a majoritarian to a proportional electoral system. In a proportional system, smaller parties generally have a much greater chance of winning seats, which could reduce the share of seats held by the larger parties. In a plurality system such as those used in France and the UK, the parties that win a plurality of votes in each constituency receive all the seats in that constituency, which tends to favour the larger and more established parties. In a proportional system, on the other hand, seats are allocated according to each party's share of the vote, which generally gives smaller parties a better chance of representation. This means that if France or the UK were to move to a proportional system, it could lead to an increase in the number of parties represented in parliament and greater fragmentation of the political landscape. It could also change the possible government coalitions, as the large parties might need to ally themselves with more small parties to form a majority.

The representativeness of women in electoral systems[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Women's representation in politics is an important issue in many countries. Within an electoral system, several factors can influence the degree of representation of women.

- The type of electoral system: In proportional systems, particularly those using closed lists, parties often have the option (and sometimes the obligation) of alternating men and women on their candidate lists, which can increase women's representation. On the other hand, in a first-past-the-post or two-round system, candidates are often chosen individually for each constituency, which can limit opportunities for women.

- Gender quotas: Some countries have introduced mandatory quotas to guarantee a certain percentage of women among candidates or elected representatives. These quotas can be particularly effective in closed list systems.

- Political and social culture: Even in the absence of quotas, a country's political and social culture can influence the representation of women. For example, parties may choose to put forward more women candidates in response to voter demand or to promote gender equality.

- Institutional support: Support from the state and political institutions can also play a role. For example, training and mentoring programmes can help prepare more women to stand for election.

While these factors can increase women's representation, they do not necessarily guarantee gender equality in politics. For example, elected women must also have the opportunity to hold positions of power and participate fully in decision-making. Furthermore, women's representation must not be limited to parliament or the assembly, but must extend to all levels of government and all spheres of political life.

Several studies have shown that proportional electoral systems tend to favour a better representation of women than majority systems. There are several reasons for this trend. Firstly, in proportional systems, parties often have the opportunity (and sometimes the obligation) to present candidate lists with a balanced proportion of women and men. In particular, in closed list systems, parties may be required to present 'zebra' lists, where men and women alternate. Secondly, proportional systems can encourage diversity by providing more opportunities for smaller parties. As women are sometimes more present in minority or new parties, this can increase their chances of being elected. Finally, in a proportional system, parties may be more inclined to put forward women candidates in response to voter demand for gender balance.

In a proportional electoral system, especially a list system, having several candidates to choose from the same list may encourage parties to diversify their candidates in terms of gender. In such a system, voters have the option of voting for a list rather than for an individual candidate. Consequently, a political party that presents an all-male list of candidates could risk losing the support of a section of the electorate that values gender diversity. Thus, presenting a mixed list may be perceived as more inclusive and democratic, which may attract a wider electorate.

Furthermore, in a single-member constituency system, the party must choose a single candidate to represent each constituency. This can perpetuate gender stereotypes and limit opportunities for women candidates if voters or parties are biased in favour of male candidates. That said, while these factors may help to explain why proportional systems tend to favour better representation of women, they are only part of the explanation. Other factors, such as the country's political culture, party policies, gender quotas and institutional support for women's participation, also play a crucial role.

Proposing lists of candidates that are diverse in terms of gender, ethnic origin, age, etc., can be beneficial for a political party in a proportional electoral system. On the one hand, it can help to attract a wider and more diverse electorate, as different groups within the electorate may feel more represented and therefore more inclined to vote for that party. On the other hand, the diversity of candidates can help to improve the quality of decision-making within the party and within elected bodies, as different perspectives and experiences can be taken into account. In addition, presenting diverse lists can be seen as a sign of openness and modernity on the part of the party, which can improve its image with the electorate. It can also contribute to the legitimacy of the political system as a whole, by giving the impression that all parts of society are represented.

Influence of electoral systems on the number of parties[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Maurice Duverger, a French political scientist, is well known for having formulated "Duverger's law" in the 1950s. This law postulates a correlation between a country's electoral system and the structure of its party system. Specifically, Duverger argued that electoral systems based on single or two-round plurality (as in the UK or France) tend to favour a two-party system, while proportional electoral systems (as in the Netherlands or Belgium) tend to lead to a multi-party system.

The reason for this is that, in a majority system, minority parties have little chance of winning seats, which encourages voters to vote strategically for one of the two main parties rather than 'wasting' their vote on a small party. As a result, over time, the smaller parties are marginalised and a two-party system emerges. In a proportional system, on the other hand, even small parties have a reasonable chance of winning seats, which encourages party diversity.

Maurice Duverger formulated two major laws concerning the relationship between the electoral system and the number of political parties in a country. These two laws, often referred to as Duverger's laws, are as follows:

- The first law, often referred to as the "mechanical law", states that the first-past-the-post system favours a two-party political system. The reasoning is that in this system, small parties with popular support scattered across the country have little chance of winning seats, because they have to be the first choice in a given constituency to win. This discourages voters from voting for these small parties, as they don't want to "waste" their vote. Instead, they are encouraged to vote for one of the two big parties, reinforcing their dominance.

- The second law, often called the "psychological law", holds that proportional representation systems favour a multi-party system. In this system, even parties with minority support spread across the country have a chance of winning seats, provided they reach a certain percentage threshold of votes. This encourages party diversity and the representation of a variety of interests.

The "effective number of parties", or the "effective size of the party system" is an indicator that was proposed by political economist Markku Laakso and political analyst Rein Taagepera in the 1970s. The concept behind the effective number of parties is that not all parties are equal in terms of importance. Some parties may have many more seats in parliament or votes in an election than others. Therefore, simply counting the total number of parties may not give an accurate picture of the complexity and diversity of the party system.

The formula for calculating the effective number of parties is :

Effective number of parties = 1 / (Sum of the squares of the proportions of seats (or votes) of each party)

For example, suppose there are three parties in a country with the following proportions of seats in parliament: 0.5 for party A, 0.3 for party B, and 0.2 for party C. The effective number of parties would then be :

Effective number of parties = 1 / (0.5^2 + 0.3^2 + 0.2^2) = 2.44

This means that in terms of seat distribution, this party system is equivalent to a system with around two to three parties of equal size.

Impact on the type of government: coalitions vs. single-party governments[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The nature of a country's electoral system has a significant influence on the composition of its government.

- Coalition governments in proportional systems: In proportional representation systems, such as those in force in most European countries, governments are often formed by multi-party coalitions. This is because in these systems it is more difficult for a single party to obtain an absolute majority of seats. The diversity of parties obtaining seats in parliament often means that negotiations and compromises are needed to form a government.

- Single-party governments in majoritarian systems: In majoritarian electoral systems, such as those of the United Kingdom or the United States, it is more common to have single-party governments. This is because the majority system favours the large parties and makes it difficult for smaller parties to gain access to Parliament. As a result, it is more likely that a single party will win a majority of seats, making it possible to form a government without the need for coalitions.

These characteristics have implications for governance. In coalition systems, decision-making can be more complex and slower, due to the compromises required between the different parties in the coalition. However, this can also lead to decisions that are more consensual and representative of the various interests in society. On the other hand, a one-party government may be able to make decisions more quickly, but these decisions may not reflect as much diversity of opinion and interest.

Advantages and disadvantages of different electoral systems[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

There is an ongoing debate among political scientists and electoral system specialists about the merits and disadvantages of proportional representation and plurality systems.

Criticisms of proportional representation:

- Governmental instability: Coalition governments, which are more common in proportional systems, can be unstable and prone to breakdown. This can lead to short-lived governments and political instability.

- Difficulty of reform: In a coalition government, each party has its own priorities and policy positions, which can make it difficult to implement meaningful policy reforms. The negotiation process required to reach agreement between the parties can be long and arduous.

- Lack of accountability: It can be difficult for voters to hold a specific party accountable for the actions of the government, as no single action is entirely the responsibility of a single party.

Advantages of majority system:

- Clarity of responsibility: In a single-party government, it is clear who is responsible for the government's actions. This can improve political accountability.

- Government stability: Single-party governments are generally more stable than coalition governments because they do not depend on several parties for their survival.

- Capacity for reform: A party with an absolute majority is generally in a better position to implement major policy reforms, as it does not need to negotiate with other parties to gain their support.

In proportional representation systems, implementing reforms can be a challenge because of the need to achieve consensus among several parties. Here are some points to explain this phenomenon:

- Coordination between parties: In a coalition government, decisions have to be coordinated and negotiated between several parties. This can make the decision-making process slower and more complex, as each party has its own interests and priorities.

- Blocking reforms: In a coalition, a minority party can potentially block a reform important to the other parties. This dynamic can hamper the government's ability to reform.

- Coalition instability: Coalitions can be unstable and prone to breaking up, particularly when dealing with controversial issues. This can lead to short-lived government and political instability, reducing the capacity for reform.

- Capacity to respond: The need to negotiate and coordinate across party lines can also make the government less able to respond quickly to economic and social challenges.

Studies have shown links between electoral systems and economic policies. For example, some work has suggested that countries with proportional representation systems may tend to have higher budget deficits and levels of public debt.

There are several possible reasons for this:

- Political compromises: In proportional representation systems, multi-party coalitions often form governments. To maintain the coalition's stability, parties may have to make compromises, including increased public spending to satisfy different constituencies.

- Political instability: The potential instability of coalition governments may make it more difficult to adopt austerity or fiscal consolidation measures, as these may be politically unpopular and jeopardise the coalition.

- Representativeness: Proportional representation systems allow for better representation of different groups in society, which can translate into greater demand for public spending to meet the needs of these different groups.