Introductory aspects of macroeconomics

| Professeur(s) | |

|---|---|

| Cours | Introduction to Macroeconomics |

Lectures

- Introductory aspects of macroeconomics

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

- Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- Production and economic growth

- Unemployment

- Financial Market

- The monetary system

- Monetary growth and inflation

- Open Macroeconomics: Basic Concepts

- Open Macroeconomics: the Exchange Rate

- Equilibrium in an open economy

- The Keynesian approach and the IS-LM model

- Aggregate demand and supply

- The impact of monetary and fiscal policies

- Trade-off between inflation and unemployment

- Response to the 2008 Financial Crisis and International Cooperation

What is macroeconomics? Definitions and main macroeconomic aggregates

Domain

There are two main distinct but nevertheless complementary fields:

The micro-economy focuses on economic agents: consumers, savers, investors, entrepreneurs, governments, trying to understand:

- their behaviors / decisions, and their implications;

- their interactions in the different markets (goods, services, labour, capital).

Macroeconomics looks at the economy as a whole. It focuses on the major aggregates: savings, consumption, growth, inflation, unemployment, trying to understand:

- the determinants of their evolution;

- the interactions between the different aggregates.

NB: In macroeconomics, the behaviour of all economic agents is "'more than"' the sum of their individual actions and their consequences on the markets ("amplified" effects). Cf. the savings paradox

Questions

John Maynard Keynes' (1936) book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money is often seen as the starting point for the discipline. Keynes takes his insiperation from the Great Depression of the 1930s. Before that, the classical economic model did not foresee market failures and therefore there was no need for macroeconomics. The best that governments as well as economists could do was to look and not intervene in the economic system.

So, there are some typical questions of macroeconomics:

- How do you measure economic activity?

- Why do we see fluctuations in economic activity?

- What can be done to avoid excessive fluctuations?

- Why do we sometimes want to slow down the economy?

- Why do prices rise faster in some periods than others?

- What can the government do to ensure full employment?

- Why not keep injecting money in times of crisis?

The main variables

The main macroeconomic variables are :

- Real or nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP);

- the unemployment rate (proportion of unemployed workers);

- the inflation rate (rate of price increases over time);

- the interest rate.

They are studied at one point in time and through time. Other important indicators include wages, exports, exchange rates and stock market indices.

It is also necessary to differentiate the notion of stock from that of flow:

- a stock is a quantity measured at a point in time.

- a flow is a quantity measured during a certain interval. In other words, it is the evolution of the stock variable.

For example, a person's wealth is a stock, but his or her income is a flow; the number of unemployed is a stock, but the number of people losing their jobs is a flow; government debt is a stock, but the deficit is a flow.

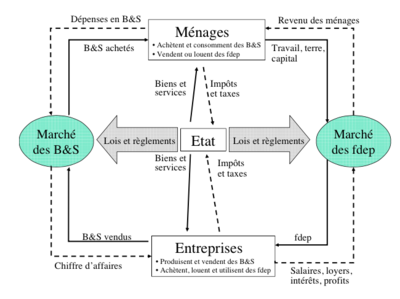

The economic circuit

The State as an economic actor

According to the first welfare theorem, competitive market allocation is optimal Pareto (or, in other words, the competitive equilibrium is efficient) making state intervention unnecessary and undesirable. BUT, this is true only under certain conditions, including no market failures, no uncertainty, no externalities, etc., and no market failures. Moreover, market allocation could be considered unfair by society leading to redistributive policies.

The market economy as such does not exist in reality and some situations require state intervention.

State intervention can be grouped under three functions:

- The allocation function;

- The distribution function;

- The stabilization function.

Functions of the State

The allocation function: there are market failures that lead to sub-optimal resource allocation. The State will intervene to change this allocation, for example by making goods and services available to society as a whole (public goods), financed by taxes or borrowing. Examples include national defence and public transport.

The distribution function: since the distribution of income and wealth is very unequal, the state is called upon to intervene according to standards of equity (defined by society). The aim is a redistribution of income and wealth. For example, the state can give allowances, introduce a minimum wage or have progressive income taxation.

The stabilisation function: the state can intervene to ensure the overall balance of the economy, avoiding unemployment and inflation as much as possible and having a balanced balance of payments. Its main instrument is fiscal policy. It can also intervene indirectly through the central bank by means of monetary policy.

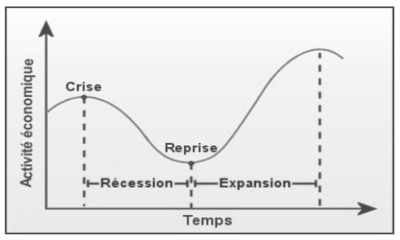

The business cycle

A business cycle is a short-term alternation of short-term declines and increases in economic activity :

- Recessions (or contractions in activity): periods of declining economic activity where output and employment fall ;

- Expansions (or recoveries of activity): periods of increase in economic activity where output and employment rise ;

- Peak activity: the point at which the economy goes from expansion to recession;

- Activity troughs: the point at which the economy moves from recession to expansion.

Growth Policies

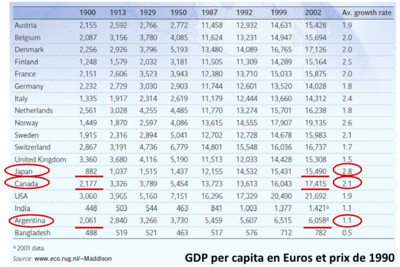

A growth policy is a trend towards a sustained increase in production. It is a relatively modern phenomenon dating from the 19th century and even beyond for a large part of countries.

A measure of the standard of living is the average income or GDP per capita of the economy.

Differences in living standards between countries are mainly explained by productivity differentials (even very small ones):

- The accumulation of physical and human capital increases productivity;

- economic policies and institutions also play a very important role.

Croissance à long terme

Un petit écart dans le taux de croissance du PIB peut faire une grande différence à long terme.

Two Great Schools

In the United States, a distinction is made between "saltwater" economists (Harvard, MIT, Stanford and Berkeley) versus "freshwater" economists (Chicago, Rochester, Minnesota).[11].

The Keynesians are rather salt water and think that markets don't always work properly and that governments must use economic policies to try to avoid recessions or excessive accelerations.

Monetarists and real business cycle economists are more freshwater people and think that the failures of governments are much more important than the failures of markets (political capture or inefficient bureaucracies). Monetarists argue that economic policy interventions are only effective if they are unexpected. Milton Friedman (Nobel Prize winner in 1976) is their "guru". Economists in the real business cycle find that government measures are counterproductive and distorting. Hayek (Nobel Prize in 1974) and Prescott and Kydland (Nobel Prize in 2004) are their "gurus".

Thinking like an economist

Methodological approaches

A distinction is made between positive and normative analyses :

- positive analysis: understanding what is. Positive analysis describes the way the world works (scientific approach to economics: it can be tested by comparing the analysis with the data).

- Normative analysis: studying what should be. Normative analysis prescribes the way the world works (the "policy-maker" approach: it is based on personal views, ideologies, value judgements).

For example, « Economic growth of 3% is needed this year », « Economic growth of 3% is needed to reduce unemployment by 4%. » or « The United States is richer and more developed than India because it has a higher GNP per capita. ».

The role of business models

An economic model is a working tool, i.e. a simplification of reality. Economic models are not "realistic" and they should not be. A model must simplify reality enough to understand what is happening and show the essential relationships between economic variables.

There is not ONE "correct" model, the role of testable assumptions must be emphasized.

A distinction must be made between the notions of exogenous and endogenous variables :

- exogenous variables: of origin outside the model;

- endogenous variables: explained, generated by the model.

The structuring of a model takes the following form:

- postulates + mathematical form (= simple language!) allowing to follow the logical implications and to find a solution + testable predictions.

The functioning of the scientific approach is as follows:

- observation → model → observation again

As in all sciences, the starting point is observation and modelling, with assumptions that simplify reality but are necessary to understand economic mechanisms. If the model has assumptions that are too detailed and realistic, it quickly becomes complex and without predictive power (as if). The most important thing is the predictive power, even if the assumptions seem unrealistic. Next, the models and their predictions are tested against the reality of the data. If they are not verified, the assumptions are corrected and we start again. The difference with hard science is that economists don't have a laboratory in which to conduct experiments. Their laboratory is the world: they have to look for 'natural' experiments.

How a graphic works

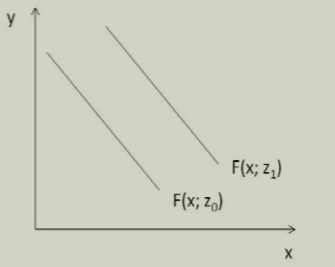

In the majority of cases we will give a graphical representation of the economic models we will analyze.

Care must be taken not to confuse the movement along a curve with the movement of the curve itself. If we have three variables, , and , and y is a function of and , = , in the usual two-dimensional graphs we can represent only two of the three variables. If we put and on the axes, the relation between these two variables is drawn assuming constant (in general we separate with a semicolon the variable assumed to be constant).

For example, the inverse relationship between and and the direct relationship between and (think of an inverse demand function where is price, is quantity demanded and is income). The variation of is a movement along the curve and the variation of is by moving the curve.

Causality: relinder

Graphical representation is a very useful tool to describe the relationships between economic variables, BUT beware of statistical illusions!

There is a risk of naively interpreting a simple correlation between variables as a causal relationship. For example, and are represented by a point cloud with an apparently positive slope. This does not necessarily mean that "cause" ! There may be a third hidden variable correlated simultaneously with and and causing them both.

This may reverse the direction of causality between variables. For example, countries under IMF (International Monetary Fund) programs have very high unemployment rates and incidence of poverty. This does not mean that IMF interventions cause poverty and unemployment! Rather, the causality goes in the opposite direction: from the economy in crisis to IMF intervention, not the other way around (it is because the economy is doing badly that the IMF is called upon to intervene).

L’étude de la macroéconomie et la crise économique de 2008

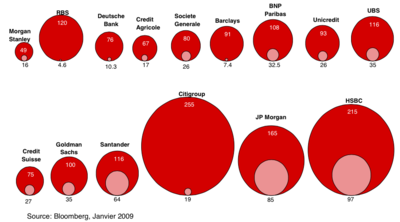

La crise 2008

- Valeur de marché en janvier 2009, $milliards

- Valeur de marché au trim. 2 de 2007, $milliards

Utilité de la macroéconomie

À quoi sert la macroéconomie si on a pas pu éviter la crise actuelle ? À quoi sert la médecine si on continue à tomber malade ?

L’étude de la macroéconomie permet de comprendre quelles sont les meilleurs moyens pour sortir de la crise rapidement et à moindre coût.

- Est-ce que une relance par la consommation (avec des réductions des taxes à la consommation) est une bonne chose ?

- Est-ce qu’il vaut mieux relancer l’économie par l’investissement ?

- Pourquoi la coopération internationale est-elle importante ?

Résumé

La macroéconomie est l’étude des relations entre les grands agrégats économiques. Son objectif est de comprendre comment on peut éviter les fluctuations dans la performance économique des pays et améliorer leurs niveaux de vie. La macroéconomie emploie une approche scientifique à l’analyse de la réalité et utilise des modèles pour simplifier la réalité et faire des prédictions.

Les variables macroéconomiques les plus observées sont le produit intérieur brut, le taux de chômage, le taux d’intérêt, le taux d’inflation.

L’État intervient dans la vie économique avec une fonction d’allocation, de distribution et de stabilisation. Il met aussi en place de mesures qui peuvent influencer le taux de croissance de long terme des pays et donc le niveau de vie.

L’étude de la macroéconomie ne permet pas d’éviter les crises économiques, mais sert à comprendre quelles sont les meilleurs moyens pour sortir de la crise rapidement et à moindre coût.

Annexes

- “International Monetary Fund.” International Organization, vol. 1, no. 1, 1947, pp. 124–125. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2703527.

References

- The other-worldly philosophers, The Economist, 16.07.2009

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Neuchâtel

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur Research Gate

- ↑ Researchgate.net - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Google Scholar - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ VOX, CEPR Policy Portal - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Nicolas Maystre's webpage

- ↑ Cairn.ingo - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Linkedin - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Academia.edu - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ The Economist, 16.07.2009