« 法律的实施 » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 165 : | Ligne 165 : | ||

在阿拉曼尼王国,根据 720 年左右的阿拉曼尼法(lex Alamannorum)的规定,法官必须由公爵任命,但也要经过人民的批准。这一规定强调了社会认可和合法性在法官遴选中的重要性。770 年左右在查理曼统治时期开始的加洛林王朝司法改革对这一制度进行了重大改革。判决权被赋予了作为常任法官的市议员。这一改革削弱了国王在批准判决方面的作用,从而进一步集中了司法权。此时确立的低级司法(causae minores)和高级司法或刑事司法(causae majores)之间的区别尤其值得注意。它为现代民事诉讼和刑事诉讼的区分奠定了基础。初级法院处理通常属于民事性质的轻微案件,而高级法院则处理刑事案件,这些案件被认为更为严重,涉及更严厉的处罚。司法管理方面的这些历史发展反映了从基于社区参与的司法系统向更加集中和有组织的系统的过渡,为当代司法结构铺平了道路。它们还显示了法律的基本原则,如合法性、代表性和不同类型争端之间的区别,是如何随着时间的推移而演变和形成的。 | 在阿拉曼尼王国,根据 720 年左右的阿拉曼尼法(lex Alamannorum)的规定,法官必须由公爵任命,但也要经过人民的批准。这一规定强调了社会认可和合法性在法官遴选中的重要性。770 年左右在查理曼统治时期开始的加洛林王朝司法改革对这一制度进行了重大改革。判决权被赋予了作为常任法官的市议员。这一改革削弱了国王在批准判决方面的作用,从而进一步集中了司法权。此时确立的低级司法(causae minores)和高级司法或刑事司法(causae majores)之间的区别尤其值得注意。它为现代民事诉讼和刑事诉讼的区分奠定了基础。初级法院处理通常属于民事性质的轻微案件,而高级法院则处理刑事案件,这些案件被认为更为严重,涉及更严厉的处罚。司法管理方面的这些历史发展反映了从基于社区参与的司法系统向更加集中和有组织的系统的过渡,为当代司法结构铺平了道路。它们还显示了法律的基本原则,如合法性、代表性和不同类型争端之间的区别,是如何随着时间的推移而演变和形成的。 | ||

=== | === 审问 === | ||

审问式程序起源于教会司法和教会法,之后传入世俗法律体系,特别是在 13 世纪以后。在审问式程序中,法官或治安法官在寻求真相的过程中扮演着积极的角色。在对抗式诉讼中,重点是辩方和控方之间的对抗,而在审问式诉讼中,法官负责调查、询问证人、审查证据并确定案件事实。其主要目的是发现客观真相,而不是完全依赖对方提出的论点和证据。 | |||

从历史上看,这种方法深受教会法庭做法的影响,教会法庭试图通过教会当局的彻底调查过程来确立精神和道德上的真理。在教会法中,寻求真相被视为一种道德和精神责任,这也影响了调查的方式。13 世纪,欧洲的世俗司法系统开始采用审问程序。与通常依赖口头证据和双方直接对质的传统司法方法相比,人们希望司法更加系统化和集中化,这刺激了这种采用。在遵循审问式程序的现代制度中,例如在许多欧洲国家,法官在调查事实和进行审判方面仍发挥着核心作用。不过,重要的是要注意到,现代司法制度已经发展到纳入了旨在保护被告权利的程序保障措施,同时允许对事实进行彻底和客观的调查。 | |||

有人认为审问式程序将社会利益置于个人利益之上,符合专制政权的需要,这种看法源于审问式程序本身的性质。事实上,在审问式制度中,法官或治安法官在调查、收集证据和确定事实方面发挥着核心和积极的作用,这有时可被视为权力的集中,有可能更广泛地有利于国家或社会的利益。在专制政权中,这种司法制度可用于加强国家控制,强调维护公共秩序和安全,有时会损害个人权利。法官在进行调查和决策时被赋予很大的权力,这可能会导致失衡,从而损害被告获得公平审判和充分辩护的权利。然而,必须强调的是,现代形式的审问式程序在许多民主国家都有实施,这些国家的法律法规旨在保护个人权利。在这些情况下,都有相应的机制来确保被告的权利,如聘请律师的权利、接受公正审判的权利和发表意见的权利等得到尊重。现代司法制度的演变表明,只要有适当的程序和司法保障,审问式程序与尊重个人权利是可以并存的。因此,不仅要考虑审问式程序的结构,还要考虑其实施的法律和制度背景,这一点至关重要。 | |||

审问式程序的名称来源于 "inquisitio",这是一种最初的手续,它决定了调查的进行,进而决定了整个审判的进行。在这类程序中,治安法官从调查一开始就发挥着主导作用,调查通常是依职权启动的,即没有私人当事方提出的具体申诉。调查可以由治安法官本人发起,也可以由检察官或警官等公职人员发起。治安法官负责收集和审查证据、询问证人,并在总体上开展调查,以确定案件事实。这种方式与对抗式诉讼有很大不同,对抗式诉讼通常由双方(控方和辩方)进行调查,然后向法官或陪审团提交证据和论据。除进行调查外,在审问式诉讼中,地方法官还在审判期间指导诉讼程序。他或她会向证人提问、审查证据并引导讨论,以确保案件的所有相关方面都得到处理。治安法官的这种积极作用旨在确保对事实的全面了解,并帮助法庭在对证据进行全面分析的基础上做出判决。这种制度起源于教会法和教会司法,在教会法和教会司法中,寻求真相被视为道德和精神上的当务之急。在采用审问式程序的当代司法系统中,尽管治安法官的作用非常重要,但一般都会制定程序保障措施,以保护被告的权利并确保审判的公正性。 | |||

在审问式程序中,治安法官拥有相当大的调查权,其行使方式有别于其他法律制度中更为熟悉的对抗式程序。地方法官进行的调查通常具有秘密性、书面性和无对抗性的特点。 | |||

审问式调查的秘密性使治安法官能够在没有外部干预的情况下收集证据,这对于防止证据被隐藏或销毁至关重要,尤其是在复杂或敏感的案件中。例如,在大规模腐败案件中,初步调查的保密性可以防止嫌疑人篡改证据或影响证人。在这一系统中,书面文件占主导地位,这意味着陈述、调查报告和证据主要以书面形式记录和存储。这种方法确保了信息记录的准确性和持久性,但可能会限制口头交流中的动态互动,例如在听证或审讯中观察到的互动。此外,调查阶段缺乏对抗性也会让人质疑审判的公正性。在审问式程序中,对方当事人,尤其是被告方,并不总是有机会对治安法官在这一阶段收集的证据提出质疑或直接做出回应。这种情况可能会导致失衡,尤其是当辩方无法获得收集到的所有信息或无法对其进行有效质疑时。因此,必须建立控制机制和程序保障,以平衡纠问式程序中以地方法官为中心的做法。这些机制必须确保尊重被告的权利,包括公平审判权和充分辩护权,同时允许对事实进行彻底客观的调查。目的是确保司法系统在调查的有效性和对基本权利的尊重之间实现平衡。 | |||

审问式程序的特点是主要由法官进行调查,它有很大的优缺点,影响其有效性和公正性。这一制度的主要优点之一是降低了有罪方逃脱法律制裁的风险。由于法官在开展调查时采取了积极主动和深入细致的方法,因此更有可能发现相关证据,并查明犯罪责任人。这种方法在复杂或敏感的案件中尤为有效,因为在这些案件中,需要进行彻底的调查才能发现真相。然而,审问式程序的缺点也不容忽视。最令人担忧的风险之一是可能给无辜者定罪。在调查阶段,如果没有强有力的辩护和对抗性辩论的机会,被告可能会发现自己处于不利地位,无法有效质疑对其不利的证据。这可能导致司法不公,无辜者因片面的调查而被定罪。在技术层面上,审问式程序常常因其冗长而受到批评。调查的彻底性和书面性可能会导致刑事案件的解决严重拖延,延长被告和受害者等待案件解决的时间。此外,对书面文件的重视和审判过程中缺乏直接互动会导致司法程序非人性化。这种方法可能会忽视案件中的人性和情感方面,而将重点严格放在书面证据和正式程序上。为了减少这些弊端,许多采用审问式程序的司法系统进行了改革,以加强被告方的权利,加快诉讼程序,并在司法程序中加入更多互动和人性化的元素。这些改革旨在平衡有效寻求真相与尊重被告和受害者基本权利之间的关系。 | |||

在以审问式调查为主导的司法系统中,审判结果往往在很大程度上取决于调查结果,这是事实。在治安法官或法官在进行调查和管理证据方面发挥核心作用的情况下,审判听证有时会被视为一种形式,而不是被告质疑对其不利的证据和论点的真正机会。在这种情况下,被告可能会发现自己处于不利地位,因为调查阶段主要由治安法官控制,占据了司法程序的主要部分。如果调查期间积累的证据和结论具有很强的指控性,被告可能会发现在审判时很难扭转这些看法,特别是如果程序不能保证被告有充分的机会进行全面完整的辩护。这种态势引发了对审判公正性的担忧,尤其是在尊重无罪推定权和公平审判权方面。如果庭审流于形式,对抗性司法原则和控辩平衡原则就会受到损害。为了减少这些弊端,许多司法系统都在努力改革审问式程序。这些改革旨在增强辩护方的作用和权利,确保调查过程更加透明,并保证审判听证是一个实质性阶段,被告在此阶段有真正的机会对证据提出质疑并陈述自己对事实的看法。这些改革的目的是根据公平审判的原则,确保调查的有效性与尊重被告权利之间的平衡。 | |||

欧洲刑事诉讼程序的历史经历了重大演变,特别是受到启蒙运动的理想以及随之而来的社会和政治变革的影响。在第二个千年期间,特别是自十九世纪以来,欧洲的法律制度经历了一个转变的过程,目的是将纠问式和对抗式程序中最有效和最公平的方面融入其中。 | |||

在启蒙运动时期,人们对传统提出质疑,提倡个人权利和理性,对纠问式程序中最僵化、最具压迫性的方面的批评也随之加强。当时的哲学家和改革家,如伏尔泰和贝卡利亚,都强调了这一制度的缺陷,尤其是其缺乏公正性以及经常任意对待被告。他们呼吁进行司法改革,以确保更好地平衡国家权力和个人权利。为了应对这些压力和政治发展,特别是席卷欧洲的革命,许多国家开始改革其司法制度。这些改革旨在采用对抗式诉讼程序的要素,如加强辩护方的作用、无罪推定和审判的对抗性,同时保留纠问式诉讼程序特有的结构化和详尽的调查方法。这些变革的结果是建立了混合司法体系。例如,在法国,司法改革产生了这样一种制度:虽然初步调查由治安法官或检察官进行(审问式特点),但被告的权利受到有力保护,审判本身在公正的法官或陪审团在场的情况下以对抗方式进行(对抗式特点)。这些混合制度力求在效率和公正之间取得平衡,既能进行彻底调查,又能确保被告的权利得到尊重。虽然欧洲各国的这些制度各不相同,但这种融合两种程序最佳做法的趋势已成为欧洲现代司法制度的主要特征。 | |||

现代司法制度中的刑事诉讼一般分为两个不同的阶段,这两个阶段融合了纠问式和对抗式两种方法的特点,从而满足了不同的司法目标和原则。初步阶段通常是审问式的。首先是警方调查,执法机构在调查中初步收集证据、询问证人并开展调查,以确定案件事实。这一阶段至关重要,因为它为法律案件奠定了基础。例如,在盗窃案件中,警方将收集物证、询问证人并收集监控录像。这一阶段之后是司法调查,在一些国家由预审法官进行。预审法官进一步开展调查,要求提交专家报告、询问证人并采取措施收集更多证据。这一阶段的特点是秘密、书面和非对抗性,旨在收集所有必要信息,以决定是否对案件进行审判。另一方面,决定性阶段具有对抗性。在这一阶段进行实际审判,然后做出判决。这一阶段是公开的、口头的和对抗性的,允许证据和论点的直接对抗。在审判期间,辩方和控方律师都有机会陈述案情、询问证人并质疑对方的证据。例如,在欺诈案件中,辩方可能会质疑控方提供的财务证据的有效性,或提供相互矛盾的证词。法官或陪审团在听取各方意见后,根据所提供的证据和论据做出判决,从而保障公平审判的权利。这种两阶段的结构反映了在调查的效率和严谨性与公正司法和保护被告权利的原则之间取得平衡的尝试。这表明,司法系统正朝着寻求将两种方法的优点结合起来的方向发展,既保证彻底调查,又尊重基本权利和民主司法程序。 | |||

刑事诉讼中出现的混合制度结合了纠问式和对抗式两种方法的优点,是启蒙运动前后开始形成的显著发展。这一时期,人们重新强调理性、人权和公平正义,对社会的许多方面进行了重大改革,包括司法制度。这种混合制度试图借鉴两种传统刑事诉讼方法的优点。一方面,审问式方法因其在收集和彻底审查证据方面的有效性而得到认可,法官或治安法官在调查中发挥着积极作用。另一方面,对抗式方法因其对抗性和透明性而备受推崇,可确保被告有公平公正的机会针对指控为自己辩护。因此,在混合制度的决定性阶段,我们可以发现两种方法的要素。例如,虽然法官可以在评估证据方面发挥积极作用(审问式特征),但被告和辩护方也有机会质疑这些证据并提出自己的论点(对抗式特征)。这一阶段通常是公开的,在听证会上公开出示和审查证据,允许辩方和控方直接对质和辩论。采用这种混合制度是为了在调查的效率和严谨性与尊重被告权利和公平审判原则之间取得平衡。这一发展反映了法律和司法思想的重大演变,它受到启蒙运动理想的影响,旨在促进更公平、更均衡的司法。 | |||

== | == 刑事诉讼的原则 == | ||

合法性原则在刑法中发挥着至关重要的核心作用,既规范实体规则,也规范程序。这一原则是许多法律制度的基本原则,它确保刑事行动和制裁以法律为依据。 | |||

在实体规则方面,合法性原则规定,任何人不得因其实施时法律未界定为犯罪的行为而被认定有罪或受到惩罚。这一原则对于确保法律适用的公正性和可预见性至关重要。例如,如果某人实施的行为在当时有效的法律下不被视为犯罪,那么即使后来法律发生变化,也不能因该行为对其提起刑事诉讼。这体现了 "法无明文规定不为罪,法无明文规定不处罚 "的格言,即没有先行存在的法律,就不会有犯罪或处罚。合法性原则也适用于刑事诉讼。这意味着司法程序的所有阶段,从调查到定罪,都必须按照法律规定的程序进行。这确保被告的权利在整个司法程序中得到尊重。例如,获得公正审判的权利、辩护的权利和在合理时间内接受审判的权利,这些都是刑事诉讼程序中必须由法律明确规定和保障的方面。 | |||

尊重实体和程序规则的合法性原则是防止司法专断的保障,也是保护人权的支柱。它确保个人不会受到追溯性的刑事制裁或没有适当法律依据的司法程序。这一原则加强了公众对刑事司法系统的信心,确保个人依法受到公平对待,从而促进了司法程序的完整性和合法性。 | |||

=== | === 合法性原则 === | ||

就行政行为而言,合法性原则是许多法律制度中法治的重要基础。这一原则要求公共行政只能在法律规定的框架内行事。它有两个基本方面:法律至上和行政行为必须有法律依据。 | |||

法律至上或至高无上原则规定,行政部门必须遵守所有管辖它的法律规定。这意味着行政部门的所有活动和决定都受现行法律的约束,必须按照这些法律行事。这一原则确保政府的行动不是任意的,而是受法律框架的指导和限制。在实践中,这意味着行政决定,如发放许可证或实施制裁,必须以明确制定的法律为基础,不得减损立法规范。此外,法律依据原则要求行政部门的任何行动都必须有法律依据。换句话说,只有在法律明确授权的情况下,当局才能采取行动。这一原则限制了行政行为的范围,确保行政部门采取的每一项措施都有坚实的法律依据。例如,如果政府机构希望实施新的法规,就必须确保这些法规得到现行法律的授权,或者是根据新的法律制定的。 | |||

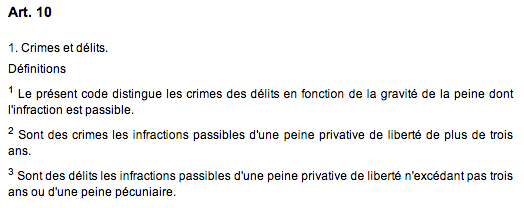

合法性原则的这两个方面--法律至上和法律依据要求--共同确保行政部门以透明、可预测和公平的方式行事。它们有助于保护公民免受滥用权力之害,并增强人们对行政和政府机构的信心。简而言之,合法性原则对于确保行政部门在法律赋予的权力范围内运作,从而维护民主原则和法治至关重要。[[Fichier:Code pénal suisse - article 1.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19370083/ Code pénal suisse] — [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19370083/index.html#a1 article 1]]] | |||

瑞士刑法典》第 1 条规定了一项刑法基本原则,即通常所说的刑事合法性原则: "没有法律就没有惩罚"。该原则规定,只能对法律明确规定和应受处罚的行为实施处罚或措施。这一规定确保个人只能因实施时被明确界定为犯罪的行为而受到起诉和惩罚。这在一定程度上确保了刑法的可预测性,并保护公民免受司法专断之害。 | |||

法无明文规定不处罚 "原则是法律确定性和尊重人权的基本要素。它可以防止刑法的追溯适用,确保刑事制裁以清晰、准确和公开的法律为基础。例如,如果颁布了新的刑法,它就不适用于在其生效之前实施的行为。同样,如果现行法律被废除,则不能再将其作为起诉或定罪的依据。瑞士刑法典》第 1 条体现了一项基本法律原则,即只有法律明确禁止的行为才能受到刑事制裁,从而保护个人权利。这一原则是法治的基石,有助于提高公众对刑事司法系统的信心。 | |||

在刑法中,法律作为界定罪行和适用刑罚的来源,发挥着首要和排他性的作用。这一原则是许多法律制度的核心,它确保只有议会或相关立法机构制定的法律才能明确规定哪些行为构成犯罪并确定相应的处罚。这种做法对司法系统和整个社会有几个重要影响。首先,它确保了刑法的明确性和透明度。例如,如果立法明确规定盗窃及其变种属于刑事犯罪,并确定了监禁或罚款等处罚范围,那么公民就能准确、方便地了解哪些行为是非法的,以及这些行为的潜在后果。这种方法还能保护个人免受专横和滥用权力之害。它防止司法或行政当局追溯性地制定或适用法律,或对实施时不被视为违法的行为进行处罚。这意味着司法判决必须严格以先前存在的法律为依据。刑法不溯及既往是这一方法的一个重要方面。它确保只能根据被指控行为发生时有效的法律对个人进行审判和处罚,从而避免不可预测和不公正的处罚。 | |||

刑法中的合法性原则是许多法律体系的基石,它以三条基本格言为基础,这些格言共同保证了法律的公平和可预测的适用。这些格言深深植根于法理之中,构成了防止任意性的堡垒,并确保国家在刑事事项上行使权力时尊重个人权利。 | |||

第一条格言是 "法无明文规定不为罪"(nullum crimen sine lege),它规定,除非法律在行为发生前明确将其定为犯罪,否则不能将该行为视为犯罪。这一规则对刑法的可预测性至关重要,它使公民能够了解其行为的合法性界限。例如,如果立法者决定将一种新的在线行为定为犯罪,那么该行为只有在新法律颁布之后才会成为犯罪,而在该法律颁布之前的类似行为则不能被起诉。第二条格言是 "法无明文不为罪",确保除法律明文规定的处罚外,不得实施其他处罚。这可确保个人了解犯罪行为的潜在后果,并防止法官施加现行法律未授权的处罚。这一规则保护个人免受意外制裁或司法发明的新刑罚。最后,"法无明文规定不为罪"(nulla poena sine crimine)的格言强调,只有在法律认可某行为为犯罪的情况下,才能实施处罚。这一规则确认,刑事定罪需要证明法律规定的罪行。例如,只有当一个人的行为符合欺诈的法律定义,并且其罪行得到确凿无疑的证明时,才能判定其犯有欺诈罪。这些原则在保护公民权利、确保公平透明地适用刑事司法方面发挥着至关重要的作用。通过要求法律明确界定犯罪和刑罚,这些规则增强了公众对刑事司法系统的信心,同时确保司法权不会以滥用或任意的方式行使。 | |||

"法无明文不为罪"、"法无明文者不罚 "和 "法无明文者不为罪 "的格言所表达的合法性原则的后果也延伸到刑事诉讼规则中,强调了合法性在司法中的至关重要性。根据这一原则,不仅罪行和刑罚必须由法律规定,而且程序规则本身也必须植根于法律并符合基本权利。这一要求确保了从调查到判决和执行刑罚的整个司法程序都遵循法律规定的清晰明确的规则。这包括被告在调查和审判期间的权利、如何收集和提交证据、审讯程序以及可以进行或推迟审判的条件等方面。出于多种原因,制定支持刑事诉讼的法律至关重要。首先,它确保司法程序中涉及的个人权利,尤其是被告的权利得到尊重。例如,法律通常会规定获得法律援助的权利、获得公平审判的权利以及在合理时间内接受审判的权利。其次,法律规定的程序可以防止司法系统中的任意性和滥用权力。法官和检察官有义务遵守预先确定的规则,这就限制了主观或不公正裁决的风险。最后,遵守以法律为基础的程序规则可加强司法系统的合法性和透明度。这样,公民就能保证法律程序是按照民主原则公平进行的。 | |||

合法性原则植根于《宪法》的基础,在法律和民主秩序的结构和运作中发挥着至关重要的作用。该原则以若干关键概念为基础,共同确保公平和透明的治理。该原则的核心是法律至上,规定所有行动,无论是个人、公司还是国家代理人,都必须遵守既定法律。这种至高无上的地位确保了国家权力在法律框架规定的范围内行使,从而保护公民免受任意行为之害。例如,如果政府希望出台新的环境法规,那么这些法规必须根据现行法律制定,不能在没有法律依据的情况下单方面强加于人。同时,法律依据要求规定所有国家行为都必须有法律依据。这意味着,政府的决定,无论是涉及公共政策还是个人干预,都必须有现行法律作为依据。这一法律依据要求对于保持公共行政的问责制和透明度至关重要。例如,如果市政府决定增加地方税收,那么这一决定必须有授权增加税收的法律作为依据。最后,基于诚信原则的程序规则的应用是公正和公平的额外保障。这要求参与司法或行政程序的各方正直诚信。这一原则可防止滥用程序谋取不正当利益或妨碍司法公正。例如,在审判中,这意味着双方律师必须诚实地提出论点和证据,不得试图误导法庭或操纵诉讼程序,使其对自己有利。合法性原则的这些方面共同创造了一种环境,在这种环境中,国家权力得到负责任的行使,公民的权利和自由得到深切的尊重。它们加强了法治和公众对机构的信心,确保法律得到公平、统一和透明的实施。 | |||

在司法系统中,程序本身不得成为目的这一观点至关重要。当程序取代司法本身时,法律制度就有可能忽视其首要目标:确保公平公正的司法。过分强调程序的危险在于,它可能导致形式重于实质的情况,即严格遵守形式和程序规则可能会掩盖对真相和正义的追求。在这种情况下,一些微小的程序细节可能会使关键证据失效或妨碍审判的公正进行,从而导致司法不公或不合理地拖延结案。为防止程序取代司法,法官、检察官和律师等负责适用程序的人员必须坚决遵守诚信原则。这意味着他们必须将程序规则作为促进发现真相和司法公正的工具,而不是作为获得技术优势或阻碍司法程序的手段。因此,司法官员必须确保程序服务于司法利益,并以保护当事人权利的方式适用,同时努力实现案件的公平和及时解决。这包括确保程序不被滥用或过度使用,以免破坏审判的公正性或不适当地拖延司法。 | |||

=== | === 诚信原则 === | ||

The principle of good faith, particularly in Swiss law, is an essential concept that guides interactions and behaviour within the legal framework. This principle applies both to the State and to private individuals and is enshrined in the Swiss Constitution (see art. 5 para. 3 of the Constitution) and in the Swiss Civil Code (CC) (see art. 2 para. 1 CC). | The principle of good faith, particularly in Swiss law, is an essential concept that guides interactions and behaviour within the legal framework. This principle applies both to the State and to private individuals and is enshrined in the Swiss Constitution (see art. 5 para. 3 of the Constitution) and in the Swiss Civil Code (CC) (see art. 2 para. 1 CC). | ||

Version du 13 décembre 2023 à 17:47

法律入门:关键概念和定义 ● 国家:职能、结构和政治制度 ● 法律的不同部门 ● 法律渊源 ● 法律的主要形成传统 ● 法律关系的要素 ● 法律的适用 ● 法律的实施 ● 瑞士从起源到20世纪的发展 ● 瑞士的国内法律框架 ● 瑞士的国家结构、政治制度和中立 ● 19世纪末至20世纪中叶国际关系的演变 ● 世界组织 ● 欧洲组织及其与瑞士的关系 ● 基本权利的类别和世代 ● 基本权利的起源 ● 十八世纪末的权利宣言 ● 二十世纪基本权利普遍概念的构建

诉讼和管辖权

法律在社会中的有效适用,关键取决于法律行动与法院管辖权之间的互动。法律行动是个人或实体提起法律诉讼以主张权利或纠正错误的过程。如果没有这一举措,许多权利将停留在理论上。例如,如果没有环保团体的法律行动,重要的环境保护法律就可能无法实施。

另一方面,管辖权是指法院审理和裁决案件的权力。法律行动要想有效,这种权力是必不可少的。以版权纠纷为例。如果将此类案件提交给一个没有适当管辖权的法院,版权就无法得到有效保护。当这两个要素有效地结合在一起时,它们就构成了强大法律体系的基础。法院通过审理诉讼和作出裁决,在法律的适用和解释方面发挥着核心作用。这些裁决反过来又形成判例法,为今后法律的适用提供指导。例如,美国历史上的民权判决塑造了今天解释和适用平等法律的方式。

这一过程的一个重要方面是法院判决的执行。如果法院判决得不到有效执行,它就失去了价值。以一项有利于交通事故受害者的损害赔偿判决为例。如果判决得不到执行,受害者就得不到应得的赔偿,法律的效力就会受到质疑。公众对法律制度公正性和有效性的看法也对法律的实施起着重要作用。如果公民相信法律制度的公正和公平,他们就更愿意尊重法律,并利用法律制度维护自己的权利。反之,缺乏信心则会导致不愿通过法律渠道寻求补救,从而削弱法律的实施。

法律行动对法律的有效实施起着至关重要的作用。这一概念的基本思想是,只有当权利持有人能够在国家或其他当局的帮助下行使权利时,权利才真正存在。换句话说,一项权利,无论在法律中是如何规定的,只有在被赋予权利的人能够积极主张和捍卫它时才具有价值。在这种情况下,法院是制裁权利的重要机制。当个人或实体的权利受到侵犯时,他们可以求助于法院以获得补救。例如,在违反合同的情况下,权利人可以向民事法庭提起诉讼,要求履行合同义务或获得损害赔偿。这种动态突出了诉诸司法的重要性。要使权利真正有效,个人不仅要了解自己的权利,还要有实际能力在相关法院维护自己的权利,这一点至关重要。这包括法院的可用性、法律费用的可负担性以及对法律程序的理解等方面。国家在这一过程中起着决定性的作用。这不仅是一个立法和创造权利的问题,也是一个建立高效、便捷、能够处理争端和执行裁决的司法系统的问题。因此,独立公正的司法机制是法治的基本支柱。

管辖权的概念对法律制度的运作至关重要。它代表着国家的活动,国家通过其司法机构,承担着通过适用法律进行审判和伸张正义的任务。这一概念不仅包括法庭和法院,还包括法官和其他负责解决冲突和执行法律的司法人员。管辖权是指赋予这些司法机构审理和裁决案件的权力。这种权力可能由地理标准(争端发生地)、争端性质(如民事、刑事或行政案件)或司法级别(初审法院、上诉法院等)决定。司法机构在这一过程中的作用至关重要。作为民主的支柱,司法机构独立于立法和行政等其他政府部门行事。这种独立性是确保公平公正司法的基础。例如,在公民与国家之间发生争议时,法院必须能够在不受外界影响或压力的情况下对案件做出判决。法院通过其审判活动,适用法律并做出裁决,然后予以执行,从而促进冲突的解决。这包括对刑事犯罪施以刑罚,通过裁定当事人的权利和义务解决民事纠纷,以及审查行政决定。

法律制度提供一般诉讼权,这是一个基本概念,确保任何主观权利的持有者都可以采取法律行动来执行该权利或确定其存在。这种诉讼权是法治的支柱,确保个人权利不仅仅是理论上的宣言,而是实实在在的、可执行的特权。在实践中,这意味着当个人或实体认为自己的权利受到侵犯或被忽视时,他们可以向国家司法机构寻求补救或承认。例如,在财产权受到侵犯的情况下,所有者可以采取法律行动收回财产或获得损害赔偿。同样,在就业权利方面,如果出现不公平解雇或不遵守法定工作条件的情况,雇员可以向就业法庭提起诉讼,维护自己的权利。出于以下几个原因,这种一般诉讼权至关重要。首先,它为个人提供了维护自身权益的具体途径。其次,它有助于防止滥用权力和非法行为,因为这些行为可以在法庭上受到质疑。最后,它增强了人们对法律制度和政府的信心,因为它表明权利是可以实施的,如果这些权利受到侵犯,公民可以得到补救。因此,诉权是任何实用法律制度的基本特征,反映了国家支持和落实公民权利的能力和意愿。

在法律领域,法律诉讼分为民事、刑事和行政三类,反映了社会中可能出现的冲突和争端的多样性和复杂性。每一类诉讼都能满足解决纠纷、维护社会和法律秩序的特定需求。民事诉讼是指个人、企业或其他实体因合同纠纷、人身伤害索赔或财产纠纷等问题而发生的冲突。例如,如果一个人因另一个人的疏忽而遭受损失,他可以提起民事诉讼,要求赔偿损失。同样,如果发生合同纠纷,当事人也可以诉诸民事法庭解决纠纷。民事诉讼的重点是纠正所遭受的伤害,通常是通过经济赔偿。另一方面,刑事诉讼涉及国家对个人或实体有害社会的行为采取行动的情况。例如,在盗窃或攻击案件中,国家通过检察官起诉被指控的罪犯。刑事制裁可能包括监禁、罚款或社区服务,旨在惩罚和威慑犯罪行为,同时保护社区。行政诉讼通常涉及公民或企业与政府当局之间的纠纷。例如,个人可能会对有关建筑许可、环境法规或税务问题的决定提出质疑。行政诉讼用于质疑政府机构所作决定的合法性或正确性,并确保这些决定尊重法律和公民权利。这些不同类别法律诉讼的存在,体现了法律制度适应社会生活多面性的方式。无论是在私人领域、与国家的关系中,还是在保护公共秩序和社会利益的背景下,它们都提供了多种寻求正义的方式。如果我们要充分、公平地应对不同类型的冲突,并确保个人权利与集体需求之间的平衡,法律行动的这种多样化是至关重要的。

非诉讼纠纷解决方式

现代法律制度的一个重要特点是,除国家司法机构外,还可诉诸其他司法机构。这些替代司法管辖区为解决争端提供了更多选择,同时又不损害国家法官的权威或合法性。仲裁就是替代性司法管辖的一个显著例子。在仲裁中,争议各方同意将争议提交给一名或多名仲裁员,仲裁员的裁决通常具有约束力。这种机制常用于国际商业纠纷,因为与传统法院相比,当事人更喜欢更灵活、更快捷的程序。仲裁因其保密性、专业性和跨越国家管辖界限的能力而尤其受到青睐。另一种替代管辖形式是调解。与仲裁和法院诉讼不同,调解是一种更具协作性的方法,由调解员帮助当事人达成双方都满意的协议。调解通常用于家庭纠纷,如离婚,在这种情况下,人们希望采用对抗性较弱的方法。

这些替代性司法管辖并不寻求取代州法院,而是提供解决争议的补充方式。事实上,它们可以减轻传统法院的负担,为某些类型的冲突提供更合适的解决方案。更重要的是,通过仲裁或调解达成的裁决往往可以由州法院执行,这表明这些制度之间存在一定的和谐性和互补性。这些替代性司法管辖区的存在说明了法律体系的多样性和适应性,以满足社会的不同需求。它们与州法院协同运作,加强了整体法律框架,并为诉讼当事人提供了更多解决争议的选择。

尽管仲裁和调解等替代性司法管辖机构为解决争议提供了补充性选择,但它们的使用往往取决于国家的授权或法律框架的建立。这一规定确保了替代性司法管辖区与国家法院之间的协调互动,同时保证了对基本权利的保护和对法律标准的遵守。例如,在私法领域,商业合同的当事人可以在合同中加入仲裁条款,规定由合同引起的任何争议都将提交仲裁,而不是普通法院。但是,这一规定必须符合有关仲裁的国家法律,这些法律规定了国家授权和承认仲裁的标准和条件。

在公法中,特别是在涉及政府实体的争议中,仲裁或调解的使用可能更为复杂,而且往往受到主权和公共利益考虑的限制。例如,某些涉及国家或其机构的争议可能不符合仲裁条件,因为需要保护公共利益并遵守既定的行政程序。在国际法中,仲裁发挥着重要作用,尤其是在解决跨境商业争端或投资者与国家之间的争端方面。承认及执行外国仲裁裁决纽约公约》等国际公约为跨国界使用和执行仲裁裁决提供了便利。然而,即使在这种情况下,各国仍可通过本国立法控制国际仲裁的适用。因此,尽管替代性司法管辖区丰富了法律景观并提供了具体优势,但其实施仍受国家法律管辖。这种监管对于确保这些替代性争端解决机制的公平性、合法性和有效性,同时维护既定法律秩序和保护基本权利至关重要。

谈判和会谈

谈判在国际公法中发挥着至关重要的作用。谈判是一种解决冲突的方法,有关各方通过直接对话解决分歧。这种方法在国际关系中尤为重要,因为国家和国际组织往往寻求通过外交手段而非诉讼来解决分歧。

在谈判中,冲突各方的代表会面讨论争议问题,探讨可能的妥协方案,并达成双方都能接受的协议。这一过程可涵盖广泛的主题,从领土争端和贸易协定到环境问题与和平条约。在国际法中,谈判的优势在于其灵活性,能够根据所有相关方的具体利益,量身定制解决方案。仲裁或诉讼由第三方(如法院或仲裁员)强制做出决定,而谈判则不同,它允许各方控制过程和结果。

成功利用谈判的一个显著例子是通过外交达成国际协议,如军备控制条约或气候变化协议。在这些情况下,国家代表就协议条款进行谈判,寻求在本国利益与其他国家和整个国际社会利益之间取得平衡。然而,谈判需要各方愿意进行对话和妥协,而这种意愿并不总是存在。此外,各方之间的权力不平衡也会影响谈判进程和结果。尽管存在这些挑战,谈判仍是国际公法领域以和平和建设性方式处理国家间关系的重要工具。

在国际谈判中,利用第三方进行 "斡旋 "是一种常见且通常有益的做法。第三方通常是一个国家、一个国际组织,有时也是一个以经验丰富和公正著称的个人,它充当调解人的角色,帮助冲突各方开展对话,找到共同点。第三方斡旋的作用有别于调停人或仲裁人。提供斡旋的第三方不直接参与谈判或提出解决方案,而是侧重于创造一个有利于讨论的环境。这可能涉及组织当事方之间的会议,提供中立的讨论空间,或提供后勤资源。在双方关系紧张或难以直接沟通的情况下,第三方通过斡旋进行干预尤其有用。第三方只促进谈判进程,不参与讨论内容,有助于重建或保持畅通的沟通渠道,这对达成协议至关重要。

历史上使用斡旋的例子包括中立国家或国际组织帮助促进冲突国家之间和谈的情况。例如,第三国可以提供其首都作为和谈的会面地点,或者国际组织可以为谈判进程提供技术援助。通过提供中立框架和促进对话,斡旋在和平解决国际冲突方面发挥着重要作用。斡旋使各方能够克服沟通障碍,以更具建设性的方式共同解决分歧。

斡旋 "是一种中介形式,由第三国(有时是国际组织)发挥促进作用,帮助冲突双方在最佳条件下进行谈判。斡旋的概念不同于调解或仲裁,因为第三方并不直接干预谈判的内容。相反,他们的作用是创造一个有利于对话和解决冲突的环境。在斡旋方面,提供服务的第三国或组织一般通过提供中立的会谈场所、帮助建立各方之间的沟通渠道、提供后勤资源或技术援助来采取行动。这样做的目的是缓和紧张局势,促进更平静、更具建设性的谈判进程。斡旋的一个重要方面是冲突各方保留对谈判的完全控制权。他们可以自由确定讨论的条件,选择要讨论的主题,并决定要达成的协议。提供斡旋的国家或组织的作用是支持这一进程,而不直接施加影响。在双方因关系紧张或不信任而无法或不愿进行直接对话的情况下,这种方法尤为有用。斡旋可以通过提供中立的框架和后勤支持来帮助克服这些障碍,从而鼓励更具建设性的参与。从历史上看,在许多外交场合,特别是在和平谈判或国际协定中,使用斡旋至关重要。例如,中立国可以主持两个冲突国家之间的和平谈判,为讨论提供便利,但不参与谈判内容。

瑞士在提供斡旋,特别是在国际危机情况下提供斡旋方面的传统作用得到了认可。瑞士的中立历史及其作为公正调解人的声誉使其能够在若干国际冲突中发挥这种促进作用。瑞士利用斡旋的一个显著例子涉及瑞士与古巴的关系。冷战期间,瑞士充当了古巴和美国之间的中间人。1961 年美国与古巴断交后,瑞士同意在古巴代表美国的利益,扮演保护国的角色。瑞士以此身份促进了两国之间的沟通,这在局势高度紧张时期(如 1962 年古巴导弹危机)尤为重要。作为保护国,瑞士不参与美国和古巴之间的讨论内容,但它提供了一个重要的沟通渠道,使双方即使在没有正式外交关系的情况下也能保持对话。这一作用维持了几十年,直到 2015 年美国与古巴恢复关系。瑞士和古巴的案例是一个很好的例子,说明第三国如何通过其中立立场和外交承诺,为缓解国际紧张局势和促进冲突国家之间的沟通做出重大贡献。瑞士的这一斡旋传统继续在世界外交中发挥重要作用,为和平解决冲突提供了宝贵的途径。

调解

调解是一种解决冲突的过程,在这一过程中,争议各方依靠调解人促进讨论并提出解决方案。调停人通常因其专业知识、公正性和声望而被选中,在帮助各方探讨解决方案和理解彼此观点方面发挥着至关重要的作用。与法官或仲裁员不同,调解员无权强加解决方案。相反,他们的作用是引导各方达成彼此都能接受的协议。他帮助澄清争议问题,确定共同利益,并鼓励各方找到共同点。调停员可以提出解决方案,但是否接受或拒绝这些建议由当事方决定。

调解的优势在于其灵活性和非对抗性。由于各方可以直接控制谈判结果,他们往往更倾向于遵守最终协议。此外,调停还可以维护甚至改善当事人之间的关系,这在纠纷解决后当事人需要继续互动的情况下尤为重要,例如在家庭或商业案件中。调解可用于各种情况,包括商业纠纷、雇佣纠纷、家庭纠纷,甚至在一些国际外交案件中。例如,在离婚案件中,调解员可以帮助夫妻双方就子女监护权或财产分割等问题达成协议,而无需经过可能耗时耗资的审判。

调解是一种在私法和国际法中都适用的争议解决工具,它提供了一种灵活且通常更具协作性的争议解决方法。在私法方面,调解常用于解决雇佣纠纷、家庭纠纷和私人当事方之间的其他纠纷。例如,在雇佣纠纷中,调解员可以帮助解决雇主与雇员之间或工会与管理层之间的纠纷,通常是通过寻找共同点来避免审判的成本和公开性。同样,在家庭纠纷(如离婚或子女监护权纠纷)中,与诉讼相比,调解以一种对抗性较弱、更加个性化的方式帮助各方就敏感问题达成协议。在国际法领域,调解也是一种宝贵的工具,尤其是在解决国家间冲突或涉及国际行为者的争端时。这些案件的调解人可以是第三方国家、国际组织或具有公认专业知识和权威的个人。国际调解的目的是通过外交途径和平解决冲突,否则可能造成严重后果,从政治紧张局势到武装冲突,不一而足。

在所有这些情况下,调解的优势在于它能够提供量身定制的解决方案,考虑到各方的具体利益和需求。它还能促进沟通和相互理解,这对于维持现有关系或在国际冲突中确保持久和平至关重要。因此,调解是一种灵活有效的解决冲突方法,适用于多种情况,无论是涉及私法还是国际法。

调解

调解是一种解决争议的程序,其目的是让争议各方走到一起,找到友好的解决方案。友好 "一词源于拉丁语 "amicabilis",意思是 "能够由朋友解决 "或 "以友好的方式"。在法律语境中,"友好 "一词强调的是解决争议的合作性、非对抗性。在调解过程中,调解人通常是中立的,他帮助当事人讨论他们之间的分歧,并自行找到双方都能接受的解决方案。与调停人不同的是,调解人有时会更积极地提出解决方案。不过,与调停一样,最终决定权始终在当事人手中,调解员无权强加协议。

在当事人之间保持或恢复良好关系非常重要的情况下,调解尤为重要。调解常用于商业纠纷、劳动纠纷和家庭纠纷等情况。例如,在企业中,调解员可以帮助解决雇主和雇员之间的争议,在不诉诸正式审判的情况下找到满足双方需求的协议。友好 "一词反映了调解的精髓:本着合作和相互理解的精神,而不是通过诉讼找到解决办法。这通常有助于维护积极的关系,并找到更具创造性和个性化的问题解决方案。

调解指的是一种解决冲突的方法,在调解人的帮助下,当事双方通过谈判达成解决方案,通常不那么正式,也不那么受严格的法律规则约束。调解的主要目的是达成友好协议,而不是根据严格的法律确定谁 "对 "谁 "错"。在这一过程中,调解人(在某些法律体系中有时可能是法官)扮演着促进者的角色。调解员不像法官那样在审判中对争议做出裁决,而是帮助双方当事人探索达成协议的可能性,并了解彼此的观点和利益。这样做的目的是鼓励双方找到彼此都能接受的解决方案。

这种方法尤其适用于争议解决后双方仍需保持持续关系的情况,如家庭或商业案件。调解能以更灵活、对抗性更小的方式解决争议,有助于维护双方关系,而且往往能找到更适合双方具体需求的解决方案。调解的优势之一是,它允许解决纠纷中并非严格意义上的法律问题。例如,可以将情感、关系或实际考虑因素纳入谈判,而这在更为正式的法律框架内是不可能的。

调解作为解决争端的初步措施,在某些法律制度中,特别是在家庭法领域,往往受到鼓励,有时甚至被要求。法官在处理纠纷时,尤其是在离婚、子女监护或继承纠纷等敏感案件中,可能会在启动正式法律程序之前,首先尝试引导当事人达成友好的解决方案。这种做法反映了一种认识,即在许多情况下,通过协商和协商一致的方式解决问题可能对所有相关方都更有利,尤其是在关系到个人关系的情况下。调解不仅能解决当前的争议,还能维护甚至改善当事人之间未来的关系,这在家庭法等情况下至关重要。不过,必须强调的是,是否接受调解中提出的解决方案完全取决于当事人的意愿。法官或调解员可以促进讨论,鼓励双方找到共同点,但不能强迫他们接受协议。当事人保留自主权,如果他们认为调解方案不符合他们的利益或需要,他们有权拒绝调解方案。在某些法律体系中,调解可能是启动法律程序之前的一个强制性步骤。这一义务旨在减少诉诸法院的争议数量,并鼓励更快、更少对抗性地解决争议。不过,如果各方未能通过调解达成协议,他们仍保留由法官裁决争议的权利。

仲裁

仲裁是一种解决争议的方法,由争议双方选定的一名或多名仲裁员负责解决争议。这一程序在许多方面不同于传统的法律程序,包括当事人可以选择仲裁员,这是仲裁的一大优势。在仲裁中,当事人通常通过合同中的仲裁条款或争议发生后的仲裁协议,同意将争议提交给一名或多名专门指定的仲裁员。这些仲裁员可能是争议所涉领域的专家,具有传统法官可能不具备的专业技术知识。仲裁的一个重要方面是,仲裁员做出的决定(即裁决)通常是终局的,对当事人具有约束力。该裁决具有与法院判决类似的法律效力,在大多数司法管辖区,可以与法院判决一样的方式执行。

仲裁在国际商事纠纷中特别受欢迎,因为与传统的国家法院相比,仲裁具有多种优势。这些优势包括保密、快速、程序灵活,以及当事人可以选择具有与争议相关的特定专业知识的仲裁员。此外,由于《关于承认和执行外国仲裁裁决的纽约公约》等国际公约的存在,仲裁裁决在国际上比国家法院的判决更容易得到承认和执行。不过,需要注意的是,与由法律系统指定法官的司法程序不同,仲裁依赖于当事人的协议来选择仲裁员,这就强调了双方同意在这一过程中的重要性。仲裁允许当事人选择自己的 "法官",因此具有一定程度的个性化和专业化,而这在普通法院诉讼中往往是不可能实现的。

仲裁作为一种解决争议的方法,可以通过在合同中使用仲裁条款,在出现具体争议之前很早就确定下来。该条款是一项预期条款,规定如果合同出现争议,双方承诺通过仲裁而非普通法院解决。这种做法在许多类型的合同中都很常见,尤其是国际商业协议,因为它能提供更可预测和更专业的争议解决方式。

在合同中加入仲裁条款表明了当事人的精心策划。通过预测未来可能出现的分歧,当事人寻求确保一种有效且适合其特定需求的解决方法。在国际贸易等复杂领域,这种方法尤其有用,因为在这些领域,争议可能需要特定的专业知识,而当事人希望避免不同国家法律体系带来的不确定性。例如,在一份国际建筑合同中,仲裁条款可以规定,与合同解释或工程履行有关的任何争议将由精通建筑法和相关国际标准的仲裁员解决。这种特殊性确保了被选中的仲裁员具备必要的专业知识,能够理解并有效解决争议。仲裁条款的存在也反映了双方同意采用替代性争端解决方式。这种对仲裁的偏好表明,双方都希望对争议解决过程保持一定程度的控制,同时受益于更加个性化且可能较少对抗的方式。

特别仲裁是一种在争议发生后专门适用于特定案件的仲裁形式。在这种仲裁中,与根据合同中的仲裁条款进行仲裁不同,当事人只是在争议发生后才决定选择仲裁作为争议解决方式。在这种情况下,争议各方共同商定将争议提交临时仲裁。然后,他们必须就仲裁程序的一些重要方面达成一致,如仲裁员的选择、应遵循的程序规则、仲裁地点和仲裁使用的语言。这种灵活性使当事人可以根据争议的具体情况调整仲裁程序,这可能是一个相当大的优势。例如,在没有事先仲裁条款的协议签订后出现的商业争端中,相关公司可以选择使用临时仲裁来解决问题。他们可以决定指定一个由其特定业务领域专家组成的仲裁员小组,从而建立一个满足其特定需求的定制程序。临时仲裁通常被认为比机构仲裁更灵活,后者遵循特定仲裁机构预先制定的规则。然而,这种灵活性也可能导致额外的复杂性,尤其是在仲裁程序的组织和管理方面。因此,当事人在确定临时仲裁的条款时必须谨慎、明确,以避免日后出现复杂情况。

仲裁协议是已发生争议的当事各方决定将该具体争议提交仲裁的协议。这类协议不同于仲裁条款,后者是在争议发生前拟定并包含在合同中的。而仲裁协议是一种临时协议,专门为解决现有争议而制定。在仲裁协议中,双方当事人准确界定提交仲裁的争议事项,并商定仲裁的具体条款,如仲裁员人数、遵循的程序、仲裁地点,有时还包括争议适用的法律。这种协议通常是合同性的,必须仔细起草,以确保明确界定争议和仲裁程序的所有相关方面。

仲裁协议的优势在于它能为特定争议提供量身定制的解决方案,允许当事人选择符合其特定需求的程序。例如,如果两家公司对交付货物的质量有争议,他们可以决定使用仲裁协议解决争议,并选择在国际贸易和产品质量方面有专业知识的仲裁员。选择折衷仲裁通常是因为它具有保密性、快捷性和灵活性等优点,而且可以通过仲裁员获得特定的专业知识。此外,由于仲裁裁决通常是终局性和可执行性的,当事人可以高效、最终地解决争议。

仲裁已成为一种越来越受欢迎的解决争端的手段,尤其是在国际法领域和公司领域。仲裁之所以越来越受欢迎,是因为它与传统的法律程序相比具有许多优势。在国际范围内,仲裁因其中立性而尤其受到青睐。来自不同背景的当事方可以避免接受另一方国家法院的管辖,因为这可能会被视为一种优势或担心存在偏见。此外,国际仲裁克服了语言障碍和法律制度差异,为解决争端提供了一个更一致、更可预测的框架。

在商界,尤其是在国际商业合同中,仲裁之所以受到青睐,原因是多方面的。与普通法院相比,仲裁程序通常更简单、更快捷、更谨慎。保密性是仲裁的一大优势,它使公司能够在不引起公众注意或暴露敏感商业细节的情况下解决争议。这种谨慎性对于维护商业关系和公司声誉至关重要。事实上,据估计多达80%的国际商业合同都包含仲裁条款,这证明了国际贸易中人们对仲裁的强烈偏好。这些条款使当事人能够事先约定以仲裁作为解决争端的手段,从而保证了仲裁过程更可控、更可预测。

至于仲裁的组织,欧洲和世界上许多商会都建立了自己的仲裁机构。这些机构为仲裁提供框架和规则,有助于仲裁的标准化和效率。著名的例子包括国际商会 (ICC) 和伦敦国际仲裁院 (LCIA),它们在国际商业纠纷中得到广泛认可和使用。因此,仲裁已牢固确立了其在国际法和商业世界中作为解决争端的重要工具的地位,为传统的法院系统提供了一种高效、灵活和谨慎的替代方式。

仲裁(尤其是在商事纠纷中)的一个独特而有吸引力的特点是,当事人可以选择在相关领域具有特定专业知识和经验的仲裁员。这与传统的法院系统形成鲜明对比,在传统的法院系统中,法官被指派审理案件,当事人对法官的选择或具体专长没有任何直接控制权。在商事仲裁中,当事人可以灵活选择仲裁员,这些仲裁员不仅具备法律知识,还对与争议有关的特定行业或部门的活动有深入了解。在复杂的案件中,技术知识或对商业惯例的深入了解对评估争议问题和做出明智决定至关重要,因此这种实践专长尤其宝贵。例如,在涉及与建筑有关的技术问题的争议中,各方可能会选择让具有工程或建筑经验的个人加入仲裁员小组。同样,在涉及国际金融交易的争议中,当事方可能倾向于选择具有金融或国际商业法专业知识的仲裁员。这种选择具有相关专业知识的仲裁员的能力有几个好处。它确保决策者了解争议的细微差别,更有能力评估所提出的技术或专业论点。此外,它还能更有效地解决争议,因为有能力的仲裁员可能会更快地发现关键问题并提出适当的解决方案。

阿拉巴马仲裁案是国际仲裁史上的著名案例,在国际法的发展中发挥了重要作用。该案可追溯到 1872 年 9 月 15 日,当时英国因美国在美国内战期间违反中立义务而被勒令向美国支付巨额赔偿。

在这场战争中,正式采取中立立场的英国允许包括阿拉巴马号战舰在内的军舰从其造船厂建造并交付给邦联(南方)军队。这些军舰随后被南军用来袭击联邦(北方)商船,造成了巨大损失。美国认为这些行为违反了英国的中立原则,并要求对这些船只(尤其是阿拉巴马号)造成的损失进行赔偿。战争结束后,为避免紧张局势升级和可能发生的军事冲突,两国同意将争端提交瑞士日内瓦的国际仲裁法庭。由多个国家的代表组成的仲裁庭得出结论,英国允许邦联建造和交付这些船只,是对其中立义务的疏忽。因此,英国被勒令向美国支付巨额赔偿。阿拉巴马仲裁案的重要性在于其对国际法及和平解决国际争端的影响。此案不仅促进了仲裁作为解决国际争端的一种手段的正常化,还加强了日内瓦作为外交和国际法重要中心的地位。此外,这一事件标志着承认中立法重要性的一个转折点,并影响了随后有关中立国权利和义务的国际公约和条约的发展。

庭审双方

在民事诉讼中,当事人(即原告和被告)之间的角色和动态对案件的进展和结果至关重要。原告是提起法律诉讼的一方。原告提起诉讼的动机一般是感到自己遭受了损失或权利受到了侵犯,从而促使他从法律系统寻求某种形式的补偿或正义。例如,在合同纠纷中,原告可能是一家公司,起诉商业伙伴违反合同条款。另一方面,被告是法律索赔所针对的一方。这意味着被告应该对原告造成了伤害或侵犯了原告的权利。被告在民事诉讼中的角色是回应对他的指控。这种回应可以采取多种形式,例如对原告指控的事实提出异议,对事件提出不同的说法,或提出法律论据反驳原告的主张。以财产纠纷为例:被告可能是房东,被房客指控未遵守租约条款。

法庭程序为双方提供了一个平台,让他们可以在听证会上以书面或口头形式提出自己的论点、证据和可能的证词。这可以确保争议双方都能得到法官或法官小组的审理和公平评估,具体取决于现行的法律制度。在考虑了所有提交的信息和论据后,法官会做出裁决以解决争议。这种民事审判结构明确界定了原告和被告的角色,旨在确保每个案件都能得到公平公正的处理,从而促进社会正义和纠纷的妥善解决。

镇压犯罪和维护公共秩序是国家的基本职责之一,这一点在刑事诉讼中得到了明确体现。与个人或私人实体寻求纠正错误或纠纷的民事诉讼不同,刑事诉讼侧重于社会对被认为违反其法律的行为的反应。

在刑事司法系统中,由国家主动起诉刑事犯罪。这种行动通常由作为社会代表的检察官负责。刑事诉讼的目的不仅在于弥补对受害者造成的伤害,还在于通过惩罚罪犯和阻止其他人犯下类似罪行来预防未来的犯罪。提起刑事诉讼的方式多种多样。在许多情况下,通常是在警方或其他执法机构进行调查之后,由国家依职权启动。例如,在抢劫或攻击案件中,警方调查犯罪并向检察官报告调查结果,然后由检察官决定是否有足够的证据起诉。

在某些法律体系中,犯罪受害者或其他当事人也可以在提起刑事诉讼方面发挥作用。他们可以通过向有关当局提出申诉来做到这一点。不过,即使在这些情况下,最终也是由检察官代表社会决定是否对案件提起诉讼。因此,刑事诉讼与民事案件之间的区别至关重要。民事案件涉及私人之间的纠纷,而刑事诉讼则涉及以国家为代表的整个社会,国家旨在惩罚犯罪行为并维护公共秩序。这种做法反映了这样一种认识,即某些行为不仅伤害特定个人,也伤害整个社会。

检察官是司法系统中的一个关键机构,在法庭上代表法律和维护国家利益方面发挥着至关重要的作用。检察官办公室由检察官或国家律师等治安法官组成,负责刑事起诉和执法,重点是维护公共秩序和起诉犯罪行为。检察官办公室的结构因法律制度而异,瑞士就是一个具体的例子,联邦法律制度影响着检察官办公室的组织结构。在瑞士各州,检察官办公室自主运作,由一名检察官领导。总检察长通常由人民直接选举产生,体现了瑞士的民主传统,并确保以透明和负责任的方式代表公众利益。在州一级,总检察长负责监督刑事调查和起诉,确保法律得到公正有效的执行。在联邦一级,检察官办公室采取不同的形式。它由联邦总检察长领导,总检察长由联邦议会选举产生。这一职位尤为重要,因为它负责处理超出州管辖范围或涉及联邦犯罪的刑事案件。例如,在恐怖主义、联邦腐败或危害国家安全等大型案件中,由联邦总检察长负责。瑞士的这一模式说明了如何构建法律体系,以满足联邦制国家的需要,即在地区自治与国家层面的协调之间取得平衡。它确保无论是地方案件还是更大范围的犯罪,都有一个有能力、负责任的机构来起诉并代表社会利益。这确保了司法的一致性,体现了民主和法治的原则。

在刑事司法系统中,检察官在提起刑事诉讼方面发挥着积极主动和自主的作用。与民事案件中必须由一方当事人启动诉讼程序不同,在刑事案件中,检察官可以依职权启动诉讼程序,即无需受害人或另一方当事人事先提出请求。这种依职权行事的能力是检察官权责的基本要素。它反映了这样一种理念,即刑事犯罪不仅是对个人的攻击,也是对公共秩序和整个社会的侵犯。因此,检察官作为国家和社会利益的代表,有责任和权力起诉这些罪行,以维护合法秩序和保护公共福利。这种自主行动可能由各种方式触发,包括警方报告、公民投诉或当局自行调查。例如,如果发现盗窃或杀人等犯罪行为,警方会进行调查,并将调查结果转交检察官。根据这些信息,检察官可以决定起诉,即使受害者不希望起诉或没有人正式要求起诉。这种方法确保了即使在没有私人主动起诉的情况下,严重犯罪或破坏公共秩序的行为也不会逍遥法外。它强化了一项原则,即某些应受谴责的行为需要国家做出反应,以维护社会正义和安全。

刑事诉讼程序

刑事诉讼程序受一套强制性法律规则管辖,旨在确保司法公正和保护所有相关方的权利,尤其是被告或被指控者的权利。这些严格的规则旨在确保诉讼程序公正、透明地进行,并在整个司法程序中尊重被告的权利。

在刑事司法系统中,从调查到审判的每个阶段都有明确的法律标准,当局必须严格遵守。例如,这些标准包括关于如何收集证据、如何讯问嫌疑人以及如何进行审判的规则。不遵守这些规则可能导致证据无效,甚至取消诉讼程序。让我们以搜查为例。要使搜查合法,一般必须获得法官签发的搜查令授权,搜查令的依据是有充分证据证明发生了犯罪行为,并且可以在搜查令指定的地点找到相关证据。这一搜查令要求旨在保护被告的权利,防止任意或滥用搜查。此外,还有关于搜查方式的严格规定,以保护个人财产和隐私。

这些强制性刑事诉讼规则反映了法治的基本原则,包括尊重人权和程序保障。其目的是在调查和起诉刑事犯罪的需要与保护个人自由和确保被告获得公平公正待遇的需要之间取得平衡。通过保持这些高标准,刑事司法系统力求维护公众对司法程序廉正和公正的信心。

辩论式程序和审问式程序

刑事诉讼程序通常被称为刑事调查,是以寻找和管理与犯罪或违法行为有关的证据为中心的重要法律程序。司法程序的这一阶段对于确定刑事案件的事实和确定被告的责任至关重要。

刑事调查一般在举报或发现犯罪或轻罪后开始。随后,警方等相关部门会开展调查,收集证据、询问证人并收集所有必要信息,以确定实际发生的情况。这一阶段可能涉及各种活动,如搜查、扣押、法医分析和其他调查方法。在刑事调查过程中,代表国家和社会的检察官负责监督调查过程,并与调查人员密切合作,对被告进行立案调查。其目的是收集充分证据,排除合理怀疑,证明被告犯有被指控的罪行或违法行为。

必须注意的是,在整个刑事调查过程中,被告的权利必须得到尊重。这包括获得公平审判的权利、聘请律师的权利以及不自证其罪的权利。此外,必须根据现行法律和程序收集和处理所有证据,以确保其在法庭上的可采性。一旦完成刑事调查,如果收集到的证据足以支持指控,则可将案件提交法庭审判。如果认为证据不足,则可撤销案件或释放被告。

根据瑞士刑法,《刑法典》对犯罪和轻罪进行了基本区分,这种区分是根据与每种罪行相关的惩罚的严重程度进行的。这种区分至关重要,因为它决定了适用刑罚的性质,并指导相应的司法程序。

根据《瑞士刑法典》,重罪是可判处三年以上监禁的严重罪行。这些罪行代表了被认为对社会特别有害的行为,如杀人、严重性侵犯或恐怖主义行为。例如,根据《刑法典》,在瑞士被判定犯有谋杀罪的个人将被指控犯有重罪,并可能面临长期监禁,这反映了其行为的严重性。另一方面,轻罪被定义为不太严重的罪行,可处以不超过三年的监禁或罚款。这些罪行包括小偷小摸、小规模欺诈或严重的道路交通违法行为。例如,因商店行窃而被定罪的人可能会被指控为轻罪,并被处以较轻的刑罚,如罚款或短期拘留。

对重罪和轻罪的这种分类反映了瑞士司法制度的一个重要原则:惩罚与所犯罪行的严重性相称。它确保对最严重的罪行保留最严厉的惩罚,同时为处理不太严重的罪行提供适当的法律框架。通过明确界定这些类别,《瑞士刑法典》旨在平衡保护社会、预防犯罪和尊重个人权利之间的关系。

指责性

刑事诉讼程序的历史起源,尤其是在高度重视公民参与治理和司法的社会中。这种古老的刑事诉讼方式的特点是一种司法 "战斗",控辩双方在法官的监督下,在正式而庄严的场合进行对抗。在这些制度中,刑事诉讼通常由正式指控启动。原告或控告者对被告,即被控犯罪或违法的人提出指控和证据。然后,被告有机会针对这些指控为自己辩护,通常是提出自己的证据和论点。法官的职责是裁判这场法律 "战斗"。他们确保程序规则得到遵守,听取双方的论点,并最终做出有利于一方或另一方的裁决。这一裁决可能导致被告被定罪或无罪释放。

这种程序反映了司法被视为一种更直接、参与性更强的冲突解决方式的时代。它是鼓励公民积极参与包括司法在内的公共事务的政治制度的特征。古希腊,尤其是雅典,就是这种制度的典型代表,公民在司法事务中发挥着积极作用。随着时间的推移,随着社会和法律制度的发展,刑事诉讼程序变得更加复杂和制度化,纳入了更多现代司法原则,如无罪推定、法律代表和辩护权。尽管如此,这一程序的基础--对抗式辩论和公正法官的干预以裁决争议--在许多当代法律体系中仍然是刑事司法的基本要素。在刑事诉讼中,起诉的概念是司法程序的关键时刻。在提起诉讼时,被告被正式起诉,这意味着被告被正式告知对其提出的指控,并必须在法庭上对指控做出回答。

在这种情况下,法官的角色通常被比作仲裁员。他的主要职责是确保原告(通常由检察官代表)和被告之间的 "斗争 "依法公平进行。法官确保双方都有机会提出自己的论点、证据和证词,并确保审判的进行充分尊重被告的权利和司法原则。在刑事审判中,法官最重要的任务之一就是对所提交的证据做出裁决。这包括根据证据规则评估证据的相关性、可靠性和可采性。法官还必须确保公平地提交和审议证据,允许双方质疑或支持证据。这种方法反映了许多法律体系中刑事司法的基本原则:公平审判权、无罪推定权和辩护权。法官作为公正的仲裁者,确保这些原则得到尊重,并确保最终判决,无论是定罪还是宣告无罪,都是基于对审判期间所提供证据的公正而严格的评估。

在许多法律体系中,刑事诉讼程序都建立在口头、公开和对抗的结构之上,其中每一个要素都在保证公平透明的审判中发挥着至关重要的作用。刑事诉讼的口头性质意味着审判期间的大部分交流都是当面进行的。证人的证词、辩方和控方律师的论点以及被告的陈述都以口头形式呈现在法官和陪审团面前(如果有的话)。这种交流形式允许在法庭上进行动态和直接的互动。这对于评估证人的可信度和所陈述论点的有效性至关重要。例如,在抢劫案的审判中,目击证人将口头叙述他们所看到的情况,让法官和陪审团评估他们的可靠性和一致性。审判公开是另一个基本支柱。它确保法律程序向公众公开,从而提高透明度,使社会能够监督法律制度的运作。审判的公开性有助于防止不公正,维护公众对司法公正的信心。不过,也可能有保护特定利益的例外情况,例如在某些敏感案件中保护受害者的隐私。诉讼程序的对抗性质确保各方都有机会陈述自己对事实的看法、质疑对方的证据并对指控做出回应。这种方式确保被告有公平的机会为自己辩护。例如,在欺诈案的审判中,辩方有权反驳控方提出的证据、询问控方证人并提出自己的证人和证据。刑事诉讼的这些原则--口头、公开和对抗式诉讼--共同构成了一个平衡、公正的司法框架,对公正执法至关重要。它们有助于确保审判以透明、公正的方式进行,在尊重被告基本权利的同时,力求查明事实真相。

刑事诉讼程序的本质是公平考虑控辩双方的利益和论点,而不采取党派举措。这一公正原则对于保证审判的公平公正至关重要。法官在这些程序中扮演公正仲裁者的角色,确保双方都有机会陈述案情、回应对方的论点并提交证据。他还确保诉讼程序按照法律规则和司法原则进行。诉讼程序的公开性是加强司法程序透明度和公正性的另一个重要方面。通过向公众开放,刑事诉讼使公民能够跟踪法律案件的进展情况,并检查司法是否公正。这种透明度在维护公众对司法系统的信心方面发挥着关键作用。它确保审判不仅在理论上是公正的,而且在实践中也是公正的,任何相关方都可以观察到。例如,在严重罪行的审判过程中,公民可以旁听庭审,从而可以监督被告的权利是否得到尊重,法律程序是否得到正确遵循。这是对司法运作的民主监督,有助于防止滥用或误判。刑事诉讼程序旨在平衡所有相关方的利益,确保司法透明、公正和负责。公正的法官和公开的诉讼程序相结合,为实现这些目标做出了重要贡献。

由于检察机关的资源不足,对犯罪行为的起诉和调查只能由私人主动进行。由于法官不能直接干预,证据管理存在缺陷。因此,被告的利益在某种程度上受到损害。在这种情况下,法官的作用是有限的,这会影响证据管理的方式,并可能损害被告的利益。

如果由受害者或其代表等私人当事方负责进行调查和收集证据,则可能会在收集和提供证据方面出现偏差或不足。如果检方不具备进行彻底调查的资源或专业知识,一些关键证据可能会被忽略,这可能会导致审判中对事实的陈述不完整。此外,如果法官无权直接干预取证,则可能难以确保所有相关和必要的证据都得到考虑。这可能会使被告处于不利地位,特别是如果辩方没有办法或能力有效质疑控方提出的证据。

在公平的司法系统中,被告的利益必须得到保护,尤其是通过保障公平审判权、无罪推定权和充分辩护权。这意味着必须公正、完整地收集和管理证据,法官必须能够确保正确适用证据规则。为了弥补这些不足,一些法律制度加强了公诉机关(如公共事务部)的作用,赋予其进行刑事调查的职责。这样就能以更加平衡和系统的方式收集证据,减少出现偏见的风险,确保更好地保护被告的权利。

没有正式的预审阶段是某些法律制度,特别是美国法律制度的一个显著特点。在刑事诉讼中,预审阶段通常是审判前的准备阶段,在此期间,调查法官会进行彻底调查。调查的目的是收集证据、确认罪犯身份、了解其个性并确定犯罪情节和后果。根据这些信息,治安法官决定采取何种行动,特别是是否应将案件提交法院审判。在美国法律体系中,调查阶段与其他体系(如法国或意大利)中的调查阶段并不相同。在美国,调查一般由警察等执法机构进行,并由检察官监督。一旦被告被捕并受到指控,案件就会直接进入审判准备阶段。证据由控辩双方在审判过程中出示,没有专门的调查法官进行独立的初步调查。

程序上的这种差异会对审判的进行和公正性产生重大影响。在有正式调查阶段的制度中,调查法官在审判前确定事实方面发挥着关键作用,这有助于对案件有更透彻的了解。相比之下,在美国的制度中,举证责任主要由控辩双方在审判期间承担,法官在准备阶段的作用较为有限。美国没有正式的预审阶段,这凸显了两种法律制度之间的根本差异,并强调了刑事案件的调查和准备方法对于查明真相和确保公平审判的重要性。

程序法对于解决影响社会的纠纷和犯罪至关重要,尤其是在涉及犯罪的情况下。这一法律分支规定了在司法系统内处理和解决纠纷和犯罪的规则和方法。程序法的主要目的是确保所有审判以公平有序的方式进行,在保护当事人权利的同时维护公共利益。

程序法的历史可以追溯到古代,并经过了几个世纪的演变。例如,罗马历史学家塔西佗在其著作《日耳曼尼亚》中提到日耳曼民族中存在法院。根据塔西佗的说法,这些法庭负责解决社区内的纠纷。原则或领袖有义务让人民参与司法程序。这种做法见证了古代民众参与司法的一种形式,即领导者并不单独做出判决,而是由社区成员协助或提供建议。这种在社区参与下做出司法判决的争端解决方式,反映了人们早期对司法公平性和代表性重要性的理解。尽管现代司法系统要复杂得多,也正规得多,但参与性和代表性司法的基本理念仍然是一项重要原则。如今,这体现在某些法律制度中的陪审团制度、某些法官的选举制度,或通过民众大会或公开听证会实现的社会参与制度。

在公元 500 年左右的萨利安-法兰克人时代,司法系统由一名法官负责监督整个法律程序。该法官负责从传唤当事人到执行判决的所有阶段。然而,判决本身是由 "rachimbourgs "负责提出的,"rachimbourgs "是从受纠纷影响的社区中选出的七个人组成的小组。然后,他们的判决必须得到 "Thing "的批准,"Thing "是由有权携带武器的自由人组成的集会。这种结构反映了一种参与式司法制度,社区在司法程序中发挥着积极作用。

在阿拉曼尼王国,根据 720 年左右的阿拉曼尼法(lex Alamannorum)的规定,法官必须由公爵任命,但也要经过人民的批准。这一规定强调了社会认可和合法性在法官遴选中的重要性。770 年左右在查理曼统治时期开始的加洛林王朝司法改革对这一制度进行了重大改革。判决权被赋予了作为常任法官的市议员。这一改革削弱了国王在批准判决方面的作用,从而进一步集中了司法权。此时确立的低级司法(causae minores)和高级司法或刑事司法(causae majores)之间的区别尤其值得注意。它为现代民事诉讼和刑事诉讼的区分奠定了基础。初级法院处理通常属于民事性质的轻微案件,而高级法院则处理刑事案件,这些案件被认为更为严重,涉及更严厉的处罚。司法管理方面的这些历史发展反映了从基于社区参与的司法系统向更加集中和有组织的系统的过渡,为当代司法结构铺平了道路。它们还显示了法律的基本原则,如合法性、代表性和不同类型争端之间的区别,是如何随着时间的推移而演变和形成的。

审问

审问式程序起源于教会司法和教会法,之后传入世俗法律体系,特别是在 13 世纪以后。在审问式程序中,法官或治安法官在寻求真相的过程中扮演着积极的角色。在对抗式诉讼中,重点是辩方和控方之间的对抗,而在审问式诉讼中,法官负责调查、询问证人、审查证据并确定案件事实。其主要目的是发现客观真相,而不是完全依赖对方提出的论点和证据。

从历史上看,这种方法深受教会法庭做法的影响,教会法庭试图通过教会当局的彻底调查过程来确立精神和道德上的真理。在教会法中,寻求真相被视为一种道德和精神责任,这也影响了调查的方式。13 世纪,欧洲的世俗司法系统开始采用审问程序。与通常依赖口头证据和双方直接对质的传统司法方法相比,人们希望司法更加系统化和集中化,这刺激了这种采用。在遵循审问式程序的现代制度中,例如在许多欧洲国家,法官在调查事实和进行审判方面仍发挥着核心作用。不过,重要的是要注意到,现代司法制度已经发展到纳入了旨在保护被告权利的程序保障措施,同时允许对事实进行彻底和客观的调查。

有人认为审问式程序将社会利益置于个人利益之上,符合专制政权的需要,这种看法源于审问式程序本身的性质。事实上,在审问式制度中,法官或治安法官在调查、收集证据和确定事实方面发挥着核心和积极的作用,这有时可被视为权力的集中,有可能更广泛地有利于国家或社会的利益。在专制政权中,这种司法制度可用于加强国家控制,强调维护公共秩序和安全,有时会损害个人权利。法官在进行调查和决策时被赋予很大的权力,这可能会导致失衡,从而损害被告获得公平审判和充分辩护的权利。然而,必须强调的是,现代形式的审问式程序在许多民主国家都有实施,这些国家的法律法规旨在保护个人权利。在这些情况下,都有相应的机制来确保被告的权利,如聘请律师的权利、接受公正审判的权利和发表意见的权利等得到尊重。现代司法制度的演变表明,只要有适当的程序和司法保障,审问式程序与尊重个人权利是可以并存的。因此,不仅要考虑审问式程序的结构,还要考虑其实施的法律和制度背景,这一点至关重要。

审问式程序的名称来源于 "inquisitio",这是一种最初的手续,它决定了调查的进行,进而决定了整个审判的进行。在这类程序中,治安法官从调查一开始就发挥着主导作用,调查通常是依职权启动的,即没有私人当事方提出的具体申诉。调查可以由治安法官本人发起,也可以由检察官或警官等公职人员发起。治安法官负责收集和审查证据、询问证人,并在总体上开展调查,以确定案件事实。这种方式与对抗式诉讼有很大不同,对抗式诉讼通常由双方(控方和辩方)进行调查,然后向法官或陪审团提交证据和论据。除进行调查外,在审问式诉讼中,地方法官还在审判期间指导诉讼程序。他或她会向证人提问、审查证据并引导讨论,以确保案件的所有相关方面都得到处理。治安法官的这种积极作用旨在确保对事实的全面了解,并帮助法庭在对证据进行全面分析的基础上做出判决。这种制度起源于教会法和教会司法,在教会法和教会司法中,寻求真相被视为道德和精神上的当务之急。在采用审问式程序的当代司法系统中,尽管治安法官的作用非常重要,但一般都会制定程序保障措施,以保护被告的权利并确保审判的公正性。

在审问式程序中,治安法官拥有相当大的调查权,其行使方式有别于其他法律制度中更为熟悉的对抗式程序。地方法官进行的调查通常具有秘密性、书面性和无对抗性的特点。

审问式调查的秘密性使治安法官能够在没有外部干预的情况下收集证据,这对于防止证据被隐藏或销毁至关重要,尤其是在复杂或敏感的案件中。例如,在大规模腐败案件中,初步调查的保密性可以防止嫌疑人篡改证据或影响证人。在这一系统中,书面文件占主导地位,这意味着陈述、调查报告和证据主要以书面形式记录和存储。这种方法确保了信息记录的准确性和持久性,但可能会限制口头交流中的动态互动,例如在听证或审讯中观察到的互动。此外,调查阶段缺乏对抗性也会让人质疑审判的公正性。在审问式程序中,对方当事人,尤其是被告方,并不总是有机会对治安法官在这一阶段收集的证据提出质疑或直接做出回应。这种情况可能会导致失衡,尤其是当辩方无法获得收集到的所有信息或无法对其进行有效质疑时。因此,必须建立控制机制和程序保障,以平衡纠问式程序中以地方法官为中心的做法。这些机制必须确保尊重被告的权利,包括公平审判权和充分辩护权,同时允许对事实进行彻底客观的调查。目的是确保司法系统在调查的有效性和对基本权利的尊重之间实现平衡。

审问式程序的特点是主要由法官进行调查,它有很大的优缺点,影响其有效性和公正性。这一制度的主要优点之一是降低了有罪方逃脱法律制裁的风险。由于法官在开展调查时采取了积极主动和深入细致的方法,因此更有可能发现相关证据,并查明犯罪责任人。这种方法在复杂或敏感的案件中尤为有效,因为在这些案件中,需要进行彻底的调查才能发现真相。然而,审问式程序的缺点也不容忽视。最令人担忧的风险之一是可能给无辜者定罪。在调查阶段,如果没有强有力的辩护和对抗性辩论的机会,被告可能会发现自己处于不利地位,无法有效质疑对其不利的证据。这可能导致司法不公,无辜者因片面的调查而被定罪。在技术层面上,审问式程序常常因其冗长而受到批评。调查的彻底性和书面性可能会导致刑事案件的解决严重拖延,延长被告和受害者等待案件解决的时间。此外,对书面文件的重视和审判过程中缺乏直接互动会导致司法程序非人性化。这种方法可能会忽视案件中的人性和情感方面,而将重点严格放在书面证据和正式程序上。为了减少这些弊端,许多采用审问式程序的司法系统进行了改革,以加强被告方的权利,加快诉讼程序,并在司法程序中加入更多互动和人性化的元素。这些改革旨在平衡有效寻求真相与尊重被告和受害者基本权利之间的关系。

在以审问式调查为主导的司法系统中,审判结果往往在很大程度上取决于调查结果,这是事实。在治安法官或法官在进行调查和管理证据方面发挥核心作用的情况下,审判听证有时会被视为一种形式,而不是被告质疑对其不利的证据和论点的真正机会。在这种情况下,被告可能会发现自己处于不利地位,因为调查阶段主要由治安法官控制,占据了司法程序的主要部分。如果调查期间积累的证据和结论具有很强的指控性,被告可能会发现在审判时很难扭转这些看法,特别是如果程序不能保证被告有充分的机会进行全面完整的辩护。这种态势引发了对审判公正性的担忧,尤其是在尊重无罪推定权和公平审判权方面。如果庭审流于形式,对抗性司法原则和控辩平衡原则就会受到损害。为了减少这些弊端,许多司法系统都在努力改革审问式程序。这些改革旨在增强辩护方的作用和权利,确保调查过程更加透明,并保证审判听证是一个实质性阶段,被告在此阶段有真正的机会对证据提出质疑并陈述自己对事实的看法。这些改革的目的是根据公平审判的原则,确保调查的有效性与尊重被告权利之间的平衡。

欧洲刑事诉讼程序的历史经历了重大演变,特别是受到启蒙运动的理想以及随之而来的社会和政治变革的影响。在第二个千年期间,特别是自十九世纪以来,欧洲的法律制度经历了一个转变的过程,目的是将纠问式和对抗式程序中最有效和最公平的方面融入其中。

在启蒙运动时期,人们对传统提出质疑,提倡个人权利和理性,对纠问式程序中最僵化、最具压迫性的方面的批评也随之加强。当时的哲学家和改革家,如伏尔泰和贝卡利亚,都强调了这一制度的缺陷,尤其是其缺乏公正性以及经常任意对待被告。他们呼吁进行司法改革,以确保更好地平衡国家权力和个人权利。为了应对这些压力和政治发展,特别是席卷欧洲的革命,许多国家开始改革其司法制度。这些改革旨在采用对抗式诉讼程序的要素,如加强辩护方的作用、无罪推定和审判的对抗性,同时保留纠问式诉讼程序特有的结构化和详尽的调查方法。这些变革的结果是建立了混合司法体系。例如,在法国,司法改革产生了这样一种制度:虽然初步调查由治安法官或检察官进行(审问式特点),但被告的权利受到有力保护,审判本身在公正的法官或陪审团在场的情况下以对抗方式进行(对抗式特点)。这些混合制度力求在效率和公正之间取得平衡,既能进行彻底调查,又能确保被告的权利得到尊重。虽然欧洲各国的这些制度各不相同,但这种融合两种程序最佳做法的趋势已成为欧洲现代司法制度的主要特征。

现代司法制度中的刑事诉讼一般分为两个不同的阶段,这两个阶段融合了纠问式和对抗式两种方法的特点,从而满足了不同的司法目标和原则。初步阶段通常是审问式的。首先是警方调查,执法机构在调查中初步收集证据、询问证人并开展调查,以确定案件事实。这一阶段至关重要,因为它为法律案件奠定了基础。例如,在盗窃案件中,警方将收集物证、询问证人并收集监控录像。这一阶段之后是司法调查,在一些国家由预审法官进行。预审法官进一步开展调查,要求提交专家报告、询问证人并采取措施收集更多证据。这一阶段的特点是秘密、书面和非对抗性,旨在收集所有必要信息,以决定是否对案件进行审判。另一方面,决定性阶段具有对抗性。在这一阶段进行实际审判,然后做出判决。这一阶段是公开的、口头的和对抗性的,允许证据和论点的直接对抗。在审判期间,辩方和控方律师都有机会陈述案情、询问证人并质疑对方的证据。例如,在欺诈案件中,辩方可能会质疑控方提供的财务证据的有效性,或提供相互矛盾的证词。法官或陪审团在听取各方意见后,根据所提供的证据和论据做出判决,从而保障公平审判的权利。这种两阶段的结构反映了在调查的效率和严谨性与公正司法和保护被告权利的原则之间取得平衡的尝试。这表明,司法系统正朝着寻求将两种方法的优点结合起来的方向发展,既保证彻底调查,又尊重基本权利和民主司法程序。

刑事诉讼中出现的混合制度结合了纠问式和对抗式两种方法的优点,是启蒙运动前后开始形成的显著发展。这一时期,人们重新强调理性、人权和公平正义,对社会的许多方面进行了重大改革,包括司法制度。这种混合制度试图借鉴两种传统刑事诉讼方法的优点。一方面,审问式方法因其在收集和彻底审查证据方面的有效性而得到认可,法官或治安法官在调查中发挥着积极作用。另一方面,对抗式方法因其对抗性和透明性而备受推崇,可确保被告有公平公正的机会针对指控为自己辩护。因此,在混合制度的决定性阶段,我们可以发现两种方法的要素。例如,虽然法官可以在评估证据方面发挥积极作用(审问式特征),但被告和辩护方也有机会质疑这些证据并提出自己的论点(对抗式特征)。这一阶段通常是公开的,在听证会上公开出示和审查证据,允许辩方和控方直接对质和辩论。采用这种混合制度是为了在调查的效率和严谨性与尊重被告权利和公平审判原则之间取得平衡。这一发展反映了法律和司法思想的重大演变,它受到启蒙运动理想的影响,旨在促进更公平、更均衡的司法。

刑事诉讼的原则

合法性原则在刑法中发挥着至关重要的核心作用,既规范实体规则,也规范程序。这一原则是许多法律制度的基本原则,它确保刑事行动和制裁以法律为依据。

在实体规则方面,合法性原则规定,任何人不得因其实施时法律未界定为犯罪的行为而被认定有罪或受到惩罚。这一原则对于确保法律适用的公正性和可预见性至关重要。例如,如果某人实施的行为在当时有效的法律下不被视为犯罪,那么即使后来法律发生变化,也不能因该行为对其提起刑事诉讼。这体现了 "法无明文规定不为罪,法无明文规定不处罚 "的格言,即没有先行存在的法律,就不会有犯罪或处罚。合法性原则也适用于刑事诉讼。这意味着司法程序的所有阶段,从调查到定罪,都必须按照法律规定的程序进行。这确保被告的权利在整个司法程序中得到尊重。例如,获得公正审判的权利、辩护的权利和在合理时间内接受审判的权利,这些都是刑事诉讼程序中必须由法律明确规定和保障的方面。

尊重实体和程序规则的合法性原则是防止司法专断的保障,也是保护人权的支柱。它确保个人不会受到追溯性的刑事制裁或没有适当法律依据的司法程序。这一原则加强了公众对刑事司法系统的信心,确保个人依法受到公平对待,从而促进了司法程序的完整性和合法性。

合法性原则

就行政行为而言,合法性原则是许多法律制度中法治的重要基础。这一原则要求公共行政只能在法律规定的框架内行事。它有两个基本方面:法律至上和行政行为必须有法律依据。

法律至上或至高无上原则规定,行政部门必须遵守所有管辖它的法律规定。这意味着行政部门的所有活动和决定都受现行法律的约束,必须按照这些法律行事。这一原则确保政府的行动不是任意的,而是受法律框架的指导和限制。在实践中,这意味着行政决定,如发放许可证或实施制裁,必须以明确制定的法律为基础,不得减损立法规范。此外,法律依据原则要求行政部门的任何行动都必须有法律依据。换句话说,只有在法律明确授权的情况下,当局才能采取行动。这一原则限制了行政行为的范围,确保行政部门采取的每一项措施都有坚实的法律依据。例如,如果政府机构希望实施新的法规,就必须确保这些法规得到现行法律的授权,或者是根据新的法律制定的。

合法性原则的这两个方面--法律至上和法律依据要求--共同确保行政部门以透明、可预测和公平的方式行事。它们有助于保护公民免受滥用权力之害,并增强人们对行政和政府机构的信心。简而言之,合法性原则对于确保行政部门在法律赋予的权力范围内运作,从而维护民主原则和法治至关重要。

瑞士刑法典》第 1 条规定了一项刑法基本原则,即通常所说的刑事合法性原则: "没有法律就没有惩罚"。该原则规定,只能对法律明确规定和应受处罚的行为实施处罚或措施。这一规定确保个人只能因实施时被明确界定为犯罪的行为而受到起诉和惩罚。这在一定程度上确保了刑法的可预测性,并保护公民免受司法专断之害。

法无明文规定不处罚 "原则是法律确定性和尊重人权的基本要素。它可以防止刑法的追溯适用,确保刑事制裁以清晰、准确和公开的法律为基础。例如,如果颁布了新的刑法,它就不适用于在其生效之前实施的行为。同样,如果现行法律被废除,则不能再将其作为起诉或定罪的依据。瑞士刑法典》第 1 条体现了一项基本法律原则,即只有法律明确禁止的行为才能受到刑事制裁,从而保护个人权利。这一原则是法治的基石,有助于提高公众对刑事司法系统的信心。

在刑法中,法律作为界定罪行和适用刑罚的来源,发挥着首要和排他性的作用。这一原则是许多法律制度的核心,它确保只有议会或相关立法机构制定的法律才能明确规定哪些行为构成犯罪并确定相应的处罚。这种做法对司法系统和整个社会有几个重要影响。首先,它确保了刑法的明确性和透明度。例如,如果立法明确规定盗窃及其变种属于刑事犯罪,并确定了监禁或罚款等处罚范围,那么公民就能准确、方便地了解哪些行为是非法的,以及这些行为的潜在后果。这种方法还能保护个人免受专横和滥用权力之害。它防止司法或行政当局追溯性地制定或适用法律,或对实施时不被视为违法的行为进行处罚。这意味着司法判决必须严格以先前存在的法律为依据。刑法不溯及既往是这一方法的一个重要方面。它确保只能根据被指控行为发生时有效的法律对个人进行审判和处罚,从而避免不可预测和不公正的处罚。

刑法中的合法性原则是许多法律体系的基石,它以三条基本格言为基础,这些格言共同保证了法律的公平和可预测的适用。这些格言深深植根于法理之中,构成了防止任意性的堡垒,并确保国家在刑事事项上行使权力时尊重个人权利。

第一条格言是 "法无明文规定不为罪"(nullum crimen sine lege),它规定,除非法律在行为发生前明确将其定为犯罪,否则不能将该行为视为犯罪。这一规则对刑法的可预测性至关重要,它使公民能够了解其行为的合法性界限。例如,如果立法者决定将一种新的在线行为定为犯罪,那么该行为只有在新法律颁布之后才会成为犯罪,而在该法律颁布之前的类似行为则不能被起诉。第二条格言是 "法无明文不为罪",确保除法律明文规定的处罚外,不得实施其他处罚。这可确保个人了解犯罪行为的潜在后果,并防止法官施加现行法律未授权的处罚。这一规则保护个人免受意外制裁或司法发明的新刑罚。最后,"法无明文规定不为罪"(nulla poena sine crimine)的格言强调,只有在法律认可某行为为犯罪的情况下,才能实施处罚。这一规则确认,刑事定罪需要证明法律规定的罪行。例如,只有当一个人的行为符合欺诈的法律定义,并且其罪行得到确凿无疑的证明时,才能判定其犯有欺诈罪。这些原则在保护公民权利、确保公平透明地适用刑事司法方面发挥着至关重要的作用。通过要求法律明确界定犯罪和刑罚,这些规则增强了公众对刑事司法系统的信心,同时确保司法权不会以滥用或任意的方式行使。

"法无明文不为罪"、"法无明文者不罚 "和 "法无明文者不为罪 "的格言所表达的合法性原则的后果也延伸到刑事诉讼规则中,强调了合法性在司法中的至关重要性。根据这一原则,不仅罪行和刑罚必须由法律规定,而且程序规则本身也必须植根于法律并符合基本权利。这一要求确保了从调查到判决和执行刑罚的整个司法程序都遵循法律规定的清晰明确的规则。这包括被告在调查和审判期间的权利、如何收集和提交证据、审讯程序以及可以进行或推迟审判的条件等方面。出于多种原因,制定支持刑事诉讼的法律至关重要。首先,它确保司法程序中涉及的个人权利,尤其是被告的权利得到尊重。例如,法律通常会规定获得法律援助的权利、获得公平审判的权利以及在合理时间内接受审判的权利。其次,法律规定的程序可以防止司法系统中的任意性和滥用权力。法官和检察官有义务遵守预先确定的规则,这就限制了主观或不公正裁决的风险。最后,遵守以法律为基础的程序规则可加强司法系统的合法性和透明度。这样,公民就能保证法律程序是按照民主原则公平进行的。

合法性原则植根于《宪法》的基础,在法律和民主秩序的结构和运作中发挥着至关重要的作用。该原则以若干关键概念为基础,共同确保公平和透明的治理。该原则的核心是法律至上,规定所有行动,无论是个人、公司还是国家代理人,都必须遵守既定法律。这种至高无上的地位确保了国家权力在法律框架规定的范围内行使,从而保护公民免受任意行为之害。例如,如果政府希望出台新的环境法规,那么这些法规必须根据现行法律制定,不能在没有法律依据的情况下单方面强加于人。同时,法律依据要求规定所有国家行为都必须有法律依据。这意味着,政府的决定,无论是涉及公共政策还是个人干预,都必须有现行法律作为依据。这一法律依据要求对于保持公共行政的问责制和透明度至关重要。例如,如果市政府决定增加地方税收,那么这一决定必须有授权增加税收的法律作为依据。最后,基于诚信原则的程序规则的应用是公正和公平的额外保障。这要求参与司法或行政程序的各方正直诚信。这一原则可防止滥用程序谋取不正当利益或妨碍司法公正。例如,在审判中,这意味着双方律师必须诚实地提出论点和证据,不得试图误导法庭或操纵诉讼程序,使其对自己有利。合法性原则的这些方面共同创造了一种环境,在这种环境中,国家权力得到负责任的行使,公民的权利和自由得到深切的尊重。它们加强了法治和公众对机构的信心,确保法律得到公平、统一和透明的实施。

在司法系统中,程序本身不得成为目的这一观点至关重要。当程序取代司法本身时,法律制度就有可能忽视其首要目标:确保公平公正的司法。过分强调程序的危险在于,它可能导致形式重于实质的情况,即严格遵守形式和程序规则可能会掩盖对真相和正义的追求。在这种情况下,一些微小的程序细节可能会使关键证据失效或妨碍审判的公正进行,从而导致司法不公或不合理地拖延结案。为防止程序取代司法,法官、检察官和律师等负责适用程序的人员必须坚决遵守诚信原则。这意味着他们必须将程序规则作为促进发现真相和司法公正的工具,而不是作为获得技术优势或阻碍司法程序的手段。因此,司法官员必须确保程序服务于司法利益,并以保护当事人权利的方式适用,同时努力实现案件的公平和及时解决。这包括确保程序不被滥用或过度使用,以免破坏审判的公正性或不适当地拖延司法。

诚信原则

The principle of good faith, particularly in Swiss law, is an essential concept that guides interactions and behaviour within the legal framework. This principle applies both to the State and to private individuals and is enshrined in the Swiss Constitution (see art. 5 para. 3 of the Constitution) and in the Swiss Civil Code (CC) (see art. 2 para. 1 CC).

Good faith in the objective sense, as stipulated by law, imposes a duty to behave honestly and fairly in all legal relationships. This means that in transactions, negotiations, the performance of contracts, legal proceedings and all other legal interactions, the parties are required to observe standards of honesty, loyalty and transparency. For example, in the context of a contract, parties should not only strive to respect the letter of the agreement, but also the spirit of cooperation and fairness that underlies the agreement. In contrast, good faith in the subjective sense, referred to in art. 3 CC, concerns a person's state of knowledge or ignorance of a legal defect affecting a specific state of affairs. This refers to the situation where a person acts without being aware that he or she is violating a right or committing a legally reprehensible act. For example, a person may purchase property in the belief that it is legally available for sale, without knowing that it is in fact stolen or encumbered by a right of ownership held by a third party.

The distinction between objective and subjective good faith is important in legal practice, as it influences the assessment of the parties' behaviour and intentions in various legal contexts. While objective good faith focuses on compliance with standards of behaviour in legal interactions, subjective good faith deals with a person's state of knowledge or ignorance in relation to a given legal situation. Together, these two aspects of good faith contribute to fairness and justice in the legal framework, fostering transparent and equitable interactions between the parties.

Article 5 of the Swiss Constitution establishes fundamental principles that guide the activity of the State, ensuring that it is conducted in accordance with the law, the public interest and high ethical standards. These principles reflect the values of Swiss democracy and the rule of law, and they play a crucial role in maintaining fair and accountable governance. The first principle emphasises that the law is both the basis and the limit of state activity. This means that all actions taken by the state must be based on existing laws and cannot exceed the limits set by those laws. For example, if the Swiss government wishes to introduce a new tax policy, that policy must be based on existing or new legislation, and it cannot violate other existing laws. The second principle addresses the notion that state actions must serve the public interest and be proportionate to the intended purpose. This means that measures taken by the authorities must be justified by a common good and must not be excessive in relation to their objectives. For example, when implementing public security measures, the State must ensure that these measures are no more restrictive than necessary to achieve the security objective. The third principle of Article 5 concerns good faith, requiring State bodies and individuals to act honestly, fairly and transparently in their legal relations. This principle is essential for maintaining confidence in public institutions and ensuring fair interactions between the State and citizens. In the context of public administration, this means that civil servants must make decisions and act transparently and ethically, without favouritism or corruption. Finally, respect for international law is a crucial commitment for Switzerland, reflecting its adherence to international norms and agreements. The Confederation and the cantons are obliged to respect international treaties and the principles of international law, which strengthens Switzerland's position and credibility on the world stage. For example, in its foreign policy, Switzerland must respect international conventions on human rights and the rules of international trade. Article 5 of the Swiss Constitution provides a clear framework for state action, rooted in the principles of legality, public interest, good faith and respect for international law. These principles ensure that the State acts responsibly and ethically, protecting the rights and freedoms of its citizens and honouring its international commitments.

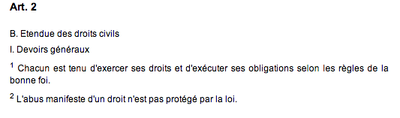

Article 2 of the Swiss Civil Code is a fundamental piece of legislation that defines the way in which rights and obligations must be exercised and enforced within the Swiss legal framework. According to this article, rights must be exercised and obligations fulfilled in accordance with the principles of good faith, which implies honest, fair and equitable behaviour on the part of all individuals. This principle of good faith plays a crucial role in maintaining a fair and equitable legal system. For example, when a person enters into a contract, he or she is obliged not only to respect the literal terms of the agreement, but also to behave in a way that is consistent with the spirit of fairness and mutual cooperation. This means that a party must not intentionally conceal important information or mislead the other party. In addition, Article 2 also states that manifest abuse of a right is not protected by law. This provision serves to prevent situations where legal rights could be exercised in an abusive or unfair manner. The intention of this clause is to prevent individuals from using their rights in a way that contravenes the original intention of the law or causes unjustified harm to others. For example, in the case of a property owner using his or her property rights to deliberately harm neighbours without valid justification, this could be considered an abuse of rights and therefore not protected by law. Article 2 of the Swiss Civil Code emphasises the importance of exercising rights and fulfilling obligations responsibly and fairly, adhering to the principles of good faith. It aims to encourage fair and reasonable use of legal rights, and to prevent abuses that might occur in legal relationships. This framework contributes significantly to the creation of a society where the law is used not only as an instrument to protect rights, but also as a means to promote justice and fairness.

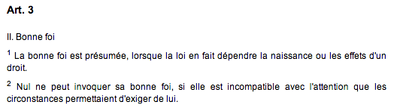

Article 3 of the Swiss Civil Code deals in depth with the concept of good faith, an essential element in legal relationships. According to this article, good faith is not only a presumed principle in legal interactions, but its scope is also limited in certain circumstances to prevent abuse. The first aspect of this article states that in legal situations where the law bases the creation or effects of a right on good faith, good faith is automatically presumed. This means that in everyday transactions, contracts and other legal relationships, individuals are presumed to act with honesty and integrity, unless proven otherwise. For example, when a person signs a contract, it is presumed that he or she understands and accepts the terms of the contract in good faith. This presumption simplifies transactions by establishing a basis of mutual trust, which is essential for the smooth functioning of legal and commercial relationships. However, good faith cannot be invoked to justify ignorance or non-compliance with obligations that should be obvious in a given context. The second aspect of Article 3 makes it clear that good faith is no excuse for ignoring standards of behaviour that circumstances make reasonable. If, for example, a person buys an object at a derisory price that suggests that the object might be stolen or acquired illicitly, that person cannot claim good faith for ignoring legitimate suspicions about the origin of the object. In short, Article 3 of the Swiss Civil Code balances the presumption of good faith with the need for responsibility and due diligence. This legal framework ensures that good faith remains a vital principle in facilitating honest and fair dealings, while preventing its misuse to circumvent obvious legal or moral obligations. This approach helps to maintain trust and integrity in the legal system, while protecting parties from negligent or dishonest behaviour.

Legislation, particularly in the area of criminal law, must strike a delicate balance between the interests of individuals and those of society. This balance is essential to ensure that laws and judicial procedures are fair, equitable and effective. On the one hand, procedural provisions must not be excessively harsh on defendants. Procedures that are too rigid or punitive may infringe the fundamental rights of the accused, in particular the right to a fair trial and an adequate defence. For example, if the rules of procedure are so strict that they prevent a lawyer from effectively presenting a defence or challenging the evidence, this could lead to injustice. On the other hand, procedures should not be so excessively formalistic as to undermine the efficiency and speed of the judicial system. Procedures that are too complicated or cluttered with formalities can delay justice and make the judicial process unnecessarily difficult and time-consuming for all concerned. A crucial aspect of this balance is to ensure that the defence can express itself freely. Criminal procedure must provide a framework in which the rights of the accused to defend themselves are fully respected and protected. This means giving the accused and their lawyer the opportunity to challenge evidence, present witnesses and participate fully in the trial. However, this must not compromise the State's ability to carry out its task of maintaining law and order and punishing crime. The aim is to achieve a balance where criminal justice is delivered effectively, while protecting individual rights and freedoms. Criminal laws and procedures must harmonise the interests of individuals with the imperatives of society. This balance is essential to maintain a criminal justice system that is fair, effective and respectful of the fundamental rights of the individual. Well-designed legislation and fair court procedures are crucial to ensuring public confidence in the legal system and to promoting an orderly and just society.

Criminal procedure, a crucial aspect of the justice system, is guided by fundamental principles that impose essential duties on criminal authorities. These principles ensure that the judicial process is conducted fairly and equitably, while respecting the fundamental rights of individuals. One of these fundamental principles is the principle of legality, which requires that all the actions of the criminal authorities be based on clearly established laws. For example, criminal investigations must be conducted in accordance with defined legal procedures, and the sentences handed down must be those laid down by law for the offences concerned. Another pillar is the right to a fair trial, which guarantees that anyone accused of a crime has the benefit of an adequate defence, the right to be heard and the right to an impartial judgement. This principle is fundamental to preventing miscarriages of justice and ensuring fairness. Accused persons must therefore have access to a lawyer and be informed of their rights from the outset of criminal proceedings. The presumption of innocence is also a central principle of criminal law. Anyone accused of a crime is considered innocent until proven guilty. This means that the burden of proof lies with the prosecution, not the accused. The criminal authorities must therefore treat the accused fairly and impartially during the investigation and trial. Protection against inhuman or degrading treatment is another essential requirement. Defendants must not be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment at any time during their detention or trial. This principle is crucial to maintaining human dignity and the integrity of the judicial system. Respect for privacy is also important. Criminal authorities must ensure that the privacy rights of individuals are respected during investigations, except where justified and proportionate. The principle of proportionality is also vital. The measures taken, whether in terms of detention, questioning or sentencing, must be proportionate to the objective sought and the seriousness of the offence. For example, the use of preventive detention must be justified and proportionate to the nature of the alleged offence. Finally, the right of appeal is an essential aspect, allowing defendants to challenge decisions taken at first instance. This possibility of appeal is an additional guarantee against miscarriages of justice and allows decisions to be reviewed by higher authorities. Together, these principles contribute to the creation of a fair and balanced criminal justice system, in which the rights of individuals are protected while the law is effectively enforced. They strengthen public confidence in the integrity of the justice system and respect for the rule of law.

The fundamental principles governing criminal procedure have their origins not only in national legislation, such as the Swiss Federal Constitution, but also in international treaties. These multiple sources ensure overall consistency and conformity of judicial practices with international human rights standards. The Swiss Federal Constitution provides a frame of reference for fundamental rights and freedoms, as well as for the principles of justice. It sets out clear guidelines on how legal proceedings should be conducted, emphasising aspects such as the right to a fair trial, the presumption of innocence and protection against inhuman or degrading treatment. These principles are essential to ensure that the actions of the state remain within the law and respect the rights of individuals. At the same time, international treaties play a crucial role in setting standards for human rights and judicial procedures. The European Convention on Human Rights, for example, is a major instrument that influences the legal systems of its member states, including Switzerland. It stipulates rights such as the right to life, the prohibition of torture, the right to a fair trial, and the right to respect for private and family life. Similarly, UN human rights covenants, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, set international standards for a range of fundamental rights, including those relating to criminal proceedings. These documents set out commitments for signatory states to respect and protect human rights and to ensure that their judicial systems comply with these commitments. The combination of these national and international sources ensures that the principles of criminal procedure are not only anchored in national law, but are also aligned with international standards. This contributes to the protection of individual rights and the integrity of the judicial system, while promoting respect for and adherence to international standards of justice and human rights.

The stages of criminal proceedings

1 January 2011 marked a significant change in the Swiss legal system with the entry into force of new procedural codes, in particular the Swiss Code of Criminal Procedure (SCCP). This reform represented an important step in the unification and modernisation of judicial procedures in Switzerland. Prior to this reform, Switzerland had a highly decentralised judicial system, with each canton having its own code of criminal procedure. This diversity of systems led to a degree of inconsistency and complexity, making legal proceedings potentially complicated and uneven across the cantons.

The introduction of the Swiss Code of Criminal Procedure unified procedural practices across the country, creating a more coherent and efficient system. The Code established uniform rules and standards for the conduct of criminal investigations, prosecutions and trials throughout Switzerland. It also introduced improvements in terms of the rights of the defence, appeal procedures and evidence management. The adoption of this federal code has strengthened the rule of law in Switzerland, by ensuring that all citizens are subject to the same judicial procedures, regardless of the canton in which they live or where the offence was committed. This standardisation has also made it easier for legal professionals, litigants and citizens to understand and apply the law.

The amendment of the Swiss Constitution in March 2000, approved by the people and the cantons, marked a crucial stage in the transfer of criminal jurisdiction from the cantonal to the federal level. This constitutional revision reflected a democratic desire to centralise and standardise the criminal justice system in Switzerland. This constitutional change was a response to the need to harmonise judicial procedures across the country. Prior to this change, Switzerland had a highly decentralised judicial system, with codes of criminal procedure varying considerably from one canton to another. This diversity led to inconsistencies and complications, sometimes making the judicial system difficult to navigate for both legal professionals and litigants.

The adoption of the constitutional amendment by the people and the cantons therefore laid the legal foundations for the Confederation to take over responsibility for criminal procedure. As a result, the federal government exercised this new power by drafting and implementing the Swiss Code of Criminal Procedure, as well as a Code of Civil Procedure. The effect of this initiative was to unify and standardise legal procedures throughout the country, enhancing the fairness, consistency and efficiency of the justice system. This reform therefore represented a major step forward in Swiss judicial history, illustrating a democratic approach to judicial reform and a commitment to improving and modernising the criminal justice system. The centralisation of criminal jurisdiction at federal level has helped to ensure a more uniform application of the law across Switzerland, to the benefit of Swiss society as a whole.

In civil proceedings, which deal with non-criminal disputes such as commercial disputes, family matters or property issues, the judicial process generally takes place in two distinct phases, each with specific objectives and characteristics. The first phase, known as the preliminary phase, is devoted to preparing and organising the dispute. During this period, the parties involved, often assisted by their lawyers, engage in the collection and exchange of evidence, the clarification of claims and defences, and the preparation of arguments for the trial. For example, in a dispute concerning a breach of contract, this phase may include exchanging contractual documents, gathering witness testimony, or consulting experts to assess damages. This stage is also an opportunity to explore out-of-court settlement options, which may enable the dispute to be resolved without going to full trial. If the dispute is not resolved during this preliminary phase, the case moves on to the decisive phase. This second phase is marked by hearings before the court, where evidence is presented and the arguments of both parties are heard. The judge, or sometimes a jury, examines the evidence, applies the relevant laws and renders a decision on the dispute. In our breach of contract example, this phase would involve pleadings before the court where each party would present their arguments and evidence, and the judge would then make a ruling on whether there has been a breach and what remedies may be available. By combining these two phases, civil procedure aims to ensure that disputes are managed fairly and efficiently. The preliminary phase allows for thorough preparation and the possibility of resolving disputes in a less formal manner, while the decisive phase provides a platform for impartial and detailed judicial assessment. This structure ensures that civil disputes are handled in a balanced way, taking into account both the need for careful preparation and the importance of a fair and transparent judicial resolution.

PHASE 1: Preliminary

The preliminary phase of criminal proceedings, an essential stage in the judicial process, consists of two main parts: the investigation, often carried out by the police, and the inquiry, usually conducted by an examining magistrate or judge.

The investigation, which is the first stage of this phase, involves a thorough enquiry to gather evidence and information about the alleged crime. During this period, the police are actively involved in gathering evidence, interviewing witnesses and examining all available data that may shed light on the circumstances of the crime. For example, in the case of a burglary, the police might collect fingerprints from the scene, interview neighbours or potential witnesses, and examine surveillance videos to identify suspects. Once this first stage of investigation is complete, the case moves on to the investigation stage. This second phase is crucial for building the prosecution's case and deciding whether the case should go to trial. The investigating judge, who is responsible for this phase, carries out a meticulous examination of the evidence gathered, may order additional analyses, summon and question witnesses or suspects, and assess the relevance and solidity of the evidence. The aim is to determine whether the evidence gathered supports the charges sufficiently to justify a trial. The investigation plays a decisive role in ensuring that the rights of the defence are respected and that the case against the accused is fair and complete. These two stages of the preliminary phase of criminal proceedings are therefore fundamental to the proper administration of justice. They ensure that criminal cases are dealt with rigorously and fairly, laying a solid foundation for subsequent prosecutions and judgements. This methodical approach is essential to ensure that judicial decisions are taken on the basis of solid evidence and with respect for the fundamental rights of the individuals involved.

In the Swiss justice system, the cantonal public prosecutor's office plays a crucial role in the conduct of criminal investigations. This institution is responsible for directing investigations, conducting inquiries and drafting the indictment to be presented in court. As the prosecuting authority, the public prosecutor is responsible for investigating criminal offences. This involves supervising the activities of the police and other investigative agencies, gathering the necessary evidence, and determining whether there is sufficient evidence to justify prosecuting a case. In this phase, the public prosecutor ensures that the investigation is conducted rigorously and in accordance with legal standards, while respecting the rights of those involved.

Once the investigation is complete, the public prosecutor moves on to the investigation phase. During this phase, it assesses all the evidence gathered, interviews witnesses and suspects, and decides whether the evidence is sufficient to justify an indictment. If the prosecution considers that the evidence is sufficient, it then draws up the indictment, which formalises the charges against the individual or individuals concerned, and submits it to the court for trial. The centralisation of these functions - indictment, investigation and prosecution - within the Public Prosecutor's Office makes criminal prosecution highly efficient. It allows for coordination and consistency in the management of criminal cases, while ensuring that prosecutions are conducted objectively and fairly. The Public Prosecutor's Office thus plays an essential role in maintaining public order and ensuring justice, by ensuring that offences are properly investigated and that those responsible are held accountable for their actions in accordance with legal principles and human rights.

The Public Prosecutor's Office, in the context of the judicial system, plays a fundamental role as the body representing the law and the interests of the State before the courts. It is made up of magistrates whose main task is to ensure that the law is applied and that criminal offences are prosecuted. Members of the public prosecutor's office, often referred to as public prosecutors or public defenders, are responsible for defending the public interest by investigating criminal offences and deciding whether the evidence gathered warrants prosecution. Their role is not limited to seeking the conviction of suspects; they must also ensure that justice is done fairly and in accordance with the principles of law. During trials, public prosecutors present evidence and arguments to the court in support of the prosecution. They are obliged to present the facts objectively, taking into account not only the evidence against the prosecution but also the evidence against the defendant. In addition, they must ensure that the rights of the accused are respected throughout the judicial process. The public prosecutor also plays a crucial role in supervising police investigations. It ensures that investigations are conducted legally and ethically, and that evidence is collected in a way that is admissible in court. The public prosecutor is an essential pillar of the criminal justice system. Its work is designed to ensure that the law is applied fairly and equitably, that offences are prosecuted effectively and that the public interest is safeguarded while respecting fundamental rights and freedoms.

The investigation is a critical phase of the criminal trial, in which the investigating magistrate plays a central role. During this stage, the magistrate carries out a series of in-depth investigations to clarify various aspects of the criminal case in progress. The main aim of the investigation is to identify the perpetrator of the offence. The investigating magistrate conducts enquiries to gather evidence, question witnesses and, if necessary, call in experts. The aim of this investigation is to determine not only who committed the act, but also how and why. As well as identifying the perpetrator, the investigation aims to gain an in-depth understanding of the personality of the accused. This can include examining their background, motivations and any factors that may have influenced their behaviour. This understanding can be crucial in determining the nature of the sentence or the measures to be taken.

The investigating magistrate also looks at the circumstances surrounding the offence. This involves determining the context in which the act was committed, including the events leading up to the offence and the conditions that may have contributed to it. Finally, the aim of the investigation is to establish the consequences of the offence. The magistrate assesses the impact of the act on the victims, society and even on the accused himself. This assessment is important in deciding what to do next, in particular whether the case should go to trial and what charges should be brought. The decision as to what action should be taken against the accused is taken at the end of this investigation phase. After carefully examining all the evidence and information, the magistrate decides whether the case should go to trial and, if so, what charges should be brought against the accused. The investigation is therefore a decisive phase of the criminal trial, as it establishes the basis on which criminal justice will be dispensed. It requires a balance between a meticulous search for the truth and respect for the rights of the accused, thus guaranteeing a fair and equitable trial.

When a denunciation is received, the competent authorities, usually the police, begin an investigation to determine the veracity of the allegations and gather initial evidence. This investigation is the first step in responding to a possible criminal offence and plays a crucial role in deciding whether or not to initiate legal proceedings. After receiving a tip, investigators begin by gathering information, which may include interviewing witnesses, examining physical evidence and sometimes analysing technical or digital data. The aim is to gather enough evidence to establish whether a criminal act has probably been committed. Once this initial investigation phase has been completed, the case is generally referred to the public prosecutor. At this stage, the public prosecutor, who is responsible for conducting criminal proceedings, assesses the evidence gathered to decide whether to open a formal investigation. This decision is based on whether there is sufficient suspicion that an offence has been committed. If the evidence gathered during the investigation is sufficiently convincing to suggest that a criminal offence has been committed, the public prosecutor will open an investigation. The opening of an investigation means that the case is sufficiently serious and well-founded to warrant an in-depth enquiry. During this phase, the public prosecutor can carry out further investigations, question suspects, order additional expert reports and gather all the evidence necessary to establish the extent and nature of the alleged offence. This procedure shows how the judicial system balances the need to investigate potential offences with the need to ensure that such investigations are justified. It ensures that judicial resources are used appropriately and that the rights of those involved, including suspects, are respected throughout the process.

The opening of an investigation is a decisive stage in the criminal justice process. This phase begins when the public prosecutor, after examining the evidence gathered during the initial investigation, decides that there is sufficient evidence to charge the accused. The decision to prosecute and charge an individual is taken when the prosecution is satisfied that there is credible evidence that an offence has been committed and that the accused is probably responsible. This stage marks the transition from a preliminary enquiry to a formal investigation, where the public prosecutor focuses on preparing the case for a possible trial. When the investigation begins, the public prosecutor carries out a series of actions to consolidate the case against the defendant. This may include gathering additional evidence, questioning witnesses, carrying out forensic examinations and further examining the evidence already in its possession. The accused is also informed of his status and the charges against him. They have the right to know the nature of the charges and to prepare their defence, often with the assistance of a lawyer. This phase is crucial, as it must be conducted in accordance with the principles of fair justice and the rights of the defence. The public prosecutor, as the prosecuting authority, must ensure that the investigation is exhaustive and impartial, making sure that all the evidence, both incriminating and exculpatory, is taken into account. In short, the opening of the investigation by the public prosecutor is a key moment in the criminal process, marking the start of a formal investigation and the preparation of a solid case for a possible trial, while guaranteeing respect for the rights of the accused and the requirements of a fair trial.

PHASE 2: Decisive

The transmission of the indictment by the public prosecutor to the court marks the start of the decisive phase of the criminal judicial process. This phase is crucial, as it leads to the judicial examination of the case and, eventually, to a judgement. When the indictment is presented, the role of the public prosecutor changes. During the investigation phase, it conducted the investigation and prepared the prosecution case, but now it becomes the public prosecutor in court. As such, the public prosecutor is responsible for presenting the case against the accused, setting out the evidence and arguments in support of the charges. Although the public prosecutor is an essential part of the proceedings, it is important to note that he or she must present the case objectively, ensuring that all relevant evidence, including that which could exonerate the defendant, is taken into account.

In this decisive phase, the presiding judge plays a central role. He or she is responsible for directing the proceedings, ensuring that the trial is conducted in an orderly and fair manner and in accordance with the principles of justice. The presiding judge must ensure that the rights of all parties, including those of the defendant, are respected. He supervises the presentation of evidence, witness statements and the arguments of both parties, and ensures that the trial is conducted in accordance with the rules of procedure and legal rights. The role of the presiding judge is therefore essential in guaranteeing the impartiality and effectiveness of the trial. He or she must ensure that the trial takes place in a fair environment, where the facts can be clearly established and a decision can be made on the basis of the evidence and the applicable laws. The decisive phase is a key moment in the judicial process, when the charges against the defendant are formally examined and the court, under the leadership of its president, plays a crucial role in determining guilt or innocence.

The first stage of the criminal judicial process, which consists of the examination of the charge, is fundamental in determining what happens next. This stage is marked by specific actions and follows a rigorous process to ensure justice and fairness. First of all, the public prosecutor transmits the indictment to the court. This indictment is the result of the investigation carried out by the public prosecutor and contains details of the charges brought against the accused, as well as the supporting evidence. Transmission of the indictment marks the transition from the investigation phase to the trial phase. Once the indictment has been received, the court, often under the direction of the judge or presiding judge, carries out a thorough check to ensure that the charge has been properly drawn up. This check includes examining whether the indictment complies with legal procedures and assessing the quality of the evidence presented. The court then assesses whether the conduct described in the indictment is punishable by law and whether there is sufficient suspicion to support the charge. If these conditions are met, the judge then initiates the trial. This decision is crucial as it determines whether the case progresses to a full trial. The presiding judge plays a key role in preparing for the trial. He is responsible for preparing the proceedings, making the files available to the parties involved, setting the trial date and summoning the individuals involved in the case, including witnesses, experts and parties to the proceedings. This first stage of the criminal justice process reflects the inquisitorial approach in which the court plays an active role in examining the evidence and determining the relevance of the charge. It ensures that charges against an accused person are subject to thorough judicial scrutiny before the case progresses to a full trial, thereby ensuring the fairness and legality of the judicial process.

The second stage of the criminal justice process, the hearing in court, marks the transition to an adversarial procedure. This phase is characterised by its public and oral nature, and highlights the crucial role of the judge, not only as the central actor in this phase, but also as the impartial arbiter of the trial. During this phase, the proceedings take on a more interactive and open form. Hearings are held in public, which guarantees the transparency of the judicial process and enables the evidence and arguments presented by both parties to be examined in public. The oral nature of the proceedings is a key element, as it allows the evidence, testimony and arguments of both the prosecution and the defence to be presented directly and vividly. This enables the judge, and possibly the jury, to better assess the credibility and relevance of the information presented. The judge's role in this phase is both active and arbitral. Although he directs the proceedings, asking questions and clarifying points of law where necessary, he must also maintain a position of impartiality, ensuring that the trial is conducted fairly and equitably for all parties. The judge ensures that the proceedings are balanced, making sure that both the prosecution and the defence have equal opportunities to present their cases, question witnesses and respond to each other's evidence and arguments. This phase of the court proceedings is therefore essential to ensure that the rights of the accused are respected and that the truth can be established fairly. It allows for a thorough and transparent assessment of the facts of the case, ensuring that the final decision is based on a full and balanced consideration of all the relevant evidence and information.

In a criminal trial, the proceedings before the court are conducted according to a rigorously structured procedure, ensuring a full and fair assessment of the case. The procedure begins with the presentation of the indictment by the public prosecutor. This sets out the charges against the defendant and summarises the evidence in support of those charges, laying the foundations for further discussion and analysis. After this introduction, the court embarks on the evidentiary phase, where various pieces of evidence are examined in detail. This stage is essential to establish the facts of the case. Testimony plays an important role in this phase. The court hears from witnesses, experts and the defendant himself. Each witness gives a unique perspective on events and helps to build a complete picture of the case. For example, in a robbery case, witnesses may provide details of the circumstances of the crime or the behaviour of the defendant, while experts may provide technical insights, such as the analysis of fingerprints or video recordings. In addition to testimony, the court also examines material and documentary evidence. This can include anything from contractual documents to photographs or audiovisual recordings, depending on the nature of the case. Once all the evidence has been presented and examined, the pleadings begin. The prosecution, followed by the plaintiff, presents its arguments, interpreting the facts and evidence in the case file. These pleadings are crucial, as they give each side the opportunity to defend its perspective and respond to the points raised by the other side. If necessary, a second round of pleadings may be organised to allow the initial arguments to be rebutted. At the conclusion of the proceedings, the defendant has the right to speak last. This principle ensures that the defendant has a final opportunity to express himself, clarify points or present his final arguments. This stage is fundamental to respect for the right to a defence and the guarantee of a fair trial. The structure of these debates is carefully designed to ensure that all aspects of the case are addressed and that each party has a fair chance to present its case. It reflects the judicial system's commitment to impartial justice, where decisions are made on the basis of a full and balanced analysis of the facts and evidence.

The third and final stage in the criminal justice process is the judgment. After the conclusion of the debates and pleadings, the court retires to deliberate on the verdict. This is a crucial stage, as it is here that the final decision on the guilt or innocence of the defendant is taken. The trial takes place in camera, which means that the deliberations are private and away from the public and the media. This confidentiality allows the judges to freely discuss and debate the case without outside influence, basing their decision solely on the evidence and arguments presented during the trial. During deliberations, the judges examine and weigh up all the evidence that has been presented, taking into account the testimony of witnesses, material evidence, expert reports and the arguments of both the prosecution and the defence. They discuss the relevant legal aspects and assess whether the charges against the defendant have been proven beyond reasonable doubt. The deliberative process aims to reach a consensus or, in some systems, a majority decision on the guilt or innocence of the defendant. Once the judges have reached their decision, they write a judgement that sets out the reasons for their verdict, including how they have interpreted the evidence and applied the law. The judgement is then announced in open court. The court explains the reasons for its decision and, if appropriate, pronounces the sentence. This stage marks the conclusion of the criminal trial, although in many legal systems it is possible to appeal against the judgment if one of the parties believes that the trial was not fair or that the laws were not correctly applied.