« Supply, demand and government policies » : différence entre les versions

(Page créée avec « 7 Consumers, producers and the efficiency of markets In this chapter we take up the topic of welfare economics, the study of how the allocation of resources affects econo... ») |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| (43 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 1 : | Ligne 1 : | ||

Based on a course by Federica Sbergami<ref>[https://www.unige.ch/gsem/en/research/faculty/all/federica-sbergami/ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Genève]</ref><ref>[https://www.unine.ch/irene/home/equipe/federica_sbergami.html Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Neuchâtel]</ref><ref>[https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/14836393_Federica_Sbergami Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur Research Gate]</ref> | |||

{{Translations | |||

| fr = Offre, demande et politiques gouvernementales | |||

| es = Oferta, demanda y políticas gubernamentales | |||

| it = Domanda, offerta e politiche governative | |||

| pt = Oferta, procura e políticas governamentais | |||

| de = Angebot, Nachfrage und Regierungspolitik | |||

}} | |||

Consumer surplus | {{hidden | ||

|[[Introduction to microeconomics]] | |||

|[[Microeconomics Principles and Concept]] ● [[Supply and demand: How markets work]] ● [[Elasticity and its application]] ● [[Supply, demand and government policies]] ● [[Consumer and producer surplus]] ● [[Externalities and the role of government]] ● [[Principles and Dilemmas of Public Goods in the Market Economy]] ● [[The costs of production]] ● [[Firms in competitive markets]] ● [[Monopoly]] ● [[Oligopoly]] ● [[Monopolisitc competition]] | |||

|headerstyle=background:#ffffff | |||

|style=text-align:center; | |||

}} | |||

Government intervention in economic markets takes the form of a variety of strategies, each targeting specific aspects of the market to achieve defined socio-economic objectives. These government interventions, which are essential for regulating the economy, include measures such as bans, product regulations, quantity and price controls, and the use of taxes and subsidies. | |||

The outright banning of certain markets is a striking example of government intervention. This extreme measure is generally adopted for reasons of public safety, health or the environment. A case in point is the ban on illegal drugs, where governments seek to protect public health and reduce crime. Similarly, the ban on asbestos-containing products in many countries is a response to public health concerns about its harmful effects on the lungs. | |||

In terms of product regulation, governments often impose strict standards to ensure the quality, health and safety of products. For example, vehicle emission regulations aim to reduce air pollution, while food standards guarantee the safety and quality of food products. These regulations protect consumers and help preserve the environment, but they can also increase production costs for companies. | |||

Quantity control is another form of intervention, used to regulate the supply of certain products on the market. During the Second World War, for example, many countries set up rationing systems for essential products such as food and fuel, thus ensuring a fair distribution of limited resources. In international trade, import quotas are often used to protect local industries from foreign competition. | |||

Controlling prices by setting price ceilings or price floors is another strategy used to influence the market. Price ceilings can help make essential goods more affordable during crises, as was the case with price caps on essential medicines in some countries. Price floors, meanwhile, are often used in agriculture to ensure a minimum income for farmers, although this can sometimes lead to overproduction and inefficiencies. | |||

Finally, taxes and subsidies are powerful fiscal tools for influencing market behaviour. Taxes on tobacco and alcohol, for example, aim to reduce the consumption of these products, which are harmful to health. Subsidies, on the other hand, can encourage beneficial activities, such as renewable energy subsidies to promote a sustainable energy transition. | |||

These government interventions have a profound impact on the balance of supply and demand in markets, and therefore on the economy as a whole. They require careful planning and ongoing evaluation to ensure that they achieve the desired objectives without causing undesirable effects. The complexity of these interventions lies in the fact that they must take account of the needs and reactions of the various market players, while balancing economic, social and environmental objectives. | |||

= Price control = | |||

== Price controls == | |||

State price controls are a form of economic intervention used to regulate market prices in situations where the equilibrium price, i.e. the natural price resulting from the meeting of supply and demand, is deemed to be inadequate or unfair. This intervention can take different forms depending on the context and the objective, and generally involves setting price ceilings or floors for certain goods or services. A classic example of price controls is interest rate limits, often referred to as usury limits. This measure is put in place to prevent lenders from charging excessively high interest rates, particularly on consumer loans and credit cards. By setting a maximum rate, the government seeks to protect borrowers from abusive lending practices and maintain financial stability. | |||

Minimum wages are another common form of price control. Here, the aim is to ensure that workers receive a sufficient income to live on. By setting a statutory minimum wage, the state seeks to combat poverty and ensure that workers are paid fairly. However, the minimum wage can also be a source of debate, with some arguing that it could reduce employment opportunities for low-skilled workers. | |||

Rent control is another intervention where the state sets a cap on the amount that landlords can charge for renting out accommodation. This measure is usually taken in high-density urban areas where rents can rise very high, making housing unaffordable for many residents. Rent controls aim to make housing more affordable, but they can also discourage investment in rental accommodation and limit the supply available. | |||

Finally, agricultural support prices are a form of price control where the state sets a floor price for agricultural products. This measure aims to protect farmers from fluctuations and volatility in market prices, thereby guaranteeing a stable income. However, support prices can lead to overproduction and market distortions, often requiring the government to buy and store surpluses. | |||

These forms of price control, although motivated by positive intentions, can have complex and sometimes undesirable consequences. Balancing the social and economic benefits of these policies against their potential side-effects is a major challenge for policy-makers. It is crucial to continually assess the impact of these interventions and adjust them to meet the changing needs of the economy and society. | |||

State intervention in prices may also be motivated by the need to correct market inefficiencies caused by an imbalance of power between buyers and sellers. In some cases, a market player may have sufficient power to significantly influence the price of a good or service, thereby distorting the efficient functioning of the market. Price controls are a strategy that the state can use to restore balance and ensure fairer competition. An important aspect of price controls is that they are often less costly than introducing subsidies. Subsidies, although effective in supporting certain industries or in making certain goods and services more affordable, have to be financed by tax revenues, which implies a cost for the state and, ultimately, for taxpayers. Price controls, on the other hand, do not require direct state expenditure, which makes them an attractive option in certain contexts. | |||

It is also important to note that price control decisions are not always taken solely on the basis of objective economic analysis. Sometimes they may be the result of pressure from lobbying groups seeking to take advantage of a rent-seeking situation. These "rent-seeking activities" can lead to policies that favour certain groups or industries to the detriment of overall economic efficiency or equity. | |||

Finally, price controls can be used as a tool to control high inflation. In situations where inflation is spiralling out of control, the state can impose a price freeze or price ceilings to prevent costs from continuing to escalate. However, while this may offer temporary relief, it does not address the underlying causes of inflation and can lead to shortages if prices are kept below the level where supply meets demand. | |||

In all cases, it is essential to recognise that price controls, while useful in certain circumstances, are an intervention that should be used with caution. It must be accompanied by a rigorous assessment of its potential impact, both immediate and long-term, on the economy and society. | |||

== Price ceilings == | |||

A price ceiling, or maximum price, is an upper limit set by the government above which it is forbidden to sell a good or service. This intervention is generally implemented when the government considers that the market equilibrium price, i.e. the price at which supply equals demand, is excessively high and potentially harmful to consumers. The main objective of a price cap is therefore to make goods or services more affordable, particularly for essential goods such as housing, energy or food. | |||

It is important to stress that the effectiveness of a price cap depends on how it is positioned in relation to the equilibrium market price. If the price cap is set above the equilibrium price, it is considered non-binding and has no immediate effect on the market. Sellers can continue to trade at or below the equilibrium price without breaching the limit imposed. However, a price cap becomes binding and has significant effects on the market when it is set below the equilibrium price. In this case, the price is artificially maintained at a lower level than the market would have naturally determined. | |||

When the price cap is binding, it can lead to several economic consequences. Firstly, it can create a shortage, because at a lower price, demand increases while supply decreases. For example, strict rent controls can lead to a shortage of available housing, as landlords may be less inclined to rent out their properties or invest in new homes. In addition, price ceilings can lead to a decline in the quality of goods and services, as suppliers look for ways to cut costs in the face of reduced profit margins. In addition, poorly designed or applied price ceilings can lead to black markets, where goods or services are sold illegally at prices above the ceiling. This can occur when demand significantly exceeds the supply available at the legal price ceiling. | |||

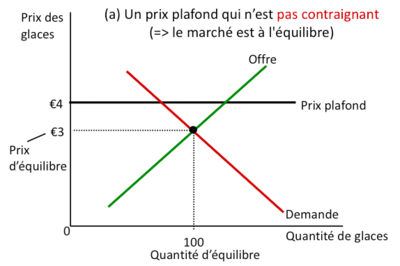

The | The graph below illustrates a market with intervention in the form of a price ceiling. The graph shows two curves: the supply curve (in green) rising towards the right, indicating that the higher the price, the greater the quantity offered; and the demand curve (in red) falling towards the right, indicating that the lower the price, the greater the quantity demanded.The point where these two curves cross is identified as the equilibrium price, which in this case is set at €3, and the equilibrium quantity, which is 100 ice creams. This equilibrium point indicates the price where the quantity of ice cream that sellers wish to sell is exactly equal to the quantity that buyers wish to buy. | ||

Above the equilibrium point, we have a horizontal line marked "Ceiling price" set at €4. This ceiling price is defined above the market equilibrium price. As indicated in the title, it is a ceiling price which is not binding, because it is set at a level above the price at which the market would naturally balance. In other words, since the ceiling price is above the price at which the quantity offered equals the quantity demanded, it does not directly affect the functioning of the market. Transactions can continue at the equilibrium price without being hindered by the price ceiling. In practice, a non-binding price cap such as this has no immediate impact on the market. It is put in place either for political reasons, to show an intention to regulate without disrupting the market, or as a preventive measure to prevent prices from rising higher in the future. However, if market conditions evolve in such a way that the equilibrium price rises above €4, then the price cap would become binding and begin to have associated effects such as shortages or queues. | |||

[[Fichier:Prix plafond 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

The quantity traded at a given price is the smaller of the quantity offered and the quantity demanded. In a market, at a given price, the quantity traded is determined by the smaller of the quantity offered and the quantity demanded. This concept is crucial to understanding how markets work and the effects of interventions such as price caps. When the price of a good or service is at its equilibrium level, the quantity of that good or service that sellers are prepared to sell (quantity offered) corresponds exactly to the quantity that buyers are prepared to buy (quantity demanded). This is known as market equilibrium, where supply and demand are in perfect harmony, and there is no surplus or shortage. | |||

However, when the price is artificially set below the equilibrium level (as in the case of a price ceiling), the situation changes. At this lower price, the quantity demanded by consumers generally increases, as the good or service becomes more affordable. At the same time, the quantity offered by producers falls, as it becomes less profitable for them to produce or sell the good or service. In this case, the quantity traded is equal to the quantity offered, which is smaller than the quantity demanded. This leads to a shortage, as there are more people wanting to buy the product than are available at the set price. Conversely, if the price is artificially set above the equilibrium level (as in the case of a price floor), the quantity demanded decreases while the quantity offered increases, leading to a surplus on the market. | |||

In | In a free market, the quantity traded is determined by the point where supply and demand meet. Any intervention that alters this equilibrium point, such as the introduction of price ceilings or floors, causes an imbalance between the quantity offered and the quantity demanded, leading to shortages or surpluses. | ||

The introduction of a price ceiling, although intended to make a product or service more affordable, can have unexpected and sometimes unfair consequences. When the government sets a price ceiling below the equilibrium market price, the good or service becomes cheaper, which increases demand. However, at this lower price, producers may be less inclined to offer the same level of quantity, creating a shortage. In this situation, there are not enough goods or services available to satisfy everyone who wants to buy at the ceiling price. This imbalance often leads to queues and other forms of rationing, as there are more people than products available. In this context, wealthier consumers may have an advantage, as they may have more means of accessing the limited product or service, for example, by paying for priority access or using their influence. This can lead to a form of discrimination where people on low incomes, although theoretically the beneficiaries of these price ceilings, find themselves excluded from the market. | |||

In addition, inefficient price caps can encourage the development of black markets. In these markets, goods or services are sold illegally at prices above the legal ceiling, which can exacerbate inequalities, as only those who can afford to pay higher prices have access to them. These side-effects of price controls underline the importance of careful design and implementation of public policies. It is essential that policy-makers take account of these potential consequences and explore alternative or complementary mechanisms to achieve their objectives without introducing new inequalities or inefficiencies into the market. | |||

[[Fichier:Prix plafond 2.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

This graph illustrates a market in which a binding price ceiling has been introduced. This graph shows the supply and demand curves, as in the first example, but with a significant difference in the position of the price ceiling. The natural equilibrium price on this market is €3, at which point the quantity offered by producers corresponds to the quantity demanded by consumers. However, the government has introduced a ceiling price of €2, which is lower than the equilibrium price. | |||

The | At this price ceiling level, the quantity of ice cream demanded is greater than the quantity that producers are prepared to offer. This creates a shortage, as shown in the graph, because at €2 there are more consumers willing to buy ice cream than there are producers willing to sell it at that price. The points on the supply curve and the demand curve do not meet, which means that there is a deficit between the quantity of ice cream that consumers want to buy and what is available on the market. | ||

This shortage situation can lead to a number of secondary outcomes, such as long queues for ice cream, as consumers compete for a limited number of available products. In addition, it can encourage unofficial economic activities, such as a black market where ice cream could be sold at a higher price than the legal ceiling. In theory, price ceilings are designed to help consumers by making goods and services more affordable. However, as this graph illustrates, if they are set too low, they can actually disrupt market equilibrium and lead to undesirable effects that undermine market efficiency and can potentially disadvantage the very consumers they are designed to help. For this reason, it is essential that price ceilings are set taking into account the balance between supply and demand to avoid such negative consequences. | |||

== Price ceilings: short vs. long term == | |||

In a long-term context, the price elasticities of supply and demand tend to be higher because of the greater ability of producers and consumers to adjust their behaviour in response to price changes. The price elasticity of demand measures the sensitivity of the quantity demanded to a change in price. If consumers have more time to find substitutes or adapt to a price change, their response will be stronger, which means a higher elasticity. Similarly, the price elasticity of supply indicates the sensitivity of the quantity offered to a change in price. Over time, producers can adjust their production levels in response to changes in market prices. | |||

When a binding price ceiling is in place, producers have little incentive to invest and increase production because the returns on these investments are limited by the price ceiling. If the price is kept below the level that would allow normal profitability, producers may not invest in improving quality or expanding production capacity. In the long term, this can lead to a decline in the quality of goods produced as producers look for ways to cut costs to maintain their economic viability in a price-constrained environment. With less investment in the sector, supply does not adjust to meet increased demand, exacerbating the existing shortage. In a market without price controls, higher prices would act as a signal to attract new producers or encourage existing producers to increase production. But with a price ceiling, this signalling mechanism is altered. | |||

The long-term result of a binding price ceiling is reduced supply, increased scarcity and reduced quality. These consequences can have a negative impact on the general well-being of consumers, particularly those on low incomes, who could be hardest hit by the reduced quality and availability of essential goods and services. This underlines the importance for price control policies to take account of long-term impacts and to seek balances that encourage investment while protecting consumers. | |||

Rent control is a government intervention that seeks to regulate the housing market by setting a legal maximum for rents or limiting annual rent increases. This policy is generally implemented in areas where the cost of housing has risen so significantly that a large proportion of the population is struggling to afford a home. The aim is laudable: to maintain affordability and stability in a sector that is crucial to people's well-being. However, this economic strategy is not without its drawbacks and complexities. When rents are kept below the level that would be set by the free market, this can lead to an inappropriate allocation of resources. Landlords, faced with limited financial returns, may have no incentive to invest in the maintenance or improvement of their properties, which can lead to a gradual deterioration in the quality of the housing stock. In addition, property developers may be reluctant to build new homes if the expected returns do not justify the investment, which hampers the increase in the supply of housing and exacerbates the shortage. | |||

These shortages are not just theoretical hypotheses; they are manifesting themselves in cities all over the world. For example, in New York and San Francisco, two cities well known for their rent control policies, the lack of affordable housing is a persistent problem. Despite intentions to make housing accessible, these cities have struggled with shadow housing markets where rents can far exceed regulated rates, creating a difficult environment for those not protected by rent control regulations. Landlords, faced with a large number of applicants for a limited number of flats, can become extremely selective. This can lead to discriminatory practices, sometimes subtly implemented through stricter rental requirements, which may include more rigorous credit checks or requests for additional financial guarantees. Thus, instead of helping the low-income population, rent control can paradoxically disadvantage them. | |||

To mitigate these negative effects, some jurisdictions have explored complementary policies. For example, the Vienna model of social housing is often cited for its balanced approach. Vienna combines rent control measures with significant investment in social housing, providing a large quantity of affordable housing while maintaining high quality standards. It is clear that rent control, while well intentioned, can have perverse effects which require carefully calibrated policies to ensure that the objectives of affordability and housing quality are achieved without creating undesirable distortions in the market. | |||

== Application: rent control in the short term == | |||

The | The graph below illustrates the impact of rent control on the housing market in the short term, where supply and demand are relatively inelastic. The graph shows typical supply and demand curves: the supply curve is rising, indicating that landlords are prepared to offer more homes at a higher rent, and the demand curve is falling, showing that tenants demand fewer homes as the price rises. | ||

[[Fichier:Impact du contrôle de loyer dans le court terme.png|400px|vignette|centré|Impact of rent control (price ceiling) in the short term (inelastic supply and demand)]] | |||

The "Maximum rent" indicated by a horizontal line represents the ceiling price set by government regulations. This maximum rent is lower than the price that would naturally be established at the intersection of the supply and demand curves, which represents the equilibrium price of the market. | |||

The | In the short term, where the reactivity of landlords and tenants to price changes is limited (i.e. elasticity is low), the quantity of dwellings available does not fall considerably in response to the rent cuts imposed by control. Similarly, the quantity of housing that tenants want does not increase enormously either. However, even with a low elasticity, the maximum rent imposed by control creates a shortage, because at this controlled price, the quantity of dwellings that tenants want exceeds the quantity that landlords are prepared to rent. In reality, this shortage can result in various difficult situations for tenants, such as longer waiting lists for flats, increased competition for available housing, and potentially poorer quality housing, as landlords have no financial incentive to maintain or improve their properties. In addition, the shortage can encourage black market activity where homes are rented at unregulated prices outside the official system. | ||

The experience of several cities around the world shows that the consequences of rent control can be complex and often counter-productive. For example, both Paris and Berlin have experienced challenges with their rent control policies, leading to political and social debates about how best to provide affordable housing without disrupting the market or discouraging investment in housing stock. Ultimately, managing the housing market through rent control in the short term needs to be undertaken with care and complemented by policies that encourage the supply of housing and ensure its quality, so that the goals of affordability and availability are achieved without undesirable side effects. | |||

== Application: rent control in the long term == | |||

This economic graph shows the long-term effects of rent controls on the housing market, with more elastic supply and demand curves. This means that landlords' and tenants' reactions to price changes are more pronounced in the long term than in the short term. | |||

[[Fichier:Impact du contrôle de loyer dans le long terme.png|400px|vignette|centré|Impact of rent control (price ceiling) in the long term (elastic supply and demand)]] | |||

The "Maximum Rent" is indicated by a horizontal line below the point where the supply and demand curves would naturally cross, i.e. below the equilibrium market price. The horizontal distance between the supply and demand curves at the level of the maximum rent represents the housing shortage. The text "In the long term, the shortage worsens" emphasises that, over an extended period, market players have time to react fully to the constraint imposed by the maximum rent. Tenants seek to find more homes at this attractive rent, which increases the quantity demanded, while landlords are discouraged from offering rent-controlled homes, which reduces supply. This dynamic leads to an increased shortage in relation to the short term. Landlords may choose not to invest in new homes or maintain existing ones because the financial returns do not justify the costs. Tenants, on the other hand, are encouraged to consume more space than they need because the price is lower than what they would be prepared to pay in an unregulated market. | |||

Real-life examples of this phenomenon include cities such as San Francisco and New York, both of which have highly regulated housing markets and where the challenges of finding affordable housing are well documented. Long-term price caps in these cities have contributed to very tight housing markets, with long waiting lists for regulated flats and an insufficient number of new homes being built to meet growing demand. This highlights the importance of considering the long-term impacts of rent control policies. While these policies may be designed to help tenants, without accompanying measures to stimulate supply, they can end up exacerbating the very problems they are designed to solve. Well-designed policies must therefore strike a balance between protecting tenants and encouraging investment in the housing stock to ensure a sufficient supply of quality housing. | |||

== Winners and losers from rent caps == | |||

Rent capping, like any intervention in the market, creates winners and losers because of its varied impacts on different economic players. | |||

The winners from rent caps are typically those who already have an existing lease in a property where the rent is capped. These tenants benefit from rents that are lower than what might be charged on an open market, which can save them money or allow them to live in neighbourhoods where they could not otherwise afford to reside. In addition, new tenants who are lucky enough to find rent-capped accommodation also benefit from these regulated rents, which can help them stabilise their housing costs. However, the losers of this policy are often more numerous or suffer more significant losses. Landlords, faced with restrictions on the amount of rent they can legally charge, receive reduced income from their property investments. This reduction in income can discourage them from investing in the maintenance and improvement of their properties, or worse, cause them to withdraw from the rental market altogether, thereby reducing the overall supply of housing. | |||

In addition, individuals looking for a home who are unable to find one are also losers in this system. The shortage created by rent caps means that there are fewer homes available than there would be in a market without price controls. These individuals may find themselves paying much more for unregulated housing or enduring precarious living conditions, sometimes even having to leave the areas where they work or study for lack of affordable housing. It is also important to recognise that rent caps can have secondary impacts on communities. For example, it can lead to economic segregation, where only those with rent-controlled accommodation can afford to live in certain neighbourhoods, while newcomers have to look elsewhere, often in less desirable or more remote areas. | |||

The challenge with rent capping is to strike a balance that protects tenants without discouraging the supply of quality housing or creating wider inequalities within society. To achieve this balance, it is essential that rent caps are accompanied by policies that encourage investment in the housing stock and support the construction of new homes. | |||

Rent caps, as a housing policy measure, raise important questions of fairness. The aim is often to protect tenants from sudden and excessive rent rises and to ensure that housing remains affordable for all. However, the beneficiaries of these measures are not always those who need them most, which can lead to inequalities and distortions in the housing market. | |||

In cities such as Geneva, where the property market is particularly tight and rents high, reported cases of politicians or people on relatively high incomes benefiting from moderate rents as a result of the cap can seem particularly unfair. This can undermine confidence in the regulatory system and raise concerns about its effectiveness and fairness. The problem of fairness is exacerbated by the fact that the benefit of a rent cap is often linked to the length of the tenancy. Long-standing tenants, who signed their leases when rents were lower, benefit from rents well below current market rates. This creates an advantage for older residents or those long established in the area, while younger tenants, newly formed families, students and migrants face a much more expensive and competitive market. These latter groups are often forced to pay significantly higher rents for similar accommodation, simply because they enter the market at a time when rents are at their peak. | |||

To address these imbalances, some jurisdictions have implemented social housing programmes that specifically target low-income families, young people and newcomers, ensuring that low-rent housing is allocated on the basis of need rather than seniority. Others have adopted measures that allow some flexibility in rent controls, such as exemptions for new buildings, to encourage the construction of new homes. It is essential that housing policies, including rent controls, are designed and implemented in a way that promotes equity and meets the needs of different segments of the population. This requires ongoing analysis and policy adjustments to ensure that the objectives of affordability and social justice are met. | |||

== Consequences/costs of rent control == | |||

Although the aim of rent controls is to increase the affordability of housing, they can have significant consequences and costs for society. In a context of scarcity induced by these controls, the housing market is transformed into a sellers' market, where landlords and housing providers have disproportionate power over excess demand. Here is a closer look at these effects: | |||

* Rationing of demand: When there are more applicants than available rent-controlled housing, landlords can afford to be selective, which often leads to rationing. Waiting lists get longer, and it is not uncommon for homes to be allocated not to those who need them most, but to those with connections, recommendations or who match a preferred profile defined by the landlord. This can also fuel discrimination, whether on the basis of income, ethnicity, age or other factors, thereby reducing the fairness and efficiency of the housing market. | |||

* Increased demands from suppliers: In a rationed housing market, landlords may impose stricter conditions on the selection of tenants. This may include requiring larger bank guarantees or deposits, proof of solvency or employment, and sometimes even months' rent paid in advance. Such requirements can create insurmountable barriers for tenants on low incomes or those without access to solid financial guarantees, reinforcing inequality and limiting access to housing for these groups. | |||

Landlords may also favour a 'posh clientele', i.e. tenants who are perceived as less likely to cause problems or who can offer stronger financial guarantees. This can lead to a socio-economic homogenisation of neighbourhoods, with consequences for diversity and social cohesion. The social costs of these dynamics can be significant. They can reinforce social divisions and limit mobility, both geographical and social. In addition, the effort and costs associated with finding a home in such an environment can be substantial, with a negative impact on the well-being of individuals and families. To alleviate these problems, housing policies could include fairer and more transparent matching mechanisms, targeted housing subsidies, and investment in the construction of affordable housing to increase supply. Such measures could help to rebalance the market and reduce the inequalities created or exacerbated by rent control. | |||

The development of a black market is one of the often overlooked consequences of rent control. This phenomenon can take several forms, but one of the most common is abusive subletting. In a context where rents are capped at a level below that of the open market, demand for affordable housing far exceeds supply. Tenants with rent-controlled leases may be tempted to sublet their flats for more than they are paying, thereby making an unauthorised profit. This practice may sometimes be justified by tenants as a way of offsetting other costs or earning extra income, but it can lead to situations where subtenants pay far more than the officially controlled rent, thereby defeating the original purpose of regulation. Subtenants find themselves in a precarious position: they often pay high rents, do not have the same legal rights as official tenants and can be evicted more easily. | |||

Black markets can also reduce the transparency and fairness of the housing market. They make it difficult for the authorities to monitor and regulate the market, and they create unequal conditions for tenants who are legitimately seeking accommodation. It can also lead to inefficient allocation of housing, where flats are not necessarily occupied by those who need them most or are most able to pay the regulated rate. To counter the formation of a black market, stricter regulation and control measures are often necessary. This can include penalties for abusive subletting, better enforcement of existing regulations and awareness campaigns to inform tenants and landlords about the risks and penalties associated with participating in a black market. At the same time, increasing the supply of affordable housing and ensuring fair access to housing for all segments of the population can reduce the incentive to create and participate in unofficial housing markets. | |||

Rent controls, although designed to protect tenants from rent rises and ensure affordable housing, can lead to numerous economic inefficiencies and losses for the community. One notable consequence is the discouragement of residential mobility. Tenants who benefit from a moderate rent in a controlled market may be reluctant to move, even if a change of accommodation would make sense for them because of a professional transfer, a change in the size of their family, or other changes in their personal circumstances. This can lead to under-utilisation of available housing, where people stay in flats that no longer meet their needs simply because the cost of moving would be too high compared to the favourable rent they currently pay. Secondly, rent controls can act as a brake on investment in the construction and renovation of new homes. Investors, faced with a potentially limited return on investment due to rent caps, may choose to put their money into other areas where returns are higher and less regulated. This can reduce the number of new builds and renovations, exacerbating the housing shortage problem and undermining the overall quality of the housing stock. | |||

The misallocation of resources is another major inefficiency. Low-rent flats can often be occupied by older individuals or couples whose children have left home, leaving large areas underused. At the same time, growing families may find themselves cramped into homes that are too small because that's all they can afford on the open market, where prices reflect the shortage created by controls. This inadequate distribution of housing does not reflect the real needs of the population and can lead to situations where the available space is not used in the most efficient way. To resolve these inefficiencies, it is necessary to develop housing policies that are not limited to rent controls but also include measures to stimulate supply, such as tax incentives for construction and renovation, as well as targeted housing subsidies that directly support low-income households. In addition, policies that allow a degree of flexibility in rent controls can encourage mobility and better use of resources, for example by allowing rent adjustments when tenants change or by revising rent controls according to the size of the dwelling and the number of occupants. | |||

== Controlled rents: efficiency and imperfect competition == | |||

Market efficiency and the assumptions underlying models of perfect competition often do not apply to the housing market. In fact, the housing market is subject to many imperfections that may justify state intervention, such as rent control. | |||

Firstly, housing as a service is extremely heterogeneous, with characteristics that vary widely from one property to another, even within the same neighbourhood. Differences can include size, quality, age of the building, nearby services, transport connectivity and other subjective factors such as the charm of a place or its history. This heterogeneity means that each housing unit is almost a market in itself, making comparisons and generalisations difficult. In addition, the costs of prospecting and searching are significant. Finding suitable accommodation often requires considerable research, and perfect information is virtually impossible to obtain. Potential tenants have to invest time and money to find a property that meets their needs, and even then they don't always have all the information they need to make an informed choice. This can include rental price history, potential problems with the property or neighbourhood, and the landlord's future intentions. Finally, the housing market can be considered 'thin', meaning that there are relatively few providers, particularly in smaller regions or cantons. This can give existing housing authorities and developers considerable market power, allowing them to set higher prices than they would in a more competitive market. In some cases, this can even lead to cartel behaviour, where suppliers agree on prices or conditions, further limiting competition. | |||

These market imperfections can sometimes justify interventions such as rent controls to protect tenants' interests and ensure access to housing. However, such interventions must be carefully designed to avoid creating additional inefficiencies and must be accompanied by other measures to increase supply and improve market transparency. For example, policies that increase the number of dwellings available or support the entry of new players into the market can help to reduce the market power of existing large players and improve the overall efficiency of the housing market. | |||

In a housing market characterised by imperfect competition, rent controls can be seen as an instrument to correct certain inefficiencies and inequities. The argument in favour of rent controls, in this case, is based on the idea that the market power held by a limited number of property owners or developers can lead to higher prices than those resulting from pure and perfect competition. By limiting the ability of these players to set rents freely, rent controls can help to keep prices at a more reasonable level, which could potentially improve the accessibility and efficiency of the market. Beyond efficiency, rent controls are often justified on grounds of social equity. In many societies, it is considered fair and necessary to ensure that all citizens, regardless of income, have access to decent and affordable housing. Rent control can be seen as a means of social redistribution, helping to protect low-income households from market fluctuations and the burden of potentially unsustainable rents. In practice, this means that rents are kept at a level where low-income tenants are less likely to spend a disproportionate share of their budget on housing. | |||

However, it should be noted that for rent control to achieve the objectives of efficiency and fairness, it must be designed and implemented in such a way as to avoid the pitfalls mentioned above, such as housing shortages, deterioration in the quality of the housing stock, and discrimination in housing allocation. This could include measures such as targeting rent controls at the segments of the population that need them most, putting in place policies to incentivise the construction of new housing, and regulating to ensure that rent-controlled housing meets decent quality standards. To balance these considerations, housing policies can include a variety of tools, such as rent supplements for low-income tenants, tax credits for landlords who maintain and improve rental housing, and programmes to encourage the construction of affordable housing. By combining rent control with these other measures, it is possible to tackle the problems of equity and efficiency in a more comprehensive and effective way. | |||

== Price floor == | |||

The concept of a floor price, or minimum price, is the antithesis of a ceiling price in economic regulation. It is an intervention where the government or a regulatory authority establishes a legal minimum price for a good or service, below which transactions are not permitted. This measure is often put in place to protect the interests of producers or service providers by ensuring that the market price does not fall below a certain level, which could otherwise threaten their ability to cover production costs or maintain acceptable living standards. A common example of a price floor is the minimum wage in the labour market. The government sets the minimum wage to prevent workers from being underpaid and to ensure that they receive a fair wage that allows them to meet their basic needs. | |||

However, just as a ceiling price must be above the equilibrium price to be binding, a floor price must be set above the equilibrium price to have a real effect on the market. If the floor price is set below the equilibrium price, where the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity offered, it will have no immediate impact on market transactions since the natural market price is already higher than the floor. When the price floor is binding (i.e. set above the equilibrium price), it can lead to oversupply: more goods or services will be offered on the market than consumers are prepared to buy at that price. This can lead to surpluses, such as unsold stocks or, in the case of the labour market, unemployment. | |||

Floor prices should therefore be used with caution and in the context of a thorough analysis of their potential effects. They can play an important role in income protection and the fight against poverty, but when they are badly adjusted, they can also cause undesirable market distortions. | |||

[[Fichier:Prix plancher 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

This graph illustrates the impact of a minimum wage on the labour market. It shows two intersecting curves: the rising labour supply curve, which represents individuals wanting to work, and the falling labour demand curve, which represents companies looking to hire. | |||

The minimum wage is indicated by a horizontal line running across the graph above the point where the supply and demand curves intersect. This minimum wage level is an example of a price floor. If this minimum wage is higher than the market equilibrium wage (the point where the two curves naturally cross), this means that it is binding. Excess labour, or unemployment, is represented by the horizontal gap between the quantity of labour offered and the quantity demanded at this minimum wage level. At a binding minimum wage, companies are only prepared to hire a smaller quantity of labour than individuals are prepared to offer at that wage. This creates a labour surplus, i.e. unemployment. | |||

Analysis of this graph suggests that, although the minimum wage is designed to guarantee workers a decent income, it can also have the undesirable effect of creating unemployment, especially if the minimum wage is set without taking into account the specific situation of the labour market or productivity levels. Indeed, if the cost of labour becomes too high in relation to the value produced by that labour, companies may cut back on hiring, automate certain functions or relocate jobs to regions where costs are lower. In reality, the impact of a minimum wage on employment is the subject of lively debate among economists. Some argue that increases in the minimum wage can have little effect on employment, or can even stimulate the economy by increasing workers' purchasing power. Others stress the negative effects, particularly in sectors where labour is a significant cost and margins are low. | |||

The effectiveness of a minimum wage as a policy therefore depends on many factors, such as the level of economic development, the structure of the labour market, and the flexibility of employers and employees. In some cases, additional measures may be needed to minimise the negative impact on employment, such as training to increase worker productivity or targeted aid for particularly hard-hit industries. | |||

== Minimum wage and unemployment == | |||

The elasticity of demand for labour is a measure of how responsive employers are to changes in the cost of labour. If the demand for labour is elastic, this means that even a small increase in the minimum wage can lead to a significant reduction in the number of jobs that employers are prepared to offer. This is particularly true in sectors where companies operate in highly competitive markets with fixed prices, where they cannot easily pass on additional costs to consumers without losing market share. | |||

Low-skilled, labour-intensive sectors are often characterised by such competition. In these sectors, profit margins are generally low, and products or services are often standardised, which prevents companies from raising prices without risking losing customers to competitors. When the minimum wage is increased, businesses in these sectors may not be able to absorb the extra costs and may respond by reducing the number of hours offered or employing fewer workers. This can lead to a situation where the minimum wage causes increased unemployment, particularly among low-skilled workers, who are often least able to find other forms of employment due to their lack of specialist skills or advanced training. Increased unemployment among these workers can have profound social and economic consequences, such as increased poverty and reduced social mobility. | |||

However, it is important to note that the link between the minimum wage and unemployment is not unequivocal. Some economists argue that increases in the minimum wage can stimulate aggregate demand by increasing the purchasing power of low-income workers, which in turn can stimulate employment and offset the effects of labour demand elasticity. Others suggest that moderate increases in the minimum wage can be absorbed by firms through productivity gains or a small increase in prices. It is therefore essential that policy decisions on the minimum wage take into account the specificities of the labour market and the economic conditions of each sector and region, and that they are accompanied by complementary policies, such as vocational training and education, to help low-skilled workers adapt to changes in the labour market. | |||

Assessing the social impact and income redistribution associated with the introduction of a minimum wage is a complex issue that involves weighing the benefits against the potential drawbacks. | |||

Benefits of a minimum wage: | |||

* Increasing incomes: For workers who remain in employment, the minimum wage guarantees a basic income, which can help lift them out of poverty and improve their quality of life. | |||

* Reducing inequality: By increasing the wages of low-income workers, the minimum wage can help reduce the income gap between low- and high-skilled workers. | |||

* Stimulating aggregate demand: Low-income workers tend to spend a greater proportion of their income. Thus, increasing their wages can stimulate demand for goods and services, which can have a positive effect on the economy. | |||

Disadvantages of the minimum wage: | |||

* Job loss: For workers who lose their jobs as a result of the extra costs that employers have to bear, the consequences can be devastating, leading to financial hardship and increased reliance on welfare benefits. | |||

* Barrier to entry into the labour market: Young workers and entrants to the labour market may find it more difficult to get a first job if employers are reluctant to hire at a higher minimum wage. | |||

* Costs to small businesses: Small businesses, particularly those with low profit margins, may be particularly affected by the introduction of a minimum wage, which may lead them to reduce their workforce or, in extreme cases, close down. | |||

To assess the net impact of the minimum wage policy, it is necessary to look at the proportion of workers who benefit from a pay rise compared to those who suffer a job loss or a reduction in working hours. This also means taking account of indirect costs, such as the impact on the prices of goods and services or changes in employers' hiring behaviour. The overall impact of minimum wages on income redistribution will depend on the economic and social structure of each country or region. In some cases, the benefits may outweigh the costs, especially if the minimum wage is complemented by other support measures such as vocational training, tax credits for low-income workers, and housing assistance programmes. A full assessment therefore requires not only an analysis of the economic data, but also consideration of the wider social consequences and society's values of equity and social justice. | |||

In a competitive labour market, where many employers compete to hire workers, the introduction of a minimum wage can, according to the standard model, lead to an imbalance between labour supply and demand and potentially increase unemployment. However, if the labour market is far from perfectly competitive and is more akin to a monopsony - a situation where there is a single employer or a small number of employers who dominate the labour market - the impact of the minimum wage can be very different. In a monopsony, the employer has the power to set wages lower than would prevail in a competitive market because of the lack of competition for workers. Workers, having few or no alternative options, are forced to accept lower wages. | |||

In this context, the introduction of a minimum wage could actually increase employment rather than reduce it. By setting a minimum wage, the government can force the monopolist to pay higher wages, which can bring the wage closer to the competitive level and encourage increased labour supply. Paradoxically, this can lead the monopsony operator to hire more workers because the minimum wage removes the advantage the employer had in hiring fewer workers at a wage below the competitive rate. Monopsony models are more complex and involve different assumptions from those of a perfectly competitive labour market. They require a nuanced understanding of market dynamics and how wages are set and negotiated. These models are studied in more advanced labour economics courses, where students learn to analyse labour markets in less idealised contexts and to grasp the political implications of these less standard situations. | |||

The notion of the minimum wage runs through economic and social history as a mechanism for protecting workers against exploitation and precariousness. The earliest incarnations of wage controls can be traced back to sixteenth-century Britain, where specific towns introduced wage thresholds to curb employer abuse and guarantee a subsistence income for workers. These ad hoc measures reflected the social concerns of the time and marked an early recognition of the need to regulate employment relations. | |||

At the end of the nineteenth century, as the world entered an era of rapid industrialisation, the issue of workers' pay became increasingly important. In New Zealand in 1894, and shortly afterwards in Australia, national minimum wage laws were introduced, setting legislative precedents that formally recognised the need for an income floor for workers. These policies were a response to the challenges posed by industrialisation, such as the rapid growth of cities, urbanisation, and the often difficult working conditions that ensued. | |||

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the United Kingdom followed suit by introducing its own minimum wage legislation in 1909, targeting in particular sectors where insecurity and low pay were commonplace. This legislation marked a turning point in the way the government perceived its role in protecting the economic well-being of workers. | |||

In the United States, the situation was evolving in a similar way. Although minimum wage measures had been introduced in some states as early as 1912, it was not until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 that a federal minimum wage was established, before being extended in 1966 to include the majority of workers. This extension was in recognition of the fact that regulating workers' incomes was a national issue, transcending state borders. | |||

In contrast to these examples, Switzerland is notable for not having a statutory minimum wage at national level. However, this does not mean that the issue of workers' pay is left to chance. Through collective agreements, minimum wages are negotiated between unions and employers, demonstrating a robust model of social dialogue. The 2012 popular initiative in Switzerland, which called for the introduction of a minimum wage of CHF 22 per hour, bears witness to the desire of certain social players to codify these protections in law, although the initiative was ultimately unsuccessful. | |||

The historical and contemporary examples of the minimum wage reveal that, although the contexts and mechanisms may vary, the underlying principle remains constant: the need to ensure that workers receive a wage that allows them to live in dignity. Over the centuries, governments and societies have sought ways to balance market forces with social protection, striving to adapt minimum wage policies to the economic realities and values of their time. | |||

The debate on the link between minimum wages and employment is one of the oldest and most persistent in labour economics. Economists have studied this question for a long time, but despite decades of research and analysis, there is still no clear empirical consensus. Studies produce divergent results, often due to differences in methodologies, time periods and locations studied, as well as the economic sectors concerned. On the one hand, some economists rely on the standard theoretical model of microeconomics, which predicts that an increase in the minimum wage above the market equilibrium level will reduce the demand for labour, leading to higher unemployment, particularly among low-skilled workers. They argue that employers will seek to cut costs by replacing labour with machines, relocating production, or simply hiring fewer workers. | |||

However, other economists point to empirical studies which suggest that the effects of the minimum wage on employment are minimal or non-existent. These studies suggest that employers can absorb the additional costs of the minimum wage by increasing productivity, reducing staff turnover, slightly raising prices, or by slightly reducing profits. In addition, a higher minimum wage can stimulate aggregate demand by increasing the purchasing power of low-income workers. Differences in empirical results can also be attributed to the unique characteristics of each labour market. For example, in markets with a high demand for labour or in sectors where wages are already high, the impact of an increase in the minimum wage could be negligible. Conversely, in markets where labour is less in demand or in sectors that are highly cost-sensitive, such as fast food or retail, the impact could be more significant. | |||

Finally, it should be noted that the effects of the minimum wage may vary not only between different regions and sectors, but also over time. Changing economic conditions, evolving technologies, demographic trends, and complementary government policies can all influence how changes in the minimum wage affect employment. Because of this complexity and diversity of outcomes, the debate on minimum wages and employment remains open, with valid arguments on both sides. Policymakers often have to navigate between these different points of view, seeking to find a balance that maximises social benefits while minimising potential negative effects on employment. | |||

= Taxation = | |||

== The State's financial resources == | |||

To finance its many functions, the State does not rely solely on tax revenues or borrowing. It can also generate substantial income from the management and sale of its various assets. Historically and in today's context, the sale of public property represents a significant source of revenue for governments. Parcels of land, administrative buildings, sports or cultural facilities, even ports or airports, can be sold to the private sector. Such transfers are not trivial and must be carefully considered to ensure that they are beneficial to the community in the long term. For example, the sale of the UK's Royal Mail in 2013 was controversial, not least because of questions about the valuation of the business and the impact on the public service. | |||

Tolls are another historic method of state funding. Notable examples include road tolls, such as those on the M6 motorway in the UK or the A1 motorway in France, which generate revenue for the maintenance and improvement of transport infrastructure. Similarly, rights of way on certain bridges or tunnels, such as the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, contribute to the management and preservation of these iconic infrastructures. | |||

Privatisation has been a major trend in recent decades, influenced by political and economic trends favouring the role of the market. Governments have sold off parts or all of public companies, as illustrated by the wave of privatisations in the 1980s under the Thatcher government in the UK, which saw the sale of companies such as British Telecom and British Gas. The aim of these privatisations was to reduce public debt, inject private sector efficiency into these companies and diversify the ownership of economic assets. | |||

In addition, the state can grant concessions or licences to exploit services or resources. These range from broadcasting licences for television and radio stations to mining or oil concessions, which have been a mainstay of state financing in resource-rich countries. Norway, for example, used the revenue from its oil concessions to set up a sovereign wealth fund, now one of the largest in the world, guaranteeing long-term benefits for the population. | |||

All these methods of state financing have their advantages and disadvantages, and the choice depends on many factors, including the political philosophy of the government in power, the state of the economy and the specific needs of society at a given time. The sale of assets can provide immediate financial relief, but can also raise concerns about the loss of control over assets previously held collectively. Tolls and concessions generate recurrent income, but can also be perceived as additional taxes by users. Privatisation can lead to increased efficiency and market-led innovation, but it can also lead to a reduction in the quality of services if profitability becomes the main concern of the new private owners. Ultimately, the management of public finances and the choice of financing methods remain a complex task that must be approached with careful attention to both short- and long-term consequences. | |||

The state's main source of funding comes from its power to levy taxes on individuals and businesses. This power of fiscal coercion is a fundamental attribute of state sovereignty, enabling it to mobilise the resources needed to provide public goods and services, maintain order and security, and carry out infrastructure projects. Taxes take many forms, including but not limited to: | |||

# Income taxes: These are levied on individuals and companies. Personal income tax is often progressive, meaning that the rate of tax increases with the level of income. For companies, corporation tax is calculated on profits. | |||

# Consumption taxes: Value added tax (VAT) or sales tax is applied to goods and services. This tax is regressive, as it takes a larger proportion of the income of low-income households. # Property taxes: These are levied on real estate and are an important source of revenue for local governments. | |||

# Customs duties: Levied on imported goods, they have a dual function: to generate revenue and to protect domestic industries from foreign competition. | |||

# Social contributions: Intended to finance social security systems, these contributions are often levied on employees' wages and employers. | |||

Governments may also levy charges for the use of natural resources (such as oil, gas and minerals) or for issuing licences and permits in certain regulated areas (such as broadcasting or fishing). Taxes are essential not only for financing public expenditure but also for implementing economic and social policies. For example, taxes can be used to redistribute wealth, encourage or discourage certain economic behaviour, and stabilise the economy. However, the introduction of these levies must be carefully managed so as not to stifle economic activity or unfairly increase the burden on certain sections of the population. | |||

Historically, the evolution of tax systems has reflected changes in the balance between the State's financing needs and society's ability to pay. For example, the tax reform in the United States in 1913, which introduced the federal income tax, represented a major change in tax policy, recognising the need for a more stable and equitable source of revenue to fund growing government activities. From a contemporary perspective, the design and administration of tax systems are major governance issues, with a delicate balance to be maintained between economic efficiency, social equity and political acceptability. | |||

In addition to taxes, the state finances its activities by other means, including borrowing and transfers, each with its own dynamics and implications. | |||

# Government borrowing: Governments borrow money to finance expenditure that exceeds their tax revenues. This debt is often incurred by issuing government bonds, which are financial instruments that promise to repay the amount borrowed with interest at a specified future date. These bonds can be purchased by individuals, companies, banks and even other countries. Borrowing has a number of advantages, including the ability to finance major infrastructure projects, stimulate the economy in times of slowdown, and meet urgent needs without immediately raising taxes. However, excessive debt can lead to long-term problems, particularly in terms of interest charges and fiscal sustainability. | |||

# Transfers: Transfers are another source of funding for government activity. They can take the form of financial aid from other states or international organisations, such as grants, donations or development aid. Transfers can also come from intergovernmental funds within the same country, where the central government redistributes resources to local or regional governments. This form of funding is particularly important for regions or countries that do not have sufficient resources of their own to finance their activities, or for developing countries that may be dependent on foreign aid for their development projects. | |||

Over-dependence on borrowing can lead to unsustainable debt, while dependence on transfers can compromise political and economic autonomy. For example, the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone has highlighted the challenges associated with high public debt, where countries such as Greece have had to implement severe austerity measures in response to conditions imposed by international creditors. | |||

Both of these forms of financing underline the need for governments to maintain a careful balance between different sources of revenue. A judicious mix of taxes, borrowing and transfers can provide the flexibility to meet public needs without compromising the long-term financial health of the state. | |||

== Taxes == | |||

Tax is the main source of revenue for most countries and is characterised by the fact that it is levied without any direct consideration. This means that, unlike specific services or goods purchased by a consumer, taxpayers do not receive a specific service or good in exchange for the tax they pay. | |||

Taxes are used to fund a wide range of public services and state functions that benefit society as a whole, rather than specific individuals. These include: | |||

* Public Services and Infrastructure: Taxes fund essential services such as public health, education, security (police and military), infrastructure maintenance (roads, bridges, water and electricity systems), and social services. * Redistribution of Wealth: Taxes also enable wealth to be redistributed within society, notably through social security programmes, unemployment benefits, retirement pensions, and aid for people on low incomes or with disabilities. | |||

* Economic Stability and Growth: Tax revenues help the State to invest in key sectors to stimulate economic growth and to intervene in the event of economic fluctuations, for example by increasing spending in times of recession to support demand. Investment in the Future: Taxes also fund research and development projects, environmental initiatives and educational programmes, which are essential for the long-term development of a society. | |||

The absence of direct consideration for taxes is what distinguishes them from tariffs or charges, where payments are directly linked to the provision of a specific service or good. For example, road tolls or university tuition fees are payments for specific services, whereas taxes are collected for the common good and benefit society as a whole. | |||

However, the nature of taxation without direct compensation raises challenges in terms of perception and acceptability. Citizens and businesses may be reluctant to pay taxes if they do not receive direct benefits or if they feel that the funds are not used efficiently. This makes transparency, accountability and efficiency in the management of tax revenues crucial to maintaining public confidence and the legitimacy of the state. | |||

The distinction between direct and indirect taxes is a key element of modern taxation, reflecting different methods of raising tax revenue. | |||

# Direct taxes: These are tax levies that depend on the financial situation of the individual or entity (natural or legal person). Direct taxes are generally progressive, which means that the tax rate increases with the taxpayer's ability to pay. Here are some examples of direct taxes: | |||

#* Income tax: levied directly on the income of individuals or companies. For individuals, this tax may take into account various factors such as total income, family situation and allowable deductions. | |||

#* Corporation tax: Taxed on company profits. | |||

#* Property tax: Based on the value of property owned. Direct taxes are often seen as fairer because they are adjusted according to people's ability to pay. However, they can also be more complex to administer and collect. | |||

# Indirect taxes: These taxes are levied on market transactions and do not depend on the individual characteristics of the person paying the tax, which makes them more anonymous. Indirect taxes are generally regressive, as they take a larger proportion of the income of low-income households. Examples of indirect taxes include: | |||

#* Value added tax (VAT) or sales tax: Applied to the majority of goods and services. | |||

#* Excise duties: Imposed on certain specific products such as alcohol, tobacco, and fuel. | |||

#* Customs duties: Levied on imported goods. Indirect taxes are generally easier to collect and less likely to be avoided than direct taxes. However, they can fall disproportionately on low-income consumers, as these taxes are applied uniformly regardless of income. | |||

In practice, most tax systems use a combination of direct and indirect taxes to finance public spending. This combination aims to balance the objectives of efficient revenue collection, tax fairness and economic stability. | |||

Taxation can be divided into two broad categories depending on how it is calculated and collected: ad valorem and unitary (or specific). Each of these methods has its own characteristics and applications. | |||

# Ad Valorem taxation: In this type of taxation, the amount of tax is proportional to the value of the good or service being taxed. The tax rate is expressed as a percentage, and the taxable base is the monetary value of the item being taxed. | |||

#* Example of VAT: Value Added Tax (VAT) is a typical example of an ad valorem tax. VAT is calculated as a percentage of the value of the goods or services sold. For example, if a product costs 100 euros and VAT is 20%, the consumer will pay 120 euros (100 euros + 20% VAT). Ad valorem taxes are widely used because they are flexible and adapt to the value of transactions. They are also relatively easy for taxpayers to administer and understand. | |||

# Unitary (or Specific) Taxation: With this method, the amount of tax is fixed per physical unit of property taxed, regardless of its value. The rate is therefore expressed in monetary units per physical unit (e.g. per litre, per kilogramme, etc.) | |||

#* Example of petrol tax: A classic example is petrol tax. If the tax is 73 cents per litre of unleaded petrol, this means that for each litre sold, 73 cents will be added to the price, irrespective of the basic price of the petrol. Unit taxes are often used for products where it is more appropriate to tax quantity rather than value, as in the case of tobacco products, alcohol or fuels. These taxes may have specific objectives, such as discouraging the consumption of products that are harmful to health or the environment. | |||

Each of these methods has its advantages and disadvantages. Ad valorem taxes adjust automatically to price fluctuations and can be fairer in terms of ability to pay. Unit taxes, on the other hand, are simple to calculate and collect, and can be more effective in achieving certain policy objectives, such as reducing consumption of certain products. The choice between these methods depends on the specific tax policy objectives and the nature of the goods and services concerned. | |||

Value Added Tax (VAT) is a major source of tax revenue for many governments, including the Swiss Confederation. The fact that VAT receipts account for a substantial proportion of the Confederation's resources underlines its importance in the country's tax structure. | |||

In Switzerland, VAT is levied at different rates depending on the nature of the goods and services: | |||

* Standard rate of 8%: This rate applies to the majority of goods and services. It is a relatively moderate rate compared with those applied in other European countries, where the VAT rate can exceed 20%. The standard rate is designed to cover a wide range of products and services, providing a significant and regular source of tax revenue for the government. | |||

* 2.5% reduced rate for food, sport and culture: This reduced rate is applied to goods and services considered essential or beneficial to society. The aim of this reduced rate is to make these goods and services more accessible to the population as a whole, in recognition of their importance to people's daily well-being. Food, for example, is taxed at this reduced rate to ease the financial burden on consumers, particularly low-income households. | |||

The structure of VAT in Switzerland reflects a balance between the need to generate revenue for the state and the desire to maintain the affordability of essential goods. This stratified approach, with different VAT rates, is a common feature of VAT systems in many countries, allowing flexibility in the pursuit of fiscal and social objectives. | |||

The significant reliance on VAT for government revenues also demonstrates the robustness of consumption as a tax base. However, it also underlines the importance of an efficient tax administration to collect this revenue and of a balanced tax policy to ensure that the tax burden is not excessively borne by consumption, especially by the most vulnerable sections of society. | |||

== Indirect taxation == | |||

Indirect taxes reduce incentives to produce and consume, because the price paid by the consumer increases and the price received by the producer falls. The difference between the two is the amount of tax that is collected by the government (<math>p^d - p^s = t</math>). | |||

Indirect taxes, such as value added tax (VAT) or excise duties, have an impact on incentives to produce and consume by altering the prices paid by consumers and received by producers. When a tax is imposed on a good or service, the price paid by the consumer (noted <math>p^d</math> in the equation) increases, while the price received by the producer (noted <math>p^s</math> in the equation) decreases. The difference between these two prices is the amount of tax (<math>t</math>), which is collected by the government. | |||

For the consumer, the tax increases the cost of purchase, which may reduce demand for the good or service. For the producer, the tax reduces the income he receives from the sale, which may reduce the incentive to produce or offer the good or service. This can lead to a loss of economic efficiency, as the tax creates a gap between the price consumers are prepared to pay and the price producers are prepared to accept. This loss of efficiency is often represented graphically in economic models by a loss of surplus, which is the combined loss of consumer and producer surplus due to the tax. In theory, this loss represents a reduction in the overall efficiency of the market: fewer transactions occur than in the absence of the tax, and resources are not used as efficiently as possible. | |||

However, it is important to note that indirect taxes are a key tool for governments to generate the revenue needed to fund public services and infrastructure. Furthermore, in some cases, indirect taxes can be used for specific policy objectives, such as discouraging the consumption of products that are harmful to health (such as tobacco and alcohol) or the environment (such as fossil fuels). So while indirect taxes can reduce incentives to produce and consume, potentially reducing economic efficiency, they can also be justified by wider public policy considerations. | |||

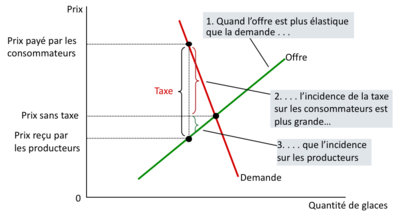

When a good is taxed, the impact of that tax on the market depends on the price elasticity of supply and demand. Price elasticity measures the sensitivity of quantities offered or demanded to a change in price. This sensitivity plays a key role in determining how the tax burden is distributed between consumers and producers. | |||

# Reduction in quantities traded: The introduction of a tax on a good or service generally increases the price that consumers have to pay and reduces the price that producers receive, leading to a reduction in the quantities traded on the market compared with an equilibrium situation without tax. This results in a loss of surplus for consumers and producers, and a reduction in the overall efficiency of the market. | |||