Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, pre-industrial Europe was essentially a vast patchwork of rural communities where peasant life, far from being a mere backdrop, formed the beating heart of civilisation. Employing around 90% of the population, the peasantry didn't just farm the land; they were the living backbone of the economy, shaping the landscape, nurturing nations and weaving the social bonds that bound villages and terroirs together. Their daily toil on the land was much more than a subsistence quest for survival; it was the driving force behind a largely self-sufficient economy, a key component in the great social machine that fed markets and cities.

Within this agrarian chessboard, each peasant played a decisive role, engaged in a dense network of duties, not only towards the local lord but also in a spirit of mutual solidarity. Often living in austere conditions and subject to the harshness of the seasons and the arbitrary demands of the nobility, the peasants nevertheless shaped the economy of their time with resilience. It is simplistic to paint them solely as an underprivileged and powerless class; they represented the largest social mass in pre-industrial Europe and were key, sometimes revolutionary, players in shaping its future.

We are going to delve into the often little-known daily lives of European peasants in the pre-industrial era, shedding light not only on their farming practices but also on their place within the social hierarchy and the dynamics of resistance and change that they were able to generate. By repositioning them at the centre of the analysis, we are rediscovering the very foundations of Europe's pre-industrial economy and society.

The predominance of agriculture: 15th century - 17th century[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Agriculture was the mainstay of the Ancien Régime economies, and played a predominant role in shaping the socio-professional structure of the period. At the heart of this economic organisation were three main branches of activity: the primary sector [1], covering agricultural activities, the secondary sector [2], covering industry, and the tertiary sector [3], covering services. In the 16th century, the demographic face of Europe was essentially rural and agrarian, with around 80% of its inhabitants involved in agriculture. This figure reveals that four out of five people were attached to the land, an overwhelming proportion that testifies to the deep roots of peasantry in the economic life of the time. The primary sector was not just the biggest employer; it was the bedrock of daily existence, with the majority of the European workforce devoted to cultivating the land, raising livestock and the many other tasks that make up agricultural work.

This table shows the evolution of the distribution of the working population between the primary (agriculture), secondary (industry) and tertiary (services) sectors in countries with developed market economies, with the exception of Japan. The percentages given reflect the share of each sector in the total working population, from 1500 to 1995. At the beginning of the period studied, in 1500, agriculture employed around 80% of the working population, while industry and services each accounted for around 10%. This distribution changed slightly in 1750, when agriculture dropped slightly to 76%, while industry rose to 13% and services to 11%. In 1800, agriculture remained predominant at 74%, but industry continued to rise to 16% and services remained at 11%. A significant shift occurred in 1913, when agriculture accounted for 40% of the working population, closely followed by industry at 32% and services at 28%. This shift became more pronounced in the second half of the 20th century. In 1950, agriculture employed 23% of the working population, while industry accounted for 37% and services 40%, a sign of growing economic diversification. By 1970, the service sector had overtaken all others at 52%, with industry accounting for 38% and agriculture just 10%. This trend continued in the following decades: in 1980, agriculture dropped to 7%, industry made up 34% and services 58%. By 1990, services had increased to 66%, leaving agriculture at 5% and industry at 29%. Finally, in 1995, services largely dominate with 67%, while industry is slightly reduced to 28% and agriculture maintained at 5%, reflecting a world where the economy is strongly oriented towards services. This set of data shows a clear transition in developed economies from a predominance of agriculture to a predominance of services, illustrating the profound changes in economic structures over the centuries.

To understand the predominant importance of agriculture in the economies of the Ancien Régime, it is important to bear in mind that the monetary value of agricultural production far exceeded that of other production sectors. Indeed, the wealth of societies at that time was based on agriculture, whose production dominated the economy to a considerable extent, becoming the main source of income. The distribution of wealth was therefore intrinsically linked to agriculture. In this context, peasants, who made up the majority of the population, depended entirely on agriculture for their livelihood. Their food came directly from what they could grow and harvest. These societies were characterised by a low degree of monetarisation of the economy, with a marked preference for barter, a system of direct exchange of goods and services. Nevertheless, despite this tendency to barter, peasants still needed money to pay the taxes demanded by the Church and the various levels of government. This need for money partly contradicted the non-monetised nature of their daily economy, highlighting the contradictory demands peasants faced in managing their resources and meeting their tax obligations.

In Ancien Régime society, the economic structure was strongly marked by social stratification and class privileges. The incomes of the nobility and clergy, who constituted the elites of the day, were largely derived from the contributions of the Third Estate, i.e. the peasants and bourgeois, who made up the vast majority of the population. These elites grew rich from seigneurial rights and ecclesiastical tithes levied on agricultural land, which was often farmed by peasants. The peasants, for their part, had to pay part of their production or income in the form of taxes and rents, thus forming the basis of the land income of the nobility and the ecclesiastical income of the clergy. This tax system was all the more burdensome for the Third Estate as neither the nobility nor the clergy were subject to taxation, benefiting from various exemptions and privileges. As a result, the tax burden fell almost entirely on the shoulders of the peasants and other non-privileged classes. This economic dynamic highlights the striking contrast between the living conditions of the elites and those of the peasants. The former, although numerically inferior, led a life financed by the economic exploitation of the latter, who, despite their essential contribution to the economy and social structure, had to bear tax burdens disproportionate to their means. This led to a concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few, while the masses lived in constant material insecurity.

Savings played a crucial role in the economy of the Ancien Régime, as they formed the basis for investment. Indeed, it was thanks to the ability to save that individuals and families could afford to acquire productive assets. In a context where agriculture is the cornerstone of the economy, investing in land is becoming a common and potentially lucrative practice. Buying forests or other tracts of farmland was therefore a favoured form of investment. The bourgeoisie, particularly in prosperous cities like Geneva, recognised the value of such investments and often channelled their savings into the purchase of vineyards. This activity, reputed to be more profitable than crafts or services, attracted the attention of those with the means to invest. They then profit from the work of the peasants, who cultivate the land on their behalf, enabling them to make a profit from the production without necessarily being directly involved in the farming work. Even urban merchants, provided they have amassed sufficient wealth, take up land purchases in the countryside, broadening their investment portfolios and diversifying their sources of income. This illustrates how, even within the cities, the economy was intimately linked to the land and its exploitation. However, it is important to note that the agricultural sector was not uniform. It was characterised by a wide variety of situations: some regions specialised in particular crops, others were known for their livestock, and the efficiency of farming could vary greatly depending on the farming methods and property rights in force. This heterogeneity reflected the complexity of the agrarian economy and the different ways in which land could be used to generate income.

The diversity of farming systems[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

As the Middle Ages drew to a close and the periods that followed progressed, significant regional disparities emerged within Europe, particularly between East and West, and North and South. This divergence is particularly evident in the status of peasants and the agrarian systems in force.

The majority of peasants in Western Europe acquired a form of freedom at the dawn of the modern era. This liberation came about gradually, thanks in particular to the weakening of feudal structures and changes in production and property relations. In the West, these developments enabled peasants to become free farmers, with greater rights and better living conditions, although still subject to various forms of economic constraint and dependence. To the east of the imaginary St Petersburg-Trieste line, however, the situation was different. It was in this region that the so-called "second serfdom" developed. This phenomenon was characterised by a strengthening of the constraints weighing on the peasants, who found themselves once again chained to the land by a system of dependence and obligations to the lords. Peasants' rights were considerably restricted, and they were often forced to work the lords' land without adequate compensation, or to pay a significant proportion of their production as rent. This geographical dichotomy reflects a profound socio-economic and legal division within pre-industrial Europe. It also influenced the economic and social development of the different regions, with consequences that would last for centuries, shaping the dynamics of European history.

The State Property System[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In the 17th century, Eastern Europe underwent major social and economic changes that had a direct impact on the status of peasants. In the vast fertile plains of the Ukraine, Poland, Romania and the Balkans, lands that would become known as the breadbasket of Europe because of their high agricultural productivity, a particular phenomenon emerged: the re-imposition of serfdom, known as "second serfdom". This revival of serfdom is largely orchestrated by the "Baltic barons", who are often warlords or aristocrats with vast tracts of land in these regions. The authority of these barons rested on their military and economic power, and they sought to maximise the yields from their land in order to enrich themselves and finance their ambitions, whether political or military. The return of peasants to serfdom meant a loss of their autonomy and a return to living conditions similar to those of medieval feudalism. Peasants were forced to work the lords' land without being able to claim ownership of it. They were also subject to drudgery and royalties, which reduced their ability to benefit from the fruits of their labour. In addition, peasants were often forbidden to leave the lord's land without permission, which tied them to their lord and his land in a way that severely limited their personal freedom. The effect of these policies was felt throughout the social and economic structure of the regions concerned. Although these lands were highly productive and essential for supplying the continent with wheat and other cereals, the peasants who worked them had a hard life and their social status was very low. This reinforcement of servitude in Eastern Europe contrasted sharply with the movement towards greater freedom seen in other parts of Europe at the same time.

The domanial system in Eastern Europe was a form of agrarian organisation in which lords, often aristocrats or members of the upper nobility, established vast agricultural estates. Within these estates, they exercised almost total control over large numbers of peasant serfs, who were tied to the land and forced to work for the lord. This system, also known as serfdom, persisted in Tsarist Russia until the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. Under this system, peasants were referred to in a dehumanising way as "souls", a term that emphasised their reduction to mere economic units in the landowners' registers. Their status as human beings with rights and aspirations was largely ignored. Their living conditions were generally miserable: they did not own the land they farmed and were forced to hand over most of their produce to the lord, keeping only what was strictly necessary for their survival. As a result, they had little incentive to improve yields or innovate in farming techniques, as any surplus would only increase the lord's wealth. The farming practised on these estates was essentially subsistence farming, aimed primarily at avoiding famine rather than maximising production. Nevertheless, despite this focus on mere survival, the large estates managed to produce significant surpluses, particularly of wheat, which was exported to countries such as Germany and France. This was made possible by the vastness of the land and the density of the serfs who worked it. These massive grain exports made these estates almost capitalist in terms of their role in the market economy, even though the system itself was based on feudal production relations and the exploitation of serfs. This paradox highlights the complexity and contradictions of pre-industrial European economies, which were able to combine elements of the market economy with archaic social structures.

At the heart of pre-industrial European agriculture, cereals were the dominant crop, monopolising up to three quarters of farmland. This pre-eminence of cereals, and wheat in particular, has been described by some historians as the "tyranny of wheat". Wheat was crucial because it formed the basis of subsistence food: bread was the staple food of the population, and growing wheat was therefore essential for survival. However, despite this crucial importance, the land did not produce as much as it could. Yields were generally low, a direct consequence of primitive farming techniques and a lack of technological innovation. Farming methods were often archaic, relying on traditional knowledge and rudimentary tools that had not evolved for centuries. What's more, the investment needed to modernise farming practices and increase yields was lacking. Widespread poverty and the prevailing barter-based economic system did not provide fertile ground for the capital accumulation needed to make such investments. The elites, who absorbed the bulk of monetary flows through taxes and rents, did not redistribute wealth in a way that could have stimulated agricultural development. The peasants themselves were financially incapable of adopting advanced techniques. The heavy tax burdens imposed by both the State and the Church, as well as the need to meet the demands of the land lords, left them with few resources to invest in their land. As a result, the technological advances that could have revolutionised agriculture and improved living conditions for farmers did not materialise until the social and economic upheavals of the following centuries changed the landscape of European agriculture.

The issue of soil fertility and livestock management proved to be another limiting factor for pre-industrial agriculture. Manure, whether of animal or human origin, played a crucial role as a natural fertiliser, enriching the soil and boosting crop yields. However, at that time, the supply of manure was often insufficient to meet the needs of all cultivated land, contributing to low farm productivity. The comparison between grazing and cereal growing highlights a central dilemma: while a hectare of land dedicated to grazing can support a limited number of cattle and, by extension, feed a limited number of people with the meat and dairy products produced, the same hectare dedicated to cereal growing has the potential to feed ten times as many people, thanks to the direct production of food consumed by humans. In a context where food security is a major concern and where the majority of the population is dependent on cereal-based foods for their survival, priority is logically given to cereal growing. However, this preference for cereals has been to the detriment of crop rotation and livestock farming, which could have contributed to better soil conditioning and a long-term increase in yields. As a result, in the absence of a sufficient supply of manure and farming practices that maintain soil fertility, cereal production has remained at relatively low levels, perpetuating a vicious circle of low productivity and rural poverty. This is a striking illustration of the constraints faced by pre-industrial farmers and the difficulties inherent in subsistence farming at the time.

Rudimentary farming techniques and limited knowledge of soil science in pre-industrial times led to rapid depletion of soil nutrients. The common practice of continually cultivating the same piece of land without giving it time to recover impoverished the soil, reducing its fertility and therefore crop yields. Fallowing, a traditional method of letting the land rest for one or more growing seasons, was therefore a necessity rather than a choice. During this period, the land was not cultivated and wild plants were often allowed to grow, helping to restore organic matter and essential nutrients to the soil. This was a primitive form of crop rotation that allowed the soil to regenerate naturally. However, fallowing had obvious economic disadvantages: it reduced the amount of land available for food production at any one time, which was particularly problematic given population pressure and the growing demand for food. The absence of modern chemical fertilisers and advanced soil management techniques meant that farmers were largely dependent on natural methods of maintaining soil fertility, such as fallowing, crop rotation and the limited use of animal manure. It was only with the advent of the agricultural revolution and the discovery of chemical fertilisers that agricultural productivity was able to make a significant leap forward, allowing continuous cultivation without the obligatory rest period for the soil.

The "Second Serfdom" refers to a phenomenon that took place in Central and Eastern Europe, particularly between the 14th and 17th centuries, during which the condition of peasants deteriorated considerably, bringing them closer to the state of serfs in the Middle Ages after an earlier period of relative freedom. This reversal was due to a number of factors, including land consolidation by the nobility, economic pressures, and the growing demand for agricultural products for export, particularly cereals. The loss of freedom for peasants meant their subjection to the land and the will of the landowners, which often meant forced labour without adequate remuneration, or with remuneration set by the lords themselves. Peasants were also subject to arbitrary taxes and rents, and could not leave their land or marry off their children without their lord's permission. This led to widespread impoverishment, with peasants unable to accumulate assets or improve their lot, trapped in a cycle of poverty that was perpetuated from generation to generation. This impoverishment of the peasantry also had repercussions on the social and economic structure of these regions, limiting economic development and contributing to social instability. The situation only began to change with the various land reforms and the abolition of serfdom that took place in the 19th century, although the effects of the Second Serfdom continued long after these reforms.

The seigniorial system[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The transition from serfdom to a form of peasant emancipation in Western Europe after the decline of the Roman Empire was a complex phenomenon resulting from a variety of factors. As feudal structures became established, peasants and serfs found themselves in a rigid social hierarchy, but opportunities to change their status began to emerge. As the medieval economy evolved, bonded labour became less profitable for the lords due to changes in the production and circulation of wealth, notably the increased use of money and the development of markets. Faced with these changes, the lords sometimes found it more advantageous to rent out their land to free peasants or tenants, who paid rent rather than relying on the servile system. The expansion of the towns also offered peasants opportunities for employment outside agriculture, putting them in a better position to negotiate their living conditions or seek a better life away from feudal constraints. This influx to urban centres put pressure on the lords to improve conditions for peasants in order to keep them on their land. Peasant uprisings and revolts also influenced feudal relations. Such events sometimes led to negotiations that resulted in more lenient conditions for the peasants. In addition, the authorities sometimes introduced legislative reforms that limited the power of the lords over their serfs and improved conditions for the latter. In certain mountainous regions, such as the Valais and the Pyrenees, farming communities benefited from special conditions. Often collective owners of their pastures, these communities enjoyed a relative autonomy that enabled them to maintain a certain degree of independence. Despite the obligation to perform chores for the lords, they were free and sometimes managed to negotiate terms that were favourable to them. These different regional realities in the West bear witness to the diversity of the experiences of peasants and highlight the complexity of the social and economic structures of the time. The ability of farming communities to adapt and negotiate their status was a determining factor in the evolution of Europe's social and economic history.

The distinction between biennial and triennial crop rotation systems in Western Europe during the Middle Ages and the period preceding industrialisation reflects adaptations to local climatic conditions and soil capacities. These farming practices played a crucial role in the rural economy and in the survival of populations. In southern Europe, regions such as Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal commonly used the biennial crop rotation system. This system divided farmland into two parts: one was sown during the growing season, and the other was left fallow to recuperate. This rest allowed the nutrients to renew themselves naturally, but meant that the farmland was not fully exploited every year. In Northern Europe, on the other hand, where climatic conditions and soil fertility allowed, farmers practised a three-year crop rotation. The land was divided into three sections: one for winter crops, one for spring crops and one for fallow land. This method made better use of the land, as only a third of the land was at rest at any one time, compared with half under two-year rotation. Three-year rotation was more efficient, as it optimised land use and increased agricultural production. This had the effect of increasing the availability of food resources and supporting a larger population. The technique also helped to increase the livestock population, as fallow land could be used for grazing, which was not the case with the biennial system. The transition to three-year cropping in the North was one of the factors that enabled greater resilience and population expansion before the advent of chemical fertilisers and modern farming methods. This regional differentiation reflects the ingenuity and adaptation of European rural societies to the environmental and economic conditions of their time.

The socio-economic divide between Eastern and Western Europe is not an exclusively modern phenomenon. It has its roots in the continent's long history, particularly from the Middle Ages onwards, and has continued down the centuries with distinct features of agrarian and social development. In the East, with the phenomenon of "second serfdom" after the Middle Ages, the freedom of peasants was severely restricted, subjecting them to a regime of servitude to the local nobility and large landowners. This situation gave rise to agricultural structures characterised by large seigneurial farms, where peasants were often unmotivated to improve yields because they did not benefit directly from the fruits of their labour. In the West, on the other hand, although the feudal structure also prevailed, there was a gradual emancipation of the peasants and agricultural development that favoured greater productivity and crop diversity. Practices such as three-year crop rotation, animal husbandry and crop rotation led to increased food production, making it possible to feed a growing population and contribute to urban development. This divergence between Eastern and Western Europe has led to significant differences in economic and social development. In the West, agricultural transformations provided the basis for the Industrial Revolution, while the East often maintained more traditional and rigid agrarian structures, which delayed its industrialisation and helped to perpetuate economic and social inequalities between the two regions. These historical disparities have had lasting repercussions that can still be seen in Europe's contemporary political, economic and cultural dynamics.

A subsistence agriculture[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The transition of peasants from servile status to freedom in Europe in the Middle Ages took place through a multitude of factors that often interacted with each other, and the process was far from uniform across the continent. As the population increased and towns grew, opportunities for work outside traditional agriculture began to emerge, allowing some serfs to aspire to a different life as city dwellers. Changes in farming practices, rising productivity and the beginnings of capitalism with its expanding trade required a freer and more mobile workforce, helping to challenge the traditional servile system. The serfs, for their part, did not always accept their fate unchallenged. Peasant revolts, although often crushed, could sometimes lead to concessions from the nobility. At the same time, certain regions saw legislative reforms that abolished servitude or improved the condition of peasants, under the influence of various factors ranging from economics to ethics. Paradoxically, crises such as the Black Death also played a role in this transformation. The mass death of the population created a labour shortage, giving the surviving peasants greater leeway to negotiate their status and wages. However, despite these advances towards freedom, in the 18th century, while the majority of peasants in Western Europe were free in their own right, their economic freedom often remained limited. Systems of land tenure still required them to pay rents or provide services in exchange for access to land. This was in stark contrast to many parts of Eastern Europe, where servitude persisted, even intensifying in some cases, before finally being abolished in the nineteenth century. The emancipation of Western peasants did not mean, however, that they achieved social equality or total economic independence. Power structures and land ownership remained highly unequal, keeping a large proportion of the rural population in a state of economic dependence, even though their legal status had changed.

In the pre-industrial era, agriculture was the basis of survival for the vast majority of Europeans. This agriculture was strongly oriented towards cereal production, with wheat and barley being the main crops. Peasants produced what they consumed, working essentially to feed their families and to ensure a bare minimum for survival. Cereals were so important that they accounted for three quarters of their diet, hence the expression "tyranny of the wheat", which illustrates the dependence on these crops. At that time, an individual consumed between 800 grams and 1 kilogram of cereals every day, compared with only 150 to 200 grams in modern societies. This high consumption reflects the importance of cereals as a main source of calories. Cereals were preferred to livestock because they were around ten times more productive in terms of food produced per hectare. Cereals could feed a large population, whereas livestock farming required vast tracts of land for a much lower yield in terms of human calories. However, this type of agriculture was characterised by low yields and great vulnerability to crop failure. In the Middle Ages, sowing one grain could yield an average of five to six grains at harvest time. In addition, part of this harvest had to be set aside for future sowing, which meant a lean period when food reserves dwindled before the new harvest. This period was particularly critical, and famines were not uncommon when harvests were insufficient. As a result, the population lived constantly on a knife-edge, with little margin to cope with climatic hazards or epidemics that could decimate the crops and, consequently, the population itself.

Medieval farming techniques were limited by the technology of the time. Iron production was insufficient and expensive, which had a direct impact on agricultural tools. Ploughshares were often made of wood, a much less durable and efficient material than iron. A wooden ploughshare wore out quickly, reducing the efficiency of ploughing and limiting farmers' ability to cultivate the land effectively. The vicious circle of poverty exacerbated these technical difficulties. After the harvest, farmers had to sell much of their grain for flour and pay various taxes and debts, leaving them with little money to invest in better tools. The lack of money to buy an iron ploughshare, for example, prevented improvements in agricultural productivity. Better equipment would have enabled the land to be cultivated more deeply and more efficiently, potentially increasing yields. Moreover, reliance on inefficient tools limited not only the amount of land that could be cultivated, but also the speed at which it could be cultivated. This meant that even if agricultural knowledge or climatic conditions allowed for better production, material limitations placed a ceiling on what the agricultural techniques of the time could achieve.

Soil fertilisation was a central issue in pre-industrial agriculture. Without the use of modern, effective chemical fertilisers, farmers had to rely on animal and human excrement to maintain the fertility of arable land. The Île-de-France region is a classic example where dense urbanisation, as in Paris, could provide substantial quantities of organic matter which, once processed, could be used as fertiliser for the surrounding farmland. However, these practices were limited by the logistics of the time. The concentration of livestock farming in mountainous regions was partly due to the geographical characteristics that made these areas less suitable for intensive cereal farming but more suited to grazing due to their poor soil and rugged terrain. The Alps, Pyrenees and Massif Central are examples of such areas in France. Transporting manure over long distances was prohibitively expensive and difficult. Without a modern transport system, moving large quantities of something as heavy and bulky as manure represented a major logistical challenge. The "tyranny of cereals" refers to the priority given to growing cereals to the detriment of livestock farming, and this prioritisation had consequences for soil fertility management. Where livestock farming was practised, manure could be used to fertilise the soil locally, but this did not benefit remote cereal-growing regions, which needed it badly to increase crop yields. Managing soil fertility was complex and was subject to the constraints of the agrarian economy of the time. Without the means to transport fertiliser efficiently or the existence of chemical alternatives, maintaining soil fertility remained a constant challenge for pre-industrial farmers.

Low cereal yields[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Yields remain low[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Agricultural yield is the ratio between the quantity of product harvested and the quantity sown, generally expressed in terms of grain harvested for each grain sown. In pre-industrial agricultural societies, low yields could have disastrous consequences. Poor harvests were often caused by adverse weather conditions, pests, crop diseases or inadequate farming techniques. When the harvest failed, the people who depended on it for their livelihood faced food shortages. Famine could result, with devastating effects. The "law of the strongest" can be interpreted in several ways. On the one hand, it can mean that the most vulnerable members of society - the young, the old, the sick and the poor - were often the first to suffer in times of famine. On the other hand, in social and political terms, it could mean that the elites, with better resources and more power, were able to monopolise the remaining resources, thereby reinforcing existing power structures and accentuating social inequalities. Famine and chronic malnutrition were drivers of high mortality in pre-industrial societies, and the struggle for food security was a constant in the lives of most peasants. This led to various adaptations, such as food storage, diversified diets and, over time, technological and agricultural innovation to increase yields and reduce the risk of famine.

Agricultural yields in the Middle Ages were significantly lower than those that modern agriculture has managed to achieve thanks to technological advances and improved cultivation methods. Yields of 5-6 to 1 are considered typical for certain European regions during this period, although these figures can vary considerably depending on local conditions, cultivation methods, soil fertility and climate. The case of Geneva, with a yield of 4:1, is a good illustration of these regional variations. It is important to remember that yields were limited not only by the technology and agricultural knowledge of the time, but also by climatic variability, pests, plant diseases and soil quality. Medieval agriculture relied on systems such as three-year crop rotation, which improved yields somewhat compared with even earlier methods, but productivity remained low by modern standards. Farmers also had to save part of their harvest for sowing the following year, which limited the amount of food available for immediate consumption.

Reasons for poor performance[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The "tyranny of cereals" characterises the major constraints of pre-industrial agriculture. Soil fertility, crucial for good harvests, depended heavily on animal manure and human waste, in the absence of chemical fertilisers. This dependence posed a particular problem in mountainous areas, where the remoteness of livestock farms limited access to this natural fertiliser, reducing crop yields. The cost and logistics of transport, at a time when there were no modern means of transport, made the transfer of goods such as manure, essential for fertilising fields, both costly and impractical over long distances. The farming methods of the time, with their rudimentary tools and poorly-developed ploughing and sowing techniques, did nothing to improve the situation. Wooden ploughs, less efficient than their metal counterparts, were unable to exploit the full potential of cultivated land. What's more, the diet of the time was dominated by the consumption of cereals, seen as a reliable and storable source of calories for times of shortage, particularly in winter. This focus on cereals hindered the development of other forms of agriculture, such as horticulture or agroforestry, which could have proved more productive. The social and economic structure of the feudal system only exacerbated these difficulties. Peasants, weighed down by the weight of royalties and taxes, had little means or incentive to invest in improving their farming practices. And when the weather turned out to be unfavourable, harvests could be seriously affected, as medieval societies had few strategies for managing the risks associated with climatic hazards. In such a context, agricultural production focused more on survival than on profit or the accumulation of wealth, limiting the possibilities for the evolution and development of agriculture.

The low level of investment in pre-industrial agriculture is a phenomenon rooted in several structural aspects of the period. Farmers were often hampered by a lack of financial resources to improve the quality of their tools and farming methods. This lack of capital was exacerbated by an oppressive tax system that left peasants little room to accumulate savings. The tax burden imposed by the nobility and feudal authorities meant that most harvests and income went towards meeting the various taxes and levies, rather than being reinvested in the farm. What's more, the socio-economic system was not conducive to capital accumulation, as it was structured in such a way as to keep peasants in a position of economic dependence. Such was the precariousness of the peasants' situation that they often had to concentrate on satisfying immediate survival needs, rather than on long-term investments that could have improved yields and living conditions. This lack of means for investment was reinforced by the lack of access to credit and an aversion to risk justified by the frequency of natural hazards, such as bad weather or plagues like locust infestations and plant diseases, which could wipe out harvests and, with them, the investments made.

The stereotype of the conservative peasant has its roots in the material and socio-economic conditions of pre-industrial societies. In these societies, subsistence farming was the norm: it aimed to produce enough to feed the farmer and his family, with little surplus for trade or investment. This mode of production was closely linked to natural rhythms and traditional knowledge, which had proved its worth over generations. Farmers depended heavily on the first harvest to see them through to the next. So any change in farming methods represented a considerable risk. If they failed, the consequences could be disastrous, ranging from famine to starvation. As a result, deviating from tried and tested practices was not only seen as imprudent, it was a direct threat to survival. Resistance to change was therefore not simply a question of mentality or attitude, but a rational reaction to conditions of uncertainty. Innovation meant risking upsetting a fragile balance, and when the margin between survival and starvation is thin, caution takes precedence over experimentation. Farmers could not afford the luxury of mistakes: they were the managers of a system in which every grain, every animal and every tool was of vital importance. Moreover, this caution was reinforced by social and economic structures that discouraged risk-taking. Opportunities for diversification were limited, and social support systems or insurance against crop failure were virtually non-existent. Farmers often had debts or obligations to landowners or the state, forcing them to produce safely and constantly to meet these commitments. The stereotype of the conservative peasant is therefore part of a reality where change was synonymous with danger, and where adherence to tradition was a survival strategy, dictated by the vagaries of the environment and the imperatives of a precarious life.

Maintaining soil fertility was a constant challenge for medieval farmers. Their dependence on natural fertilisers such as animal and human dung underlines the importance of local nutrient loops in agriculture at the time. The concentration of population in urban centres such as Paris created abundant sources of organic matter which, when used as fertiliser, could significantly improve the fertility of the surrounding soils. This partly explains why regions such as the Île-de-France were renowned for their fertile soil. However, the agricultural structure of the time meant that there was a geographical separation between livestock farming and cereal-growing areas. Livestock farms were often located in mountainous areas with less fertile soils, where the land was unsuitable for intensive cereal growing but could support grazing. Grazing areas such as the Pyrenees, the Alps and the Massif Central were therefore far from cereal-growing regions. Transporting the fertiliser was therefore problematic, both in terms of distance and cost. Transport techniques were rudimentary and costly, and infrastructure such as roads was often in poor condition, making the movement of bulky materials such as manure economically unviable. As a result, cereal fields often lacked the nutrients they needed to maintain or improve their fertility. This situation created a vicious circle in which the land was depleted faster than it could be regenerated naturally, leading to lower yields and increased pressure on farmers to feed a growing population.

The perception of gridlock in medieval agricultural societies stems in part from the economic structure of the time, which was predominantly rural and based on agriculture. Agricultural yields were generally low, and technological innovation slow by modern standards. This was due to a number of factors, including a lack of advanced scientific knowledge, few farming tools and techniques available, and a certain resistance to change due to the risks associated with trying out new methods. In this context, the urban class was often perceived as an additional burden for farmers. Although urban dwellers depended on agricultural production for their survival, they were also often seen as parasites in the sense that they consumed surpluses without contributing directly to the production of these resources. The townsfolk, who included merchants, craftsmen, clerics and the nobility, were dependent on the peasants for their food, but did not always share the burdens and benefits of agricultural production equally. The result was an economic system where the peasants, who formed the majority of the population, worked hard to produce enough food for everyone, but saw a significant proportion of their harvest consumed by those not involved in production. This could create social and economic tensions, especially in years of poor harvests when surpluses were limited. This dynamic was exacerbated by the feudal system, where land was held by the nobility, who often imposed taxes and drudgery on the peasants. This further limited peasants' ability to invest in improvements and accumulate surpluses, maintaining the status quo and hindering economic and technological progress.

The law of 15% by Paul Bairoch[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Societies under the Ancien Régime had very strict economic constraints linked to their agricultural base. The ability to support a non-farming population, such as that living in cities, was directly dependent on agricultural productivity. Since agricultural techniques of the time severely limited yields, only a small fraction of the population could afford not to participate directly in food production. The statistics illustrate this dependence. If 75% to 80% of the population had to work in agriculture to meet the food needs of the entire population, this left only 20% to 25% of the population for other tasks, including vital functions within society such as trade, crafts, the clergy, administration and education. In this context, urban dwellers, who represented around 15% of the population, were perceived as 'parasites' in the sense that they consumed resources without contributing directly to their production. However, this perception overlooks the cultural, administrative, educational and economic contribution that these city dwellers made. Their work was essential to the structuring and functioning of society as a whole, although their dependence on agricultural production was an undeniable reality. The activities of city dwellers, including those of craftsmen and tradesmen, did not cease with the seasons, unlike those of peasants, who were less active in winter. This reinforced the image of city dwellers as members of society who lived at the expense of the direct producers, the peasants, whose labour was subject to the vagaries of the seasons and the productivity of the land.

The law of 15% formulated by the historian Paul Bairoch illustrates the demographic and economic limitations of agricultural societies before the industrial era. This law stipulates that a maximum of 15% of the total population could be made up of city dwellers, i.e. people who did not produce their own food and were therefore dependent on agricultural surpluses. During the Ancien Régime, the vast majority of the population - between 75 and 80% - was actively engaged in agriculture. This high proportion reflects the need for an abundant workforce to meet the population's food requirements. However, as farming was a seasonal activity, farmers did not work during the winter, which meant that in terms of the annual workforce, it was estimated that 70-75% was actually invested in agriculture. Based on these figures, this would leave 25 to 30% of the workforce available for activities other than farming. However, it is important to bear in mind that even in rural areas there were non-farm workers, such as blacksmiths, carpenters, priests and so on. Their presence in the countryside reduced the amount of labour that could be allocated to the towns. Taking all these factors into account, Bairoch concluded that the urban population, i.e. those living from non-agricultural activities in the towns, could not exceed 15% of the total. This limit was imposed by the productive capacity of agriculture at the time and the need to provide food for the entire population. As a result, pre-industrial societies were predominantly rural, with urban centres remaining relatively modest in relation to the overall population. This reality underlines the precarious balance on which these societies were based, as they could not support a growing number of city-dwellers without risking their food security.

The concept evoked by Paul Bairoch in his book "From Jericho to Mexico" highlights the link between agriculture and urbanisation in pre-industrial societies. The estimate that urbanisation rates remained below 15% until the Industrial Revolution is based on a historical analysis of available demographic data. Although the adjustment of 3 to 4 may seem arbitrary, it serves to reflect the margin needed for activities other than agriculture, even taking into account craftsmen and other non-agricultural occupations in rural areas. This urbanisation limit was indicative of a society where most resources were devoted to survival, leaving little room for investment in innovations that could have boosted the economy and increased agricultural productivity. Cities, historically the centres of innovation and progress, were unable to grow beyond this 15% threshold because agricultural capacity was insufficient to feed a larger urban population. However, this dynamic began to change with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. Technological innovations, particularly in agriculture and transport, led to a spectacular increase in agricultural yields and a reduction in transport costs. These developments freed part of the population from the need for agricultural labour, allowing for increased urbanisation and the emergence of a more economically diverse society, where innovation could flourish in an urban environment. In other words, while the societies of the Ancien Régime were confined to a certain stasis due to their agricultural limitations, technological progress gradually unlocked the potential for innovation and paved the way for the modern era.

Societies of mass poverty[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

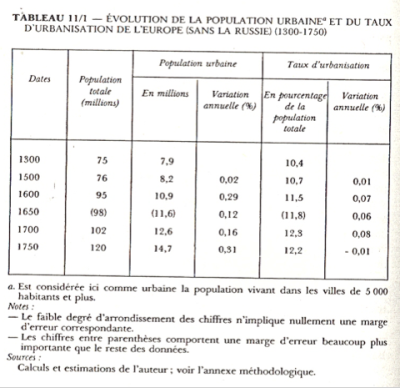

This table provides an overview of the demographic and urbanisation progression in Europe between 1300 and 1750. During this period, the European population grew from 75 million to 120 million, reflecting gradual demographic growth despite historical hazards such as the Black Death, which greatly reduced the population in the 14th century. There has also been a trend towards urbanisation, with the number of people living in cities rising from 7.9 to 14.7 million. This urbanisation is slow, however, and does not reflect large-scale migration to cities, but rather their constant development. The percentage of the population living in urban areas remains below 15%, reinforcing the idea of a pre-industrial, mainly agricultural society. The annual variation in the rate of urbanisation and in the total population is fairly small, indicating gradual demographic changes rather than rapid or radical transformations. This suggests that demographic change and urbanisation in Europe were the result of slow and stable evolutions, marked by a gradual development of urban infrastructures and a growing, albeit modest, capacity of cities to support a larger population. In short, these data depict a Europe that is slowly moving towards a more urbanised society, but whose roots remain deeply rooted in agriculture, with cities serving more as commercial and administrative centres than industrial production hubs.

Living conditions in pre-industrial agricultural societies were extremely harsh and could have a significant impact on people's health and longevity. Subsistence farming, intense physical labour, limited diets, poor hygiene and limited access to medical care contributed to high infant mortality and low life expectancy. An average life expectancy of around 25 to 30 years does not mean, however, that most people died at that age. This figure is an average influenced by the very large number of deaths of infants. Children who survived childhood had a reasonable chance of reaching adulthood and living to 50 or more, although this was less common than it is today. An individual reaching 40 was certainly considered older than by today's standards, but not necessarily an 'old man'. However, the wear and tear on the body due to strenuous manual labour from an early age could certainly give the appearance and aches associated with early old age. People often suffered from dental problems, chronic illnesses and general wear and tear on the body that made them look older than a person of the same age would today, with access to better healthcare and a more varied diet. Epidemics, famines and wars exacerbated this situation, further reducing the prospects of a long and healthy life. This is why the farming population of the time, faced with a precarious existence, often had to rely on community solidarity to survive in such an unforgiving environment.

Malnutrition was a common reality for farmers in pre-industrial societies. The lack of dietary diversity, with a diet often centred on one or two staple cereals such as wheat, rye or barley, and insufficient consumption of fruit, vegetables and proteins, greatly affected their immune systems. Deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals could lead to various deficiency diseases and weaken resistance to infection. Farmers, who often lived in precarious hygiene conditions and in close proximity to animals, were also exposed to a variety of pathogens. A 'simple' flu, in such a context, could prove far more dangerous than in a well-nourished and healthy population. Lack of medical knowledge and limited access to healthcare exacerbated the situation. These populations were also confronted with periods of famine, due to insufficient harvests or natural disasters, which further reduced their ability to feed themselves properly. In times of famine, opportunistic diseases could spread rapidly, transforming benign ailments into fatal epidemics. In addition, periods of war and requisitioning could worsen the food situation of peasants, making malnutrition even more frequent and severe.

In 1588, the Roman Gazette ran the headline "À Rome rien de neuf sinon que l'on meurt-de-faim" (Nothing new in Rome except that people were dying of hunger) while the Pope was giving a banquet. These were societies of mass poverty reflected in a precarious situation. There is a striking contrast between the social classes in pre-industrial societies. By reporting on the famine in Rome at the same time as a papal banquet, the Roman Gazette highlights not only social inequality but also the indifference or powerlessness of the elites in the face of the suffering of the most disadvantaged. Mass poverty was a feature of Ancien Régime societies, where the vast majority of the population lived in constant precariousness. Subsistence depended entirely on agricultural production, which was subject to the vagaries of weather, pests, crop disease and war. A poor harvest could quickly lead to famine, exacerbating poverty and mortality. The elites, be they ecclesiastics, nobles or bourgeois in the towns, had far greater means at their disposal and were often able to escape the most serious consequences of famines and economic crises. Banquets and other displays of wealth in times of famine were seen as signs of opulence out of touch with the realities of the people. This social divide was one of the many reasons that could lead to tensions and popular uprisings. History is punctuated by revolts in which hunger and misery drove people to rise up against an order deemed unjust and insensitive to their suffering.