Introduction to the Law : Key Concepts and Definitions

Based on a course by Victor Monnier[1][2][3]

Introduction to the Law : Key Concepts and Definitions ● The State: Functions, Structures and Political Regimes ● The different branches of law ● The sources of law ● The great formative traditions of law ● The elements of the legal relationship ● The application of law ● The implementation of a law ● The evolution of Switzerland from its origins to the 20th century ● Switzerland's domestic legal framework ● Switzerland's state structure, political system and neutrality ● The evolution of international relations from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century ● The universal organizations ● European organisations and their relations with Switzerland ● Categories and generations of fundamental rights ● The origins of fundamental rights ● Declarations of rights at the end of the 18th century ● Towards the construction of a universal conception of fundamental rights in the 20th century

In our exploration of the vast field of law, we embark on an intellectual journey through the principles and structures that underpin legal systems and shape interactions within our societies. This discussion does not simply define law in its most basic terms; it seeks to reveal how it permeates and guides fundamental aspects of community life. By examining concepts such as objective and subjective law, we seek to understand not only the rules that govern individual behaviour, but also how these rules reflect and influence social values and structures.

We will look at positive law and its interaction with natural law, a subject that reveals the tensions and balances between written laws and universal ethical principles. The example of the French Civil Code is a perfect illustration of how ideals of justice and equality, once seen as the domain of morality or philosophy, have been incorporated into positive law, reflecting changing societal perceptions over time.

By exploring legal institutions such as marriage and adoption, we recognise how law shapes and is shaped by human relationships. These institutions are not simply legal agreements; they reflect how society conceives of and values personal relationships and responsibilities.

The judicial process, with its states of affairs and devices, is another focal point of our discussion. Here, we reveal how legal decisions are made, highlighting the importance of interpreting the facts and applying the rules of law. Imperative and dispositive rules offer an insight into the dynamic between individual freedom and the constraints imposed by the law.

This discussion is more than an academic presentation; it is an exploration of how law shapes and is shaped by human values and social interactions. By better understanding these principles, we gain not only legal knowledge, but also a deeper perspective on society itself and our role within it.

What is law?[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The law is a coherent set of socially established and imposed rules of conduct that dictate the behaviour expected of members of a society. These rules, endowed with binding power, serve as a guide for human interaction, regulating interpersonal relations in a fair and predictable manner. At the heart of its function is the overriding objective of ensuring harmonious and peaceful coexistence within the community. The law acts as a peacemaking mechanism, mitigating and resolving conflicts between individuals. It also plays a crucial role in the structural organisation of society, protecting not only individual and collective interests, but also the goods that are essential for harmonious social functioning. Law is the fundamental pillar of social order, guaranteeing stability and justice within the community.

The law in society[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Society can be further redefined as a set of individuals who coexist within an organised framework, sharing common norms, values and institutions. This coexistence is not static, but rather characterised by a multitude of interpersonal relationships that are constantly developing and evolving.

Each member of society is involved in a dense network of interactions with others, forming a rich and diverse social fabric. These interactions are not simply occasional contacts; rather, they constitute a complex series of relationships that shape individual and collective experiences. These relationships are influenced by factors such as cultural norms, laws, beliefs and economic practices.

Society can be seen as a living organism, where each member plays a crucial role in maintaining and evolving its structure and culture. The constant interaction between individuals is not only a feature of society, but also the driving force that shapes and transforms it.

The organisation of society, public constraint and the legal order[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In any society, individuals face a range of constraints that influence and delimit their behaviour, choices and opportunities. These constraints manifest themselves in a variety of ways, reflecting the complexity and diversity of social structures. Laws and regulations are a major form of constraint in any society. Imposed by government authorities and other regulatory bodies, these legal norms aim to ensure public order, security and justice. While they are essential for maintaining order and protecting the rights of citizens, they can also limit certain individual freedoms, defining a legal framework within which individuals must act. Beyond laws, social and cultural norms exert a powerful influence on individual behaviour. Cultural values, traditions and expectations often determine what is considered acceptable or unacceptable in a society. These norms can sometimes restrict the expression of individuality and impose patterns of behaviour that correspond to collective expectations. Economic conditions are another significant form of constraint. Wealth, poverty and unequal access to resources significantly influence the options available to individuals. These economic constraints can limit opportunities for education, healthcare, decent housing and other essential aspects of well-being. Finally, the physical and geographical environment imposes its own limitations. Climate, topography and access to natural resources have a direct impact on people's lifestyles. These environmental factors can determine the types of economic activity possible, lifestyles, and even the challenges faced by individuals. These different forms of constraint are fundamental in defining the structure and functioning of societies. They contribute to social stability and the predictability of human interactions, while shaping the dynamics of community life. Public coercion refers to the legitimate power exercised by state authorities to impose standards, rules and decisions. This power extends to all state institutions and agents, including the government, law enforcement agencies, the judiciary and public administrations. The essence of this power lies in its ability to enforce laws and regulations, thereby guaranteeing public order and the safety of citizens. The concept of public constraint also extends to individuals or entities that hold rights recognised by law. In this context, the holder of a right is entitled to demand that this right be respected, if necessary by appealing to the authority of the State. For example, an owner can assert his property rights in the event of an offence, by requesting the intervention of the competent authorities to enforce compliance with the law. Public enforcement is therefore a fundamental part of the rule of law. It not only ensures that the law is enforced, but also serves as a mechanism for protecting the rights and freedoms of individuals within society. It is through this power that the State maintains order, justice and social cohesion.

The legal order is a complex, integrated system of legal rules that orchestrate relations within societies and between various entities on the international stage. This system encompasses a range of norms, from a country's domestic laws to the rules governing international interactions, providing a multi-layered regulatory framework. At the heart of this legal order are rules imposed by the rule of law and reinforced by sanctions for non-compliance. These rules serve as a foundation for justice and public order, ensuring that actions and interactions within society conform to accepted and ethical standards. For example, an individual who breaks a national law may be subject to criminal sanctions, reflecting the application of legal constraint to maintain social order. The legal order covers both national and supranational dimensions. At the national level, it comprises the constitution, laws made by parliament, administrative regulations and court rulings. These elements form the legal framework on which government structures and the rights and obligations of citizens are based. For example, a country's constitution defines the form of government and the fundamental rights of its citizens, while laws and regulations detail specific aspects of life in society, such as labour law or environmental protection. At international level, the legal system is made up of treaties, international conventions and globally recognised legal principles. These standards govern relations between states and other international players, covering areas such as international trade, human rights and humanitarian law. For example, the Geneva Conventions establish rules for the treatment of prisoners of war, illustrating how international law strives to maintain order and humanity even in times of conflict.

Taken as a whole, the legal order provides an essential structure for the stability and efficiency of societies, while ensuring a framework for the peaceful resolution of conflicts and the protection of rights and freedoms on a global scale. It represents not only a set of rules, but also a living system that evolves with social, economic and political change, reflecting the constant dynamics of life in society and international relations.

The function of law and social order[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Law, in its essence, is a system of rules established and applied by a society to regulate the behaviour of its members. These rules may vary greatly from one society to another, but they have in common the objective of maintaining order, protecting rights and property, and promoting the general welfare. Sanctions, for their part, are the means by which compliance with these rules is ensured. It represents a formal response to the transgression of established norms, and can take various forms, such as fines, prison sentences or other disciplinary measures. For example, if an individual commits theft, he or she is breaking not only a moral norm, but also a rule of law. In response to this offence, society's legal system may impose a sanction, such as a prison sentence, both to punish the offender and to deter others from committing similar acts. This repression of prohibited behaviour helps to preserve social order and reinforce confidence in the legal system. Thus, the presence of sanctions to punish breaches of the law is a crucial element in maintaining cohesion and stability in any society. It reflects the need for a balance between individual freedom and collective interests, ensuring that the rights and freedoms of some are not crushed by the actions of others.

The state plays a vital role in ensuring that society functions properly, a task that involves establishing and maintaining rules of discipline under the authority of a centralised government structure. This responsibility is based on several essential functions. Firstly, the state is responsible for creating and enforcing rules and norms that define appropriate behaviour and interactions within society. These rules, often formalised in the form of laws and regulations, serve to prevent chaos and promote a safe and orderly environment. The clarity and precision of these rules are crucial. Well-defined and comprehensible laws enable citizens to clearly recognise their rights and duties, thereby facilitating adherence to these norms and reducing the risk of misunderstanding or conflict. The authority of the State is manifest in its power to enforce these laws. This includes the maintenance of public order by the police, the trial and punishment of offences by the courts, and the enforcement of sentences. For example, in the event of a breach of road traffic laws, police officers are empowered to intervene, and offenders may be subject to penalties such as fines or, in more serious cases, prison sentences. In addition, the State has a duty to regularly adapt and update the legal framework to reflect social, economic and technological changes. This adaptability is essential to meet the emerging challenges and evolving needs of society. For example, with the advent of the internet and digital technologies, many states have developed new laws to regulate online activities, protect personal data and combat cybercrime. In this way, by establishing a legal and regulatory framework and ensuring that it is enforced, the State ensures order and security in society. These actions not only help to maintain peace and social cohesion, but also contribute to the development and overall prosperity of the community.

The law plays a fundamental role in facilitating peaceful coexistence within society. As a system of legal rules and norms, the law functions as an essential framework for regulating interactions between individuals, thereby ensuring social harmony and stability. One of the main functions of the law is to pacify human relations. It achieves this by defining acceptable behaviour and prescribing consequences for unacceptable behaviour. For example, civil law determines rights and obligations in contractual and family relationships, while criminal law establishes penalties for harmful behaviour such as theft or violence. By providing a systematic way of resolving conflicts and dealing with transgressions, the law helps to prevent disorder and promote justice. The law also serves as the foundation of social order. It creates a framework within which economic, political and social activities can take place in an orderly and predictable manner. By establishing clear rules and ensuring that they are applied, the law facilitates cooperation and mutual trust, which are essential to the smooth running of any society. So the law is not just a set of rules and regulations; it is a vital component of the social structure, playing a key role in preserving peace and order, and enabling people to live together productively and harmoniously.

The main purpose of law is to organise society and protect national interests, but also, and perhaps more fundamentally, to safeguard individual rights and freedoms. "I still don't know what law is, but I now know what a state without law is" The historical experience to which Vedel refers, that of the arrival of prisoners liberated from the concentration camps at the Gare de Lyon in 1944, highlights the tragic consequences of a state operating without respect for the principles of law. In such a context, the absence of adequate legal structures and protections opens the way to abuses of power, oppression and massive violations of human rights. The period of the Second World War and the horrors of the concentration camps represent perhaps the darkest and most poignant example of what can happen when the state acts without being constrained or guided by law. Vedel's observation is therefore a striking illustration of the need for a strong and respected legal system. The law, in its ideal form, must function as a safeguard against arbitrariness and abuse of power, while organising social, political and economic structures. It is essential for establishing and maintaining order, justice and freedom in any society. Thus, the historical experience highlighted by Vedel is an eloquent reminder of the fundamental role of law as a pillar of social order and protector of the fundamental rights of individuals.

Social order, in its broadest sense, is a complex structure that ensures the cohesion and harmonious functioning of society. It rests on a number of fundamental pillars which, together, enable a community to prosper and adapt to change. At the heart of this social order is a structured organisation that provides a framework for society. This organisation can take many forms, including governmental, legal, educational and other social institutions that define the rules of community life. These institutions are responsible for establishing the norms and laws that govern interactions between individuals and groups, thereby ensuring order and predictability in social relations. A key element of social order is the authority that directs and supervises the operation of these institutions. This authority, whether political, legal or otherwise, plays a crucial role in implementing laws and policies and in directing public affairs. The authority ensures that the laws are respected and that the decisions taken serve the general interest. The social order must also ensure the material and intellectual sustenance of its members. This means not only meeting basic physical needs, such as food, housing and health, but also promoting education, culture and access to information. By meeting these basic needs, the social order contributes to the well-being and fulfilment of individuals. Another fundamental aspect of social order is its ability to maintain a balance between divergent interests. In any society, different groups and individuals have different needs, desires and perspectives, which can lead to conflict. The social order, through its institutions and processes, seeks to harmonise these opposing interests, through negotiation, mediation and the implementation of equitable policies. Finally, the social order must be in a constant state of adaptation. Societies are dynamic; they evolve over time as a result of changes in mores, values, technologies and environmental conditions. An effective social order is one that is able to adapt to these changes, revising its laws, policies and structures to meet new challenges and opportunities. In short, the social order is a complex, multidimensional system that plays an essential role in structuring society. It ensures social cohesion by meeting basic needs, managing divergent interests and adapting to ongoing changes in society.

The many meanings of the word "law"[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The word "law", derived from the Low Latin "directum", suggests the idea of something that is direct or straight, as opposed to something that is tortuous or devious. This etymological origin clearly illustrates the concept of law as a clear and straightforward path to justice and fairness. From this perspective, the law is seen as a reliable and upright guide that steers individuals and society towards just and appropriate behaviour, and away from fraud, corruption and injustice. The term 'juridical', on the other hand, refers to everything that belongs to the law, or 'ius' in Latin. "Ius" derives from the Latin verb "iubere", meaning "to order". This root underlines the authority inherent in law - it is not simply a set of suggestions or advice, but rather a body of commands and obligations that govern the conduct of individuals and institutions. Moreover, 'iustus', meaning 'the just', is the origin of the word 'iusticia', meaning 'justice'. This highlights the intrinsic relationship between law and justice. The law is thus conceived as a tool in the service of justice, aimed at ensuring that each individual receives what is due to him or her and that decisions and actions are taken in a fair and balanced manner. These terms therefore reflect the founding principles of many legal systems: the idea that the law should lead to right, just and orderly actions, and that justice is the ultimate goal of all legal rules and regulations.

Objective law refers to the set of rules of conduct established by a society and binding on its members. These rules are characterised by their socially enacted and sanctioned nature, which means that they are created by recognised institutions (such as the legislature or the regulatory authority) and are subject to sanctions in the event of non-compliance. These rules of conduct encompass a wide range of norms, including laws, regulations, decrees and case law, which govern interactions within society. Their purpose is to maintain order, protect the rights and freedoms of individuals, regulate relations between people and institutions, and promote the general welfare. The term "Law" corresponds to this notion of objective law. It refers to the set of rules that are applied in a given jurisdiction. This notion encompasses not only written laws, but also the principles and practices that are recognised and applied by the courts. Objective law forms the legal structure on which society is based. It is essential to ensure social cohesion, fairness in the treatment of individuals, and predictability of the legal consequences of various actions and interactions within the community.

A subjective right is a faculty or power granted to an individual or group by objective law. This prerogative enables its holder to act in a certain way, to require certain conduct from others, or to prohibit certain actions, generally in his own interest or sometimes in the interest of others. These subjective rights can take different forms, such as property rights, contractual rights, or fundamental rights such as the right to freedom of expression or the right to privacy. For example, a property right allows its holder to enjoy and dispose of his property as he wishes, within the framework set by objective law. Similarly, in a contract, one party acquires the right to require the other party to perform certain agreed actions. The concept of "right" in English corresponds to the droit subjectif in French. It refers to a claim or interest legitimised by objective law. These "rights" can be protected or enforced through the legal system, and their violation can lead to reparation or sanctions. Subjective law is therefore a personal and individualised aspect of law, embodying the way in which objective law is translated into concrete prerogatives for individuals and groups. It is fundamental to the protection of individual interests and the achievement of justice in society.

Positive law encompasses all the legal rules that are effectively in force at a given time in a given society, be it a national entity or the international community. The term refers to the law as it is "laid down" or established, i.e. the law as it is actually formulated, adopted and applied. Positive law includes both objective and subjective law. As objective law, it includes laws, regulations, decrees and other legal norms enacted by the competent authorities. These rules define the general legal framework within which individuals and organisations must operate. For example, a country's civil code or criminal code are expressions of positive law as objective law. As subjective law, positive law also manifests itself in the rights and prerogatives granted to individuals or groups. These subjective rights are recognised and protected by positive law. For example, the right to property or the right to a fair trial are aspects of positive law that concern individual rights. Positive law is therefore the law that is actually applied and recognised in a given jurisdiction. It is distinct from "natural law", which is based on theoretical notions of justice and morality, and from "ideal law", which represents the law as it should be in an ideal society. Positive law is a dynamic concept, evolving with legislative changes, judicial decisions and social transformations. It is the concrete manifestation of law in the everyday life of societies.

Natural law is seen as a set of principles and values that transcend positive law. These principles are supposed to derive from human nature, reason or a higher moral order, and serve as the basis for the conception of justice and equity. Natural law is often associated with notions of ideal justice and moral duty. Unlike positive law, which is the law as established and applied in a given society, natural law is considered to be universal and immutable. It is not written down in legal texts, but is seen as inherent in the human condition or derived from human reason. The principles of natural law often serve as inspiration for the creation and interpretation of positive law. They are invoked to evaluate or criticise existing laws and to guide the drafting of new laws. For example, concepts such as the fundamental equality of all human beings or the right to liberty are ideas derived from natural law that have influenced many laws throughout the world. Because of its abstract nature and generality, natural law is often used as a reference for judging the correctness or legitimacy of positive laws. Throughout history, natural law has been invoked to challenge and change laws and practices deemed iniquitous or oppressive, such as slavery, segregation or the deprivation of civil rights. Natural law is concerned with universal moral and ethical principles. It represents an ideal of justice towards which positive law tends and provides a framework for evaluating and improving existing legal systems.

The French Civil Code of 1804, also known as the Napoleonic Code, was a major step in the consolidation of law in France after the French Revolution, representing a significant effort to unify and systematise civil law across the country. The French Civil Code was conceived with the objective of creating a body of civil law that would be uniformly applicable to all French citizens, regardless of the region in which they resided. Prior to the adoption of the Code, France was governed by a multitude of local laws and regional customs, which made the legal system complex and inconsistent. The Civil Code introduced a more uniform and centralised legal system, which contributed to the legal and administrative unification of France.

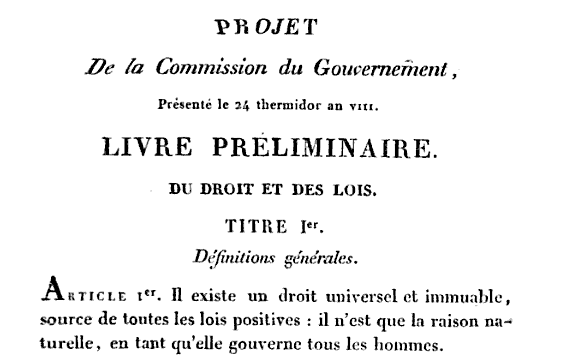

Article 1 of the Civil Code was particularly noteworthy, as it stated the existence of a "universal and immutable law", considered to be the source of all positive laws. This formulation reflected the influence of natural law ideas, emphasising the idea that positive laws should be based on principles of natural reason that govern human relationships. This meant an implicit recognition that the laws enacted should be in harmony with certain universal and rational principles, a concept that has profoundly influenced modern legal thought. The Civil Code had a considerable influence not only in France, but also in many other countries, where it served as a model for the reform and development of legal systems. It marked a decisive stage in the history of law, emphasising the codification of civil laws and the importance of universal and rational principles in the development of law.

The French Civil Code had a considerable and lasting impact, not only in France but also in many other parts of Europe, particularly those under French influence or domination in the early 19th century. Although the original title, which evoked the idea of universal and immutable law, was not retained in the final version of the Civil Code, the influence of its principles and structure on European law was profound. During the Napoleonic era, France extended its influence far beyond its traditional borders, bringing the Civil Code with it to occupied or annexed territories. For example, when Geneva became the prefecture of the Department of Lake Geneva, it was under French administration, so the French Civil Code also applied to the people of Geneva. This adoption of the Civil Code outside metropolitan France illustrates the spread of French legal ideas across Europe. As for Jura, which had been annexed by France, it retained the Civil Code even after becoming part of the Swiss canton of Berne. This fact testifies to the enduring adherence to certain legal principles and structures introduced by the Code, even after the end of French rule. The adoption and persistence of the Civil Code in these regions demonstrates its significant influence as a tool for legal modernisation and unification. The Napoleonic Code served as a model for civil law reform in many European countries and had a lasting impact on the conception and practice of law in the Western world.

For positivists, the law is strictly defined by the laws and regulations that have been officially established and adopted by the competent authorities. According to this view, only those norms and rules that form part of the corpus of positive law have binding force and can legitimately influence judicial decisions. In positivist thinking, concepts of natural law or moral principles have no binding legal status in themselves, unless they are explicitly incorporated into positive law. This means that for a judge, lawyer, legislator or any other jurist, the application of the law is limited to legal texts and official regulations. Notions of justice, equity or morality that are not formalised in these texts have no legal weight in the decision-making process.

This approach emphasises a clear separation between law and morality, considering that the role of the legal system is not to interpret or apply abstract moral principles, but rather to apply the law as written. For positivists, the authority of the law derives from its formal adoption by recognised institutions, not from its conformity with external moral or natural principles. This perspective has significant implications for the practice of law. It limits the role of the judge to the interpretation and application of existing laws, without recourse to considerations external to positive law. Although this approach has its critics, notably those who argue that the law should be informed by moral or ethical considerations, it remains a cornerstone of legal thinking in many legal systems around the world.

An important development in the evolution of the law in recent decades is the incorporation of principles once considered to be natural law, such as liberty and equality, into positive law through constitutions and legislation. This phenomenon reflects a worldwide trend whereby universal values and principles are becoming codified and officially recognised in national legal systems. 150 years ago, concepts such as freedom and equality were often seen as moral or philosophical ideals rather than legally protected rights. However, over time, the growing recognition of the importance of these principles for a just and equitable society has led to their gradual incorporation into the framework of positive law. This has often happened through constitutional amendments or new legislation.

The inclusion of these principles in modern constitutions means that they have acquired binding legal force. For example, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights was an important milestone in this development, setting international human rights standards that were subsequently adopted in many national laws. Today, principles such as non-discrimination, the right to freedom of expression and the right to a fair trial are considered fundamental components of many legal systems. This development illustrates how societies and their legal systems adapt and change in response to evolving values and moral requirements. It also marks the diminishing of the traditional separation between natural law and positive law, with a growing recognition that moral and ethical principles can and should play a role in the formation of formal law.

It is important to understand and differentiate between positive law and natural law, two fundamental concepts in legal theory. Positive law refers to laws and regulations that are officially established and adopted by legislative and governmental authorities. These are norms that are formulated in concrete terms, enshrined in legal texts and applied by the judicial system. Positive law is specific to each society and may evolve over time, reflecting changes in society's values, needs and circumstances. Natural law, on the other hand, is based on principles that are considered universal and immutable, often linked to morality, ethics or notions of ideal justice. Natural law is not written down in specific legislative texts, but is rather seen as inherent in human nature or derived from human reason. Proponents of natural law argue that certain moral truths or principles should guide the creation and application of laws. It is crucial to understand the interaction between these two types of law. Historically, natural law has often been used as a basis for criticising or reforming positive law, particularly when existing laws are perceived to be unjust or outdated. Similarly, positive law, by drawing on the principles of natural law, can evolve to better reflect the ideals of justice and equality. In modern legal practice, there is often a dialogue between natural law and positive law, with universal principles influencing the drafting and interpretation of laws. Understanding this dynamic is essential for those who study law, work in the legal field, or are interested in how laws affect and are affected by notions of justice and ethics.

The rule of law[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The rule of law, or legal rule, is a fundamental element of the legal system, acting as a norm that guides and regulates the conduct of individuals in their social interactions. These rules are characterised by their generality, abstraction and binding nature, and are supported by the sanctioning power of the state. As general norms, they apply to a wide range of situations and are not limited to specific cases or particular individuals. Their abstraction means that they deal with general situations or patterns of behaviour, rather than specific details. The mandatory aspect of the rule of law is one of its most important attributes. Breach of these rules can result in sanctions, which are enforced by public authorities such as courts and law enforcement agencies. This means that the rules of law are not mere recommendations, but directives that must be complied with on pain of legal consequences.

As far as the law is concerned, it is a set of rules of law, often formulated and adopted by a legislative body, such as a parliament. The law is a formal expression of these rules and serves as a detailed guide to acceptable behaviour in society. It covers a variety of areas, from civil law, which governs relationships between individuals, to criminal law, which deals with crimes and penalties. Laws establish clear and precise standards that individuals and organisations must follow, and they play a crucial role in maintaining order and justice in society.

The importance of the rule of law and the law lies in their ability to structure and stabilise social, economic and political interactions. They ensure a degree of predictability and fairness in society, enabling individuals to understand the consequences of their actions and to plan accordingly. They also serve to protect the rights and freedoms of individuals, by setting limits on what is permissible and providing mechanisms for resolving conflicts. Ultimately, rules of law and legislation are essential for an organised and functional society, where justice and order are maintained.

The distinction between public and private law[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Mandatory, general and abstract[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The mandatory nature of legal rules is a fundamental element that is evident in any legal system. This characteristic means that the rules of law are not mere suggestions or advice, but imperative standards with which individuals and organisations are legally bound to comply. Failure to comply with these rules entails legal consequences, such as sanctions, penalties or other forms of legal redress. This binding nature is ensured by public authorities, in particular the judiciary and law enforcement agencies. The courts play a crucial role in interpreting laws and determining penalties for violations. The police are responsible for enforcing the law and maintaining public order. Legal obligation is a principle that distinguishes the law from other systems of norms, such as moral rules or social conventions. While the latter can influence behaviour, they do not have the same binding force as laws. For example, a moral rule may dictate ethical behaviour, but its violation does not generally result in legal sanctions. On the other hand, the violation of a law entails consequences that are legally defined and applied by the State. This obligation is essential to ensure order and stability in society. It ensures that individuals and institutions abide by an agreed set of rules, thereby facilitating cooperation, predictability and fairness in social relations. In short, the binding nature of legal rules is a pillar that underpins the structure and functioning of any organised and just society.

The general nature of legal rules is another essential feature that contributes to their effectiveness and fairness. This generality means that legal rules apply to an indefinite number of people and a multitude of situations, without any specific or personal distinction. Unlike decisions that are addressed to specific individuals or groups, legal rules are formulated to cover general categories of behaviour or situations. For example, a law prohibiting theft applies to all members of society, regardless of their personal status, profession or any other individual characteristic. This universality ensures that the rules of law are impartial and fair, applying in the same way to all those in similar circumstances. This generality is fundamental to ensuring equality before the law, a basic principle in many legal systems. It enables laws to serve as instruments of justice and public order, establishing clear and uniform standards for the conduct of individuals and institutions. It also contributes to the predictability and stability of the legal system, because individuals can understand and anticipate the legal consequences of their actions. The general nature of legal rules is a key element in ensuring the impartiality and effectiveness of the legal system, thereby helping to maintain order and justice in a society.

The abstract nature of legal rules is an essential feature that enables them to cover a wide range of situations. This abstraction means that legal rules are not formulated for specific circumstances or cases, but rather are designed to apply to any number of situations that might arise. This abstract quality is crucial because it gives rules of law the flexibility to be applicable in a variety of different contexts, without needing to be constantly modified or adapted. For example, a law that prohibits intentionally causing harm to others is sufficiently abstract to cover many types of harmful behaviour, without having to list every specific act that might constitute harm. Abstraction also allows the courts to interpret and apply the law consistently in a multitude of different situations. This helps to ensure that similar cases are treated in similar ways, contributing to the fairness and predictability of the legal system. In addition, it allows the law to adapt to developments and changes in society without the need to constantly rewrite laws. The abstract nature of legal rules is fundamental to their effectiveness and long-term relevance. It allows the legal system to encompass a wide range of behaviours and situations, while maintaining fairness and justice in its application.

Coercive nature: implies constraint[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

A fundamental aspect of legal rules is the presence of a sanction guaranteed by public authority. This feature distinguishes legal rules from other types of social norms, such as moral rules or conventions. Sanction in the legal context refers to a legal consequence or penalty imposed in response to the violation of a rule of law. Sanctions can take various forms, such as fines, prison sentences, reparation orders or other disciplinary measures. The role of sanctions is not only to punish offences, but also to deter future illegal behaviour and maintain social order. The public authority, or public power, plays a crucial role in ensuring and applying these sanctions. State bodies, such as the courts, the police and the various administrative agencies, function as the instruments by which the rules of law are applied and sanctions imposed. These bodies ensure compliance with the law, deal with offences and implement judicial decisions. The courts, in particular, play a central role in this process. They interpret the law, adjudicate on offences and determine the appropriate penalties. The police, for their part, are responsible for enforcing the law and maintaining public order, including the arrest and detention of offenders. The guarantee of a sanction by the public authority is a key element that gives the rules of law their strength and effectiveness. It ensures that the legal system is respected and followed, and that offences are dealt with appropriately, thereby contributing to stability and justice within society.

In most modern legal systems, including Switzerland, legal rules are distinct from religious rules. Contemporary legal systems are generally based on principles of positive law, which are established and applied independently of religious doctrines or prescriptions. However, it is true that certain rules or principles stemming from religious traditions have influenced or found their way into the positive law of many countries, including Switzerland. For example, the commandment "Thou shalt not kill", derived from many religious texts, is reflected in criminal laws that prohibit murder. This incorporation is not so much a question of religious authority over the law, but rather a coincidence whereby certain universally recognised moral standards, present in many religious traditions, coincide with the principles of justice and public order considered essential in secular law.

It is important to note that when such rules are incorporated into positive law, they do so not as religious doctrines, but as autonomous legal norms justified by secular considerations of public order, security and social welfare. Their validity and application do not depend on their religious origin, but on their formal incorporation into the legislative framework and their conformity with the general principles of law. Although modern legal systems and positive law operate independently of religious rules, there are cases where certain moral standards common to several religious traditions are incorporated into positive law. However, these norms are applied as secular laws, reflecting universal values rather than specific religious prescriptions.

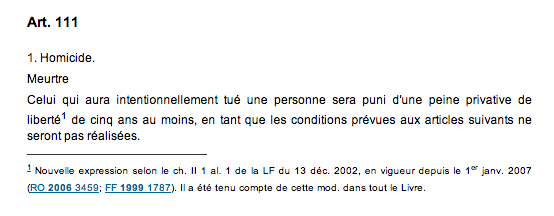

Article 111 of the Swiss Penal Code is a perfect example of how an ethical norm, often found in various religious and moral traditions, is incorporated into positive law in the form of secular law. Article 111 of the Swiss Penal Code clearly stipulates the legal consequences of murder, thus defining a clear legal prohibition on intentionally killing another person. This legal provision reflects a principle widely recognised in many cultures and societies, namely that murder is a serious transgression against the individual and society. However, in the context of positive law, this prohibition is formulated and applied independently of any religious considerations.

The Swiss Penal Code, like other legal systems, bases its laws on principles of justice, public order and the protection of individual rights. By establishing penalties for offences such as murder, it seeks to prevent criminal acts, protect citizens and maintain social order. The emphasis is on protecting human life and deterring behaviour that is dangerous to society. This example shows how positive law can incorporate principles that are also valued in religious and moral traditions, but does so within the framework of a secular legal system, with justifications and applications centred on the needs and values of civil society.

The elements of a rule of law[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Legal institutions are fundamental elements in the organisation of social relations in any society. They are made up of coherent sets of legal rules designed to structure specific aspects of human interaction. These institutions provide a legal framework that clearly defines the rights, obligations and procedures relating to these interactions, reflecting social values and needs.

Take the example of marriage, which is a central legal institution in many societies. As an institution, marriage is governed by laws that determine how two people can legally come together and what the legal consequences of this union are. These laws cover aspects such as the conditions under which a marriage is valid, the mutual responsibilities of the spouses, the management of joint property, and procedures in the event of separation or divorce. These regulations aim to ensure a balance between individual rights and collective interests, while protecting the parties involved, particularly in situations of breakdown or conflict.

Similarly, adoption is a legal institution that makes it possible to create legal ties of kinship between individuals who are not biologically related. The rules governing adoption are designed to ensure the welfare and protection of adopted children. They define the eligibility criteria for adopters, the procedures to be followed for adoption, and the legal effects of adoption on family relationships. The aim is to provide a stable and loving family environment for the child, while respecting his or her rights and those of his or her biological and adoptive parents.

These institutions, such as marriage and adoption, illustrate how the law can influence and shape fundamental social structures. By providing a detailed and structured legal framework, they contribute to social stability and respect for the rights and duties of individuals within society. Their evolution over time also reflects changes in social attitudes and norms, showing how the law adapts to meet society's changing needs.

The state of affairs[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The state of affairs refers to the concrete facts or circumstances that form the basis of a legal situation or dispute. It serves as the basis for the application of the law and for judicial decisions. In the application of a rule of law, the state of facts acts as a conditional proposition that determines when and how the rule should be applied. This means that the rule of law only applies if certain factual conditions, described in the state of facts, are met. For example, in a theft case, the statement of fact will detail the circumstances of the theft, such as where, when and how the act was committed. These details are essential to determine whether the facts meet the legal criteria defining theft and to decide on the appropriate application of the law.

In the context of a judgment, the statement of facts of a case comprises a complete and chronological statement of the relevant facts. It includes the identification of the parties involved, a description of the events leading up to the dispute, the key stages of the legal proceedings, and the claims or conclusions of each party. This factual exposition is crucial as it provides the framework within which the judge or court will assess the case, interpret the applicable law, and reach a decision. The accuracy and completeness of the statement of facts is therefore essential to ensure a fair and informed decision. The state of facts plays a fundamental role both in the application of the rules of law and in the judging process. It ensures that legal decisions are taken on the basis of a clear and detailed understanding of the specific facts of each case, thus guaranteeing the adequacy and fairness of the application of the law.

The example of "he who intentionally kills" is a good illustration of how a specific state of affairs can determine the application of a rule of law. In this case, the state of affairs concerns the intentional act of killing another person. In the legal context, this sentence would indicate the factual conditions necessary for the application of a criminal law relating to murder. For an individual to be tried under this law, it must be established that the act of killing was carried out intentionally. In other words, intent (or 'mens rea' in legal terms) is a crucial element of the state of facts that must be proved for a murder conviction to proceed.

In a murder trial, for example, the court will examine the evidence and circumstances surrounding the case to determine whether the accused acted with intent to kill. This includes examining the accused's actions, his state of mind at the time, and any other relevant factors that may shed light on his intentions. If the intention to kill is proven, then the state of affairs corresponds to the rule of law applicable to murder, and the court can proceed to apply the appropriate sanction. This example illustrates how the state of facts serves as the basis for the application of legal rules, underlining the importance of detailed factual analysis in the judicial decision-making process.

The operative part[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The operative part is an essential component of a court judgment or decision, setting out the legal conclusion of the case. It clearly states the legal effect of the court's decision, indicating the specific actions that the parties must take or avoid as a result of the judgment. This part of the judgment is crucial because it determines the practical implications and legal consequences for the parties involved. In a dispositif, the court may pronounce different forms of legal effect. It may issue a prohibition, preventing a party from carrying out certain actions. For example, in a case of copyright infringement, the writ may prohibit the defendant from continuing to use the protected content. In addition, the device may impose an obligation to do, requiring a party to perform a specific action. This is common in contractual disputes where the court orders a party to perform its contractual obligations. Alternatively, the device may impose an obligation not to do certain things, such as stopping an activity that causes a nuisance to others. The role of the arrangement is not limited to simply stating these obligations or prohibitions. It has binding legal authority, meaning that the parties are legally obliged to comply with its terms. In the event of non-compliance, sanctions may be applied or enforcement measures taken to ensure compliance. In this way, the mechanism plays a decisive role in the effective implementation of justice, translating the court's legal conclusions into concrete, enforceable actions.

The example of who "shall be deprived of a custodial sentence of not less than 5 years", illustrates a type of device that might be found in a court decision, specifying the penalty imposed on a person found guilty of an offence. However, there seems to be a slight error in the wording. Normally, in the legal context, a disposition would state that the person is "sentenced to a custodial sentence of at least 5 years". In this case, the provision clearly indicates that the penalty for the offence committed is a prison sentence of at least five years. This means that, following sentencing, the convicted individual will be required by law to serve a prison sentence for the specified period. This type of device is typical in criminal cases where the court determines the appropriate sentence based on the seriousness of the offence and other relevant factors relating to the case. This device translates the court's decision into concrete action, indicating how the law should be applied in that particular case. The sentencing specification reflects the application of the rule of law to the established state of facts, demonstrating how justice is dispensed in individual cases in accordance with established norms and laws.

The dispositif is also the part of a judgment that contains the court's actual decision. This is the section where the court explicitly rules on the claims or submissions of the parties involved in the case. In the operative part, the court summarises its decisions on the main issues in dispute. For example, in a civil case, this may include decisions on claims for damages, the performance of a contract, or liability in an accident. In a criminal case, the operative part will contain the court's decision as to the guilt or innocence of the accused and set out the penalties or sanctions, if any. This part of the judgment is crucial because it determines the outcome of the case and the legal consequences for the parties. It must be clear and precise, because it is on the basis of the operative part that enforcement or appeal actions are taken. It is also this part of the judgment that is legally binding and can be enforced by the force of law. The operative part, as the formal legal conclusion of the case, represents the concrete application of the rules of law to the facts established during the trial. It reflects the way in which the court has interpreted the law and taken into account the evidence and arguments presented by the parties. In short, the operative part is the heart of the judicial decision, translating the court's deliberations and legal reasoning into a final and enforceable conclusion.

Dispositive, suppletive or declarative rules[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Dispositive rules (also known as suppletive or declaratory rules) capture an important aspect of civil law. These rules are those that apply in the absence of stipulations to the contrary by the parties concerned in their agreements or contracts.

Dispositive rules function as a frame of reference or default standard. They come into play when the parties to an agreement have not expressed a contrary will or drafted their own clauses to specifically govern their relationship or situation. In other words, these rules offer a standard legal solution that applies automatically, unless the parties have agreed a different arrangement. A classic example of a dispositive rule is the rules governing the distribution of property in the event of the dissolution of a company or marriage without a pre-established contract. If the parties have not drawn up a specific agreement on how to divide the assets, the dispositive rules laid down by law will apply.

These rules are essential because they provide legal certainty and predictability in situations where the parties have not drawn up specific agreements. They also allow a degree of flexibility in the regulation of private affairs, giving parties the freedom to determine their own arrangements while providing a legal safety net in the absence of agreement. Dispositive rules act as a filler, filling in gaps where the parties have not expressed any particular will. In this way, they enable transactions and legal relationships to function smoothly, while providing a basic framework for situations not regulated by private agreements.

Peremptory rules[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Peremptory rules are legal norms that apply absolutely and unconditionally to all persons falling within their scope. They are designed to be incontestable and cannot be modified by individual agreements or wishes. Unlike dispositive rules, which allow parties to agree their own terms as long as they do not run counter to the rules, mandatory rules leave no room for such private negotiations or arrangements. They are established to protect interests deemed fundamental by society, such as public order, morality, safety and fundamental rights.

For example, in the field of labour law, there are mandatory rules concerning minimum wages, maximum working hours and safety conditions in the workplace. These rules are designed to protect workers against exploitation and dangerous working conditions, and cannot be changed by agreement between employer and employee. Similarly, in family law, certain rules relating to filiation, adoption and marriage are mandatory. They guarantee respect for fundamental rights and the protection of the most vulnerable parties, such as children. Imperative rules are therefore essential to ensure fairness, justice and the protection of vital interests in society. They represent the fundamental values and principles on which the legal order is based and serve as an essential guide in the application and interpretation of laws.