Microeconomics Principles and Concept

Ten principles of economics

Principle 1: People face trade-offs

To get one thing that we like we usually have to give up another thing that we also like. Making decisions requires trading off one goal against another.

When people are grouped into societies, they face different kinds of trade-offs. One trade-off society faces is between efficiency and equity. Efficiency means that society is getting the most it can from its scare resources. Equity means that the benefits of those resources are disturbed fairly among society’s members. Life’s trade-offs is important because people are likely to make good decisions only if they understand the options that they have available.

Principle 2: The cost of something is what you give up to get it

Because people face trade-offs, making decisions requires comparing the costs and benefits of alternative courses of action. In many cases, the cost of some action is not as obvious as it might first appear.

The opportunity cost of an item is what you give up to get that item. When making any decision, decision makers should be aware of the opportunity cost that accompany each possible action. In fact, they usually are.

Principle 3: Rational People think at the Margin

Decisions in life are rarely black and white. Economists use the term marginal chanes to describe small incremental adjustments to an exiting plan of action. Keep in mind that margin means edge, so marginal changes are adjustments around the edges of that you are doing.

In many situations, people make the best decisions by thinking at the margin. A rational decision maker takes an action if and only if the marginal benefit of the action exceeds the marginal costs.

Principle 4: People Respond to Incentives

Because people make decisions by comparing costs and benefits, their behavior may change, when the costs o benefits change. That is, people, respond to incentives. Public policy makers should never forget about incentives, because many policies change the costs of benefits that people face and, therefore, alter behavior. When policy makers fail to consider how their policies affect incentives, they often end up with results they did not intend. Policies can have effects that are not obvious in advance. When analyzing any policy, we must consider not only the direct effects but also the indirect effects that work through incentives. If the policy changes incentives, it will cause people to alter their behavior.

Principle 5: Trade can make everyone better off

The Americans and the Japanese are often mentioned in the news as being competitors to Europeans in the world economy. In some ways this is true, because American and Japanese firms do produce many of the same goods as European firms. Trade between Europe and the United States or Japan is not like a sports contest, where one side wins and the other side loses. In fact, the opposite is true: trade between two economies can make each economy better off.

Trade allows each person to specialize in the activities he or she does best. By trading with others, people can buy a greater variety of goods and services at lower cost. So Japanese and Americans are as much our partners in the world economy as they are our competitors.

Principle 6: Markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity

Most countries that once had centrally planned economies (Zentralplanung UdSSR) have abandoned this system and are trying to develop market economies. In a market economy, the decisions of a central planner are replaced by the decisions of millions of firms and households. Firms decide whom to hire and what to make. Households decide which firms to work for an what to buy with their incomes. These firms and households interact in the marketplace, where prices and self-interests guide their decisions.

After all, in a market economy, no one is considering the economic well-being of society as a whole. Free markets contain many buyers and sellers of numerous goods and services, and all of them are interested primarily in their own well-being. Yet, despite decentralized decision making and self-interested decision makers, market economies have proven remarkably successful in organizing economic activity in a way that promotes overall economic well-being.

Households and firms interacting in markets act as if they are guided by an “invisible hand” that leads them to desirable market outcomes. Prices are the instrument with which the invisible hand directs economic activity. Prices reflect both the value of a good to society and the cost to society of making the good. Because households and firms look at prices when deciding what to buy and what to sell, they unknowingly take into account the social benefits and costs of their actions. As a result prices guide these individual decision makers to reach outcomes that, in many cases, maximize the welfare of society as a whole.

There is an important corollary to the skill of the invisible hand in guiding economic activity: when the government prevents prices from adjusting naturally to supply and demand, it impedes the invisible hand’s ability to coordinate the millions of households and firms that make up the economy.

Principle 7: Governments can sometimes improve market outcomes

If the invisible hand of the market is so wonderful, why do we need government? One answer is that the invisible hand needs government to protect it. Markets work only if property rights are enforced. Yet there is another answer to why we need government: although markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity, this rule has some important exceptions. There are two broad reasons for a government to intervene in the economy – to promote efficiency and to promote equity.

Although the invisible hand usually leads markets to allocate resources efficiently, that is not always the case. Economists use the term market failure to refer to a situation in which the market on its own fails to produce an efficient allocation of resources. One possible cause of market failure is externality, which is the uncompensated impact of one person’s actions on the well-being of a bystander. For instance, the classic external cost is pollution. Another possible cause of market failure is market power, which refers to the ability of a single person (or small group) to influence market prices.

The invisible hand may also fail to ensure that economic prosperity is distributed equitably. A market economy rewards people according to their ability to produce things for which other people are willing to pay.

To say that the government can improve on market outcomes at times does not mean that it always will.

Principle 8: An economy’s standard of living depends on its ability to produce goods and services

It’s not surprising that a large variation in average income per head is reflected in various other measures of the quality of life and standard of living. Citizens of high- income countries have better nutrition, better health care and longer life expectancy than citizens of low-income countries, as well as more TV sets, more DVD players and more cars.

Changes in living standards over time are also large. Over the last 50 years, average incomes in Western Europe and North America have grown at about 2 per cent per year. On the other hand, average income in Ethiopia rose by only a third over this period – an average annual growth rate of around only 0.6 per cent.

What explains these large differences in living standards among countries and over time? The answer is surprisingly simple. Almost all variation in living standards is attributable to differences in countries’ productivity – that is, the amount of goods

and services produced from each hour of a worker’s time. In nations where worker can produce a large quantity of goods and services per unit of time, most people enjoy a high standard of living; in nations where workers are less productive, most people must endure a more meager existence. Similarly, the growth rate of a nation’s productivity determines the growth rate of its average income.

The relationship between productivity and living standards also has profound implications for public policy. When thinking about how any policy will affect living standards, the key question is how it will affect our ability to produce goods and services. To boost living standards, policy makers need to raise productivity by ensuring that workers are well educated, have the tools needed to produce goods and services, and have access to the best available technology.

Principle 9: Prices rise when the government prints too much money

Inflation is an increase in the overall level of prices in the economy. High inflation imposes various costs on society. Keeping inflation at a low level is a goal of economic policy makers around the world. What causes inflation? In almost all cases of high or persistent inflation, the culprit turns out to be the same – growth in the quantity of money. When a government creates large quantities of the nation’s money, the value of the money falls.

Principle 10: Society faces a short-run Trade-off between inflation and unemployment

When the government increases the amount of money in the economy, one result is inflation. Another result, at least in the short run, is a lower level of unemployment. The curve that illustrates this short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment is called the Phillips curve. Over a period of a year or two, many economic policies push infalation and unemployment in opposite directions. Policy makers face this trade-off regardless of whether inflation and unemployment both start out at high levels, low levels or somewhere in between. The Phillips curve is important for understanding the business cycle – the irregular and largely unpredictable fluctuations in economic activity, as measured by the number of people employed or the production of goods and services.

Policy makers can exploit the short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment using various policy instruments. By changing the amount that the government spends, the amount it taxes and the amount of money it prints, policy makers can influence the combination of inflation and unemployment economy experiences. Because these instruments of monetary and fiscal policy are potentially so powerful, how policy makers should use these instruments to control the economy, if at all, is a subject of continuing debate.

Thinking like an economist

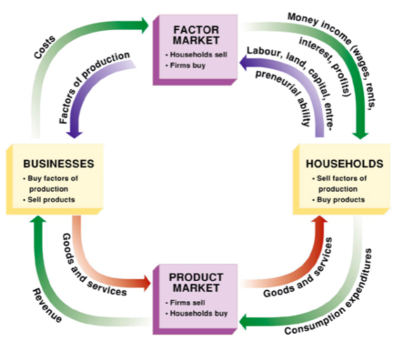

The cicular-flow-Diagram

To understand how the economy works, we must find some way to simplify our thinking about all these activities. In other words, we need a model that explains, in general terms, how the economy is organized and how participants in the economy interact with another.

One visual model of the economy is called a circular-flow diagram. In this model the economy is simplified to include only two types of decision makers – households and firms. Firms produce goods and services using inputs, such as labour, land and capita. These inputs are called the factors of production. Households own the factors of production and consume all the goods and services that the firms produce. Households and firms interact in two types of markets. In the markets for goods and services, households are buyers and firms are sellers. In particular, households buy the output of goods and services that firms produce. In the markets for the factors of production, households are sellers and firms are buyers. In these markets households provide the inputs that the firms use to produce goods and services.

The inner loop of the circular-flow diagram (economics. Page 23) represents the flows of inputs and outputs. The outer loop of the circular-flow diagram represents the corresponding flow of money.

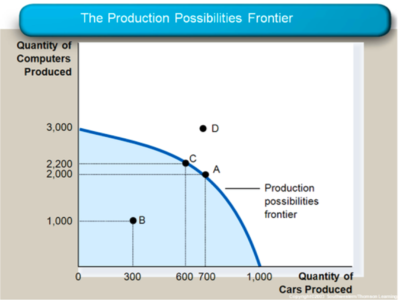

The production possibilities frontier

The production possibilities frontier is a graph that shows the various combinations of output that the economy can possibly produce given the available factors of production and the available production technology that firms can use to turn these factors into output.

Another point of the Ten principles of economics is that the cost of something is what you give up to get it. This is called the opportunity cost. The production possibilities frontier shows the opportunity cost of one good as measure in terms of the other good.

The production possibilities frontier simplifies a complex economy to highlight and clarify some basic ideas.

Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

Economics is also studied on various levels. Microeconomics is the study of how households and firms make decisions and how they interact in specific markets. Macroeconomics is the study of how households and firms make decisions and how they interact in specific markets. Macroeconomics is the study of economy-wide phenomena.

Microeconomics and macroeconomics are closely intertwined. Because changes in the overall economy arise from the decisions of millions of individuals, it is impossible to understand macroeconomic developments without considering the associated microeconomic decisions.

Positive Versus normative analysis

In general, statements about the world are of two types. Positive statements are descriptive. They make a claim about how the world is. A second type of statement is normative. Normative statements are prescriptive. They make a claim about how the world ought to be.

A key difference between positive and normative statements is how we judge their validity. We can, in principle confirm or refute positive statements by exclaiming evidence.

Many of the concepts that economists study can be expressed with numbers. When the price of something rises, people buy fewer. One way of expressing the relationships among variables is with graphs.

Graphs serve two purposes. First, when developing economic theories, graphs offer a way to express visually ideas that might be less clear if described with equations or words. Secondly, when analyzing economic data, graphs provide a way of finding how variables are in fact related in the world.

Graphs of a Single Variable

Three common graphs: the pie chart, the bar graph, the time-series graph.

Graphs of two variables: the coordinate System

Although the tree graphs are useful in showing how a variable changes over time or across individuals, such graphs are limited in how much they can tell us. These graphs display information only on a single variable. Economists are often concerned with the relationships between variables. Thus, they need to be able to display two variables on a single graph. The coordinate system makes this possible.

This type of graph is called a scatterplot because it plots scattered points. Two variables have a positive correlation if the point more to the right tends to be higher. If these variables typically move in the opposite direction we call this a negative correlation.

Often economists prefer looking how on variable affects another while holding everything else constant. To see how this is done, let’s consider one of the most important graphs in economics – the demand curve. The demand curve traces out the effect of a good’s price on the quantity of the good customers want to buy. Because the quantity of something demanded and the price move in opposite directions, we say that the two variables are negatively related. (The opposite is positive related.)

In economics, it is important to distinguish between movements along a curve and shifts of a curve. There is a simple way to tell when it is necessary to shift a curve. When a variable that is not named on either axis changes, the curve shifts

To answer questions about how much one variable responds to changes in another variable, we can use the concept of slope. The slope of a line is the ratio of the vertical distance covered to the horizontal distance covered as we move along the - line. This definition is usually written out in mathematically Symbols: Delta y durch Delta xSteigung. A small slope (a number close to zero) means that the demand cure is relatively flat.

Cause and effect

Economists often use graphs to advance an argument about how the economy works. In other words, the use graphs to argue about how one set of events causes another set of events.

If we are not able to hold variables contant, we might decide that one variable on our graph is causing changes in the other variable when actually those changes are caused by a third omitted variable not pictured on the graph. Even if we have identified the correct two variables to look at, we might run into a second problem – reserve causality. In other words we might decide that A causes B when in fact B causes A.

When you see a graph being used to support an argument about cause and effect, it is important to ask whether the movements of an omitted variable could explain the results you see.

Economists can also make mistakes about causality by misreading its direction. This problem is easier to see in the case of babies and baby cots. Couples often buy a baby cot in anticipation of the birth of a child. The cot comes before the baby, but we wouldn’t want to conclude that the sale of cots causes the population to grow.

Interdependence and the gains from trade

Every day I reply on many people from around the world, most of whom I do not know, to provide myself with the goods and services that I enjoy. Such interdependence is possible because people trade with another. People provide me and other costumers with the goods and services they produce because they get something in return.

Absolute Advantage

Economists use the term absolute advantage when comparing the productivity of one person, firm or nation to that of another. The producer that requires a smaller quantity of inputs to produce a good is said to have an absolute advantage

The opportunity of cost is whatever must be given up to obtain some item.

Economists use the term comparative advantage when describing the opportunity cost of two producers. The producer who gives up less of other goods to produce good X has the smaller opportunity cost of producing good X and is said to have a comparative advantage in producing it.

Although it is possible for one person to have an absolute advantage in both goods, it is impossible for one person to have a comparative advantage in both goods. Because the opportunity cost of one good is the inverse of the opportunity cost of the other, if a person’s opportunity cost of one good is relatively high, his opportunity cost of the other good must be relatively low. Comparative advantage reflects the relative opportunity cost. Unless two people have exactly the same opportunity cost, one person will have comparative advantage in one good, and the other person will have a comparative advantage in the other good.

Comparative Advantage and trade

Differences in opportunity cost and comparative advantage create the gains from trade. When each person specializes in producing the good for which he or she has a comparative advantage, total production in the economy rises, and this increase in the size of the economic cake can be used to make everyone better off. In other words, as long as two people have different opportunity costs, each can benefit from trade by obtaining a good at a price that is lower than his or her opportunity cost of that good.

Trade can benefit everyone in society because it allows people to specialize activities in which they have a comparative advantage.

Applications of comparative advantage

The principle of comparative advantage explains interdependence and the gains from trade. Because interdependence is so prevalent in the modern world, the principle of comparative advantage has many applications.

The principle of comparative advantage shows that trade can make everyone better off.