« The legal and political problems of the conquest I » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| (15 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 41 : | Ligne 41 : | ||

<gallery mode="packed"> | <gallery mode="packed"> | ||

Fichier:Alexander VI - Pinturicchio detail.jpg| | Fichier:Alexander VI - Pinturicchio detail.jpg|Pope Alexander VI, fresco by Pinturicchio, 1492-1495. | ||

Fichier:Christopher_Columbus.PNG| | Fichier:Christopher_Columbus.PNG|Posthumous portrait of Christopher Columbus painted by Sebastiano del Piombo. | ||

Fichier:Isabel_la_Católica-2.jpg| | Fichier:Isabel_la_Católica-2.jpg|Isabella the Catholic. | ||

Fichier:Michiel_Jansz_van_Mierevelt_-_Hugo_Grotius.jpg|Hugo Grotius, Portrait par Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt (1631). | Fichier:Michiel_Jansz_van_Mierevelt_-_Hugo_Grotius.jpg|Hugo Grotius, Portrait par Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt (1631). | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Overall, there are three states that condition the legal and political debate on the discovery of the New World. Traditionally, this third imperial movement is divided into three stages: | |||

*1492 | *1492 - 1530: Portugal and Spain will occupy as many territories as possible, which are currently Santo Domingo, Cuba, Mexico and South America. It is the stage of a somewhat unbridled conquest. There is going to be a whole debate on the question of insignia and flags, the French, Dutch and English will contest them, because it is the one who has the strength to hold the territory. | ||

*1530 | *1530 - 1625: from 1530 onwards, there is a reflection on the political and military consequences of the empire. | ||

*1625 | *1625 - 1960/70: this period lasts until 1625 when the new reflection on the idea of empire begins, because a major book on public international law, De jure belli ac pacis by Grotius, is published, which opens the new reflection on the idea of European empire. The Grotian moment will only come to an end relatively recently. Arguments from the Grotius to certain treaties of public international law can be found in the 1960s and 1970s. | ||

{{Translations | {{Translations | ||

| fr = Les problèmes juridico-politiques de la conquête I | | fr = Les problèmes juridico-politiques de la conquête I | ||

| es = | | es = Los problemas legales y políticos de la conquista I | ||

}} | }} | ||

= | = The legal and political debate on the discovery of the New World = | ||

From 1530 onwards, a series of theoretical questions were considered in Europe. Can an empire be built on a conquest, on a territorial acquisition? This debate emerged in Spain from 1530 onwards through a whole series of writings on the status and legitimacy of the Spanish occupation. Between 1594 and 1530, there was no interest in the status of the Indians. The debate on the nature of the Amerindians in a reflection on the empire emerges and will emerge in Spain because Spain with Portugal are the great First European empires that were born in parallel to the [[Rome's Western heritage: the Holy Roman Empire|Holy Roman Empire of Germany]]. | |||

If we answer the question of whether they are men, we answer the question of whether they have rights and especially the right of ownership. This reflection takes place in three directions. Three texts answer the question of the status of the Amerindians. Sepulveda had made only one trip while La Casas had lived among the Indians. In his memoirs, Las Casas worked as a jurist, but also as an anthropologist. During the Valladolid controversy, under the presidency of the Pope, it was necessary to determine whether the Indians had rights or not and saw two great theologians and jurists confront each other. | |||

[[Fichier:Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda.jpg|thumb|Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda.]] | |||

The first Sepulveda text is the most indienophobic text of the time, responding to the status of the indigenous and conquered peoples. | |||

{{citation bloc|Let us compare these qualities of prudence, character, manageability, temperance, humanity and religion (of the Spaniards) with those of these hommelets (humunculi), in which there are hardly any vestiges of humanity, which not only lack any culture, but are not even used, Neither knowledge of the alphabet, nor do they preserve monuments of their history, IF it is not some vague, obscure and blind memory of a few facts recorded in a few paintings, which are devoid of any written law and have only barbaric institutions and customs. And about their qualities, if one asks about their temperance and gentleness, what can one expect from these men who are given over to all kinds of passions and who, for some of them, do not hesitate to feed on human flesh (...). ) As for the fact that some of them seem to have a certain talent, as shown by the building of certain works of art, this is not an argument in favour of any human prudence, since we see certain creatures such as bees or spiders doing what no human industry manages to imitate [...]. I referred to the customs and characters of these barbarians - what then of their unholy religion and the odious sacrifices that characterise it, since worshipping the devil as gods, they do not believe they can appease them with better sacrifices than by offering them human hearts?}} | |||

This text dates from 1547 and was written by Sepulveda and deals with the just causes of the war against the Indians. It is the first great text of reflection on the nature of the Amerindians. It is a text representative of those who would reply that the Indians in the new empire in the making have no rights. It is possible to divide this text into three parts. | |||

* Basically, what Sepulveda tells us, the central argument of this part is that these peoples have no culture because culture is a culture based on the written word, on history and on laws. In other words, Sepulveda has a Eurocentric definition of culture. A civilization or culture can only be called culture or civilization if a community has written laws, has a history, has monuments, has a relationship to its past that is the same as "ours". This type of argument is today reflected in the idea of the superiority of culture over others. The referents are often referents that refer to Sepulveda. | |||

*They are not men, but animals because they are men who are not endowed with reason and given over to their vile passions and because they are given over to their passions are like animals who have no reason. There is a double logical transition: Indian peoples are beings of passion, animals are beings of passion without reason, and therefore Indians are animals. The equation between Indians and animals is linked to the absence of reason. | |||

* The theologian's argument prevails over the jurist's argument, because there is only one culture, there is only one criterion to distinguish animals from men and there is only one religion which is the Christian religion to which the Indians do not adhere. | |||

The other answer is given by Las Casas, which is a great answer to Sepulveda. This text is published in 1542. | |||

[[ | {{citation bloc|The men who inhabit these immense regions have a simple character, without malice or duplicity; they are submissive and faithful to their native masters or to the Christians they are obliged to serve: patient, quiet, peaceful, incapable of insubordination and revolt, of division, hatred or vengeance [...]. These peoples have a keen, prompt intelligence; they are without prejudice; hence their great docility to receive all kinds of doctrines, which they are moreover very capable of understanding; their morals are pure and they are found in such good and perhaps better dispositions to embrace the Catholic religion than any other nation in the world.... [...]}} | ||

[[Fichier:Bartolomedelascasas.jpg|vignette|Portrait of Bartolomé de las Casas (anonymous, 16th century).]] | |||

It is the exact opposite of Sepulveda. The Casas, in a very Indianophile text, defends the human status of Indians who have the capacity to understand and learn. By saying that their morals are pure, it responds to Sepulveda, who made Indians into animals somewhere because of the impurity of their morals. The religious argument is invoked to justify his position making Indians capable of embracing the Catholic religion. | |||

The Middle Way was proposed by Vitoria, who in 1539 published a founding text on modern empires entitled "De Indis". It is possible to see the synthetic dimension of this text. | |||

{{citation bloc|For, in all truth, they are not mad, but they possess in their own way the use of reason. | |||

1. For they have a certain organisation in their affairs, since they have cities where order reigns; they know the institution of marriage; they have magistrates, chiefs, laws, works of art; they trade. All this presupposes the use of reason. | |||

2. In the same way, they have a kind of religion [...]. If they seem so stupid and obtuse, I think that this is largely due to a bad and barbaric education; for we also see many peasants who are hardly different from animals [...]. From all the above, it follows that, without doubt, these barbarians had, like the Christians, real power, both public and private.}} | |||

For Vitoria, they are men because they are rational. Amerindian culture is certainly different from European culture, but it is not as different as Sepulveda claims, and they also know the institution of marriage, which from a legal and theological point of view was an important sign of European culture as a kind of referent. | |||

In the second part two important elements emerge. They are not animals because they are endowed with reason. They are men who have both public and private power, in other words, they have rights. This will make Vitoria a defender of the property rights of indigenous peoples. | |||

Is there anything in common between these three authors? All these authors have a clear awareness of the diversity in which Amerindian cultures evolve. However, they always reason in European terms using Eurocentric language. Philosophically or theoretically, they use European categories to define Amerindians. | |||

In these three texts, an old division that comes from Roman law between free men and slave men appears. For these authors, the world is divided between free men and slave men. There is also the opposition between civilised peoples and between barbarian peoples irrigating, draining all imperial conceptions until recently. Until the 1970s, the great treaties of public international law began by dividing the world into civilised and uncivilised states. The division between civilised and uncivilised states still exists today. This theorising continues to permeate our way of thinking. The third category that allows us to think about the relationship between Amerindians and Spaniards is the relationship between believers and infidels. All these authors understand the world through the prism between believers and infidels. These conceptual categories will be found in the international legal order until very recently. | |||

[[Fichier:Spain and Portugal-fr.png|thumb|The dividing line according to the bubble ''Inter cætera'' (dotted line), according to the Treaty of Tordesillas (in purple), and its extension according to the Treaty of Zaragoza (in green).]] | |||

What is the legitimate authority? Who has sovereignty? The "bubble inter caetera" answered the question in 1493 because it had given Portugal and Spain jurisdiction over the newly conquered lands, but it had not answered the question of whether the right of ownership applies, who has sovereignty, who is the sovereign, who has dominus mundi. The Germanic emperor will have declared himself dominus mundi just like the pope, but who holds it then? | |||

Vitoria | Vitoria will send back both the emperor and the pope in "De Indis" of 1539: | ||

* | *the emperor does not hold the dominum mundi; | ||

* | *the pope does not hold the dominum mundi; | ||

* | *there is no right of discovery strictly speaking, nothing can legitimise the taking of possession by the Spaniards. In other words, there is no right of the first occupant; | ||

* | *Vitoria accepts and recognises the need to spread Christianity; | ||

* | *Vitoria rejects the idea that the New World was given to the Spaniards by the will of God. | ||

Vitoria has an extremely strong spirit of synthesis, it proceeds summarily by presenting these arguments, which it then develops : | |||

*1. the emperor is not the master of the whole world. | |||

*2. even if he were master of the world, the emperor could not take over the provinces of the barbarians, nor institute new masters, nor deposit the old ones, nor collect taxes. | |||

*3. If we speak properly of civil sovereignty and power, the pope is not the civil or temporal master of the whole world. | |||

*6. The Pope has no temporal power over the barbarians of India, nor over other infidels. | |||

*12. If the barbarians are invited and exhorted to listen peacefully to the preachers of religion and if they refuse to do so, they are not excused from mortal sin. | |||

[[Image:Francisco vitoria.jpg|thumb|Francisco de Vitoria.]] | |||

When Vitoria published "De Indis" in 1539, he wanted to send the emperor and the pope back to back to propose a new vision of the empire. He accepted the idea that the Indians were men and therefore had natural rights. One of the essential rights is the right of ownership. What is at stake, since it is a fact that the Spaniards are conquering the New World, which one is it? Vitoria notices that the Spaniards are conquering, killing and plundering part of this continent. The question now is what are the possible conditions for entering into war and what are the conditions for a just war. If the Spaniards or any colonisers have rights, what are they? Can they act through war? Under what conditions can war be waged to conquer the world? Are there criteria of just war that allow or do not allow the conquest of the world? | |||

The third conception of empire that is emerging in Europe is accompanied by a real reflection on war and more precisely on just war. The entire imperial vision that would take shape from 1550 onwards is accompanied by a vast reflection on war that accompanies the conception of Roman imperial ideology. Among the Romans, the question of justice and the righteousness of a war comes with Christianity. In Christian doctrine, in the order of reflection on war and peace there is the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus Christ explains the doctrine of non-resistance of Christianity. The Sermon on the Mount is an important benchmark in Christianity's relationship to violence. The doctrine of just war was born in the context of finding a formula that would allow Roman citizens to wage war without denying their romanticism. | |||

Vitoria develops the argument {{citation|if the emperor is the master of the world" as a first answer. The emperor is not the master of the world for at least three reasons}}. Indeed, there can only be a right under natural law, divine law or human law. Now, let us show this, {{citation|the emperor is not master of the world by virtue of any of these rights}}. By virtue of these three rights, the emperor is not the holder of dominium mundi. The emperor is not master of the world by virtue of divine, human and natural law. | |||

The second answer {{citation|Even if the emperor was the master of the world, he could not take over the Indies}}. Let us suppose that the emperor is the dominum mundi, he could not take over the Indies. It is a very clear will to remove the emperor from any territorial claim on the Indies. | |||

[[Fichier:The Meeting of Cortés and Montezuma.jpg|thumb|left|The meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma as seen by an anonymous painter from the {{S -|XVII}}]] | |||

An argument that is absolutely essential to the whole imperial ideology is affirmed: "Those who attribute to the emperor power over the world do not say that he has a power of possession over it, but only a power of jurisdiction. But this does not authorise him to annex provinces for his own personal profit, nor to distribute fortresses and even land as he pleases". In a very harmless way, Vitoria tells us that even if the emperor had territorial claims, he could only invoke "juridictio" or "imperium", but not "dominium". | |||

The Romans distinguished "imperium" or "juridictio", which is the equivalent of sovereignty from "dominium", which is the power of ownership. The emperor is not the holder of both property and sovereignty at the same time because a distinction must be made between the two. This will have major consequences from the sixteenth century to the twentieth century. | |||

The great European empires that are being built on the rubble of the papal vision and empire will be different, offering different models of empire. Grotius will propose a model of the international order that will allow the great European empires to take root and find a legal basis and justify their expansion. | |||

[[Fichier:The entrance of Hernan Cortés into the city of Tabasco.jpg|vignette|Entrance of Cortés in Tabasco.]] | |||

Vitoria | Vitoria is the first jurist and theologian to question the limits of the papal-imperial model from the Spanish imperial model, questioning the Pope's competence in matters of dominium mundi and the Emperor's competence. It opens a third way for the great European empires that are being established. Vitoria will open the way, but it will be up to Grotius to refine it, to finish it and to propose a theory of international order very favourable to European empires. | ||

Vitoria | Vitoria rejects both the claims of the Papal Emperor and the German Emperor. Vitoria takes up the distinction made in Roman public law between dominium and imperium. Vitoria's second answer is {{citation|Even if the emperor was the master of the world, he could not take over the Indies}}. It is a challenge to the vision of the imperial conception of the Empire by instrumentalizing the distinction between dominium and imperium, i.e. the power of jurisdiction and the power of possession. This distinction, which Grotius will take up again as a theorist of European empires, will serve as a basis for the Grotian vision. | ||

Vitoria asks the same question about the pope, whether he is the holder of the dominium mundi, whether the pope is the master of the world. The question is clearly asked, "Is the pope the master of the world? "he concludes that he is not. The first answer is that "the pope is not the temporal master of the world". For Vitoria, "the pope has a power that is ordered to the spiritual", thus explaining it as follows: "This means that he has temporal power in so far as it is necessary for the administration of spiritual things". It is clear that Vitoria takes over the papal competence resulting from the Worms Concordat, which left the Pope the competence to manage the goods of the Church, which Vitoria assimilates to a temporal power. | |||

On the other hand, it limits the intrusion of spiritual power into temporal power. In support of its point of view, Vitoria posits that {{citation|lhe pope has no temporal power over the Indians or other infidels}}. This is a rather strong statement. In other words, newly conquered populations and newly conquered lands do not depend on the authority of the pope. There is no Church property in the newly conquered territories, so the pope cannot claim any jurisdiction over them. | |||

[[File:Cortez-montezuma-mexico-city.jpg|thumb|Cortez et Moctezuma.]] | |||

The ''ius ocupacio'' or right of discovery or right of the first occupant is a right that has been debated in Europe since the 12th and 13th centuries, not so much for the territories of the Amerindians but for certain European territories that are not occupied or only slightly occupied. This question concerns, from the 13th century onwards, lands in northern Poland, and the question is whether the fact of occupying these lands or discovering them gives the person who first plants his flag a legal basis. It is a question that already emerged in Europe in the 13th century for European territories that are currently in areas of the Ukraine. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy had discovered them and the question of jurisdiction arose. | |||

Vitoria wondered whether there was or is a right of discovery and whether this right gives rights. He asked whether under jus gentium there is a right of discovery concluding that in theory there is, but in practice this right cannot be invoked to occupy Amerindian lands. The reason is simple since he has decided whether they are men by the affirmative. Therefore, if they are men, they have rights and it is not possible to invoke a right that is superior to individual natural rights, including the right of ownership. It is consistent in its logic, recognising the possibility of invoking the right of discovery in certain regions of the world in theory, however, in practice, in the context of the conquest of the Indies, it is not invocable, because the Indians are men, they have property and they own their goods and their land. | |||

In the third part of the book, Vitoria titles "Legitimate Titles of Spanish domination over the Indians". This is an interesting thing. The first two parts aim to reject papal or imperial claims and the third part aims to delimit, define and clarify the legitimacy of the Spanish adventure. Do they have the right to discover the Americas, to claim dominium or imperium over these lands. In other words, what is the applicable law as it stands? This part shows that man is much more ambiguous. Man is going to open a breach with terrible consequences in the justification of the European imperial adventure. | |||

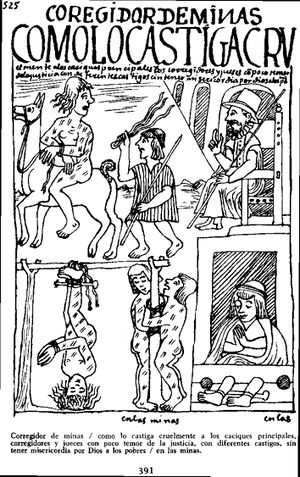

[[Fichier:01-CORONICA Y BUEN GOBIERNO-Poma de Ayala.jpg|vignette|gauche]] | [[Fichier:01-CORONICA Y BUEN GOBIERNO-Poma de Ayala.jpg|vignette|gauche]] | ||

The contents of this section speak for themselves. The second paragraph reads: {{citation|Spaniards have the right to go and stay in the territories of the Indians, but on condition that they do not harm them, and the Indians cannot prevent them from doing so}}. This paragraph is ambiguous since Spaniards have the right to conquer and occupy the newly conquered lands, and above all, others cannot prevent them from doing so. The fourth paragraph also speaks for itself: {{citation|It is not permitted for barbarians to prevent Spaniards from participating in the goods that are in their territories and that are common to citizens and foreigners}}. Vitoria aimed at gold and precious metals which are common to everyone. | |||

All of Vitoria's ambiguity can be seen in the introduction of the jus comunicatio, which is the right of society and communication. It is on the basis of this right that the Spaniards have legitimate titles to these newly conquered lands. What is the legal basis that allows the Spanish to conquer and occupy the newly discovered lands? {{citation|Spaniards have the right to go and live in India}}. For Vitoria, it is a fundamental right to move. | |||

The ambiguity arises with the second principle that justifies the conquest of the Spanish: {{citation|The Spaniards have the right to trade with the Indians}}. This is an extremely clear affirmation of the right to trade. It is because they have the right to trade with the Indians that the Spaniards can occupy, conquer and expand. Trade is a very important element because the right to trade will become a leitmotif of the great jurists who founded jus gentium. The right to trade is an inalienable and fundamental right. To make it a fundamental right implies that those who do not respect it are liable to be subjected to war. In other words, if a certain number of fundamental rights are not respected, States, the entities responsible for maintaining and respecting these rights can attack for this. | |||

[[Fichier:De Bry 1c.JPG|vignette|upright=0.6| | [[Fichier:De Bry 1c.JPG|vignette|upright=0.6|The cruelties of the Spaniards (Jean Théodore de Bry).]] | ||

In addition, for Vitoria : {{citation|Spaniards can participate in public goods}} asserting that {{citation|If the barbarians have goods in common with citizens and foreigners, it is not allowed for the barbarians to prevent Spaniards from participating and enjoying them}} implying a pretext for war. The title of the work speaks for itself {{citation|LThe lesson on the Indians and the law of war}}. It is a logic of establishing Spanish property titles and in a logic of setting up the conditions for making war. Failure to respect a number of such things as the right to trade or to participate in public law is a just cause of war. | |||

Vitoria's fourth answer is that {{citation|Spaniards can acquire a right of citizenship in India}}. They may very well be citizens of the territory they have conquered, opening the door to the sharing of sovereignty by the colonists. Vitoria's fifth answer is that "In case of hostility from the Indians, the Spanish can defend themselves by war". There is no longer any ambiguity in this answer: {{citation|Let us suppose that the barbarians want to prohibit the Spaniards from doing the things that have been said above that are allowed to them by the law of nations, such as trade and the other activities we have been talking about. The Spaniards must first avoid scandal by using wisdom and persuasion. They must show all kinds of reason that they have not come to harm the Indians, but that they want to be welcomed and live peacefully without harming them. And they must not only affirm this, but also give proof of it, according to this word: it is fitting that the wise should first test all things by words. If the barbarians do not want to accept the reasons given to them, but if they want to resort to violence, then the Spaniards can defend themselves and do whatever is necessary for their safety, because it is permitted to repel force by force. Moreover, if they cannot obtain security otherwise, they can build citadels and fortifications; and, if they have suffered an injustice, they can, on the decision of their prince, punish it by war and exercise the other rights of war.}}. | |||

The fate of the so-called "indigenous" populations was sealed, because the just motives for war are clearly stated. Vitoria opened a major breach that the papal or imperial conception had never addressed, which was the contribution of a discourse on the right of conquest and the conditions of the right of conquest, and more precisely on the conditions of a just war. This is a new element that is not found in the traditional imperial Germanic conception nor in the papal conception. In other words, until Vitoria there was little or no reflection on war and the right of discovery. It was the reflection in Vitoria that gave European ideology a new character and scope. | |||

Vitoria's ambiguity evaporates when Vitoria says {{citation|Spaniards can subdue Indians}}. The ambiguity that was perceived and detected at the beginning is no longer at all de rigueur : {{citation|If the Spaniards have tried all means and if they can only obtain security from the barbarians by taking over their cities and subjugating them, they can also do so legitimately}}. The tone was set. This sentence is crucial because Vitoria opens the way to a much more aggressive vision of great empires. Conquest was an important part of the Roman Empire, but Rome, in the opinion of Roman historians, did not show aggression or conquest of the world. Rome never had any claim to world domination. Papal and imperial conceptions were not built on an aggressive vision of world order. It is a process of securing the emperor's competences or securing and protecting the pope's competences. With the discovery of the New World, the new model of empire and the new conceptions of empire that are emerging are much more ambitious and conquering. It is clear that the concept of empire is evolving in a much more expansionist direction. | |||

[[Fichier:DelasCasasParraDF.JPG|vignette|Bartolomé de las Casas.]] | [[Fichier:DelasCasasParraDF.JPG|vignette|Bartolomé de las Casas.]] | ||

Vitoria's seventh answer is that {{citation|the Spaniards can exercise all the rights of war against the Indians}}. It is implied that the Spaniards are entitled to intervene if the Indians do not respect a number of natural rights. | |||

The first part somewhere enumerated the fundamental rights in the international order, namely the right of discovery and the right to trade. The second part introduces another right which is the right of evangelization. This is a major contribution from Vitoria, which is a reflection on the right of evangelisation as a right that is part of and can be invoked by the great European empires in the making: "There may be another title: the expansion of the Christian religion". The first answer is that Christians have the right to evangelise the Indians. | |||

The second answer is that "The evangelisation of the Indians was entrusted especially to the Spaniards". This will be contested by Grotius as a Protestant who will not understand at all why the Spaniards have a monopoly on evangelisation. The third answer is that "This evangelisation excludes the use of force". It is a right which is an invocable right, but which does not allow the use of war in order to impose it. The fourth answer removes any ambiguity which is that {{citation|Indians should not oppose evangelization}}. If they do, they are liable to be the object of war. In other words, if they oppose it, it is a just cause for war for the Spanish and Portuguese Empire: {{citation|It is clear from this answer that, if the Spaniards cannot otherwise promote the cause of religion, they are also allowed, for this reason, to take over their lands and provinces, to create new chiefs, to depose the old ones and to do, under the law of war, what could legitimately be done in other just wars. But they must always act with restraint and moderation, so as not to go further than is necessary. They must prefer to give up their own right rather than undertake something that is not allowed. Finally, they must constantly orient everything to the good of the barbarians rather than to their own advantage}}. The Indians have relatively little room for manoeuvre. In other words, if they refuse evangelisation, their chief can be changed, their provinces confiscated and all Spanish domination can be exercised without restraint. The right to evangelisation does not imply conversion limited to preaching. In other words, the Indians cannot be forced to convert, but they cannot prevent the Spanish and Portuguese from spreading the good word. | |||

Vitoria postulates the following: {{citation|I have no doubt that the Spaniards were forced to resort to violence and weapons in order to stay there. But I fear that they went beyond what the law and justice allowed}}. It is necessary that the European powers that conquer the world show restraint and respect a certain number of rights, which will become jus in bello. | |||

It is clear that Vitoria is still trapped by two visions. In other words, it is clear that when you read Vitoria's text, it oscillates between two attitudes. An attitude that rejects the Pope's competence and the emperor's competence to leave the Indians control, ownership and sovereignty over their territory. In the third part, the introduction of a number of rights in the name of jus gentium such as the right to trade, evangelise and communicate opens the way to an expansionist vision of European empires. There is a tension in Vitoria between a man who is aware of the horrors of conquest, but who somewhere provides a number of legal arguments to justify it. This tension can be found in Grotius, who will present a model and a coherent imperial vision. | |||

Following Vitoria, the empires in Europe were set up and began to conquer part of the world. The characteristics of the empires are different. The Spanish and Portuguese Empires do not correspond to the English Empire, which is much later. The material characteristics are different. | |||

= The European empires = | |||

== Portuguese Empire == | |||

[[Fichier:Portugal Império total.png|vignette|The Portuguese Empire at its height.]] | |||

The Portuguese Empire began to emerge at the end of the 15th century with the discovery of the India sea route in 1497. The Portuguese conquered part of South America, part of India with a number of trading posts, also in Africa, in the Arabian Peninsula with the occupation of the Strait of Hormuz, as well as islands such as Malaka, Java and Macau. Portugal will also occupy Brazil. It is an empire split with South America, some regions of South-East Asia, some African trading posts. It is an empire of trading posts built on the basis of a certain number of areas or ports, but it is not an empire that will penetrate inland. It is a maritime empire that is essentially based economically on monopoly. The comptoirs are only allowed to trade with Portugal. | |||

The empire is not going to last very long, falling apart very quickly because Portugal does not have the means to control its immense territories and its many trading posts. It is an empire that will become decentralised. The governors of the comptoirs would soon have a great deal of authority and a series of important competences. | |||

== The Spanish Empire == | |||

[[Fichier:Spanish Empire Anachronous en.png|vignette|Anachronistic map of the Spanish Empire, at different periods.]] | |||

This is not the case of the Spanish Empire, which was born at the same time. Colonisation was extremely different from that of the Portuguese, beginning with the Antilles in 1510, followed by the discovery of Mexico, Central America, South America and precisely Peru. Unlike the Portuguese Empire, the Spanish Empire is an extremely centralised empire, very well organised, divided into kingdoms and vice-kingdoms. It is an empire centralised from Madrid and extremely well organised. It is an empire divided into two viceroyalties, with the Kingdom of New Spain having Mexico City as its capital and the Kingdom of New Castile having Lima as its capital. The Spanish Empire is economically extremely well organised, not based on monopoly, but based on a form of plunder in order to recall to Spain as much common and public property as possible. The Spanish Empire is at the service of the Spanish monarchy economically speaking. Finally, the massive recourse and use of Spaniards to slavery. The institution of slavery will be made by the Spaniards a cardinal stone of their empire. As the Amerindian peoples were decimated by war and disease, the Spaniards were to be great importers of slaves from Africa and India. The Spaniards will be the ones to build their empire around this institution and make it their economic and political engine. | |||

== The English Empire == | |||

[[Fichier:The British Empire.png|vignette|Areas of the world that were once part of the British Empire. Current British overseas territories are highlighted in red.]] | |||

The third empire that is being established is the English Empire. Like the French Empire, it is a late empire. The Spaniards and the Portuguese would soon occupy it, while the English started late in 1583 with the discovery and annexation of a part of Canada known as Newfoundland. The English Empire was a relatively late empire that was formed in parts of Canada, mainly in what would become the American colonies and then some African trading posts, particularly in southern Africa. However, the English conquest came relatively late with the absorption of the French Empire in 1763. The great years of the English Empire were the 18th and 19th centuries. From 1587 onwards, they took possession of the American colonies where they established a whole series of trading posts in Massachusetts and Virginia. It is interesting to note that Florida was in Spanish hands. The Kingdom of Mexico also ruled over South Florida. It is a late empire, rather disparate, but concentrated mainly in North America. It is also an empire that was to be based on monopoly. The colonies could and should only trade with Great Britain. It is a model that all the great economists would later criticize, but it is a model based on monopoly. It's an extremely decentralised empire. For the part after 1750, the British crown would regain control of its empire, but until 1742, the British Empire was essentially decentralised. | |||

Like the Dutch Empire, it is a Protestant Empire. They are empires based on an extremely Protestant and Calvinist view of human nature. This religious dimension needs to be clarified because the Spanish and Portuguese empires are like the armed arms of the Church, claiming since the Bull inter caetera of 1493 to be the representatives of the Catholic Church in the new territories. Since the Reformation was established in Europe from 1517 onwards, the British and the Dutch wanted to retain their autonomy and not rely on the church to justify their conquest. | |||

== | == The French Empire == | ||

[[Fichier:Anachronous map of the All French Empire (1534 -1970).png|vignette|Areas colonised by France throughout its colonial history.]] | |||

The French Empire is also an extremely late empire, but ultimately quite small. The First French Empire was absorbed by the English by the Treaty of Paris in 1763, when France lost its entire colonial empire. It will reconstitute it in the 19th century from the Algerian affair in 1840 and in Africa from the Congress of Berlin. It is an empire which does not extend over immense territories. France was to occupy territories in Canada, colonies in Quebec, and in two other regions of North America, Florida and Louisiana, i.e. the Mississippi region from 1603. There is a Francophile tradition in Louisiana, which was sold to the United States by Napoleon. Basically, Louisiana remained under French rule, which had created a cordon between Canada and Louisiana. It is a paradoxically small and late empire, but above all it is an empire that is made up of a multitude of small trading posts and strongholds. Economically, it is an empire that is not based on monopoly, but on a form of free trade and on an extremely precise economic sector, which is the fur trade. It is not an empire built on gold or tin, it is not an empire that will be built on natural assets, but it is an empire essentially based on the fur trade. It is an empire founded not only on political and military conquest, but also on missionary work with the extremely marked help of religious orders, particularly the Jesuit order which played a capital role in the establishment of the First French Empire. The French called on Jesuit missionaries to help them occupy the conquered territories. What the English, Spanish and Portuguese did not have, the Jesuits were able to communicate with the indigenous populations. The first Iroquois, Inuit, dictionaries of the great Indian tribes of North America are Jesuit dictionaries translated into Latin from 1620 - 1630. These are truly people who speak the language, come into contact with the indigenous populations and live with them. The mediators are always Jesuits who speak both languages. In a way, the French Empire owes its longevity and development to the Jesuit order. It also means that the French Empire established different relations between the Spanish and the English and the indigenous people. | |||

== | == The Dutch Empire == | ||

[[Fichier:DutchEmpire4.png|thumb|450px| | [[Fichier:DutchEmpire4.png|thumb|450px|Map of the territories settled at one time or another by the Netherlands or the United Provinces. Those in dark green are administered by the Dutch West India Company, those in light green by the Dutch East India Company.]] | ||

The Dutch Empire will give all its fullness to the 17th century. The Dutch Empire is the latest to become an extremely powerful empire very quickly. It got its power from the fact that the Dutch understood before anyone else that the strength of an empire is its fleet and its navy. Having a powerful fleet to cover the surface of the earth and repatriate goods is a considerable asset. It is an essentially maritime empire that will allow the Dutch to occupy extremely varied regions, including present-day Indonesia, Ceylon, Africa in Guinea and the Gulf of Guinea, Dutch Guiana, and also southern Africa in the Cape region. It is an extremely well-organised empire both in terms of management and military organisation. The very powerful East India Company was created for this purpose in 1608, which was followed in 1621 by the West India Company. There is a form of privatisation of the Dutch empire in the sense that the Dutch empire was managed by private companies. Spain, Portugal, France, England, the governors had to report to the royal power, but not in the case of the Dutch. | |||

It was these two private companies, the East and West India Company of 1608 and 1621, that were responsible for managing the Dutch Empire. Among the powers of these two companies was the power granted by the Dutch government to negotiate treaties with public and foreign powers and to raise armies. They were private companies with the powers of a state. This is a true characteristic of the Dutch Empire, which entrusted its interests to two companies with the ability to raise armies and sign treaties. It is an empire deeply based on free trade. The Dutch will be the great defenders of a fundamental right that Vitoria had not thought of, which is a natural right in the international order that does not come under domestic law or individual rights, but under the classical international law that was called at the time jus gentium, also known as the right of the people. Until 1781, it was called jus gentium. The Roman name for international law is used. There is a fundamental right that the Dutch, as good free traders and merchants, will defend, namely the right to free movement of goods by sea. It was the free traders who created a commercial and maritime empire. In order to allow this empire to exist and to trade, we must not only defend an open law of the sea but also defend the idea that the sea belongs to no one. A first reflection on the sea and the property of the sea is Grotius. | |||

= Annexes = | = Annexes = | ||

Version actuelle datée du 8 janvier 2021 à 19:54

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in America with two white banners emblazoned with a green cross and a yellow banner bearing the initials F and Y of the sovereigns Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile.

| Professeur(s) | Alexis Keller[1][2][3] |

|---|---|

| Cours | History of legal and political thought: the concept of empire from its origins to the present day |

Lectures

- The history of the concept of empire

- The foundations of the Roman model

- Rome's Western heritage: the Holy Roman Empire

- The papal conception of the empire and the emperor as dominus mundi

- The legal and political problems of the conquest I

- The legal-political problems of the conquest II

- From empire to federation: the American case

- Can a democracy be an empire?

We have seen that the Roman idea of empire gives rise to two branches: the papal conception and the imperial conception of the empire through the birth and reflection on the Holy Roman Germanic Empire. With the discovery of the New World, the two ideas of empire will no longer be able to confront each other and will be absorbed into a third vision of the empire linked to this major historical fact. The beginnings, the characteristics of two great branches are no longer applicable to the two great imperial forms that were born.

This discovery had a colossal impact on the idea of empire because it forced the theories of empire to propose a new model of empire. The papal and Germanic visions no longer made it possible to propose a model because the questions facing Europeans from 1492 onwards were radically different from those posed by the pope or the Germanic empire. Another model will emerge. The great theorists of the empire, and the great imperial jurists will ask themselves two main categories of questions, namely theoretical and practical questions.

The practical questions they will ask themselves after the discovery of the New World are:

- how to administer these new territories?

- what kind of legal order should be applied to these territories?

The theoretical questions are very important. The discovery of the New World forces imperial lawyers to ask themselves a whole series of theoretical questions:

- what is the status of the conquered peoples? What is the status of the individuals discovered? The stakes are high because these individuals will either have rights or they will not. Are they men?

- these two visions of empire are not based on a right of conquest, the question arises from 1492 onwards as to whether there is a right of conquest, can an empire be constituted from a right jus ocupacio? This is the problem of the legitimacy of newly conquered territories.

- Is there a particular mode of sovereignty? Who holds sovereignty over these new territories?

The first major theoretical answer to these questions, which emerged in the middle of the 15th century, was provided by Vitoria.

Three dates allow us to understand the discovery of the New World and put this discovery into perspective:

- the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453. Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire, it was the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire. This fall of Constantinople had a whole series of consequences, two of which are important. The first was the rupture of the route to the Indies, the end of trade between India and Europe and the rupture of the communication routes between Europe, India and China. This will force Europeans to look westwards. There is a very clear shift in the gaze of Europeans from Constantinople to the New World. Portugal is going to emerge as the relay power that will try to impose itself in this process of discovery and conquest.

- 1492 is not so much the conquest of the New World, but rather the reconquest of Spain by Isabella the Catholic against the Muslim troops. 1492 is the fall of Granada, which completes the movement to reconquer Christianity from Islam in Spain. The extremely powerful Queen of Spain will finance by giving her the title of Admiral Christopher Columbus in order to gain access to the Indies since the fall of Constantinople cut off this route.

- 1493 - Spain and Portugal will seek the advice of Pope Alexander VI to take a position on the right of conquest and in relation to the newly conquered territories. In 1493, Alexander VI promulgated the bull inter caetera, which was to be authoritative for decades. This bull promulgated the idea that all the territories conquered or to be conquered beyond Spain would belong to Portugal and Spain. The Pope gives full sovereignty to the Portuguese and Spanish "over all the Canary Islands discovered or to be discovered". The bull inter caetera will attribute to the two great imperial powers that will become the territories of the New World. This was contested a little later by the English, the French and the Dutch.

Overall, there are three states that condition the legal and political debate on the discovery of the New World. Traditionally, this third imperial movement is divided into three stages:

- 1492 - 1530: Portugal and Spain will occupy as many territories as possible, which are currently Santo Domingo, Cuba, Mexico and South America. It is the stage of a somewhat unbridled conquest. There is going to be a whole debate on the question of insignia and flags, the French, Dutch and English will contest them, because it is the one who has the strength to hold the territory.

- 1530 - 1625: from 1530 onwards, there is a reflection on the political and military consequences of the empire.

- 1625 - 1960/70: this period lasts until 1625 when the new reflection on the idea of empire begins, because a major book on public international law, De jure belli ac pacis by Grotius, is published, which opens the new reflection on the idea of European empire. The Grotian moment will only come to an end relatively recently. Arguments from the Grotius to certain treaties of public international law can be found in the 1960s and 1970s.

The legal and political debate on the discovery of the New World[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

From 1530 onwards, a series of theoretical questions were considered in Europe. Can an empire be built on a conquest, on a territorial acquisition? This debate emerged in Spain from 1530 onwards through a whole series of writings on the status and legitimacy of the Spanish occupation. Between 1594 and 1530, there was no interest in the status of the Indians. The debate on the nature of the Amerindians in a reflection on the empire emerges and will emerge in Spain because Spain with Portugal are the great First European empires that were born in parallel to the Holy Roman Empire of Germany.

If we answer the question of whether they are men, we answer the question of whether they have rights and especially the right of ownership. This reflection takes place in three directions. Three texts answer the question of the status of the Amerindians. Sepulveda had made only one trip while La Casas had lived among the Indians. In his memoirs, Las Casas worked as a jurist, but also as an anthropologist. During the Valladolid controversy, under the presidency of the Pope, it was necessary to determine whether the Indians had rights or not and saw two great theologians and jurists confront each other.

The first Sepulveda text is the most indienophobic text of the time, responding to the status of the indigenous and conquered peoples.

« Let us compare these qualities of prudence, character, manageability, temperance, humanity and religion (of the Spaniards) with those of these hommelets (humunculi), in which there are hardly any vestiges of humanity, which not only lack any culture, but are not even used, Neither knowledge of the alphabet, nor do they preserve monuments of their history, IF it is not some vague, obscure and blind memory of a few facts recorded in a few paintings, which are devoid of any written law and have only barbaric institutions and customs. And about their qualities, if one asks about their temperance and gentleness, what can one expect from these men who are given over to all kinds of passions and who, for some of them, do not hesitate to feed on human flesh (...). ) As for the fact that some of them seem to have a certain talent, as shown by the building of certain works of art, this is not an argument in favour of any human prudence, since we see certain creatures such as bees or spiders doing what no human industry manages to imitate [...]. I referred to the customs and characters of these barbarians - what then of their unholy religion and the odious sacrifices that characterise it, since worshipping the devil as gods, they do not believe they can appease them with better sacrifices than by offering them human hearts? »

This text dates from 1547 and was written by Sepulveda and deals with the just causes of the war against the Indians. It is the first great text of reflection on the nature of the Amerindians. It is a text representative of those who would reply that the Indians in the new empire in the making have no rights. It is possible to divide this text into three parts.

- Basically, what Sepulveda tells us, the central argument of this part is that these peoples have no culture because culture is a culture based on the written word, on history and on laws. In other words, Sepulveda has a Eurocentric definition of culture. A civilization or culture can only be called culture or civilization if a community has written laws, has a history, has monuments, has a relationship to its past that is the same as "ours". This type of argument is today reflected in the idea of the superiority of culture over others. The referents are often referents that refer to Sepulveda.

- They are not men, but animals because they are men who are not endowed with reason and given over to their vile passions and because they are given over to their passions are like animals who have no reason. There is a double logical transition: Indian peoples are beings of passion, animals are beings of passion without reason, and therefore Indians are animals. The equation between Indians and animals is linked to the absence of reason.

- The theologian's argument prevails over the jurist's argument, because there is only one culture, there is only one criterion to distinguish animals from men and there is only one religion which is the Christian religion to which the Indians do not adhere.

The other answer is given by Las Casas, which is a great answer to Sepulveda. This text is published in 1542.

« The men who inhabit these immense regions have a simple character, without malice or duplicity; they are submissive and faithful to their native masters or to the Christians they are obliged to serve: patient, quiet, peaceful, incapable of insubordination and revolt, of division, hatred or vengeance [...]. These peoples have a keen, prompt intelligence; they are without prejudice; hence their great docility to receive all kinds of doctrines, which they are moreover very capable of understanding; their morals are pure and they are found in such good and perhaps better dispositions to embrace the Catholic religion than any other nation in the world.... [...] »

It is the exact opposite of Sepulveda. The Casas, in a very Indianophile text, defends the human status of Indians who have the capacity to understand and learn. By saying that their morals are pure, it responds to Sepulveda, who made Indians into animals somewhere because of the impurity of their morals. The religious argument is invoked to justify his position making Indians capable of embracing the Catholic religion.

The Middle Way was proposed by Vitoria, who in 1539 published a founding text on modern empires entitled "De Indis". It is possible to see the synthetic dimension of this text.

« For, in all truth, they are not mad, but they possess in their own way the use of reason. 1. For they have a certain organisation in their affairs, since they have cities where order reigns; they know the institution of marriage; they have magistrates, chiefs, laws, works of art; they trade. All this presupposes the use of reason. 2. In the same way, they have a kind of religion [...]. If they seem so stupid and obtuse, I think that this is largely due to a bad and barbaric education; for we also see many peasants who are hardly different from animals [...]. From all the above, it follows that, without doubt, these barbarians had, like the Christians, real power, both public and private. »

For Vitoria, they are men because they are rational. Amerindian culture is certainly different from European culture, but it is not as different as Sepulveda claims, and they also know the institution of marriage, which from a legal and theological point of view was an important sign of European culture as a kind of referent.

In the second part two important elements emerge. They are not animals because they are endowed with reason. They are men who have both public and private power, in other words, they have rights. This will make Vitoria a defender of the property rights of indigenous peoples.

Is there anything in common between these three authors? All these authors have a clear awareness of the diversity in which Amerindian cultures evolve. However, they always reason in European terms using Eurocentric language. Philosophically or theoretically, they use European categories to define Amerindians.

In these three texts, an old division that comes from Roman law between free men and slave men appears. For these authors, the world is divided between free men and slave men. There is also the opposition between civilised peoples and between barbarian peoples irrigating, draining all imperial conceptions until recently. Until the 1970s, the great treaties of public international law began by dividing the world into civilised and uncivilised states. The division between civilised and uncivilised states still exists today. This theorising continues to permeate our way of thinking. The third category that allows us to think about the relationship between Amerindians and Spaniards is the relationship between believers and infidels. All these authors understand the world through the prism between believers and infidels. These conceptual categories will be found in the international legal order until very recently.

What is the legitimate authority? Who has sovereignty? The "bubble inter caetera" answered the question in 1493 because it had given Portugal and Spain jurisdiction over the newly conquered lands, but it had not answered the question of whether the right of ownership applies, who has sovereignty, who is the sovereign, who has dominus mundi. The Germanic emperor will have declared himself dominus mundi just like the pope, but who holds it then?

Vitoria will send back both the emperor and the pope in "De Indis" of 1539:

- the emperor does not hold the dominum mundi;

- the pope does not hold the dominum mundi;

- there is no right of discovery strictly speaking, nothing can legitimise the taking of possession by the Spaniards. In other words, there is no right of the first occupant;

- Vitoria accepts and recognises the need to spread Christianity;

- Vitoria rejects the idea that the New World was given to the Spaniards by the will of God.

Vitoria has an extremely strong spirit of synthesis, it proceeds summarily by presenting these arguments, which it then develops :

- 1. the emperor is not the master of the whole world.

- 2. even if he were master of the world, the emperor could not take over the provinces of the barbarians, nor institute new masters, nor deposit the old ones, nor collect taxes.

- 3. If we speak properly of civil sovereignty and power, the pope is not the civil or temporal master of the whole world.

- 6. The Pope has no temporal power over the barbarians of India, nor over other infidels.

- 12. If the barbarians are invited and exhorted to listen peacefully to the preachers of religion and if they refuse to do so, they are not excused from mortal sin.

When Vitoria published "De Indis" in 1539, he wanted to send the emperor and the pope back to back to propose a new vision of the empire. He accepted the idea that the Indians were men and therefore had natural rights. One of the essential rights is the right of ownership. What is at stake, since it is a fact that the Spaniards are conquering the New World, which one is it? Vitoria notices that the Spaniards are conquering, killing and plundering part of this continent. The question now is what are the possible conditions for entering into war and what are the conditions for a just war. If the Spaniards or any colonisers have rights, what are they? Can they act through war? Under what conditions can war be waged to conquer the world? Are there criteria of just war that allow or do not allow the conquest of the world?

The third conception of empire that is emerging in Europe is accompanied by a real reflection on war and more precisely on just war. The entire imperial vision that would take shape from 1550 onwards is accompanied by a vast reflection on war that accompanies the conception of Roman imperial ideology. Among the Romans, the question of justice and the righteousness of a war comes with Christianity. In Christian doctrine, in the order of reflection on war and peace there is the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus Christ explains the doctrine of non-resistance of Christianity. The Sermon on the Mount is an important benchmark in Christianity's relationship to violence. The doctrine of just war was born in the context of finding a formula that would allow Roman citizens to wage war without denying their romanticism.

Vitoria develops the argument « if the emperor is the master of the world" as a first answer. The emperor is not the master of the world for at least three reasons ». Indeed, there can only be a right under natural law, divine law or human law. Now, let us show this, « the emperor is not master of the world by virtue of any of these rights ». By virtue of these three rights, the emperor is not the holder of dominium mundi. The emperor is not master of the world by virtue of divine, human and natural law.

The second answer « Even if the emperor was the master of the world, he could not take over the Indies ». Let us suppose that the emperor is the dominum mundi, he could not take over the Indies. It is a very clear will to remove the emperor from any territorial claim on the Indies.

An argument that is absolutely essential to the whole imperial ideology is affirmed: "Those who attribute to the emperor power over the world do not say that he has a power of possession over it, but only a power of jurisdiction. But this does not authorise him to annex provinces for his own personal profit, nor to distribute fortresses and even land as he pleases". In a very harmless way, Vitoria tells us that even if the emperor had territorial claims, he could only invoke "juridictio" or "imperium", but not "dominium".

The Romans distinguished "imperium" or "juridictio", which is the equivalent of sovereignty from "dominium", which is the power of ownership. The emperor is not the holder of both property and sovereignty at the same time because a distinction must be made between the two. This will have major consequences from the sixteenth century to the twentieth century.

The great European empires that are being built on the rubble of the papal vision and empire will be different, offering different models of empire. Grotius will propose a model of the international order that will allow the great European empires to take root and find a legal basis and justify their expansion.

Vitoria is the first jurist and theologian to question the limits of the papal-imperial model from the Spanish imperial model, questioning the Pope's competence in matters of dominium mundi and the Emperor's competence. It opens a third way for the great European empires that are being established. Vitoria will open the way, but it will be up to Grotius to refine it, to finish it and to propose a theory of international order very favourable to European empires.

Vitoria rejects both the claims of the Papal Emperor and the German Emperor. Vitoria takes up the distinction made in Roman public law between dominium and imperium. Vitoria's second answer is « Even if the emperor was the master of the world, he could not take over the Indies ». It is a challenge to the vision of the imperial conception of the Empire by instrumentalizing the distinction between dominium and imperium, i.e. the power of jurisdiction and the power of possession. This distinction, which Grotius will take up again as a theorist of European empires, will serve as a basis for the Grotian vision.

Vitoria asks the same question about the pope, whether he is the holder of the dominium mundi, whether the pope is the master of the world. The question is clearly asked, "Is the pope the master of the world? "he concludes that he is not. The first answer is that "the pope is not the temporal master of the world". For Vitoria, "the pope has a power that is ordered to the spiritual", thus explaining it as follows: "This means that he has temporal power in so far as it is necessary for the administration of spiritual things". It is clear that Vitoria takes over the papal competence resulting from the Worms Concordat, which left the Pope the competence to manage the goods of the Church, which Vitoria assimilates to a temporal power.

On the other hand, it limits the intrusion of spiritual power into temporal power. In support of its point of view, Vitoria posits that « lhe pope has no temporal power over the Indians or other infidels ». This is a rather strong statement. In other words, newly conquered populations and newly conquered lands do not depend on the authority of the pope. There is no Church property in the newly conquered territories, so the pope cannot claim any jurisdiction over them.

The ius ocupacio or right of discovery or right of the first occupant is a right that has been debated in Europe since the 12th and 13th centuries, not so much for the territories of the Amerindians but for certain European territories that are not occupied or only slightly occupied. This question concerns, from the 13th century onwards, lands in northern Poland, and the question is whether the fact of occupying these lands or discovering them gives the person who first plants his flag a legal basis. It is a question that already emerged in Europe in the 13th century for European territories that are currently in areas of the Ukraine. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy had discovered them and the question of jurisdiction arose.

Vitoria wondered whether there was or is a right of discovery and whether this right gives rights. He asked whether under jus gentium there is a right of discovery concluding that in theory there is, but in practice this right cannot be invoked to occupy Amerindian lands. The reason is simple since he has decided whether they are men by the affirmative. Therefore, if they are men, they have rights and it is not possible to invoke a right that is superior to individual natural rights, including the right of ownership. It is consistent in its logic, recognising the possibility of invoking the right of discovery in certain regions of the world in theory, however, in practice, in the context of the conquest of the Indies, it is not invocable, because the Indians are men, they have property and they own their goods and their land.

In the third part of the book, Vitoria titles "Legitimate Titles of Spanish domination over the Indians". This is an interesting thing. The first two parts aim to reject papal or imperial claims and the third part aims to delimit, define and clarify the legitimacy of the Spanish adventure. Do they have the right to discover the Americas, to claim dominium or imperium over these lands. In other words, what is the applicable law as it stands? This part shows that man is much more ambiguous. Man is going to open a breach with terrible consequences in the justification of the European imperial adventure.

The contents of this section speak for themselves. The second paragraph reads: « Spaniards have the right to go and stay in the territories of the Indians, but on condition that they do not harm them, and the Indians cannot prevent them from doing so ». This paragraph is ambiguous since Spaniards have the right to conquer and occupy the newly conquered lands, and above all, others cannot prevent them from doing so. The fourth paragraph also speaks for itself: « It is not permitted for barbarians to prevent Spaniards from participating in the goods that are in their territories and that are common to citizens and foreigners ». Vitoria aimed at gold and precious metals which are common to everyone.

All of Vitoria's ambiguity can be seen in the introduction of the jus comunicatio, which is the right of society and communication. It is on the basis of this right that the Spaniards have legitimate titles to these newly conquered lands. What is the legal basis that allows the Spanish to conquer and occupy the newly discovered lands? « Spaniards have the right to go and live in India ». For Vitoria, it is a fundamental right to move.

The ambiguity arises with the second principle that justifies the conquest of the Spanish: « The Spaniards have the right to trade with the Indians ». This is an extremely clear affirmation of the right to trade. It is because they have the right to trade with the Indians that the Spaniards can occupy, conquer and expand. Trade is a very important element because the right to trade will become a leitmotif of the great jurists who founded jus gentium. The right to trade is an inalienable and fundamental right. To make it a fundamental right implies that those who do not respect it are liable to be subjected to war. In other words, if a certain number of fundamental rights are not respected, States, the entities responsible for maintaining and respecting these rights can attack for this.

In addition, for Vitoria : « Spaniards can participate in public goods » asserting that « If the barbarians have goods in common with citizens and foreigners, it is not allowed for the barbarians to prevent Spaniards from participating and enjoying them » implying a pretext for war. The title of the work speaks for itself « LThe lesson on the Indians and the law of war ». It is a logic of establishing Spanish property titles and in a logic of setting up the conditions for making war. Failure to respect a number of such things as the right to trade or to participate in public law is a just cause of war.

Vitoria's fourth answer is that « Spaniards can acquire a right of citizenship in India ». They may very well be citizens of the territory they have conquered, opening the door to the sharing of sovereignty by the colonists. Vitoria's fifth answer is that "In case of hostility from the Indians, the Spanish can defend themselves by war". There is no longer any ambiguity in this answer: « Let us suppose that the barbarians want to prohibit the Spaniards from doing the things that have been said above that are allowed to them by the law of nations, such as trade and the other activities we have been talking about. The Spaniards must first avoid scandal by using wisdom and persuasion. They must show all kinds of reason that they have not come to harm the Indians, but that they want to be welcomed and live peacefully without harming them. And they must not only affirm this, but also give proof of it, according to this word: it is fitting that the wise should first test all things by words. If the barbarians do not want to accept the reasons given to them, but if they want to resort to violence, then the Spaniards can defend themselves and do whatever is necessary for their safety, because it is permitted to repel force by force. Moreover, if they cannot obtain security otherwise, they can build citadels and fortifications; and, if they have suffered an injustice, they can, on the decision of their prince, punish it by war and exercise the other rights of war. ».

The fate of the so-called "indigenous" populations was sealed, because the just motives for war are clearly stated. Vitoria opened a major breach that the papal or imperial conception had never addressed, which was the contribution of a discourse on the right of conquest and the conditions of the right of conquest, and more precisely on the conditions of a just war. This is a new element that is not found in the traditional imperial Germanic conception nor in the papal conception. In other words, until Vitoria there was little or no reflection on war and the right of discovery. It was the reflection in Vitoria that gave European ideology a new character and scope.

Vitoria's ambiguity evaporates when Vitoria says « Spaniards can subdue Indians ». The ambiguity that was perceived and detected at the beginning is no longer at all de rigueur : « If the Spaniards have tried all means and if they can only obtain security from the barbarians by taking over their cities and subjugating them, they can also do so legitimately ». The tone was set. This sentence is crucial because Vitoria opens the way to a much more aggressive vision of great empires. Conquest was an important part of the Roman Empire, but Rome, in the opinion of Roman historians, did not show aggression or conquest of the world. Rome never had any claim to world domination. Papal and imperial conceptions were not built on an aggressive vision of world order. It is a process of securing the emperor's competences or securing and protecting the pope's competences. With the discovery of the New World, the new model of empire and the new conceptions of empire that are emerging are much more ambitious and conquering. It is clear that the concept of empire is evolving in a much more expansionist direction.

Vitoria's seventh answer is that « the Spaniards can exercise all the rights of war against the Indians ». It is implied that the Spaniards are entitled to intervene if the Indians do not respect a number of natural rights.

The first part somewhere enumerated the fundamental rights in the international order, namely the right of discovery and the right to trade. The second part introduces another right which is the right of evangelization. This is a major contribution from Vitoria, which is a reflection on the right of evangelisation as a right that is part of and can be invoked by the great European empires in the making: "There may be another title: the expansion of the Christian religion". The first answer is that Christians have the right to evangelise the Indians.

The second answer is that "The evangelisation of the Indians was entrusted especially to the Spaniards". This will be contested by Grotius as a Protestant who will not understand at all why the Spaniards have a monopoly on evangelisation. The third answer is that "This evangelisation excludes the use of force". It is a right which is an invocable right, but which does not allow the use of war in order to impose it. The fourth answer removes any ambiguity which is that « Indians should not oppose evangelization ». If they do, they are liable to be the object of war. In other words, if they oppose it, it is a just cause for war for the Spanish and Portuguese Empire: « It is clear from this answer that, if the Spaniards cannot otherwise promote the cause of religion, they are also allowed, for this reason, to take over their lands and provinces, to create new chiefs, to depose the old ones and to do, under the law of war, what could legitimately be done in other just wars. But they must always act with restraint and moderation, so as not to go further than is necessary. They must prefer to give up their own right rather than undertake something that is not allowed. Finally, they must constantly orient everything to the good of the barbarians rather than to their own advantage ». The Indians have relatively little room for manoeuvre. In other words, if they refuse evangelisation, their chief can be changed, their provinces confiscated and all Spanish domination can be exercised without restraint. The right to evangelisation does not imply conversion limited to preaching. In other words, the Indians cannot be forced to convert, but they cannot prevent the Spanish and Portuguese from spreading the good word.

Vitoria postulates the following: « I have no doubt that the Spaniards were forced to resort to violence and weapons in order to stay there. But I fear that they went beyond what the law and justice allowed ». It is necessary that the European powers that conquer the world show restraint and respect a certain number of rights, which will become jus in bello.

It is clear that Vitoria is still trapped by two visions. In other words, it is clear that when you read Vitoria's text, it oscillates between two attitudes. An attitude that rejects the Pope's competence and the emperor's competence to leave the Indians control, ownership and sovereignty over their territory. In the third part, the introduction of a number of rights in the name of jus gentium such as the right to trade, evangelise and communicate opens the way to an expansionist vision of European empires. There is a tension in Vitoria between a man who is aware of the horrors of conquest, but who somewhere provides a number of legal arguments to justify it. This tension can be found in Grotius, who will present a model and a coherent imperial vision.

Following Vitoria, the empires in Europe were set up and began to conquer part of the world. The characteristics of the empires are different. The Spanish and Portuguese Empires do not correspond to the English Empire, which is much later. The material characteristics are different.

The European empires[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Portuguese Empire[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Portuguese Empire began to emerge at the end of the 15th century with the discovery of the India sea route in 1497. The Portuguese conquered part of South America, part of India with a number of trading posts, also in Africa, in the Arabian Peninsula with the occupation of the Strait of Hormuz, as well as islands such as Malaka, Java and Macau. Portugal will also occupy Brazil. It is an empire split with South America, some regions of South-East Asia, some African trading posts. It is an empire of trading posts built on the basis of a certain number of areas or ports, but it is not an empire that will penetrate inland. It is a maritime empire that is essentially based economically on monopoly. The comptoirs are only allowed to trade with Portugal.

The empire is not going to last very long, falling apart very quickly because Portugal does not have the means to control its immense territories and its many trading posts. It is an empire that will become decentralised. The governors of the comptoirs would soon have a great deal of authority and a series of important competences.

The Spanish Empire[modifier | modifier le wikicode]