« The fundamental principles of relations between States » : différence entre les versions

| (4 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 32 : | Ligne 32 : | ||

== If the question was so important, why wasn't it addressed in traditional international law? == | == If the question was so important, why wasn't it addressed in traditional international law? == | ||

The arrangement of classical international law was an arrangement of indifference to the non-use of force; States could use force for their own political causes without the law interfering with it. | |||

In the 19th century, the answer would have been quite simple, to know if France and the United States want to intervene in Syria would come out of their own political decision and from the point of view of law, there is only the obligation to declare war. | |||

On the other hand, traditional law attached consequences to the entry into war. If a State chose to use force, there were consequences "in bello", i.e. on the way war was conducted, with a prohibition on the use of certain weapons that were too destructive or on the killing of prisoners of war, as well as on the neutrality of States that were not belligerents. | |||

What we have just mentioned, the "durante bello" obligations, have nothing to do with the political choice to enter or not to enter a war; some legal consequences followed from the entry into the war, but the law remained instrumental. | |||

The classical law was too weak to assume such a function. States in the 19th century did not want to ensure limitations on their ability to wage war; a sovereign state because it is sovereign automatically has by virtue of its sovereignty the right to wage war. In 1879, Chile attacked Bolivia, which is not illegal under 19th century law. | |||

== The second question is why international law has changed? == | |||

States did not want stronger intervention, the choice to go to war was a sovereign one. | |||

== Why do modern texts such as the United Nations Charter impose a prohibition on the use of force subject to certain exceptions? == | |||

Over time, the importance of maintaining peace in a more modern and different society has been recognized. International society has believed its interdependencies; in these increasingly complex and balanced environments, it was in the public interest to maintain peace. | |||

There are also more specific aspects that explain the change, all these more specific aspects have in common that they symbolize a war that has become more and more destructive and devastating. | |||

The war of the 18th and 19th centuries was often a war of little destruction, there were well formed and reduced armies until the Napoleonic wars. These professional soldiers could fight the battlefields with limited impact on society, on the other hand kings and dynasties maintained acceptable relationships, the rule was only a rule of the game to extend its domination. All this actually tends to contain the war. | |||

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries in particular, these idyllic assumptions disappeared, and modern warfare was considerably brutalized to the point of becoming a scourge. | |||

We have a whole series of reasons for this evolution: | |||

*the fact that war becomes a national cause with the conscription of a mass army and the hatred that mobilizes the nation leading to a war of a completely different scale. | |||

*the technological evolution leading to modern weapons as well as the development of aviation during the First World War. | |||

*industrialisation, which also contributed to the brutalisation of war, because modern war from the 19th century onwards is no longer necessarily won at the front, but upstream with industrial production, an industry that can support the war effort is needed. This means that the opposing belligerent will no longer only hit the combatants at the front, but also the industries, inducing that civilians will also be affected. | |||

War has changed in nature, it has become a disaster and a cataclysm; in view of this political and social transformation of war, we wanted to give it another answer. What was considered as a legitimate means of settling a dispute in the past relating to the classical vision, in the 20th century such a logic was no longer possible, war is a scourge and can degenerate into generalized wars, that is why there was a fundamental change of perspective in the matter. | |||

= | = The United Nations Charter is the founding text on this subject = | ||

== How does the Charter fit into international peacekeeping? == | |||

The first remark is that the Charter is based on the idea and principle that the use of force should be repressed as much as possible in international relations, at least when it is used by individual States. | |||

== | |||

War is no longer seen as a means of foreign policy by which to settle a dispute or impose one's own interests. | |||

However, the Charter is not a pacifist instrument. What the Charter does not want individual States to use force for causes that seem good to them, the Charter recognizes that force must sometimes be used, it reserves it on the one hand for States when they act in self-defence, that is, that a State is attacked by armed forces can and must resist by force, the Charter recognizes the usefulness of "police operations". The Charter recognizes that there are situations in international relations where force must be used to prevent greater harm from occurring. | |||

The judgment of such a situation is reserved to the United Nations and more particularly under Article 24, paragraph 1 to the United Nations Security Council. Not that this body is particularly angelic, but for the Charter, it is the only body that combines strength with a certain force of control and equity. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 24.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a24 article 24]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 24.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a24 article 24]]] | ||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 27.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a27 article 27]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 27.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a27 article 27]]]The Charter tries to do the same as we have in domestic law, we would legitimately be concerned if everyone could use force for causes that seem good to them. On the other hand, when there is a need to use force, it is necessary to turn to the police. For the Charter, the police is the Security Council, a body that may not be ideal, but it guarantees a minimum of multilateralism that means that everyone cannot do what they want. | ||

Experiments of generalized force were already made in the 19th century leading to the politics of the gunboat and the First and Second World War. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 2.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a2 article 2]]]It is remarkable that, unlike Russia and China, in the West since the previous one in Kosovo, a whole series of politicians believe that either we go through the Security Council and authorise action, but if it does not do so we proceed to a unilateral reaction, either with or with the Council, but this is not the legal situation, from the point of view of law only the Security Council can use action or there is use of force unless there is an assumption of self-defence. | |||

It is interesting to see that Western leaders no longer seem to take Article 2(4) seriously. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 2.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a2 article 2]]] | The argument that the Security Council is blocked is a magnificent one. As if by chance, the Security Council is always blocked when China or Russia uses a veto, but never when the West does. In the past the USSR used the most vetoes today it is the United States.[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 39.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a39 article 39]]] | ||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 39.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a39 article 39]]] | |||

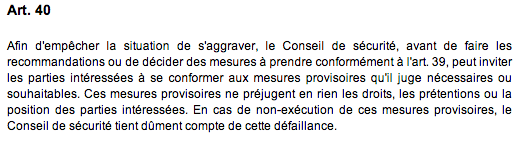

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 40.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a40 article 40]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 40.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a40 article 40]]] | ||

| Ligne 114 : | Ligne 107 : | ||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 50.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a50 article 50]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 50.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a50 article 50]]] | ||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 51.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a51 article 51]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 51.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a51 article 51]]]In Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, "Action in the event of a threat to the peace, breach of the peace and act of aggression", we have the competence of the Security Council. | ||

The competences of the Security Council go beyond the framework of ordinary international law, the Security Council can do things that would otherwise be illegal under international law, which States cannot do, but which are recognised by the Security Council, which has a police function. The Security Council can take peaceful sanctions or non-military coercive measures such as embargoes or the Security Council could take military action with United Nations military forces, but since the United Nations has never received military forces it cannot itself use military force. | |||

In United Nations practice, we have come to an alternative regime which consists in authorizing Member States to use force when the Security Council gives them the power to do so through a resolution. The established formula is "authorizes Member States to take all necessary measures (...)". Using this formula means that the use of force has been authorized if necessary. | |||

Peacekeeping sometimes means having to act urgently to prevent aggression, stop massacres, react to serious violations of the law, but as in domestic law we prefer the police to do so, in the same way we try in international law to centralize this in multilateralism. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 51.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a51 article 51]]]Section 51 deals with self-defence, or "self-defence" in English. | |||

Thus, we have a triptych in the Charter that is coherent in itself, although it is not always truly functional. On the one hand, States are told not to use force as a means of foreign policy, there is no desire for anarchy in the use of force by everyone and the fact that, through the use of force, the strongest is imposed on the weakest, which is neither the mark of civilisation nor the mark of justice. | |||

On the other hand, the Charter provides for the use of force and organizes it, but centralizes it in a body representing the international community, namely the United Nations and the Security Council, on which the five permanent members sit, and it must take decisions when there are citizens who threaten international peace. | |||

Someone is set up to ensure that the necessary actions are taken, including by force. There is one exception, in the case of armed aggression a State can and must defend itself, this is the exception of self-defence. Self-defence is only granted in the event of armed aggression. | |||

If self-defence were to be opened up to every violation of international law, States would be able to intervene anywhere in the world as in the case of serious human rights violations. If we open this way, we open the way for the use of force to be much more important than the Charter wanted to authorize it beyond the idea of repressing anarchy. However, no State acts for reasons other than war for altruistic interests. | |||

Armed retaliation is prohibited because self-defence is only granted as an exception to self-defence because it is necessary for self-defence and therefore we must concede this because a state needs self-defence to defend itself. | |||

On the other hand, armed reprisals do not represent the situation of necessity because the danger and arrested, there is nothing left to protect directly at this stage. In this case, military action is no longer an action of necessity, but a punishment action. | |||

The mission of the International Criminal Court is to prosecute and punish persons; in principle, a State does not have the mission and competence to punish another State because between States there is the principle of equal sovereignty. States are peers and one does not have to punish the other. | |||

Sometimes it is difficult to know very precisely whether it is an armed reprisal or not, as Israel did when it used reprisals after the fact.[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 51.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a51 article 51]]] | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 2.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a2 article 2]]]Chapter VII is the heart of the United Nations Charter, but only somewhere, actually. | |||

Chapter VII is the chapter devoted to collective security action, it is the great hammer, it is unique in international relations that a body has such extensive competence as the Security Council has under this chapter. | |||

It is a chapter dedicated to action, as the title of Chapter VII makes very clear, "action in the event of a threat to the peace, breach of the peace and act of aggression", while the rest of the Charter faithfully reflects the other aspect of the United Nations, namely that it is an organization where discussion, coordination and cooperation take place. | |||

The Security Council is supposed to act and we want it to be able to act with as many possibilities as possible. | |||

Chapter VII is the one that captures the imagination the most. Everyone is more or less familiar with Chapter VII, but in the Charter, Chapter VII is not in substance the most important, because the drafters of the Charter hoped that Chapter VII would not have to be applied. | |||

As the Charter tries to preserve peace, it tries to do so without the need for action to maintain or restore peace in extremis. The Charter strives to ensure that preventive action is avoided. | |||

Economic and social actions and the peaceful settlement of disputes, these chapters VI and VII have been inserted in the Charter, competences have been conferred on the world organisation in this field with the simple aim of having more diversified actions in order to maintain peace. | |||

The drafters of the Charter were aware that if there is a great disparity in the world, it does not guarantee peacekeeping. If there are such strong differences between States, there is a risk of violence; we try to deal with it not because if economic and social causes were valid causes in themselves, but from 1945 they were perceived as a means by which peace could actually be maintained; we work on the fact that there would be better conditions so that peace could prevail. | |||

The Charter tries to deal with these things with limited resources, because you cannot settle a dispute against the will of the people concerned, you cannot impose the settlement of a dispute. | |||

Chapter VII in the logic of the Charter is what is fundamental and distinguishes the current organization from the weakness of the League of Nations and at the same time the Charter is not focused on Chapter VII. | |||

The other remark on Chapter VII is that the drafters of the Charter wanted the Security Council to be able to act with as few obstacles as possible. | |||

The logic of the "highway" is that of the strongest possible executive that has the means to act promptly and decisively. | |||

First of all, the Security Council is centred around major powers, which had not been the case in the League of Nations. The Charter is more realistic, without the great steps of hope of imposing peace, only a preponderant force can be imposed on the aggressor. | |||

The strong executive is characterized by the absence of legal limits to the Security Council's action. States cannot legally do a whole series of things when the Security Council can do almost anything. In law, the Security Council is discussed, especially in terms of ius cogens, i.e. some fundamental norms that it cannot violate, otherwise the Security Council is free. | |||

A State cannot use force unilaterally under article 2, paragraph 4, while the Security Council may, because article 42 gives it absolutely discretionary power to use force if it considers it necessary.[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 42.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a42 article 42]]]A State cannot arrest a ship that does not fly its flag on the high seas, whereas the Security Council can demand a blockade and derogate from the freedom of the sea. The Security Council does not violate the freedom of the sea and does not violate the non-use of force, but it derogates from it. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 2.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a2 article 2]]] | |||

The freedom of the sea, the non-use of force and other standards do not bind the Security Council as it binds a State, the Security Council is not bound by these standards it can provide for other regimes. These other plans will even have legal priority over other plans and agreements under section 103.[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 103.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a103 article 103]]]As for customary law, assuming it is applicable to the Security Council, the decision of the Security Council will have priority under the lex speciali rule. | |||

The absence of legal limitations is reflected in the complete absence of a power of the International Court of Justice to review the legality of Security Council decisions; the Court does not have the power at the request of a United Nations Member State that would feel aggrieved in this right to review Security Council decisions. The Court has no jurisdiction in this matter, which was entirely intended in 1945, because the League of Nations had been totally legalistic, which had bad press and immobilized the Security Council of the League of Nations. | |||

== What are the limits of the Security Council? == | |||

These are solely political limits in line with the logic of the Charter, which is to be more political than legal in order to distinguish itself from the League of Nations. Only the vote is the only real limit, you need 9 votes out of 15. | |||

This implies bargaining and control, because one cannot act without a qualified majority, if there is not sufficient consensus the action is not decided by the Security Council and cannot be undertaken, what the minority will always call a "Security Council blockage". | |||

The strong executive stems from a more positive regime, i. e. from certain legal rules that strengthen the power of the Security Council. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 42.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a42 article 42]]] | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 103.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a103 article 103]]] | |||

== | == Two rules further strengthen the Security Council. What are these provisions? == | ||

First of all, Article 25 to be read in conjunction with Article 2 in paragraph 5. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 2.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a2 article 2]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 2.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a2 article 2]]] | ||

| Ligne 206 : | Ligne 182 : | ||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 25.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a25 article 25]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 25.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a25 article 25]]] | ||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 49.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a49 article 49]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 49.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a49 article 49]]]Simply put, Security Council decisions under Chapter VII are either legally binding or binding on Member States, they must be implemented. | ||

In addition, the members of the United Nations must assist each other in the implementation of Security Council measures, as recalled in Article 2, paragraph 5 and Article 49. | |||

Finally, it is necessary to recall Article 103 of the United Nations Charter. | |||

If there is a conflict for members of the United Nations between an obligation under the Charter and an obligation under another treaty such as, for example, a trade treaty, the lex speciali and lex posterior are not applied but the primacy of the obligation under the Charter. | |||

If there is an arms embargo on State X and State Y has a treaty with the target State of sanctions committing it to deliver arms to it, then that treaty is not invocable, because the embargo obligation prevails for the United Nations member that has undertaken it. | |||

All this strengthens the Security Council. | |||

Contrary to what many people, and almost all journalists, believe, a negative vote by one of the five permanent members of the Security Council is not a veto. | |||

The veto only applies when we have a decision that would otherwise have been adopted as to whether we have a 9:1 majority. | |||

If we have a majority of 9 is that the decision would be invoked because there is the required majority, then we look at whether one of the five permanent members voted "no", then in this case we will say that he issued a veto. The majority is in favour, but there is a veto and the decision is not adopted. | |||

If one or more of the five members vote against, but the majority for a decision is not reached anyway, then there is no veto. | |||

Secondly, according to the text of the Charter when the right of veto applies, namely when the question is not a procedural matter - if the question is not procedural, there is no veto - in this case, it is taken as an affirmative vote of nine of its members in which all the votes of the permanent members are included. | |||

According to the text of the Charter in Article 27(3), in order for a decision to be adopted on matters that are not procedural, a majority of 9 affirmative votes must be cast in which the 5 permanent members must be, therefore they must have voted in accordance with the text in the affirmative, the five permanent members must have voted "yes".[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 27.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a27 article 27]]]According to subsequent practice, this was changed very early on following the Iranian crisis and the presence of Soviet troops after the Second World War in Iran. | |||

A decision is now considered adopted if there is no contrary vote by one of the big five; therefore, unlike the text of the Charter, abstention is not considered a veto. In the text of the Charter, it is sufficient to abstain to ensure that the decision is not adopted, to abstain is not to vote in favour. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 27.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a27 article 27]]] | According to the subsequent United Nations practice accepted by the International Court of Justice and endorsed in the 1971 Namibia case, it is on the contrary the negative vote of one of the five permanent members that counts as a veto. | ||

A resolution that passes with a majority of 9 out of 15 is possible with 5 abstentions of the five permanent members is possible and a decision is invoked in such cases. | |||

This has changed because the Soviets understood relatively early on that it was better to be able to abstain without blocking a resolution, because it gives more flexibility to foreign policy, there is a greater nuance in its foreign policy. | |||

Thus it is possible to mark an opposition without blocking, one can bargain without preventing the resolution. This practice has never been challenged, the Charter has been amended by many things according to subsequent practice. | |||

When can the Security Council act by taking the extraordinary measures it can take under Chapter VII? | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 39.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a39 article 39]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 39.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a39 article 39]]] | ||

The vault article is article 39, which states that the Security Council may take measures such as sanctions in article 41 or military measures in article 42 in three cases, i. e. there are three conditions, events that trigger the Security Council's possible action. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 41.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a41 article 41]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 41.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a41 article 41]]] | ||

| Ligne 256 : | Ligne 226 : | ||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 42.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a42 article 42]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 42.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a42 article 42]]] | ||

In other words, the Security Council must first qualify a certain situation as X, Y or Z and if it succeeds in doing so, the door is opened to take sanctions or other measures, or even military measures. This is the first key to ensuring that the Security Council can take action: | |||

# | #threat to peace | ||

# | #breach of the peace | ||

# | #act of aggression. | ||

If the Security Council decides on an act of aggression, it may take measures, including by force, if the Security Council decides on a breach of the peace, it may also take measures. | |||

== | == What is the difference between "breach of the peace" and "act of aggression"? == | ||

In the breach of the peace, the Security Council proceeds by a completely neutral and objective assessment; by breach of the peace it means that the peace is no longer there and since the mission of the Security Council is to maintain the peace, action must be taken. | |||

In aggression there is a legal concept which is that the breach of the peace is only a determination of a fact, aggression is quite a legal connotation, moreover if an act of aggression is determined, there is an aggressor. | |||

In the case of Iraq and Kuwait in 1991 there was an act of aggression, Iraq is the aggressor. The Security Council almost never calls anything an act of aggression, because it is a political and diplomatic body and prefers to remain as neutral as possible. | |||

Since it is not necessary to qualify something as aggression in order to take action, it is better to refrain from doing so. The Security Council does not like to infer legal concepts that could have legal consequences and what is more diplomatic, it is not very good to tell someone that he is the aggressor, we deprive ourselves of diplomatic means. | |||

The threat to peace allows the Security Council to take preventive action. There is no breach of the peace, there is no hostility, there is no need to restore peace because it is not broken. There are situations that suggest such a rupture, such as bellicose speeches, armies that are amassed, threats of intervention are threats to peace. | |||

In its practice, the Security Council has been much broader, has assumed a governance or quasi-governance function; it has described very diverse situations such as not extraditing certain terrorists in the Libyan case, or the fact that there were refugee flows in the Haitian case, or the fact that certain treaties have not been ratified on non-proliferation or the prohibition of certain weapons as threats to peace. | |||

The Security Council has had a broad view of the threats to peace. | |||

In short, the Security Council has a very broad interpretation of what is now the threat to peace, and anti-terrorist actions are all based on the threat to peace. | |||

This is a very broad interpretation, because the Security Council tries to play a little bit with the world government, which it is not always well equipped to do. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 2.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a2 article 2]]] | It is a body that is not well equipped to legislate. This is understandable when it comes to military action, but when it comes to legislating for anti-terrorism from the point of view of democratic theory, it remains a very narrow basis for taking action, but the advantage is that binding measures can be taken under section 25 of the Charter. If we went through the General Assembly, which is much more legitimate, because it does not have the effectiveness of action, it can only recommend, so we do not have the effectiveness of action.[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 2.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a2 article 2]]] | ||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 25.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a25 article 25]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 25.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a25 article 25]]] | ||

== | == What are the problems of legal interpretation that we have as a result of this provision? == | ||

Undoubtedly there are legal aspects and legal problems within this provision. | |||

This article is considered to reflect customary law, obviously this article is addressed to members, but from the point of view of general international law this provision has its parallel in customary law confirmed by the International Court of Justice in the 1986 Nicaragua case. | |||

=== « Force » === | === « Force » === | ||

The word "force" is not insignificant, if the Charter had been written a few years before we would have used the word "war", but here it is the term force that appears. Between "war" and "force" there is a significant legal difference. War from the point of view of law is a legal state, a subjective legal situation. | |||

War in its traditional form was considered a legal act. By declaring war, a State could put itself in a "state of war" and thus enjoy all the special rights and duties conferred on it by this legal situation, which was called war. | |||

Conversely, not all use of violence was a war, it had to be declared, because it was an act of will. So in the 1920s, when there were armed reprisals by states on foreign territories, there was no war. | |||

Following the bombing of Corfu by the Italians in 1923, the Italians justified their act as a reprisal operation following a violation of international law by Greece since an Italian general sent for an investigation was murdered, so it is only a simple armed reprisal. | |||

If we had the formula "war" in the Charter, the situation in Corfu would not be prohibited, there would be the use of "force", but not "war". | |||

Moreover, for years States have played on this by avoiding calling something war in order to avoid applying the laws of war, to avoid prohibitions on the use of war; the Charter cuts short these difficulties, because it is not related to war, but goes directly to the point. | |||

At the same time, it is accepted that Article 2(4) applies only to military force, which is the physical force of the State. A distinction is made between physical strength and influence. | |||

For the non-use of force alone is physical and military force, including with modern means; on the other hand, political or economic pressure must be analysed in the principle of non-intervention in internal affairs, only certain particularly strong pressures are prohibited through the principle of non-intervention. | |||

=== « Menace » === | === « Menace » === | ||

Members of the organization shall refrain from the threat and use of force. Neither the use of force nor the threat of force are absolute prohibitions. The use of force is not absolutely prohibited, in self-defence force can be used, logically one can also threaten to use force if the use of force was itself lawful. There are situations of chiaroscuro, not all threats are prohibited. | |||

=== « dans leurs relations internationales » === | === « dans leurs relations internationales » === | ||

Once again, Article 2.4 only applies to conflicts between States, one cannot threaten or use force against another State. On the other hand, Article 2.4 does not apply at all within the territory of a State, with the remarkable consequence that it does not prohibit people from taking up arms to fight their government, it is called an "insurrection", and that international law does not prohibit the government from retaliation on rebellion by the use of force; it is within a State, but not in international relations. However, there may be a threat to peace that requires action by the Security Council, but we are not in the 2.4. | |||

Knowing what is covered by domestic and international law is not always easy. For example, to know if an armistice line transforms the space it crosses into an international space or if the armistice line does not transform the spaces it crosses into an international space - obviously the armistice lines are not recognized borders -. | |||

Thus, the general rule is that there is no 2.4 for non-international armed conflicts. | |||

Article 51 of the United Nations Charter deals with self-defence.[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 51.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a51 article 51]]]The first thing, as with article 2.4, and as confirmed by case law, is that article 51 reflects customary international law, it is not an article applied only to members of the United Nations, at the same time and in parallel with article 51, a rule of customary law in the Nicaraguan case of the International Court of Justice of 1986, there is more or less the same article in customary international law. | |||

The second remark is that the rule is the non-use of force 2.4 and the exception is article 51; a State or States may/ may use force in self-defence, it is an exception to the general principle of non-use of force. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 51.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20012770/index.html#a51 article 51]]] | |||

In the design of the charter, Article 51 was a concession introduced relatively late and a whole series of states were afraid, as was the United States of America, which did not have the same position as since the outbreak of the Cold War. | |||

It is understood that first of all from a didactic point of view grasping architecture can help to better define things and from a legal point of view it can be of greater importance, because the exceptions are of fixed interpretation, if the exception is an exception the interpretation should tend to be strict and not broad. | |||

The third remark is that self-defence allows for both individual and collective self-defence. Self-defence was initially found in Chapter VIII. Collective self-defence means that in cases where several States are attacked and defended by a coalition of States, legally third States can assist a victim.[[Fichier:CHARTE DE l'OTAN - article 5.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://www.nato.int/cps/fr/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm Charte de l'OTAN] - article 5]]The fourth remark is that the terminology used in Article 51 differs from that of Article 2.4. Article 2.4 prohibits the use of force, article 51 allows self-defence in the case of armed aggression. | |||

The English text differentiates, it speaks of an "armed attack", the two notions are not exactly identical and this is not the only point where the versions differ; it is a trace of the late drafting of this article. | |||

We understand that there is a difference, there must be cases where force is used against which self-defence is not advisable, there may be a use of force that is not powerful enough to be armed aggression, but if the use of force does not reach the threshold of armed aggression there is no self-defence. | |||

The case law tries to define the threshold between a use of force - 2.4 - and the use of armed force - Article 52 - which are not concentric. Article 2.4 uses any use of force while article 51 authorizes the use of anarchic force only if a State has received an armed attack in such a proportion. | |||

It is a question of keeping the peace and not immediately opening the escalation of force, but also of blocking the way to unilateralism. International law tries to take this situation into account by restricting the use of force as much as possible and consistent with the order that the Charter is trying to establish. | |||

The practice of the Charter shows that States like Israel have a broader conception and that any use of force can lead them to react. The text of the Charter does not give way to these arguments, because it makes a distinction. | |||

== Qu’est-ce qu’exactement une agression armée ? == | == Qu’est-ce qu’exactement une agression armée ? == | ||

The answer can be found in the reply in United Nations General Assembly resolution 3314 of 14 December 1974 and more particularly in article 33<ref>[http://legal.un.org/avl/pdf/ha/da/da_ph_f.pdf Définition de l’agression - Résolution 3314 (xxix) de l’assemblée générale]; United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law</ref>. | |||

Resolution 3314 is the resolution on the definition of aggression. | |||

[[Fichier:Résolution 3314 des Nations Unies sur la définition de l'agression - article 3.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/french/documents/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/3314(XXIX)&TYPE=&referer=https://www.un.org/french/documents/ga/res/29/fres29.shtml&Lang=F Résolution 3314 des Nations Unies sur la définition de l'agression] - Article 3]] | Article 3 lists a series of situations considered as aggression under international law. In this article and in the list of letters going to g we find the cases that are typically cases of armed aggression, it is a list that is not exhaustive.[[Fichier:Résolution 3314 des Nations Unies sur la définition de l'agression - article 3.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/french/documents/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/3314(XXIX)&TYPE=&referer=https://www.un.org/french/documents/ga/res/29/fres29.shtml&Lang=F Résolution 3314 des Nations Unies sur la définition de l'agression] - Article 3]]In article a we find the invasion which is typically an armed attack, but more subtle cases are found as in letter g which is the irregular arming of armed groups. | ||

Another remark is that there is an increasingly urgent problem of who should be the attacker and the attacked, who should be the aggressor and the attacked. | |||

In the initial vision of the Charter there is no doubt that both sides consider that there are States, but Article 51 in its text is not so limited, let alone the customary rule does not manifestly contain such a limitation. | |||

Especially since the attacks of Al Qaeda on 11 September, the question has been raised as to whether the aggressor could be other than a State entity, namely a terrorist group. | |||

Al Qaeda attacks could be brought back to the Government of Afghanistan, but if this hypothesis is ignored, the question remains as to whether the State of Afghanistan that has not committed an attack, then can force be used? | |||

The law is moving. We will not comment on the issue, but so far the International Court of Justice has refused to extend the notion of self-defence beyond a state attacker. The Court requires that even if an armed group is armed, there must be an attribution to a State. | |||

The Court is therefore strict, based on the case of the armed activities of the Republic of Congo against Uganda in 2005<ref>[http://www.credho.org/credho/travaux/biad162006.pdf Affaire des activités armées sur le territoire du Congo, République démocratique du Congo c. Ouganda (Arrêt du 19 décembre 2005)] par Abdelwahab BIAD Maître de conférences à l’Université de Rouen Membre du CREDHO </ref><ref>[http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/116/10455 International court of justice reports of judgments, advisory opinions and orders case concerning armed activities on the territory of the congo] (democratic republic of the congo v. uganda) judgment of 19 december 2005</ref><ref>[http://www.un.org/apps/newsFr/storyF.asp?NewsID=11572&Cr=CIJ&Cr1=RDC La CIJ condamne l'Ouganda à réparer les conséquences de son invasion de l'Est de la RDC] - Centre d'actualité de l'ONU</ref>. | |||

The Security Council, for its part, seems much broader, because in Resolution 1373, which follows the attack on the Twin Towers, the Council seems convinced that the United States should use the right of self-defence. This is an important issue. | |||

The role of the Security Council is the reason why Article 51 is included in Chapter VII. | |||

== Why didn't they add that to section 2.4? == | |||

This has been inserted rather in Article 5 since the Security Council has important functions, including in the case of self-defence. | |||

The general design of the Charter is that self-defence and a semblance of an interim right of self-defence will take some time between the time of the attack and the invasion and the decision of the Security Council; as a period of time will elapse anyway, it was considered that the right of self-defence should be granted, but in other words that when the Security Council acts the right of self-defence is subordinate to the Security Council. | |||

So there is a very clear hierarchy, as long as the Security Council has not acted, we can act in self-defence and continue even after the Security Council has taken measures; but in the event that the Security Council has taken a certain measure, we can no longer rely on a decision in self-defence. | |||

In other words, in the event of a conflict between a measure of self-defence and a collective measure taken by the Security Council in a binding manner, the measure of the Security Council prevails. | |||

Section 51 supplements section 103 of the Charter.{{citation bloc|[…] jusqu'à ce que le Conseil de sécurité ait pris les mesures nécessaires pour maintenir la paix et la sécurité internationale}}This sentence does not mean that a State can no longer rely on self-defence once the Security Council has taken a measure. | |||

It is not because the Security Council has taken a measure under, for example, Article 41 of the Charter that self-defence should be stopped, but only in the event of a conflict of measures that the Security Council's measures prevail. | |||

Finally, this is not found in the Charter, but in Nicaraguan customary law in 1886, self-defence is subject to the rules of necessity and proportionality. | |||

Necessity may mean that self-defence must be precisely necessary to defend against the ongoing aggression. All measures taken in self-defence must be necessary to repel the enemy attack. | |||

That is why it is prohibited under international law to take armed reprisals because a State is no longer covered by self-defence, because armed reprisal is precisely based on the fact that there is no longer a need to defend itself. | |||

In the case of an attack on a missile that has crashed somewhere, you have been hit, but the attack is over; you can defend yourself against this situation, but you must do it immediately. | |||

If we wait days and weeks, we are no longer in a state of necessity, we take it upon ourselves to punish another. | |||

When there is equal sovereignty between States, no one State is the judge of another. A sovereign state does not have the mission to distribute good and bad points to another state, otherwise sovereignty is superior to another. | |||

As for proportionality, it is not the same problem, it is not that measures must be necessary to repel, the attack is the question of the intensity of the response in relation to the type of aggression that has been suffered. | |||

Proportionality is more important in the low spectrum when you have suffered limited attacks and loses its intensity when you suffer a major attack, if you suffer an invasion you are no longer obliged to weigh the response, it makes no sense, you have to react on all fronts. | |||

The higher the spectrum, the lower the importance of proportionality and the lower the proportionality spectrum, the more important the spectrum of proportionality becomes. | |||

Between countermeasures and self-defence, there is a whole series of parallelisms. | |||

= Neutrality = | |||

Three remarks must be made about neutrality: there is ordinary neutrality and perpetual neutrality. | |||

There are few States that are generally subject by treaty obligations to an obligation of perpetual neutrality, in the vast majority of cases neutrality derives only from ordinary neutrality. | |||

Ordinary neutrality is the case of a State that is not obliged to stand still and makes a sovereign choice in the face of an armed conflict that erupts in the world, either to participate in this international conflict on the side of the aggressor in violation of the law, on the side of the aggressor in self-defence or not to participate in the armed conflict and remain neutral. | |||

Ordinary neutrality is not an issue and exists as a regime only in the event of the outbreak of an international armed conflict, third States take a decision to enter or remain outside it, in the absence of an international armed conflict there is no neutrality status. | |||

A State under its sovereignty has the possibility to make this choice under international armed conflict. | |||

In some collective self-defence treaties, there is an obligation to assist, but this is specific international law based on treaties. | |||

International treaty law requires that a State, whatever happens, is always neutral and this is Switzerland's status under the Final Act of the Vienna Conference of 1815. | |||

Switzerland was not represented at this conference, but after the intervention of the major powers it accepted to become a neutral state, the powers also found their interest, because Switzerland was in a particularly sensitive part of Europe between Austria, Habsburg and France. | |||

Keeping peace in Europe was therefore based on the neutralisation of Switzerland from the point of view of the great powers, not only, but above all. | |||

Perpetual neutrality implies that the neutral state has obligations in a state of peace, it is obliged to remain neutral and in time of peace, it must take measures to remain neutral. This means that the neutral state cannot perpetually be part of an alliance in which it can be led to use force as part of a defensive alliance, this is not possible for the perpetually neutral state. | |||

Since there is an obligation to defend neutral territory in the event of a violation, there must be a minimum number of armies since, by virtue of neutrality, one is obliged to do so. | |||

One further remark, as we have already mentioned, neutrality exists only in the context of an international armed conflict, there is no neutrality in the sense of international law outside an international armed conflict that is an armed conflict between several States. | |||

At that point, there is occasional or even perpetual neutrality. | |||

In a non-international armed conflict, there is no neutrality, there is no duty of neutrality that would automatically follow in this case. There is a duty not to interfere in the affairs of a State in the grip of a civil war; even more so, there is no neutrality outside any armed conflict and therefore in a state of peace except for the State in a situation of perpetual neutrality. | |||

In terms of neutrality policy, we can say what we want, but we must distinguish between the right of neutrality, which is extremely limited, which only concerns international conflicts, and everything else is the policy of neutrality, which we can discuss. | |||

== What is the content of the right of neutrality? == | |||

The neutral has duties of abstention, impartiality and prevention in the event of permanent neutrality. | |||

Recent doctrine and also the 1993 Federal Council report consider that neutrality applies only in inter-state conflicts. On the other hand, it is considered that neutrality is not applicable in accordance with Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, even if the Security Council decides to apply force. In the case of sanctions, it is not considered to be a measure that concerns neutrality. | |||

In order to understand, neutrality does not apply to peaceful measures of the Security Council or to measures where the Security Council provides for the use of force, but this does not mean that a State is obliged to use force. | |||

The Security Council authorises Member States to use force when necessary, authorises Member States to take all necessary measures, an authorisation is a possibility, a neutral State is not obliged, it cannot oppose it, but is not obliged to participate. | |||

= Annexes = | = Annexes = | ||

Version actuelle datée du 13 septembre 2018 à 03:51

| Professeur(s) | Robert Kolb |

|---|

Lectures

The principle of non-use of force and international peacekeeping[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The principle of non-use of force and international peacekeeping is a crucial issue in public international law. The moment is not free of irone for this kind of subject while the events in Syria have kept us on our toes in recent weeks.

We will address the legal position in relation to the principle of non-use of force and international peacekeeping.

The first remark concerns the importance of the question of peacekeeping and the non-use of force; the importance of the question comes from the fact that the primary purpose of any legal order is to ensure social peace and to amend private peace. In German, it is said "Jede Ordnung ist Friedensordnung", in other words that every legal order is an order of peace.

The issue is important, because peacekeeping is a condition for maintaining social peace and any work of civilization. We will not deal with a myriad of subjects if the primary problem in our society was survival.

The question of social order in the sense of peacekeeping is the very first question that a legal order must address, because the law fights anarchy. Everything to everyone who judges his causes himself is imposed by force such as he perceives them himself is the use of force by all social bodies, to police society we must address the situation where members of the social body use force.

For centuries, and especially in the Middle Ages, lords could use private justice, resulting in a general situation that manifested itself through endemic wars and regular destruction.

If the issue is so essential in domestic law, that the State has been created to ensure peace, then the question arises almost even more seriously in international relations, it is not this or that lord who can cause trouble, but powerful States with weapons.

The nuisances of armed conflicts are particularly high and the social peace function is a particular problem of acuity.

The second remark is that for a long time, since the 17th century and the Westphalian treaties, the question of peacekeeping and the use of force was not a fundamental issue of international law.

If the question was so important, why wasn't it addressed in traditional international law?[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The arrangement of classical international law was an arrangement of indifference to the non-use of force; States could use force for their own political causes without the law interfering with it.

In the 19th century, the answer would have been quite simple, to know if France and the United States want to intervene in Syria would come out of their own political decision and from the point of view of law, there is only the obligation to declare war.

On the other hand, traditional law attached consequences to the entry into war. If a State chose to use force, there were consequences "in bello", i.e. on the way war was conducted, with a prohibition on the use of certain weapons that were too destructive or on the killing of prisoners of war, as well as on the neutrality of States that were not belligerents.

What we have just mentioned, the "durante bello" obligations, have nothing to do with the political choice to enter or not to enter a war; some legal consequences followed from the entry into the war, but the law remained instrumental.

The classical law was too weak to assume such a function. States in the 19th century did not want to ensure limitations on their ability to wage war; a sovereign state because it is sovereign automatically has by virtue of its sovereignty the right to wage war. In 1879, Chile attacked Bolivia, which is not illegal under 19th century law.

The second question is why international law has changed?[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

States did not want stronger intervention, the choice to go to war was a sovereign one.

Why do modern texts such as the United Nations Charter impose a prohibition on the use of force subject to certain exceptions?[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Over time, the importance of maintaining peace in a more modern and different society has been recognized. International society has believed its interdependencies; in these increasingly complex and balanced environments, it was in the public interest to maintain peace.

There are also more specific aspects that explain the change, all these more specific aspects have in common that they symbolize a war that has become more and more destructive and devastating.

The war of the 18th and 19th centuries was often a war of little destruction, there were well formed and reduced armies until the Napoleonic wars. These professional soldiers could fight the battlefields with limited impact on society, on the other hand kings and dynasties maintained acceptable relationships, the rule was only a rule of the game to extend its domination. All this actually tends to contain the war.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries in particular, these idyllic assumptions disappeared, and modern warfare was considerably brutalized to the point of becoming a scourge.

We have a whole series of reasons for this evolution:

- the fact that war becomes a national cause with the conscription of a mass army and the hatred that mobilizes the nation leading to a war of a completely different scale.

- the technological evolution leading to modern weapons as well as the development of aviation during the First World War.

- industrialisation, which also contributed to the brutalisation of war, because modern war from the 19th century onwards is no longer necessarily won at the front, but upstream with industrial production, an industry that can support the war effort is needed. This means that the opposing belligerent will no longer only hit the combatants at the front, but also the industries, inducing that civilians will also be affected.

War has changed in nature, it has become a disaster and a cataclysm; in view of this political and social transformation of war, we wanted to give it another answer. What was considered as a legitimate means of settling a dispute in the past relating to the classical vision, in the 20th century such a logic was no longer possible, war is a scourge and can degenerate into generalized wars, that is why there was a fundamental change of perspective in the matter.

The United Nations Charter is the founding text on this subject[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

How does the Charter fit into international peacekeeping?[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The first remark is that the Charter is based on the idea and principle that the use of force should be repressed as much as possible in international relations, at least when it is used by individual States.

War is no longer seen as a means of foreign policy by which to settle a dispute or impose one's own interests.

However, the Charter is not a pacifist instrument. What the Charter does not want individual States to use force for causes that seem good to them, the Charter recognizes that force must sometimes be used, it reserves it on the one hand for States when they act in self-defence, that is, that a State is attacked by armed forces can and must resist by force, the Charter recognizes the usefulness of "police operations". The Charter recognizes that there are situations in international relations where force must be used to prevent greater harm from occurring.

The judgment of such a situation is reserved to the United Nations and more particularly under Article 24, paragraph 1 to the United Nations Security Council. Not that this body is particularly angelic, but for the Charter, it is the only body that combines strength with a certain force of control and equity.

The Charter tries to do the same as we have in domestic law, we would legitimately be concerned if everyone could use force for causes that seem good to them. On the other hand, when there is a need to use force, it is necessary to turn to the police. For the Charter, the police is the Security Council, a body that may not be ideal, but it guarantees a minimum of multilateralism that means that everyone cannot do what they want.

Experiments of generalized force were already made in the 19th century leading to the politics of the gunboat and the First and Second World War.

It is remarkable that, unlike Russia and China, in the West since the previous one in Kosovo, a whole series of politicians believe that either we go through the Security Council and authorise action, but if it does not do so we proceed to a unilateral reaction, either with or with the Council, but this is not the legal situation, from the point of view of law only the Security Council can use action or there is use of force unless there is an assumption of self-defence.

It is interesting to see that Western leaders no longer seem to take Article 2(4) seriously.

The argument that the Security Council is blocked is a magnificent one. As if by chance, the Security Council is always blocked when China or Russia uses a veto, but never when the West does. In the past the USSR used the most vetoes today it is the United States.

In Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, "Action in the event of a threat to the peace, breach of the peace and act of aggression", we have the competence of the Security Council.

The competences of the Security Council go beyond the framework of ordinary international law, the Security Council can do things that would otherwise be illegal under international law, which States cannot do, but which are recognised by the Security Council, which has a police function. The Security Council can take peaceful sanctions or non-military coercive measures such as embargoes or the Security Council could take military action with United Nations military forces, but since the United Nations has never received military forces it cannot itself use military force.

In United Nations practice, we have come to an alternative regime which consists in authorizing Member States to use force when the Security Council gives them the power to do so through a resolution. The established formula is "authorizes Member States to take all necessary measures (...)". Using this formula means that the use of force has been authorized if necessary.

Peacekeeping sometimes means having to act urgently to prevent aggression, stop massacres, react to serious violations of the law, but as in domestic law we prefer the police to do so, in the same way we try in international law to centralize this in multilateralism.

Section 51 deals with self-defence, or "self-defence" in English.

Thus, we have a triptych in the Charter that is coherent in itself, although it is not always truly functional. On the one hand, States are told not to use force as a means of foreign policy, there is no desire for anarchy in the use of force by everyone and the fact that, through the use of force, the strongest is imposed on the weakest, which is neither the mark of civilisation nor the mark of justice.

On the other hand, the Charter provides for the use of force and organizes it, but centralizes it in a body representing the international community, namely the United Nations and the Security Council, on which the five permanent members sit, and it must take decisions when there are citizens who threaten international peace.

Someone is set up to ensure that the necessary actions are taken, including by force. There is one exception, in the case of armed aggression a State can and must defend itself, this is the exception of self-defence. Self-defence is only granted in the event of armed aggression.

If self-defence were to be opened up to every violation of international law, States would be able to intervene anywhere in the world as in the case of serious human rights violations. If we open this way, we open the way for the use of force to be much more important than the Charter wanted to authorize it beyond the idea of repressing anarchy. However, no State acts for reasons other than war for altruistic interests.

Armed retaliation is prohibited because self-defence is only granted as an exception to self-defence because it is necessary for self-defence and therefore we must concede this because a state needs self-defence to defend itself.

On the other hand, armed reprisals do not represent the situation of necessity because the danger and arrested, there is nothing left to protect directly at this stage. In this case, military action is no longer an action of necessity, but a punishment action.

The mission of the International Criminal Court is to prosecute and punish persons; in principle, a State does not have the mission and competence to punish another State because between States there is the principle of equal sovereignty. States are peers and one does not have to punish the other.

Sometimes it is difficult to know very precisely whether it is an armed reprisal or not, as Israel did when it used reprisals after the fact.

Chapter VII is the heart of the United Nations Charter, but only somewhere, actually.

Chapter VII is the chapter devoted to collective security action, it is the great hammer, it is unique in international relations that a body has such extensive competence as the Security Council has under this chapter.

It is a chapter dedicated to action, as the title of Chapter VII makes very clear, "action in the event of a threat to the peace, breach of the peace and act of aggression", while the rest of the Charter faithfully reflects the other aspect of the United Nations, namely that it is an organization where discussion, coordination and cooperation take place.

The Security Council is supposed to act and we want it to be able to act with as many possibilities as possible.

Chapter VII is the one that captures the imagination the most. Everyone is more or less familiar with Chapter VII, but in the Charter, Chapter VII is not in substance the most important, because the drafters of the Charter hoped that Chapter VII would not have to be applied.

As the Charter tries to preserve peace, it tries to do so without the need for action to maintain or restore peace in extremis. The Charter strives to ensure that preventive action is avoided.

Economic and social actions and the peaceful settlement of disputes, these chapters VI and VII have been inserted in the Charter, competences have been conferred on the world organisation in this field with the simple aim of having more diversified actions in order to maintain peace.

The drafters of the Charter were aware that if there is a great disparity in the world, it does not guarantee peacekeeping. If there are such strong differences between States, there is a risk of violence; we try to deal with it not because if economic and social causes were valid causes in themselves, but from 1945 they were perceived as a means by which peace could actually be maintained; we work on the fact that there would be better conditions so that peace could prevail.

The Charter tries to deal with these things with limited resources, because you cannot settle a dispute against the will of the people concerned, you cannot impose the settlement of a dispute.

Chapter VII in the logic of the Charter is what is fundamental and distinguishes the current organization from the weakness of the League of Nations and at the same time the Charter is not focused on Chapter VII.

The other remark on Chapter VII is that the drafters of the Charter wanted the Security Council to be able to act with as few obstacles as possible.

The logic of the "highway" is that of the strongest possible executive that has the means to act promptly and decisively.

First of all, the Security Council is centred around major powers, which had not been the case in the League of Nations. The Charter is more realistic, without the great steps of hope of imposing peace, only a preponderant force can be imposed on the aggressor.

The strong executive is characterized by the absence of legal limits to the Security Council's action. States cannot legally do a whole series of things when the Security Council can do almost anything. In law, the Security Council is discussed, especially in terms of ius cogens, i.e. some fundamental norms that it cannot violate, otherwise the Security Council is free.

A State cannot use force unilaterally under article 2, paragraph 4, while the Security Council may, because article 42 gives it absolutely discretionary power to use force if it considers it necessary.

A State cannot arrest a ship that does not fly its flag on the high seas, whereas the Security Council can demand a blockade and derogate from the freedom of the sea. The Security Council does not violate the freedom of the sea and does not violate the non-use of force, but it derogates from it. The freedom of the sea, the non-use of force and other standards do not bind the Security Council as it binds a State, the Security Council is not bound by these standards it can provide for other regimes. These other plans will even have legal priority over other plans and agreements under section 103.

As for customary law, assuming it is applicable to the Security Council, the decision of the Security Council will have priority under the lex speciali rule.

The absence of legal limitations is reflected in the complete absence of a power of the International Court of Justice to review the legality of Security Council decisions; the Court does not have the power at the request of a United Nations Member State that would feel aggrieved in this right to review Security Council decisions. The Court has no jurisdiction in this matter, which was entirely intended in 1945, because the League of Nations had been totally legalistic, which had bad press and immobilized the Security Council of the League of Nations.

What are the limits of the Security Council?[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

These are solely political limits in line with the logic of the Charter, which is to be more political than legal in order to distinguish itself from the League of Nations. Only the vote is the only real limit, you need 9 votes out of 15.

This implies bargaining and control, because one cannot act without a qualified majority, if there is not sufficient consensus the action is not decided by the Security Council and cannot be undertaken, what the minority will always call a "Security Council blockage".

The strong executive stems from a more positive regime, i. e. from certain legal rules that strengthen the power of the Security Council.

Two rules further strengthen the Security Council. What are these provisions?[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

First of all, Article 25 to be read in conjunction with Article 2 in paragraph 5.

Simply put, Security Council decisions under Chapter VII are either legally binding or binding on Member States, they must be implemented.

In addition, the members of the United Nations must assist each other in the implementation of Security Council measures, as recalled in Article 2, paragraph 5 and Article 49.

Finally, it is necessary to recall Article 103 of the United Nations Charter.

If there is a conflict for members of the United Nations between an obligation under the Charter and an obligation under another treaty such as, for example, a trade treaty, the lex speciali and lex posterior are not applied but the primacy of the obligation under the Charter.

If there is an arms embargo on State X and State Y has a treaty with the target State of sanctions committing it to deliver arms to it, then that treaty is not invocable, because the embargo obligation prevails for the United Nations member that has undertaken it.

All this strengthens the Security Council.

Contrary to what many people, and almost all journalists, believe, a negative vote by one of the five permanent members of the Security Council is not a veto.

The veto only applies when we have a decision that would otherwise have been adopted as to whether we have a 9:1 majority.

If we have a majority of 9 is that the decision would be invoked because there is the required majority, then we look at whether one of the five permanent members voted "no", then in this case we will say that he issued a veto. The majority is in favour, but there is a veto and the decision is not adopted.

If one or more of the five members vote against, but the majority for a decision is not reached anyway, then there is no veto.

Secondly, according to the text of the Charter when the right of veto applies, namely when the question is not a procedural matter - if the question is not procedural, there is no veto - in this case, it is taken as an affirmative vote of nine of its members in which all the votes of the permanent members are included.

According to the text of the Charter in Article 27(3), in order for a decision to be adopted on matters that are not procedural, a majority of 9 affirmative votes must be cast in which the 5 permanent members must be, therefore they must have voted in accordance with the text in the affirmative, the five permanent members must have voted "yes".

According to subsequent practice, this was changed very early on following the Iranian crisis and the presence of Soviet troops after the Second World War in Iran.

A decision is now considered adopted if there is no contrary vote by one of the big five; therefore, unlike the text of the Charter, abstention is not considered a veto. In the text of the Charter, it is sufficient to abstain to ensure that the decision is not adopted, to abstain is not to vote in favour.

According to the subsequent United Nations practice accepted by the International Court of Justice and endorsed in the 1971 Namibia case, it is on the contrary the negative vote of one of the five permanent members that counts as a veto.

A resolution that passes with a majority of 9 out of 15 is possible with 5 abstentions of the five permanent members is possible and a decision is invoked in such cases.

This has changed because the Soviets understood relatively early on that it was better to be able to abstain without blocking a resolution, because it gives more flexibility to foreign policy, there is a greater nuance in its foreign policy.

Thus it is possible to mark an opposition without blocking, one can bargain without preventing the resolution. This practice has never been challenged, the Charter has been amended by many things according to subsequent practice.

When can the Security Council act by taking the extraordinary measures it can take under Chapter VII?

The vault article is article 39, which states that the Security Council may take measures such as sanctions in article 41 or military measures in article 42 in three cases, i. e. there are three conditions, events that trigger the Security Council's possible action.

In other words, the Security Council must first qualify a certain situation as X, Y or Z and if it succeeds in doing so, the door is opened to take sanctions or other measures, or even military measures. This is the first key to ensuring that the Security Council can take action:

- threat to peace

- breach of the peace

- act of aggression.