« Intervention: Reinventing war? » : différence entre les versions

(Page créée avec « La sous question est la guerre réinventée, car la question est de savoir ce qui distingue une « intervention militaire » du « concept de guerre » ou de conflit armé... ») |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| Ligne 1 : | Ligne 1 : | ||

The sub-topic is reinvented war, because the question is what distinguishes a "military intervention" from the "concept of war" or armed conflict, is talking about "military intervention" or "humanitarian intervention" simply a matter of going to war without saying so, i. e. deploying warfare practices, but using a different vocabulary or are they international practices different from those of war, and in this case it would be necessary to conclude that the States have not yet done so? It must be seen that since 1945, Western governments no longer admit to war when they deploy armed forces, whether in the context of decolonisation, for wars involving the projection of forces with expeditionary forces to third countries. This raises the question of whether it is the same thing, but with a different vocabulary or whether it is something new militarized, but sufficiently different from traditional warfare. | |||

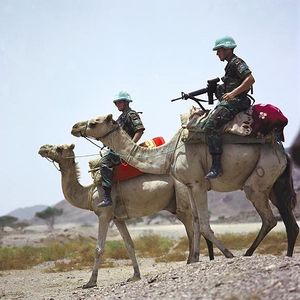

[[File:UN Soldiers in Eritrea.jpeg|thumb|right|300px|United Nations soldiers, part of United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea, monitoring the Eritrea-Ethiopia boundary.]] | [[File:UN Soldiers in Eritrea.jpeg|thumb|right|300px|United Nations soldiers, part of United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea, monitoring the Eritrea-Ethiopia boundary.]] | ||

How is war defined and what are the differences between "war" and "intervention"? We will see what the dominant discourses are to show its impasses and that it is very difficult to draw a scientific definition of the uses made of government intervention as a Western priority, and we will see how military missions described as "intervention" share a number of characteristics that still differentiate them from war as conceived and practiced in the 18th and 19th centuries. Even if in the current discourse we have the impression that the speech of intervention was born in the post-Cold War period, in reality it is a discourse that dates back to before the 19th century in legal discourses, but also from the point of view of practices. | |||

There are paradoxes that can be seen when we talk about war today. The first is that the constitution of the modern state in Europe is inseparable by monopolisation by the sovereign or the future state of the right to wage war. An idea is constitutive of political modernity which is that only the sovereign state can legitimately wage war in its inter-state relations abroad and in extreme cases internally in civil war situations. War has long been regarded as a state prerogative, and today the concept of war is used to describe armed conflicts involving non-state actors and failed states. The "New Wars" are wars in which governments confront non-state groups where there are war or militia groups, guerrillas who confront each other and yet it is above all these occurrences of armed conflict that are called war. When Western states or multinational coalitions intervene in these countries, we no longer speak of "war", but of "intervention" as if war today had become the central notion used to describe the use of violence by non-state groups, and if modern states use force, we deny that it is war and its warlike character, and we speak of "intervention". | |||

In other words, states do not just wage war, but speak of "intervention". In short, war has long been seen as the sovereign prerogative of the state. Today, the concept of war is often used in connection with armed conflicts involving centralized non-state groups and "failed states" in the context of "New Wars". Barring exceptions, modern states do not admit that they are at war, they are content with "interventions". | |||

The notion of interventionism was once always denied, sometimes even in favour of war. The intervention was seen as violating the principle of sovereignty. Today, the notion of "war" is being denied, often in favour of the notion of "intervention". When a state is accused of waging war, if it is said that a coalition is going to wage war against Afghanistan and Iraq, the answer will be that it is not a "war", but an "intervention" as if the intervention had a negative connotation beforehand, but that it had a positive connotation today, particularly because there was a tendency to add adjectives like this one. Nowadays, war is considered an illegal practice, except in exceptional cases. In the UN Charter, war in general is a prohibited practice between states except in the case of self-defence or Security Council resolutions. | |||

A government practice that had never existed before was to justify the non-interventionist. When France, the United Kingdom or the United States say that they are not intervening in Syria, they must justify themselves. The reason why the justification of intervention is new is that previously, it was necessary to justify intervention which was an exceptional practice at the limit of illegality, the normality of the international system was non-intervention. Today, there is a situation in which States feel compelled to justify non-interventionism because the norm would be to intervene in humanitarian or exceptional crises. There is a transformation that needs to be analyzed in order to understand what is at stake in interventionism and to see to what extent the concept of "intervention" is different or not from that of "war". | |||

= | = An elusive phenomenon = | ||

== | == A new interventionism? == | ||

There is often the idea that under the UN charter, the United Nations must play an active role and allow the use of force in order to create conditions and guarantee international peace and security when international peace is threatened. Because of the Security Council's stalemate, this dimension of the UN Charter could never have been implemented during the Cold War with the idea that, with the end of the Cold War, there was an unblocked Security Council. There would be a new era of humanitarian intervention different from "political" interventions linked to Cold War issues. It is the idea that after 1990 there was a "New World Order" with the idea that the Security Council could apply what Kaldor calls "cosmopolitan law enforcement". The debates on the right of interference that took place in the 1990s, mainly in France, is now known as "R2P" or "Responsability to Protect", which is one of the legal justifications to be used in Libya and which makes it possible to try to justify interventions in Syria or elsewhere. | |||

Ignatieff | Ignatieff was originally a Canadian scholar and philosopher who wanted to make the theory of this new interventionism and conceptualization into the creation of a "humanitarian empire" that would challenge the sovereignty of states that would use force against their own people. One of the first humanitarian interventions was Operation provide comfort, a multilateral operation in Iraqi Kurdistan following the First Golf War. After the First Golf War, there was a rebellion in northern Iraq by the Kurds and in southern Iraq by Shiites who challenged the central government, taking advantage of the weakness of the Iraqi bassist government following its defeat in the First Golf War. Saddam Hussein and the Baathist regime harshly suppress the Shia and Baathist rebellion. In this context, the United States is passing a resolution in the Security Council that states that an international coalition must provide military and humanitarian assistance to the Kurdish people in order to put an end to the massacres of the Kurdish people. The reason why the same type of intervention is not being carried out in southern Iraq is because the Americans are afraid that the Shiite uprising will be led by Iran. | ||

UNSC Resolution 688 will justify this operation in northern Iraq in 1991. Under the United Nations Charter and a United Nations Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force, such use of force in a third country authorized by a Security Council resolution is only possible on the basis of the argument that such intervention is being carried out to guarantee the peace and security of the international order. The resolution says that the rebellion has taken on such proportions that it threatens peace and international order that humanitarian and military aid can be provided. What is new is not only the qualification of this intervention as "humanitarian", but also that for the first time, humanitarian crises are or can be considered a threat to peace or international security that can justify interventionism. It is on the basis of this convention that other interventions such as those in Somalia, Bosnia and Kosovo will take place, with the argument that humanitarian crises or civil wars can take on such proportions as to undermine and threaten international peace that justifies the use of force. | |||

L’explication par le seul activisme de post Guerre froide du Conseil de sécurité est faible. Considérer que c’est simplement parce que l’Union soviétique n’existe plus et que de ce fait il n’y a plus de blocage au Conseil de sécurité lorsqu’il s’agit de mettre en application l’esprit et la lettre de la Charte de l’ONU est insuffisant parce que certaines de ces interventions ont eu lieu sans résolution du Conseil de sécurité, soit parce que les États concernés n’ont pas jugé utile de faire voter une résolution comme en 2003 avec l’invasion de l’Irak ou soit parce qu’il y a eu un véto au Conseil de sécurité, mais qui est suivit d’une intervention au Kosovo. C’est seulement après que la guerre à produit sont effet voulu à savoir l’autorisation par Milosevic d’autoriser une intervention de l’OTAN qui justifie la présence de la CAFOR et justifie a posteriori l’opération militaire de l’OTAN, mais comme il n’y a pas de principe de rétroactivité du droit et des résolutions de l’ONU, l’intervention de l’OTAN contre la Serbie et le Monténégro en 1999 est illégale. La justification était que cette intervention était illégale, mais légitime. Expliquer l’interventionnisme dit « humanitaire » post Guerre froide par la fin de la Guerre froide est simpliste notamment parce que des États on contournés le Conseil de sécurité pour mener des interventions. | L’explication par le seul activisme de post Guerre froide du Conseil de sécurité est faible. Considérer que c’est simplement parce que l’Union soviétique n’existe plus et que de ce fait il n’y a plus de blocage au Conseil de sécurité lorsqu’il s’agit de mettre en application l’esprit et la lettre de la Charte de l’ONU est insuffisant parce que certaines de ces interventions ont eu lieu sans résolution du Conseil de sécurité, soit parce que les États concernés n’ont pas jugé utile de faire voter une résolution comme en 2003 avec l’invasion de l’Irak ou soit parce qu’il y a eu un véto au Conseil de sécurité, mais qui est suivit d’une intervention au Kosovo. C’est seulement après que la guerre à produit sont effet voulu à savoir l’autorisation par Milosevic d’autoriser une intervention de l’OTAN qui justifie la présence de la CAFOR et justifie a posteriori l’opération militaire de l’OTAN, mais comme il n’y a pas de principe de rétroactivité du droit et des résolutions de l’ONU, l’intervention de l’OTAN contre la Serbie et le Monténégro en 1999 est illégale. La justification était que cette intervention était illégale, mais légitime. Expliquer l’interventionnisme dit « humanitaire » post Guerre froide par la fin de la Guerre froide est simpliste notamment parce que des États on contournés le Conseil de sécurité pour mener des interventions. | ||

When it comes to "humanitarian intervention", practices are not necessarily new, sending military forces on humanitarian grounds denying that it was a war has existed before. The vocabulary may have been different, but the spirit of some expeditionary military missions to protect local populations while denying that this was a war operation already existed. Post-Cold War operations are part of longer stories. Great Britain, France and Russia intervened in the Greek War of Independence in 1827 to defend a Christian and Orthodox population against the Ottoman Empire. When the Greeks revolted in 1827, leading to the creation of the modern Greek sovereign state, this was against the operation presented as a war between Christianity and the great caliphate leading to the justification of the deployment of troops with the argument that it was a question of "defending the common humanity of the Greeks against the atrocities committed by the Ottoman Empire". At the time, there was a moral and ethical discourse, essentially humanitarian, to justify this intervention. It is not a question of protecting sovereignty, but of protecting "Christian brothers"; there is a humanitarian justification for this intervention. | |||

[[Fichier:French expeditionary corps landing in Beyrouth 16 August 1860.jpg|vignette|French expeditionary corps led by General Beaufort d'Hautpoul, landing in Beirut on 16 August 1860.]] | [[Fichier:French expeditionary corps landing in Beyrouth 16 August 1860.jpg|vignette|French expeditionary corps led by General Beaufort d'Hautpoul, landing in Beirut on 16 August 1860.]] | ||

In 1860 and 1861, Napoleon III sent a military force to Syria and Lebanon to protect Maronite Christians in conflict with the Druze. Napoleon III justifies this operation as a "humanitarian operation". It is about defending the humanity of threatened individuals reduced to Christianity. We see the same thing with Russia in the unrest in Bulgaria, which intervened in 1877, justifying its action in the name of humanitarian principles assimilated to a Christian community for people threatened by atrocities and atrocities. Humanitarian intervention as conceived today has a longer history. | |||

What characterizes an intervention today is a matter of "general principles", including humanitarian principles. Intervention "is justified in the name of the general interests of humanity, whereas" war "almost automatically implies the denunciation of limited national interests in order to describe the use of force by States conducting war. This was not always the case, because even during the Cold War a number of armed conflicts were justified in the name of humanitarian principles, perceived by the international community and carried out for humanitarian purposes, but which were not qualified as intervention. Equivalence between "humanitarian principle" and "intervention" is something new. The justification of war in the name of "principles of justice" has a long history, especially with the paradigm of "just war" with Saint Thomas Aquinas, which distinguishes between "jus ad bellum" and "jus in bellum". Intervention to defend the dignity or right of a population was one of the possibilities for a "just war". The justification of the war through what we now call "humanitarian principle" is not so new. | |||

The Ougando-Tanzanian war in 1978 and 1979 saw Tanzania wage war on the dictator Amine Dada, presented by Tanzania as a war of self-defence since it was a war justified by the threat, but at the same time, this war made it possible to put an end to the exactions made by Amine Dada against her own people. This was justified as a "just war" with benefits on the ground, especially in terms of protecting local populations. Nevertheless, it is not conceived of as an "intervention", but as a "war of self-defence". The Indo-Pakistani war of 1971 was the war in which Pakistan split in two with Pakistan as it is known today and Bangladesh, which was part of Pakistan. This is done through secession, which is justified in particular by the exactions and ethnic discrimination exercised by the Pakistani State against the Bengali populations. India will support Bangladesh's revolt against Pakistan leading to this war, which was presented by India as a "self-defence war", but at the time it produced mainly beneficial effects in a context of harsh discrimination against the Bangladeshi people. At the time, there was no equivalence between the "principle of intervention" and "humanitarian war" at a time when the "principle of intervention" was urgent. The invasion of Cambodia by Vietnam in 1979, four years after the victory of North Vietnam over South Vietnam ending the Vietnam War in 1975, the reunified Vietnamese armed forces launched an invasion war against Cambodia concerning itself threatened by the Khmer Rouge regime and at the same time it made it possible to put an end to the Cambodian exactions on its population putting an end to the genocide. At the time, there was talk of "intervention" on the pretext that it would be a "humanitarian war", even if it was a "self-defence war" and even if there were beneficial effects for local populations. | |||

These remarks make it possible to put into perspective two types of discourse, which is the novelty of post-Cold War interventionism, since there is a much older interventionist tradition, particularly with humanitarian objectives, and it is not the humanitarian objectives as such that constitute interventionism. | |||

== | == The quest for an impossible definition == | ||

There are no undisputed definitions of intervention, but generally speaking,"intervention" is distinguished from "war". When we talk about "intervention", there is the use of force and the use of armed forces, but at the same time it is not war. According to the UN Charter, war is illegal in Articles 2 and 4, except for Article 51 and Chapter VII. The conditions are so restrictive that war must be better denied when it is practised. | |||

We are talking about the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, journalistic or scientific vocabulary, but officially these events have not been recognized as "war". It is not illegality as such that systematically leads governments to speak of intervention rather than war, but rather the general delegitimisation of the notion of "war" since 1945. Even wars presented as "legal" and perceived as such are generally denied as such by their protagonists. Under the First Golf War, the United States did not recognize it as a "war", but as the "use of international force sanctioned by the Security Council". Also for Afghanistan where the term "war" is used metaphorically. | |||

How the war was denied in those cases where scientific and journalistic language agreed that it was indeed "war". The idea often put forward to say that it was not a question of war was to define it in relation to the "old institution" of "inter-State war" and to show that it is not one. In the case of the first golf war, the justification is that it is not a war against the state, but against a "component of society". In the 2001 intervention in Afghanistan, George Bush justified it as not a "war" because it was not against the Afghan state, but against the Afghan regime. In interventionist rhetoric, the term "regime" is used to deny the existence of "government". | |||

The concept of "war" defined in a very strict sense is to justify intervention in the context of war and refers to the traditional definition, whereas current interventions are not wars against a State. Inter-state wars are not only wars between states, but wars between governments. In the case of Afghanistan, this was the argument since, by recognizing only Afghanistan before the Afghanistan war, being in conflict with the illegitimate Taliban regime is to be in conflict with the Afghan state. This notion of "regime" in the context of intervention serves to deny the governmental character of the authorities in place. In the framework of Libya, the Transitional Council was recognised as the government of Libya, being at war with Gaddafi was at war with the government of Gaddafi alongside the legitimate Libyan government. | |||

Assuming that war is only the inter-state war, one can deny that one is at war by denying the sovereign character of the government in power in favour of a rebel coalition. Even if there has been no armed intervention in Syria, the current discourse of the French government, which considers the Syrian coalition to be a legitimate authority, is in the direction of a coalition. It is a political justification that works by denying the war character of a conflict. From the legal point of view this is questionable. It is when we do not want to say that we are in "war" that we say that we are in an intervention, but the notion of "intervention" differs from the "diplomatic peace mission" because when we speak of "intervention", generally it is in the context of a coercive intervention against an authority in power considered to be governmental or not. Missions often speak of "counter-insurgency" or "peace-building" as part of this interventionist paradigm, which are described as "neither peace nor war" to deny their warlike character. At the same time, it is different from peace because it does not involve the use of force, except for peacekeeping operations under Chapter VI on the principle of "neither war nor peace", but the objective is peace, but it is also the case for many wars. | |||

Often, the objective of "regime-change" or "support" to a government is seen as an important criterion. There is the idea that intervention cannot result in border changes such as annexation, but conversely that intervention on the contrary of war is aimed at overthrowing a government, consolidating a regime or restructuring a regime in a way that is more consistent with international law or principles considered universal. The First Golf War in 1991 was designed as an "intervention" but did not lead to regime change. The UN resolutions related to this intervention do not go so far as to justify the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, even though Bush called for the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, helping to trigger revolts in Kurdistan and the Shiite south because these populations had hoped to be supported by the outside world. | |||

An important criterion when trying to legally define the concept of intervention is the notion of "breach of State sovereignty". It is aimed at regime change or restructuring and violates the sovereignty of the State in place to such an extent that the principle of sovereignty in the UN charter translates into the "principle of non-intervention" since "intervention" is the opposite of "sovereignty", seeking to govern the territory of a third State, changing the government to change the sovereign character of the authorities in place. When one considers that a mission was consented to by a government following an aerial bombardment, whether that consent is free and sovereign is open to debate in Bosnia's case. The positive connotation of the notion of "intervention" in contrast to that of "war" means that operations that violate the principle of sovereignty are referred to as operations interventions. Intervention "was only referred to as an" intervention "when there was a flagrant violation of a government's sovereignty, and an" intervention "was a violation of the" principle of non-intervention ". | |||

Before the 1990s, the criterion of infringement of sovereignty was no longer systematically applied. During the Cold War, when a State was accused of intervening in a third State, the justification was to deny any intervention by saying that the real government of that State had agreed to intervention by denying the governmental character of the authorities in power. In the case of the United States in South Vietnam, U. S. armed forces are present between 1963 and 1973, this is not considered a war since the United States denies being at war with Vietnam, but they also deny that it is an intervention since they argue that they were invited by the North Vietnamese government to intervene in South Vietnam. The question is whether Di? m was a legitimate president since elections that were supposed to be held did not take place. It is a type of justification for denying the interventionism of military operations. When intervening States are accused of violating the sovereignty of a State, it is argued that they are invited to do so by the legitimate government. During the Prague intervention, this was officially to support the Czech Communist Party, but invited by the legitimate government of Czechoslovakia. In contrast to the notion of "war", governments prefer to use the notion of "intervention", but in relation to the violation of sovereignty, governments tended to deny the interventionist nature of their military operations. This practice consists in denying the character of an intervention by arguing that a country is invited to intervene by the legitimate government. | |||

[[Fichier:Wladiwostok Parade 1918.jpg|vignette|Allied troops parading in Vladivostok, 1918.]] | [[Fichier:Wladiwostok Parade 1918.jpg|vignette|Allied troops parading in Vladivostok, 1918.]] | ||

If "intervention" is the opposite of "sovereignty", it is sufficient to redefine "sovereignty" to redefine "intervention". In other words,"intervention" is "sovereignty" and vice versa rather than simply violating it. In 1821 an Austro-Hungarian intervention took place in the Kingdom of Naples. The Austro-Hungarian Empire intervenes to restore the king with its full powers, arguing that this is not an intervention since the true sovereign of Naples is the king, by restoring his monarchy, is restored his monarchical sovereignty. This redefines sovereignty as monarchic sovereignty, which makes it possible to say that it is not an intervention, but a support for the sovereign. In 1917, U. S. President Wilson sent an allied military force in the context of the 1917 Communist revolution to support the anti-communists against the Communist army. Wilson's argument is that there was an illegal coup d' état by the Communist Party and that it supports popular sovereignty and cannot intervene because it would be a violation of sovereignty. Wilson defines the concept of sovereignty as inseparable from democracy. In Panama in 1989, the United States will intervene against President Manuel Noriega, the argument being that it is not a real intervention since it restores democracy. If intervention is legally defined as a violation of sovereignty, it is not a violation of sovereignty since it restores it. | |||

Today, one way in which intervention is defined is according to the principle of "responsibility to protect" derived from the ICISS report published in 2000. All states are presumed to have a duty to protect their own people. This report defines sovereignty as taking on the responsibility of protecting one's people, which also means not committing acts of violence against them. Intervention is nevertheless permitted when a state does not protect its own people because if it does, then it does not respect sovereignty because sovereignty is the "responsibility to protect". R2P "is the legal explanation given by the Security Council for the intervention in Libya against Qaddafi with the idea that Qaddafi had lost its sovereignty because it was committing acts of violence against its people. | |||

This shows the extreme fluidity of the concepts. There is a tendency to define intervention in relation to sovereignty. Sovereignty can always be redefined by the speaker, but in reality, the notion of both "sovereignty" and "intervention" are malleable and potentially can be exploited according to the intervention strategies implemented by States. When sovereignty is redefined as either "monarchic sovereignty","popular sovereignty" or "responsibility to protect", it redefines intervention. | |||

The'' The responsibility to protect'' report was endorsed by the UN in 2005, but not any state can declare that there is an urgent need for intervention by a third state. The Security Council must be seized and there must be a UN resolution for a government to justify its intervention under the R2P. It's hard to figure out what an intervention is. Defining it in relation to war, peace or sovereignty raises the question of whether it is authority, the effective and legitimate government that endorses sovereignty. | |||

= | = Historical Characteristics of Military Interventionism = | ||

It is possible to analyse the emergence of the historical concept of intervention. | |||

== | == The emergence of interventionism == | ||

Dans quel contexte émerge la catégorie spécifique de l’intervention comme modalité de recours à la force par un État contre un autre ? Avant le Congrès de Vienne de 1815, avant les guerres napoléoniennes, le concept d’intervention n‘existait pas, il y avait seulement la guerre qui conformément à l’institution interétatique de la guerre impliquait un conflit entre deux monarques sur des questions territoriales et se soldait en général par une annexion d’une partie d’un territoire d’un État par un autre État. Avant le Congrès de Vienne, ce type de guerre d’annexion était considérée comme quelque chose de relativement normal dans les relations entre gouvernements et cela était même vu comme un mécanisme de résolution des conflits permettant d’allouer des ressources. Le principe de la « conquête territoriale » a vu réémerger la possibilité de créer à l’échelle de l’Europe un empire. Suite aux guerres révolutionnaires, Napoléon envahit une partie de l’Europe pour constituer un empire européen aux dépens de l’ordre européen. Au Congrès de Vienne, le principe d’annexion et d’intervention sont délégitimés. Il peut y avoir recours à la force entre États, mais il faut éviter les guerres comme celles du XVIIIème siècle qui se solde par des annexions. On considère que l’annexion est sinon illégitime pour maintenir un équilibre des puissances. Dans le cas du traité de Vienne, il s’agit d’un « equilibrium of power » qui est un équilibre des puissances fondé sur un certain nombre de principes, mais c’est aussi l’idée que les États du continent européen partagent un certain nombre de principes et de valeurs et l’équilibre de force entre les États est garant de la souveraineté des États contre l’oppression d’un empire. Cela suppose de limiter les possibilités d’annexion assimilée à la notion de « guerre ». La guerre n’est pas rendue illégale, mais elle est délégitimée comme institution auquel les États peuvent systématiquement avoir recours. | Dans quel contexte émerge la catégorie spécifique de l’intervention comme modalité de recours à la force par un État contre un autre ? Avant le Congrès de Vienne de 1815, avant les guerres napoléoniennes, le concept d’intervention n‘existait pas, il y avait seulement la guerre qui conformément à l’institution interétatique de la guerre impliquait un conflit entre deux monarques sur des questions territoriales et se soldait en général par une annexion d’une partie d’un territoire d’un État par un autre État. Avant le Congrès de Vienne, ce type de guerre d’annexion était considérée comme quelque chose de relativement normal dans les relations entre gouvernements et cela était même vu comme un mécanisme de résolution des conflits permettant d’allouer des ressources. Le principe de la « conquête territoriale » a vu réémerger la possibilité de créer à l’échelle de l’Europe un empire. Suite aux guerres révolutionnaires, Napoléon envahit une partie de l’Europe pour constituer un empire européen aux dépens de l’ordre européen. Au Congrès de Vienne, le principe d’annexion et d’intervention sont délégitimés. Il peut y avoir recours à la force entre États, mais il faut éviter les guerres comme celles du XVIIIème siècle qui se solde par des annexions. On considère que l’annexion est sinon illégitime pour maintenir un équilibre des puissances. Dans le cas du traité de Vienne, il s’agit d’un « equilibrium of power » qui est un équilibre des puissances fondé sur un certain nombre de principes, mais c’est aussi l’idée que les États du continent européen partagent un certain nombre de principes et de valeurs et l’équilibre de force entre les États est garant de la souveraineté des États contre l’oppression d’un empire. Cela suppose de limiter les possibilités d’annexion assimilée à la notion de « guerre ». La guerre n’est pas rendue illégale, mais elle est délégitimée comme institution auquel les États peuvent systématiquement avoir recours. | ||

Version du 8 février 2018 à 20:18

The sub-topic is reinvented war, because the question is what distinguishes a "military intervention" from the "concept of war" or armed conflict, is talking about "military intervention" or "humanitarian intervention" simply a matter of going to war without saying so, i. e. deploying warfare practices, but using a different vocabulary or are they international practices different from those of war, and in this case it would be necessary to conclude that the States have not yet done so? It must be seen that since 1945, Western governments no longer admit to war when they deploy armed forces, whether in the context of decolonisation, for wars involving the projection of forces with expeditionary forces to third countries. This raises the question of whether it is the same thing, but with a different vocabulary or whether it is something new militarized, but sufficiently different from traditional warfare.

How is war defined and what are the differences between "war" and "intervention"? We will see what the dominant discourses are to show its impasses and that it is very difficult to draw a scientific definition of the uses made of government intervention as a Western priority, and we will see how military missions described as "intervention" share a number of characteristics that still differentiate them from war as conceived and practiced in the 18th and 19th centuries. Even if in the current discourse we have the impression that the speech of intervention was born in the post-Cold War period, in reality it is a discourse that dates back to before the 19th century in legal discourses, but also from the point of view of practices.

There are paradoxes that can be seen when we talk about war today. The first is that the constitution of the modern state in Europe is inseparable by monopolisation by the sovereign or the future state of the right to wage war. An idea is constitutive of political modernity which is that only the sovereign state can legitimately wage war in its inter-state relations abroad and in extreme cases internally in civil war situations. War has long been regarded as a state prerogative, and today the concept of war is used to describe armed conflicts involving non-state actors and failed states. The "New Wars" are wars in which governments confront non-state groups where there are war or militia groups, guerrillas who confront each other and yet it is above all these occurrences of armed conflict that are called war. When Western states or multinational coalitions intervene in these countries, we no longer speak of "war", but of "intervention" as if war today had become the central notion used to describe the use of violence by non-state groups, and if modern states use force, we deny that it is war and its warlike character, and we speak of "intervention".

In other words, states do not just wage war, but speak of "intervention". In short, war has long been seen as the sovereign prerogative of the state. Today, the concept of war is often used in connection with armed conflicts involving centralized non-state groups and "failed states" in the context of "New Wars". Barring exceptions, modern states do not admit that they are at war, they are content with "interventions".

The notion of interventionism was once always denied, sometimes even in favour of war. The intervention was seen as violating the principle of sovereignty. Today, the notion of "war" is being denied, often in favour of the notion of "intervention". When a state is accused of waging war, if it is said that a coalition is going to wage war against Afghanistan and Iraq, the answer will be that it is not a "war", but an "intervention" as if the intervention had a negative connotation beforehand, but that it had a positive connotation today, particularly because there was a tendency to add adjectives like this one. Nowadays, war is considered an illegal practice, except in exceptional cases. In the UN Charter, war in general is a prohibited practice between states except in the case of self-defence or Security Council resolutions.

A government practice that had never existed before was to justify the non-interventionist. When France, the United Kingdom or the United States say that they are not intervening in Syria, they must justify themselves. The reason why the justification of intervention is new is that previously, it was necessary to justify intervention which was an exceptional practice at the limit of illegality, the normality of the international system was non-intervention. Today, there is a situation in which States feel compelled to justify non-interventionism because the norm would be to intervene in humanitarian or exceptional crises. There is a transformation that needs to be analyzed in order to understand what is at stake in interventionism and to see to what extent the concept of "intervention" is different or not from that of "war".

An elusive phenomenon

A new interventionism?

There is often the idea that under the UN charter, the United Nations must play an active role and allow the use of force in order to create conditions and guarantee international peace and security when international peace is threatened. Because of the Security Council's stalemate, this dimension of the UN Charter could never have been implemented during the Cold War with the idea that, with the end of the Cold War, there was an unblocked Security Council. There would be a new era of humanitarian intervention different from "political" interventions linked to Cold War issues. It is the idea that after 1990 there was a "New World Order" with the idea that the Security Council could apply what Kaldor calls "cosmopolitan law enforcement". The debates on the right of interference that took place in the 1990s, mainly in France, is now known as "R2P" or "Responsability to Protect", which is one of the legal justifications to be used in Libya and which makes it possible to try to justify interventions in Syria or elsewhere.

Ignatieff was originally a Canadian scholar and philosopher who wanted to make the theory of this new interventionism and conceptualization into the creation of a "humanitarian empire" that would challenge the sovereignty of states that would use force against their own people. One of the first humanitarian interventions was Operation provide comfort, a multilateral operation in Iraqi Kurdistan following the First Golf War. After the First Golf War, there was a rebellion in northern Iraq by the Kurds and in southern Iraq by Shiites who challenged the central government, taking advantage of the weakness of the Iraqi bassist government following its defeat in the First Golf War. Saddam Hussein and the Baathist regime harshly suppress the Shia and Baathist rebellion. In this context, the United States is passing a resolution in the Security Council that states that an international coalition must provide military and humanitarian assistance to the Kurdish people in order to put an end to the massacres of the Kurdish people. The reason why the same type of intervention is not being carried out in southern Iraq is because the Americans are afraid that the Shiite uprising will be led by Iran.

UNSC Resolution 688 will justify this operation in northern Iraq in 1991. Under the United Nations Charter and a United Nations Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force, such use of force in a third country authorized by a Security Council resolution is only possible on the basis of the argument that such intervention is being carried out to guarantee the peace and security of the international order. The resolution says that the rebellion has taken on such proportions that it threatens peace and international order that humanitarian and military aid can be provided. What is new is not only the qualification of this intervention as "humanitarian", but also that for the first time, humanitarian crises are or can be considered a threat to peace or international security that can justify interventionism. It is on the basis of this convention that other interventions such as those in Somalia, Bosnia and Kosovo will take place, with the argument that humanitarian crises or civil wars can take on such proportions as to undermine and threaten international peace that justifies the use of force.

L’explication par le seul activisme de post Guerre froide du Conseil de sécurité est faible. Considérer que c’est simplement parce que l’Union soviétique n’existe plus et que de ce fait il n’y a plus de blocage au Conseil de sécurité lorsqu’il s’agit de mettre en application l’esprit et la lettre de la Charte de l’ONU est insuffisant parce que certaines de ces interventions ont eu lieu sans résolution du Conseil de sécurité, soit parce que les États concernés n’ont pas jugé utile de faire voter une résolution comme en 2003 avec l’invasion de l’Irak ou soit parce qu’il y a eu un véto au Conseil de sécurité, mais qui est suivit d’une intervention au Kosovo. C’est seulement après que la guerre à produit sont effet voulu à savoir l’autorisation par Milosevic d’autoriser une intervention de l’OTAN qui justifie la présence de la CAFOR et justifie a posteriori l’opération militaire de l’OTAN, mais comme il n’y a pas de principe de rétroactivité du droit et des résolutions de l’ONU, l’intervention de l’OTAN contre la Serbie et le Monténégro en 1999 est illégale. La justification était que cette intervention était illégale, mais légitime. Expliquer l’interventionnisme dit « humanitaire » post Guerre froide par la fin de la Guerre froide est simpliste notamment parce que des États on contournés le Conseil de sécurité pour mener des interventions.

When it comes to "humanitarian intervention", practices are not necessarily new, sending military forces on humanitarian grounds denying that it was a war has existed before. The vocabulary may have been different, but the spirit of some expeditionary military missions to protect local populations while denying that this was a war operation already existed. Post-Cold War operations are part of longer stories. Great Britain, France and Russia intervened in the Greek War of Independence in 1827 to defend a Christian and Orthodox population against the Ottoman Empire. When the Greeks revolted in 1827, leading to the creation of the modern Greek sovereign state, this was against the operation presented as a war between Christianity and the great caliphate leading to the justification of the deployment of troops with the argument that it was a question of "defending the common humanity of the Greeks against the atrocities committed by the Ottoman Empire". At the time, there was a moral and ethical discourse, essentially humanitarian, to justify this intervention. It is not a question of protecting sovereignty, but of protecting "Christian brothers"; there is a humanitarian justification for this intervention.

In 1860 and 1861, Napoleon III sent a military force to Syria and Lebanon to protect Maronite Christians in conflict with the Druze. Napoleon III justifies this operation as a "humanitarian operation". It is about defending the humanity of threatened individuals reduced to Christianity. We see the same thing with Russia in the unrest in Bulgaria, which intervened in 1877, justifying its action in the name of humanitarian principles assimilated to a Christian community for people threatened by atrocities and atrocities. Humanitarian intervention as conceived today has a longer history.

What characterizes an intervention today is a matter of "general principles", including humanitarian principles. Intervention "is justified in the name of the general interests of humanity, whereas" war "almost automatically implies the denunciation of limited national interests in order to describe the use of force by States conducting war. This was not always the case, because even during the Cold War a number of armed conflicts were justified in the name of humanitarian principles, perceived by the international community and carried out for humanitarian purposes, but which were not qualified as intervention. Equivalence between "humanitarian principle" and "intervention" is something new. The justification of war in the name of "principles of justice" has a long history, especially with the paradigm of "just war" with Saint Thomas Aquinas, which distinguishes between "jus ad bellum" and "jus in bellum". Intervention to defend the dignity or right of a population was one of the possibilities for a "just war". The justification of the war through what we now call "humanitarian principle" is not so new.

The Ougando-Tanzanian war in 1978 and 1979 saw Tanzania wage war on the dictator Amine Dada, presented by Tanzania as a war of self-defence since it was a war justified by the threat, but at the same time, this war made it possible to put an end to the exactions made by Amine Dada against her own people. This was justified as a "just war" with benefits on the ground, especially in terms of protecting local populations. Nevertheless, it is not conceived of as an "intervention", but as a "war of self-defence". The Indo-Pakistani war of 1971 was the war in which Pakistan split in two with Pakistan as it is known today and Bangladesh, which was part of Pakistan. This is done through secession, which is justified in particular by the exactions and ethnic discrimination exercised by the Pakistani State against the Bengali populations. India will support Bangladesh's revolt against Pakistan leading to this war, which was presented by India as a "self-defence war", but at the time it produced mainly beneficial effects in a context of harsh discrimination against the Bangladeshi people. At the time, there was no equivalence between the "principle of intervention" and "humanitarian war" at a time when the "principle of intervention" was urgent. The invasion of Cambodia by Vietnam in 1979, four years after the victory of North Vietnam over South Vietnam ending the Vietnam War in 1975, the reunified Vietnamese armed forces launched an invasion war against Cambodia concerning itself threatened by the Khmer Rouge regime and at the same time it made it possible to put an end to the Cambodian exactions on its population putting an end to the genocide. At the time, there was talk of "intervention" on the pretext that it would be a "humanitarian war", even if it was a "self-defence war" and even if there were beneficial effects for local populations.

These remarks make it possible to put into perspective two types of discourse, which is the novelty of post-Cold War interventionism, since there is a much older interventionist tradition, particularly with humanitarian objectives, and it is not the humanitarian objectives as such that constitute interventionism.

The quest for an impossible definition

There are no undisputed definitions of intervention, but generally speaking,"intervention" is distinguished from "war". When we talk about "intervention", there is the use of force and the use of armed forces, but at the same time it is not war. According to the UN Charter, war is illegal in Articles 2 and 4, except for Article 51 and Chapter VII. The conditions are so restrictive that war must be better denied when it is practised.

We are talking about the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, journalistic or scientific vocabulary, but officially these events have not been recognized as "war". It is not illegality as such that systematically leads governments to speak of intervention rather than war, but rather the general delegitimisation of the notion of "war" since 1945. Even wars presented as "legal" and perceived as such are generally denied as such by their protagonists. Under the First Golf War, the United States did not recognize it as a "war", but as the "use of international force sanctioned by the Security Council". Also for Afghanistan where the term "war" is used metaphorically.

How the war was denied in those cases where scientific and journalistic language agreed that it was indeed "war". The idea often put forward to say that it was not a question of war was to define it in relation to the "old institution" of "inter-State war" and to show that it is not one. In the case of the first golf war, the justification is that it is not a war against the state, but against a "component of society". In the 2001 intervention in Afghanistan, George Bush justified it as not a "war" because it was not against the Afghan state, but against the Afghan regime. In interventionist rhetoric, the term "regime" is used to deny the existence of "government".

The concept of "war" defined in a very strict sense is to justify intervention in the context of war and refers to the traditional definition, whereas current interventions are not wars against a State. Inter-state wars are not only wars between states, but wars between governments. In the case of Afghanistan, this was the argument since, by recognizing only Afghanistan before the Afghanistan war, being in conflict with the illegitimate Taliban regime is to be in conflict with the Afghan state. This notion of "regime" in the context of intervention serves to deny the governmental character of the authorities in place. In the framework of Libya, the Transitional Council was recognised as the government of Libya, being at war with Gaddafi was at war with the government of Gaddafi alongside the legitimate Libyan government.

Assuming that war is only the inter-state war, one can deny that one is at war by denying the sovereign character of the government in power in favour of a rebel coalition. Even if there has been no armed intervention in Syria, the current discourse of the French government, which considers the Syrian coalition to be a legitimate authority, is in the direction of a coalition. It is a political justification that works by denying the war character of a conflict. From the legal point of view this is questionable. It is when we do not want to say that we are in "war" that we say that we are in an intervention, but the notion of "intervention" differs from the "diplomatic peace mission" because when we speak of "intervention", generally it is in the context of a coercive intervention against an authority in power considered to be governmental or not. Missions often speak of "counter-insurgency" or "peace-building" as part of this interventionist paradigm, which are described as "neither peace nor war" to deny their warlike character. At the same time, it is different from peace because it does not involve the use of force, except for peacekeeping operations under Chapter VI on the principle of "neither war nor peace", but the objective is peace, but it is also the case for many wars.

Often, the objective of "regime-change" or "support" to a government is seen as an important criterion. There is the idea that intervention cannot result in border changes such as annexation, but conversely that intervention on the contrary of war is aimed at overthrowing a government, consolidating a regime or restructuring a regime in a way that is more consistent with international law or principles considered universal. The First Golf War in 1991 was designed as an "intervention" but did not lead to regime change. The UN resolutions related to this intervention do not go so far as to justify the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, even though Bush called for the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, helping to trigger revolts in Kurdistan and the Shiite south because these populations had hoped to be supported by the outside world.

An important criterion when trying to legally define the concept of intervention is the notion of "breach of State sovereignty". It is aimed at regime change or restructuring and violates the sovereignty of the State in place to such an extent that the principle of sovereignty in the UN charter translates into the "principle of non-intervention" since "intervention" is the opposite of "sovereignty", seeking to govern the territory of a third State, changing the government to change the sovereign character of the authorities in place. When one considers that a mission was consented to by a government following an aerial bombardment, whether that consent is free and sovereign is open to debate in Bosnia's case. The positive connotation of the notion of "intervention" in contrast to that of "war" means that operations that violate the principle of sovereignty are referred to as operations interventions. Intervention "was only referred to as an" intervention "when there was a flagrant violation of a government's sovereignty, and an" intervention "was a violation of the" principle of non-intervention ".

Before the 1990s, the criterion of infringement of sovereignty was no longer systematically applied. During the Cold War, when a State was accused of intervening in a third State, the justification was to deny any intervention by saying that the real government of that State had agreed to intervention by denying the governmental character of the authorities in power. In the case of the United States in South Vietnam, U. S. armed forces are present between 1963 and 1973, this is not considered a war since the United States denies being at war with Vietnam, but they also deny that it is an intervention since they argue that they were invited by the North Vietnamese government to intervene in South Vietnam. The question is whether Di? m was a legitimate president since elections that were supposed to be held did not take place. It is a type of justification for denying the interventionism of military operations. When intervening States are accused of violating the sovereignty of a State, it is argued that they are invited to do so by the legitimate government. During the Prague intervention, this was officially to support the Czech Communist Party, but invited by the legitimate government of Czechoslovakia. In contrast to the notion of "war", governments prefer to use the notion of "intervention", but in relation to the violation of sovereignty, governments tended to deny the interventionist nature of their military operations. This practice consists in denying the character of an intervention by arguing that a country is invited to intervene by the legitimate government.

If "intervention" is the opposite of "sovereignty", it is sufficient to redefine "sovereignty" to redefine "intervention". In other words,"intervention" is "sovereignty" and vice versa rather than simply violating it. In 1821 an Austro-Hungarian intervention took place in the Kingdom of Naples. The Austro-Hungarian Empire intervenes to restore the king with its full powers, arguing that this is not an intervention since the true sovereign of Naples is the king, by restoring his monarchy, is restored his monarchical sovereignty. This redefines sovereignty as monarchic sovereignty, which makes it possible to say that it is not an intervention, but a support for the sovereign. In 1917, U. S. President Wilson sent an allied military force in the context of the 1917 Communist revolution to support the anti-communists against the Communist army. Wilson's argument is that there was an illegal coup d' état by the Communist Party and that it supports popular sovereignty and cannot intervene because it would be a violation of sovereignty. Wilson defines the concept of sovereignty as inseparable from democracy. In Panama in 1989, the United States will intervene against President Manuel Noriega, the argument being that it is not a real intervention since it restores democracy. If intervention is legally defined as a violation of sovereignty, it is not a violation of sovereignty since it restores it.

Today, one way in which intervention is defined is according to the principle of "responsibility to protect" derived from the ICISS report published in 2000. All states are presumed to have a duty to protect their own people. This report defines sovereignty as taking on the responsibility of protecting one's people, which also means not committing acts of violence against them. Intervention is nevertheless permitted when a state does not protect its own people because if it does, then it does not respect sovereignty because sovereignty is the "responsibility to protect". R2P "is the legal explanation given by the Security Council for the intervention in Libya against Qaddafi with the idea that Qaddafi had lost its sovereignty because it was committing acts of violence against its people.

This shows the extreme fluidity of the concepts. There is a tendency to define intervention in relation to sovereignty. Sovereignty can always be redefined by the speaker, but in reality, the notion of both "sovereignty" and "intervention" are malleable and potentially can be exploited according to the intervention strategies implemented by States. When sovereignty is redefined as either "monarchic sovereignty","popular sovereignty" or "responsibility to protect", it redefines intervention.

The The responsibility to protect report was endorsed by the UN in 2005, but not any state can declare that there is an urgent need for intervention by a third state. The Security Council must be seized and there must be a UN resolution for a government to justify its intervention under the R2P. It's hard to figure out what an intervention is. Defining it in relation to war, peace or sovereignty raises the question of whether it is authority, the effective and legitimate government that endorses sovereignty.

Historical Characteristics of Military Interventionism

It is possible to analyse the emergence of the historical concept of intervention.

The emergence of interventionism

Dans quel contexte émerge la catégorie spécifique de l’intervention comme modalité de recours à la force par un État contre un autre ? Avant le Congrès de Vienne de 1815, avant les guerres napoléoniennes, le concept d’intervention n‘existait pas, il y avait seulement la guerre qui conformément à l’institution interétatique de la guerre impliquait un conflit entre deux monarques sur des questions territoriales et se soldait en général par une annexion d’une partie d’un territoire d’un État par un autre État. Avant le Congrès de Vienne, ce type de guerre d’annexion était considérée comme quelque chose de relativement normal dans les relations entre gouvernements et cela était même vu comme un mécanisme de résolution des conflits permettant d’allouer des ressources. Le principe de la « conquête territoriale » a vu réémerger la possibilité de créer à l’échelle de l’Europe un empire. Suite aux guerres révolutionnaires, Napoléon envahit une partie de l’Europe pour constituer un empire européen aux dépens de l’ordre européen. Au Congrès de Vienne, le principe d’annexion et d’intervention sont délégitimés. Il peut y avoir recours à la force entre États, mais il faut éviter les guerres comme celles du XVIIIème siècle qui se solde par des annexions. On considère que l’annexion est sinon illégitime pour maintenir un équilibre des puissances. Dans le cas du traité de Vienne, il s’agit d’un « equilibrium of power » qui est un équilibre des puissances fondé sur un certain nombre de principes, mais c’est aussi l’idée que les États du continent européen partagent un certain nombre de principes et de valeurs et l’équilibre de force entre les États est garant de la souveraineté des États contre l’oppression d’un empire. Cela suppose de limiter les possibilités d’annexion assimilée à la notion de « guerre ». La guerre n’est pas rendue illégale, mais elle est délégitimée comme institution auquel les États peuvent systématiquement avoir recours.

La perspective contre laquelle le traité de Vienne est défini, le scénario qu’il essaie de prévenir est celui de l’émergence de velléités impérialistes de la part de la France en Europe. Pour empêcher de telles velléités, on veut ancrer le système interétatique fondé sur l’équilibre des puissances impliquant l’impossibilité de conquêtes territoriales, mais cela implique aussi de s’intéresser à la nature des gouvernements légitimes en Europe. Le résultat est que ce qui a amené Napoléon au pouvoir est la Révolution française et il y aurait un danger inhérent aux doctrines libérales, républicaines ou révolutionnaires qui remettraient en question des monarchies absolues au principe d’une souveraineté nationale ou populaire. Le traité de Vienne définit le principe selon lequel les grandes puissances du système interétatique européen à savoir la Prusse, l’Empire austro-hongrois et la Russie qui formaient la Sainte-Alliance, ont un droit de regard sur les régimes politiques et les évolutions des régimes politiques des États européens. L’intervention est en vérité la conséquence de ce système mis en place par le Congrès de Vienne. Dans ce schéma ou l’annexion est limité, dans lequel on s’intéresse à la nature des régimes comme étant une source potentielle de menace pour le système international et dans lequel on veut maintenir l’équilibre des puissances va mener à des opérations militaires qui vont mener à consolider le pouvoir politique d’État reconnu plutôt que de remettre en question leur territoire par l’annexion cela de façon à maintenir l’équilibre interétatique que le Congrès de Vienne appel de ses vœux.

C’est la perspective de lutter contre la réémergence d’un empire qui va conduire à l’émergence de la notion d’ « intervention » à la fois pour empêcher à nouveau Napoléon d’émerger en France ou bien dans d’autres États européens, mais aussi pour délimiter l’annexion de la guerre. C’est à partir de 1815 et plus généralement au XIXème siècle que va émerger la notion d’« intervention » qui va perdurer jusqu’à aujourd’hui. De nombreuses caractéristiques que l’on retrouve à cette époque se retrouvent encore aujourd’hui, notamment le fait que l’intervention doit toujours se justifier au nom d’un bien général, c’est-à-dire d’intérêts qui transcendent et dépassent les seuls intérêts nationaux. La notion d’« intervention » à vocation selon le système du concert européen à empêcher la réémergence d’un empire de type napoléonien pour sauvegarder un système interétatique perçu comme le seul garant de la liberté des États européens face à l’oppression possible d’un empire unifié. C’est aussi au nom d’un intérêt qui dépasse les intérêts nationaux dans le but de respect d’un principe d’équilibre européen comme s’il y avait des principes qui transcenderaient les valeurs nationales justifiant l’intervention. Les puissances européennes ne sont pas d’accord sur les principes qui font qu’on peut intervenir dans un État tiers à savoir la Prusse ; l’Empire austro-hongrois, la Russie, la Grande-Bretagne et la France. La Sainte-Alliance étaient d’accord sur les principes qui devaient prévaloir dans le cadre de la politique d’intervention. Progressivement, les britanniques ne sont pas favorables à ce type d’interventionnisme avec des conceptions beaucoup plus libérales de la souveraineté notamment pour soutenir des révoltes populaires lorsque celle-ci sont considérées comme « légitime ». Le principe d’intervention devient un principe fortement contesté. En principe, il est permis dans le cadre du Congrès de Vienne pour sauvegarder le système interétatiques mais en même temps lorsqu’il y a une intervention concrète menée par un État, cette intervention va être contestée impliquant qu’on va chercher à nier les interventions que l’on menait en redéfinissant la souveraineté. Par exemple, pour l’Empire austro-hongrois, intervenir pour soutenir un monarque absolu n’est pas une intervention.

Le discours sur la responsabilité à protéger a pour fonction de remettre en question l’opposition entre « intervention » et « souveraineté ». Le principe de « responsabilité à protéger » dit qu’on a pas le droit de violer la souveraineté d’un État et qu’on ne la viole pas si on protège la population puisque c’est la protection de la population qui est la condition même de la souveraineté.

Les caractéristiques de l’interventionnisme contemporain

L’obligation de justifier les interventions militaires au nom d’idéaux universels existait déjà au XIXème siècle, les principes de « paix » et de « sécurité internationale » sont plus contemporains. L’imposition d’un système symbolique supérieur justifie aussi l’intervention. L’idée est que ce qui oppose deux armées sont des intérêts différents, mais que sur le principe de leur droit à défendre leurs intérêts territoriaux, il y avait un principe général. Dans les interventions cela est différent, on considère qu’il y a des intérêts supérieurs qu’on considérait violés par les États concernés et il n’y a plus de reconnaissance mutuelle symbolique.

Pour parler des opérations d’intervention contemporaine, on parle parfois de principe de « police globale ». Dans les opérations de police à l’intérieur des États, il y a l’idée qu’il n’y a pas d’autorité supérieure. C’est une idée sur laquelle il y a une continuité par rapport au XIXème siècle. Metternich, juste après la signature du traité de Vienne de 1815, parlait des interventions comme une fonction de gendarme. La Sainte-Alliance était le gendarme du système interétatique européen qui se devait de lutter contre les « bandits révolutionnaires » qui menaçaient le système européen. Il n’y avait pas d’égalité symbolique. L’ennemi est criminalisé ce qui est également aujourd’hui une caractéristique des interventions. L’ennemi n’est plus légitime, mais est plutôt un « criminel » ou un « terroriste » avec l’idée que d’un côté il y a celui qui a commis un crime contre des idéaux généraux et celui qui a commis un crime contre des idéaux.

Les obligations deviennent plus formelles avec le principe de minimisation de l’usage de la force et le principe de multilatéralisme, les populations sont devenues centrales dans la justification de l’interventionnisme. Les principes de légitimation de l’intervention se heurtent à un problème de légitimité intérieure expliquant la redéfinition de l’interventionnisme depuis une dizaine d’années qui va dans le sens de plus d’interventions aériennes.