The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

The history of the Third World has its roots in the depths of European colonisation, an era that redefined the global geopolitical landscape. This period, which began with Christopher Columbus's arrival in America in 1492, spanned several centuries and continents, leaving an indelible mark on nations and cultures around the world. In America, colonisation led to major upheavals for indigenous societies, marked by radical transformation under the impact of European domination. In Asia, the colonial presence, which mainly took shape in the 19th century, was characterised by the creation of trading posts and protectorates, thus changing regional commercial and political dynamics. In Africa, colonisation redrew borders and reconfigured social and economic structures, both north and south of the Sahara.

At the same time, the slave trade, including both the transatlantic and eastern slave trades, had a devastating impact on African populations. This phenomenon not only disrupted societal structures in Africa, but also had a significant impact on societies throughout the Americas and the Middle East. The colonial pact, established by the European powers, played a crucial role in the formation of the Third World. This set of economic policies was designed to keep the colonies economically dependent, limiting their industrialisation and confining them to the role of producers of raw materials. This economic structure, coupled with the consequences of colonisation and the slave trade, created a gap between developed and developing countries, a gap that continues to characterise the modern world.

This overview of colonisation and its impacts reveals how this period crucially shaped today's economic and social disparities, profoundly affecting relations between developed and developing countries.

Global context at the dawn of the 16th century[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Cultural Diversity and Pre-colonial Geopolitics[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The 1500s, often referred to as the beginning of the modern era, represents a crucial period in world history marked by a series of important events and developments.

The discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492 marked a pivotal moment in world history, initiating the era of European overseas exploration. Columbus, a Genoese explorer in the service of Spain, was looking for a sea route to Asia. He sailed west across the Atlantic and reached what he thought was the "Indies", but was in fact the American continent, starting with the Caribbean islands. This event paved the way for other European expeditions, leading to the complete discovery of the North and South American continents. Powers such as Spain, Portugal, France, the Netherlands and England soon began to establish colonies in these new lands. These colonisations had a profound impact, particularly on the indigenous peoples, who were confronted with unknown diseases, wars, the loss of their lands and other forms of colonisation, leading to a massive reduction in their population. The discovery also laid the foundations for transatlantic trade, integrating the Americas into a global trade network. This included trade in precious goods such as gold and silver, as well as the infamous transatlantic slave trade. At the same time, the Columbian exchange - the transfer of plants, animals, crops, people and diseases between the New World and the Old World - led to major ecological and biological changes. The impact of Columbus's discovery of America was also felt in Europe. It stimulated competition between European nations for overseas territories and contributed to the rise of capitalism and the assertion of European maritime power. Columbus's discovery of the New World not only transformed the history of this continent, but also had a profound and lasting impact on global economic, political and cultural dynamics.

The Renaissance, a flourishing period in European history, reached its peak in the 16th century, although it had begun in Italy in the 14th century. This cultural, artistic, political and economic movement was marked by a profound renewal and rediscovery of the arts, science and ideas of classical antiquity. The heart of the Renaissance lay in its artistic transformation. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael redefined the standards of art, introducing innovative techniques and exploring themes ranging from the religious to the secular. Their work not only highlighted human beauty and complexity, but also served as a catalyst for new forms of artistic expression throughout Europe. Beyond art, the Renaissance was also a period of scientific and intellectual progress. Humanism, a central school of thought in this period, emphasised education, the value of the individual and the pursuit of knowledge based on reason and observation. This led to significant advances in fields such as literature, philosophy and science, and laid the foundations for the scientific revolution to come. Politically and economically, the Renaissance saw the emergence of the modern nation-state, with monarchs such as Francis I in France and Henry VIII in England centralising power. Italian city-states such as Florence and Venice became centres of commerce and culture, facilitating the mix of ideas and wealth that fuelled the movement. The Renaissance was a period of cultural and intellectual awakening that profoundly influenced Europe and the world. It laid the foundations for many aspects of modern society and continues to influence culture, art, science and politics today.

The Protestant Reformation, which began in the 16th century, marked a major turning point in Europe's religious and cultural history. This period began with Martin Luther, a German monk and teacher, who published his 95 theses in 1517. These theses criticised several aspects of the Catholic Church, including the sale of indulgences, and called for a faith more centred on the Bible and justification by faith alone. The movement launched by Luther quickly gained in popularity and spread to other regions, leading to the diversification of Protestantism. Figures such as John Calvin in Switzerland and Ulrich Zwingli contributed to this diversification, each bringing their own interpretations and teachings. Faced with this challenge, the Catholic Church launched the Counter-Reformation to reform the Church from within and combat Protestant ideas. The Council of Trent, held from 1545 to 1563, played a key role in this response, reaffirming Catholic doctrines and introducing ecclesiastical reforms. The Reformation had significant political and social implications. In some countries, it strengthened the power of monarchs, while in others it led to major religious conflicts, such as the Wars of Religion in France and the Thirty Years' War in Central Europe. The legacy of the Reformation is rich and complex. In religious terms, it led to unprecedented diversity in Christianity. Culturally and socially, it encouraged literacy and education through its emphasis on personal reading of the Bible. Economically and politically, it influenced the structure of power in Europe and helped shape modern society. The Protestant Reformation was a crucial event in the history of the West, profoundly influencing the development of civilisation in many areas.

The Ottoman Empire, established in the late 13th century, underwent a period of significant growth and became a dominant world power, particularly during the 15th and 16th centuries. This development was characterised by impressive territorial expansion and growing influence in regional and global affairs. The rise of the Ottoman Empire began under the reign of Mehmed II, known for the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, marking the end of the Byzantine Empire. This conquest not only strengthened the Ottoman Empire's strategic position but also symbolised its rise as a major power. Constantinople, renamed Istanbul, became the capital and a cultural, economic and political centre of the empire. Under the reigns of sultans such as Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent, the empire expanded further, encompassing vast areas of the Middle East, North Africa, the Balkans and Eastern Europe. The Ottoman Empire was remarkable not only for its military might but also for its sophisticated administration and cosmopolitan society. Trade played a crucial role in the economy of the Ottoman Empire. By controlling key trade routes between Europe and Asia, the empire was able to enrich itself and influence regional and global economies. The Ottoman Empire also served as a bridge between East and West, fostering cultural and scientific exchange. In addition to its military and economic power, the Ottoman Empire was also a centre of culture and art. It was the cradle of unique architectural styles, music, literature and the arts, which were influenced by a diversity of cultural traditions found throughout the empire. The influence of the Ottoman Empire was also significant in political and religious terms. As a caliphate, it was a leader in the Muslim world, playing a central role in Islamic affairs. The rise of the Ottoman Empire therefore played a crucial role in the balance of power in both Europe and the Islamic world, leaving a lasting imprint on world history. Its legacy is reflected in the many cultural, architectural and historical aspects that endure in the regions it once ruled.

The development of the printing press in the 15th century was one of the most significant turning points in human history, revolutionising the way information and ideas were disseminated. This innovation is mainly attributed to Johannes Gutenberg, a German goldsmith, who developed the first printing press with movable type around 1440. Before Gutenberg's invention, books were copied by hand, a time-consuming and costly process that severely limited their availability. The printing press enabled the mass production of books and other printed documents, drastically reducing the cost and time needed to produce them. This made books and written documents more accessible to a wider public, something that had previously been reserved for a privileged elite. The impact of this invention on society and culture was profound. It played a crucial role in the dissemination of knowledge and ideas, enabling the rapid spread of information that transcended geographical and social boundaries. This increased dissemination of knowledge contributed to major movements such as the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. The printing press also had a significant impact on education and literacy. With the increasing availability of books, education became more accessible, helping to raise literacy rates across Europe. It also enabled the standardisation of languages and texts, playing a key role in the development of national languages and literature. Politically, the printing press enabled the spread of political ideas and was a powerful tool for reformers and revolutionaries. Governments and churches often tried to control or censor the printing press in order to maintain their power, which testifies to its considerable influence. The development of the printing press was a revolution in the dissemination of information and ideas, shaping modern society by increasing access to knowledge, encouraging intellectual and cultural innovation, and influencing political and social structures.

The 16th century marked a period of remarkable progress in science and technology, laying the foundations for what was to become the scientific revolution. This era saw the emergence of key scientific figures whose work profoundly changed our understanding of the world. Nicolaus Copernicus, a Polish astronomer, played a crucial role in this paradigm shift. In 1543, he published "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium" (On the revolutions of the celestial spheres), in which he proposed a heliocentric model of the universe. This model placed the Sun, rather than the Earth, at the centre of the solar system, challenging the geocentric vision that had prevailed since Antiquity and was supported by the Church. Later, Galileo Galilei, an Italian scientist, also made major contributions. With the improvement of the telescope, Galileo was able to observe celestial phenomena that supported the heliocentric model. His observations, in particular of the phases of Venus and the moons of Jupiter, provided convincing evidence against the geocentric model. These scientific advances were not without controversy. Copernicus' heliocentric theory, reinforced by Galileo's discoveries, was considered heretical by the Catholic Church. Galileo himself was tried by the Inquisition and had to publicly renounce his ideas. Beyond astronomy, other fields of science also saw significant progress. The understanding of human anatomy was revolutionised by figures such as Andreas Vesalius, whose detailed work on the structure of the human body challenged many ancient medical beliefs. These scientific advances had a profound impact on the society and culture of the time. They encouraged a more empirical and questioning approach to the world, laying the foundations for the modern scientific method. The emphasis on observation and rationality had repercussions far beyond science, influencing philosophy, religion and even politics. The 16th century was a defining moment for science, marking the beginning of an era of discovery and innovation that reshaped human understanding of the universe and laid the foundations for future scientific developments.

The 16th century witnessed the emergence and strengthening of the modern nation-state in Europe, a process that marked a significant transition from medieval feudalism to more centralised and unified forms of governance. This transformation was in part propelled by influential monarchical figures such as Francis I in France and Henry VIII in England. Francis I, King of France, played a key role in consolidating royal authority by centralising power. His reign was characterised by the strengthening of the royal administration and the expansion of French territory. Francis I also promoted cultural and artistic development, making France a centre of the Renaissance. His efforts to centralise power helped to establish a more coherent and efficient modern state. In England, Henry VIII also marked an important stage in the formation of the modern state. His reign is best known for the break with the Roman Catholic Church and the establishment of the Church of England, an act that not only had religious implications but also strengthened royal authority. This centralisation of power was crucial to the formation of the English nation state. The rise of the modern state was accompanied by the establishment of centralised institutions, the development of a unified legal system and the emergence of a professional bureaucracy. These changes contributed to the formation of more unified nations and the gradual diminution of the power of feudal lords, who had previously been the main holders of territorial and military power. These developments also had an impact on international relations, with the emergence of more structured diplomacy and the birth of the concept of national sovereignty. States began to interact as distinct, sovereign entities, laying the foundations for the modern international system.

The expansion of European trade and exploration in the 16th century marked a crucial stage in the establishment of world trade and cultural exchange on an unprecedented scale. This period was characterised by bold voyages and geographical discoveries, of which Vasco da Gama's voyage in 1498, which opened up a new sea route to India, is particularly notable. Vasco da Gama's voyage, by rounding the Cape of Good Hope and reaching the Indian coast, marked the first time that a direct maritime link between Europe and Asia had been established. This had a huge impact on international trade, as it gave European merchants direct access to precious Asian spices and other goods, bypassing the middle men of the Middle East. This new route contributed to the wealth and influence of the European nations involved, notably Portugal, which took a leading position in the spice trade. The expansion of European trade was accompanied by an era of exploration, as navigators and explorers mapped unknown territories and established contacts with various peoples and cultures around the world. These interactions led to a significant cultural, technological and biological exchange, known as the Columbian Exchange, which saw the transfer of plants, animals, cultures, people and diseases between continents. European expansion also had a major impact on the local populations of the regions explored. In America, Africa and Asia, the impacts were profound, ranging from colonisation and economic exploitation to major cultural and societal changes. The slave trade, in particular, became a dark and crucial aspect of this period, with the forced displacement of millions of Africans to the Americas. Economically, this period laid the foundations for modern capitalism and the global economic system. Increased trade and the creation of global trade routes encouraged the growth of national economies and the development of the international financial system. The expansion of European trade and exploration in the 16th century was a key driver of globalisation, profoundly influencing the world economy, international politics and intercultural relations. The discoveries and interactions of this era have indelibly shaped the modern world.

The 16th century was a fundamental period for the beginnings of capitalism and the development of world trade. With the exploration of new trade routes and the establishment of overseas colonies, European nations began to engage in international trade on an unprecedented scale, laying the foundations for the modern capitalist system. The opening of new sea routes to Asia by explorers such as Vasco da Gama, and the discovery of the Americas by Christopher Columbus, gave European powers direct access to a wide range of valuable resources. These resources included spices, gold, silver and other exotic goods that were in great demand in Europe. Control of these routes and sources of wealth quickly became a major issue, leading to intense competition between European nations. This period also saw the emergence of trading companies, such as the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company, which played a key role in trade and colonisation. These companies, often supported by their respective governments, were among the world's first joint stock companies, a major innovation in finance and enterprise. Increased international trade stimulated the development of the market economy and mercantile capitalism, where trade and capital accumulation were at the heart of economic activity. This system encouraged investment, risk-taking and innovation, key features of capitalism. At the same time, competition for resources and power between European nations led to military conflict and the colonisation of large parts of the world. This colonial expansion was motivated not only by the search for wealth, but also by the desire to control strategic territories and extend political and cultural influence. However, this period of history was also marked by darker aspects, notably the transatlantic slave trade and the exploitation of indigenous peoples in the colonies. These practices had profound and lasting repercussions, the effects of which are still visible today. The beginnings of capitalism and world trade in the 16th century were a driving force behind economic, political and cultural transformation. Not only did this period shape the economic development of Europe, it also laid the foundations for today's global economic system.

The 1500s were undeniably a turning point in world history, marking the beginning of a series of significant events and developments that shaped the modern world. This period saw major transformations in a variety of fields, from geopolitics and economics to culture and science. One of the most significant events of this period was the discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492, which paved the way for European exploration and colonisation of the Americas. This discovery not only transformed the cartography of the world, but also led to cultural and economic exchanges on an unprecedented scale, known as the Columbian Exchange. Culturally and intellectually, the 16th century was marked by the Renaissance, a movement that redefined the arts, literature and science, and fostered a renewed interest in the ideas and values of classical antiquity. This period saw the emergence of such iconic figures as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael. In the field of religion, the Protestant Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther, challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and led to a significant fragmentation of Christianity in Europe. This movement had a profound impact on religion, politics and society in Europe, and helped shape the modern religious landscape. The period also witnessed the rise of the modern state, with monarchs such as Francis I in France and Henry VIII in England reinforcing centralised power and laying the foundations for modern government structures. At the same time, scientific advances were remarkable, with figures such as Copernicus and Galileo challenging geocentric conceptions of the universe and laying the foundations for the scientific revolution. Finally, the expansion of trade and exploration, along with the beginnings of capitalism, transformed the global economy. The creation of new trade routes and the emergence of trading companies laid the foundations of world trade and the contemporary economic system. The 1500s laid the foundations for many aspects of our modern world, indelibly influencing the trajectory of human history in the fields of geopolitics, culture, science, economics and religion.

Societies and Civilisations across the Globe[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

At the beginning of the 16th century, Europe was undergoing a period of significant and complex transformation. After overcoming the ravages of the great plague of 1400, Europe's population began to repopulate, representing around 20% of the world's population at the time. This period of renaissance was marked by cultural and intellectual renewal, as well as major changes in society and politics. The European Renaissance saw a renewed interest in ancient knowledge, with a revival of literature, art and philosophy inspired by the legacy of ancient Greece and Rome. At the same time, Europe absorbed and adapted innovations from other parts of the world. For example, although printing with movable type is often associated with Johannes Gutenberg in Europe, it had precursors in Asia. Similarly, gunpowder, initially developed in China, was adopted and perfected in Europe, transforming warfare and military defence. From a religious and cultural point of view, Europe at this time was largely homogeneous, dominated by Christianity. This was reinforced by the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from several countries, notably Spain in 1492, a policy that contributed to a certain degree of religious and cultural uniformity, but also to internal tensions and conflicts. In terms of religion, this period also saw Europe become more firmly anchored in the Christian faith, which was often perceived as superior. This worldview was a key driver in European colonial expansion, where religion was often used to justify exploration and colonisation. Europe was also an outward-looking region, actively seeking to extend its influence around the world. This was evident in voyages of exploration, such as that of Vasco da Gama, which opened up new trade routes and marked the beginning of the era of European colonisation.

Russia is renowned for its vast territory, making it the largest country in the world in terms of surface area. It spans two continents, Europe and Asia, and covers an area of around 17 million square kilometres. This vast expanse gives Russia a great diversity of landscapes, climates and natural resources. The European part of Russia, although much smaller than its Asian counterpart, is home to the majority of its population and its main cities, including Moscow, the capital, and St Petersburg. This region is characterised by extensive plains and temperate climates. Siberia, which makes up most of Russia's territory in Asia, is famous for its vast forests, mountains and harsh climate, with long, very cold winters. Despite its harsh climate, Siberia is rich in natural resources, such as oil, natural gas and various minerals. Russia's immense size means that it shares borders with many countries, and its spread over two continents makes it an important geopolitical player. This vast territorial expanse also poses unique challenges in terms of governance, economic development and connectivity across the country. Russia's colossal size is a defining feature of its national identity, influencing its policies, economy and place on the international stage.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Europe had a level of socio-economic development that, in many respects, was comparable to that of other advanced regions of the world, such as India and the Middle East. This period, prior to the Industrial Revolution, was characterised by predominantly agrarian economies in most parts of the world, including Europe. From a technological point of view, Europe was not clearly superior to the civilisations of the Middle East or India. These regions had a long history of significant contributions in fields such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine and engineering. For example, the Middle East, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age, had developed significant knowledge in science and technology, which later influenced Europe. In India, substantial advances had been made in fields such as mathematics (notably the development of the concepts of zero and the decimal numbering system) and metallurgy. India was also famous for its textiles and handicrafts, which were highly prized in Europe and elsewhere. However, from the 16th century onwards, Europe began to experience a number of key developments that would contribute to its technological and economic advance over other regions. Gutenberg's printing press, for example, facilitated the wider dissemination of knowledge. The Great Discoveries, by opening up new trade routes and establishing contacts with different parts of the world, also had a considerable impact. Although Europe in the early 16th century was not technologically superior to regions such as India or the Middle East, it was about to embark on a series of changes that would transform its socio-economic structure and set it on the road to global domination in the centuries that followed.

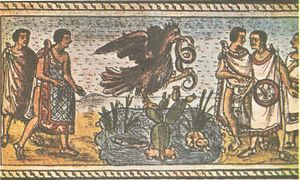

At the beginning of the 16th century, before the arrival of the Europeans, America had a remarkable cultural and technological diversity, with advanced civilisations including the Aztecs, Mayans and Incas. North America was vast and made up of diverse indigenous societies and cultures. These peoples had developed lifestyles adapted to their varied environments, ranging from hunting and gathering to sophisticated forms of agriculture and urban society in some regions. The southernmost parts of America, notably the regions of present-day South America, were less densely populated in some areas, but were home to advanced civilisations such as the Inca Empire. The Incas had created a vast empire with a complex administration, innovative agricultural techniques and an impressive road network. The heart of power and cultural sophistication in pre-Columbian America lay in the central regions, where the Aztec and Mayan empires were particularly advanced. These civilisations had developed sophisticated writing systems, remarkable astronomical knowledge, monumental architecture and organised societies. However, these civilisations also had significant technological limitations compared to Europeans of the same era. One of the most notable was the absence of advanced metallurgy, particularly in iron and steel, which limited their ability to produce weapons and tools comparable to those of Europeans. Nor did they have large domestic animals such as horses or oxen, which played a crucial role in Europe for agriculture and as a means of transport. These technological differences had a major impact on their encounters with European explorers and conquerors. Although Amerindian civilisations were sophisticated and advanced in many areas, the absence of certain key technologies, combined with other factors such as the diseases brought by the Europeans, contributed to their rapid decline in the face of European colonisation.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Africa and the Middle East presented diverse socio-economic and technological realities, influenced by geographical, cultural and historical factors. The Maghreb, comprising the regions of North Africa such as Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, was part of the Ottoman Empire. This region had a level of economic and technical development close to that of Europe, with flourishing cities, sophisticated irrigation systems and a rich culture influenced by exchanges between Arab, Berber and Mediterranean civilisations. Sub-Saharan Africa, often referred to as "Black Africa", presented a great diversity of cultures and economic systems. In many areas, geographical conditions, such as the proximity of the desert or the presence of the tsetse fly, made large-scale farming and the use of draught animals difficult. This led to forms of social and economic organisation adapted to these environments, often based on subsistence farming, nomadic herding or fishing. The Middle East, under the dominant influence of the Ottoman Empire, was a crossroads of cultures and trade. Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, was one of the largest and most developed cities in the world at the time, with an estimated population of around 700,000. It was an important centre of commerce, culture and administration, with an impressive infrastructure and architecture. The economic and technical development of the Middle East and parts of North Africa was comparable to, and sometimes even greater than, that of Europe in the same period. These regions had a rich cultural and scientific heritage, particularly in fields such as medicine, astronomy and mathematics. At the beginning of the 16th century, both the Maghreb and the Middle East showed advanced levels of development, influenced by their integration into the Ottoman Empire. By contrast, sub-Saharan Africa, with its unique geographical challenges, had developed economic and social systems adapted to its particular environmental conditions.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Asia was a continent of great demographic and cultural importance, home to many of the world's greatest civilisations at the time. With a population far greater than that of Europe, Asia was the cradle of ancient and advanced civilisations. Empires and kingdoms in China, India, Japan, Southeast Asia and other regions had developed rich cultures and complex political and economic systems. In India, the emergence of the Mughal Empire in the early 16th century marked the beginning of a period of stability and prosperity. Under the leadership of rulers such as Akbar the Great, the empire unified much of the Indian subcontinent, becoming a major military and political power. The sophistication of Mughal administration, combined with India's cultural and economic wealth, made the region an important global player. India was particularly famous for its cotton industry, which was the largest and most advanced in the world at the time. The quality and finesse of Indian textiles were highly sought-after, and the trade in cotton and other products such as spices played a central role in the world economy. The Indian textile industry was not only an economic engine, but also an example of India's technical sophistication, which in some areas often equalled or surpassed that of Europe. From a technical and industrial point of view, certain regions of Asia, including India, were on a par with or even superior to Europe. This was particularly evident in areas such as metallurgy, textile manufacturing and shipbuilding. Asia in the early 16th century was a dynamic and diverse continent, home to advanced civilisations with sophisticated economies and powerful political systems. India, in particular, stood out as a political, economic and military giant, rivalling and sometimes surpassing Europe in many areas.

China, in the course of its long and rich history, has been the cradle of many fundamental inventions that have had a profound impact on humanity. In the period leading up to and including the early 16th century, China made significant contributions in various fields of science and technology. The invention of paper is attributed to Cai Lun at the beginning of the 2nd century AD, although forms of paper probably existed before him. Chinese paper, made from plant fibres, was of superior quality and more durable than the writing materials used elsewhere in the world at the time. China also developed high-quality inks, essential to the art of calligraphy and the dissemination of knowledge. China is also credited with the invention of gunpowder. Initially discovered in an alchemical context, gunpowder was first used for military purposes in China. This invention revolutionised warfare tactics the world over. Although the precise details of carbon refining in ancient China are not clearly established, China has historically demonstrated great mastery of metallurgy, including steel production. The compass, another crucial instrument invented in China, was first used for divination before finding applications in navigation. It revolutionised maritime navigation, enabling much more accurate and distant journeys. These Chinese inventions have had a major impact not only in China but throughout the world, shaping the development of many societies and cultures. The transmission of these technologies to other parts of the world, often through the Silk Road and other trade networks, has played a key role in the development of science and technology on a global scale. In this sense, China has been a major source of innovation and a key contributor to humanity's technological progress.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the world showed a degree of homogeneity in terms of technological and socio-economic development between different civilisations, despite some disparities. China, for example, was at the forefront in several technological fields, but other regions such as India, the Middle East, parts of Africa and Europe had also developed advanced technologies and socio-economic systems. These regions shared innovations through trade and cultural interaction, facilitating the spread of knowledge and technology. The gaps in technology and development between these civilisations were not extremely pronounced. Regions such as the Ottoman Empire and India had levels of sophistication comparable to China's in areas such as architecture, literature, science and technology. In Europe, despite lagging behind in some respects, major advances were underway, particularly with the Renaissance and the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. The ability to spread innovations from one region to another played a crucial role in global development. Innovations from advanced regions spread to other parts of the world and were often adapted and improved according to local contexts. Towards the end of the 16th century, Europe began to assert itself increasingly on the world stage, largely through colonisation. This European expansion was driven by a range of factors, including advances in maritime navigation, economic and religious motivations, and a desire for political expansion. Europe succeeded in exploiting the world's resources and extending its influence through colonisation and the establishment of overseas empires. Although differences existed between civilisations at the beginning of the 16th century, there was a certain homogeneity in terms of development. This homogeneity facilitated the spread of innovations around the world, paving the way for the global interconnection that accelerated with European expansion and colonisation.

The major stages of European colonisation[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Colonisation in America: The Dawn of the Colonial Era and its Transformations[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The period between 1520 and 1540 marks a crucial phase in the history of the Americas, characterised by the rapid and brutal conquest of pre-Columbian civilisations by the Spanish conquistadors. This conquest, which began less than thirty years after the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492, had devastating consequences for the continent's indigenous peoples. The conquistadors, led by figures such as Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, targeted advanced and organised civilisations such as the Aztecs and the Incas. Despite the sophistication and complexity of these societies, they were quickly crushed by the European invaders. Several factors contributed to this rapid outcome, including the military superiority of the Spanish, the use of tactics and diplomacy, and the exploitation of internal divisions within the native empires. The conquest of these empires was also marked by a terrifying human cost. In addition to the direct violence of the conquest, the indigenous population was decimated by diseases imported from Europe, such as smallpox, to which the native peoples had no immunity. By 1650, the population of the Americas had fallen dramatically, from around 60 million to around 10 million. This demographic fall was one of the biggest in human history. The relative ease with which the conquistadors overthrew these advanced civilisations contributed to a superiority complex among Europeans. This perception of superiority, coupled with the wealth derived from the New World, reinforced Europe's power and influence on the world stage. The conquest of the Americas by the Spanish conquistadors not only radically transformed the American continent, but also had profound repercussions on the global balance of power and on cultural and racial perceptions that had persisted for centuries.

The tragic decline in the indigenous population of the Americas following the European conquest can be attributed to two main causes: the introduction of infectious diseases and direct violence in the form of massacres and forced labour. The meeting of the European, African and American worlds led to what is known as "microbial unification". The Europeans, later accompanied by Africans deported as slaves, brought with them to America diseases unknown to the indigenous populations. These diseases, such as smallpox, typhus, leprosy, dysentery and yellow fever, were particularly devastating. The indigenous population, having no natural immunity to these diseases, suffered massive losses. Smallpox, in particular, wreaked immeasurable havoc, decimating entire communities. At the same time, the conquistadors perpetrated large-scale direct violence against the indigenous peoples. This violence included systematic massacres and the enslavement of many communities. Forced labour, often in inhumane conditions such as in the mines, not only took the lives of many indigenous people but also destroyed the very foundations of their social and cultural organisation. These two factors, combined, led to a dramatic reduction in the indigenous population of the Americas. This dark period in history has had a profound impact on American societies and continues to resonate in the collective memory and history of the indigenous peoples. The conquest of the Americas remains one of the most tragic and transformative events in human history.

The European conquest of the Americas gave rise to an economy based primarily on the exploitation of both natural resources and the indigenous population. This economy evolved in several phases, marked by the intensity and nature of the exploitation. Initially, gold and silver were the main targets of the European conquerors, giving rise to an economy of plunder. The riches of the Inca and Maya empires, among others, were systematically stolen. Considerable treasures were transferred to Europe, disrupting both American and European economies. Once the easily accessible riches had been exhausted, attention turned to mining, particularly in places like the Potosí mines in what is now Bolivia. These mines, among the largest and richest in the world, were exploited primarily for their silver, using the forced labour of indigenous populations in extremely difficult conditions. From the mid-sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the plantation system began to take shape. This system was adapted to the geological and climatic differences between America and Europe. In Latin America, the tropical climate was ideal for growing crops such as sugar and coffee. These crops were destined for export to the European metropolises and were grown on large farms. The workforce on these plantations consisted mainly of Indian slaves and, later, African slaves brought over via the transatlantic slave trade. Working conditions on these plantations were often brutal and inhumane, with little regard for the lives or welfare of the slaves. The economy of the Americas under European rule was characterised by intense exploitation of natural and human resources. Gold and silver were first plundered and then mined, before the economy turned to plantation agriculture, intensively exploiting both the soil and slave labour. This period left deep scars on the continent, the effects of which are still felt today.

Bartholomé de Las Casas, a Spanish Dominican, played a crucial role in the history of colonisation in the Americas, particularly in defending the rights of indigenous peoples. During the period of intensive colonisation and exploitation, it became clear to contemporaries that the local population was dwindling drastically, partly as a result of exploitation and imported diseases. De Las Casas was one of the first and most fervent defenders of the indigenous peoples. As a priest, he pleaded before the Spanish judicial authorities for the protection of the Indians, arguing that their conversion to Catholicism made their enslavement unacceptable. His argument was based on moral and religious principles, asserting that the Indians, as converts or potential converts to Christianity, had spiritual and human rights that should be respected. However, de Las Casas faced strong opposition from plantation owners and other colonial interests, who were heavily dependent on slave labour for their farms. These groups did not want to give up their source of cheap labour and vigorously opposed de Las Casas' efforts. Although de Las Casas did not succeed in convincing the Spanish authorities to abolish Indian slavery immediately, his work helped to raise awareness of their plight and influenced subsequent policies. A few decades after his efforts, Indian slavery was gradually abandoned, although many forms of exploitation and forced labour persisted. The work of Bartholomé de Las Casas is an important testimony to the resistance to injustice in this period of history. Although his successes were limited in his time, he remains a significant historical figure for his advocacy of the rights of indigenous peoples.

The demographic collapse of the Amerindian populations had a major impact on the development of the transatlantic slave trade. Faced with a drastic reduction in the indigenous workforce due to disease, massacres and inhumane working conditions, the European colonisers looked for alternatives to maintain their economic activities, particularly on the large sugar and coffee plantations. To compensate for the loss of labour due to the demographic collapse of the indigenous populations, the Europeans turned to Africa. This was the start of a massive trade in African slaves, marking the explosion of the transatlantic slave trade. Captured Africans were forcibly transported across the Atlantic in extremely difficult and inhumane conditions, a crossing known as the "Middle Passage". This influx of African slaves into the Americas was a direct response to the need for labour in the colonies. Slaves were mainly employed on plantations, but also in other sectors such as mining and domestic service. The living and working conditions of African slaves were brutal, characterised by extreme violence and systematic dehumanisation. The transatlantic slave trade became one of the most tragic and inhuman features of this period of world history. Not only did it have devastating consequences for the millions of displaced Africans and their descendants, it also had a profound impact on the economic, social and cultural development of the Americas. The demographic collapse of the Amerindian populations was a determining factor in the emergence and explosion of the transatlantic slave trade, a dark episode that indelibly shaped the history and society of the Americas.

Colonial expansion in North America[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The initial colonisation of North America by Europeans differed from that of Latin America, partly because of differences in climate and perceptions of economic opportunity. North America, with its temperate climate, is more like Europe. However, unlike Latin America, which offered immediate wealth in the form of gold and silver as well as climatic conditions favourable to the cultivation of highly profitable products such as sugar and coffee, North America did not seem to offer the same immediate economic opportunities to the first European colonisers. In Latin America, the Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors quickly discovered civilisations rich in gold and silver, such as the Inca and Aztec empires, which stimulated intense interest and rapid colonisation. In North America, on the other hand, the first European explorers found no such instant riches. Moreover, the indigenous societies of North America were less centralised and monumental than those of Latin America, making conquest and exploitation less obvious and immediately lucrative. As a result, early colonisation efforts in North America were relatively limited and focused on activities such as the fur trade, fishing and agriculture, rather than the extraction of valuable minerals. It was only later, with the recognition of North America's agricultural and commercial potential, that European settlement expanded. The initial economic interests in North America were less obvious than those in Latin America, which influenced the approach and intensity of European colonisation in these regions. The logic of exploitation, focused on immediate wealth and quick economic gains, led to an initially lesser focus on North America.

European colonisation of North America, which intensified later than in Latin America, had distinct motivations and characteristics. It was largely based on settlement, i.e. the establishment of permanent communities rather than immediate economic exploitation. Religious conflicts in Europe, particularly between Catholics and Protestants, were a major driving force behind migration to North America. Many Europeans sought refuge from religious persecution and political unrest in their home countries. The Mayflower, which reached what is now Massachusetts in 1620, is an emblematic example of this migration. It carried Puritans, a group of English Protestants seeking religious freedom, establishing one of the first permanent settlements in North America. As transport costs fell and news of opportunities in North America spread, more and more Europeans were attracted by the prospect of a better life. These immigrants were motivated not only by religious reasons, but also by the promise of land, wealth and a new life. Unlike the Latin American colonies, where indigenous labour was often exploited for resource extraction, the North American colonies were predominantly agricultural, with settlers working the land themselves. This settlement dynamic had a profound impact on the development of North America, leading to the creation of societies with political and social structures distinct from those of Latin America. Over time, these settlements evolved into complex societies with their own cultural and political identities, laying the foundations for what would later become the United States and Canada.

The European Footprint in Asia: Trade and Protectorates[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The period from the late 15th century to the mid-18th century marked an era of European maritime dominance, with significant implications for India and other parts of Asia. This era began with Vasco da Gama's arrival in India in 1498, paving the way for growing European influence in the region. The arrival of Europeans in India and other parts of Asia coincided with a period when European ships, armed with cannons and other advanced naval technology, dominated the seas. This naval superiority enabled European powers, notably Portugal, the Netherlands, Great Britain and France, to control key sea routes and dominate maritime trade. In India, the European presence transformed the dynamics of trade. The European powers established trading posts and colonies along the coasts, controlling key points of maritime trade. Local merchants were often forced to sell their products, particularly spices, to these European powers, who then exported them to Europe and other markets. Although the spice trade represented only a small fraction (0.02-0.05%) of Asia's GNP, it generated enormous profits for the Europeans. European domination of the seas also had the effect of limiting the development of Asian fleets. The national navies of countries like India were outmatched by European naval power, hindering their ability to engage in maritime trade on an equal footing. This period of European domination had profound and lasting effects on India and other parts of Asia. It not only redirected trade flows and economic relations, but also paved the way for more direct European political and colonial influence in these regions, particularly evident with the rise of the British East India Company and Britain's subsequent colonisation of India.

The period after 1760 marks a significant turning point in the history of India, characterised by increasing British domination, notably through military victories and growing land occupation. The Battle of Plassey in 1757 was a key event in this process. This battle saw a British army, led by Robert Clive, achieve a decisive victory over the forces of the Nawab of Bengal. This victory was not only significant in military terms, but also marked the beginning of British political and economic dominance in India. After this victory, between 1790 and 1820, the British gradually extended their control over vast areas of India. They used both their own army and local forces to wage military campaigns against various Indian political entities. This expansion was facilitated by the weakness of the Mughal Empire, which was in decline at the time, and by the skilful use of internal divisions within India. The British not only took advantage of the political rivalries and disunity between the various Indian kingdoms and principalities, but also made use of their technological and military superiority. Their ability to mobilise considerable resources and use advanced military tactics played a crucial role in their success. These developments led to the establishment of the British Empire in India, which was to become one of the jewels in the British crown. The period of British rule in India had profound and lasting consequences, affecting the political, social, economic and cultural structure of the subcontinent. It also laid the foundations for the resistance and liberation movements that would emerge over the course of the 20th century, culminating in India's independence in 1947.

In the 18th century, China differed from the other major Asian powers of the time in that it had not been colonised and remained a unified empire. Under the Qing dynasty, China was a vast and powerful empire, enjoying considerable political stability and economic prosperity. The Qing dynasty, which ruled China at the time, succeeded in maintaining the unity and stability of the empire. This was achieved through efficient centralised government, competent administration and a powerful army. China also had a flourishing agricultural economy and active internal and external trade, reinforcing its position as a major power. China was able to resist colonisation thanks to its military strength, imposing size and centralised governance. This enabled the empire to maintain its sovereignty in the face of the colonial ambitions of European powers, which were already well established in other parts of Asia. Although China was not colonised, it did have significant interactions with foreign powers. These interactions were often marked by complex dynamics, with China seeking to maintain its autonomy while engaging in limited and controlled trade with Europe. However, towards the end of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century, China began to experience increased pressure from Western powers, which eventually led to a series of conflicts and concessions, including the Opium Wars and the Unequal Treaties. These events marked the beginning of a period of challenge to China's sovereignty and territorial integrity. Eighteenth-century China was notable for its ability to maintain its status as a unified and independent empire, despite increasing pressure from Western colonial powers. This period represents an important era in Chinese history, preceding the challenges and transformations of the 19th century.

The legacy of European colonisation in North Africa[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

French colonisation of North Africa began in the 19th century and played a significant role in the international politics of the time, even influencing the beginnings of the First World War.

France's conquest of Algeria in 1830 marked the beginning of an era of profound change in North Africa. This period radically transformed Algerian society and the economy, and had a lasting impact on relations between France and Algeria. The arrival of French settlers, followed by Italians, Spaniards and other Europeans, led to the mass expropriation of Algerian farmland. This land was redistributed to the new arrivals, who used it to grow crops for export to France. This process not only changed Algeria's land structure, but also disrupted its traditional social and economic fabric, with significant repercussions for the indigenous population. The colonisation of Algeria was anything but peaceful. It was met with fierce resistance from the local population, led by figures such as Emir Abdelkader. These conflicts were marked by intense violence, reflecting the struggle of Algerians against foreign occupation and exploitation. The colonial era in Algeria has left a complex legacy that continues to shape relations between France and Algeria. Questions of identity, colonial history and its aftermath remain at the heart of discussions and exchanges between the two countries. In short, the conquest and colonisation of Algeria by France were crucial events, indelibly shaping the history and society of both nations.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the expansion of French influence in North Africa, with the colonisation of Tunisia and Morocco. These two countries were incorporated into the French colonial empire in the form of protectorates, a move motivated by economic, strategic and political interests. In 1881, France established a protectorate over Tunisia following the signing of the Treaty of Bardo. This treaty marked the beginning of French control over Tunisia, which until then had been a semi-autonomous Ottoman territory. The establishment of the protectorate enabled France to exert considerable political and economic influence in Tunisia, while officially retaining the nominal authority of the local bey. Morocco, for its part, became a French and Spanish protectorate in 1912 following the signing of the Treaty of Fez. France gained control of most of Morocco, while Spain gained smaller areas in the north and south of the country. As in Tunisia, the establishment of the protectorate in Morocco was aimed at extending French influence in the region and securing strategic economic interests, particularly in response to the colonial ambitions of other European powers, such as Germany. Both protectorates saw significant changes. France introduced administrative, economic and educational reforms, profoundly altering the social and political structures of both countries. However, this period was also marked by resistance and struggles for independence, reflecting the growing dissatisfaction of local populations with colonial rule. The colonisation of Tunisia and Morocco therefore played an important role in the history of North Africa, and the legacies of this period continue to influence the region today. These events not only reshaped the political map of North Africa, but also had a profound impact on the cultural, social and economic dynamics of Tunisia and Morocco.

The Agadir crisis of 1911 is a striking example of the geopolitical tensions and colonial rivalries that characterised Europe in the early 20th century. Germany's dispatch of the SMS Panther gunboat to Agadir Bay in Morocco was a direct challenge to French influence in the region. This show of force by Germany was intended to renegotiate the terms of the European presence in Morocco and to assert its own colonial ambitions. This crisis exacerbated the already high tensions between the major European powers, particularly between France and Germany. It highlighted the colonial and nationalist rivalries that were intensifying in Europe, contributing to the atmosphere of mistrust and competition that prevailed at the time. These tensions were a prelude to the wider conflicts that were to erupt with the First World War. French colonisation of North Africa, particularly Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, had a profound impact on the region. It brought about major social, cultural and political transformations, permanently changing the landscape of these territories. Colonial policies were often marked by administrative and economic reforms, but also by conflict and resistance on the part of local populations. Internationally, France's actions in North Africa have influenced power dynamics and relations between the major European powers. French colonial expansion not only reshaped the political map of the region, but also had an impact on the international system, helping to shape the conditions that led to the major conflicts of the 20th century. The Agadir crisis and the French colonisation of North Africa are examples of how European imperial ambitions shaped world history in the early 20th century, with consequences that are still felt today.

The French colonisation of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, as well as the colonial interests of other European powers in the Mediterranean region, were linked to major political and strategic issues, particularly in the context of the growing tensions that preceded the First World War. The Mediterranean has always been a strategic region due to its importance for maritime trade and its geopolitical position. For France and other European powers, securing control or influence over this region was crucial to their national interests. The colonies in North Africa offered not only economic advantages, but also served as strategic bases for the projection of military and naval power in the Mediterranean. The run-up to the First World War was marked by intense rivalry between the great European powers for colonial expansion. France's colonisation of North Africa was part of this dynamic, with rival powers, notably Germany and Italy, also seeking to extend their influence in the region. The Agadir crisis of 1911 is a case in point, where Germany challenged French ambitions in Morocco. Meanwhile, local populations in the colonies were facing major political, social and economic changes. These changes were often accompanied by resistance and struggles for independence, which continued throughout the 20th century. The French colonies in North Africa were more than just territorial extensions; they were strategic pawns in the great game of European colonial politics and power. Control of these territories was seen as essential to maintaining the balance of power and preparing for future confrontations, notably the First World War.

At the turn of the 20th century, Egypt and Libya became focal points of colonial competition, mainly because of their strategic position and their importance for European imperial ambitions.

In the 1880s, Egypt occupied a unique position in the colonial order of the time, being under substantial British influence without formally being a colony. This was largely due to the strategic importance of the Suez Canal, a sea route inaugurated in 1869 that transformed international shipping. The Suez Canal, linking the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, revolutionised maritime trade by considerably shortening the distance between Europe and Asia. For Britain, with the world's largest colonial empire and India as its jewel, the canal was of vital importance. It provided faster and more efficient access to its colonies in Asia, making control of this sea route of paramount strategic importance. British influence in Egypt therefore increased, particularly after the opening of the canal. The British were particularly keen to secure this sea route against any potential threat, whether from other colonial powers or internal unrest in Egypt. This led to an increased military and political presence in Egypt, with the British exerting considerable influence over Egyptian domestic affairs. This British dominance in Egypt was a key part of their overall strategy to maintain and strengthen their empire, in particular by securing their route to India. Control of the Suez Canal became a major issue in the colonial politics and international rivalries of the time, reflecting the complexity of imperial interests and the competition for strategic points around the world.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Italy, driven by a sense of nationalism and imperialist ambition, began to set its sights on Libya, seeing the region as an opportunity to extend its influence and assert its status on the international stage. Italy's conquest of Libya was part of a wider framework of colonial competition between the European powers. The era of Italian nationalism and imperial expansionism led Italy to seek to establish a colonial presence in North Africa, following in the footsteps of other European powers such as France and Great Britain. The year 1911 marked a turning point with the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War. Italy laid claim to Libya, then part of the Ottoman Empire, with the aim of establishing an Italian protectorate. This military campaign, which lasted from 1911 to 1912, was crowned with success for Italy, which thus took control of Libya. Libya represented for Italy not only a new colony to exploit for its resources, but also a means of strengthening its presence in the Mediterranean and positioning itself as a major colonial power. The Italian colonisation of Libya led to major changes in the region, with social, economic and political repercussions. Italy's expansionist move into Libya was characteristic of the period of imperialist rivalries in Europe, when nations sought to extend their influence through colonisation and territorial conquest. The situation in Libya, as in other parts of North Africa, reflected the complex and often conflicting dynamics of the international system at the time.

These developments reflect the way in which European geopolitical and imperial interests reshaped the Middle East and North Africa in the early 20th century. Control of these regions was seen as essential for the security of trade routes and the maintenance of colonial empires, leading to significant political and social changes in these areas. These events not only influenced the international dynamics of the time, but also left a lasting legacy that continues to influence politics and international relations in these regions.

The Colonial Era in Sub-Saharan Africa: Changes and Consequences[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The history of sub-Saharan Africa in the context of colonisation and the slave trade is complex and tragic, marked by forced integration into global economic systems long before the continent was formally colonised.

The colonisation of sub-Saharan Africa by European powers took place later than in other regions, with a particular intensification in the 1880s. This period, often referred to as the 'Partition of Africa', saw European nations competing to extend their influence and control over the African continent. This scramble for Africa was motivated by a variety of geopolitical factors, including the desire to gain access to natural resources, secure markets for European industrial products and extend political and economic spheres of influence. The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 marked a key moment in this process. The European powers, including Britain, France, Germany and Portugal, came together to formalise the rules of African colonisation, dividing up the continent without regard for indigenous social, cultural and political structures. This arbitrary division of African territories often ignored ethnic and historical boundaries, creating artificial borders that have contributed to persistent conflicts and tensions in the region. This period of late colonisation had a profound impact on sub-Saharan Africa, leading to radical changes in its political, economic and social systems. The colonial powers imposed new administrative and economic structures, often aligned with their own interests, and exploited the continent's resources for the benefit of their national economies. The repercussions of this period are still felt today, both in the internal dynamics of African nations and in their relations with the former colonial powers.

Even before the era of formal colonisation, sub-Saharan Africa was tragically integrated into the global economy through the transatlantic slave trade. This slave trade, which lasted from the 16th to the 19th century, involved the forced deportation of 10 to 12 million Africans to the Americas. The scale of the trade and the way in which it was conducted had catastrophic consequences for African societies. The effects of the transatlantic slave trade on sub-Saharan Africa were profound and multidimensional. The massive removal of millions of people not only resulted in a significant loss of population, but also disrupted existing social and economic structures. Communities have been torn apart, families separated, and entire societies have been disrupted by the loss of their members. In addition to the social trauma, the slave trade had a devastating economic impact. Many regions lost a significant proportion of their workforce, slowing economic development and exacerbating inequality and dependency. African societies were irreversibly transformed, with effects that are still felt today. This dark period in history is not only a painful chapter for Africa, but also for the Americas, where African slaves and their descendants significantly shaped the societies in which they were forced to live. The transatlantic slave trade remains a tragic example of the extremes of human exploitation and its lasting impact on societies around the world.

Parallel to the transatlantic slave trade, another, often less mentioned but equally important, slave trade took place between Africa, the Maghreb and the Middle East. This Eastern slave trade lasted from the 7th century until the beginning of the 20th century, and involved between 13 and 15 million Africans. This trade had considerable repercussions on African populations, similar in severity to those of the transatlantic trade. African slaves transported to the Maghreb and the Middle East were used in a variety of capacities, ranging from domestic work to the army, agriculture and crafts. As with the transatlantic trade, this led to the separation of families, the destruction of community structures and major economic disruption in African societies. In addition to the direct human and social impact, the Eastern slave trade also had a cultural and demographic impact on the Middle East and Maghreb regions. The populations of African descent in these regions bear witness to this long history of the slave trade. Recognition of the Eastern slave trade is essential to understanding the full history of African slavery and its long-term effects. It highlights the complexity and extent of the slave trade, and the deep scars it left on the African continent and beyond. The after-effects of this trade, like those of the transatlantic slave trade, continue to affect societies and international relations around the world.

The history of sub-Saharan Africa during the pre-colonial and colonial periods is deeply marked by external influences and interventions, notably through the slave trade and colonisation. These two phenomena had a profound and lasting impact on the continent, leaving indelible marks on its history, social structure and economy. The slave trade, with its two main branches - the transatlantic slave trade and the Eastern slave trade - led to the forced deportation of millions of Africans. These practices not only depopulated vast regions but also disrupted existing social and economic structures. The repercussions of the slave trade extended well beyond the period of its activity, affecting future generations and societal dynamics on the continent and in African diasporas around the world. With the advent of colonisation, mainly in the 1880s, sub-Saharan Africa experienced a new wave of external intervention. The European colonial powers redrew borders, imposed new administrative and economic structures, and exploited the continent's resources for the benefit of their national economies. This period of colonisation also introduced profound changes to the political, cultural and social systems of African societies. Together, these external interventions - the slave trade and colonisation - significantly shaped sub-Saharan Africa. They not only altered the course of its history, but also had a profound impact on the development of its societies and economy. The legacies of these periods are still visible today, influencing the continent's development trajectories, its international relations and our understanding of its past.

Synthesis of European Colonial Expansion[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

European colonisation, which spanned several centuries, had different durations and characteristics in different parts of the world.

European colonisation of America, which began with the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492, marks a major turning point in the continent's history. Although European exploration began in the late 15th century, it was during the 16th century that colonisation really intensified, with nations such as Spain, Portugal, France and Great Britain establishing colonies across vast swathes of the continent. This period of over three centuries of colonisation profoundly altered the landscape of America. The colonial powers not only exploited the continent's natural resources, but also imposed new political, economic and social structures. Indigenous societies and cultures were profoundly affected, often devastated by diseases introduced by Europeans, war, forced assimilation and dispossession of their lands. Colonisation brought about major demographic, cultural and ecological changes. Many indigenous societies were reduced in number or completely destroyed, and cultural practices and languages were often suppressed or altered. At the same time, the mixing of European, African and indigenous peoples gave rise to multicultural and multiracial societies, albeit often stratified and unequal. The consequences of colonisation in America extended well beyond the 1800s and 1830s, a period that saw the emergence of independence movements in many colonies. The legacies of this period continue to influence American nations, manifesting themselves in their political structures, social dynamics and cultural identities. European colonisation in America remains a crucial and complex chapter in the continent's history, with repercussions that continue to be felt to this day.

The period of European colonisation in Asia, although shorter than in America, had a significant impact on the continent. Stretching from approximately 1800-1820 to 1945-1955, the European presence in Asia was often characterised by the establishment of trading posts, protectorates and colonies, rather than the large-scale settlement colonisation seen in America. This period saw powers such as Great Britain, France, the Netherlands and, later, the United States, establish significant influence in various Asian regions. Colonial empires in Asia focused on controlling trade routes, gaining access to natural resources and dominating local markets. Regions such as India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Burma and many others were profoundly affected by European colonisation. Colonisation in Asia led to major political, economic and social changes. Colonial administrative structures, export-oriented economies and the introduction of new technologies and institutions profoundly transformed Asian societies. At the same time, this often led to tensions and conflicts, as colonial practices collided with local structures and traditions. The end of the Second World War marked a turning point for Asian colonies, with the rise of nationalist movements and struggles for independence. This process of decolonisation, which began in the late 1940s and continued until the 1950s, led to the emergence of new independent nation states across Asia. This first wave of decolonisation was a key moment in world history, signalling the decline of the European colonial empires and the birth of a new international order.

European colonisation of North Africa, which began in the 1830s and continued until the 1960s, brought about significant changes in the region. This period of colonisation was mainly dominated by three European powers: France, Italy and Spain. France established its presence in Algeria as early as 1830, later extending its influence to Tunisia and Morocco. Italy, in its quest to become a colonial power, conquered Libya in the early 20th century. Spain, although less present, also maintained colonial territories in northern Morocco. These European interventions profoundly altered the political, social and economic structures of North Africa. The colonial powers introduced new administrations, legal and educational systems, and sought to exploit the region's economic resources for their own interests. These changes were often imposed despite significant resistance from local populations. The period of colonisation was also marked by efforts at modernisation and urbanisation, but these developments were often accompanied by social and economic disparities. Colonial policies sometimes exacerbated ethnic and social divisions and limited economic opportunities for local populations. The era of colonisation in North Africa came to an end in the 1950s and 1960s, a period marked by independence struggles and nationalist movements. These movements led to the end of colonial control and the emergence of independent nations, although the legacy of colonisation continues to influence the region in many ways.

European colonisation of sub-Saharan Africa, although relatively late compared to other regions, had a profound and lasting impact on the continent. It began mainly in the 1880s and 1890s, at a time when European powers were engaged in a frantic race to acquire territory in Africa, a phenomenon often referred to as the "Scramble for Africa". This period of colonisation brought radical changes to sub-Saharan Africa. The borders of today's countries were largely drawn during this period, often without regard to existing ethnic, linguistic or cultural divisions. These artificial borders created nations with diverse and sometimes antagonistic groups, laying the foundations for many future conflicts and political tensions. Politically and economically, colonisation introduced new administrative structures and economic models centred on the exploitation of natural resources for the benefit of the colonial metropolises. These policies often hampered local economic development and exacerbated social and economic inequalities. The period of colonisation in sub-Saharan Africa was also marked by the resistance of local populations against colonial control and oppression. This resistance eventually led to liberation and independence movements in the 1950s and 1960s, marking the end of formal colonisation, although the impacts of this period continue to influence the region in many ways. The decolonisation of sub-Saharan Africa was a complex process, marked by struggles for national sovereignty, cultural identity and economic development.