« The State: Functions, Structures and Political Regimes » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 91 : | Ligne 91 : | ||

= The political systems = | = The political systems = | ||

A state's form of government is embodied and put into practice by its organs, or public authorities, which are the institutions through which decision-making, policy-making and the execution of government actions take place. These public authorities are generally structured into three interdependent but distinct branches: legislative, executive and judicial, each of which plays a crucial role in the governance of the State. | |||

The legislative branch, often represented by a parliament or assembly, is the mainstay of lawmaking. Made up of elected representatives, it reflects the will of the people and is at the heart of democratic debate. For example, Congress in the United States and Parliament in the United Kingdom are the bodies where laws are debated, amended and passed, defining the norms that govern society. These legislative institutions are essential for shaping public policy and establishing the rules that influence all aspects of national life. | |||

The executive branch, headed by figures such as the president or prime minister, is responsible for the day-to-day management of the state and the enforcement of laws. This power includes various ministries and agencies responsible for specific sectors such as defence, foreign affairs or the economy. In France, for example, the president and the government, comprising various ministers, are at the centre of state administration, implementing laws and managing international relations, national security and economic policies. | |||

As for the judiciary, it plays the crucial role of arbiter in the interpretation of laws and ensures that justice is dispensed fairly. The courts and tribunals that make up this branch are responsible for resolving disputes, judging the conformity of actions with the constitution and ensuring that laws are applied fairly. In countries such as Germany and Canada, the judicial systems operate independently of the other branches of government, ensuring that legal decisions are taken without political influence and in strict accordance with the law. | |||

The structure and interaction of these three powers determine the form of government and are essential to maintain balance, avoid abuse of power and ensure democratic and accountable governance. The separation and balance of powers ensures that the different branches of government effectively represent and serve the interests of the population, while respecting the rule of law and democratic principles. This balance is vital for political stability and the legitimacy of government in the eyes of the people. | |||

== | == The monarchy == | ||

Monarchy is a political system characterised by the presence of a monarch, such as a king or queen, as head of state. In this system, the monarch's position is often hereditary, passing from generation to generation within the same royal family. The specifics of the monarch's role and power can vary considerably from one monarchy to another, depending on the constitutional and historical structure of each country. | |||

In the case of absolute monarchy, the monarch holds total, exclusive and unlimited power over the state. This type of monarchy was more widespread throughout history, particularly in Europe during certain periods. In an absolute monarchy, the monarch is not bound by written laws or a constitution, and exercises total control over the government and administration of the country. The monarch's decisions are final and he often has legislative, executive and judicial power. A famous historical example of absolute monarchy is that of France under the reign of Louis XIV, where the king had unchallenged power, epitomised by his famous phrase "L'État, c'est moi" ("I am the State"). In such monarchies, the monarch was often considered to rule by divine right, i.e. chosen by and representing God's will on earth, which further strengthened his absolute power. Today, most existing monarchies are constitutional, meaning that the monarch's power is limited by a constitution and often exercised within a democratic framework, with an elected government managing the affairs of state. In these systems, the role of the monarch is usually ceremonial, with little real power over political or governmental decisions. Examples of such constitutional monarchies include the United Kingdom, Sweden and Japan. | |||

The adage "Si veut le Roy, si veut la loi" expressed by the French jurist Pierre Loisel (1536 - 1617) captures the essence of absolute monarchy, where the king's will is imposed as law. This principle reflects the conception of monarchical power at the time, when the monarch was not only the head of state, but also the supreme source of legislation. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is considered the ultimate authority, with his or her decisions and wishes having the force of law. This means that the monarch is not required to follow pre-established laws or consult other governing bodies before taking decisions. The law is therefore the direct product of the monarch's will and applies to all subjects without exception. This system concentrates all powers - legislative, executive and judicial - in the hands of the monarch. This approach to governance was typical of several European monarchies in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was part of an era when the notion of the divine right of kings was widely accepted, legitimising the monarch's absolute power as being granted and sanctioned by divine authority. The example of Neuchâtel as an ecclesiastical monarchy under the Prince-Bishop of Basel also illustrates this form of governance. In such monarchies, religious and civil authority were often merged, reinforcing the idea that royal or princely power was both temporal and spiritual. Today, these notions of absolute monarchy have largely evolved towards more democratic and constitutional forms of governance, where the power of the monarch is limited and balanced by other state institutions and by respect for constitutional laws. | |||

== | == The oligarchy == | ||

Oligarchy is a political system in which power is held and exercised by a small group of people. This form of government differs from monarchy, where power is concentrated in the hands of a single individual, usually a king or queen. In an oligarchy, power is shared between a few individuals who can be distinguished by their wealth, social status, education, corporate affiliation or membership of a certain elite. Unlike a democracy, where power is supposed to reside in the population as a whole, oligarchy involves a concentration of power within a small segment of society. This ruling minority can exert its influence in different ways, often by controlling the main economic, political or military levers. The decisions and policies adopted by an oligarchic government generally reflect the interests and visions of this small group, rather than those of the majority of the population. | |||

Oligarchy can sometimes be disguised as a democracy, with formal elections and institutions. In practice, however, the real power lies in the hands of a few influential individuals or families. These groups can maintain their influence through various means, such as control of the media, large corporations, political funding, or networks of relationships and patronage. Historically, many political systems have had oligarchic characteristics. For example, in some ancient Greek city-states, power was often held by a small elite of wealthy and influential citizens. Similarly, at different periods in history, many societies have seen their government dominated by an aristocratic class or an economic elite. Oligarchy is often criticised for its lack of representativeness and fairness, as it excludes the majority of citizens from effective participation in the political process and tends to favour the interests of a small section of society to the detriment of the common good. | |||

== | == Democracy == | ||

Democracy is a political system based on the principle of popular sovereignty, where power belongs to the people. In a democracy, citizens play a central role in decision-making and the exercise of power, either directly or through elected representatives. In a direct democracy, citizens actively participate in the formulation and adoption of laws and policies. This direct exercise of power often takes the form of referendums or popular assemblies where citizens vote on specific issues. A historical example of direct democracy is the ancient Athenian city-state, where citizens met to debate and decide on the affairs of state. In most modern democracies, however, the system is representative: citizens elect representatives to govern them and make decisions on their behalf. This form of democracy allows for more practical management of a state's affairs, especially when the population is too large for everyone to participate directly in governance. Elected representatives, such as members of parliament, senators and the head of state, are supposed to reflect the will of the people and act in the general interest. | |||

Representative democracy is usually accompanied by various institutions and mechanisms to ensure transparency, accountability and fairness in the political process. These include regular, free and fair elections, civil rights such as freedom of expression and association, a free press, and independent judicial systems to protect citizens' rights. Countries such as the United States, Germany, Canada and Australia are examples of representative democracies. In these systems, although citizens do not directly make political decisions, they play a crucial role by electing those who govern them and by participating in public debate, which shapes the state's policies and laws. | |||

The quote from Heinrich Rudolf Schinz, an eminent 19th century Zurich jurist, underlines a fundamental understanding of democracy and the role of government, particularly in the Swiss context. His assertion that "all governments in Switzerland must recognise this, that they exist only insofar as they are of the people and act by the people and for the people" reflects the idea that the legitimacy of a government rests on its representation of and service to the people. This perspective is particularly relevant to Switzerland, a country that has long valued the principles of direct and participatory democracy. In 1830, when Schinz expressed this view, Switzerland was in the midst of a period of political transformation and development. His ideas resonated with the emerging democratic ideals of responsible government that was responsive to the needs and wishes of its citizens. | |||

Schinz's emphasis on governments being "of the people" means that authorities must emanate from the consent and will of citizens. This implies a transparent and fair democratic process in which citizens have a meaningful role in electing their representatives and in political decision-making. The expression "governed by the people" underlines the importance of citizen participation in governance. In the Swiss system, this translates into mechanisms of direct democracy, such as referendums and popular initiatives, where citizens can directly influence legislation and public policy. As for "acting for the people", this refers to the obligation of governments to work in the general interest, implementing policies and laws that benefit society as a whole, rather than serving particular interests or elites. Schinz's vision is emblematic of the democratic principles that continue to be at the heart of governance in Switzerland, where power is exercised transparently and accountably, with the active participation of citizens. This reflects a commitment to a democracy that is not just a form of government, but also an expression of the values and aspirations of the people. | |||

Abraham Lincoln's quote at the dedication of the cemetery at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 is one of the most famous speeches in American history and a pillar of democratic thought. His words, "May we, by our determination, see that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under the shadow of God, may be reborn in liberty... and that government of the people, by the people and for the people shall not perish from the face of the earth", resonate deeply with the values of democracy and freedom. Lincoln delivered this speech against the backdrop of a wrenching civil war, where the nation was deeply divided over issues of freedom and slavery. The Battle of Gettysburg, one of the bloodiest of the American Civil War, was a crucial moment in the conflict. By evoking the sacrifices of fallen soldiers, Lincoln sought to give meaning to those losses and to reinforce the nation's commitment to the principles of liberty and unity. | |||

The idea that "government of the people, by the people, and for the people" must not "perish from the face of the earth" is a powerful affirmation of democratic principles. Lincoln emphasised that democracy was not only essential for the United States, but also an ideal to be preserved for all mankind. This concept implies that government should be based on the will of the people, that it should be exercised by representatives elected to serve the interests of the people, and that its ultimate goal must be the well-being of the people. The Gettysburg Address, though brief, had a profound and lasting impact, not only on American society, but also on the global perception of democracy and freedom. It continues to be cited as an eloquent example of leadership in times of crisis and a powerful reminder of the fundamental values on which democracies are built. | |||

= Annexes = | = Annexes = | ||

= | = References = | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:droit]] | [[Category:droit]] | ||

[[Category:Victor Monnier]] | [[Category:Victor Monnier]] | ||

Version du 8 décembre 2023 à 15:59

Based on a course by Victor Monnier[1][2][3]

Introduction to the Law : Key Concepts and Definitions ● The State: Functions, Structures and Political Regimes ● The different branches of law ● The sources of law ● The great formative traditions of law ● The elements of the legal relationship ● The application of law ● The implementation of a law ● The evolution of Switzerland from its origins to the 20th century ● Switzerland's domestic legal framework ● Switzerland's state structure, political system and neutrality ● The evolution of international relations from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century ● The universal organizations ● European organisations and their relations with Switzerland ● Categories and generations of fundamental rights ● The origins of fundamental rights ● Declarations of rights at the end of the 18th century ● Towards the construction of a universal conception of fundamental rights in the 20th century

The state, as a central concept in the study of political science and history, is a subject of considerable complexity and importance. Our exploration of this theme seeks to unravel and understand the multiple facets that make up this essential political entity. By immersing ourselves in an in-depth analysis of the state, we aim to unveil its constituent elements, such as population, territory and sovereignty, and to understand how these components fit together and interact to form the backbone of what we call a state. In our quest to define the concept of the state, we will also examine the various functions it performs, from the creation of law to its enforcement, including the administration of justice. In so doing, we will seek to grasp the various ways in which the state influences and structures society.

This approach will also lead us to compare different state structures, ranging from unitary states to confederations and federal states. By assessing these various models, we will seek to understand their specific features, their advantages and disadvantages, and the contexts in which each can be most effective. Finally, our study will be enriched by looking at the historical perspective and reflections of emblematic figures who have influenced the understanding and evolution of the concept of the state. Through this exploration, we aim to gain a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the state, an entity that is both omnipresent and enigmatic in our lives and our history.

What is the State?

The State is a complex and fundamental entity in the political and social organisation of the modern world. Its definition is based on three key elements that are intertwined and mutually reinforcing.

Firstly, the population constitutes the human aspect of the State. It is made up of all the individuals living in a given territory and subject to the same political authority. These individuals often share a national identity and cultural values and are bound by a common set of laws and regulations. For example, the French population is distinguished by its culture, language and traditions, while being united under the laws and principles of the French Republic.

Secondly, the territory is the geographical space over which the State exercises its authority. It includes not only dry land, but also territorial waters, airspace and, in some cases, maritime zones. Controlling and delimiting this territory is crucial. Take China, for example, which controls a vast territory ranging from densely populated coastal regions to isolated mountain and desert areas, with each region integrated into the country's political and administrative structure.

Finally, sovereignty is the principle that gives the State its supreme authority and independence. This means that the state holds ultimate power over its population and territory, without outside interference. Sovereignty manifests itself in the state's ability to create and apply laws, to conduct an independent foreign policy and to defend itself. A striking example is the United States, which exercises its sovereignty through a powerful federal government, autonomous legislation and considerable influence on the international stage.

These three components - population, territory and sovereignty - form the foundation on which the state's existence rests. They define its identity, structure and functioning, and distinguish it from other forms of organisation or institution. The combination of these elements ensures not only the internal stability of the state, but also its recognition and interaction on the international stage.

The functions of the State

The legislative function is an essential pillar in the functioning of a democratic state, its main role being to create rules and pass laws. This function is generally entrusted to a legislative body, such as a parliament or assembly, made up of representatives elected by the population. The process of creating laws is a complex and methodical one. It often begins with the identification of a need or problem within society. For example, an increase in cybercrime could lead to the proposal of new laws on computer security. Members of the legislature, sometimes in collaboration with the executive, then prepare a bill, which is debated, amended and finally passed. Once passed, the law becomes a legal standard that all members of society must respect. Laws can cover a wide range of areas, from civil and commercial law to criminal law, environmental regulations and social protection. They are essential for maintaining order, protecting citizens' rights and guiding interactions within society. The legislative function also plays a crucial role in defining public policy. For example, the adoption of laws favouring renewable energies can guide a country towards an ecological transition. Similarly, laws on education or public health determine the way in which these essential services are organised and financed. The legislative function is therefore a driving force for change and evolution in a society. It enables the legal framework to be adapted to changing realities, ensuring that laws remain relevant, fair and effective in meeting the needs of the population.

The executive function is another fundamental pillar in the governance structure of a state. Its main task is to manage the State's day-to-day policy and to apply or enforce the laws drawn up by the legislature and the decisions handed down by the judiciary. This function is generally performed by the government, headed by a head of state (such as a president) or a head of government (such as a prime minister), and comprises various ministries and departments that focus on specific areas such as education, health, defence or the economy. The executive is responsible for implementing the policies and laws passed by the legislature, ensuring that they are applied effectively and in accordance with the legislative intentions. For example, if the legislature passes a new tax law, it is up to the executive to ensure that it is properly applied, by putting in place the necessary structures, informing the public, and ensuring that taxes are collected in accordance with the law. Similarly, the executive plays a crucial role in managing the day-to-day affairs of the state, such as conducting foreign policy, managing crises or implementing economic development plans. The executive is also responsible for ensuring that the legal system is respected, in particular by working with the judiciary. It ensures that legal decisions are applied and that citizens' rights are protected. For example, in the event of a court conviction, it is up to the executive authorities, such as the police and prison services, to carry out the sentence. In this way, the executive acts as a crucial link between laws and the daily lives of citizens, ensuring that decisions taken at legislative level are translated into concrete action and effective public policies. Its role is essential to the stability and proper functioning of the State, and to the implementation of the laws and policies that shape society.

The judicial function, often referred to as the judiciary, plays a vital role in the governance of a state. Its primary mission is to dispense justice and determine the applicable law in the various disputes that come before it. This function is essential for maintaining order and fairness in society, and for ensuring respect for the law and the rights of individuals. Judicial power is embodied in the courts and tribunals, which are responsible for trying cases and resolving disputes. This process involves interpreting the laws laid down by the legislature and applying them to specific cases. Judges and magistrates, as the main players in this function, assess the evidence, hear the arguments of the parties in dispute, and hand down decisions based on the legal framework in place. A crucial aspect of the judicial function is its independence from the other powers of the State. This independence ensures that judgements are handed down impartially and fairly, without outside influence or political pressure. For example, in a commercial dispute, a court must judge solely on the basis of the relevant laws and the facts presented, without regard to political or personal interests. The jurisdictional function also extends beyond the resolution of disputes between private parties. It includes the adjudication of criminal offences, where the state, through the public prosecutor, prosecutes individuals or entities accused of breaking the law. In such cases, the judiciary is responsible for determining the guilt or innocence of the accused and imposing appropriate penalties, in accordance with the laws in force. The judicial function is crucial to the maintenance of law and order and the protection of individual rights and freedoms. It ensures that laws are not just words on paper, but living principles that actually govern life in society. Through its role as impartial arbiter, the judiciary helps to establish a climate of trust and respect for the rules that is fundamental to any democratic and equitable society.

The structures of states

The unitary state

The unitary state is a form of state organisation in which political authority is centralised. In such a system, there is no intermediate political power between the citizens and the central state. Administrative subdivisions, such as départements, regions or communes, exist primarily to facilitate the management and administration of the territory, but they have no significant political autonomy. They are subject to the directives and authority of the central state.

In a unitary state, there is a single centre of political impetus. This means that major decisions concerning legislation, policy and administration are taken by the central government. This central government has the legislative power to create rules of law that are uniform throughout the country. This ensures consistency and uniformity in the implementation of laws and policies throughout the country. The existence of a single Constitution in a unitary state also underlines this centralisation. The Constitution establishes the fundamental principles of government, the rights of citizens and the limits of state power. In a unitary state, this Constitution applies uniformly throughout the territory, without there being separate constitutions or charters for regions or local authorities. The main advantage of the unitary state is its simplicity and efficiency. The centralisation of power means that decisions are taken more quickly, policies are more coherent and the administration is more uniform. However, it can also lead to a certain distance between central government and local needs, and an excessive concentration of power. Examples of unitary states include France and Japan. In these countries, although local governments exist, their powers and responsibilities are largely defined and limited by the central government. This structure reflects the ideal of uniformity and centralisation of authority within the state.

The confederation of states

A confederation of states is a model of organisation in which several sovereign states decide to join forces to achieve specific objectives. Unlike other forms of political integration, this union maintains the sovereignty and independence of each member state. The aims pursued by a confederation are generally limited and focus on common interests such as defence, foreign policy or trade.

The creation of a confederation is based on an international treaty, which is a formal agreement between the participating states. This treaty defines the terms of cooperation, the areas of competence of the joint body and the decision-making procedures. Unlike a federal state, where the central government has direct authority over its citizens, in a confederation the central government acts through the governments of the member states. The joint body set up by the confederation may be responsible for various functions, such as coordinating foreign policy, managing common defence or implementing cross-border economic regulations. However, the scope of its powers is strictly limited to the areas specified in the treaty. Decisions taken by this body must often be approved by the Member States, reflecting the principle of sovereignty and equality between them.

Confederation is therefore characterised by intergovernmental cooperation rather than supranational integration. This means that, although the Member States work together to achieve common goals, they retain full autonomy in most areas. Historically, the Swiss Confederation and the United States of America under the Articles of Confederation (prior to the adoption of the current Constitution) are examples of confederations. These entities reflect the desire of states to work together for mutual benefit while preserving their independence and national identity.

The motivations behind the formation of a confederation of states are varied, but generally revolve around the pursuit of common benefits while preserving the autonomy of each member state. Among the main reasons why these states choose to unite is often the desire to ensure peace and security within the alliance, as well as the desire to protect themselves against external threats. Peace within the alliance is a crucial objective. By coming together, the Member States seek to prevent internal conflicts from arising between them. This internal peace is fostered by cooperation and mutual agreements, which enable disputes and rivalries to be managed peacefully. This can be particularly important in regions where history or geopolitics have created tensions between neighbours. Protection against external threats is also a major reason for forming a confederation. By joining forces, states can increase their capacity to defend themselves against foreign aggression or influence. This can take the form of mutual defence agreements, the implementation of a collective security strategy, or even the sharing of resources to strengthen regional stability.

To facilitate cooperation and decision-making, confederations generally organise conferences or meetings where representatives of the various member states meet. These conferences are crucial forums for discussion, negotiation and joint planning. Representatives can debate policies, propose joint initiatives and resolve shared issues. The format and frequency of these meetings depend on the provisions of the treaty that established the confederation and the nature of the issues discussed. These meetings are essential to maintaining the cohesion and effectiveness of the confederation, as they enable the Member States to coordinate their policies and actions while respecting their individual sovereignty. In this way, confederation represents a delicate balance between the independence of individual states and the need to work together to achieve common goals.

The Federal State

A federal state is a form of state organisation characterised by a combination of centralisation and decentralisation of power. In a federal state, several political communities, often called states, provinces or regions, are grouped together within a larger entity. Each of these communities has its own autonomy, with its own governments and legislation, but they are integrated into a higher national structure, the federal state.

A key feature of the federal state is the division of powers between the central government and the governments of the federated entities. This division is generally defined by a Constitution that sets out the powers and responsibilities of each level of government. The federated entities have the power to legislate and govern in certain areas, such as education, health and local transport, while the federal state has powers in areas such as defence, foreign policy and finance. In practice, only the federal state is recognised as a sovereign state on the international stage. It represents the federation as a whole in external relations, conducting foreign policy, concluding treaties and joining international organisations. This does not mean that the federated entities have no role in international affairs, but their actions in this area are generally coordinated or supervised by the federal state.

The federal state therefore combines the advantages of local governance, thanks to the autonomy of the federated entities, with those of unified and coherent governance at a higher level. This structure makes it possible to accommodate regional, ethnic or cultural diversity within the same state, while maintaining national unity and coordination. Examples of federal states include the United States, Germany, Canada and Australia. In each of these countries, the coexistence of a central government and autonomous regional or local governments reflects the complex, multi-layered nature of their governance.

The evolution from a confederation of states to a federal state is a historical process that has occurred in several cases, motivated by recognition of the advantages of a more integrated federal structure. This transition often reflects a desire to strengthen the union between member states while maintaining a degree of regional autonomy. In a confederation, member states retain a large degree of sovereignty and independence. Although this structure encourages cooperation on specific issues, it can lack cohesion and effectiveness, particularly in the areas of foreign policy, defence and economic management. Member states of a confederation may realise that they would be stronger and more cohesive under a federal structure, where a central government holds more substantial authority, while respecting the autonomy of the federated entities.

The move to a federal state allows member states to benefit from a centralised government for matters that concern the federation as a whole, while retaining their own government, legislative and judicial powers to manage local or regional affairs. This two-sided structure offers a balance between unity and diversity, enabling national and international affairs to be managed more effectively, while respecting regional particularities. In addition, the formation of a federal state can strengthen cohesion and stability between Member States. By sharing a common constitution, an integrated economic market and a unified foreign policy, the Member States create a sense of unity and solidarity. This federal structure can also lead to a better distribution of resources, coordination of economic and social policies, and a collective response to external challenges. The most emblematic example of this transition is the United States of America, which moved from a confederation under the Articles of Confederation to a federal state with the adoption of the Constitution in 1787. This change was motivated by the need for a stronger central government to effectively manage the country's affairs, particularly in the areas of finance, trade and international relations.

In a political system where the cantonal and federal levels of government exist side by side, there is a complex and nuanced structure of governance, typical of certain federal states such as Switzerland. This organisation allows for management at two levels, combining the advantages of national coordination with those of regional autonomy. At federal level, the central government is responsible for matters that affect the nation as a whole. This level of governance deals with areas such as foreign policy, national defence, international trade and important economic and legislative matters. The federal government has the power to legislate on matters that apply to the whole country, ensuring a degree of uniformity in national policies. It also plays a crucial role in representing the state on the international stage, making decisions that affect the country as a whole. In parallel, at cantonal level, regional or local bodies, with their own government and legislature, manage affairs more specific to their region. The cantons enjoy a degree of autonomy, allowing them to concentrate on areas such as education, local policing, public health and certain aspects of civil law. The national constitution or federal agreements define the powers of these cantonal governments, which can draw up laws and policies tailored to the needs and particularities of their population. This autonomy allows for regional diversity in the management of public affairs.

This coexistence of cantonal and federal states creates a flexible and adaptable system of governance. It enables the cantons to respond in a more targeted way to the demands and preferences of their citizens, while ensuring coherence and unity at national level. This model promotes participatory democracy, where citizens are involved in decision-making at different levels, thereby strengthening the legitimacy and effectiveness of the political system. This two-sided structure, combining cantonal autonomy and federal governance, offers a valuable balance between local diversity and national cohesion. It is emblematic of the way in which federal states can accommodate both the specific needs of the regions and the overall interests of the nation, creating a governance framework that is both robust and dynamic.

In a federal state, the three traditional functions of the state - legislative, executive and judicial - are exercised both at federal level and at the level of lower entities, such as cantons or member states. This structure creates a unique dynamic in which two centres of legal impetus coexist: federal law and cantonal or state law. At federal level, the central government exercises the legislative function by passing laws that apply to the whole nation. These laws typically concern areas of national interest, such as defence, foreign policy or major economic issues. Similarly, the federal executive manages the day-to-day business of the state at a national level, and the federal judiciary is responsible for interpreting and applying federal laws.

At the same time, the federated entities, such as the cantons in the case of Switzerland, also have the capacity to enact legislation in the areas under their jurisdiction. These cantonal laws may relate to matters specific to the region, such as local education, public health, and certain economic and social regulations. The cantonal governments also exercise executive and judicial functions within their jurisdiction, applying and interpreting cantonal laws. This duality of legislative powers between federal and cantonal law is one of the distinguishing features of federal states. It allows a degree of flexibility and adaptation to regional particularities while maintaining uniformity and cohesion at national level. Lower entities, while linked to the federal framework, retain significant autonomy to meet the specific needs of their population. Consequently, in a federal state, citizens live under the dual authority of federal and cantonal law. This coexistence of levels of governance promotes a balance between national unity and regional diversity, contributing to the stability and effectiveness of the political system as a whole.

The Confederation and the European Union (EU) are two forms of international organisation, but they differ considerably in their structure and operation. In a confederation, the main body is generally made up of representatives of the sovereign member states. These representatives act and take decisions in the interests of their respective states. The confederation, as such, is often a loose union in which the member states retain a large part of their sovereignty and independence. Decisions taken within the confederation usually require unanimity or a broad consensus of the Member States. The emphasis is on cooperation between sovereign states rather than the creation of a supranational entity with direct power over citizens. In contrast, the European Union represents a more integrated form of regional organisation. Although the Member States retain significant sovereignty, the EU has the characteristics of a supranational entity. The European Parliament, elected directly by the citizens of the Member States, represents the European people and plays a crucial role in the EU's legislative process. This direct democratic approach distinguishes the EU from a classic confederation. In addition, the EU has supranational institutions, such as the European Commission, the European Council and the Court of Justice of the European Union, which have executive, legislative and judicial powers that extend beyond national borders.

The EU is therefore more than just cooperation between states; it is a political and economic union with common policies in many areas, such as trade, the environment and the mobility of citizens. EU Member States share common legislation in certain areas and are bound by a set of treaties that define the rules by which the EU operates. The fundamental difference between a confederation and the European Union lies in the degree of integration and the nature of the representative institutions. Whereas a confederation is based on cooperation between sovereign states with limited power at central level, the EU represents deeper integration with supranational institutions having direct authority over certain aspects of the lives of European citizens.

The European Union (EU) is indeed a unique entity in the global political and institutional landscape, often described as a 'sui generis' organisation - a category in itself that does not fit into the traditional classifications of federal state or confederation. This singularity can be explained by the coexistence of the characteristics of these two forms of organisation, while at the same time presenting distinctive features of its own. On the one hand, the EU has elements of a confederation. The Member States retain a large degree of sovereignty, particularly in areas such as foreign policy and defence. Important decisions, particularly in the area of common foreign and security policy, often require unanimity among the Member States. This structure reflects the intergovernmental cooperation typical of a confederation, where states act together on the basis of their common interests while preserving their national independence. On the other hand, the EU has characteristics similar to those of a federal state. It has supranational institutions, such as the European Parliament, the European Commission and the Court of Justice of the European Union, which have powers that transcend national borders. The European Parliament, elected directly by the citizens of the Member States, is an example of democratic representation at supranational level. The EU also has common policies and legislation in areas such as the internal market, the environment and economic regulation, which are applied uniformly across the Member States. However, the EU differs from a classical federal state in that it has no sovereignty of its own; its sovereignty is derived from the Member States. Furthermore, although the EU has common legislation in some areas, the Member States retain a great deal of autonomy in other key areas, such as taxation and social affairs. The EU is a unique example of regional cooperation, combining aspects of a confederation and a federal state, while at the same time having its own distinctive features. This hybrid nature makes the EU a complex and constantly evolving entity, reflecting the diversity and growing interdependence of European states in a globalised world.

The political systems

A state's form of government is embodied and put into practice by its organs, or public authorities, which are the institutions through which decision-making, policy-making and the execution of government actions take place. These public authorities are generally structured into three interdependent but distinct branches: legislative, executive and judicial, each of which plays a crucial role in the governance of the State.

The legislative branch, often represented by a parliament or assembly, is the mainstay of lawmaking. Made up of elected representatives, it reflects the will of the people and is at the heart of democratic debate. For example, Congress in the United States and Parliament in the United Kingdom are the bodies where laws are debated, amended and passed, defining the norms that govern society. These legislative institutions are essential for shaping public policy and establishing the rules that influence all aspects of national life.

The executive branch, headed by figures such as the president or prime minister, is responsible for the day-to-day management of the state and the enforcement of laws. This power includes various ministries and agencies responsible for specific sectors such as defence, foreign affairs or the economy. In France, for example, the president and the government, comprising various ministers, are at the centre of state administration, implementing laws and managing international relations, national security and economic policies.

As for the judiciary, it plays the crucial role of arbiter in the interpretation of laws and ensures that justice is dispensed fairly. The courts and tribunals that make up this branch are responsible for resolving disputes, judging the conformity of actions with the constitution and ensuring that laws are applied fairly. In countries such as Germany and Canada, the judicial systems operate independently of the other branches of government, ensuring that legal decisions are taken without political influence and in strict accordance with the law.

The structure and interaction of these three powers determine the form of government and are essential to maintain balance, avoid abuse of power and ensure democratic and accountable governance. The separation and balance of powers ensures that the different branches of government effectively represent and serve the interests of the population, while respecting the rule of law and democratic principles. This balance is vital for political stability and the legitimacy of government in the eyes of the people.

The monarchy

Monarchy is a political system characterised by the presence of a monarch, such as a king or queen, as head of state. In this system, the monarch's position is often hereditary, passing from generation to generation within the same royal family. The specifics of the monarch's role and power can vary considerably from one monarchy to another, depending on the constitutional and historical structure of each country.

In the case of absolute monarchy, the monarch holds total, exclusive and unlimited power over the state. This type of monarchy was more widespread throughout history, particularly in Europe during certain periods. In an absolute monarchy, the monarch is not bound by written laws or a constitution, and exercises total control over the government and administration of the country. The monarch's decisions are final and he often has legislative, executive and judicial power. A famous historical example of absolute monarchy is that of France under the reign of Louis XIV, where the king had unchallenged power, epitomised by his famous phrase "L'État, c'est moi" ("I am the State"). In such monarchies, the monarch was often considered to rule by divine right, i.e. chosen by and representing God's will on earth, which further strengthened his absolute power. Today, most existing monarchies are constitutional, meaning that the monarch's power is limited by a constitution and often exercised within a democratic framework, with an elected government managing the affairs of state. In these systems, the role of the monarch is usually ceremonial, with little real power over political or governmental decisions. Examples of such constitutional monarchies include the United Kingdom, Sweden and Japan.

The adage "Si veut le Roy, si veut la loi" expressed by the French jurist Pierre Loisel (1536 - 1617) captures the essence of absolute monarchy, where the king's will is imposed as law. This principle reflects the conception of monarchical power at the time, when the monarch was not only the head of state, but also the supreme source of legislation. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is considered the ultimate authority, with his or her decisions and wishes having the force of law. This means that the monarch is not required to follow pre-established laws or consult other governing bodies before taking decisions. The law is therefore the direct product of the monarch's will and applies to all subjects without exception. This system concentrates all powers - legislative, executive and judicial - in the hands of the monarch. This approach to governance was typical of several European monarchies in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was part of an era when the notion of the divine right of kings was widely accepted, legitimising the monarch's absolute power as being granted and sanctioned by divine authority. The example of Neuchâtel as an ecclesiastical monarchy under the Prince-Bishop of Basel also illustrates this form of governance. In such monarchies, religious and civil authority were often merged, reinforcing the idea that royal or princely power was both temporal and spiritual. Today, these notions of absolute monarchy have largely evolved towards more democratic and constitutional forms of governance, where the power of the monarch is limited and balanced by other state institutions and by respect for constitutional laws.

The oligarchy

Oligarchy is a political system in which power is held and exercised by a small group of people. This form of government differs from monarchy, where power is concentrated in the hands of a single individual, usually a king or queen. In an oligarchy, power is shared between a few individuals who can be distinguished by their wealth, social status, education, corporate affiliation or membership of a certain elite. Unlike a democracy, where power is supposed to reside in the population as a whole, oligarchy involves a concentration of power within a small segment of society. This ruling minority can exert its influence in different ways, often by controlling the main economic, political or military levers. The decisions and policies adopted by an oligarchic government generally reflect the interests and visions of this small group, rather than those of the majority of the population.

Oligarchy can sometimes be disguised as a democracy, with formal elections and institutions. In practice, however, the real power lies in the hands of a few influential individuals or families. These groups can maintain their influence through various means, such as control of the media, large corporations, political funding, or networks of relationships and patronage. Historically, many political systems have had oligarchic characteristics. For example, in some ancient Greek city-states, power was often held by a small elite of wealthy and influential citizens. Similarly, at different periods in history, many societies have seen their government dominated by an aristocratic class or an economic elite. Oligarchy is often criticised for its lack of representativeness and fairness, as it excludes the majority of citizens from effective participation in the political process and tends to favour the interests of a small section of society to the detriment of the common good.

Democracy

Democracy is a political system based on the principle of popular sovereignty, where power belongs to the people. In a democracy, citizens play a central role in decision-making and the exercise of power, either directly or through elected representatives. In a direct democracy, citizens actively participate in the formulation and adoption of laws and policies. This direct exercise of power often takes the form of referendums or popular assemblies where citizens vote on specific issues. A historical example of direct democracy is the ancient Athenian city-state, where citizens met to debate and decide on the affairs of state. In most modern democracies, however, the system is representative: citizens elect representatives to govern them and make decisions on their behalf. This form of democracy allows for more practical management of a state's affairs, especially when the population is too large for everyone to participate directly in governance. Elected representatives, such as members of parliament, senators and the head of state, are supposed to reflect the will of the people and act in the general interest.

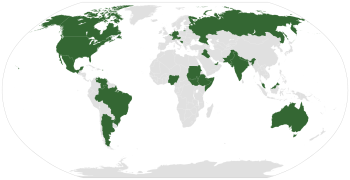

Representative democracy is usually accompanied by various institutions and mechanisms to ensure transparency, accountability and fairness in the political process. These include regular, free and fair elections, civil rights such as freedom of expression and association, a free press, and independent judicial systems to protect citizens' rights. Countries such as the United States, Germany, Canada and Australia are examples of representative democracies. In these systems, although citizens do not directly make political decisions, they play a crucial role by electing those who govern them and by participating in public debate, which shapes the state's policies and laws.

The quote from Heinrich Rudolf Schinz, an eminent 19th century Zurich jurist, underlines a fundamental understanding of democracy and the role of government, particularly in the Swiss context. His assertion that "all governments in Switzerland must recognise this, that they exist only insofar as they are of the people and act by the people and for the people" reflects the idea that the legitimacy of a government rests on its representation of and service to the people. This perspective is particularly relevant to Switzerland, a country that has long valued the principles of direct and participatory democracy. In 1830, when Schinz expressed this view, Switzerland was in the midst of a period of political transformation and development. His ideas resonated with the emerging democratic ideals of responsible government that was responsive to the needs and wishes of its citizens.

Schinz's emphasis on governments being "of the people" means that authorities must emanate from the consent and will of citizens. This implies a transparent and fair democratic process in which citizens have a meaningful role in electing their representatives and in political decision-making. The expression "governed by the people" underlines the importance of citizen participation in governance. In the Swiss system, this translates into mechanisms of direct democracy, such as referendums and popular initiatives, where citizens can directly influence legislation and public policy. As for "acting for the people", this refers to the obligation of governments to work in the general interest, implementing policies and laws that benefit society as a whole, rather than serving particular interests or elites. Schinz's vision is emblematic of the democratic principles that continue to be at the heart of governance in Switzerland, where power is exercised transparently and accountably, with the active participation of citizens. This reflects a commitment to a democracy that is not just a form of government, but also an expression of the values and aspirations of the people.

Abraham Lincoln's quote at the dedication of the cemetery at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 is one of the most famous speeches in American history and a pillar of democratic thought. His words, "May we, by our determination, see that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under the shadow of God, may be reborn in liberty... and that government of the people, by the people and for the people shall not perish from the face of the earth", resonate deeply with the values of democracy and freedom. Lincoln delivered this speech against the backdrop of a wrenching civil war, where the nation was deeply divided over issues of freedom and slavery. The Battle of Gettysburg, one of the bloodiest of the American Civil War, was a crucial moment in the conflict. By evoking the sacrifices of fallen soldiers, Lincoln sought to give meaning to those losses and to reinforce the nation's commitment to the principles of liberty and unity.

The idea that "government of the people, by the people, and for the people" must not "perish from the face of the earth" is a powerful affirmation of democratic principles. Lincoln emphasised that democracy was not only essential for the United States, but also an ideal to be preserved for all mankind. This concept implies that government should be based on the will of the people, that it should be exercised by representatives elected to serve the interests of the people, and that its ultimate goal must be the well-being of the people. The Gettysburg Address, though brief, had a profound and lasting impact, not only on American society, but also on the global perception of democracy and freedom. It continues to be cited as an eloquent example of leadership in times of crisis and a powerful reminder of the fundamental values on which democracies are built.