Political and religious currents in the Middle East

| Professeur(s) | Yilmaz Özcan[1][2] |

|---|---|

| Cours | The Contemporary Middle East: States, Nations, and Communities |

Lectures

Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism is an ideology according to which Arabs constitute a people united by the specific characteristics (cultural, religious, historical) that bind them and which must be constituted at the political level: cultural/ethnic boundaries must correspond to political boundaries. Arab nationalism has been called into question since the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Ba'athism represents the Ba'ath party movement, popular, while Nasserism represents it from above, the elite.

Its origin dates back to the Arab revolt of 1916, although the beginning of the process goes further back in time: in 1517, the Ottoman Empire conquered Egypt (capture of Cairo); in 1533, Baghdad (now Iraq) was taken by the Ottomans, who then controlled all the Ottoman territories; 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt, which marked the beginning of the Ottoman-British alliance; etc. The Ottoman Empire was the first Arab country to be conquered by the Ottomans.

Another source of this process is the revolution of the Young Turks. From 1909 onwards, the movement fell into authoritarianism (Cf. massacre of the Armenian population). Moreover, the Turkish language was put at the centre of the institutions and interests of the movement. A certain number of westernized Arab intellectuals organised the first general Arab congress in Paris in 1913. The Egyptian delegate went there as an observer and did not consider himself an Arab, for cultural reasons, which had evolved differently because the Egyptians were under British domination.

Nevertheless, the Arabs, like the territories, were divided. But because of the First World War, as well as because of Nazi propaganda in the region and the influence of intellectual activities in Europe, pan-Arabism is emerging. Nevertheless, the failure of pan-Arabism left a vacuum that allowed Islamism to develop.

Pan-Arabism

The traditional notables, in the context of the First World War and a centre/periphery perspective, will try to create alliances with Westerners: we can speak of the Sheriff Hussein of Mecca - his attempt to create an Arab kingdom will fail in favour of several mandates. The disappointment is great. At the end of the war, Faisal was accompanied by Sati Al Husri, who became the minister of education and the first theoretician of Arab nationalism. He was influenced by the German conception of the nation, he favoured the linguistic and cultural aspects as determining elements of what is Arab and what is not.

This evolution will continue during the inter-war period as a result of the breaking of promises made during the conflict - the Sykes-Picot agreements are a good example of this. Some elements will accelerate this process: fascist or Nazi propaganda - a pro-Nazi coup d'état is emerging in Baghdad. There is also a lot of debate about Arab independence.

Baasism

The annexation of Santiago de Alexandria (Syria) by Turkey will provoke the emergence of Ba'athism, the Arab resurrection. The first congress of the Ba'ath Party took place in 1947 and placed great emphasis on unity (territory), independence (autonomy) and Arab socialism (reforms to achieve the modern state). Another characteristic remains the non-confessional and therefore secularist approach of the movement, as well as the fact that minorities must assimilate to the Arab nation and a predominant anti-Zionism.

Michel Aflak (1910-1989), a Greek Orthodox from Damascus, founded the Baath Party in 1943. He will hold the post of general secretary of the party in both Syria and Iraq.

This ideology will evolve and we are witnessing the development of national sections in different countries. As soon as Ba'athism was assimilated to power, reforms were present, as well as a form of violence (division, war, repression). As early as 1958, the Ba'athist project took shape through the foundation of a United Arab Republic (which failed in 1961). In March 1963, the Baath Party came to power in Syria with the same consequences - including confessionalization.

Nasserism

It is an Arab political ideology based on the thinking of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. It is about strengthening the unity of the Arabs, the total independence (1922 in Egypt) of the Arabs by focusing on Arab socialism. An ideology that emerges after the establishment of power (unlike Ba'athism). The foundation in 1958 of the United Arab Republic is one of the expressions of Nasserist thought. One of the aims of the United Arab Republic was to establish Syria as an Egyptian province. The Camp David agreements signed between Egypt and Israel in 1979 marked the end of pan-Arabism according to some experts. Egypt will be excluded from the Arab League.

The League of Arab States (Arab League)

In 1944, the Egyptian government considered a structure for the development of a federation of Arab countries. Several projects were proposed: that of Greater Syria (West Bank and Transjordan), the Fertile Crescent, the creation of a league, etc.. The Alexandria Protocol laid the foundations for the future association which would become effective one year later, in 1945, under the acronym of the League of Arab States. Its founding members are Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and North Yemen. Its system makes decision-making complicated. The Arab world is characterized by a very great diversity, which makes any regional initiative very complicated. In addition, there is little economic exchange between Arab countries.

In 1971, the creation of the Union of Arab Republics did not lead to any concrete consequences. In the Maghreb, attempts were made to bring states together, without success. After the Islamic revolution in Iran, the Gulf countries set up a consultative council, but without success.

Pan-Islamism

Wahhabism

One of the sources of Arabism or Arab nationalism is particularly important: Wahhabism, which can be defined as the will to purify Islam, the conquest of souls, according to the original principles, the salaf ("ancestors", "predecessors"), the first three generations of Islam. Its protagonist Mohammed Ben Abdelwahhab (1703-1792), preaching a reformist and puritanical Islam, allied himself with Mohammed Ibn Saud (1710 - 1765) in this project and challenged the Ottoman Caliphate, leading to a growing politicization on this issue. The pact would lead to the creation of the first Saudi emirate, that of Dariya. Ben Abdelwahhab would be in charge of religious matters and Ibn Saoud would be in charge of political and military matters. This agreement became a "pact of mutual support" and power-sharing between the Al Saud family and the followers of ben Abdelwahhab, which remained in place for almost 300 years, providing the ideological impetus for Saudi expansion.

Arab modernism or "nahda"

The Arab renaissance or Nahdah is taking shape in Egypt: Al Afghani (1839-1897), the leading theorist of Arab modernism, settled there at the age of 33. With the help of Mohammed Abduh, mufti (interpreter of Muslim law), he founded Islamic modernism with the aim of reforming many institutions. This process will also lead to a cultural development based on the historical rediscovery of the Arab world: a cultural Arabism marked by a return to the historical and glorious heritage. In this movement, no confessional distinction is made, the emphasis is on language. Political parties are created, associations, leagues and organizations are created.

The pan-Islamicism of Abdülhamid II (1842-1918) represents a more political aspect of Arab nationalism. Procedures of centralization, investigation and repression are put in place. Some activists are exiled to Egypt.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict

The notion of Palestine predates the Ottoman Empire: it comes from antiquity. During the period of Islamic expansion, the Holy Land was referred to as the Holy Land. As time went by, especially after the European conquests, the term Palestine was used. The inhabitants of this region will then use this term to define the territory where the future Arab state will be established.

In the 19th century, many rivalries claimed the territory (churches, states, powers, etc.), which led to conflicts taking place in the holy places. This is why, in the case of Jerusalem, the city was placed under the direct authority of Constantinople, whereas this was not the case in the rest of the Ottoman Empire.

Following the demise of the Ottoman Empire, the British continue to use the word "Palestine" or "Southern Syria" to define their mandate. On the side of Israel, they speak of an "Arab state", which has yet to come into being. The process of Arab nationalism is not very clear at the beginning - we note the waves of migration as well as the politico-religious stakes as determinants of the latter. The defence of the land is done in the name of Arabism.

The balance of power on the ground is clearly in favour of the Zionists. Tensions between the two sides will lead to massacres, assassinations and attacks. During the Great Uprising of 1938-1939, the Israeli ruling class is assaulted by the Arabs. The British, taking into account the difficulties, ask for the help of the League of Nations, which will set up the Peel Commission to carry out, in 1937, the first partition plan between the two states. It is refused by the Arab side, as are the Jewish revisionists - while the Jews in general accept it. Tensions continue until 1947, when the British hand over their mandate to the UN, which will propose a second partition plan.

The Palestinian exodus of 1948 or Nakba ("catastrophe") refers to the civil war which causes the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Arabs from the territory. On the other hand, the refugee issue is linked to the formation of the Palestinian diaspora. The movement therefore redefined itself around the years 1958-59 to emphasize Palestinian identity - and to detach itself from Arab leaders. Yasser Arafat, who dominated the movement, no longer had as his objective the defence of Arabism or the creation of an Arab state, but rather a claim by the diaspora for the creation of a Palestinian state. From then on, the armed struggle becomes the means for the liberation of Palestine.

As early as 1963, military operations were conducted from Jordan against Israel. Arafat is beginning to be appreciated by Arabs in view of its military successes. Quickly, the Israeli retaliation forced Jordan to expel the Palestinian fighters, who would settle in Lebanon. Things changed there as well: several events, including the assassination attempt on the Israeli ambassador in London, led to Operation Galilee Peace, with Israel invading Lebanon in June 1982 to divert rockets based there and repel the Syrian army. Moreover, the image of the Palestinians in Lebanon declined as they also found themselves involved in the civil war. The movement moves its headquarters to North Africa. While it was revising its objectives downwards - even considering the idea of two states - it was saved by the intifada, a popular movement to revitalise Palestine. At the end of the Cold War, this will lead to the Oslo agreements, Yasser Arafat is praised.

On the other hand, the negotiations with Israel fail, particularly on the question of settlements and refugees. The nationalist milieu, and Hamas in particular, accuses Arafat of incompetence, corruption and nepotism. As a result, Hamas gains political power, although it advocates a more Islamic approach to the Palestinian movement: this is the transition to the third phase.

The armed struggle is resumed, just like the intifada, in a desire for jihad against the Jews. In 2006, Hamas, a Palestinian Islamist movement composed of a political and an armed wing, won elections, but is also regarded as terrorist by European countries and the United States. In particular, the notion of two governments within Palestine is emerging. Nowadays, the territory is fragmented, unemployment and corruption make the authority fragile.

The Kurdish case

The movement has to fight against the states resulting from the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. The word "Kurdistan" has existed since at least the 12th century. The war between the Sepheviks (Iranians) and the Ottomans in 1514 marked the first fracture in the land of the Kurdish people. It is all a question of what is at stake: some Kurds side with the Shah and some with the Ottomans. In 1639, a treaty in principle established the borders of the territory: de facto, they had only existed since the 1940s.

A new political era took place under the sign of pan-Islamism and the autonomy of the Kurds was abolished, although certain benefits and rights were created for the said population (tribes). This did not prevent rivalries between them and neighbouring populations, such as Armenia, for example.

In 1919, the Kurdish political organisation was newly created: this was the first sign of Kurdish nationalism. The Treaty of Sèvres provides for the autonomy of the Kurdish territory, which could lead to independence. However, the state will not come into being:

- The settlement areas were divided (France, GB, Russia) and the Allies were not willing to question their plan.

- Armenian autonomy raised conflicts over the targeted territories.

- Kurdish nationalism is weak and cannot mobilise the masses. The community is undermined by indecision: the possibility of refusing Sèvres to link the community to Turkish nationalism for a single territory is one of them.

Turkish Kurdistan

In 1924, the words "Kurdish" and "Kurdistan" were banned in Kemalist Turkey as part of a process of assimilation and acculturation: populations were displaced, theorising that Kurds were in fact "mountain" Turks - which explains the differences at the linguistic and cultural levels. A context of permanent revolt is thus emerging. But Turkey's identity crisis at the end of the Second World War was to lead to the development of an interest in the Kurdish language, culture and history, a revival of Kurdish nationalism. In the end, coups d'état and repression with nationalist tendencies during the following years undermined the interests of the Kurdish community.

The armed struggle began in 1984, at the instigation of the PKK (the Kurdish Labour Party), supported by the Russian communist left. Since 1946, the Soviet Union has taken a close interest in the situation in this region: the Communists support Iranian Azerbaijan, self-proclaimed autonomous republic against the Iran of Rezah Pahlawi (son) - Cf. Iranian-Soviet conflict. Since the 2000s, tension has been rising again because of Shiite Islam in Iran, whereas the Iranian Kurds are mostly Sunni.

Iraqi Kurdistan

Iraqi Kurdistan is linked to the question of the Mosul villaet (see British Mandate). In 1925, the League of Nations decided to annex Mosul to the Iraqi mandate. The resurrectional movement never dried up in Iraq, which represents the specificity of Kurdish nationalism in the country. Nevertheless, the agreements with Iraq are a failure, especially with the fact that Iran no longer supports Kurdish nationalism. In 1991, when Saddam Hussein lost the war, the Kurds took the opportunity to establish de facto autonomy: the constitutionalisation of this autonomy took place as soon as Saddam Hussein's regime fell. However, since the American withdrawal in 2009, the Kurds have suffered pronounced marginalisation from central Iraq. Even more recently, the referendum in Iraqi Kurdistan in September 2017 was opposed by Baghdad.

Syrian Kurdistan

Dans les années 1960, le gouvernement nationaliste syrien aggrave la division entre les différentes communautés kurdes – faite selon le tracé d’une ligne de chemin de fer. Dans les années 2000, les premières manifestations pour une autonomie du Kurdistan syrien émergent : les Kurdes profiteront du chaos du pays pour en instaurer une de facto.

Depuis l’intervention anglo-américaine de 2003 sur le sol irakien, aggravé par la guerre civile qui s’ensuivit – y compris la crise syrienne depuis 2011 – l’espoir de créer des États-nations stables s’est retrouvé très fragilisé, voire inexistant, au Moyen-Orient. Paradoxalement, les frontières sont toujours là, témoins d’une histoire géopolitique très forte.

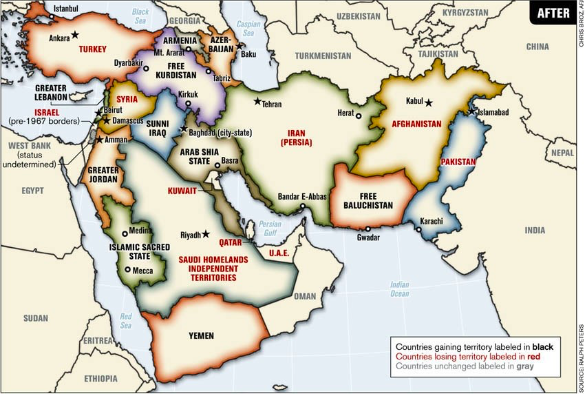

Ralph Peters estime que la réalité du terrain (différences politiques, culturelles, religieuses) remet en question les frontières qui ne répondent pas aux attentes des sociétés sur place: les pays se retrouvent modelés selon des critères nationaux, ethniques et religieux. Cette carte fit beaucoup débat, y compris au sein de l’OTAN.

Il y a un large consensus sur le fait que l’expérience nationale a échoué. Bien que Bachar Al-Assad soit en train de gagner la guerre, la nation syrienne n’existera plus de la même manière qu’avant le conflit (tout comme la manière de gouverner). De plus, les frontières ne démarquent pas les communautés: elles sont liées, si ce n’est pas territorialement, via la notion confessionnelle, par l’héritage historique, etc. Le concept de diaspora reprend tous ces éléments.

Le Golfe persique

Certains États préfèrent le nommer « Golfe arabe ». Le Golfe est aujourd’hui un symbole de prospérité et de luxe. Il comprend le Koweït, le Qatar, le Bahreïn, les Émirats arabes unis et Oman. Pour comprendre son évolution, il faut s’intéresser à la politique britannique dans la région.

Historiquement, le Golfe lié à la Mésopotamie avec le commerce des perles, dont certains centres sont établis au Bahreïn et à Oman. Les régions pauvres commerçaient des perles, de la pêche et du commerce maritime. La région connaît un certain essor avec les Abbassides, mais dès leur déclin, la situation redevient problématique. Ce vide est vite remplacé, car à partir du 15ème siècle, les puissances européennes investissent la région : le commerce des épices et le commerce maritime en général en sont les principaux vecteurs. Avec l’arrivée de la Grande-Bretagne, le commerce se renforce via l’intensification des échanges avec l’Inde.

La politique britannique est malmenée par les pirates et par les différents princes qui se font la guerre. Dès 1798, la menace devient aussi française. À partir de là, la Grande-Bretagne conclut des pactes spéciaux avec les acteurs locaux – le traité avec Oman pour empêcher l’expansionnisme français. Le même procédé sera appliqué dans les relations avec les pirates. Ces traités apparaissant au 19ème siècle vont déterminer la politique économique et stratégique britannique dans la mesure où leur renouvellement permet de sécuriser le Golfe : malgré que la région est instable, de plus en plus de corsaires et de princes s’engagent à ne plus se faire la guerre.

Certains États vont profiter du début de la Première Guerre mondiale pour renforcer leur position internationale: le Koweït signe un accord avec la Grande-Bretagne pour renforcer le protectorat. Après l’indépendance de l’Inde et du Pakistan, les Britanniques décident de se retirer de cette région-là, vers les années 1960. Tous les princes locaux, ayant fait des alliances avec les Britanniques vont se poser la question de l’avenir de la région: les créations des États que l’on connaît aujourd’hui se mettent en place à ce moment précis. Peu après, la découverte du pétrole change la donne et provoque un regain d’intérêt des Occidentaux sur le territoire: la deuxième vague d’indépendance aura lieu dans les années 1970.

L’islam politique

Il s’agit d’une idéologie, d’un programme politique, dont le but est la conquête du pouvoir afin d’islamiser la société selon la lecture de certaines sources et textes religieux qu’en font les acteurs de ladite idéologie.

Il fait son apparition dès l’échec du panarabisme (mouvement d’opposition à la domination occidentale…). La destruction d’Israël, symbole de la puissance étrangère, revient aussi dans cet imaginaire. Cette ère démarre selon les spécialistes en 1979, lors de la signature du traité de paix entre l’Égypte et Israël : la « trahison » égyptienne ne fait que renforcer les antagonismes envers l’État hébreu.

Plusieurs traits caractéristiques:

- Le fondamentalisme fait aussi partie de l’islam politique (et dans le monde musulman dès le 8ème siècle). Le wahhabisme (18ème siècle), fondamentalisme très rigoureux, révolutionnaire, joue un rôle très important.

- Le fondamentalisme est une volonté de faire fit de l’histoire pour retourner aux fondements de la religion.

- La colonisation, manifestation concrète de la domination européenne sur le monde arabe, fait partie intégrante de l’imaginaire politique.

- Les luttes d’indépendance en réaction à la pénétration occidentale: la tradition islamique en est fortement imprimée, la notion religieuse y contribuera beaucoup. L’idéologie de libération nationale.

L’origine de ce mouvement, dans notre siècle, peut émaner des Frères Musulmans (Égypte, 1928), dont le protagoniste est Hassan Al-Banna. Cette organisation va apparaître sur la scène politique pour appuyer l’islamisation de la société égyptienne. L’originalité du mouvement consiste dans le fait que cette organisation politique possède une force paramilitaire – présence de la tradition militaire et des Britanniques sur le territoire. Elle considère le Coran comme sa constitution. Le mouvement va avoir des bas et des hauts. Bien qu’il ne soit pas partisan d’une action armée, il participera tout de même à la guerre de 1948 (prétexte de trahison) tout comme à la révolution de 1952.

Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966), théoricien d’un potentiel État islamique, va jouer un rôle très important dans le rôle de l’islam politique: torturé, réprimé, car dissident, il émane la théorie selon laquelle de telles sociétés – occidentalisées, dirigées par le nationaliste panarabe – ne peuvent être construite sur la base de l’Islam. Elles sont tombées en « Jahiliya », légitimant ainsi le recours à la violence (contre un souverain musulman). Il sera condamné à mort et décidera de ne pas faire recours à la décision dans le but de réactiver l’imaginaire des martyrs.

Alors que sa pensée reste marginale, les choses changent en 1979. Le plan idéologique se retrouve bouleversé par l’échec panarabe, tout comme la symbolique, touchée par l’accord avec Israël. Ailleurs, la présence des forces soviétiques en Afghanistan débouchera sur une guerre s’étalant de 1979 à 1989, opposant l’URSS aux moudjahidines (« guerriers saints »). La notion de martyrs se voit généralisée dans la lutte contre les puissances, quelles qu’elles soient (occidentales, communistes…), contribuant au développement du mouvement. Certains États veulent réagir en promouvant des politiques islamistes, profitant du contexte pour asseoir leur monopole d’autorité (dans des régions instables).

Dans les années 1990, les spécialistes concluent de l’échec de l’islam politique, les mouvements islamistes n’ayant pas réussi à prendre le pouvoir. On se rend compte rapidement que a conclusion était trop hâtive: une fois la guerre gagnée contre les soviétiques qui quittent l’Afghanistan, le jihad va être lancé contre les États-Unis et leurs alliés croisés, Israël.

Les discours, approches et tactiques sont différents, car la violence est désormais sacrificielle. On dépasse le stade de martyr, cela prend une tout autre forme: l’apparition des attentats (-suicides), le recours au terrorisme. Les acteurs ont évolué: des élites activistes rejoignent Al-Qaïda. Aussi, on assiste à la relocalisation de ces acteurs, qui se fera principalement en Irak. La situation dans le pays est particulière, car la minorité chiite reprend le pouvoir dans un contexte de chaos total – le parti Baas est interdit depuis la chute du régime de Saddam Hussein. La population sunnite mise à l’écart du pouvoir, les chiites deviennent la première cible d’Al-Qaïda (Cf. Al-Tawihd de al Zarqaoui) en Irak. Dès 2014, la formation sera désignée sous le nom d’État Islamique.