« 美国(重建):1877 - 1900年 » : différence entre les versions

(→快速定殖) |

|||

| Ligne 78 : | Ligne 78 : | ||

[[Fichier:US map-West.png|thumb|密西西比河以外的美国西部。深红色为仍被视为其一部分的州: 加利福尼亚州、俄勒冈州、华盛顿州、内华达州、爱达荷州、亚利桑那州、新墨西哥州、犹他州、科罗拉多州、怀俄明州、蒙大拿州以及阿拉斯加州和夏威夷州。红色阴影部分是有时被认为属于南部或中西部的州: 德克萨斯州、路易斯安那州、阿肯色州、俄克拉荷马州、密苏里州、堪萨斯州、内布拉斯加州、爱荷华州、南达科他州、北达科他州、明尼苏达州。]] | [[Fichier:US map-West.png|thumb|密西西比河以外的美国西部。深红色为仍被视为其一部分的州: 加利福尼亚州、俄勒冈州、华盛顿州、内华达州、爱达荷州、亚利桑那州、新墨西哥州、犹他州、科罗拉多州、怀俄明州、蒙大拿州以及阿拉斯加州和夏威夷州。红色阴影部分是有时被认为属于南部或中西部的州: 德克萨斯州、路易斯安那州、阿肯色州、俄克拉荷马州、密苏里州、堪萨斯州、内布拉斯加州、爱荷华州、南达科他州、北达科他州、明尼苏达州。]] | ||

19 世纪美国西部的殖民化是美国历史上复杂的一章,其特点是野心勃勃、投机取巧,可悲的是也给原住民带来了悲剧。美国政府和私人企业家强行将原住民赶出他们祖先的土地,并灭绝了野牛--许多部落的重要资源--之后,为这些广袤地区的快速殖民化铺平了道路。铁路网的发展是这一扩张的关键因素。横贯美国大陆的铁路不仅方便了货物运输,也使定居者更容易前往西部。火车站成为新城镇的锚点,邻近的土地也被推广并出售给潜在的定居者,而且价格往往很诱人。大量廉价土地的承诺对许多美国人和移民具有强大的吸引力。农民们被大片耕地的前景所吸引,纷纷移民,希望建立繁荣的农场。矿工们被黄金、白银和其他珍贵矿藏的传闻所吸引,纷纷涌向加利福尼亚、内华达和科罗拉多等地区。与此同时,牧民们也被广阔的牧场所吸引。定居者的多样性为西部丰富的文化和经济做出了贡献,但同时也是冲突的根源,尤其是在土地权、资源获取以及与剩余土著居民的互动方面。尽管存在这些挑战,西部还是迅速成为美国机遇和承诺的象征,尽管这种承诺是以牺牲原住民和生态系统为代价实现的。 | |||

19 世纪,牧牛业成为美国西部的经济支柱。随着铁路网的扩张,东部和中西部的市场变得更加通达,对牛的需求不断增长。得克萨斯州凭借广袤的土地和适宜的气候,迅速成为养牛业的主要中心。牛仔是这一产业的主要参与者,在流行文化中往往被浪漫地理想化。他们赶着大群的牛,沿着著名的奇肖尔姆小道等小路,跋涉数百英里到达火车站,在那里将牛装车运往东部市场。赶牛是一项艰巨的任务,需要数周甚至数月的辛勤工作、毅力和勇敢,以应对各种因素和潜在的危险,例如偷牛贼。很多人没有意识到的是,在这些牛仔中,有相当一部分是非裔美国人。南北战争结束后,许多获得自由的非裔美国人开始寻找就业机会,并最终进入了牧牛业,这个行业虽然仍然面临歧视,但却比当时的其他行业提供了更多的机会。据估计,这一时期非裔美国人占牛仔总数的 15%至 25%。这些非裔美国牛仔虽然面临着西部生活固有的歧视和挑战,但在塑造该地区的文化和经济方面发挥了至关重要的作用。尽管他们的贡献往往在传统的描述中被忽视,但他们的贡献证明了美国西部历史的多样性和复杂性。 | |||

19 世纪铁路业的兴起对美国经济的许多领域都产生了深远的影响,养牛业也不例外。铁路能够远距离快速运输大量货物,为西部牲畜生产商开辟了以前无法进入的市场。芝加哥凭借其优越的地理位置,迅速成为铁路行业的主要十字路口,并因此成为肉类包装行业的神经中枢。该市的屠宰场和包装厂采用创新的流水线生产方式,能够快速高效地将牲畜加工成即装即运的肉类产品。冷藏技术的引入是该行业的一次真正革命。在此之前,长途运输肉类而不变质是一项重大挑战。随着冷藏车的出现,肉类可以在运输过程中保持低温,从而打开了全国分销的大门。这不仅让西部的生产商能够进入东部和中西部的市场,也让美国消费者更容易买到和买得起牛肉。因此,牛肉消费量大幅增加,牛肉迅速成为美国人的主要饮食。食品工业的这一转变是一个完美的例子,说明了技术创新与企业家的聪明才智相结合,可以重塑整个行业并影响一个国家的消费习惯。 | |||

19 世纪美国的西进扩张是一个彻底变革的时期。向未知领域的大规模移民不仅重塑了美国的地理版图,也塑造了美国的经济和文化特征。铁路基础设施是这一转变的关键催化剂。铁路将人口稠密的东部与荒凉、资源丰富的西部连接起来,开辟了新的贸易和移民路线。曾经与世隔绝的城镇变成了活动中心,吸引着寻找机会的企业家、工人和家庭。得益于这些新的联系,养牛业尤其蓬勃发展。西部广袤的平原被证明是大规模放牧的理想之地,牛仔们,这些美国文化的象征,赶着大批牛群前往火车站,再从那里将牛群运往东部市场。这一产业不仅加强了西部的经济,还影响了美国文化,诞生了以牛仔生活为中心的神话、歌曲和故事。肉类包装业的兴起,尤其是在芝加哥等中心城市的兴起,标志着食品生产现代化迈出了重要一步。随着创新技术和冷藏技术的使用,肉类可以大规模加工、保存和长途运输,满足城市中心日益增长的需求。归根结底,西方的殖民化不仅仅是向新领土的物理迁移。这是一个经济和文化复兴的时期,创新、雄心和进取心汇聚在一起,将一个年轻的国家转变为一个工业大国,重新定义了美国的身份和命运。 | |||

欧洲移民对大平原的殖民是西进扩张故事中另一个引人入胜的篇章。这片曾被视为 "美国大沙漠 "的广袤土地,在这些新移民的努力和决心下,变成了世界上最富饶的粮仓之一。19 世纪的东欧、中欧和东欧正处于政治、经济和社会动荡之中。许多农民尤其面临贫困、人口过剩和机会有限的问题。美国大片肥沃土地的故事对许多人来说是无法抗拒的,因为他们几乎不需要付出任何代价。波兰、俄罗斯和爱尔兰等国的公民纷纷涌入美国,寻求更好的生活。来到美国后,这些移民带来了农耕技术、传统和文化,丰富了美国的景观。在大平原,他们发现了肥沃的土壤,非常适合种植玉米、小麦和其他谷物。整个社区随之形成,教堂、学校和企业反映了他们家乡的传统。美国政府在这次移民中发挥了积极作用。特别是 1862 年的《宅地法》,是一项旨在增加人口和开发西部的大胆举措。政府向任何愿意耕种和建造房屋的人提供 160 英亩土地,这不仅刺激了定居,还促进了该地区的农业发展。这些政策与移民的创业精神相结合,将大平原变成了农业生产的堡垒。这些移民社区的贡献塑造了该地区的特征,并留下了持久的遗产,这些遗产今天仍在影响着美国的文化和经济。 | |||

自耕农是美国农村的真正先驱。尽管拥有肥沃的土地和机遇,但大平原上的生活并非没有挑战。广袤的开阔地虽然风景如画,却经常遭遇极端天气,从冬季的暴风雪到炎热干燥的夏季,还有可怕的龙卷风。大草原的土壤虽然肥沃,但却长满了厚厚的草根,难以耕种。最初的垦荒工作往往很费力,需要强壮的牲畜和坚固的犁头才能打破地壳。此外,由于大片平原上没有树木,建筑和取暖所需的木材十分稀缺。与世隔绝也是一个持续的挑战。早期的牧民往往远离邻居和城镇,因此很难进入市场、获得补给和人际交往。公路和铁路等基础设施仍处于发展阶段,货物和人员运输成本高、效率低。然而,尽管面临这些挑战,家园拥有者们依然坚定不移。他们利用丰富的草皮资源建造房屋,创建社区,建立学校和教堂。随着时间的推移,通过创新和决心,他们根据平原的条件调整了耕作方法,引进了抗旱作物和节水技术。他们的毅力得到了回报。大平原成为美国的 "粮仓",不仅养活了美国,还养活了世界许多地方。随着基础设施的发展,城镇和村庄繁荣起来,吸引了其他产业和服务。自耕农的故事证明了人类在逆境中的顽强精神,以及将艰难的地貌转变为充满机遇和富饶的土地的能力。 | |||

19 世纪末,大批来自中欧和东欧的移民来到美国,对美国的经济和社会发展产生了深远的影响。这些移民远离家乡的政治和经济动荡,寻求更美好的生活,他们被美国许诺的工作和机会所吸引。当时,铁路行业蓬勃发展,不断需要建造、维护和运营铁路的劳动力。移民们愿意努力工作,拥有各种技能,是满足这一需求的理想人选。他们在建筑工地上工作,在困难的地形上铺设轨道,在维修车间工作,保持机车和货车的平稳运行。同样,西部的采矿业,从科罗拉多州的金矿到蒙大拿州的铜矿,都严重依赖移民劳工。这些矿山的条件往往很危险,但稳定的工资承诺,以及对一些人来说,找到黄金或其他珍贵矿产的可能性,吸引了许多工人。在中西部,快速的工业化为工厂和磨坊创造了前所未有的工人需求。芝加哥、底特律和克利夫兰等城市成为主要的工业中心,生产从机械到消费品的各种产品。来自中欧和东欧的移民凭借他们的经验和职业道德,在这些行业找到了工作,他们的工作条件往往十分艰苦,但却为国家的工业产出做出了巨大贡献。除了经济贡献,这些移民还丰富了美国文化。他们带来了传统、语言、美食和艺术,为美国的文化马赛克增色不少。他们定居的社区成为文化活动中心,教堂、学校、剧院和市场反映了他们独特的传统。 | |||

来自东欧、中欧和东南欧的农民在大平原的定居标志着美国扩张史上的一个重要时期。这些移民往往是为了逃避原籍国的贫困、迫害或政治动乱,他们被美国广袤肥沃的土地和美好生活的承诺所吸引。大平原土壤肥沃,幅员辽阔,为农耕提供了理想的机会。移民们带来了适应原籍国条件的传统耕作技术,并与美国的创新技术相结合。这导致了农业产量的惊人增长,使美国成为世界上小麦、玉米和牛等产品的主要生产国之一。这些农民在美国内陆地区的定居中也发挥了至关重要的作用。他们建立社区,建造学校、教堂和基础设施,为人口和经济的持续增长奠定了基础。在周边农业的推动下,曾经是铁路沿线小前哨或小站的城镇变成了繁荣的商业中心。在农业发展的同时,这些移民的到来也刺激了工业化的发展。他们中的许多人,尤其是那些定居在中西部的人,在当时如雨后春笋般出现的工厂和作坊里找到了工作。他们的技能、职业道德和融入社会的意愿对于满足新兴美国工业的劳动力需求至关重要。 | |||

19 世纪中叶,中国移民来到美国西海岸,标志着美国扩张史上一个独特的篇章。在 "金山 "传说的诱惑下,成千上万的中国人漂洋过海,希望在 1849 年的加州淘金热中找到自己的财富。然而,他们遇到的现实往往与他们的黄金梦大相径庭。虽然有些人在淘金地获得了成功,但大多数华人移民发现自己的工作条件艰苦,工资微薄,还经常受到雇主的剥削。面对竞争和排外情绪,他们被排挤到不太受欢迎的工作和利润较低的金矿区。除了矿场,中国移民在第一条横贯大陆的铁路建设中也发挥了至关重要的作用。受雇于中央太平洋铁路公司,成千上万的华工在危险的条件下铺设铁轨,穿越内华达山脉。他们的辛勤工作、爆破技术和决心对完成这项不朽的工程至关重要。除了体力劳动,许多华人还创办企业,为社区服务。他们开设洗衣店、餐馆、中药店和其他小企业,在旧金山等城市形成了唐人街。这些社区迅速成为文化和经济中心,为经常面临歧视和孤立的华人提供支持和友谊。然而,尽管中国移民做出了巨大贡献,他们却面临着越来越多的敌意。歧视性法律,如1882年的《排华法案》,限制了华人移民,并限制了已在美国的华人的权利。这些措施,再加上日常的暴力和歧视,使许多华人在美国的生活举步维艰。 | |||

加州华人移民的故事是一个在逆境中坚持不懈的故事。1849 年淘金热期间,大批华人移民来到加州,他们试图在这片当时被认为充满机遇的土地上创造更美好的生活。然而,尽管他们辛勤工作,为加州经济和社会做出了巨大贡献,他们却面临着系统性的敌视和歧视。对华人的歧视已经制度化。具体的法律,如 1852 年的《外国矿工税法》,对华人矿工征收高额税收,往往使他们无利可图。后来,1882 年的《排华法案》禁止华人移民长达十年之久,反映出对华人社区日益增长的敌意。暴力事件也屡见不鲜。加利福尼亚州的城市经常发生暴乱,愤怒的暴徒袭击唐人街,焚烧企业和房屋,殴打居民。这些行为的动机往往是经济恐惧、种族成见和就业竞争。为了应对这些挑战,许多华人选择居住在被隔离的唐人街,在那里他们可以找到安全感、友情和归属感。这些社区成为经济和文化活动中心,商店、寺庙、剧院和学校为社区服务。尽管存在歧视和障碍,中国移民在加州的发展中发挥了至关重要的作用。在矿山,他们开采黄金和其他珍贵矿产。在城市,他们开设了商店、餐馆和洗衣店。他们还在横贯大陆的铁路建设中发挥了重要作用,冒着危险将西海岸与美国其他地区连接起来。加州华人移民的故事证明了他们的韧性、决心和克服巨大挑战的能力。他们的遗产延续至今,不仅体现在他们为加州做出的切实贡献上,还体现在他们所体现出的坚韧不拔的精神和决心上。 | |||

横贯大陆铁路的修建是美国 19 世纪最杰出的成就之一,而中国移民正是这一不朽壮举的核心人物。他们在这项事业中发挥了至关重要的作用,但在主流历史记载中却往往被低估或遗漏。主要由于劳动力短缺,修建西部铁路的中央太平洋铁路公司于 1865 年开始雇佣华工。公司官员起初对中国人能否胜任如此繁重的工作持怀疑态度,但他们的效率、职业道德和耐力很快给他们留下了深刻印象。工作条件极其艰苦。中国工人经常承担最危险的工作,包括在内华达山脉坚固的山体中埋设炸药开凿隧道。他们在极端恶劣的天气条件下工作,从酷暑到严冬,随时面临爆炸、滑坡和事故等危险。尽管如此,他们的工资普遍低于白人工人,而且住在简陋的工作营里。尽管面临这些挑战,华工们还是表现出了非凡的智慧。他们使用中国传统的建筑技术,使自己的技能适应美国的环境。例如,当面临在坚硬的岩石中开凿隧道的艰巨任务时,他们用火加热岩石,然后用冷水将岩石冲碎,这种方法是他们在中国学到的。他们的贡献如此之大,以至于当 1869 年最后一根金色的道钉在犹他州的普罗蒙托里峰被打下,标志着铁路的竣工时,中国工人的存在是不容置疑的。然而,尽管他们发挥了关键作用,但在随后的庆祝和纪念活动中,他们往往被边缘化。 | |||

对许多拓荒者来说,在美国内陆,尤其是大平原定居是一项艰巨的任务。虽然丰饶肥沃的土地吸引了许多定居者,但这些地区的现实生活往往与他们的想象大相径庭。大平原与世隔绝的地理位置带来了许多挑战。在铁路建成之前,定居者主要依靠马车和水路运输货物。这意味着他们进入市场(出售农产品和购买补给品的市场)的机会有限。此外,农场和小城镇之间的距离往往很远,很难建立紧密的社区,也很难获得学校、医生或教堂等基本服务。大平原的气候条件是另一大挑战。夏季炎热干燥,如果没有充足的灌溉,耕作将十分困难。另一方面,冬季往往气候恶劣,暴风雪和低温可能危及牲畜和农作物。龙卷风和冰雹也是对定居者的常见威胁。此外,大平原的土壤虽然肥沃,却被一层厚厚的深根草覆盖。这使得最初的犁耕极为困难。定居者们不得不进行创新,使用特殊的犁来打破坚硬的土壤外壳。尽管面临这些挑战,许多定居者仍坚持不懈,调整耕作方法和生活方式,以便在这种艰苦的环境中取得成功。他们开发了该地区特有的耕作技术,例如条耕以减少土壤侵蚀,种植树木作为防风林。随着时间的推移,铁路的到来也为进入市场提供了便利,减少了大平原与世隔绝的状况,使该地区得以繁荣发展。 | |||

= | = 南方 = | ||

The end of the Civil War in 1865 marked the end of the Confederacy and of legal slavery in the United States. However, the promise of freedom and equality for African Americans was not fully realised, particularly in the South. The post-war period, known as Reconstruction, was an attempt to bring the Southern states back into the Union and to secure the rights of the newly freed African Americans. But this period was marked by intense resistance from white Southerners who were determined to restore white domination. The "Black Codes" were a set of laws passed by Southern state legislatures after the Civil War. Although these laws recognised certain rights for African Americans, such as the right to own property and to marry, they also imposed many restrictions. For example, the Black Codes prohibited African-Americans from voting, testifying against whites in court, owning weapons or meeting in groups without a white person present. In addition, these laws imposed annual work contracts, forcing many African-Americans to work in conditions that closely resembled slavery. In addition to the Black Codes, other laws and practices, known as Jim Crow laws, were put in place to reinforce racial segregation and white supremacy. These laws enforced the separation of the races in public places, such as schools, hospitals, public transport and even cemeteries. African Americans were also disenfranchised through tactics such as poll taxes, literacy tests and threats of violence. The implementation of these laws and practices was supported by violence and intimidation. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorised African Americans and the whites who supported them, using lynchings, arson and other acts of violence to maintain the racial status quo. | The end of the Civil War in 1865 marked the end of the Confederacy and of legal slavery in the United States. However, the promise of freedom and equality for African Americans was not fully realised, particularly in the South. The post-war period, known as Reconstruction, was an attempt to bring the Southern states back into the Union and to secure the rights of the newly freed African Americans. But this period was marked by intense resistance from white Southerners who were determined to restore white domination. The "Black Codes" were a set of laws passed by Southern state legislatures after the Civil War. Although these laws recognised certain rights for African Americans, such as the right to own property and to marry, they also imposed many restrictions. For example, the Black Codes prohibited African-Americans from voting, testifying against whites in court, owning weapons or meeting in groups without a white person present. In addition, these laws imposed annual work contracts, forcing many African-Americans to work in conditions that closely resembled slavery. In addition to the Black Codes, other laws and practices, known as Jim Crow laws, were put in place to reinforce racial segregation and white supremacy. These laws enforced the separation of the races in public places, such as schools, hospitals, public transport and even cemeteries. African Americans were also disenfranchised through tactics such as poll taxes, literacy tests and threats of violence. The implementation of these laws and practices was supported by violence and intimidation. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorised African Americans and the whites who supported them, using lynchings, arson and other acts of violence to maintain the racial status quo. | ||

Version du 27 septembre 2023 à 13:47

根据 Aline Helg 的演讲改编[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

美洲独立前夕 ● 美国的独立 ● 美国宪法和 19 世纪早期社会 ● 海地革命及其对美洲的影响 ● 拉丁美洲国家的独立 ● 1850年前后的拉丁美洲:社会、经济、政策 ● 1850年前后的美国南北部:移民与奴隶制 ● 美国内战和重建:1861-1877 年 ● 美国(重建):1877 - 1900年 ● 拉丁美洲的秩序与进步:1875 - 1910年 ● 墨西哥革命:1910 - 1940年 ● 20世纪20年代的美国社会 ● 大萧条与新政:1929 - 1940年 ● 从大棒政策到睦邻政策 ● 政变与拉丁美洲的民粹主义 ● 美国与第二次世界大战 ● 第二次世界大战期间的拉丁美洲 ● 美国战后社会:冷战与富裕社会 ● 拉丁美洲冷战与古巴革命 ● 美国的民权运动

1877 年至 1900 年间,美国经历了一个动荡和变革的时代,通常被称为 "镀金时代"。这个由马克-吐温(Mark Twain)广为流传的词让人联想到一个表面繁荣昌盛,实则隐藏着贫困和社会不平等的时代。这是一个工业化和城市化加速发展的时代,催生了工业巨头和强大的垄断企业。然而,当时的政府似乎偏袒这些企业集团和富裕精英的利益,往往损害工人阶级的利益。

铁路是这场变革的核心要素。美国内战结束后,铁路成为重建的重要工具,尤其是在饱受蹂躏的南方。铁路不仅仅是一种运输工具,它还将整个国家连接在一起,将广大地区联系在一起,促进了前所未有的货物和人员交流。这场运输革命刺激了经济增长,将美国推向了工业大国的行列。然而,这种繁荣并非没有阴影。南方重建结束后,白人恢复了严格的政治控制,导致非洲裔美国人的投票权受到压制,并出台了将种族隔离和歧视编入法典的《吉姆-克劳法》。

1898 年的美西战争以帝国扩张告终。这场对抗不仅肯定了美国在世界舞台上的地位,还导致美国获得了波多黎各、关岛和菲律宾等重要领土。就这样,镀金时代以其财富与贫穷、机遇与不公的鲜明对比,塑造了现代美国,为其在二十世纪发挥主导作用做好了准备。

铁路的作用

铁路是 19 世纪末美国的国家动脉,它深刻地改变了美国的经济、社会和文化面貌。铁路在偏远地区之间架起了有形的纽带,实实在在地缩短了距离,使广袤的美国变得更加四通八达、互联互通。铁路网络的迅速扩张催生了货运革命。农产品、原材料和制成品现在可以在创纪录的时间内长途运输。这不仅让更多的消费者更容易获得产品,也让生产者有机会进入更遥远的市场,提高了生产和竞争力。在经济繁荣的同时,铁路也促进了人们的流动。人们可以从一个海岸到另一个海岸,寻找就业机会、土地或新的生活。这种流动性还促进了文化和思想的交融,有助于形成更加同质化的国家认同。铁路将大都市与小城镇、农业区与工业中心连接起来,创造了一个巨大的内部市场。这种互联不仅刺激了贸易,还鼓励了投资和创新。企业能够从规模经济中获益,为不断扩大的全国市场进行大规模生产。到 19 世纪末,铁路在美国已不仅仅是一种运输工具。它们象征着一个不断发展的国家、繁荣的经济和日益团结的人民。它们塑造了现代美国,为美国在 20 世纪成为经济超级大国做好了准备。

19 世纪末,铁路成为美国发展的支柱,推动了前所未有的经济和社会变革。通过连接东西方和南北方,铁路网将一个幅员辽阔的多元化国家编织在一起,创造了民族凝聚力,刺激了强劲的经济增长。铁路对工业化的影响毋庸置疑。通过快速高效地将原材料运输到工业中心并将成品运往市场,铁路使美国工业得以繁荣发展。现在,工厂可以从遥远的地区获取资源,并将产品分销到全国各地,从而形成了一个一体化的全国市场。除了在工业化中的作用,铁路还为西部殖民打开了大门。曾经被认为无法进入或过于偏远的地区成为了那些寻求新机遇的人的可行目的地。铁路沿线的城镇开始涌现,随之而来的是新一波的定居者、企业家和冒险家。采矿业、农业和林业也从铁路扩张中获益匪浅。矿山可以将矿石运往提炼中心,农民可以到达遥远的市场,而该国广袤的森林则成为利润丰厚的木材产地,所有这些都得益于不断扩张的铁路网络。简而言之,铁路是美国转变为工业强国的推动力。它们不仅重新定义了经济格局,还塑造了美国社会,影响了人口、文化和政治。这一时期以铁路的飞速发展为标志,奠定了现代美国的基础,为美国在 20 世纪的全球领导地位铺平了道路。

19 世纪末美国铁路网的爆炸式发展雄辩地证明了那个时代的工业革命和国家雄心。从1870年到1900年,短短三十年间,铁路总长度从8.5万公里跃升至32万公里,体现了惊人的增长。征服西部在这一扩张中发挥了重要作用。由于土地和机遇的承诺,美国西部吸引了许多定居者。铁路为移民提供了便利,使旅行变得更快捷、更安全。更重要的是,联邦政府通过提供土地来换取铁轨的建设,从而鼓励了铁路的建设。与此同时,国家的经济增长也促进了对强大的交通基础设施的需求。日益发展的工业化需要高效的运输工具将原材料运送到工厂并分销成品。铁路成为这些货物的首选运输方式。这一时期,国内外资本也大量涌入铁路部门。投资者认识到铁路建设和运营的盈利潜力,纷纷注入巨额资金。技术创新也发挥了至关重要的作用。铁路建设和技术的进步意味着铁轨可以更快、更便宜地建成。此外,美国政府认识到铁路对经济和领土发展的战略重要性,为横贯大陆铁路等重大项目提供了大力支持。铁路扩张产生了深远的影响。与世隔绝的地区变得四通八达,地方市场成为全国市场,芝加哥等曾经不起眼的城市成为主要的铁路枢纽和工业大都市。简而言之,19 世纪末铁路网的壮观发展不仅是工程技术的壮举,也反映了一个国家正处于变革的阵痛期,力求充分利用其广阔的领土和丰富的资源。

19 世纪末,美国的铁路发展是一项由私人利益主导的不朽事业。为了应对幅员如此辽阔的国家所带来的物流挑战,需要进行协调。这导致了东部四个时区的引入,这一创新统一了全国的火车时刻表。然而,这些铁路的建设并非没有争议。在争夺主导地位和盈利能力的过程中,许多铁路公司卷入了腐败丑闻,而且往往与政客勾结。它们之间的激烈竞争有时会导致仓促决策,以牺牲质量和安全为代价来追求建设速度。因此,部分铁路网并不总是得到很好的维护,给乘客和货物带来风险。然而,尽管存在这些问题,铁路对国家经济和领土发展的重要性是毋庸置疑的。认识到铁路的战略价值,州政府和联邦政府都为铁路建设提供了大量补贴。这种公共投资与私营部门的智慧和雄心相结合,成为铁路网络迅速扩张的推动力。尽管充满了挑战和争议,但铁路建设塑造了美国的地理、经济和文化,为建立一个互联互通的现代化国家奠定了基础。

19 世纪末,美国铁路如雨后春笋般崛起,对美国的经济和社会结构产生了深远影响。铁路公司从政府的巨额土地补贴中获益,获得了铁路沿线的大片土地。这些往往具有战略意义的收购使它们不仅能够控制运输,还能主宰所服务地区的经济发展。权力和财富的集中导致了垄断和信托的形成。在缺乏适当监管的情况下,这些实体能够随意制定票价,消除竞争,并对国家政策施加相当大的影响。人们常说的铁路大亨成为镀金时代的标志性人物,他们既体现了企业家的聪明才智,也反映了无管制资本主义的过度行为。铁路曾被誉为工程奇迹和进步的象征,但对许多人来说,它已成为不平等的代名词。贫富差距扩大,一边是富裕的精英阶层享受着工业化的成果,另一边则是工人和小农,他们往往受制于大型铁路公司的票价和做法。这种情况加剧了社会和政治紧张局势,引发了民粹主义者等运动,他们呼吁对铁路进行更严格的监管,并实现更公平的财富分配。归根结底,美国的铁路发展史反映了工业化的复杂性,进步与不平等、创新与剥削交织在一起。

19 世纪末美国铁路的扩张尽管充满挑战和争议,但不可否认的是,它为美国带来了巨大的利益,塑造了美国的发展和经济轨迹。首先,铁路彻底改变了交通运输。铁轨从海岸延伸到海岸,实现了货物和人员的流动。这不仅提高了州际贸易的效率,还打开了通往全国市场的大门,西方产品可以在东方城市销售,反之亦然。这种互联互通也刺激了经济增长。曾经与世隔绝的地区变成了活动中心,铁路车站和枢纽周围的城镇不断涌现并繁荣起来。铁路提供的便利吸引了投资者、企业家和工人,形成了发展的良性循环。铁路对西部殖民化的影响也是毋庸置疑的。曾经被认为偏远荒凉的领土变得四通八达。定居者们被土地和机遇的承诺所吸引,纷纷涌入西部,他们通常将铁路作为主要的交通工具。各行各业也从这一扩张中直接受益。例如,采矿业可以将矿石运往东部的提炼中心。农民可以将农作物运往更远的市场,林业可以将木材运往全国各地,以满足日益增长的建筑和工业化需求。

19 世纪末,美国经历了前所未有的工业和领土变革,同时也见证了一场通信革命。除了铁路网络令人印象深刻的扩张之外,电报的发展和邮政系统的改进在建立一个更加互联互通的国家方面也发挥了至关重要的作用。电报尤其标志着与过去的彻底决裂。在电报发明之前,远距离通信既缓慢又不可靠。随着电报线路的引入,过去需要数天甚至数周才能传递的信息现在只需几分钟就能传递。这对商业运作方式产生了深远影响。公司几乎可以实时获得市场和股票信息,从而能够迅速做出明智的决策。它还使协调铁路时刻表和在全国范围内传播重要信息变得更加容易。邮政系统也进行了重大改进。随着向西扩张和城市的发展,拥有可靠的邮政服务来连接市民、企业和政府变得至关重要。邮政线路不断扩大,并在世纪之交推出了送货上门和航空邮件等新服务。这些创新不仅促进了个人通信,还对企业的发展,尤其是邮购和分销行业的发展起到了关键作用。19 世纪末,美国不仅在物质基础设施方面发生了变化,而且在通信方面也发生了变化。电报和邮政系统创造了一个前所未有的网络,将人们和企业联系在一起,为现代经济和互联社会奠定了基础。

虽然在 19 世纪,由于铁路和通信技术的进步,美国的发展和互联程度显著提高,但地区差异依然存在,反映了根深蒂固的历史、经济和文化传统。西部是一个不断变化的边疆。从落基山脉到广袤的平原,西部地形多变,是一片充满机遇和挑战的土地。淘金热、牧场和农业塑造了西部的经济。它也是一个充满冲突的地区,欧洲定居者、原住民和不同血统的移民在这里碰撞和交融,形成了独特的马赛克文化。南方有着种植园农业和奴隶制的历史,在美国南北战争后经历了一段深刻的变革时期。以棉花种植为主的农业经济因奴隶制的结束而发生了翻天覆地的变化。重建试图将新解放的非洲裔美国人融入公民社会,但取得了不同程度的成功。南方还保留了独特的文化,拥有自己的音乐、烹饪和文学传统。东北部是美国的工业和金融中心,是创新和进步的引擎。纽约、波士顿和费城等城市成为工业、商业和文化中心。来自欧洲的大量移民丰富了该地区,带来了传统、技能和文化的多样性。东北部也是进步社会和政治运动的发源地,这些运动寻求应对城市化和工业化带来的挑战。尽管这些地区差异有时会因现代化和相互联系而变得模糊,但它们一直影响着美国的政治、经济和文化。每个地区都各具特色,为美国织锦的丰富性和复杂性做出了贡献,使美国成为一个既统一又多元的国家。

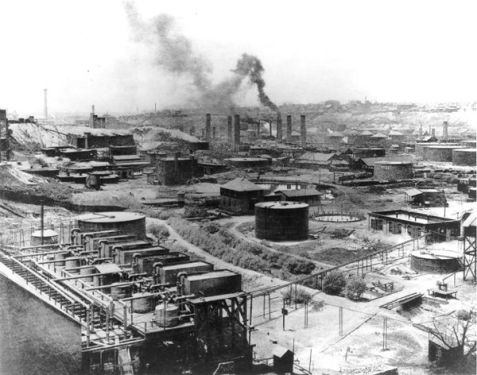

19 世纪末,美国是由不同历史、经济和文化形成的各具特色的地区组成的。西部拥有开阔的视野和广袤的土地,是一片充满希望和挑战的土地。广袤的土地上遍布着繁荣的城镇,这些城镇的建立往往是采矿发现或贸易路线的结果。金、银和其他矿产吸引着冒险家和企业家,而广袤的平原则为农业和畜牧业提供了机会。尽管有这些机遇,但人口密度仍然很低,给人一种边疆的感觉。内战创伤未愈的南方正处于重建和调整时期。曾经由奴隶制支持的棉花种植园主导的经济需要找到新的道路。虽然农业仍然占主导地位,但奴隶制的结束给社会和经济结构带来了深刻的变化。非裔美国人虽然获得了正式的自由,但往往面临着限制其权利和机会的种族隔离法律和歧视性做法。另一方面,东北部是美国工业化的心脏。城市里热气腾腾的工厂和熙熙攘攘的街道是创新和商业的中心。为寻找机会而大量涌入的移民推动了工厂劳动力的发展,并增加了该地区的文化多样性。快速的城市化和工业化创造了充满活力的经济,但也带来了社会挑战,如过度拥挤、不平等和不同社区之间的紧张关系。每个地区都有其特殊性和挑战,都为美国的国家活力做出了贡献,反映了一个处于变革中的国家的多样性和复杂性。

19 世纪之交,美国经历了一场前所未有的技术和基础设施变革。铁路纵横交错,将以前与世隔绝的城镇和地区连接起来,而电报线路则实现了远距离即时通信。不可否认,这些创新促进了经济一体化和流动性,形成了全国性市场,促进了信息交流。然而,尽管相互联系日益紧密,根深蒂固的地区差异依然存在。西部幅员辽阔,自然资源丰富,继续吸引着那些寻求采矿、农业和畜牧业机会的人。西部的边疆特点和文化多样性,以及定居者、原住民和移民之间经常出现的紧张共处,赋予了西部独特的身份。南方因南北战争的后果和奴隶制历史而伤痕累累,一直在努力重新定义其经济和社会。虽然通过铁路和电报与美国其他地区相连,但它仍保留着独特的文化和经济,主要以农业为中心,并面临着重建和种族隔离的挑战。东北部作为全国的工业和金融中心,热情拥抱现代化。在多元化移民劳动力的推动下,工厂、银行和港口蓬勃发展。然而,尽管相对繁荣,该地区仍面临着不同于西部或南部的社会和经济挑战。简而言之,尽管铁路和电报创造了统一的基础设施,但它们无法将美国丰富的文化、经济和历史同质化。这些植根于数百年历史和经验的地区差异,继续影响着美国的发展轨迹,提醒我们,无论技术多么强大,都无法改变根深蒂固的文化和历史特性。

西方

征服美洲印第安人领地

19 世纪中后期,美国西部发生了一系列冲突,政府的政策对该地区的原住民产生了深远的影响。随着美国试图扩张领土并巩固对新获得土地的控制,原住民发现自己陷入了美国扩张主义的动荡之中。尽管人们通常将印第安人迁移政策与 1830 年法案以及沿着臭名昭著的 "眼泪之路 "驱逐切诺基人等东南部部落联系在一起,但该政策的精神一直延续到整个 19 世纪,影响到全国各地的许多其他部落。在西部,苏族、夏安族、内兹佩尔西族等原属于这些部落的领地因其资源和战略价值而备受垂涎。随着定居者、淘金者和铁路建设者蜂拥而至,紧张局势日益加剧。通过条约向原住民做出的承诺经常被违背,曾经保证给予原住民的土地也遭到侵占。美国政府对这些紧张局势的反应往往是使用武力。在原住民反抗侵占他们的土地时,爆发了许多战争和小规模冲突,如苏族战争、尼兹佩斯战争和小比格霍恩战役。最终,政府的政策转向建立保留地,即划定原住民居住的区域,这些区域往往远离他们祖先的土地,条件恶劣。保留地的限制给土著人民带来了毁灭性的后果。以狩猎、捕鱼或游牧农业为基础的传统生活方式在这些封闭的空间里变得不可能。此外,保留地往往管理不善,资源不足,导致饥饿、疾病和对政府援助的依赖。

19 世纪美国对原住民的扩张和迁移政策是美国历史上最黑暗的一页。在对土地的渴望、种族偏见和经济压力的共同作用下,这一政策给土著人民带来了毁灭性的后果。在白人定居者为农业、采矿业和其他商业利益开发肥沃土地的压力下,美国政府往往选择将这些利益置于土著人民的权利和福祉之上。条约往往是在胁迫或欺骗的情况下签署的,当发现新的经济机会时,条约经常被破坏,从而加剧了流离失所和被剥夺的循环。眼泪之路 "就是这种政策最臭名昭著、最悲惨的例子。19 世纪 30 年代中期,在安德鲁-杰克逊担任总统期间,美国政府通过了《印第安人撤离法》,授权强制迁移东南部的几个部落,包括切罗基人、乔克托人、克里克人、奇卡索人和塞米诺尔人。这些人被迫离开祖先的土地,迁往密西西比河以西的地区,主要是现在的俄克拉荷马州。旅途是残酷的。流离失所者被迫步行数百英里,往往没有足够的补给,还要在恶劣的天气条件下行走。疾病、曝晒和饥饿使行军队伍锐减,据估计,数千人(可能多达四分之一)在途中丧生。泪之径 "是美国扩张政策对土著人民影响的有力证明。它提醒人们殖民化的人类代价以及承认和尊重土著人民权利的重要性。

19 世纪美国的扩张和殖民政策给该国的原住民带来了悲惨的后果。美国试图扩张边界,为农业、工业和其他经济利益开发新的土地,土著人民发现自己处在扩张的道路上,并往往付出高昂的代价。暴力通常被用来将土著人民驱逐出他们祖先的土地。战争、小规模冲突和屠杀频繁发生,军队和地方民兵被用来制服或驱逐土著社区。这些冲突往往导致许多土著人死亡,其中包括妇女、儿童和老人。在这些暴力迁移中幸存下来的人被迫离开自己的土地、家园和圣地。他们被迁移到偏远地区,这些地区往往贫瘠荒凉。这些新的土地被称为保留地,通常面积很小,不允许土著人民采用传统的生活方式。狩猎、捕鱼和耕作是他们赖以生存的基本活动,但在这些新地区往往无法进行或受到限制。保留地上的生活十分艰难。条件往往岌岌可危,无法获得食物、水和医疗等基本资源。此外,原住民还受到联邦政府的管辖和控制,联邦政府经常实施旨在同化和根除原住民文化和传统的政策。儿童经常被送到寄宿学校,在那里他们被禁止讲母语或奉行自己的文化。最终,美国的扩张和迁移政策在土著人民的历史上留下了深深的伤痕。生命、土地和文化的损失是无法估量的,这些政策的影响至今仍可感受到。承认并了解这段历史,对于在美国与其原住民之间建立更公平、更平衡的关系至关重要。

西进扩张时期对野牛的大规模捕杀是美国历史上最重大的生态和文化悲剧之一。在欧洲定居者到来之前,估计有 3,000 万至 6,000 万头野牛在北美平原上自由漫步。然而,到了 20 世纪之交,这个数字已经减少到只有几百头。对于平原上的许多原住民来说,野牛不仅仅是食物来源。野牛是他们生存的核心。野牛身上的每一部分都会被利用:肉可以用来做食物,皮可以用来做衣服和住所,骨头可以用来做工具和武器,甚至筋可以用来做线。野牛对许多部落来说还具有深远的精神意义,往往是他们仪式和神话的核心。由于铁路的到来和市场对水牛皮的需求,工业化的水牛狩猎活动受到鼓励,每天都有成千上万头水牛被屠杀。许多水牛纯粹是为了皮毛而被猎杀,只留下尸体在平原上腐烂。但这种灭绝行为并不仅仅是出于利益驱动。在一些人看来,这也是 "驯服 "西方和控制原住民的一种手段。定居者希望通过摧毁原住民的主要生活来源,使他们依赖政府供应,并迫使他们放弃游牧生活方式。这种灭绝对原住民的影响是毁灭性的。由于失去了主要的食物和物资来源,许多社区遭受饥饿和贫困。他们围绕野牛演化了几千年的生活方式在短短几十年间被打破了。对这一悲剧的认识最终促使人们在 20 世纪初开始保护野牛,野牛的数量也随之增加,但远远没有达到最初的数量。然而,狩猎野牛的历史仍然是西进扩张的人类和生态代价的有力证明。

1890 年 12 月 29 日在南达科他州发生的 "伤膝 "大屠杀是美国与土著人民关系史上最黑暗、最悲惨的事件之一。它不仅象征着美国扩张主义政策的残暴,也标志着平原上所谓 "印第安人战争 "的结束。19 世纪末,平原上的原住民离开了祖先的土地,被限制在保留地上,生活条件十分艰苦。同化的压力、土地的丧失和水牛的枯竭使许多部落只能依靠政府的口粮生存。在这种绝望的背景下,包括拉科塔苏人在内的平原民族兴起了 "精神之舞 "运动。这场宗教运动许诺水牛会回归,白人定居者会离开,生活会回到殖民化之前的样子。美国当局对 "精神之舞 "的日益流行感到震惊,并将其误解为一种军事威胁,试图镇压这一运动。这导致了一系列的紧张局势和对抗,并在 "伤膝之战 "中达到高潮。当天,第七骑兵分队试图解除一群拉科塔人的武装,却向手无寸铁的男人、妇女和儿童开火。具体数字不一,但估计有近 200 名苏族人被打死,其中包括许多妇女和儿童。美军士兵也有伤亡,其中许多可能是友军误击造成的。伤膝之地大屠杀即使在当时也受到广泛谴责,至今仍是一个耻辱和争议的话题。对于原住民来说,这是对他们在美国历史上遭受的不公正待遇和残暴行为的痛苦提醒。对于整个美洲民族来说,它证明了扩张和殖民化的人类代价,以及承认和纠正过去错误的必要性。

美国原住民的历史充满了数百年的剥夺、暴力和边缘化。受难膝事件、有计划的流离失所和同化政策以及蓄意灭绝水牛只是土著人民遭受的众多不公正待遇中的几个例子。伤膝之地大屠杀尤其体现了这段历史。这不仅是对手无寸铁的男人、妇女和儿童的残暴攻击,也是对一种文化和精神表现形式--"精神之舞"--的压制,而 "精神之舞 "为面临巨大挑战的民族带来了希望和韧性。灭绝野牛不仅会对生态造成影响,而且会削弱平原民族的经济和文化实力,因为对他们来说,野牛不仅仅是食物来源。野牛不仅是他们的食物来源,还是他们宇宙观、精神信仰和日常生活方式的核心。这些行为以及其他许多行为都留下了深刻而持久的伤痕。这些政策的后果今天仍然显而易见,表现为贫困率高、健康状况差、自杀率高以及许多土著社区面临的其他社会和经济挑战。

美国殖民化和扩张造成的最悲惨后果之一是,在向西扩张期间,美国土著人口急剧减少。人口减少并不仅仅是武装冲突造成的,尽管武装冲突确实起到了一定的作用。它也是疾病、流离失所、贫困、强迫同化和其他因素综合作用的结果。原住民对欧洲人带来的许多疾病没有免疫力,包括天花、流感、麻疹和肺结核。这些疾病往往导致土著居民的高死亡率。此外,与美军和民兵的战争和小规模冲突也造成了许多土著人的伤亡。强迫迁移,如臭名昭著的 "眼泪之路",导致许多土著人因暴露、营养不良和疾病而死亡。一旦流离失所,保留地(通常位于贫瘠或贫瘠的土地上)的生活条件导致营养不良、疾病和对政府口粮的依赖,而这些口粮往往是不够的。政府的政策,如原住民寄宿学校,旨在将原住民同化为主流文化。这往往导致传统、语言和生活方式的丧失,以及心理创伤。此外,野牛对许多平原部落的生存至关重要,但野牛的灭绝使这些人失去了主要的食物和材料来源。这些因素的综合作用导致土著人口在这一时期急剧下降。然而,必须指出的是,尽管有这些挑战和悲剧,原住民还是生存了下来,并继续在美国社会中发挥着重要作用,在面临巨大挑战的情况下保护着自己的文化、语言和传统。

19 世纪下半叶美国向西扩张的标志是人口的爆炸性增长。丰富的土地、矿产资源和经济机会的承诺吸引了大量人口涌入西部,迅速改变了该地区的面貌。1862 年的《宅地法》在这次移民中发挥了至关重要的作用。该法案为公民提供了申请最多 160 英亩公共土地的机会,条件是他们必须在这些土地上耕种并建造房屋。这一优惠政策吸引了许多定居者,包括希望建立农场的家庭和希望开始新生活的个人。此外,在加利福尼亚、内华达和科罗拉多等州发现的金、银和其他贵重矿物也引发了数次淘金热。这些发现吸引了来自各地的矿工和企业家,他们都希望在此发家致富。矿区周围的城镇迅速崛起,有的成为繁荣的大都市,有的则在矿山枯竭后被遗弃。1869 年建成的横贯大陆铁路也刺激了西部的发展。它不仅促进了人口向西流动,还实现了全国范围内的快速货物运输,从而加强了该地区的经济一体化。然而,这种快速增长并非没有后果。定居者的大量涌入加剧了与土著居民的紧张关系,他们看到自己的土地和传统生活方式日益受到威胁。此外,对自然资源的大量开采往往会对环境造成持久的影响。尽管如此,在 19 世纪末,西部从一个基本上未被开发的边疆地区转变为一个融入国家的地区,拥有自己独特的城市、工业和文化。

从 1860 年到 1900 年,美国的人口出现了前所未有的增长。在四十年间,人口从 3100 万跃升至 7600 万,增长了近 145%,令人印象深刻。有几个因素共同促成了这一扩张。人口增长的主要动力之一是自然增长,这是出生人口多于死亡人口的结果。在此期间,医疗保健、营养和总体生活条件得到改善,从而提高了预期寿命和高出生率。除自然增长外,移民在人口增长中也发挥了至关重要的作用。一波又一波的移民来到美国海岸,他们主要来自欧洲。在美好生活、经济机会和个人自由的诱惑下,来自爱尔兰、德国、意大利和俄罗斯等国的数百万移民涌入美国繁荣的城市。最后,西进扩张也是人口增长的一个关键因素。土地的承诺、黄金和其他资源的发现以及横贯大陆铁路的修建,吸引了大批移民前往西部地区。这些曾被视为荒野的地区很快成为活动中心,建立起城镇、农场和工业。在这一关键时期,自然增长、移民和领土扩张共同塑造了美国的人口增长,为我们今天所知的美国奠定了基础。

19 世纪美国的扩张和殖民时期给美国原住民带来了灾难性的后果。他们在这一时期的历史充满了苦难、损失和面对政府敌视政策时的顽强精神。美国政府的领土扩张和同化土著人民的政策造成了直接的、往往是致命的后果。在 "眼泪之路 "等强迫迁移战略的实施过程中,整个部落被从祖先的土地上连根拔起,迁移到遥远的、往往不那么富饶和不那么好客的地方。成千上万的原住民死于疾病、营养不良和疲惫不堪。欧洲殖民者带来的疾病对土著人没有免疫力,这也是导致土著人口减少的主要原因。天花、流感和麻疹等流行病有时在短短几个月内使整个社区人口锐减。武装冲突也一直是痛苦的根源。整个 19 世纪,美国军队与土著部落之间发生了无数次战争和小规模冲突,每一次冲突都进一步减少了土著人的人口和领地。美国历史的这一黑暗篇章证明了扩张和殖民化的人类代价。原住民生命、土地和文化的丧失是美国国家结构中一道深深的伤疤。承认和了解这段历史对于缅怀土著人民和确保今后不再发生此类不公正事件至关重要。

美国的原住民人口在 1860 年至 1900 年间急剧下降。1860 年,土著人口约为 33 万,占美国总人口 3100 万的 1.06%。但到了 1900 年,土著人口数量下降到 23.7 万,仅占总人口的 0.31%,而总人口已增至 7600 万。从占总人口的比例来看,这意味着在短短的 40 年间,总人口下降了 70%。这些数字凸显了这一时期疾病、冲突、被迫流离失所和同化政策对土著人口造成的破坏性影响。1860 年至 1900 年间美国土著人口的大幅减少是一系列悲剧事件和政策造成的。强迫迁移,如臭名昭著的 "眼泪之路",将整个部落从其祖先的土地上连根拔起,迁移到遥远的、往往不那么肥沃和好客的地方。这些迁移导致许多土著人死于疾病、营养不良和疲惫不堪。与美军的武装冲突也导致土著人民损失惨重。这些冲突往往是由于对土地、资源和土著人民主权的争夺造成的。欧洲定居者带来的疾病使许多土著社区遭到灭顶之灾,而土著人民对这些疾病毫无免疫力。天花、流感和麻疹等流行病尤其致命。最后,旨在将原住民融入占主导地位的美国白人社会的同化政策助长了边缘化和文化消解。压制土著语言、传统和信仰的企图对土著社区的身份认同和凝聚力产生了深远影响。美国历史上这一时期发生了一系列针对原住民的不公正事件,其后果至今仍可感受到。承认和了解这段历史对于缅怀土著人民和确保今后不再发生此类不公正现象至关重要。

快速定殖

19 世纪美国西部的殖民化是美国历史上复杂的一章,其特点是野心勃勃、投机取巧,可悲的是也给原住民带来了悲剧。美国政府和私人企业家强行将原住民赶出他们祖先的土地,并灭绝了野牛--许多部落的重要资源--之后,为这些广袤地区的快速殖民化铺平了道路。铁路网的发展是这一扩张的关键因素。横贯美国大陆的铁路不仅方便了货物运输,也使定居者更容易前往西部。火车站成为新城镇的锚点,邻近的土地也被推广并出售给潜在的定居者,而且价格往往很诱人。大量廉价土地的承诺对许多美国人和移民具有强大的吸引力。农民们被大片耕地的前景所吸引,纷纷移民,希望建立繁荣的农场。矿工们被黄金、白银和其他珍贵矿藏的传闻所吸引,纷纷涌向加利福尼亚、内华达和科罗拉多等地区。与此同时,牧民们也被广阔的牧场所吸引。定居者的多样性为西部丰富的文化和经济做出了贡献,但同时也是冲突的根源,尤其是在土地权、资源获取以及与剩余土著居民的互动方面。尽管存在这些挑战,西部还是迅速成为美国机遇和承诺的象征,尽管这种承诺是以牺牲原住民和生态系统为代价实现的。

19 世纪,牧牛业成为美国西部的经济支柱。随着铁路网的扩张,东部和中西部的市场变得更加通达,对牛的需求不断增长。得克萨斯州凭借广袤的土地和适宜的气候,迅速成为养牛业的主要中心。牛仔是这一产业的主要参与者,在流行文化中往往被浪漫地理想化。他们赶着大群的牛,沿着著名的奇肖尔姆小道等小路,跋涉数百英里到达火车站,在那里将牛装车运往东部市场。赶牛是一项艰巨的任务,需要数周甚至数月的辛勤工作、毅力和勇敢,以应对各种因素和潜在的危险,例如偷牛贼。很多人没有意识到的是,在这些牛仔中,有相当一部分是非裔美国人。南北战争结束后,许多获得自由的非裔美国人开始寻找就业机会,并最终进入了牧牛业,这个行业虽然仍然面临歧视,但却比当时的其他行业提供了更多的机会。据估计,这一时期非裔美国人占牛仔总数的 15%至 25%。这些非裔美国牛仔虽然面临着西部生活固有的歧视和挑战,但在塑造该地区的文化和经济方面发挥了至关重要的作用。尽管他们的贡献往往在传统的描述中被忽视,但他们的贡献证明了美国西部历史的多样性和复杂性。

19 世纪铁路业的兴起对美国经济的许多领域都产生了深远的影响,养牛业也不例外。铁路能够远距离快速运输大量货物,为西部牲畜生产商开辟了以前无法进入的市场。芝加哥凭借其优越的地理位置,迅速成为铁路行业的主要十字路口,并因此成为肉类包装行业的神经中枢。该市的屠宰场和包装厂采用创新的流水线生产方式,能够快速高效地将牲畜加工成即装即运的肉类产品。冷藏技术的引入是该行业的一次真正革命。在此之前,长途运输肉类而不变质是一项重大挑战。随着冷藏车的出现,肉类可以在运输过程中保持低温,从而打开了全国分销的大门。这不仅让西部的生产商能够进入东部和中西部的市场,也让美国消费者更容易买到和买得起牛肉。因此,牛肉消费量大幅增加,牛肉迅速成为美国人的主要饮食。食品工业的这一转变是一个完美的例子,说明了技术创新与企业家的聪明才智相结合,可以重塑整个行业并影响一个国家的消费习惯。

19 世纪美国的西进扩张是一个彻底变革的时期。向未知领域的大规模移民不仅重塑了美国的地理版图,也塑造了美国的经济和文化特征。铁路基础设施是这一转变的关键催化剂。铁路将人口稠密的东部与荒凉、资源丰富的西部连接起来,开辟了新的贸易和移民路线。曾经与世隔绝的城镇变成了活动中心,吸引着寻找机会的企业家、工人和家庭。得益于这些新的联系,养牛业尤其蓬勃发展。西部广袤的平原被证明是大规模放牧的理想之地,牛仔们,这些美国文化的象征,赶着大批牛群前往火车站,再从那里将牛群运往东部市场。这一产业不仅加强了西部的经济,还影响了美国文化,诞生了以牛仔生活为中心的神话、歌曲和故事。肉类包装业的兴起,尤其是在芝加哥等中心城市的兴起,标志着食品生产现代化迈出了重要一步。随着创新技术和冷藏技术的使用,肉类可以大规模加工、保存和长途运输,满足城市中心日益增长的需求。归根结底,西方的殖民化不仅仅是向新领土的物理迁移。这是一个经济和文化复兴的时期,创新、雄心和进取心汇聚在一起,将一个年轻的国家转变为一个工业大国,重新定义了美国的身份和命运。

欧洲移民对大平原的殖民是西进扩张故事中另一个引人入胜的篇章。这片曾被视为 "美国大沙漠 "的广袤土地,在这些新移民的努力和决心下,变成了世界上最富饶的粮仓之一。19 世纪的东欧、中欧和东欧正处于政治、经济和社会动荡之中。许多农民尤其面临贫困、人口过剩和机会有限的问题。美国大片肥沃土地的故事对许多人来说是无法抗拒的,因为他们几乎不需要付出任何代价。波兰、俄罗斯和爱尔兰等国的公民纷纷涌入美国,寻求更好的生活。来到美国后,这些移民带来了农耕技术、传统和文化,丰富了美国的景观。在大平原,他们发现了肥沃的土壤,非常适合种植玉米、小麦和其他谷物。整个社区随之形成,教堂、学校和企业反映了他们家乡的传统。美国政府在这次移民中发挥了积极作用。特别是 1862 年的《宅地法》,是一项旨在增加人口和开发西部的大胆举措。政府向任何愿意耕种和建造房屋的人提供 160 英亩土地,这不仅刺激了定居,还促进了该地区的农业发展。这些政策与移民的创业精神相结合,将大平原变成了农业生产的堡垒。这些移民社区的贡献塑造了该地区的特征,并留下了持久的遗产,这些遗产今天仍在影响着美国的文化和经济。

自耕农是美国农村的真正先驱。尽管拥有肥沃的土地和机遇,但大平原上的生活并非没有挑战。广袤的开阔地虽然风景如画,却经常遭遇极端天气,从冬季的暴风雪到炎热干燥的夏季,还有可怕的龙卷风。大草原的土壤虽然肥沃,但却长满了厚厚的草根,难以耕种。最初的垦荒工作往往很费力,需要强壮的牲畜和坚固的犁头才能打破地壳。此外,由于大片平原上没有树木,建筑和取暖所需的木材十分稀缺。与世隔绝也是一个持续的挑战。早期的牧民往往远离邻居和城镇,因此很难进入市场、获得补给和人际交往。公路和铁路等基础设施仍处于发展阶段,货物和人员运输成本高、效率低。然而,尽管面临这些挑战,家园拥有者们依然坚定不移。他们利用丰富的草皮资源建造房屋,创建社区,建立学校和教堂。随着时间的推移,通过创新和决心,他们根据平原的条件调整了耕作方法,引进了抗旱作物和节水技术。他们的毅力得到了回报。大平原成为美国的 "粮仓",不仅养活了美国,还养活了世界许多地方。随着基础设施的发展,城镇和村庄繁荣起来,吸引了其他产业和服务。自耕农的故事证明了人类在逆境中的顽强精神,以及将艰难的地貌转变为充满机遇和富饶的土地的能力。

19 世纪末,大批来自中欧和东欧的移民来到美国,对美国的经济和社会发展产生了深远的影响。这些移民远离家乡的政治和经济动荡,寻求更美好的生活,他们被美国许诺的工作和机会所吸引。当时,铁路行业蓬勃发展,不断需要建造、维护和运营铁路的劳动力。移民们愿意努力工作,拥有各种技能,是满足这一需求的理想人选。他们在建筑工地上工作,在困难的地形上铺设轨道,在维修车间工作,保持机车和货车的平稳运行。同样,西部的采矿业,从科罗拉多州的金矿到蒙大拿州的铜矿,都严重依赖移民劳工。这些矿山的条件往往很危险,但稳定的工资承诺,以及对一些人来说,找到黄金或其他珍贵矿产的可能性,吸引了许多工人。在中西部,快速的工业化为工厂和磨坊创造了前所未有的工人需求。芝加哥、底特律和克利夫兰等城市成为主要的工业中心,生产从机械到消费品的各种产品。来自中欧和东欧的移民凭借他们的经验和职业道德,在这些行业找到了工作,他们的工作条件往往十分艰苦,但却为国家的工业产出做出了巨大贡献。除了经济贡献,这些移民还丰富了美国文化。他们带来了传统、语言、美食和艺术,为美国的文化马赛克增色不少。他们定居的社区成为文化活动中心,教堂、学校、剧院和市场反映了他们独特的传统。

来自东欧、中欧和东南欧的农民在大平原的定居标志着美国扩张史上的一个重要时期。这些移民往往是为了逃避原籍国的贫困、迫害或政治动乱,他们被美国广袤肥沃的土地和美好生活的承诺所吸引。大平原土壤肥沃,幅员辽阔,为农耕提供了理想的机会。移民们带来了适应原籍国条件的传统耕作技术,并与美国的创新技术相结合。这导致了农业产量的惊人增长,使美国成为世界上小麦、玉米和牛等产品的主要生产国之一。这些农民在美国内陆地区的定居中也发挥了至关重要的作用。他们建立社区,建造学校、教堂和基础设施,为人口和经济的持续增长奠定了基础。在周边农业的推动下,曾经是铁路沿线小前哨或小站的城镇变成了繁荣的商业中心。在农业发展的同时,这些移民的到来也刺激了工业化的发展。他们中的许多人,尤其是那些定居在中西部的人,在当时如雨后春笋般出现的工厂和作坊里找到了工作。他们的技能、职业道德和融入社会的意愿对于满足新兴美国工业的劳动力需求至关重要。

19 世纪中叶,中国移民来到美国西海岸,标志着美国扩张史上一个独特的篇章。在 "金山 "传说的诱惑下,成千上万的中国人漂洋过海,希望在 1849 年的加州淘金热中找到自己的财富。然而,他们遇到的现实往往与他们的黄金梦大相径庭。虽然有些人在淘金地获得了成功,但大多数华人移民发现自己的工作条件艰苦,工资微薄,还经常受到雇主的剥削。面对竞争和排外情绪,他们被排挤到不太受欢迎的工作和利润较低的金矿区。除了矿场,中国移民在第一条横贯大陆的铁路建设中也发挥了至关重要的作用。受雇于中央太平洋铁路公司,成千上万的华工在危险的条件下铺设铁轨,穿越内华达山脉。他们的辛勤工作、爆破技术和决心对完成这项不朽的工程至关重要。除了体力劳动,许多华人还创办企业,为社区服务。他们开设洗衣店、餐馆、中药店和其他小企业,在旧金山等城市形成了唐人街。这些社区迅速成为文化和经济中心,为经常面临歧视和孤立的华人提供支持和友谊。然而,尽管中国移民做出了巨大贡献,他们却面临着越来越多的敌意。歧视性法律,如1882年的《排华法案》,限制了华人移民,并限制了已在美国的华人的权利。这些措施,再加上日常的暴力和歧视,使许多华人在美国的生活举步维艰。

加州华人移民的故事是一个在逆境中坚持不懈的故事。1849 年淘金热期间,大批华人移民来到加州,他们试图在这片当时被认为充满机遇的土地上创造更美好的生活。然而,尽管他们辛勤工作,为加州经济和社会做出了巨大贡献,他们却面临着系统性的敌视和歧视。对华人的歧视已经制度化。具体的法律,如 1852 年的《外国矿工税法》,对华人矿工征收高额税收,往往使他们无利可图。后来,1882 年的《排华法案》禁止华人移民长达十年之久,反映出对华人社区日益增长的敌意。暴力事件也屡见不鲜。加利福尼亚州的城市经常发生暴乱,愤怒的暴徒袭击唐人街,焚烧企业和房屋,殴打居民。这些行为的动机往往是经济恐惧、种族成见和就业竞争。为了应对这些挑战,许多华人选择居住在被隔离的唐人街,在那里他们可以找到安全感、友情和归属感。这些社区成为经济和文化活动中心,商店、寺庙、剧院和学校为社区服务。尽管存在歧视和障碍,中国移民在加州的发展中发挥了至关重要的作用。在矿山,他们开采黄金和其他珍贵矿产。在城市,他们开设了商店、餐馆和洗衣店。他们还在横贯大陆的铁路建设中发挥了重要作用,冒着危险将西海岸与美国其他地区连接起来。加州华人移民的故事证明了他们的韧性、决心和克服巨大挑战的能力。他们的遗产延续至今,不仅体现在他们为加州做出的切实贡献上,还体现在他们所体现出的坚韧不拔的精神和决心上。

横贯大陆铁路的修建是美国 19 世纪最杰出的成就之一,而中国移民正是这一不朽壮举的核心人物。他们在这项事业中发挥了至关重要的作用,但在主流历史记载中却往往被低估或遗漏。主要由于劳动力短缺,修建西部铁路的中央太平洋铁路公司于 1865 年开始雇佣华工。公司官员起初对中国人能否胜任如此繁重的工作持怀疑态度,但他们的效率、职业道德和耐力很快给他们留下了深刻印象。工作条件极其艰苦。中国工人经常承担最危险的工作,包括在内华达山脉坚固的山体中埋设炸药开凿隧道。他们在极端恶劣的天气条件下工作,从酷暑到严冬,随时面临爆炸、滑坡和事故等危险。尽管如此,他们的工资普遍低于白人工人,而且住在简陋的工作营里。尽管面临这些挑战,华工们还是表现出了非凡的智慧。他们使用中国传统的建筑技术,使自己的技能适应美国的环境。例如,当面临在坚硬的岩石中开凿隧道的艰巨任务时,他们用火加热岩石,然后用冷水将岩石冲碎,这种方法是他们在中国学到的。他们的贡献如此之大,以至于当 1869 年最后一根金色的道钉在犹他州的普罗蒙托里峰被打下,标志着铁路的竣工时,中国工人的存在是不容置疑的。然而,尽管他们发挥了关键作用,但在随后的庆祝和纪念活动中,他们往往被边缘化。

对许多拓荒者来说,在美国内陆,尤其是大平原定居是一项艰巨的任务。虽然丰饶肥沃的土地吸引了许多定居者,但这些地区的现实生活往往与他们的想象大相径庭。大平原与世隔绝的地理位置带来了许多挑战。在铁路建成之前,定居者主要依靠马车和水路运输货物。这意味着他们进入市场(出售农产品和购买补给品的市场)的机会有限。此外,农场和小城镇之间的距离往往很远,很难建立紧密的社区,也很难获得学校、医生或教堂等基本服务。大平原的气候条件是另一大挑战。夏季炎热干燥,如果没有充足的灌溉,耕作将十分困难。另一方面,冬季往往气候恶劣,暴风雪和低温可能危及牲畜和农作物。龙卷风和冰雹也是对定居者的常见威胁。此外,大平原的土壤虽然肥沃,却被一层厚厚的深根草覆盖。这使得最初的犁耕极为困难。定居者们不得不进行创新,使用特殊的犁来打破坚硬的土壤外壳。尽管面临这些挑战,许多定居者仍坚持不懈,调整耕作方法和生活方式,以便在这种艰苦的环境中取得成功。他们开发了该地区特有的耕作技术,例如条耕以减少土壤侵蚀,种植树木作为防风林。随着时间的推移,铁路的到来也为进入市场提供了便利,减少了大平原与世隔绝的状况,使该地区得以繁荣发展。

南方

The end of the Civil War in 1865 marked the end of the Confederacy and of legal slavery in the United States. However, the promise of freedom and equality for African Americans was not fully realised, particularly in the South. The post-war period, known as Reconstruction, was an attempt to bring the Southern states back into the Union and to secure the rights of the newly freed African Americans. But this period was marked by intense resistance from white Southerners who were determined to restore white domination. The "Black Codes" were a set of laws passed by Southern state legislatures after the Civil War. Although these laws recognised certain rights for African Americans, such as the right to own property and to marry, they also imposed many restrictions. For example, the Black Codes prohibited African-Americans from voting, testifying against whites in court, owning weapons or meeting in groups without a white person present. In addition, these laws imposed annual work contracts, forcing many African-Americans to work in conditions that closely resembled slavery. In addition to the Black Codes, other laws and practices, known as Jim Crow laws, were put in place to reinforce racial segregation and white supremacy. These laws enforced the separation of the races in public places, such as schools, hospitals, public transport and even cemeteries. African Americans were also disenfranchised through tactics such as poll taxes, literacy tests and threats of violence. The implementation of these laws and practices was supported by violence and intimidation. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorised African Americans and the whites who supported them, using lynchings, arson and other acts of violence to maintain the racial status quo.

Faced with a legal and social system deeply rooted in discrimination, African-Americans had to use perseverance and ingenuity to challenge the injustices they faced. Despite the obstacles, they have used every means at their disposal to fight for their rights. African-Americans formed organisations to support their efforts. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, became a major player in the fight for civil rights. It used the courts as its primary means of challenging discriminatory laws, hiring lawyers to represent African-Americans in key court cases. However, these efforts were often hampered by hostile courts, particularly in the South. Judges, often in line with the prevailing prejudices of their communities, were reluctant to rule in favour of black plaintiffs. Moreover, African-Americans who dared to challenge the existing system risked reprisals, ranging from intimidation to physical violence. Despite these challenges, there were some notable victories. One of the most famous is the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, in which the US Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Although this decision did not put an immediate end to segregation, it did mark a turning point in the struggle for civil rights. Apart from the courts, African-Americans also used other means to challenge discrimination. They organised boycotts, sit-ins, marches and other forms of non-violent protest to draw attention to their cause. Iconic figures such as Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks and others emerged as leaders of this civil rights movement.

The resilience and determination of African Americans in the face of systemic oppression was remarkable. In the post-Civil War South, where discrimination was at its deepest and most institutionalised, African Americans found ways to resist and organise. Creating their own organisations was an essential way for African Americans to fight for their rights. Groups such as the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) have played a crucial role in mobilising black communities for the cause of civil rights. These organisations provided a platform for training, strategy and coordination of protest actions. Membership of the Republican Party, once the party of Lincoln and emancipation, was another way for African Americans to claim their political rights. Although this affiliation changed over time, not least because of the Republican Party's 'southern strategy' in the 1960s, during Reconstruction and beyond many African Americans saw the Republican Party as an ally in their struggle for equality. Participation in grassroots movements was also crucial. Iconic figures such as Rosa Parks, whose refusal to give up her seat on a bus sparked the Montgomery bus boycott, and Martin Luther King Jr, with his philosophy of non-violent civil disobedience, inspired thousands to stand up against injustice. Sit-ins, marches and boycotts have become common tools of protest and resistance. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s culminated in events such as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. These collective efforts led to major legislative changes, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex or national origin, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which aimed to remove barriers to voting for African-Americans. These victories, while significant, were only the beginning of an ongoing struggle for equality and justice in the United States. But they are a testament to the strength, determination and resilience of African-Americans in the face of centuries of oppression.

After the Civil War, the period of Reconstruction offered a glimmer of hope for African Americans. With the passage of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, slavery was abolished, citizenship guaranteed and the right to vote extended to black men. However, this period of progress was short-lived. With the withdrawal of federal troops from the South in 1877, the Southern states quickly adopted the "Black Codes", laws that severely restricted the freedoms of African-Americans and established systems of forced labour, segregation and disenfranchisement. In the face of these injustices, African Americans showed remarkable resilience and determination. They established churches, schools and institutions that became pillars of their communities. These institutions provided spaces for education, worship and political mobilisation, essential to the struggle for civil rights. Despite legal and social obstacles, African-Americans also sought to challenge their status through the courts, although these efforts were often hampered by a discriminatory legal system. Figures such as Ida B. Wells courageously denounced lynchings and other forms of racial violence, despite personal threats. Over time, resistance became organised and intensified. Organisations such as the NAACP were created to fight racial discrimination and promote the rights of African-Americans. Emblematic figures such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington and later Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as powerful voices for justice and equality. The struggle for civil rights intensified in the mid-20th century, with boycotts, sit-ins, marches and other forms of non-violent protest. These collective efforts, combined with key court decisions and federal legislation, eventually led to the dismantling of the segregation system and the establishment of equal rights for all citizens, regardless of race.

The US Supreme Court, in the years following the Civil War, had a profound impact on the trajectory of civil rights for African Americans. Although the 14th Amendment was adopted in 1868 to guarantee citizenship and equal protection under the law to all citizens, including African Americans, the Court interpreted this amendment restrictively in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883. In these cases, the Court considered the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which prohibited racial discrimination in public places such as hotels, theatres and railways. The Court ruled that the 14th Amendment did not give Congress the power to legislate against discriminatory acts committed by private individuals or companies. According to the Court, the 14th Amendment only applied to discriminatory acts committed by the States, not by private individuals. The effect of this decision was to leave African-Americans without legal recourse against racial discrimination in many areas of public life. It also paved the way for the adoption of racial segregation laws in the South, known as Jim Crow laws, which institutionalised racial segregation and deprived African Americans of many civil and political rights. The Court's decision in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 is a striking example of how the judiciary can influence the trajectory of civil rights and how constitutional interpretations can have lasting consequences on the lives of citizens. It would take decades of struggle and activism for the civil rights of African Americans to be fully recognised and protected by law.

The Supreme Court, in its 1883 Civil Rights Cases decision, drew a distinction between discriminatory acts committed by the federal government and those committed by state governments or private entities. In interpreting the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment narrowly, the Court held that the clause applied only to discrimination by the federal government. This interpretation has left the states, particularly those in the South, with considerable leeway to regulate their own race relations. As a result, many Southern states quickly passed a series of laws known as "Jim Crow" laws. These laws established strict racial segregation in almost every aspect of public life, from schools to public transport to public places such as restaurants and theatres. Moreover, these laws were supplemented by discriminatory practices that deprived African-Americans of their fundamental rights, such as the right to vote. The Supreme Court's decision therefore had a profound and lasting impact on the lives of African-Americans, reinforcing racial segregation and discrimination for almost a century, until the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s succeeded in overturning these unjust practices.

The Civil Rights Cases decision of 1883 marked a major turning point in the trajectory of civil rights in the United States. By ruling that the 14th Amendment applied only to the actions of the federal government and not to those of the states or individuals, the Supreme Court essentially gave the green light to the southern states to establish a regime of segregation and racial discrimination. These laws, known as "Jim Crow" laws, affected almost every aspect of life, from education to transportation, and deprived African Americans of their fundamental rights. In the face of this institutionalised reality, African-Americans had to show resilience, ingenuity and determination to claim their rights. Although efforts were made throughout the early 20th century to challenge segregation and discrimination, it was the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s that finally succeeded in mobilising national action. Emblematic figures such as Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks and many others galvanised the country around the cause of equality. This movement, with its boycotts, marches and court actions, eventually led to major legislative changes, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. These laws prohibited racial discrimination in employment, education, housing and public places, and protected the right of citizens to vote, regardless of their race. So while the 1883 ruling was a major setback for civil rights, it also served as a catalyst for a movement that ultimately transformed the nation and brought the United States closer to its ideal of equality for all. Overall, the Supreme Court's decision in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 was a major setback for the rights of African Americans in the United States and paved the way for a long and difficult struggle for civil rights. The Court's decision left the regulation of race relations to the individual states, and it was not until the Civil Rights Movement that the issue was addressed.

Plessy v Ferguson was decided following an incident in 1892 when Homer Plessy, a light-skinned African-American man, defied Louisiana law by sitting in a car reserved for whites. Plessy, who was seven-eighths white and one-eighth black, was arrested and convicted of breaking state law requiring the segregation of passengers on trains. The case went to the Supreme Court, where Plessy's lawyers argued that the Louisiana law violated the 13th and 14th Amendments of the US Constitution. However, the Court, in a 7-1 decision, ruled that the Louisiana law did not violate the Constitution as long as the separate facilities were equal in quality. The "separate but equal" doctrine established by this ruling has been used to justify racial segregation in almost every aspect of public life in the United States, particularly in the South. In reality, the facilities and services provided to African Americans were often inferior to those provided to whites. Schools, hospitals, parks and even water fountains for African Americans were often in poor condition, underfunded and overcrowded. The Plessy v Ferguson decision reinforced the legal legitimacy of racial segregation and was a major obstacle to racial equality for over half a century. It was not until 1954, with Brown v Board of Education, that the Supreme Court overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine and declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The impact of Plessy v Ferguson was profound and lasting. It not only legalised segregation, but also reinforced racist attitudes and practices in American society. The struggle to end segregation and achieve equal rights for all American citizens required decades of effort and sacrifice by many courageous individuals.

Plessy v Ferguson reinforced the legal legitimacy of racial segregation and set a precedent that has been used to justify a multitude of discriminatory practices. The Jim Crow laws that followed affected almost every aspect of daily life, from education and public transport to public places and leisure facilities. These laws not only physically separated African-Americans from whites, but also reinforced a system of white supremacy that marginalised and oppressed African-Americans for decades. Under the guise of the "separate but equal" doctrine, Southern states were able to establish separate educational systems, transportation and other public services for whites and blacks. In reality, services and facilities for African-Americans were often far inferior to those for whites. For example, black schools were often underfunded, dilapidated and overcrowded, depriving African-American students of an education of equal quality to their white counterparts. The Plessy decision also had a profound psychological impact on the nation, reinforcing the idea that African-Americans were inferior and deserved unequal treatment. It also gave white Southerners the green light to continue oppressing African-Americans, often with violence and intimidation. It was only after decades of struggle for civil rights, led by courageous and determined activists, that the doctrine of 'separate but equal' was finally overturned. Brown v Board of Education in 1954 was a crucial step in this struggle, declaring that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. However, even after Brown, the fight for equal rights continued, as many Southern states resisted integration and continued to implement discriminatory policies.

The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, guaranteed equal protection under the law for all citizens, regardless of race. The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, explicitly prohibited disenfranchisement on the basis of race, colour or previous condition of servitude. These amendments were supposed to guarantee the civil rights of African-Americans, particularly those who had recently been freed after the Civil War. However, despite these constitutional guarantees, the Southern states quickly adopted a series of laws, known as 'Jim Crow' laws, which established a system of racial segregation in almost every aspect of daily life. These laws were reinforced by social and economic practices that marginalised African Americans and kept them in a subordinate position. The courts have often upheld these practices. The 1896 Plessy v Ferguson decision, for example, validated the "separate but equal" doctrine, allowing segregation as long as separate facilities were considered equal. In reality, facilities for African-Americans were often inferior. In addition, intimidation tactics, poll taxes, literacy tests and other barriers were used to prevent African Americans from exercising their right to vote, despite the 15th Amendment. It was not until the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s that these practices were seriously challenged and finally dismantled. Court rulings, such as Brown v Board of Education in 1954, began to overturn previous case law supporting segregation. Civil rights activists, through direct action, protest and litigation, pushed the country to recognise and rectify the injustices that had been perpetrated for decades.

After the Civil War, the Reconstruction period saw a significant increase in the political participation of African Americans, particularly in the South. However, this period of progress was short-lived. With the end of Reconstruction in 1877, the Southern states began to pass a series of laws and regulations aimed at restricting and eliminating the right of African Americans to vote. The "Black Codes" were initially laws passed in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War to control and restrict the freedom of newly freed African Americans. These were quickly followed by Jim Crow laws, which institutionalised racial segregation and discrimination in the South. Literacy tests were one of many tactics used to prevent African Americans from voting. These tests were often worded in a deliberately confusing or ambiguous way, making it difficult for anyone with any level of education to pass. In addition, polling place officials had wide latitude in deciding who should take the test, allowing for discriminatory enforcement. Poll taxes were another method used to prevent African-Americans from voting. These taxes, which had to be paid in order to vote, were often too high for many African-Americans, who lived in poverty. In addition, some jurisdictions had "grandfather clauses", which exempted voters whose grandfathers had the right to vote before the Civil War, effectively excluding most African-Americans. Other discriminatory practices included the use of 'white' ballots, where candidates' names were printed on different coloured backgrounds, allowing officials to reject African-American ballots. Threats, violence and intimidation were also commonly used to dissuade African-Americans from voting. These practices had a devastating impact on African-American voter turnout. In many Southern counties, the number of registered African-American voters dropped to zero or close to it. It was not until the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and in particular the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, that these discriminatory practices were eliminated and the voting rights of African-Americans were fully restored.

The 1896 decision in Plessy v Ferguson was a major turning point in the history of civil rights in the United States. By validating the doctrine of "separate but equal", the Supreme Court gave its approval to systematic racial segregation, as long as separate facilities were considered equivalent. In practice, however, facilities and services for African-Americans were often inferior to those for whites. This decision reinforced and legitimised the Jim Crow laws that were already in place in many Southern states. These laws, which covered almost every aspect of life, from education to transport to public places, created institutionalised segregation that lasted for several decades. They were also used to justify the disenfranchisement of African-Americans through means such as literacy tests, poll taxes and other bureaucratic hurdles. Legalised segregation also reinforced racist attitudes and prejudices, creating an atmosphere of discrimination and oppression for African Americans. It also helped perpetuate economic, educational and social inequalities between whites and African-Americans. It is important to note that Plessy v Ferguson was not successfully challenged until Brown v Board of Education in 1954, when the Supreme Court overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine for education. This decision marked the beginning of the end of institutionalised segregation in the United States, although the struggle for civil rights and equality continues to this day.

The Supreme Court of the United States, as the highest judicial body in the land, plays a crucial role in interpreting the Constitution and determining the fundamental rights of citizens. Its decisions have a lasting impact, often shaping the legal and social landscape for generations. After the Civil War, the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments were adopted to abolish slavery, guarantee citizenship and equal rights for all, and protect the right of African-Americans to vote. However, despite these constitutional protections, the rights of African Americans have been systematically violated, particularly in the South. Discriminatory laws, known as "Jim Crow" laws, were passed to restrict the rights of African-Americans, including their right to vote. Supreme Court decisions often reinforced these discriminatory practices. The Plessy v Ferguson decision of 1896 is a flagrant example, where the Court validated the doctrine of "separate but equal", thereby legalising racial segregation. This decision gave the green light to the states to institutionalise racial discrimination, with devastating consequences for African-Americans. It wasn't until the mid-twentieth century, with the Civil Rights Movement, that the fight for equality for African Americans gained ground. Iconic figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, along with thousands of other activists, protested, demonstrated and fought to end segregation and secure civil rights for African Americans. The Supreme Court, in later decisions such as Brown v Board of Education in 1954, finally began to correct some of its earlier miscarriages of justice, declaring that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The struggle for civil rights for African Americans in the United States illustrates the tension between constitutional protections and their actual implementation. It also shows the crucial importance of the Supreme Court in defining and protecting the fundamental rights of citizens.

Around 1890, the American South was deeply entrenched in a system of segregation, violence and discrimination against African-Americans. Although slavery was abolished after the Civil War, the Southern states quickly adopted a series of laws and regulations, known as "Black Codes", to restrict the rights and freedoms of African-Americans. These codes imposed severe restrictions on the daily lives of African Americans, from where they could live and work to how they could interact with whites. Segregation was rampant, with separate schools, transport, restaurants, hotels and even water fountains for whites and blacks. African Americans were also disenfranchised through tactics such as poll taxes, literacy tests and threats or acts of violence. Violence against African-Americans was common and often went unpunished. Lynchings, in particular, were a brutal form of racial violence that terrorised the black community. These acts were often perpetrated under the pretext of punishing a real or perceived crime, but in reality served to reinforce white control and domination over African Americans. The Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v Ferguson in 1896 reinforced this system of segregation. By ruling that segregation was constitutional as long as separate facilities were "equal", the Court endorsed the "separate but equal" doctrine. In reality, facilities and services for African-Americans were often inferior to those for whites. The Plessy decision gave the southern states the green light to codify and extend racial segregation and discrimination. It also sent a clear message that the federal government would not stand in the way of these practices. It would take decades of struggle, protest and advocacy before this decision was finally overturned and the civil rights of African Americans were fully recognised.

The sharecropping system became predominant in the post-Civil War South, particularly with the end of slavery. Large plantations, which had previously depended on slave labour to grow cotton and other crops, were broken up into smaller plots. These plots were then rented out to sharecroppers, who were often former slaves with no land or resources to start their own farms. In theory, sharecropping seemed to offer an opportunity for African Americans to work the land and earn a living. In reality, it was a deeply unequal and exploitative system. Sharecroppers were given a plot of land to cultivate, as well as tools, seeds and other supplies needed to grow crops. In exchange, they had to give a substantial share of their harvest to the landowner. The landowners often set the prices for supplies and commodities, resulting in debts for the tenant farmers. With the fall in cotton prices on the international market at the end of the 19th century, the situation of sharecroppers deteriorated further. Many found themselves trapped in a cycle of debt, borrowing money from the landowner for seed and supplies, then repaying these debts with their harvest. If the harvest failed or prices were low, they went further into debt. The sharecropping system perpetuated the poverty and economic dependence of African Americans in the South for decades. It also reinforced racial and economic power structures, with white landowners controlling the land and resources, and black sharecroppers working the land without ever really having the opportunity to rise economically or socially.

The economy of the South, once dominated by vast cotton plantations and supported by slave labour, underwent a radical transformation after the Civil War. The end of slavery meant the end of an economic system that had enriched a white elite for generations. However, the promise of Reconstruction, a post-Civil War period aimed at integrating freed African Americans into society as full citizens, was quickly betrayed. Jim Crow laws, black codes and other discriminatory measures were put in place to maintain white supremacy and marginalise the black population. The sharecropping system, which emerged as a response to the economic crisis of the post-Civil War South, trapped many African Americans in a cycle of dependency and debt. Sharecroppers were often at the mercy of landowners, who controlled not only the land but also the supplies needed to grow it and the markets where the crops were sold. With the fall in cotton prices at the end of the 19th century, many tenant farmers found themselves in debt, unable to escape their precarious situation. Endemic poverty, exacerbated by a declining economy and discriminatory laws, created difficult living conditions for many African Americans in the South. Limited access to education, healthcare and economic opportunities has reinforced racial and economic inequalities. Many African Americans sought to escape these conditions by migrating north and west during the Great Migration, seeking better opportunities and escaping the segregation and violence of the South.

The industrialisation of the South after the Civil War represented a major change for a region that had been dominated by an agrarian economy based on plantations. Although agriculture, particularly cotton growing, remained central to the Southern economy, the emergence of the steel and textile industries provided new economic opportunities and helped to diversify the region's economy. The steel industry, in particular, experienced significant growth in coal- and iron-rich areas such as Alabama. The city of Birmingham, for example, has become a major centre for steel production due to its proximity to coal and iron ore deposits. These industries have attracted investment from the North and abroad, stimulating economic growth. The textile industry, meanwhile, benefited from the South's long tradition of cotton production. Mills were established throughout the South, transforming raw cotton into fabrics and other products. Cities such as Charlotte in North Carolina became important centres for the textile industry. However, this industrialisation came at a cost. Southern workers, including many poor African-Americans and whites, were often employed in harsh conditions and for very low wages. Trade unions were weak and labour laws were either non-existent or not enforced, allowing factory owners to exploit their workers. In addition, dependence on cheap labour hampered technological innovation in certain industries, making the South less competitive with the more industrialised regions of the North. Despite these challenges, industrialisation has played a crucial role in transforming the South from a predominantly agrarian economy to a more diversified one, marking the beginning of a period of change and modernisation for the region.

Logging became a major industry in the South in the post-Civil War period, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The vast pine and other woodlands of the South were a valuable natural resource that had not been exploited on a large scale before this period. The combination of the expansion of the rail network, which facilitated the transport of timber to national markets, and the growing demand for timber for construction, furniture and other uses led to a rapid increase in logging. Many northern companies invested in the southern forestry industry, attracted by the availability of vast tracts of forest land at relatively low prices. However, this rapid exploitation has had environmental consequences. Massive deforestation has led to soil erosion, disruption of natural habitats and loss of biodiversity. Vast tracts of old-growth forest have been felled, often without any effort at reforestation or sustainable management. The forestry industry has also had socio-economic implications. It created jobs for many residents of the South, but these jobs were often insecure and poorly paid. Forestry workers, often referred to as "loggers", worked in difficult and dangerous conditions. Logging camps were often isolated and rudimentary, and workers were dependent on the companies for housing, food and other necessities. Over time, as deforestation increased and awareness of the environmental consequences grew, efforts were made to promote more sustainable forest management. However, the impacts of this period of intensive exploitation are still visible today in many regions of the South.

The South's dependence on the cotton economy, combined with the destruction caused by the civil war, created a precarious economic situation. Cotton, known as "white gold", had been the South's main export crop before the war, and the region had invested heavily in this monoculture. However, after the war, several factors contributed to the fall in cotton prices: overproduction, international competition and reduced demand. The sharecropping system, which developed after the war to replace the slave system, also contributed to economic insecurity. Sharecroppers, often former slaves, rented land from landowners in exchange for a share of the harvest. But this system often led to a cycle of debt, as sharecroppers had to buy supplies on credit and were tied to the land by debt. The South's precarious financial situation after the war attracted many investors from the North, often referred to by Southerners as 'carpetbaggers'. These investors took advantage of the South's economic situation to buy land, businesses and other assets at derisory prices. This massive acquisition of assets by outside interests reinforced the feeling of occupation and loss of control among Southerners. In addition, the reconstruction of the South was marked by political and racial tensions. The federal government's efforts to rebuild the region and guarantee the rights of African-Americans were often thwarted by local groups resistant to change. Overall, the post-Civil War period was a time of upheaval and transformation for the South. While the region experienced industrial and economic progress, it also faced major challenges, including Reconstruction, the transition to a post-slavery economy and the struggle for civil rights.

The economic history of the American South is marked by a slow but steady transition from agriculture to industrialisation. For a long time, the South was defined by its agrarian economy, dominated by cotton growing. This dependence was reinforced by the sharecropping system, which kept many poor African-Americans and whites in a cycle of debt and dependence on landowners. The industrialisation of the South was delayed by several factors. The destruction caused by the Civil War, lack of investment in infrastructure and education, and conservative economic and social policies all played a part. In addition, the availability of cheap, non-unionised labour was often used to attract labour-intensive industries, rather than high-tech or innovative ones. However, in the 20th century, a number of factors began to transform the economy of the South. The expansion of the road network and the increase in education made the region more attractive to investors. In addition, the civil rights movement ended legal segregation, opening up economic opportunities for African-Americans and creating a fairer labour market. In the 1960s and 1970s, the South began to attract manufacturing industries, particularly in the automotive sector, with the installation of factories by foreign companies. Favourable tax policies, lower labour costs and a generally anti-union attitude made the South attractive to business. Economic diversification has also been reflected in the growth of the service, technology and financial sectors. Cities such as Atlanta, Charlotte and Dallas have become major centres in these areas. Despite this progress, economic disparities persist. Many rural areas in the South continue to struggle with poverty and lack of economic opportunity. However, the transformation of the South from a predominantly agrarian economy to a diversified economy is a testament to its ability to adapt and evolve in the face of challenges.

After the Civil War, the American South went through a period of economic and social reconstruction. The devastation of the war, combined with the end of slavery, turned the region's traditional agrarian economy on its head. Although agriculture remained the mainstay of the Southern economy, the system on which it was based changed. The large plantations gave way to a system of sharecropping, where farmers rented land and paid their rent in cotton or other crops. Cotton remained the main cash crop, but its dominance was undermined by falling world market prices and pests such as the cotton weevil. Other crops, such as tobacco and timber, have also played an important role in the economy of the South. The forests of the South have been exploited to meet the growing demand for timber, pulp and other forest products. However, despite its wealth of raw materials, the South lagged behind the North in terms of industrialisation. Capital and technological innovation were concentrated in the North, and the South found it difficult to attract the investment needed to develop its own industries. In addition, the lack of infrastructure, such as railways and ports, made it difficult to export raw materials from the South to world markets. It was only in the twentieth century, with the arrival of new industries and the expansion of infrastructure, that the South began to industrialise and urbanise. The textile industry, for example, developed in the South because of the availability of cotton and cheap labour. Similarly, the exploitation of natural resources such as coal, oil and iron led to the emergence of new industries in the region. Urbanisation also began to take hold, with cities such as Atlanta, Dallas and Charlotte becoming major economic centres. However, despite these developments, for much of the twentieth century the South remained an economically disadvantaged region compared to the rest of the country, with higher rates of poverty and lower levels of education.

The South's economic dependence on the North has had profound implications for the region. After the civil war, the South was economically devastated. Infrastructure was in ruins, plantations were destroyed, and the end of slavery meant that the economic system on which the South was based had to be completely rethought. Against this backdrop of vulnerability, the South desperately needed capital to rebuild. The North, having emerged from the war in a much stronger economic position, was in a position to provide this capital. However, this investment was not without conditions. Northern industrialists saw the South as an investment opportunity. They bought land, factories, railways and other assets at derisory prices. As a result, much of the Southern economy became the property of Northern interests. These owners often had little interest in the long-term welfare of the region, seeking instead to maximise their short-term profits. This dynamic reinforced the economic dependence of the South. Workers in the South found themselves working for companies based in the North, and often at lower wages than their counterparts in the North. In addition, profits generated in the South were often reinvested in the North, rather than in the region where they were earned. This situation also had political implications. Northern economic elites with financial interests in the South often influenced the politics of the region to protect those interests. This sometimes led to policies that favoured Northern companies at the expense of local workers and entrepreneurs. Ultimately, the South's economic dependence on the North helped to perpetuate the region's economic and social inequalities. Although the South has experienced periods of economic growth, the fundamental structure of its economy, marked by dependence and external control, has made it difficult for the region to close the gap with the rest of the country.

Despite these historical challenges, the South has shown remarkable resilience and adaptability. In the 20th century, the region began to attract national and international investment, thanks in part to its low labour costs, favourable tax policies and improved infrastructure. The southern states also invested in education and vocational training, recognising the importance of human capital for economic development. The industrialisation of the South has been stimulated by the establishment of foreign and domestic automotive plants, as well as the development of technology hubs such as the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina. In addition, the South has become a major centre for the aerospace industry, with companies such as Boeing, Lockheed Martin and Airbus having major operations in the region. The growth of service industries, particularly in finance, healthcare and education, has also played a crucial role in the South's economic transformation. Cities such as Atlanta, Charlotte and Dallas have become major financial and commercial centres. However, despite this progress, the South continues to face challenges. Economic and social disparities persist, and in some rural areas, poverty and unemployment remain high. In addition, the region must face up to the challenges posed by globalisation, international competition and technological change. Nevertheless, the history of the South shows that the region is capable of change and adaptation. With continued investment in education, infrastructure and innovation, the South has the potential to overcome its historical challenges and continue to prosper in the future.

The "Black Codes" created a system that trapped many African Americans in a cycle of poverty and dependency. These laws allowed white landlords to hire out prisoners for forced labour, often under brutal and inhumane conditions. This system, known as "peonage", was essentially a form of slavery by another method. African-Americans who were unable to pay fines or debts could be 'hired out' to white landlords to work until their 'debt' was repaid. In reality, this 'debt' was often manipulated to ensure that the individual remained in indefinite servitude. In addition, vagrancy laws were often used to specifically target African-Americans. For example, if an African-American was found to be unemployed, he could be arrested for vagrancy. Once arrested, he was often fined a sum he could not pay, leading to him being 'hired out' to work for a white landlord to 'pay off' the fine. These practices not only deprived African-Americans of their freedom, but also strengthened the economic power of the white elites in the South. White landlords benefited from cheap labour, while African-Americans were denied any opportunity for economic advancement. It is important to note that although the 'black codes' were adopted in the South, racial prejudice and discrimination were widespread throughout the country. However, in the South, these prejudices were institutionalised through laws that actively reinforced white supremacy and the subordination of African Americans. It took decades of struggle, including the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, to begin to dismantle these oppressive systems and secure the civil and political rights of African Americans.

Working conditions were often comparable to those of antebellum slavery. Workers were subjected to extremely long working days, with little or no rest. They were often poorly fed and housed in precarious conditions. Shelters were rudimentary, offering little protection from the elements. Medical care was virtually non-existent, meaning that illness and injury were common and often fatal. Supervisors and owners used violence to maintain order and discipline. Corporal punishment, such as whippings, was commonly used to punish minor offences or to encourage workers to work harder. Attempts to escape were severely punished, and it was not uncommon for workers to be chained or shackled to prevent them from escaping. Families were often separated, with children sometimes rented out to different landlords, far from their parents. This forced separation of families was another form of psychological control, as it created a constant fear of losing loved ones. The forced labour system also had profound psychological effects on African-Americans. The constant dehumanisation, violence and deprivation left lasting scars on African-American communities. Fear and distrust of the authorities, as well as a sense of powerlessness in the face of an oppressive system, have been passed down from generation to generation.

The industrialised North had its own economic interests to protect and promote. The cheap labour of the South was attractive to industrialists seeking to maximise their profits. Agricultural products and raw materials, such as cotton, were essential for Northern factories. So, even though slavery had been abolished, the system of forced labour that emerged after the Civil War was tacitly accepted by many economic players in the North because it continued to provide low-cost raw materials. In addition, the geographical and cultural distance between the North and the South meant that many citizens of the North remained indifferent to, or ignorant of, the living conditions of African-Americans in the South. The media of the time did not always cover injustices in the South exhaustively or accurately, and it was easy for Northerners to focus on their own economic and social challenges. However, it is also important to note that some Northern citizens and groups attempted to intervene or protest against injustices in the South. Abolitionists, for example, continued to advocate for the rights of African-Americans after the Civil War. But these voices were often marginalised or ignored in the dominant discourse. It was only with the Civil Rights Movement, when the injustices of the South were brought to national attention through television and the media, that the country as a whole began to become aware of and actively oppose discrimination and segregation. The images of peaceful demonstrators being attacked by the police, the accounts of brutality and the testimonies of the victims finally spurred the country into action to put an end to centuries of racial injustice.

The economic situation in the South after the Civil War was complex. The end of slavery disrupted the previous economic system, based on slave labour on plantations. Although slavery had been abolished, racial and economic inequalities persisted. African-Americans, freed from slavery, found themselves in a precarious situation. Without land or resources, many were forced to work as sharecroppers or farm labourers, often for their former masters. Under this system, they rented land and paid the owner in kind, usually a share of the harvest. This often kept them in a cycle of debt and dependency. At the same time, industrialisation in the South was slower than in the North. The industries that developed, such as textile mills and mines, offered jobs mainly to whites. However, these jobs were not well paid. White workers in the South, often from poor rural backgrounds, were also exploited, albeit in a different way to African-Americans. They were often paid in vouchers that could only be used in company-owned shops, which also kept them in a cycle of debt. Competition for these low-paid jobs and racial tensions were often fuelled by factory owners and managers to prevent solidarity between white and black workers. Managers feared that if workers united, they might demand better wages and working conditions. The post-Civil War South was a region where race and class were closely intertwined, and where racial divisions were often used to maintain an economic status quo that favoured a white elite while exploiting both white and black workers.

These small industrial towns, often called 'company towns' in the US, were a feature of the post-Civil War South. They were built and managed by a single company, usually a textile mill or a mine. These companies provided not only employment, but also housing, shops, schools, churches and sometimes even the currency used in the town. Everything was under the control of the company. Life in these company towns was both protective and restrictive. On the one hand, workers had housing, jobs and services on their doorstep. On the other hand, they were often paid in vouchers that could only be used in the company's shops, which kept them in a cycle of debt. In addition, companies often exercised strict control over workers' lives, regulating everything from alcohol consumption to trade union membership. African-Americans were generally excluded from these company towns. Although they were an essential workforce in the agrarian South, they were largely excluded from the new industrial opportunities. Factory jobs were reserved for whites, while African-Americans were relegated to low-paid service or agricultural work. This exclusion was both the result of racial prejudice and a deliberate strategy on the part of business leaders to divide the workforce and prevent unity between white and black workers. So although the South underwent economic change after the Civil War, structures of racial power and inequality persisted, just in a different form. The company towns are an example of how economics and race were inextricably linked in the post-Civil War South.

The system of segregation and discrimination in the post-Civil War South was rooted in an ideology of white supremacy. Although many white Southerners lived in poverty and faced similar economic challenges to African Americans, the system of segregation offered them a social and psychological advantage. They could see themselves as superior simply because of the colour of their skin. This illusion of superiority was essential to maintaining social order in the South. It allowed white elites to divide the working class and prevent any potential alliance between white and black workers. By giving poor whites a group (blacks) they could consider inferior, the elites could maintain their control over the region. Jim Crow laws, black codes and other forms of institutional discrimination were tools used to reinforce this racial hierarchy. These laws and practices not only deprived African-Americans of their fundamental rights, but also served as a constant reminder of their inferior status in society. Lynching, racial violence and other forms of intimidation were also used to maintain this hierarchy and to discourage any form of resistance or challenge. The system of segregation and discrimination in the South was not just about economic control, but also about power and domination. It was designed to maintain a racial hierarchy and to ensure white supremacy in all aspects of life.

After the Civil War, the South sought to restore some form of control over the African-American population, even though slavery had been officially abolished. The "Black Codes" and later Jim Crow laws were put in place to restrict the rights of African Americans and keep them in a subordinate position. These laws affected almost every aspect of life, from education and employment to housing and transport. The sharecropping system, which emerged after the Civil War, chained many African Americans to the land in conditions that closely resembled slavery. Sharecroppers were often in debt to the landowners and were tied to the land by contracts that prevented them from leaving. They were often paid in kind rather than in money, which made them even more dependent on the landowners. In addition, limited access to quality education, discrimination in hiring and lower wages kept many African Americans in the South in a cycle of poverty. Economic opportunities were limited, and African-Americans were often relegated to the lowest paid and most precarious jobs. Violence and intimidation were also common. Lynchings, race riots and other forms of violence were used to maintain white supremacy and to discourage African Americans from demanding their rights. It took decades of struggle, resistance and sacrifice to begin to dismantle these systems of discrimination and oppression. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s was a turning point, with iconic figures such as Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks and others leading the charge for change. Thanks to their efforts, and those of many others, significant progress was made in ending legal segregation and securing civil rights for African Americans. However, the legacy of these discriminatory systems is still felt today, and the fight for equality and justice continues.

The North-East