What is non-state violence? The Case of Afghan Conflict

So far, we have been interested in building the state from the state's point of view. History is written by the victors. We will analyse the issue of non-state violence by opening up competition for state formation to other actors. The focal point will be non-state violence. Relations between the State and non-state actors can be approached in different ways with different relationships.

Questioning non-state violence

The new global disorder? Proliferation of discourses on non-state violence

By the end of the Cold War, the counters were reset to zero. George Bush's notion of a "new world order" emerges. A series of theses put forward the idea of a new world order. The best known ideas are those of Charles Krauthammer's "unipolar moment" and the end of Francis Fukuyama's History. These theses had little success to the detriment of other theses. We are talking about different readings of the international system.

The most successful theses are the "towards global disorder" theses. The best-known theses are those of Samuel Huntington with the clash of civilizations and that of Robert Kaplan stated in The Coming Anarchy, How scarcity, crime, overpopulation, tribalism, and disease are rapidly destroying the social fabric of our planet. Both theses are based on non-state violence. The end of the Cold War is marked as the passage of the war as an inter-state affair that would become an internal civil war affair through non-state violence. The idea is to call into question the simplistic idea that with the end of the Cold War, it is the return to a form of the Middle Ages with anarchy and states that have not fulfilled their "contract" making non-state actors become the most dangerous objects for international security.

Thus, there is a proliferation of terms associated with non-state violence, which shows that state violence is no longer the most important threat:

- insurrection;

- terrorism;

- piracy;

- guerilla;

- transnational organized crime;

- civil war;

- militia;

- watchful;

- death squadrons;

- mafias;

- gangs;

- petty crime;

- ethnic conflicts;

- religious conflicts;

- Illegal combatants;

- rebellious;

- riots;

- Demonstrations;

- revolt;

- revolution;

- privatization of the war;

- uplift;

- mercenaries

- Subversion.

According to this reading of the international system, what is a matter for the State refers to law and order, and what is an issue for the inter-State would be a matter of disorder. Danger becomes failed states. These terms relate to the following concepts:"failed states" and "failed states" proposed by Richard Rotberg,"collapsed" as William Zartman uses it,"leviathan blade","near-states" as proposed by Robert H Jackson. All of these imply the proliferation of non-state violence, which is a corollary to the loss of the monopoly of violence by the state.

The restrictive definition of non-state violence

The theses we have seen have a totalizing ambition raising the criticism that they often function as self-fulfilling prophecies is that they have no explanatory value. Literature is primarily concerned with the causes of war, but we will instead focus on the consequences of war in particular social configurations.

Non-state violence as it emerged in 1989 is not a relevant starting point since, prior to the emergence of the modern state, non-state violent actors existed. We have already seen that many actors had already used armed force before the emergence of the modern state. It is precisely the competition between these players that makes it possible to achieve a Weberian monopoly that will allow the construction of centralised states in Europe. By definition, these actors can be described as "non-state". The simplistic theses on order and international disorder are anhistorical whereas in all the territories of the world, there are, at different times, political stakes with different actors trying to impose themselves on others. In fact, there is no real contradiction, at least historically, between non-state violence and the advent of the state, since the state is non-state violence.

Taking the example of mercenarism, Janice Thompson shows in Mercenaries, Pirates and Sovereigns: State-building and Extraterritorial Violence in Early Modern Europe published in 1994 how from the 16th century to the 19th century in Europe, there is the construction of a monopoly of internal violence with the accumulation of resources, but during this period which is supposed to be the period when European states are forming, one is not in a monopoly of external violence. Until the 19th century, the exercise of violence outside the borders of European states was mainly carried out by non-state violence, and therefore by private violence. The monopoly of external violence is the fact that states delegated some of these tasks to non-state actors such as mercenaries.

The sequence from the peace of Westphalia must be questioned. The nationalisation of our entire societies is a relatively recent development. The example of Janis Thompson is interesting in that it allows us to stay on top of Western states. If we apply a serious reading of these theories to civil wars, things are more complicated than the fact that non-state actors are enemies of the present state in order to bring down a state.

Max Weber defines the state as a political project that, in general, successfully asserts a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. The case of the Spanish Civil War which lasted from 1936 to 1939 shows that this project is not always successful. This conflict was triggered by a military rebellion against the elected government of the Second Spanish Republic. On both sides, Republicans and Franquists,"non-state" elements fought against anarchists, international volunteers, the POUM and the Phalange. The challenge has never been to bring about the collapse of the Spanish state.

Does this imply that the Spanish state as a political model has been questioned? Well, not necessarily. Both sides fought for state control rather than another form of political organization. Often, civil war can be a phenomenon in a specific context where the challenge is not to question the state itself. Thus, there is not necessarily a contradiction between "non-state violence" and the preponderance of the state. A civil war can be the result of internal competition to control the state.

Three levels of understanding must be considered, raising three questions:

- control: what is controlled by the government and what is outside government control. In a civil war, the first question that arises is: is there a disappearance of the central authority?

- Strategic objective - "State-making/ state-breaking": Is the objective to build the State or to dissolve the State? The question that emerges is to what extent does the conflict always lie within the territorial boundaries of a State or within a separate entity.

- effect: construction of the State/state bankruptcy. Depending on different contingencies, one can have a strengthened or collapsing state. When one looks at civil wars, one has to ask oneself what the effects will be, wondering to what extent, is there fragmentation, regionalization, polarization, or monopolization?

This sequencing of civil wars is an interesting way to approach the subject.

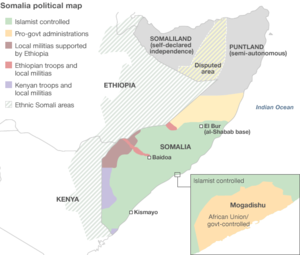

One case of regionalisation is Somalia. At the end of the Cold War, Somalia went through a number of conflicts. In this apparent anarchy, Somalia has been fragmented into more or less coherent entities such as Somaliland and Puntland. After a fragmentation of the country, some actors have recreated fairly coherent territories and the Somali conflict has become regionalized. At the same time, it is a precarious balance.

The Spanish case is a polarization case, i. e. we are fighting around a centre. It is a political field where the aim is to take power in Spain. The escalation of violence leads to polarization within a given state. The civil war in the United States was a polarization case with two different visions of what the United States was and what came out of it is a strengthened American state. These are civil wars that have contributed to the accumulation of resources within these states, allowing them to build these states through the classic mechanisms of "war making/state making".

When we talk about civil war, we are faced with potentially very different dynamics in terms of the relationship between war and state building.

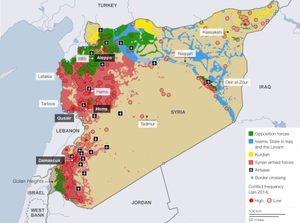

This map raises the issue of fragmentation with different mechanisms and effects. What is certain is that it would be reductive to understand what is happening in Syria today from the perspective of a failed state. Fragmentation is an issue. At the origin of the conflict, there was a polarization with the question of the seizure of power in Syria.

For some actors in Syria, socio-economic issues meant that there could be a sense of dispossession in favour of the Assad family. This is followed by a case of regionalisation with certain territories which are more than simply controlled by some actors setting up a system through the monopoly of domestic violence. The logic of monopolisation shows that this is a form of monopolisation of resources, since the Islamic State, in the occupied areas, has begun to develop characteristics similar to those of a State.

With this case, we are faced with various logics where the relationship to the State is not at all clear with fragmentation, regionalization and even monopolization. The relationship in state building is not one-way.

Le cas des conflits afghans

L’Afghanistan est un pays issu d’un processus de constitution fragile, jalonné d’un grand nombre de guerres, d’un grand nombre d’interventions extérieures et d’un pouvoir fragmenté entre différents clans. Se succèdent différentes phases dans le rapport à la construction de l’État. Cette lecture va permettre d’approcher d’une nouvelle façon les conflits afghans. Taylor et Botea dans Tilly: War-Making and State- Making in the Contemporary Third World publié en 2008 vont comparer le Vietnam et l’Afghanistan en montrant que le rapport à la construction de l’État est différent. Au Vietnam, la guerre civile a permis de construire un État alors qu’en Afghanistan, les guerres civiles ont empêché à l’État afghan d’arriver à un monopole de la violence domestique.

Un monopole jamais achevé ou la formation fragile de l’État afghan : 1747 – 1979

L’Afghanistan est un État fragile dès sa naissance dépendant de l’aide extérieure provenant de la Grande-Bretagne puis de l’URSS et des États-Unis. C’est une construction de l’État par la guerre avec une certaine proximité avec la thèse de Charles Tilly. Une guerre défensive va rassembler des tribus en 1838, 1878 et 1919.

La construction de l’État afghan est représentative des difficultés que l’on voit dans le cadre de construction d’un État hors du cadre occidental. C’est un État fragile : l’Empire de Ahmed Shah est déchiré au XVIIIème par des guerres dynastiques qui ne mènent pas au changement à la tête de l’État. L’État tire ses ressources plus de l’extérieur que de l’intérieur notamment par un financement externe du monopole plutôt qu’interne faisant qu’on s’éloigne du modèle européen. Ainsi, l’État afghan est dépendant du soutien extérieur. Il n’y a pas eu de colonisation directe, mais plutôt une domination indirecte. Cette logique va systématiquement être entretenue par des invasions étrangères. De la même façon, le départ des Soviétiques en 1989 mène à la guerre civile et à la fragmentation politique.

Dès les années 1830, l’Afghanistan n’est basé que sur un monopole externe de la violence. On retrouve ce que dit Thomson : on voit que la seule forme de monopole qu’avait l’État afghan était une politique étrangère commune dans le sens où les chefs locaux n’allaient pas faire de guerre à l’extérieur. En effet, l’État afghan n’est absolument pas en mesure de prétendre à un monopole sur la violence domestique qui est partagée avec d’autres autorités traditionnelles notamment par les khans et chefs locaux. Il s’agit ici d’une grande divergence avec la trajectoire européenne. Lorsque l’autorité centrale arrive à s’imposer, elle n’arrive jamais à le faire de manière efficace menant à un blocage au niveau de l’accumulation des ressources qui mènerait au monopole de la violence.

Les autorités locales traditionnelles sont uniquement soumises temporairement à l’autorité centrale en lui donnant de l’argent, cela malgré le monopole du roi sur l’importation des fusils d’Inde. L’idée de la construction de l’État reste sous-entendue. L’idée de la construction de l’État au travers de la constitution d’un monopole reste présente avec la constitution d’un pouvoir central, mais qui n’arrive pas à imposer son monopole. Les chefs locaux profitent de l’instabilité du pouvoir central. Cela leur donne une large autonomie. Cette situation a perduré pendant la guerre menée par les mujahedeens contre l’URSS. Il est possible de se demander si cela signifie que Norbert Elias a tort lorsqu’il affirme que la compétition mène à un monopole de la violence domestique.

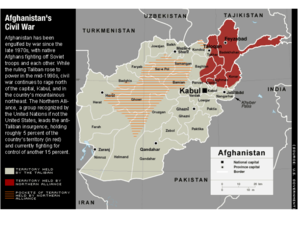

Il serait facile de dire que cela ne s’applique pas qu’à l’Afghanistan parce qu’il y a eu plusieurs tentatives d’établir un pouvoir central. Le contexte international empêche la mise en place de cette séquence. Selon Gilles Dorronsoro, du moins jusqu’à la retraite soviétique de 1989, la violente compétition et la guerre civile entre les commandants mudjahedeens a mené à l’élimination des uns par les autres jusqu’à la formation d’un relatif monopole de la violence domestique qui est l’État taliban. On entre dans une logique très elesienne avec la montée des talibans qui vont se débarrasser de leurs opposants pour imposer un monopole sur la violence domestique.

Les guerres afghanes (1989 à aujourd’hui) et les paradoxes de la violence non-étatique

L’émergence du Mollah Omar de Afghanistan se rapproche d’une forme de compétition entre acteurs avec les talibans qui vont s’imposer sur les autres et instaurer un monopole de la violence domestique. On est loin d’un État fort, mais il faut soulever qu’au niveau du monopole de la violence domestique, le processus était avancé.

Contrairement aux régimes précédents, les talibans, malgré un intérêt apparent plus important pour la religion que pour la politique, ont réussi à imposer un relatif monopole sur la violence domestique. Mais, c’est leur perte du contrôlé sur la violence externe qui a mené à leur chute après le 11 septembre 2001. Les talibans se sont fortement appuyés sur des combattants étrangers pour imposer le monopole de la violence domestique avec un début d’accumulation des ressources et en même temps, ces acteurs non-étatiques ont commis des attentats en dehors des frontières afghanes. Depuis, le cycle de violence en Afghanistan a repris une séquence comme après 1989 avec une invasion, des insurrections, des contre-insurrections dans le cadre d’une guerre civile. Ce sont des éléments qui peuvent renvoyer à Charles Tilly et Norbert Elias.

Le « chef de guerre d’Herat » contestait le gouvernement central de Harmid Kharzaï. Il dispose de ses propres forces de sécurité, levait ses propres impôts, avait ses propres services sociaux et un système de justice. Tout cela en dehors des compétences du pouvoir central. On pourrait alors dire que Amir Ismail Khan contrôle son propre État s’il n’y avait pas une forte compétition entre lui et gouvernement central. En 2004, l’armée afghane et les forces de Khan se sont affrontées. Khan a perdu et il a été nommé Ministre de l’Énergie devenant ainsi membre d’un gouvernement qu’il avait combattu jusque là.

Ismail Khan pose une question à propos de la définition de Maw Weber de l’État qui est que le monopole de la violence légitime que revendique l’État est toujours territorialisé. C’est un monopole de la violence légitime sur un territoire donné. En faisant varier les jeux d’échelles, peut être que les situations dites d’« effondrement de l’État » sont en réalité la constitution de plusieurs États. Si on regarde à l’échelle d’un quartier ou d’une rue, il y a un monopole de la violence et il peut y avoir de ce fait un État. Des réseaux d’interdépendances font qu’il est impossible dans la durée d’imposer un monopole de la violence légitime qui ne soit pas contesté par un pouvoir central ou un acteur qui veut prendre le pouvoir central. La dimension territoriale est très importante et le territoire n’est pas simplement une échelle spatiale que l’on veut faire varier. Le territoire se définit aussi par des chaînes d’interdépendances.

Après l’intervention en 2011, d’abord avec une coalition américano-britannique élargie à l’OTAN en 2003, il y a eu une régionalisation du pouvoir à l’échelle de l’Afghanistan de même qu’il y a eu une régionalisation du pouvoir entre 1993 et 1996. Depuis 2001, il y a des chefs de guerres qui contrôlent les grandes villes. Des seigneurs de guerre contrôlent l’appareil sécuritaire, fiscal et politique de toute une province en exerçant le pouvoir à partir de l’une des grandes villes d’Afghanistan. Par exemple, Amir Ismail Khan dispose d’une armée privée, il lève des impôts, il assure un certain nombre de services publics et administre la justice de manière légitime avec le consentement des parties à ce différend et en s’appuyant sur ses forces de sécurité. On peut dire qu’il dispose de son État, il y a un monopole de la violence légitime sur la province de Herat. Il est intéressant de noter que le terme « seigneur de guerre » évoque les seigneurs du Moyen-Âge.

La raison pour laquelle il est mieux de parler de fragmentation du monopole de la violence légitime à l’échelle Afghane est que les réseaux d’interdépendances qui relient les seigneurs de guerre entre eux ne sont jamais remis en question. Il y a des échanges commerciaux très importants à l’échelle Afghane, les réseaux de communications sont denses et relèvent d’interdépendances matérielles, il y a également des réseaux d’interdépendances symboliques très forts liés au fait que Amir Ismail Khan ne peut jamais contester son identité afghane et n’arrive pas à définir une identité propre à la province d’Erat. Même s’il conteste et critique très fortement le gouvernement central de Kaboul, cette contestation s’inscrit dans une opposition stratégique entre Amir Ismail Khan et Harmid Kharzaï montrant qu’il ne réfléchit pas en souverain sur son territoire. Son objectif à terme est de renforcer son pouvoir dans la province d’Erat afin de prendre la capitale pour prendre contrôle de l’ensemble du territoire afghan. On n’est pas simplement dans une configuration où il y aurait plusieurs monopoles de la violence légitime, mais des chefs de guerre sont en lutte constante pour le pouvoir central le distinguant d’une configuration interétatique classique. En 2004, l’armée afghane et les forces d’Ismail Khan s’affrontent et Ismail Khan perd. En 2004, le gouvernement central de Kharzaï essaie de consolider son monopole du pouvoir légitime et va prendre le contrôle de la région d’Erat. Dans le contexte afghan de l’époque, perdre face au pouvoir central veut dire perdre son autonomie politique face au pouvoir central et être incorporé au pouvoir central. L’intégration de Ismail Khan au sein du gouvernement afghan après sa défaite militaire marque sa défaite en matière d’autonomie et d’indépendance.

La question est de savoir ce que va advenir l’Afghanistan dans un futur à court ou à moyen terme, car à la fin de 2014, la mission de l’OTAN va se retirer du pays, mais il restera une force de 30000 hommes américains et de l’alliance dans le cadre d’une autre mission. Les forces militaires sont réduites, en même temps, le soutien apporté par les américains aux forces de police et à l’armée afghane se réduit progressivement. La question qui se pose est de savoir si le nouveau président va réussir à consolider son monopole de la violence légitime à l’échelle du territoire afghan ou si on va avoir un retour à des dynamiques de fragmentation ou encore une régionalisation autour des grandes villes ou est-ce qu’il va y avoir un changement de régime qui renverserait le pouvoir à Kaboul. Aujourd’hui, beaucoup d’acteurs en Afghanistan comptent continuer à jouer un rôle et faire en sorte que le rémige actuel fondé sur la construction de l’après 2001 reste en place. La question est de savoir si il va y avoir une continuation de la guerre civile ou des dynamiques de fragmentation. Il y a deux scénarios, à savoir, le même que celui auquel était l’Empire de Ahmed Shah au XVIIIème siècle avec de la violence non-étatique et de la fragmentions ou alors celui observé après le départ des soviétiques avec une guerre civile entre plusieurs concurrents jusqu’à ce que le dernier ne s’impose.