« John Locke and the Civil Government Debate » : différence entre les versions

| (5 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 48 : | Ligne 48 : | ||

{{Translations | {{Translations | ||

| fr = John Locke et le débat sur le gouvernement civil | | fr = John Locke et le débat sur le gouvernement civil | ||

| es = | | es = John Locke y el debate sobre el gobierno civil | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Ligne 67 : | Ligne 67 : | ||

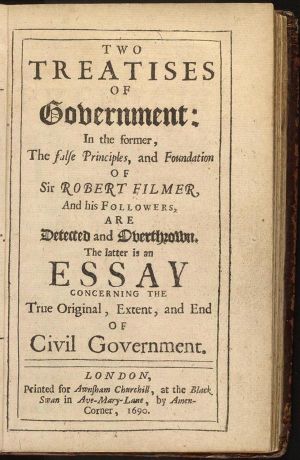

In 1689, he published the "Epistola de Tolerantia" - "Letter on Tolerance" - which was soon distributed on the continent. In 1690 he became famous with the publication of his main philosophical work, "An Essay concerning Human Understanding", which attacked the Cartesian doctrine of innate ideas and developed a theory of knowledge of an empirical - sensualist type. The same year, he published Two Treatises of Government, the first volume of which is a refutation of the theses set out in the "Patriarcha" by the absolutist writer Robert Filmer, and the second, better known under the title "Essay on Civil Government", proposes a vast reflection on the foundations and limits of the State. | In 1689, he published the "Epistola de Tolerantia" - "Letter on Tolerance" - which was soon distributed on the continent. In 1690 he became famous with the publication of his main philosophical work, "An Essay concerning Human Understanding", which attacked the Cartesian doctrine of innate ideas and developed a theory of knowledge of an empirical - sensualist type. The same year, he published Two Treatises of Government, the first volume of which is a refutation of the theses set out in the "Patriarcha" by the absolutist writer Robert Filmer, and the second, better known under the title "Essay on Civil Government", proposes a vast reflection on the foundations and limits of the State. | ||

In 1695, he again published the "Reasonableness of Christianity", which formulated the main ideas of deism. Interested in monetary problems, he was a member of the new Council of Commerce from 1696 onwards; his health declining, he had to resign in 1700. Retired to Oates, he wrote his "Paraphrases of the Epistles of Saint Paul" before dying on 28th October 1704. | In 1695, he again published the "Reasonableness of Christianity", which formulated the main ideas of deism.<ref>Stuart, M. (Ed.). (2015). A companion to Locke: Stuart/companion. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell. Url: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118328705.ch25</ref><ref>Riano, N. (2019, March 15). John Locke on “The Reasonableness of Christianity” ~ the imaginative conservative. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from Theimaginativeconservative.org website: https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2019/03/john-locke-reasonableness-of-christianity-nayeli-riano.html</ref><ref>Rabieh, M. S. (1991). The Reasonableness of Locke, or the Questionableness of Christianity. The Journal of Politics, 53(4), 933–957. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131861</ref><ref>Nuovo, V. (Ed.). (1996). John Locke and Christianity: Contemporary responses to the reasonableness of Christianity. South Bend, IN: St Augustine’s Press. Url: https://philpapers.org/rec/NUOJLA</ref> Interested in monetary problems, he was a member of the new Council of Commerce from 1696 onwards; his health declining, he had to resign in 1700. Retired to Oates, he wrote his "Paraphrases of the Epistles of Saint Paul" before dying on 28th October 1704. | ||

Locke was the one who wrote the constitution of North Carolina, imbuing the American state with his trademark. The founder of Pennsylvania was William Penn, who inherited Pennsylvania as a British colony. | Locke was the one who wrote the constitution of North Carolina, imbuing the American state with his trademark. The founder of Pennsylvania was William Penn, who inherited Pennsylvania as a British colony. | ||

| Ligne 73 : | Ligne 73 : | ||

In 1683, Locke had to flee England, he was linked to a conspiracy, bound by Lord Ashley, he had to flee England and settle in Amsterdam, which along with Rotterdam are the Mecca of Protestantism and freedom of thought. In the 17th century, the Dutch empire was the great power of the moment. | In 1683, Locke had to flee England, he was linked to a conspiracy, bound by Lord Ashley, he had to flee England and settle in Amsterdam, which along with Rotterdam are the Mecca of Protestantism and freedom of thought. In the 17th century, the Dutch empire was the great power of the moment. | ||

= | = Political Philosophy = | ||

Locke's thought is, unlike Hobbes, eminently religious. | |||

Locke, | Locke, in all his philosophy tries to answer four questions: | ||

# | #How can you think of a government that leads neither to civil war nor to oppression? A government that is another model than the one proposed by Hobbes. | ||

# | #How can the relationship between political and religious power be arranged? In the Letters on Tolerance the question is asked between the religious and the political. | ||

# | #How can we think of a government that is compatible with a new form of society that can be described as a market society? Locke is not only interested in a government that can avoid falling into civil war and oppression, but he also develops an economic type of reflection. | ||

# | #what is the epistemological status of knowledge? how do we know what we know? By what mechanism do we learn? | ||

The first question is basically the answer to Thomas Hobbes: what is good government? How and on what principles is it based so that it does not slide into civil war and oppression? | |||

[[Image:Locke treatises of government page.jpg|thumb|right]] | [[Image:Locke treatises of government page.jpg|thumb|right]] | ||

It is in the "Treaty on Civil Government" of 1690 that Locke answers Hobbes and the first question. Locke was as fascinated by science as Hobbes, and he started from the same premise: there is no point in thinking about good government if we don't know what we are made of. He goes back to the question of the state of nature. | |||

It is from a reflection on the state of nature that Locke arrives at his conclusions. | |||

In his Two Treaties on Civil Government of 1690, Locke also constructs his legal system from an exposition of the condition of man in relation to the state of nature. He set out four principles: | |||

# | #all men are naturally equal: there is no natural hierarchy which would compel one to put himself at the service of the other. | ||

# | #Man is of a free nature: he is not inherently conflictual, man is not of a belligerent nature and even less fearful. | ||

# | #Man is a profoundly rational being: man is driven by the need for reason, which pushes him to get closer to his fellow men, he defends Aristotle's vision that man is profoundly social. It is also his reason that makes him (man) understand the necessity of exchange (material and immaterial goods). | ||

# | #The state of nature is a peaceful state where freedom, equality and property reign: men are born free, equal and owners; at that time, God is the owner of man's body. When Locke asserted in 1790 that we are the sole owners of our bodies and minds, he was thinking of the ownership of ourselves. This is a natural law that will have very important political consequences. | ||

Man, although peaceful, rational, free, equal to his fellow man and owner of his body, is in an unstable state, this does not allow us to live together harmoniously, we cannot exchange well, the social order is not well organised, the political order is not established; we have to leave the state of nature in order to establish the state of society. | |||

Men in the state of nature are not unhappy, but the reason of men leads them to leave the state of nature towards the state of society. Consent is required in order to establish a state and a legitimate government. | |||

We give ourselves laws in order to set up a legitimate government built around four important principles : | |||

# | #consent: the acceptance of living together, consent is necessary in order to set up a state. Hobbes conceived power as a top-down power, at Locke there is the idea of a legitimate bottom-up power, consent allows this legitimacy to be established. The act of establishing the state must be a consensual act. | ||

# | #A legitimate government, an acceptable government, a modern government is a government that enshrines the principle of the separation of powers: Locke writes at the time of restoration, power must be shared between the king and parliament. | ||

# | #power is located in the legislative branch: the very heart of legitimate power is the power to legislate, to make and break the law. | ||

#Notion | #Notion of trust: fundamentally, political power is a deposit in the hands of parliament in the name of the trust placed in that parliament, it is because one has confidence in the parliament he is authorised to represent. There is the idea that legislative power is a repository of legitimacy because it has been entrusted with trust, because it has the trust of individuals. | ||

A legitimate government is a government that enshrines the power of parliament, the separation of powers, the confidence of individuals, and respect for religious freedom and freedom of worship; a government that respects equality, freedom and above all property is the antithesis of Thomas Hobbes. | |||

= John Locke, | = John Locke, Treatise on Civil Government, 1690 = | ||

This book answers the first question about which government is legitimate and the conditions for legitimate government to exist that allow freedom, equality and property to be established. | |||

At the time the term government meant state, a legitimate government is a government that succeeds or has succeeded in guaranteeing the rights to equality, freedom and property. | |||

Hobbes' concern was a concern for security and authority, Locke's concern was to guarantee the principles of liberty, equality and property; he would propose a state of separation of powers that guaranteed these fundamental rights. | |||

{{citation bloc| | {{citation bloc|However, although the state of nature is a state of freedom, it is by no means a state of licence. Certainly, a man in this state has an unquestionable liberty by which he may dispose as he wishes of his person or of what he possesses: but he has no liberty and no right to destroy himself, nor to harm any other person, or to disturb him in what he enjoys, he must make the best and noblest use of his liberty, which his own preservation requires of him. The state of nature has the law of nature, which must regulate it, and to which everyone is obliged to submit and obey: reason, which is this law, teaches all men, if they wish to consult it, that, being all equal and independent, no one must harm another, in relation to his life, his health, his liberty, his property...: For since all men are the work of an all-powerful and infinitely wise worker, the servants of a sovereign master, placed in the world by him and for his interests, they belong to him in their own right, and his work must last as long as it pleases him, not as long as it pleases another. And being endowed with the same faculties in the community of nature, no subordination can be supposed between us that would allow us to destroy each other, as if we were made for each other's use, in the same way that creatures of a rank inferior to ours are made for our use. Everyone is therefore obliged to preserve himself, and not to leave his post voluntarily to speak thus.}} | ||

Man is the owner of his body and his spirit, however the ultimate owner is still God forbidding us to dispose of our existence. We are owners of our body and mind, but God is co-owner. God is in our lives according to Locke. | |||

It is Locke's ambiguity that asserts ownership of our body and mind, but we cannot do everything. | |||

Paragraphs 7, 8, 9 and 10 clearly show the origin of Locke's principle of the separation of powers, which divides power in two: | |||

* | *power to execute | ||

* | *power to judge | ||

Locke's thinking is based on the idea that in the state of nature we have two essential powers: | |||

* | *power to preserve ourselves | ||

* | *power to punish | ||

It is the idea of the separation of powers that Locke transposes to the state of nature. | |||

{{citation bloc| | {{citation bloc|I therefore still assure you that all men are naturally in this state, which I call a state of nature, and that they remain there until, with their own consent, they have made themselves members of some political society: and I have no doubt that in the continuation of this Treaty this will not seem very obvious.}} | ||

One cannot be forced to live with others, one must consent to this possibility; there is no legitimate state if it is not based on a will, an assumed consent. For Hobbes, the contract of submission had to be signed, the act by which we gave our powers to Leviathan was a single act. Locke's logic is different. | |||

The title of Chapter III is "On the State of War", in response to Hobbes. | |||

{{citation bloc| | {{citation bloc|The state of war is a state of enmity and destruction. Whoever declares to another, either by word or deed, that he is angry with his life, must make this declaration, not with passion and haste, but with a tranquil mind: and then this declaration puts the one who made it, in the state of war with the one to whom he made it.}} | ||

In Chapter VIII is the birth of the State, once the State is established, it is no longer necessary to have the consent of all, but the consent of the majority. | |||

{{citation bloc| | {{citation bloc|All men being born equally, as it has been proved, in perfect freedom, and with the right to enjoy peacefully and without contradiction, all the rights and privileges of the laws of nature; everyone has, by nature, the power not only to preserve his own property, that is to say, his life, his liberty and his wealth, against all the enterprises, insults and attacks of others; but also to judge and punish those who violate the laws of nature, according to the merit of the offence, and even to punish with death, when it is a question of some enormous crime which he thinks deserves death. Now, because there can be no political society, and no such society can subsist unless it has in itself the power to preserve what is its own, and to punish the faults of its members, there alone is a political society, in which each member has stripped himself of his natural power and placed it in the hands of society, so that it may dispose of it in all sorts of causes, which do not prevent the laws established by it from always being invoked. By this means, with the exclusion of any judgment by individuals, society acquires the right of sovereignty; and since certain laws are established, and certain men are authorised by the community to enforce them, they put an end to all disputes that may arise between the members of that society in any matter of law, and punish the faults that any member may have committed against society in general, or against any member of its body, in accordance with the penalties laid down by the laws. And by this, it is easy to discern those who are or who are not together in political society. Those who make up one body, who have common laws established and judges to whom they can call, and who have the authority to end disputes and trials, who can be among them and to punish those who harm others and commit any crime: those are in society - but those who cannot civilise with one another; likewise to call to no court on earth, nor to any positive laws, are always in the state of nature; each one, where there is no other judge, being judge and executor for himself, which is, as I have shown before, the true and perfect state of nature.}} | ||

This book is basically the History of Humanity and the government of mankind. | |||

Starting from paragraph 105, Locke shows us how the history of human societies has evolved, he describes the process answering the question that when we look at the history of mankind, this process has existed, the state of nature has existed, there are societies that are still in the state of nature. | |||

Communities leave the state of nature to live together, but some have not evolved, the consequences are important, Locke introduces the argument that all the inventors of modern sociology will later take up is that human societies evolve in stages: human societies have a beginning and sometimes an end. | |||

The question is what is the beginning and what is the end? A society that has not left the state of nature is a society that has not evolved because the consequences of such a statement are that evolved societies can make those that have not evolved evolve. | |||

America was in a state of nature, if America is in the state of nature then it must be brought to the state of society, that's why we have to occupy the land, we have to colonise, we have to spread modern social life, we have to convince, impose, attract towards the evolved societies that are Great Britain, France and Europe. | |||

Behind this evolutionary vision of history lies a vision with dramatic consequences for part of the earth, namely the idea that our societies are divided into civilised and uncivilised societies. This binary vision of the international order is based on a step-by-step view of history, making European societies the most evolved; the implications of such an argument are in the intellectual order dramatic and important. | |||

Paragraphs 123 and 124 set out the aims of the state, the political society has a number of objectives. | |||

{{citation bloc|[…] | {{citation bloc|[…] It is not without reason that they seek society, and that they wish to join with others who are already united, or who have the intention of uniting and composing a body, for the mutual preservation of their lives, their liberties and their property; things which I call, by a general name, properties. | ||

For this reason, the greatest and principal end which men propose for themselves, when they unite in community and submit themselves to a government, is to conserve their properties, for the conservation of which many things are lacking in the state of nature.}} | |||

We are leaving the state of nature because we want to keep our rights, including the right of ownership, a legitimate state will be established that will protect our rights, including the right of ownership. | |||

The consequences for the international order are immense, if the state wants to guarantee private property, it must also do so outside the state. | |||

Locke | Locke asserts the importance of the legislative branch, as he is a strong supporter of the legislative branch. | ||

Locke should not be made the representative of modern colonialism, on the other hand Locke's philosophy, the philosopher of property rights, gave arguments to those who wanted to extend the territories of the large European countries. Locke had no particular ambitions, but he provided arguments for those who had ambitions through the rigour of his reasoning. | |||

The state that Locke designed is closer to us than that of [[The Birth of the Modern Concept of the State|Hobbes]]. Locke poses the question of the relationship between the religious and the political; the second problem is how to articulate life, how to arrange the relationship between political and religious power? | |||

= John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration, 1689 = | = John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration, 1689 = | ||

| Ligne 201 : | Ligne 201 : | ||

Locke believes that the modern state must guarantee security and in some cases enable people to resist oppression; in a certain sense, Locke is in favour of a right of resistance in the face of an authoritarian state with a despotic and absolutist tendency. | Locke believes that the modern state must guarantee security and in some cases enable people to resist oppression; in a certain sense, Locke is in favour of a right of resistance in the face of an authoritarian state with a despotic and absolutist tendency. | ||

Resistance to a monarchical and all-powerful state will be challenged by Montesquieu. | Resistance to a monarchical and all-powerful state will be challenged by [[Montesquieu and the definition of the Free State|Montesquieu]]. | ||

= Annexes = | = Annexes = | ||

Version actuelle datée du 19 novembre 2020 à 09:37

| Professeur(s) | Alexis Keller[1][2][3] |

|---|---|

| Cours | History of Legal and Political Thought: The Foundations of Modern Legal and Political Thought 1500 - 1850 |

Lectures

- Machiavelli and the Italian Renaissance

- The era of the Reformation

- The birth of the modern concept of the state

- John Locke and the Civil Government Debate

- Montesquieu and the definition of the Free State

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the new social contract

- The Federalist and American political theory

- John Stuart Mill, Democracy and the Limits of the Liberal State

Locke responded to Hobbes by resuming his reflection on the State. Basically, since Hobbes, the definition of the State as a sovereign legal person defined in terms close to those of Bodin's true Leviathan is no longer questioned. What is discussed is the relationship that the state has with individuals and citizens. Having defined the state, the question is no longer to redefine the state, but the relationship the state has with citizens.

After Hobbes, the questioning of the state changes, it is a question of seeing the place of the state in our lives, how far the state can go and what is the best possible form of state to enjoy freedom, equality and the right to property.

The questions are changing, becoming centred on the new relationship between the state and individuals; the first to attempt to propose a model of the state that is not an absolutist model, an all-powerful 'authoritarian model' of the state is John Locke. The context in which Locke publishes is particular, in other words, the context of seventeenth-century England sheds light on why Locke wanted to denounce the authoritarian vision of the State.

If Hobbes found a revolutionary period in England, Locke finds himself in a period when monarchy was restored: England's republican experiment ended in 1660 and the monarchy was restored. In 1660, Charles II came to power, his tutor was Hobbes. Thus, Hobbes' disciple ascended the throne.

England then experienced tensions between a royalist vision aiming to concentrate all powers in the hands of the monarchs and a parliamentarian vision; from 1660 onwards, there was a latent opposition between the king and parliament, which did not want the restoration of the monarchy to mean a loss of power.

This tension was compounded by another fact: when Charles II died in 1685, his successor James II loudly proclaimed his Catholicism, wishing not to impose Catholicism on England, but to return to values and practices closer to the Catholic Church. Since the middle of the 16th century, the Parliament and England have been Protestant of Anglican obedience. Having a king who was openly Catholic increased tensions from 1685 onwards.

From 1660 to 1685 tensions are managed, but from 1685 things get out of hand, the parliament can no longer stand a monarch who claims his power. It should be added that in 1685, the Edict of Nantes, which sealed the peace between Protestants and Catholics, was revoked in France. Louis XIV thus deprived the Protestants of their rights acquired in 1598.

There was a migration of militant Protestants to Europe, particularly to Holland, Switzerland (Geneva, Zurich and Basel), but also to England; the affirmation of the Catholic militancy of James II came at the wrong time, and the Protestant reflex was all the stronger in England at that time.

The Parliament quickly became increasingly unhappy with a man who asserted his Catholicism, but who held absolute power; in 1688 - 1689, the Parliament dismissed the King. It was the second English revolution that saw the dismissal of James II and the Parliament took power by calling on a Protestant king whose powers were largely amputated in favour of the Parliament.

This man is William of Orange who is the head of the House of Orange in Holland who had married the heiress to the throne of England and who agrees to take back the power of the throne of England; the motto of William of Orange is everything for freedom, for the Protestant faith and for Parliament.

This acceptance of the throne is not unconditional:

- that he agrees to sign the Bill of Rights of 1689, which guaranteed a certain number of fundamental rights, but above all recognised a certain number of fundamental powers for Parliament: to raise taxes and Parliament will be able to exercise a power of control over the King's cabinet, i.e. the ministers.

- that it accepts the Act of Tolerance which obliges the King to tolerate religious freedom and the free exercise of cults and religions; this is not only freedom of conscience, but also freedom to practise one's faith.

William of Orange takes back the British crown under certain conditions; Locke will publish in 1690 his work on civil government.

Biography[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

John Locke was born in Wrington on 26 August 1632, son of a Justice of the Peace clerk, captain in the parliamentary regiments during the civil war. During his studies at Oxford, whose Aristotelian philosophy and scholastic disputes he did not appreciate, the young Locke discovered Descartes, who gave him a taste for philosophy. He was also interested in Wallis' writings on geometry and L. Ward's writings on astrology.

Frightened by the extent of the religious quarrels, he opts at the same time for religious tolerance. Destined for a career in the church, he gave up medicine, which he practised in Oxford with a former college friend.

In 1666, he met Lord Ashley, future Duke of Shaftesbury, with whom he became friends and became his private physician, while also being in charge of the future Duke's affairs. As Lord Protector of Carolina, Lord Ashley asked Locke in 1669 to draw up the Constitution of this colony. At that time, he made his first trip to France. He returned in 1675, but had to return to England at the request of Lord Ashley, who was appointed President of the King's Privy Council.

A few years later, when, for political reasons, Lord Ashley was accused of conspiracy and had to flee to Holland, suspicions also arose that Locke was leaving England for the same destination. In 1683, he settled in Amsterdam, then in Rotterdam, where he presided over a small philosophical club.

After the English Revolution of 1688, Locke returned to England in 1689 on the same boat as Princess Marie, wife of William of Orange. He was then appointed Commissioner of Appeals.

In 1689, he published the "Epistola de Tolerantia" - "Letter on Tolerance" - which was soon distributed on the continent. In 1690 he became famous with the publication of his main philosophical work, "An Essay concerning Human Understanding", which attacked the Cartesian doctrine of innate ideas and developed a theory of knowledge of an empirical - sensualist type. The same year, he published Two Treatises of Government, the first volume of which is a refutation of the theses set out in the "Patriarcha" by the absolutist writer Robert Filmer, and the second, better known under the title "Essay on Civil Government", proposes a vast reflection on the foundations and limits of the State.

In 1695, he again published the "Reasonableness of Christianity", which formulated the main ideas of deism.[4][5][6][7] Interested in monetary problems, he was a member of the new Council of Commerce from 1696 onwards; his health declining, he had to resign in 1700. Retired to Oates, he wrote his "Paraphrases of the Epistles of Saint Paul" before dying on 28th October 1704.

Locke was the one who wrote the constitution of North Carolina, imbuing the American state with his trademark. The founder of Pennsylvania was William Penn, who inherited Pennsylvania as a British colony.

In 1683, Locke had to flee England, he was linked to a conspiracy, bound by Lord Ashley, he had to flee England and settle in Amsterdam, which along with Rotterdam are the Mecca of Protestantism and freedom of thought. In the 17th century, the Dutch empire was the great power of the moment.

Political Philosophy[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Locke's thought is, unlike Hobbes, eminently religious.

Locke, in all his philosophy tries to answer four questions:

- How can you think of a government that leads neither to civil war nor to oppression? A government that is another model than the one proposed by Hobbes.

- How can the relationship between political and religious power be arranged? In the Letters on Tolerance the question is asked between the religious and the political.

- How can we think of a government that is compatible with a new form of society that can be described as a market society? Locke is not only interested in a government that can avoid falling into civil war and oppression, but he also develops an economic type of reflection.

- what is the epistemological status of knowledge? how do we know what we know? By what mechanism do we learn?

The first question is basically the answer to Thomas Hobbes: what is good government? How and on what principles is it based so that it does not slide into civil war and oppression?

It is in the "Treaty on Civil Government" of 1690 that Locke answers Hobbes and the first question. Locke was as fascinated by science as Hobbes, and he started from the same premise: there is no point in thinking about good government if we don't know what we are made of. He goes back to the question of the state of nature.

It is from a reflection on the state of nature that Locke arrives at his conclusions.

In his Two Treaties on Civil Government of 1690, Locke also constructs his legal system from an exposition of the condition of man in relation to the state of nature. He set out four principles:

- all men are naturally equal: there is no natural hierarchy which would compel one to put himself at the service of the other.

- Man is of a free nature: he is not inherently conflictual, man is not of a belligerent nature and even less fearful.

- Man is a profoundly rational being: man is driven by the need for reason, which pushes him to get closer to his fellow men, he defends Aristotle's vision that man is profoundly social. It is also his reason that makes him (man) understand the necessity of exchange (material and immaterial goods).

- The state of nature is a peaceful state where freedom, equality and property reign: men are born free, equal and owners; at that time, God is the owner of man's body. When Locke asserted in 1790 that we are the sole owners of our bodies and minds, he was thinking of the ownership of ourselves. This is a natural law that will have very important political consequences.

Man, although peaceful, rational, free, equal to his fellow man and owner of his body, is in an unstable state, this does not allow us to live together harmoniously, we cannot exchange well, the social order is not well organised, the political order is not established; we have to leave the state of nature in order to establish the state of society.

Men in the state of nature are not unhappy, but the reason of men leads them to leave the state of nature towards the state of society. Consent is required in order to establish a state and a legitimate government.

We give ourselves laws in order to set up a legitimate government built around four important principles :

- consent: the acceptance of living together, consent is necessary in order to set up a state. Hobbes conceived power as a top-down power, at Locke there is the idea of a legitimate bottom-up power, consent allows this legitimacy to be established. The act of establishing the state must be a consensual act.

- A legitimate government, an acceptable government, a modern government is a government that enshrines the principle of the separation of powers: Locke writes at the time of restoration, power must be shared between the king and parliament.

- power is located in the legislative branch: the very heart of legitimate power is the power to legislate, to make and break the law.

- Notion of trust: fundamentally, political power is a deposit in the hands of parliament in the name of the trust placed in that parliament, it is because one has confidence in the parliament he is authorised to represent. There is the idea that legislative power is a repository of legitimacy because it has been entrusted with trust, because it has the trust of individuals.

A legitimate government is a government that enshrines the power of parliament, the separation of powers, the confidence of individuals, and respect for religious freedom and freedom of worship; a government that respects equality, freedom and above all property is the antithesis of Thomas Hobbes.

John Locke, Treatise on Civil Government, 1690[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

This book answers the first question about which government is legitimate and the conditions for legitimate government to exist that allow freedom, equality and property to be established.

At the time the term government meant state, a legitimate government is a government that succeeds or has succeeded in guaranteeing the rights to equality, freedom and property.

Hobbes' concern was a concern for security and authority, Locke's concern was to guarantee the principles of liberty, equality and property; he would propose a state of separation of powers that guaranteed these fundamental rights.

« However, although the state of nature is a state of freedom, it is by no means a state of licence. Certainly, a man in this state has an unquestionable liberty by which he may dispose as he wishes of his person or of what he possesses: but he has no liberty and no right to destroy himself, nor to harm any other person, or to disturb him in what he enjoys, he must make the best and noblest use of his liberty, which his own preservation requires of him. The state of nature has the law of nature, which must regulate it, and to which everyone is obliged to submit and obey: reason, which is this law, teaches all men, if they wish to consult it, that, being all equal and independent, no one must harm another, in relation to his life, his health, his liberty, his property...: For since all men are the work of an all-powerful and infinitely wise worker, the servants of a sovereign master, placed in the world by him and for his interests, they belong to him in their own right, and his work must last as long as it pleases him, not as long as it pleases another. And being endowed with the same faculties in the community of nature, no subordination can be supposed between us that would allow us to destroy each other, as if we were made for each other's use, in the same way that creatures of a rank inferior to ours are made for our use. Everyone is therefore obliged to preserve himself, and not to leave his post voluntarily to speak thus. »

Man is the owner of his body and his spirit, however the ultimate owner is still God forbidding us to dispose of our existence. We are owners of our body and mind, but God is co-owner. God is in our lives according to Locke.

It is Locke's ambiguity that asserts ownership of our body and mind, but we cannot do everything.

Paragraphs 7, 8, 9 and 10 clearly show the origin of Locke's principle of the separation of powers, which divides power in two:

- power to execute

- power to judge

Locke's thinking is based on the idea that in the state of nature we have two essential powers:

- power to preserve ourselves

- power to punish

It is the idea of the separation of powers that Locke transposes to the state of nature.

« I therefore still assure you that all men are naturally in this state, which I call a state of nature, and that they remain there until, with their own consent, they have made themselves members of some political society: and I have no doubt that in the continuation of this Treaty this will not seem very obvious. »

One cannot be forced to live with others, one must consent to this possibility; there is no legitimate state if it is not based on a will, an assumed consent. For Hobbes, the contract of submission had to be signed, the act by which we gave our powers to Leviathan was a single act. Locke's logic is different.

The title of Chapter III is "On the State of War", in response to Hobbes.

« The state of war is a state of enmity and destruction. Whoever declares to another, either by word or deed, that he is angry with his life, must make this declaration, not with passion and haste, but with a tranquil mind: and then this declaration puts the one who made it, in the state of war with the one to whom he made it. »

In Chapter VIII is the birth of the State, once the State is established, it is no longer necessary to have the consent of all, but the consent of the majority.

« All men being born equally, as it has been proved, in perfect freedom, and with the right to enjoy peacefully and without contradiction, all the rights and privileges of the laws of nature; everyone has, by nature, the power not only to preserve his own property, that is to say, his life, his liberty and his wealth, against all the enterprises, insults and attacks of others; but also to judge and punish those who violate the laws of nature, according to the merit of the offence, and even to punish with death, when it is a question of some enormous crime which he thinks deserves death. Now, because there can be no political society, and no such society can subsist unless it has in itself the power to preserve what is its own, and to punish the faults of its members, there alone is a political society, in which each member has stripped himself of his natural power and placed it in the hands of society, so that it may dispose of it in all sorts of causes, which do not prevent the laws established by it from always being invoked. By this means, with the exclusion of any judgment by individuals, society acquires the right of sovereignty; and since certain laws are established, and certain men are authorised by the community to enforce them, they put an end to all disputes that may arise between the members of that society in any matter of law, and punish the faults that any member may have committed against society in general, or against any member of its body, in accordance with the penalties laid down by the laws. And by this, it is easy to discern those who are or who are not together in political society. Those who make up one body, who have common laws established and judges to whom they can call, and who have the authority to end disputes and trials, who can be among them and to punish those who harm others and commit any crime: those are in society - but those who cannot civilise with one another; likewise to call to no court on earth, nor to any positive laws, are always in the state of nature; each one, where there is no other judge, being judge and executor for himself, which is, as I have shown before, the true and perfect state of nature. »

This book is basically the History of Humanity and the government of mankind.

Starting from paragraph 105, Locke shows us how the history of human societies has evolved, he describes the process answering the question that when we look at the history of mankind, this process has existed, the state of nature has existed, there are societies that are still in the state of nature.

Communities leave the state of nature to live together, but some have not evolved, the consequences are important, Locke introduces the argument that all the inventors of modern sociology will later take up is that human societies evolve in stages: human societies have a beginning and sometimes an end.

The question is what is the beginning and what is the end? A society that has not left the state of nature is a society that has not evolved because the consequences of such a statement are that evolved societies can make those that have not evolved evolve.

America was in a state of nature, if America is in the state of nature then it must be brought to the state of society, that's why we have to occupy the land, we have to colonise, we have to spread modern social life, we have to convince, impose, attract towards the evolved societies that are Great Britain, France and Europe.

Behind this evolutionary vision of history lies a vision with dramatic consequences for part of the earth, namely the idea that our societies are divided into civilised and uncivilised societies. This binary vision of the international order is based on a step-by-step view of history, making European societies the most evolved; the implications of such an argument are in the intellectual order dramatic and important.

Paragraphs 123 and 124 set out the aims of the state, the political society has a number of objectives.

« […] It is not without reason that they seek society, and that they wish to join with others who are already united, or who have the intention of uniting and composing a body, for the mutual preservation of their lives, their liberties and their property; things which I call, by a general name, properties.

For this reason, the greatest and principal end which men propose for themselves, when they unite in community and submit themselves to a government, is to conserve their properties, for the conservation of which many things are lacking in the state of nature. »

We are leaving the state of nature because we want to keep our rights, including the right of ownership, a legitimate state will be established that will protect our rights, including the right of ownership.

The consequences for the international order are immense, if the state wants to guarantee private property, it must also do so outside the state.

Locke asserts the importance of the legislative branch, as he is a strong supporter of the legislative branch.

Locke should not be made the representative of modern colonialism, on the other hand Locke's philosophy, the philosopher of property rights, gave arguments to those who wanted to extend the territories of the large European countries. Locke had no particular ambitions, but he provided arguments for those who had ambitions through the rigour of his reasoning.

The state that Locke designed is closer to us than that of Hobbes. Locke poses the question of the relationship between the religious and the political; the second problem is how to articulate life, how to arrange the relationship between political and religious power?

John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration, 1689[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Tolerance is a Christian necessity and duty, on the other hand, religious freedom must be a constituent part of this legitimate government, the modern state enshrines religious freedom and freedom of worship, finally, if religious freedom is to be enshrined, then perhaps it is primarily because there is no such thing as absolute and unique certainty or truth.

In other words, it is impossible to know the truth with certainty in the order of knowledge: in the name of this idea that absolute truth is difficult, comprehensible, attainable, one cannot impose a religion and belief in an era when churches tended to claim to hold the truth.

Locke does not want a state to impose a doctrine, a religion and a truth.

« I confess that it seems very strange to me (and I don't think I'm the only one in my opinion), that a man who ardently desires the salvation of his fellow man should make him expire in the midst of torments, even though he is not converted. »

For Locke, in order to save someone's soul there is something contradictory in the will to convert and kill someone for their belief.

« Tolerance, in favour of those who differ from others in matters of religion, is so conformed to the gospel of Jesus Christ, and to the common sense of all men, that it can be regarded as a monstrous thing, that there are people blind enough, not to see the necessity and advantage of it, in the midst of so much light that surrounds them. »

A good Christian is by definition a tolerant Christian.

Secondly, Locke divides the state and its competences. There is a strict separation between the temporal and the spiritual. The modern state for Locke is based on a strict division between the state and the religious. What strikes the reader is the very Protestant dimension and vision of the Calvinist church that Locke has.

« Let us now examine what is meant by the word 'church'. By this term I mean a society of men, who voluntarily join together to serve God in public, and to worship Him in the way they think pleasing to Him, and suitable for their salvation. »

Locke speaks of a free, voluntary society to describe the church; this is a vision that Luther and Calvin had advocated: state and church are a matter of individual consent.

The state that Locke draws for us is a state describing an open parliamentary monarchy, opposed to the top-down vision of power proposed by Hobbes, but above all Locke proposes a state concerned with guaranteeing individual rights: freedom, equality and private property.

Locke believes that the modern state must guarantee security and in some cases enable people to resist oppression; in a certain sense, Locke is in favour of a right of resistance in the face of an authoritarian state with a despotic and absolutist tendency.

Resistance to a monarchical and all-powerful state will be challenged by Montesquieu.

Annexes[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

References[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

- ↑ Alexis Keller - Wikipedia

- ↑ Alexis Keller - Faculté de droit - UNIGE

- ↑ Alexis Keller | International Center for Transitional Justice

- ↑ Stuart, M. (Ed.). (2015). A companion to Locke: Stuart/companion. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell. Url: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118328705.ch25

- ↑ Riano, N. (2019, March 15). John Locke on “The Reasonableness of Christianity” ~ the imaginative conservative. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from Theimaginativeconservative.org website: https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2019/03/john-locke-reasonableness-of-christianity-nayeli-riano.html

- ↑ Rabieh, M. S. (1991). The Reasonableness of Locke, or the Questionableness of Christianity. The Journal of Politics, 53(4), 933–957. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131861

- ↑ Nuovo, V. (Ed.). (1996). John Locke and Christianity: Contemporary responses to the reasonableness of Christianity. South Bend, IN: St Augustine’s Press. Url: https://philpapers.org/rec/NUOJLA