« Foreign policy actors » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 82 : | Ligne 82 : | ||

=== The Treasury Department === | === The Treasury Department === | ||

[[File:Organization of US Dept of the Treasury.jpg|thumb|U. S. Organizational Chart Dept. of the Treasury.]] | |||

The Treasury Department becomes extremely important, especially at the time of the Versailles Treaty negotiations. The United States, in the aftermath of the First World War, was to play a financial role, particularly in the economic issues of the inter-war period, with the question of reparations, debts from wars and Allied credits, which were resolved through a number of plans such as the Dawes plan and the Young plan. The development of these plans is largely done with the help of the Treasury Department playing an increasingly important role in American diplomacy as economic issues become increasingly important in international relations. In the aftermath of World War II, the Treasury Department played a prominent role in the[Bretton Woods System: 1944-1973] Conference of Bretton Woods. From the 1970s onwards, this department increased its role in financial matters during the G8 summits. | |||

=== The Department of Commerce === | === The Department of Commerce === | ||

Version du 7 février 2018 à 00:26

We will describe these different actors and see how they interact over time. The American foreign policy is characterized first of all by an extremely important device and machinery in so far as one has to deal with a diplomacy that became global at the beginning of the 20th century. It is a multi-sectoral diplomacy that is developing in a whole series of areas being one of the absolutely fundamental elements of the concept of superpower. When we talk about superpower, we often take the politico-military aspects, but there are many others with the capacity to intervene in various fields. This diplomacy is taken care of by numerous professional and private actors.

The State Department is not the only player in American foreign policy dealing with transnational history issues. This multipolar character of American foreign policy is the permanent interaction between public and private actors who are not responsible for the diplomatic function. There is an extremely blurred border when it comes to U.S. foreign policy and the distinction between public and private because there is a permanent back-and-forth between the public and private sectors. This phenomenon is a colonization of the public sector by private actors. There is also a proliferation of public institutions whose public nature is sometimes unclear with federal agencies.

One may wonder whether or not American foreign policy is a coherent entity. Even today, the American position is difficult to determine because different actors take the floor and it is difficult to see how they agree. Foreign policy is also permanently between centralisation, i.e. coordination by the state authorities and decentralisation by the fact that the administration and government can be complemented or competing or contradicted by other institutions that will move in a different direction. As long as the United States has an increasingly global policy, we are witnessing a diversification of decision-making centres.

The President/Congress dyarchy

Distribution of original powers

This dyarchy is absolutely fundamental because we have two heads of the executive branch in both domestic and foreign policy. The checks and balances system is a political system that is fundamentally marked by the balance of power. Each power has a counter-power that is made compulsory by the American constitution in order to achieve the synthesis between the strong power to fight against external elements and the respect of freedom within in order to avoid tyranny.

The Powers of Congress

Congress is the dominant power in the United States at first. Congress is the fundamental element in the American political system at first. It is Congress that has the power to declare war and put an end to it through the ratification of treaties, it gives the army the financial and logistical means to function, from the point of view of the implementation of foreign policy it is it that ratifies the appointments in all federal administrations and in particular the Secretary of State who is a key post. On the other hand, Congress and the Senate, through the Foreign Affairs Committee, can deal with a whole series of issues, including the hearing of administrative officials. The Senate and Congress also regulate immigration. It is a fundamental and founding institution that at the beginning of American history has most of the prerogatives.

Powers of the President

The President only comes second in the Constitution in Article 2[1]. In the American legal culture, a president is a potential tyrant, which is why the president is elected through Congress but can also be dismissed by Congress. He's the commander of the armies. The President can launch a military operation without the repeal of the parliament for a limited period of up to 60 days, after which Congress and the Foreign Affairs Committee must approve it, and that is what happened during the intervention in Kosovo in 1999. This also marks a strengthening of the prerogatives of the US President. In negotiating and signing treaties, he represents the nation. This is one of the things the president has taken over as he goes along, but Congress must then ratify it. From 1789 to 1989 only 21 treaties were not ratified out of more than 1500 signed, including the Treaty of Versailles. It also nominates Secretaries and ambassadors.

Changes in power relations

L’évolution des rapports de force

It is both a balance of power and a balance of power from the end of the 18th century to the present day. We are still in a process of this kind with four general ideas:

- continuous reinforcement of the powers of the President [see the increase in executive agreements at the expense of treaties]: since the end of the 19th century and until today, there has been a strengthening of the President's powers in relation to the powers of the Senate. As the United States expands and emerges on the international scene, this will be in line with presidential prerogatives in foreign policy. A treaty can be signed as such or as an executive agreement. When considered treaty, it must pass through Congress, otherwise if it is an executive agreement, the signed text does not pass through Congress. The President will ensure that the signed texts are "executive agreements" to bypass the power of the Senate.

- in times of crisis, Congress sits behind the president.

- The phases of expansion are marked by a preeminence of the executive with strong personalities such as Wilson and Roosevelt.

- Since 1980, relations have become increasingly conflictual: there is a balance of power, but these relations have become increasingly conflictual internally and externally since the 1970s and 1980s, with a change in majority more than 90% of the time.

From the creation of the American Republic to the end of the 19th century, there was a predominance of Congress in foreign policy, even though Monroe distanced himself from it in the 1804s. There is a hinge between the years 1890 and 1914 where there is a very clear shift in the balance of power marked by Théodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, which breaks down the rather restricted framework of presidential prerogatives. Roosevelt arrogates the mission of "the Americanization of the world..." while Wilson embodies the rise of American foreign policy by traveling in person to the Versailles conference.

In the inter-war period, there was a continuous increase in the powers of the president. The period from 1919 until the Second World War was marked by a strong confrontation between the President and Congress, which was based on a balance of power between the two institutions. First of all, there is the opposition to the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which is first of all a vote by the Senate against Wilson rather than against the Treaty of Versailles, reminding us that it is he who has the power to decide whether or not to ratify the treaty. From the 1930s onwards, when Roosevelt arrived, the confrontation between the president and Congress resumed, among other things, on the establishment of the New Deal in domestic politics, but there were strong objections to foreign policy, since neutrality laws were passed by Congress against Roosevelt's advice.

After these strong oppositions in the 1930s was the time of the Second World War, when Congress stood behind Roosevelt, what Arthur Schlesinger called the beginning of the "imperial presidency" until the 1950s when presidential power reached its peak in foreign and domestic policy.

In the 1950s, there was a change of scene in which Congress regained an advantage with the Vietnam War, which was first disputed by the public and then by the Senate in particular with regard to the expenses it entailed. In 1972 the Case Zablocki Act was passed, requiring the president to consult Congress for any executive agreement limiting his or her capacity. In 1973 the War Power Act was passed, stipulating that the president must seek congressional approval for a commitment of U. S. military troops beyond two months. These are two significant elements of the pendulum reversal.

Beginning in the 1970s, the Senate will embark on an evaluation of federal programs, and in particular federal programs intended for the outside world. After the Second World War, the United States embarked on the implementation of global aid policies. In the 1980s, the Reagan presidency relaunched the Cold War without reference to Congress, a time when much of the initiative fell to the federal government.

The 1990s was marked by a fairly constant confrontation between the presidency of Bill Clinton, who, during almost every term of office, had to deal with a Republican-majority Senate, and therefore American foreign policy was marked by a series of presidential decisions and counter-decisions. There was the intervention in Somalia in 1994, but very quickly Congress refused to continue funding this intervention, leading to the withdrawal of the United States, which led to a failure of the intervention. In 1995, the United States intervened in Yugoslavia at the head of NATO. This intervention is done, but it only took a short time for it to be refused. Beginning in the 1990s, the United States blocked payment of the U. S. contribution to the United Nations decided by Congress, and even today funds are still not paid to the United Nations as a contribution. In 1999, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, which was a top priority for Clinton, was refused ratification. During the Clinton presidency, interference between domestic and foreign policy was very much present.

In the decade 2000, in the aftermath of September 11, the Patriot Act was passed to strengthen presidential prerogatives in the fight against terrorism. Between 2001 and 2004, the Congress stands in solidarity with President George W. Bush. The invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq could only be possible because the presidential function has regained control over its prerogatives.

There is a clear thread running through the balance of power between the Presidency and Congress. There is a process that has evolved in favour of the presidential pole.

The bureaucratic maze

It is the idea that in the implementation of U. S. foreign policy. There are more and more institutions involved in American foreign policy. It is a crucial phenomenon in American history that is the bureaucratic proliferation which is a phenomenon of all major industrial states with a proliferation of bureaucratic and administrative organizations. In order to understand American foreign policy, this dimension must be taken into account.

In the 1970s, Graham Alisson developed the concept of bureaucratic politics. It is an idea that allows us to think about political and state decision making in the context of a complex decision-making process and rivalry between Departments. This bureaucratic maze is colossal in the United States to illustrate this polyphony of American foreign policy. The long-lasting phenomenon of the rise of the American president is a dyarchy between federal administration and Congress.

Departments

The Department of State

The Department which is most important from the outset is the State Department because it divides the federal administration in the implementation of foreign policy. In 1789 they were small administrations, while from the 20th century onwards they grew. The Department of State saw its headcount increase from 6 in 1789 to 20,000 in the 1960s. The Secretary of State has six under-secretaries who must negotiate among themselves. Policy planning Staff is the governing body. There are a whole series of floors that make the implementation of this complex policy complex.

In the long run, there is a very traditional State Department administration founded as a traditional diplomacy that is the business of professionals and which has taken a long time to adapt to the new diplomatic realities. It is a rather classic concept of international relations.

This State Department, which functioned in symbiosis with the President at the beginning of the 19th century, will see its relations with the President deteriorate as the President's prerogatives will increasingly be exercised to the detriment of Congress, but also to the detriment of his Secretary of State, who initially became a collaborator rather than an executor. The reports become difficult because the secretary of state has difficulty admitting the strengthening of presidential powers. Gradually, the State Department will be marginalized and competing with other departments that will take more initiatives in foreign policy making.

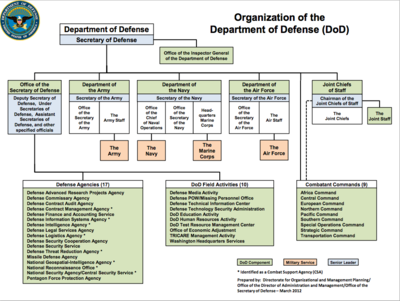

The Department of Defense

The Department of Defense, which was originally divided into a War Department and a Navy Department, will merge to form the Department of Defense. This is a department that will become more and more important. In the rise of the Department of Defense, there are two world wars and in particular the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. In 1945, there was a partial demobilization since there were still other fronts and the Cold War was looming. The War Department, which must be deflated after a conflict, remains important, especially since the signals remain red in a whole host of areas. The Cold War arrived with the vote of the National Security Act, which finally merged the Department of War, Navy and the U.S. Navy and the Department of Aviation in a "super-department" of defense symbolized by the Pentagon[2][3]. In 2009 it was 2 million employees, a budget of 500 billion dollars. During the Cold War 75% of the American administration works for this department. Today, the Department of Defense has taken the lead over the State Department.

Other departments will make the relationship between the United States and the world unique because American foreign policy and expansionism are expressed in other ways in a multiplicity of policy areas.

The Treasury Department

The Treasury Department becomes extremely important, especially at the time of the Versailles Treaty negotiations. The United States, in the aftermath of the First World War, was to play a financial role, particularly in the economic issues of the inter-war period, with the question of reparations, debts from wars and Allied credits, which were resolved through a number of plans such as the Dawes plan and the Young plan. The development of these plans is largely done with the help of the Treasury Department playing an increasingly important role in American diplomacy as economic issues become increasingly important in international relations. In the aftermath of World War II, the Treasury Department played a prominent role in the[Bretton Woods System: 1944-1973] Conference of Bretton Woods. From the 1970s onwards, this department increased its role in financial matters during the G8 summits.

The Department of Commerce

The Department of Justice

The National Security Council[NSC]: A State Department?

Intelligence services

Government Agencies

Private actors

Lobbying in Congress

Action on the ground

Institutions of expertise: think tanks

First Generation

Second Generation

Institutions of Expertise: Private Actors in the Federal Administration

Institutions of expertise: universities

Annexes

- Casey, Steven. "Selling NSC-68: The Truman Administration, Public Opinion, and the Politics of Mobilization, 1950-51*." Diplomatic History 29.4 (2005): 655-90.

References

- ↑ Legal Information Institute - U.S. Constitution, Article II

- ↑ National Security Act of 1947 on Wikipedia

- ↑ Text at the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence