Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory

Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory ● The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic ● Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory ● The notion of "concept" in social sciences ● History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts ● Marxism and Structuralism ● Functionalism and Systemism ● Interactionism and Constructivism ● The theories of political anthropology ● The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas ● Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science ● An analytical approach to institutions in political science ● The study of ideas and ideologies in political science ● Theories of war in political science ● The War: Concepts and Evolutions ● The reason of State ● State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance ● Theories of violence in political science ● Welfare State and Biopower ● Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes ● Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences ● The system of government in democracies ● Morphology of contestations ● Action in Political Theory ● Introduction to Swiss politics ● Introduction to political behaviour ● Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy ● Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation ● Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation ● Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations ● Introduction to Political Theory

Political science is a constantly evolving field of research, with a variety of theories and approaches proposed by major thinkers such as Durkheim and Bourdieu. In this article, we will examine the political science approaches of these two major figures in sociology and their impact on our understanding of politics as a complex and dynamic social phenomenon. We begin with an analysis of Durkheim's holistic approach, which emphasises the importance of institutions and social norms in political life, before examining Bourdieu's more radical critique, which stresses the influence of social and cultural capital on politics.

Durkheim, regarded as the founding father of sociology, proposed a holistic approach to politics that emphasised the importance of institutions and social norms in political life. According to Durkheim, politics is a mechanism for maintaining social cohesion by guaranteeing harmony between individuals and social groups. He saw the division of political labour as a manifestation of the division of social labour, and saw the state as a symbol of organic solidarity. Pierre Bourdieu, on the other hand, proposed a more critical approach to politics, in which he emphasised the influence of social and cultural capital on political life. According to Bourdieu, politics is a power struggle that takes place in a political field marked by social and cultural inequalities. He considered that political actors, such as political parties and voters, are subject to rules and practices.

The life of Emile Durkheim: 1858 - 1917[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) is one of the founders of modern sociology. Born in Épinal in Lorraine, France, his life and work were influenced by the complex historical context in which he grew up and worked. Durkheim studied at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris and became a professor, teaching sociology and pedagogy. He sought to establish sociology as a distinct science with its own study and research methods. His perspective was that societies were more than the sum of their individuals but complex entities with their own characteristics and laws. Durkheim lived during a period of social and political upheaval in France. The Paris Commune, which took place in 1871, was a revolt against the French government that was violently repressed. This period, with its social tensions and conflicts, undoubtedly helped shape Durkheim's vision of society and the importance of social solidarity. Durkheim is best known for his work on anomie, suicide, the division of social labour, religion and social solidarity. He argued that modern societies were characterised by organic solidarity, based on the mutual dependence of individuals due to the specialisation of labour. This contrasted with the mechanical solidarity of more traditional societies, based on the similarity of individuals.

The first questions he asked himself were: what factors led one part of society to take up arms against the most deprived, and what led to the apparent dissolution of society? This question reflects Durkheim's concerns about social cohesion and moral order. He was deeply concerned about the conditions that could lead to social breakdown, or what he called anomie - a state of lack of norms or rules, disorientation and insecurity.

On the question of why a section of society would be willing to arm itself to attack the poorest, Durkheim would probably have pointed to social and economic divisions, as well as the absence of social solidarity. He saw solidarity as the glue that holds a society together, and when this solidarity is weakened, there can be conflict and violence. For Durkheim, social cohesion is based on two types of solidarity: mechanical solidarity, which is based on similarity and is typical of traditional or primitive societies, and organic solidarity, which is based on difference and mutual dependence and is typical of modern, industrialised societies. The transition from mechanical to organic solidarity can be tumultuous and can lead to social conflict. As for the question of why there is no longer a society, Durkheim saw society as more than just a collection of individuals. For him, a society is a complex system of social relations, norms, values and beliefs. If these social bonds are weakened, for example by extreme economic inequality, political conflict or rapid social change, then society itself can appear to disintegrate. This is what he called anomie.

Durkheim lived and worked at a time when the ideals of the Republic, such as liberty, equality and fraternity, were important in French political and social thought. It was also a time when socialism began gaining influence as a political and economic ideology. Durkheim himself was not a socialist, but he recognised the importance of social and economic issues in shaping society. He sought to understand how societies could maintain their cohesion despite economic and social divisions and stressed the importance of social solidarity in maintaining order and stability. In this context, Durkheim developed his theory of mechanical and organic solidarity. In modern societies, he argued that social cohesion depends less on the similarity of individuals (as in mechanical solidarity) than on their economic and social interdependence (as in organic solidarity). Durkheim emphasised the importance of social institutions, such as education, in promoting solidarity and preventing anomie. He saw education as a means of transmitting the values and social norms that bind a society together.

For Durkheim, the social bond or solidarity is the glue that holds a society together. He sought to understand how these bonds are created and maintained, and how they can be broken, leading to social problems such as anomie. Durkheim defined two types of solidarity: mechanical and organic. Mechanical solidarity is typical of traditional or primitive societies, where individuals are very similar in their values, beliefs and way of life. Organic solidarity, on the other hand, is typical of modern societies, where individuals are highly differentiated by their work and social roles, but are linked by their mutual dependence. For Durkheim, the scientific study of social facts was essential to understanding society. In his view, social facts are phenomena that exist independently of particular individuals. They are "external" to the individual and "coercive", meaning they constrain the individual. This includes things like social norms and values, social institutions, laws, customs and so on. By understanding how these social facts work, Durkheim believed we could better understand how society is held together, how social conflicts can be resolved, and how to prevent problems such as anomie. In this sense, Durkheim saw sociology not only as a science, but also as a tool for improving society.

The questions posed by Durkheim remain relevant today. The question of solidarity, or what unites a society, is still at the heart of sociological debates. We live in an increasingly interconnected world, where economic, political and technological changes constantly reshape our societies. Understanding how these changes affect our social cohesion is a fundamental question. Durkheim lived at a time of rapid social change, transitioning from a predominantly rural to a predominantly urban and industrial society. He saw these changes as a transition from mechanical to organic solidarity. Social facts", according to Durkheim, are phenomena that have an existence independent of individuals. He argued that these social facts can be studied scientifically, just like natural phenomena in physics or biology. This includes not only obvious social institutions such as the family or education, but also more abstract phenomena such as social norms, values, collective beliefs, etc. So, to interpret an event (such as social conflict, political change, or even an individual phenomenon like suicide), Durkheim would say that we need to understand it in terms of social facts. For example, in his study of suicide, he sought to understand how social factors (such as the degree of social cohesion, religious norms, etc.) influence suicide rates.

These works help us to understand today's world. Each of these works helped to establish sociology as a distinct scientific discipline and to define its object of study: social facts.

- "On the Division of Social Labour (1893): In this work, Durkheim examines how the division of labour, or the specialisation of roles in society, has changed social relations. He argues that the division of labour has led to a new form of solidarity, which he calls organic solidarity, based on mutual dependence rather than sameness.

- "The Rules of Sociological Method" (1895): This work is essentially a statement of Durkheim's scientific method for studying social facts. In it, he defines social facts as external and coercive phenomena that can be studied objectively, independently of individual preferences or beliefs.

- "Suicide (1897): In this work, Durkheim applies his method to study a particular phenomenon: suicide. He shows that suicide, although often considered a deeply personal act, can be understood as a social fact that is influenced by social factors such as religion, marriage and social integration. He divides suicide into three main types: selfish suicide, altruistic suicide and anomic suicide.

This work laid the foundations of sociology as an academic discipline and continues to influence the way we understand society today. They illustrate Durkheim's approach that sociology should focus on social structures and social forces rather than individual actions.

Durkheim was not a 'thinker' in the sense that he did not simply reflect abstractly on ideas but was a keen observer of society who sought to understand the forces and structures that shape it. He saw sociology as an empirical science that should be based on the systematic observation and analysis of social facts. He sought to identify the social structures and forces underlying observable phenomena, such as the division of labour, suicide or religion. Durkheim focused on the contradictions and tensions in society, such as the conflict between the individual and the collective or between tradition and modernism. He saw these contradictions as driving forces of social change. So while Durkheim was certainly a thinker - his ideas have profoundly influenced sociology and other disciplines - he was also an observer and analyst of society. He aimed to understand society empirically and scientifically, based on observable facts rather than theoretical speculation.

The Dreyfus Affair had a significant impact on Durkheim and his work. The apparent injustice of the situation - a French army officer, Alfred Dreyfus, who was falsely accused of espionage, largely because of his ethnic and religious background - highlighted for Durkheim the dangers of irrationality and intolerance in society. This led him to give more thought to the question of morality and ethics in social relations. For Durkheim, society is not just a collection of individuals but a moral and ethical system. The Dreyfus Affair highlighted for him the need for a fair and impartial system of justice that respects the individual's rights. Durkheim was also strongly influenced by laïcité, a key idea of the French Republic that separates church and state. Although he recognised the important role of religion in creating solidarity and a sense of community, he argued that secularism was necessary to preserve individual freedom and avoid religious conflict. As far as socialism was concerned, Durkheim saw solidarity as a key element of this philosophy. For him, socialism was not just about economic equality but also about social solidarity - the recognition that all members of society are interconnected and dependent on each other. He believed that individuals would act more aggressively and altruistically when they became aware of this interconnectedness. Although Durkheim supported the importance of solidarity and social justice, he was not himself a militant or revolutionary. His main contribution was to provide a sociological analysis of these issues, helping to understand how solidarity is created and maintained in a complex and diverse society.

Émile Durkheim became professor of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1887, making him one of the first sociology professors in France. Durkheim worked on issues of morality and ethics and was deeply affected by the events of the First World War. His son André was killed in action in 1916, which was a devastating blow for Durkheim. This tragic event significantly impacted him and probably influenced his work on issues of war, conflict and social cohesion. Durkheim died in 1917, apparently of exhaustion and grief following the death of his son. His work continued to have a major influence on sociology and other social science disciplines long after his death, and he is still widely read and cited today.

The social fact[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In "The Rules of Sociological Method", Durkheim defines social facts as ways of acting, thinking and feeling that are external to the individual and that are endowed with a power of coercion by virtue of which they are imposed on him. For Durkheim, social facts must be considered as things, that is, as objective entities that can be studied independently of individual perceptions and evaluations. For him, social facts have a reality of their own, distinct from that of the individuals who make up society. They are "general" in that they are not limited to individual actions but represent patterns of behaviour common to a group, a society or a culture. Social facts have an existence of their own, independent of their individual manifestations. They may take the form of laws, customs, beliefs, fashions, values, etc., which influence and constrain the behaviour of individuals. Another important aspect of Durkheim's definition is that these phenomena are sufficiently frequent and widespread to qualify as 'collective'. These ideas played a fundamental role in establishing sociology as a scientific discipline distinct from psychology or philosophy. By focusing on social facts, Durkheim enabled sociology to concentrate on the social structures and processes that shape human behaviour.

Both individual and collective factors can condition ways of acting. Durkheim recognised that individuals have their own perceptions, experiences and individual characteristics that influence their behaviour. However, he also argued that individual actions are shaped and guided by collective determinants, i.e. shared norms, values, customs and expectations within a given society. Durkheim emphasised that individuals are socially integrated and act according to the norms and expectations of their social group. These norms and expectations provide patterns of behaviour or 'standard responses' that are commonly accepted and observed in a given society. These standard reactions may include behaviours, attitudes, values, beliefs or ways of thinking that are shared by many members of the society. Thus, ways of acting are influenced both by individual factors, such as subjective experiences and perceptions and by collective determinants, such as social norms and shared expectations. Durkheim believed that the analysis of social facts had to take account of this complex interaction between the individual and the collective to fully understand behaviour and actions in a given society.

According to Durkheim, social facts meet four criteria:

- Externality: according to Durkheim, social facts are external to individuals. They are the product of society as a whole and not of individual actions or decisions. They exist independently of any particular individual and endure even after the individual's death. Moreover, social facts have a binding force on individuals. They dictate how individuals should behave in different situations and social contexts. If an individual does not comply with these social norms and rules, society may punish him or her. In addition, social facts have a certain permanence over time. They are more durable than the life of an individual. They may change and evolve over time, but they do not disappear easily. This permanence gives social life a certain stability and predictability. Finally, the exteriority of social facts means that they are independent of the will and control of individuals. Individuals cannot simply decide to change a social fact as they please. They have to conform to these social facts, whether they want to or not.

- Coercion: Coercion is an essential characteristic of social facts. It is exerted on individuals in various ways and at different levels, including through social norms, laws, rules, expectations, rituals, traditions and customs. In the context of Durkheim's theory, coercion is not necessarily negative or oppressive. It is a means by which society ensures its coherence and order. It facilitates coordination and cooperation between individuals and helps to maintain social stability. For example, social norms compel individuals to behave in a certain way in certain situations. If an individual breaks these norms, he or she may be punished by society through formal sanctions (e.g. legal sanctions) or informal sanctions (e.g. social disapproval). Coercion can also take the form of more subtle influences, such as pressure to conform to social expectations or to follow certain traditions or customs. For example, the social expectation that individuals should marry and have children can be seen as a form of coercion. Coercion is a force that shapes people's behaviour and ensures social cohesion. It is omnipresent in society and influences all aspects of social life.

- Generality: Durkheim emphasised generality as one of the key characteristics of a social fact. For a phenomenon to be considered a social fact, it must be widespread in a society at a given time. This means that social facts are not isolated events or individual behaviours, but patterns of behaviour that are widely shared by the members of a society. For example, customs, traditions, laws, social norms, institutions, ways of thinking, etc., are all examples of social facts because they are common to most members of society. Generality does not mean that every individual in a society necessarily conforms to the social fact, but rather that the social fact is generally accepted and practised by the majority. For example, although not everyone in a society necessarily adheres to the same religious beliefs, religion itself is a social fact because it is an institution that is widely accepted and practised in society. What's more, the generality of a social fact can vary from society to society and from period to period. For example, what is considered an acceptable social norm may vary from one society to another and from one era to another. This shows that social facts are dynamic and evolve with time and the social context.

- The historical criterion: The historical criterion is another essential element in Durkheim's definition of social facts. For a phenomenon to be considered a social fact, it must not only be widespread, but it must also have a certain duration over time. A new phenomenon or trend only becomes a social fact when it has had time to spread widely within society and become integrated into its structures and practices. In other words, a social phenomenon must be rooted in the history of society. The importance of the historical criterion is linked to the notion of the stability of social facts. Although they may change and evolve over time, social facts generally have a certain permanence and resist rapid change. An example of applying the historical criterion in analysing social facts could be the evolution of the use of digital technology and the Internet. In the beginning, computer researchers and technology professionals mainly used the Internet and computers. Over time, however, their use has spread to all strata of society. Today, the use of the Internet and digital technologies is a social fact in itself - it transcends individuals and groups. It has a coercive force, forcing people to use it for communication, work, education, etc. It is also an example of the "digital divide". It is also an example of how social facts can evolve and change over time. As digital technologies develop and spread, the norms and behaviours associated with their use also change. For example, a few decades ago, sending letters through the post was common practice. This is much less common today, replaced by electronic communications such as emails and instant messages. So the widespread use of the Internet and digital technology is an example of a social fact that has emerged and developed over time. A new phenomenon or trend only becomes a social fact when it has had time to spread widely within society and become integrated into its structures and practices. In other words, a social phenomenon must be rooted in the history of society. The importance of the historical criterion is linked to the notion of the stability of social facts. Although they may change and evolve over time, social facts generally have a certain permanence and resist rapid change.

To study social facts scientifically, Durkheim argued that they had to be treated as 'things' (or 'objects'). By this he did not mean that they were material or tangible in the same sense as physical objects, but rather that they had to be considered as entities independent of our individual perceptions or value judgements. According to Durkheim, social facts have a reality that exists independently of the individual. They are external to the individual and constrain him or her. They have characteristics that can be observed, described and analysed. They are not simply ideas or perceptions in our minds but concrete aspects of social reality that influence our behaviour. So, to study social facts, we need to adopt an objective and scientific approach. We must observe and analyse them impartially without letting our personal prejudices or opinions influence our understanding. We must measure and quantify them as far as possible, use rigorous methods to test our hypotheses and theories, and always be ready to revise our ideas in the light of new evidence. It also means that we must strive to understand social facts systematically and holistically, taking account of all relevant factors and seeking to discover the underlying laws that govern them. We must not simply explain social facts in terms of individual motivations or intentions but seek to understand how they are produced and maintained by wider social structures and processes.

According to Durkheim, what 'makes society' is a combination of social facts that manifest themselves through the institutions, norms, values, rules, practices, beliefs and behaviours that are shared by the members of a community. These social facts create the structure and order of society and govern interactions between individuals. Collective representations, an important notion in Durkheim's theory, play a central role in the formation of society. Collective representations are ideas, beliefs or values shared by the members of society. They are the product of social interaction and help to form the collective consciousness, i.e. the common framework of thought and understanding that unites the members of a society. They provide a common basis for communication and interaction, and create a sense of belonging and collective identity. For example, a given society may have a collective representation that education is important. This collective representation may manifest itself through social institutions such as the education system, social norms such as the expectation that children will go to school, and individual behaviours such as studying and learning. Thus, for Durkheim, what "makes society" is the set of social facts, including collective representations, which provide structure and order to social life, and which unite individuals into a coherent and functional community.

Durkheim drew an important distinction between individual and collective representations. Individual representations, also known as 'pre-notions', are the ideas, beliefs and perceptions that an individual has based on his or her personal experience and subjective interpretation of his or her environment. They are unique to each individual and are constantly evolving. Collective representations, on the other hand, are ideas, beliefs and values shared by the members of a society. They are the product of social interaction and are embedded in society's institutions, norms and practices. They are relatively stable and durable, and transcend individuals. Collective representations play a central role in the formation and maintenance of society. They provide a common framework of thought and understanding that unites the members of a society and guides their interactions. They are also a key element of social facts, which are the phenomena that result from collective activity and which exert a constraint on individuals. However, Durkheim insisted that to study social facts scientifically, it was necessary to go beyond individual representations and focus on collective representations. Individual representations are too variable and subjective to provide a basis for sociological analysis. Collective representations, on the other hand, can be observed, measured and analysed, and can help us to understand social structures and processes.

The idea that crime has a function in society may seem counter-intuitive, but it is central to Durkheim's theory. For Durkheim, crime is a social fact and, like all social facts, it has a function in society. Here's how he sees it:

- Normality of crime: Durkheim argued that crime is a normal phenomenon because it exists in all societies. Its universal existence suggests that it fulfils certain social functions or is an inevitable consequence of social life.

- Reinforcing norms and values: Crime plays an important role in reinforcing social norms and values. When a crime is committed, society often reacts with outrage and punishment, reinforcing adherence to the violated norm and reminding all members of society of the importance of respecting norms.

- Social change function: Crime can also play a role in social change. In certain circumstances, criminal acts can highlight the unfairness or inadequacy of existing norms and can lead to changes in those norms.

- Social cohesion function: Finally, crime can promote social cohesion by creating a sense of unity among members of society against the criminal.

Durkheim does not justify or glorify crime. On the contrary, he seeks to understand its sociological role. In his view, a crime-free society is impossible because there will always be individuals who deviate from social norms. Moreover, a society without deviance would be sterile and incapable of change and evolution.

The forms of social solidarity[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The fundamental thing is to work on the organisation of the community. What is at stake in our modern societies? In modern societies, there is a more marked division of labour, with greater specialisation and differentiation of roles and tasks. This leads to greater individual independence because each person has their own specific and distinct role. This independence also translates into greater individual freedom and various ways of living one's life. However, at the same time, this specialisation means that individuals are more dependent on each other. For example, an individual may be an excellent doctor, but he or she depends on other people to produce food, build houses, manage the town's infrastructure, etc. In other words, although each individual may have a more independent role, society as a whole functions thanks to a strong interdependence between its members. This paradox lies at the heart of organic solidarity: while each individual becomes more distinct and independent, society as a whole becomes more integrated and interconnected.

Durkheim developed the concept of anomie to describe a social condition where there is a breakdown or diminution of the norms and values that govern the behaviour of individuals in a society. Anomie often occurs during periods of rapid social change or crisis, when old norms are disrupted, and new norms have not yet been established. This can lead to confusion, feelings of insecurity and increased behaviours such as crime and suicide. Anomie can be seen as a symptom of the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity in a society. When mechanical solidarity, based on similarity and conformity to a common set of norms and values, begins to break down, individuals can feel lost and disorientated. Organic solidarity, based on interdependence and role specialisation, is not yet fully established, leaving a normative vacuum. This is particularly true in modern societies, where social change is often rapid and disruptive. For example, the rise of industrialisation and capitalism in the 19th and 20th centuries created conditions of anomie as societies struggled to adapt their norms and values to these new economic systems. Anomie is, therefore, a key concept for understanding how societies manage change and transition and how they can fail to do so. It indicates the tension between the individual and society and the need to balance individual freedom and social cohesion.

The distinction between mechanical and organic solidarity is central to Émile Durkheim's work. These two forms of solidarity reflect different types of society, with distinct social structures, norms and values.

Mechanical solidarity generally characterises traditional or pre-modern societies, such as agricultural or tribal societies, where individuals have great similarities in values, beliefs and lifestyles. In these societies, social cohesion is maintained by sharing a collective consciousness - a common set of beliefs and moral values that each individual deeply internalises.

In contrast, organic solidarity is typical of modern or post-modern societies, which are characterised by great diversity and role specialisation. Social cohesion is based on individuals' economic and social interdependence in these societies. Individuals are linked to each other not by similarities but by differences - they depend on each other for specialised services and skills they cannot provide themselves.

So the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity represents the transition from a traditional to a modern society. It is a process that can be disruptive and conflictual, as it involves a radical change in social structure and how individuals perceive themselves and their relationships with others. However, according to Durkheim, this process is also necessary for the adaptation and survival of societies in a constantly changing world.

The place of the religious fact[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

For Émile Durkheim, religion plays a fundamental role in society. He studied religion as a social phenomenon in his book "Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse", published in 1912. For him, religion is a social fact in that a group of people practises it and exerts a constraint on the individual. Durkheim argued that religion was essential for providing social cohesion, solidarity and harmony in society by creating a common set of beliefs and practices. Religion contributes to the formation of the collective conscience, which is a unifying force within society. Durkheim also suggested that religion functions as a source of meaning and orientation for individuals, providing a structure for understanding the world and their place in it. On secularisation, Durkheim lived at a time when Western society was experiencing a decline in the influence of religion on public life, a process often referred to as secularisation. However, even though religion was losing its institutional influence, Durkheim recognised that human beings still needed rituals and beliefs to give meaning to their lives. Therefore, even in a secularised society, the sociological functions of religion (social cohesion, meaning, orientation) can be fulfilled by other forms of belief and practice, such as political ideologies, nationalism, humanitarianism, science, etc.

From Durkheim's perspective, religion plays a crucial role in shaping a society's moral values and maintaining social cohesion. For Durkheim, religion is a system of beliefs and practices that unite individuals into a single moral community, what he called a Church. Religion creates a shared set of norms and values that guide individual behaviour and help to regulate social life. These shared norms and values become part of the collective consciousness, a set of ideas and feelings common to all members of a society that act as a unifying force. Religion also provides a framework for rituals and ceremonies that reinforce a sense of community and belonging. These religious rituals bring people together, allowing them to express their beliefs and feelings collectively and to strengthen their solidarity and cohesion.

Durkheim emphasised the continuing importance of religion in society, even in apparently secularised contexts. He argued that although traditional religious institutions may be losing their importance or influence, fundamental aspects of the religious continue to structure our societies. In other words, although explicit forms of religion may decline in some societies, the principles and values that were once encapsulated in religious beliefs may continue to influence social culture, norms and behaviour. These principles and values may be incorporated into other social institutions, such as law, education, politics, or even into the norms and values of society in general. Moreover, Durkheim's concept of the 'sacred' is not limited to religion in the traditional sense. For Durkheim, the sacred refers to anything that is set apart, venerated or considered inviolable in a society. This can include symbols, ideas or values that are considered essential to a society's collective identity. So even without traditional religion, a society may have other forms of sacredness.

Concerning 'religious crime', Durkheim saw it as a violation of the sacred, a transgression of the norms and values considered essential to the moral order of a society. This can include crimes against religion and any action that violates the fundamental moral principles of a society. According to Durkheim, treating crime in a society - its detection, conviction and punishment - is an important means by which a society reaffirms its moral standards and strengthens social cohesion.

Religious crime" is crime against collective things (public authority, morals, traditions, religion). Religious crime is the primary form of crime in a developing society. For Durkheim, "religious crime" can be seen as an attack on the sacred a violation of the collective norms shared by society, whether these be public authority, morals, traditions or religion itself. In a traditional or developing society, norms and values are often firmly anchored in religion, and so any transgression of these norms is considered a religious crime. In other words, the crime is not just a breach of a secular law, but also a breach of a divine law or sacred moral norm. That said, it is important to note that even as society becomes more secularised, norms and values of religious origin can continue to exert an influence, even if they are now embedded in secular institutions such as law or education. Thus, even without explicit religious belief, actions that violate these norms and values may still be considered serious moral transgressions, or even 'crimes', in the broadest sense of the term.

The Theory of Socialization[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Émile Durkheim, as one of the founding fathers of sociology, made significant contributions to our understanding of socialisation. He distinguished two major processes of socialisation: social integration and social regulation.

Social integration is how individuals associate, connect and collaborate to form a society. It is the process by which individuals or groups are accepted into society and how they adapt to and adopt its values, norms and customs.

- Shared consciousness and beliefs: In a society, individuals often share common beliefs, values and perspectives that shape their collective consciousness. This collective consciousness serves as a binding force to unite individuals and help them work together towards common goals.

- Interactions with others: Social integration also involves participating in social interactions. This can occur in a variety of contexts, such as the family, school, workplace, etc. These interactions enable individuals to learn and adopt social norms and expected behaviours.

- Shared goals: Societies often have common goals and objectives that serve to unite their members. These goals may vary depending on the context, for example, political goals in a political society or economic goals in a commercial society.

Social integration, by fostering cohesion and harmony, plays a crucial role in maintaining social stability and promoting the well-being of all members of society. However, it is also important to note that social integration can sometimes inhibit individuality and personal freedom, as it requires conformity to group norms and values.

Social regulation is essential in maintaining order and stability in a society. It is the set of mechanisms by which society exercises a kind of control over its members, by establishing and enforcing standards of behaviour. Social regulation operates at several levels. It can be imposed by formal institutions, such as government laws and regulations, or it can be the result of informal social norms, such as the expectations and acceptable behaviour in a given culture. These social regulation mechanisms help guide individuals' behaviour in ways that promote cohesion and cooperation within society. They also help to prevent or manage conflict and maintain a degree of social equilibrium. In short, social integration and regulation are two key processes that help define a society's structure and functioning. They help to maintain order, foster cooperation and ensure the survival and well-being of the group as a whole.

Émile Durkheim has contributed to our understanding of society and social change. His theories on social solidarity, integration, regulation and the role of social institutions, among others, continue to influence contemporary sociology. In a modern society, according to Durkheim, solidarity is organic. This means that the members of society depend on each other because of the complexity and division of labour. Each individual has a specialised role to play, and all these roles are interdependent if society is to function properly. In addition, Durkheim emphasised the importance of common goals, principles of justice and shared symbolism for social cohesion. Common goals give meaning and purpose to life in society, principles of justice guarantee fairness and equality, and shared symbols facilitate communication and common identification. Finally, Durkheim also recognised that social change is an inevitable part of any society. He argued that social change is generally the result of changes in the division of labour and in dynamic density (i.e. the number of individuals and their degree of interaction). These changes can lead to new types of social solidarity, new norms and values, and new forms of social organisation.

In his 1897 book "Le Suicide", Émile Durkheim postulated that suicide is not simply an individual act of despair resulting from personal problems. Instead, he argued that suicide is a social phenomenon, influenced by social and cultural factors.

Durkheim identified four types of suicide, each the result of different levels of social integration and social regulation:

- Selfish suicide occurs when individuals are not sufficiently integrated into society. They may feel isolated or alienated, which can lead to suicide.

- Altruistic suicide occurs when individuals are too integrated into society, to the point where they sacrifice themselves for the group's good. This is more common in traditional societies where obligations to family or community are paramount.

- Anomic suicide occurs when social norms are weak or confused, leaving individuals without guidance or support. It can occur during periods of great social or economic change.

- Fatalistic suicide: This type is less developed by Durkheim, but it describes situations where the individual is over-regulated, where expectations of him are so high and oppressive that he feels driven to suicide.

In this way, Durkheim showed that suicide is not just a personal act but is also strongly influenced by social factors. This highlights the importance of social cohesion and social regulation in preventing suicide.

For Durkheim, suicide is a social phenomenon resulting from a lack or excess of socialisation. When there is a lack of socialisation, the individual can feel isolated, disconnected from society, leading to a feeling of anomie and ultimately to suicide. This is what Durkheim calls egoistic or anomic suicide. On the other hand, too much socialisation can also lead to suicide. In these cases, the individual may feel overwhelmed by social norms and expectations to the point of sacrificing himself for the good of the community. This is what Durkheim calls altruistic suicide. According to Durkheim, modern society has difficulty maintaining a balance between social integration (the individual feeling part of society) and social regulation (the individual respecting the norms and rules of society). The balance between these two factors is crucial to preventing suicide and ensuring social cohesion. In short, Durkheim's analysis of suicide highlights the importance of socialisation and social balance in preventing self-destructive behaviour and maintaining social cohesion.

Pierre Bourdieu: a political theory of the social world[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Pierre Bourdieu : 1930 - 2002[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Pierre Bourdieu, an influential French sociologist, served in Algeria during the war of independence. This experience had a significant influence on his work and ideas. Bourdieu was particularly struck by the differences between France's official discourse on the situation in Algeria and the reality he observed on the ground. He found that the French political and media discourse on the war and colonisation did not correspond to the experience of Algerians. This led him to develop his concept of the 'field', which is a social space structured by positions (or posts) whose properties depend on their position in that space, and which can be analysed independently of the characteristics of their occupant (individual or collective). Fields are places of power struggle, where actors use different forms of capital (economic, social, cultural) to gain position. This experience also influenced his theory of symbolic violence, in which he argues that power is often exercised in society not by physical force, but by more subtle means, such as the manipulation of discourse, ideas and symbols. For Bourdieu, the role of the sociologist is to reveal these often hidden power structures and to uncover the reality behind the dominant discourse. He argues that sociologists must always be aware of the gap between discourse and reality and work to bridge it.

Pierre Bourdieu is known for his in-depth research into power structures and social hierarchies. He is convinced that society is structured into different 'fields' - areas of activity such as art, education, religion, etc. - where individuals struggle for power. - where individuals struggle for power and prestige. His early work on Algerian society and Kabyle culture laid the foundations for his theory of power and domination. He observed how traditional social structures and cultural practices helped to maintain existing social hierarchies and reproduce inequalities. Bourdieu also developed the concept of 'cultural capital', which refers to a person's knowledge, skills, education and other cultural assets. He argued that cultural capital plays a crucial role in determining an individual's social position and contributes to the reproduction of social inequalities. In his later work, Bourdieu applied these ideas to studying other societies, including France. He criticised neo-liberalism and supported an anti-globalisation position, arguing that global power structures contribute to the reproduction of inequalities on a global scale. In this way, Bourdieu left an indelible mark on sociology and the social sciences, proposing powerful conceptual tools for analysing power structures and social hierarchies.

Pierre Bourdieu wrote several influential works that helped shape modern sociology:

- "Le Déracinement" (1964): In this work, Bourdieu examines the consequences of uprooting the rural Algerian population during the War of Independence. He shows how this uprooting destroyed existing social structures and led to a social and cultural crisis.

- La Distinction" (1979): This is perhaps Bourdieu's most famous work. In it, he analyses how individuals use taste and cultural consumption to assert their social status and distinguish themselves from other social classes. Bourdieu argues that taste preferences are not simply individual choices but are strongly influenced by social background and cultural capital.

- Le Sens Pratique" (1980): In this work, Bourdieu develops the concept of habitus, which he defines as a set of durable and transferable dispositions that structure the perceptions, judgements and actions of individuals.

- La Misère du Monde" (1993): a large-scale study of social suffering in France at the end of the 20th century, based on a series of interviews with individuals from various social backgrounds.

- La Domination Masculine (1998): In this work, Bourdieu analyses how male domination is reproduced in society. He argues that this domination is rooted in habitus, social structures and cultural practices.

Pierre Bourdieu has spent much of his career criticising structures of power and inequality in society and developing a sociological theory that incorporates elements of philosophy and politics. He held the chair of sociology at the Collège de France from 1981 until his retirement in 2002. This prestigious position reinforced his influence as one of the leading social thinkers of the 20th century. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Bourdieu became increasingly critical of globalisation and neoliberalism, which he saw as forces that exacerbated social and economic inequalities. He aligned himself with the anti-globalisation movement, seeking alternatives to neoliberal globalisation, and participated in demonstrations and awareness-raising campaigns. Bourdieu emphasised the role of sociology as a force for social critique and urged sociologists to become actively involved in the fight against social injustice. His work continues to influence many fields, including sociology, anthropology, education and cultural studies.

The concept of habitus[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Habitus, a central concept in Pierre Bourdieu's work, is a set of durable and transferable dispositions that individuals acquire throughout their lives through their social experiences. These dispositions shape individuals' perceptions, judgments and actions in a way that is both structuring (by past and present social conditions) and structuring (by orienting future action and experience). Habitus encompasses the attitudes, beliefs, values and behaviours that are typical of a particular social group. It is the product of incorporating the social structure into the individual's body, who then can navigate the social world and understand its implicit rules. However, the habitus is not a fixed and determining straitjacket. Individuals can act and think creatively according to situations, but their actions and thoughts are structured by their acquired habitus. Behaviour and attitudes can therefore vary depending on the situation but remain largely guided by habitus. Bourdieu argued that habitus is both the product of history and how history is reproduced and reinvented in everyday practices. It is, therefore, a dynamic concept that links social structures and individual agency.

Pierre Bourdieu distinguishes two forms of habitus: primary and secondary.

The primary habitus is acquired during the first years of life within the family and the social environment of origin. It is, therefore, strongly influenced by social class, parents' level of education, gender and so on. During this phase, we learn and internalise the rules and norms implicit in our social environment, which then become second nature. The primary habitus is considered to be the most durable and deeply rooted.

The secondary habitus is acquired later, usually during schooling, vocational training, or other experiences involving socialisation (such as entering a new profession, joining an organisation, etc.). Depending on the circumstances, this habitus may complement, modify, or even contradict the primary habitus. For example, an individual may develop a school habitus that differs from his or her family habitus, depending on the influence of his or her teachers, classmates and so on.

It is important to note that habitus is not static but dynamic and adaptable. Individuals can change their habitus throughout their lives in response to new experiences and new social contexts. However, the primary habitus, being the most deeply rooted, tends to have a lasting influence on people's perception of the world and their behaviour.

In Pierre Bourdieu's theory, habitus is a kind of "internal programme" that unconsciously guides our thoughts, perceptions and actions. Our past experiences and socialisation influence this internal structure and are constantly reshaped and adapted to new situations. However, although the habitus can be compared to a computer programme in that it guides our behaviour, it is important to note that, unlike a computer programme, the habitus is not rigid or invariable. There can be 'missteps' or inconsistencies in our behaviour, as the habitus is influenced by many different factors, including individual and contextual factors. Furthermore, whereas computer programs are designed to be precise and predictable, habitus is inherently flexible and adaptable. Furthermore, habitus is not only a mechanism of social reproduction but also a mechanism of change and innovation. It enables individuals to adapt to new situations and develop new practices and ways of thinking. In this sense, habitus is a fundamental concept for understanding the dynamics of social life and how individuals navigate the social world. Primary socialisation is the process by which individuals learn and integrate the norms and values of their society from an early age. This happens mainly through the family and school. In this way, individuals acquire their first understanding of the world, which forms their primary habitus. Secondary socialisation, on the other hand, refers to the learning process that occurs later in life, when individuals enter new social environments or adopt new roles. This can include contexts such as the workplace, university, or even peer groups. This secondary socialisation overlaps and interacts with the existing primary habitus, adding a new layer of complexity to how individuals perceive and interact with the world. It is also important to note that socialisation is an ongoing process that takes place throughout life. Individuals constantly learn and adapt to new situations and environments, which constantly shapes their habitus and understanding of the world.

Habitus is not a static structure but constantly shifts and evolves in response to new experiences, knowledge and influences. Moreover, because habitus is shaped by socialisation, there can be marked generational differences due to variations in social and cultural influences over time. Younger generations may incorporate new elements into their habitus that are not present or less pronounced in older generations' habitus. These differences can sometimes lead to conflict or misunderstanding between the generations. For example, parents' values may conflict with their children's more progressive attitudes, leading to tensions. This phenomenon is often observed in sociology, where interpersonal and intergenerational interactions reflect large-scale social and cultural changes. This can manifest itself in different ways, such as differences of opinion on political or social issues, differences in lifestyles and behaviour, or even differences in the use of technology and the media.

Pierre Bourdieu described movements in habitus in terms of "Downgraded" and "upwardly mobile". These terms refer to individuals who have changed social class and must adapt their habitus to their new situation.

- "Downgraded" refers to those who have experienced downward social mobility. They may have difficulty adapting to their new social situation because of the dissonance between their habitus (formed in a higher social class) and their current social position. They may continue to maintain behaviours, tastes and attitudes associated with their former social class, which can lead to tensions or difficulties in adapting.

- Conversely, the "upwardly mobile" have experienced upward social mobility. They may also face challenges in adapting to their new social position. Their habitus, formed in a lower social class, may not correspond to their new social position. They may feel uncomfortable or illegitimate in their new social class.

Habitus also reflects class experiences, as it is formed by socialisation and experiences within a particular social class. This can include class behaviours, tastes, attitudes, preferences, etc. Social institutions can reproduce and reinforce these class habits, thus contributing to the social reproduction of class inequalities.

Pierre Bourdieu developed the idea that class habitus are in conflict with each other, which produces and reproduces social inequalities. According to Bourdieu, each class has its own habitus, i.e. a set of socially inculcated dispositions, preferences and behaviours that seem "natural" or "obvious" to the members of that class. Habitus is thus both the product of an individual's social position and the mechanism by which that position is perpetuated. Class habitus can be a source of conflict because it determines not only people's behaviour and attitudes but also their aspirations and expectations. For example, those with much cultural capital (such as higher education) may value and aspire to different things from those with less. This can lead to misunderstandings, tensions and conflicts between different classes. Furthermore, Bourdieu suggests that individuals and groups are constantly engaged in symbolic struggles to define what is valued and respected in society. These struggles can contribute to the reproduction of social inequalities by reinforcing the legitimacy of some forms of capital over others. For example, in a society where cultural capital is highly valued, those with higher education may be able to legitimise their privileged position and devalue the skills and contributions of those with less education.

Social field and conflictuality: between reproduction and distinction[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

« The social world can thus be represented in the form of a (multi-dimensional) space constructed based on principles of differentiation or distribution constituted by the set of properties operating in the social universe under consideration. Agents and groups of agents are thus defined by their relative positions in this space. »[1]

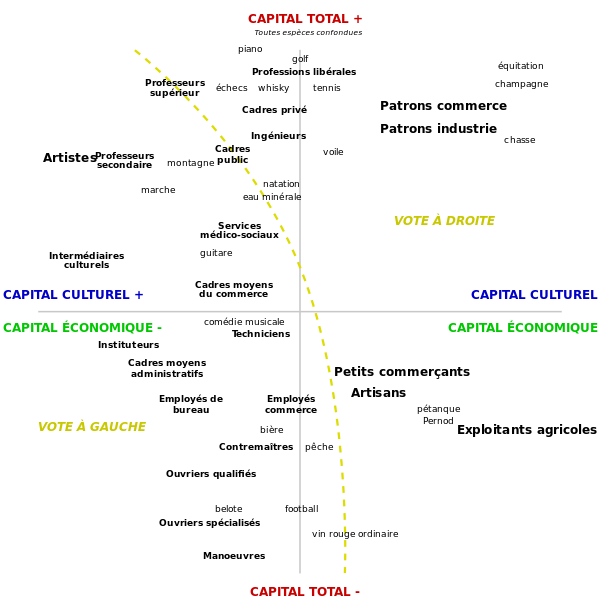

This quote from Pierre Bourdieu is an excellent representation of his vision of society as a social space structured around different types of capital - economic, cultural and social. Within this space, individuals and groups position themselves according to their different resources or properties, defining their social place. In other words, Bourdieu's social space is a set of structured positions within a given field, where the amount and type of capital determine each position that individuals or groups possess. These positions are relative, meaning that other positions in the field define them. For example, in the field of education, a person with a doctorate occupies a higher position than someone with only a bachelor's degree because of the greater amount of cultural capital (i.e. education) that the person with a doctorate possesses. From this perspective, social struggles are seen as struggles to change one's position in this social space through acquiring or converting different types of capital. Social inequalities are thus seen as the product of the unequal distribution of these different forms of capital.

For Pierre Bourdieu, social space is a dynamic and complex system structured by distributing different types of 'capital' possessed by individuals or groups. This capital can be economic (wealth, possessions), cultural (education, skills, knowledge) or social (relationships, networks). The position of an individual or group in this social space is determined by the quantity and type of capital they possess. The different positions in the social space are relative to each other, which means that the position of an individual or group is defined in relation to the positions of others. It is important to note that this social space is constantly changing. Individuals and groups can change their position by acquiring or losing capital. Similarly, capital distribution principles can change over time in response to social, economic and cultural changes. This is what Bourdieu means by 'conjunctures' - the specific conditions of a given period that influence the structure of social space.

Pierre Bourdieu formulated the "theory of capitals" to explain how individuals and social groups position themselves and interact in social space. According to Bourdieu, each individual or social group has a certain amount of different types of capital, which are used to maintain or improve their position in society. These include economic, cultural, social and symbolic capital. Each type of capital plays a crucial role in determining the position of an individual or group in society.

- Human capital refers to the sum of an individual's skills, knowledge and experience. It is often associated with education and training but includes non-formal skills and experience acquired through work or other activities.

- Economic capital is financial and physical capital, including everything that can be measured in monetary terms.

- Cultural capital refers to knowledge of the dominant culture's norms, values and skills. It includes knowledge of the arts, literature, manners and norms of behaviour and discourse acceptable in a given society.

- Social capital refers to the networks and connections an individual may have. These are relationships of trust, and membership of groups or networks, which can be used to obtain resources and advantages.

- Symbolic capital is a form of social recognition, honour or prestige. It is often linked to the possession of other types of capital, as the possession of economic, cultural or social capital can often lead to greater recognition and prestige in society.

These different types of capital are not mutually exclusive and they often interact with each other. These different forms of capital interact and can often be converted into each other. For example, people can use their economic capital (wealth) to acquire cultural capital (education). Similarly, someone with a lot of social capital (connections) may be able to acquire economic capital (by finding a well-paid job through their connections, for example).

Bourdieu's theory of capital explains how individuals and groups position themselves in society according to two main criteria: hierarchisation and distinction.

- Hierarchisation: The total volume of capital an individual or group holds largely determines their position in the social order. The more capital a person or group possesses (whether economic, cultural, social or symbolic), the higher their position in the social hierarchy.

- Distinction: The structure of capital, i.e. the relative distribution of different types of capital, also plays an important role. For example, some individuals or groups may have a lot of economic capital but little cultural capital, while others may have a lot of cultural capital but little economic capital. These differences in capital structure can lead to differences in lifestyles, tastes, preferences and behaviours, creating distinctions between different social groups.

This is why Bourdieu sees society as a space of different social positions that are constantly at stake and in competition. Each individual or social group uses its capital to maintain or improve its position in the social space.

The Review of Bourdieusian Thought[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

For Bourdieu, society is a space of struggle, competition and conflict. These conflicts do not necessarily involve physical or open violence, but rather competition for resources, power, prestige, recognition, etc. Social agents seek to maintain or improve their position in the social field by using the different types of capital at their disposal. For example, they can use their economic capital to acquire cultural capital (for example, by paying for a quality private education for their children), or use their social capital to obtain economic capital (for example, by using their connections to obtain a well-paid job). In addition, capital can be used to exclude other people or groups from certain social positions or benefits. For example, people with a high level of cultural capital can use this resource to devalue the tastes and preferences of those with less cultural capital, thereby creating social distinctions. Finally, it is important to note that the different types of capital are not always perfectly aligned or compatible. For example, a person may have a lot of economic capital but little cultural capital, or vice versa. This can lead to tensions or contradictions within the social structure.

Pierre Bourdieu has developed a sociological theory that seeks to overcome the classic dichotomy between Marxism and the functionalist or structuralist approach. Instead, he proposes a more nuanced view of social stratification that considers several types of capital, not just economic capital. In Bourdieu's theory, economic capital is certainly important, but it is not the only factor determining an individual's social position. Cultural capital and social capital also play a major role. Cultural capital, for example, can take the form of language skills, university degrees or knowledge of certain forms of art or music. On the other hand, social capital can take the form of personal relationships, networks of acquaintances, and so on. Hierarchisation is a process whereby certain social groups are ranked above others according to the amount of capital they possess. Distinction, however, concerns how capital is distributed or structured. For example, a person may have much economic capital but little cultural capital, and vice versa. The social world is a field of antagonisms and processes of differentiation; it is also a market in which people can play. Everyone uses their opportunities to increase their capital or prevent others from acquiring it. The challenge is to accumulate. Social agents are always seeking to maintain or increase the volume of their capital and thus to maintain or improve their social position. On the other hand, mechanisms for preserving the social order predominate because of the importance of reproduction strategies.

Pierre Bourdieu's analysis can be considered post-Marxist because it seeks to go beyond certain limitations of traditional Marxism while focusing on questions of power and class struggle. Traditional Marxism focuses primarily on economic capital (i.e. financial and material resources) as the main determinant of social position and power. According to this perspective, an individual's social class is determined by his position in the relations of production (for example, whether he is a wage earner, a capital owner, etc.). Bourdieu, however, recognises that power and domination are not solely based on economic capital. He introduces the concepts of cultural capital and social capital as forms of power that are also important in determining an individual's social position. Cultural capital includes things like education, language skills, and familiarity with dominant forms of culture. Social capital, on the other hand, includes things like personal relationships, networks of acquaintances, and membership of certain social groups. So while Bourdieu draws on Marxism in his focus on structures of power and domination, his approach is more complex and multi-dimensional. He recognises that an individual's social position is determined not only by their position in the economy but also by their possession of cultural and social capital. This is why Bourdieu can be said to be developing a post-Marxist analysis.

Each class is characterised by the quantity and type of capital it possesses.

- The dominant class possesses abundant economic and cultural capital. Members of this class are often highly educated and occupy positions of power in society. However, there may be tensions within this class depending on the nature of the capital that predominates (economic or cultural).

- The petty bourgeoisie is defined by its intermediate position in the social structure. Members of this class generally have a certain level of education and stable employment, but they do not have the same level of wealth or power as the dominant class. They may aspire to social ascension, and this aspiration can sometimes create tensions and contradictions.

- The working classes, conversely, are characterised by a lack of economic and cultural capital. Members of these classes may have difficulty accessing education and economic opportunities and are often marginalised or excluded from positions of power in society.

It is important to note that, according to Bourdieu, an individual's class position is not simply a question of income or wealth, but also depends on factors such as education, social status and networks of relations.

The position of social agents in a given field, be it politics, education, art, etc., is influenced by their position in the wider social space. This position is determined by the amount and type of capital they possess. In this context, Bourdieu has shown that social agents implement strategies to maintain or increase their capital. For example, they may seek to acquire more economic capital through education or investment or increase their cultural capital by cultivating and familiarising themselves with the arts and sciences. The notion of social reproduction is also central to Bourdieu's work. He argues that social classes reproduce from generation to generation, largely through capital transmission. For example, the children of the dominant class often have access to high-quality education and an influential social network, enabling them to acquire significant economic and cultural capital and maintain their family's position in the social hierarchy. By contrast, children from the working classes often have less access to these resources, making their social mobility more difficult. This is why Bourdieu has been a biting critic of social systems that encourage this social reproduction and perpetuate class inequalities.

Pierre Bourdieu described several investment strategies individuals and families can use to maintain or increase their capital. Here is a brief description of each:

- Biological investment strategies: These are efforts to improve and preserve physical health and vitality. This could include such things as attention to diet, exercise, medical care, etc. These strategies can improve an individual's "body capital".

- Inheritance strategies (marriage): Bourdieu points out that marriage has often been used to exchange or acquire capital, whether economic, cultural or social. Marriages can be used to create or strengthen social ties, acquire economic capital or increase prestige and social recognition.

- Educational strategies involve investing in education to acquire cultural capital. This may include choices such as the type of school to attend, the subjects to study, etc.

- Economic strategies: These strategies relate directly to acquiring and preserving economic capital. They may include decisions about savings, investment, employment, etc.

- Symbolic strategies: These are efforts to acquire and maintain symbolic capital linked to recognition, prestige and honour. This could include such things as membership in certain organisations, participation in prestigious activities, etc.

The effectiveness of reproductive strategies depends very much on the resources available to agents, which can vary according to the structural evolution of society. For example, access to quality education, a well-paid job, affordable quality healthcare, etc., can majorly impact an individual's ability to maintain or improve his or her social position. In addition, there is often tension in society between the forces of conservation, which seek to maintain the existing social order, and the forces of change, which seek to transform it. This tension can be a source of conflict but can also stimulate progress and social evolution. It is also important to note that while reproductive strategies can effectively maintain the existing social order, they can also perpetuate social inequalities. This is why Bourdieu and other sociologists have stressed the need for social critique and structural change to address the root causes of these inequalities.

The political power[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Political power is characterised by the concept of "dispossession". The notion of "dispossession" in Bourdieu's analysis of political power is linked to his concept of the field. A field is a social space of competition in which individuals or institutions struggle to control the specific resources, or 'capital', valued in that particular field.

In the political field, dispossession can refer to several phenomena:

- The exclusion of certain individuals or groups from political power: This is the most obvious sense of dispossession. For example, people who do not have the right to vote or who are marginalised in the political system are "dispossessed" of their ability to participate fully in political life.

- Loss of control over politics by those who are supposed to be in charge: Politicians themselves may feel "dispossessed" if they feel that they do not really have control over policy decisions, either because they are constrained by external forces (such as lobbies or public opinion) or because they are caught up in power dynamics within their own party or organisation.

- The separation between citizens and politics: In a broader perspective, Bourdieu also spoke of dispossession in terms of the growing distance between ordinary citizens and the world of politics, which can manifest in alienation or cynicism towards politics.

These forms of dispossession are not mutually exclusive and can often reinforce each other.

« The field of political production is the place inaccessible to the layperson, where forms of politically active and legitimate perception and expression are produced in competition between professionals engaged in it, which are offered to ordinary citizens, reduced to the status of consumers. »

This quote from Bourdieu illustrates his concept of the 'field' and how it applies to politics. In his view, the political field is a specific social space occupied by political 'professionals' - i.e. politicians, strategists, advisers, lobbyists, etc. These actors compete to control political resources and define how political issues are perceived and discussed. At the same time, Bourdieu points out that the political field is "inaccessible to the layman". By this, he means that ordinary citizens are often kept out of the political process, reduced to the role of spectators or consumers of politics rather than active players. They are invited to accept the terms of political debate as defined by political professionals rather than to participate in defining them. This is where the notion of 'dispossession' comes in. Ordinary citizens can feel 'dispossessed' of their ability to influence the political process, either because they are excluded from decision-making or because they feel unable to understand or navigate the complex world of politics.

Bourdieu argued that the political field, like all social fields, is structured around specific forms of capital. In the case of politics, this might include social capital (relationships, networks), cultural capital (knowledge, skills, education), and sometimes economic capital. This means that to enter and succeed in the political field, you need to accumulate and use these forms of capital to navigate the field. This requires a certain type of habitus - a set of dispositions, behaviours and ways of thinking acquired through social experience - which is both produced by and adapted to the political field. In this context, the political habitus would be characterised by skills such as the ability to speak in public, to debate, to negotiate, to understand complex issues, to mobilise support, and so on. Those who possess this habitus are, therefore, better equipped to succeed in politics. Bourdieu also argued that the political arena also functions as a market, where politicians seek to 'sell' their ideas and programmes to voters. In this market, voters are often treated as consumers, and politicians seek to win their loyalty by offering them political products that meet their needs and preferences. However, this view of politics can also lead to the exclusion and marginalisation of those who do not have access to the forms of capital needed to participate fully in politics, including the poorest and most marginalised. This can lead to a concentration of political power in the hands of an elite and a sense of powerlessness and dispossession among ordinary citizens.

There are two distinguishing features: there is a societal divorce, and politics becomes a "game", resulting in a de facto solidarity between political insiders.

Pierre Bourdieu identifies these two types of political capital as essential to success in the political arena.

- Personal capital of notoriety: this is the recognition and visibility that an individual receives in the political arena. This can be the product of personal history, achievements, reputation, media presence, etc. It is important to note that notoriety can be positive or negative and can vary according to the context and public perceptions.

- Delegated political authority capital: this is the power and authority conferred on an individual by other players in the political arena. This can take the form of a political mandate, where an individual is elected or appointed to a position of power. Still, it can also be the product of relationships, alliances, support, etc. It is a form of capital that can be leveraged. It is a form of capital that is often at stake in struggles for power within the political field.

It should be noted that these two forms of capital are interdependent and can reinforce each other. For example, a high profile may help an individual to obtain a political mandate, while a political mandate may in turn, increase the individual's profile. However, they can also sometimes be in tension or conflict, as when an individual's personal reputation is at odds with their political role or mandate.