Introduction to political behaviour

The study of political behaviour is not only the study of behaviour as such, but also political opinions, political attitudes, beliefs and values more broadly, all of which are part of political behaviour.

The word "behaviour" is a bit wrong. We have a field of study that is much broader than behaviour as such. This field also extends to opinions, beliefs and values without necessarily transforming them into behaviour. It is not only behaviour and action, but also attitudes, opinions, beliefs and values that are behind it.

We will become aware of the discipline and give some insight into what we are studying in political behaviour.

Two main areas of study

There are two main areas of study in political behaviour that can be summarized by saying that there is conventional political behaviour on the one hand and unconventional political behaviour on the other.

Conventional political behaviour

What is called conventional political behaviour, is also called electoral behaviour. The purpose is to study the behaviour of electors when there are elections. First, to study political participation, that is, who participates and who abstains for what reason; and second, who votes and how.

It is possible to simplify this field of political behaviour by saying that there are three fundamental questions, namely who votes, how and why. We observe who votes, what people vote, and then we try to explain why people vote and why they voted for this or that party.

As we are in Switzerland, it is necessary to broaden the notion of electoral behaviour a little, because, as its name suggests, electoral behaviour refers to elections, so we study electoral behaviour, who votes, who votes, for which party and for which candidate, but in Switzerland, there is an important direct democracy which means that we do not only vote for elections, but also on concrete objects, public policies, proposals, political reforms among others, and therefore, we can also apply the study of electoral behaviour to behaviour in popular voting, namely the study of behaviour in direct democracy votes. So, all the questions we ask ourselves about electoral behaviour can also be asked when we study voting behaviour in direct democracy votes, i. e. popular votes in Switzerland.

Non-conventional political behaviour

Non-conventional political behaviour makes it possible to invoke two types of collective action: protest politics and the new social movements that belong to this field.

Collective action is the field that encompasses the whole. Collective action refers to the collective mobilization to defend common interests. A group of citizens is mobilizing to defend common interests. This field of political behaviour studies how these behaviours are formed.

Within collective action, we can define a little more specifically what is called the protest policy. The protest policy is a set of actions by groups that wish to make a claim and therefore make demands to the government, parliament or other types of decision-makers. It is therefore a group that wishes to make a claim and therefore alert the authorities.

The protest policy can take different forms. It can take the form of social movements, but also of revolt, civil war, terrorism; all means aimed at bringing these demands to the attention of the general public and, if possible, at influencing policies.

A third level within political action and protest politics is the so-called new social movements. We say "new social movements" in distinction with "classical social movements" such as trade unions. These new social movements are, for example, the ecologist movement, the pacifist movement, the gay movement, these are movements that are created to defend the interests of a specific segment of the electorate or to defend a cause such as the environment in the case of the ecologist movement.

This mobilization through social movements takes unconventional forms and that is why it has been distinguished from conventional political behaviour. This is for example the demonstration, the strike, the boycott, therefore forms of collective action that differ from the institutional channels of voting, the collection of signatures to launch referendums or initiatives.

Institutional channels will lead to conventional political behaviour such as signing petitions, signatures in order to launch initiatives or referendums. This is distinguished from non-conventional behaviour such as strikes, demonstrations or boycotts.

Examples of questions that are asked

To know what we are studying, when we cover political behaviour in Switzerland and abroad, these are the kinds of questions we ask ourselves:

- To what extent does age influence participation in elections and polls? There is a whole stream of literature that focuses on political participation and the variable "age" is a key variable to explain participation. The effect of age is not only the effect of aging, but it is also the effect of the life course and it is also the generational effect, but also the fact of belonging to a specific generation. All this is combined, there is this age effect on political participation. Why do some people engage in social movements and others not? In other words, are there individual predispositions that make people more or less willing to engage in collective action and social movements?

- What are the main individual determinants of electoral behaviour? This question is how can we explain how which segment of the electorate votes more for such a party, are there regularities that can be identified to better understand why certain types of people according to their age or social class or political value tend to be more for one party than another?

- How can we explain the rise of populist right-wing parties in Europe? It is a very large field now in literature. We are trying to understand, to find regularities, kinds of rules that would make it possible to decipher the vote for these right-wing populist parties. This is, for example, to know how parties such as the SVP have been so successful and whether the explanations we have in Switzerland also apply to similar parties elsewhere in Europe, whether the same causes produce the same effects, whether there are regularities behind the rise of right-wing populist movements in Europe, which is an important issue addressed in political behaviour.

- To what extent does associative engagement influence the integration of foreigners? This is a research that Marco Giugni and Matteo Gianni are currently conducting to see if the involvement of foreigners residing in Switzerland in associations has an influence on the type and degree of integration of foreigners. The question is whether we can ensure an integration model through associative integration.

- What is the impact of citizenship models on the mobilization of immigrants in European countries? This is an international research, we would ask ourselves the question because there are different models of citizenship, some involve land rights, others blood rights, some are very liberal in integration, others are very restrictive, and we are trying to find out if this has consequences on the degree of mobilization of immigrants in these countries concerned.

- To what extent do election campaigns and the media influence the formation of opinions before an election or a vote? It is a dynamic perspective in which we are interested in the way in which citizens form their opinions before a vote or election and therefore in the way in which this formation of opinion is influenced by the environment and by the referendum election campaign. The idea is to know if opinions were formed in advance and we knew in advance what they were going to vote and the campaign didn't have much effect or, on the contrary, do campaigns have a massive role in opinion formation.

We will leave aside non-conventional political behaviour and focus on conventional political behaviour.

Three main models for explaining the vote

The literature in this field includes three classical grandes écoles d'explication du vote. These three schools date from the beginning of the 20th century or the first half of the 20th century, so they are already more than fifty years old, which is why we speak of a classic school of explanation of vote. However, there has been an evolution towards other models of explanation of vote. But it is important to start with these grandes écoles, which still have a great model for explaining the vote.

Political behaviour is a relatively young discipline. It is a relatively young discipline because it is linked to the availability of data. Opinion polls were born in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Until then, when we wanted to study political behaviour, we had to do so on the basis of aggregated data, i.e. the results of elections or votes per canton or municipality, for example. The distribution of results by commune was studied. But this is at the aggregate level, i. e. in general, for a community there were no survey data available for a very long time to study political behaviour at the individual level, i. e. each individual separately. This explains why this field of political behaviour is relatively recent and has developed since 1945 and 1950.

Socio-structural school

The first major school of explanation of vote is also called the Columbia School because it was developed at Columbia University by several researchers, including a famous researcher, Paul Lazarsfeld. Lazarsfeld conducted the first serious non-commercial scientific opinion survey in the United States. It should be noted that it did not do it for the whole country, in this case it focused on a county in the state of Ohio. It was a study limited in its geographical scope, namely only one county in an American state, but which was on the other hand very impressive in terms of its research design since Lazarsfeld conducted a panel survey in six waves. This means that he interviewed the same people six times in a few months or years. This is called a panel survey, also called a "longitudinal" survey. So, for the first time, there were data that no one had had before in studying voting behaviour and opinion formation at the individual level.

Lazarsfeld's study focused on the 1940 presidential elections. He tried to understand the reason for the vote, namely, why some voters voted Republican and why some voters voted Democratic. What interested him was the explanation after the vote, he had not been interested in predictions. Today, we are seeing more and more results of opinion polls, at least in the media to tell us what the outcome of the upcoming election will be, that is to say, that forecasts are made that are predictions. In this study, as in many other scientific studies, the purpose is not to make predictions, not to make predictions, but to try to understand afterwards why people voted this or that.

To go directly to the essence of its conclusions, the results of this study founded the sociostructural model, known as the Columbia model, which, as its name suggests, emphasizes the importance of sociostructural factors in explaining the vote. One of the key conclusions of this study is that "a person thinks, politically, as he or she is socially. Social characteristics determine political preferences. As the use of words indicates, this model of explanation of vote is very deterministic in nature, such as "tell me who you are and I will tell you how to vote". Under this model, individuals know well before the vote what they are going to vote. Moreover, almost by definition, this knowledge of what people will vote is stable over time because the integration of an individual into his or her social context is relatively stable and therefore so is his or her vote. There is a high stability of the vote due to the stability of the insertion.

In this model, the determinants of voting are socio-demographic or sociostructural characteristics such as socio-economic status, such as education level, income or social class; religion and place of residence.

Once we know these three characteristics and as long as they complement each other, we know for whom more or less Americans were going to vote at the time. In this model, the vote is highly predetermined, there is a very high predisposition of the vote according to the characteristics of the group to which an individual belongs. Thus, there is a pre-structuring of the vote according to the social and socio-economic characteristics of the group to which an individual belongs.

There is a link between this model of explanation of vote and the literature on cleavages. The idea is that if a cleavage is prominent, if an individual identifies himself in this cleavage as in a religious cleavage that would oppose Catholics and Protestants, then simply knowing the characteristics of the individual on this religious dimension makes it possible to know more or less correctly who the individual will vote.

In Switzerland, historically, in the Catholic cantons, there was a very strong opposition between individuals who practiced religion, and those who did not, namely the laity. Everyone was Catholic, almost everyone was a believer, but not everyone practiced diligently and the distinction was not practiced. This division was politically reflected in the opposition between the Christian Democratic Party and the Radical Liberal Party. Practitioners easily voted PDC and lay people easily voted radical liberal. It wasn't as caricatured as that, but barely. Voting could fairly easily be anticipated based on knowledge of religion and religious practice. In the non-Catholic cantons, the dividing line was different, it was between Catholics and Protestants. Catholics voted PDC and Protestants voted radical or perhaps socialist and more recently SVP.

Psychosociological school

The second major model that also followed the Columbia model over time is what has been called the Michigan model because it was developed within the framework of the University of Michigan, which conducted the first American opinion surveys at the national level. Lazarsfeld focused on a county that is Ohio, Michigan conducted the first presidential scientific opinion surveys at the national level. This then led to the American electoral studies project, which is still being piloted from the University of Michigan.

For the Michigan School, the key explanatory factors for understanding electoral behaviour are not the socio-geographical characteristics as claimed by the Columbia School, but what they call "psychobiological" factors. Unlike Columbia School, which focused on the individual inserted into its group, Michigan School focuses on the individual as such with his or her psychosociological orientations. More precisely, the key variable at the heart of the Michigan model is partisan identification, which is identifying with a party, feeling close to a political party.

Identification is a psychological emotional attachment to a party. In the theorization proposed by the Michigan School, we identify with a party very early in life, in adolescence through political socialization within the family. There is a very high intergenerational transmission that causes an adolescent to be influenced by his parents' preferences and in the case of political socialization within the family, he acquires this identification with a party that then only strengthens itself with age according to this model.

As in the first model, the emphasis is on stability of preferences, there is a kind of lasting loyalty to a party that will then influence the choice of that party when the electorate expresses itself.

In this model, the main determinant of voting is its loyalty to a party that is a lasting emotional trait. The idea is that this partisan identification works as a kind of cognitive shortcut. The world is a complex place, ordinary citizens cannot fully master the whole complexity of what are the right solutions to all the problems that exist, so they will rely on their partisan loyalty. They will use their partisan loyalty to simplify their representation of the world and guide their electoral choices, read will vote according to the party they feel close to and think it will be able to solve problems. In other words, the average citizen relies on shortcuts of information because we are not necessarily able to inform ourselves exhaustively, to master all the parameters of a problem well, so we try to rely on shortcuts of information, we also talk about euristics, which helps us to make a decision without necessarily entering into a complex and sophisticated information processing and decision-making mechanism. Identifying oneself with a party can be used to shorten information rather than to go and look for all the information oneself, to compare the parties' programmes, their ins and outs. This is the idea of an information shortcut that is also applied in other contexts.

In this model, this partisan identification is the key variable, there are others that are also integrated into the model, but play a much more secondary role. The Michigan model also refers to other types of political attitudes such as opinions on current political issues, but also sympathy for candidates. As much as party loyalty is a stable factor in the long term, so much so, it is well understood that attitudes about issues and sympathy for candidates are short-term factors that can also fluctuate during an election campaign itself. So, the basic idea of this model is that, in general, preferences are stable because identifying with a party is a stable factor, but it is recognized that sometimes, as an exception to the rule, there may be fluctuations in the electorate's own preferences because of preferences on issues or preferences on party candidates that may change over time in an election campaign. It is therefore the exception, the rule is stability because of stable party loyalty.

School of rational choice

The School of Rational Choice is linked to the University of Rochester because that is where Anthony Downs studied and taught. Downs is the author of reference for all the literature on rational choice, he is a little bit the founding father of the School of Rational Choice. His book An Economic Theory of Democracy published in 1957 remains a reference. This school has not only developed in the field of political behaviour, but also in other areas of politics.

We're changing our perspective. The Columbia School and Michigan School models assumed that there is a strong link between a voter's profile and his or her vote, whether it is the socio-demographic profile with the Columbia School or the psychosociological profile with the Michigan School. The two schools agree on the idea that if we know this profile, we know about who the person is voting for. In this case the profile explains the vote.

For the School of Rational Choice, the analytical cursor is shifted a little and the emphasis is on individual decision-making mechanisms. This model is less deterministic than the others, we cannot know in advance how an individual will vote, we must look at the mechanisms that lead to decision-making to understand this person has voted. The mechanisms on which the School of Rational Choice emphasizes are cost-benefit calculations, a so-called "utilitarian" approach to voting. It is believed that individuals decide on the basis of a cost-benefit calculation.

What are the benefits, what are the costs associated with a voting decision? What is the benefit of voting for this party or what is the loss of voting for this party? The voting determinants in this model are based on a utility calculation. This is the same logic of homoeconomicus applied to homopoliticus. It is assumed here that the homopoliticus behaves like a rational being who will try to make cost-benefit calculations and vote according to these cost-benefit calculations. It will therefore seek to maximize its usefulness.

There are three strong assumptions in this model: voters are aware of their preferences and make an effort to gather the necessary information to be able to make cost-benefit calculations. So they will seek information in order to make a rational choice.

- voters are able to identify exactly the costs and benefits associated with a voting decision and then are able to vote rationally and therefore choose the party that effectively maximizes their utility.

- voters are not influenced by their environment. Voters are at the heart of their own decision, they will seek information, compare and weigh costs and benefits and make their choice. They are not influenced by party propaganda, they are not influenced by the context in which they live, they are not influenced by their families, etc.

Deficiencies of traditional models

These three models have many weaknesses and defects. There has been a huge literature to criticize, amend and correct them. If we talk about political behaviour, we have to start from these three models because they are the basis from which we can start thinking a little more seriously and with slightly more recent models.

What are the shortcomings of these classic models? There are several of them and we will focus on the main ones.

Empirically, the studies that were done in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s did not really confirm this strong weight of sociological and psychosociological factors. The theses of the Columbia School and the Michigan School that one could really explain the vote if one knew the social characteristics and partisan preferences of individuals, studies have not confirmed this. The explanatory power of these models is low. It is possible to explain something, but not much.

Why these models were not so efficient and, why they tended to lose performance over the years and decades, is because these explanatory factors at the heart of the models have declined over time. There has been a historical decline in the factors that explain the vote, such as social class or religion, or the fact of identifying with a party as postulated in the Michigan model.

Why was there this decline? This is because there have been changes in society that have led to this decline, such as changes in social structure. Society has changed significantly from a primary society in which the primary sector was highly developed to a society in which the secondary sector and especially the tertiary sector has been highly developed and this change in the social fabric has had major consequences from a political point of view. The tertiarization of the economy had major consequences on voting. The primary sector has shrunk, the secondary sector has shrunk and the historical links between the primary class or the working class, and a or other party generally on the left, these links have been greatly weakened. The same applies to geographical mobility, there have been great geographical mobility, which has led to much greater social mixes, much greater cultural mixes, which has also weakened traditional links between groups and parties. Overall, there has been a decline in class and religious loyalties and a decline in partisan identification.

The second factor that has contributed to the decline in the heavy explanatory factors is the development of education. It is what is sometimes called revocation, which is the fact that the level of education is greatly increased in Western societies, leading to an increase in the independence of minds, in the decision-making autonomy of voters and has made them less captive, less prisoner of their traditional allegiances. As education levels increase, people can afford to form opinions more independently and autonomously, they are less influenced by organizations, groups or parties. There is an electorate that is more independent, but we also have an electorate that is more volatile. Where previously, when the major models of explanation of vote explained voting with fairly stable behaviour from one election to another with citizens who are more independent, more autonomous, more critical, we have greater volatility, greater instability in electoral behaviour at the individual level. It is easier than before to change parties from one election to another.

The third essential factor is the rise of audiovisual media, first with television, but now also with electronic media, this rise of audiovisual and electronic media has also radically changed the situation with regard to election campaigns and voting campaigns. Once again, the result is individuals who are less captive, less influenced by organizations such as political parties and more influenced by the media and everything that is done in the media, by media coverage or advertising and who influence electoral behaviour much more than before. Overall, there is less party influence in political communication and more media and campaign influence with short-term effects. Where traditional models, particularly the Columbia and Michigan models, emphasized the stability and importance of long-term explanatory factors such as social inclusion or party identification, we now know that short-term factors are much more important than before. This does not mean that there is no longer any importance of long-term factors, but in the short term, clearly, there is a relative increase in importance.

Another shortcoming of these classic models of explanation of vote is that they were all more or less explicitly based on a simplistic conception of the electorate. Simplistic because it was homogeneous, i.e. these models took into account individual differences, but above all socio-demographic and possibly psychosociological differences, but did not take into account the fact that individuals differ from each other in their relationship to politics. Individuals and citizens differ from each other in their relationship to politics and in particular in their interest in politics and political competence. Not all citizens are equally interested in politics, some are very interested and even a lot of people who are involved in politics are making a career out of it, while others are not interested at all in politics. On the other hand, some citizens have a very good political knowledge, understand the issues and master, inform themselves, while others do not have the cognitive skills and motivations necessary to inform themselves and therefore do not have the knowledge necessary for informed participation and voting. So, interest in politics determines the degree of attention to politics and it also determines political participation, namely if you are interested, you are very likely to participate, if you are not interested you are very likely to abstain. Motivation and interest in politics also determine the attention given to politics and the political message. Political competence, on the other hand, determines the ability to integrate messages delivered in the public space. There can be a wonderful information campaign with positions on the right and positions on the left, rich debates and if at the individual level, people do not have the necessary skills to understand, internalize and assimilate these communications, it will not influence their opinion and contribute to the formation of their opinion. Somewhat more competent people will take this into account and weigh the pros and cons trying to get an idea based on the information provided in the public space.

The point here is that interest in politics and competence in politics, in other words, a motivational factor and a cognitive factor, namely an interest factor and a competence factor, both of which will condition and play an important role in the process of forming people's opinions. We are now trying to take into account the heterogeneity of the electorate, we are no longer betting on a homogeneous electorate, we are increasingly trying to take into account the diversity and heterogeneity of the electorate.

The last gap in classical models and especially for the school of rational choice, there is a huge focus on individuals. The school of rational choice is the paradigmatic case of a focus on the individual since for the school of rational choice, the individual makes his cost-benefit calculation independently of the context and independently of any form of external influence, it is he who is at the centre, to be informed, or even which party pays him the most, which one costs him the most and according to that make his choice as, for example, know which party is closer to him on a left-right scale, and we will vote for the party that is close to us according to our interests, but regardless of the context. The criticism made here is an excessive focus on voters and their characteristics and an insufficient consideration of the context in which individuals form their opinions.

This criticism applies mainly to the school of rational choice, but it also applies to Columbia School and Michigan School. The Columbia School provides that an individual votes according to the characteristics of the group to which he belongs, but even for this school, the group is not taken into account, it is only taken into account through the individual characteristics of the voter, namely whether he is a worker, whether he is Catholic or not. The inclusion of this voter is not taken into account or, for example, the role of trade unions in articulating workers. Even this model, which is a sociological model that places the individual at the heart of the group, even this Columbia model did not seriously take into account the role of the group. What is taken into account is the social characteristics of the individual and not the group in reality. However, individual opinions are not formed in a political vacuum, but in a specific institutional and political context. This specific political institutional context is likely to influence the way in which individuals form their opinions.

There are two elements of the context that should be mentioned here that are:

- political offer: we speak of a political offer to designate partisan competition. It is therefore a characteristic of the parties that run for office, of the differences between parties, of the characteristics of the parties, of the characteristics of the candidates; it is called the political offer. Political demand would be the characteristics of individuals, the characteristics of voters are the characteristics of demand. The individual asks by voting in response to an offer made to him by political parties by presenting lists and candidates. The idea is that supply matters as much as demand. As traditional voting schools suggest, we must not focus on demand, we must also take supply into account because supply will have an influence on demand, on the meeting between demand and supply.

- election campaign: there is a growing conviction, and studies show it, that the short-term factors that are conveyed in an election campaign influence voting, partisan choice and the choice of candidates. We are far from the traditional schools that assumed stable ties with individuals who vote for the same party from one election to the next. On the contrary, recent studies show that traditional allegiances, traditional loyalties to parties are declining and weakening, while short-term factors such as the role of election campaigns are becoming more and more important.

Electoral research: recent developments

In electoral research, we have tried to correct the shortcomings, to remedy the shortcomings of traditional models without necessarily abandoning them completely, we continue to take into account the role of social class, religion or other individual factors on voting, but we try to add other explanations.

Taking into account the context

First, we take into account the context that will become more systematic and rigorously taken into account. First, there is the institutional context, such as the electoral system, which influences the voting behaviour of voters, but also the upstream behaviour of parties when they present lists. Recent literature in electoral research attempts to take into account the role of the electoral system, such as the degree of proportionality of the system. We know that if the system is more or less proportional, there will be upstream consequences on how individuals develop their voting strategies.

The degree of polarization of the party system is to what extent we have parties that make proposals that differ from each other and the more polarized a system will be, the more different the proposals they will make because the more polarized the system is, the more the parties oppose each other on certain issues and therefore its likely to propose different solutions to the problems that arise. So, the more polarized a system is, the more varied and richer the offer will be for voters. On the other hand, the more consensual a system is, the less difference there will be between parties, the more difficult it will be for voters to differentiate between parties. Similarly, in addition to polarization, the degree of fragmentation of the party system is also taken into account, i.e. how many parties are presented. The election campaign and the media are also taken into account, trying to see how political communication and media coverage influence opinion formation.

Taking into account the heterogeneity of the electorate

The second innovation is that we are trying to take into account the heterogeneity of the electorate. We assume that the electorate is no longer homogeneous as with traditional schools, but that it is on the contrary a heterogeneous electorate that differentiates itself, that is diverse and varied with interested persons and others not, competent persons and others not, and we try to model and see how these differences of interest in politics or these differences of political competence affect the opinion-forming processes and the electoral choice processes.

It is a trend that is part of the political psychology that is booming in the United States and Europe. Political psychology places more emphasis on the psychological mechanisms behind opinion formation and choice.

Now, we assume that the stake vote is much more important than before. The issue vote is not the main ideologies, but what are the important issues of the day, what are the preferences of voters on these issues and which parties are perceived to be the most competent to solve these problems from the voters' point of view. This is now a powerful factor in partisan choice. With Switzerland, we can very well show that the SVP vote is partly a vote of stake because of the immigration issue that is imposed on Switzerland and because of the SVP's reputation, reputation for competence or at least reputation for dealing with this immigration issue. Many voters certainly gave their votes to the SVP because it was the party that had the best solutions for the most important issue of the day in the eyes of voters. These are short-term mechanisms that tend to become important in electoral behaviour.

Methodological innovations

The latest innovation is that the complexity of the models has been made possible by methodological innovations and in particular the use of hierarchical models or multi-level explanatory models. In statistics, models are developed that take into account both the characteristics of individuals and the context in which they vote. In other words, individual and contextual factors are simultaneously taken into account in the explanation of the vote and the interactions between individual and contextual factors are also taken into account. It is this complexity with the simultaneous consideration of contextual and individual, but more jointly, factors, i.e. the consideration of interactions between contextual and individual factors and this is the best way to explain an electoral choice. For example, we try to show that being Catholic does not have the same impact if we live in a Catholic canton or a religiously mixed canton. So there is an interaction where being Catholic will be a more or less powerful factor in the vote depending on the context, i.e. between Catholic cantons and religiously mixed cantons. The idea is therefore to take into account both individual and contextual factors.

Examples

Example 1: Explanation of the USC vote

This study analyses the composition of the UDC electorate and the evolution of this composition over time.

The graph on the left shows the composition of the Socialist Party's electorate in 2007, results from an opinion survey after the 2007 federal elections. We mentioned the SELECT studies that have been conducted since 1995 after each federal election, where a Swiss opinion survey is conducted to assess individual behaviour.

In 2007, the Socialist Party had achieved about 20%, which also represents the average score of the Socialist Party. For different socio-professional categories, there is also a difference less or more than this average, which gives an idea of which segments of the population are most likely to vote for the Socialist Party and which segments of the population are least likely to vote for the Socialist Party.

Starting with the last line, we see that there is a socio-professional category that votes massively for the PS, which is what we call socio-cultural specialists; while the PS has averaged 20%, it has done 34%, or more than fourteen percentage points among socio-cultural specialists. The socio-cultural specialists who are sometimes called the new middle class are the employees who are active in the field of health, social, education, culture, but also in the media, thus a slightly superior middle class, but not too many, which has grown in number, what could be called, in a rather trivial way, the "bobo", namely the "bohemian bourgeois". These are people who, on the one hand, are relatively wealthy in terms of resources, but who, on the other hand, are close in terms of values to the redistributive values of the left. These are people who, if they would vote selfishly as postulated by the rational choice model, would actually go from side to side because their socio-economic situation would in principle lead them to support Liberal programs. However, these people easily vote on the left because they are in solidarity with society in general and they are also attracted by the other programmatic values of the left, such as international openness and solidarity.

We see that all other categories are below the average score of the socialists, including those called here "production workers", "service workers" and office workers". These are the people who were called workers at the time. Production workers are people who are active in the typically industrial field with repetitive tasks that have little autonomy in their work. These people vote less socialist than the average.

With regard to the SVP, for the 2007 elections, the SVP made 28% in 2007 with wide variations from one socio-professional category to another. For the SVP in 2007, one could say that the Columbia model still says things: the integration of individuals into society, their social class continues to say things about voting.

Who votes UDC? The little freelancers. Where the SVP made 28%, it made 44% among the small self-employed. Almost one in two small independents voted SVP. They are farmers, traders, craftsmen or self-employed people who do not run a large company. This is known in the jargon as the "old middle class". It is one of the two bastions of the SVP. The second stronghold of the SVP is the production and service workers. Where the SVP made 28%, it made about 40% among workers. This is something a little more surprising given that the SVP is a right-wing party from an economic point of view and therefore not a party that defends the interests of workers. What makes a higher than average proportion of workers vote for the SVP? Perhaps it is not because the SVP defends workers better than the Left, because there it would be possible to discuss, because trade unionists would say that the SVP does nothing to defend workers' interests, it is not the SVP that protects workers against foreign labour, or indirectly by closing borders so that there is no more competition. If the SVP is so successful with workers, it is not for the economic values or the economic programme that the SVP defends, but for the cultural programme that the SVP defends, i.e. for the desire to close borders in cultural terms, namely the defence of traditions by international closure not so much driven by economic considerations, but by cultural and identity but also historical considerations. In the two-dimensional space, we find here the result that if the SVP is progressing, it is largely due to its program on the openness - tradition axis and not for its program on the economic axis. From this point of view, it is not so different from the PLR, it is the famous win-lose divide. To put it simply, one could say that those who feel they are winners, in their perceptions, are sociocultural specialists, while the losers are those who fear international openness and who are afraid of this competition, which is not only economic, but also cultural and identity-based. These groups are the small self-employed on the one hand and services and production on the other. On the other hand, it is a bit of a mirror effect compared to the PS, the SVP also scores much worse among ethnic and socio-cultural specialists.

We are talking about class cleavage here, but we are saying that class cleavage still plays a role in electoral behaviour in Switzerland, but this role has changed. The class divide, traditionally, pitted workers against employers. This was the reformulation of Marx's theses on the conflict between labour and capital and for a very long time, in European states, there were marked differences in voting between workers on the one hand and employers on the left, with workers voting on the left and employers voting on the right. In Switzerland, as in other countries, there has been a reformulation of the class divide with a new class divide. There was a phenomenon of misalignment and realignment of voters with respect to parties. More concretely, voters in popular circles tended to slide from the left to the populist right. This has been observed in Switzerland, but also in other countries such as France or Austria, the Netherlands or the Scandinavian countries. In all these countries, we can show that there was this shift movement during the 1980s and 1990s by workers who voted for the left and who now tend to vote more towards the right population. Not all of them do, but a good number of them. On the left, however, there has been a strengthening of socio-cultural specialists as a bastion of the left. This is a powerful result that applies in Switzerland as in other countries.

This graph shows the same thing. In 1995, between 15% and 20% of service, production and office workers voted for the SVP, and we can see how this has changed over the past ten years with the scores we have achieved with workers who vote from 35% to 40% for the SVP. Of course, the SVP has progressed everywhere over the past twenty years, but it has especially progressed among the popular electorate, hence this reformulation of the class divide.

The class divide still matters, but it has changed in nature. It has been reformulated due to changes, misalignments and realignments between social classes and parties. When we talk about misalignment, it is for example the fact that the workers have gradually distanced themselves from the Socialist Party or the left in general in order to vote SVP, which is therefore a realignment. With this process of moving partisan allegiances across social classes, the content of the class divide has changed. We are now talking about the "new class divide" that would oppose on the one hand the winners of globalization such as managers and the new middle class, and on the other hand the losers of globalization or at least those who see themselves as losers or who are afraid of being losers, namely the working classes and the former middle class of the small self-employed such as artisans, farmers or traders.

The table above illustrates the evolution of the middle classes for the SVP. Three segments of the working classes with the grey office employee segment, the dotted line service employee segment and the black production worker segment. In all three cases, there was a very sharp increase in the proportion of workers who voted SVP. Of course, the SVP has made progress in all segments of the population, but especially among the working classes.

This graph is a simple arrangement of voters on a two-dimensional space.

On the horizontal axis, there is a dimension that could be called "for more government or for more market". This dimension is constructed with two questions asked in the opinion surveys with a question concerning social spending, namely whether the respondents are in favour of increasing or decreasing the Confederation's social spending, and the other question is whether the respondents are in favour of increasing the taxation of high incomes or on the contrary are in favour of reducing the taxation of high incomes. In both cases, depending on whether the answer is "yes" or "no", "favourable to spending", "unfavourable to spending", "favourable to raising taxes" or "unfavourable to raising taxes", this can be interpreted as left-wing or right-wing values on the economic axis of "more redistribution" with social spending and tax increases, and "less social redistribution" with reduced spending and taxes.

The vertical axis represents a first question that is "do you support" Switzerland's accession to the European Union or, on the contrary, "do you support a Switzerland that is going it alone? The second question is whether we are in favour of a Swiss who gives the same opportunities to Swiss or foreigners or, on the contrary, whether we are in favour of a Switzerland who favours Swiss over foreigners.

Then, the position of each voter on these two dimensions is calculated. In this graph, the average position of the sub-segments of the electorate of each party is calculated. For example, we can observe the average position of persons who belong to the class or class of socio-cultural specialists and who are PS voters compared to voters who are also socio-cultural specialists, but who on the other hand voted SVP. In the middle is the average position by socio-professional category. If we take the average position, they're all a little bit towards the center and there's not much difference. This is because among managers, for example, there are some who are very right, others less right, others up and others down, and when you take the average, it puts them quite centrally.

First of all, we can see that the SVP electorate is relatively homogeneous where all the sub-segments that make up the SVP electorate are quite close to each other, they are all relatively close to the "defence of traditions" pole, and a little to the right from an economic point of view, but in fact relatively centrist. In comparison, the SP electorate is much more fragmented. On the other hand, it is clear here that it is possible to be a production worker and have very different values. The production workers who voted SVP are very much in favour of closure and traditions and are rather right-wing economically. The workers who voted PS are neutral on the openness dimension, but they are more favourable on a redistributive policy.

The distance that there is between sociocultural socialists and workers socialist voters of production, on the vertical dimension, openness - closure, there is a world difference between socialist sociocultural voters and socialist workers voters. This is a bit of a problem for the SP at the moment because the SP, in Switzerland at least, is somewhat kept at a large distance between its popular electorate and the "new middle class" electorate of sociocultural specialists. Some, the workers, would like more authoritarian policies, less international openness, more security, fewer immigrants, fewer asylum seekers, while the socio-cultural ones are much more open, supportive and in favour of a generous policy towards a foreign policy. This is the great dilemma of the SP, because if the SP seeks to seduce its new electorate of the new middle class, it risks alienating its popular electorate. If the DP hardens its positions and becomes a little more firm on international issues, compared to others, immigrants and asylum seekers, then it will probably please its popular electorate and displease its sociocultural specialist electorate.

There is a real dilemma for the SP, which is a dilemma that the SVP does not have because its electorate is relatively homogeneous. It can be seen that the SVP electorate is mainly characterised by values of closure and the defence of Switzerland's traditions of sovereignty. The "business body" of the SVP is not so much its economic profile, it is independence, sovereignty, neutrality, the tightening of migration and asylum policies. All his electorate likes it, whether they are workers or not.

As we can see, on the horizontal dimension, the SP does not have too many concerns because the whole of its electorate is relatively homogeneous on this dimension, they are all aligned on -1 and -1.5 being all grouped almost vertically, which means that on redistribution issues, the PS electorate is homogeneous. Workers because they are in favour of a redistributive policy that serves their interests and socio-cultural specialists because they are ready to make an effort of solidarity with the less favoured classes.

To summarize this example, first of all, the class divide has changed in meaning, but it remains important as an explanatory factor of electoral behaviour. It is no longer the same class divide, but if we take into account these changes within the divide, these realignments, the class divide continues to explain electoral behaviour quite strongly. On the other hand, socio-cultural specialists, namely the so-called wage middle class or the new middle class of employees in the social, health, education, culture and media sectors, these socio-cultural specialists have become the new bastion of the left. In addition, the working classes and the former middle class, the small self-employed such as craftsmen, traders and farmers, have become the bastion of the SVP, which is the strongest voting class for the SVP. There is therefore a widening gap between the winners or supposed winners and the losers or supposed losers of globalization. From a normative point of view, this cleavage is expressed by the conflict on the vertical axis between open and tradition, which others call integration - demarcation, sometimes called libertarian - authoritarian.

Example 2: Explaining the success of the SVP

There is an alternative explanation to the SVP vote, which no longer refers specifically to the class position and the vote that goes with the class position, but is based more on what is called the stake vote. The stake vote is the idea that electoral behaviour is increasingly influenced by the major political issues of the day, regardless of the class to which one belongs. We take individuals from all social categories and try to see what their preferences are on the issues, what issues voters consider important, what their preferences and positions are on these issues and can we, on this basis, try to define for which party an electorate voted. Depending on voters' preferences on the issues, the question is whether it is possible to predict or understand why voters vote for a particular party.

By "stake", we mean the major political problems of the moment such as the migration crisis, ecology, nuclear energy or unemployment. These are concrete issues that arise every day and that citizens are aware of, leading them to vote for one party or another according to the proposals made by these parties. The idea here is to say that we must move away from these structural explanations of the "social class" type to move more towards short-term situational explanations being factors that are likely to influence and modify electoral behaviour in the short term. We can imagine that an election campaign succeeds in putting a new issue at the centre of the political agenda and that the party or parties that position themselves on this issue benefit from it in the election.

We are moving away from allegiances, lasting and stable loyalties between individuals and parties in order to better understand what is going on and what are the factors that would change partisan preferences and therefore the electoral choices of voters in the short term.

The stake vote

There are two main types of explanations related to the issues.

The first explanation is directly derived from a rational choice model with the voter voting rationally making a cost-benefit calculation. The idea is that voters will vote for the party that is closest to them on the issue. The parties that have the most similar preferences with voters are those for which voters will vote. If, for example, we are in favour of reducing immigration, we will vote for a party that supports immigration restrictions. It is possible to calculate distance models that ask respondents to position themselves on scales and parties to position themselves on the same scales, and then it is possible to calculate the probability that an elector will vote for which party based on their distance.

The general idea is that of the proximity model with a whole series of large types. With the proximity model, we try to explain electoral behaviour according to the distance or proximity existing between voters and parties on important issues.

The second idea that is very close is that the elector will vote for the party that has the most important issue, that is, the party that is deemed most active and competent on the issue in question. There is an issue vote related to a specific issue. It is not the position of voters and parties on different issues, it is what is the main issue currently at stake in the country, what is the party that has this issue and has developed over the years a reputation as a party that deals with the issue, that is able to manage and find solutions to this issue; if the issue becomes prominent among the population, this party will benefit from it in the election. This is the trend we call "issue ownership", on the party side, we try to develop reputations of skills on issues. For the Greens, it will be to develop their reputation for competence in environmental issues, for the Socialists, it will be their competence in social policy and redistribution, for the PLR, it will be to boost competence in economic policy, for the SVP, it will be to develop competence in immigration, security and European policy. This is quite stable because it is not easy for a party to change its reputation for competence, it takes months and years. To some extent, this issue is becoming important, so the party that owns it can win a lot of votes. For example, the victory of the SVP on 18 October 2015 is considered to be very much linked to the migratory and humanitarian crisis linked to the refugee movement, particularly in Syria, and the SVP, without doing much, if anything, about it has been in the news. The current situation has made this the issue that was raised in the media throughout the election campaign without the SVP having to campaign. Since the SVP is known as the party competent to have simple, even simplistic solutions to the issue, voters rely on it and then vote.

This diagram is taken from a post-election survey conducted after the 2007 federal elections. This is done quite systematically in these surveys, first of all a first question is asked, which is an open-ended question that consists in telling the respondent that there are different problems facing Switzerland at the moment and therefore we ask the respondent what is the most important problem today. It is an open-ended question and then the answers are grouped according to different categories. Once we have asked this first question, we ask a second follow-up question, which is "in your opinion, which party is the most competent to solve problem X? ». Separately, elsewhere in the questionnaire, this person was asked which party he/she voted for in the elections. These are three pieces of information that can then be put together.

This diagram is the entirety of the respondents who were interviewed in 1716 people. There were 1716 people who participated in the elections and chose a party. On the first line, there is the distribution for the first question mentioned which is an open question. For 35% of respondents, the most important issue was immigration, security and integration of refugees, for 16% it was the environment and for 31%, a broad category, the concern was related to the economy and the social state. If we add it up, we do not reach 100% for the simple reason that there are still other issues that are not taken into account here.

The second line aims to answer the question of which party is the most competent to solve this problem. These are always net percentages, i.e. the people who responded. Of the 35% who answered "immigration", 27% answered "immigration", a good part answered either SVP or PS. That is, 75% of those who cited "immigration" as a problem believe that the SVP is the most competent. Then, on the last line, we looked at what these people voted for. 17% of the 1716 people said they voted SVP, being the most competent party on immigration which is the main problem for them. This does not mean that 17% of voters voted SVP because immigration is the most important issue and the party is the most competent. We do not go so far as to establish a causal and correlative relationship. In any case, it is an indication of the importance of the "immigration" issue and the SVP's competence on this issue for the SVP vote. This does not mean that all these people voted SVP for that reason, but there is probably something going in that direction.

The rise of the SVP has been the spectacular factor in Swiss politics for twenty years now, and so there has been a lot of work done on this topic.

Electoral potential and exploitation of the potential

To explain the SVP vote, we began by saying that there is an explanation related to the socio-professional position, which is the class position that can already partly explain why we vote SVP rather than another party. We have seen that there is the question of the stakes, particularly with immigration, which plays a structural role in Swiss politics and which makes it easier for the SVP to vote. A third type of explanation refers to the party's strategies and the effects of these strategies in terms of mobilization.

The explanation we will put forward is that the SVP owes its success to its formidable capacity to mobilize its electorate. We are not going to study here how the SVP mobilizes. We will already show that we can see the effects of these mobilization strategies, they are tangible in the surveys. We do not analyse SVP strategies or political communication, we analyse the result of this communication and these messages. To do this, the standard and most obvious question when measuring electoral choices in a survey is "for which party did you vote". This is the key question, because without this information, there is almost nothing we can do. An attempt has been made to develop other measures and indicators that also provide information on party preferences without being limited to electoral choice.

The problem with electoral choice is that once a person has said they have voted SVP, we have no knowledge of that person's preferences over other parties. The person may have voted SVP, but he or she could also have voted PLR. Or a person voted for the Vers, but he could very well have voted for the Socialist Party, and once the person said he voted for the Greens, all the information is lost for the rest.

What we are doing is trying to implement measures that ask the question about all parties. This measure is called the voting probability measure. In the survey, we propose a scale from 0 to 10 and what are the chances that one day we will vote for a particular party. The same question is proposed for the main political parties in order to have a comparative view because we have information not only for the party we have chosen, but also for the others we have not chosen. This allows comparisons between parties to be made much more accurately than the raw question of "electoral choice".

Once all persons in the survey have been asked how likely they are to vote one day for the main parties in the canton, for example, it is possible to calculate on this basis the average probability of voting for a party. It is not complicated, it consists of summing and averaging the probabilities. The scores of each respondent are summed and divided by the number of respondents. This average probability of voting for a party with electoral potential. It is a measure of the electoral potential of each party. It is possible to do this for each party separately.

Afterwards, on this basis, it is possible to calculate the concretisation rate or the exploitation rate of the potential. A simple ratio is calculated, i.e. a division between the effective electoral strength of the party, i.e. what percentage of votes the party obtained, divided by its potential derived not from the votes cast, but from the survey, which is the average probability of voting for that party. This obtained rate is a measure of the parties' ability to convert potential into effective support.

Potentiel électoral des partis (probabilité moyenne de vote)

Commençons par le potentiel électoral mesuré dans les enquêtes, autrement dit la probabilité moyenne de voter pour l’un ou l’autre parti.

Ce graphique montre, pour des enquêtes qui ont été faites après les élections fédérales de 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007 et 2011, la probabilité moyenne de voter pour chacun des partis. Autrement dit, cela montre le potentiel électoral de chacun des partis. Pour tous les partis, le potentiel est bien plus élevé que leur force électorale réelle.

Si on prend le cas des Verts, ils ont un potentiel de 44%, autrement dit, en moyenne, sur l’ensemble de l’échantillon, la probabilité que quelqu’un vote Vert est 4,4/10. Traduit en termes de pourcentage, cela est 44%. Or, les Verts sont actuellement, fin 2015, à 7%, 8%. C’est l’exemple extrême de différence entre le potentiel et la force électorale effective. Il faut noter au passage qu’il y a cette telle différence entre le potentiel et le vote Vert est expliquée par deux raisons. La première est qu’il y a tout l’électorat qui répond dans ce graphique et y compris les gens qui n’ont pas voté, or parmi les gens qui n’ont pas voté, il y a beaucoup de jeunes qui aiment bien les Verts. La popularité des Verts auprès des jeunes augmente le potentiel des Verts, mais ne se traduit pas en termes de suffrages parce que les jeunes ne votent pas ou ne votent peu. La deuxième explication est la concurrence entre les Verts et le Parti socialiste. Les Verts et le PS se partagent en bonne partie le même électorat potentiel, mais au final on vote beaucoup plus souvent PS que Verts.

Le premier point est que le vote potentiel est beaucoup plus élevé que le vote effectif. Ceci dit, il y a une très grande relation entre les deux, il y a une corrélation de 0,8 voire 0,9 entre le potentiel et le vote au niveau individuel donc cela est très lié. Le deuxième point est que ce potentiel fluctue légèrement d’une enquête à l’autre, mais pas massivement, il y a quelques fluctuations, mais dans l’ensemble cela est relativement stable. Il y a eu une perte de potentiel pour les socialistes, mais ils ont un peu récupéré en 2011. Les deux partis de gauche ont, d’après ces mesures, le potentiel le plus élevé.

Le point principal que l’on peut dériver de ce graphique est le suivant et concerne la courbe de l’UDC. Comme on peut l’observer, ce potentiel est stable et est assez bas. Il n’a jamais dépassé 40%. Le potentiel électoral de l’UDC est relativement stable et relativement bas, c’est le plus bas de tous les partis considérés ici y compris les nouveaux partis comme le BBD et les Verts libéraux. Ce que l’on peut déjà dire ici est que le succès de l’UDC n’est pas dû à une augmentation de son potentiel, celui-ci est resté constant voire à même diminué en 2011 par rapport à 2007. Ce qu’il faut retenir est que le potentiel UDC n’augmente pas et il est relativement bas. Cela est quand même spectaculaire si on met cela en lien avec la courbe électorale de l’UDC qui affiche une pente positive impressionnante.

Taux de concrétisation/exploitation

Ce graphique illustre le taux de concrétisation du potentiel. Autrement dit, c’est le ratio entre la force électorale et le potentiel du parti.

Ce que l’on voit ici est l’extrêmement forte augmentation du taux de concrétisation de l’UDC. En 1995, en 1999, en 2003, même en 2011 l’UDC a pu augmenter quasi systématiquement son taux de concrétisation. Autrement dit, l’UDC a pu augmenter quasi systématiquement sa capacité à mobiliser son électorat potentiel. C’est la grande explication du succès de l’UDC. Ce n’est pas une augmentation de sa popularité au sein de l’électorat, l’UDC reste à peu près aussi populaire qu’il y a vingt ans, c’est-à-dire pas très populaire, mais par contre, les gens qui s’imaginent voter UDC votent effectivement UDC beaucoup plus fortement que les autres partis. Le taux de concrétisation des autres partis dépasse à peine 40% et même moins de 20% pour les Vers ce qui est un très fort contraste avec ce que l’on observe pour l’UDC.

Donc, la montée en puissance de l’UDC au cours de vingt dernières années est essentiellement due à sa capacité croissante à mobiliser son électorat qui pourtant est resté relativement stable en termes de potentiel. C’est l’idée que l’UDC est le type de parti qui provoque des réactions très vives, soit on est « ami » soit on est « ennemi ». Si on est « ami », on vote pour le parti, si on est « ennemi » on ne votera jamais pour le parti. La capacité de l’UDC est d’avoir convaincu de plus en plus d’amis de voter. Il n’a pas plus d’amis qu’avant, mais ses amis votent plus fréquemment pour lui ou de plus en plus en grand nombre pour lui.

Ouverture comparative

La montée en puissance des partis populistes est un phénomène qui vaut dans beaucoup de pays européens.

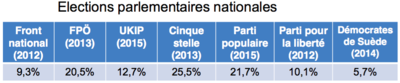

Ce tableau cherche à montrer les analogies qu’il y a entre les familles de parti. Comme on peut le voir, si on prend des chiffres tirés au parlement européen en 2014, il y a plusieurs partis y compris dans des pays autres que la Suisse qui ont dépassé 20%. Le FN a fait 25%, le Parti de la liberté autrichien à fait 20%, le UKIP au Royaume-Uni a fait 28%, le Cinque Stelle en Italie à fait 21%, le Parti populaire au Danemark a fait 27%, le Parti pour la liberté aux Pays-Bas a fait 13% et même la Suède qui a pendant longtemps été épargnée par les partis populistes a vu un parti arriver à presque 10% qui est le Parti des démocrates de Suède. Ce phénomène décrit par l’UDC vaut également pour d’autres pays et dans la plupart des pays européens.

Les résultats aux élections parlementaires nationales permettent de nous rendre attentifs aux différences que l’on peut avoir d’une élection à l’autre. Si on prend le cas du FN qui est le plus flagrant, il a fait 25% aux élections européennes, mais deux ans plus tôt, le FN avait fait seulement 9% aux élections législatives en France.

Il faut faire attention avec ces chiffres parce que les élections européennes sont souvent des élections intermédiaires que l’on appelle des élections de deuxième ordre, ce qui veut dire que ce sont des élections où les électeurs profitent de sanctionner le gouvernement en place, de donner un signal au gouvernement. Elles n’ont pas beaucoup d’importance donc on peut se permettre d’émettre un vote de mécontentement. Cela explique peut-être pourquoi les partis de mécontents sont aussi hauts. Ils sont plus généralement dans de nombreux pays qu’aux élections législatives, mais même là, il y a des partis comme le FPE en Autriche à plus de 20%, le Cinque Stelle plus de 25%, le Parti populaire au Danemark a plus de 21%. C’est quand même un phénomène réel, mais on prend en compte en même temps les différences qu’il peut y avoir entre deux élections en fonction de leur signification et de leur portée.

Exemple 3 : sexe, âge et participation

L’étude de la participation politique est un autre champ du comportement électoral. Séquentiellement, la participation vient avant le choix électoral, il faut d’abord comprendre pourquoi les électeurs et électrices se rendent aux urnes et participent avant d’essayer de comprendre ce qu’ils votent. Logiquement, on essaie d’abord de comprendre qui participe et qui ne participe pas et pourquoi avant de comprendre qui vote pour quel parti et pour quoi.

Analyse comparative

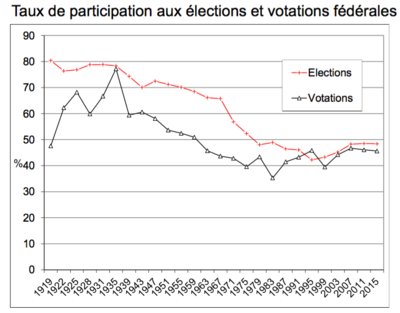

Ce premier graphique montre au niveau agrégé l’évolution du taux de participation en Suisse aux élections fédérales et aux votations fédérales depuis 1919, donc depuis la fin de la Première guerre mondiale. On a assisté dans les deux cas, pour les élections en rouge et pour les votations en noir à une forte diminution de la participation. On était à 80% pour les élections au sortir de la Première guerre mondiale et il y a eu un recul incessant jusqu’à attendre un point bas en 1995 avec moins de 45% de participation. Il y avait une participation plus basse et plus fluctuante pour les votations, mais on constate une tendance parallèle entre les années 1940 et les années 1970 pour atteindre un point bas pour les votations à la fin des années 1970 avec 40% en moyenne de participation pour les votations.

Pour les élections, le chiffre est le taux de participation pour les élections de l’année en cours. Pour les votations, il s’agit de la moyenne de participation sur toutes les votations qui ont eu lieu pendant quatre ans puisqu’on vote quatre fois par année en Suisse dans le cadre de votations fédérales. Si on veut avoir la participation pendant quatre ans, il faut calculer la moyenne de participation pendant quatre ans et après on peut ainsi comparer ces deux courbes.

Donc, il y a un déclin séculaire de la participation avec un point bas atteint dans les années 1990 pour les élections et puis une légère augmentation de la participation depuis 1995 avec une stabilité au cours des trois derniers scrutins. Le 18 octobre 2015, il y a eu environ 43 ,8% de participation, 44% en 2011 et à peu près pareils en 2007. Maintenant, au court terme des trois élections, on est une stabilité un peu en dessous de 48% de participation pour les élections et on est à peu près pareil au niveau de 43% pour les votations au court des trois derniers relevés.

L’image générale qui se dégage est une forte baisse de la participation et la question que l’on doit se poser est de savoir d’où vient cette forte baisse de la participation.

Nous allons nous concentrer sur deux facteurs qui peuvent nous aider à comprendre la participation politique qui sont deux facteurs qui permettent d’expliquer la participation et l’abstention, ce sont deux facteurs assez fondamentaux que sont le sexe et l’âge.

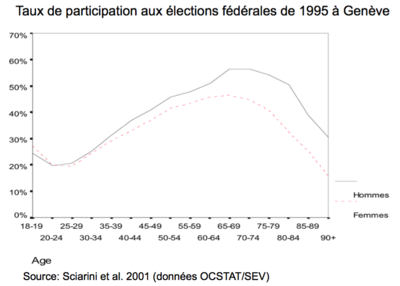

Ce sont des chiffres de l’évolution de la participation aux élections fédérales dans le canton de Genève. Les chiffres que l’on a sur ce graphique sont uniquement tirés du canton de Genève. L’intérêt de ces chiffres étant que ce sont des chiffres réels. Ce n’est pas la participation telle que mesurée dans les enquêtes d’opinion, cela est la participation réelle. Depuis 1995, le canton de Genève a eu la bonne idée de collecter et d’archiver sous format électronique les données sur la participation de tous les citoyens et citoyennes genevois ce qui permet de suivre l’évolution de la participation au cours du temps.

Ici, c’est un révélé pour les élections fédérales de 1995. C’est une courbe de participation qui est presque une courbe d’école, c’est comme cela qu’on se l’imaginait et c’est comme cela que la participation est en réalité au sein de la population.

Cette courbe est une courbe d’école. À l’âge de 18 ans, lorsque les jeunes électeurs et les jeunes électrices obtiennent leur droit de vote, il y a une participation qui est plus élevée que pour les 20 – 25 ans, parce qu’on a reçu un nouveau droit et donc il faut l’utiliser et on participe un peu plus que la catégorie suivante. Il y a un premier mouvement qui est un mouvement en « U ». Le point bas de la participation est entre les 20 – 29 ans et après, cela monte de manière quasiment linéaire avec l’âge jusqu’à 65 – 69 ans et en suite, cela redescend assez fortement dans le grand âge.

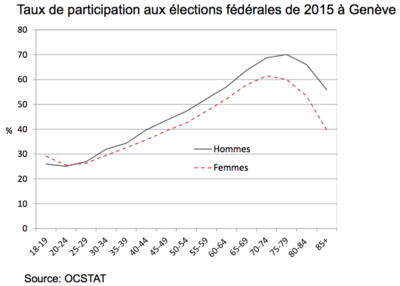

Si on reprend les mêmes chiffres pour 2015, on retrouve la même courbe avec la même inflexion après une chute qui est un peu moins abrupte, on descend moins bas que dans le graphique précédent où on descendait en dessous du niveau de participation des jeunes, mais cela est surtout dû au fait qu’il y des groupes d’âge jusqu’à 90 ans et plus, tandis que dans le graphique suivant on a regroupé toutes les personnes de 85 ans et plus. Cela a pour effet de remonter en moyenne le taux de participation.

L’autre chose qui est assez intéressante entre ces deux graphiques et qu’avant, le point haut de participation, le sommet a été atteint entre 65 ans et 75 ans pour les hommes ; en 2015, le point haut de participation concerne les 75 ans et 79 ans chez les hommes et les 70 ans et 74 ans chez les femmes. Donc, apparemment, il y a un mouvement ici qui fait que l’on vote de plus en plus tard ce qui serait assez logique avec l’allongement de l’espérance de vie pare qu’on est en meilleure santé et en meilleure forme pour être encore intégré et voter plus tard qu’avant.

Si on regarde la courbe des femmes et des hommes, dans les deux cas en 1995 comme en 2015, les jeunes femmes participent plus que les jeunes hommes. En suite, il y a un point identique pour les 20 – 24 ans dans les deux cas et après, progressivement, la différence de participation entre les hommes et les femmes tend à augmenter avec l’âge et est massive parmi les femmes et les hommes les plus âgés. Si on prend les 85 – 89 ans, il y a à peu près 40% de participation pour les femmes et plus de 30% de participation en moyenne chez les hommes. On retrouve cet écart pour les 85 et plus, 40% de participation chez les femmes et plus de 55% de participation chez les hommes. Il y a un effet d’âge puissant, mais à cet effet d’âge se double un effet de sexe en interaction avec l’âge. Il n’y a pas de différence homme – femme selon ces graphiques pour les jeunes, mais à mesure que le temps passe, que l’âge avance, il y a une proportion de plus en plus différente de femmes et d’hommes qui participe.

Nous allons maintenant essayer d’expliquer pourquoi il y a cette différence de participation en fonction de l’âge d’une part et en fonction du sexe d’autre part.

Facteur genre

Il y a d’abord des facteurs de type sociostructurel qui ont historiquement expliqué le différentiel de participation entre homme et femme.

Le premier facteur sociostructurel est la moindre intégration sociale et professionnelle de femmes. Le fait que les femmes étaient beaucoup moins intégrées dans le monde du travail, elle travaillait moins fréquemment que les hommes, restaient beaucoup plus en nombre pour s’occuper des enfants et donc restaient comme femme au foyer, ceci a fait que les femmes étaient moins intégrées socialement, moins intégrés professionnellement et cela a un impact direct sur l’engagement politique, sur la participation politique. Cela est vis-à-vis du modèle classique qui était que le fait que les femmes étaient moins intégrées socialement, professionnellement que les hommes conduit à leur moindre participation politique parce que l’intégration sociale et professionnelle et un facteur puissant d’engagement social et politique en général.

Le deuxième facteur sociostructurel est une surreprésentation des femmes parmi les états matrimoniaux favorisant l’isolement social. Si on regarde les statistiques, on constate qu’il y a beaucoup plus de femmes âgées que d’hommes âgés. Les femmes ont une espérance de vie plus longue que les hommes encore aujourd’hui même si cela tend à converger et surtout, on trouve beaucoup plus de femmes veuves que d’hommes veuf. En 2015, dans la catégorie des veufs, il y a 80% de femmes et 20% d’hommes. Dans la population, en général, il y a 51% de femmes et 49% d’hommes alors que dans le veuvage, il y a 80% de femmes et de 20% d’hommes. Cela explique en partie ce décrochage parce que le veuvage est un facteur puissant d’isolement social. Si on est veuf, on a tendance à être plus isolé, on n’a plus de conjoint, on a des enfants qui ont quitté la maison et cet isolement social contribue à un abstentionnisme politique. Comme il y a plus de femmes veuves que d’hommes veufs, cela contribue à baisser en moyenne le taux de participation chez les femmes âgées étant entendu qu’on a plus de chance d’être veuf dans le grand âge qu’avant. Il est possible de corriger faisant comme s’il y avait autant de veufs hommes que de veuves femmes, les courbes se resserrent singulièrement.

Autre explication des facteurs de type socioculturels et plus précisément la persistance des modèles traditionnels du rôle des femmes. Cela est presque indépendamment des facteurs sociostructurels qui est le fait qu’il y ait eu pendant très longtemps ce maintien du modèle classique de la vision de la femme dans la société et du rôle de la femme dans la société dans l’espace privé et dans l’espace public qui a eu pour effet de réduire le taux de participation des femmes par rapport aux hommes.

Le dernier facteur est propre à la suisse est un facteur institutionnel. Les femmes ont reçu le droit de vote très tardivement en Suisse. Les femmes ont reçu le droit de vote en Suisse au niveau fédéral en 1971, un peu plus tôt dans certains cantons, mais seulement en 1971 au niveau fédéral. Dans certains cantons conservateurs de la Suisse centrale ou orientale, il y a fallu attendre même plus tard que 1971 pour octroyer le droit de vote aux femmes au niveau cantonal. Le dernier canton qui a octroyé le droit de vote est le canton d’Appenzell Rhodes Extérieur, qui a octroyé le droit de vote aux femmes en 1991 à la suite d’un arrêt du tribunal fédéral. C’est le tribunal fédéral qui a imposé le droit de vote aux femmes en Appenzell Rhodes Extérieur parce que cette discrimination n’était pas conforme à l’égalité des droits entre hommes et femmes dans la constitution fédérale. Il y a même un canton en 1991 qui avait encore refusé jusque là le droit de vote aux femmes.