The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

Basically, it is a movement in which young people have had an extraordinary role, without them, certainly Civil Rights would not have been granted to African Americans reminding us of the role of youth in history.

Since January 15, 1986, the birthday of Pastor Martin Luther King, born on January 15, 1929, has been celebrated in the United States by a holiday that defines in most cities television and radio broadcasts and commemorations, especially in schools.[8][9][10][11]

Speech delivered on August 28, 1963 to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., is widely considered one of the greatest and most influential speeches of the 20th century.[12] According to U.S. Congressman John Lewis, who also spoke that day on behalf of the Coordinating Committee of Non-Violent Students. "By speaking as he did, he educated, he inspired, he guided not just the people who were there, but people across America and generations to come.[13]

During these celebrations, part of King's speech was rebroadcast with tributes to diversity and minority rights in the United States.[14][15][16][17]

This is not the first part of his speech in which he makes a deep and strong criticism of the social and racial inequality of the situation of blacks, but the end of his visionary speech about the American nation that will one day live on from its declaration of independence saying that all men were created equal; he also dreams of the day when his four children will no longer be judged by their colour, but by their character.

Shortly thereafter, Congress outlawed racial discrimination and guaranteed the black vote throughout the United States.

These laws are not new; they merely repeat amendments already passed following the abolition of slavery in 1865; the 14th Amendment guarantees political and civil rights to all and the 15th Amendment prohibits any state from preventing any citizen from voting based on his or her origin.

The United States was the only independent country in the Americas to legally discriminate against some of its citizens on the basis of their "race," while elsewhere other legal subterfuges were often and still sometimes used to discriminate first on the basis of skin color and poverty and now on the basis of poverty in general.

Actors for change

Why were African-American rights suddenly recognized in the mid-1960s? The United States was so powerful that it could have continued to accept segregation in the South.

African-Americans of the South

The first actors are the African Americans themselves, whose prospects broadened considerably after the Second World War.

The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court's policy direction is changing, becoming more progressive.[18][19][20][21]

Domestic and international context

Internal structural changes

In American society, there are structural changes, during the war there was the mechanization of part of the cotton crop which reduced rural employment, accelerating the process of urbanization in the southern states, many tenant farmers, small black and white peasants emigrated to the north, to the north of the United States and the west coast, between 1940 and 1959 there are a total of 3 million black people from the south who "vote with their feet", leaving and immigrating to the north and west in order to be full-fledged citizens.

With this migration they kept family in the South, a process of communication is intensified with the extension of the possibilities of mutual aid between the blacks of the South and the North and the East. This strengthens the electoral weight of blacks in the states of the East Coast and California; later on, politicians will have to deal with the racial issue.

In the South, with the beginning of modernization, this conjunctural change modifies the mentality of a part of the whites, in particular thanks to the white migrants who come to the sun-belt; absolute control over blacks through segregation is now superfluous.

The Cold War and Decolonization

We are in the midst of the Cold War and decolonization, the contradictions between the declared ideal of freedom and democracy that the United States wants to show the world is in complete contradiction with the reality of segregation in the South, which will be used more and more by the detractors of the United States to denounce them as racists and even fascists.

In 1944, Gunnar Myrdal published An American dilemma: The negro problem and modern democracy. [22] In this book, he insists on the contradiction between the democratic discourse of the American government and the practice of segregation and discrimination of blacks in the United States, pointing to it as the Achilles' heel of the United States.

The blacks had already begun to oppose the violation of the 14th and 15th amendments. Black people mobilized to fight fascism and defend democracy were characterized by segregation and discrimination. Axis forces used this argument in their propaganda forcing Congress to pass the Soldier Voting Act.[23][24][25][26]

When black soldiers returned from the war, they tried to register to vote; they were sure that the new legislation would allow them to vote in their home states; the whites often prevented them from doing so through violence.

They still face segregation, yet they will increasingly oppose it and demonstrate openly.

In the years 1948 and 1949 McCarthyism was in full swing, limiting what black Americans could do. The FBI is dominated by Hoover from 1924 to 1972 being obsessed with communist infiltration in the country; for all blacks who ask for civil rights and demand reforms are accused of communism and anti-Americanism; those who criticize racism face confiscation of their passports.[27][28]

McCarthyism dominates Congress and blocks any State Department initiative against segregation, as several State Department officials are accused of anti-American and communist activities. On the other hand, Truman had little interest in the black cause, but he was forced in 1949 to pass an executive order abolishing racial segregation in the U.S. military.[29][30]

The other thing is that in 1949, with the inauguration of the UN headquarters in New York, it will be increasingly difficult for the United States to defend democracy and the free world in the face of the newly decolonized nations of Africa and Asia that will be sitting at the UN.

It will be all the more difficult because representatives will try to travel around the country and will be prevented from having access to the facilities normally available in the States of the South, thereby tarnishing the image of the United States. The USSR will use this segregation as a weapon against the United States.

It is not only the African representatives, but also often those from Asia and the Caribbean. This is something that is beginning to make a bad impression and is creating democratic problems, but international pressure is still too weak to see the US government take action in the South.

The first stages of the fight: from 1955 to 1960

In 1954, things began to change for African Americans; until then the Supreme Court had been dominated by Southerners, suddenly it became more progressive. The role of the Supreme Court is essential for all citizens of the United States.

A minor event had major consequences; in 1955 the Supreme Court began debating Brown v. Board of Education; the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on behalf of a citizen attacked the separeted but egal doctrine that had been approved by the Supreme Court in 1896.[31]

This is a very important issue, when the judges are debating one of the supreme justices dies; he has to be replaced. Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren, who was an attorney general and a popular governor in California as well as a Republican, a man of his time, and he felt that justice should evolve with the times and not be as marked as it was before.[32][33][34][35][36][37]

NAACP lawyers were able to show that segregated schools lead black children to receive an education that is not equal to, but far below, that received by whites; the Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were illegal and forced public schools to integrate racially as soon as possible without defining legal degrees.[38]

This decision related to the appointment of Justice Warren will have many effects on other decisions made later, Warren will dominate the Supreme Court from 1954 to 1969; during this period the Supreme Court will make several decisions that reinterpret the U.S. Constitution in favor of the excluded.

He not only defended the equal rights of blacks, but also of women, Indians, Latin Americans, the poor, and the disabled, who gained new rights that guaranteed their freedom and equality.

The Supreme Court's decision making segregation in schools unconstitutional is followed by two decisions that make segregation illegal in federal authorities and public places.

This has enormous significance for black movements, as it obliges the federal state to support this decision everywhere in the territory, the federal state must even provide the army to support the enforcement of these new laws and the FIB must also be the guarantor of the enforcement of these federal laws.

After 1954, many blacks tried to enter public schools, colleges and universities, while others tried to get on public transportation, seeing the white response each time as a wave of violence.

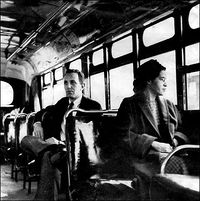

Rosa Parks in Montgomery in 1955 refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white man who was still standing. She was arrested then imprisoned, she is at the origin of the famous boycott of the buses of Montgomery by the blacks during more than one year propelling the young Martin Luther King then 26 years old and the Christian Leadership Conference at the head of the movement for racial equality.[39][40][41][42]

Rosa Parks was not only a modest seamstress, but also an NAACP activist and she knows very well the risk she is taking; for more than a year, blacks will walk to work, eventually forcing integration into public transport.

In 1957, in Arkansas, when Little Rock Middle School had to integrate black students, the segregationist governor refused to let nine black youths enter the school, forcing President Eisenhower to requisition more than 1,000 soldiers to guarantee the integration of the school; images of violence went round the world and provoked a great wave of protests while giving the USSR the opportunity to make people forget its interventions in Eastern Europe.[43][44][45][46]

In North Carolina, seating and boycotts took place against businesses that refused to serve blacks, as in Greensboro in 1960; the activists of these movements resumed the non-violent resistance sought by Gandhi, but were beaten by the population and the police, eventually forcing the establishments to accept blacks.

John F. Kennedy became president in January 1961.

In this context is elected Kennedy, it is the foreign policy in particular to face the policy of expansion of the Soviet Union in Asia, Africa and Cuba that interests him, he is also very anxious to keep the support of the votes of the democrats of the southern states, he is not really going to touch the racial question in the south of the United States.

To keep the support of the southern states, he is trying to prevent the Congress of Racial Equality's plan to have a group of whites and blacks known as the "Freedom Riders" travel by bus through the southern states; their goal was to test the southern states to see if the federal state would enforce segregation on buses and bus stations.[47][48][49][50][51][52]

The project also had an international scope, as segregation along federal highways also affected African and Asian diplomats who wanted to travel from New York to Washington; in Alabama and Mississippi, Freedom Riders were brutally attacked by members of the Ku Klux Klan.[53]

The case of the Voter Education Project in Mississippi

Kennedy sought to redirect this movement toward preparing blacks to register as voters: blacks were subject to "voter fitness" tests.[54][55] This route was less risky than the Freedom Riders.

He created the Voter Education Project in 1962 under the protection of the federal government and the FIB, but in Mississippi it shows the limits of Kennedy's commitment to blacks, pushing some blacks to renounce non-violence.[56][57]

Mississippi is one of the poorest states and a bastion of segregation; blacks who have been fighting for civil rights since 1945 are being laid off, chased off the farms they live on, beaten up and murdered.

What will begin to mobilize opinion is the lynching of a young black boy in Chicago who was 14 years old, Emmet Till; his mother in Chicago decided to allow the photo of his disfigured corpse to be published by the national and international press.[58][59][60][61][62][63]

There was a trial with an all-white jury, and twice the jury acquitted all the defendants; at the same time, it gave a boost to the courage of the blacks in Mississippi who began to demonstrate more directly.[64]

This change will accelerate with the arrival of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) which is another youth organization created in 1960, a multiracial Christian youth movement.[65][66][67][68]

The aims of this movement are not only to register blacks at the polling stations, but also to develop grassroots organizations at the local level that give priority to youth and women. Young people who join the SNCC drop out of school to participate in social change in small towns in the South, they represent the radical wing for the black representation movement that pushes Martin Luther King's struggle towards the centre.

In Mississippi they are going to do a huge job of recruiting communities with assemblies to mobilize people to read, to write, to take charge of their lives deciding to work for Kennedy's Voting Education Project; but the voter aptitude test is facing.[69]

In Mississippi in 1960, only 5 percent of blacks were in a position to vote; when they were not attacked, the candidates on the voters' lists were rejected. A year after the campaign was launched, 63 activists were assassinated without the Kennedy government reacting.

Washington denounces the lack of success of the Voting Education Project, which ceases to provide funding.

In 1963, when a group of students arrived in Mississippi to supervise the Voting Education Program, the FBI began to protect blacks.

They decided to play the game inviting several hundred students from the North and East to force the FBI to protect their Mississippi voting campaign. That's when two volunteers, two whites and a black from the South, disappear. The government sends hundreds of police and FBI agents to find them. It is only two months later that their bodies are found, the two white men shot and the black man tortured to death.

During their search, the FBI found a number of black bodies without opening investigations; this increases the feeling that the whites want to undermine the process of local self-determination; there is a change of strategy and they will do without the protection of the white students taking up arms especially since the FBI does not react to the murders in Mississippi.

Starting in 1953, the violence of the Ku Klux Klan redoubles, as well as that of the police and governors of the South begins to be shown on television screens, making it increasingly difficult to legitimize the UN headquarters in New York.

The great turning point for John F. Kennedy

President John F. Kennedy's Civil Rights Address on June 11, 1963.[70][71][72]

Kennedy did not take action until 1963 when Alabama police cracked down on a civil rights and integration protest, mostly youth and school children demonstrating; these events occurred at the same time as a movement for African unity was taking place in Addis Ababa.

The Soviet press seized on this to criticize the United States, and Kennedy made a speech on television calling on Congress to pass a civil rights framework law.[73][74][75]

In August 1963, the entire civil rights movement gathered more than 200,000 people for a march to Washington, D.C., leading to a tacit agreement between Kennedy and the organizers to avoid radical speeches in exchange for a framework law that would allow the dissemination of soothing images of the march.

Part of Martin Luther King's visionary speech is in which he portrays himself as Moses to the whole of reconciled America. After Kennedy's assassination in 1963, Lyndon B Johnson, the first president from the South, takes up the torch and obtains congressional approval guaranteeing black suffrage; the story ends with a legislative triumph.

Martin Luther King, Jr. delivering his "I Have a Dream" speech.

After 1965: division of the black movement

After 1965, the black movement split with the Civil Right of 1964 which forbids segregation leading to the creation of a commission to control the "segregationist" fact; this is an end in itself for those like Martin Luther King who advocate the fight for concrete equality, socio-economic equality and total integration, however one frankly wants black separatism.[76]

We must not forget that there is a huge difference between blacks from the North, South and West Coast, because the 1965 Voting Act was a victory only for the 11 million blacks in the South, but not for the 7 million blacks living in the ghettos.

We enter a period of riots in the ghettos of the North and California exploding in violent revolts characterized by looting, fires, police and military repression; these years are marked by enormous violence and by murders after that of Kennedy in 1963 by those of Malcolm X in 1965, those of Luther King and Robert Kennedy in 1968.

It is the gulf between the northern ghettos and the suburban villa zones that explains the explosion and the solution that would be a kind of Marshall Plan.

Johnson launches a policy to fight poverty, but at the same time he sinks into the Vietnam War where blacks are killed disproportionately. In 1968, youth revolts shook the world and the United States, leading to the election of Nixon as president.

The deep south is still reacting to all these laws with the candidacy of Wallace who creates an American Independent Party in order to have a segregationist as president, but who fails showing that mentalities take a long time to evolve and that it is necessary to continue to claim rights that are never acquired for everyone.

Annexes

Brown v. Board of Education - les arrêts

- Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 493 (1954)

- Brown v. Board of Education 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

- Bolling v. Sharpe 347 U.S. 497 (1955)

References

- ↑ Aline Helg - UNIGE

- ↑ Aline Helg - Academia.edu

- ↑ Aline Helg - Wikipedia

- ↑ Aline Helg - Afrocubaweb.com

- ↑ Aline Helg - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Aline Helg - Cairn.info

- ↑ Aline Helg - Google Scholar

- ↑ Weiss, Jana (2017). "Remember, Celebrate, and Forget? The Martin Luther King Day and the Pitfalls of Civil Religion", Journal of American Studies

- ↑ Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service official government site

- ↑ [King Holiday and Service Act of 1994] at THOMAS

- ↑ Remarks on Signing the King Holiday and Service Act of 1994, President William J. Clinton, The American Presidency Project, August 23, 1994

- ↑ Stephen Lucas et Martin Medhurst, « "I Have a Dream" Speech Leads Top 100 Speeches of the Century », University of Wisconsin News, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 15 décembre 1999 (lire en ligne).

- ↑ A "Dream" Remembered, NewsHour, 28 août 2003.

- ↑ I Have a Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Future of Multicultural America, James Echols – 2004

- ↑ Alexandra Alvarez, "Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor", Journal of Black Studies 18(3); doi:10.1177/002193478801800306.

- ↑ Hansen, D, D. (2003). The Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York, NY: Harper Collins. p. 58.

- ↑ "Jones, Clarence Benjamin (1931– )". Martin Luther King Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle (Stanford University).

- ↑ Horwitz, Morton J. (Winter 1993). "The Warren Court And The Pursuit Of Justice". Washington and Lee Law Review. 50.

- ↑ Powe, Jr., Lucas A. (2002). The Warren Court and American Politics. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Swindler, William F. (1970). "The Warren Court: Completion of a Constitutional Revolution" (PDF). Vanderbilt Law Review. 23.

- ↑ Driver, Justin (October 2012). "The Constitutional Conservatism of the Warren Court". California Law Review. 100 (5): 1101–1167. JSTOR 23408735.

- ↑ Myrdal, Gunnar (1944). An American dilemma: The negro problem and modern democracy. New York: Harper & Bros.

- ↑ Inbody, Donald S. The Soldier Vote War, Politics, and the Ballot in America. Palgrave Macmillan US :Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- ↑ Schønheyder, Caroline Therese. “U.S. Policy Debates Concerning the Absentee Voting Rights of Uniformed and Overseas Citizens, 1942-2011.” Thesis / Dissertation ETD, 2011.

- ↑ Coleman, Kevin. (2010). The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act: Overview and Issues.

- ↑ US Policy Debates Concerning the Absentee Voting Rights, United States. Congress, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1944

- ↑ Krenn, Michael L. The African American Voice in U.S. Foreign Policy since World War II. Garland Pub., 1999.

- ↑ Maxwell, William J. F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover's Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature. Princeton Univ. Press, 2017.

- ↑ Executive Order 9981 - On July 26, 1948, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 establishing equality of treatment and opportunity in the Armed Services. This historic document can be viewed here.

- ↑ Jon E. Taylor, Freedom to Serve: Truman, Civil Rights, and Executive Order 9981 (Routledge, 2013)

- ↑ Patterson, James T. (2001). Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195156324.

- ↑ Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506557-2.

- ↑ Belknap, Michael (2005). The Supreme Court Under Earl Warren, 1953–1969. The University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-563-0.

- ↑ Cray, Ed (1997). Chief Justice: A Biography of Earl Warren. ISBN 978-0-684-80852-9.

- ↑ Powe, Lucas A. (2000). The Warren Court and American Politics. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674006836.

- ↑ Schwartz, Bernard (1983). Super Chief: Earl Warren and His Supreme Court, A Judicial Biography. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814778265.

- ↑ Urofsky, Melvin I. (2001). The Warren Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576071601.

- ↑ See, e.g., Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education, Berea College v. Kentucky, Gong Lum v. Rice, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, and Sweatt v. Painter

- ↑ Aguiar, Marian; Gates, Henry Louis (1999). "Southern Christian Leadership Conference". Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience. New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 0-465-00071-1.

- ↑ Cooksey, Elizabeth B. (December 23, 2004). "Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)". The new Georgia encyclopedia. Athens, GA: Georgia Humanities Council. OCLC 54400935. Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- ↑ Fairclough, Adam. To Redeem the Soul of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King, Jr. (University of Georgia Press, 2001)

- ↑ Garrow, David. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1986); Pulitzer Prize

- ↑ Faubus, Orval Eugene. Down from the Hills. Little Rock: Democrat Printing & Lithographing, 1980. 510 pp. autobiography.

- ↑ Anderson, Karen. Little Rock: Race and Resistance at Central High School (2013)

- ↑ Baer, Frances Lisa. Resistance to Public School Desegregation: Little Rock, Arkansas, and Beyond (2008) 328 pp. ISBN 978-1-59332-260-1

- ↑ Kirk, John A. "Not Quite Black and White: School Desegregation in Arkansas, 1954-1966," Arkansas Historical Quarterly (2011) 70#3 pp 225–257 in JSTOR

- ↑ Meier, August; Rudwick, Elliott M. (1975). CORE: A Study in the Civil Rights Movement, 1942-1968. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252005671.

- ↑ Frazier, Nishani (2017). Harambee City: Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1682260186.

- ↑ Congress of Racial Equality Official website

- ↑ Harambee City: Archival site incorporating documents, maps, audio/visual materials related to CORE's work in black power and black economic development.

- ↑ Catsam, Derek (2009). Freedom's Main Line: The Journey of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813173108.

- ↑ Niven, David (2003). The Politics of Injustice: The Kennedys, the Freedom Rides, and the Electoral Consequences of a Moral Compromise. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781572332126.

- ↑ "Civil rights rider keeps fight alive" . Star-News. 30 June 1983. pp. 4A

- ↑ PEDAGOGÍA INTERNACIONAL: CUANDO LA INSTRUCCIÓN CÍVICA SE CONVIERTE EN UN PELIGRO PARA LA VIDA..., R. UEBERSCHLAG - The student, international student magazine.

- ↑ Whitby, Kenny J. The Color of Representation: Congressional Behavior and Black Interests. University of Michigan Press, 1997. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.14985.

- ↑ The Voter Education Project, King Research & Education Institute ~ Stanford University.

- ↑ Voter Education Project, Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ↑ Tyson, Timothy B. (2017). The Blood of Emmett Till, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-1484-4

- ↑ Anderson, Devery S. (2015). Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2015.

- ↑ Houck, Davis; Grindy, Matthew (2008). Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press, University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-934110-15-7

- ↑ Whitaker, Hugh Stephen (1963). A Case Study in Southern Justice: The Emmett Till Case. M.A. thesis, Florida State University.

- ↑ The original 1955 Jet magazine with Emmett Till's murder story pp. 6–9, and Emmett Till's Legacy 50 Years Later" in Jet, 2005.

- ↑ Documents regarding the Emmett Till Case. Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- ↑ Federal Bureau of Investigation. Prosecutive Report of Investigation Concerning (Emmett Till) Part 1 & Part 2 (PDF).

- ↑ Hogan, Wesley C. How Democracy travels: SNCC, Swarthmore students, and the growth of the student movement in the North, 1961–1964.

- ↑ Hogan, Wesley C. Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC's Dream for a New America, University of North Carolina Press. 2007.

- ↑ Carson, Clayborne (1981). In Struggle, SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Founded ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans.

- ↑ The Voter Education Project, King Research & Education Institute ~ Stanford University.

- ↑ Goduti Jr., Philip A. (2012). Robert F. Kennedy and the Shaping of Civil Rights, 1960-1964. McFarland. ISBN 9781476600871.

- ↑ Goldzwig, Steven R.; Dionisopolous, George N. (1989). "John F. Kennedy's civil rights discourse: The evolution from "principled bystander" to public advocate". Communication Monographs. Speech Communication Association. 56 (3): 179–198. doi:10.1080/03637758909390259. ISSN 0363-7751.

- ↑ Loevy, Robert D. (1997). The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Law That Ended Racial Segregation (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791433614.

- ↑ Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Pub.L. 88–352 , 78 Stat. 241 , enacted July 2, 1964)

- ↑ Civil Rights Act Passes in the House ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ↑ "A Case History: The 1964 Civil Rights Act". The Dirksen Congressional Center.

- ↑ The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Background and Overview (PDF), Congressional Research Service