« Democracy, citizenship and elections » : différence entre les versions

(Page créée avec « Nous allons nous focaliser sur les aspects spatiaux et sur la manière dont la citoyenneté et les élections se distribuent dans l’espace et laissent apparaitre des in... ») |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| Ligne 1 : | Ligne 1 : | ||

We will focus on the spatial aspects and on the way in which citizenship and elections are distributed in space and reveal inequalities. | |||

{{Translations | {{Translations | ||

| Ligne 5 : | Ligne 5 : | ||

}} | }} | ||

= | = The spread of liberal democracy = | ||

== | == Waves of democratization == | ||

[[File:géopo vagues de démocratisation 1.jpg|thumb|]] | [[File:géopo vagues de démocratisation 1.jpg|thumb|]] | ||

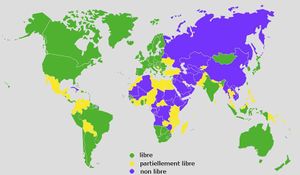

We are in an era where liberal democracies are in the majority, but this is not the case everywhere and was not always the case. In The third wave: democratization in the late twentieth century published in 1991, Huntington distinguished three waves of democratization: | |||

*1828 | *1828 -1926: suffrage for the majority of white men ; | ||

*1943 | *1943 - 1964: Following the Allied victory in 1945 and which also included much of the decolonisation with a sharp increase in democratic systems and democratisation processes. Alongside the idea of the state as a complex concept with a wide variety of perspectives, researchers have begun to take an interest in the democratization process; | ||

*1974 | *1974 - 1991: Portuguese Revolution, Latin America, Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe. | ||

[[File:freedom house 2013.png|thumb|center]] | [[File:freedom house 2013.png|thumb|center]] | ||

Some observers speak of a fourth wave of democratization following the Arab Spring, but in view of more recent developments, other researchers prefer to remain cautious. | |||

This is not a linear process. Among partially free democracies there has been a reversal of the trend since 1992. | |||

== | == Democracy: the end of history? == | ||

The observation of stagnation raises the question of whether democratization and the trend towards a political system called "liberal democracy" is the end of history. In The End of History and the Last Man published in 1989, Fukuyama posits that: "What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government". | |||

Many critics like Jacques Derrida in Spectres de Marx published in 1993 postulate that in the history of humanity, there has been more and more democracy, but that there has never been as much violence, inequality, exclusion, famine and economic oppression as today. If liberal democracy is matched with peace and prosperity, it is not the end of history today. Perry Anderson and some Marxists postulate that this is the end of "yes" history, of "yes" democracy, but not the end of capitalism. | |||

A democracy is a political system, but history has alternative fluctuations that will transform it again. The global transformations that we see in the field of security and in the economic field reflect the current transformations. | |||

== | == Procedural approaches, substantive approaches == | ||

A procedural approach focuses on institutions, rules and standards that facilitate access to democratic law, such as electoral competition or press freedom. | |||

A substantial approach focuses on results. It was pointed out that there should be more equality, fairness and justice. There may be democratic bodies, but to what extent. | |||

There is uneven democratization in space, globally, as well as at the state level. | |||

== | == From national to global: cosmopolitanism == | ||

There is a shift from "democratic deficit" to "cosmopolitical citizenship". For Mary Kaldor in Global civil society: an answer to war published in 2003, "In the context of globalization, democracy in its substantial sense is compromised, however perfect formal institutions may be, simply because so many important decisions that affect people's daily lives are no longer made at the state level. | |||

The idea of cosmopolitical democracy is to make world politics more transparent, more accountable, more participatory and more respectful of the rule of law is not new. A framework that can bring together multiple proposals and campaigns, not a single approach. | |||

== | == Cosmopolitical democracy: actors and measures == | ||

[[File:géopo parlement du monde 1.jpg|thumb|]] | [[File:géopo parlement du monde 1.jpg|thumb|]] | ||

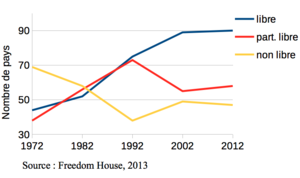

In Cosmopolitan democracy published in 2012, Archibugi and Held propose possible methods: | |||

* | *the State: reducing differences between nationals and foreigners, protecting minorities, putting foreign policy at the service of democratization. | ||

*organisations | *international organisations: make them more independent of national governments. | ||

* | *judicial authorities: making non-compliance with international standards more costly. | ||

*participation | *citizen participation: create a World Parliamentary Assembly along the lines of the European Parliament. | ||

* | *political communities without borders. | ||

Who benefits? The dispossessed, foreigners, cosmopolitan groups, global civil society, global political parties, trade unions and labour movements, large multinational corporations. | |||

= | = Citizenship = | ||

The modern concept of citizenship emerges with the modern state. Marshall published in 1950 Citizenship and Social Class, in Class, citizenship and social development and distinguished three aspects of citizenship: | |||

* | *civil rights: property, speech, constraint ; | ||

* | *political rights: participation in governance; | ||

* | *social rights: quality of life (work, education, health, etc.). | ||

The concept of citizenship has become increasingly broad. Political geography is concerned with the distribution within the space of citizenship and the different forms of citizenship. | |||

== | == Citizenship: a (geo)political instrument? == | ||

Citizenship is often an instrumentalized discourse that is part of production and use in political struggles and strategies. The designation of citizen and non-citizen can be found in : | |||

* | *the State: citizenship is equal and universal; opposition: the benefits of citizenship are denied to certain groups. | ||

Citizenship is a contested concept and practice. | |||

== | == Formal and informal limits of citizenship == | ||

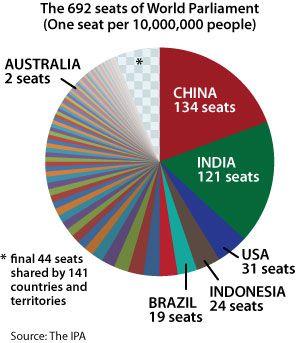

There are different perspectives on citizenship: | |||

* | *formal boundaries: de jure citizenship; | ||

* | *informal boundaries: de facto citizenship. | ||

[[File:géopo imites formelles et informelles de la citoyenneté 1.png|thumb|]] | [[File:géopo imites formelles et informelles de la citoyenneté 1.png|thumb|]] | ||

For example, people have de facto citizenship, but in law they do not have citizenship. Conversely, people have de jure citizenship, but de facto do not have the opportunity to enjoy all the rights that citizens have. Feminist literature questions the fact that in the evolution of history, women have often been found to have neither de jure nor de facto rights. | |||

== Citoyenneté insurgée == | == Citoyenneté insurgée == | ||

| Ligne 147 : | Ligne 146 : | ||

= Summary = | = Summary = | ||

Although waves of democratization can be identified and liberal democracies are now the dominant political system, this is neither a linear evolution nor a sign that there is no more economic violence, inequality, exclusion, famine and oppression. Attempts at cosmopolitical democracy are manifested in various practices and campaigns, but without significant effects. | |||

Neoliberal developments have had a strong influence on the functioning of democracy and the construction of citizenship. Flexible" or "partial" citizenship will emerge as well as new spaces for mobilization for citizenship rights. Electoral geography, despite its criticism, continues to offer insights into the link between politics and space, particularly in democratization contexts. | |||

= Annexes = | = Annexes = | ||

= References = | = References = | ||

<references/> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Jörg Balsiger]] | [[Category:Jörg Balsiger]] | ||

Version du 8 mai 2018 à 19:41

We will focus on the spatial aspects and on the way in which citizenship and elections are distributed in space and reveal inequalities.

The spread of liberal democracy

Waves of democratization

We are in an era where liberal democracies are in the majority, but this is not the case everywhere and was not always the case. In The third wave: democratization in the late twentieth century published in 1991, Huntington distinguished three waves of democratization:

- 1828 -1926: suffrage for the majority of white men ;

- 1943 - 1964: Following the Allied victory in 1945 and which also included much of the decolonisation with a sharp increase in democratic systems and democratisation processes. Alongside the idea of the state as a complex concept with a wide variety of perspectives, researchers have begun to take an interest in the democratization process;

- 1974 - 1991: Portuguese Revolution, Latin America, Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe.

Some observers speak of a fourth wave of democratization following the Arab Spring, but in view of more recent developments, other researchers prefer to remain cautious.

This is not a linear process. Among partially free democracies there has been a reversal of the trend since 1992.

Democracy: the end of history?

The observation of stagnation raises the question of whether democratization and the trend towards a political system called "liberal democracy" is the end of history. In The End of History and the Last Man published in 1989, Fukuyama posits that: "What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government".

Many critics like Jacques Derrida in Spectres de Marx published in 1993 postulate that in the history of humanity, there has been more and more democracy, but that there has never been as much violence, inequality, exclusion, famine and economic oppression as today. If liberal democracy is matched with peace and prosperity, it is not the end of history today. Perry Anderson and some Marxists postulate that this is the end of "yes" history, of "yes" democracy, but not the end of capitalism.

A democracy is a political system, but history has alternative fluctuations that will transform it again. The global transformations that we see in the field of security and in the economic field reflect the current transformations.

Procedural approaches, substantive approaches

A procedural approach focuses on institutions, rules and standards that facilitate access to democratic law, such as electoral competition or press freedom.

A substantial approach focuses on results. It was pointed out that there should be more equality, fairness and justice. There may be democratic bodies, but to what extent.

There is uneven democratization in space, globally, as well as at the state level.

From national to global: cosmopolitanism

There is a shift from "democratic deficit" to "cosmopolitical citizenship". For Mary Kaldor in Global civil society: an answer to war published in 2003, "In the context of globalization, democracy in its substantial sense is compromised, however perfect formal institutions may be, simply because so many important decisions that affect people's daily lives are no longer made at the state level.

The idea of cosmopolitical democracy is to make world politics more transparent, more accountable, more participatory and more respectful of the rule of law is not new. A framework that can bring together multiple proposals and campaigns, not a single approach.

Cosmopolitical democracy: actors and measures

In Cosmopolitan democracy published in 2012, Archibugi and Held propose possible methods:

- the State: reducing differences between nationals and foreigners, protecting minorities, putting foreign policy at the service of democratization.

- international organisations: make them more independent of national governments.

- judicial authorities: making non-compliance with international standards more costly.

- citizen participation: create a World Parliamentary Assembly along the lines of the European Parliament.

- political communities without borders.

Who benefits? The dispossessed, foreigners, cosmopolitan groups, global civil society, global political parties, trade unions and labour movements, large multinational corporations.

Citizenship

The modern concept of citizenship emerges with the modern state. Marshall published in 1950 Citizenship and Social Class, in Class, citizenship and social development and distinguished three aspects of citizenship:

- civil rights: property, speech, constraint ;

- political rights: participation in governance;

- social rights: quality of life (work, education, health, etc.).

The concept of citizenship has become increasingly broad. Political geography is concerned with the distribution within the space of citizenship and the different forms of citizenship.

Citizenship: a (geo)political instrument?

Citizenship is often an instrumentalized discourse that is part of production and use in political struggles and strategies. The designation of citizen and non-citizen can be found in :

- the State: citizenship is equal and universal; opposition: the benefits of citizenship are denied to certain groups.

Citizenship is a contested concept and practice.

Formal and informal limits of citizenship

There are different perspectives on citizenship:

- formal boundaries: de jure citizenship;

- informal boundaries: de facto citizenship.

For example, people have de facto citizenship, but in law they do not have citizenship. Conversely, people have de jure citizenship, but de facto do not have the opportunity to enjoy all the rights that citizens have. Feminist literature questions the fact that in the evolution of history, women have often been found to have neither de jure nor de facto rights.

Citoyenneté insurgée

Dans des contextes où de gens n’ont pas de citoyenneté de facto ni de jure, des gens commencent à s’approprier des droits de citoyenneté, mais en dehors des institutions formelles. De l’exercice de droits de citoyenneté en dehors des espaces et institutions formelles à l’opposition forcée contre l’autorité légale en cherchant la perturbation du fonctionnement de l’État.

Il est possible de s’interroger sur la représentativité de certains groupes. Dans Insurgency and spaces of active citizenship : the story of Western Cape Anti-eviction Campaign in South Africa publié en 2005 dans Journal of Planning Education and Research, Miraftab et Wills proposent une étude de cas sur Cape Town, Afrique du Sud étudiant la transformation néolibérale de l’État et la mobilisation contre les expulsions forcées avec la mis en place d’« espaces invités » et d’« espaces inventés ».

Aihwa Ong (2010 [2006]) : Mutations de citoyenneté

Aihwa Ong publie en 2006 Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty avec pour point de départ est que les flux mondiaux des marchandises, des technologies et des populations produisent des mutations de la citoyenneté qui amènent à une citoyenneté contestée à travers une transformation de la démocratie. La néolibéralisation mondiale amène les États à fractionner le terrain national en « espaces d’hypercroissance » connectés à des réseaux transnationaux.

Les distinctions strictes entre citoyens et étrangers sont abandonnées aux profits de la quête du capital humain. Qui est citoyen n’est plus nécessairement ou exclusivement celui qui a des droits de citoyenneté, mais celui qui peut mobiliser les opportunités. Les droits et avantages de citoyenneté sont désormais dépendants des critères néolibéraux.

Mutation de citoyenneté

Des populations mobiles ou exclues réclament des droits en vertu de principes universalisant qui sont des critères néolibéraux ou droits de l’hommiste. Aihwa Ong constate l’émergence de différentes formes de citoyenneté qui sont partielle ou postnationale. Selon des sondages, 15% de la population mondiale considère avoir une identité postnationale qui est une identité allant au dehors des frontières nationales. Par exemple, en Europe, la citoyenneté est partielle (« postnationale »), en Asie, certains pays reforment des lois d’immigration pour attirer des investisseurs.

Le point commun est que la sécurité des citoyens devient dépendante de leur capacité à faire face aux insécurités globalisées. Le résultat étant de nouvelles formes de revendication, nouveaux espaces de citoyenneté :

- postnationale : exigences selon l’éthique de la culture et de la religion comme en Indonésie, ou en Malaisie ;

- technologique : le cyberespace des réseaux sociaux comme en Chine ;

- biologique : de la survie élémentaire au langage de santé avec le cas de Tchernobyl.

La géographie électorale

La géographie électorale est une sous-discipline qui explore la pratique, l’organisation et l’incidence spatiales de la compétition électorale. André Siegfried a analysé des corrélations entre droite et gauche et des éléments de géographie physique, économique et culturelle. Siegfried va proposer une critique du déterminisme environnemental :

- mouvement empiriste des années 1950 et 1960 : rejet des « grandes théories », mais est très descriptif avec la théorisation à travers des notions constructiviste de lieu et espace qui permettent de mettre en avant la spécificité historique des orientations de vote ou encore les liens entre soutiens aux partis et transformations économiques et sociales ;

- la géographie de représentation : la construction des circonscriptions et du biais électoral, comme, par exemple, le « gerrymandering ».

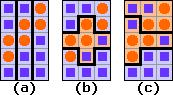

Le « gerrymandering »

Une province a trois circonscriptions de taille égale de 15 électeurs : 9 bleu, 6 orange. En principe, il y a une majorité pour les bleus. En redéfinissant les circonscriptions électorales, il est possible d’arriver à des résultats très différents :

- (a) 3-0 pour bleu ;

- (b) 2-1 pour bleu ;

- (c) 2-1 pour orange.

C’est une pratique efficace dans les systèmes politique est surtout efficace dans les systèmes non proportionnels. Deux stratégies peuvent amener à des résultats :

- « packing » : concentrer des électeurs d’un parti dans une circonscription afin de réduire leur influence dans d’autres ;

- « cracking » : distribuer des électeurs d’un parti sur plusieurs circonscriptions afin de refuser la formation de blocs importants.

Durant le Civil Rights movement, des villes comme Boston ont pratiqué le gerrymandering.

Étude de cas : la géographie électorale de Senraz

Dans Participation politique et origines nationales : une analyse de la mobilisation électorale dans une ville populaire en Suisse publié en 2014, Boughaba propose une étude à forte dimension empirique et conceptuelle. Le contexte est le suivant avec une démobilisation vis-à-vis de la politique institutionnelle.

Une approche souligne les déterminants de participation et d’abstention à l’échelle individuelle comme le :

- niveau de diplôme, classe sociale, âge identifiés comme les facteurs électoraux déterminants ;

- les intérêts pour élections, adhésion partisane, connaissances politiques, particularités cantonales.

Une approche souligne les déterminants de participation et d’abstention à l’échelle contextuelle comme, par exemple, les milieux familiaux.

La question de recherche de Boughaba est : en quoi, les trajectoires migratoires et les positions sociales, les réseaux familiaux et liés à l’origine nationale ainsi que les lieux de vie nous permettent de comprendre la (dé)mobilisation ? L’auteure cherche à combiner des données individuelles et contextuelles.

La population de Senraz

La population est majoritairement étrangère et il y a une forte diminution de la proportion d’ouvriers.

C’est un contexte ou l’argument de trouver une relation entre classe sociale et comportement électoral n’est pas aussi important que si l’étude avait été produite durant les années 1970.

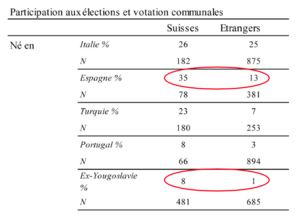

La participation aux élections : échelle individuelle

Boughaba va mettre en exergue une inégalité selon le lieu de naissance et une inégalité selon naturalisation. L’explication a à voir avec l’ancienneté de la population étrangère. Les arrivants de l’ex-Yougoslavie qui ne résident pas aussi longtemps à Sanraz que les espagnols ont un taux de participation plus bas. Le processus de naturalisation amène à une certaine socialisation au comportement démocratique.

La participation aux élections : échelle contextuelle

La participation politique est due à l’importance du travail militant des leaders. La participation est plus haute dans les rues où il y a une forte concentration de leur compatriote, donc il y a une importance du milieu résidentiel.

Summary

Although waves of democratization can be identified and liberal democracies are now the dominant political system, this is neither a linear evolution nor a sign that there is no more economic violence, inequality, exclusion, famine and oppression. Attempts at cosmopolitical democracy are manifested in various practices and campaigns, but without significant effects.

Neoliberal developments have had a strong influence on the functioning of democracy and the construction of citizenship. Flexible" or "partial" citizenship will emerge as well as new spaces for mobilization for citizenship rights. Electoral geography, despite its criticism, continues to offer insights into the link between politics and space, particularly in democratization contexts.