Geography of wealth and development

The first mystery that has been explained is the unequal distribution of wealth. There are many words to say it that are usually euphemised. We will gladly talk about unequal development, we will oppose the countries of the North and the countries of the South or we will still talk about growth. We must remember the brutality of the facts, which is the question of poverty and wealth: there are poor countries and rich countries. This is a massive phenomenon that cannot be explained. Basically, we do not have a really satisfactory theory today that explains why we have rich countries and poor countries and that would explain why there are rich countries and why there are poor countries. We should try to denaturalize this representation and say to ourselves that it is a very strange and so bizarre thing that we cannot explain it. On the one hand, it is accepted as self-evident and on the other hand it cannot be explained and theorized.

What is difficult to understand is the unequal distribution of wealth in space. Not only is it incomprehensible, but it is also scandalous because the issue of space justice is a question of social justice. People are not mobile and born somewhere, which means that if there is an unequal distribution of wealth, we are condemned to poverty. This "curse" is linked to the fact that spaces are unequally rich. It is something strange, massive, that we cannot explain and scandalous. We are so used to this blatant injustice and mystery that we no longer see it by making it a central question in geography.

On the theoretical level, the persistence of inequalities, despite globalization, mortgages Ricardo's theory and the theory of comparative advantage. If there is globalization, if more and more countries are opening more and more sectors to the economy then more and more countries should get richer. The question raised is that it is the relationship between spatial inequalities and globalization? As Ricardo predicts, does globalization result in the enrichment of all, leading to a reduction in inequality, and if not, why not? To reflect on the unequal distribution of wealth is to question the recent evolution of inequalities to see what impact globalization has had.

Ambiguities of the notions of wealth and development

There are many terms used to talk about inequalities in space. We are talking about poor countries, rich countries or other scales that imply a certain number of elements. Yet it is an abuse of language because a city, a country or a region has nothing, only the inhabitants have something. A space is never rich and never poor, but in a space there are people who are rich and people who are poor. Someone's wealth is not necessarily where they live. There may be a disjunction between the place of wealth and the place of the person who possesses wealth. It is important to make the difference that we should not talk about the richness of the spaces, but about the people who live there. If we think in terms of space, a territory has nothing, but its inhabitants have. Nevertheless, it is necessary to differentiate the inhabitants between them. The issue of inequality in living standards between inhabitants is important.

Wealth and GDP

To measure inequality, figures are needed. The first available figure is gross domestic product. GDP is the sum of the capital gains produced in a given country during a given year. The idea of added value complicates matters, particularly with regard to redistribution. This indicator says nothing about the nationality of producers. If an American company produces in Switzerland, one counts in the Swiss GDP. What counts in GDP is what happens within the national space. This is a very geographical definition of production. On the contrary, gross national product refers to the sum of the added value produced during one year by nationals. We integrate what the Swiss produce at home and abroad. GNP is a less geographical concept than GDP.

GDP does not measure wealth, not production, but it measures enrichment. GDP talks about the increase in wealth and therefore growth. There is the stock of wealth that no one ever measures and that we do not know. There is the increase during the year in wealth, which is GDP, and there is the increase in GDP, which is called growth. Growth is the increase in wealth. In other words, growth is the acceleration of enrichment. Wealth is what is available in the bank account, GDP is income and growth and income increase this year over last year. Talking about zero growth does not mean that we are not getting rich; it means that there is no acceleration of enrichment. There is an important correlation between wealth and wealth, between a country's wealth and its GDP. On the other hand, there is not really a correlation between wealth and wealth on the one hand and growth on the other. The countries whose enrichment is accelerating are not the richest. The promise of compensation and levelling is not made in wealth, but in growth.

There are countries where the underground economy is very important, and there are countries where donation for donation is very important. GDP is rather a good estimate for countries with few underground economies and where the market economy occupies a large share of their economy and rather a bad estimate for countries where there is a large underground economy and where giving for giving plays an important role. What matters is the GDP in relation to the inhabitants.

Of course, what interests us is not only income or wealth, but also what it allows us to do. Like the extremely variable cost of living at all scales, it has a heavy impact on incomes. If the cost of living is twice as high in place B as in place A, the income and cost of living and the standard of living must be put into perspective. You can have someone who lives in Madagascar who has exactly the same standard of living as someone in the Massif Central or in Zurich, but each time you have to multiply the salaries to get the same thing. We must try to control this difficulty.

A first way to control it and choose an indicator. A very good indicator is the Big Mac. If we translate a salary or a GDP into McDonald's, into hamburgers, we have a good integration of the cost of living. In general, things are taken seriously and an index has been proposed which is GDP per capita[PPP]. PPP is the acronym for "purchasing power parity". We will adjust GDP per capita based on what this per capita income actually allows us to do. We will translate it into dollars uniformly and then into purchasing power parity. If with 100 euros in France we could do the same thing as with 10 euros in Madagascar, we will correct the income and we will consider that the 10 euros in Madagascar are worth as much as the 100 euros in France. The cost of living happens to be very high where wages are high. There is a very good correlation between wage levels and the cost of living; conversely, the cost of living is very low where there is very little income.

It is a very good correlation, but it is not a perfect correlation. If the two varied, in exactly the same way, everyone would have the same standard of living everywhere. This idea that there would be a positive correlation between the cost of living and incomes suggests that the GDP gaps that can look very brutal when measured without taking purchasing parity into account will be reduced if purchasing power parity is taken into account. Levelling out is going to happen: all poor countries are countries where the cost of living is low, in purchasing power parity this will overestimate incomes; on the other hand, rich countries are countries where the cost of living is high and this will reduce income in terms of purchasing power. Indeed, when we move from a per capita GDP map of the world to a purchasing power parity map of the world, there is a reduction in the gaps. So, the differences in living standards are actually less glaring than the differences in GDP because the cost of living bias intervene.

A second element to be taken into account in this inequality reduction effect is that GDP most certainly reflects better the real economy of rich countries than of poor countries. In poor countries the non-market economy is often important with often the grey sector, a black sector, an underground economy that are not taken into account by the GDP whereas more often in rich countries, this share is smaller because people are more virtuous, but also because there will be more control. Beyond one of those underground markets that are not taken into account by GDP, there is the fact that in rich countries, the market share is larger than in poor countries. In poor countries, self-help systems and self-consumption systems are more important and obviously this is not reflected in GDP. Self-help networks, family networks and clan self-help networks are also very important. There are many loans, for example, that will be made through clan systems that will not be made by banks and therefore are not included in GDP. This will therefore also compensate for the inequalities between rich countries and countries measured with GDP since this measure of GDP is a very large share of the economy in rich countries, but a fairly small share in poor countries. This is a rather optimistic conclusion which is that the inequalities in terms of GDP per capita which seem glaring are in fact less important than we believe if we take into account the PPP corrections and if we take into account the importance of the underground economy and self-consumption and mutual aid circuits.

In the late 1980s, concerns about the pervasiveness and importance of the GDP per capita indicator began to emerge. In part because of the points we have raised, but also because we are making it play a role that should be its own, GDP, stricto sensus, is only an economic indicator and it is not the only economic indicator. Why is GDP per capita used? Is it to measure countries' economies?" Yes" of course, compare it, measure growth, "yes" of course. Behind it, there is something else with the idea that we would like to obtain an indicator that would make it possible to measure the success of societies, the improvement of situations, progress and development. The countries will be ranked in order of GDP per capita, in ascending and descending order. Obviously, making an economic indicator that is only an economic indicator play this role is insufficient. This is insufficient because to measure the success of a society where the improvement of a situation, we agree that the measure of the economy on the profit of income appreciation is insufficient. One could say that these elements are variable in which we speak. For example, some cultures will attach greater importance to the religious dimension, to metaphysics or to the spiritual. The goal in these cases is to obtain criteria that are universally recognized by all. It is clear that GDP per capita is a criterion recognised by all. All other things being equal, it is better to be rich than poor. We all agree that all things being equal, it is better to be healthy than sick.

Any other indicators?

A third element that will be taken into account is schooling. All other things being equal, a society is more successful if it has a good level of education, that is, if it has a large proportion of its population with a good level of education. Health, education and income will be included in an index that we will call the HDI, which is the human development index.

One third of the index consists of GDP and more precisely GDP per capita in purchasing power parity, which already corrects the dimension of income measures to measure living standards. The second demographic factor is health, the indicator that is, life expectancy at birth. All other things being equal, it is better a country where life expectancy at birth is high. Life expectancy at birth has a very intuitive meaning which is how long we can expect to live. On average, a life expectancy of 80 years means that on average we will live 80 years in a society. In fact it was, it is more abstract than it seems. It is calculated by taking the mortality rates of each age group today. This amounts to applying today's mortality rates to future generations. The "education" criterion is the average level of education. Each criterion has a third: economy, health, education.

If we take all three, it's because they're not perfectly correlated. If all three varied in the same way it would make no sense not to serve. If GDP increases, very often the standard of life expectancy increases and then education increases, but with small variations.

The term "development" means that if a society is considered developed, it has a high GDP per capita, a high life expectancy and a high level of education. If we call this "human development", we must appreciate that this index is composite and that it no longer has any intuitive meaning. What's he measuring at the bottom? We don't really know. We will replace the world rankings made in the country with GDP per capita with the HDI ranking. There are examples of countries with which, when we move from GDP to the HDI, will lose places or gain places. A country that rises in the hierarchy, that gains places, when we move from GDP to the HDI, it means that society is too developed for its wealth, or to put it another way, this society knows how to use its income very well to develop. It is a country that transforms its wealth very well into development. A country that falls in the ranking when we move from GDP to the HDI, it means that taking education and health into account leads it. To put things differently. This means that it is having trouble transforming its wealth into development.

Some countries have a different GDP, but a comparable HDI: Spain and Singapore. The HDI is almost the same at 0.89 which is a very good HDI while Spain's GDP is 16000 and Singapore's GDP is 28000. There is a big difference in GDP, because in Singapore GDP is almost twice as high as in Spain. Singapore is twice as rich. Yet Singapore and Spain have the same HDI. This obviously means that the scores for Spain for life expectancy and for education are very good and that everything else being equal, in Singapore, they are mediocre. In other words, Spain is very good at turning its relatively meagre wealth into development and Singapore has wealth, but this does not really translate into something of the same level in life expectancy or education. Another example is that of Georgia and Turkey, which have the same HDI in the order of 0.73, whereas in Georgia it is 2000 for GDP per capita and 6300 for GDP per capita in Turkey. That is, with three times less wealth, Georgia has the same level of development as Turkey. Turkey therefore uses its income very badly in terms of human development.

The door was open with the HDI to consideration of non-economic factors. Economists and econometricians have suggested that things are missing in the HDI. For example, an index has been proposed which is the GDI which is the gendered human development index integrating a fourth factor which is inequalities between men and women. One can imagine that, all things being equal, a society where men and women are equal is better. Not every country in the world would sign this idea better. Obviously, this is an index that has been imposed by Western countries.

A second element is the issue of the poverty line. HDI, GDI and GDP are averages. When we say that we have, for example, a GDP of $14,000 per capita per year, that means that the average disposable income for each inhabitant is $14,000. It is possible to find oneself in a situation where absolutely no one earns $14,000, nor an amount between $10,000 and $16,000. This average of $14,000 would actually mean that a large part of the population is poor, so earns $5,000 a year and a part of the population would be very rich and earn $100,000 a year. This may well not correspond to any reality in the life of the country in question. We can imagine two configurations:

- a configuration for a country where the GDP per capita is $20,000 and everyone wins $20,000.

- a configuration where the country has the same GDP of $20,000 per capita and per year, but where this average hides deep disparities between a large part of the population, i.e. 90% who earn $5,000 per capita and per year, and a small part of the population, i.e. 10% who earn between $40,000 and $50,000 per capita and per year. We all agree that the second company is less successful, less successful and less developed than the first.

One way to address this issue of inequality and poverty is to include in the HDI the number of people living below the poverty line. The fewer people living below the poverty line, the more developed society becomes. Trying to define this poverty line is complicated because it depends on purchasing power parity and PPP is relative. To say that poverty or wealth and when compared to someone. The dollar poverty line per day will not be the same in all countries.

Green GDP" was first proposed in the 1990s as environmental GDP. These environmental GDPs assume that it is not because GDP increases that it is necessarily a good thing. For example, there is a boom in the cigarette industry that is producing growth. Should we welcome the increase in GDP that is linked to the development of the tobacco industry? The increase in GDP is not only linked to the sale of cigarettes, it is also linked to the fact that many people will develop cancer, which will require hospitals, ambulances and scanners being a very good thing for GDP. There may be elements in GDP that are less positive than they look because money has to be spent. The idea that tobacco costs society something is not clear because if we take into account avoided health expenses as well as pensions that makes money saved. Nevertheless, this way of reasoning poses problems. Beyond the question of judgment or the moral question, we could say that everything society will spend to treat people who have smoked, all those people who have chronic bronchitis, who will take time off and will not produce is a cost.

A defensive spending activity is in a way the cost of outsourcing a production. These costs must be taken into account. Proposals have been made to remove all defensive spending from GDP. It is very complicated to agree on what a defensive expenditure is. A second problem with natural resources is that the cost should be included in the exploitation of natural resources and especially non-renewable natural resources. This is not only because in the future there will no longer be any, but it is also all that will have to be paid and invested to find alternative materials and alternative energies, for example. For example, the fact that we exploit oil at very high levels is what forces us to invest in solar energy or biomass. It is a kind of defensive expenditure, because a country that depletes its natural resources increases its GDP even though it is not counted positively. A developed country is a country that draws as little as possible from its renewable natural resources. All other things being equal, it is better not to touch too much and not too quickly your renewable resources. However, GDP says the opposite: the sooner wealth is exhausted, the higher GDP is. It is proposed that the cost of future depletion of natural resources, especially non-renewable resources, be successfully deducted from GDP.

For renewable resources, this is even more complicated. What is the cost of the extinction of a species? We are not able to evaluate them, but they are in principle almost infinite and potential. On this basis, the IBED, which is the index of sustainable well-being, was constructed. Sustainable" referring to the issue of sustainability highlighted by the Brundtland report which is that a society that ensures the satisfaction of its members without mortgaging that of future generations. IBED is complicated and also very contrintuitive. GDP, which includes life expectancy, education level minus productive expenditure minus resource destruction, is beginning to be very abstract.

The ecological footprint, on the other hand, is an interesting clue. It has a meaning that is very clear and intuitive. The ecological footprint of a given population or city, for example, is the square metres needed to meet its needs. Geneva's ecological footprint is the surface area that Geneva needs to ensure its consumption. How many square metres are needed to provide us with energy and food, water, where we put our waste with the idea that the ideal society is one where its ecological footprint does not exceed its territory. We start to have a problem when the ecological footprint of a population exceeds the number of square metres on which it is located. However, as our needs grow faster than our techniques, the ecological footprint has doubled in 40 years. This means that we need more and more space to meet our needs.

We have also considered social GDPs that take social criteria into account. The economic well-being index was thus produced, which will comprise four dimensions:

- current consumption;

- stock accumulation: of all the criteria taken into account so far, none measures wealth, but takes heritage into account.

- inequalities ;

- economic security, i.e. the assurance that economic actors have about their future, such as the risk of unemployment.

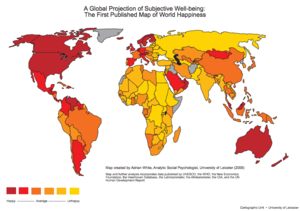

These attempts are laudable, because they make us think about what it produces, how the economy participates and in what capacity and to what extent. There are things we still miss. One can think of the index of loneliness. All other things being equal, is better a society where people are not alone. It is possible to make indices that measure the number of our friends, the people we can count on. This is not only important in terms of psychology or emotional comfort, it is also partly a question of economic security. With societies where many people suffer from isolation, there would be something wrong with their development. We can also talk about spirituality. It would be better to have a spiritual life, an intellectual life, an artistic life than to be immersed in the most vile materialism. We can go so far as to measure happiness and say to ourselves that what we should replace the GDP map with is a map of happiness.

This map is the map of happiness on a global scale. The whole problem is how to measure happiness. Happiness is subjective, there is no difference between being happy and feeling happy. Happiness is something you feel. On a self-declarative basis, we swim in happiness in North America, the United States and Canada, Australia and New Zealand, Colombia, Sweden, Norway, also Mongolia. This raises problems of standardisation.

The countries with the highest per capita suicide rates are the countries where people are happiest. One might objectively think that this is not really a sign of happiness. Being "rich" or "poor" is a comparison to being happy. And if suicide was a luxury for the rich. Suicide would be a bourgeois luxury. People who are caught up in life's difficulties may have less metaphysical anxiety, less trouble and less depression. We observe that where we commit suicide, it is where there is wealth. The idea of the declaration may be a good solution, but with a lot of bias since everyone should say the same thing. GDP remains the most reliable and comparable figure even if it is unsatisfactory.

Major inequalities

The big question is the spatial question as to whether GDP is evenly distributed in space. Statistical indices allow this to be done by taking each spatial unit to calculate the standard deviation or Gini index to calculate the equality or inequality of the distribution of a variable within a population.

Maps

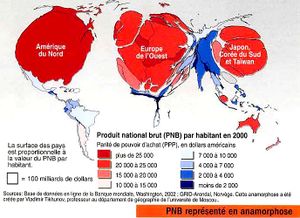

In geography, maps are used to show the extent of "damage". This map shows us GDP per capita in purchasing power parity. Four categories of countries appear, the richest countries between 24000$ and 60000$ per year, the poor countries between 600$ and 4000$ and then an intermediate category between 4000$ and 24000$. There are statistical rules in order to constitute these classes. For example, we did not ensure that classes were of equal amplitude.

The first remark is the contrasts that are major. What is important to us is to compare classes. There is a quarter of the countries where the GDP per capita is below $40,000 and then another quarter in the world where the GDP per capita is above $25,000. That's a difference of one to five. There are inequalities and they are major. Another thing is interesting. There are grouping effects that in geography are called spatial autocorrelation. A given country is very likely to have a GDP comparable to neighbouring countries. In other words, a country is very likely to have the same colour as its neighbours. A large package appears throughout Africa which is very homogeneous, in South America, North America, but also in Europe. There must be a geographic law, a geographic rule behind it. If there were none, we would have a cheerful mixture of all colours within each continent, but that is not the case. What makes all these countries in the poorest class or the richest class? Wealth contrasts are very strong on a global scale and they seem to respond to distribution rules. Quite rare are the places where one sees at a border a very rich country which côtoie a very poor country.

This map follows the principle of anamorphosis. The size of each entity is not proportional to the area of this entity on the real space, the area of the quantity is relative to another variable, in this case the population. The densely populated countries will see their surfaces represented in large and the poorer countries will see their surfaces in small. Are the contrasts stronger or weaker when moving from GDP to the HDI? We cannot compare because GDP goes from $600 to $60000 and if poorer countries get poorer, richer countries get richer. The poorest country has an index of 0.27 and the richest country has an index of 0.94 is meanwhile, there are six classes. A country with an index of 0.4 cannot be said to have a human development index twice as good as a country with a development index of 0.2. We can't compare them. Two contiguous countries are likely to have a comparable HDI. There does not seem to be a clear correlation between the country's population and its wealth. It cannot be said that densely populated countries are richer or poorer than sparsely populated countries. There is a great situation of inequality on a global scale and distribution rules.

With this map, the larger the country, the greater the GDP per capita. The contrast with the two previous cards is strong. On a global scale, between the continents of the great, there are great contrasts of wealth.

This map shows us the GDP by region Europe. We change scale by considering a continent. On this scale, is there again a spatial autocorrelation phenomenon? This map was made from deviation from the mean. In the grey class, we see regions that are in the European average. The countries in grey are almost in the average while the countries in yellow are a little bit above the average. There is a gap of 3 to 6 between the richest and poorest regions. Compared to the world, this is nothing at all. In other words, the wealth gaps between European regions are 10 times smaller than the wealth gaps between the countries of the world. We are dealing with a phenomenon that is not an invariant of scale. It is an economic, social, physical or climatological phenomenon that itself has some scales that we observe, it is a fractal. If we change scale, the inequalities disappear. There is still a phenomenon of spatial autocorrelation with regions that touch. There is a spatial rule, it is not distributed in any way. There is a regularity just like on a world scale.

It's a map of France. The map that France has is 36000 cities. This map shows the rich regions in warm colours and then the poorest regions in the coldest colours. In the fuchsia area, the inhabitants have a third more income than the French average, while in the green zone, this means that on average, people are 30% poorer than the national average. The gap between the richest and poorest communes within the French area is 1 to 2. There is a fairly fine level of inequality. This is not distributed in any way, there are also rules of spatial organization at this scale.

Whether we consider the world, a continent or a country, there are geographical rules for the distribution of wealth. On the other hand, the closer we look at poverty, the less apparent the inequalities are.

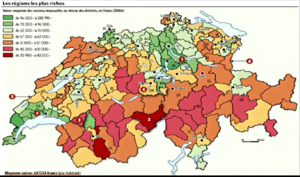

This map is the average taxable income. On average, the taxable income in Switzerland is 68,000 francs per inhabitant, in the poorest cantons between 20,000 and 43,000 francs, in the richest cantons between 96,000 and 338,000 francs. The contrasts between the districts of Switzerland are stronger than the contrasts between the French communes. There too, there is a geographical rule, because we see that the poor regions are the mountains and that the rich regions are on the plain.

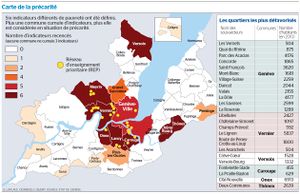

Detroit is a caricatural example of racial segregation. In downtown Detroit, there are between 80% and 85% of the population while there are almost none in the suburbs. The suburbs are rich white with jobs and the downtown is poor, black and there are no jobs. What is the average income level in the city of Detroit? Less than $17,000 per capita per year. In the richest areas of the agglomeration, the average level is over $57,000. That's a difference of one to three. This is a larger gap than between French municipalities, but it also works for French cities with significant wealth contrasts. There is a break in the scales since there is a very strong inequality between continents, strong between countries, weak between regions of a country and again strong on a country scale. It's a center-periphery model.

There are geographical rules at all scales: at all scales of wealth and poverty there is a tendency to group together referring to the phenomenon of spatial autocorrelation. Major inequalities are at the global scale between continents and at the local scale of a city. The methodological problem with the theoretical problem is that the inequalities that obsess us are international inequalities. The question raised is why inequalities are more marked at some scales than at others?

The scales of inequality

The task of geography would be on two levels: on the one hand, to explain why it does not happen in the same way at all scales and then to take into account the phenomena of organization of space at these differences scales. There would be two main hypotheses:

The first would be to say that what explains the results may not be economic processes as such, but political processes of compensation that would be at work. The idea being that there would be in the nature of the geography of space the fact of being marked by very strong contrasts of development and that these would be compensated at certain scales, but not at others. It is possible to envisage that if the market, for example, produces local equality, other systems may appear as donation-for-gift systems or redistribution systems that will compensate for the inequalities set up by it. There would be flows of wealth that would come through a sort of call from the void to change the inequalities created by the economy. For example, in the context of redistribution, there must be an authority that imagines an authority that is involved in the respect of social justice and spatial justice that would like all parts of the territory under its control to benefit from an equal situation. We can imagine, for example, that a state would want all the regions it comprises to be treated on the same economic footing, in other words, that there are as many hospitals, as many universities and as many fire stations, etc., even though the resources of each of these regions do not necessarily allow it. We cannot accept that in certain regions, safety is less secure and education is less good or health is treated less well. The State will intervene by taking wealth in regions where there is a lot of income and will transfer this money to invest in low-income areas. For example, a lot of money is being made available in Geneva and Zurich and instead of building more hospitals in Geneva and Zurich, where the medical supply is already excellent, we are going to put these hospitals in Ticino where the income is less important. We're operating a transfer.

These wealth transfers can compensate for spatial inequalities. The same applies to Europe, where there are very rich regions and poor regions. At European Union level, there are procedures which transfer wealth from rich regions to poor regions in the form of levies on the one hand with taxes and charges and subsidies on the other hand with investments, but also with aid. One could therefore imagine based on this hypothesis that the scales with the least inequality would in fact be the scales with the best compensation circuits. What needs to be explained is not the spaces where wealth is unequal, but what it fails to explain are the spaces where there is not much inequality. What should be explained is less inequality than equality and the question of at what level and how spatial inequality compensation systems are most effective. For example, at the life scale, are there good systems for compensating for spatial inequality? The issue is a political one. It deals with two points. The first is on the existence of these authorities, there is no global authority for example. Second, the biases taken in knowing the ideological, political and economic choices of the authorities. For a city like Geneva, for example, isn't the issue of inequalities in wealth between neighbourhoods a priority? On a regional scale, this is considered scandalous. Why does social and spatial justice not work in the same way at all scales? The idea that problems of racial justice can be solved through spatial justice is not obvious either. The idea that the solution to a social problem has a spatial solution is not self-evident.

A French problem is that of "large ensembles". For a long time, it has been considered that to solve the problem of "large complexes", cities and suburbs, the solution is in the hands of urban planners who must find urban solutions with new building designs, architectural solutions. It's not obvious. There are other questions to ask in relation to the postcolonial period, in relation to the place of communities in France, in relation to the integration of the younger generations which are not urban issues. Social justice and spatial justice must be distinguished, but sometimes the two work together. If you consider separating the Israeli-Palestinian situation, it is clear that it is a situation that cannot be resolved if it is not first resolved spatially. That doesn't mean it's the only problem. Not all spatial inequalities in the redistribution of wealth are necessarily a social problem. It is not necessarily scandalous.

At these different scales, we see that social justice and spatial justice do not quite overlap. Because of this, it is logical for local communities, depending on the scale at which they are placed, to think that it is not always necessary to compensate for spatial heterogeneities of wealth. There are scales to which it is absolutely indispensable and then others where it is not. A community's ability to compensate for unequal distribution of wealth depends on two criteria:

- is there authority on this scale?

- if such an authority exists, does it consider it legitimate and a priority to settle this heterogeneity?

It seems quite obvious that the weakness of regional inequalities within Europe is one of the effects of European economic policy.

In Germany, before the fall of the Berlin Wall, before 1989, there was obviously a very strong contrast of wealth between East Germany, the GDR of communist obedience and the FRG allied to capitalism. One had experienced a good level of development and the other not with a large difference in GDP. At the time, it would have been unthinkable to transfer wealth between the West and the East to bring the two to the same level. There was no community between East and West Germany and this lack of community made it impossible to make compensation in the form of transfers in a redistribution circuit between East and West Germany. In 1989, the wall fell to the great general surprise. A few years later, the two German states became one, and so at that time, of course, a community was formed. This community, which makes all Germans feel that they belong to the same legitimate nation, whether from the East or the West, generates transfers. At this time, transfers will be initiated so that the level of wealth transfer between East and West Germany is now low. We didn't totally catch up, but there was a very strong catch up. Caricaturally, West Germans paid a lot of taxes to finance East Germany's catch-up. They considered it "normal" because it made sense for their national community to do so. It worked less with Greece, because it was less obvious to convince the Germans today to do what they had done for Eastern Europe to do for Greece because the sense of community does not exist.

It is very clear how issues of community and authority play out at some scales and not at others. The weakness of inequalities between the regions of Switzerland against the regions of France can of course be explained by the role of the two governments in their planning policies to succeed in limiting immigrants.

The only explanation given for inequalities at first is that wealth accumulation is due to certain causes and that these causes act differently according to location or that development implies resources and that these resources are unequally distributed in space. The problem is reported further on. To put it very caricaturally, one example is that what allows development is the temperate climate. As a result, this factor explains the difference in wealth between the countries of the South and the countries of the North. It would be necessary to find a factor of resources that would explain the development and that would be located precisely where the development took place is absent from the places where the development did not take place. The heterogeneity of the distribution of wealth is linked to an unequal distribution of these explanatory factors.

The third hypothesis is the idea that diffuse wealth, that there are contagion effects and that this diffusion is hindered by the obstacle of distance. This could explain why fireplaces develop, fireplaces of capital accumulation, instead of spreading everywhere in space in the image of a pocket which would contain balls which one would open on a waxed table and which would leave in all directions. This pocket of marbles that we open, falls as on a sandy ground and remains in the same place. This explanation is not at all the same as thinking that it is the terrain itself that has a different potential for log formation. The marbles all fall in the same place and will not diffuse in the same way. We can also imagine that it is the gutter system in the ground that causes the logs to be channelled in one direction and not the other.

If the first explanation is a compensation system, the second explanation is the property of space. These properties of space would be of a different nature:

- the heterogeneity of space: resources and causes are not distributed in the same way ;

- Opacity: that is, the brake that space is heterogeneously, isotropically, the brake that it exerts on the movement of wealth.

Explanatory factors

We must come back to an opposition already set up previously on zero-sum, positive and negative games. It is necessary to return to these three ways of considering international exchanges and to see to what extent they lend themselves to different explanations of the contrasts of wealth in space.

Trading as a zero-sum game

First, there is the idea of international trade as a zero-sum game which is that international trade does not create wealth. If international trade does not create wealth, or even destroy it, the enrichment of some is only the counterpart of the impoverishment of others. In other words, everything boils down to the circulation of wealth. Rich countries are countries that manage to capture wealth during their circulation and poor countries do not. We are in the context of exogenous explanations to development, that is, explanations are external to the country concerned. A country is not rich because it has wealth or resources, it is rich because it has managed to capture those of others. Such a country is poor because its resources and wealth have been plundered and captured. Thus, the enrichment of a given area depends on the ability of the society concerned to be part of an economy, an economic circuit and to capture the wealth that passes through this circuit, but also on its ability to prevent others from doing the same. This rather negative view of international trade had been theorized by mercantilists: trade enriches no one, but just redistributes wealth. If we want to get rich in international trade, we must export as much as possible and import nothing.

Marxist, imperialist, terms of trade, new national division of labour and alterglobalization theories have in common the idea that international trade is something to be wary of because of this capture. For all these theories, wealth accumulation is linked to captures that are exogenous sources. The enrichment first of England, then of the United States and Europe, and finally of Japan would be linked to the way in which these spaces, one after the other, drained wealth from London, Paris, New York, etc. into their immediate environment, then quickly on a world scale. This is something that seems visible when one visits these cities, all the money was produced there. This is even more visible in London where the imperial dimension is evident, it shows that London is an Empire capital through the nature of the economic activities that were important and also through the urban setting. An accumulation of wealth that occurred in London results from the fact that, first the British crown and then the City, managed to drag wealth that came from all over the world and of course this is linked to the British Empire. We cannot help thinking that this accumulation of wealth in London is there to counterbalance the things that have disappeared, the gaps and emptiness in the countries that have been exploited.

The idea of the circulation of wealth is that the accumulation of wealth in some places is linked to the fact that it was looted elsewhere. This idea also makes sense at specific moments in history when we see the mines of South America being emptied and the coffers of the great aristocrats or the great kings of Europe, Spain and Portugal being filled. There is also much talk of looting economy when natural resources are treated in this way. This is what the conquistadors did, they arrive in Lima, in Mexico City plundering the wealth and then repatriate all the profit to their country of origin. What we learn from alterglobalist theories, imperialist theory or the theory of the new international division of labour is that there are less clear hidden forms of this kind of exploitation today. From the moment we accept this idea, the solution to fight against wealth gaps is not to participate in international trade, but to refuse to participate, especially if we are poor.

It is a strange coincidence that the countries that have always pushed the most for international trade are the richest countries and that the countries that are reluctant to trade internationally are countries that face this competition and commercial aggressiveness. To withdraw from international trade, one must live in autarky or trade only with countries with which one is not in competition. The countries of the Comecon of the former economic community traded with "sister countries" in a form that is very reminiscent of giving for giving. This referred to the idea of the nobility of exchange between partners who are symbolically close. At the time, it was thought that if these countries opened up to the international market, their wealth would be plundered as part of the commercial exchange that would benefit the capitalist countries.

The first solution is autarky, the second solution is to reserve trade for sister countries, a third solution is based on overprotectionism and an industrialization strategy by import substitution.

Import substitution industrialization strategies have been used extensively in Korea, for example. The idea is that because of increasing yields, the United States or Europe are able to offer relatively cheap, good quality cars on the Korean market. If Korea wants to start a car, it will do so at the start without much know-how and by producing a fairly small number of units in the first years. So the cars that the Koreans are going to produce are going to be cars of poor quality and expensive. Koreans will prefer cheap cars, which is a bad thing for Korean industry. This is what Krugman's model of locking in time and space provides comparative advantages. If it is not possible to develop the market because of unfair competition and increasing yields, it is necessary to leave the market, for example to ban the import of American cars. Then Koreans would buy expensive cars of poor quality. This is in effect subsidizing the auto industry by consumers. Instead of buying cheap American cars, they will buy expensive Korean cars. This blockade will be maintained for 10 years, after 10 years, the industry will have increased its production and the Koreans may have made progress and, at that time, they will be able to produce cars that will be as good and as cheap as Japanese cars or American cars. Only then can we open the market. The term industrialization through import substitution means that instead of importing, we will produce industrially to meet the demand that was previously met by imports. We must play on demand and this demand, instead of satisfying it through imports, we will satisfy it through local production. Space and product lifecycle locking refers to the issue of technological innovation. This means not only withdrawing from the market, but also withdrawing from international law in a certain way.

The role of development aid in addressing spatial inequalities is a beautiful subject of debate. The solution would be to make, that the flow is reversed and to make a part. One of the big arguments against this is that development aid is a "bandage on a wooden leg". The perverse effects of development aid policies are indeed very significant. Perhaps the best way to lock someone in poverty is to lock them in charity.

From the moment when we think that inequalities in wealth are linked to the effects of capture to the fact that when an economic circuit opens, flows in this economy will succeed in monopolizing the wealth that passes with the direct consequence that in other poles there will be impoverishment. In this case, the explanation of inequalities in wealth is not economic, but political, i.e. the effects of concentration of inequalities of scale in space are explained by the concentration of powers and by effects of domination or effects of hegemony. Rich countries are countries that have had the power to monopolize the wealth that has circulated and poor countries are countries that have been looted. The map of development inequalities largely overlaps with that of colonial empires. Colonization is a past that has not passed, traces of which can still be seen today.

The poverty that is still rampant in these countries, it is a hypothesis envisaged, is also attributable to the people who live there. This is a point that has been theorized a lot. One often hears that an explanation for Africa's sinking into poverty and colonization, for it would be countries martyred by colonization through on the one hand the Atlantic slave trade, plundered natural wealth and then also an absurd fragmentation of the political space across colonial borders whose only purpose was to divide and conquer and from which it results only chaos and violence. At the same time, it is possible to say that this vision of things which consists in making the white man carry a burden which is not that of civilization, but that of colonial guilt still poses problem since it is once again to consider that, as ex-President Sarkozy said, the "black man" has not yet entered history enough. Third worldist claims that responsibility is the legacy of colonization once again deprive Africans of their destiny in the sense that they are even denied responsibility for their present. Many other analyses will on the contrary show the responsibility of African elites in the flight of capital, in the refusal to invest, in nepotism, in corruption and the role and their responsibility in these countries for 50 years have still not come out their situation.

From the moment we are in this paradigm, which is a rather negative paradigm of looting effects, the only solutions are to fight or try to compensate for it. That is not the dominant ideology. It is the ideology of many "left" intellectuals, it is also the ideology of many alterglobalization movements, but it is not the ideology of the major international organizations that decide like the WTO, the World Bank and the major States that decide international agreements. There are very few countries that have led this kind of thinking.

Exchanges as a positive sum game

The prevailing ideology is that of exchange as a positive sum game. It works like an ideology. We are in a frame of thought where exchange produces wealth. The exchange allows specialization and authorizes the production of wealth. This type of development is not exogenous, but endogenous. It is the capacity of certain countries to specialize and open up to trade, to enhance their comparative advantages or to implement their increasing returns.

We are in the context of the deterministic explanation of development, which attempts to identify a map that would be ante-economic in order to explain the contrasts in economic development. Some countries had a capacity for development, a predisposition to development and then others did not. Once mapped, these predispositions will help us understand the resulting map of wealth accumulation. It must be clearly understood that, initially, if we follow Ricardo, it is not at all a question of mapping the comparative advantage since all countries have a comparative advantage. We should try to map the differential in the capacity of countries to exploit their comparative advantage since they all have one. While all countries, according to Ricardo, have a comparative advantage, this does not mean that they are equal and that they are all producers of wealth, development, added value and growth. What is interesting in this framework of thought is the idea that basically development, industrialization, wealth and growth are normal since everyone has a comparative advantage. What is abnormal and worth explaining is not wealth, but poverty. Consequently, we must not look into the history of the richest societies that have become richer, but we must look at what is preventing poor countries from becoming richer. This is reasoning in terms of blocking.

Many of the economic theories of development and international trade will try to describe the blockages with more or less finesse. A very fashionable theory in the 1960s was Rostow's theory of growth gaps, which had formulated the "take-off theory". This theory is interesting historically. Rostow's idea was that he had looked carefully at the economic development of Europe, England and the United States and he had spotted that he had five successive stages in development. These stages were marked in the middle by an acceleration phase. If you look at the production figures, for example the prices, you could see warning signs just before the takeoff and see that the take-off phase had taken place. There is a phase of high stability with much wealth and a high growth rate being the mode of economic development. Every country will experience this type of economic development. It is a transitional model. The transition is very important in the history of western sciences and also in the history of social sciences. This is the truth of the demographic transition. Demographic indicators are, for example, the fact that the birth rate is starting to fall, that mortality is starting to fall and that it will take off. These theories are not deductive theories, but they are empirical theories based on the experience of observation, on what has happened, but which have been observed. The idea was that this model was universalist, that necessarily all countries would follow the same path, that demographic transition and economic growth would follow a steady path, a path that could only be taken in one way and in one direction. If South Korea wants to industrialize, it will have to do as England did in the 17th and 18th centuries. That is not how it happened. There is not just one model, there are several voices, but it is not necessarily inevitable. In other words, there is only growth, but growth is not inevitable. So the blockages wouldn't be a moment like for Rostow.

Another interesting blocking theory put in place by Nurske is the vicious circle theory of poverty which is therefore much more based on a society in its capacity. A society that invests little is a society that produces little and makes little profit and locks itself into poverty. This idea explains a blockage in the vicious circles of poverty and the virtuous circles of wealth. There is the idea comparable to these two modes of being economic with a "low regime" which is poverty with its vicious logics and circles and then a "high regime" of wealth with its virtuous circles which makes it maintain itself, but no way to pass from one to the other. These theories make growth seem normal and basically seek to explain the lack of growth describing processes, but they do not really give the causes.

We have to go further. We went to look for three types of explanations:

- the first type is physical demographic determinism;

- the second type is social, historical and cultural explanations;

- the third type will return to Krugman are the increasing yields.

Natural environments

There is the issue of the natural environment and the environment. If we were able to explain inequalities in resources and wealth through the natural environment, geographers would be very high up in the university hierarchy and this would be a very guilt-free discourse. The natural environment is not us, perhaps god and therefore human beings are not guilty of inequalities. This explanation is reassuring especially for the rich. No link has been established between this type of natural environment and then between wealth and poverty. These two phenomena have nothing to do with it. For centuries and millennia, this idea has had very different names. Among the Greeks, we also talked about climate theory, under Montesquieu and Bodin and then we talked about geographical determinism or environmental determinism. The idea was simple: human geography was explained by physical geography. There would be countries that have good natural resources and become rich and countries that have few natural resources and remain poor. This idea has been undermined quite recently since the 1960s and 1970s and not only by geographers.

A first argument is that there are no natural resources. On the one hand, a resource meets a need and needs are socially constructed. The first question is: are there natural needs? A resource that corresponds to a social need is not really natural because it is only natural with respect to a specific need. This need is also linked to technological capabilities. In the context of technological change, some resources are becoming obsolete. It is always natural, but it is no longer resources. What determines a resource is social, economic, political and technological. There are no resources in which there is always culture, politics, economics and technology. In a way, oil is invented, it is not a natural resource. As long as someone had not invented the explosion engine, we would not know what to do with oil. It takes a very important technological convergence for oil to become an interesting resource. This convergence is not only economic and technological, but also cultural. What constitutes oil as a resource are societies. This argument is essential because it means that nothing is ever given in advance. Perhaps if we want to reverse the logic, we could say that the rich countries are countries that have succeeded in inventing their natural resources. To put it less provocatively, rich countries are countries that have successfully transformed elements of their environment into natural resources.

The second point is that if there had been a link between natural resources, their exploitation, and enrichment, we could follow the accumulation of capital depending on where we operated a massive exploitation of this natural place. The richest regions would be the regions where natural resources have been exploited the most. The capital, the profit generated, the capital accumulated during the exploitation does not remain on the spot. The pioneer fronts, the mining regions, are places deserted by capital that has invested in large centres and capitals. For example, the wealth generated by the Brazilian pioneer fronts can be seen in San Paolo.

The third reason for doubting this link between natural resources and wealth is the lack of correlation between the two. There are too many counter-examples. There are many examples of countries that are very rich in natural resources and have not seen any economic take-off. On the other hand, there are countries with very few and very few natural resources that have experienced significant development. The exception is pension savings. It cannot be denied, for example, that the wealth of the Gulf countries is linked to oil. The choices Dubai is making in Qatar show that they are thinking about post-oil and trying to transform their economy into something other than a rent. Natural resources do not last. It is not natural resources that we will understand the contrasts of wealth and development.

The other side is the issue of constraints, the issue of risks and the issue of hostile environments. There are hostile, difficult, complicated and other environments that are more conducive to human development. There are hostile environments and epidemiological environments that are less hostile. If a country has malaria, cyclone, earthquake, volcano, 40° in the shade, humidity at 90%, the constraints are such and the environment so much so that it is not possible. It is a very old idea and it is reversible. The reason why we developed in temperate environment is difficult because we have seasons that change, sometimes it is cold, sometimes it is hot, the earth does not nourish easily, it is necessary to develop a civilization, a technology and a hierarchical society. The deterministic fact works both ways, but logically it is not to his credit. This is not to its credit either, and it always comes to the same conclusion, that the intertropical zone is condemned to poverty, underdevelopment and will never come out of the "cave age"; on the other hand, the temperate zone is condemned to civilization, progress, development and wealth. This idea can be found in the theory of climates, especially among the Greeks in 500 BC. The perception of our environment is linked to our culture and our expectations.

If there is on the one hand the question of natural resources, on the other hand there is the question of constraints. The idea of constraints was often evoked as for resources. An attempt was made to explain that countries with many natural constraints were unable to develop or that, on the contrary, countries without natural constraints were unable to develop. The first is the idea that there are hostile environments or environments at risk, since the inhospitable nature of an environment is always in relation to certain types of life and therefore in relation to a point of view that is often external to it.

Just as there are no natural resources, there are no natural hazards either. A purely natural risk can never present a danger. One of the major problems related to natural hazards are hygiene issues or epidemics that occur after major disasters. These epidemics or hygiene problems are often linked to human concentrations. Hazard is nature in expression, but a society's vulnerability to it is always a social, historical, economic and political construct. What in geography is called a "risk" is the conjunction of hazard and vulnerability. To reduce risk, not much can be done about hazards, but much can be done about vulnerability reduction. On the one hand, we proclaim the omnipotence of nature and submission to it and, at the same time, we find it difficult to accept the idea that hazard can have causes that are not causes that are not human. Natural hazards do not exist as such and are not an obstacle to development or an explanation for the contrast in wealth.

One idea is that every society builds its economic development on the basis of consumption of resources that are natural in the sense that they are not manufactured. These natural resources are essential for the continuation of production and if production destroys them, this poses a problem in the long run. Much work is focused on the past and has attempted to explain a number of major civilizational disasters and the disappearance of some civilizations by resource management problems. Among the two great examples that can be studied, he has the disappearance of Mayan civilization. When the conquistadors arrived in Central America, the Maya had already disappeared. Another example is that of Easter Island, which was settled late as part of the great migrations of Polynesian peoples. It is very famous by the giant statues which were erected, but also by the fact that these statues testify of a rather powerful and prosperous civilization, of a strong density on the island whereas at the time when the first explorers reached it at the XVIIIème century, they found a society where reigned the misery, the famine and with very weak densities. Obviously, the island, at one time was very populated and with a high level of technology as well as a high level of production and consumption and then when the European explorers arrived, this civilization had almost disappeared without having any idea of how well these colossuses had been carved, in the quarries, transported then and then erected.

One of the theories is that of Diamond which is that of ecological catastrophe. His theory is that the Mayan economy and society as well as the economy and society at Polynesian Easter Island were both on over-exploitation of a fragile environment. Easter Island had a dense forest cover and the inhabitants of Easter Island gradually deforested the whole island in a few centuries because they needed wood to transport the famous colossus. Once the island was completely deforested, the result was soil erosion, a change in ecosystems that had catastrophic consequences. According to Diamon, many companies have disappeared because they have failed to manage their resources. Instead of preserving their resources as part of a concern for sustainability, they have instead destroyed their resources in an attitude that is suicidal.

This thesis met with a great echo because it corresponds to important questions today about millenarian anxieties about the limits of growth, about the depletion of non-renewable resources and especially oil, about global warming with the whole theory of sustainable development which would not allow the satisfaction of current needs to be done at the expense of that of future generations. It is economic growth that does not jeopardize the needs of future generations. The idea that if companies may have disappeared because of their lack of precaution in the management of their resources, it is a counter-example that is precious today. Diamond's analyses have been much contested and beaten up. When we read the scientific literature on this subject today, it is very difficult to form an opinion. These disappearances remain quite mysterious. Anguish over resource management is more the result of current questions than the fruit of historical experience.

We must try to relate these questions to the use made of them and their possible use in political and international relations. We realize that if we reason in terms of natural resources, in terms of natural risks or in terms of sustainable development, we are often faced with a North-South opposition with Northern countries that, after having experienced industrialization, after having experienced pollution, have come to reasonable positions with a certain deindustrialization, a tertiarisation of the economy, weak growth and then production which is essentially linked to services of a low-polluting type, which consume little raw materials and therefore respect the environment and ultimately guarantee sustainable development, respecting its forests and replanting them. On the other hand, there are the countries of the South, which are poor countries, which still have the insolence of double-digit growth, which still claim to be industrialized, which still pollute and which do not respect the imperatives that we would like to impose on them in terms of carbon footprint or environmental management.

This reading poses several problems, particularly in terms of the heritage of resources that are not ours, with the idea, for example, that the Amazon forest is the lungs of the planet. Another problem is to condemn deforestation and then industrialization, which consumes resources and causes pollution when all our societies have done so. We always arrive at the same model, which is that of a temperate zone where it goes well where wealth is created, a sustainable wealth and then an intertropical world based on the hypothesis of the natural environment is that it does not succeed. We cannot explain wealth gaps and development by referring to the natural environment. Even if we recognize that there is an important influence of environments on societies, it is not natural environments, but environments that are deeply transformed by man.

Demographics

The idea that the wealth of a country is made up of its demography both because the population is the labour force therefore that production would be correlated to the labour force available therefore to the population. A more recent development of this theory is to focus on the population not as a labour force, but as a fruit of consumption. That is, countries that have developed are countries where there has been the development of a large consumption basin and significant demand. On the one hand, it is very difficult to establish correlations between cases of density and cases of development and if natural resources and natural risks do not move, populations on the other hand migrate. The great migrations of the 19th and 20th centuries are labour migrations. Nevertheless, on the basis of this relationship between demography and the economy, a certain number of policies have been put in place, but these are not policies aimed at increasing the population or increasing labour force or even consumption by working demography, but rather the reverse. Correlations were considered too important and then poverty and risk played a major role in the 19th century and also in the 20th century with the idea that there would be a profound contradiction between the rates of population growth and the rates of economic growth and in particular the rates of growth and renewal of resources.

Malthus' model is an agricultural model and it is very simple to see that a society is developing at a much faster pace than its ability to develop new soils and increase agricultural production. All resources will experience this phenomenon of lag and dropout between a population that is growing exponentially and then a production that fails to keep pace with catastrophic predictions of a real collapse. We are not in the theory of ecological catastrophe, but rather in that of a kind of fatality. This has resulted in the implementation of Malthusian policies aimed in particular at limiting the number of births or delaying the age of marriage. In the West, we dropped these Malthusian policies because we stopped having children, but we would have liked these policies to have been implemented in China or India. There is the orientalist fantasy of a targeted animal population that cannot control its birth rate, cannot control its population and reproduces like "ants". The term "demographic bomb" was used in this sense. This is not new because the idea of the "yellow peril" has been around since the beginning of the 20th century. Initially it was a political and economic peril that was linked to two traumatic events, the first was the Japanese victory over the Russians in 1905 and the boxer revolt in China. This idea knew as a kind of renewal at the end of the 20th century with the idea of the "demographic bomb".

If one evokes the idea of a carrying capacity of the earth which is the idea that the earth could contain only a certain number of people and not a plus, one came back on this idea. The problem with this idea, which is also reflected in the idea of sustainable development, is that projections are made today on the basis of two unknowns that cannot be taken into account but which are nevertheless essential: the first unknown is technological change and the second problem is changing needs.

On the other hand, there is certainly a concern in Europe, particularly, to a lesser extent in North America, on the issue of ageing. The problem may not be in the quantity of the population, but in its quality, namely the characteristics of this population and in particular its age. What is a problem is the relationship between the working population and the non-working population. The problem of "quantity" is that in European populations this relationship is increasingly unbalanced. The second, "quality", is the level of qualification and the cost of labour. What matters today is less the quantity of population than its qualification and its cost with two configurations:

- areas where societies generally have a high labour cost and a high level of qualification as typically the countries of the North;

- other configurations where we have a low-skilled labour force with a labour cost that is typically low like in the countries of the South.

Culture and institutions

These two types of labour do not allow the same type of activity to develop. Much work has focused on the role of culture, the role of social institutions in general and development. An attempt was made to see to what extent types of societies, modes of social organization and social values could be correlated with economic development. As is often the case, these civilizations were characterized first and foremost by their religion. Weber, but also Huntington with his theory of the clash of civilizations. Many works have tried to reflect on the link between certain types of religion and then economic development beginning with Weber's famous works dating from 1905 on Protestant ethics and the spirit of capitalism in which he relates the birth of commercial capitalism in central Europe and Rhineland Europe with the development of Protestantism. He proposes a whole series of oppositions between values or modes of social organization which would be linked to Catholicism and Protestantism with the idea that if market capitalism developed on the Rhine axis, it was because Protestant values and Protestant society were predisposed to it. The idea is that Protestantism would carry the same values as capitalism, whereas on the contrary, Catholicism would promote values where the city would be organised in a way less favourable to this development. On the side of Protestantism and capitalism, we would find the importance of the individual, the initiative and the value of the individual, the enhancement of technology and progress, an emphasis on the importance of material success and then an adherence to science and an enhancement of scientific knowledge. On the other hand, Catholicism would not be very individualistic, but it would rather value group and community behaviour and values, it would rather be in the enhancement of nature than of technique. Weber's theory is that the countries that had the values of the first group were both the countries that experienced the development of Protestantism and capitalism. His work is very striking and always very controversial. On this basis, we continued to try to make correlations and maps between religions and then growth.

Two major assumptions that we see a lot is the incompatibility of Buddhism and Islam with development. As far as Islam, for example, is concerned, there is nothing comparable to what happened in Japan, Europe and then the United States. Another interpretation consists in saying that the vision of society, the place of women, freedoms, progress and the relationship to time are not compatible with economic, industrial and market development. One example cited much is that Islam condemns lending. For a theological reason, it is God who creates. One solution is to tell ourselves, for example, that interest is not there to pay for the money that we are going to lend, but to compensate for the shortfall earned from the fact that we lent money. There are possible ideological solutions.

The problem with these explanations is a bit like the explanations on the North-South opposition and then on tropicality. There are reasons to explain why it was logical, it was expected that it was in Europe that industrial revolutions and wealth accumulation occurred. There is always the suspicion that we are in logic and rhetoric of justifications.

It is interesting to focus on questions of political organization, on the importance of the state and then to ask the question of the link between democracy and market development and the development of market capitalism. The idea that the market is something that would appear spontaneously must be broken. We need a State and a strong State to set up a market and then for the market to be organised, structured and prosperous, the State must be present, it must be respected and it must provide a certain number of guarantees. These guarantees are those of the law and commercial law with the fact that when someone does not respect his contract, there are possible remedies and it is possible to go to court and trust the justice. There's the idea that you can trust the state to be violent. The State has a monopoly on legitimate violence, the State must exercise its violence, but it must be the only one that is able to exercise this violence.

More fundamentally, this means that the market, if we understand it this way, is hampered by dictatorships. What the market hates is uncertainty, situations where we don't know the rules. If you don't know the rules, you can't make any predictions, projections or trust anyone. However, the market is based on a certain management of time and trust. If the market hates dictatorships, it is not because they are not stable, that is, with a dictatorship, you never know what can happen. There can be a change of jurisdiction and it can decide to nationalise, to oust without respecting the law. We need a strong state, we need a respectable state, a state that is respected and offers stability in the institutions that allow us to do business. There has to be a normal situation that you can count on. The State is an extremely powerful economic actor playing an essential role in the construction of the market, it is also an actor that intervenes on the market, it is a producer, it is a consumer, it has a major role in stimulating production and consumption. The state is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for the emergence of the market, capitalism and development. In all these theoretical constructions, it is taken for granted that the market corresponds to the industry that corresponds to development and wealth creation.

After the fall of the USSR, Russia did not experience a period of economic development such as one could have imagined and the main reason is material and financial insecurity. Again for foreign investors, this is very difficult to manage. The disappearance of the communist regime in Russia did not provide an opportunity for the development of a market economy, but almost the opposite. It is for lack of a strong state and a right respected and imposed by an authority monopolized by the state that this country has not experienced this rush of investors that we could have hoped for. The reason why investors continued to be reluctant to get involved in business in Russia was not because of a strong state, but because of a lack of a strong state.

The second very interesting question is the relationship between democracy and economic development, namely democracy, capitalism, the market economy or the market. This idea is very present in Liberal ideology and it is very strong in the United States. It really is an American certainty. Democracy is the market go together in this idea. The reason why the foreign policy of the United States is so keen to bring democracy where it does not exist enough and to bring these countries into the market. This link between the two is in the sense of the word liberal in English, which refers both to the freedom to undertake and to the individual freedoms that are achieved through democracy. This was theorized by Karl Popper as part of his idea of open society. He opposes two types of theories: open societies characterized by freedom, transparency, mobility and then closed societies characterized by opacity, lack, freedom and then lack of mobility. Public societies are democratic societies and only public societies would be conducive to the establishment of a market economy.