美国宪法和 19 世纪早期社会

根据 Aline Helg 的演讲改编[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

美洲独立前夕 ● 美国的独立 ● 美国宪法和 19 世纪早期社会 ● 海地革命及其对美洲的影响 ● 拉丁美洲国家的独立 ● 1850年前后的拉丁美洲:社会、经济、政策 ● 1850年前后的美国南北部:移民与奴隶制 ● 美国内战和重建:1861-1877 年 ● 美国(重建):1877 - 1900年 ● 拉丁美洲的秩序与进步:1875 - 1910年 ● 墨西哥革命:1910 - 1940年 ● 20世纪20年代的美国社会 ● 大萧条与新政:1929 - 1940年 ● 从大棒政策到睦邻政策 ● 政变与拉丁美洲的民粹主义 ● 美国与第二次世界大战 ● 第二次世界大战期间的拉丁美洲 ● 美国战后社会:冷战与富裕社会 ● 拉丁美洲冷战与古巴革命 ● 美国的民权运动

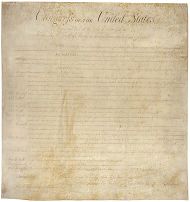

1787 年通过的《美国宪法》不仅是美国联邦政府的基础,也是阐明和保护公民权利与自由的象征性大厦。自通过以来,这部基本宪章已经历了 27 次修订,表明其能够根据社会不断变化的需求而发展。在本课程中,我们将探讨围绕这部宪法的根源、发展和紧张局势,特别是直至 1861 年至 1865 年内战的动荡时期。

但对这一时期的研究并不止于宪法。我们还将深入研究政治、宗教和社会文化方面的变化,这些变化最终导致了 1823 年门罗主义的提出。门罗主义认为欧洲对新大陆的任何干涉都将被视为威胁,这一理论影响了美国几十年的外交政策。通过沉浸在 19 世纪的美国,我们揭示了塑造美国历史的深刻机制,这些机制至今仍不可避免地影响着美国的面貌。

邦联条款》和各州宪法

独立的政治和社会利害关系

1776 年《独立宣言》的发表标志着美国殖民地与英国王室决裂,这一大胆的举动之后,新独立的各州感到迫切需要建立一个统一的政府结构。为此,13 个建国州于 1777 年起草并通过了《邦联条款》,制定了美国的第一部宪法。这一基本宪章不仅受到各州之间联合与合作愿望的影响,而且还受到对中央集权政府根深蒂固的不信任的影响,这种不信任是在数十年反抗英国君主专制压迫的斗争中形成的。这些条款旨在保障各州的主权,同时建立一个松散的邦联,由大陆会议掌握对国家重要事务的决策权。然而,这种对英国中央集权治理模式的反动使得大陆会议的力量相对薄弱,无权提高税收或维持常备军,这反映了人们对中央集权暴政可能性的警惕。

在美国革命后的动荡时期,美国发现自己处于一个微妙的位置,因为它要在从与英国的冲突中吸取的教训与一个新兴国家的需求之间寻求平衡。尽管《邦联条款》的设计初衷是为了避免中央集权的暴政,就像他们在英国王室统治下所经历的那样,但事实证明它不足以满足一个不断扩张的国家的需求。中央政府无法提高税收,因此无力偿还日益增长的战争债务。由于缺乏监管国家间贸易的机构,导致贸易分歧和经济紧张。此外,由于没有有效的机制来执行联邦一级的法律,这个国家往往更像是一个单独国家的集合,而不是一个统一的联盟。

面对这些挑战,以及意识到《宪法》条款可能过于局限,詹姆斯-麦迪逊(James Madison)和亚历山大-汉密尔顿(Alexander Hamilton)等当时的许多领导人都主张对现有制度进行彻底改革。这一认识最终促成了 1787 年费城制宪会议的召开。代表们决定彻底重新思考政府的结构,吸取过去的教训并预测未来的需求,而不是简单地修改宪法条款。由此产生的美国宪法在各州权力和联邦政府权力之间建立了平衡,引入了分权和制衡制度。它象征着美国思想的演变,从完全不信任中央权威到承认中央权威对国家凝聚力和繁荣的重要性。

在战胜英国并实现独立后,最初的十三个州以及佛蒙特州迅速行动起来,通过各自的宪法确立了自己的主权和身份。每部宪法都是独一无二的,由每个州的社会、经济和政治特点雕琢而成。这些宪法充分体现了思想和文化的多样性,这也是这些新独立州的特点。然而,尽管这些国家刚刚获得独立并渴望自治,但问题很快就出现了。州与州之间的贸易纠纷、不稳定的货币、像谢斯(Shays)这样的叛乱以及外国干涉的威胁,都暴露了国家间合作时断时续且往往无效的制度的弱点。这些危机凸显了建立一个更加协调一致的结构来指导新生国家的必要性。

1787 年制宪会议

当时的政治思想家和领导人,如詹姆斯-麦迪逊、亚历山大-汉密尔顿和乔治-华盛顿都明白,年轻的共和国要继续存在,就需要一个更加统一的框架,同时尊重各州的自治权。因此,1787 年在费城召开的制宪会议不仅是对《邦联条例》不足之处的反应,还代表了在一个平衡的联邦政府领导下建立一个统一国家的远大理想。最终产生的宪法成功地融合了这些理想,建立了一个联邦制度,明确划分了国家政府和各州的权力,保证了新共和国的自由和稳定。它成为美国未来发展的持久基础,同时尊重每个州的独特身份。

美国宪法》的序言是一个简洁而有力的引言,阐述了起草这份建国文件的主要目的和愿望。其内容如下

"我们合众国人民,为了组成一个更完美的联盟,为了建立正义,为了确保国内安宁,为了提供共同防御,为了促进普遍福利,为了确保我们自己和我们的子孙后代享有自由的福佑,特制定并确立本《美利坚合众国宪法》"。

序言中的每一句话都蕴含着特定的意图:

- "组成一个更完美的联盟": 指各州之间需要更大的凝聚力和协作,这是从《邦联条款》的缺陷中吸取的教训。

- "建立正义 在全国范围内建立公正统一的法律体系,保障法律面前人人平等。

- "确保内部安宁": 保护公民免受内乱,保障国内和平。

- "共同防御: 确保国家安全,抵御外部威胁。

- "促进普遍福利":促进经济、社会和文化发展: 促进全体公民的经济、社会和文化进步与福祉。

- "确保我们自己和我们的子孙后代享有自由之福": 为今世后代保护和维护基本自由。

因此,序言不仅是对《宪法》的介绍,还为整部文件定下了基调和宗旨,勾勒出一个国家的集体愿景,旨在为所有公民实现这些理想。

在美国革命之后,美国作为一个新自由主权国家的集合体,正处于十字路口。每个州都制定了自己的宪法,并建立了一套政府制度,这套制度不仅反映了本州居民的政治倾向,也反映了他们的社会和文化价值观。这些宪法是激烈辩论和妥协的结果,借鉴了欧洲的各种传统和各州的独特经验。例如,宾夕法尼亚州采用了当时的进步模式,承认白人男性纳税人享有普选权。宾夕法尼亚州采用单一议会和合议制行政机构,力求减少权力集中,鼓励公民更广泛地参与。相比之下,马里兰州等州则保持着贵族化的社会和政治结构。那里的权力掌握在地主精英手中。土地所有者凭借其社会和经济地位,不仅对州长选举,而且对整个州的政治都产生了主导性影响。新泽西州提供了一个特别引人入胜的例子:它不仅赋予某些男性选举权,还赋予符合特定财产标准的女性选举权。这在当时是一个反常现象,表明了每个州在治理理念上的差异有多大。

这些差异在丰富了这个年轻国家的政治结构的同时,也加剧了各州之间的紧张关系。对有效协调、共同货币、统一国防和稳定贸易政策的需求很快变得显而易见。各个国家各自为政,有时甚至相互冲突,这对国家的统一和稳定构成了严峻挑战。正是在这种背景下,制定一部国家宪法成为当务之急。当时的领导人希望建立一个框架,在尊重各州主权的同时,建立一个强大的中央政府,能够应对和驾驭国家面临的复杂挑战。

美国诞生之初,各种政治制度和意识形态信仰林立。每个州都建立了自己的政府,通常是为了应对自身的文化、经济和地理特点。虽然这些不同的制度本身反映了殖民地的丰富经验和愿望,但当各州试图就全国性问题进行合作时,它们也带来了摩擦和复杂性。例如,国家间的贸易和货币问题有时会受到不同利益的阻碍。沿海国家可能倾向于征收关税以保护其商品,而边境国家则可能寻求促进与邻国的自由贸易。同样,如果没有一个强有力的中央机构来管理货币,各州就会发行自己的货币,从而导致混乱和经济不稳定。此外,外部威胁,无论是潜在的入侵还是外交条约,都需要协调一致的应对措施,而分散的政府无法有效做到这一点。除了实际问题外,理想也岌岌可危。开国元勋们渴望建立一个共和国,在这个共和国中,人权将受到保护,不受专制政府胡作非为的影响,同时确保同一政府有权为共同利益采取行动。个人自由与公共利益之间的这种微妙平衡是宪法辩论的核心。因此,1787年,在这些挑战和愿望的背景下,代表们聚集在费城起草美国宪法。他们的愿景是:建立一个有权处理国内和国际问题的联邦政府,同时尊重各州的权利和主权。这部宪法是妥协和远见的产物,它为一个国家奠定了基础,尽管这个国家的起源各不相同,但它渴望团结和共同的命运。

权利法案

权利法案》是《宪法》十项修正案中的第一项,于 1791 年通过,旨在保护公民的个人权利,防止政府滥用权力。权利法案》是美国宪法史上最重要的里程碑之一。事实证明,《权利法案》的制定对于消除反联邦主义者的担忧至关重要,他们担心新起草的《宪法》没有提供足够的保护,以防止中央政府权力过大。

虽然《宪法》规定了联邦政府的权力,但《权利法案》明确规定了政府不能做的事情,从而起到了制衡作用,确保公民的权利和自由得到保护。前十条修正案将美国最珍视的一些价值观编纂成法典。

- 言论、新闻、宗教和集会自由: 这些权利构成了第一修正案,是防止审查和宗教迫害的基本保障。

- 携带武器的权利: 经常引起争议的第二修正案允许公民拥有武器,但这一权利的确切范围和限制仍然存在争议。

- 禁止安置军队: 第三修正案禁止政府在和平时期强迫公民安置士兵。

- 防止不合理的搜查和扣押: 第四修正案规定,搜查或扣押财产必须有搜查证,从而保护了公民的隐私。

- 审判权: 第五、第六和第七修正案列举了这些权利,包括不自证其罪的权利、迅速公开审判的权利以及在刑事诉讼中获得陪审团的权利。

- 防止残忍和不寻常的惩罚: 第八修正案禁止此类做法,即使在定罪后也要保护被告的权利。

- 保护未明确列举的权利: 第九和第十修正案规定,《宪法》未提及的权利由公民保留,《宪法》未授予美国的权力由各州保留。

多年来,《权利法案》已成为美国对个人自由承诺的有力象征,既为法学提供了路线图,也为国家提供了应始终为之奋斗的理想。

权利法案》的局限性

权利法案》标志着 18 世纪末在保护个人自由方面迈出了根本性的一步。然而,其最初的应用反映了当时社会政治环境中固有的平等和正义的缺失。奴隶制问题主导了《宪法》起草和后续修正案的辩论。一些开国元勋坚决反对奴隶制,但团结各州的当务之急要求他们做出妥协。经过近 80 年的时间、一场毁灭性的内战以及 1865 年第 13 修正案的通过,才正式结束了奴隶制。美利坚共和国的早期公然忽视了美洲原住民的权利。从毁约到强迫同化政策,如 "泪水行军",他们的历史充满了不公正。经过几十年的要求,他们的权利才开始得到承认和尊重。最初,妇女在很大程度上被排除在公民权利之外,包括投票权。正是 20 世纪初的女权运动促成了 1920 年第 19 项修正案的通过,赋予了她们这一基本权利。然而,妇女在各个领域的平等问题仍然是争论和动员的核心问题。美国权利和自由的扩大是一个长期进步过程的结果。虽然《权利法案》奠定了坚实的基础,但它更多的是一个开端,而不是结论。多年来,通过社会运动、持续努力和宪法修订,美国一直在努力将这些权利扩展到所有公民。

在 1787 年制定美国宪法时,最初的 13 个州都存在奴隶制,但在采纳奴隶制并将其融入这些州的生活方面存在很大差异。在北方,一些州已经开始放弃奴隶制。例如,佛蒙特州于 1777 年宣布独立,成为第一个禁止奴隶制的州。随后,马萨诸塞州和新罕布什尔州也很快废除了奴隶制。其他州虽然没有立即废除奴隶制,但也试图逐步结束这种做法。例如,宾夕法尼亚州于 1780 年通过了一项法律,保证任何在该日期之后出生的人都享有自由,从而逐步废除了奴隶制。纽约州也遵循类似的轨迹,通过法律逐步废除奴隶制,直至 1827 年彻底废除。然而,南方各州的情况却截然不同。在这些地区,如南卡罗来纳州、佐治亚州和弗吉尼亚州,奴隶制在社会和经济上都根深蒂固。这些州的农业经济以烟草、大米和其他密集型作物的生产为基础,严重依赖奴隶劳动。在这些地区,废除奴隶制的想法不仅不受欢迎,而且被视为对其生活方式和经济的生存威胁。各州在对待奴隶制问题上的这种差异在起草宪法的过程中造成了紧张和妥协,为未来的冲突奠定了基础,最终导致了 1861 年的美国内战。

尽管在殖民地时代和后殖民时代存在着奴隶制,但值得注意的是,在公民权利方面,并非所有州都对黑人采取了统一的做法。除了南卡罗来纳州、佐治亚州和弗吉尼亚州在法律上剥夺了黑人的公民权之外,其他各州都没有明确的法律规定阻止黑人参与政治生活。然而,法律上的不排斥并不一定能转化为政治参与上的真正平等。在现实中,无论是法律规定还是地方习俗,都有许多障碍阻碍他们行使公民权利。财产要求、令人望而却步的人头税和识字测试是限制黑人投票权的诸多障碍之一。这些做法虽然在法律条文中没有明确针对黑人,但实际效果是将黑人排除在政治参与之外。还应该强调的是,这些障碍不仅是由国家强加的,而且往往得到白人公民实施的暴力和恐吓的支持和强化。威胁、暴力,有时甚至私刑,使许多黑人不敢尝试登记投票或去投票站投票。因此,尽管一些州没有明确剥夺黑人的选举权,但限制性法律、歧视性习俗和暴力行为的结合确保了大多数黑人实际上仍处于政治边缘。这种状况持续了几十年,甚至在南北战争结束后,直到二十世纪的民权运动。

在美国宣布独立后,奴隶制作为一种制度在美国南方变得更加根深蒂固。该地区越来越依赖农业经济,尤其是棉花种植,这需要大量廉价劳动力。1793 年轧棉机的发明加强了这种依赖,它使棉花生产更加有利可图,从而增加了对奴隶的需求。因此,虽然南方的奴隶数量通过进口(直到 1808 年禁止进口)和自然增长迅速增加,但北方和南方对奴隶制的态度却大相径庭。北方随着工业化经济的发展,对奴隶制的依赖有所减少。北方许多州要么在革命后直接废除奴隶制,要么立法逐步解放奴隶制。然而,南方认为奴隶制不仅是经济支柱,也是其社会和文化特征不可分割的一部分。南方制定了越来越严格的法律来控制和奴役奴隶,对奴隶制的任何争论或反对都遭到严厉镇压。南北之间日益加剧的分歧反映在全国性的政治辩论中,尤其是在新州加入联邦以及这些州是否会成为奴隶制州的问题上。1820 年的《密苏里妥协法案》、1850 年的《逃奴法案》和 1857 年的 "德雷德-斯科特案 "等事件加剧了这种紧张关系。最终,这些不可调和的分歧,再加上其他政治和经济因素,导致了 1861 年南北战争的爆发。战争不仅是奴隶制问题的结果,无疑也是其主要催化剂。

内战的宪法后果

美国内战在 1861 年至 1865 年间肆虐全国,是美国历史上最动荡的时期之一。从根本上讲,这场暴力冲突是工业发达、废除奴隶制的北方与农业发达、拥有奴隶的南方之间的对立,其核心是奴隶制和州权利的紧张关系。北方打着联邦的旗号,决心维护国家统一,结束奴隶制。然而,南方则为其所认为的自决权和维护与奴隶制密切相关的 "生活方式 "而战。1865 年联邦的胜利不仅维护了美国的领土完整,还为第 13 修正案的通过铺平了道路,最终废除了奴隶制。然而,战争的结束并不标志着国家挑战的结束。南方遭到了严重破坏,不仅基础设施被摧毁,经济模式也因废除奴隶制而过时。战后的重建时期试图重建南方,让获得解放的非裔美国人作为正式公民融入社会。但这是一个充满挑战的时期:前奴隶主想方设法维持权力,"吉姆-克罗 "法案的出台压迫了新获得自由的人口。此外,国家的重建不仅是物质上的,也是道德和意识形态上的。必须愈合一个分裂国家的创伤,找到共同点,在此基础上继续前进。这项艰巨的任务耗时数十年,而引发战争的一些种族和社会问题至今仍在美国社会引起共鸣。

内战后的重建时期被认为是美国历史上争议最大的阶段之一。1865 年战争结束后,林肯遇刺身亡,安德鲁-约翰逊(Andrew Johnson)总统继任,他肩负着决定如何将叛乱的南方各州重新纳入联邦的重任。约翰逊本人也是南方人,他对南方的态度比同时代的许多北方人更为宽容。他设想在尽量不破坏南方各州社会经济结构的情况下,使其迅速重新融入联邦。因此,他的重建计划对前邦联成员实行大赦,允许他们在南方重新获得政治控制权。此外,虽然废除了奴隶制,但约翰逊的计划并未采取任何强有力的措施来保障非裔美国人的公民权利或政治权利。然而,国会中的许多人,尤其是激进的共和党人,认为这种做法过于宽松。他们担心,如果没有坚实的重建和对非裔美国人权利的保护,内战期间取得的成果将只是暂时的。总统与国会之间的紧张关系最终导致约翰逊遭到弹劾,尽管他并未被免职。在激进共和党人的压力下,国会通过了更严厉的法律。其中包括保护黑人权利的法律,如第 14 条修正案,该修正案保证所有在美国出生或入籍的人,不论种族或前奴隶身份,都能获得公民身份。在这段激进的重建时期,联邦军队驻扎在南方,以确保改革得以实施,并保护非裔美国人的权利。然而,1877 年重建结束后,这些军队撤离,被称为 "吉姆-克劳 "法的歧视性法律卷土重来,这些法律确立了合法的种族隔离制度,在近一个世纪的时间里剥夺了许多非裔美国人的公民权利和政治权利。

南北战争后的重建时期标志着美国宪法史上一个深刻的转折点。面对冲突留下的伤痕和奴隶制根深蒂固的不平等,联邦政府认识到有必要采取果断干预措施,保障前奴隶的权利,建立一个真正统一的国家。第 13、14 和 15 条修正案的通过是对这一危机最重要的回应之一。1865 年批准的第 13 条修正案结束了奴隶制,为自由的新时代奠定了基础。然而,仅仅结束奴隶制还不足以确保平等;必须承认前奴隶是正式公民。这就是 1868 年批准的第 14 条修正案的作用所在。该修正案通过保障公民权和提供法律下的平等保护,力图在南方各州的歧视性法律面前保护非裔美国人的权利。最后,1870 年批准的第 15 项修正案旨在通过明确禁止基于 "种族、肤色或以前的奴役状况 "的歧视,确保非裔美国人的选举权。这一保障至关重要,因为如果没有它,新获得的自由和公民身份可能会因投票站的歧视性做法而受到损害。这些修正案不仅仅是对内战的回应;它们反映了对美国能够和应该成为什么样的国家的更广泛愿景。通过将这些基本权利载入《宪法》,政府试图为一个不断发展的国家建立一个坚实的框架,在这个框架内,所有公民,无论其背景如何,都可以在建设一个 "更加完美的联邦 "中发挥作用。

费城制宪会议

1787 年费城制宪会议是美国历史上最重要的事件之一,它为管理美国至今的政府结构和原则奠定了基础。这次大会虽然由一群白人精英主导,但其观点和利益却多种多样,反映了当时的社会政治紧张局势。不可否认,近三分之一的代表拥有奴隶这一事实影响了关于政府结构和公民权利的讨论。奴隶制在许多州的社会和经济中根深蒂固,拥有奴隶的代表们往往决心保护自己和本州的个人利益。

大会上最激烈、最具争议的辩论之一是 "五分之三的妥协"。它规定,就确定代表权和税收而言,奴隶将被算作一个人的 "五分之三"。这一妥协使奴隶制各州在国会中拥有更多的代表权,增强了它们的政治力量。此外,政府结构本身也是争论的焦点。代表们分为两派,一派支持强大的中央政府,另一派则主张州政府强大,中央政府有限。最终妥协的结果是建立了两院制的立法机构(众议院和参议院),平衡了大州和小州之间的权力。最后,选举权问题也是讨论的核心。在普遍使用财产标准来决定投票资格的时代,大会将这一决定权留给了各个州。这种做法导致了各种各样的选举权政策,一些州随着时间的推移逐渐将选举权扩大到更多的公民。因此,制宪会议是理想、经济利益和实用主义的复杂组合。参加制宪会议的人们意见并不一致,但他们成功地制定了一个框架,不仅使各州团结起来,而且为国家在随后几个世纪的发展和演变奠定了基础。

费城制宪会议就投票权问题展开了激烈的辩论。当时,只有土地所有者才有投票权的观点被许多人广泛接受,因为他们认为这些人在社会中拥有稳定而持久的利益,因此最有能力做出有利于社会的明智决定。这一观点的背景源于英国的传统,即选举权在历史上与土地所有权相关联。然而,其他代表认为,投票权应扩展至其他公民。他们认为,将选举权仅限于土地所有者有悖于《独立宣言》中规定的原则。如果 "人人生而平等 "并享有 "生命权、自由权和追求幸福的权利",那么为什么这一原则不能转化为更普遍的选举权呢?奴隶问题使情况变得更加复杂。虽然《独立宣言》谈到了平等,但它是在奴隶制广泛存在的社会中写成的。对许多人来说,平等和自由的理想与奴隶制的现实之间存在着认知上的偏差。在起草宪法的过程中,"人人生而平等 "这一论断是否包含奴隶这一问题在很大程度上被回避了,从而导致了五分之三妥协等折衷方案。最终,大会将选举权问题留给了各个州。这一决定使得年轻的国家政策多样化。一些州逐渐减少或取消了对财产的投票要求,扩大了选民范围,而另一些州则几十年来一直保持着更严格的限制。平等和自由的理想与 18 世纪晚期美国的社会和经济现实之间的矛盾不断引发争论和冲突。经过数十年和许多社会运动才开始弥合理想与现实之间的差距。

沉默、让步与 1787 年宪法的成就

背景和序言

美国宪法具有非凡的生命力,在长达两个多世纪的时间里,它指引着美国不断应对社会、政治和经济变革的挑战。宪法的强大部分源于其设计:宪法是本着妥协精神起草的,反映了对当时各州及其公民不同利益和关切的认可。开国元勋们预见到了未来不可预见的事件,明智地避免了强加过于僵化的指令。相反,他们制定了一份文件,由于其刻意的模糊性,该文件允许多种解释,以适应不断变化的情况。这种灵活性得益于几个关键机制。首先,尽管文本可以修改,但修改过程需要达成重大共识,从而确保只有深有感触的修改才能被采纳。其次,作为宪法的一项基本原则,三权分立确保了政府行政、立法和司法部门之间的平衡。这种平衡防止任何一个机构获得绝对权力,并强化了所有机构都在法治下运作的理念。最后,美国最高法院在这一动态中占据核心地位,是宪法解释的最终仲裁者。最高法院的裁决不断完善和澄清宪法文件的范围,使法学能够适应不断变化的社会。因此,得益于宪法起草者的开明构想和这些适应机制,宪法仍然是美国民主赖以生存的坚实基础。

美国宪法》以令人难忘的 "我们人民 "开篇,提出了建立一个合法性直接来自人民的政府的崇高目标。这是一个强有力的开端,宣称新国家将由其公民的集体愿望而非君主制或占统治地位的精英来指导。然而,"人民 "这一概念本身却处于灰色地带,文本中没有具体说明,因此产生了不同的解释。这种矛盾性反映了国父们有意做出的妥协。1787 年,代表们在 "包容 "问题上存在着强烈的紧张关系和根本分歧。文本没有提供一个可能会疏远某个派别的精确定义,而是保持了回避的态度。宪法中对奴隶制的处理是这种和解方式的另一个例子。虽然 "奴隶制 "一词本身从未被提及,但它被间接地纳入了文件。五分之三的妥协等机制默认了奴隶制的存在和延续,主要是为了确保奴隶制在文化和经济上都根深蒂固的南方各州对宪法的遵守。归根结底,这些妥协既揭示了起草者的务实愿景,也揭示了新国家内部的深刻分歧。他们小心翼翼地驾驭着这道山脊,希望为一个更加稳定和持久的联邦奠定基础。

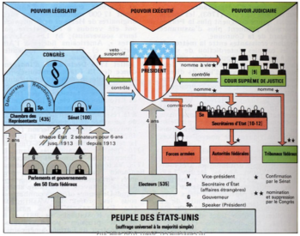

宪法和美国联邦政府的结构

美国宪法》是美国联邦政府结构的基石,确立了指导国家的基本原则。它以联邦制原则为基础,这一原则在国家政府和各州政府之间分配权力。在这一结构的核心中,每个州都有自己的宪法,为自己的政府提供了一个框架,并允许各州根据自己的需要和偏好对各种问题进行立法。例如,尽管联邦宪法规定了公民的基本权利,但这些权利往往由各州自行规定和阐述。此外,每个州都有权定义自己的公民身份标准,因此公民的权利和责任可能会因居住在加利福尼亚州、得克萨斯州还是纽约州而有所不同。中央权力和各州权利之间的这种平衡提供了必要的灵活性,使美国的文化和社会经济多样性得以蓬勃发展。从本质上讲,联邦制创造了一个马赛克,其中每个州都可以根据自己的特点行事,同时又是一个统一的国家实体的组成部分。

美国《宪法》的设计是明智的,旨在确保政府内部权力的均衡分配,从而避免潜在的权力滥用,保护公民的自由。分权原则是这一设计的核心。有权制定法律的立法权分为两院。一方面是众议院,各州的代表根据其人口数量而定。这确保了人口最多的州的利益得到考虑。另一方面,参议院确保每个州,无论大小,都有平等的发言权,每个州有两名参议员。这种双重结构旨在根据各州的面积和人口来平衡各州的利益,确保各级代表的公平性。除立法部门外,还有负责实施和执行法律的行政部门和负责解释法律的司法部门。这些职能的明确分工确保了任何一个部门都不能支配其他部门,从而形成了一个相互制衡的体系。这一制度是美国民主的基石,确保政府的行为始终符合其服务对象的利益。

在 1787 年的制宪会议上,北方和南方各州之间的紧张关系显而易见。一个核心问题是如何计算人口以确定国会中的代表权。五分之三的妥协 "就是在这种紧张关系中产生的,它允许南方奴隶州增加其政治影响力。根据这一妥协方案,就代表权而言,每个被奴役者将被视为相当于五分之三的自由人。这保证了南方各州不仅可以根据其自由人口,还可以根据其奴隶人口的一部分增加代表权。北方各州接受了这一妥协,作出了重大让步,旨在维护年轻的美国脆弱的统一。然而,这一妥协具有深远的道德影响。虽然它给予了南方各州在国会中更大的发言权,但也降低了奴隶的人的价值,将他们视为不完整的人。随着时间的推移,这一条款受到广泛批评,被视为宪法道德结构上的一个污点。它提醒人们,即使是在建立一个以自由和平等为基础的国家时,也会以牺牲人权为代价做出妥协。

选举团

在制宪会议上,代表们对暴政的阴影记忆犹新。他们刚刚摆脱英国君主制的桎梏,决心建立一个能够保护美国免受滥用权力之害的治理体系。这引发了关于行政机构作用,尤其是总统权力范围的激烈辩论。一方面,人们认识到需要一个强有力的行政人物,能够在危机时刻迅速做出决定,并在国外代表国家。这导致一些代表主张总统拥有广泛的权力,让人想起君主立宪制的特权。然而,其他代表则对权力过度集中深表怀疑,担心权力过大的总统可能会变成君主或暴君。折中方案设计得很巧妙。总统将被授予重大权力,如否决立法的权利,这将使他能够制衡国会的权力。然而,为了避免权力过于集中,副总统将不会由人民直接选举产生。相反,由选举人组成的选举团将负责选举总统和副总统。这一制度在人民与国家最高职位的选举之间起到了一定的缓冲作用,反映了对 "多数人暴政 "的担忧以及选举过程中调解的重要性。此外,副总统还有一个至关重要的额外角色,即在参议院出现僵局时充当决定性一票,从而加强权力制衡。这一微妙的制度反映了开国元勋们的谨慎,他们在建立新共和国的过程中寻求权力与克制之间的平衡。

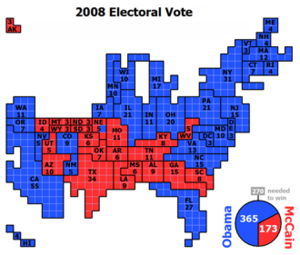

选举团是美国民主制度中最独特的机构之一,经常成为辩论和争议的主题。选举团最初是作为国会投票选举总统和民众直接投票选举总统之间的一种折衷方案,它反映了国父们对 "多数人暴政 "的不信任。他们认为,将决定权委托给一组选举人将提供额外的调解,确保总统由知情和有献身精神的个人选出。在选举团结构中,每个州获得的选举人数量与其在国会的代表总数(众议院+参议院)相等,这也是平衡大州和小州之间权力的一种方式。因此,即使人口最少的州也至少有三名选举人。随着时间的推移,为了适应美国政治现实的变化,有必要进行修改。第 12 项修正案纠正了原有制度中的一个明显缺陷。最初,得票最多的候选人成为总统,得票第二多的候选人成为副总统。1800 年,托马斯-杰斐逊(Thomas Jefferson)和亚伦-伯尔(Aaron Burr)获得的选票数相等,造成僵局,这成为一个问题。因此,修正案将这两个职位的选票分开,确保选举人明确投票选举总统和副总统。第23条修正案反映了承认美国首都哥伦比亚特区居民的公民身份和选举权的愿望。虽然这些居民生活在美国政治的中心,但在批准该修正案之前,他们在总统的选择上没有发言权。多年来,选举团一直是许多批评和改革建议的主题。一些人主张废除选举团,改由民众直接投票决定,另一些人则试图对其进行改革,以更好地反映人民的意愿。尽管如此,选举团的存在仍然决定着总统竞选活动的进行方式和候选人的选举策略。

美国的选举团制度很独特,甚至经常被一些美国公民误解。实际上,当选民在总统选举中投票时,他或她实际上是在为一组承诺支持特定候选人的选举人投票,而不是直接为候选人本人投票。几乎所有州都实行 "赢家通吃"。这意味着,即使一名候选人仅以微弱优势赢得多数选票,他或她也将获得该州的所有选举人票。只有内布拉斯加州和缅因州偏离了这一规则,根据各选区的结果分配部分选举人。这种制度有两方面的影响。首先,它造成了一种趋势,即在坚定地与某一党派保持一致的州(例如,民主党的加利福尼亚州或共和党的俄克拉荷马州),候选人并不需要真正参加竞选活动,因为结果在很大程度上是可以预料的。其次,这凸显了 "摇摆州 "的重要性--这些州的选民严重分裂,选举结果难以预料。这些州正成为候选人的必争之地,他们在那里花费了过多的资源和时间。佛罗里达州、俄亥俄州和宾夕法尼亚州等州在每个选举周期都会成为关注的焦点,因为这些州向某一方的倾斜可能会决定选举的结果。这种动态受到一些人的批评,他们认为这使少数几个州对选举产生了不应有的影响,忽视了美国其他地区的关切。美国的选举制度很独特,多年来引起了很多讨论,尤其是选举团机制。美国公民在总统选举中投票时,并不直接投给自己心仪的候选人,而是投给一组选举人,再由他们投票选举总统。大多数州都采用 "赢家通吃 "的方法,即赢得本州普选的候选人赢得本州所有的选举人。不过,缅因州和内布拉斯加州采用了另一种方法:"国会选区法"。根据这种方法,赢得该州总普选票数的候选人将获得两名选举人。剩余的选举人(根据该州的国会选区数量)则单独分配给每个选区的获胜者。这意味着,从理论上讲,这些州的选举人票可能会被候选人瓜分。这一区别至关重要,因为它凸显了不同州是如何处理选举过程的。采用 "赢家通吃 "方法的州即使以微弱优势赢得州选举,其选举人票也可能全部投给一名候选人,而缅因州和内布拉斯加州则提供了一个在其境内代表不同意见的机会。虽然这种方法只在两个州使用,但它凸显了美国选举过程的多变性和复杂性。

尽管选举团的初衷是平衡各州之间的选举权力,防止人口最多的州过度主导,但正是由于这些原因,选举团已成为争议的根源。争论的焦点之一是,这一制度可以允许候选人在没有赢得普选的情况下成为总统,过去也曾出现过这种情况。这正是 2000 年小布什和阿尔-戈尔之间颇具争议的选举中发生的情况。戈尔以微弱优势赢得了普选,但在佛罗里达州的计票问题上打了一场官司之后,布什被宣布在这个关键州获胜,从而获得了多数选举人票,并因此当选总统。这引发了激烈的争论和对选举团制度的质疑,因为许多人不明白候选人怎么可能在没有赢得普选的情况下成为总统。类似的情况还发生在 1876 年、1888 年和 2016 年的选举中。这些选举虽然时间间隔较长,但却加强了改革或废除选举团制度的呼声。该制度的捍卫者认为,它保护了小国的利益,确保了代表权的平衡;而批评者则认为,它不民主,会给某些选民带来不相称的发言权。关于选举团是否仍有意义或是否需要改革的问题,是美国政治领域一直存在的争论。这场辩论提出了关于民主本质以及如何在选举过程中最好地公平代表公民的根本问题。

选举团制度是美国选举程序的一个独特之处。该制度由美国开国元勋建立,旨在平衡各州的代表权,确保人口较少的州不会被人口较多的州边缘化。开国元勋们还担心将选举的决定权直接交到群众手中,担心会出现 "多数人的暴政"。因此,选举团被设想为民众投票和总统选举之间的一种调解人。每个州分配到的选举人数量与其在国会中的众议员和参议员总数相等。因此,即使人口最少的州也至少有三名选举人。根据 "赢者通吃 "的规则,当候选人在一个州(缅因州和内布拉斯加州除外)赢得普选时,他或她通常会赢得该州的所有选举人。候选人在没有获得多数民众选票的情况下赢得选举的可能性引起了很多争议。当这种情况发生时,例如在2016年,改革或废除选举团的呼声再次高涨。该制度的捍卫者认为,它保护了人口较少州的利益,并确保了国家层面的均衡代表性。而批评者则认为,这一制度已经过时,不能体现每个公民都有平等发言权的民主原则。尽管关于选举团的相关性的争论仍在继续,但它仍然是美国选举进程的核心要素,并继续影响着总统竞选中候选人的策略。

司法权

建立强有力的司法机构是 1787 年制宪会议上做出的具有远见卓识的决定之一。美国最高法院在这一司法权中占据核心地位。随着时间的推移,它已成为公民宪法自由的重要守护者,同时也是政府各部门和各州之间法律纠纷的最终仲裁者。最高法院大法官由总统任命,经参议院批准,这保证了大法官的民主遴选程序。他们的终身任期强化了这样一种理念,即这些法官一旦就职,就应免受当前政治动荡的影响。这种保护使他们能够全心全意地解释法律,而不必担心遭到报复或受到外界影响。法院审查立法机关或行政机关的行为并在必要时宣布其无效的能力--这种做法被称为司法审查--是美国民主运作的根本。正是通过这一机制,法院才能确保政府的所有行为都符合宪法,从而维护美国建国文件的完整性。法院的设计以及赋予它的权力和责任体现了美国制衡制度的精髓。这一制度确保政府的任何部门都不会获得绝对的权力,从而保护公民的权利和自由,并确保作为建国基础的民主原则的持久性。

五分之三的妥协是制宪会议上最具争议的决定之一。它反映了当时代表们的深刻分歧和实际关切,同时也显示了奴隶制在年轻的美国国家的社会、经济和政治结构中的根深蒂固程度。这一妥协的细节主要是经济和政治方面的,而不是道德方面的。依赖奴隶制的南方各州希望在确定其在国会中的代表人数时,将其全部奴隶人口计算在内。这当然会大大增加他们的政治权力。奴隶制不那么普遍的北方各州反对这样做,认为如果奴隶没有选举权,不被视为正式公民,他们就不应该被全部计入代表人数。因此,五分之三的妥协方案试图在这些不同的立场之间取得平衡。然而,它的间接后果是在许多年里加强了蓄奴州的政治权力,使它们对总统、国会乃至国家政治拥有不成比例的影响力。同样重要的是要注意到,这一妥协以及宪法中使奴隶制永久化的其他条款(如 1808 年之前不禁止奴隶贸易的条款)经常被作为原始宪法存在严重缺陷的证据。这些条款反映了当时为建立一个稳定的联邦而必须面对的现实和作出的妥协,但也表明奴隶制与美国的建国有着千丝万缕的联系。奴隶制问题及其引发的紧张局势最终导致了 19 世纪 60 年代的美国内战。

美国宪法》虽然被公认为重要的建国文件,但其妥协的特点反映了 18 世纪美国社会的深刻分歧,尤其是围绕奴隶制问题的分歧。具体条款,如《逃奴条款》,规定任何逃跑的奴隶都必须归还其主人,将奴隶制国有化。这意味着即使已经废除奴隶制的国家在法律上也有义务参与奴隶制的延续。这些妥协产生了几大影响。首先,它们通过将奴隶制纳入宪法文件本身,使奴隶制合法化并得到强化。其次,这些安排加剧了北方和南方各州之间的地区紧张局势,这种紧张局势最终导致了美国内战。即使在废除奴隶制之后,这些妥协的后果依然存在,奴隶的后代在整个 20 世纪都在为争取自己的公民权利而斗争。今天,人们常常挑出原始宪法中的这些条款,以强调国家的平等和自由理想与奴隶制现实之间的不一致。然而,重要的是要认识到宪法是一份有生命力的文件。随后的修正案,如第 13、14 和 15 条修正案,试图纠正最初的一些不公正现象。但这些妥协对美国历史和社会的影响仍然深远而不可磨灭。

奴隶制问题

在 1787 年的制宪会议上,北方和南方各州在奴隶制问题上关系紧张,因此有必要做出妥协,以建立一个更强大的联邦。为了争取南方对新宪法的支持,北方各州同意了 "逃奴条款"。该条款规定,即使是那些已经废除奴隶制的州,也有义务将任何逃跑的奴隶交还给他们在南方的原主人。这一旨在安抚南方各州的条款显然与美国革命所宣扬的自由和平等的理想相悖。它不仅加强了奴隶制在法律上的合法性,而且使被奴役者更难逃往北方自由州过上更好的生活。这一妥协虽然在当时对新国家的形成具有战略意义,但也表明了以国家统一的名义牺牲基本原则的程度。

在 1787 年的制宪会议上,除了在奴隶制问题上的其他妥协之外,北方各州还同意将禁止从非洲进口奴隶的禁令推迟到 1808 年。这一决定是为了确保南方各州对新宪法的支持,但却产生了深远而持久的影响。它使跨大西洋奴隶贸易又持续了二十年,导致更多的非洲奴隶涌入。甚至在 1808 年之后,尽管与非洲的奴隶贸易被禁止,但日益活跃的国内奴隶贸易仍在继续。南方各州继续在国内买卖和贩卖奴隶,特别是向西部和南部下游地区贩卖奴隶,因为那里的种植园扩张需要大量劳动力。直到 1865 年最终废除奴隶制,这种国内贸易才宣告结束。

北方各州在 1787 年制宪会议上接受的妥协方案凸显了年轻的美国共和国在奴隶制问题上存在的紧张和矛盾。虽然自由和平等的理想被宣布为新国家的基础,但它们与维持和容纳令人憎恶的奴隶制做法并存。这些协议揭示了政治、经济和社会问题的复杂性,而这些问题正是起草宪法时所做出的每项决定背后的原因。它们还说明了试图将利益和文化如此不同的各州联合起来所固有的挑战。北方各州虽然有许多在道义上反对奴隶制,但为了确保新联盟的凝聚力和可行性,它们往往准备做出让步。这些妥协虽然促进了《宪法》的批准并确保了一定程度的初期稳定,但却留下了一些根本性的问题没有得到解决,而这些问题最终只能在几十年后的一场血腥内战中找到答案。

联邦政府与各州之间的紧张关系

1787 年制宪会议是一场激烈辩论和关键谈判的舞台,远远超出了奴隶制问题的范畴。这些讨论的核心是另一个根本性难题:如何平衡中央联邦政府与各州之间的权力。这是一项艰巨的挑战,既需要一个强大的中央政府来管理一个新兴国家,又需要各州保持自治和主权。税收问题尤其具有争议性。根据《邦联条款》的经验,中央政府缺乏资金,只能依靠各州的自愿捐款,因此显然需要做出改变。然而,人们对赋予联邦政府加税的权力表示担忧。许多人担心这会赋予中央政府过大的权力,有可能形成一种专制权力。小州尤其担心。他们担心,如果代表权和税收以人口或财富为基础,就会被人口更多、更富裕的大州的利益所支配。这些担忧促成了著名的《康涅狄格妥协法案》或《大妥协法案》,该法案建立了一个两院制国会:众议院和参议院,前者的代表权以人口为基础,后者的代表权以人口为基础。最终,大会成功达成了一系列妥协,虽然并不完美,但为一部持久的宪法奠定了基础。它在中央权力和各州权利之间达成了微妙的平衡,这种紧张关系至今仍影响着美国政治。

美国宪法的批准之路并非一帆风顺。1787年费城会议之后,尽管许多人支持新宪法,但显然也有强烈的反对意见。被称为 "反联邦主义者 "的人担心新宪法会赋予中央政府过多的权力,从而牺牲各州和个人的权利。对他们来说,如果没有明确的保护措施,新政府就有可能变得像殖民地在美国革命期间所反对的政府一样专制。为了回应这些担忧,也为了争取对批准宪法的支持,人们同意,一旦宪法获得批准,第一届国会将提出一系列修正案来保护个人权利。这些修正案就是我们今天所熟知的《权利法案》。宪法》的前十项修正案统称为《权利法案》,于 1791 年获得通过。它们保障了一系列个人权利,如言论自由、宗教自由和新闻自由,以及免受不公平法律诉讼的保护。这些权利已成为美国政治和法律文化的基础。通过在《宪法》中加入《权利法案》,开国元勋们不仅寻求保障美国公民的基本自由,还试图减轻反联邦主义者的恐惧和焦虑。这一姿态在确保《宪法》获得批准以及为年轻的美国共和国建立稳定持久的政府方面发挥了至关重要的作用。

这些修正案是《宪法》中的前十条修正案,于 1791 年加入,赋予个人言论、宗教、新闻、集会自由以及公平审判权等权利。它们还限制了政府的权力,规定了三权分立和联邦制。

权利法案

The Bill of Rights, enshrined in the first ten amendments to the US Constitution, remains a vital component of the American legal system. Ratified in 1791, it grew out of concerns that individual rights and liberties were not adequately protected in the original Constitution.

- First Amendment: Guarantees fundamental freedoms such as freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly and the right to petition the government.

- Second Amendment: enshrines the right of citizens to keep and bear arms.

- Third Amendment: Protects citizens from being forced to house soldiers on their property in times of peace.

- Fourth Amendment: Provides protection against unwarranted searches and seizures and requires that a search warrant be specific and substantiated.

- Fifth Amendment: Provides a series of judicial protections: protection against self-incrimination, against double jeopardy for the same crime, and guarantees the right to a fair trial.

- Sixth Amendment: Guarantees everyone charged with a crime the right to a speedy, public and impartial trial, as well as the right to counsel.

- Seventh Amendment: In civil litigation involving significant amounts of money, the right to trial by jury is guaranteed.

- Eighth amendment: Cruel or excessive punishment is prohibited.

- Ninth amendment: This text reiterates that the rights enumerated in the Constitution are not exhaustive and that other rights, although not specified, are also protected.

- Tenth Amendment: This establishes the principle that powers not assigned by the Constitution to the federal government, nor denied to the States, remain with the States or the people.

In this way, the Bill of Rights acts as a shield against possible encroachments by the federal government, guaranteeing and strengthening the protection of the individual rights and freedoms of American citizens. It has been and remains a constant point of reference in debates on the scope and limits of government powers in the United States.

The U.S. Bill of Rights serves as a solid guarantee for the fundamental freedoms of citizens. These freedoms include:

- Freedom of religion: Thanks to the First Amendment, every individual has the right to practice the religion of his or her choice, or to follow no religion at all. In addition, the government may not establish a state religion or interfere with the practice of religion.

- Freedom of expression: The First Amendment also protects freedom of expression, ensuring that every citizen has the right to speak without fear of censorship or government reprisal.

- Freedom of the press: This same amendment ensures freedom of the press, allowing the publication of information and ideas without government censorship.

- Freedom of peaceful assembly: The right to assemble peacefully to exchange and defend ideas is also protected by the First Amendment.

- Freedom to petition: This right, also enshrined in the First Amendment, allows citizens to ask the government to intervene in a specific situation, or to revisit an existing law or policy.

- Right to bear arms: The often-debated Second Amendment guarantees citizens the right to keep and bear arms, generally interpreted as a means of self-defence and defence of the state.

- Protection against state abuse: Several amendments to the Bill of Rights aim to protect citizens from potential abuses by the state, the police and the judicial system. In particular, the fourth, fifth, sixth and eighth amendments guarantee protection against unjustified searches and seizures, the right to a fair trial, the right to a lawyer, and prohibit cruel or excessive punishment.

The Bill of Rights serves as a fundamental basis for the protection of individual liberties from potentially oppressive government actions. These rights and freedoms, at the heart of the American identity, continue to be the focus of much debate and judicial interpretation.

The Bill of Rights in the United States and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen in France are two founding texts which, although emanating from distinct historical and political contexts, bear witness to a shared desire to protect individual freedoms and define the principles of just governance. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted in 1789 during the French Revolution, proclaims the natural, inalienable and sacred rights of man. It affirms equality and freedom as universal rights, stating principles such as "men are born and remain free and equal in rights". It also advocates the separation of powers, the idea that the law is the expression of the general will, and the importance of freedom of opinion. On the other side of the Atlantic, the Bill of Rights was added to the US Constitution in 1791. It was designed as a safeguard against the potential abuse of power by the federal government. Its ten amendments cover a range of rights, including freedom of speech, press and religion, as well as protections against unwarranted search and seizure and the right to a fair trial. While both documents are fundamental to their respective countries, they are also the product of their particular circumstances. The French Declaration, for example, emanated from a context of revolution against an absolute monarchy, while the American Bill of Rights was born of the colonists' distrust of an over-powerful central government following their independence from British rule.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and the Bill of Rights in the United States are undoubtedly two major milestones in the history of human rights. However, they differ in scope and emphasis, reflecting the distinct social, political and philosophical contexts in which they were drafted. The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was part of the French Revolution, a period marked by a radical questioning of the old social and political order. This declaration is imbued with the ideas of the Enlightenment, in which the notion of the "citizen" occupies a central place. It establishes that sovereignty belongs to the people and that laws must reflect the "general will". It emphasises equality and fraternity as fundamental principles. It is a document that seeks to establish a framework for a new social order, in which the common good is at the forefront. The American Bill of Rights, on the other hand, was heavily influenced by the experiences of the American colonies under British rule and a distrust of a strong central government. The emphasis is on protecting individual rights against potential abuses by government. It is rooted in a tradition of classical liberal thought, valuing individual autonomy, private property and civil liberties. Each amendment is designed to protect the individual from the excesses of government, whether in the form of freedom of expression or protection from unwarranted search and seizure. So, while the French declaration aims to lay the foundations of a nation based on fraternity and equality, the American declaration is more focused on guaranteeing individual liberties in the context of a fledgling republic. These nuances reflect not only differences in political and philosophical ideals, but also in the challenges and aspirations specific to each nation at crucial moments in their history.

The US Bill of Rights was carefully crafted to protect citizens from potential abuses by government. This concern grew out of the colonists' previous experiences under British rule, where perceived tyrannical acts had often violated their individual rights. To ensure that the new American Republic would not repeat these mistakes, the founding fathers incorporated a set of amendments that would serve as a guardian of individual liberties. The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures, requiring a warrant issued on the basis of probative evidence to permit a search or seizure. This ensures that a citizen will not be subjected to unwarranted invasions of his or her privacy The Fifth Amendment offers a series of protections for those accused of crimes. These protections include the prohibition against self-incrimination, which means that an individual cannot be compelled to testify against themselves, and the protection against "double jeopardy", which prevents an individual from being tried twice for the same crime. The Sixth Amendment ensures that all those accused of a crime have the right to a speedy and public trial and to an impartial jury. It also guarantees the right of the accused to be informed of the charges against them, to have a lawyer to defend them and to confront the witnesses against them. These rights are essential to ensure that individuals are not unjustly imprisoned. Finally, the Eighth Amendment prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. This means that the punishment or treatment inflicted on convicted persons must not be inhumane or excessively severe in relation to the offence committed. Collectively, these amendments reinforce the principle that, in a free society, the rights and freedoms of the individual are paramount, and that a government can only restrict them with strong safeguards to protect against abuse. These provisions reflect the fundamental values of justice and liberty that underpin the American legal system.

The Bill of Rights in the United States and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen in France are two of the most influential founding documents in the history of human rights. They were drafted against a backdrop of major political revolutions and social change, and reflect the aspirations of their respective peoples for freedom, justice and equality. The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was born of the French Revolution, a moment of major upheaval that sought to put an end to the abuses of the Ancien Régime. It sets out universal principles of equality, liberty and fraternity, and laid the foundations for a nation based on respect for individual and collective rights. It asserts that all citizens are equal before the law, regardless of their status or origin, and has served as a model for many other declarations of rights around the world. On the other side of the Atlantic, the United States Bill of Rights was adopted shortly after the ratification of the US Constitution in 1791. It was born of the Founding Fathers' distrust of an overly powerful central government and their desire to protect individual liberties. Thus, the first ten amendments to the US Constitution guarantee a series of personal rights and limit the power of the federal government, offering robust protection against abuses of power. Although these documents were drawn up in different contexts and have different emphases, they share a common concern for the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms. Their influence cannot be underestimated; they have inspired generations of reformers, activists and legislators, and continue to shape debates on human rights worldwide.

The Second Amendment, adopted in 1791, has long been one of the most debated provisions of the US Constitution. Its interpretation has given rise to great controversy and intense debate, particularly in the context of gun violence in the United States. At the time the Constitution was ratified, there was a deep distrust of standing armies. Many American colonists feared that a powerful federal army could be used to oppress the people or overthrow states' rights. Militias, which were made up of ordinary citizens, were seen as a necessary counterweight to a regular army. In this context, the Second Amendment was designed to ensure that citizens had the right to own arms in order to serve in these militias.

The language of the amendment led to two major interpretations:

- The Militia Interpretation: Some argue that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to bear arms only in the context of participation in a militia. According to this interpretation, the individual right to own a firearm would be conditioned on service or affiliation with a militia.

- The Individualist Interpretation: Others argue that the Second Amendment guarantees an unconditional individual right to own firearms, regardless of militia membership.

Modern debates over the Second Amendment often focus on issues such as gun control, gun violence, and government regulation. With the rise of mass shootings in the US, the issue of gun control has become particularly urgent and polarising. In 2008, in District of Columbia v. Heller, the US Supreme Court ruled in favour of the individualist interpretation, affirming that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to possess a firearm for a legitimate use, such as self-defence, independent of service in a militia.

The Second Amendment is one of the few articles of the US Constitution that, despite its brevity, has generated a disproportionate amount of litigation, debate and controversy, largely due to its ambiguous nature. For much of American history, case law has focused primarily on the interpretation of the militia. Early Supreme Court decisions, such as United States v. Miller (1939), examined gun ownership through the prism of the militia. In this case, the Court ruled that a federal law banning certain firearms was not unconstitutional because the weapon in question (a sawed-off shotgun) had no obvious connection with the operation of a militia. However, the interpretation has evolved. The "District of Columbia v. Heller" ruling in 2008 marked a significant turning point. In this case, the Supreme Court for the first time explicitly recognised an individual right to own a firearm, irrespective of participation in a militia. This decision represented a fundamentally different interpretation from that of previous decades. Alongside the legal debates, public discussion of the Second Amendment also intensified. With the rise in mass shootings, many citizens, activists and legislators called for stricter gun control laws. On the other hand, many defenders of the right to bear arms see any attempt at regulation as a threat to their constitutional rights. Lobbyists like the National Rifle Association (NRA) on the one hand, and groups like Everytown for Gun Safety on the other, have played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and lobbying elected officials. The Second Amendment is a perfect example of how constitutional interpretations can evolve according to the socio-political context. What was once understood primarily as a collective right linked to the militia is now widely recognised as an individual right. However, the exact scope of this right, and how it measures up against public safety, remains an open and debatable question.

The US Constitution and Bill of Rights are often celebrated for their principles of equality, liberty and justice. However, when we consider the historical context, it is clear that these principles were not universally applied. The paradox of a fledgling nation that valued freedom while allowing slavery has left a deep mark on American history. Compromises such as the "three-fifths" clause (which counted each slave as three-fifths of a person for representation in Congress) and the slave trade clauses show that the original Constitution was far from entirely devoted to the principles of equality and justice. It was not until the 13th Amendment, adopted in 1865, that slavery was officially abolished in the United States. Similarly, women were not considered equal before the law when the Constitution was adopted. They could not vote and were often excluded from many spheres of public life. It was not until the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, that women gained the right to vote. And the fight for equal rights between the sexes continues to this day. The Constitution is a living document, subject to interpretation and amendment. Over time, amendments have been added to correct some of the most flagrant injustices in American history. In addition, Supreme Court decisions and changing societal norms have extended the reach of constitutional rights to previously marginalised groups. However, acknowledging the Constitution's imperfect and often contradictory origins does not diminish its value. On the contrary, it serves as a reminder that the principles of justice, equality and liberty require constant vigilance and a willingness to evolve to meet society's changing needs.

The US Constitution and Bill of Rights partly reflected the values and ideologies of the time, and the exclusion of certain groups, notably slaves and women, is a testament to these historical biases. The trajectory of the US Constitution, like that of many other constitutions around the world, is one of progression towards inclusion. The Constitution has been amended, interpreted and reinterpreted over the years to extend its protections to previously marginalised or excluded groups. The 14th Amendment, for example, was crucial in guaranteeing equality before the law, and the 19th Amendment extended the right to vote to women. However, these changes were not easy and were often the result of long, sometimes violent, struggles. These developments also demonstrate the importance of civic vigilance. Citizens must be active in defending and extending their rights. The history of the Constitution is therefore as much a history of progressive inclusion as it is a history of the struggle for that inclusion. Finally, it is essential to recognise that while the Constitution provides a framework, it is society and individuals who determine its meaning. Laws can change, but it is people and their values that dictate the direction of that change. By recognising the shortcomings and inadequacies of the past, we can strive to create a fairer and more equitable future for all.

Society in the early 19th century

Territorial expansion

During the 19th century, a wave of fervent expansion swept across the United States, propelled by the doctrine of "manifest destiny". This widely held belief held that the country was destined to expand "from sea to shining sea". The first major step in this direction was the purchase of Louisiana in 1803. For the sum of 15 million dollars, the country doubled its size by buying these vast tracts of land from France. This strategic acquisition included vital control of the Mississippi River and the key port of New Orleans. It was against this backdrop that the Lewis and Clark expedition began in 1804. Financed by the government, the aim of this adventure was to explore, map and claim these new western lands. At the same time, the mission aimed to establish peaceful relations with the Amerindian tribes while seeking a navigable route to the Pacific Ocean. However, this century of expansion was not limited to peaceful exploration. In 1812, war broke out with Great Britain, mainly due to maritime and territorial tensions. Although the War of 1812 did not result in significant territorial gains, it did consolidate national identity and strengthen American sovereignty. Later, in 1819, America turned its gaze southwards with the Treaty of Adams-Onís, annexing Florida from Spain. But it was the annexation of Texas in 1845, after its brief period as an independent republic following its rebellion against Mexico, that set the stage for a major conflict. Growing tensions with Mexico culminated in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848. This war resulted in the Mexican cession, giving the United States territories stretching from California to New Mexico. This period of rapid expansion shaped the United States into a continental power. However, it also led to internal divisions, particularly over the issue of slavery in the new territories, which would eventually lead to a national split and civil war.

The purchase of Louisiana in 1803 was one of the most significant diplomatic coups in American history. For the modest sum of 15 million dollars, the United States obtained almost 827,000 square miles of land stretching west of the Mississippi River. This transaction doubled the size of the country overnight. These lands, formerly under the aegis of France and recently returned by Spain, were of major strategic importance to the young American republic. They offered fertile soil for agricultural expansion and vital access to the Mississippi River, a natural highway for trade. At the heart of this agreement was US President Thomas Jefferson. A visionary, Jefferson understood the crucial importance of this acquisition to the nation's future. However, the deal would not have been possible without Napoleon Bonaparte's European ambitions. Plagued by major conflicts, including the revolt in Haiti and tensions with other European powers, the French emperor was in urgent need of funding. It was against this backdrop that he agreed to sell these lands. Ultimately, this agreement opened the door to the westward march of the United States, laying the foundations for its continental expansion. More than just a land deal, the Louisiana Purchase symbolises the daring, vision and opportunity that shaped America's destiny.

In the early 19th century, the United States went through a period of great territorial expansion, shaping the geographical map we know today. The purchase of Louisiana in 1803 was one of these crucial moments. Although mainly made up of vast tracts of wilderness inhabited by various Amerindian tribes, this territory held immense potential for westward expansion, attracting many settlers and adventurers. Almost two decades later, in 1819, the territorial ambitions of the United States were once again manifested with the acquisition of Florida. The Adams-Onis Treaty, named after the principal American and Spanish negotiators, sealed this agreement. Spain, recognising the growing influence of the United States and faced with its own internal problems, ceded Florida. In return, the United States relinquished its claim to Texas and paid $5 million to settle Spain's debts to American citizens. This new acquisition not only increased the size of the United States, but also offered strategic ports, fertile farmland and key defence positions. However, these expansions were not without consequences. Native American tribes, who had lived on these lands for millennia, found themselves displaced and marginalised. American expansionism, with its dreams of prosperity and growth, came at the expense of the land rights and sovereignty of the indigenous peoples. These persistent tensions between settlers and indigenous peoples were the prelude to many conflicts and tragedies to come.

Bipartisanship

In the twilight of the 18th century, the young American republic was in a state of political ferment. The heated debates surrounding the brand new US Constitution gave rise to two distinct political ideologies, embodied by the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists, of whom Alexander Hamilton was an emblematic figure, advocated a strong central government. They believed in a liberal interpretation of the Constitution, which would allow greater flexibility in formulating policy and managing the affairs of state. Favouring an industrial economy and centralised government, the Federalists also tended to be closer to the interests of merchants, bankers and other urban elites. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, led by figures such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, were deeply sceptical of too much central power. They advocated a strict interpretation of the Constitution, arguing that the government should only have the powers expressly granted by the text. Valuing an agrarian society and states' rights, they feared that a strong central government would become tyrannical and threaten individual liberties. Although the Federalists played a crucial role in the early years of the Republic, their influence began to decline in the early 19th century, not least because of their unpopular opposition to the War of 1812. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans gained in popularity and influence. What is fascinating is how these early cleavages shaped the political evolution of the United States. The Democratic-Republican party fragmented over time, giving rise to the Democratic and Republican parties we know today, continuing a legacy of debate and divergence of ideas dating back to the very founding of the nation.

At the heart of the birth of the United States, two distinct political visions emerged, embodied by the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists, led by figures such as George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, advocated a Republic in which federal power played a predominant role. Wary of the excesses of direct democracy, they were convinced that the stability and prosperity of the nation required a strong central government. Their vision was partly shaped by their desire to see the United States prosper economically and commercially, often in close collaboration with Britain, the former colonial metropolis. Their main base of support came from urban, commercial and industrial circles in the North East, as well as wealthy landowners. At the other end of the spectrum, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, were ardent defenders of states' rights and distrustful of an omnipotent central government. They aspired to an agrarian republic and were convinced that the true essence of freedom lay in the land and the independence it offered. Despite their admiration for some of the ideologies of the French Revolution, they did not take a progressive view on issues such as racial equality. Their base was predominantly rural, with particular support from farmers, planters and pioneers, especially in the Southern and Western states. These early ideological clashes laid the foundations of the American political landscape. Although the Federalists eventually faded as the dominant political force, their legacy and ideals persisted. As for the Democratic-Republicans, they were the forerunners of today's Democratic and Republican parties, bearing witness to the evolution and transformation of political ideas over the centuries.

The birth of the United States took place in a tumultuous global context, marked by revolutionary upheavals in Europe, particularly in France. This period inevitably influenced the internal political dynamics of the United States, leading to intense polarisation between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, and this was particularly evident in the presidential election of 1800. The animosity between these two political parties was palpable. On the one hand, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, perceived the Federalists as haughty elites intent on emulating the British monarchy and undermining the young American democracy. They were convinced that the Federalists, by their closeness to Britain, were betraying American revolutionary principles. Their rhetoric often portrayed the Federalists as aristocratic figures, far removed from the concerns of the people. The Federalists, for their part, saw the Democratic-Republicans as a threat to the stability of the young nation. The French Revolution, with its guillotines and purges, haunted the Federalist imagination. John Adams and his supporters saw Jefferson and his party as emissaries of that radical revolution, ready to import its excesses and violence to America. For them, the Democratic-Republicans represented anarchy, a destructive force that, if left unchecked, could engulf the young republic in chaos. This climate of mutual suspicion and accusation made the presidential election of 1800 particularly acrimonious. Nevertheless, the election was also notable for the peaceful passage of power from one party to the other, a democratic transition that consolidated the republican character of the United States.

The presidential election of 1800, often referred to as the "Revolution of 1800", is a milestone in American political history. In many fledgling democracies, the transfer of power can be tumultuous, sometimes violent, when rival parties are at odds. However, this was not the case for the United States in 1800, even though the election was intense and passionate. The incumbent president, John Adams, a Federalist, was pitted against Thomas Jefferson, the Democratic-Republican candidate. Although these two iconic figures had radically different visions for the future of the country, the transition of power took place without bloodshed or violence. Indeed, once the Electoral College vote had been counted and Jefferson declared the winner after a vote in the House of Representatives to resolve a tie, Adams accepted his defeat and left the capital in peace. This moment not only demonstrated the resilience and strength of the young American democracy, but also set a precedent for the peaceful transfer of power that is now a pillar of the American democratic tradition. The election of 1800 also consolidated the country's two-party system, with two dominant parties shaping national politics, a model that endures to this day. The United States' ability to navigate peacefully through this transition sent a strong message to other nations and to its own citizens about the robustness of its democratic institutions and its commitment to republican principles.

Religion

A resurgence of religious fervour and an increase in religious activity

The "Great Awakening" in the United States actually refers to two distinct religious movements: the First Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s and the Second Great Awakening which began in the early 1800s. These movements had a profound impact on the religious, social and cultural landscape of America. The First Great Awakening began in the American colonies, influenced by preachers such as Jonathan Edwards, whose sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" is one of the most famous of the period. George Whitefield, an English evangelist, also played a central role in this movement, attracting thousands of people on his open-air preaching tours throughout the colonies. These preachers emphasised the personal experience of conversion and regeneration. The religious fervour of this period also led to the creation of new denominations and created some tension between these new converts and the established churches. The Second Great Awakening, which began in the early 19th century, was much more democratic in character. It was less tied to the established churches and emphasised personal experience, religious education and moral activism. Charles Finney, a lawyer turned evangelist, was one of the leading figures of this period. Known for his innovative methods at his "revival meetings", he preached the idea that individuals could choose their own salvation. This second revival also coincided with other social movements such as abolitionism, the temperance movement and women's rights. These two periods of revival helped to shape the religious landscape of the United States, creating religious pluralism and emphasising the importance of personal religious experience. The ideas and values that emerged from these movements also influenced other aspects of American culture and society, from music and literature to politics and social movements.

The Louisiana Purchase opened up huge tracts of land to American colonisation, and with this territorial expansion came a mosaic of beliefs and traditions. The borders of this vast territory were places of encounters, exchanges and sometimes tensions between various groups: settlers of diverse European origins, Amerindians with distinct cultures, and African-Americans, often brought by force as slaves. The Great Awakening, with its emotional message of renewed personal faith, resonated particularly strongly with these new settlers in the West. Many of these individuals, far removed from the established ecclesiastical structures of the East, were searching for a spirituality that responded to the unique challenges of life in these new territories. Revival preachers, with their passionate and direct style, often found a receptive audience in these frontier regions. In addition to traditional preaching, numerous camp meetings - open-air religious gatherings lasting several days - were held throughout the Louisiana Purchase region. These events, which often brought together thousands of people, helped to spread the ideals of the Great Awakening. They also provided a platform for the formation and strengthening of new denominations, particularly the Methodists and Baptists, which were to become dominant in many parts of the West. The fusion of the Great Awakening with the pioneering spirit of the region had lasting consequences. It encouraged the formation of many local churches and contributed to a sense of community and shared identity among the settlers. The revival also interacted with other social movements of the time, influencing causes such as temperance, education and, in some cases, the abolition of slavery. So while the Great Awakening transformed the religious landscape across the United States, its impact in the Louisiana Purchase region is a remarkable example of how faith and the frontier shaped each other during this formative period in American history.

The religious and spiritual effervescence of the Great Awakening had a profound and lasting effect on American society. Breaking with the liturgical and hierarchical traditions of some established churches, the movement encouraged individuals to establish a personal relationship with God, without the intermediary of institutions. This emphasis on personal experience and individual salvation led to an explosion of religious diversity. Denominations such as the Baptists and Methodists, with their decentralised structure and emphasis on individual religious experience, flourished in particular. They offered an alternative to more formal religious traditions, particularly in frontier areas where established institutions were less present. As well as religious diversification, this revival had a significant impact on the social and political fabric of the United States. The movement's belief in the spiritual equality of individuals naturally challenged structures of earthly inequality. If every person is equal before God, then how can institutions like slavery be justified? From this question arose a fascinating intersection between the religious piety of the Great Awakening and the nascent abolitionist movement. Many abolitionists were motivated by religious convictions, seeing slavery as an abomination contrary to the teachings of Christianity. Figures such as Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose famous novel "Uncle Tom's Cabin" galvanised public opinion against slavery, were deeply influenced by the ideals of the Great Awakening. Beyond abolitionism, the Great Awakening also fuelled other reform movements, such as those for women's rights, temperance and education. The renewed belief in the capacity of the individual to improve himself and to draw closer to God encouraged many believers to engage in actions aimed at improving society as a whole. So the Great Awakening was not just a religious revival. It was also a social and political catalyst, shaping the nation in ways that its instigators might never have imagined.

The Great Awakening, with its renewed evangelical fervour, introduced a dimension of passionate proselytism into the American religious landscape. This missionary energy was deployed not only to convert other Americans but also to extend Protestant Christianity to other regions, particularly in frontier territories. The militant approach adopted by some Great Awakening evangelists often put them at odds with other religious groups. Catholics, for example, were already often suspicious or hostile towards the Protestant majority. But with the Great Awakening, this mistrust turned into open confrontation, as many evangelicals saw Catholicism as a deviant form of Christianity. These tensions were exacerbated by the arrival of Catholic immigrants, particularly from Ireland and Germany, in the 19th century. In some regions, this led to acts of open violence, such as anti-Catholic riots. In addition, the evangelical dynamic of the Great Awakening often clashed with the religious practices of indigenous peoples. Protestant missionaries, burning with evangelical fervour, sought to convert the Amerindians to Christianity, which often led to the suppression of indigenous religious beliefs and practices. These efforts were often underpinned by the belief that native religious practices were "pagan" and had to be eradicated for the "salvation" of the Amerindians. Ultimately, while the Great Awakening brought new vitality to many Protestant congregations and helped shape the American religious and cultural landscape, it also generated division and conflict. These tensions reflect the challenges the United States faced as a growing nation seeking to reconcile religious and cultural diversity with passionate religious reform movements.

Camp meetings were one of the most distinctive phenomena of the Great Awakening, particularly in the border region of the United States. They offered an intense collective religious experience in an atmosphere that was often emotionally charged. The Cane Ridge camp meeting, held in 1801 and attended by up to 20,000 people, is perhaps the most famous and striking example of these events. For several days, thousands of people gathered in this rural area of Kentucky, listening to preachers, praying, singing, and participating in religious rituals. Reports speak of incredible emotional intensity, with people falling into trances, speaking in tongues, and showing other ecstatic manifestations of their faith. These meetings were partly the result of the scarcity of churches and regular preachers in the border region. People often came from far and wide to attend, bringing food and tents with them and camping out for the duration of the meeting. These camp meetings also played a crucial role in facilitating the spread of the evangelical movement. New denominations, such as the Christian Churches (sometimes called Disciples of Christ) and the Churches of Christ, came into being or were strengthened by these gatherings. The meetings also helped to establish Methodism and Baptistry as major forces in the region, partly because of their more decentralised structure and their tailored approach to the needs of the frontier population. In addition, these meetings offered a rare moment of egalitarianism in early nineteenth-century American society. People from different socio-economic backgrounds rubbed shoulders, sharing a common religious experience, although racial divisions often remained in place. The development of new religious sects during this period can be understood as a response to the rapid expansion of the American frontier. As new settlers moved west, they often found themselves in areas where there were few established churches or religious institutions. The Great Awakening gave these settlers the opportunity to create new religious communities that reflected their own beliefs and values.

The westward expansion of the United States represented a period of profound change and uncertainty for the migrants. In this changing context, religion emerged as an anchor, offering both emotional support and practical tools for navigating the new landscape. For many migrants facing the harsh reality of the border, religion has played a central role in the formation of new communities. In the absence of the traditional networks of family and friends left behind in their region of origin, faith became the glue that held people together. The new sects or denominations offered not only a place to worship, but also a network of mutual support, essential in these sometimes hostile territories. While everything seemed new and foreign, religion also offered a dose of familiarity. Rituals, songs and religious traditions reminded migrants of their past and gave them a sense of continuity in an ever-changing world. The American border was a meeting place for different cultures, particularly between migrants and indigenous peoples. In this mix, religion helped to define and maintain distinct identities. It also served as a moral compass, guiding interactions between these diverse groups. Beyond its role in shaping individual and collective identities, religion has also been a lever for social change. The Great Awakening, for example, not only renewed religious fervour, but also paved the way for social movements such as abolitionism. Religious teachings, by promoting values such as equality and fraternity, have often been used to argue in favour of social causes. In short, religion in the context of westward expansion was not just a matter of faith or spiritual salvation. It was deeply rooted in the daily lives of migrants, influencing the way they interacted with their new environment, built their communities and envisaged their place in this new frontier.

The Great Awakening, a major religious phenomenon, left an indelible mark on American religious culture. Its impact is not limited to a simple resurgence of religious fervour, but manifests itself in more structural and cultural ways. One of the most notable consequences of the Great Awakening was the emergence of new religious denominations. Baptists and Methodists, in particular, saw their influence grow exponentially during this period. These movements, with their innovative approaches to worship and doctrine, not only diversified the religious landscape, but also offered the faithful new ways of expressing and living their faith. Beyond the emergence of new churches, the Great Awakening also promoted a more individualised form of religiosity. Unlike earlier religious traditions, where doctrine and rites were often prescribed by an ecclesiastical authority, this new wave of awakening encouraged a personal and direct relationship with the divine. The faithful were encouraged to read and interpret the Scriptures for themselves, and conversion was often presented as an emotional and personal experience, rather than a collective rite. This shift towards individualism had a major impact on American religious culture. It reinforced the idea of religious freedom, fundamental to American philosophy, and opened the way to a plurality of beliefs and practices within denominations. In conclusion, the Great Awakening did not simply reinvigorate faith among Americans; it redefined the way in which they live and understand it. Its echoes are still felt today in the diversity and individualism that characterise religious culture in the United States.

The role of the Great Awakening in shaping the role of women in politics

The Great Awakening, which took place in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was a major turning point in American religious and social life. As well as transforming the religious landscape, this movement indirectly laid the foundations for a change in the role of women in society, particularly in politics. Before the Great Awakening, the place of women in religious institutions was mainly restricted to passive or secondary roles. However, the movement encouraged the active participation of the laity, opening up new opportunities for women. Many women became preachers, teachers and leaders in their communities. This new religious responsibility has given them a more significant voice and presence in the public arena. Driven by this new visibility and self-confidence, many of these committed women have extended their activities beyond the religious sphere. They became leading figures in various social reform movements, such as temperance, education and, above all, the abolition of slavery. This commitment laid the foundations for broader female participation in public and political affairs. The experience of leadership and mobilisation acquired during the Great Awakening paved the way for subsequent movements. The skills and networks developed in the religious context were transferred to political causes, notably the women's rights movement. The Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, often considered the starting point of the women's rights movement in the United States, saw the active participation of many women who had been influenced or active during the Great Awakening. The Great Awakening therefore not only redefined the American religious landscape, but also indirectly laid the foundations for a major change in the role of women in society. By opening new doors within religious institutions, the movement enabled women to embrace leadership roles, champion social causes and ultimately claim their own rights as full citizens.

During the Great Awakening, the religious and social dynamics of the United States underwent major changes, particularly in terms of women's participation and leadership. While religion played an essential role in the lives of the American colonists, the Great Awakening overturned many established traditions, offering women new opportunities for active participation. Camp meetings and religious revivals were spaces where the usual social barriers seemed less rigid. Women, historically restricted to supportive roles or passive observers in many religious fields, were suddenly seen as essential partners in spiritual experience. At these gatherings, raw emotion and personal experience prevailed over convention, allowing women to take centre stage. As well as being encouraged to share their faith through song and prayer, many women began to speak openly about their spiritual experiences, breaking with a tradition that restricted public speaking to men. This break was crucial, as it enabled women to hone their public speaking and leadership skills. By sharing their testimonies, they not only strengthened their own faith; they also inspired those who heard them. The confidence and eloquence that many women acquired during the Great Awakening transcended the strictly religious. These newly acquired skills laid the foundations for their involvement in other public spheres, paving the way for their future participation in social and political reform movements. Ultimately, the Great Awakening not only reinvigorated American religious fervour; it also served as a catalyst for pushing back the limits traditionally imposed on women. By placing them on an equal footing with men in religious experiences, the movement indirectly contributed to the evolution of women's position in American society.

The Great Awakening, beyond its predominant influence on spiritual revitalisation, was an essential vector of social change, particularly in strengthening the role of women within religious communities and, by extension, in society in general. The birth of denominations such as the Methodists and Baptists was a reflection of the growing diversity of beliefs and theological interpretations that emerged during this period. These denominations, unlike some of the more established religious traditions, were often more open to the idea of innovation and change. A particularly progressive aspect of these new denominations was their recognition of women not only as active worshippers, but also as potential leaders. Women were allowed, even encouraged, to preach, teach and make decisions that would have been reserved exclusively for men in other contexts. This opening was revolutionary. It not only validated the spiritual equality of women, but also provided a platform from which they could demonstrate their competence, leadership and passion. By building a reputation and gaining respect within their faith communities, many women gained the confidence and recognition to venture beyond the boundaries of the church. Armed with their new status and leadership skills, they began to get involved in areas traditionally dominated by men, such as politics, civil rights and various social movements. The Great Awakening, therefore, not only brought about a religious revival, it also planted the seeds of wider social transformation. By giving women a platform to express themselves and recognising their potential as leaders, the movement set a precedent and an impetus for deeper and lasting societal change.

By shaking the foundations of traditional religious norms, the Great Awakening also challenged the social conventions of the time. In this context of religious ferment, women found an unprecedented opportunity to play a more active role, not only in religious affairs, but also in the public sphere. It was a time when women's voices were largely marginalised in most areas of society. The Great Awakening enabled many women to rise above this marginalisation, giving them a platform where they could express themselves and be heard. These experiences within religious congregations armed many women with the courage and determination to demand greater equality and recognition in other areas. Traditional roles that confined women to the domestic sphere have been challenged. With their increased involvement in religious affairs, many began to realise that their abilities went far beyond the roles historically assigned to them. This, in turn, challenged the legitimacy of these traditional roles and opened the door to a wider redefinition of gender roles. This gradual change in the perception of women's capabilities, stimulated in part by the Great Awakening, laid the foundations for more structured and organised movements. The women's rights movement, which gained ground in the 19th century, benefited from the advances made during this period. The leadership skills, confidence and experience gained armed these pioneers to demand greater equality in society. In this way, the Great Awakening, while primarily a religious movement, had a profound and lasting impact on the social structure of America, particularly with regard to the position of women. It helped lay the foundations for challenging traditional roles and norms, paving the way for broader and more ambitious reform movements.

The Great Awakening, while broadening the horizons for women in the religious sphere and offering them a ground for developing their leadership skills, did not necessarily translate into a total acceptance of female emancipation in all aspects of society. While this religious movement opened certain doors, it did not eliminate the structural barriers that were deeply rooted in American society at the time. Although the Great Awakening enabled many women to speak out and lead, it did not protect them from the dominant prejudices and stereotypes. In the patriarchal society of the time, the role of women was still widely perceived as being confined to the home. Any woman who dared to venture beyond these conventional boundaries was met with opposition and criticism, both from society in general and, sometimes, from within their own religious community. Women's participation in religious affairs did not translate into equal recognition in the civic sphere. Women did not have the right to vote and were largely excluded from decision-making institutions. Although they could influence politics through indirect means, such as education or moralist pressure groups, they had no real formal political power. The advances made during the Great Awakening laid the foundations for later demands for equal rights for women. However, the road to equality was still long and full of pitfalls. It took decades of struggle, sacrifice and perseverance for women to obtain fundamental political rights, such as the right to vote, which was only granted with the 19th amendment in 1920. In conclusion, although the Great Awakening represented a significant step forward in giving women greater visibility and a platform to assert their role in society, it failed to completely dismantle deeply rooted patriarchal structures. The advances made in the religious sphere were only the beginning of a long struggle for full equal rights.

Impact of the Great Awakening on the African-American community

At the turn of the 19th century, the Great Awakening shook up the religious and socio-political landscape of the United States. At the heart of this transformation were two groups that were particularly affected: women and blacks. Women, traditionally relegated to subordinate roles in a patriarchal society, found in the Great Awakening a platform for expression. Taking an active part in camp meetings offered them the opportunity not only to affirm their beliefs, but also to develop oratory and leadership skills. Religious denominations such as the Baptists and Methodists, by embracing female participation, opened up new avenues for female leadership in both religious and secular spheres. This religious effervescence became the prelude to the women's rights movement that was to gain strength over the course of the century. At the same time, the situation of black people in the country, whether free or enslaved, was influenced by this religious revival. The meetings of the Great Awakening, which advocated universal salvation, offered one of the rare opportunities for communion between blacks and whites. These teachings, which held out the promise of spiritual equality, laid the foundations for the questioning of slavery, fuelling the nascent abolitionist discourse. However, it should be stressed that these advances were far from uniform. While the Great Awakening opened doors for some, it simultaneously reinforced patriarchy and racial hierarchies for others. The Great Awakening, while a moment of spiritual and social awakening, reflected the complexities and contradictions of its time. For women and blacks, it represented both an opportunity and a challenge, illustrating the continuing tensions in the American quest for equality and justice.

Amid the tumult of the Great Awakening, black Americans found a platform to redefine and reaffirm their religious and cultural identity. Torn from their African homeland and immersed in the brutality of slavery, these individuals were deprived not only of their freedom, but also of their ancestral religious practices. Often they were forced to adopt Christianity, a religion which, in a cruel irony, was often used to justify their own enslavement. However, the Great Awakening, with its message of spiritual equality and universal salvation, offered Black people an unprecedented opportunity to reconnect with their spirituality. Drawing on both Christian teachings and their own African traditions, they forged a new mode of worship that reflected their unique experience as blacks in America. This period saw the emergence of distinctly black religious congregations, where African and Christian beliefs merged to create a resolutely African-American spiritual expression. This movement was not just an affirmation of faith; it was also an act of resistance. In a context where their humanity was constantly denied, these religious assemblies were bold declarations of their humanity and their divine right to dignity and respect. By embracing Christianity on their own terms and fusing it with their ancestral traditions, black people not only shaped their own spiritual identity, but also laid the cultural and communal foundations that would sustain them in future struggles for freedom and equality.

The founding of the African Evangelical Apostolic Church in Philadelphia in 1801 was part of a period of social and religious ferment. This establishment reflected a thirst for spiritual equality and a desire for identity affirmation among the black American community. In those days, black people, whether slaves or free, often faced blatant discrimination even in places that were supposed to offer refuge and equality, such as churches. These buildings, dominated by whites, regularly refused black worshippers access to certain areas or relegated them to separate seats away from whites. In this context, the creation of the African Evangelical Apostolic Church was much more than a simple act of faith; it was a rebellion against institutionalised racism and a powerful affirmation of the dignity and worth of black people as believers and children of God. This church, one of the very first black churches in the country, was not only a place of worship, but also a sanctuary for Philadelphia's African-American community. It allowed its members to practice their faith without the discrimination and humiliation they often faced in white churches. Moreover, as an institution, it played a fundamental role in strengthening community ties and affirming black identity at a time when this identity was constantly being challenged. It served as a springboard for many other African-American churches and institutions, laying the foundations for a black religious tradition in the United States that persists and flourishes to this day.

During the Great Awakening, a wave of spiritual awakening swept across the United States, affecting various segments of the population, including enslaved blacks. For the latter, the movement offered an unprecedented opportunity to access the religious word and make their own interpretations of it. The evangelical message of salvation, hope and redemption resonated particularly strongly among them, offering a glimmer of hope in the darkness of oppression. The slaves' interest in the Christian teachings of the Great Awakening was partly due to its direct relevance to their lives. The themes of freedom from sin, the promise of an afterlife and salvation resonated with their aspirations for freedom and a better life. For many, Christianity became a means of transcending their brutal reality and finding meaning and hope in a world that often seemed hostile. In addition, this period saw the emergence of religious practices that fused elements of Christianity with African traditions, creating a unique form of African-American spirituality. Songs, dances and prayers incorporated elements of their African roots, helping them to maintain a connection with their heritage while adapting to their new reality. Ultimately, the Great Awakening not only brought slaves spiritually closer to God, but also contributed to the birth of a distinct African-American religious identity, combining elements of the Christian faith with the traditions and experiences of the African diaspora.

At the heart of the Great Awakening, the religious effervescence that swept the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, a singular paradox was revealed. On the one hand, this period provided a platform for black people to affirm and explore their own spirituality and religious identity. On the other hand, pervasive discrimination, segregation and racism often restricted and hindered their full participation in this religious renaissance. Despite the spiritual effervescence of the Great Awakening, many black communities were relegated to the periphery, both literally and figuratively. In many churches, segregation was the norm, with black people often confined to the balcony or other segregated areas. While messages of equality before God and salvation were preached, the practice of this equality was sadly absent. In addition, blacks who attempted to organise their own religious celebrations or practices often faced repression from those who saw such gatherings as a potential threat to the established order. Yet in the face of these challenges, the resilience of the black community shone through. Their efforts to forge a unique spiritual identity, blending elements of the Christian faith with African traditions and rituals, laid the foundations for a distinctly black religious movement in the United States. In addition, the discrimination they experienced strengthened the determination of some black leaders to create their own religious institutions where their community could worship freely, free from prejudice and segregation. It was in this context that churches such as the African Evangelical Apostolic Church in Philadelphia came into being. They served not only as places of worship, but also as community centres, providing a space where black identity, culture and spirituality could flourish. Later, these religious foundations also paved the way for more advanced theological movements, such as Black Theology, which sought to reinterpret Christian teachings through the lens of the African-American experience.

The "Second Middle Passage", like the original Middle Passage that brought millions of Africans to America as slaves, is a dark period in American history. This internal movement of slaves was driven by economic, social and political factors. The rise of "king cotton" in the Deep South radically altered the economic dynamics of the region, and consequently the fate of many slaves. The end of the international slave trade in 1808, following constitutional prohibition, increased the demand for slaves within the country. The plantations of the Upper South, which had begun to feel the decline in the profitability of their traditional crops such as tobacco, found in the sale of slaves a lucrative source of income. At the same time, the Deep South was experiencing a phenomenal expansion in cotton growing, largely due to the invention of 'cotton gin' by Eli Whitney in 1793, which made cotton processing much more efficient. This economic climate gave rise to a massive internal slave trade, with vast caravans of chained men, women and children travelling south-west. These slaves were often separated from their families, a rupture that inflicted indescribable emotional and psychological pain. Western territories such as Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana quickly became the main strongholds of cotton cultivation and slavery. The dynamics of this forced migration strengthened the control and power of slave owners, further solidifying the system of slavery in the culture and economy of the South. However, the Second Middle Passage, with its traumas and separations, also led to the creation of new forms of resistance, culture and spirituality among the slaves, who struggled to find ways to survive and resist in these extremely difficult circumstances.