« The War: Concepts and Evolutions » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

|||

| Ligne 43 : | Ligne 43 : | ||

It is also necessary to question this idea because political modernity with the emergence of the State also sees the emergence of new forms of violence which have been developed and which have little to envy with forms of primitive violence. They are forms of violence linked to modernity such as genocide, which is a form of violence that is eminently linked to the development of a modern and industrial state. In order to organize a massacre on a large scale, we need large capacities. Total war is also a deadly mode of warfare with the First and Second World Wars. Ultimately, this modernity of the state and this conception of modernity leads to a twentieth century that was the most violent century of all time. In the twentieth century, in terms of political violence, there were more than 200 million deaths, of which between 130 and 140 million were directly related to the war. The difference is that political violence can be, for example, that of a repressive regime within a state. These figures are enormous, there is this paradox where the modern state is supposed to offer peace and stability within its borders, but the period has culminated in a time when there have never been so many deaths due to political violence. It's pretty paradoxical. | It is also necessary to question this idea because political modernity with the emergence of the State also sees the emergence of new forms of violence which have been developed and which have little to envy with forms of primitive violence. They are forms of violence linked to modernity such as genocide, which is a form of violence that is eminently linked to the development of a modern and industrial state. In order to organize a massacre on a large scale, we need large capacities. Total war is also a deadly mode of warfare with the First and Second World Wars. Ultimately, this modernity of the state and this conception of modernity leads to a twentieth century that was the most violent century of all time. In the twentieth century, in terms of political violence, there were more than 200 million deaths, of which between 130 and 140 million were directly related to the war. The difference is that political violence can be, for example, that of a repressive regime within a state. These figures are enormous, there is this paradox where the modern state is supposed to offer peace and stability within its borders, but the period has culminated in a time when there have never been so many deaths due to political violence. It's pretty paradoxical. | ||

= | = The birth of modern warfare = | ||

{{Article détaillé|La naissance de la guerre moderne : war-making et state-making dans une perspective occidentale}} | {{Article détaillé|La naissance de la guerre moderne : war-making et state-making dans une perspective occidentale}} | ||

== | == A state affair: War-Making/State-Making == | ||

[[Fichier:Passage de la Seine par armee anglaise et pillage Vitry XIVe siecle.jpg|vignette|droite]] | [[Fichier:Passage de la Seine par armee anglaise et pillage Vitry XIVe siecle.jpg|vignette|droite]] | ||

In order to study war, one must first of all focus on its links with the modern state as a political organization. We will see how war is today through and through the emergence of the modern state. We will start by seeing that war is a state matter. In order to introduce the idea that war is linked to the very construction of the state and the emergence of the state as a form of political organization in Europe from the end of the Middle Ages, for this reason, the best way to do so is as brought about by the sociohistorian Charles Tilly in his article War Making and State Making as Organized Crime which developed the idea of war making/state making: the state and vice versa. | |||

Tilly | Tilly reports on the western trajectory of state building. When we talk about the modern state and the role of war, we are really talking about its emergence in Europe from the end of the Middle Ages onwards. That is to say, there are other forms of political entities in the world that follow different trajectories and if the European trajectory seems so important today, it is true that, particularly through colonisation, where today through the construction of the state or nation building, we are trying to export the European model because we assume that it is the only model that could be imposed on others. It creates some friction sometimes. | ||

Through the idea of war making/state making, Tilly will translate that it is a process that takes several hundred years, but is not an intentional process. It describes the process of war making/state making through two operations that are two related competitions or phenomena.[[Fichier:Einhard vita-karoli 13th-cent.jpg|vignette|left]] | |||

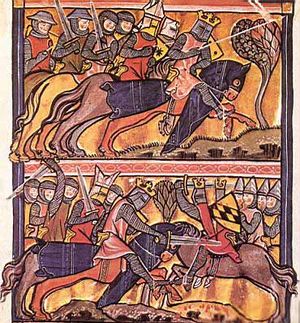

First of all, the time of the exit of the Middle Ages coincided with an internal competition within the kingdoms between the lords. This happens at the time of feudalism when there was a king and different lords who had their fiefdoms in some form of allegiance to the king, but who were completely autonomous in the management of their affairs. The only connection they had with royalty was often through the war. The king addressed these feudal lords to raise men for war. Over several centuries, according to Tilly, there is an increasing competition between these lords because everyone wants to enlarge their territory. The Middle Ages is like a generalized "state of war" where everyone tries to enlarge their territory; both within what is beginning to become a state and outside with these entities. | |||

[[Fichier:France sous Louis XI.jpg|300px|vignette|right]] | [[Fichier:France sous Louis XI.jpg|300px|vignette|right]] | ||

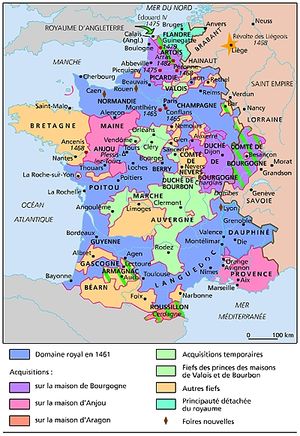

Using Norbert Elias's idea, he spoke of a "elimination struggle". That is to say, there is less and less fighting. With the example of France under Louis XI in the XVth century, we can clearly see this logic which is put in place where we see in "blue" the territories that belong to the State, thus belonging to the King with a process of construction of the State well advanced which begins already two centuries before where the territories of the King of France were much smaller. More and more, through marriages, wars, successions and the disappearance of families, there is a tendency to have less and less territory and more and more one that will prevail. Internally, states have emerged in this form in most European countries. Often, the most emblematic cases are those of France and Great Britain. | |||

In addition to the internal competition, there is an external competition. For example, in the time of Louis XI, he began to wage more and more wars abroad, and in order to be able to wage these wars, he needed resources, but also to reunify the Christian world. Since the Papacy has not been able to reunify the Christian world, these states each want to create what resembles these empires. These empires will not be created because they will all grow and meet and create a system called an international system. War as an institution of the "interstate system". | |||

What we must remember from the idea of War-Making/ State-Making is that in order to be able to conduct these wars to continue to grow as an entity, it takes a lot of resources. To have the resources, we must have the means to extract these resources, and to fight wars, we need armies. This is where we see the link between resource extraction and the need to wage war, which will allow states to be built by the same phenomenon. In other words, in order to have an army that holds its own, it is necessary to have a population, to register, to maintain the army, it is necessary to have money, to have money, it is necessary to raise taxes, and in order to do so, it is necessary for people to know who lives where and to convince people of their legitimacy so that they can agree to pay without necessarily having to force them to pay taxes through violence. We are increasingly in the process of setting up efficient bureaucracies that extract resources from the territory in order to wage war. Constantly having to wage war requires increasingly efficient extraction of resources from a territory. It took several hundred years, but it is through this process according to Tilly that the born modern state is in the process of war. | |||

Since the end of the Middle Ages, war has appeared as an institution that is at the base of an inter-state system that is at the base of a great impact on our daily lives. This idea comes from Europe at the end of the Middle Ages, which is the result of imperial pretensions and competitions between different states that started empires, some tried like Napoleon who wanted to build a territory that knew no borders and was an inclusive territory. But there is a sort of balance of forces that has been built up between all these powers in the long run. By eliminating each other, among all these powers, we have come to the emergence of a State whose strength was more or less equal in the long term, stabilizing around borders and meeting around those borders. From this, the idea of sovereignty emerges, that is to say, the idea of authority over the territory is divided into spaces where sovereignties are exercised and exclusive to each other. That is really the principle of an international system divided between sovereign states. | |||

In the long term, a universalism of the national state which is not that of the Empire develops around the principle of sovereignty, since the principle of sovereignty is recognized by all as the organizing principle of the international system. That is the principle of the United Nations, for example, because it recognizes the principle of equality among all sovereign States. The idea of the United Nations stems from the idea of sovereignty as the organizer of the international system. This inter-state system, which is being set up, is organized around the idea that there is a logic of internal balance where the State administers a territory, i. e. the "police"; and external balance where the States regulate their affairs among themselves. It is this distinction of space that is fundamental here. There is an internal space which is the responsibility of the State which administers and administers the accounts of its citizens and the external space where the State has this mandate in order to manage the relationship with other States. | |||

When all these states are trained, they have to communicate with each other. Since everyone has to survive as a state and there are other states out there, how are we going to communicate? If we assume that war is an institution, it is used to do just that. According to Vasquez, war is a learned mode of political decision-making in which two or more political units allocate material or symbolic goods on the basis of violent competition. In other words, war makes it possible to settle a competition; we do not agree, so we settle this through war. We move away from the idea of war as something anarchic or violent, war is something that has been developed in its modern conception to settle disputes between states, it is a mechanism for conflict resolution. It seems counter-intuitive. | |||

First and foremost, war is to be understood as something that settles disputes. That is to say, if we disagree, we take resources, namely those armies, prepared by collecting taxes sent to fight against each other and from the moment one of them wins, the dispute is settled for the benefit of one or the other. | |||

[[Fichier:1280px-Ajaccio tempesti bataille.JPG|vignette|left| | [[Fichier:1280px-Ajaccio tempesti bataille.JPG|vignette|left|Battle scene at the Fesch Museum of Ajaccio by Antonio Tempesta.]] | ||

War can be seen from different angles, whether from a humanitarian point of view through the deaths they cause or from a legal point of view in relation to its regulation itself, and what are the legal stakes in the constitution of the various mechanisms for managing warfare. The angle of this course is political science to see where this phenomenon comes from and what it is used for. We are not interested here in the normative dimension of war. | |||

We come to the idea that war is a mechanism for conflict resolution and that, if the strategy to an end, the end and purpose of this strategy is peace. The two are linked; we are in a conception where peace is intimately linked to war and, above all, the definition of peace is intimately linked to war. Peace is understood as the absence of war. It is interesting to see how the goal of the strategy is to win and return to a state of peace. It is the war that really determines this state. There is a very strong dialectic between the two. We are interested in the relationship between war and state, but also between war and peace. It's a relationship that is fundamental and it's a relationship that we're not going to be interested in today. | |||

We are talking about peace, because what is important is that in the conception of war, which is taking shape with the emergence of this inter-state system, that is to say with states which are formed within and compete with each other outside, war is not a goal in itself, the goal is not the conduct of war itself, but peace; we go to war to get something. This is Raymon Aron's design. | |||

To focus on the conception of war as a conflict resolution mechanism that allows us to do things, to obtain things, to "strategize" our objectives. | |||

== Carl von Clausewitz (1780 – 1832) | == Carl von Clausewitz (1780 – 1832) == | ||

[[Fichier:Clausewitz.jpg|vignette|200px|droite|Carl von Clausewitz.]] | [[Fichier:Clausewitz.jpg|vignette|200px|droite|Carl von Clausewitz.]] | ||

If one speaks of war, in his figure of theorization which is the most famous is Carl von Clausewitz who is a Prussian officer who exercised during the Napoleonic wars to write the book ''On War''. Clausewitz will, if not fixed, be considered as the reference in the theorizing of war. It will pose an eminently political conception of war, which still remains a reference today. | |||

Clausewitz | Clausewitz defines war as an act of violence intended to compel the opponent to carry out our will. It is a very rational framework, it is not a logic of "war madman". War is waged in order to obtain something. According to Clausewitz,"War is the continuation of politics by other means. Imagine a state that is a government with an objective that is for example that of extending fertile lands, then the neighbour's lands have become an objective. Since he will not give them away, war will be declared to him, if the warring state wins, he will make a peace treaty and get the land. It is an eminently political conception of war in the sense that war is subordinate to politics. It is politics that determines what can be achieved through war because it cannot be achieved by other means, such as diplomacy or trade. There is a time when you can't get it otherwise, so you go to war in order to get it. This involves returning to normalcy, which is a state of peace. | ||

== | == The Westphalian system == | ||

From the 17th century and the end of the Thirty Years' War, the Westphalian system was established. Alongside the construction of the modern state, there is a whole thought in political theory in order to think about war, but also to codify it. A Dutch jurist, Hugo de Groot says Grotius, who from the 17th century onwards codified war, in terms of what could be done before the war, during the war and after the war that led to the codification of the law, but also the Geneva Conventions. The emergence of war in the inter-state system is accompanied by a desire to introduce very specific rules for the conduct of war: war must be declared, war is a moment of intense and extremely violent violence, but it is extremely well regulated. We must bear in mind all the efforts that have been made since then, it has been regulated and set rules that allow the war to be waged and used for this political purpose. In other words, war really is part of this inter-state system. | |||

[[Image:Helst, Peace of Münster.jpg|thumb|400px|<center> | [[Image:Helst, Peace of Münster.jpg|thumb|400px|<center> | ||

Amsterdam Guardia Civil Banquet for the Peace of Münster (1648), exhibited at the Rijksmuseum, by Bartholomeus van der Helst. | |||

]] | |||

The Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 includes the Treaty of Osnabrück and the Treaty of Münster. They marked the end of the Thirty Years' War from 1618 to 1648, a reference to the religious war on the European continent between Catholics and Protestants, and at the end of these wars, a treaty was reached which enshrined the existence and emergence of the State as the basis for the system of organization between the entities and political units on the European continent, giving rise to the Westphalian system. The first references in Switzerland's official documents are to the Treaty of Westphalia, even though Switzerland as a state took some time to emerge in its modern form. It is the moment when the State is established as the basis of this system and, above all, the sovereignty is recognized, which is the fact that each State exercises on its territory the organizing principle of this system. We are not in an imperial logic, but in a logic where each entity exercises sovereignty over a given territory. Everyone recognizes that everyone does what they want to do at home, but when there is a dispute, war remains a means of settling it. | |||

It is important to understand this distinction of space between an inner space where the rules are clear, where it is the State as such that has sovereignty to exercise power, which is recognized; and there is outside the State where there is no authority in the form of sovereignty. Even today, there is no world government, we are not in an empire of states, the territories of the planet being divided into states where there are about 200 sovereignties exercised exclusively. It is a principle, there are States stronger than others that impose their will, but as a principle of law and the organization of the system, it is from there that everything is put in place and still today, they occupy an extremely important place even if today we speak of non-state actors such as multinational corporations or non-governmental organizations that are of some importance and have a rather important role. The State is still at the base of what is called the "international system". | |||

We are not talking about "global studies" or "global studies". The term "international relations", which means thinking about the world is to think beyond the borders of the state to show how important the moment of structuring space between states is. | |||

The Treaty of Westphalia enshrines sovereign equality as the organizing principle of the international system and enshrines the principle that everyone does what he or she wants at home and that when a dispute arises, war is fought. | |||

== | == Towards Total War == | ||

From the seventeenth century onwards, there was a system in place that was accompanied and accompanied by the constitution of the role of the State; at the same time, these two processes were concomitant, took place simultaneously and influenced each other. From there, through the structuring of this system, with more and more powerful states, which industrialize and manage to extract more and more resources, to become more and more efficient, making it possible to go towards total war. | |||

We enter this paradox where states that are increasingly effective in their internal management are reducing interpersonal violence, but paradoxically, there are wars that are extremely deadly if not more and more lethal. That is to say, if we make a distinction in the evolution of warfare, we have gone from a war in the Middle Ages where things are less clear at the level of the international system, where there is no discrimination between civilians and combatants, i. e. when the war is going to be codified, it will clarify the role of combatants and try to exclude civilians from conflicts. It will work because from the seventeenth century onwards, there will be fewer and fewer civilians involved in wars, and it will cause fewer and fewer civilian casualties in wars, the majority of which are military, and this is a phenomenon that will last until the end of the Cold War, when this figure is again reversed. | |||

It is important to speak of war in relation to the emergence of the state because in the Middle Ages, these are more states of violence than wars in which there are different types of political units with city-states, the papacy, warlords who change affiliation according to their interests of the moment, it is much more fluid, there are different forces that fight since modern warfare is linked to the emergence. Whereas in the Middle Ages, there was a mixture, the statutes were much less clear, there were different types of actors, and there were not only agents of the State who fought each other. | |||

== | == Limited/institutionalized/trinitarian wars (of the "first type" according to Holsti): 1648 -1789 == | ||

From the peace of Westphalia, where war was established as a means of regulating violence between all the entities that make up the Westphalian system, wars became institutionalized. | |||

Since the Treaty of Westphalia, wars have become institutionalized. In ''The State, War and the State of War'', published in 2001, Holsti makes a well-known distinction between the different types of warfare, often referring to first type warfare at the end of the Middle Ages. Between 1648 and 1789, we are talking about wars that are relatively short, lasting from one to two years, with quite clear sequencing, so with a declaration of war, a ceasefire, a peace treaty; the war is increasingly codified and everyone is playing the game more and more with limited objectives, limited interests being in a Clausewitzian conception. | |||

It is also a time of codification where there are no longer any roles that are not well established, there are uniforms, codes of conduct that are being put in place, but also a military tradition around the "nobility of the sword" that is also being put in place, this is where the armies of Western states as we still know them today are born. These are wars that are limited in time and space, there are clear objectives and it is a maneuver war rather than annihilation. | |||

The army is used to get things decided in advance. However, there were still a lot of wars at the time. We are not talking about peace or outlawing war, but it is an effort to codify this war in which civilians are a little more spared and the number of victims is relatively limited. | |||

The symptomatic war of the time and the Spanish War of Succession where there are a series of brutal conflicts at the time, but limited in time between different European states. It is therefore a time when armies are codified, uniforms are emerging, and we distinguish ourselves through uniforms. This distinction is important because States are also shouting at each other about the fact that we also differentiate ourselves according to uniforms. | |||

== | == The Second Type War or Total War: 1789 - 1815 and 1914 - 1945 == | ||

[[File:Charles Meynier - Napoleon in Berlin.png|thumb|''Napoleon in Berlin'' (Meynier). After defeating Prussian forces at Jena, the French Army entered Berlin on 27 October 1806.]] | [[File:Charles Meynier - Napoleon in Berlin.png|thumb|''Napoleon in Berlin'' (Meynier). After defeating Prussian forces at Jena, the French Army entered Berlin on 27 October 1806.]] | ||

By remaining on the typology of Holsti, we enter the second type wars. From 1789 and the French Revolution onwards, revolutionary wars began and the novelty, which remained extremely linked to the construction of the State, was entered into mass levees with the concept of "Nation en armes". | |||

With the French Revolution, the European princes joined forces to invade France, and the revolutionary reaction was set up with the mass raising and the establishment of a conscription army. Beyond the poetic side of the revolution, this implies that it is above all a relatively modern state that can afford conscription leading to military service, which is the fact that we can mobilize huge numbers of people quickly, arm them, train them and send them into combat. As such, a much less developed state is needed to hire a few hundred mercenaries and send them to fight. Setting up an entire army is much more complicated than simply buying a service. The development of these conscription armies made it possible to raise huge armies in terms of men, size and efficiency. Second type wars are the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars after which they are nationalist armies, meaning that they are no longer professional armies as was often the case before, based on mercenarism. The paradox with the beauty of the revolutionary cause, where it is a people who rise up against an enemy who attacks our ideals, but when a revolutionary war is waged, the goal is not just to gain a few square kilometers, the goal is to annihilate the enemy because it challenges our existence. We enter into much more lethal logics with the second type of wars, which are linked to the revolutionary wars of the time. The objectives become unlimited, unclear and are not concrete like the concepts of "liberation","democracy","class struggle" and imply unconditional surrender. | |||

The Second World War is symptomatic of this phenomenon because with the struggle against Nazism, we are not in a logic of capitulation where everyone stays at home afterward; when one enters this type of war, one enters a logic of unconditional capitulation, the objective is to annihilate one's enemy. It is a transformation of war, but it is eminently linked to state building. In order to arrive at something like the Second World War with a fight against Nazism, in order for Nazism to emerge, it took a state to develop, otherwise there would never have been a capacity without ideologies if there had not been a state behind it that allowed the European and world equilibrium to be threatened afterwards. | |||

In these second type wars, discrimination between civilians and military personnel is no longer necessary. With the Second World War, the number of civilian casualties was much higher than in previous wars. We come back to the State, of course, the industrial means at the service of war must be important. Organizing genocide requires industrial resources. In order to be able to mount such powerful armies, which will be confronted in the First World War for example, it is necessary to have large industrial capacities. The war helps to develop these industrial capacities. There's always this connection between the two. | |||

There is this period from 1789 onwards when these wars of the second type, which are total wars in which the entire population is involved and which affect the whole of society, will develop. On the periodization, we must be careful, because between 1815 and 1914, there is what has been called the "peace of a hundred years". A hundred years ago, there was no major conflict on European territory. As much as there was the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 after the Thirty Years' War, after the Napoleonic Wars, there was the Vienna Congress creating the "Concert of Nations". All the winners of the coalition against Napoleon defined new rules concerning this international system, which was called the Concert des Nations, which started to set up, if not a system of collective security, of concertation for the management of disputes between States, and which worked relatively well since there were fewer wars because it was in the logic of Concert des Nations. | |||

== | == After 1945 == | ||

As much as there was a hundred years of peace between 1815 and 1914, so much after 1945, the European continent experienced an extremely peaceful period. It is rather paradoxical because there was the Cold War, there was a constant threat of nuclear Armageddon, but there was no war. It is a relatively quiet period, especially as Europe was emerging from a very long and extremely violent period. We are witnessing the end of the war between the great powers after 1945. There is a decrease in the war and a long peace is being established. | |||

[[File:United Nations General Assembly Hall (3).jpg|thumb|left|267px|United Nations General Assembly hall.]] | [[File:United Nations General Assembly Hall (3).jpg|thumb|left|267px|United Nations General Assembly hall.]] | ||

Even if it is a Eurocentric conception of war, because as much as the Cold War in Europe did not give rise to violence in terms of war, but there are many wars that were conducted by proxy leading to violence. This European conception of war led to the end of direct confrontations between the great powers, whereas before, the problem was that the great powers of the time were making war against each other. The great powers no longer fight each other. | |||

More and more, we are coming to the idea of outlawing war. It is an idea that has been around for some time because in the idea of regulating war, there is also the idea that war must eventually disappear. The pacifist idea has long been embodied, in particular, in Emmanuel Kant's "perpetual peace" project, which proposes a number of steps to arrive at a certain federation of the system in which we will no longer have to go to war because states will become parliamentary democratic regimes that by definition do not wage war between themselves. But above all, after 1945, collective security mechanisms were finally put in place; that is, to manage relations between States effectively and avoid war. | |||

The idea of the emergence of the United Nations, for example, which, in its charter, provides for only two ways of carrying out war, namely that it prohibits war except in self-defence or unless a State endangers international peace and stability, and therefore the UN Security Council, through its chapter VII, authorises this war. There is an attempt to regulate the war, but by outlawing it, there is an attempt to make it disappear. From 1945 onwards, these trends became increasingly important. | |||

= | = The Contemporary Transformations of War = | ||

The emergence of modern warfare leads us to 1989, the end of the Cold War. As much so, we have seen that until now, that the emergence and constitution of modern warfare is related to the emergence of the constitution of the modern state, that the two are intimately linked, as from 1989 onwards, many researchers have the impression that we are facing a rupture; that a system that was built for some time is changing with the end of the Cold War. War is transforming itself, all the rules that were put in place would no longer be valid, new wars and even postmodern wars would happen. We would have been for more than twenty years in a transformation of war. We will see where we stand in relation to the fact that war would be transforming itself. | |||

== | == The new (dis)order of the world?! == | ||

{{Article détaillé|L’ONU et la sécurité internationale : 1945 – 2013}} | {{Article détaillé|L’ONU et la sécurité internationale : 1945 – 2013}} | ||

From 1989 onwards, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the disappearance of the Soviet Empire and the end of the bipolar system where relations between the Soviet and American blocs were regulated by the fear of mutual destruction creating a certain peace. The 1990s saw the beginning of an interesting period in which cards began to be redistributed. There is both the idea that we are entering a new world order with the idea that the United States is the only superpower, but above all that we are coming to a peaceful period in which the United Nations will finally be able to play its role and make it possible to outlaw war, since the United Nations was intended to ensure world peace and security, so it will now be possible to return to a fairly optimistic period. It is a time when most of the problems could potentially be solved by sending peacekeepers and from there, we would enter into a positive aid reaping the peace dividends of the end of the Cold War. | |||

At the same time, there are also elements and a discourse on what will be called the world disorder. Samuel Huntington's most famous thesis is that of Samuel Huntington and his book Shock of Civilizations arguing that we would no longer be in a logic of blocks fighting each other, but of civilizations. It was extremely influential and a lot of people think like that today, but it is especially because the end of bipolarity after 1989 gives a feeling that we are entering a new world and especially because there is a multiplication of civil wars. Until then, one of the aims of the codification of warfare and state constitution is that the majority of wars were inter-state wars between states; civil war was a minority mode of warfare because organized violence mainly passed through the state. | |||

From 1989 onwards, the trend was reversed with civil wars taking over. There is the impression that States are no longer the main actors in the war and that there is a return of inter-State violence. Actors such as terrorists, militias, mafias and gangs are back in the spotlight. These patterns of violence were allegedly domesticated by the state. The most important element is that as much sovereignty has been important in order to structure the inter-state system, so much from that moment onwards is called into question sovereignty and its ability to regulate violence. All the civil wars that we see mainly in Africa from the 1990s onwards are wars that involve so-called failed states. They are States that may be sovereign, but they are no longer able to exercise their authority over their territory, and since it is chaos on their territory, it becomes wars and destabilizes everything. | |||

From that moment onwards, sovereignty is increasingly viewed as something potentially negative through the multiplication of these infra-state conflicts or civil wars. | |||

== | == The New Wars == | ||

{{Article détaillé|Guerre, paix et politique en Afrique depuis la fin de la Guerre froide}} | {{Article détaillé|Guerre, paix et politique en Afrique depuis la fin de la Guerre froide}} | ||

The new wars according to Mary Kaldor in her ''New and Old Wars: Organised violence in a global era'', published in 1999, stand out from the old wars. | |||

Kaldor argues that from 1989 onwards, we are entering a new era that could be defined in three different ways. According to her, identities have replaced ideas. Above all, there are a lot of ethnic conflicts, for example, we no longer fight for ideas, but for an ethnic group for example, which, unlike us, places us in a position of exclusion. When one struggles for an ideological goal, one is in a much more inclusive disposition, such as fighting for international socialism, whereas from now on, fighting for an ethnic identity necessarily means excluding the other. | |||

[[File:Death of Pablo Escobar.jpg|thumb|right|Members of Colonel Hugo Martínez's Search Bloc celebrate over Pablo Escobar's body on December 2, 1993. His death ended a fifteen-month search effort that cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and involved coordination between the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command, the Drug Enforcement Administration, Colombian Police, and the vigilante group Los Pepes.]] | On the other hand, according to Kaldor, war is no longer for the people, but against the people, that is to say, we are increasingly faced with actors who do not represent the State and who do not even aspire to be the State. There is increasingly a war of bandits where the objective is to extract natural resources from countries for the personal enrichment of certain groups. Moreover, we are entering a war economy that is supported by transnational networks such as the mafias, meaning that we are entering global networks that feed these wars.[[File:Death of Pablo Escobar.jpg|thumb|right|Members of Colonel Hugo Martínez's Search Bloc celebrate over Pablo Escobar's body on December 2, 1993. His death ended a fifteen-month search effort that cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and involved coordination between the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command, the Drug Enforcement Administration, Colombian Police, and the vigilante group Los Pepes.]] | ||

Kaldor a | Kaldor has a depoliticizing approach to war. It took some time to think about a system in which warfare was eminently political, namely at the service of politics, in pursuit of political objectives, and according to this type of approach it is no longer the case. We are faced with states in the south resulting from decolonization that have been poorly constructed, that have not been given the tools to build themselves properly, and that are being torn apart, and which, in disintegrating, liberate a kind of general chaos in which ethnic groups are fighting each other, where bandits take advantage of everyone and nothing is going on because there is no state to bring order. | ||

There are criteria for this approach proposed by Mary Kaldor saying that there would no longer be political conflicts, but it is a thesis that has had some impact because it is consistent with the idea of global disorder, which is a feeling that once there are too weak states, we lose all control. As long as the state is not there to guarantee the stability of the territory it must control, this frees up a whole series of threats and dangerous things. With the disorder in the Middle East, this generates anxiety that is typically linked to the relationship with the state. Since it seems as if no one has any more control, it will release a whole series of potentially dangerous threats. Our relationship with the international system is clearly linked to the state. From the moment the state collapses, there is a fear that by no longer controlling what is happening within the states, this poses a danger. The fact that there is support for dictatorships in certain countries, over and above the fact that it is reprehensible as an approach, means above all that we prefer a state that controls what is in a country even if it is not democratic when we claim to be a democracy. There is an attachment to the state as a structure that allows us to think of our very global environment. | |||

From the moment the war is depoliticized, one enters a postmodern version of the war. We have talked about the new wars in the countries of the South, even though democracies are no longer supposed to fight each other, they still wage war; the countries of the North continue to wage war. | |||

== | == The Postmodern Warfare == | ||

{{Article détaillé|La transformation des pratiques contemporaines de sécurité : entre guerre et police globale ?}} | {{Article détaillé|La transformation des pratiques contemporaines de sécurité : entre guerre et police globale ?}} | ||

[[File:MQ-9 Reaper taxis.jpg|thumb|MQ-9 Reaper taxiing.]] | [[File:MQ-9 Reaper taxis.jpg|thumb|MQ-9 Reaper taxiing.]] | ||

Have these wars really changed the way they are conducted in Western countries? We would have entered a "western way of war", there is a return to technology, armies that are becoming more and more professional because Western populations are increasingly allergic to risk. Today, people are becoming less sympathetic to the idea of dying abroad. There are ways of waging more and more technological warfare that are moving away from the ground thanks to technological developments linked to the state in part. This is for example the image of the drone where we are going to give death remotely, i. e. the person who is going to give death is no longer in an airplane above the ground, it is several thousand kilometres away. The question is whether this distance-building changes the nature of war, is it an evolution, a revolution in military affairs with the concept of "zero death" war, must we overcome Clausewitz when we speak of Mary Kaldor for example? Is war really transforming itself, is it something that is becoming increasingly de-politicised in the countries of the South and is it something that is, at the end of the day, eminently technological, where there is no longer any connection with what is happening on the ground, we are no longer affected by war, and it is something technical with which we have really distanced ourselves? We talk about all these wars that we see on the screens with, for example, the Gulf War in the 1990s, which seems remote because we no longer even experience it through our families or our own experiences. | |||

= Annexes = | = Annexes = | ||

Version du 10 février 2018 à 23:18

We will first ask ourselves what war is, then we will ask ourselves about the birth of modern warfare, and we will see that war is a phenomenon that goes far beyond violence, but that is a regulating principle of our international system as it was built centuries ago. Then we will look at the current transformations, in particular how in the age of terrorism and globalisation, is war changing and are its principles changing? Finally, we will ask ourselves whether we are at the end of the war or whether it is still going on.

What is war?

Definition of war

We are going to ask ourselves what war is and go back to warnings and misconceptions about what war is. There are many definitions of what war is, but one of the most relevant is that of Hedley Bull, who founded the English school which, in his bookThe Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics publié en 1977, gives the following definition : « an organized violence carried on by political units against each other ».

This definition has many important elements. It is important to say that war is violence organised by political units among themselves. While the idea of war is fraught with preconceptions and violence, we must be careful because when we talk about war, we do not speak of interpersonal violence. Interpersonal violence is violence linked to crime and aggression, while war is organised violence involving organised political units fighting each other.

On the other hand, Hedley Bull adds that war has an official character, i. e. that war is waged in the name of the State against another political unit. This is where he makes a third distinction in his definition, which is that even if war is waged on behalf of that political entity, it must be waged against other political entities that are generally outside the state. Hedley Bull makes a fundamental distinction when it comes to organised violence, which is that of the fight against crime, for example when it comes to police work.

War is therefore organized violence between political units among themselves, and the whole being of an official character directed in general outside these political units. This definition is quite comprehensive and reflects how modern warfare was formed and, above all, how it is understood and understood in its study of most people who study war, whether it is in military academies, and it cuts across almost everything that is meant by "war".

Two ideas accepted

We will start with two preconceived ideas of war. War is a concept, a concept that we all know a little intuitively.

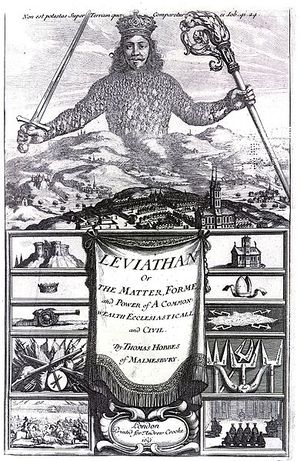

For Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan published in 1551, war is "the war of all against all. Hobbes is the basis of state and war theory, and his idea is that the state was formed because anarchy reigns between individuals, and an entity is needed to regulate interindividual relations. In other words, in a more sociological approach, the idea of warfare of all against all is an idea that has made it possible to develop other concepts is that the state has emerged to regulate the jungle that reigned within society, and the war of all against all is an empirical impossibility, because men cannot permanently fight anarchically, individuals are reluctant to organize themselves and to fight. There may be individual aggression, there may be selfishness that can lead to fights, but armed conflicts are something else. War, according to Hobbes, is something that is first and foremost a matter of human nature. Here, the idea of war against all is to be questioned because it starts from the idea that it is the selfishness of Man that generates war, whereas in fact it is the sociality of Man because we are forced to live in society, because in order to be able to wage a war, we need structures that make it possible to do so, namely an organisation. Human organization is the fruit of a human society. This principle stated by Hobbes starts from the fact that man is selfish and leads war all the time, but it is the society of man that creates war, since it takes an organization to make war, an organization that can only appear through society. Rather than being a natural and universal phenomenon, war is above all a social phenomenon. It is a reasoning which does not start from the selfishness of Man, but from his sociality which is the fact of living together and having to live together. To wage war requires complex organizations with bureaucratized administrations. There is a need for effective organizations that make it possible to wage war, hence the unavoidable preconditions for the organization of human societies in order to wage war.

We have just seen how to make war and make it possible, now we are going, with the second preconceived idea, to be interested in the "when". The second preconceived idea is that of Heraclite's perpetual war which postulates that "War is the father of all things, and of all things it is king". If it is assumed that war is a matter of human nature then it has always existed, this is not true. If we look at it a little more sociologically, one could say that war is a relatively recent phenomenon in human history, it is certainly a characteristic that is not timeless. There is no archaeological evidence of a sustained form of organized violence that means that warfare requires some degree of organization. Before the Neolithic Revolution of about 7000 B. C., we cannot really speak of war. If we assume that mankind appeared 200,000 years ago, war would only affect 5% of our history. We are far from an anhistorical and universal phenomenon that would have always existed. It is important to avoid essentializing war as something that would be in us. If we look empirically, the facts, war has not always existed and it is linked to a developed social organization. This form of social organization appears from the Neolithic period onwards and coincides with a functional specialization, namely the appearance of the first cities. The city is a place to specialize, unlike the countryside where everyone is more dependent. In a city, tasks are divided in order to be more efficient. It is an idea that is quite fundamental to the very idea of state building and the development of our societies. The idea of specialization is important in the social sciences; for example, the police officer is someone who specializes in violence. The underlying idea is that, for example, to plough your fields quietly, you need someone who takes care of security and whose job it is and in exchange, you will feed him. This is how we create a more specialized company and we are nowadays in extremely specialized companies.

In other words, the arrival of war coincides with the Neolithic Revolution, functional specialization and the emergence of cities. It is from the year 5000 BC that wars between these city-states began to appear. Then, from that moment onwards, increasingly complex societies develop.

The phalange: "father" of modern forms of organized violence?

When one goes back to classical antiquity until the Roman Empire, the war goes through a qualitative leap linked to a higher degree of organization. Qualitative leaps "require more effective systems to lead the war. There is a technological dimension.

One of the best examples is the Phalanx, which are heavily armed and well-organized infantry formations whose aim is to reduce and defeat the enemy at the time of the shock. This was used a lot in ancient Greece especially with Alexander the Great. This way of waging war accompanies the complexity of societies. From there, there is a development towards a way of conducting warfare that is more and more technologically developed and effective.

There is a parenthesis with the Middle Ages. With the fall of the Roman Empire, we return to more erratic modes of warfare with looting wars and less organized wars. From the 15th century onwards, the modern conception of war emerged and was therefore linked to a technological revolution. The development of modern warfare is linked to the development of the modern state. The two are inseparable.

War and Political Modernity

War is not the father of everything and something universal and natural, but it is a relatively recent phenomenon on the scale of humanity, but it is above all linked to the development of a high degree of social organization that begins in 5000 BC and goes back to the 17th century. The history of war is also the history of the state.

Talking about war in relation to the state is an articulation that is rarely used, but which is fundamental to understanding the form of organized violence that is war and therefore to see war as a phenomenon that is eminently linked to political modernity and therefore to the advent of the modern state. The State is not the only form of political organization in the world and especially not in history. There have been empires, city-states or colonies in the sense that the state is a relatively new form of organization in history.

If we take the angle of war as something fundamentally linked to the emergence of the state, it also allows us to go back to a third preconceived idea which is the idea that the state is perceived with a rather positive dimension. The State is the law and order, the basis of international relations is a division of disciplinary work and within the State which is policed and therefore in peace, the State guarantees this notably through its police and judicial system; Beyond its borders, it is anarchy, there is no international system similar to a clean government, and that is why we are fighting outside the borders of the state. It is a division of labour and the State enforces law and order within its territory. There is a positive dimension to peace.

The State is also the actor that will enable international peace, particularly through its participation of international organizations. In this conception of war, and especially in the relationship with the violence of the State, there is a positive dimension, since the State is what makes it possible to maintain order, not to sink into chaos and anarchy and therefore violence is perceived as something primitive and of another age. The state, by imposing itself, has made it possible to avoid chaos. If we compare it to other places in the world where there is a much more dramatic situation in terms of violence, it may be explained by the fact that there is no effective state on the ground that allows everyone to have a calm, orderly and safe life.

It is also necessary to question this idea because political modernity with the emergence of the State also sees the emergence of new forms of violence which have been developed and which have little to envy with forms of primitive violence. They are forms of violence linked to modernity such as genocide, which is a form of violence that is eminently linked to the development of a modern and industrial state. In order to organize a massacre on a large scale, we need large capacities. Total war is also a deadly mode of warfare with the First and Second World Wars. Ultimately, this modernity of the state and this conception of modernity leads to a twentieth century that was the most violent century of all time. In the twentieth century, in terms of political violence, there were more than 200 million deaths, of which between 130 and 140 million were directly related to the war. The difference is that political violence can be, for example, that of a repressive regime within a state. These figures are enormous, there is this paradox where the modern state is supposed to offer peace and stability within its borders, but the period has culminated in a time when there have never been so many deaths due to political violence. It's pretty paradoxical.

The birth of modern warfare

A state affair: War-Making/State-Making

In order to study war, one must first of all focus on its links with the modern state as a political organization. We will see how war is today through and through the emergence of the modern state. We will start by seeing that war is a state matter. In order to introduce the idea that war is linked to the very construction of the state and the emergence of the state as a form of political organization in Europe from the end of the Middle Ages, for this reason, the best way to do so is as brought about by the sociohistorian Charles Tilly in his article War Making and State Making as Organized Crime which developed the idea of war making/state making: the state and vice versa.

Tilly reports on the western trajectory of state building. When we talk about the modern state and the role of war, we are really talking about its emergence in Europe from the end of the Middle Ages onwards. That is to say, there are other forms of political entities in the world that follow different trajectories and if the European trajectory seems so important today, it is true that, particularly through colonisation, where today through the construction of the state or nation building, we are trying to export the European model because we assume that it is the only model that could be imposed on others. It creates some friction sometimes.

Through the idea of war making/state making, Tilly will translate that it is a process that takes several hundred years, but is not an intentional process. It describes the process of war making/state making through two operations that are two related competitions or phenomena.

First of all, the time of the exit of the Middle Ages coincided with an internal competition within the kingdoms between the lords. This happens at the time of feudalism when there was a king and different lords who had their fiefdoms in some form of allegiance to the king, but who were completely autonomous in the management of their affairs. The only connection they had with royalty was often through the war. The king addressed these feudal lords to raise men for war. Over several centuries, according to Tilly, there is an increasing competition between these lords because everyone wants to enlarge their territory. The Middle Ages is like a generalized "state of war" where everyone tries to enlarge their territory; both within what is beginning to become a state and outside with these entities.

Using Norbert Elias's idea, he spoke of a "elimination struggle". That is to say, there is less and less fighting. With the example of France under Louis XI in the XVth century, we can clearly see this logic which is put in place where we see in "blue" the territories that belong to the State, thus belonging to the King with a process of construction of the State well advanced which begins already two centuries before where the territories of the King of France were much smaller. More and more, through marriages, wars, successions and the disappearance of families, there is a tendency to have less and less territory and more and more one that will prevail. Internally, states have emerged in this form in most European countries. Often, the most emblematic cases are those of France and Great Britain.

In addition to the internal competition, there is an external competition. For example, in the time of Louis XI, he began to wage more and more wars abroad, and in order to be able to wage these wars, he needed resources, but also to reunify the Christian world. Since the Papacy has not been able to reunify the Christian world, these states each want to create what resembles these empires. These empires will not be created because they will all grow and meet and create a system called an international system. War as an institution of the "interstate system".

What we must remember from the idea of War-Making/ State-Making is that in order to be able to conduct these wars to continue to grow as an entity, it takes a lot of resources. To have the resources, we must have the means to extract these resources, and to fight wars, we need armies. This is where we see the link between resource extraction and the need to wage war, which will allow states to be built by the same phenomenon. In other words, in order to have an army that holds its own, it is necessary to have a population, to register, to maintain the army, it is necessary to have money, to have money, it is necessary to raise taxes, and in order to do so, it is necessary for people to know who lives where and to convince people of their legitimacy so that they can agree to pay without necessarily having to force them to pay taxes through violence. We are increasingly in the process of setting up efficient bureaucracies that extract resources from the territory in order to wage war. Constantly having to wage war requires increasingly efficient extraction of resources from a territory. It took several hundred years, but it is through this process according to Tilly that the born modern state is in the process of war.

Since the end of the Middle Ages, war has appeared as an institution that is at the base of an inter-state system that is at the base of a great impact on our daily lives. This idea comes from Europe at the end of the Middle Ages, which is the result of imperial pretensions and competitions between different states that started empires, some tried like Napoleon who wanted to build a territory that knew no borders and was an inclusive territory. But there is a sort of balance of forces that has been built up between all these powers in the long run. By eliminating each other, among all these powers, we have come to the emergence of a State whose strength was more or less equal in the long term, stabilizing around borders and meeting around those borders. From this, the idea of sovereignty emerges, that is to say, the idea of authority over the territory is divided into spaces where sovereignties are exercised and exclusive to each other. That is really the principle of an international system divided between sovereign states.

In the long term, a universalism of the national state which is not that of the Empire develops around the principle of sovereignty, since the principle of sovereignty is recognized by all as the organizing principle of the international system. That is the principle of the United Nations, for example, because it recognizes the principle of equality among all sovereign States. The idea of the United Nations stems from the idea of sovereignty as the organizer of the international system. This inter-state system, which is being set up, is organized around the idea that there is a logic of internal balance where the State administers a territory, i. e. the "police"; and external balance where the States regulate their affairs among themselves. It is this distinction of space that is fundamental here. There is an internal space which is the responsibility of the State which administers and administers the accounts of its citizens and the external space where the State has this mandate in order to manage the relationship with other States.

When all these states are trained, they have to communicate with each other. Since everyone has to survive as a state and there are other states out there, how are we going to communicate? If we assume that war is an institution, it is used to do just that. According to Vasquez, war is a learned mode of political decision-making in which two or more political units allocate material or symbolic goods on the basis of violent competition. In other words, war makes it possible to settle a competition; we do not agree, so we settle this through war. We move away from the idea of war as something anarchic or violent, war is something that has been developed in its modern conception to settle disputes between states, it is a mechanism for conflict resolution. It seems counter-intuitive.

First and foremost, war is to be understood as something that settles disputes. That is to say, if we disagree, we take resources, namely those armies, prepared by collecting taxes sent to fight against each other and from the moment one of them wins, the dispute is settled for the benefit of one or the other.

War can be seen from different angles, whether from a humanitarian point of view through the deaths they cause or from a legal point of view in relation to its regulation itself, and what are the legal stakes in the constitution of the various mechanisms for managing warfare. The angle of this course is political science to see where this phenomenon comes from and what it is used for. We are not interested here in the normative dimension of war.

We come to the idea that war is a mechanism for conflict resolution and that, if the strategy to an end, the end and purpose of this strategy is peace. The two are linked; we are in a conception where peace is intimately linked to war and, above all, the definition of peace is intimately linked to war. Peace is understood as the absence of war. It is interesting to see how the goal of the strategy is to win and return to a state of peace. It is the war that really determines this state. There is a very strong dialectic between the two. We are interested in the relationship between war and state, but also between war and peace. It's a relationship that is fundamental and it's a relationship that we're not going to be interested in today.

We are talking about peace, because what is important is that in the conception of war, which is taking shape with the emergence of this inter-state system, that is to say with states which are formed within and compete with each other outside, war is not a goal in itself, the goal is not the conduct of war itself, but peace; we go to war to get something. This is Raymon Aron's design.

To focus on the conception of war as a conflict resolution mechanism that allows us to do things, to obtain things, to "strategize" our objectives.

Carl von Clausewitz (1780 – 1832)

If one speaks of war, in his figure of theorization which is the most famous is Carl von Clausewitz who is a Prussian officer who exercised during the Napoleonic wars to write the book On War. Clausewitz will, if not fixed, be considered as the reference in the theorizing of war. It will pose an eminently political conception of war, which still remains a reference today.

Clausewitz defines war as an act of violence intended to compel the opponent to carry out our will. It is a very rational framework, it is not a logic of "war madman". War is waged in order to obtain something. According to Clausewitz,"War is the continuation of politics by other means. Imagine a state that is a government with an objective that is for example that of extending fertile lands, then the neighbour's lands have become an objective. Since he will not give them away, war will be declared to him, if the warring state wins, he will make a peace treaty and get the land. It is an eminently political conception of war in the sense that war is subordinate to politics. It is politics that determines what can be achieved through war because it cannot be achieved by other means, such as diplomacy or trade. There is a time when you can't get it otherwise, so you go to war in order to get it. This involves returning to normalcy, which is a state of peace.

The Westphalian system

From the 17th century and the end of the Thirty Years' War, the Westphalian system was established. Alongside the construction of the modern state, there is a whole thought in political theory in order to think about war, but also to codify it. A Dutch jurist, Hugo de Groot says Grotius, who from the 17th century onwards codified war, in terms of what could be done before the war, during the war and after the war that led to the codification of the law, but also the Geneva Conventions. The emergence of war in the inter-state system is accompanied by a desire to introduce very specific rules for the conduct of war: war must be declared, war is a moment of intense and extremely violent violence, but it is extremely well regulated. We must bear in mind all the efforts that have been made since then, it has been regulated and set rules that allow the war to be waged and used for this political purpose. In other words, war really is part of this inter-state system.

The Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 includes the Treaty of Osnabrück and the Treaty of Münster. They marked the end of the Thirty Years' War from 1618 to 1648, a reference to the religious war on the European continent between Catholics and Protestants, and at the end of these wars, a treaty was reached which enshrined the existence and emergence of the State as the basis for the system of organization between the entities and political units on the European continent, giving rise to the Westphalian system. The first references in Switzerland's official documents are to the Treaty of Westphalia, even though Switzerland as a state took some time to emerge in its modern form. It is the moment when the State is established as the basis of this system and, above all, the sovereignty is recognized, which is the fact that each State exercises on its territory the organizing principle of this system. We are not in an imperial logic, but in a logic where each entity exercises sovereignty over a given territory. Everyone recognizes that everyone does what they want to do at home, but when there is a dispute, war remains a means of settling it.

It is important to understand this distinction of space between an inner space where the rules are clear, where it is the State as such that has sovereignty to exercise power, which is recognized; and there is outside the State where there is no authority in the form of sovereignty. Even today, there is no world government, we are not in an empire of states, the territories of the planet being divided into states where there are about 200 sovereignties exercised exclusively. It is a principle, there are States stronger than others that impose their will, but as a principle of law and the organization of the system, it is from there that everything is put in place and still today, they occupy an extremely important place even if today we speak of non-state actors such as multinational corporations or non-governmental organizations that are of some importance and have a rather important role. The State is still at the base of what is called the "international system".

We are not talking about "global studies" or "global studies". The term "international relations", which means thinking about the world is to think beyond the borders of the state to show how important the moment of structuring space between states is.

The Treaty of Westphalia enshrines sovereign equality as the organizing principle of the international system and enshrines the principle that everyone does what he or she wants at home and that when a dispute arises, war is fought.

Towards Total War

From the seventeenth century onwards, there was a system in place that was accompanied and accompanied by the constitution of the role of the State; at the same time, these two processes were concomitant, took place simultaneously and influenced each other. From there, through the structuring of this system, with more and more powerful states, which industrialize and manage to extract more and more resources, to become more and more efficient, making it possible to go towards total war.

We enter this paradox where states that are increasingly effective in their internal management are reducing interpersonal violence, but paradoxically, there are wars that are extremely deadly if not more and more lethal. That is to say, if we make a distinction in the evolution of warfare, we have gone from a war in the Middle Ages where things are less clear at the level of the international system, where there is no discrimination between civilians and combatants, i. e. when the war is going to be codified, it will clarify the role of combatants and try to exclude civilians from conflicts. It will work because from the seventeenth century onwards, there will be fewer and fewer civilians involved in wars, and it will cause fewer and fewer civilian casualties in wars, the majority of which are military, and this is a phenomenon that will last until the end of the Cold War, when this figure is again reversed.

It is important to speak of war in relation to the emergence of the state because in the Middle Ages, these are more states of violence than wars in which there are different types of political units with city-states, the papacy, warlords who change affiliation according to their interests of the moment, it is much more fluid, there are different forces that fight since modern warfare is linked to the emergence. Whereas in the Middle Ages, there was a mixture, the statutes were much less clear, there were different types of actors, and there were not only agents of the State who fought each other.

Limited/institutionalized/trinitarian wars (of the "first type" according to Holsti): 1648 -1789

From the peace of Westphalia, where war was established as a means of regulating violence between all the entities that make up the Westphalian system, wars became institutionalized.

Since the Treaty of Westphalia, wars have become institutionalized. In The State, War and the State of War, published in 2001, Holsti makes a well-known distinction between the different types of warfare, often referring to first type warfare at the end of the Middle Ages. Between 1648 and 1789, we are talking about wars that are relatively short, lasting from one to two years, with quite clear sequencing, so with a declaration of war, a ceasefire, a peace treaty; the war is increasingly codified and everyone is playing the game more and more with limited objectives, limited interests being in a Clausewitzian conception.

It is also a time of codification where there are no longer any roles that are not well established, there are uniforms, codes of conduct that are being put in place, but also a military tradition around the "nobility of the sword" that is also being put in place, this is where the armies of Western states as we still know them today are born. These are wars that are limited in time and space, there are clear objectives and it is a maneuver war rather than annihilation.

The army is used to get things decided in advance. However, there were still a lot of wars at the time. We are not talking about peace or outlawing war, but it is an effort to codify this war in which civilians are a little more spared and the number of victims is relatively limited.

The symptomatic war of the time and the Spanish War of Succession where there are a series of brutal conflicts at the time, but limited in time between different European states. It is therefore a time when armies are codified, uniforms are emerging, and we distinguish ourselves through uniforms. This distinction is important because States are also shouting at each other about the fact that we also differentiate ourselves according to uniforms.

The Second Type War or Total War: 1789 - 1815 and 1914 - 1945

By remaining on the typology of Holsti, we enter the second type wars. From 1789 and the French Revolution onwards, revolutionary wars began and the novelty, which remained extremely linked to the construction of the State, was entered into mass levees with the concept of "Nation en armes".

With the French Revolution, the European princes joined forces to invade France, and the revolutionary reaction was set up with the mass raising and the establishment of a conscription army. Beyond the poetic side of the revolution, this implies that it is above all a relatively modern state that can afford conscription leading to military service, which is the fact that we can mobilize huge numbers of people quickly, arm them, train them and send them into combat. As such, a much less developed state is needed to hire a few hundred mercenaries and send them to fight. Setting up an entire army is much more complicated than simply buying a service. The development of these conscription armies made it possible to raise huge armies in terms of men, size and efficiency. Second type wars are the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars after which they are nationalist armies, meaning that they are no longer professional armies as was often the case before, based on mercenarism. The paradox with the beauty of the revolutionary cause, where it is a people who rise up against an enemy who attacks our ideals, but when a revolutionary war is waged, the goal is not just to gain a few square kilometers, the goal is to annihilate the enemy because it challenges our existence. We enter into much more lethal logics with the second type of wars, which are linked to the revolutionary wars of the time. The objectives become unlimited, unclear and are not concrete like the concepts of "liberation","democracy","class struggle" and imply unconditional surrender.

The Second World War is symptomatic of this phenomenon because with the struggle against Nazism, we are not in a logic of capitulation where everyone stays at home afterward; when one enters this type of war, one enters a logic of unconditional capitulation, the objective is to annihilate one's enemy. It is a transformation of war, but it is eminently linked to state building. In order to arrive at something like the Second World War with a fight against Nazism, in order for Nazism to emerge, it took a state to develop, otherwise there would never have been a capacity without ideologies if there had not been a state behind it that allowed the European and world equilibrium to be threatened afterwards.

In these second type wars, discrimination between civilians and military personnel is no longer necessary. With the Second World War, the number of civilian casualties was much higher than in previous wars. We come back to the State, of course, the industrial means at the service of war must be important. Organizing genocide requires industrial resources. In order to be able to mount such powerful armies, which will be confronted in the First World War for example, it is necessary to have large industrial capacities. The war helps to develop these industrial capacities. There's always this connection between the two.

There is this period from 1789 onwards when these wars of the second type, which are total wars in which the entire population is involved and which affect the whole of society, will develop. On the periodization, we must be careful, because between 1815 and 1914, there is what has been called the "peace of a hundred years". A hundred years ago, there was no major conflict on European territory. As much as there was the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 after the Thirty Years' War, after the Napoleonic Wars, there was the Vienna Congress creating the "Concert of Nations". All the winners of the coalition against Napoleon defined new rules concerning this international system, which was called the Concert des Nations, which started to set up, if not a system of collective security, of concertation for the management of disputes between States, and which worked relatively well since there were fewer wars because it was in the logic of Concert des Nations.

After 1945

As much as there was a hundred years of peace between 1815 and 1914, so much after 1945, the European continent experienced an extremely peaceful period. It is rather paradoxical because there was the Cold War, there was a constant threat of nuclear Armageddon, but there was no war. It is a relatively quiet period, especially as Europe was emerging from a very long and extremely violent period. We are witnessing the end of the war between the great powers after 1945. There is a decrease in the war and a long peace is being established.

Even if it is a Eurocentric conception of war, because as much as the Cold War in Europe did not give rise to violence in terms of war, but there are many wars that were conducted by proxy leading to violence. This European conception of war led to the end of direct confrontations between the great powers, whereas before, the problem was that the great powers of the time were making war against each other. The great powers no longer fight each other.

More and more, we are coming to the idea of outlawing war. It is an idea that has been around for some time because in the idea of regulating war, there is also the idea that war must eventually disappear. The pacifist idea has long been embodied, in particular, in Emmanuel Kant's "perpetual peace" project, which proposes a number of steps to arrive at a certain federation of the system in which we will no longer have to go to war because states will become parliamentary democratic regimes that by definition do not wage war between themselves. But above all, after 1945, collective security mechanisms were finally put in place; that is, to manage relations between States effectively and avoid war.

The idea of the emergence of the United Nations, for example, which, in its charter, provides for only two ways of carrying out war, namely that it prohibits war except in self-defence or unless a State endangers international peace and stability, and therefore the UN Security Council, through its chapter VII, authorises this war. There is an attempt to regulate the war, but by outlawing it, there is an attempt to make it disappear. From 1945 onwards, these trends became increasingly important.

The Contemporary Transformations of War