The era of the superpowers: 1918 - 1989

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Ludovic Tournès[1][2][3] |

| Cours | Introduction to the history of international relations |

Lectures

- Perspectives on the studies, issues and problems of international history

- Europe at the centre of the world: from the end of the 19th century to 1918

- The era of the superpowers: 1918 - 1989

- A multipolar world: 1989 - 2011

- The International System in Historical Context: Perspectives and Interpretations

- The beginnings of the contemporary international system: 1870 - 1939

- World War II and the remaking of the world order: 1939 - 1947

- The international system in the test of bipolarisation: 1947 - 1989

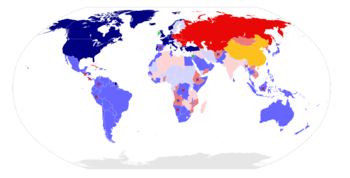

- The post-Cold War system: 1989 - 2012

It is quite possible to consider that the era of the superpowers began in 1918 with the end of the First World War, which created an international context conducive to the emergence of two great powers: the United States and the Soviet Union. The period following the end of the First World War was marked by geopolitical and economic tensions that led to the rise of these two countries. However, it is true that the period from 1945 to 1989 is generally regarded as the height of the superpower era, due to the intense rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union and the arms race that marked this period. This period is also characterised by important events such as the Korean War, the Cuban crisis, the Vietnam War and the space race, which helped shape the global geopolitics of the time.

The period following the end of the First World War was marked by the gradual decline of Europe as a global power centre and the emergence of new powers such as the United States and the Soviet Union. The First World War considerably weakened European countries, which suffered enormous human and material losses. The war debts also had a negative impact on the European economy, which had difficulty in recovering after the conflict. In addition, the rise of nationalist movements and authoritarian regimes in Europe led to political and social tensions that also contributed to the region's decline.

At the same time, the United States became a major economic power thanks to its flourishing industry and its role in the First World War. The Soviet Union also became a major power after the 1917 revolution, which led to the formation of a socialist state. Over the decades, the United States and the Soviet Union have consolidated their economic, political and military power at the expense of Europe and other parts of the world. The rivalry between these two superpowers has influenced global geopolitics and shaped the history of the 20th century.

The war record of the First World War

The First World War had a huge impact on the history of the 20th century. It caused enormous human and material losses, destroying large parts of Europe and other parts of the world. Some 8.5 million soldiers and 13 million civilians lost their lives during the war. Millions more were injured or suffered from disease, starvation and deprivation. The war also resulted in massive population displacement, forced displacement and refugees. Economically, the war had a devastating impact on Europe, which suffered considerable losses in terms of production and labour. European countries accumulated huge war debts that weighed on their economies for decades. The war also had profound political and social consequences. It led to the fall of several empires, including the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires. It also contributed to the rise of communism and fascism in Europe, which influenced the history of the 20th century.

Great powers after the war

France

France suffered considerable human, economic and material losses during the First World War. The country lost about 1.5 million soldiers, a very high percentage of its total population. The north-eastern regions of France were particularly hard hit, with entire towns and villages destroyed.

In addition to the loss of life, the war also caused significant economic damage. Mining and industrial facilities were devastated, resulting in loss of production and increased unemployment. In addition, the cost of the war left the country with huge debts that weighed on the French economy for decades.

The consequences of the war also had an important social and cultural impact in France. The war led to profound changes in French society, including an increase in the participation of women in economic and political life and a questioning of traditional values.

Despite these challenges, France managed to rebuild itself after the war and to become an important economic and cultural power in Europe again.

Germany

Germany suffered considerable loss of life during the First World War, with between 1.7 and 2 million dead. The country also suffered significant economic damage as a result of the war and the reparations that were imposed by the Treaty of Versailles.

The treaty required Germany to pay heavy financial reparations, reduce its army and fleet, and cede territory to its neighbours. This humiliation was felt by many German citizens, who regarded the treaty as unfair and humiliating.

In addition, Germany was hit by a Bolshevik revolutionary wave, which was inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917. German socialists took power in November 1918, but their government soon faced political and social unrest.

However, unlike France, the fighting of the war was mainly outside Germany's borders, allowing the country to emerge relatively unscathed. This also allowed Germany to rebuild more quickly than some other European countries after the war, although this was interrupted by the Great Depression of the 1930s and the rise of Nazism.

Austria-Hungary

The First World War had a major impact on the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which collapsed at the end of the war. The empire was a multinational state that had been established in 1867 and had played a key role in Central Europe for most of the 19th century.

However, the war highlighted the internal divisions of the empire, particularly between the different nationalities that made up the empire. In addition, the war drained the empire's resources and resulted in considerable loss of life.

In October 1918, the empire collapsed and split into several independent states, including Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. This fragmentation had important consequences for the region, as it created new states with often disputed borders and mixed populations.

The break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire also had international repercussions, as it contributed to the rise of German power in Central Europe. In addition, the political and economic consequences of the fragmentation of the empire had an impact on the stability of the region in the years following the end of the war.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire also suffered the consequences of the First World War, with a collapse that was precipitated by the war.

The Ottoman Empire was a multinational empire that had been established in the early 14th century and reached its peak in the 16th century. However, by the 19th century, the empire had begun to lose influence, due to the rise of Europe and the disintegration of the empire's internal political unity.

The war further aggravated the situation of the Ottoman Empire. The empire initially joined the central powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary) but suffered several major defeats against British, French and Australian forces in the Middle East region. These defeats resulted in significant territorial losses for the Ottoman Empire.

After the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire disintegrated and split into several independent states, including Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Palestine and Jordan. This fragmentation had important implications for the region, as it created new states with often contested borders and mixed populations.

In addition, the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire had important geopolitical implications for Europe and the Middle East in the years following the end of the war. Regional conflicts and political tensions persisted in the region, largely due to the complexity of territorial and ethnic issues that emerged after the collapse of the empire.

Russia

Russia suffered heavy losses in the First World War and was plagued by major economic, political and social problems. In 1917, a revolution broke out in Russia, led by the Bolsheviks led by Lenin. The Russian government was overthrown and replaced by a communist regime.

The new government quickly took the decision to withdraw Russia from the war, signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany and its allies in 1918. This treaty allowed Russia to withdraw from the war, but at the cost of losing large areas of territory, notably in Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic States.

Russia's exit from the war had important consequences for the other powers involved in the conflict. The Allies lost an important ally on the Eastern Front and faced additional pressures on the Western Fronts. However, the entry of the United States into the war also provided additional support to the Allies, in terms of troops, equipment and funding.

Domestically, the revolution in Russia brought about a profound change in Russia's political, social and economic landscape. The new communist government nationalised land and industries, and launched radical reforms in all areas of life. This led to a period of chaos and violence, as well as significant economic losses for Russia.

Britain

Great Britain emerged from the First World War seemingly a little better off than France and Germany, as its territory was not directly affected by the fighting. However, it suffered heavy human and economic losses during the war.

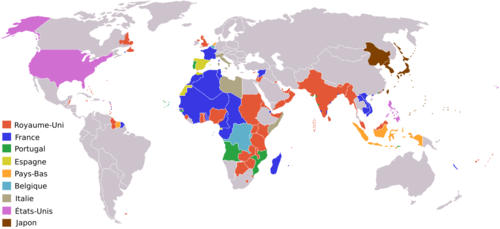

By contrast, Great Britain managed to expand its colonial empire during the war. It conquered the German colonies in Africa and the Pacific, and also obtained new territories in the Arabian Peninsula at the expense of the Ottoman Empire. This territorial expansion strengthened the British Empire and consolidated its status as a major world power.

However, Britain also faced significant challenges in the post-war period, including a weakened economy, high debt and social and political unrest, particularly with the rise of the labour and independence movements in Ireland.

Europe

The First World War caused immense loss of life in Europe, with around 10 million deaths, mostly men. This figure does not take into account indirect deaths, such as those caused by famine and disease, as well as civilian deaths caused by conflict.

These casualties had a dramatic impact on the demography of Europe, resulting in a significant population decline in some regions. Losses were particularly high in countries such as France, Germany, Russia and the UK.

The phenomenon of the 'hollow classes' describes a demographic consequence of the war, which saw the disappearance of a large part of the male generation of childbearing age. This led to a decline in the birth rate in the years following the war, with significant economic and social consequences.

In geopolitical terms, the First World War caused major upheavals in Europe. The peace treaties that ended the war redrawn the borders of many countries, creating new states or modifying existing ones. This period also saw the emergence of new powers, notably the United States and the Soviet Union, which began to play a greater role on the world stage.

The First World War had a profound effect on European societies, leading to an unprecedented moral and cultural crisis. The horrors of war led to a questioning of the idea of progress and faith in reason and science, as well as a questioning of the authority of traditional elites and institutions.

This crisis of civilisation also gave rise to new artistic and intellectual currents, such as Dadaism, Surrealism and Existentialism, which sought to express the anguish and disillusionment of the post-war period. It also helped to fuel far-right political movements, which sought to propose authoritarian solutions to the crisis of civilisation

The First World War led to profound geopolitical upheavals in Europe and around the world. The central empires were dismantled, the map of Europe was redrawn, new states emerged and new alliances were formed. The former European powers lost their global dominance to the USA and the USSR, which became the two post-war superpowers.

Economically, the war led to rampant inflation, massive public debt, falling output and rising unemployment. European states faced major financial difficulties in rebuilding their economies and infrastructures devastated by the war.

Finally, in human terms, the war left deep scars on society. Millions of people were killed or wounded, and many families were destroyed by the loss of loved ones. Survivors have had to cope with psychological and physical trauma, and have struggled to find their place in a rapidly changing society.

The Peace Conference

The Paris Peace Conference took place after the end of the First World War, in January 1919. It was convened to settle peace issues between the victors and the defeated of the war. The main players at the conference were the Allied countries that had won the war, namely the United States, France, Britain, Italy and Japan. However, it is important to note that the conference was also open to the participation of defeated countries, such as Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. These countries were excluded from certain discussions and did not have the same decision-making power as the victorious powers.

During the conference, the main decisions were taken by the 'Big Four', namely the United States, France, Great Britain and Italy. Japan, although considered a great power, did not play as important a role as the other four.

The United States played an important role in the Paris Peace Conference and President Woodrow Wilson played a key role in formulating the agenda of the conference.

Wilson's Fourteen Points

Wilson presented his 'Fourteen Points' to the US Congress in January 1918, in which he proposed a programme for securing international peace and stability after the end of World War I.[4] The points included proposals for a reduction in armaments, self-determination of peoples, free movement of ships in peacetime, the creation of an international organisation to prevent future conflicts, and other measures to strengthen international cooperation.

These points were widely regarded as ambitious and innovative, and helped to make Wilson a leading figure in the peace conference discussions. However, not all of the points were adopted in the final conference agreements and some of Wilson's proposals were rejected by other conference participants. Despite this, the presentation of the Fourteen Points had a significant impact on international diplomacy and strengthened the position of the United States as a leader in international affairs. It also contributed to the emergence of a new world order after the end of the First World War.

Wilson's Fourteen Points addressed both the immediate issues associated with the end of the First World War and the wider problems that contributed to the war. The points sought to establish a fairer and more stable international order, and stressed the importance of international cooperation in achieving this. The United States sought to establish itself as a major player in the Peace Conference and in international diplomacy more broadly. This position was largely due to the United States' relative isolation from the European conflicts, which left the country relatively unscathed by the destruction and loss of life of the war. This allowed the US to adopt a position of power and morality, which was reinforced by the presentation of Wilson's Fourteen Points. However, this position was not widely accepted by the other participants in the conference, particularly France and the United Kingdom, who had suffered considerable human and material losses during the war and were primarily seeking to protect their national interests. Despite this, the United States played an important role in the Paris Peace Conference and contributed to the establishment of a new world order after the end of the First World War.

The Fourteen Points fell into three main categories:

1) Points aimed at establishing transparency and justice in international relations, including:

- The abolition of secret diplomacy: the end of secret diplomacy was one of the main points of Wilson's Fourteen Points. The European system of states was based on a balance of power, with each state seeking to maintain its influence and position by concluding secret alliances and agreements with other states. This often resulted in opacity in international relations and a lack of trust between states. Wilson therefore advocated an end to secret diplomacy in order to clarify international relations and make them more fluid. Instead, he proposed that states should conduct open and transparent negotiations, in order to build relationships based on trust and avoid misunderstandings and future conflicts. This proposal was part of an in-depth reform of the international system of the time, which had shown its limitations during the First World War.

- Freedom of the seas: Freedom of navigation on the seas was also one of the key points of Wilson's Fourteen Points. He advocated absolute freedom of navigation on the seas, both in time of war and peace, for all states without exception. This meant that all ships should be allowed to sail the oceans freely without being attacked or held back by blockades or restrictions imposed by other states. This freedom of navigation was seen as a universal and inalienable right, which should be protected by international law. Freedom of navigation went hand in hand with the removal of economic barriers between nations, another point in Wilson's Fourteen Points. Indeed, without barriers to the movement of goods and services, international trade could have developed more freely and fairly, thus contributing to wider and more sustainable economic prosperity.

- The removal of economic barriers between nations: The lowering of tariff barriers was also an important point in Wilson's Fourteen Points, which aimed to promote trade between nations and facilitate international economic cooperation. However, this proposal was debated and controversial, as some states feared losing their economic independence and their ability to protect their own national industry. In addition, the implementation of the lowering of customs barriers could favour the economic interests of the more powerful countries, to the detriment of the weaker ones.

- The assurance of national sovereignty and political independence was one of the key points of Wilson's Fourteen Points. It was about guaranteeing each state its full sovereignty and political independence, free from foreign interference or domination. Within this framework, Wilson advocated the abolition of annexations of territory and forced transfers of sovereignty, and respect for the rights of national minorities. He also called for the establishment of mechanisms for the peaceful resolution of international conflicts in order to prevent wars and infringements of national sovereignty. The aim of this proposal was to create a fairer and more equitable international order, based on respect for the sovereign rights of each state, and to put an end to the imperialist and colonialist practices that had prevailed in international relations until then. This point has since been widely taken up and defended by the international community, notably in the United Nations Charter.

2) The points aimed at reorganising Europe after the war, notably :

- Withdrawal of German military forces from occupied territories: The withdrawal of German military forces from occupied territories was also an important point in Wilson's Fourteen Points. The aim was to end the German occupation of many territories in Europe, including Belgium, France and other countries, and to restore the independence of these states. The return of Alsace-Lorraine to France was one of the key points of Wilson's Fourteen Points. Alsace-Lorraine was a region of France that had been annexed by Germany in 1871, following the Franco-German War. During the First World War, the region became a point of contention between France and Germany, with violent clashes taking place in the area. As part of the Fourteen Points, Wilson sought to resolve this issue by calling for the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France. This decision was welcomed by the French and helped to strengthen Wilson's position as an international leader. Wilson also called for the return of annexed or illegally occupied territories, as well as the evacuation of German military forces from all German-controlled areas. He thus sought to restore an international order based on respect for state sovereignty and territorial integrity. This proposal was widely supported by the Allies during the First World War, and was incorporated into the peace agreements that followed the war, notably the Treaty of Versailles. However, the implementation of these provisions has been difficult and controversial, particularly with regard to the war reparations demanded from Germany and the consequences of the war on national borders and minorities in Europe.

- The reduction of national frontiers in Europe: The reduction of national frontiers in Europe was not a specific point in Wilson's Fourteen Points, but rather an indirect consequence of his proposal to ensure national sovereignty and political independence of each state. Indeed, Wilson advocated the recognition of the full sovereignty of each state, as well as respect for the rights of national minorities, in order to prevent conflicts and tensions between states. This proposal therefore implied some form of recognition of existing national borders and a guarantee of their inviolability. However, the question of the reduction of national borders in Europe arose several times during the 20th century, notably after the First World War, with the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, and after the Second World War, with the creation of new states and the redefinition of borders. The reduction of national borders is therefore a complex issue, which can be a source of conflict and tension between states and national communities, and which often requires a careful and balanced approach, taking into account the aspirations and interests of the different parties involved.

- Ensuring the sovereignty and autonomy of oppressed peoples: The assurance of the sovereignty and autonomy of oppressed peoples was an important point in Wilson's Fourteen Points. Wilson considered that lasting peace could only be achieved if the rights of oppressed peoples were respected, and that these peoples should be allowed to decide their own fate. This proposal therefore implied the recognition of the autonomy and sovereignty of many peoples who were then under foreign domination, such as the peoples of Central and Eastern Europe under Austro-Hungarian rule, the peoples of the Balkans under Ottoman domination, and the African and Asian colonies under European rule. Wilson also called for the creation of an international organisation to protect the rights of oppressed peoples and to settle international disputes, the League of Nations, which was established in 1920. Although the ideals of Wilson's Fourteen Points were widely welcomed, their implementation was difficult and often limited by the interests of the great powers, as well as by divisions and rivalries among the oppressed peoples themselves. However, the recognition of the importance of the sovereignty and autonomy of oppressed peoples was an important element in the decolonisation movement and the struggle for minority rights that followed the First World War.

3) Points aimed at establishing an international organisation for the peaceful resolution of conflicts, including :

- The establishment of an international organisation to secure peace: The establishment of an international organisation to secure peace was one of the most important points in Wilson's Fourteen Points. Wilson considered that war was often caused by the lack of mechanisms for settling disputes between nations, and that the creation of an international organisation capable of settling international disputes was essential to prevent further wars. This proposal led to the creation of the League of Nations (League) in 1920, which aimed to promote international cooperation and prevent conflict between nations. The League was composed of members representing all the major powers of the day and had a mandate to monitor international relations, settle disputes between member states and impose sanctions against states that did not abide by international rules. Although the League failed to prevent the rise of nationalism and tensions that led to World War II, it laid the foundation for the United Nations (UN), which was created in 1945 to replace the League after the war ended.

- The promotion of international cooperation in economic, social and cultural affairs: The promotion of international cooperation in economic, social and cultural affairs is indeed one of the key points of the Wilson Fourteen Points. Specifically, the fourteenth point stresses the importance of creating an international organisation to regulate world trade and promote economic cooperation between nations. Wilson believed that international economic cooperation was essential to ensure lasting peace and global prosperity. Wilson's fourteenth point stated, "A general association of nations should be formed under specific engagements to secure reciprocity of commercial privileges and reduction of national armaments." This point called for the creation of an international organisation to regulate world trade and to encourage economic cooperation between nations. This organisation should ensure that nations were treated fairly and that there were no unfair trade barriers.

- The resolution of international disputes by peaceful rather than military means: The resolution of international disputes by peaceful rather than military means is another key point in Wilson's Fourteen Points. This meant that nations should work together to find peaceful solutions to conflicts and avoid the use of military force. As part of the Fourteen Points, Wilson also called for the creation of an international organisation to guarantee world peace and security, as well as the reduction of national military armaments. The overall aim of these points was to end international war and conflict, and to build a lasting peace between nations.

The Fourteen Points had an important influence on the end of the First World War and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles negotiations. Although some of the points were included in the Treaty of Versailles, most were not implemented, leading to future tensions and conflicts.

After the end of the First World War, US President Woodrow Wilson was a strong supporter of the creation of an international organisation to maintain peace and security in the world. This organisation, called the League of Nations, was founded in 1919 as part of the Treaty of Versailles. Although the creation of the League of Nations was considered an important historical moment in the history of international relations, it was eventually criticised for being ineffective in preventing the Second World War. Wilson was criticised for being naïve and idealistic in his vision of the League of Nations and for overestimating the willingness and ability of nations to cooperate to keep the peace. In particular, Wilson was criticised for being overly optimistic about the League of Nations' ability to resolve international conflicts and for not including binding clauses in the Treaty of Versailles to ensure the implementation of its principles. Ultimately, the League of Nations was dissolved in 1946 and replaced by the United Nations, which was created with stronger structures to ensure more effective international cooperation. However, some historians argue that Wilson was a visionary who laid the foundations for international cooperation and global governance, although he has been criticised for being naive in implementing his ideas.

The Fourteen Points, presented by President Wilson in January 1918, represented a radical new vision of international relations. They were designed to promote peace and stability in Europe after the First World War by offering an alternative to the traditional balance of power that had prevailed before the war. The Fourteen Points included ideas such as the reduction of armaments, the opening up of international markets, the right of self-determination for peoples, the creation of an international organisation to settle conflicts and the guarantee of the security of national borders. This approach represented a significant shift from the traditional balance of power, which advocated alliances between the great powers to maintain peace. Although the Fourteen Points were presented as an idealistic and humanitarian vision, some argued that their real purpose was to serve the economic and political interests of the United States by promoting an international order based on democracy and free trade. Indeed, the opening of international markets was particularly important to US economic interests, which sought to increase their influence and dominance over world trade.

The Treaties

A series of treaties were signed from June 1919 to end the First World War and establish a new world order. The most important treaties are the following:

- The Treaty of Versailles: signed on 28 June 1919 between Germany and the Allies, this treaty established the conditions for peace after the First World War. It imposed economic and territorial sanctions on Germany, which had to cede territory, pay reparations and acknowledge its responsibility for the outbreak of the war.

- The Treaty of St. Germain: signed on 10 September 1919 between the Allies and Austria-Hungary, this treaty ended the Austro-Hungarian Empire and established new independent states in Central Europe.

- The Treaty of Trianon: signed on 4 June 1920 between the Allies and Hungary, this treaty redrawn the map of Central and Eastern Europe by recognising the independence of Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Romania.

- The Treaty of Neuilly: signed on 27 November 1919 between the Allies and Bulgaria, this treaty ended Bulgaria's participation in the First World War and established economic and territorial sanctions.

- The Treaty of Sèvres: signed on 10 August 1920 between the Allies and the Ottoman Empire, this treaty ended the Ottoman Empire's participation in the First World War and established the conditions for the creation of new independent states in Asia and Africa.

These treaties redrawn the political map of Europe and created a new world order that was largely influenced by the ideals of Wilson's Fourteen Points. However, they also generated criticism and tensions that contributed to the rise of nationalism and the build-up to the Second World War.

The Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was an international agreement signed on 28 June 1919, at the end of the First World War, between the Allies and Germany. It is considered one of the most important treaties of the 20th century and had a lasting impact on world history. The treaty established the conditions for peace after the war and imposed heavy economic and territorial reparations on Germany, which was considered responsible for the conflict. Germany had to accept the loss of its colonies, some of its regions, its war fleet and its sovereignty over the Rhineland. The country also had to pay substantial reparations to the countries that had suffered from the war, which led to a major economic and political crisis in Germany in the 1920s. The Treaty of Versailles also established the League of Nations, an international organisation aimed at maintaining peace and security in the world. However, the United States did not ratify the treaty and therefore did not join the League of Nations, limiting its effectiveness. The Treaty of Versailles has been criticised for its harshness towards Germany, which was widely seen as unfair and humiliating. Some historians have also argued that the terms of the treaty created the conditions for the rise of Nazism in Germany and the Second World War. Ultimately, the Treaty of Versailles remains an important subject of debate and reflection in the history of international diplomacy.

The German question and territorial issues were fundamental points in the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the First World War. The German question refers to Germany's responsibility for the outbreak of the war. The Treaty of Versailles declared Germany guilty of the war and imposed heavy economic and territorial sanctions on the country. Germany had to acknowledge the guilt of the war, pay reparations and cede territory to France, Belgium, Poland, Denmark and Czechoslovakia. The treaty also limited the size of the German army and prohibited the manufacture of weapons. Territorial issues arose after the First World War due to the disintegration of several European empires. New states were created in Central and Eastern Europe, including Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Poland, to which Germany had to cede territory. The Treaty of Versailles also created the British Mandate over Palestine and the French Mandate over Syria and Lebanon, laying the foundations for the current tensions in the Middle East. Both of these had important consequences for the history of the 20th century, including contributing to the rise of nationalism and fascism in Germany and the build-up to the Second World War. The conditions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles also influenced the international diplomacy of the interwar period, which sought to avoid further conflict while maintaining political stability in Europe.

German responsibility

The Treaty of Versailles officially recognised Germany as being responsible for the outbreak of the First World War. Article 231 of the treaty, also known as the guilt clause, stated that Germany and its allies had caused all the damage and losses suffered by the Allies during the war. This clause had major consequences for Germany, including the need to pay massive war reparations to the victim countries, as well as the loss of territories and colonies. However, this attribution of responsibility is still the subject of debate among historians. Some argue that responsibility for the war should be shared more widely between the various European powers, while others believe that Germany was primarily responsible because of its expansionist ambitions and aggressive diplomacy.

The Treaty of Versailles imposed several sanctions on Germany in response to its alleged responsibility for the outbreak of the First World War. Some of these sanctions include:

- Disarmament: Germany was forced to drastically reduce the size of its army and limit the number of its warships. It was also forbidden to possess an air force and to produce weapons of war.

- Restitution of Alsace-Lorraine: Germany was forced to give up Alsace-Lorraine, a resource-rich and populous region that it had annexed following the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

- Financial reparations: Germany was forced to pay massive war reparations to the victim countries, mainly France and the UK. The initial amount of reparations was 132 billion gold marks, a very high figure which was considered by many to be excessive. The payments were to be spread over several decades, but Germany soon ran into economic difficulties and stopped paying the reparations in the 1930s.

These sanctions were highly controversial and contributed to economic and political instability in Germany in the years following World War I. War reparations were also a source of tension between Germany and the Allied powers, particularly France, which insisted that Germany continue to pay reparations even after it stopped paying them in the 1930s.

The sanctions imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles were very harsh and had disastrous consequences for the country economically and politically. The perception that Germany was responsible for the war also led to great national humiliation, which fuelled resentment towards the Allied powers. In the 1920s, Germany experienced a severe economic crisis, marked by hyperinflation and mass unemployment. This economic crisis, combined with the perceived injustice of the sanctions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, created a climate of discontent and political instability in Germany. These conditions contributed to the rise of Nazism, a political movement that exploited nationalist and anti-foreign sentiments in Germany. The Nazi Party, led by Adolf Hitler, won the 1933 elections and quickly established an authoritarian regime in Germany, ending the Weimar Republic.

Two divergent positions existed regarding the reparations imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles.

On the one hand, there were the countries that had suffered great destruction during the war, such as France, Belgium and Serbia, which wanted a strict application of the treaty and financial compensation for their losses. These countries were particularly affected by the consequences of the war and sought fair financial compensation for the damage they had suffered.

On the other hand, the United States and Great Britain had underlying economic interests. They were aware that Germany was an important trading partner and that its economic strangulation could have negative consequences for the world economy as a whole. They therefore advocated a more flexible application of the treaty and a reduction of the reparations imposed on Germany.

This difference in position created tensions between the Allied countries and contributed to the questioning of the Treaty of Versailles in the years following its signing. Eventually, the economic crisis of the 1920s and the rise of Nazism in Germany undermined the implementation of reparations and led the Allies to revise the terms of the treaty.

This opposition was not, however, clear-cut at Versailles. It was clear-cut in the sense that Germany was held responsible; between the letter of the treaty and its implementation there was a great difference, which throughout the 1920s was to oppose antagonistic visions.

In addition to the obligation to pay financial compensation, Germany also had to provide reparations in kind to compensate for the losses suffered by the Allied countries during the war.

Germany had to cede coal mines and steelworks in the east of the country, the most industrialised region, to the Allied countries, in particular France. The Saar mines thus became the property of France for 15 years.

In addition, Germany was forced to reduce its customs duties and open its domestic market to foreign products, in particular French products. This was to enable the Allied countries to export more to Germany, to compensate for the losses suffered during the war and to revive the economies of the Allied countries.

These measures had significant economic consequences for Germany, reducing its ability to produce and market its own products. They also fuelled resentment among the German population towards the Allied countries and contributed to the rise of Nazism in the 1920s and 1930s.

The economic crisis that hit Germany from 1920-1921 made it difficult for the country to pay the reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. This difficulty led to a series of crises, including the Ruhr Crisis in 1923. The Ruhr Crisis erupted when Germany refused to pay the reparations imposed by the Allies and France sent troops to occupy the Ruhr region, an important industrial area that produced steel, coal and other essential materials. The occupation led to a general strike and passive resistance by German workers, which paralysed the region's economy. This crisis had a significant impact on the German economy as a whole, exacerbating the economic and political crisis that already existed in the country. It also increased resentment towards the Allied countries and contributed to the rise of Nazism in Germany.

France occupied the Ruhr region militarily in 1923, in response to Germany's refusal to pay the reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. However, this occupation was opposed by Britain and the United States, which pressured France to abandon the region. This crisis eventually led to a renegotiation of reparations, with the adoption of the Dawes Plan in 1924, which provided for a rescheduling of payments and foreign financial aid to Germany. This Ruhr crisis was important because it symbolised France's loss of power on the international stage. France was forced to submit to the demands of its allies and had to accept a downward renegotiation of reparations, which was seen as a political defeat. This crisis also contributed to the rise of the far right in Germany, which used the Ruhr crisis to criticise the German government and the Allied countries.

The Dawes Plan was an international economic plan proposed in 1924 by Charles Dawes, Vice President of the United States, to help Germany repay the war reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. The plan provided for a system of loans and repayments over several years, as well as guarantees from the British and French governments for German payments. The plan also allowed Germany to benefit from a deferral of reparations payments for the following years. The Dawes Plan was seen as a victory for the United States, as it allowed American banks to lend money to Germany and invest in its economy. Furthermore, it strengthened the position of the United States as the dominant economic power in the world, while Europe was recovering from the First World War.

The Dawes Plan of 1924 was put in place in response to the economic crisis that hit Germany after the First World War. The Treaty of Versailles had imposed large war reparations on Germany which it could not pay without financial help from abroad. The Dawes Plan allowed American banks to invest in Germany by providing low-interest loans to help finance reconstruction and pay off war debts. In exchange, Germany agreed to follow a schedule of reparations payments and to abide by the terms of the agreement.

US banks played a key role in implementing the Dawes Plan by providing low-interest loans to help finance the reconstruction and modernisation of the German economy. These loans were used to build new factories, modernise infrastructure and increase industrial production in Germany. In addition, US banks provided technical assistance to help German companies modernise their production methods and adopt advanced technologies. This assistance enabled Germany to produce high-quality goods and sell them abroad, which helped stimulate economic growth.

The Dawes Plan had different effects on European countries, depending on their position in the world economy and their geopolitical interests.

From Germany's point of view, the Dawes Plan was a boon, as it helped stabilise its economy after the economic crisis following the First World War. American investment modernised German industry, boosted production and exports, and reduced unemployment. In addition, the plan allowed Germany to pay off its war debts in instalments, which reduced the financial pressure on the country. From the French perspective, however, the Dawes Plan was seen as an economic imbalance and a threat to national security. France feared that Germany would not be able to repay its debts and that it would again become a threat to European security. In addition, France saw the Dawes Plan as a way for the United States to extend its economic influence in Europe, which strengthened the economic ties between Germany and the United States.

The Dawes Plan contributed to the economic prosperity of the United States in the 1920s. Loans to Germany allowed American banks to earn interest and make profits. In addition, American investment in Germany created new markets for American companies, which helped boost the export of American goods to Germany. Between 1924 and 1929, American banks received payments for the loans they had granted to Germany. These payments helped strengthen the US banking system and financed new investment in the US. However, it is important to stress that the economic prosperity of the United States in the 1920s was also fuelled by other factors, such as growth in industrial production, mass consumption, technological innovation and the expansion of domestic and foreign markets. The Dawes Plan therefore contributed to American economic prosperity, but it was not the only factor.

The Dawes Plan was replaced in 1929 by the Young Plan, which pursued the same objectives of repairing war debts and stabilising the German economy. The Young Plan was named after Owen D. Young, an American banker who headed the international commission that drafted the plan.

The Young Plan further reduced the reparations payments that Germany had to make to the Allies, which helped to relieve the financial pressure on Germany. In exchange, Germany agreed to implement economic and political reforms to stimulate economic growth and strengthen its political stability.

Like the Dawes Plan, the Young Plan was supported by the United States, which provided loans to help Germany repay its war debts and finance its economic recovery. The Young Plan pursued the objective of reducing Germany's war reparations payments to the Allies by proposing a rescheduling of debts to ease German repayments. Specifically, the Young Plan extended the period of repayment of Germany's war debts to 1988, thereby significantly reducing the amount of annual payments. The Young Plan also provided Germany with additional loans to stimulate its economy, in exchange for the implementation of economic and political reforms aimed at strengthening the country's stability.

However, the Young Plan also faced similar difficulties to those faced by the Dawes Plan, notably the global economic crisis of 1929, which had a considerable impact on Germany and made it more difficult to repay its war debts. In addition, political and military tensions continued to rise in Europe, largely due to the rise of Nazism in Germany and German expansionism in the 1930s. The Young Plan was unable to prevent the escalation of these tensions, which eventually led to the Second World War.

Territorial issues

After the First World War ended, many territorial changes took place in Europe. Some of these changes were decided by the victors of the war as part of the Treaty of Versailles, while others were the result of nationalist movements or regional conflicts. There are seven more states in Europe than in 1914. In 1914, Europe was mainly divided into empires and kingdoms, such as the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of France. At the end of the First World War, these empires collapsed and new states were created, including Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania).

Germany's territorial amputation was significant after the Treaty of Versailles. Territorial losses included Alsace-Lorraine in the west, which was ceded to France, and part of East Prussia in the east, which was given to Poland. The Danzig corridor was also established to give Poland access to the sea. In all, Germany lost about 13% of its territory and 10% of its population. This loss of territory was felt as a great injustice by the Germans and fuelled nationalist resentment, particularly among the Nazis, who used this argument to justify their expansionist policies.

The end of the First World War saw the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the birth of several new states. Austria and Hungary became independent states, while Czechoslovakia was created by combining the Czech and Slovak regions. Part of the Austro-Hungarian territory was attached to Romania, while Italy obtained Trentino and Istria. Finally, Yugoslavia was created by the merger of several regions, including Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia. These territorial changes profoundly altered the map of Europe, with new borders that would generate tensions and conflicts in the years to come.

The Russian Empire broke up after the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Bolshevik takeover. The western part of Russia was affected by the various territorial reconstructions. Thus, Poland regained its independence and the eastern part of Russia. The Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia also gained independence. Finally, Bessarabia was annexed by Romania in 1918.

The Ottoman Empire lost almost all of its Arab possessions to France and Britain, which established mandates over Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Palestine and Transjordan. However, the Empire was not limited to Anatolia, which was only a part of its territory. After the end of the First World War, a war of independence broke out in Anatolia under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, who founded the Republic of Turkey in 1923 and succeeded in having the Treaty of Sevres, which provided for the partition of Turkey, annulled. The 1920 Treaty of Sevres had provided for the creation of an independent Kurdish state, but this was never implemented. Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, fought a war of independence against the Allies and succeeded in having the Treaty of Sevres annulled. The Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 was then signed between Turkey and the Allies, who renounced most of their territorial claims in Anatolia. Kurdistan was not recognised as an independent state in this treaty and was divided between Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria.

The new map of Europe and the Middle East did not fit all actors. National claims were often contradictory and led to tensions in several countries. In Germany, the loss of Alsace-Lorraine was felt as a national humiliation and fuelled German resentment. In Czechoslovakia, German and Hungarian minorities began to claim autonomy, leading to the Sudetenland crisis in 1938. In Yugoslavia, tensions between the different nationalities broke out in 1991, leading to the dissolution of the country. Overall, the new map of Europe and the Middle East failed to resolve the problems of national claims and even contributed to tensions that eventually led to major conflicts.

The inter-war period

The war profoundly transformed the balance of power in Europe and the world, weakening the central empires (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Empire) and strengthening the United States and the Soviet Union. On the other hand, the League of Nations, created in 1919 to maintain world peace, was an attempt to settle international conflicts through cooperation and international law, but it proved powerless in the face of the aggression of fascist states (Italy, Germany, Japan) in the 1930s. In addition, the interwar period was marked by major economic and social upheavals, including the emergence of new industrial powers (USA, Japan, USSR), rising unemployment and social tensions, as well as radical political movements (communism, fascism, Nazism) that challenged the foundations of liberal democracy. Finally, the inter-war period was marked by important cultural and artistic transformations, with the emergence of artistic movements such as Surrealism, Dadaism or Expressionism, as well as the spread of mass culture with the appearance of cinema, radio and the written press. Thus, the inter-war period was a pivotal time in world history, marked by major political, economic, social and cultural upheavals, which profoundly transformed the world and set the stage for the dramatic events that were to follow in the 1930s and 1940s.

The new geopolitical situation

The First World War brought about major geopolitical changes in Europe and the world. The Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919, redrawn the borders of Europe and imposed massive war reparations on Germany. It also created the League of Nations, which aimed to promote international peace and cooperation. However, the Treaty of Versailles failed to maintain peace in Europe, and the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s led to the Second World War.

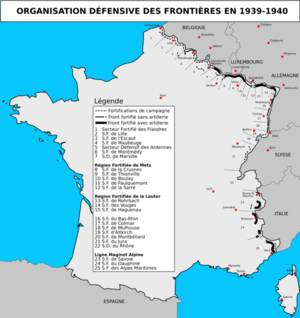

- France is considered to be on the winning side, thanks to its participation in the First World War and its reputation of having the best army in the world. However, despite these past successes, France faced a weakening of its power and was obsessed with its security throughout the inter-war period. Although economically strangled, Germany retained significant economic potential because of the little destruction it had suffered in the First World War. This worried France, which sought to recover its power and prevent the reorganisation of the German army and its economic recovery. France relied on alliances of setbacks, notably with Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia, to encircle Germany and limit its capacity to act. The construction of the Maginot Line is an example of this defensive strategy put in place by France to prevent a German invasion. However, despite these efforts, France was seen as a declining power because of its difficulties in regaining its dominant position and its obsession with its security in the face of Germany.

- Great Britain: Britain emerged from the First World War seemingly strengthened, thanks in particular to the increase in its colonial empire following the conquest of the German colonies in Africa and the establishment of mandates in the Middle East. However, it faced economic and social difficulties, pushing it into relative decline and placing it second only to the United States. Its status as the world's leading financial centre was also challenged by the United States, which now held the majority of the world's gold stock after the war. In the inter-war period, Great Britain was unable to play its role as arbiter on the European scene, unable to counter the rise of Nazi Germany. In addition, from 1931 onwards, Britain granted independence to its dominions, such as Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia, which marked a loss of influence for the UK. Despite these difficulties, Britain remained a major power on the world stage, with considerable influence in many areas. However, its relative decline and the rise of the United States are important factors that will influence the history of Europe and the world in the years to come.

- United States: The United States was undoubtedly the big winner of the First World War, becoming a world power that imposed its vision of international order under the leadership of President Wilson. However, in 1920, the US Congress disavowed Wilson by refusing to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and join the League of Nations, causing a relative return to isolationism. Despite this, the United States continued to intervene in various parts of the world. In Latin America, its economic and military presence was strengthened, particularly in Haiti, Nicaragua and Panama, to the detriment of France and Britain, which had to redirect their financial flows to the war effort. In the Far East, the Treaty of Washington forced Japan and Britain to ally themselves with the United States, forcing the Japanese to give up their presence in China and to scale back their ambitions. In the Middle East, the 1920s were marked by bargaining between the European powers and the French, German, British and American oil companies. The United States became a major player in the region, seeking to defend its economic interests while becoming politically involved in the region.

Germany and Italy were deeply affected by the rise of totalitarian regimes in the 1920s and 1930s. In Germany, the economic and political crisis led to the rise to power of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in 1933. Hitler established a dictatorial regime, the Third Reich, which eliminated political opponents, Jews and other minorities and pursued a policy of aggressive territorial expansion that led to the Second World War. In Italy, Benito Mussolini's Fascist Party came to power in 1922, after a march on Rome. Mussolini established an authoritarian regime that eliminated political opponents, the free press and created a cult of personality around him. He pursued an expansionist policy in North Africa and formed the Axis with Nazi Germany during the Second World War. Both totalitarian regimes had dramatic consequences for Europe and the world. They led to the deaths of millions of people, caused immense material destruction and disrupted the international political and economic order. The fall of these regimes after the Second World War led to the reconstruction of Europe and the emergence of a new world order.

- Italy: Mussolini exploited the theme of mutilated victory, i.e. that not all his claims had been met, in particular his desire to annex Dalmatia. To compensate for this, Mussolini engaged in colonial expansion, notably in Ethiopia. He also set up an authoritarian and fascist regime, inspired by Nazi ideologies in Germany. The cult of personality, the standardisation of the army and youth movements are all symbols of this rise in power of Italian fascism. In foreign policy, Mussolini sought to extend Italy's influence in the Mediterranean by concluding agreements with Germany and Japan as part of the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis. However, this expansionist policy led to military defeats and eventually to the fall of the Fascist regime in 1943.

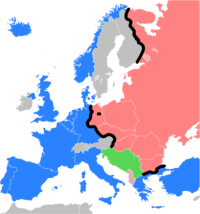

- Germany: Germany is a country marked by the rise of totalitarianism. After the defeat in the First World War, the Treaty of Versailles humiliated and demilitarised Germany. The weakness of the German democratic tradition led to the fall of the Weimar Republic and the rise of the Nazi party led by Adolf Hitler. From the moment he came to power in 1933, Hitler set out to overturn the Treaty of Versailles:

- In 1935, he reinstated military service in Germany. The Treaty of Versailles had reduced the German army to 100,000 men in the form of a professional army, thus prohibiting conscription.

- In 1936, Hitler remilitarised the Rhineland, a demilitarised zone since the end of the First World War. He stationed troops next to the French border, which created great international tension.

- In 1938, at the Munich Conference, Hitler obtained the annexation of the Sudetenland, a Czech region populated by Germans. This was done without the agreement of Czechoslovakia and France and the United Kingdom, who gave in to German demands to avoid war.

- In 1939, Hitler seized Czechoslovakia and invaded Poland, triggering the Second World War. Nazi Germany's expansionist policies led to rising international tensions and an arms race, which helped to push the world into war.

In the aftermath of the First World War, a large part of the European population wanted peace at all costs. The memories of the war were still very present and the reconstruction of the continent required considerable effort. However, this pacifist mentality was gradually eroded in the 1930s with the rise to power of authoritarian leaders such as Hitler in Germany and Mussolini in Italy. Faced with these regimes that challenged the established order, the French and British tried to preserve peace at all costs, even to the point of making major concessions. The aim was to avoid a new war that could have been even more deadly than the previous one and cause even greater economic damage. This conciliatory attitude led to a series of compromises that ultimately encouraged German and Italian expansionism. Thus, the policy of appeasement pursued by the French and British leaders was widely criticised for allowing the rise of totalitarian regimes and the outbreak of the Second World War. This period marked a profound change in the world order of the 20th century and led to an awareness of the need to preserve peace at all costs, without giving in to pressure from authoritarian regimes.

- After the Russian Revolution of 1917, "Russia" went through a period of chaos and civil war which considerably weakened its influence. In 1922, it was replaced by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which had a centralised, communist political system. Under Stalin's rule, the USSR sought to consolidate its internal power by eliminating all political opposition and developing a planned economy. The creation of the USSR in 1922 allowed Russia to regain its position as an international power after a period of chaos in the 1920s. The USSR proceeded to reclaim some of its former possessions, notably Ukraine, which had been lost after the 1917 revolution. Internationally, the USSR tried to export the communist revolution to other countries, but this policy was not very effective. From the 1930s onwards, the USSR adopted a more pragmatic foreign policy, based on realism and the defence of its national interests. In 1934, the Soviet Union joined the League of Nations, while continuing its policy of expansion and support for revolutionary movements around the world. This policy was motivated by the idea that the proletarian revolution could not triumph in a single country and had to spread internationally. However, with the arrival of Stalin in power, this policy of exporting the revolution was gradually abandoned in favour of the consolidation of socialism in the USSR. In 1939, the USSR signed the German-Soviet pact with Nazi Germany, which allowed it to protect itself from a German invasion and to gain time to prepare for war. The German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, also known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, was signed in August 1939 between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. Although the two regimes were ideologically opposed, they saw the value of signing a non-aggression pact to avoid an immediate war between them and to share influence in Eastern Europe. The pact also bought the Soviet Union time to strengthen its army and prepare its defence against a possible German invasion. However, in June 1941, Germany broke the pact by launching a surprise invasion of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union's participation in the Second World War was decisive and enabled the USSR to regain great geopolitical power. The Red Army fought major battles against Nazi forces on the Eastern Front, inflicting heavy losses on the Germans and contributing greatly to the defeat of Nazi Germany. This victory enabled the Soviet Union to reinforce its great power status and become one of the two post-war world superpowers, alongside the United States.

- Japan joined the Allied forces and had little military involvement in the conflict, but benefited from the economic enrichment of its participation as a supplier of goods and services to the warring countries. Japan also benefited from the Allied victory by gaining the German colonies in the Pacific, which gave it territorial advantages and relays to cover the Pacific Ocean. Japan took advantage of Germany's weakening to seize its colonies in the Pacific, including the Mariana Islands, the Caroline Islands and the Marshall Islands. These territories allowed Japan to expand its area of influence in the region and strengthen its geopolitical position in the Pacific. However, Japan faced American opposition to its territorial expansion into China in the 1920s, and this contributed to a rise in tensions between the two countries. In 1922, the United States signed the Washington Treaty with Japan and other powers, with the aim of limiting the naval arms race in Asia. The Washington Treaty also established a limit to Japanese territorial expansion into China. However, Japan continued to expand its influence in China in the 1930s, which eventually led to the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. After being halted in its territorial ambitions in China by the United States in the 1920s, Japan saw its ambitions expand to the entire Far East. This trend became more pronounced with the rise of the military to power in the 1930s, with an increasingly hawkish and expansionist policy. Japan thus sought to establish a co-prosperity sphere in East Asia, under its economic and political dominance, with the aim of freeing itself from dependence on Western powers and becoming a major world power. This led to growing tensions with the United States and other Western powers, eventually leading to the Pacific War.

After the First World War, the European geopolitical scene was profoundly transformed, with the disappearance of the German Empire and the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As a result, there was no longer a dominant power in Europe, which created a power vacuum in the region. At the same time, the United States and Japan emerged as increasingly ambitious powers, seeking to extend their influence around the world. This created a new geopolitical situation, in which the interests of the different powers were in conflict, contributing to rising tensions and the preparation of a new global conflict.

The impossible resolution of economic problems

From 1918 onwards, the economy took on a central role in international relations, resulting in several consequences, notably the eruption of international economic problems:

- question of the transfer of wealth from Europe to the United States: The First World War had major economic consequences for Europe, particularly with regard to the transfer of wealth to the United States. France and Britain had to spend huge sums of money to finance the war effort, including buying weapons and military equipment from the United States. This led to a massive transfer of wealth from Europe to the United States, which became a major economic player in the world. In the aftermath of the war, three quarters of the gold stocks were held by the US. European countries were forced to sell their gold to pay their war debts, which contributed to the depreciation of their currencies and inflation. The situation worsened with the collapse of the European economy in the 1920s. European countries experienced considerable economic hardship, while the United States enjoyed a period of sustained economic growth. The US invested heavily in Europe, but these investments were often aimed at strengthening US economic interests rather than promoting European growth.

- disorganisation of European trade: The First World War had a major impact on international trade, particularly in Europe. Before the war, Europe was the hub of world trade, with significant trade between the different European countries. However, the war completely disrupted these trade routes, and by the end of the war, intra-European trade was in disarray. The war had led to massive destruction of material goods, including transport and communication infrastructure. In addition, trade had been interrupted due to the armed conflicts. Economic blockades and import/export restrictions had also disrupted international trade. After the war, the situation worsened due to inflation, currency devaluation and shortages of raw materials, all of which disrupted trade. European countries also experienced difficulties in rebuilding their economies, which slowed the recovery of intra-European trade.

- Inflation was a constant in the post-1914-1918 period. Before the war, the production of money was linked to the amount of gold in reserve, which limited the amount of money in circulation and stabilised prices. However, during the war, states had to produce money to finance the war effort, without being able to maintain their gold reserves. This need for additional financing led governments to create money that was no longer indexed to gold, leading to short-term inflation. After the war, this money creation continued, causing the economy to overheat and creating inflation, which became a constant in the inter-war economy. Factors such as the reconstruction of Europe, the rise of mass industry, currency devaluation and demand growth also contributed to inflation. This inflation had a negative impact on the economy, leading to a decrease in the value of money and price instability which complicated the economic situation at the time.

- The war left many economic problems that had a significant impact on the interwar period. These included the reorganisation of international trade, the question of reparations and the question of access to energy sources. In particular, the question of access to energy sources became a major issue in the inter-war period. New technologies were developed, especially in the field of transport, which required the use of fuels, such as oil. The demand for these scarce and strategic resources increased, raising the issue of access to energy sources. States that had these resources sought to control them for their own energy and economic security, while states that lacked them sought to obtain them by any means possible, including force. This has led to geopolitical tensions, conflicts and alliances between states. The question of access to energy sources remained a major issue throughout the inter-war period and beyond, with repercussions for the foreign policy of states and for the world economy.

The stock market crash of 1929 had dramatic economic consequences throughout the world, including Europe. American banks were hit hard, leading to a fall in American investment in Europe, particularly in Germany and Austria. This led to a series of bank failures in Europe, particularly in Germany and Austria, which exacerbated the economic crisis in these countries. The economic crisis undermined the foundations of the Versailles peace, in particular the reparations clauses imposed on Germany. Germany refused to pay its debts, which led to France and Britain refusing to pay their own debts to the US. This created tensions between European countries, further aggravating the economic crisis. These economic problems played a major role in the rising tensions that led to the Second World War. The economic crisis contributed to the rise of nationalism and political extremism in Europe, and also weakened European democracies. Ultimately, these factors created the conditions that allowed Hitler to take power in Germany and start the Second World War.

The rise of colonial nationalisms

The rise of colonial nationalisms was characterised by several elements that led to the weakening of empires during the interwar period:

- The participation of the colonies in the war was seen as an opportunity to improve their status. However, the mobilisation of the war effort was not followed by the promised compensation. For example, India had negotiated its participation in the war in exchange for an improved autonomous status, but this was not honoured. This lack of reward contributed to the crystallisation of nationalist movements. Similarly, other colonies were also treated unfairly and did not receive the benefits promised in exchange for their participation in the war. This situation reinforced a sense of injustice and discontent among the colonised populations, contributing to the emergence of nationalist movements and the struggle for independence in many colonies.

- The rise of the educated middle classes in the colonies led to a growing demand for participation in power. However, the metropoles systematically excluded the natives by creating few representative assemblies and limiting their representation. This created growing frustration among the middle classes. These restrictions were particularly evident in the African and Asian colonies, where Europeans were often in a very small minority and natives were largely excluded from important political and economic spheres. This led to the emergence of nationalist movements and struggles for independence which were sometimes violent, as was the case in the French colonies of Algeria and Indochina.

- The protest movements against colonial exploitation were increasingly numerous. Colonisation was mainly a phenomenon of political domination and economic exploitation. The metropolises took advantage of the resources of the colonies without allowing reciprocity. This situation has been increasingly challenged. In many cases, settlers have exploited the natural resources of the colonies without reinvesting the profits in the development of the local economy. Extractive industries, such as mining and logging, have often had a negative impact on the environment and local populations. In addition, metropolises have often imposed economic policies that have favoured their interests over those of the colonies. Unfair trade practices, high taxes on local products and the subordination of colonial economies to the metropole's economy often led to significant economic imbalances. In response to these practices, protest movements sought to highlight the demands of local populations. They often demanded a more equitable distribution of resources, equal access to education and economic opportunities, and greater political autonomy.

- Democratisation in Europe has become a model that has led to a loss of prestige of the European model. Although there was a process of deepening democracy in European countries in the 1910s-1920s, this model was criticised and used as an example for the colonies to follow. However, this process of democratisation did not affect the colonies. The elites of the colonial countries witnessed this democratisation phenomenon and it did not affect them. This helped to fuel the nationalist movement and the struggle for independence in the colonies, where the indigenous populations demanded greater political participation and autonomy. Elites in the colonial countries saw democratisation in Europe as proof of human capacity for self-government and therefore demanded equal participation in decision-making processes in their own countries. This demand was motivated by the aspiration for greater autonomy and political equality, which were seen as natural rights. However, the metropolises often refused to recognise these demands and maintained their political dominance over the colonies. This led to growing frustration and stronger contestation of colonial rule, which eventually led to protest movements and struggles for independence.

- The influence of the Russian Revolution was a momentous event. The Russian Revolution of 1917 significantly influenced the colonies, particularly in North Africa and Indochina. The revolution provided an alternative model for political and social organisation that was very attractive to many nationalist movements in the colonies. Communist ideals, such as social equality and collective ownership of the means of production, were presented as an alternative to the unjust and exploitative colonial system. Nationalist movements in the colonies adopted the ideas and tactics of the Russian Revolution, such as militancy, mass mobilisation, strikes and armed struggle. The Russian Revolution also provided a model for political organisation. Communist parties were created in the colonies, and were used as a means of mobilising the masses and fighting against colonial rule. Communist parties were also used as a platform for the promotion of independence and political autonomy. In North Africa, the Russian Revolution significantly impacted the Algerian nationalist movement. The Algerian Communist Party, founded in 1936, was an important force in the struggle for Algerian independence. In Indochina, the Russian revolution was also a source of inspiration for the Vietnamese nationalist movements, which created their own communist party, the Vietnamese Communist Party.

- The revival of local religions was another breeding ground for nationalist movements. The revival of local religions was another breeding ground for nationalist movements in the colonies. In many colonised countries, religion has been used to assert national identity and cultural specificity in the face of colonial domination. In the Arab world, the revival of Islam has been intimately linked to the development of nationalist movements. Arab nationalist movements have used Islam as central to their political vision, presenting Islam as a foundation of Arab identity and culture. Arab nationalist movements have also used Islam to mobilise the masses, especially the working and rural classes. In India, the revival of Buddhism accompanied the independence movements. Indian leader B.R. Ambedkar encouraged Dalits, the 'untouchables' of Indian society, to convert to Buddhism as a form of protest against colonial rule and caste discrimination. Ambedkar saw Buddhism as an alternative to Hindu domination, and encouraged conversion to Buddhism as a means of emancipation from colonial domination and caste discrimination.

The globalisation of confrontations

The inter-war period was marked by an intensification of the globalisation of confrontations. The areas of tension increased in number and intensity, reflecting the rise of nationalism and territorial claims in many parts of the world. In Europe, the rise of Nazism and Fascism led to the Second World War, with dramatic consequences for the whole continent. In Asia, Japanese expansionism led to conflicts with China and other countries in the region, resulting in the Sino-Japanese War and Japan's participation in the Second World War. In Latin America, territorial conflicts were exacerbated by US imperialism and the 'Big Stick' doctrine, with military interventions in several countries in the region. In Africa, colonial rivalries led to bloody conflicts, especially within the French empire. In this context, the League of Nations, created after the First World War to promote international peace and cooperation, has shown its limitations. Despite its efforts to resolve conflicts, it did not succeed in preventing the rise of tensions and the multiplication of confrontations throughout the world.