Open Macroeconomics: the Exchange Rate

| Professeur(s) | |

|---|---|

| Cours | Introduction to Macroeconomics |

Lectures

- Introductory aspects of macroeconomics

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

- Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- Production and economic growth

- Unemployment

- Financial Market

- The monetary system

- Monetary growth and inflation

- Open Macroeconomics: Basic Concepts

- Open Macroeconomics: the Exchange Rate

- Equilibrium in an open economy

- The Keynesian approach and the IS-LM model

- Aggregate demand and supply

- The impact of monetary and fiscal policies

- Trade-off between inflation and unemployment

- Response to the 2008 Financial Crisis and International Cooperation

The price of international transactions

The exchange rate between two countries is the price at which trade between them takes place.

There are two types of exchange rates :

- The nominal exchange rate (Purchasing Power Parity theory and foreign exchange market → this chapter);

- The real exchange rate (equilibrium condition in an open economy → next chapter).

The nominal exchange rate

The nominal exchange rate is the rate at which an individual can exchange the currency of one country for that of another (relative price of two currencies).

The nominal exchange rate is measured in two ways

- Unsure ("direct quotation") = # of units of national currency per unit of foreign currency (e.g. 1 EUR is equivalent to 1.20 CHF for a Swiss resident).

- to the certain ("indirect quotation") = # units of foreign currency per unit of national currency (e.g. 1 CHF equals 0.83 EUR for a Swiss resident). This type of quotation is applied in London, New York and since the introduction of the single currency on all places in the Euro zone.

By definition the expression "CHF/EUR" is equivalent to the quotation at the certain and is currently worth about 0.83.

Obviously: exchange rate at uncertain = 1 / exchange rate at certain

Currency appreciation occurs when you can buy more units of foreign currency with one unit of domestic currency (↓ from exchange rate measured to uncertain and ↑ from exchange rate to certain). Depreciation occurs when you can buy fewer units of foreign currency with one unit of national currency.

For this rate, we will represent the exchange rate by the variable "e", which represents the amount of foreign currency that we get for one unit of domestic currency. If e ↑ = appreciation of the domestic currency.

The real exchange rate

The real exchange rate is the rate at which an individual can exchange domestic goods and services with those of another country (relative price of goods).

It depends on the nominal exchange rate and the prices of goods in both countries:

Real exchange rate (ε) =

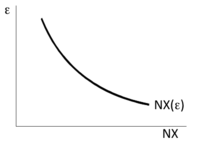

The real exchange rate is a crucial factor in determining a country's exports and imports.

A real depreciation of the currency (↓ of the real exchange rate) means that the domestic country's goods have become cheaper → consumers (domestic and foreign) demand more domestic goods and less foreign goods → the country's EXPs ↑ and IMPs ↓ and consequently net exports (NX) ↑.

PPP Determination of the Nominal Exchange Rate

The Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) theory is the simplest and generally accepted explanation for nominal exchange rate fluctuations in the long run. According to PPP, one unit of a currency buys the same amount of goods in all countries.

Hypothesis: Law of One Price = arbitrage forces equalize the price of the same good sold on different markets. If this is true for all goods

Absolute PPP: a currency must have the same purchasing power in all countries and the exchange rate varies to ensure this.

- .

relative PPP (less restrictive than absolute PPP): the exchange rate between the currencies of two countries reflects the difference in the general price level of these two countries.

- percentage change in e = percentage change in - variation % de =

Inflation differentials and the exchange rate

If the central bank increases the supply of money, domestic money loses value in real terms (inflation) and in terms of the number of units of foreign currency it can buy (continuous depreciation).

The exchange rate in times of hyperinflation (Germany)

Criticisms of the PPP

- Not all goods are traded → non-exchangeable goods (they represent a significant part of GDP) → the law of one price for these goods is not verified;

- Tradable goods are not necessarily perfect substitutes (national preference and non-homogeneous goods) → different spending structures and no trade-offs;

- Free trade barriers (trade barriers, transport costs...) → no arbitrage.

The Big Mac Index

The economist's Big Mac index, (see readings): instead of considering a basket of goods to construct P and P*, we consider the price of a single good, the McDonald's Big Mac (= basket of ingredients, the same everywhere).

Theoretical exchange rate :

If , an appreciation of the CHF (= depreciation of the USD) is to be expected.

The foreign exchange market

PPP provides a (long-term) reference value towards which the exchange rate is expected to move.

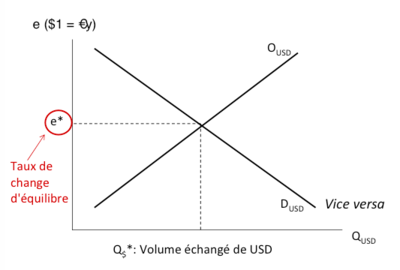

Exchange rate: the relative price of one currency to another currency. Like any other price, also the price of a currency is determined, in the short term, by the meeting of demand and supply (=> fluctuations around the long-term value determined by PPP).

PPP provides a (long-term) reference value towards which the exchange rate is expected to move.

Exchange rate: The relative price of one currency to another currency. Like any other price, also the price of a currency is determined, in the short term, by the meeting of demand and supply (=> fluctuations around the long-term value determined by PPP).

Example: buying and selling USD against Euros (determinants of O and D):

- Offer USD = Request Euros

- European B&S experts

- European asset managers

- ...

- Central bank interventions (USD sales → curve shift)

- Demand USD = Offer Euros

- B&S European Imp.

- European Asset Imp.

- ...

- Central bank interventions (USD purchases → curve shift)

When the USD appreciates against the Euro (it takes more Euros for $1), European products seem cheaper to Americans, who will ask for more => conversion of more $ against Euros in the foreign exchange market => increasing $ bid function.

SHOCKS: any change in the supply or demand for US dollars will have an impact on the balance of the foreign exchange market.

If, for example, the flow of European capital to the United States were to increase because of a change in investor preferences, the demand curve would shift to the right, causing the US dollar to appreciate against the euro (which would also lead to an improvement in the European trade balance: the balance of payments is still in equilibrium).

In reality the impact of shocks on the equilibrium exchange rate depends on the flexibility of the exchange rate → EXCHANGE RULES = set of rules governing the foreign exchange market.

Two "extreme" exchange rate regimes (floating and fixed exchange rates) as well as a multitude of other intermediate possibilities (administered floats, fluctuation bands, etc.).

Régime de changes flottants

Sous un tel régime de changes :

- les banques centrales n’interviennent jamais sur le marché des changes

- la balance des comptes est toujours en équilibre (le taux de change s’adapte à toute variations de l’O et de la D de devise pour rétablir l’équilibre) :

- Si déficit de la Balance → dépréciation de la monnaie nationale

- Si surplus de la Balance → appréciation de la monnaie nationale

Régime de change fixe

Sous un tel régime de changes, les banques centrales interviennent constamment sur le marché pour garantir une certaine parité des cours → perte d’autonomie des banques centrales: la politique monétaire n’est plus un instrument d’intervention indépendant pour la banque centrale (l’offre de monnaie varie pour maintenir la valeur de la monnaie nationale sur le marché des changes constante).

Exemples :

- Système d’étalon-or, 1879 – 1914: parité fixe en or;

- Système d’étalon du change-or (Bretton Woods), 1946 – 1973: parité fixe en dollars américain à son tour fixé en or;

- Système monétaire européen, 1979 – 1999: fluctuations admises dans un tunnel autour de la parité;

- Dans beaucoup de pays, la monnaie nationale est ancrée par rapport à une autre monnaie.

Problème:

- le taux fixé par la CB peut ne pas coïncider avec le taux d'équilibre → interventions pour conserver la parité souhaitée.

TROIS OPTIONS pour éviter la dépréciation du dollar de Hong Kong :

- Interventions sur le marché des changes : la CB absorbe l'excédent de HKD en achetant sa monnaie en échange de USD. Problème: le réserves de devises des CBs ne sont pas illimitées.

- Interventions de politique monétaire finalisées à déplacer les courbes d'O et de D : par exemple, si la CB augmente le taux d'intérêt domestique, la hausse de capitaux entrants ferait augmenter la demande de HKD (déplacement de la fonction de D versa la droite).

- Contrôles des changes. Introduction de limites à l'achat de devises étrangères.

NB.: évidemment ces trois mesures seront appliquées dans la direction opposée si .

Changes fixes vs changes flottants

Il existe plusieurs arguments à faveur de l'adoption d'un régime de change fixe (pas d'incertitude, stabilité, contrôle de l'inflation...), mais la fixation du taux de change comporte aussi des coûts : perte d'indépendance de la politique monétaire, distorsions dus aux contrôles des changes.

Ce dilemme est résumé dans un principe connu dans la littérature sous le nom de Trilemme de Mundell ou la « Trinité impossible »

Un pays ne peut pas simultanément avoir un taux de change fixe (et garantir ainsi la stabilité des interactions internationales), garantir la parfaite mobilité du capital (et promouvoir ainsi l'intégration et l'efficience des marchés financiers) et profiter d'une politique monétaire autonome (et gérer ainsi un instrument de politique économique de stabilisation).

Résumé

- Le taux de change entre deux pays est le prix auquel se font les échanges entre eux

- On parle d’appréciation d’une monnaie quand on peut acheter plus d’unités de devises étrangères avec une unité de monnaie nationale

- Les exportations nettes d’un pays dépendent du taux de change réel: une dépréciation rende les biens du pays domestique moins chers et en conséquence les exportations nette augmentent

- Le taux de change nominal reflet le différentiel entre taux d’inflation (PPA)

- La PPA se base sur des hypothèse assez restrictives (biens tous échangeables, même structure de la dépense, arbitrage)

- La parité entre deux devises est le prix d’équilibre du marché des changes

- On distingue deux régimes de change: fixe (interventions de la banque centrale pour maintenir la parité) et flottant (pas d’interventions de la banque centrale)

Annexes

Sur l'Indice BigMac :

- McCurrencies, The Economist, 24.04.2003

- Bunfight, The Economist, 02.02.2013

- Pour les données les plus récentes : http://www.economist.com/content/big-mac-index

References

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Neuchâtel

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur Research Gate

- ↑ Researchgate.net - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Google Scholar - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ VOX, CEPR Policy Portal - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Nicolas Maystre's webpage

- ↑ Cairn.ingo - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Linkedin - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Academia.edu - Nicolas Maystre