« Los actores de la política exterior » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 76 : | Ligne 76 : | ||

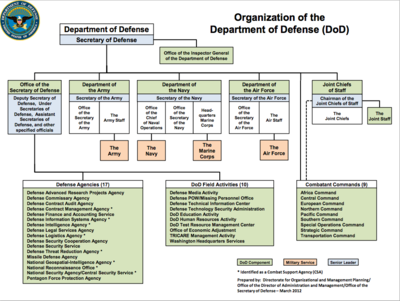

=== El Department of Defense === | === El Department of Defense === | ||

El Departamento de Defensa, que originalmente se dividió en un Departamento de Guerra y un Departamento de la Marina, se fusionará para formar el Departamento de Defensa. Este es un departamento que será cada vez más importante. En el auge del Departamento de Defensa, hay dos guerras mundiales y, en particular, las inmediatamente posteriores a la Segunda Guerra Mundial. En 1945 se produjo una desmovilización parcial, ya que todavía existían otros frentes y se avecinaba la Guerra Fría. El Departamento de Guerra, que debe ser desinflado después de un conflicto, sigue siendo importante, sobre todo porque las señales permanecen rojas en toda una serie de zonas. La Guerra Fría llegó con el voto de la Ley de Seguridad Nacional, que finalmente fusionó el Departamento de Guerra, la Marina y la Armada de los Estados Unidos y el Departamento de Aviación en un "superdepartamento" de defensa simbolizado por el Pentágono<ref>[https://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/National_Security_Act_of_1947 National Security Act of 1947 on Wikipedia]</ref><ref>[http://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/laws/nsact1947.pdf Text] en el Comité de Inteligencia</ref> del Senado de los Estados Unidos. En 2009 contaba con 2 millones de empleados, un presupuesto de 500 mil millones de dólares. Durante la Guerra Fría, el 75% de la administración estadounidense trabaja para este departamento. Hoy, el Departamento de Defensa ha tomado la delantera sobre el Departamento de Estado. | |||

[[File:DoD Organization March 2012.png|center|vignette|400px|Structure of the DoD in March 2012.]] | [[File:DoD Organization March 2012.png|center|vignette|400px|Structure of the DoD in March 2012.]] | ||

Version du 7 février 2018 à 23:37

We will describe these different actors and see how they interact over time. The American foreign policy is characterized, first of all, by an extremely important device and machinery in so far as one has to deal with a diplomacy that became global at the beginning of the 20th century. It is a multi-sectoral diplomacy that is developing in a whole series of areas being one of the absolutely fundamental elements of the concept of superpower. When we talk about superpower, we often take the politico-military aspects, but there are many others with the capacity to intervene in various fields. This diplomacy is taken care of by numerous professional and private actors.

The State Department is not the only player in American foreign policy dealing with transnational history issues. This multipolar character of American foreign policy is the permanent interaction between public and private actors who are not responsible for the diplomatic function. There is an extremely blurred border when it comes to U.S. foreign policy and the distinction between public and private because there is a permanent back-and-forth between the public and private sectors. This phenomenon is a colonization of the public sector by private actors. There is also a proliferation of public institutions whose public nature is sometimes unclear with federal agencies.

One may wonder whether or not American foreign policy is a coherent entity. Even today, the American position is difficult to determine because different actors take the floor and it is difficult to see how they agree. Foreign policy is also permanently between centralisation, i.e. coordination by the state authorities and decentralisation by the fact that the administration and government can be complemented or competing or contradicted by other institutions that will move in a different direction. As long as the United States has an increasingly global policy, we are witnessing a diversification of decision-making centres.

La diarquía Presidente/Congreso

Distribution of original powers

Esta diarquía es absolutamente fundamental porque tenemos dos jefes de la rama ejecutiva tanto en política interna como en política exterior. El sistema de controles y contrapesos es un sistema político marcado fundamentalmente por el equilibrio de poder. Cada poder tiene un contrapoder que se hace obligatorio por la constitución norteamericana para lograr la síntesis entre el poder fuerte para luchar contra los elementos externos y el respeto de la libertad interior para evitar la tiranía.

Los poderes del Congreso

El Congreso es el poder dominante en los Estados Unidos al principio. El Congreso es el elemento fundamental del sistema político estadounidense al principio. Es el Congreso quien tiene el poder de declarar la guerra y poner fin a la misma mediante la ratificación de tratados, le da al ejército los medios financieros y logísticos para funcionar, desde el punto de vista de la implementación de la política exterior es el que ratifica los nombramientos en todas las administraciones federales y en particular el Secretario de Estado que es un cargo clave. Por otra parte, el Congreso y el Senado, a través de la Comisión de Relaciones Exteriores, pueden tratar toda una serie de temas, incluyendo la audiencia de funcionarios administrativos. El Senado y el Congreso también regulan la inmigración. Es una institución fundamental y fundadora que al principio de la historia americana tiene la mayor parte de las prerrogativas.

Poderes del Presidente

El Presidente sólo ocupa el segundo lugar en la Constitución en el artículo 2[1]. En la cultura legal estadounidense, un presidente es un tirano potencial, razón por la cual el presidente es elegido a través del Congreso, pero también puede ser destituido por el Congreso. Es el comandante de los ejércitos. El Presidente puede iniciar una operación militar sin que se derogue el parlamento por un período limitado de hasta 60 días, tras lo cual el Congreso y la Comisión de Asuntos Exteriores deben aprobarlo, y eso es lo que ocurrió durante la intervención en Kosovo en 1999. Esto también marca un refuerzo de las prerrogativas del Presidente de los Estados Unidos. Al negociar y firmar tratados, representa a la nación. Esta es una de las cosas que el presidente ha asumido sobre la marcha, pero el Congreso debe ratificarla. De 1789 a 1989 sólo 21 tratados no fueron ratificados de los más de 1500 firmados, incluido el Tratado de Versalles. También nombra secretarios y embajadores.

Cambios en las relaciones de poder

Es a la vez un equilibrio de poder y un equilibrio de poder desde finales del siglo XVIII hasta nuestros días. Todavía estamos en un proceso de este tipo con cuatro ideas generales:

- Refuerzo continuo de los poderes del Presidente[ver el aumento de los acuerdos ejecutivos a expensas de los tratados]: desde finales del siglo XIX y hasta hoy, ha habido un fortalecimiento de los poderes del Presidente en relación con los poderes del Senado. A medida que los Estados Unidos se expanden y emergen en la escena internacional, esto se ajustará a las prerrogativas presidenciales en materia de política exterior. Un tratado puede ser firmado como tal o como un acuerdo ejecutivo. Cuando se considera tratado, debe pasar por el Congreso, de lo contrario si es un acuerdo ejecutivo, el texto firmado no pasa por el Congreso. El Presidente se asegurará de que los textos firmados sean "acuerdos ejecutivos" para eludir el poder del Senado.

- En tiempos de crisis, el Congreso se sienta detrás del presidente.

- Las fases de expansión están marcadas por una preeminencia del ejecutivo con personalidades fuertes como Wilson y Roosevelt.

- Desde 1980, las relaciones se han vuelto cada vez más conflictivas: existe un equilibrio de poder, pero estas relaciones se han vuelto cada vez más conflictivas interna y externamente desde los años setenta y ochenta, con un cambio en la mayoría más del 90% de las veces.

Desde la creación de la República Americana hasta finales del siglo XIX, hubo un predominio del Congreso en la política exterior, aunque Monroe se distanció de ella en los años 1804. Hay una bisagra entre los años 1890 y 1914 donde hay un cambio muy claro en el equilibrio de poder marcado por Theodore Roosevelt y Woodrow Wilson, que rompe el marco bastante restringido de las prerrogativas presidenciales. Roosevelt arroga la misión de "la americanización del mundo..." mientras que Wilson encarna el ascenso de la política exterior estadounidense viajando en persona a la Conferencia de Versalles.

En el período de entreguerras, hubo un aumento continuo de los poderes del presidente. El período de 1919 a la Segunda Guerra Mundial estuvo marcado por una fuerte confrontación entre el Presidente y el Congreso, que se basó en un equilibrio de poder entre las dos instituciones. En primer lugar, está la oposición al Tratado de Versalles de 1919, que es, en primer lugar, un voto del Senado contra Wilson y no contra el Tratado de Versalles, recordándonos que es él quien tiene el poder de decidir si ratifica o no el Tratado. A partir de la década de 1930, cuando Roosevelt llegó, la confrontación entre el presidente y el Congreso se reanudó, entre otras cosas, sobre el establecimiento del New Deal en la política interna, pero hubo fuertes objeciones a la política exterior, ya que las leyes de neutralidad fueron aprobadas por el Congreso en contra del consejo de Roosevelt.

Después de estas fuertes oposiciones en la década de 1930 fue la época de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, cuando el Congreso estaba detrás de Roosevelt, lo que Arthur Schlesinger llamó el comienzo de la "presidencia imperial" hasta la década de 1950, cuando el poder presidencial alcanzó su máximo apogeo en política exterior e interior.

En la década de 1950, hubo un cambio de escenario en el que el Congreso recuperó una ventaja con la Guerra de Vietnam, que primero fue disputada por el público y luego por el Senado, en particular con respecto a los gastos que entrañaba. En 1972 se aprobó la Ley de Caso Zablocki, que exige al presidente consultar al Congreso para cualquier acuerdo ejecutivo que limite su capacidad. En 1973 se aprobó la Ley de Poder Bélico, que estipula que el presidente debe buscar la aprobación del Congreso para un compromiso de las tropas militares estadounidenses más allá de dos meses. Estos son dos elementos significativos de la inversión del péndulo.

A partir de la década de 1970, el Senado se embarcará en una evaluación de los programas federales, y en particular de los programas federales destinados al mundo exterior. Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Estados Unidos se embarcó en la implementación de políticas globales de ayuda. En la década de 1980, la presidencia de Reagan relanzó la Guerra Fría sin referencia al Congreso, una época en la que gran parte de la iniciativa recayó en el gobierno federal.

La década de 1990 estuvo marcada por una confrontación bastante constante entre la presidencia de Bill Clinton, quien, durante casi todos los mandatos, tuvo que lidiar con un Senado de mayoría republicana y, por lo tanto, la política exterior estadounidense estuvo marcada por una serie de decisiones presidenciales y contradecisiones. Hubo una intervención en Somalia en 1994, pero muy rápidamente el Congreso se negó a seguir financiando esta intervención, lo que condujo a la retirada de los Estados Unidos, lo que condujo al fracaso de la intervención. En 1995, Estados Unidos intervino en Yugoslavia al frente de la OTAN. Esta intervención se hace, pero sólo tardó poco tiempo en ser rechazada. A partir del decenio de 1990, los Estados Unidos bloquearon el pago de la contribución de los Estados Unidos a las Naciones Unidas decidido por el Congreso, y aún hoy en día los fondos todavía no se pagan a las Naciones Unidas como contribución. En 1999, se rechazó la ratificación del Tratado de prohibición completa de los ensayos nucleares, que era una prioridad máxima para Clinton. Durante la presidencia de Clinton, la interferencia entre la política interior y exterior estuvo muy presente.

En la década de 2000, después del 11 de septiembre, se aprobó la Ley Patriota para fortalecer las prerrogativas presidenciales en la lucha contra el terrorismo. Entre 2001 y 2004, el Congreso se solidariza con el presidente George W. Bush. La invasión de Afganistán e Irak sólo podría ser posible porque la función presidencial ha recuperado el control sobre sus prerrogativas.

Hay un hilo conductor claro que atraviesa el equilibrio de poder entre la Presidencia y el Congreso. Hay un proceso que ha evolucionado a favor del polo presidencial.

El laberinto burocrático

Es la idea que en la implementación de la política exterior estadounidense. Cada vez hay más instituciones involucradas en la política exterior estadounidense. Es un fenómeno crucial en la historia de los Estados Unidos que es la proliferación burocrática, que es un fenómeno de todos los grandes estados industriales con una proliferación de organizaciones burocráticas y administrativas. Para entender la política exterior estadounidense, hay que tener en cuenta esta dimensión.

En la década de 1970, Graham Alisson desarrolló el concepto de política burocrática. Es una idea que nos permite pensar en la toma de decisiones políticas y estatales en el contexto de un proceso complejo de toma de decisiones y rivalidad entre departamentos. Este laberinto burocrático es colosal en Estados Unidos para ilustrar esta polifonía de la política exterior estadounidense. El fenómeno duradero del ascenso del presidente estadounidense es una diarquía entre la administración federal y el Congreso.

Los Departamentos

El Department of State

El Departamento que es más importante desde el principio es el Departamento de Estado porque divide a la administración federal en la implementación de la política exterior. En 1789 eran pequeñas administraciones, mientras que a partir del siglo XX crecieron. El Departamento de Estado vio aumentar su número de empleados de 6 en 1789 a 20.000 en la década de 1960. El Secretario de Estado tiene seis subsecretarios que deben negociar entre sí. El personal es el órgano rector. Hay toda una serie de pisos que hacen compleja la implementación de esta compleja política.

A largo plazo, existe una administración del Departamento de Estado muy tradicional fundada como una diplomacia tradicional que es el negocio de los profesionales y que ha tardado mucho tiempo en adaptarse a las nuevas realidades diplomáticas. Es un concepto bastante clásico de las relaciones internacionales.

Este Departamento de Estado, que funcionó en simbiosis con el Presidente a principios del siglo XIX, verá cómo sus relaciones con el Presidente se deterioran, ya que las prerrogativas del Presidente se ejercerán cada vez más en detrimento del Congreso, pero también en detrimento de su Secretario de Estado, que inicialmente se convirtió en colaborador y no en albacea. Los informes se vuelven difíciles porque el secretario de Estado tiene dificultades para admitir el fortalecimiento de los poderes presidenciales. Gradualmente, el Departamento de Estado será marginado y competirá con otros departamentos que tomarán más iniciativas en la formulación de políticas exteriores.

El Department of Defense

El Departamento de Defensa, que originalmente se dividió en un Departamento de Guerra y un Departamento de la Marina, se fusionará para formar el Departamento de Defensa. Este es un departamento que será cada vez más importante. En el auge del Departamento de Defensa, hay dos guerras mundiales y, en particular, las inmediatamente posteriores a la Segunda Guerra Mundial. En 1945 se produjo una desmovilización parcial, ya que todavía existían otros frentes y se avecinaba la Guerra Fría. El Departamento de Guerra, que debe ser desinflado después de un conflicto, sigue siendo importante, sobre todo porque las señales permanecen rojas en toda una serie de zonas. La Guerra Fría llegó con el voto de la Ley de Seguridad Nacional, que finalmente fusionó el Departamento de Guerra, la Marina y la Armada de los Estados Unidos y el Departamento de Aviación en un "superdepartamento" de defensa simbolizado por el Pentágono[2][3] del Senado de los Estados Unidos. En 2009 contaba con 2 millones de empleados, un presupuesto de 500 mil millones de dólares. Durante la Guerra Fría, el 75% de la administración estadounidense trabaja para este departamento. Hoy, el Departamento de Defensa ha tomado la delantera sobre el Departamento de Estado.

Otros departamentos harán que la relación entre Estados Unidos y el mundo sea única porque la política exterior estadounidense y el expansionismo se expresan de otras maneras en una multiplicidad de áreas políticas.

El Treasury Department

El Departamento del Tesoro adquiere una gran importancia, especialmente en el momento de las negociaciones del Tratado de Versalles. Los Estados Unidos, después de la Primera Guerra Mundial, debían desempeñar un papel financiero, en particular en las cuestiones económicas del período de entreguerras, con la cuestión de las reparaciones, las deudas de guerras y los créditos de los aliados, que se resolvieron mediante una serie de planes como el plan Dawes y el plan Young. El desarrollo de estos planes se lleva a cabo en gran medida con la ayuda del Departamento del Tesoro, que desempeña un papel cada vez más importante en la diplomacia estadounidense, a medida que los asuntos económicos adquieren cada vez más importancia en las relaciones internacionales. Tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el Departamento del Tesoro desempeñó un papel destacado en la Conferencia de Bretton Woods. A partir de los años setenta, este departamento incrementó su papel en materia financiera durante las cumbres del G8.

El Department of Commerce

El Departamento de Comercio gestiona las relaciones económicas y comerciales de Estados Unidos con el resto del mundo. Desde el momento en que el poder estadounidense adquirió importancia, durante el siglo XX su papel aumentará. Las principales negociaciones del GATT y la OMC se conciben en gran medida en el Departamento de Comercio.

El Department of Justice

Teniendo en cuenta la reciente evolución de los órganos judiciales internacionales durante el siglo XX con la Corte Internacional de Justicia en particular y la Corte Penal Internacional, el Departamento de Justicia está a la vanguardia. Este departamento desempeñará un papel importante en la lucha contra el tráfico de drogas.

La política exterior concebida inicialmente en el Departamento de Estado, a medida que avanza la expansión norteamericana y la dilatación de sus áreas de intervención, hay una polarización de los lugares de decisión de la política exterior norteamericana.

El National Security Council[NSC]: un State Department?

Hay otras agencias que juegan un papel en la implementación de la política exterior estadounidense, y en particular el Consejo de Seguridad Nacional, que fue visto como un Departamento de Estado. Fue creado por la Ley de Seguridad Nacional en 1947. Es un órgano restringido para la necesaria coordinación de los órganos de política exterior en el contexto de la Guerra Fría. Su composición limitada crecerá rápidamente. Es una organización que pronto eclipsará al Departamento de Estado porque tiene un acceso más directo al presidente involucrado en la implementación de las principales políticas exteriores de Estados Unidos desde la década de 1960 en adelante.

Servicios de inteligencia

Los servicios de inteligencia son organizaciones que se han multiplicado desde las décadas de 1910 y 1920. A finales de la década de 1980, había 10 servicios de inteligencia identificados en los Estados Unidos que a menudo competían entre sí. En particular, la proliferación de los servicios de inteligencia ha impedido el flujo de información sobre el ataque de Pearl Harbour que ha llevado a la centralización de los servicios.

Hasta la Segunda Guerra Mundial, se consideró que no debía haber un solo servicio de inteligencia que creara una situación cercana al Estado nazi alemán. Con la Segunda Guerra Mundial, hubo un proceso de centralización que tuvo lugar con la creación de la Oficina de Información de Guerra en 1941, que difundió información y propaganda. En 1942 se crearon dos importantes informaciones con la Oficina de Información de Guerra[OWI] y la Oficina de Servicios Estratégicos[OSS], que se ocupaban de inteligencia y espionaje. Las prerrogativas de estas dos agencias están claramente definidas.

Entre 1945 y 1947 se prevé un desmantelamiento, pero con el advenimiento de la Guerra Fría, el proceso de centralización avanzará con la Ley de Seguridad Nacional que creará la CIA fusionando el OWI y el OSS. La misión de la CIA es recopilar inteligencia, particularmente en los países comunistas, y llevar a cabo una serie de misiones encubiertas. La CIA depende directamente del Consejo de Seguridad Nacional. En 1961 la CIA planificará la operación de la Bahía de Cochinos, que fue un fracaso, pero también la operación de los Cóndores y toda una serie de otras cosas, como los contratos de financiamiento en Nicaragua para pagar el régimen marxista-leninista en vigor.

Los escándalos de la Guerra Fría llevaron a la adopción de la Ley de Supervisión de la Inteligencia en 1991 para enmarcar las actividades de la CIA[4]. Sin embargo, la CIA no significa el fin de otros servicios de inteligencia. Existe una centralización oficial con la creación de la CIA, pero en la práctica la cuestión de la inteligencia sigue siendo descentralizada. Además, existe competencia entre la FIB, que se ocupa de los asuntos internos, y la CIA, que se ocupa de la seguridad exterior. Cuando se trata de la lucha contra el terrorismo, estos dos servicios compiten entre sí. Existen vínculos extremadamente frágiles entre las diferentes estructuras.

Organismos gubernamentales

Es una etapa más de la política exterior. Las agencias gubernamentales son estructuras públicas o parapúblicas que están más o menos vinculadas a los Departamentos vinculados y autónomos. Son agencias federales independientes de los Departamentos o secretarías pero que forman parte de sus prerrogativas desde estos Departamentos o secretarías.

La política exterior estadounidense es mil hojas de papel entre organizaciones extremadamente diferentes que reportan a personas muy diferentes. El control sobre todas estas organizaciones no es tan fuerte como uno podría pensar. Hay una multitud de estructuras ad hoc y no departamentales como la Agencia de Información de los Estados Unidos[USIA] creada en 1953 e integrada en el Departamento de Estado en 1999, la Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional[USAID], 1961. Integrado en parte en el Departamento de Estado después de 1989, el Organismo de Control de Armas y Desarme[ACDA] fue fundado en 1961 e integrado en el Departamento de Estado en 1999.

Private actors

Private actors initially appear to be fairly straightforward but are more complicated than they appear to be. Private actors have a role in U.S. foreign policy. In U.S. foreign policy, private actors are even more important than in other countries. The federal state, in American history, comes second only. Historically, the federal state is weak and gradually asserting itself during the 20th century, the actors having gained in importance will maintain it.

The division between public and private actors is closely linked to the question of general interest. The general interest, the public interest, the interest of the nation is not only in theory embodied by the sovereign. More generally, what defines the general interest in the United States is the balance of power between the various actors in American foreign policy. The American general interest is only the result of the balance of the various forces that are investing in the political field, which makes it possible to explain a number of aspects of American foreign policy.

Private actors participate in foreign policy in three ways:

- Lobbying: putting pressure on the public authorities to steer foreign policy in a particular direction;

- through field action: by conducting their "own diplomacy";

- by expert work: in the construction of foreign policy.

Lobbying in Congress

Lobbying is particularly active in Congress. Lobbying is an integral part of the American political culture, even being indicated in the Constitution of 1787 as a "right to petition", meaning that every citizen has the right to petition Congress. It is an essential element of the freedom of expression that underpins a lobbying right that will become institutionalized throughout American foreign and domestic politics. Lobbying is built according to the principle of the Checks and Balances with the idea that everyone can express their opinion and the one who is able to mobilize more in their favour wins. The general interest was the result of a sum of interests representing the lobbying system.

Lobbying is first and foremost a practice that will be legally regulated from the 1940s onwards in order to avoid a certain number of excesses, then legally recognized as such in the Federal Regulation of Lobbying Act of 1946 and supplemented by the Lobbying disclosure Act of 1995, which determines precisely which groups are accredited to Congress. It's a series of interest groups that have been represented by specialized firms in Washington.

There are three types of organisations and lobbies working in foreign policy at the Congress.

- NGOs: like Human Rights Watch;

- economic lobbies: all trade union associations such as the American Chamber of Commerce or employers' associations such as the National Association of Manufacturers and the AFL-CIO. The Congress will be approached by a series of large associations representing groups from the production sectors to represent the interests of their corporate branches;

- Ethical groups: practically all diasporas have their own lobby group in Congress, such as the Israelis who will push for the implementation of a foreign policy in favour of Israel, the Cuban lobby, Armenians, etc.

Lobbyists are not necessarily of private origin. The federal administration sometimes arouses a number of lobbies to override Congress, such as the American Israel Public Committee and administration to support the Eisenhower administration in implementing a foreign policy in favour of the Israeli state or the Cuban lobby in the Reagan administration to tighten immigration policy.

Action on the ground

Lobbying is only one element of the action of government actors, much of this work is done on the ground. From a transnational perspective, these actors act alongside, outside, against, parallel to the administration. By acting in parallel, they act outside of state boundaries and the state context. Non-governmental actors are not in contact with countries, the border issue is not of particular interest to them. Their latitude of action is not that of the American government, which is generally more flexible and responsive to events. It is questionable whether these non-state actors are completely independent or structurally dependent on the US state. No U.S. non-governmental organization is completely independent of the U.S. government, nor do they have the same understanding of the national interest as the state interest.

Foreign policy is conducted by a host of parallel organisations. Protestant missions throughout the world, for example, have both their own specificity, acting in some way, but above all, there are structures that are organizations that are evangelized movements promoting at the same time an Anglo-Saxon way of life and values, in particular constituting a significant strike force throughout the 19th century.

The great philanthropic foundations that developed from the end of the 19th century onwards are throughout the 20th century implementing philanthropic diplomacy. Foundations are organizations that set up humanitarian campaigns in Latin America, Asia and Europe that are both campaigns for the eradication of diseases and at the same time do so with an American apparatus that helps modernize public health facilities. It's a projection of American foreign policy. These large organizations, such as the Rockefeller Foundation in the inter-war period, the Ford Foundation in the Cold War, conduct a true diplomacy with substantial funds.

NGOs developed during the First World War, such as CARD in the interwar period and with refugee aid committees. Between 1975 and 1988 will be set up Watch-Human Rights Watch and in 1993 will be founded Transparency International. They are humanitarian organizations that will act in particular in the First World War. These organizations are part of a global projection of the United States into the world embodying a number of principles.

The industrialists and bankers led a banking diplomacy in the inter-war period, with the establishment of loans that allowed a number of post-World War I reconstruction in coordination with the State Department. The role is so important that they are more expansionist than the U.S. government itself because their financial interests are not the geopolitical interests of the U.S. government at the time, particularly in order to penetrate a number of banking markets.

Institutions of expertise: think tanks

This is one of the originalities of the American political system and American foreign policy. Expertise plays a major role in U.S. foreign policy since, at the end of the 19th century, the idea was to base political decision-making on precise, scientific and objective data and, finally, the decision maker had to rely on scientists to build his or her foreign policy and decision-making. The United States emerged as a world power at the end of the 19th century. The idea is that they must build a global foreign policy, so they must have instruments to steer this policy so that they can intervene in all geographical areas. It is the idea of having the instruments at your disposal that allow you to intervene everywhere and at any time, particularly by having at your disposal an important scientific expertise.

With the issue of think tanks, we are in a distinction between private and public actors, extremely blurred because, in the end, think tanks are there to make the link between the public and private spheres and, in general, between the academic world, which is a provider of knowledge, and the political world, which needs knowledge to carry out its policy and concrete actions. It is the idea of bridging the gap and providing usable knowledge. The think-tank system is an academic type of knowledge but at the same time it must be usable by the political world. They are sometimes private organizations, sometimes public, sometimes public, sometimes both with a mixed character often falling under their financing. People are both public servants in the federal administration, sometimes private academics, sometimes both, there is institutionalized permeability. Think tanks are a foreign policy provider being a component of the Foreign Policy Establishment that represents an environment that is a small group that makes American foreign policy.

There are several generations of think tanks.

First Generation

The first generation appeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace [CEIP] founded in 1910 as one of the many organizations founded by Carnegie Magna Steel Magna in the United States with the aim of promoting international law worldwide. Not only is it an organization that develops a whole series of studies on what international law is, it also supports a whole series of institutions that develop international law. The Court allowing arbitration established after the Hague Conference is created with funds from Carnegie. The establishment of the Permanent Court of International Justice in 1921 will also be supported. The foundation also lobbies American political and legal circles to bring the United States into a wide range of international circles. This foundation is dominated by the great barons of the Republican Party highlighting the hybrid character of these organizations.

The Council on Foreign Relations was established in 1921 at the initiative of Elihu Root. It was created in reaction to the refusal to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, which divides a large part of the American political class. Finally, there is a whole internationalist faction of American political and academic circles that argues that the rejection of the Treaty of Versailles must be counterbalanced by inserting the United States as much as possible into the international arena through the development of solutions. Initially, the Council on Foreign Relations reflected on the place that the United States should have in the international system.

From 1922 onwards, the journal Foreign Affairs was created to develop expertise on these issues. During the Second World War, as early as 1939 - 1940, the Council on Foreign Relations worked for the Foreign Department of State, launching a series of studies called "War and Peaces Studies", which brought together 682 reports, analysing what the post-1945 world would be like and how American foreign policy in the post-1945 world would look like. One of the main persons in charge of this programme is John Foster, who in 1953 became Secretary of State for Eisenhower. The Council on Foreign Relations is becoming an important political laboratory for foreign policy.

The Institute of Pacific Relations was established in 1925. It is an institution that brings together private and public actors from the United States which is a kind of federation of different centres of expertise located in the Eastern United States and whose different centres are coordinated by the American section being a semi-public, semi-private mixed structure. This institute deals with geopolitical issues in the Pacific region, including the creation of Pacific Affairs magazine in 1926. If this institute deals with the Pacific region, it is no coincidence that after the First World War, the Pacific was a geographical area for American foreign policy, hence the idea of benefiting from precise expertise on geopolitical issues and being able to feed the circle of political decision-makers on what is happening in these regions.

The Committee for Economic Development was founded in 1942 during the Second World War. It is one of those multiple institutes of expertise being created during this period and which will be working on the post-war economic order and the reorganization of the world economy, in particular the Treasury Department, which will influence the attitude of the role of decision-makers in the Bretton Wood Conference which provides the framework for the post-war economy. Work will also be developed, including the genesis of the Marshall Plan. One of the conclusions dreaming of these studies is that part of Europe is going to be completely destroyed and will need heavy funding to support their economies.

Second Generation

The second generation appears after the Second World War and with the Cold War. One thing distinguishes them, of course, is that the Cold War context is quite different from the post-World War I and wartime context.

The legacy is the context left by the Second World War and the Cold War, which will be the promotion of scientific issues and the important role of science in the war. The scientific questions will produce arguments but also guide policy, particularly the Bretton Woods Conference and the post-war conferences, where economists played a fundamental role.

The organizations are much more institutionalized than in the years 1910-1920, tending to become consulting firms under contract to the federal government. Links are institutionalized with contracts and the federal government will commission studies on specific topics. This is the case of the RAND Corporation created in 1948.

The RAND Corporation is a product of the Cold War context, highlighting the permeability between public/private and quasi-institutionalized, since the RAND Corporation is the result of an agreement between Douglas and the U.S. Air Force. The RAND Corporation is going to work on researching new weapons in the framework of the arms race between the United States and the USSR. The objective is to enable the United States to maintain an advance on nuclear weapons. It is also a matter of knowing the impact of chemical and nuclear weapons on human beings and the environment. The RAND Corporation is also working to develop what will become the doctrine of deterrence, which is at the heart of the concept of balancing terror that has become the centre of geopolitical opposition in the heart of the Cold War. Mutual assured destruction[MAD] is the fact that if an opponent attacks, the damage he will suffer as a result of the riposte is so great that he will not carry out his attack. It is the idea that the United States has an increasingly important nuclear arsenal but that it should not be used, otherwise destruction would be too great. The systematization of reality and doctrine is largely due to the Rand Corporation. A division of the social sciences, headed by Hans Speier, is looking at propaganda issues to ensure that they have an impact on the target countries.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies was established in 1962 as a bipartisan think tank specializing in safety issues.

The Project for a New American Century[PNAC] created in 1997 lived until 2006. This think tank is clearly labelled and linked to the neoconservative movement of the Republican Party. Its objective is to promote comprehensive American leadership from a political and military standpoint to reinvent its leadership in the context of a new world order. The founders of this think tank are well-known people like Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowit. This project brings together politicians as well as academics like Robert Kagan and publicists like William Kristol.

The priority objective of the NACP is to reshape the geopolitical map of the Middle East. This is the context of the late 1990s when the Golf War took place, Iraq was expelled from Kuwait, and the idea is to bring democracy by force if necessary but also end the first Golf War by bringing down Saddam Hussein. This program will be set up under the Bush administration, and these personalities will become the driving force behind the implementation of this program set up by the NACP. With the return to power of a certain number of people, the theorized project within the framework of this think tank becomes George Bush's political line facilitated by the September 11 terrorist attack that changed the cards in the American foreign policy that allowed the state official doctrine. The bridge is also opaque between public and private with Dick Cheney who is vice-president at the same time as he has interests in Halliburton, a company that will be awarded oil contracts in the aftermath of the Second Golf War.

Institutions of Expertise: Private Actors in the Federal Administration

They are not institutions as such, but actors working closely with the federal government in a range of specific areas. The Inquiry that emerged in the years 1917-1919 is a whole staff of experts who came with Wilson to the peace conference and worked for two years on Europe's political reshaping issues, bringing together historians, economists, anthropologists, linguists and demographers in anticipation of what the United States' participation in peace will be through a series of questions and studies. The second most important body in the American delegation is the Inquiry.

The Second World War brought the same process to the forefront, but in a tenfold increase. From the very beginning of the war, a whole series of experts were mandated to work on a number of issues. They are in particular emigrants from the European intellectual community who will work in the federal administration during the whole war. The center of all this work is the OSS with the Research and Analysis Branch, which is first a more or less independent branch and then integrated into the Department of State in 1945. In 1941, the Division of Special Research was created. At the end of the Second World War, part of it went to universities and part to the State Department. At the moment when the CIA is going to be created, some of the academics will play an important role in it. Large departments also employ private actors such as the State Department working with institutionalized think tanks but will hire a number of people as the departure from the defense. It can be considered that the federal administration is at the top of the decision-making process, but it can also be considered that the federal administration is colonized by a number of private actors.

Institutions of expertise: universities

Universities, which are privately owned, play an important role in the production of expertise that forms a partnership with the federal government. The issue of national security in the United States is a priority objective. Especially culturally, the notion of security is very important in understanding U.S. foreign policy, but the role of scientific knowledge in preserving national security plays an important role. This is a post-war reality, particularly in the context of the Cold War.

Area studies are a whole series of interdisciplinary studies that cover specific geographical eras, combining historical, political and linguistic aspects in order to understand certain geographical areas. They are interdisciplinary departments. Expansion into American universities is closely linked to the emergence of the United States in international relations. These specialties guide American foreign policy. These disciplines are closely linked to the geopolitical context.

These area studies began timidly in the inter-war period but the Second World War gave them considerable expansion as the United States reached the status of a great power and area studies provided the framework for the United States to shape its global policy. These are structures that were in the 1930s and World War II financed by private foundations and which after the Second World War were to be financed by intergovernmental funds. There is a direct continuity between the OSS and the study areas. Within the framework of the OSS, specialists working in certain regions, once demobilized, will find jobs in universities that are starting to create area studies departments. The major areas where area studies are developing are, first of all, Russia because it is quite clear that there is a need for the federal administration to know its enemy. The development of all these specialists provides expertise on regions of potential interest to the federal government.

The issue of psychology and propaganda in the Cold War context is central because it is a geopolitical war and also a war of propaganda, culture and messages, since the two powers know full well that they will not go to war with each other. Propaganda warfare is an important instrument of the Cold War. Psychologists will be mobilized in the implementation of American Cold War policy to decode and target Russian propaganda.

Through the question of private actors and expertise, it is clear that, depending on the context and on both sides of the two wars, government agencies and the federal agency have played a very important role in the role of these disciplines, which does not mean that the academic disciplines subsumed with the political field, the field of knowledge production, which is hardly independent of the political field and vis versa.