Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science

Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory ● The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic ● Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory ● The notion of "concept" in social sciences ● History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts ● Marxism and Structuralism ● Functionalism and Systemism ● Interactionism and Constructivism ● The theories of political anthropology ● The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas ● Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science ● An analytical approach to institutions in political science ● The study of ideas and ideologies in political science ● Theories of war in political science ● The War: Concepts and Evolutions ● The reason of State ● State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance ● Theories of violence in political science ● Welfare State and Biopower ● Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes ● Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences ● The system of government in democracies ● Morphology of contestations ● Action in Political Theory ● Introduction to Swiss politics ● Introduction to political behaviour ● Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy ● Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation ● Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation ● Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations ● Introduction to Political Theory

Formulating a research question in terms of interest means approaching the subject from the perspective of rational choice theory. According to this approach, actors are supposed to act rationally to maximise their utility or benefits and minimise their costs or losses.

To formulate a research question in terms of interest, the following steps can be followed:

- Identification of relevant stakeholders: Who are the main actors involved in the situation being studied? This may include individuals, groups, organisations, institutions, nations, etc.

- Understanding the interests of these actors: What are the objectives or desires of these actors? What are they trying to achieve or avoid?

- Analysis of stakeholders' actions and strategies: How do stakeholders try to achieve their interests? What strategies do they use to maximise their benefits and minimise their costs?

- Exploring the dynamics of collective action: How do stakeholders interact with each other? What are the consequences of their collective actions?

- Consideration of expectations and perceptions: How do stakeholders' expectations and perceptions influence their actions? How do they anticipate the actions of others and how does this affect their own strategies?

Framing a research question in this way allows us to explore in depth the motivations of stakeholders, the strategies they use and the consequences of their actions. It also makes it possible to explain complex phenomena and make predictions about the future behaviour of players.

This approach, based on identifying the interests, preferences and strategies of stakeholders, is one of the most established methodologies for analysing public action. It has highlighted a number of key elements, such as :

- The rationality of decision-making: Most players act rationally, i.e. they seek to maximise their profits while minimising their costs. This approach has made it possible to study how and why stakeholders make certain decisions.

- The logic of collective action: Actors do not operate in isolation, but often act in groups to achieve their objectives. Studying collective action can reveal how individual and collective interests intersect and interact.

- Modes of influence and interaction: Actors seek to influence and interact with other actors to promote their interests. This approach has enabled us to understand how power is exercised and negotiated in a particular sector of public action.

The main aim of this article is to help develop a deeper understanding of the theory of rational action in the political domain. This involves explaining the concept of rationality and how it manifests itself in the behaviour of political actors. We will also seek to demonstrate how actors' preferences and strategies are established and how these contribute to shaping political outcomes. An important part of the paper will provide analytical tools for studying and predicting political behaviour based on actors' interests. We will illustrate how rational action theory can be put into practice to analyse concrete cases, such as the development of social policies. Finally, we will take time to discuss the strengths and limitations of the rational action approach to politics. We will place particular emphasis on the importance of considering the diversity of actors and the variety of their preferences and strategies. The ultimate aim of the course is to provide students with a solid theoretical and practical basis for understanding, analysing and interpreting political dynamics through the prism of rational action theory.

Interest-based approach[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The interest-based approach suggests that political actors are motivated by their material interests, often defined in economic terms. For example, a person who owns a production company might be politically motivated to support free trade policies, whereas a worker in a protected industry might be more inclined to support protectionist policies.

According to a materialist approach to politics, the material or economic position of political actors (whether individuals, social groups or states) can largely determine their objective interests and, consequently, influence their political preferences. An individual's political interests may be strongly influenced by his or her economic situation. For example, someone who owns a business may favour policies of lower taxes and minimal regulation, while a salaried worker may prefer policies to protect workers' rights. For social groups, material position can also influence political interests. Economically disadvantaged groups may be in favour of policies to redistribute wealth, while wealthier groups may be opposed to such policies. As far as states are concerned, material position, usually measured in terms of national wealth or GDP, can also influence political interests and preferences. Wealthy states may favour free trade policies that allow them to export their products, while less developed states may prefer protectionist policies that protect their infant industries. While material position influences political interests, it is not the only factor at play. Cultural values, ideological beliefs and many other factors can also influence political preferences.

An actor's material position can also determine its political power. Material resources, whether wealth, property, control of key infrastructure or other economic assets, can be used to exert political influence and shape choices and interactions within a society or political system. For example, an individual or group with considerable economic resources may finance political campaigns, hire lobbyists to influence legislators or create media outlets to control public discourse. Similarly, a state with significant economic resources can use its economic power to influence other states through economic diplomacy, development aid, trade and other economic levers. Material position can also influence political power in a more indirect way. For example, the possession of economic resources can confer high social status, which in turn can increase political power by increasing an actor's influence and credibility. However, just as material position is not the only factor that determines political interests, neither is it the only factor that determines political power. Other factors, such as personal competence, charisma, moral authority, access to information and other non-material resources, can also play an important role in determining political power.

While this approach can explain much political behaviour, it is not exhaustive. Political actors are also motivated by ideals, convictions and other non-material factors. Moreover, political power depends not only on the possession of resources, but also on the ability to use these resources effectively. For example, a political actor may have a lot of money but lack the skill or intelligence to use it effectively to influence policy.

Understanding the actor in politics, whether an individual, a group or a state, requires a multi-layered analysis. Actors have motivations, resources and interests that depend on their position in the social, economic and political structure, both nationally and internationally. The state, in particular, is a central player in international politics. Its position in the international structure can greatly influence its interests and political preferences. A state that is economically powerful, for example, may have an interest in maintaining an open trading system, while a less developed state may prefer protectionist policies. The resources available to a state, whether financial, organisational or institutional, can also play an important role in determining its political power and interests. A wealthy state may have the means to fund a powerful army, support allies or pursue ambitious policies. Similarly, a state with solid institutions may be better able to implement its policies effectively, attract foreign investment or maintain order and stability.

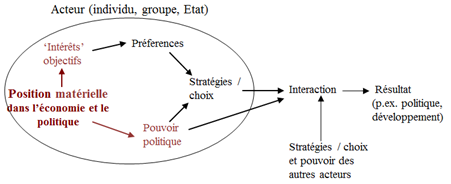

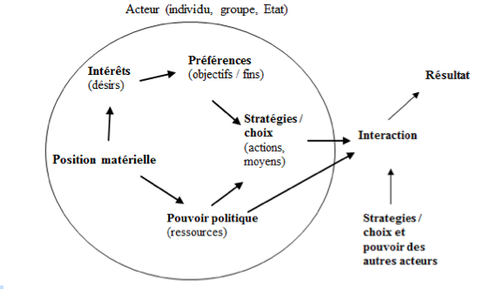

In a way, this diagram is a way of understanding the interests and resources of the players. What it describes is part of what is generally known as rational choice theory, which is widely used in economics, political science and other social science disciplines. This theory is based on the principle that actors (be they individuals, groups, states, etc.) are rational and seek to maximise their utility according to their interests. According to this perspective, political actors define their objectives according to their interests, which are largely determined by their material position and resources. They then develop strategies and take decisions to achieve these objectives, taking into account the constraints and opportunities available to them. These players are not isolated, but constantly interact with other players, each with their own interests, resources and strategies. These interactions largely determine the final political outcome. For example, the outcome of an election is determined by the preferences and votes of all the voters, each of whom makes a rational choice based on his or her own interests.

Individual analysis[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

When it comes to understanding the political behaviour of individuals, their economic and social positioning in society is a key factor.

An individual's economic position refers to their economic situation, including their level of income, wealth, employment and economic security. These factors can influence an individual's political preferences in a number of ways. For example, an individual with a high income may be in favour of tax reduction policies, while an individual with a precarious job may be in favour of worker protection policies.

An individual's social positioning, on the other hand, refers to their place in the social hierarchy, which can be influenced by factors such as education, race, gender, age and other aspects of social identity. These factors can also influence political preferences. For example, individuals from marginalised social groups may be more likely to support anti-discrimination policies.

An individual's economic and social position can have a significant influence on their political behaviour. Political theorists and sociologists have long noted these correlations.

The concept of "objective interest" is often used to explain this phenomenon. According to this perspective, an individual's economic and social position determines his or her objective interests, i.e. what would rationally be in his or her interest based on that position. For example, it is in the objective interest of a working poor person to support wealth redistribution policies, while it is in the objective interest of a wealthy business owner to oppose such policies.

Explaining people's electoral behaviour in terms of social cleavages, also known as 'class voting', is another way of understanding how economic and social position influences political behaviour. According to this perspective, individuals are more likely to vote for candidates or parties that represent their social class. For example, working-class individuals may be more inclined to vote for left-wing parties, while upper-class individuals may be more inclined to vote for right-wing parties.

Group analysis[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

At group level, material interests are also an important driver of political action. Interest or producer groups, which may represent different industries, professions, social groups or other stakeholder groups with common interests, often seek to influence policies to their advantage.

These groups may use a variety of strategies to achieve their objectives, including lobbying, which is an activity whereby a group attempts to influence policy-makers directly. This may involve activities such as meeting with legislators, providing information or research on specific policy issues, or mobilising their members to put pressure on politicians.

An example of this might be how industry groups or companies can lobby for policies favourable to their industries, such as subsidies, tax breaks, or regulations that restrict competition. On the other hand, groups such as trade unions can lobby for policies that protect workers' rights, such as minimum wages or workplace safety laws.

In political and sociological analysis, as well as focusing on individuals and small groups, consideration is also often given to wider social units. These units can be defined in various ways, for example in terms of relations to the means of production (as in the Marxist framework of the working class versus the bourgeoisie), or in terms of sectoral positioning in the economy. Relations to the means of production refer to the way in which groups are linked to the economy. For example, those who own the means of production (such as factories, businesses, etc.) are often considered to be part of the capitalist or bourgeois class, while those who sell their labour power are considered to be part of the working class. Sectoral positioning, on the other hand, refers to a group's place in the wider economy. For example, workers in the manufacturing sector may have different interests from those in the service sector, and workers in agriculture may have different interests from those in technology.

These larger social units may have common political interests because of their shared economic position. For example, manufacturing workers may all be interested in trade protection policies, while business owners may be interested in tax reduction policies. This is why we often see these groups mobilising collectively to lobby politicians or influence public policy.

In comparative politics, researchers often examine how and why the political trajectories of different countries diverge or converge. These trajectories can be analysed in terms of public policy, i.e. the decisions taken by governments and the results of these decisions. Interests, whether individual, group or institutional, play a key role in the formulation of public policy. For example, in economics, a country's tax policy may be influenced by the interests of various groups, including businesses, workers, landowners, and so on. Similarly, a country's foreign policy can be influenced by the interests of domestic political actors as well as the country's relations with other states. These interests can help to explain national trajectories in terms of public policy. For example, countries with a strong trade union influence may have stronger worker protection policies, while countries with a strong business influence may have stronger free market policies. Similarly, a country whose foreign policy is strongly influenced by relations with a particular neighbour may have a very different foreign policy trajectory to a country without such relations.

Pluralist theory is an approach in political science which postulates that political power is distributed among a diversity of interest groups and not concentrated in the hands of a single elite or social class. From this perspective, public policy is the product of interactions, negotiations and compromises between these different interest groups. These interest groups, also known as pressure groups or producer groups, can represent a wide range of actors, for example businesses, trade unions, environmental groups, consumer groups and others. Each group seeks to promote its own interests by influencing policy-makers. Coalitions between groups also play a key role in this approach. A single interest group may not have sufficient power to influence public policy. However, by forming a coalition with other groups with similar or complementary interests, they can increase their influence. For example, several environmental groups may join forces to promote an environmental protection policy. Or businesses from different sectors may form a coalition to support a policy of tax reduction. Pluralist theory considers that this competition and collaboration between interest groups contributes to a balance of power and a broader representation of society's interests in public policy. However, it is also subject to criticism, with some arguing that certain groups (e.g. big business) have more resources and therefore more power to influence policy, which can lead to an imbalance of power and unequal representation of interests in public policy.

Identifying the main players is an essential step in political analysis. Key players may be individuals, interest groups, political parties, government institutions, or even countries in the context of international relations. Each actor has a particular role depending on its position, resources, interests and degree of involvement in a certain context. For example, in the context of public policy, the actors may be policy-makers (such as legislators or senior civil servants), interest groups that seek to influence policy, and the public who are affected by policy. Identifying the roles of each actor requires an understanding of the relationships between them. These relationships may be competitive (for example, two political parties competing for power) or cooperative (for example, two interest groups forming a coalition to promote a common policy). They can also be based on power relationships, with some actors having more resources or influence than others. Once the key players and their roles have been identified, it is possible to analyse how their actions and interactions contribute to the formulation of public policy. This analysis can help to understand why some policies are adopted and others are not, and how the interests of different stakeholders are represented in the policy process.

The theory of hegemonic stability[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The theory of hegemonic stability is a theory in international relations which suggests that stability in the international economic system is favoured by the presence of a single dominant, or hegemonic, nation. This nation uses its considerable power to establish and maintain the rules and standards of the economic system, thereby promoting stability and cooperation. According to this theory, the hegemonic power has both the ability and the interest to maintain an open and liberal economic system. Its ability derives from its economic and military dominance, which gives it the power to shape economic rules in its favour. Its interest in maintaining an open system derives from its dominant position in the world economy, which allows it to benefit disproportionately from free trade.

In the context of the theory of hegemonic stability, hegemony refers not only to raw power, but also to the ability to direct and coordinate the global economy. The hegemon is often responsible for the provision of global public goods, such as monetary stability and maritime security, which benefit all nations but would otherwise be insufficiently provided. The theory of hegemonic stability has been used to explain various periods of international economic stability and cooperation, such as British rule in the 19th century and American rule after the Second World War. However, the theory has also been criticised on a number of grounds, including the suggestion that stability requires a hegemon and the idea that the hegemonic power is always willing and able to maintain the international economic order.

Free trade is an economic concept that supports the idea of eliminating trade barriers, such as tariffs and quotas, in order to facilitate trade between nations. Free trade is based on David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage, which suggests that each country should concentrate on producing the goods and services for which it has the greatest relative efficiency, and trade with other countries to obtain the other goods and services it needs. The Great Depression of the 1930s and the rise of protectionism between the wars strengthened support for free trade. The protectionist policies of this period led to a reduction in international trade, unfair competition and a deterioration in international relations, ultimately contributing to the Great Depression. Free trade is often seen as a 'global public good', in the sense that once established, all countries can benefit from it, whether they contributed to its establishment or not. A global public good is non-excludable (no one can be excluded from using it) and non-rivalrous (use by one person does not prevent others from benefiting). So once free trade has been established, it is difficult to exclude a country from its benefits.

In "International Economic Structures and American Foreign Economic Policy, 1887-1934," David Lake uses the theory of hegemonic stability to analyze developments in international economic cooperation and American foreign policies during this period.[1] Lake argues that international economic cooperation is facilitated by the presence of a hegemonic power that possesses both the will and the ability to maintain an open and stable economic system. In this context, the hegemony of the United States in the 20th century is seen as a key factor in the promotion of free trade and international economic cooperation. Lake also examines the internal factors that influence a nation's economic foreign policy, including economic structure and the interests of different social and economic groups. For example, he argues that the rise of protectionism in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries can be explained in part by the interests of agricultural and industrial groups, who favoured high tariffs to protect their domestic markets from foreign competition.

The history of the world economy is marked by alternating periods of opening and closing, often linked to changes in global economic and political conditions.

After 1850, the world economy gradually opened up. This was largely facilitated by technological advances and international trade agreements that reduced trade barriers and encouraged free trade. This period, often referred to as the golden age of globalisation, lasted until 1914, on the eve of the First World War. The inter-war period (1919-1939) was marked by a rise in protectionism and a relative closure of the world economy. This was largely due to the economic disruption caused by the First World War and the Great Depression, which led many countries to adopt protectionist policies to protect their domestic industries. The global economic crisis also led to a rise in nationalism, which exacerbated international trade tensions. In the post-war period, from 1945 onwards, the world economy underwent a new period of openness. This was facilitated by the creation of new international economic institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and by the promotion of free trade by the United States, which had become the hegemonic power after the Second World War. This period of openness led to a spectacular increase in international trade and global economic integration. It is important to note that these periods of openness and closure are generalisations and that there were many variations and exceptions to these general trends, depending on the specific conditions in each country. Moreover, even in periods of openness, there have often been debates and conflicts over the extent and modalities of free trade and global economic integration.

David Lake has argued in his work that international economic cooperation depends on two main factors: concentration of economic power and concentration of economic advantage.

- Concentration of economic power: A hegemonic power, such as the United States in the mid-20th century, can help facilitate international economic cooperation by providing stability and setting the rules of the game for trade and economic relations. A country with considerable economic power can encourage, or even impose, standards and practices that promote economic cooperation. For example, after the Second World War, the United States played a key role in establishing global economic systems such as the International Monetary Fund and GATT (the forerunner of the WTO), which helped promote international economic cooperation.

- Concentration of economic advantage: Lake also argues that international economic cooperation is facilitated when economic advantages are concentrated, rather than diffused. If a small handful of countries hold a large share of the economic advantage (for example, in terms of wealth, technology or production capacity), they will have a greater interest in cooperating to maintain and extend these advantages. On the other hand, if the economic advantages are widely dispersed, cooperation may be more difficult because each country will have less to gain from cooperating.

These arguments offer an interesting perspective on the dynamics of international economic cooperation, focusing on the role of the great powers and the distribution of economic benefits within the international system.

In the theory of hegemonic stability, the likelihood of international cooperation increases when economic power is concentrated in the hands of one or a few states. This is because these states have the capacity and resources to establish and maintain an open and cooperative international economic system. For example, a hegemonic state may be able to bear the short-term costs of setting up such a system, such as the costs associated with negotiating trade agreements or investing in international infrastructure. Such a state may be willing to bear these costs because it can expect to reap long-term benefits, such as access to new markets or improved international economic stability. In addition, a hegemonic state may have the ability to impose its will on other states and ensure their compliance with the rules of the international economic system. This can be done by various means, such as using its economic power to exert pressure on other states, or using its military power to ensure compliance.

Concentration of economic advantage can influence a state's willingness to support and participate in an open and liberal global economic system. In other words, a state that holds a large share of the economic advantage - be it wealth, advanced technology, a highly skilled workforce or other resources - has much to gain from a liberal multilateral trading system. Such a system can enable a state to sell its goods and services to a larger number of markets, attract foreign investment and benefit from greater access to foreign resources and technologies. Conversely, a state that does not have a significant economic advantage may be less inclined to support a liberal multilateral trading system. It may fear that opening its economy to foreign competition will lead to the closure of domestic industries, unemployment and other negative economic consequences. It may then seek to protect its economy by imposing tariffs, quotas or other restrictions on trade.

The presence of a hegemonic, or dominant, power is seen as a key factor in facilitating international cooperation, especially in economic matters. This is because of the disproportionate power and influence that this hegemonic power can exert in shaping the rules, norms and structures of the international system. The idea is that this dominant power has not only the ability, but also a particular interest in promoting a stable and cooperative world order. Since it benefits most from such an order, it is also more willing to bear the costs. For example, it could provide global public goods such as maritime security, help coordinate international economic policies, and even serve as a lender of last resort during financial crises.

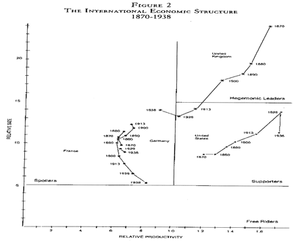

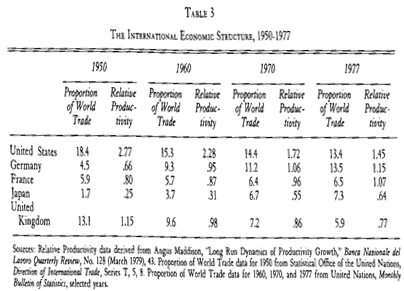

In the framework proposed by David Lake, the X and Y axes create a four-quadrant grid, making it possible to categorise states according to their economic advantage (on the X axis) and their economic power (on the Y axis). The four types of player can be defined as follows:

- Hegemons: These states are in the top right quadrant. They have both a high economic advantage and a high level of economic power. They are the states most in favour of a liberal international economic system and are capable of supporting it.

- The Followers: These states are located in the upper left quadrant. They have a high economic advantage, but lower economic power. They benefit from a liberal international economic system, but do not have the capacity to support this system themselves.

- Free-riders: These states are in the bottom right quadrant. They have a low economic advantage, but high economic power. They have the capacity to support a liberal international economic system, but they have little interest in doing so.

- The Opponents: These states are in the lower left quadrant. They have both a weak economic advantage and a weak economic power. They are the least likely to support a liberal international economic system.

This grid can be used to understand the motivations of different states towards international economic cooperation and the establishment of a liberal world economic order.

By positioning the different countries on this grid, we can obtain a visual representation of their economic power (measured by their share of world trade) and their economic advantage (measured by their productivity).

This gives an interesting perspective on the dynamics of the global economic system. Countries with high productivity and a large share of world trade (the hegemons) are most likely to support and promote a liberal economic system. Those with high productivity but a smaller share of world trade (the followers) also have an interest in supporting this system, but they have less power to do so.

On the other hand, countries with lower productivity but a large share of world trade (free-riders) may have the power to influence the global economic system, but they have less interest in supporting a liberal economic system. Finally, countries with low productivity and a low share of world trade (the opponents) are the least likely to support a liberal economic system.

The historical evolution of these countries in the international economic system can be analysed through the prism of this theoretical framework. In the 19th century, Great Britain was the hegemonic power, with high productivity and a large share of world trade. Over time, however, its productivity and share of trade declined, reducing its hegemonic role. The United States, for its part, began as a "follower", with growing productivity and a moderate share of world trade. Over time, however, it became a global economic power, with high productivity and a large share of world trade, particularly after the Second World War. Germany has also seen its productivity and share of world trade increase over time, although its economic development was later. However, due to political and historical factors, Germany has never assumed the role of hegemonic power.

These different periods reflect the movements of the international economy over the last two centuries.

- 1850-1912: Period of British hegemony. The United Kingdom, thanks to its early industrial revolution and its vast and diversified colonial empire, was able to dominate world trade. The United States, although developing rapidly during this period, did not yet play a major role in the international economy.

- 1913-1929: This period saw the decline of British hegemony and the emergence of the United States as a major economic power. The First World War weakened Britain and other European powers, while the United States experienced significant economic growth.

- 1930-1934: The Great Depression changed global economic dynamics. The United States, although severely affected by the crisis, became the main economic player. However, due to the scale of the crisis and domestic challenges, it was unable to unilaterally support an open global economic system.

- Post-World War II: This period saw the emergence of the United States as an economic and hegemonic superpower. With almost half of the world's industrial output immediately after the war, the US was well placed to shape the global economic order, which it did through institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the GATT (which became the WTO).

David Lake's research has demonstrated the relationship between a country's economic strength, its interest in an open multilateral trading system and the general trend towards international economic cooperation. He has examined several periods in world economic history and identified trends that corroborate the theory of hegemonic stability. In summary, his research has shown that when a single nation dominates the world economy (as was the case for Britain in the second half of the nineteenth century and for the United States after the Second World War), that nation tends to promote a system of free and open trade that benefits all participants. However, when economic power is more balanced between several nations (as was the case in the early twentieth century), international economic cooperation can become more difficult to maintain.

Until 1897, the United States adopted a policy known as the "protective tariff", which aimed to protect domestic industry by imposing high customs duties on imported goods. This had the effect of restricting imports, while encouraging the expansion of US export markets. This type of trade policy is often referred to as 'free-riding', as it takes advantage of the benefits of free trade (i.e. access to foreign markets for its own exports) without bearing the corresponding costs (i.e. opening up its own market to imported products). This is a good example of how national interests can sometimes conflict with the principles of free trade and international economic cooperation.

The Open Door policy, initiated by the United States at the end of the 19th century, was partly a response to the rise of protectionism and the division of China into "zones of influence" by the European powers. The United States, seeking to expand its trade abroad without resorting to direct colonisation, proposed this policy, which aimed to guarantee equal opportunities for all countries wishing to trade with China. The policy was based on the principle of non-discrimination, meaning that all countries should have equal access to Chinese ports open to international trade, regardless of their influence or presence in the country. The Open Door policy was therefore an attempt by the United States to promote free trade and equal commercial opportunities on an international scale. However, its implementation faced many challenges, due to rivalries between the powers and resistance from China itself. Nevertheless, this policy marked an important step in the evolution of the role of the United States as a global power and advocate of free trade. This policy is an important change, as it repudiates the reciprocity approach, tries to curb bilateralism and moves towards multilateralism and non-discrimination.

Between 1913 and 1929, the structure was one of bilateral support with a strengthening of American liberalism. The Underwood Tariff Act, also known as the Revenue Act of 1913, was a key piece of legislation in the history of US trade policy. This act, which was introduced by President Woodrow Wilson, aimed to reduce tariff barriers and promote international trade. The aim of this reform was to stimulate the economy by making it easier to import foreign goods, but also to change the US domestic tax structure by introducing a progressive income tax. This legislation marked a significant departure from the United States' previous protectionist policy. It also laid the foundations for the US tax system as we know it today. The period from 1913 to 1929 is generally regarded as a period of economic expansion and trade liberalisation in the United States, although it was followed by the Great Depression.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which significantly increased US tariffs, is often cited as a factor contributing to the depth and duration of the Great Depression. Tariffs were raised on more than 20,000 imported products, leading to retaliation by America's trading partners and disrupting international trade. Great Britain, for its part, reacted to the Great Depression by abandoning the Gold Standard and implementing protectionist policies, in particular by creating a system of imperial preferences that favoured trade within the British Empire. These protectionist measures disrupted the global economy and contributed to the international instability that preceded the Second World War. After the war, countries sought to avoid repeating the mistakes of the 1930s and created international institutions such as the IMF and GATT (the forerunner of the WTO) to promote economic cooperation and free trade.

After the Second World War, the United States became a global economic superpower and played a key role in shaping the international economic order. The Bretton Woods Agreement, signed in 1944, created the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (part of the World Bank Group) to promote economic stability and international cooperation. The Bretton Woods system also instituted a system of fixed exchange rates, pegged to the US dollar, which was convertible into gold. In addition, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947, was designed to promote free trade by reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers. The GATT was replaced by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995, but its mission to promote free trade and resolve trade disputes remains the same. In short, the economic hegemony of the United States in the post-war period played a key role in establishing an international economic order based on cooperation and free trade.

A state's position in the global economy largely determines its interests and its ability to pursue those interests. This perspective is at the heart of materialist theories of international political economy. A state's objective interests are generally determined by its position in the global economy. For example, a country rich in natural resources may have an objective interest in promoting free trade in those resources. Similarly, a country with a strong manufacturing industry may have an objective interest in protecting that industry from foreign competition. A state's economic strength determines its ability to pursue its interests. A country with a strong economy will have more resources at its disposal to pursue economic policies and influence international economic norms and rules. Furthermore, a country with a strong economy is often better placed to resist external economic pressures and maintain its economic sovereignty. These factors - position in the global economy, objective interests and economic power - all play a key role in how a state navigates the international political economy.

The key points of the hegemonic stability theory and the role of a country's material position in the world economy are.

- International economic cooperation depends to a large extent on the existence of a hegemonic power. This power, usually a nation with a strong economy and an interest in maintaining an open trading system, has the resources to shape the rules of the international economic system and encourage other countries to adhere to them. Moreover, it is in the interest of this hegemonic power to support stability and cooperation, as this promotes economic growth and global interdependence, conditions which generally strengthen its dominant position.

- A country's foreign economic policy is largely determined by its relative material position in the world economy. This position influences both a country's economic interests (what it wants from the international economic system) and its power resources (its ability to achieve these objectives). A country with a strong economy and a dominant position in certain sectors may have both the interest and the ability to influence the norms and rules of the global economy in its favour.

These ideas are at the heart of many analyses of international economic policy, and they continue to be relevant to understanding the dynamics of today's global economy.

The architecture of the international economy plays a crucial role in determining power relations between countries. It influences foreign economic policies and countries' negotiating strategies.

- Distribution of economic power: A country with a powerful and diversified economy will have considerable power on the international economic stage. It can use this power to influence the rules and standards of the global economy, promote its own economic interests and, in some cases, shape the economic policies of other countries.

- Economic interdependence: Increased economic interdependence, partly due to globalisation, means that decisions taken by one country can significantly impact others. Countries dependent on exports or imports of a certain product, for example, can be strongly affected by changes in the economic policy of the producing country.

- Role of international economic institutions: Institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation also play an important role in structuring global economic power. These institutions can influence the economic policies of member countries and provide a forum for resolving economic conflicts.

- National strategies: Each country may have its own strategy for navigating this global economic structure, based on its own economic interests, capabilities and constraints. This may include such things as seeking bilateral or multilateral trade agreements, manipulating its own currency or adopting policies of protectionism or trade liberalisation.

The international economic structure provides the framework within which countries interact and negotiate their foreign economic policies.

Advantages of the interest-based approach[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

One of the key strengths of the interest-based approach is that it focuses on identifying the stakeholders and their motivations. Here's why:

- Rational basis: Actors are assumed to be rational, i.e. they seek to maximise their interest in their actions and interactions. This makes it easier to predict their behaviour and analyse their motivations.

- Understanding motivations: By identifying the specific interests of stakeholders, it is possible to better understand their motivations and anticipate their actions.

- Analysis of interactions: The interest-based approach provides an analytical framework for understanding how stakeholders interact with each other in a political or economic system. These interactions can often explain the overall behaviour of the system.

- Adaptability: Stakeholders' interests can change over time in response to new information or changes in the environment. The interest-based approach is capable of taking these changes into account and adapting its analyses and predictions accordingly.

This approach is based on the assumption that actors are perfectly rational and always capable of identifying and pursuing their best interests. In reality, this may not always be the case. Actors can sometimes act irrationally, be influenced by cognitive biases, or lack the information to make perfectly rational decisions.

One of the strengths of the interest-based approach is precisely its ability to explain how changes in the power relationships and interests of stakeholders can influence outcomes. To put it simply, if a stakeholder's power or interests change, this can affect its behaviour or its ability to influence outcomes. For example, if a company acquires a significant technological advantage, this could change its interest in certain regulations or policies and potentially affect the outcome of these policies. This is why interest-based analysis is often used in studies of international relations, political economy and other fields where power relationships and the interests of players play a key role.

The interest-based model of analysis can also be applied to the following example. The emergence of the working class as an important political force in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries can be seen as a consequence of changes in economic and social power relations. With industrialisation, the working class became an indispensable part of the economic system. This change not only strengthened the economic power of the working class, but also created new interests, for example in working conditions and workers' rights. This led to the rise of the welfare state and social policies designed to protect workers from the risks inherent in the workplace. This can be seen as the result of pressure exerted by the working class, which, thanks to its increased importance in the economy, had acquired the necessary power to assert its interests.

The formation of political coalitions is a key aspect of the interest-based approach. A coalition can generate significant political force by bringing together various groups or actors with common or complementary interests. This can enable these groups to influence policy and advance their common goals. For example, in many democratic political systems, separate political parties may form a coalition to obtain a parliamentary majority. Such coalitions may include parties which, although ideologically different, share certain common policy objectives. Coalition-building can also be important in non-political contexts, such as social movements or trade unions. By uniting different groups of people around a common goal, these coalitions can exert significant pressure for social or political change. However, coalition-building can also lead to compromises, as different actors or groups may have different priorities or interests. Managing these differences is often a crucial part of the process of forming and maintaining effective coalitions.

Harold Lasswell proposed that politics is the study of "who gets what, when and how". This perspective is very much in line with the interest-based approach, which focuses on how different actors - be they individuals, social groups or nations - use their power and resources to get what they want from the political system. According to this view, politics is largely about resource allocation and decision-making. Political actors struggle to obtain the best possible resources and benefits for themselves or their interest groups. Therefore, an interest-based analysis helps to understand power dynamics, how resources are distributed and who are the winners and losers in different political contexts. It offers a way of understanding and explaining political behaviour by focusing on the interests and motivations of the actors involved.

Many political conflicts can be seen as arising from competition for limited resources. These resources, such as money, jobs or access to certain industries or markets, may be economic. But they can also be more social or symbolic, such as status, prestige, influence or control over certain institutions or policies. The interest-based approach argues that political actors, whether individuals, groups or nations, will act to maximise their interests, i.e. to obtain as many of these resources as possible. Furthermore, these actors use their power and resources to influence political processes and public policies in ways that favour their own interests. This is why many political conflicts can be interpreted as being fundamentally conflicts of interest. And these conflicts of interest are often rooted in material issues, although they may also concern symbolic or ideological issues.

Disadvantages of the interest-based approach[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Although the interest-based approach is very useful for explaining certain political dynamics, it has certain limitations. One of these is that it can neglect the impact of institutions and ideas on politics.

- The role of institutions : Institutions, whether formal institutions such as constitutions and legal systems, or informal institutions such as social norms, can shape the interests of actors and constrain them in their actions. For example, a multi-party system of government can encourage political parties to form coalitions, thereby modifying their strategies and interests. Institutions can also create opportunities or obstacles for certain interest groups, thereby influencing political outcomes.

- The importance of ideas: Ideas, whether ideologies, beliefs or values, can also have a major impact on politics. They can influence people's interests, their perception of what is possible or desirable, and the way they interpret and respond to political problems. For example, liberal ideas about individual freedom and the free market can influence a country's economic policy, even if these ideas do not directly correspond to the material interests of all the players.

So, while the interest-based approach is an important analytical tool, it needs to be complemented by a focus on institutions and ideas to gain a fuller understanding of political dynamics.

Exploration de la théorie du choix rationnel[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Mancur Olson est née en 1932 et décédé en 1998. Il fut un économiste américain ayant obtenu une thèse de doctorat à l’Université de Harvard, puis a enseigné à l’Université de Princeton et à l’Université du Maryland. Il est connu pour avoir laissé un héritage important. En 1965 il a publié La logique de l’action collective. Dans ce livre, Olson examine pourquoi certains groupes sont capables d'agir collectivement pour poursuivre leurs intérêts communs, tandis que d'autres échouent. Il avance l'idée du "passager clandestin" (free-rider), selon laquelle les individus ont tendance à éviter de contribuer à un bien collectif en espérant que d'autres le feront à leur place. Cela peut entraver la capacité d'un groupe à agir de manière collective. Olson soutient que des incitations sélectives, comme les avantages réservés aux membres actifs, sont souvent nécessaires pour surmonter ce problème. En 1982 il publie The Rise and Fall of Nations. Dans cette œuvre, Olson étend son analyse de l'action collective à l'échelle des nations. Il soutient que la stabilité politique à long terme peut en fait entraver le progrès économique, car elle permet à des "groupes de distribution" (comme les syndicats ou les lobbys d'entreprises) d'accumuler du pouvoir et de mettre en place des politiques qui bénéficient à leurs membres au détriment de la société dans son ensemble. Selon Olson, ce processus peut expliquer pourquoi certaines nations déclinent tandis que d'autres connaissent une croissance rapide après des perturbations majeures comme une guerre.

Group behaviour according to rational choice theory[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Olson is best known for his theorising on the behaviour of groups, whether individuals or groups within a society, and he highlighted a paradox of collective behaviour. This approach underpins the idea that when individuals or companies have a common interest, they will act collectively to defend that interest. In other words, individuals or groups with a common political interest will join forces and mobilise to defend that interest; it could also be citizens organising themselves to oppose a lobby, or consumers faced with monopoly or oligopoly situations forming a consumer association to counteract them.

However, Olson sets out to show that this preconceived idea is false. He set out to show what would be the appropriate individual behaviour of a consumer who wanted a boycott to oppose the monopoly, or what would be the appropriate behaviour of a worker who wanted the threat of a strike or the organisation of a trade union to enable him to obtain a higher wage. Note that the consumer or worker will spend time or money either organising a boycott or fighting a strike. The result will be weak, because each individual will only receive a tiny part of the fruits of his action, the individual will only obtain a tiny fruit of the action undertaken by the group behaviour. The reason for this is that the good or service provided by a consumer association or trade union has the property of being a collective or public good. In other words, once the good or service has been created, it will benefit all the group members concerned.

The success of a boycott or strike will result in a lower price or higher wage for all individuals in the category concerned. This characteristic is also known as non-exclusion: individuals cannot be excluded from consuming the good even if they have not contributed to its production. Individuals cannot be excluded from consuming the good even if they have not created and produced the good in question. Thus the member or a large group will only receive a minimal share of the fruits of their action. On the contrary, it is more advantageous to let others carry out this task, but obviously the others have no interest in mobilising themselves and being the ones to produce the collective good. There are no incentives for the individual or for others, from which we deduce that we should not see the emergence of joint actions on the part of groups. Large groups made up of rational individuals will not act in the group's interests.

This type of theory is really interesting and important. Consequently, a whole host of public goods in a society should be difficult to create, produce and supply. There would be an imbalance between public goods' demand and supply. At the societal level, this postulate of rational individuals in a sub-optimal equilibrium means that it is desirable for certain public goods to be created, but not to be supplied. A whole body of literature exists on the conditions that allow collective goods to be supplied, despite the problems of collective action and the free rider problem. For example, justice or the army can be considered a public good because everyone benefits from them, but the incentive found by states is to make contributions through compulsory taxation. In short, cartels, pressure groups, etc. should not exist unless citizens support them for reasons other than the expectation of the public goods they provide. Unless there are other reasons, individuals have no interest in mobilising. However, if we look at our societies, pressure groups do exist.

The drivers of collective action[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

We might wonder about the other logic that explains the existence of collective action in our societies. As Olson suggested, specific incentives (such as benefits reserved for active members) can encourage individuals to contribute to collective action. Mancur Olson proposed the concept of selective incentives to solve the free rider problem in the logic of collective action. Selective incentives are rewards (positive incentives) or sanctions (negative incentives) that are applied in a differentiated way depending on the participation of individuals in collective action. These incentives aim to encourage people to contribute to the collective good.

Here are a few examples to illustrate this concept:

- Positive incentives: These are designed to reward those who actively participate in collective action. For example, an organisation might offer exclusive benefits to members who contribute to a common project, such as discounts on products or services, privileged access to events or resources, or public recognition of their contribution. Unions often provide additional benefits to members, such as legal services, insurance, fringe benefits, training, and sometimes even leisure benefits or discounts from certain businesses. These benefits, which can be seen as positive selective incentives, are exclusive to union members and are not available to non-members. Therefore, although the benefits of unionism (such as pay rises or better working conditions) are often available to all workers, whether union members or not, these positive selective incentives can encourage workers to join the union. This strategy is commonly used by unions to increase their membership, which is crucial to strengthening their bargaining power with employers and their influence on public policy.

- Negative incentives: These are designed to punish those who do not participate in collective action. For example, a trade union might impose financial penalties on workers who do not join a strike. Or a community could exclude members who do not contribute to the maintenance of a common resource. The example of compulsory voting in Belgium is a perfect illustration of a negative selective incentive. In Belgium, every citizen aged 18 or over is obliged to vote in elections. If a citizen fails to vote without a valid reason (e.g. illness, absence from the country, etc.), they can be fined. This obligation to vote is therefore a negative incentive designed to encourage participation in elections, which are considered to be a public good. This measure has enabled Belgium to have one of the highest voter turnout rates in the world. However, it should be noted that the effective implementation of such sanctions can be complex and costly, and their effectiveness may depend on other factors, such as confidence in political institutions, civic education, etc.

Selective incentives are a solution to the paradox of group behaviour, also known as the "free rider problem", identified by Mancur Olson. This paradox refers to the natural tendency of individuals not to participate in collective action in the hope of reaping the benefits without contributing to the effort. When selective incentives are sufficiently strong, they can encourage participation and mitigate this problem. For example, if a union offers free legal services to its members, a worker may be more inclined to join a union in order to benefit from this assistance, even though he or she could theoretically benefit from improved working conditions without joining the union. In summary, selective incentives, whether positive (such as exclusive benefits for members) or negative (such as penalties for non-participants), can be an effective strategy for overcoming the free rider problem and encouraging participation in collective action.

Impact of group size[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Group size plays an important role in the dynamics of collective action and in the way in which free-rider problems are managed. Mancur Olson's theory shows that group size can have a significant impact on the success of collective action. In small groups, members are more likely to know each other personally, which can create social incentives to participate. For example, if a member does not contribute to the collective effort, they may be stigmatised or excluded from the group, which can be seen as a negative selective incentive. On the other hand, contributing to the collective effort can lead to increased recognition and self-esteem, which can be seen as a positive selective incentive. On the other hand, in large groups, the effect of an individual's contribution or non-contribution to the collective effort is less perceptible and the social incentives to participate are often weaker. This is why the free rider problem is generally more pronounced in large groups. To overcome this problem, stronger selective incentives, both positive and negative, may be needed to encourage participation in large groups.

In small groups, personal interaction, closer social ties and proximity help to create social pressure and a greater sense of responsibility towards the group. These factors can help overcome the free rider problem and encourage cooperation and active participation in collective action. If a group member chooses not to participate or contribute to the collective effort, he or she may be subject to social sanctions, such as stigmatisation or exclusion, which constitutes a negative selective incentive to participate. At the same time, group members who actively contribute may be rewarded with increased social recognition and respect, which constitutes a positive selective incentive. It should be noted that while these mechanisms may be effective in small groups, they may be more difficult to implement in large groups due to the relative anonymity of members and the dilution of individual responsibility.

In a small group, cooperation is easier to achieve because personal interactions are more frequent and more direct, which can create a climate of trust and reciprocity. Social control is a form of selective incentive that can work both ways. On the one hand, there is negative social control, which discourages free rider behaviour by punishing those who do not contribute to the collective effort. On the other hand, there is positive social control, which rewards those who actively contribute to collective action by giving them recognition and respect. This is why, in a small group, members are more likely to behave cooperatively and actively participate in the collective effort. However, in large groups, this dynamic can be more difficult to maintain because of the relative anonymity of members and the dilution of individual responsibility.

Homogeneity vs. group heterogeneity[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Heterogeneity within a group can make collective action more difficult for several reasons. Firstly, it can increase the complexity of coordination, as different members may have different priorities, expectations and perspectives. Secondly, heterogeneity can exacerbate tensions or conflicts within the group, which can weaken the unity and solidarity needed for collective action. Mancur Olson has pointed out that the homogeneity of a group facilitates collective action by creating a shared sense of identity and interest. Homogeneous groups are more likely to share common goals, values and norms, which can enhance cooperation and cohesion. In the case of ethnic cleavages, for example, they can introduce divisions and tensions within a group, complicating the effort to take collective action. Cultural, linguistic or religious differences can make communication and mutual understanding more difficult, which in turn can hamper coordination and cooperation. This is why it is often necessary to work on building trust and mutual understanding to overcome these challenges and facilitate collective action in heterogeneous groups.

Heterogeneity within a group can make collective action more difficult for several reasons. Firstly, it can increase the complexity of coordination, as different members may have different priorities, expectations and perspectives. Secondly, heterogeneity can exacerbate tensions or conflicts within the group, which can weaken the unity and solidarity needed for collective action. Mancur Olson has pointed out that the homogeneity of a group facilitates collective action by creating a shared sense of identity and interest. Homogeneous groups are more likely to share common goals, values and norms, which can enhance cooperation and cohesion. In the case of ethnic cleavages, for example, they can introduce divisions and tensions within a group, complicating the effort to take collective action. Cultural, linguistic or religious differences can make communication and mutual understanding more difficult, which in turn can hamper coordination and cooperation. This is why it is often necessary to work on building trust and mutual understanding to overcome these challenges and facilitate collective action in heterogeneous groups.

The heterogeneity of a group can complicate collective action for a number of reasons.

- Difficulty in reaching agreement on the collective good: If group members have different interests, values or beliefs, they may have different visions of what constitutes a collective good, i.e. what is beneficial for the group as a whole. It can therefore be difficult to reach a consensus on the group's objectives or on how to achieve these objectives.

- Reduced effectiveness of selective social incentives: Selective social incentives, such as social approval for those who contribute to collective action and disapproval for those who don't, may be less effective in a heterogeneous group. If group members have distinct social networks or different values, they may be less sensitive to these incentives.

- Reduced social cohesion: In a heterogeneous group, contact between members may be more limited, particularly if divisions exist on the basis of ethnicity, religion, social class or other characteristics. This can weaken social cohesion and the group's collective identity, which in turn can reduce members' willingness to contribute to collective action.

It is therefore important to take these challenges into account when planning or managing collective action in a heterogeneous group.

In an ethnically heterogeneous group, social control is often more difficult to exercise for a number of reasons.

- Lack of cohesion: Cultural, linguistic, religious and other differences between different ethnic groups can hinder the formation of a common sense of identity or group objectives, making it more difficult to achieve the cohesion needed to take collective action.

- Communication and understanding: Language or cultural barriers can make communication within the group more complex, limiting the effectiveness of social control. In addition, cultural differences can lead to misunderstandings or disagreements about what constitutes acceptable or desirable behaviour.

- Repercussions of existing divisions: Pre-existing ethnic tensions can exacerbate in-group conflict, making social control more difficult. Furthermore, if one ethnic group is perceived to dominate the group, this can lead to resentment and resistance, which can also undermine the effectiveness of social control.

However, it should be noted that ethnic heterogeneity does not necessarily preclude collective action. In certain circumstances, and with good management, an ethnically heterogeneous group can manage to overcome these challenges and take effective collective action.

Cost of individual contribution[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

One of the crucial aspects of Mancur Olson's theory is the concept of individual contribution cost. According to this theory, if the cost of contributing to a collective good is low for an individual, then that individual is more likely to participate in the collective effort. On the other hand, if the cost of contributing is high, then the individual will be more inclined to become a "free rider", i.e. to enjoy the benefits of the public good without contributing to its financing or realisation. This can be understood intuitively: if we consider that the contribution to a collective effort (whether in time, money or resources) is relatively small compared to the benefits we derive from it, we will be more inclined to participate. But if the cost of the contribution is too high, people may be dissuaded from participating, hoping instead to benefit from the efforts of others.

According to Olson's theory, the lower the cost (in time, effort or resources) of an action for an individual, the more likely they are to take part in that collective action. For example, signing a petition or voting generally doesn't require much time or effort, which makes these types of collective action fairly common. On the other hand, actions that require a greater commitment, such as volunteering for a cause or taking part in events that can be time-consuming and require physical effort, are often less common because the cost to the individual is higher.

More specifically, activist engagement that requires mobilisation over time is persuasive in such activities and efforts: "Joint action to produce collective goods is more likely in groups with selective incentives than in others, and small groups are more likely to engage in such action than larger ones." According to Olson, the production of collective (or public) goods is more likely in groups where selective incentives are available to encourage member participation. These incentives can be positive, such as rewards for those who participate, or negative, such as sanctions for those who do not. Furthermore, according to Olson, small groups are generally more effective for collective action than large groups. In a small group, each member has a greater share in the production of the collective good, which can be an additional incentive to participate. In addition, social control is often stronger in small groups, which can also encourage participation.

In his view, a group with common interests will not necessarily mobilise to defend those interests unless there are selective incentives to encourage individual participation. In the case of the unemployed, despite the fact that they share a common interest (finding work or improving conditions for the unemployed), their situation could make organisation and collective action difficult. Geographical dispersion, the diversity of individual situations, lack of resources, or the absence of organised leadership could all contribute to the absence of strong collective action. On the other hand, unemployment, especially at high levels, can engender a sense of powerlessness or disillusionment that could discourage activism. In addition, unemployed people may be more focused on looking for work on an individual basis rather than mobilising for wider change.

In Spain, for example, unemployment affects 25% of the working population, a rate that rises to 40% among young people. Yet the unemployed are not represented by a specific organisation to defend their interests. Olson's theory sheds some light on this situation. Individuals on low or modest incomes do not generally belong in large numbers to groups defending the most disadvantaged. On the other hand, smaller social groups, such as the professions, often have organisations dedicated to defending their interests, despite their relatively small numbers. In most societies, it is these types of groups that are organised and campaign for their interests.

According to Mancur Olson's theory, this can be explained by several factors:

- The paradox of collective action: Individuals who could benefit most from collective action (such as the unemployed or people on low incomes) may also be those who have the least resources to organise and participate in such action. On the other hand, smaller and better-off groups, such as the professions, may be better able to overcome these barriers and organise to defend their interests.

- Selective incentives: Organisations that offer specific benefits to their members (such as legal services for trade unions) may be more effective in attracting members and motivating them to participate in collective action. However, the unemployed and those on low incomes may have less access to such incentives or fewer means of obtaining them.

- Group size and homogeneity: Small groups of individuals with common interests (such as the professions) may be more easily organised and may exert stronger social control to encourage participation in collective action. On the other hand, the unemployed and people on low incomes form a larger and more heterogeneous group, which can make organisation and collective action more difficult.

In short, Olson's theory of collective action can help us to understand why some groups are more organised than others, and why certain social and economic challenges, such as mass unemployment, can be difficult to resolve through collective action.

The role of interest groups and bureaucratic structures[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In his book The Rise and Decline of Nations, Mancur Olson seeks to understand the underlying causes of the rise and fall of nations. He explores the various economic, social and political factors that contribute to the complex dynamics of growth and decline. His main thesis is that stable societies tend to develop powerful interest groups that oppose change, which can ultimately undermine economic growth and social progress. On the other hand, societies that have experienced major shocks (such as wars or revolutions) are often better able to introduce radical reforms that stimulate economic growth.

According to Mancur Olson, the rapid growth of Germany and Japan after the Second World War can largely be explained by the total destruction of their pre-existing social and economic structures during the war. These countries had to rebuild their economies and societies from scratch. This created a situation where old interest groups and inefficient bureaucratic structures were eliminated, allowing deep economic reforms and more efficient structures to be put in place. Total destruction also created a sense of urgency and necessity that allowed radical economic reform policies to be adopted that, under normal circumstances, would have been blocked by existing interest groups. These new policies have encouraged competition, innovation and efficiency, leading to very high rates of economic growth. In addition, Germany and Japan benefited from the help and support of the United States in their reconstruction efforts, through the Marshall Plan for Europe and direct support for Japan. It is this combination of factors that, according to Olson, explains the "economic renaissance" of these two countries after the war.

According to Mancur Olson's theory, Britain's slower economic growth and ungovernability after 1945 can be explained by the accumulation of specialist interest groups (or 'distribution groups' as he calls them) over time. These groups tend to form and consolidate in stable societies, where they seek to promote their own interests, often to the detriment of society as a whole. For example, powerful unions may secure benefits for their members, such as higher wages, but this can lead to higher costs for companies and a loss of competitiveness for the economy as a whole. Similarly, well-established companies may seek to protect their positions through favourable regulations that hinder competition and innovation. According to Olson, such behaviour can, in the long term, hamper economic efficiency and the government's ability to implement reforms. This would be the case in Britain after 1945, where the accumulation of such interest groups and bureaucracy would have led to relative economic stagnation and governance challenges. This contrasts with countries such as Germany and Japan, which were able to start afresh after the Second World War, unfettered by these entrenched interest groups.

In his book "The Rise and Decline of Nations" (1982), Mancur Olson explains that some nations prosper while others stagnate or decline. His theories are fairly wide-ranging, encompassing the analysis of the rise and decline of various nations throughout history, including Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, India and China. With regard to Britain, France and the Netherlands, Olson examines how these countries emerged as dominant powers at the dawn of the modern era. He attributes this in part to the accumulation of property rights, stable laws and political institutions that encouraged trade and investment. These factors enabled these countries to reap the full economic benefits of the early industrial revolution. Olson offers a different perspective on China and India in the 19th century. He argues that these countries experienced a long period of stagnation due to a lack of well-defined property rights and heavy bureaucracy, which hampered economic development. Furthermore, in these countries, established interest groups (such as merchant guilds and castes) could have blocked reform and innovation, contributing to their relative stagnation during this period.

Details of rational choice theory[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The rationality of ends and means[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Rational choice theory, apart from the work of Olson, represents a dominant theoretical and methodological tradition in many disciplines, including economics, sociology and political science. This approach focuses on the idea that individuals make rational decisions based on their personal interests. According to this theory, individuals are seen as rational actors who seek to maximise their utility or profit. The choices they make are therefore the result of a rational assessment of the costs and benefits of the different options available. Individuals are expected to choose the option that offers them the best cost/benefit ratio. Rational choice theory is particularly useful for understanding and predicting behaviour in situations where individuals have clear options and the consequences of their choices are relatively predictable. However, this approach has also been criticised for its assumption that individuals are always perfectly rational and always able to accurately assess costs and benefits, which is not always the case in reality.