« The structural foundations of political behaviour » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 108 : | Ligne 108 : | ||

The results can be summarized in two parts. First, the manual working classes tended to support left-wing parties while the non-manual classes tended to support right-wing parties. This is now an outdated idea of class voting. The second element concerns the results; there are significant variations between countries. | The results can be summarized in two parts. First, the manual working classes tended to support left-wing parties while the non-manual classes tended to support right-wing parties. This is now an outdated idea of class voting. The second element concerns the results; there are significant variations between countries. | ||

=Impact | =Impact of class voting= | ||

How do we measure class and class voting? To sum up, in relation to class voting, there are three positions that largely or largely reflect the positions evoked in relation to the role of traditional cleavages : | |||

* | *some work shows a form of persistence, such as the fact that the class continues to structure voting behaviour; | ||

* | *there is the idea of class voting decline as a misalignment - the mismatch between political supply and political demand; | ||

* | *there is also the idea of transformation. The class cleavage is still important but it structures the vote differently. There would have been a realignment between social classes on the one hand and parties that represent class interests on the other. | ||

[[Fichier:comportement politique impact du vote de classe 1.png|vignette|Leduc, L., R. Niemi et P. Norris, éds. (1996). Comparing Democracies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.]] | [[Fichier:comportement politique impact du vote de classe 1.png|vignette|Leduc, L., R. Niemi et P. Norris, éds. (1996). Comparing Democracies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.]] | ||

Numerous figures abound in the direction of decline. With this graph, we are looking at the long term. Several figures appear from 1945 to 1995 for different countries showing that everywhere there has been a decline in class voting, at least since the end of the Second World War. This difference exists as much in the countries where the class vote is important. | |||

Third generation researchers criticize this type of representation for relying on an overly simplistic definition of both social class and class voting. It is as a result of the hyper-simplification of these two concepts that a decline is observed. These researchers say that if we redefine social class and the class vote, we can put the decline into perspective.[[Fichier:comportement politique impact du vote de classe 2.png|vignette|center|Leduc, L., R. Niemi et P. Norris, éds. (1996). Comparing Democracies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.]] | |||

This table shows the international variations. There is not only class voting but also all the other traditional Rokkan cleavages. The figures are correlation coefficients between social characteristics and party preferences. It is important to note that there is a great deal of variation, as the second generation has shown. | |||

For some researchers, the curves specifying class voting are based on Alford's index, that is, the percentage of the working class saying they preferred a left-wing party minus the percentage of the middle class voting for the left. This is a measure that has been used, specific and, according to some, too simplistic, hiding a much more complex reality, and if measured differently, different conclusions could be reached. | |||

=Définition et mesure des classes sociales= | =Définition et mesure des classes sociales= | ||

Version du 3 mai 2020 à 23:20

| Professeur(s) | Marco Giugni[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

|---|---|

| Cours | Political behaviour |

Lectures

- Political Behaviour: introductory course

- Political Behaviour: Historical and methodological benchmarks

- The structural foundations of political behaviour

- The Cultural Basis of Political Behaviour

- Political socialization

- The rational actor

- Political participation

- Theoretical models of voting behaviour

- Theories of social movements

The structural and cultural dimensions are strongly and intimately linked, but we will deal with them separately. However, it is difficult to make a clear distinction, this distinction is only analytical.

The structural bases of political behaviour refer to the notion of structure which is used in different disciplines, particularly in political science and psychology, but used with sometimes different connotations. Some speak of structures as a set of established rules that then define and influence behaviour. Others speak of structures more simply by saying that the structural aspects concern mainly the institutional aspects, i.e. the role of institutions as a structure that provides a framework for political action in particular. Others speak of structure by referring to the composition of the social system such as the role of social classes. More generally, with regard to the concept of structure, three main aspects should be retained, which are :

- the structure refers to the material bases of existence and the objective bases;

- there is the idea of a certain durability over time, a structure is not something that changes in the short term. A structure is not something that changes in the short term. A distinction is made between structural elements and conjunctural elements that can change in the shorter term ;

- the structure(s) are seen as something that influences or can influence action and in particular political action, i.e. political behaviour, voting behaviour, non-electoral behaviour, or involvement in social movements.

We are going to see what are the structural bases which, in the long term, can influence political behaviour.

The cleavages

The concept of cleavage is used by several sub-disciplines of political science and was proposed by Stein Rokkan. A cleavage is a term that is used in everyday language in newspapers and the media, including the "left-right" cleavage. In Switzerland, there is also talk of a divide between the French-speaking and German-speaking parts of the country. We will try to define this concept which can help us understand the idea of political behaviour.

From a scientific point of view, the cleavage has been defined according to two plus one main dimension. The notion of cleavage as formulated by Rokkan contained the first two aspects and other authors have proposed a third dimension with the political cleavage. Moreover, there are synonyms used in science or in common language, also called "division" or "social divide". The cleavage is to be understood as an element that captures the structural dimension and then influences behaviour:

- structural basis: social division - it is the objective existence of a social division, a fracture, an opposition of interests. Often, the notion of cleavage has been likened to the idea of conflict of interest. This cleavage may be based on several "dividing lines" in terms of class or ethnicity. In a general sense, it can be a division that separates two groups within a society. The idea that there is a structural basis or social component is not sufficient. A second component is still needed.

- identity base: collective identity - it is possible to call this component a cultural base or what can also be called the identity base. A cleavage must also be based on the existence of a common identity within the two opposing groups. There must be a sense of belonging in a cleavage. There is a subjective or cultural or even identity dimension to a cleavage. Some speak of a normative subjective component that "refers to the set of values and symbolic representations that shape identity, attitudes and the social actors involved". There needs to be a structural basis, but also that the groups that oppose this divide must also be able to identify with the group in question. For Rokkan, these are the two elements that mark a cleavage.

- organisational basis: politicisation - for others, something else is needed in order to speak of a political cleavage, the cleavage must be politicised by certain organisations which may be political parties but it may be other types of organisation with political parties, interest groups which do not enter into the game of electoral competition but defend certain interests which are strongly linked to belonging to a group in a cleavage. We can go from an institutionalized level with political parties or interest groups, and finally the organization of movements that is even more external to the system.

There are these three types of organization that form the organizational basis that contribute to the politicization of a political, social and cultural divide. Thus, for the organizational base, "the political organizational component implies the organization of the social division by institutions or organizations such as political parties, trade unions, interest groups or associations, social movements, etc.". ». A political cleavage exists insofar as these three dimensions are present at the same time. In other words, if there are the first two dimensions, we can speak of a social cleavage, but this cleavage remains latent and is only a potential or a potential for mobilization. When we speak of "mobilization", we generally speak of electoral and non-electoral mobilization. It is only when there is the organizational base that it is possible to speak of a political cleavage. Rokkan and Lipset have synthesized the cleavages in a cleavage theory. As far as politicization is concerned, we should mention the work of Bartolini and Mair in their book Identity, Competition, and Electoral Availability published in 2007 that emphasized the need for a politicization of the divide.[8]

Rokkan proposed a theory to explain why, as a result of the emergence of political parties in Europe, i.e. the formation of political systems in Europe, some voters vote for some parties and not for others. In other words, he formulated a theory of the social and structural bases of electoral behaviour in particular, but which can also be applied in theories on social movements. One of the theories of voting behaviour, namely the sociological model of the Columbia School, is implicitly or even largely based on the theory of cleavages.

Traditional cleavages

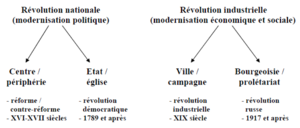

Rokkan formulated a theory of party formation based on two main processes. The basic idea is that society is changing, that European society has changed from the 15th and 16th centuries in particular, there have been several transformations and in particular two great transformations that he calls the "national revolution" on the one hand and the "industrial revolution" on the other. There is also talk of a "process of political modernization" and on the other hand of a "process of economic and social modernization".

The national revolution consists of two sub-processes which are the formation of the nation-state which still today, despite globalisation, changes still largely induce and structure political outputs at the world level. So, on the one hand, the process of formation of the nation-state is a process of centralization and secularization of the state, and on the other hand, the process of democratization with the birth of the concept of citizenship. Modernization could be reduced to these two processes. On the other hand, economic and social modernization takes place with the advent of capitalism and the industrial revolution.

These two great processes gave rise in Rokkan's theory of the four great cleavages that are the great divides in Europe from the 16th century onwards, which were responsible for the formation and which largely explain the formation of the different parties, in other words, they explain the political offer, at least as it was present at the time Rokkan wrote. Generally speaking, scientific work must be situated in the historical moment. Rokkan was writing in the 1960s. These four cleavages, these four fractures are the traditional cleavages, namely the centre-periphery cleavage, the state-church cleavage, the city-countryside cleavage and the class cleavage between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. For Rokkan the two cleavages are cultural cleavages; on the diagram we can see the interweaving of the structural dimension and the cultural dimension.

The center-periphery cleavage is the cleavage that represents the conflict between the centralizing culture or cultures that was that of the formation of the nation-state. The formation of the nation-state was the idea of centralizing in one sphere of power a system that was much more fragmented under the old regime. In other words, it is a centralist conflict of state formation and the growing resistance of ethnically, linguistically or religiously distinct populations. Religion plays a very important role in this first cleavage. This cleavage, like every cleavage, was based on the main issues, which were in particular religious issues of the control of religion or language.

The religious divide led to the emergence of Catholic parties in particular. There is also talk of a cleavage between the State and the Church in a process of modernization, but at a somewhat later point in history. According to Rokkan, each cleavage precedes the other in time. The main issue at stake is the control of public education. The State, at one point in its creation, wanted to take control of children's education. With national education, we are in an education that is not a religious education. Obviously, the church, which controlled education at that historical moment, was opposed to this loss of power.

The urban-rural and bourgeois-proletariat cleavages are cleavages that at one time were based on different modes of production. The city - countryside cleavage is the conflict between the interests of the land and the interests of the rising class which was the bourgeoisie. It is this opposition that has characterised much of European history. On the other hand, the class divide is the opposition between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, which opposed these two social classes, namely the owners, the means of production and capital.

Each cleavage corresponds to what Rokkan called a "critical juncture" which represents a kind of beginning of politicization of the cleavage. It is thanks to the politicization of these four cleavages that have succeeded one another in European history that we can explain in this perspective the structuring of political systems and thus the political offer that exists today. Supply is important because it is linked to political demand. There are conflicts between social groups with different interests.

This is Rokkan's fundamental idea and therefore the idea of the party system which is largely determined by this social division. There is an important additional element for the study of political behaviour which is the threshold idea that we have had to pass through European history. According to Rokkan, in order to understand how a social or socio-economic conflict, a cleavage with these first two social dimensions, turns into an opposition between parties, it is necessary to study the conditions for the expression of mobilization. It is also necessary to understand the representation of interests in each society which is the political representation of the cleavage. And therefore, it is necessary to understand, for example, how the traditions of decision-making in a political process can act. There are systems that are mainly based on the idea of consultation or negotiation between the different groups that oppose each other in this cleavage, as for example in Switzerland with the idea of "labour peace". There are other cleavages, traditions and countries that are in a dirigisme perspective. It is also necessary to understand, study and know the channels that exist or the expression of mobilization and protest. It is also necessary to understand the opportunities for benefit but also the costs of alliances, i.e. the costs and conditions for creating political alliances. It is also necessary to understand the possibilities and implications of majority rule in political systems, i.e. what are the chances of gaining power.

Impact of cleavages on the party system

All these conditions suggest a sequence of thresholds from Rokkan's perspective, in the path to be taken and that each movement must continue and move towards a new system of demand in a political system. These thresholds represent and explain what impacts the cleavages have on party systems. There are four thresholds that lead to full integration:

- legitimization: this threshold refers to mobilizations accepted by other political forces in the system. It is a weak threshold of integration or one that must be crossed in order to be a fully integrated political force. New movements emerge at a certain point and therefore these movements must first be considered as legitimate interlocutors or representatives of certain sets of interests. The question is to what extent a group that is part of a socio-cultural cleavage manages to acquire power to varying degrees. Dates and thresholds can be seen as thresholds through which a cleavage must pass in order to move from the social and cultural to the political dimension;

- incorporation: this is participation in the political process on the same level as opponents. The threshold of incorporation decides which groups, which movements within society have the right to participate in mobilizations in the political process;

- representation: these are the conditions of access to representative institutions, i.e. parliament. The threshold of representation determines how a group or movement can have access to representative institutions. It depends on a whole series of conditions, namely the electoral system or the conditions for the creation of alliances;

- majority: it is the power to make changes in the system. This threshold determines the institutional procedures by which a party, an alliance can obtain the power to make structural changes in the system. In other words, it is the threshold for being part of a government.

According to Rokkan, it is through these four stages that an objective and identity-based divide in society can become politicized, organized and empowered.

Rokkan and Lipset's theory of the party system in Party systems and voter alignments: cross-national perspectives published in 1967 is the idea that crossing these four thresholds influences the electoral market by conditioning the criteria for access to the electoral market. In particular, there is the idea that those who come first dictate the rules. That is why there is the idea of cumulation with the idea that those who are first legitimized and incorporated into the system, represented, or even acquire executive power can dictate the rules of the game and therefore dictate the conditions of access for new political parties or organizations. On the other hand, there is the idea that those who enter first create and forge political identities. That is, historically, the first parties that crossed these thresholds, for one reason or another, then mobilized an electorate and through the mobilization of this electorate created political identities. Once these political identities are created, according to Lipset and Rokkan, this political system is somehow frozen, i.e. it becomes difficult to change these identities and therefore it becomes very difficult to change the configuration of party systems. In the 1960s and 1970s, the party system largely reflected the configuration of social cleavages as it was made at the time of the Russian Revolution of the 1910s and 1920s. Today, in 2015, much has changed. There has been a process known as "globalization" which has probably muddied the waters with the emergence of new parties.

There is an important theory that emphasizes the role of social divisions and fractures in order to explain both the configuration of political supply, i.e. party systems, but also to explain voting behaviour in particular. This theory, which focuses on cleavages and their politicisation across different thresholds, also emphasises the fact that these political forces, which were precursors, were able to create political identities that are highly explanatory, particularly of voting behaviour. With Michigan's model, known as the psychological model or the "partisan identification model", to explain voting behaviour, even if these theorists do not explicitly link it to Rokkan's theory of cleavages, they emphasize the idea that there is an electorate that strongly identifies with an organization or a party that can explain why people vote for this or that party.

Potential for cleavage mobilization

Not all cleavages influence political behaviour in the same way. In other words, the potential for mobilizing the cleavages varies. Beyond any consideration of the historical, current and current cleavage, some of these cleavages are more mobilizing than others. There are many factors that can explain, but two elements that characterize the cleavages and that help to explain why these cleavages are more or less explanatory of voting behaviour but also of non-electoral behaviour. :

- degree of openness - segmentation, integration: a cleavage is also characterized by its degree of openness. Different cleavages can be more or less open or more or less closed. This is linked to the very definition of a cleavage referring to two dimensions which are on the one hand the segmentation of a cleavage and on the other hand integration. In other words, a cleavage, in this type of theory, is all the more mobilizing the more it is highly segmented, that is to say that the groups that make up this cleavage are strongly distinct objectively and subjectively insofar as they self-define themselves as being different from the other group. On the other hand, the degree of openness is characterized by the greater or lesser degree of integration within the opposing group. It is a cleavage that makes it possible to explain voting and other behaviours all the more so as the groups that are part of this cleavage are strongly distinct and different and by the fact that it is strongly integrated within them. The subjective dimension is important for the integration dimension because integration also depends on the creation of a strong collective identity within the group, hence the fact that collective identities have an impact on mobilization.

- degree of pacification - salience: this aspect is more related to the degree of politicization, which is the degree of salience or pacification. A cleavage is all the more mobilizing if it is not pacified or if it has not been pacified by institutional procedures such as "labour peace" in Switzerland, which is a form of pacification. The degree of pacification means that the conflict between the two components of a cleavage is reduced. The more a cleavage is pacified, the less prominent it is.

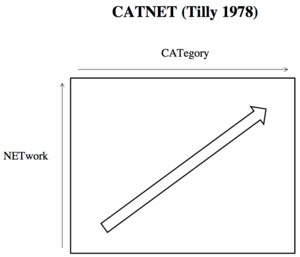

Some have conceptualized this in different ways, such as Charles Tilly who talked about CATNET in From Mobilization to Revolution published in 1978.[9][10] For Tilly, the potential of social movements to mobilize for collective action depends on two dimensions that have led to the formation of categories that are more or less defined, but also on the degree of networking within them, namely the difference between segmentation and integration. The arrow represents the development of the degree and intensity of the mobilizing potential of a cleavage according to the level and intensity of category and network.

The idea of degree of pacification is important because some authors have hypothesized that the space left for the emergence and mobilization of new cleavages, i.e. cleavages that are not one of the four traditional Rokkan cleavages, is inversely proportional to the degree of salience of the traditional cleavage. In other words, the more salient the traditional cleavages are, the less space there is for the emergence and political expression of new cleavages. The more traditional cleavages, particularly religious and class cleavages, have been pacified through informal or institutional procedures, the more space there is for the emergence of new cleavages. It is in this way, for example, that some have explained why the so-called "new social movements", which are movements that emerged after the 1970s with the new left, have been able to mobilize strongly in some countries more than in others. The idea is that they have been able to mobilize in countries where, precisely, the traditional cleavages have been pacified and therefore weakened, and political identities based on the traditional cleavage have also been weakened, leaving more room for new political groups to capture an electorate and mobilize groups and sectors of society. The notions of openness and pacification link Rokkan's macro-political theory of historical cleavages to what we want to explain, namely political behaviour.

Impact of cleavages on political behaviour

In relation to the idea of the extent to which the traditional cleavages highlighted by Rokkan, particularly religious and class cleavages, influence political behaviour, there are different positions in the literature.

A first position is that of Bartolini and Mair, which is to say that traditional cleavages continue to influence politics, even if not necessarily in the same way. We will see how some authors have tried to show how the class divide is still important today, showing that by transforming itself, it has been able to retain a certain importance in terms of explaining political behaviour that it would otherwise not have had.

The second position says that social divisions are less and less structuring individual electoral choices, this being due to the resolution of social conflicts represented by traditional cleavages. In other words, this is due to the pacification of traditional class cleavages in Europe and thanks to the pacification of religious cleavages that would be the result of secularisation processes. It should be stressed that this position does not point to the emergence of new cleavages. In other words, they admit a position of misalignment where electoral volatility, i.e. the passage of votes from one sector to another or from one party to another, is becoming increasingly important and frequent.

The third position is that traditional cleavages are weakening, but new ones are emerging such as the cleavage between materialist and post-materialist orientation or the cleavage between the winners and losers of globalization. These new cleavages, which were not conceptualized by Rokkan and which were not even present throughout European history until recently, have to some extent replaced or are increasingly replacing the traditional cleavages, and proof of this is the emergence of new parties that rely on new social movements outside the main axis of the traditional line. For those in this third position, this proves that traditional cleavages no longer explain political behaviour and that there are new cleavages that have replaced them.

The class vote

This leads us to talk about the transformation of cleavages and the emergence of new cleavages. The most studied cleavage in the literature is the class cleavage. The fourth cleavage according to Rokkan is based on the division crystallized in the critical moment represented by the revolutions of the beginning of the 20th century opposing the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

In the history of his analysis, three generations can be distinguished. A first generation is in the 1950s. Behaviourism, which is the study of individual voting behaviour, was born some time before this historical phase and therefore in the beginnings of the analysis of class votes. We wanted to put forward the idea that class membership is strongly explanatory of voting behaviour. Social position explains, indeed, determines electoral choices. The second generation, from the end of the 1960s, tried to introduce more explanatory variables. In statistical analysis, they tried to control for the effect that social position had on voting by taking many other aspects into account. This second generation will also start to look at variations and in particular international variations, i.e. social class is strongly explanatory in a certain context and much less in another context may also be because of the mobilizing potential of the class divide which results from the degree of openness or closure or even segmentation or integration and the degree of pacification. And finally the third generation, from the mid-1980s onwards, when there was a redefinition of social classes and class voting. These researchers had found that the conclusions and the theories on which the researchers of previous years had based their work were based on overly simplistic conceptualizations and definitions of both what a social class is and what class voting is and how it is measured.

The results can be summarized in two parts. First, the manual working classes tended to support left-wing parties while the non-manual classes tended to support right-wing parties. This is now an outdated idea of class voting. The second element concerns the results; there are significant variations between countries.

Impact of class voting

How do we measure class and class voting? To sum up, in relation to class voting, there are three positions that largely or largely reflect the positions evoked in relation to the role of traditional cleavages :

- some work shows a form of persistence, such as the fact that the class continues to structure voting behaviour;

- there is the idea of class voting decline as a misalignment - the mismatch between political supply and political demand;

- there is also the idea of transformation. The class cleavage is still important but it structures the vote differently. There would have been a realignment between social classes on the one hand and parties that represent class interests on the other.

Numerous figures abound in the direction of decline. With this graph, we are looking at the long term. Several figures appear from 1945 to 1995 for different countries showing that everywhere there has been a decline in class voting, at least since the end of the Second World War. This difference exists as much in the countries where the class vote is important.

Third generation researchers criticize this type of representation for relying on an overly simplistic definition of both social class and class voting. It is as a result of the hyper-simplification of these two concepts that a decline is observed. These researchers say that if we redefine social class and the class vote, we can put the decline into perspective.

This table shows the international variations. There is not only class voting but also all the other traditional Rokkan cleavages. The figures are correlation coefficients between social characteristics and party preferences. It is important to note that there is a great deal of variation, as the second generation has shown.

For some researchers, the curves specifying class voting are based on Alford's index, that is, the percentage of the working class saying they preferred a left-wing party minus the percentage of the middle class voting for the left. This is a measure that has been used, specific and, according to some, too simplistic, hiding a much more complex reality, and if measured differently, different conclusions could be reached.

Définition et mesure des classes sociales

On distingue deux approches, à savoir une approche que nous pouvons qualifier de « traditionnelle » se basant sur un schéma à deux classes avec d’une part les travailleurs manuels et d’autre part toutes les autres classes. Cette manière a été traditionnellement utilisée pour évaluer l’impact du vote de classe jusqu’aux années 1980. À un certain moment, certains chercheurs, notamment Erikson et Goldthorpe qui ont proposés un schéma de classe différent et beaucoup plus détaillé.

On part d’une distinction entre employeurs et employés mais on introduit aussi l’idée des indépendants et on rajoute des distinctions supplémentaires afin d’arriver à treize classes sociales différentes.

Ce schéma s’appui sur une premier distinction qui est ensuite développée à travers des sous-catégories un peu plus fines et correspondant à la réalité actuelle de notre société. La position de classe de base s’appuie sur la distinction binaire entre employeurs et employés, a été ajouté également la catégorie des indépendants. Cela constitue un premier niveau très général afin de distinguer entre plusieurs positions de classe et ce qui nous intéresse est de savoir comment les individus s’insèrent dans cette position de classe et le côté objectif du clivage social. Il y existe des distinctions supplémentaires. En ce qui concerne les employeurs, il y a une distinction entre la taille des entreprises et une autre distinction entre le secteur industriel et le secteur de l’agriculture. Cela donne quelques classes sociales avec une catégorisation des classes. En ce qui concerne les employés, Erikson et Goldthorpe ont fait la distinction entre les travailleurs qui s’appuient sur la contrainte du travail par opposition à une relation de service.

Il y a deux distinctions avec la première qui est entre employeurs, employés et indépendants, et la deuxième entre ceux qui s’appuient sur l’existence d’un contrat de travail. Par contre l’autre catégorie est basée sur des relations de services. Il y a d’autres sous-catégories qui sont moins intéressantes selon le niveau d’éducation.

Le résultat de ce type de schéma est quelque chose qui est beaucoup plus élaboré par rapport à la distinction traditionnelle entre classes manuelles et non-manuelles. C’est en fait un schéma qui détails 11 classes sociales différentes. Ce schéma peut être agrégé. Il est possible d’avoir des niveaux d’agrégation avec un regroupement.

Définition et mesure du vote de classe

On distingue deux approches afin de mesurer le vote de classe.

Une première approche est celle du vote absolu dont la mesure traditionnelle est l’index d’Alford, à savoir qu’on regarde la différence dans le soutien pour les partis de la gauche entre les classes manuelles et les autres. À partir de là, on regarde dans les deux groupes quelle est la proportion des personnes qui appartient à ces deux groupes et qui votent plutôt pour la gauche ou pour la droite. C’est un raisonnement binaire au niveau de la classe sociale et au niveau du vote. En d’autres termes, l’index d’Alford est la différence entre les occupations manuelles et non manuelles dans le soutien pour les partis de gauche.

Il n’y a pas d’unanimité afin de savoir si le vote de classe a diminué, donc est-ce que le rôle de clivage de classe a diminué ou pas. Ceux qui critiquent ce schéma à deux classes et l’index d’Alford, qui est binaire afin de calculer le vote de classe, s’appuient sur le schéma de classe de Thomson et l’index de Kappa. On appel cela le vote relatif. On s'appuie sur la probabilité que les citoyens qui appartiennent à l’une ou l’autre classe puisse voter pour la gauche ou un autre parti. La différence entre l’index de Thomson et l’index de Kappa se trouve dans le fait que l’index de Thomson garde l’idée binaire entre gauche et droite en regardant la proportion des membres des classes différentes à voter pour la gauche ou pour la droite. L’index de Kappa s’appuie sur l’index de Thomson mais il introduit une multidimensionnalité en regardant la probabilité que les membres de différentes classes sociales ont de voter pour un parti qu’un autre. On abandonne la distinction un peu grossière de voter pour la gauche ou pour la droite. Il y a l’idée implicite qu’il est difficile de faire la distinction aujourd’hui entre gauche et droite. Pour calculer l’index de Thomson, cela revient à faire une régression logistique binaire tandis que l'on effectue une régression multinomiale pour l’index de Kappa.

En fonction de la définition que l’on prend des classes et du vote de classe, le résultat peut changer drastiquement. Il y a ceux qui s’appuient sur une distinction traditionnelle avec une distinction binaire et l’index d’Alford et constatent un déclin, alors que ceux qui s’appuient sur l’index de Thomson et de kappa arrivent à des conclusions différentes avec une transformation plutôt qu’un déclin.

Facteurs explicatifs du vote de classe

Il est possible de faire une énumération des facteurs explicatifs qui influenceraient le vote de classe. Ces facteurs sont plutôt des facteurs structurels de long terme, mais il peut y avoir des changements conjoncturels qui peuvent faire varier le vote de classe :

- prospérité économique : elle influencerait le vote de classe en le faisant diminuer. C’est ce qu’on appel aussi la théorie de la modernisation avec la monté des classes moyennes avec la perte d’une importance entre clivages de classes. C’est un effet qui peut être plutôt négatif sur le vote de classe.

- chômage : il aurait tendance à faire augmenter le vote de classe lié à l’insécurité de l’emploi notamment. Ce sont des théories qui s’inscrivent dans l’idée des théories de la modernisation.

- emploi dans l’industrie : la diminution du secteur industriel et l’augmentation du secteur des services qui caractérise les sociétés post-industrielles aurait tendance à faire décliner le vote de classe, ne serait-ce que parce qu’il y aurait une diminution de la classe ouvrière. Il y aurait également l’émergence de nouvelles classes par l’émergence de nouveaux conflits et de nouvelles lignes de démarcation, à savoir de nouveaux clivages qui ferraient diminuer le clivage de classe et le pouvoir explicatif du clivage de classes. Il ne faut pas confondre la force explicative des clivages en général, à savoir le rôle qu’ont les clivages dans l’explication dans les comportements politiques et le rôle et les forces explicatives de ce clivage.

- taille de la classe ouvrière : il y a une diminution de la classe ouvrière qui amènerait à une diminution du vote de classe.

- densité syndicale : le vote de classe augmente avec la densité syndicale mais il y a une certaine ambiguïté dans cette relation. Il n’y a pas toujours un consensus en sciences sociales. Cette ambiguïté est liée au fait qu’il peut y avoir une forte syndicalisation des travailleurs non-manuels qui implique une forte que les travailleurs non-manuels vont travailler pour la gauche et ce faisant, ils diminuent le rôle ou l’opposition gauche – droite traditionnelle et donc le rôle du clivage de classe dans l’explication du vote.

- inégalités de revenu : les différences de revenu sont liées au niveau de vie des différentes classes sociales. Des grandes différences de revenus prédisent des fortes importances dans le vote de classe.

- fragmentation religieuse et taille du groupe séculaire : c’est l’un des facteurs étudié traditionnellement dans la politique comparée, à savoir l’importance du clivage religieux qui est l’un des quatre clivages traditionnels de Rokkan. Beaucoup d’études montrent que si ce clivage est important, cela fait diminuer le rôle de la classe sociale parce que les ouvriers qui pourraient potentiellement s’inscrire dans un vote de classe gauche – droite, ceux qui sont croyant s’inscrivent dans un clivage religieux. Le clivage de classe et le clivage religieux sont étudiés comme les deux grands clivages qui sont en concurrence par rapport à l’étude de l’effet des clivages sociaux sur le comportement électoral.

- polarisation gauche – droite : les études montrent que la polarisation tend à augmenter le vote de classe.

- impact de la nouvelle politique des valeurs : cela renvoi aux nouveaux clivages.

Ce sont des facteurs explicatifs qui résultent d’une revue de la littérature. Les transformations de la société post-industrielle produisent une diminution du vote de classe mais cela dépend de la manière on dont définit la classe; le vote de classe; de la manière dont on les mesure . Certains auteurs sont arrivés à un constat opposé, à savoir que non, il n’y a pas un déclin du vote de classe mais du moins, il y a une stabilité qui peut aussi parfois se transformer en une augmentation. Surtout, si on adopte une définition de la classe et du vote de classe plus sophistiquée, on arrive non pas à un constat d’une diminution mais à un constat d’une transformation du vote de classe qui reste important mais qui s’est transformé dans ses mobilités.

The new cleavages

The new cleavages are the cleavages other than the traditional four cleavages of Rokkan. This should be taken with some caution. One of these new cleavages dates back to the 1960s. This is new compared to the traditional Rokkan cleavages:

- materialism - postmaterialism: the emphasis is more on personal fulfilment than on satisfying personal needs. Some people talk about this divide as being a value divide because it is difficult to see what is the social inking or the inking into a social structure of this opposition of values. There has to be the structural basis, which is the subjective identity basis and then politicization. It is not enough that there is a value cleavage that would be one set of values that would be opposed to another set of values.

- new individualism: it is the passage from a heteronomous value system, i.e. respectful of the social, moral or even religious order, to an autonomous value system, subordinated to reason or to the needs of the individual. Some have described this shift from an ethos of duty to one of self-fulfilment. The individual is established as the supreme end.

- openness - tradition (winners - losers of globalization): this divide is often articulated and mobilized in literature today. It is the conflict engendered by the structural changes linked to globalization and at the political level that is expressed on a dimension of openness rather than on a tradition. It is a cleavage that has rather been used to explain the emergence of the radical right, which would be based or anchored in this cleavage.

Annexes

References

- ↑ Marco Giugni - UNIGE

- ↑ Marco Giugni - Google Scholar

- ↑ Marco Giugni - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Marco Giugni - Cairn.info

- ↑ Marco Giugni - Protest Survey

- ↑ Marco Giugni - EPFL Press

- ↑ Marco Giugni - Bibliothèque Nationale de France

- ↑ Bartolini, Stefano, and Peter Mair. Identity, competition and electoral availability: the stabilisation of European electorates, 1885-1985. Colchester: ECPR, 2007. Print.

- ↑ Tilly, Charles. From mobilization to revolution. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co, 1978. Print.

- ↑ Muller, E. N. (1980). From Mobilization to Revolution. By Charles Tilly. (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1978. Pp. xiii + 349. No price given.). American Political Science Review, 74(4), 1071–1073. https://doi.org/10.2307/1954345