Trade and geographical advantages

Previous courses have questioned us on what explains the expansion of circuits, which explains that flows begin to cross borders, which explains what goods, tangible and intangible goods cross greater distances, why we have not remained to micro-local circuits as analyzed by Sahlins and Chaunu. There is a mystery in the phenomenon of expanding economic circuits.

There are different economic circuits, each with its own regulation system corresponding to different space systems, and there is a history of their expansion. The history of economic enlargement, the colonisation of the free trade triangle and a very Eurocentric history. There remains a pending question which is how to explain the expansion of the circuits? What and the factor and engine that pushed these economies to expand. The question is why open the circuits, why look for economic partners who are more and more distant? The question of distance arises with the idea that distance is both material and symbolic and that both distances are costly to travel. Physical distance is costly to travel until the transportation revolution has taken place. To cross the symbolic distance is costly and dangerous because there is no better way to protect one's identity than to refuse to exchange with others. The symbolic risk of trading with the other is risky because there is the risk of realizing that the other and myself, that he is not just another, but different. Another explanation is that the reasons for refusing to make a donation against donation or distribution with the other and for leaving another one otherwise he would no longer be another and we would form a community bound by debt. The market, the anonymity of the market, the instant satisfaction of the market aims that the other remains a stranger. In Sahlins' scheme, we hardly exchange with each other, also at Chaunu.

The material distance as well as the symbolic distance are very good reasons to refuse the distant exchange which is too dangerous, too expensive and too risky. This makes the answer to the question of how to explain the expansion of economic circuits all the more mysterious. Between the Paleolithic man or woman who lived from hunting and gathering and the Breton peasants in the 19th century who lived from agriculture and cattle breeding, the average number of kilometres of the economic circuits were the same.

There is no single answer, answers vary and vary according to three factors. What circuit are we talking about? 1] According to the places, the times, the types of circuits, the scales of the circuits, the reasons for opening these circuits are not the same. Depending on the players in these circuits, namely the producer, the consumers, they may have different but congruent reasons. The answers vary according to the reality of social and historical configurations. The theoretical apparatus[2] is at the same time the discipline, economists, anthropologists, sociologists and geographers do not have the same type of answer depending on the great paradigm of the theory[3] in which one is situated.

The first idea is that we distinguish two levels of explanation, namely what allows the exchange, namely the material component such as logistics and transport, and what motivates it to know why we invent means of transport that allow it to be moved. The hypothesis is that the logic of this motivation is ideological, even cultural. In geography, we not only explain why we are going to exchange with someone further away and why we choose one partner over another.

Non-economic explanations

Explanation to the expand circuits is not an economic explanation having nothing to do with profit. These explanations will be borrowed from the orthodox economy, but also from the economy at large.

The social link

The idea is that if you widen an economic circuit it is to create a social link with the distant and different partner that you integrate into your economic circuit. To reflect on this hypothesis, we must call upon game theory. Three types of games are considered: zero sum games, positive games and negative games. Most games are zero-sum games. A zero-sum game does not destroy or create wealth. Negative sum games go only at the end of the game, there is less money than at the beginning of the game, but in this case, what matters is the distribution of gains and losses. A positive sum game is a game in which there would be more money at the end on the table than at the beginning of the game. Games create wealth like positive sum games, games destroy wealth like negative sum games and zero sum games like zero sum games. The question is whether international trade is a positive-sum game, zero or negative? Does international trade create wealth, destroy it or change nothing? These three hypotheses can be found.

The problem is when international trade is a negative sum game, because the goal of trade is not profit. In the potlatch, all the wealth exchanged after the exchange is destroyed. This is proof that the purpose of the exchange is not in the exchange, but in the type of link that the exchange created. This explanation of the expansion of the exchange is very effective for redistribution and donation for donation channels that can go further to seek a partner to create social ties with him. Gift for gift implies and maintains primary social ties, the redistribution circuit sets up a community subject to a community. The authority that manages to expand the circuit increases its territory, the number of its subjects and the size of the community. Trade would be one way to continue the war by other means.

This may seem obvious for redistribution and donation for donation, but the market also works that way. The reason for the creation of the ECSC was not an economic reason, but to force the French and German partners to work together, to ensure that they knew each other, that links were created, that interdependencies were established and that a third world war was avoided. The market was instrumentalized, was the first step to create identity, international and diplomatic link.

The power

The social is never very far from politics and power. One can have a more negative and suspicious interpretation of this instrumentalisation of exchanges. The extension of the field of exchange has functions that are not economic, but these are no longer social functions aimed at creating bond, peace and symbolic proximity, but rather to consider that international trade is the continuation of war by other means by establishing the power of power and coercion. The gift is always a seizure of power just like the debt since one is debtor of the one who made credit.

The assumption is that the exchange does not produce wealth in a zero-sum game. If the game of international trade is a zero-sum game, if someone breaks this rule, it means there is a loser. If someone is delighted with international exchange, enriches himself through international exchange and promotes international exchange, it is equal and symmetry that someone loses money and power. From this perspective, international exchange is something dangerous because of losses, but since these losses are resolved in debt, the issue may be less in the negative economy of exchange than in the political dependence that exchange creates.

The risk of the exchange is in the situation of dependence in which it will put at least one of the two partners. This dependence is that of the debt and it is also in the fact that if we stop producing something and specialize in another field which is the guarantee of productivity gains, we become dependent on foreign countries. When this dependence is on energy or food, if imports cease to be provided, the very survival of the country risks being called into question.

From the mercantilist's point of view, this has two consequences. We must promote exports and reduce imports as much as possible: as soon as we export, we gain gold; when we import, we lose gold. Any import results in the impoverishment of the country in question. This solution is still optimistic in the sense that we think our country can win. If we think that is not possible, the only solution is protectionism. This idea was theorized by Litz who tried to propose a theory of protectionism. His argument is simple: England was the first nation to industrialize which allowed it to produce at low cost and good quality unlike France and Germany. British products were of better quality and cheaper than its competitors. In terms of competition, German industry had no chance of selling its production and developing. To guard against this risk and political and economic domination, Litz proposed closing borders to allow development in countries that were less advanced. That is the idea that there are times when we have to protect the national economy simply because it is not competitive.

The great promoters of free trade were England and the United States, which are the two countries that have successively dominated international trade. In the economic war that is international trade, it is the strongest that dominate. Countries that do not have the same productivity and do not offer the same products must close themselves off from international trade to avoid impoverishment and to prevent their industry from being locked into a primitive phase. There is always someone who benefits from the exchange, the exchange is always to the detriment of one of the two partners. The question is who imposes the prices and conditions of the exchange. In the exchange one partner is more powerful than the other and is able to impose his conditions. Exchange tends to increase inequality because it will contribute to the enrichment of the richest country and the impoverishment of the poorest country. On several occasions, international trade has been used as a means of exerting pressure. One example is the embargo on Cuba and the embargo on wheat imposed by the United States on the USSR following the invasion of Afghanistan. This mistrust of international trade and the dangers it entails legitimizes withdrawal and protectionism and also legitimizes block effects. This encourages exchanges with countries in which we have some confidence and distrust of those who are hostile. There is a link between political, cultural and social identity and enlargement. There is mistrust in the economic unions of the partners.

The pursuit of profit

The neoclassical model of the homo oeconomicus is the one that aims to maximize its profit and utility. International trade theory is one of the few non-trivial and fair economic theories. What Samuelson meant was that either the theories were trivial, but according to him there was an example which was non-trivial and relevant which was Riccardo's comparative advantage theory.

Smith: specialization and absolute advantage

The idea is that the more you specialize, the more you increase productivity. Between two countries that do a little bit of everything wrong and consume what it produces[situation A], two countries that specialize in a field and exchange their production[situation B], situation B is better: thanks to the production gains gained by specialization, total gains will increase.

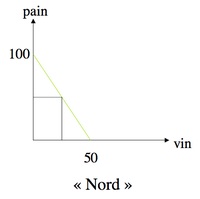

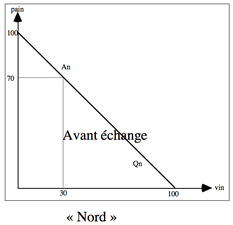

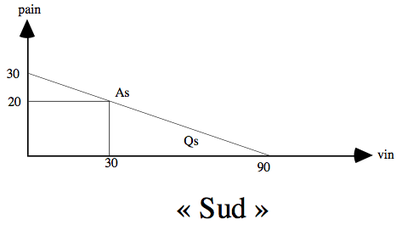

Two countries, North and South, produce only wine and bread. Only bread and wine are produced and only bread and wine are consumed. Resources are fixed in terms of land, capital, labour, machinery.

Resources are allocated to produce the quantity 25 of wine and 50 of bread. If we want to produce 100 loaves of bread, we must allocate all resources to bread production and no resources to bread production. Conversely. The green line represents resource allocation opportunities. The "North" country has the choice of using all its production to make bread or wine.

The differences between the North and South countries have climate as a difference. The northern country has an absolute advantage in producing bread since by allocating its resources to bread production, it can produce 100, while the southern country has an absolute advantage in producing wine since by allocating its resources to bread production, it can produce 100. Both countries have the same size and the same amount of resources, the ideal solution is for each country to specialize in its absolute advantage. Each country will have to import and export to sell what it cannot consume and import what it cannot produce.

The quantity of 100 is the maximum quantity that maximizes the usefulness of the resources. Whatever other point is chosen, the total will never exceed 100. The maximum amount of wine and bread was produced.

For every production in the world, a country has an absolute advantage. According to Smith, each country should specialize in the field in which it is better than all others and abandon other productions. In this field where he is better than all the others, he will export most of his production, with the money earned, he will import the products he needs. Specialization produces an improvement in productivity. Any country that has an advantage in an area can participate in international trade and make a profit. The fact that one country does not have an absolute advantage and therefore cannot participate in international trade is a problem for that country, but also for other countries that cannot enjoy their absolute advantage because there are markets that are closed to them.

Ricardo: the comparative advantage

With Ricardo's theory, one country, the North, is better at producing both productions. The country of the North has two absolute advantages in the field of bread and wine, while the country of the South has nothing. Since the southern country is less good in both areas, it is difficult to see how an exchange could be made between the two. Under Smith's absolute advantage model, it is hard to see how international trade could get off the ground.

When we compare two comparative advantages, it is between two countries and between two activities. Any country has a comparative advantage because it is the area where the difference between productivity and that of the competitor is the best. There is one area where the difference is huge and one area where the difference is less. The comparative advantage compares two producers, two countries and two productions. By definition, every country has a comparative advantage. Any country, even the worst in the world, can participate in international trade because there is a production where it is a little less bad than the others. Every country in the world has the opportunity to participate in international trade.

If one balances the two theories that exchange creates wealth with Smith and Ricardo's theory, all countries can enrich themselves. Every country has a field in which it has an interest, to specialize in stopping other productions and exporting as bad as it is. With the money he will earn, he will be able to import what he has stopped producing, in total, at the end, production and consumption will have increased creating growth. Any country that participates in international trade experiences growth: this is the total increase in production, consumption, income, life expectancy, and everyone can participate. This theoretical idea has not been invalidated.

According to Ricardo's theory, opening trade is a very good idea because it will eradicate poverty in the world. This will produce wealth, because any country that participates in international trade becomes richer. Ricardo does not describe globalisation, does not justify it in retrospect, he is the reason why there is globalisation. It is because we believe in Ricardo's theory that we are implementing globalization. It is very important to say that Ricardo's theory has not been invalidated.

We must reason not as a comparative advantage of countries, but in terms of comparative advantage of firms. If Ricardo is not theoretically invalidated, he is totally empirically invalidated. No country has totally specialised in one sector, all the countries in the world have kept a certain diversity in production. The answer is that diversity is counterproductive and meets other objectives such as the argument of food self-sufficiency. We are in a difference between a realistic epistemology that describes how things are done and a theoretical vision. Recently, another element of criticism has been opposed to Ricardo's theory and to the development of international trade, which is the two-pronged ecological issue of transport [1] that translates into a huge energy cost, but also a cost in terms of ecological borrowing, in ecological terms, a diversified economy is more fragile [2]. Ricardo's theory is not about profit sharing. To the question of how wealth is shared, the answer is not necessarily economic, but it can be political. If we can accept that globalization produces wealth, we must ask ourselves where wealth goes. If one finds an impoverished partner in the exchange, it does not invalidate Ricardo's theory, which would invalidate Ricardo's theory is that three quarters of the partners have not become rich. A distinction must be made between global enrichment and individual enrichment. There is no doubt that global production has increased, there has been growth, but that does not mean that all countries are getting richer.

What comparative advantages

As a geographer, we must ask ourselves how wealth is shared, what is the nature of these absolute advantages, which country has what advantage, is there a geographical logic, are there distribution models? We need to look at the nature of flows in order to look at the reality of trade between countries.

Many of the early economic exchanges were for products that one of the two trading partners was unable to produce. An exchange of unavailability is when one of the two countries imports something because it is unable to produce it. An exchange of unavailability involves natural resources because what defines a natural resource is that it cannot be produced. The absolute advantage is very clear: one has the resource or one does not.

With oil flows, we either have resources or we don't. The arrows go from countries that have deposits to countries that do not. Yet it is also important to have significant resources and to import them like the United States.

This map reflects a geology of oil basins and consumption areas.

Exchanges of unavailability do not only concern natural resources. There are things you can't produce because you can't or because you can't produce them. For products with very high added value, very technical products, you need very complicated machines, very well trained people and know-how. This highly skilled workforce is not everywhere. Just as there are pools of natural resources, there are pools of skilled labour and skilled labour. Basically, high value-added industries of very high technology cannot leave the grey matter basins. Very high-tech industries will remain in certain basins. Just as the oil well must remain on the oil basin, the very high-tech industries will remain on the grey matter basins. The most profitable productions are those based on these deposits. In a sense, we are faced with unavailability exchanges, because many countries do not have the skilled labour to produce technical goods with high added value. The issue of very high qualifications applies especially to the invention and early life cycle of countries. The problem of grey matter deposits is not about the production of something, but rather about innovation. A third factor of the exchanges of unavailability will intervene which is the question of patents. These are situations where unavailability is maintained by production patents.

For certain products, for always specific reasons, certain places manage to acquire a monopoly. The only country capable of exporting its films all over the world is the United States with Hollywood. Films are governed by an exchange of unavailability. With the question of exchanges of unavailability, there is an explanation for a whole series of flows that are not necessarily raw material flows.

Ricardians and neo-Ricardians: HOS, product cycle, demand

Ricardo does not deal with the absolute exchange which is an exchange of unavailability, but deals with comparative advantage. In Ricardo's theory, we export what we specialize in and import what we give up. For Ricardo and for Ricardians, the choice of specialization and therefore of exchange, of a direction of exchange and international flows depends on the countries' predispositions before the exchange. What are these country predispositions?

For Ricardo, the answer is simple, what counts is the unit of work. He reflects on productivity differentials that he calls "labour value". How do we explain the difference in labour productivity between the north and the south? A first set of factors would be natural resources. Another assumption is that comparative advantages are linked to certain particular qualities of the companies in question. Nevertheless, there is a risk of reasoning according to a tautologism. Samuelson, for example, postulated that the advantage of tropical products to produce tropical products and tropicality. We should rather ask ourselves what tropicality is, what is the quality of a society that makes it less disastrous or better than others in a production.

This outstanding issue is the question of explaining comparative advantage. If it has not been asked by Ricardo, economists will try it.

The first model is the Hecksher-Ohlin-Samuelson model. All countries have three types of factors, namely land, capital and labour. In other words, land is linked to the size of the country, capital is linked to its wealth and work is linked to its labour force. Each country has a particular configuration. For each production, these three factors are needed. Just as these three factors are present in all countries of the world, but in varying proportions, these three factors are necessary for all productions, but in varying proportions. For each production, a percentage of these three factors is required. The best thing is for a country that has a certain proportion of factors to choose a production that corresponds to the proportion of factors that it values well. Predisposition is factor endowment. But where does the capital come from?

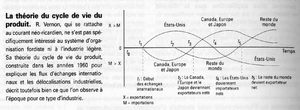

Vernon's theory is also called product cycle theory. Vernon is attentive to the link between innovation and industrial development.

Every product goes through three phases: an innovation phase [1] which is the moment when the product has just been created, a trivialization phase of the product [2], an obsolescence phase [3]. For each moment of the product life cycle, there will be a product that will take the initiative. This corresponds to factor allocations. The industry at different times of novelty or commoditization of products has as its natural place in different places of the world. Each of these moments does not produce growth in the same way. Innovation produces a lot of growth and spinoffs, it declines according to the phases.

Linder's theory presents the interest of changing perspectives because for him comparative exchanges are not linked to the quality of production, but he has consumption logics. Comparative advantages are demand-driven.

Ricardo's theory justifies free trade and globalization. This is a huge challenge for poor countries because it guarantees them access to the international market and the opportunity to enrich themselves. If we compare the map of exchanges with the theory of international exchanges, there is something striking: the major part of exchanges on a world scale are intra-branch exchanges which are configurations where exchanges are symmetrical bearing in both directions on the same products, on the other hand, rare are the specialized countries.

Increasing returns and comparative advantages

We will discuss two important challenges to the theory of comparative advantage. The first, which is the increasing returns and comparative advantages, is a challenge within the liberal economy model, but loosening a hypothesis of pure and perfect competition. The second pole of protest is outside the neoclassical economy in ways of working on the economy inspired by Marxist and neo-Marxist models under the name of alterglobalization.

The theory of comparative advantage seems to work very well then for what to look further for challenges or alternative explanations. While Ricardo's model seems theoretically very attractive, empirically and practically it seems to be contradicted by several realities concerning the development of international trade:

- Most trade is intra-industry trade: it is trade where two countries exchange only comparable goods, which is not compatible with the idea of comparative advantage and speciation as Ricardo predicts. Most exchanges are North - North exchanges and not North - South exchanges. There is more exchange between countries that are similar than between different countries.

- countries are far from specialising: the fact that large economies with a very liberal view of the market and the economy do not lose this specialisation tends to prove that there is something else.

Krugman's hypotheses, in particular, do not completely call into question the theory of comparative advantages, but allow us to look at it in a different way, whereas on the other hand, anti-globalization critics question the comparative advantage.

The problem of increasing yields

Paul Krugman is not a geographer, he is a geographical economist and part of the New Economic Geography movement. It is more a question of geographical economy than economic geography. Krugman is part of a practice of economic geography with figures and hypotheticodeductive models. We are not in a realistic epistemology, but in a normative epistemology. He was advised by the Democratic administration and won the Nobel Prize a few years ago.

Krugman will revisit one of the assumptions of the liberal model which is the assumption of pure and perfect competition. For the law of supply and demand to work to obtain an equilibrium price, a number of conditions must be met, including the condition of pure and perfect competition. States that support the market will implement laws to support this theory of pure and perfect competition. For there to be pure and perfect competition, producers must disagree on price and be equal in the confrontation of supply and demand. For Krugman, it doesn't work that way. It is always interesting after the model is built to introduce other factors to see what impacts they have on the results.

He will ask himself what is happening by reinjecting a factor wondering what is happening for pure and perfect competition when there are increasing returns. Increasing yields is a configuration where productivity is correlated with production. The production cost of marginal units is decreasing. The more you produce, the easier it is to produce the last unit produced. In economics, it is a system which prevails, the productions are generally characterized by increasing returns. This is not to say that increasing returns are infinite. The reason why all the world productions of a product are not concentrated in the same place is because at some point the yields become decreasing, i.e. the production of an additional unit will cost more. The curve is a bell curve with an increase in yields has reached a certain level, yields are decreasing.

As soon as there is a situation of increasing yields, this means that large producers have an advantage over small producers. By spreading the savings produced from the production of marginal units over the whole production, large producers can put goods on the market at lower prices than small producers. So we buy products from large producers, not small producers. The situation of competition between large and small producers is not pure and perfect.

The problem is that you don't become a big producer instantly. The question of increasing returns is that of time. It is a production that will increase until it reaches the threshold where yields become decreasing. Competition is pure and perfect as long as you keep your prices low enough. The conditions for a producer to appear on the market and compete are related to competition, diminishing returns and the cost of market entry. A new producer entering the market will have to invest at a loss for years. There are situations where no one can enter the market because of increasing returns. These are situations conducive to the cartel situation. This mass production advantage is linked to the early market entry of the first producers. Increasing yields lock in comparative advantages over time. According to Krugman, productivity is good in products that produce a lot and for a long time. Because of time lockout, increasing yields are not only an advantage for large producers over small producers, but also for older producers over new producers. Countries that specialized relatively early in a product, that experienced the Industrial Revolution relatively early, that were able to produce en masse and cheaply, flood international markets with cheap products stifle the potential development of countries that later woke up. In addition to a question of speed, there is a question of acceleration since the more you produce, the more formidable you are for the competition.

The countries that will have a comparative advantage are the countries that have started to produce before the others. For Krugman, the comparative advantage is early age. This means that we completely reverse Ricardo's model for which a country had predispositions for this or that production and, depending on the predispositions, it has a comparative advantage that will direct it towards specialization and export. For Krugman, it's the opposite. A country will specialize in a production, it produces massively, has increasing yields and acquires a comparative advantage over its competitors. At Ricardo, comparative advantage is the cause of specialization and international trade, while at Krugman, comparative advantage is the consequence of specialization and international trade.

For Krugman, there is also a lock in the comparative advantage space. Industrial development is contagious by a kind of spatial diffusion around innovation poles. There are phenomena of spatial concentration. The development effects will affect the more or less immediately surrounding space, but will not cross the entire country. The distance brake will spatially lock the comparative advantage. A place where industrial development began before the others will have because of the comparative advantage locked in time an increasing yield and a comparative advantage over the others and spatial locking will induce a tightened development around this place which will become an industrial region.

The locking of comparative advantage

There are a lot of problems with this theory. The theory of increasing returns sets up virtuous circles, but also vicious circles. For Krugman, "rich countries are rich because they are rich, and poor countries are poor because they are poor. Rich countries have experienced early development with increasing yields and preventing poor countries that have not yet industrialized from entering the market. It is very difficult for emerging countries to fight against the effects of increasing yields, against the effect of the accumulation of wealth in rich countries.

Krugman sets up a kind of fatality of development: it is in the nature of rich countries to be richer and richer by an accelerating effect and it is in the nature of poor countries to be poorer and poorer by the effect of deceleration and vicious circles. One criticism is that a slight inequality will widen a gap by accelerating. In the 16th century, on a world scale, there was no development differential, there was the same level of GDP for all countries. In the 17th century, a differential began to develop with the countries that experienced the Industrial Revolution. The induced gap was in its nature to widen because of increasing yields and the locking in time of comparative advantages. The wider the gap, the more reason it has to widen. There is a divergence effect. This system contradicts the idea of pure and perfect competition. Perhaps pure and perfect competition existed at the beginning, but if, as time went on, the difference created accelerated over time. Why comes a time when divergence sets in?

The problem with increasing yields is that it promotes a divergence between rich and poor countries. The second problem is that it was relevant to Ricardo's reasoning that there were ante-economic situations that constituted predispositions on which an economy could base itself according to its predispositions. It is a beautiful chain of cause and effect and deterministic, that is, each effect is linked to a cause. For Krugman, whatever the sector in which we specialize, thanks to the increasing yield, we will gain an advantage over the competition. The reason why we have become the best is not related to predispositions, but to early initiative. Whatever the sector in which a country specializes, it will succeed if it specializes faster than others.

History vs. anticipation

These two consequences are two problems because it is very unsatisfactory for the mind to arrive at tautologies. On the other hand, it is frustrating not to explain why a country has specialized in a field. Krugman will try to find an explanation. He'll find two explanations:

- historical explanation;

- effects of anticipations.

He developed an example through the story of Catherine Evans. In 1895, Catherine Evans Whitener gave her sister-in-law a bedspread. In 1900, she sold a bedspread for $2.50. In 1917, she founded the Evan Manufacturing Company in Dalton. Will create a lock in time and space of comparative advantage. In 2002, 80% of the American carpet market was supplied by spinning mills less than 100 kilometres from Dalton in Georgia, creating a development centre. It's a story with a small cause and bigger and bigger effects. There is a disproportion between effects and causes because there is an effect induced by increasing yields. These explanations are not. These are phenomena that refer to the theory of chaos, i.e. moments when it is difficult to ascend from a present situation through cause-effect links through a triggering element. Without doubt, for all the major industrial regions, it is possible to find an element that made it start. All these elements that are given are necessary, but not sufficient conditions. This is what Krugman calls the historical explanation.

Explanation by expectations would be self-fulfilling prophecies which are an assertion which induces behaviours likely to validate them, i.e. a statement, a description, an assertion which one believes to be true which will induce behaviours which tend to make it true. These are moments when you think you're describing reality while you're making it. In other words, these are times when you think you are describing a situation while producing it. Self-fulfilling prophecies have been much studied in the case of economic crises that are often based on self-fulfilling prophecies. In some cases, prophecy is only fulfilled because it has been announced.

Anticipations have an effect on the future. In a way, the future is the cause of the present, because it is expectations that construct reality. Not all prophecies are self-fulfilling, there are also suicidal prophecies. Without doubt, all our expectations have an effect on the future. Our projections do not describe our future, but help to determine it. Our vision of the future plays a role in what happens to us. Some countries would at times have had a vision of the future and have embarked on a vision that has come true, while in other cases it has not.

The two scandalous explanations proposed by Krugman, the first, which is the historical explanation, is scandalous because there is such a disproportion between causes and effects that we cannot be satisfied with it, and the second, which is also scandalous because of expectations, not really because of a disproportion, but because of the idea that it is basically random. The two explanations are not contradictory. We are not in a configuration where we seek to explain the economic success or failure of predispositions, but seek to explain by the action of the actors. With this approach, we remain within the framework of neoclassical thought and Ricardo's theory.

(Neo)Marxist and Alterglobalist Contestations

If international trade is not a positive sum game, then there are reasons to be wary.

Critiques marxistes et néomarxistes

Les théories de l’impérialisme de Luxembourg et Lénine sont l’idée que la lutte des classes qu’on observe à l’intérieur d’une société se reproduit à l’échelle internationale. Tout comme dans une société, il y a des bourgeois, des ouvriers et des prolétaires, à l’échelle internationale, il y a des États bourgeois et des États prolétaires. La captation du profit opéré par la bourgeoisie à l’égard du prolétariat se retrouve à l’échelle internationale entre États bourgeois et États prolétaires. Typiquement, cette dimension de l’impérialisme s’opère dans le cadre de la colonisation. Le rapport des colons aux colonisés est de la même nature que le rapport des bourgeois aux prolétaires qui s’exprime dans l’impérialisme dialectique et dans l’appropriation des moyens de production. Cette interprétation est en termes de pillage des ressources dans le cadre du commerce international.

Cela n’a pas de sens de parler de nation prolétaire ou de nation bourgeoise. Toutefois, on image qu’on pourrait expliquer l’enrichissement de la bourgeoisie européenne par l’exploitation d’une main-d’œuvre servile dans les colonies comme avec les grandes bourgeoises des ports côtiers de la France ou d’Angleterre qui se sont enrichies sur le commerce du « bois d’ébène » et des plantations. Dans ce cas, il y aurait une bourgeoisie européenne qui se serait enrichie par l’exploitation des prolétaires fondées sur l’idée d’une « race » différente. Il important d’avoir cela en tête lorsqu’on réfléchit sur les querelles à propos de la délocalisation et qu’on essaie d’interpréter en terme marxiste ou de « gauche ».

La deuxième théorie est la théorie de la détérioration des termes de l’échange. Il faut plutôt parler de l’hypothétique détérioration des termes de l’échange parce qu’il y a une littérature vaste qui fait débat. Les termes de l’échange sont les prix relatifs des matériaux exportés et importés. Les produits manufacturés fabriqués par les pays riches et industriels ont tendance à être de plus en plus chers alors que les matières premières, les ressources naturelles et les productions des pays du sud ont tendance à être de moins en moins chères. Autrement dit, il faut que les pays pauvres exportent de plus en plus pour importer la même quantité de produits alors que les pays riches en exportant la même quantité peuvent importer de plus en plus. Pour les pays pauvres, il y a une détérioration des termes de l’échange. Les importations des uns ne permettent pas de payer les exportations des autres creusant le déficit de la balance commerciale des pays du sud et réduisent leur possibilité pour investir afin de se développer.

La théorie de la détérioration des termes de l’échange présente un intérêt dans la mesure où elle laisse entendre que la fixation des prix peut dépendre d’autre chose que des mécanismes de l’offre et de la demande et présente également des effets de pouvoir. Elle présente un autre intérêt parce qu’elle remet en cause l’idée qu’il y aurait un juste prix. Il y a l’idée que pour les ressources naturelles, il est très difficile d’en établir le prix, on peut établir le coût d’exploitation, la demande, mais il est très difficile à prendre en compte le coût de leur disparation. Il est difficile à comptabiliser le fait qu’on prive les générations futures de la possibilité d’en disposer.

Le troisième volet de ces théories marxistes et néomarxistes mis d’abord en place par Amin et Wallerstein est qu’on peut revisiter la théorie de l’impérialisme en termes de rapports de dépendance. Les anciennes puissances coloniales, les pays de la triade avec l’Amérique du Nord, l’Europe occidentale et l’Asie de l’Est en particulier le Japon, constituent des centres dans une économie qui polarisent les flux et monopolise les profits au détriment d’une périphérie plus pauvre auxquels est abandonné des productions d’un moindre intérêt économique ou sont des zones exclusivement de prélèvement des ressources et entre les deux les échanges sont inégaux. Il y a une interprétation géopolitique et économique de ces rapports qui met en balance l’accumulation de richesses dans les centres en comparaison des périphéries. Il y a une charge lourde avec l’idée que les indépendances puis le commerce international n’ont pas mis fin à ce qui serait un pillage colonial, mais la poursuivit sous d’autres moyens.

Plus récemment est apparue la théorie de la nouvelle division internationale du travail. Cette théorie consiste à dire que les avantages comparatifs, la théorie de Krugman, explique la spécialisation participation de chacun au commerce international, mais que les spécialisations ne se valent pas toutes. Il y a des spécialisations qui sont intéressantes économiquement, socialement, et politique donnant du pouvoir permettant de dégager beaucoup de profit, d’investir davantage et qui ont des effets positifs importants en termes de diffusion et de multiplicateur d’emploi. Il y a d’autres choix économiques qui sont moins heureux parce qu’ils procurent moins de pouvoir, permettent de faire moins de profit et puis leurs effets collatéraux sont peu nombreux et limités ayant un impact local faible sur les possibilités de développement.

Parmi les activités de la première catégorie, il y a les activités à haute valeur ajoutée et à haute technicité qui ont des effets induits importants, c’est-à-dire que ce sont des moteurs de développement. Ces activités connaissent de effets multiplicateurs qui font qu’un emploi créé dans les hautes technologies va nourrir toute une chaine d’emploi en aval et en amont avec un effet très positif sur la croissance. Ce sont des activités très qualifiées, innovantes qui produisent de la plus-value et de la croissance, elles ont un impact écologique faible permettant de maintenir une qualité de vie importante. De l’autre côté, il y a des activités plus lourdes plus tournées vers des produits matériels que sur l’information qui abiment et exploitent beaucoup l’environnement et polluante faisant appel à une main-d’œuvre peu qualifié se livrant à des activités répétitives avec peu d’effet sur l’innovation, qui est fragile dégage peu de plus-value, de profits et a un effet multiplicateur faible et peu d’effet sur le développement.

L’idée est que la répartition des deux types d’activités ne se fait pas par hasard, mais que les pays du Nord et de la triade ont confisqué les activités les plus lucratives et qui nourrissent le plus de développement et ont abandonné aux pays pauvres et aux pays du sud les activités les moins intéressantes sur le plan économique et les plus nocives pour l’environnement. L’occident et la triade auraient abandonné l’industrie manufacturière et l’industrie lourde, la grosse industrie chimique et sidérurgique qui sont des industries polluantes sans que cela nourrisse beaucoup de croissance alors que ce développe dans le Nord des universités, des centres de recherches, des activités supérieures du tertiaire qui vont bien payer le travail qualifié et dans un cadre de vie « agréable » parce que nettoyé des effets négatifs de l’industrialisation lourde.

La théorie de la nouvelle division internationale du travail va distribuer les avantages comparatifs aux uns et aux autres pas vraiment en fonction de prédispositions locales, pas vraiment selon des conditions historiques ou des anticipations, mais simplement sur des effets de pouvoir qui font que les plus puissants et les plus riches monopolisent les activités les plus intéressantes. On est dans une théorie marxiste et impérialiste parce qu’on voit la division internationale du travail comme reproduisant ce qui existe à l’intérieur d’un pays avec des effets de confiscations. La mondialisation n’est plus un jeu à somme positive, mais plutôt quelque chose dont il faut se protéger. On va retomber sur les théories de Litz avec la tentation des replis protectionnistes qui considèrent qu’il y a une offensive dans le commerce international et considère qu’il faut défendre le territoire et établir des protections vis-à-vis de l’agressivité commerciale venant des pays de la triade.

Critique altermondialiste

L’idée est que la mondialisation se traduit non seulement par une extension du domaine du marché géographique, mais par une extension du domaine du marché économique dans le sens où de nouveaux pays entrent dans le domaine du commerce international, mais aussi dans chacun des pays concernés, des nouveaux pans de la vie sociale, économique et culturelle entrée dans le domaine de l’économie. On le voit à l’échelle de la fin du XXème siècle et au début du XIXème siècle, un tas de secteurs ont été privatisés, absorbé par le marché, de plus, de plus en plus d’institutions qui ne sont pas du domaine du marché vont commencer à reproduire le fonctionnement du marché, à commencer par les universités, les musées et les hôpitaux. Le problème est de transformer en bien économique des biens que l’on peut difficilement considérer comme tels. Un bon exemple est la question des ressources naturelles et de l’environnement. Dans l’idée que le système de marché et de production capitaliste est le plus efficace, on peut comprendre qu’on préfère confier l’exploitation d’une mine de charbon ou d’une exploitation de pétrole à une entreprise privée plutôt que de le faire à une entreprise étatique parce que la productivité et l’efficacité économique seraient meilleures dans une entreprise privée plutôt que dans une entreprise d’État. C’est ce que tend à démontrer l’histoire économique récente du XXème siècle. Le problème est de savoir à qui sont ces ressources naturelles.

Elles sont sorties de terre par une entreprise, ce sont donc des coûts de productions liées à l’exploitation et il est normal que les coûts de production se retrouvent dans le prix de la matière première. On comprend mal pourquoi une compagnie privée aurait le droit d’exploiter un gisement qui ne lui appartient pas sans d’une façon ou d’une autre payer cette ressource. Si on raisonne en terme purement mathématique, le coût de l’épuisement est infini. Il est difficile d’imaginer le coût d’épuisement d’une ressource pour les générations futures. C’est quelque chose de très difficile à comptabiliser dans l’économie. Il est également très compliqué de prendre en compte la question de la pollution dans le marché. La situation la plus claire et la plus normale est que le coût de la population est externalisé, payé par la société et rarement par le responsable. Quand on est face à des ressources naturelles qui sont des biens qui ne sont pas produits par leur exploitant, mais captés par leur exploitant, les raisonnements économiques et le marché présentent des difficultés de fonctionnement et des insuffisances. Pour le dire autrement, si on découvre une ressource naturelle, sur le plan économique, la logique veut qu’on ressorte le plus de cette ressource le plus rapidement possible. L’enjeu pour la société est essentiel. Ce sont des biens pour lesquels l’abandon au marché pose tout un tas de problèmes, mais avec des solutions comme celle du pollueur-payeur ou le système de la rente, mais ce sont des solutions hors marché. Un autre exemple est celui des droits humains. Le travail est un marché avec une offre qui est celle des travailleurs et une demande qui est celle de leurs employeurs. On pourrait abandonner le fonctionnement du marché aux lois du marché, mais cela n’est pas acceptable parce qu’on ne peut séparer le travailleur du travailleur. Les droits humains entrent en contradiction à un moment ou un autre avec le marché du travail parce qu’on ne peut pas séparer le corps, la personne et le travail qu’il effectue. À partir du moment où on considère qu’un certain nombre de droits humains sont inaliénables, cela va peser sur le marché du travail. On ne peut pas laisser le travail être régulé par les règles du marché. Cela aboutit au fait qu’on va finir par confondre le travail et le travailleur et qu’on va vendre non pas du travail, mais de la force du travail. Typiquement, laisser le travail être régulé par le marché aboutirait de manière caricaturale à l’esclavage. Dans beaucoup de pays, le travail est un secteur qu’on va essayer de protéger des règles du marché. Ce serait une règle supérieure qu’on ne pourrait réguler par l’offre de la loi et de la demande.

Dans nos sociétés, il y a l’idée que le marché convient à certains biens économiques, mais pas pour d’autres. Le problème de la mondialisation n’est pas simplement l’entrée de nouveaux pays dans le circuit économique des échanges internationaux, mais c’est aussi celui du fait que le marché grignote de plus en plus de part dans les économies. Il y a la tentation de mettre les frontières en défend, mais aussi de dire que certains domaines de l’économie ne veulent pas participer au commerce international. Ce que l’on peut présenter comme une forme d’archaïsme marxisant et comme réflexe de « vieux gauchiste » contre la mondialisation peut avoir des formes plus sophistiquées et n’est pas étranger aux pratiques actuelles. Les premiers à refuser que le marché sature l’espace économique sont les grandes puissances libérales. On retrouve l’idée avancée par les anthropologues du gradient de l’échange avec des qualités d’échange qui se dégradent avec le don contre don, la redistribution et le marché.

Il y avait une dimension assez caricaturale à cette représentation. Évidemment, dans les faits, cela est plus compliqué parce que ces circuits économiques présentés comme étant vraiment indépendants des uns des autres, soit la redistribution, soit le marché, soit le don dont bien, il y a des zones qui sont des zones un peu floues. Parmi les alternatives qui sont proposées au marché, ce n'est pas forcément la redistribution soviétique ni le don contre donc, mais il y a aussi des solutions qui se trouvent dans le marché, dans un certain marché, à la limite du marché, dans des accommodations vis-à-vis du marché.

Combien de temps une action est détenue par son propriétaire en moyenne actuellement ? 14 secondes. En moyenne une action est détenue 14 secondes et là on comprend bien qu’il y a quelque chose qui ne tourne par rond parce que les actions sont normalement directement prises en compte sur l'économie réelle. Derrière, il y a des bureaux, une usine, un patron, un PDG, un conseil d'administration, des ouvriers, des clients, des machines, mais encore des stocks. On sent bien que 14 secondes n'a aucun sens si on est en deux ordres de grandeur totalement incommensurables. Ce sont des mouvements qui sont purement spéculatifs sans aucune prise directe avec l'économie réelle. Cela veut dire que, comme beaucoup de personnes physiques gardent leur action pendant des années, il y a des systèmes automatiques d'actions où on les garde quelques centièmes de seconde. Il y a une mesure de cette déconnexion entre l'économie réelle et une forme de visualisation d'économie financière qui semble très inquiétante. On comprend à quel point cela est déstabilisant pour l'économie de ne pas pouvoir compter sur des investissements plus longs que de 14 secondes. On comprend également à quel point les fameux capitaux flottants sont désastreux pour l'économie réelle. Ce sont des capitaux qui ne s’investissent que très passagèrement en un lieu dans un pays et qui, dès que le moindre signe avant-coureur de crise se profile, ces capitaux partent. Cela a un caractère autoréalisateur de ces révisions financières. On se dit que dans tout ça, il faudrait mettre toute friction. Toute taxe sur les transactions auraient pour effet de stabiliser les capitaux. S’il est des taxes qui freinent le rapatriement et le flottement des capitaux, peut-être que quand une petite difficulté passagère se produit, les capitaux vont rester et ces difficultés vont bien être digérées. Il faut de la friction afin de mettre en phase la temporalité de l'économie réelle et la temporalité de l'économie financière ou virtuelle pour empêcher les gens de vendre leurs actions toutes les 14 secondes. Une taxe opère ce frein. Une taxe est comme un frein dans l'espace et dans le temps. C’est une solution qui permet à la fois de stabiliser le système et puis de ponctionner un peu dans le marché pour alimenter un circuit de redistribution.

Une autre solution intermédiaire alternative est le commerce équitable. Les petites parties du commerce équitable ne sont pas vraiment gérées par le marché. C'est grosso modo géré en majorité régie par le marché. C'est « moi » qui spontanément accepte de verser 5 %. Cela peut s’apparenter à du don. C'est une irruption en quelque sorte du don contre don au sein du marché donc les deux systèmes peuvent aussi cohabiter.

La fin de l’histoire c'est aussi cette l’idée qu’on s’est un peu dégagé des idéologies avec que d'un côté les marxistes et d’un autre côté les libéraux et qu’il y a un certain pragmatisme dans les comportements avec une certaine hybridation dans les comportements et qu'on peut trouver au sein du marché des solutions pour se prévenir du marché. La conclusion est que le marché est quelque chose que tout le monde s'accorde à vouloir réguler.

La galaxie de l'altermondialiste, c'est-à-dire il y a des dizaines d'organismes différents qui interviennent avec des idéologies différentes comme, par exemple, contre l'OMC, contre la banque mondiale, contre le G7. Ce qui est intéressant dans ce schéma avec l’idée de la galaxie est que la contestation du modèle de la mondialisation se fait en beaucoup de plans différents avec beaucoup de logiques différentes et puis des acteurs différents.

Conclusion

Quand on réfléchit à la géographie des échanges et à la mondialisation, il y a beaucoup trop de marchés alors qu'il y a d'autres circuits économiques comme ceux de la redistribution et du don contre don. Si on regarde beaucoup trop le commerce international alors que les échanges majoritairement se font localement en quantité, il y a comme une presbytie qui empêche de voir ce qui est essentiel et se qui se passe sur de toutes petites distances et qui fait comme qu’on voit juste de très loin ce qui se fait sur des milliers de kilomètres entre les frontières et qui est en fait une petite partie des échanges économiques.

La deuxième note importante est que la théorie ricardienne et la théorie des avantages comparatifs est au cœur de tout cela. C’est une force idéologique incroyable au sens où cette théorie justifie l’idéologie libérale. L’argument et aspect essentiel de cette théorie des avantages comparatifs est que tous les pays peuvent participer au commerce international et que le commerce international est un jeu à somme positive. Cela ne règle pas la question de la répartition des bénéfices.

Le troisième point est l'idée des effets des rendements croissants sur le verrouillage spatial et temporel de l’avantage comparatif avec l’idée d'inverser les choses et de ne pas penser que l'avantage comparatif et la prédisposition à la spécialisation au commerce international en pensant que l’avantage comparatif et le résultat. La quatrième est d’importance, un démenti empirique, est la question des rapports Nord-Sud. La géographie des échanges internationaux qui est marquée par cette fracture Nord-Sud est inexplicable dans le cas de la théorie l’avantage comparatif.

Le cinquième point est que tous ces débats sur les échanges internationaux sont des débats qui sont très anciens. Dès le XIXème siècle, on retrouve un grand nombre de débats autour du libre-échange notamment autour de la théorie de Litz. Les débats aujourd'hui sur la mondialisation ne sont pas nouveaux parce que la mondialisation n’est pas un phénomène nouveau et les arguments sont toujours les mêmes.

La théorie de Ricardo de l’avantage comparatif promet la spécialisation des échanges internationaux, mais promet également le développement, c’est-à-dire que tous les pays qui vont participer au commerce international vont connaître le développement et s’enrichir. Un des démentis à cette théorie est qu’il existe encore des pays pauvres alors qu’ils participent depuis des années au commerce international.